Abstract

This study evaluated the impact of a universal school-based violence prevention program on social-cognitive factors associated with aggression and nonviolent behavior in early adolescence. The effects of the universal intervention were evaluated within the context of a design in which two cohorts of students at 37 schools from four sites (N=5,581) were randomized to four conditions: (a) a universal intervention that involved implementing a student curriculum and teacher training with sixth grade students and teachers; (b) a selective intervention in which a family intervention was implemented with a subset of sixth grade students exhibiting high levels of aggression and social influence; (c) a combined intervention condition; and (d) a no-intervention control condition. Short-term and long-term (i.e., 2-year post-intervention) universal intervention effects on social-cognitive factors targeted by the intervention varied as a function of students' pre-intervention level of risk. High-risk students benefited from the intervention in terms of decreases in beliefs and attitudes supporting aggression, and increases in self-efficacy, beliefs and attitudes supporting nonviolent behavior. Effects on low-risk students were in the opposite direction. The differential pattern of intervention effects for low- and high-risk students may account for the absence of main effects in many previous evaluations of universal interventions for middle school youth. These findings have important research and policy implications for efforts to develop effective violence prevention programs.

Keywords: Aggression, Violence prevention, Middle school, Adolescent problem behavior, Social-cognitive

Researchers, policy makers, and school administrators have devoted increasing attention to the development and implementation of school-based violence prevention programs (Farrell and Camou 2006; Hahn et al. 2007). Among the more promising programs are those grounded in social-cognitive models [e.g., US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) 2001; Wilson et al. 2003]. These interventions are based on a large body of research that has identified specific beliefs, attitudes, and skill and information processing deficits exhibited by youth who display high levels of aggression (Crick and Dodge 1994; Huesmann 1988). A primary focus of these programs is on reducing youth violence by altering these processes (Boxer and Dubow 2002).

One of the challenges to interpreting the findings of many existing evaluations of school-based social-cognitive prevention programs has been the discrepancy between the manner in which many programs are designed to be implemented and the designs used to evaluate them. Universal interventions, in particular, are typically designed to be implemented with all students within a specific grade or school. In contrast, many evaluations of such programs have assigned individual students or classrooms within the same school to intervention and control conditions (Farrell et al. 2001a; Henry et al. 2004b). Such designs may not adequately assess the impact of these programs as they were intended to be implemented. Few studies have involved random assignment at the school level, included a large enough number of schools to provide adequate statistical power, and used statistics that account for the nesting of students within schools. Moreover, the majority of studies examining school-level effects have focused on elementary schools [e.g., Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (CPPRG) 1999; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group (MACS) 2002].

The impact of implementing a universal social-cognitive intervention with sixth grade students was recently investigated as part of the Multisite Violence Prevention Project [Multisite Violence Prevention Project (MVPP) 2004, and A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes]. MVPP employed a cluster-randomized design in which 37 schools from four sites were randomized to four conditions to examine the separate and combined effects of two school-based approaches to prevention—a universal intervention that included a student curriculum and teacher training for sixth grade students and teachers; and a selective intervention in which a family program was implemented with a subset of sixth grade students exhibiting high levels of aggression and social influence. The MVPP had several important strengths, including the collection of multiple waves of data across the 2 years following completion of the intervention, a design and data analyses that focused on schools as the unit of randomization, sampling of a large number of students (N=5,581) from schools in four communities, and replication across four research groups.

The focus on middle school-aged youth was designed to address an important gap in the literature. The middle school years are a particularly appropriate focus for violence prevention efforts. They occur just prior to a large increase in the prevalence of aggression, particularly bullying (Tolan and Henry 1996), and coincide with important developmental changes including the transition from elementary school to relatively larger and less structured middle schools, physical changes, and an increase in peer influences (Crocket and Peterson 1993). Despite the potential importance of violence prevention efforts targeted at this age group, the majority of research has focused on younger children (Wilson et al. 2003). Although there are strong arguments for early intervention (Dahlberg and Potter 2001), this does not preclude the need for interventions that address key risk factors across the life course (Boxer et al. 2005a).

The interventions evaluated in the MVPP were developed by a workgroup of representatives from the four participating universities and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (see Meyer et al. 2004 for a more detailed description of this process). The workgroup had frequent meetings and conference calls during a planning year to review best practices and empirical evidence available for existing programs. The GREAT (Guiding Responsibility and Expectations for Adolescents for Today and Tomorrow) student curriculum that emerged from this process was grounded in a social-cognitive framework designed to promote problem-solving skills, self-efficacy for nonviolence, goals and strategies supporting nonviolence, and individual and school norms against the use of violence (Meyer et al. 2004). The curriculum was based on the sixth-grade Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP) curriculum (Meyer et al. 2000), which had shown promise in studies evaluating its impact in both urban and rural schools (e.g., Farrell et al. 2001b, 2003b). The workgroup revised the RIPP curriculum to reflect advances in the field and recommendations based on previous evaluations of the curriculum. The revised curriculum incorporated additional themes including culture and context, self-efficacy for nonviolence, promoting prosocial goals and positive school norms. The curriculum was pilot tested and revised prior to the start of the evaluation study. The student curriculum was implemented in conjunction with a teacher component that included a workshop and support groups (Orpinas et al. 2004).

Findings of a recent study evaluating the impact of the GREAT universal intervention on aggression, victimization, and school norms revealed a complex pattern (A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes). These findings were based on intent-to-treat analyses of multiple waves of data from two cohorts of students at each school within the grade targeted by the interventions. Comparisons of growth curves indicated that students at universal intervention schools reported greater decreases in relational victimization over time relative to students at control schools. In contrast, teacher ratings of students at control schools showed greater decreases in aggression over time relative to students at universal intervention schools. Analyses of short-term effects indicated that students at universal intervention schools reported higher levels of both aggression and school norms for aggression at the end of the intervention year compared to students at control schools. Anticipated intervention effects on overt victimization, school safety problems and school norms supporting nonviolent behavior were not found. The relatively higher level of aggression at universal intervention schools was unexpected and inconsistent with previous studies that found lower posttest levels of aggression for RIPP participants relative to students in control conditions on school-disciplinary code violations for violent offenses (Farrell et al. 2001b) and on student reports of aggression (Farrell et al. 2002, 2003b).

An important finding of the study (A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes) was that the effects of the universal intervention differed for students based on their pre-intervention level of risk. Students at intervention schools with low scores on a risk factor index reported higher levels of aggression and victimization at the end of the intervention year than similar students at control schools, and those at higher risk reported lower levels. This suggests that the overall increase in aggression for students at universal intervention schools was largely driven by changes in the relatively, higher percentage of students at the lowest levels of risk, and did not reflect the pattern of changes for higher-risk students. The differential direction of effects for low-and high-risk students suggests that the intervention may produce movement toward a group mean that works to the benefit of those at higher levels of risk, but may increase aggression among lower-risk students. Previous research linking changes in aggression to normative beliefs at the classroom level (Henry et al. 2000) suggests a possible mechanism for this effect. In particular, the intervention's use of small group activities and role play exercises may have increased students' exposure to norms related to violent and nonviolent methods of dealing with problem situations. This may have resulted in movement toward a classroom norm that would result in increases in aggression for some students and decreases for others. The effects of the GREAT universal intervention on high-risk youth are consistent with several previous studies that found more favorable intervention effects for youth displaying higher initial levels of aggression (CPPRG 2007; Farrell et al. 2001b, 2003a; Ialongo et al. 1999; MACS 2002; Segawa et al. 2005). Fewer studies have reported increases in aggression for low-risk youth participating in interventions (MACS 2002).

The pattern of findings for the impact of the GREAT universal intervention on aggression leaves many unanswered questions. The intervention was designed to produce individual-level changes in specific social-cognitive factors that would in turn produce the desired changes in aggression. The fact that such changes were not found suggests that either the intervention did not produce the necessary changes in the social-cognitive factors it targeted, and/or that changing these factors was not sufficient to produce the desired effects on aggression. The fact that outcomes for aggression were moderated by risk raises the possibility that the intervention's effects on social-cognitive factors also varied as a function of risk. Clarifying the intervention's effects on these more proximal outcomes has important implications for efforts to improve the impact of school-based, social-cognitive interventions for middle school-aged youth. In particular, it will help establish whether further efforts are needed to develop more effective strategies for altering the social-cognitive processes targeted by the intervention, and whether changes in these processes are sufficient to produce the desired changes in aggression.

The present study examined the effects of the GREAT student intervention on the proximal outcomes it was designed to address. In particular, it focused on the intervention's short term (i.e., end of the intervention year) and longer term (i.e., growth curves over 3 years) effects on the following eight social-cognitive constructs: individual norms for aggression, goals and strategies supporting aggression, beliefs supporting fighting, individual norms for nonviolent behavior, self-efficacy for nonviolent responses, goals and strategies supporting nonviolent responses, beliefs supporting nonviolent responses, and social skills. Because risk level moderated the intervention's effects on primary outcomes (A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes), analyses also examined the moderating effects of pre-intervention risk on social-cognitive factors. Finally, the factorial design of the MVPP in which schools were randomized to two interventions (universal and selective), provided an opportunity to determine the extent to which the universal intervention's impact on social-cognitive outcomes was influenced by whether the selective intervention was concurrently implemented.

Method

Design and Settings

Participants were students at 37 schools from four communities: Chicago, Illinois; Durham, North Carolina; Northeastern Georgia; and Richmond, Virginia. Details regarding school recruitment and community characteristics are reported in Henry et al. (2004b). All participating schools included a high percentage of students from low-income families based on eligibility for the federal free or reduced lunch program (i.e., 42% to 96% across sites). The study employed a cluster-randomized design in which an equal number of schools within each site1 were randomly assigned to four conditions: universal intervention, selective intervention, combined (universal and selective) intervention, and no-intervention control. All interventions were implemented with two successive cohorts of sixth graders beginning in 2001. Data were collected from a random sample of students in each cohort. Teacher ratings of individual students in each cohort were collected during the fall (pretest) and spring (post-test) of the sixth grade and the following two school years. Data were collected from students during the fall and spring of the sixth grade and in the spring of the subsequent two school years. An additional wave was collected from Cohort 2 students in the fall of the year following completion of the intervention.

Participants

The impact of the intervention was assessed by collecting data on a random sample of approximately 80 students per cohort from the rosters of each of the larger middle schools, and from all eligible students at the smaller K-8 Chicago schools. Because the universal intervention was not implemented in self-contained special education classrooms, these students were not included in the sample. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the four participating universities and CDC. Consent and assent letters were sent home with students. At three sites where it was permitted, students received a $5 gift card for returning the forms, whether or not they agreed to participate. Telephone follow-ups and home visits were used to increase participation rates. Active parental consent and student assent were obtained from 5,625 of the 7,364 eligible students, yielding a recruitment rate of 76% (see A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes for additional details). Because our focus was on school-level outcomes, data at each wave were only obtained from students who remained in their original school. One or more waves of data were available for 5,581 students (99% of those consented and eligible) on student measures2 and for 5,529 students (98%) on teacher reports. The sample included approximately equal numbers of boys and girls (49% and 51%, respectively), a high percentage of minority students (48% were African American, 23% were Hispanic), and less than half of participants lived in two-parent homes (48%).

Universal Intervention

The universal intervention, consisting of a student curriculum and a teacher intervention, was implemented at the 18 schools randomized to the universal intervention (i.e., those in the universal-only and combined conditions). The 20-session GREAT student curriculum provides instruction and practice in the use of a social-cognitive problem-solving model and instructs students on avoiding dangerous situations, ignoring teasing, asking for help, talking things through, defusing situations, and being helpful to peers. Interventionists used behavioral repetition and mental rehearsal of the skills, small group activities, experiential learning techniques, and didactic modalities to increase students' awareness and use of non-violent options and to alter their attitudes toward and engagement in aggressive behavior. The interventionists included graduate students in a relevant field (e.g., counseling, clinical psychology) and former teachers who completed 36 h of training using a common protocol to enhance cross-site consistency. After each lesson, interventionists completed a checklist to document whether major lesson elements were delivered as intended and rated students' engagement in the lesson. Review of fidelity data found that 95% of the elements of the universal intervention sessions were delivered. Interventionists were observed several times by a site supervisor to identify and correct any implementation problems. The intervention began approximately 10 weeks into the school year after the bulk of baseline assessments were completed and continued until all 20 lessons were completed. Although students typically completed only one lesson per week, two lessons per week were occasionally required in order to complete the intervention before the end of the school year.

The GREAT Teacher Program (Orpinas et al. 2004) involved a 12-h workshop and ten consultation/support group meetings that focused on increasing teacher awareness of different forms of aggression and associated risk factors; and promoting strategies for improving classroom management, reducing aggression, and assisting students who are victimized. Teachers received an overview of the GREAT Student program and learned ways to support it. The 2-day workshop was open to all sixth-grade teachers of core academic subjects and was conducted shortly after the start of the school year. The workshop was supplemented by support/consultation sessions conducted every 2 to 3 weeks across the school year.

Selective Intervention

The selective intervention was a family intervention implemented with a sample of sixth graders at each of the 19 schools assigned to the selective intervention (i.e., the selective-only and combined conditions) that teachers identified as aggressive and influential among their peers (see Smith et al. 2004 for details). The number of students selected at each school ranged from 15 to 25 depending on school size. The 15-week family intervention was conducted in groups of four to eight high-risk students and their parent(s) or guardian (Smith et al. 2004).

Measures

Data were collected on eight social-cognitive constructs targeted by the universal intervention. Students completed measures at school in groups of 10 to 20, using a computer-assisted survey interview. At three sites where approved by the IRB, students received a $5 gift card for participating in the assessment. Parents did not receive any payment for having their child participate. Student behavior ratings were obtained from one core academic teacher per student at each wave. The teacher in the best position to rate each student was identified by each team of teachers. Teachers received $10 for each student measure completed. Alpha coefficients were calculated for each measure based on the pretest data from Cohort 1.

Individual norms for aggression and for nonviolent behavior are based on scales developed by Henry and colleagues (2004a). The Individual Norms for Aggression scale (ten items; alpha=0.73) assesses students' approval of aggressive behaviors by other students (e.g., “How would you feel if a kid in your school hit someone who hit first?”). The Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior scale (eight items; alpha=0.74) assesses students' approval of nonviolent responses (e.g., “How would you feel if a kid in your school ignored a rumor that was being spread about him or her?”). Students rate each item on a three-point scale, anchored by disapprove, neutral, and approve.

Beliefs supporting fighting and nonviolent responses (Farrell et al. 2001b). The Beliefs Supporting Fighting scale (alpha=0.72) asks students to rate their agreement with seven items representing beliefs that support fighting (e.g., “Sometimes a person doesn't have any choice but to fight”). The Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Responses (alpha=0.72) includes five items representing attitudes that support the use of nonviolent responses (e.g., “There are better ways to solve problems than fighting”). Students rate their agreement with each item on a four-point scale. Factor analyses supported the construction of separate scales related to fighting and nonviolent behavior (Farrell et al. 2001b).

Goals and strategies supporting aggression and nonviolent alternatives scales were based on a measure developed by Hopmeyer and Asher (1997). Four vignettes describe potential conflict with a same-sex peer. For each scenario, respondents rate their likelihood of using each of six specific strategies and their agreement with three statements about their goals in that situation (alphas ranged from 0.62 to 0.81). Composite scales were developed based on a review of the content and intercorrelations among the scales. Composites were constructed by receding each score so that it ranged from 0 to 1 and then taking the average across scales. Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression was a composite of one goal scale (Seeking Revenge) and two strategies scales (Mild Physical Aggression and Verbal Aggression; alpha=0.77), Goals and Strategies Supporting Nonviolent Responses was a composite of one goal scale (Maintaining a Good Relationship) and three strategy scales (Compromise, Seek Help from a Teacher, Yield/Withdrawal; alpha=0.71).

Self-efficacy for nonviolent responses assesses how confident students feel about controlling anger and resolving potential conflicts in non-violent ways (alpha=0.81). Items reflect skills taught in the student intervention (e.g., “Talk out a disagreement”). Students rate their confidence in being able to make each response on a five-point scale.

Social skills were assessed by teacher ratings on the Social Skills scale of the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC)-Teacher Rating Scale (Adolescent Form; Reynolds and Kamphaus 1992). The BASC is a multidimensional measure designed to assess the behavior problems and positive or adaptive skills of children ages 4 through 18. Teachers rate student behavior on a four-point frequency scale. This 11-item scale (alpha=0.94) assesses skills necessary for interacting successfully with peers and adults in home, school, and community settings.

Construction of the Risk Factor Index

The Risk Factor Index (RFI) is the same scale used in the A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes report. The RFI was constructed from ten variables representing social-cognitive variables and parental influences associated with increases in aggression. An initial set of 13 variables from the pretest battery was selected based on theoretical or empirical support associating them with the development of aggression among adolescents (see Miller-Johnson et al. 2004 for details on scales in the battery). The relevance of each scale was evaluated by determining if it predicted aggression at Wave 6 after controlling for Wave 1 aggression, gender, ethnicity, family structure, cohort and site. These analyses were restricted to students at no-intervention control schools to avoid the influence of intervention effects. Ten of the 13 variables meeting this criterion at p<0.05 were included in the RFI. These included five of the variables used as outcome measures. Each variable was converted to a binary (present/absent) risk factor. Consistent with Rutter (1990), variables were considered risk factors based on their mechanism of effect (i.e., predictive of an increase in aggression), rather than their direction of effect. Consistent with this approach, the following variables positively associated with changes in aggression were scored as present for students with scores in the upper quartile: Individual Norms for Aggression, Beliefs Supporting Fighting, Revenge Goals, and Parental Support for Aggression. The following variables negatively associated with changes in aggression were scored as present for students with scores in the lower quartile: Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior, Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Responses, Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses, Parental Support for Nonviolent Responses, Parental Monitoring, and School Norms for Nonviolent Behavior. The RFI reflected the number of risk factors present for each student. Although representing a diverse set of variables, the RFI had an acceptable internal consistency (alpha=0.71). Because less than 1.5% of students had more than eight risk factors, those with eight or more were combined into a single group. The RFI had a mean of 3.0 (SD=2.34).

Demographic data were also obtained from the students. For analyses, race/ethnicity was coded into three categories (Hispanic, African American, and other). Family structure was based on presence or absence of an adult male in the household.

Results

Descriptive Statistics at Pretest

Participants at schools assigned to each of the four conditions did not significantly differ in gender or family structure at p>0.05. There were, however, differences in race and ethnicity, χ2 (6, N=5,479)=96.86, p<0.001. Compared to control schools, schools assigned to the universal intervention had lower percentages of Hispanic students [19% at universal-only, χ2 (1, N=2,718)=12.99, p<0.00l, and 16% at combined intervention schools, χ2 (1, N=26,17)=24.80, p<0.001 versus 24% at control schools], and higher percentages of African American students [59% at universal-only, χ2 (1, N=2,718)=48.49, p<0.001, and 58% at combined intervention schools, χ2 (1, N=2,617)=39.23, p<0.001 versus 46% at control schools]. Comparisons of pretest means on measures of aggression, social-cognitive constructs, and the RFI using Proc Mixed (SAS Institute Inc. 2004) to address clustering of students within schools revealed only one significant difference across conditions. Compared to students at control schools, students at selective intervention schools had higher mean scores on Beliefs Supporting Fighting (d=0.13, p<0.05).

Effects at the End of the Intervention Year

The first set of analyses focused on changes at the end of the intervention year (i.e., initial posttest) controlling for pretest levels of each outcome. Random regression models were estimated using SAS PROC Mixed (SAS Institute Inc. 2004) to account for the nesting of individual observations (level 1) within students (level 2) and nesting of students within schools (level 3). For each outcome, scores across all available posttest waves were modeled as a function of intervention condition, time since the end of the sixth-grade school year, and student- and school-level covariates3. Student-level covariates included pretest scores on the outcome measure, gender, race/ethnicity, family structure, and cohort. Site was included as a school-level covariate. Covariates were mean-centered to facilitate interpretation. The model used a foil-information maximum likelihood approach in which parameter estimates were based on all students with at least one observation on the outcome measure. This made it possible to include students with missing data at one or more waves. Changes following the initial pretest were modeled by a linear slope, quadratic trend, and fall-to-spring indicator to take seasonal variation into account4. The model included main effects for each student and school-level variable and interactions of each of these variables with the linear slope for time.5

Analyses were based on an intent-to-treat approach, in which all students were. included based on the condition their school was assigned. Intervention conditions were dummy coded and represented by a 2 (assigned/not assigned to universal intervention)×2 (assigned/not assigned to selective intervention) design. The primary focus for this analysis was on the main effects for the universal intervention. These effects represent differences between students at universal intervention schools and comparison schools at the end of the intervention year after controlling for pretest scores, effects of the selective intervention, and other covariates in the model. Significance tests on the Universal Intervention×Selective Intervention interactions were examined to determine if the effects of the universal intervention differed depending upon whether schools also received the selective intervention. The consistency of intervention effects across gender was examined by testing Gender×Universal Intervention interactions and conducting follow-up tests of significant interactions to identify any significant gender-specific intervention effects, d-coefficients (Cohen 1988) were used as estimates of effect size.

Significant differences at initial posttest were found on two of the eight social cognitive outcomes (see Table 1). Students at universal intervention schools, reported higher posttest levels of Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression (d=0.11, p<0.05), and individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior (d=0.l0, p<0.05) than those at comparison schools. There were no significant Universal×Selective interactions. Significant Gender×Universal Intervention effects were found for two outcomes. Boys at universal intervention schools had higher posttest levels of Self Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses than boys at control schools (d=0.16, p<0.05); this effect was not significant for girls (d=−0.0l). For the BASC Social Skills scale effects were in opposite directions for boys (d=0.07) and girls (d=−0.07), but neither was significant.

Table 1.

Universal intervention effects on social-cognitive effects on initial posttest and effects on linear growth across all waves

| Outcome Measure | Initial Posttesta |

Linear changeb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | SE(d) | Slope | SE | d | |

| Individual Norms for Aggression | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Goals and Strategies—Aggression | 0.11* | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Beliefs Supporting Fighting | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| Self-Efficacy For Nonviolent Responses | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| Goals and Strategies—Nonviolent Responses | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.30 | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Responses | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| BASC Social Skills | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.55 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

Results reflect separate analyses to examine universal intervention effects at the end of the intervention year (adjusted for pretest scores on outcome measure), and effects on linear slopes in growth curve analysis. Effects were adjusted for cohort, gender, race/ethnicity, family structure, and site.

BASC Behavioral Assessment System for Children.

Coefficients represent mean differences (d-coefficients) at the end of the intervention year for schools assigned to the universal intervention versus those that were not.

Linear slope coefficients at universal intervention schools and associated d-coefficients representing differences in linear slopes between universal intervention schools and comparison schools.

p<.05

Risk as a Moderator of Effects at the End of the Intervention Year

The model described in the preceding section was expanded to determine the extent to which intervention effects at the end of the intervention year were moderated by pre-intervention scores on the RFI. This involved adding the main effect for RFI, and the following interactions: RFI×Condition, RFI×Cohort, RFI×Condition×Cohort, RFI×Time, RFI×Condition×Time, RFI×Cohort×Time, and RFI×Condition×Cohort×Time. Because boys had higher RFI scores than girls (i.e., M=3.3 vs 2.6, d=0.30, p<0.001), the model also included main effects for gender and gender interactions that paralleled those include for the risk index.

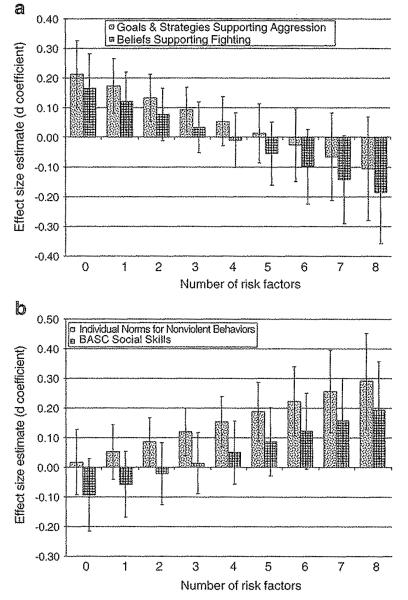

Significant RFI×Universal Intervention effects at the initial posttest were found for four of the eight social-cognitive variables, Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression [t(5131)=−2.55, p<0.05], Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior [t(5084)=2.47, p<0.05], Beliefs Supporting Fighting [t(5075)=−3.00, p<0.01], and BASC Social Skills [t(5134)=2.91, p<0.01]. Figure 1 reports effect size estimates (d-coefficients) representing differences in adjusted posttest scores between students at schools assigned to the universal intervention and students at comparison schools for each level of the RFI. The 95% confidence interval bands indicate the points at which these effects significantly differ from zero. The overall pattern was for low-risk students at universal intervention schools to have higher posttest adjusted scores than those at comparison schools on Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression, and Beliefs Supporting Fighting. As the number of risk factors increased beyond 5 or 6, the pattern reversed itself with high-risk students at universal intervention schools reporting increasingly lower levels of these variables. For Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior and BASC Social Skills, there were no significant differences between low-risk students at universal intervention and comparison schools. As risk increased, students at universal intervention schools had increasingly higher scores on Norms for Nonviolent Behavior and BASC Social Skills relative to those at the comparison schools.

Fig. 1.

Differences in adjusted means (d-coefficients) between students at schools assigned to universal intervention condition versus comparison schools as a function of the number of risk factors at pretest. Figures include a variables positively correlated with aggression, and b variables negatively correlated with aggression

The influence of the RFI on universal outcomes at the end of the intervention year was not moderated by concurrent implementation of the selective intervention. There were, however, additive effects of implementing both interventions that were moderated by risk for Goals and Strategies Supporting Nonviolent Responses [t(5131)=2.71, p<0.01], and Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior [t(5131)=2.03, p<0.05]. Follow-up analyses revealed no intervention effects for low-risk students, but benefits, in terms of increases for students with five or more risk factors for Goals and Strategies Supporting Nonviolent Responses [t(30)=2.07 to 2.67, d=0.13 to 0.26, as the RFI increased from 5 to 8, all ps<0.05] and for those with four or more risk factors for Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior [t(30)=2.34 to 2.59, d=0.11 to 0.25, all ps<0.05].

Intervention Effects on Growth Curves

Analyses of the longer-term intervention effects were conducted by comparing growth curve trajectories for students attending schools assigned to the universal intervention to more normative development represented by growth trajectories for students at control schools (MacKinnon and Lockwood 2003) using random regression models via SAS PROC Mixed (SAS Institute 2004). Changes in outcomes since pretest were modeled by an intercept, linear slope, quadratic trend, and fall-to-spring indicator6. These models were similar to those described in the preceding section with several important differences. Pretest scores on outcome variables were included as one of the waves of data collection rather than as a covariate and the reference point for time was set to the date of the pretest assessment. Within these models, main effects represent each variable's relation to pretest scores on the outcome variable, and interactions with the linear slope indicate each variable's impact on the outcome's linear trajectory. Significance tests on the Universal×Time interactions were used to compare linear slopes on outcome measures for students at schools assigned to the universal intervention (i.e., the universal-only and combined conditions) to linear slopes for students at comparison schools (i.e., the selective-only and control conditions), after controlling for selective intervention effects.

Normative Growth Patterns

Social-cognitive variables related to aggression increased across the 3 years of data collection (positive linear slope), with the amount of increase decelerating (negative quadratic). In contrast, variables related to nonviolence showed a general pattern of decreasing over time. One exception was Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior, which increased. Within this overall pattern, there were also changes within each school year. Individual Norms for Aggression, Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression, Individual Norms for Nonviolent Behavior, and BASC Social Skills increased between the fall and spring of each school year (ds=0.03 to 0.06), and Self Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses and Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Responses decreased during the school year (ds=−0.05 and −0.04).

Intervention Effects on Linear Changes

Comparison of linear slopes for students at universal intervention schools to those at control schools showed no significant differences (see Table 1). Universal intervention effects on linear slopes did not differ across gender, There were significant Universal×Selective×Time interactions on two of the eight outcomes. Compared to control schools, there were no significant differences in linear slopes on Individual Norms for Nonviolent Responses for the universal-only (ds=−0.03), or selective only (d0.00) schools. However, students at schools assigned to both interventions had more positive linear slopes on this variable than students at control schools (d=0.04, p<0.05). Follow-up analyses of a significant Universal×Selective×Time interaction for BASC Social Skills did not indicate any significant effect for students at schools in the combined intervention condition.

Pre-intervention Risk as a Moderator of Intervention Effects on Growth Curves

The growth curve model was expanded to determine the extent to which intervention effects were moderated by pre-intervention scores on the RFI by adding the same main effects and interaction terms included in the risk models for analyses of initial posttest effects. Pre-intervention risk moderated the effects of the universal intervention on linear slopes for five of the eight outcome measures including Individual Norms for Aggression [t(5478)=−3.61, p<0.001], Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression (t(5529)=−3.55, p<0.001], Beliefs Supporting Fighting [t(5476)=−2.10, p<0.05], Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior [t(5476)=3.23,) p<0.01], and Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses [t(5531)=3.94, p0.001]. The common pattern was for positive impact of the intervention for those at higher risk levels and for negative effects at lower levels of risk (see Table 2). Thus, compared to their counterparts at comparison schools, low-risk students at universal intervention schools reported higher rates over time on Individual Norms for Aggression, and Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression; and lower rates over time on Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior and Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses. In contrast, the higher-risk students at universal intervention schools showed lower rates over time on Individual Norms for Aggression, Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression, and Beliefs Supporting Fighting; and higher rates over time on Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior and Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses.

Table 2.

Universal intervention effects on linear slope coefficients (d-coefficients) at different levels of the risk factor index

| Number of Risk Factors |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Individual Norms for Aggression | |||||||||

| Linear slope | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 |

| Comparison to Control (d-coefficient) | 0.11** | 0.08** | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06* | −0.10* | −0.13** | −0.17** |

| Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression | |||||||||

| Linear slope | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Comparison to Control (d-coefficient) | 0.12*** | 0.08** | 0.05* | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.09* | −0.12** | −0.15** |

| Beliefs Supporting Fighting | |||||||||

| Linear slope | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.07 |

| Comparison to Control (d-coefficient) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.10* |

| Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Behavior | |||||||||

| Linear slope | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Comparison to Control (d-coefficient) | −0.11** | −0.07** | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08* | 0.11* | 0.14** |

| Self-Efficacy For Nonviolent Responses | |||||||||

| Linear slope | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Comparison to Control (d-coefficient) | −0.15*** | −0.11*** | −0.08*** | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.11* | 0.14** |

Coefficients represent slopes for students at universal intervention schools and slope effects (d-coefficients reflecting differences in slopes for universal versus comparison schools) across each level of the Risk Factor Index. Effects were adjusted for cohort, gender, race/ethnicity, family structure, and site.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001

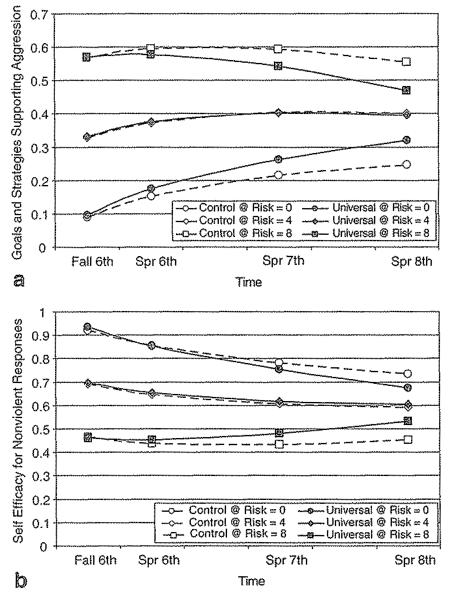

Figure 2 illustrates the two patterns of effects in estimated growth curves for students at universal intervention and control schools for subgroups of students with pretest RFIs of 0, 4, and 8. Students with higher scores on the RFI at pretest had higher mean scores on Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression. Within the control group these differences diminished over time with high-risk students showing a relatively flat slope, and low-risk students reporting increases over time. Scores for students at universal intervention schools showed greater convergence: High-risk students reported decreases over time, and low-risk students reported greater increases than their counterparts at comparison schools. In short, the universal intervention had the net effect of reducing differences between high- and low-risk students over time. This produced beneficial effects for those at high levels of risk [i.e., greater decreases over time in social-cognitive variables related to aggression (see Fig. 2a), and greater increases in social-cognitive variables related to nonviolent behavior (see Fig. 2b)], but opposite effects for those at low levels of risk.

Fig. 2.

Growth trajectories for students at universal and control schools as a function of the number of risk factors at pretest on a Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression, and b Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses. Plotted trajectories are based on linear and quadratic coefficients but do not include variation within school years (i.e., fall-to-spring changes). Intercepts within each level of the Risk Index were based on the average across intervention and control schools to facilitate comparisons

Each of the five variables for which a significant RFI×Universal Intervention slope effect was found had that effect significantly attenuated by concurrent implementation of the selective intervention. RFI×Intervention effects on slopes for students at schools that received both interventions were not significant for Goals and Strategies Supporting Aggression, Beliefs Supporting Fighting, or Beliefs Supporting Nonviolent Responses. RFI×Intervention effects on slopes remained significant for Individual Norms for Aggression [t(5478)=−2.85, p<0.01] and for Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses [t(5531)=2.10, p<0.05]. In contrast to the pattern at universal-only schools, combined intervention effects were significant for high-risk youth, but not for low-risk youth. Compared to students at control schools at the same level of risk, students at combined intervention schools with four or more risk factors had larger decreases in linear slope for Individual Norms for Aggression [t(5478) went from −2.60 to −3.18, and corresponding ds went from −0.07 to −0.18 as the RFI increased from 4 to 8, all ps<0.01]. Students with six or more risk factors at combined intervention schools had larger increases in Self-Efficacy for Nonviolent Responses [t(5478) went from 2.09 to 2.18, and corresponding ds went from 0.08 to 0.12 as risk factors increased from 6 to 8, all ps<0.05].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which the GREAT Student intervention produced changes in several social-cognitive constructs it was designed to address. Main effects were found on only two of the eight variables examined. Students at universal intervention schools reported higher levels of individual norms for nonviolent behavior at the end of the intervention year than students at comparison schools. Contrary to predictions, they also reported higher levels of goals and strategies that supported the use of aggression. With respect to longer-term effects, there were no significant intervention effects on growth curve trajectories for any of the variables examined. Intervention effects were mostly consistent across gender and the intervention's effects were generally not influenced by concurrent implementation of the selective intervention. Intervention effects were, however, moderated by students' pre-intervention risk such that high-risk students tended to benefit from the intervention and effects for low-risk students were in the opposite direction.

Previous studies examining the main effects of school-based interventions on social-cognitive processes of middle school-aged youth have found a mixed pattern of results. Studies examining the impact of RIPP (Meyer et al. 2000)—the universal student curriculum on which the GREAT Student intervention was based—have focused primarily on changes in attitudes and beliefs. Although all four studies (Farrell et al. 2001b, 2002, 2003a,b) found small increases on an intervention knowledge test, only one (Farrell et al. 2003b) found significant increases on attitudes supporting nonviolence. One other study reported significant decreases on attitudes supporting violence (Farrell et al. 2002). Evaluations of other school-based prevention programs have found nonsignificant effects on social-cognitive variables and, in some cases, effects counter to predictions. Skroban et al. (1999) evaluated a school-based intervention that included components designed to promote self-regulation and social problem-solving skills. Using a quasi-experimental design, students at the intervention school did not differ from those at a comparison school on an interview-based measure of problem-solving skills. Contrary to expectations, students at the intervention school reported weaker beliefs in conventional rules, more favorable attitudes to drug use, and less self-efficacy at posttest relative to students at the comparison school. Orpinas et al. (1995) examined several social-cognitive outcomes in their quasi-experimental evaluation of the Second Step curriculum with middle school students, and found no lasting effects on self-efficacy for nonviolent expression, knowledge or skills. In contrast, an evaluation of several prevention programs for elementary school students found significant intervention effects on five social-cognitive outcomes, and determined that these effects mediated the interventions' effects on the rate of growth in violent behavior (Ngwe et al. 2004).

One of this study's key findings was that the universal intervention's effects varied as a function of pre-intervention risk. These moderated effects are consistent with previously reported findings that high-risk students reported less aggression and victimization at the initial posttest than their counterparts at control schools, and low-risk students at intervention schools reported higher levels (A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes). Additional work is needed to determine the extent to which specific changes in social-cognitive processes may mediate the intervention's effects on changes in aggression and victimization for youth at different levels of risk. Such a pattern of effects could account for previous studies that have found more favorable intervention effects on aggression for adolescents displaying higher initial levels of aggression (Farrell et al. 2001b, 2003a; MACS 2002; Segawa et al. 2005). Few previous evaluations of universal intervention programs have examined the differential impact on students at differing levels of risk (Silver and Eddy 2006). Because there are many more students at the low end of the risk continuum (i.e., 50% with 0 to 2 risk factors versus 17% with 6 or more in the present study), main effects generally reflect changes within low-risk students and may mask any effects among those at highest risk. This may account for the relatively weak, and in some cases negative, effects found in many previous evaluations of school-based universal interventions for adolescents. Such effects underscore the importance of going beyond analyses of main effects to consider individual differences that moderate effects (Farrell and Vulin-Reynolds 2007).

A primary focus of the intervention was on decreasing normative beliefs about the legitimacy of using violence and promoting beliefs supporting nonviolent strategies for dealing with problem situations. The clearer benefits for high-risk youth are consistent with the meta-analysis of Wilson et al. (2003) of the effects of school-based violence prevention programs. They noted that larger intervention effects for high-risk youth may reflect the fact that such individuals simply have more room for change than those at low levels of aggression. The more positive effects on high-risk youth may also reflect the fact that social-cognitive interventions are specifically designed to address the beliefs, attitudes, and skill deficits exhibited by aggressive youth. Interventions that focus on altering these processes may have a minimal effect on low-risk youth who are less likely to display this pattern.

The differential direction of effects for low- and high-risk students may be due to social processes related to the intervention's small group focus. Boxer et al. (2005b) offered a theory of “discrepancy-proportional peer influence” to describe their findings that random assignment to intervention led students to become more similar to other members of their intervention group; that is, the initially highly aggressive members of the intervention group benefited most from intervention, whereas initially less aggressive members of the intervention group were adversely changed by intervention. They interpreted their findings as indicating that a group intervention in which participants interacted with each other led to mutual peer influences: Highly aggressive members became less aggressive and less aggressive members became more aggressive, particularly when the main contact the program leaders have with the youth is during the intervention. These results are consistent with Silver and Eddy's (2006) argument that peers who differ most from the group consensus may be most susceptible to peer influences.

Dodge et al. (2006) summarized the large literature supporting the hypothesis that group interventions tend to lead its members to influence each other, with high-risk members benefiting and relatively low-risk members worsening. Although the findings reviewed by Dodge et al. (2006) concerned selective and targeted intervention programs, the present findings indicate that the phenomenon can extend to universal programs as well. Within the present study, the intervention's use of small group activities and role plays may have increased both low-risk and high-risk youths' exposure to peer norms that were more at odds with their own beliefs. Further work is needed to identify the circumstances under which such effects occur. It is possible that interventionists, particularly those who are well-trained and have ample opportunities to interact with the students, can play an important role in minimizing the risk for negative effects on the lower-risk youth while enhancing the benefits for the higher risk youth. The implementation of other programs may also mitigate such effects. In the present study the moderating effects of risk on longer-term outcomes were attenuated by implementing the universal intervention in conjunction with the family-based selective intervention. In two cases where effects of the combined intervention were moderated by risk, benefits were found for high-risk students, without adverse effects for low-risk youth. Although implementing both interventions did not generally lead to more positive overall effects on social-cognitive variables or on aggression (cf. A.D. Farrell, 2008, Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Main Effects on Primary Outcomes), the findings suggest the possibility that adverse group influences for low-risk students may be altered by combining universal and selective approaches. More work is needed to develop specific intervention components specifically designed to address this phenomenon.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that merit discussion. Although a large sample of schools was recruited, the small number of schools assigned to each condition (i.e., 9–10) introduces the possibility that existing differences between schools at baseline and changes within one or two schools within a condition (e.g., changes in teaching staff or school policies) may have influenced the findings. Several measurement issues also bear discussion. The social-cognitive outcomes examined in this study focused primarily on values, attitudes and beliefs and not on some of the other specific skills targeted by the intervention (e.g., emotion regulation and social problem-solving skills) or their application to actual problem situations. This limitation was largely driven by the availability of suitable measures that could be employed within the scope and available budget of this large-scale study. The timing of the intervention may also have been less than optimal. Efforts to change the social ecology of a school, particularly those that include teacher training, would ideally begin prior to the start of the school year. Interventions within the current study began several months into the school year because of the need to identify, consent, and collect pretest data from participants. Because the current study focused intervention efforts on a single grade level, students at intervention schools were not isolated from the influences of students in other grade levels who were not the focus of any intervention efforts. Sixth graders also represent the youngest, and often smallest and least influential, students within middle schools. Whether more intensive or comprehensive prevention efforts directed across grade levels could produce clearer effects has yet to be determined.

The multisite nature of this study resulted in the recruitment of schools that differed in size, structure, geographic region, and demographic and ethnic composition. Although efforts were made to standardize intervention procedures, site differences led to some variability in the selection, training, and supervision of interventionists. Previous studies have found significant differences based on different implementation patterns (e.g., Aber et al. 1998), and contextual factors (e.g., MACS 2007). The effects of the interventions introduced under such varied circumstances may simply not have been sufficiently robust to generate a consistent pattern of main effects. More generally, the fact that the interventions were implemented as part of a research project may have also reduced the degree of school staff commitment to the interventions. Finally, the analyses were based on a fairly conservative intent-to-treat approach and, thus, may not accurately reflect the outcomes for students who received the intended dosage of the intervention.

Conclusions

The findings of this study have important implications for further efforts to develop effective prevention programs. The potentially negative effects of some interventions that segregate high-risk youth has led to arguments favoring universal interventions to avoid such effects. Silver and Eddy (2006, p. 271) recently concluded that “while examined rarely, there is no evidence that low-risk peers who continue to gain exposure to the high-risk youth due to universal or other classroom-based programming are negatively impacted.” The current study suggests that such effects may, indeed, occur. However, additional research is needed to improve our understanding of this phenomenon and the factors that promote its occurrence. Whether the effects found for low-risk students represent increased awareness and reporting of aggression, an increase in “acting up” or assertiveness, or some increase in more serious forms of aggression remains to be determined. Such work is needed to inform the debate over when the gain to one group (i.e., high-risk students) offsets and justifies potential negative effects to other groups of youth within the context of universal intervention strategies (Cook and Ludwig 2006).

The current study is consistent with the broader literature that has found modest effects for universal school-based violence prevention programs focused on middle-school aged youth. Further work is clearly needed to enhance the overall effects of such efforts. Examination of growth trajectories for control schools suggest a generally negative pattern in that social-cognitive factors associated with aggression are generally increasing during middle school, and those associated with nonviolence are on the decrease. The fact that many of these factors are shaped by children's experience during the early elementary school years (Huesmann and Guerra 1997) suggests that efforts to alter these processes after they have been well established may have limited impact. Because risk and protective factors play different roles at different developmental stages, it is likely that comprehensive efforts that go beyond those that focus on individual youth by incorporating interventions at multiple levels across different stages of development will be required to address this problem (Tolan et al. 1995; USDHHS 2001). Toward that end, further work is needed to identify specific clusters of risk and protective factors that emerge during early adolescence to guide the development of effective strategies for addressing emerging factors related to aggression and other forms of problem behavior during this critical period of development (Boxer et al. 2005a; Farrell and Camou 2006). Such efforts, implemented within isolation, are likely to produce modest effects, but could play an important role in the development of more comprehensive efforts.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Cooperative Agreements U81/CCU417759 (Duke University), U81/CCU517816 (University of Chicago, Illinois), U81/CCU417778 (The University of Georgia), and U81/CCU317633 (Virginia Commonwealth University). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Because nine schools were recruited at the Georgia site, random assignment resulted in two schools in three of the conditions and three schools assigned to the selective intervention condition.

Responses were screened for patterns that were clearly implausible. Two reviewers examined the data from students who gave the same response to every item in a scale or patterned responses (e.g., 1,2,3,2,1) throughout a scale, across multiple scales. The reviewers independently considered the plausibility of the patterns, the number of scales with implausible patterns, and the time taken to complete each scale, thereby identifying cases that each deemed problematic. The two reviewers then discussed these cases and came to consensus regarding which cases should be excluded from analyses. This resulted in the screening out of 10 cases or less from each wave.

This has an advantage over simpler models based on only the first two waves of data in that the inclusion of the additional waves of posttest data provides a more accurate estimate of each individual's score at the end of the intervention year by making use of all available data.

Random effects were specified for intercepts and slopes at the student level, and for intercepts at the school level. The quadratic and fall-to-spring indicator were treated as fixed effects to facilitate the interpretation of intervention effects on linear slopes.

Degrees of freedom for main effects of the school-level variables (i.e., condition and site) were set at 30 (37 schools–3 for condition–3 for sites–1 for intercept). Degrees of freedom for other effects were set at the number of individuals minus the number of individual-level terms and interactions in the model minus 1.

Random effects were specified for intercepts and slopes at the student level, and for intercepts at the school level. The quadratic and fall-to-spring indicator were treated as fixed effects to facilitate the interpretation of intervention effects on linear slopes.

References

- Aber JL, Jones SM, Brown JL, Chaudry N, Samples F. Resolving conflict creatively: Evaluating the developmental effects of a school-based violence prevention program in neighborhood and classroom context. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:187–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001576. doi:10.1017/S0954579498001576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Dubow EF. A social-cognitive information-processing model for school-based aggression reduction and prevention programs: Issues for research and practice. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 2002;10:177–192. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(01)80013-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Goldstein SE, Musher-Eizenmann D, Dubow EF, Heretick D. Developmental issues in school-based aggression prevention from a social-cognitive perspective. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005a;26:383–400. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0005-9. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-0005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Morales J. Proximal peer-level effects of a small-group selected prevention on aggression in elementary school children: An investigation of the peer contagion hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005b;33:325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3568-2. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-3568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:648–657. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group The Fast Track randomized controlled trial to prevent externalizing psychiatric disorders: Findings from grades 3 to 9. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1250–1262. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31813e5d39. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31813e5d39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Assigning youths to minimize total harm. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth. Guilford; New York: 2006. pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett L, Petersen A. Adolescent development: Health risks and opportunities for health promotion. In: Millstein S, Petersen A, Nightengale E, editors. Promoting the health of adolescents. Simon & Schuster; New York: 1993. pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL, Potter LB. Youth violence: Developmental pathways and prevention challenges. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(Suppl 1):3–30. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00268-3. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Dishion TJ. The problem of deviant peer influences in intervention programs. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. Guilford; New York: 2006. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Camou S. School-based interventions for youth violence prevention. In: Lutzker J, editor. Preventing violence: Research and evidence-based intervention strategies. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2006. pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Meyer AL, Kung EM, Sullivan TN. Development and evaluation of school-based violence prevention programs. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001a;30:207–220. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_8. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Meyer AL, Sullivan TN, Kung EM. Evaluation of the Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP) seventh grade violence prevention curriculum. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003a;12:101–120. doi:10.1023/A:1021314327308. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Meyer AL, White KS. Evaluation of Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP): A school-based prevention program for reducing violence among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001b;30:451–463. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_02. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Valois R, Meyer AL. Evaluation of the RIPP-6 violence prevention program at a rural middle school. American Journal of Health Education. 2002;33:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Valois RF, Meyer AL, Tidwell R. Impact of the RIPP violence prevention program on rural middle school students. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2003b;24:143–167. doi:10.1023/A:1025992328395. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Vulin-Reynolds M. Violent behavior and the science of prevention. In: Flannery D, Vazonsyi A, Waldman I, editors. Cambridge handbook of violent behavior. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 766–786. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, Lowy J, Liberman A, Crosby A. The effectiveness of universal school-based programs for the prevention of violent and aggressive behavior. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56(No RR7):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Cartland J, Ruchross H, Monahan K. A return potential measure of setting norms for aggression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004a;33:131–149. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027001.71205.dd. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000027001.71205.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Farrell AD, The Multisite Violence Prevention Project The study designed by a committee: Design of the Multisite Violence Prevention Project. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004b;26(1S):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.027. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Tolan PH, VanAcker R, Eron LD. Normative influences on aggression in urban elementary school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:59–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1005142429725. doi:10.1023/A:1005142429725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopmeyer A, Asher SR. Children's responses to two types of peer conflict situations; Symposium presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Washington, DC. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. An information-processing model for the development of aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1988;14:13–24. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1988)14:1<13::AID-AB2480140104>3.0. CO;2-J. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Guerra NG. Children's normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:408–419. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.408. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:599–641. doi: 10.1023/A:1022137920532. doi:10.1023/A:1022137920532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM. Advances in statistical methods for substance abuse prevention research. Prevention Science. 2003;4:155–171. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649822872. doi:10.1023/A:1024649822872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group A cognitive-ecological approach to preventing aggression in urban settings: Initial outcomes for high risk children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:179–194. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group Changing the way children “think” about aggression: Social-cognitive effects of a preventive intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:160–167. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.160. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AL, Allison KW, Reese LE, Gay FN, Multisite Violence Prevention Project Choosing to be violence free in middle school: The student component of the GREAT Schools and Families universal program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(1S):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.014. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AL, Farrell AD, Northup WB, Kung EM, Plybon L. Promoting nonviolence in early adolescence: Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways. Academic; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Sullivan TN, Simon TR, The Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project Evaluating the impact of interventions in the Multi-Site Violence Prevention Project: Samples procedures, and measures. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(1S):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multisite Violence Prevention Project The Multisite Violence Prevention Project: Background and overview. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(1S):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.017. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwe JE, Liu LC, Flay BR, Segawa E, Aban Aya Coinvestigators Violence prevention among African American adolescent males. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(Suppl 1):S24–S37. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.s1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Horne AM, Multisite Violence Prevention Program A teacher-focused approached to prevent and reduce students' aggressive behavior: The GREAT Teacher Program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(1S):29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.016. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Parcel GS, McAlister A, Frankowski R. Violence prevention in middle schools: A pilot evaluation. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17:360–371. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00194-W. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(95)00194-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines MN: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cicchetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. What's new in SAS 9.0, 9.1, 9.1.2, and 9.1.3. Author; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Segawa E, Ngwe JE, Li Y, Flay BR, Aban Aya Coinvestigators Evaluation of the effects of the Aban Aya Youth Project in reducing violence among African American adolescent males using latent class growth mixture modeling techniques. Evaluation Review. 2005;29:128–148. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04271095. doi:10.1177/0193841X04271095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Eddy JM. Research-based prevention programs and practices for delivery in schools that decrease the risk of deviant peer influence. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. Guilford; New York: 2006. pp. 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Skroban SB, Gottfredson DC, Gottfredson GD. A school-based social competency promotion demonstration. Evaluation Review. 1999;23:3–27. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9902300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Gorman-Smith D, Quinn W, Rabiner D, Tolan P, Winn D-M, The Multisite Violence Prevention Project Community-based multiple family groups to prevent and reduce violent and aggressive behavior: The GREAT families program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(1S):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.018. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Guerra NG, Kendall P. A developmental-ecological perspective on antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: Toward a unified risk and intervention framework. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:579–584. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.579. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.63.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Henry D. Patterns of psychopathoiogy among urban poor children: Comorbidity and aggression effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1094–1099. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1094. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.I094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services . Youth violence: A report of the surgeon general. United States Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. The effects of school-based intervention programs on aggressive behavior; A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:136–149. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]