Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is associated with cognitive deficits long before the onset of stroke or dementia. Recent work has extended these findings and shown that patients with congestive heart failure also exhibit reduced cognitive performance. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is used to help diagnose heart failure, but no study has examined whether BNP predicts cognitive dysfunction in older patients with CVD. BNP values and performance on the Dementia Rating Scale were assessed in 56 older adults with documented CVD. Forty-eight percent of the participants were women, and their average age was 70 ± 8 years. All participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than the cutoff for dementia and no histories of neurologic or severe psychiatric disorders. The average BNP level was 122 ± 202 pg/ml. Hierarchical regression analyses showed that log-transformed BNP levels predicted Dementia Rating Scale total score after adjusting for possible demographic and medical confounders (ΔR2 = 0.09, F[1, 44] = 6.14, p = 0.017). Partial correlation analysis adjusting for these possible confounders showed a particularly strong relation to the conceptualization subtest (r = −0.44, p = 0.002), a measure of verbal and nonverbal abstraction abilities. In conclusion, the results of the present study provide the first evidence for an independent relation between BNP and cognitive dysfunction in older adults with CVD.

We hypothesized that brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels might predict cognitive dysfunction and assessed BNP levels and cognitive performance in a sample of older adults with documented stable cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The following methods were approved by the local institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Fifty-six participants enrolled in a larger, prospective study of the neurocognitive consequences of CVD were included in the present study. For inclusion into the parent study, all participants had to have documented histories of CVD, be between the ages of 55 and 85 years, have Mini-Mental State Examination total scores greater than the cutoff for dementia,1 and have no histories of neurologic or severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., stroke, bipolar disorder). The demographic and medical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics of older patients with cardiovascular disease (n = 56)

| Characteristic | Observed Values | Clinical Cutoff |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 70 ± 8 | |

| Women | 27 (48%) | |

| White | 43 (77%) | |

| Education (yrs) | 14 ± 3 | |

| BNP (pg/ml) | 122 ± 202 | >100 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 58 ± 13 | <50 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.4 ± 1.4 | <4 |

| DRS total score | 136.4 ± 5.5 | <122 total points |

| Heart failure | 15 (27%) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 19 (34%) | |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 14 (25%) | |

| Valve repair/replacement | 4 (7%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (13%) | |

| Hypertension | 40 (71%) | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 13 (23%) |

BNP levels were obtained on the same day as the neuropsychologic battery was conducted and <3 weeks after cardiac evaluation. BNP levels were quantified using the Bayer Advia Centaur (Bayer HealthCare, Tarrytown, New York). Blood samples were sent to the local laboratory for analysis. To promote comparison with past studies, BNP levels were log transformed before statistical analysis to adjust for the skewed distribution.2

The Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) is a commonly used neuropsychologic measure that is sensitive to dementia and cognitive decrease in older adults.3-5 In addition to the DRS total score, 5 subtests assess function in different cognitive domains, namely, attention, initiation and perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory. The DRS was administered and scored according to established protocols by a trained research assistant.

A complete transthoracic echocardiogram was obtained with 2-dimensional apical views from each participant according to the standards of the American Society of Echocardiography. From these data, 2 indexes were derived: the left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiac output (CO). Left ventricular stroke volume was calculated on the basis of biplane volumes (i.e., stroke volume = [end-diastolic volume – end-systolic volume]/end-diastolic volume). The biplane method of discs uses 2 orthogonal views from the apex. This directly assessed area is independent of preconceived ventricular shape and is less sensitive to geometric distortions; it is therefore recommended in patients with coronary artery disease and regional wall motion abnormalities. The biplane method of discs (or Simpson's rule) calculates volumes from the summation of areas from diameters of 20 cylinders, discs of equal height; these are apportioned by dividing the chamber's longest length into 20 equal sections. The left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated on the basis of biplane volumes (i.e., ejection fraction = ([end-diastolic volume – end-systolic volume]/end-diastolic volume) × heart rate).

CO is the amount of blood in liters per minute that is pumped from the heart to perfuse the systemic circulation. Because the flow is pulsatile, CO is a function of stroke volume and heart rate. Stroke volume can be calculated as the mean velocity of blood flow leaving the left ventricle, as recorded with Doppler echocardiography, times the area of the left ventricular outflow tract measured from the 2-dimensional echocardiographic image (CO = [time velocity integral × cross-sectional area] × heart rate). Although this method reflects a noninvasive procedure for obtaining CO, previous research has shown that data generated from such noninvasive procedures strongly correlate with Doppler-based CO.6

Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the relation between BNP levels and DRS total score. In this analysis, possible demographic (age, gender, education) and medical confounding variables (CO, history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery bypass graft, or valve-related surgery) were entered in the first step. Log-transformed BNP levels were entered in the second step. Log transformation was used to reduce positive skew, consistent with other studies examining BNP.7

Two-tailed partial Pearson's correlation analyses were then conducted to further clarify the relation between BNP and cognitive dysfunction. Log-transformed BNP levels were correlated with each DRS index after adjusting for the effects of the aforementioned demographic and medical confounders.

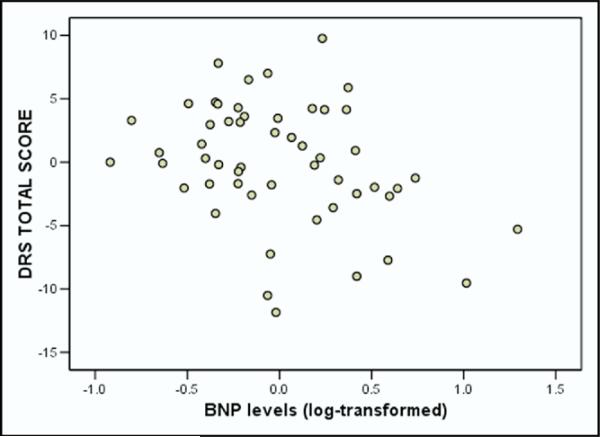

Hierarchical regression showed that BNP levels predicted DRS total score after correcting for possible demographic and medical confounders. Specifically, log-transformed BNP levels accounted for an additional 9% of the variance in DRS total score after adjusting for the demographic and medical variables (F[1, 44] = 6.14, p = 0.017). Figure 1 illustrates the relation between DRS total score and BNP levels after adjusting for demographic and medical confounders.

Figure 1.

Regression scatterplot for the relation between BNP levels and DRS total score after adjusting for demographic and medical confounders.

After adjusting for the aforementioned demographic and medical variables, log-transformed BNP levels were significantly related to DRS total score (r = −0.34, p = 0.02) and DRS conceptualization (r = −0.44, p = 0.002). No such relations emerged for other DRS subtests.

The results of the present study indicate an inverse relation between BNP levels and cognitive function in older adults with CVD. This relation emerged even after adjusting for the effects of relevant demographic and medical variables. A particularly strong relation was found between BNP and DRS conceptualization, a subtest composed of items tapping verbal and nonverbal abstraction abilities. This finding is consistent with past studies showing a relation between CVD and reduced executive function.8-10 Of note, BNP levels were not significantly associated with DRS initiation and perseveration (r = −0.20), a subtest composed of tasks involving semantic verbal fluency, reciprocal coordination, and pattern generation. Performance on similar tasks is often impaired in older adults with CVD, and the reason for the absence of an effect in the current sample is unknown.8,9

Also unclear is the mechanism by which BNP is related to cognitive dysfunction. Elevated BNP levels can be found in patients with ischemic stroke and with adverse blood-brain barrier changes, and our sample generated an average greater than the cutoff suggested for use in acute care settings.11-14 It is possible that patients with CVD with greater cerebrovascular disease or blood-brain barrier disturbance have higher BNP levels and poorer cognitive function. Another possible explanation involves endothelial function. High levels of BNP are associated with reduced endothelial function, particularly in patients with heart failure.15 In turn, endothelial abnormalities have recently been linked to cerebrovascular disease and reduced cognitive function.9,16,17 Further research is needed to clarify the relation between BNP and these possible mechanisms.

There are several limitations of the present study. Although BNP levels were significantly related to cognitive performance in the current sample, further examination in larger and more diverse samples would strengthen the generalizability of the findings. Similarly, determining the relation between BNP and cognition in more specific cardiac disorders may also provide important insight into possible mechanisms. Few studies have directly compared cognitive performance between specific CVD patient groups, such as those with diastolic versus systolic heart failure and those with and without atrial fibrillation. Such studies may provide key insights into the mechanisms underlying CVD-related cognitive dysfunction. Finally, the present study was not adequately powered to determine possible interactions between medications and BNP levels. Recent work indicates a growing number of medications that may influence BNP levels, and the possible cognitive benefits of those interventions are unknown.18

Acknowledgments

Dr. Gunstad was supported in part by Grant F32-HL74568, Dr. Jefferson in part by Grant F32-AG022773, Dr. Paul part by Grant K23-MH065857, and Dr. Cohen in part by Grant R01-AG017975 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- 1.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-Mental State. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald R, Cremo R, Gardetto N, Chiu A, Clopton P, Bhalla V, Maisel A. Effect of nesiritide in combination with standard therapy on serum concentrations of natriuretic peptides in patients admitted for decompensated congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behl P, Stefurak T, Black S. Progress in clinical neurosciences: cognitive markers of progression in Alzheimer's disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:140–151. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100003917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith G, Ivnik R, Malec J, Kokmen E, Tangalos E, Petersen R. Psychometric properties of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. Assessment. 1994;1:123–132. doi: 10.1177/1073191194001002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulinier L, Venet T, Schiller NB, Kurtz TW, Morris RC, Jr, Sebastian A. Measurement of aortic blood flow by Doppler echocardiography: day to day variability in normal subjects and applicability in clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1326. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu A, Omland T, Wold Knudsen C, McCord J, Nowak R, Hollander J, Duc P, Storrow A, Abraham W, Clopton P, et al. Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study Investigators Relationship of B-type natriuretic peptide and anemia in patients with and without heart failure: a substudy from the Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:174–180. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen R, Moser D, Clark M, Aloia M, Cargill B, Stefanik S, Albrecht A, Tilkemeier P, Forman D. Neurocognitive functioning and improvement in quality of life following participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1374–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser D, Cohen R, Clark M, Aloia M, Tate B, Stefanik S, Forman D, Tilkemeier P. Neuropsychological functioning among cardiac rehabilitation patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1999;19:91–97. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raz N, Rodrigues K, Acker J. Hypertension and the brain: vulnerability of the prefrontal regions and executive functions. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1169–1180. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa K, Yamaguchi T, Seida M, Yamada S, Imae S, Tanaka Y, Yamamoto K, Ohno K. Plasma concentrations of brain natriuretic peptide in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:157–164. doi: 10.1159/000083249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter M, Berendes E, Claviez A, Suttorp M. Inappropriate secretion of natriuretic peptides in a patient with a cerebral tumor. JAMA. 1999;281:27–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakagawa K, Yamaguchi T, Seida M, Tanaka Y, Yoshino M. Plasma concentrations of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides in a case with hypertensive encephalopathy. Neurol Res. 2002;24:627–632. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang W, Philip K, Hazen S, Stevenson C, Pepoy M, Neale S, Francis G, Van Lente F, Smith A, Wu A. Comparative sensitivities between different plasma B-type natriuretic peptide assays in patients with minimally symptomatic heart failure. Clin Cornerstone. 2005;7:S18–S24. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(05)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong A, Blann A, Patel J, Freestone B, Hughes E, Lip G. Endothelial dysfunction and damage in congestive heart failure: relation of flow-mediated dilation to circulating endothelial cells, plasma indexes of endothelial damage, and brain natriuretic peptide. Circulation. 2004;110:1794–1798. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143073.60937.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Leeuw F, de Kleine M, Frijns C, Fijnheer R, van Gijn J, Kappelle L. Endothelial cell activation is associated with cerebral white matter lesions in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:306–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan A, Hunt B, O'Sullivan M, Parmar K, Bamford J, Briley D, Brown M, Thomas D, Markus H. Markers of endothelial dysfunction in lacunar infarction and ischaemic leukoaraiosis. Brain. 2003;126:424–432. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moertl D, Berger R, Huelsmann M, Bojic A, Pacher R. Short-term effects of levosimendan and prostaglandin E1 on hemodynamic parameters and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with decompensated chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:1156–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]