Abstract

In a country such as Japan with the average age of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with antivirals sometimes well above 60 years, the standard combination therapy is not well tolerated. In this randomized, prospective, controlled trial, we investigated the efficacy of 24-week peginterferon α monotherapy for easy-to-treat patients. A total of 132 patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 2 (n = 115) or low viral load HCV genotype 1 (<100 kIU/ml, n = 17) were treated with peginterferon α-2a (180 μg/week). Patients with a rapid virological response (RVR, HCV RNA negative or <500 IU/ml at week 4) were randomized for a total treatment duration of 24 (group A) or 48 (group B) weeks. Patients who did not show RVR (group C) were treated for 48 weeks. Sustained virological response (SVR) was assessed by qualitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. One hundred eight of 132 (82%) patients with RVR were randomized. SVR rates were 60% (group A), 79% (group B), and 27% (group C), respectively. Similar SVR rates were achieved in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 with low pretreatment viral load (<1000 kIU/ml) in group A (81%) and group B (79%) (P = 0.801), whereas in those with higher viral load (≥1000 kIU/ml), a lower SVR rate was identified in group A (26%) than in group B (67%) (P = 0.041). In conclusion, in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 and pretreatment viral load below 1000 kIU/ml who achieve RVR, 24-week treatment with peginterferon α-2a alone is clinically sufficient. Those who show no RVR or have higher baseline viral load, require alternative therapies.

Keywords: Randomized trial, Chronic hepatitis C, Peginterferon-α monotherapy, Rapid virological response, Genotype 2, Pretreatment viral load

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection may progress to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [1–3]. Interferon (IFN)-based treatment of HCV-infected patients can achieve viral clearance and thereby improve histology and prognosis [4, 5]. Thus, the primary aim of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C is a sustained virological response (SVR), defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA by a sensitive molecular assay 24 weeks after the end of treatment.

A combination therapy of peginterferon and ribavirin is currently recognized as the standard treatment of chronic hepatitis C, resulting in 40–50% of SVR rate in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 and around 80% in those infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 [6–8]. The combination therapy, however, tends to be associated with adverse events more frequently than those that occur with IFN monotherapy [9–14], resulting in dose reduction or discontinuation of therapy and thus impaired response rate particularly in elderly patients [15]. Furthermore, patients with renal failure, ischemic vascular disease, and congenital hemoglobin abnormalities never tolerate ribavirin treatment of their chronic hepatitis C.

In Japan, the Bureau of National Health Insurance provides reimbursement for 24-week interferon α-2b plus ribavirin combination therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C with high viral load or re-treatment, irrespective of viral load, since December 2001 and for 48 weeks of peginterferon α-2a monotherapy for all patients with chronic hepatitis C since December 2003. The bureau started to provide reimbursement for 24-week peginterferon α-2b and ribavirin therapy for those infected with HCV genotype 2 and high viral load or re-treatment, irrespective of viral load, since December 2005. Thus, Japanese patients infected with HCV genotype 2 and high viral load or re-treatment irrespective of viral load have been able to receive either peginterferon α monotherapy or combination therapy with ribavirin since December 2003.

There are three major phase II/III or phase III clinical trials of peginterferon α monotherapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C [16–18]. All three studies indicate that the long-acting pegylated forms of IFN-α are more potent than standard IFN-α monotherapies. Factors independently associated with SVR to peginterferon α include viral genotype, low pretreatment viral load, age, no cirrhosis, and body surface area [18]. The reported SVR rate in patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and a baseline viral load of less than 2 million copies/ml is around 60% or more [16, 17]. A phase II study of 48-week peginterferon α-2a therapy conducted in Japan demonstrated an SVR rate as high as 71% in patients with HCV genotype 2 infection [19]. Furthermore, 85% of the patients, who had undetectable levels of HCV RNA after 4 weeks of therapy, had an SVR [19]. Thus, data on viral kinetics have led to the hypothesis that in these patients, 24 weeks of treatment may be as effective as the recommended course of 48 weeks. Therefore, 48-week therapy may lead to overtreatment in some patients who have a rapid virological response (RVR). Shorter treatment duration should also be associated with better tolerability and lower rate of premature discontinuation of therapy. This is particularly relevant to elderly patients with HCV genotype 2 infection who can less tolerate the combination therapy with ribavirin and/or a longer treatment period. However, whether the duration of treatment with peginterferon α alone can be reduced from 48 to 24 weeks in patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 2 or low viral load HCV genotype 1 without compromising antiviral efficacy is not clear at present.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of peginterferon α-2a administered alone for 24 or 48 weeks in patients with chronic HCV genotype 2 infection or low viral load HCV genotype 1 and had a virological response at week 4.

Materials and methods

Patients

Adult patients with chronic HCV infection who had the following characteristics were eligible for the study: (1) a positive test for anti-HCV antibody, (2) HCV genotype 1 and an HCV RNA level less than 100,000 IU/ml or HCV genotype 2 irrespective of viral load, (3) entry neutrophil and platelet counts and hemoglobin level of at least 1500/μl, 90,000/μl, and 10 g/dL, respectively. Patients with the following criteria were excluded: other viral infections such as infection with hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus; any other cause of liver disease such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, drug-induced liver disease, and excessive daily intake of alcohol; relevant disorders including decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other malignant neoplastic disease; concomitant use of immunosuppressive or herbal medications such as Sho-saiko-to; current illicit drug use; neurological or psychiatric diseases; and allergic to peginterferon α-2a or other interferons and biological preparations including vaccines.

Study design

The current study was an investigator-initiated study. This multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled trial was originally discussed and designed on 12 July 2003, by a committee composed of 36 staff members from 33 participating hospitals and universities (the Japanese Consortium for the Study of Liver Diseases). The diagnostic criteria for chronic hepatitis C, treatment regimens, and follow-up protocols were finalized by the committee on 9 November 2003. This study compared the efficacy and safety of 24 vs. 48 weeks of treatment with peginterferon α-2a in patients with chronic HCV genotype 2 infection or low viral load HCV genotype 1 and showed an RVR (serum HCV RNA negative [<50 IU/ml] or <500 IU/ml by HCV RNA test at week 4 of therapy).

Eligible patients were treated with peginterferon α-2a (PEGASYS; Chugai Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at a dose of 180 μg once per week subcutaneously. Patients who showed RVR at 4 weeks of treatment were randomized into either total treatment duration of 24 (group A) or 48 (group B) weeks. Randomization was performed at Okayama University Graduate School, centrally accessed through fax. Patients were assigned upon a report of RVR to group A or B with a computer-based random allocation system by a researcher who was independent of the study, and the allocation system was not accessible by any of the investigators who enrolled patients for the study. Randomization was stratified according to genotype (genotype 1 or 2) and previous IFN treatment (naive or re-treated) and was not blocked. Patients who were still positive for HCV RNA (by qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA tests) at week 4 were treated for 48 weeks (group C, Fig. 1). After the end of treatment, all patients were followed for an additional 24-week period.

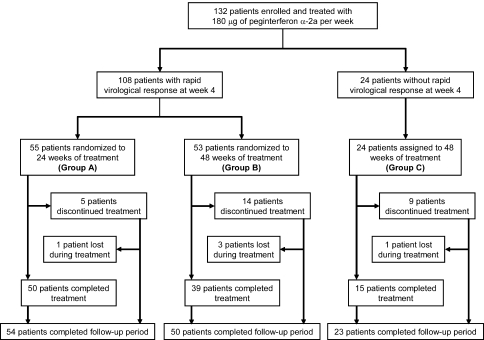

Fig. 1.

Trial profile. Patients were randomized at week 8 for a total treatment duration of 24 (group A) or 48 (group B) weeks on the basis of the virological response at week 4. Patients who withdrew prematurely from treatment were encouraged to return for follow-up. For this reason, the number of patients who completed follow-up is higher than the number of patients who completed treatment

The study was approved by ethics committee of each center and carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. Enrollment started in March 2004 and ended in December 2005.

Virological and histological evaluation

Serum HCV RNA was detected by qualitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR, Amplicor HCV, Roche Diagnostics Japan, Tokyo, Japan; low limit of detection 50 IU/ml). The serum HCV load was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Amplicor HCV Monitor Test, Version 2.0, Roche Diagnostics Japan; low limit of detection 500 IU/ml). HCV RNA genotype was determined by RT-PCR with genotype-specific primers [20] or by serological grouping of serum antibodies determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (SRL Inc., Hachi-Oji, Tokyo) according to the method of Tanaka et al. [21] assuming that genotypes 1a and 1b corresponded to serological group 1 (genotype 1) and genotypes 2a and 2b corresponded to serological group 2 (genotype 2) [22].

Most patients underwent liver biopsy before therapy. In 40 patients, a liver biopsy was not available because the patients declined to have a biopsy specimen taken. Histopathological results were classified by local pathologists according to the METAVIR criteria reported previously [23, 24]. Treatment commenced within 12 months of liver biopsy.

Follow-up of patients

Patients were evaluated as outpatients for treatment safety, tolerance, and efficacy by each attending physician every week during treatment and every 4 weeks after the end of treatment for the rest of the study period.

Assessment of efficacy

During treatment, HCV RNA was quantified by PCR assay and was tested by qualitative test if HCV RNA became undetectable by the quantitative test. The end-of-treatment response (ETR) and SVR were assessed by qualitative PCR assay. ETR was defined as an undetectable serum HCV RNA level at the end of treatment. SVR was defined as an undetectable serum HCV RNA level by the end of treatment and throughout the follow-up period.

Safety analysis

Patients were assessed for safety and tolerance by the attending physician by monitoring adverse events and laboratory abnormalities. The study protocol permitted dose modification for patients who had clinically significant adverse events or important abnormalities in laboratory values. Adverse events were handled according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer for peginterferon α-2a, and therapy adjustments were applied. In general, dose reductions and discontinuation of therapy, if any, were made following the recommendations of the manufacturer. The dose was also reduced or the drug was discontinued at the discretion of the investigator at each of the participating clinical centers on the basis of the results of hematological, neuropsychiatric, and cutaneous or other adverse effects that were considered related to the medication. The dose of peginterferon could be restored to their original levels upon resolution of the event or abnormality.

Adherence to therapy was assessed as described previously [15], namely, by calculating the actual doses of IFN received as a percentage of the expected dose. Thus, patients who received 80% or more of their total IFN doses for 80% or more of the expected duration of therapy were considered to be 80% adherent. The dose of peginterferon received during the first 4 weeks was also assessed.

Sample size

The noninferiority margin was set at 10% between groups A and B. To obtain 80% statistical power with one-sided 5% significance level, a sample size of 81 patients per treatment group was necessary. With a dropout rate of 10% allowed, 90 patients per group were to be recruited. It was assumed that 70% of the patients would have undetectable HCV RNA at week 4. On the basis of this, the original plan specified enrollment of 270 patients to ensure randomization of an adequate number of patients at week 8. However, the Japanese Bureau of National Health Insurance started to provide reimbursement for peginterferon α-2b and ribavirin therapy for patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and high viral load or re-treatment irrespective of viral load since December 2005 and thus difficulty in new enrollment was anticipated; the enrollment was terminated by the end of the year.

Statistical analysis

Intention-to-treat analysis was used for all measures of efficacy. Patients who missed the examination at the end of the follow-up period were considered not to have had a response at that point. Patients who received at least one dose of study medication were included in the analysis of safety. The primary objective of the study was to establish the difference in SVR rates between treatment groups A and B.

Differences in baseline clinical characteristics, efficacy, and safety between the treatment groups were compared statistically by analysis of variance, χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Kruskal–Wallis test, where appropriate, using SAS, Version 9.1.3, software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to establish those factors that contributed to the efficacy of peginterferon α-2a monotherapy. Variables with more than marginal statistical significance (P < 0.10) in univariate analysis were entered into multivariate analysis. A risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval was denoted for each analysis. Unless otherwise stated, P values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

This study was performed between March 2004 and June 2007 at 33 centers in Japan. On the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 132 patients were enrolled (Fig. 1): 17 (13%) and 115 (87%) patients were infected with HCV genotypes 1 and 2, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, biochemical, molecular, and histological profiles of patients at baseline

| All patients | HCV RNA (kIU/ml) at week 4 | P-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <500 | ≥500 | |||

| Patients, n | 132 | 108 | 24 | |

| Gender, male/female (% male) | 81/51 (61) | 68/40 (63) | 13/11 (54) | 0.423‡ |

| Age (years)a | 56.4 ± 12.2 | 56.0 ± 12.2 | 57.8 ± 12.2 | 0.536§ |

| Weight (kg)a | 61.5 ± 12.6 | 62.0 ± 13.1 | 58.6 ± 9.5 | 0.257§ |

| Naive/re-treatment | 119/13 | 98/10 | 21/3 | 0.704# |

| Fibrosis staging, n (F1/F2/F3/F4) | 57/26/8/1 | 48/22/6/1 | 9/4/2/0 | 0.881‡ |

| Grading, n (A0-1/A2/A3) | 52/38/2 | 44/31/2 | 8/7/0 | 0.868‡ |

| Genotype, 1/2 (% genotype 1) | 17/115 (13) | 15/93 (14) | 2/22 (8) | 0.737# |

| HCV RNA (kIU/ml)b | 285 (46–1620) | 130 (37–1006) | 1350 (360–3060) | <0.001¶ |

| ALT (IU/l)b [7–42]c | 66 (35–117) | 64 (36–119) | 69 (31–109) | 0.571¶ |

| γ-GTP (IU/l)b [5–50]c | 45 (24–92) | 54 (26–97) | 33 (21–49) | 0.014¶ |

| Neutrophil count (/μl)a [1000–7500]c | 2844 ± 1036 | 2898 ± 1042 | 2615 ± 996 | 0.230§ |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl)a [13.5–17.5]c | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 14.1 ± 1.2 | 14.0 ± 1.4 | 0.751§ |

| Platelet count (103/μl)a [150–400]c | 175 ± 63 | 179 ± 66 | 155 ± 40 | 0.089§ |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GTP gamma glutamyl transpeptidase

†Comparison between groups according to HCV RNA at week 4

‡Chi-square test

#Fisher’s exact test

§Unpaired-t test

¶Mann–Whitney U-test

Data are a mean ± SD or b median (interquartile range), c normal range

Virological response

After 4 weeks of treatment with peginterferon α-2a, HCV RNA was below 500 IU/ml in 108 of 132 (82%) patients (Fig. 1). Among these 108 patients with RVR, HCV RNA was undetectable by qualitative test in 97 of 108 (90%) patients, whereas it was not tested by qualitative test in the rest of the patients. The RVR was achieved by 15 of 17 (88%) patients infected with HCV genotype 1 and low viral load and by 93 of 115 (81%) patients infected with HCV genotype 2 (P = 0.737). These patients were randomly assigned to group A (n = 55) and group B (n = 53). Patients with HCV RNA of 500 IU/ml or higher at week 4 were assigned to group C (n = 24) (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in baseline parameters between groups A and B (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline profiles between groups A (24 weeks) and B (48 weeks)

| Group A | Group B | P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 55 | 53 | |

| Gender, male/female (% male) | 35/20 (64) | 33/20 (62) | 0.883‡ |

| Age (years)a | 56.9 ± 11.3 | 55.2 ± 13.1 | 0.473§ |

| Weight (kg)a | 59.9 ± 11.6 | 64.3 ± 14.3 | 0.087§ |

| Naive/re-treatment | 48/7 | 49/4 | 0.374# |

| Fibrosis staging, n (F1/F2/F3/F4) | 26/12/2/0 | 22/10/4/1 | 0.558‡ |

| Grading, n (A0-1/A2/A3) | 28/11/1 | 16/20/1 | 0.097‡ |

| Genotype, 1/2 (% genotype 1) | 9/46 (16) | 6/47 (11) | 0.580# |

| HCV RNA (kIU/ml)b | 190 (35–1660) | 120 (38–580) | 0.282¶ |

| ALT (IU/l)b [7–42]c | 70 (37–117) | 59 (36–120) | 0.813¶ |

| γ-GTP (IU/l)b [5–50]c | 43 (26–78) | 63 (28–116) | 0.242¶ |

| Neutrophil count (/μl)a [1000–7500]c | 2936 ± 1047 | 2859 ± 1088 | 0.711§ |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl)a [13.5–17.5]c | 14.1 ± 1.0 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | 0.943§ |

| Platelet count (103/μL)a [150–400]c | 177 ± 47 | 181 ± 81 | 0.793§ |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GTP gamma glutamyl transpeptidase

†Comparison between groups A and B

‡Chi-square test

#Fisher’s exact test

§ Unpaired t-test

¶Mann–Whitney U test

Data are a mean ± SD or b median (interquartile range), c normal range

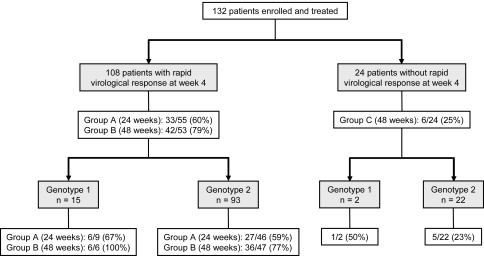

An overall intention-to-treat virological response at the ETR was achieved in 122 of 132 (92%) patients and SVR in 81 of 132 (61%) patients. In groups A and B, 53 of 55 (96%) patients and 51 of 53 (96%) patients achieved ETR and 33 of 55 (60%) patients and 42 of 53 (79%) patients achieved SVR, respectively (Fig. 2). The SVR rate was significantly higher in patients randomized to 48 weeks of therapy (group B) than in those randomized to 24 weeks of therapy (group A) (P = 0.030), namely, the relapse rate in group A was 40% (22/55), which was significantly higher than in group B (21%, 11/53, P = 0.030). Among patients with RVR confirmed by qualitative test (HCV RNA < 50 IU/ml), 29 of 48 (60%) patients achieved SVR in group A vs. 39 of 46 (85%) in group B (P = 0.008). The ETR and SVR rates in patients who did not show RVR and who were treated for 48 weeks (group C) were lower than in those who showed RVR (groups A and B) (75% vs. 96%, P = 0.003 for ETR and 25% vs. 69%, P < 0.001 for SVR, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sustained virological response rate according to genotype in each treatment group

Virological response according to HCV genotype and pretreatment viral load

The SVR rate in HCV genotype 1 and low viral load were not significantly different between treatment groups A and B (67% vs. 100%, respectively; P = 0.229) (Fig. 2), although the number of patients of this subgroup was small for meaningful comparison.

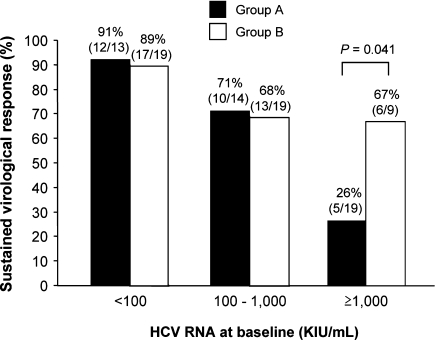

The SVR rate in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 was higher in group B (77%) than in group A (59%, P = 0.065). There was an inverse correlation between SVR rate and baseline viral load (Fig. 3). This observation was significant in group A (P < 0.001) but not in group B (P = 0.096). On the basis of receiver operating characteristics analysis, 1,000,000 IU/ml was optimal for use as the cutoff point of baseline viral load to best discriminate patients who might achieve SVR in group A. The SVR rate of patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and a baseline viral load below 1,000,000 IU/ml was not compromised by 24-week treatment (group A) compared with 48-week treatment (group B) (81% and 79%, respectively), without significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.801). On the other hand, the SVR rate in those with a baseline viral load of 1,000,000 IU/ml or higher was significantly lower in group A than in group B (26% and 67%, respectively, P = 0.041) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sustained virological response (SVR) rates stratified according to pretreatment HCV RNA level for patients of groups A (24 weeks) and B (48 weeks) infected with HCV genotype 2. The SVR rate was significantly lower in patients with higher baseline viral load in group A (P < 0.001) but not in group B (P = 0.096). The SVR rate in patients with a baseline viral load of less than 1,000,000 IU/ml was similar between group A (81%, 22/27) and group B (79%, 30/38) (P = 0.801). However, the SVR rate in those with a baseline viral load of 1,000,000 IU/ml or higher was lower in group A (26%, 5/19) than in group B (67%, 6/9) (P = 0.041)

Factors associated with RVR

Next, we analyzed the factors associated with RVR using data of all patients. The variables included were demographic features, baseline viral load, liver enzymes, and administered dose of peginterferon during the first 4 weeks (Table 3). Pretreatment HCV RNA level was lower and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) level and platelet count were higher in patients with RVR (groups A and B) than in those without RVR (group C) (Table 1). On the basis of receiver operating characteristic analyses, 41 IU/l and 191 × 103/μl were optimal for use as the cutoff points of baseline γ-GTP level and platelet count, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified low baseline viral load (<1,000,000 IU/ml), high γ-GTP level (≥41 IU/l), and high platelet count (≥191 × 103/μl) were significant determinants of RVR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with rapid virological response

| Variable | RR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Pretreatment variables | ||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.438 (0.589–3.513) | 0.425 |

| Age (<55 vs. ≥55 years) | 1.536 (0.583–4.049) | 0.512 |

| Weight (≥60 vs. <60 kg) | 2.511 (0.938–6.723) | 0.067 |

| Treatment (naive vs. re-treatment) | 1.400 (0.354–5.530) | 0.631 |

| Genotype (1 vs. 2) | 1.773 (0.377–8.333 | 0.468 |

| Fibrosis staging (F2-4 vs. F0-1)† | 1.104 (0.356–3.425) | 0.865 |

| Grading (A2-3 vs. A0-1)† | 1.167 (0.384–3.546) | 0.786 |

| HCV RNA (kIU/mL) | ||

| <100 | 1 | |

| 100–1000 | 0.562 (0.140–2.251) | 0.415 |

| ≥1000 | 0.159 (0.048–0.526) | 0.003 |

| ALT (≥60 vs. <60 IU/l) | 1.437 (0.579–3.571) | 0.435 |

| γ-GTP (IU/l) (≥41 vs. <41 IU/l) | 3.946 (1.504–10.352) | 0.005 |

| Neutrophil count (≥2500 vs. <2500/μL) | 1.135 (0.465–2.771) | 0.782 |

| Hemoglobin (<14 vs. ≥14 g/dl) | 1.427 (0.582–3.497) | 0.437 |

| Platelet count (≥191 vs. <191 × 103/μL) | 6.567 (1.466–29.424) | 0.014 |

| Treatment-associated variables | ||

| Adherence during 4 weeks of treatment (≥80% vs. <80%) | 1.714 (0.419–7.011) | 0.453 |

| Stepwise multivariate analysis | ||

| HCV RNA (kIU/ml) | ||

| <100 | 1 | |

| 100–1000 | 0.399 (0.091–1.759) | 0.225 |

| ≥1000 | 0.126 (0.034–0.464) | 0.002 |

| Platelet count (≥191 vs. <191 × 103/μl) | 10.230 (2.056–50.902) | 0.005 |

| γ-GTP (IU/l) (≥41 vs. <41 IU/l) | 3.989 (1.355–11.744) | 0.012 |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GTP gamma glutamyl transpeptidase

†A biopsy was not available from 40 patients

Factors associated with SVR

Next, the factors associated with SVR were analyzed using data of all patients. Univariate analysis indicated that grading score, pretreatment viral load, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and γ-GTP levels, neutrophil count, RVR, and adherence to treatment were associated with SVR. On the basis of receiver operating characteristic analyses, 41 IU/l, 28 IU/l, and 3,155/μl were optimal for use as the cutoff points of baseline ALT level, γ-GTP level, and neutrophil count, respectively. Multivariate analysis was performed with the following variables: pretreatment viral load, ALT and γ-GTP levels, neutrophil count, RVR, and adherence to treatment but excluding grading score due to a significant association with ALT level and a substantial number of cases (40 cases) missing histological data. The analysis identified low viral load (<100,000 IU/ml), RVR, high ALT level (≥41 IU/l), and high γ-GTP level (≥28 IU/l) as independent determinants of SVR (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with sustained virological response

| Variable | RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Pretreatment variables | ||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.190 (0.581–2.438) | 0.635 |

| Age (≥55 vs. <55 years) | 1.273 (0.618–2.625) | 0.512 |

| Weight (<60 vs. ≥60 kg) | 1.064 (0.520–2.175) | 0.865 |

| Treatment (re-treatment vs. naive) | 1.468 (0.428–5.051) | 0.541 |

| Genotype (1 vs. 2) | 2.247 (0.690–7.299) | 0.179 |

| Fibrosis staging (F2-4 vs. F0-1)† | 1.964 (0.812–4.749) | 0.134 |

| Grading (A2-3 vs. A0-1)† | 4.343 (1.727–10.922) | 0.002 |

| HCV RNA (kIU/mL) <100 | 1 | |

| 100–1000 | 0.367 (0.138–0.975) | 0.044 |

| ≥1000 | 0.115 (0.044–0.298) | <0.001 |

| ALT (≥41 vs. <41 IU/l) | 4.570 (2.104–9.927) | <0.001 |

| γ-GTP (IU/l) (≥28 vs. <28 IU/l) | 6.182 (2.657–14.384) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil count (<3155 vs. ≥3155/μl) | 3.135 (1.479–6.623) | 0.003 |

| Hemoglobin (≥14 vs. <14 g/dl) | 1.125 (0.555–2.283) | 0.744 |

| Platelet count (<150 vs. ≥150 × 103/μl) | 1.091 (0.507–2.347) | 0.824 |

| Treatment-associated variables | ||

| RVR (yes vs. no) | 6.818 (2.482–18.733) | <0.001 |

| Adherence (≥80% vs. <80%) | 1.940 (0.949–3.966) | 0.070 |

| Stepwise Multivariate Analysis‡ | ||

| HCV RNA (kIU/ml) | ||

| <100 | 1 | |

| 100–1000 | 0.165 (0.046–0.589) | 0.006 |

| ≥1000 | 0.102 (0.029–0.352) | <0.001 |

| RVR (yes vs. no) | 6.223 (1.821–21.305) | 0.003 |

| ALT (≥41 vs. <41 IU/l) | 4.775 (1.373–16.601) | 0.014 |

| γ-GTP (IU/l) (≥28 vs. <28 IU/l) | 3.466 (1.092–11.000) | 0.035 |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GTP gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, RVR rapid virological response

†A biopsy was not available from 40 patients

‡Grading was not included

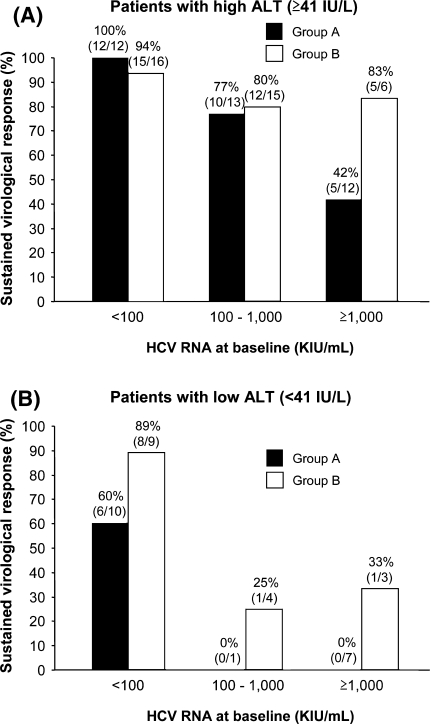

Multivariate analysis for factors associated with SVR in patients with RVR identified low viral load (<100,000 IU/ml) and high ALT level (≥41 IU/l) as independent determinants of SVR. The SVR rates in patients with RVR and with high ALT levels (≥41 IU/l) were generally high except for group A patients with high viral load (≥1,000,000 IU/ml). On the other hand, the SVR rates for both groups A (black bars) and B (open bars) were entirely low in patients with low ALT levels (<41 IU/l) except those with low viral load (<100,000 IU/ml) (Fig. 4). In patients with high viral load (≥100,000 IU/ml) and low ALT levels (<41 IU/l), SVR was achieved only in group B patients, though at low rate.

Fig. 4.

Sustained virological response (SVR) rates stratified according to pretreatment HCV RNA and ALT levels in group A and B patients. The SVR rates in patients with high (≥41 IU/l) and low (<41 IU/l) ALT levels are shown in panels a and b, respectively. a The SVR rates in patients with high ALT levels (≥41 IU/l) were generally high except for group A patients with high viral load (≥1,000,000 IU/ml). b The SVR rates in both groups A and B were low in patients with low ALT levels (<41 IU/l) except those with low viral load (<100,000 IU/ml)

Safety

Twenty-eight (21%) patients discontinued therapy and 14 of them discontinued because of adverse events, 4 because of laboratory abnormalities, 3 because of refusal of treatment, 2 because of insufficient response, and 5 because of failure to return (Table 5). Fatigue was the most common adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy. The frequencies of discontinuation and discontinuation due to adverse events were significantly lower in the 24-week treatment group (group A) than in the 48-week treatment group (groups B and C) (9% vs. 30%, P = 0.005 and 4% vs. 16%, P = 0.042, respectively).

Table 5.

Incidence and reason of discontinuation according to treatment group

| Variable | All patients | Age (years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||

| n | 132 | 55 | 53 | 24 |

| Discontinuation | 28 (21) | 5 (9) | 14 (26) | 9 (38) |

| Adverse events | 14 (11) | 2 (4) | 8 (15) | 4 (17) |

| Fatigue | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Depression | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Arrhythmia | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pyrexia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Colon cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Laboratory abnormality | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| High aminotransferase | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Anemia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Refusal of treatment | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) |

| Insufficient response | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (4) |

| Failure to return | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 1 (4) |

Data are number of patients (percentage in each patient group)

Adherence to scheduled therapy (median and interquartile range) was 100% (63–100%), 77% (54–100%), and 85% (55–100%), respectively, for groups A, B, and C (P = 0.012 by Kruskal–Wallis test). The rate of adherence in group A was higher than in groups B and C (P = 0.003 and P = 0.082, respectively, by Mann–Whitney U test). There was no difference in adherence to therapy between groups B and C (P = 0.597). Thus, adherence to therapy in the longer treatment course (48 weeks) was lower than in the shorter treatment course (24 weeks).

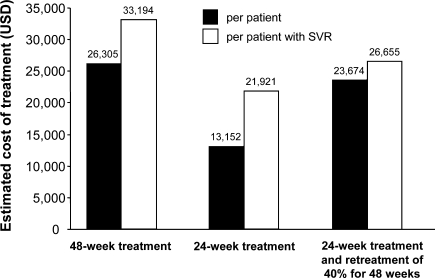

Costs

Based on the current prices in the United States, spending on medication for 48 weeks of peginterferon α-2a monotherapy is $26,305 and that for 24 weeks treatment is $13,152. If we consider re-treatment for 48 weeks of the 40% of patients with RVR who relapse after 24 weeks of treatment, the mean cost of treating HCV genotype 2 infection or low viral load HCV genotype 1 patients with RVR would be $23,674 (Fig. 5). Thus, if all relapsers after 24 weeks of treatment receive re-treatment for 48 weeks, the mean saving per patient with this concept vs. 48 weeks to all would be $2,630 (10%).

Fig. 5.

The cost of treating patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or low viral load genotype 1 and RVR for 48, 28, or 24 weeks followed by 48 weeks of re-treatment of 40% of patients who relapse after the initial treatment

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 and low viral load (<1,000,000 IU/ml) who achieve RVR, 24-week treatment with peginterferon α-2a alone may be sufficient in terms of efficacy. Patients treated for 24 weeks also discontinued treatment less frequently and showed higher adherence than those treated for 48 weeks. Furthermore, the drug cost can be reduced by truncating treatment duration. Thus, by reducing the treatment period, these patients can avoid unnecessary treatment without compromising the chance for an SVR. In particular, the SVR rate in patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and low viral load (<1,000,000 IU/ml) who achieved RVR was as high as 81% by 24-week monotherapy. The SVR rate was comparable with that (84%, 81/96) reported previously in patients with HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection who received 24-week combination therapy of peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin [7], although the latter included patients with HCV genotype 3 infection. On the other hand, the results of this study were not conclusive regarding patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and low viral load (<100,000 IU/ml). Further prospective controlled trial is warranted to confirm our findings in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and low viral load or HCV genotype 2 infection and baseline viral loads of less than 1,000,000 IU/ml who achieve RVR.

In patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and high viral load (≥1,000,000 IU/ml), the SVR rate was lower for the 24-week treatment group than for the 48-week treatment group, even if the patients achieved RVR. Thus, a longer treatment (>24 weeks) with peginterferon is recommended for this group of patients. Furthermore, since the SVR rate was not more than 67% in this subgroup of patients, even if they were treated for 48 weeks, a combination with ribavirin or further extended treatment duration may be necessary as long as patients can tolerate the treatment.

The combination therapy of peginterferon and ribavirin is currently the therapeutic standard for chronic hepatitis C. However, the combination therapy tends to be associated with adverse events more frequently than those that occur with IFN monotherapy, resulting in dose reduction or discontinuation of therapy and thus impaired response rate [9–14]. This is true particularly in elderly patients. In a country such as Japan where the average age of patients with chronic hepatitis C to be treated by antivirals sometimes is well above 60, standard combination therapy is not well tolerated [15]. For example, in a phase III study of 48-week peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin combination therapy conducted in Japan [25], the SVR rate in the combination arm (78%, 18/23) was rather inferior to that of peginterferon α-2a monotherapy (placebo) arm (100%, 14/14) among patients with RVR (P = 0.061), although the difference did not reach statistical significance. In the same study, all of the patients who failed to achieve SVR in the combination arm discontinued treatment [25]. Thus, the combination therapy with ribavirin does not always lead to a better response than with monotherapy, at least in a subgroup of patients. It is noteworthy that most of the patients in the present trial were those who preferred peginterferon α monotherapy to combination therapy in spite of the coverage for the latter therapy by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, as described previously.

In addition to elderly patients, those with renal failure, ischemic vascular diseases, and congenital hemoglobin abnormalities never tolerate ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C treatment [26]. Therefore, data on peginterferon α monotherapy are particularly relevant to these patients. The possibility of shorter combination therapy with peginterferon α and ribavirin in easy-to-treat patients such as those chronically infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3 has been investigated in several trials [27–31]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no randomized, controlled trial to identify optimal treatment duration of peginterferon α monotherapy. A further prospective randomized, controlled trial aiming at patients who cannot receive combination therapy with ribavirin is warranted.

A high ALT level has been identified as a significant factor for SVR [18]. The reason why patients with low or normal ALT levels do not respond well to peginterferon α monotherapy is currently unknown. The SVR rates were low in our patients with low ALT levels and HCV RNA levels of 100,000 IU/ml or higher in the two randomized groups (Fig. 4). Thus, these patients may not benefit by simply extending therapy from 24 to 48 weeks. Since a similar efficacy has been demonstrated in patients with persistently normal ALT levels compared with those with elevated ALT levels by combination therapy of peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin [32], combination therapy should be considered for these patients.

A high γ-GTP level was unexpectedly identified as a factor for both RVR and SVR, independent of ALT levels. Again, the reason for this finding is unknown at present. It is well known that a low γ-GTP level is associated with SVR to combination therapy comprising peginterferon and ribavirin; the reason also being unexplained so far [33]. Thus, the present finding at least suggests that entirely different mechanisms may underlie these observations.

In this trial, RVR was defined as serum HCV RNA level below 500 IU/ml at week 4, although most of the patients who achieved RVR had HCV RNA levels below 50 IU/ml. The criterion of RVR used in this study was less strict than those reported recently, in which serum HCV RNA level below 50 IU/ml at week 4 has been utilized [30, 31]. This may result in a higher rate of achieving RVR and lower SVR rates, resulting in more relapsers, particularly in patients treated for a shorter duration of 24 weeks than a standard duration of 48 weeks. By using more strict criteria of serum HCV RNA level below the detection limit of qualitative PCR (≤50 IU/ml) at week 4 or negativity of HCV RNA at earlier time points during therapy, such as at week 2 [34], a subgroup of patients, who can be sufficiently treated with a shorter duration of therapy (such as 24 weeks) without compromising the chance for SVR, could be more specifically identified.

In conclusion, patients infected with HCV genotype 2 and have low baseline viral load (<1,000,000 kIU/ml), who can achieve RVR, can satisfactorily be treated for 24 weeks with peginterferon α-2a alone without compromising the SVR. We propose that these patients should first be treated with peginterferon α monotherapy for 24 weeks, as long as RVR is achieved, otherwise they should be switched to combination therapy with ribavirin at the time for another 24–48 weeks, depending on the response thereafter. However, the data of this study are less conclusive for patients with low viral load genotype 1 or 2 and viral load of more than 1,000,000 IU/ml. Additional trials are required to optimize treatment schedule in these patients.

Acknowledgments

Investigators who participated in this study are as follows (listed in alphabetical order): K. Abe (Iwate Medical University), M. Ando (Mitoyo General Hospital), Y. Araki (Hiroshima City Hospital), A. Asagi (Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital), N. Enomoto (Juntendo University), K. Hamamura (Shizuoka General Hospital), Y. Hiasa (Ehime University), S. Hige (Hokkaido University), T. Ide (Kurume University), J. Inoue (Hiroshima Teishin Hospital), Y. Ishii (Tottori City Hospital), Y. Iwasaki (Okayama University), N. Izumi (Musashino Red Cross Hospital), K. Joko (Matsuyama Red Cross Hospital), H. Jomura (Wakakoukai Hospital), S. Kakizaki (Gunma University), Y. Kamishima (Tomakomai-Nisshou Hospital), F. Kanai (University of Tokyo), S. Kaneko (Kanazawa University), J-H. Kang (Teine-Keijinkai Hospital), N. Kawada (Osaka City University), S. Kawano (Tottori City Hospital), S. Kawazoe (Saga Prefectural Hospital Kouseikan), K. Kita (Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital), T. Kitamura (Musashino Red Cross Hospital), H. Kobashi (Tsuyama Central Hospital), Y. Kohgo (Asahikawa Medical College), H. Kokuryu (Shizuoka General Hospital), S. Konishi (Tomakomai-Nisshou Hospital), N. Masaki (International Medical Center of Japan), S. Matsumura (Mitoyo General Hospital), S. Minamitani (Aioi Hospital), T. Mizuta (Saga Medical School), M. Moriyama (Nihon University). J. Nishiguchi (Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital), S. Nishiguchi (Hyogo College of Medicine), S. Nishimura (Musashino Red Cross Hospital), K. Nouso (Hiroshima City Hospital), T. Ohtake (Asahikawa Medical College), R. Okamoto (Hiroshima City Hospital), H. Okushin (Himeji Red Cross Hospital), M. Omata (University of Tokyo), M. Onji (Ehime University), H. Saito (Keio University), M. Sata (Kurume University), N. Sato (Juntendo University), S. Sato (Teikyo University Hospital, Mizonokuchi), T. Senoh (Takamatsu Red Cross Hospital), A. Shibuya (Kitasato University Hospital), Y. Shiratori (Okayama University), N. Sohara (Gunma University), K. Suzuki (Iwate Medical University), Y. Suzuki (Sano Hospital), H. Takagi (Gunma University), K. Takaguchi (Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital), Y. Tanaka (Matsuyama Red Cross Hospital), R. Terada (Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital), K. Ueda (Musashino Red Cross Hospital), K. Yamamoto (Saga Medical School), and H. Yoshida (University of Tokyo).

Conflict of interest statement None declared.

Footnotes

This study is conducted on behalf of the Japanese Consortium for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Clinical Trial Registry: www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm; identifier: UMIN000001067.

References

- 1.El Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:817–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S35–S46. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, Martinot M, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, et al. Long-term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:875–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederau C, Lange S, Heintges T, Erhardt A, Buschkamp M, Hurter D, et al. Prognosis of chronic hepatitis C: results of a large, prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 1998;28:1687–1695. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings KJ, Lee SM, West ES, Cid-Ruzafa J, Fein SG, Aoki Y, et al. Interferon and ribavirin vs interferon alone in the re-treatment of chronic hepatitis C previously nonresponsive to interferon: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:193–199. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, Trepo C, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1493–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kjaergard LL, Krogsgaard K, Gluud C. Interferon alfa with or without ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C: systematic review of randomised trials. Br Med J. 2001;323:1151–1155. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maddrey WC. Safety of combination interferon alfa-2b/ribavirin therapy in chronic hepatitis C-relapsed and treatment-naive patients. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(Suppl 1):67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT) Lancet. 1998;352:1426–1432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwasaki Y, Ikeda H, Araki Y, Osawa T, Kita K, Ando M, et al. Limitation of combination therapy of interferon and ribavirin for older patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:54–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heathcote EJ, Shiffman ML, Cooksley WG, Dusheiko GM, Lee SS, Balart L, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1673–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, Shiffman ML, Gordon SC, Hoefs JC, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;34:395–403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Data on file. PEGASYS. Tokyo (Japan): Chugai Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2002.

- 20.Okamoto H, Sugiyama Y, Okada S, Kurai K, Akahane Y, Sugai Y, et al. Typing hepatitis C virus by polymerase chain reaction with type-specific primers: application to clinical surveys and tracing infectious sources. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:673–679. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-3-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka T, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Yamaguchi K, Yagi S, Tanaka S, Hasegawa A, et al. Significance of specific antibody assay for genotyping of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1994;19:1347–1353. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiratori Y, Kato N, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Hashimoto E, Hayashi N, et al. Predictors of the efficacy of interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Tokyo-Chiba Hepatitis Research Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:558–566. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513–1520. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai T, Iino S, Okuno T, Omata M, Kiyosawa K, Kumada H, et al. High response rates with peginterferon alfa-2a (40 KD) (PEGASYS) plus ribavirin (COPEGUS) in treatment-naive Japanese chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase III trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(Suppl):A839. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dienstag JL, McHutchison JG. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:231–264. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagging M, Langeland N, Pedersen C, Farkkila M, Buhl MR, Morch K, et al. Randomized comparison of 12 or 24 weeks of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 2/3 infection. Hepatology. 2008;47:1837–1845. doi: 10.1002/hep.22253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiffman ML, Suter F, Bacon B, Nelson D, Harley H, Sola R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in HCV genotype 2 or 3. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:124–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner M, Huber M, Berg T, Hinrichsen H, Rasenack J, Heintges T, et al. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40 kD) and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 or 3 chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Hou NJ, Lee LP, Hsieh MY, et al. A randomised study of peginterferon and ribavirin for 16 versus 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2007;56:553–559. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.102558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalgard O, Bjøro K, Ring-Larsen H, Bjornsson E, Holberg-Petersen M, Skovlund E, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin for 14 versus 24 weeks in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 and rapid virological response. Hepatology. 2008;47:35–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeuzem S, Diago M, Gane E, Reddy KR, Pockros P, Prati D, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kilodaltons) and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C and normal aminotransferase levels. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1724–1732. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg T, Sarrazin C, Herrmann E, Hinrichsen H, Gerlach T, Zachoval R, et al. Prediction of treatment outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis C: significance of baseline parameters and viral dynamics during therapy. Hepatology. 2003;37:600–609. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong S, Kawakami Y, Kitamoto M, Ishihara H, Tsuji K, Aimitsu S, et al. Prospective study of short-term peginterferon-alpha-2a monotherapy in patients who had a virological response at 2 weeks after initiation of interferon therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:541–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]