Abstract

Objective

To systematically develop a quality indicator (QI) set for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

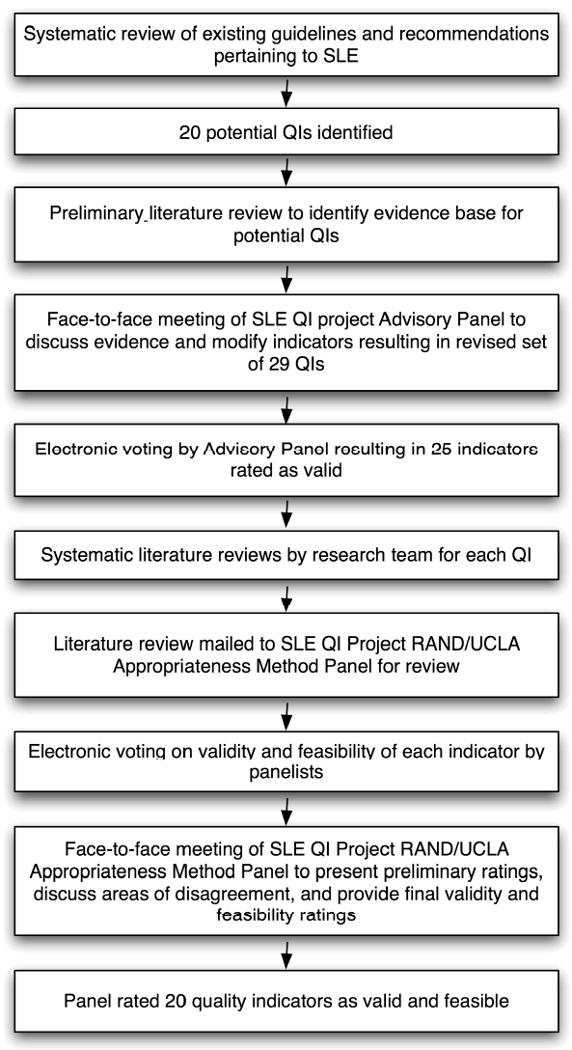

We used a validated process that combined available scientific evidence and expert consensus to develop a QI set for SLE. First, we extracted 20 candidate indicators from a systematic literature review of clinical practice guidelines pertaining to SLE. An advisory panel revised and augmented these candidate indicators, and through two rounds of voting, arrived at 25 QIs. These QIs advanced to the next phase of the project, in which we employed a modification of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. A systematic review of the literature was performed for each QI, linking the proposed process of care to potential improved health outcomes. After reviewing this scientific evidence, a second interdisciplinary expert panel convened to discuss the evidence and provide final ratings on the validity and feasibility of each QI.

Results

The final expert panel rated 20 QIs as both valid and feasible. Areas covered include diagnosis, general preventive strategies (e.g. vaccinations, sun avoidance counseling, screening for cardiovascular disease), osteoporosis prevention and treatment, drug toxicity monitoring, renal disease, and reproductive health.

Conclusions

We employed a rigorous multi-step approach with systematic literature reviews and two expert panels to develop QIs for SLE. This new set of indicators provides an opportunity to assess health care quality in SLE, and represents an initial step toward the important goal of improving care in this patient population.

Long-term survival of patients with SLE has improved greatly over the last several decades, but morbidity from the disease and complications of medical therapy remain important concerns. Although many studies have explored risk factors associated with poor outcomes in SLE,1-4 few studies have investigated the quality of health care received by patients with this condition.5, 6 One important barrier to such research is the lack of consensus on health care processes constituting high quality care in SLE. We aimed to address this gap by developing a quality indicator (QI) set for SLE.

Over the last decade, research focusing on quality measurement in health care has burgeoned, partly in response to the initiative launched by the Institute of Medicine [IOM] in 1996 to assess and improve health care quality. The IOM defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”7 In the United States, the most commonly used tools to measure quality have taken the form of QIs, defined as “retrospectively measurable elements of practice performance for which there is evidence or consensus that can be used to assess the quality of care provided and hence change it”.8 Unlike clinical guidelines or recommendations that often aim to define optimal health care practices in the context of complex clinical decision making, QIs are meant to represent a minimally acceptable standard of care across a specific patient population.9

Indicators that assess health care quality have traditionally been grouped into three related categories, including structural measures (e.g. innate characteristics of providers and the system), process measures (e.g. what health care providers do in delivering care), or outcome measures (e.g. what happens to patients, particularly with respect to their health).10, 11 For many chronic diseases, quality assessment has focused primarily on process rather than outcome measures for a number of reasons, including that health outcomes often require years to develop and their measurement may therefore delay timely interventions, and that there remains limited consensus on the correct outcome measures to assess for many conditions. Likely as a result of these limitations, QI sets pertaining to several prevalent rheumatic diseases have also focused on process measures. A multidisciplinary panel for the Arthritis Foundation Quality Indicator Project developed process indicators to assess quality for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and analgesic use,9 and indicators have also been developed for gout.12 For this project, we relied solely on indicators measuring processes of care as well.

Although the prevalence of SLE is lower than that of conditions previously targeted for QI development, quality assessment may be especially desirable in SLE. First, as a multi-organ disease with varied manifestations, SLE often requires care by multiple providers across a range of health care settings. This fragmented structure of care may contribute to deficiencies in quality. Second, despite improved therapies, the relative burden of morbidity and mortality from SLE remains high, and a majority of patients accumulate significant organ damage and disability over time.13-15 The need to improve patient outcomes in SLE therefore remains an important priority, and quality measurement and enhancement efforts have potential to contribute toward this goal. Finally, significant disparities in health outcomes exist in SLE, with racial/ethnic minorities and those with low socioeconomic status demonstrating consistently poorer outcomes over time.16 The relative contribution of processes of care to the poorer outcomes in these vulnerable populations remains uncertain, and until now, the lack of validated process measures has encumbered efforts to further investigate these relationships.

We present here the methods used to develop process indicators for SLE. Like other investigators who have previously developed QIs for general medical conditions and rheumatic diseases, we adhered to a validated method of combining scientific evidence from the literature and expert consensus to create indicators for SLE.

Methods

Figure 1 summarizes the methods used to develop the SLE QI set. The general approach, developed at the RAND Corporation based on several decades of research,17 has been used extensively in the literature to develop QIs for a variety of health care practices and conditions.

Figure 1. Methods for Developing the SLE Quality Indicator Set.

Recognizing that SLE is among the most complex conditions targeted for QI development to date, we decided a priori to limit the scope of our work to several general topics. These included diagnosis, general preventive care practices, and areas of disease-specific management with either high prevalence or high morbidity (i.e. osteoporosis, renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and pregnancy and reproductive health).

Phase 1: Devising preliminary QIs

To devise a preliminary list of QIs, we performed a systematic review of the literature to retrieve all recommendations and guidelines relevant to SLE. We used a broad strategy, including searches in the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases, as well as internet-based searches of medical societies and national organizations doing health care quality work (e.g. the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse, the National Kidney Foundation, the National Guidelines Clearinghouse). We excluded editorials or reviews, including only efforts that had used a consensus-based approach relying on scientific evidence. From this search, we drafted 20 preliminary QIs, each of which had to represent a topic area of interest, derive support either from scientific evidence or professional consensus, and deal with processes that are under the influence of health care providers.

We devised the preliminary QIs in an IF-THEN-BECAUSE format, where the IF component defined the eligible population, the THEN component explicitly defined the process of care to be performed by health care providers, and the BECAUSE component summarized the health benefits accrued by the patient.9 Our research team performed preliminary literature reviews using the MEDLINE database to define how the processes of care in each QI were linked to patient outcomes. This information was compiled in a document and formed the scientific basis for the SLE Quality Indicators Project advisory panel meeting in October 2007.

Phase 2: SLE QI Advisory Panel Meeting

The project advisors identified 8 individuals to serve on an advisory panel, drawing from specialists in SLE research and patient care, health services researchers, and rheumatologists practicing in non-academic settings (Table 1). During a one-day meeting, the advisory panel deleted two QIs secondary to lack of scientific evidence; nine QIs underwent minor revisions, such as changes in wording or clarification, and 9 QIs underwent major revisions, such as adding or subtracting content or separation into multiple QIs. Using a modification of the nominal group technique, the panel also added 9 additional QIs. In total, 29 QIs resulted from the meeting.

Table 1. Members of SLE Quality Indicators Project Advisory Panel and RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method Expert Panel.

| SLE QI Project Advisory Panel | Primary Practice Setting |

|---|---|

| Moderator | |

| David Wofsy, MD | University of California, San Francisco |

| Panelists | |

| Eliza Chakravarty, MD, MSc | Stanford University |

| Maria Dall'Era, MD | University of California, San Francisco |

| James Davis, MD* | Sutter Health, San Francisco |

| John C. Davis, Jr., MD, MPH† | University of California, San Francisco |

| Kenneth Kalunian, MD | University of California, San Diego |

| Nina D. Schwartz, MD | Kaiser Permanente, South San Francisco |

| Daniel J. Wallace, MD | David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA |

| Michael M. Ward, MD | NIH/NIAMS |

| SLE QI Project RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method Panel | |

| Moderator | |

| Catherine MacLean, MD, PhD‡ | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Panelists | |

| Rashmi B. Dixit, MD, PhD | Walnut Creek, California |

| Richard Furie, MD | North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System |

| Jennifer Grossman, MD | David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA |

| Lester Miller, MD | Santa Cruz, California |

| Rosalind Ramsey-Goldman, MD, DrPh | Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University |

| Brad Rovin, MD* | Ohio State University |

| Kenneth Saag, MD | University of Alabama at Birmingham |

| Jorge Sanchez-Guerrero, MD, MS | National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubirán, Mexico |

| David Wofsy, MD | University of California, San Francisco |

James Davis practices Internal Medicine and Rheumatology. Brad Rovin is a nephrologist. All others primarily practice Rheumatology.

John C. Davis, Jr. is currently employed at Genentech, Inc. He was employed at the University of California, San Francisco when asked to sit on the panel.

Catherine MacLean is also Director of Programs in Clinical Excellence at Wellpoint, Inc.

The revised QI set was then reviewed by additional outside consultants, including experts in SLE and quality measurement. Further adjustments to wording were made, and the revised QI set was then re-presented to the advisory panel for two rounds of electronic voting. Panelists rated the validity of each indicator using a 9-point scale (1 representing “invalid”, and 9 representing “definitely valid”). Twenty-five indicators had a high mean validity rating (7-9), and progressed to the next phase of the project.

Phase 3: Systematic Literature Reviews

Our research team (J.Y., P.P., J.Z.G., G.S.) then undertook systematic literature reviews to summarize the scientific evidence linking the advocated processes of care to patient outcomes. We largely adhered to methods outlined in the Cochrane Collaborative Working Group on Systematic Reviews,18 except that we used a single reviewer to assess studies for most QIs. In cases where questions arose, a second reviewer also assessed studies. Professional librarians set up formal searches at our respective institutions in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases.

The search results were reviewed in several steps. First, we screened retrieved titles. Next, abstracts of relevant titles were reviewed in detail, and full-length manuscripts were obtained for studies with potential information linking the process of care advocated in the QI to patient outcomes. Non-English articles, and those not reporting original research were excluded. Finally, we hand-searched the references of retrieved studies as well as review articles for completeness. In total, our research team examined over 6000 search results in MEDLINE and over 9000 search results in EMBASE.

We summarized these literature reviews in a monograph. Each QI review had the following components: 1) a summary of previous consensus-based guidelines or recommendations on the topic; 2) details of the systematic review strategy and results; 3) specification of the type of evidence (meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, observational studies, or other); 4) a summary of the direct evidence (i.e. where adequate clinical trial or observational data linked the process of care to health outcomes in SLE specifically), and indirect evidence (e.g. summaries of professional consensus statements, data from other chronic diseases, or circumstantial evidence in SLE). Where evidence was lacking, this was also clearly stated. The resulting 260-page monograph served as the scientific basis for the next phase of the project.

Phase 4: The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method Panel

For the final phase of the project, we employed a modification of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method, a technique with content, construct and predictive validity, to generate a final indicator set for SLE.17, 19-22 This method has previously been described as the best systematic method of combining expert opinion and evidence.23 In brief, this approach entails two rounds of anonymous ratings on a standardized scale by an expert panel. The second round of ratings takes place after a face-to-face discussion among panelists. Research has demonstrated that the reproducibility of this method is consistent with that of common diagnostic tests, such as the interpretation of mammograms.22 Adaptation of this method to the SLE QI project is discussed in detail below.

The project advisors assisted in identifying 9 physicians to sit on the final expert panel; 5 members were rheumatologists with special expertise in SLE, 2 members were rheumatologists in private practice, 1 member was a nephrologist, and 1 member was a rheumatologist/health services researcher with experience in QI development. Prior to the face-to-face meeting in May 2008, we mailed the monograph summarizing the scientific evidence to panelists and asked them to rate the feasibility and validity of each QI using a web-based survey tool.

Panelists rated each potential QI on two 1-9 scales, one for validity and one for feasibility (1 representing “not valid” or “not feasible, and 9 representing “definitely valid” or “definitely feasible”). For validity, panelists were instructed to consider the following questions: 1) Is there adequate scientific evidence or professional consensus to support the indicator? 2) Are there identifiable health benefits to patients who receive care specified by the indicator? 3) Based on your professional experience, would you consider physicians with significantly higher rates of adherence to the indicator higher quality providers? 4) Are the majority of factors that determine adherence to the indicator under the control of the physician (or are they subject to influence by the physician)? For feasibility, panelists were asked to consider the following questions: 1) Is the information necessary to determine adherence possible to find in an average medical record (or is failure to document such information itself a marker of poor quality)? 2) Is the estimate of adherence to the indicator based on medical record data likely to be reliable and unbiased?24

Results of these preliminary ratings were compiled and sent to panelists approximately one week before the meeting, allowing them to compare their responses to their colleagues. During the meeting, each panelist again received an anonymous summary of the rankings of other members of the group, as well as their own ranking. The meeting moderator used these data to guide discussion, focusing on areas with greatest disagreement. No attempt was made to force the panel to consensus; instead, the discussion attempted to determine whether divergent ratings resulted from real clinical disagreement, or simply reflected different understandings of the indicators that might require clarification. After several minor revisions, panelists anonymously re-rated the validity and feasibility of each item using the same scale described above.

Data Analysis

Our analytic plan adhered to methods previously used by other investigators at the RAND Corporation.9, 17 Indicators with a mean validity rating of ≥7.0 and without disagreement were considered valid. Disagreement was defined as two or more panelists rating the indicator in the highest tertile (rating of 7, 8 or 9), and two in the lowest tertile (rating of 1, 2, or 3). Indicators with a mean feasibility rating ≥4.0 were considered feasible. Only indicators rated as both valid and feasible by panelists are included in the final QI set.24 A summary of the criteria for indicator inclusion in the final SLE QI set is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Indicator inclusion criteria for the final SLE QI set.

| Mean Validity Rating* | Mean Feasibility Rating | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | 1-3 | Exclude |

| 1-3 | 4-6 | Exclude |

| 1-3 | 7-9 | Exclude |

| 4-6 | 1-3 | Exclude |

| 4-6 | 4-6 | Exclude |

| 4-6 | 7-9 | Exclude |

| 7-9 | 1-3 | Exclude |

| 7-9 | 4-6 | Include |

| 7-9 | 7-9 | Include |

To be valid, indicators required a high mean validity rating, as well as no evidence of disagreement. Disagreement was defined as two or more ratings in the highest tertile for validity, and two or more ratings in the lowest tertile.

Results

The final QI ratings are listed in Tables 3. Twenty-five candidate QIs were presented to the expert panel. In some cases, minor revisions or clarification of wording were made prior to voting, although all content areas remained constant. For the pharmacologic therapy monitoring QIs listed in Table 4, the validity and feasibility of each drug were rated separately, and in some areas, where disagreement was present in the pre-meeting ratings, on the individual laboratory tests or procedures suggested for each drug.

Table 3. Final SLE quality indicators rated as valid and feasible.

| Quality Indicator | Validity (Mean, Range) |

Feasibility (Mean, Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||

|

IF a patient has a suspected diagnosis of SLE, THEN an initial work-up should include the following: ANA, CBC with differential, platelet count, serum creatinine, and urinalysis. |

8.2 (4-9) | 5.0 (1-9) |

|

IF a patient is newly diagnosed with SLE, THEN the following laboratory tests should be ordered within 6 months of diagnosis: anti-dsDNA, complement levels, and anti-phospholipid antibodies. |

8.1 (6-9) | 8.6 (7-9) |

| General Preventive Strategies | ||

|

IF a patient has SLE, THEN education about sun avoidance should be documented at least once in the medical record (e.g. wearing protective clothing, applying sunscreens whenever outdoors, and avoiding sunbathing). |

7.7 (5-9) | 5.6 (3-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE is on immunosuppressive therapy, THEN an inactivated influenza vaccination should be administered annually, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

7.7 (6-9) | 6.7 (5-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE is on immunosuppressive therapy, THEN a pneumococcal vaccine should be administered, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

7.6 (6-9) | 6.7 (2-9) |

| Osteoporosis | ||

|

IF a patient with SLE has received prednisone ≥7.5 mg/day (or other glucocorticoid equivalent) for ≥3 months, THEN the patient should have bone mineral density (BMD) testing recorded in the medical record*, unless the patient is currently receiving anti-resorptive or anabolic therapy. |

8.0 (7-9) | 7.9 (7-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE has received prednisone ≥7.5 mg/day (or other glucocorticoid equivalent) for ≥3 months, THEN supplemental calcium and vitamin D should be prescribed or recommended and documented. |

7.6 (6-9) | 7.1 (5-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE has received prednisone ≥7.5 mg/day (or other glucocorticoid equivalent) for ≥1 month, and has a central t-score ≤-2.5 or a history of fragility fracture, THEN the patient should be treated with an anti-resorptive or anabolic agent, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

8.0 (6-8) | 8.0 (6-9) |

| Drug Monitoring | ||

|

IF a patient is prescribed a new medication for SLE (e.g. NSAIDs, DMARDs or glucocorticoids), THEN a discussion with the patient about the risks versus benefits of the chosen therapy should be documented. |

8.3 (7-9) | 8.3 (7-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE is newly prescribed an NSAID, DMARD, or glucocorticoid, THEN baseline studies should be documented within an appropriate period of time from the original prescription (TABLE 4). |

See Table 4 | See Table 4 |

|

IF a patient with SLE has established treatment with an NSAID, DMARD, or glucocorticoid, THEN monitoring for drug toxicity should be performed (TABLE 4). |

See Table 4 | See Table 4 |

|

IF a patient with SLE is taking prednisone ≥10 mg (or other steroid equivalent) for ≥3 months, THEN an attempt should be made to taper the prednisone, add a steroid-sparing agent, or escalate the dose of an existing steroid-sparing agent, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

7.7 (4-9) | 7.7 (5-9) |

| Renal Disease | ||

|

IF a patient has had evidence of SLE renal disease (increasing proteinuria, active urinary sediment, a rising creatinine, or disease activity on renal biopsy) in the past two years, THEN the following should be obtained at 3-month intervals: CBC, serum creatinine, urinalysis with microscopic evaluation, and measurement of urine protein using a quantitative assay. |

8.0 (5-9) | 7.8 (5-9) |

|

IF a patient is diagnosed with proliferative SLE nephritis (WHO or ISN/RPS Class III or IV), THEN therapy with corticosteroids combined with another immunosuppressant agent should be provided and documented within one month of this diagnosis, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

8.7 (8-9) | 8.6 (8-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE has renal disease (proteinuria ≥300 mg/day or eGFR<60 mL/min) and ≥2 blood pressure readings, including the last reading, where sbp>130 or dbp>80 over 3 months, THEN pharmacologic therapy for hypertension should be initiated or the current regimen should be changed or escalated, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

8.7 (8-9) | 8.6 (7-9) |

|

IF a patient with SLE has proteinuria≥300 mg/day, THEN the patient should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB, unless patient refusal or contraindications are noted. |

8.2 (7-9) | 8.6 (8-9) |

| Cardiovascular Disease | ||

|

IF a patient has SLE, THEN risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including smoking status, blood pressure, BMI, diabetes, and serum lipids (including total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides), should be evaluated annually. |

8.3 (6-9) | 7.6 (5-9) |

| Pregnancy and Reproductive Health | ||

|

IF a patient with SLE is pregnant, THEN anti-ssA, anti-ssB**, and anti-phospholipid antibodies† should be documented in the medical record. |

8.4 (7-9) | 8.1 (7-9) |

|

IF a patient has had pregnancy complications as a result of the anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) ‡, THEN the patient should be offered aspirin and heparin (i.e. heparin or low molecular weight heparin) during subsequent pregnancies. |

8.0 (5-9) | 7.6 (6-9) |

|

IF a woman between 18 and 45 years of age is started on any of the following medications for SLE: chloroquine, quinacrine, methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, or thalidomide, THEN a discussion with the patient about the potential teratogenic risks of therapy and about contraception should be documented prior to drug initiation, unless the patient is unable to conceive (e.g. has had a hysterectomy, oopherectomy, tubal ligation, or is post-menopausal). |

7.7 (4-9) | 7.6 (4-9) |

The panel recommends that BMD testing be recorded in the medical record either within the 12 months preceding or the 6 months after initiation of glucocorticoid therapy.

The panel recommends that anti-ssA and anti-ssB antibodies should be recorded in the medical record during the first trimester and reflect current testing or results from the prior two years.

The panel recommends anti-phospholipid antibodies should be recorded in the medical record within 4 weeks of the diagnosis of pregnancy and reflect current testing or results from the prior six months.

APS pregnancy complications include unexplained fetal death after 10 weeks gestation, birth before 34 weeks as a result of severe preeclampsia, eclampsia or placental insufficiency, or three or more unexplained consecutive spontaneous abortions before the 10th week of gestation, in the setting of positive anti-phospholipid antibody testing.

Table 4. Quality Indicators for Pharmacologic Therapy Monitoring in SLE.

| A. Baseline studies for pharmacologic therapy. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | CBC and platelets | Serum Cr | Serum glucose | AST or ALT | Albumin | Alk Phos | UA | Other |

| NSAIDs & salicylates† | X* | X | Blood pressure | |||||

| Glucocorticoids† | X | Blood pressure | ||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Fundoscopic exam within one year | |||||||

| Azathioprine‡ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Cyclophosphamide‡ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Methotrexate‡ | X | X | X | X | X | CXR§ | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil‡ | X | X | ||||||

| B. Interval studies for pharmacologic therapy (number represents interval in weeks). | ||||||||

| NSAIDs & salicylates | 52* | 52 | 52 | Blood pressure (52) | ||||

| Glucocorticoids | 52 | Blood pressure (52) | ||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Low risk patients (age 18 to 60 yrs): — one exam every two years.† High-risk patients (age >60 yrs, dose >6.5 mg/kg, impaired renal or hepatic function, obesity, macular degeneration, or prior anti-malarial drug use): — annual screening.† |

|||||||

| Azathioprine | 12 | 12 | ||||||

| Cyclophosphamide | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Methotrexate | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |||

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 12 | |||||||

Only if risk factors for GI bleeding present: age ≥ 75, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, or glucocorticoid use.

Recommended interval for baseline testing: 3 months prior or 1 month after drug initiation.

Recommended interval for baseline testing: within 1 month of drug initiation.

Recommended interval for baseline testing: within the prior year or 1 month after drug initiation.

Modified American Academy of Ophthalmology recommendations.25

Panelists rated 20, or 80%, of the statements as valid and feasible indicators of quality in SLE. Five statements had either a mean validity rating <7 or disagreement among panelists and were excluded from the final set; no QIs were excluded based on low feasibility alone (for deleted QIs, see Appendix). As outlined in Table 3, the final set includes QIs related to diagnosis (2), general preventive strategies, including sun protection counseling and vaccinations (3), osteoporosis (3), drug monitoring (4), renal disease (4), prevention of cardiovascular disease (1), and pregnancy and reproductive health (3).

Discussion

Using a validated approach that relies on a combination of scientific evidence and expert consensus, we have developed a QI set for SLE. The 20 QIs cover several important aspects of SLE care including diagnosis, general preventive strategies (e.g. vaccinations, sun avoidance counseling), osteoporosis prevention and treatment, screening for cardiovascular disease, drug toxicity monitoring, renal disease, and reproductive health. The QIs provide an initial tool for assessing health care quality in SLE, a condition in which serious health care disparities among demographic and socioeconomic groups have been reported.16

The potential impact of applying SLE QIs to practice will depend partly on their technical characteristics (face/content validity, reproducibility, acceptability, feasibility, reliability, sensitivity to change, predictive validity).8 Performing the requisite basic methodological research to define these properties is an important step in validating the QI set. Thereafter, the impact will depend largely on uptake of the indicators by researchers and organizations interested in measuring and improving health care quality. The SLE QIs provide both a unique opportunity and challenge on this latter front, as the complexity and lower prevalence of the condition may require more innovative research designs and larger patient or administrative databases than traditionally required in quality measurement efforts.

It is important to note that the QIs presented here reflect either the current scientific evidence or professional consensus in SLE. However, QIs are not meant to be static. As stronger clinical evidence becomes available over time, this initial set of indicators may require revisions and updating. In the meantime, the initial QI set provides a starting point for quality measurement in SLE.

Although we used a validated approach to develop the SLE QI set, several caveats should be taken into consideration. It is essential to keep in mind that QIs represent a minimal acceptable standard of care, and are not meant to represent best practices or to serve as guidelines for patient management. Moreover, QIs have traditionally been used to assess quality retrospectively, a function distinct from guidelines or recommendations, which often define optimal care for a condition and assist clinical decision-making prospectively. Accordingly, while QIs are often limited in scope, guidelines more comprehensively address clinical care, and may intentionally leave room for clinician judgment. Many important aspects of care for patients with SLE are therefore not covered by the QI set, such as the management of specific disease manifestations (e.g. neuropsychiatric disease, hematological manifestations, etc.), or special populations (e.g. pediatric SLE). Moreover, important aspects of disease assessment, such as comprehensively evaluating SLE activity, were also excluded because the expert panels felt further scientific evidence was needed before advocating the use of specific disease activity indices in routine clinical practice. As more scientific evidence becomes available, future efforts may focus on developing QIs for these areas.

Our effort is the first to our knowledge to systematically develop QIs for a less common rheumatic condition. Whereas indicators for rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis rely on a larger evidence base of randomized clinical trials, robust clinical trial evidence in SLE is limited for many aspects of disease, necessitating greater reliance on observational studies, studies in other related conditions, and expert consensus. We attempted to address this limitation by incorporating two face-to-face panel meetings rather than one, with distinct panelists at each meeting. In order to “pass” to the second meeting, indicators had to reach a high level of agreement by the first panel. Although this methodology likely allowed us to adequately capture expert consensus, our research also highlighted that further clinical trial evidence is needed for many aspects of SLE management. It is our hope that dissemination of the QI set may help spur such efforts.

In conclusion, we have created an initial quality indicator set for SLE using a validated technique, a modification of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. We hope that the availability of QIs will allow researchers and organizations to engage in quality measurement efforts in SLE. Further study in this area also has the potential to affect health outcomes in SLE not only by identifying demographic groups and health care settings where care is deficient, but also by serving as the basis for clinical trials and policy interventions that aim to improve quality.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank participating librarians, including Gloria Won at the University of California, San Francisco, Kimberly Schwartz at Stanford University, and Rosalind Dudden at National Jewish Hospital. In addition, the authors thank Caroline Gordon, MD, R. Adams Dudley, MD, Chi-yuan Hsu, MD, MSc, and Virginia D. Winn, MD, PhD for their review of draft indicators, Ann Clarke, MD for assistance in identifying members of the expert panels, and Ted Mikuls, MD, Jennifer Barton, MD, Laura Trupin, MPH and Jim Calvert for general assistance with the project.

Supported by the Arthritis Foundation, the American College of Rheumatology/Research and Education Foundation and NIAMS P60-AR-053308. Additional support provided by the Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis at the University of California, San Francisco.

Appendix. Items deleted from SLE Quality Indicator Set

| Quality Indicator |

|---|

| Original QIs deleted during SLE QI project advisory panel meeting |

|

| Additional QIs suggested by advisory panel and deleted during formal voting after meeting |

|

| Final QIs deleted during SLE QI project RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method panel ratings |

|

References

- 1.Sutcliffe N, Clarke AE, Gordon C, Farewell V, Isenberg DA. The association of socio-economic status, race, psychosocial factors and outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 1999;38(11):1130–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward MM, Lotstein DS, Bush TM, Lambert RE, van Vollenhoven R, Neuwelt CM. Psychosocial correlates of morbidity in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology. 1999;26(10):2153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Lew RA, et al. The relationship of socioeconomic status, race, and modifiable risk factors to outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997;40(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman AW, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. IV. Factors associated with self-reported functional outcome in a large cohort study. LUMINA Study Group. Lupus in Minority Populations, Nature versus Nurture. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12(4):256–66. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)12:4<256::aid-art4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernatsky S, Pineau C, Joseph L, Clarke A. Adherence to ophthalmologic monitoring for antimalarial toxicity in a lupus cohort. The Journal of rheumatology. 2003;30(8):1756–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernatsky SR, Cooper GS, Mill C, Ramsey-Goldman R, Clarke AE, Pineau CA. Cancer screening in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology. 2006;33(1):45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington D.C., USA: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ (Clinical research ed. 2003;326(7393):816–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLean CH, Saag KG, Solomon DH, Morton SC, Sampsel S, Klippel JH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: methods for developing the Arthritis Foundation's quality indicator set. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;51(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/art.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring Vol 1 The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Health Administration Press; Ann Arbor, MI: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Shekelle PG. Defining and measuring quality of care: a perspective from US researchers. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12(4):281–95. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/12.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikuls TR, MacLean CH, Olivieri J, et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50(3):937–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yelin E, Trupin L, Katz P, et al. Work dynamics among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;57(1):56–63. doi: 10.1002/art.22481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker-Merok A, Nossent HC. Damage accumulation in systemic lupus erythematosus and its relation to disease activity and mortality. The Journal of rheumatology. 2006;33(8):1570–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Rahman P, Ibanez D, Tam LS. Accrual of organ damage over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology. 2003;30(9):1955–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odutola J, Ward MM. Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health among patients with rheumatic disease. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2005;17(2):147–52. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000151403.18651.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brook RH. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. In: McCormick KA, Moore SR, Siegel RA, editors. Methodology Perspectives. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. pp. 59–70. AHCPR Pub No 95-009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervnetions 4.2.5. Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2005. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kravitz RL, Park RE, Kahan JP. Measuring the clinical consistency of panelists' appropriateness ratings: the case of coronary artery bypass surgery. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1997;42(2):135–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(97)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shekelle PG, Chassin MR, Park RE. Assessing the predictive validity of the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method criteria for performing carotid endarterectomy. International journal of technology assessment in health care. 1998;14(4):707–27. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300012022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kravitz RL, Laouri M, Kahan JP, et al. Validity of criteria used for detecting underuse of coronary revascularization. Jama. 1995;274(8):632–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, Leape LL, Kamberg CJ, Park RE. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;338(26):1888–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806253382607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J, Durie A, Thapar A, Roland MO. Quality assessment for three common conditions in primary care: validity and reliability of review criteria developed by expert panels for angina, asthma and type 2 diabetes. Quality & safety in health care. 2002;11(2):125–30. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States (Appendix) The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357(15):1515–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmor MF, Carr RE, Easterbrook M, Farjo AA, Mieler WF. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(7):1377–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]