Abstract

Monitoring waters for indicator bacteria is required to protect the public from exposure to fecal pollution. Our proof-of-concept study describes a method for detecting fecal coliforms. The coliform Escherichia coli was used as a model fecal indicator. DNA probe-coated magnetic beads in combination with the electrochemical monitoring of the oxidation state of guanine nucleotides should allow for direct detection of bacterial RNA. To demonstrate this concept, we used voltammetry in connection with pencil electrodes to detect isolated E. coli 16S rRNA. Using this approach, 107 cells of E. coli were detected in a quantitative, reproducible fashion in 4 h. Detection was achieved without a nucleic acid amplification step. The specificity of the assay for coliforms was demonstrated by testing against a panel of bacterial RNA. We also show that E. coli RNA can be detected directly from cell extracts. The method could be used for on-site detection and shows promise for adaptation into automated biosensors for water-quality monitoring.

Keywords: Biosensor, Fecal indicators, Fecal pollution, Monitoring, RNA, Water quality

1. Introduction

Waters polluted by human feces can have deleterious consequences to human health and the economy because of water-borne illness and closing of recreational and seafood harvesting waters (Cabelli et al., 1979, 1982; Dufour, 1984; Kay et al., 1994; Leclerc et al., 2002). Membersof the bacterial family Enterobacteriaceae are definned as facultatively anaerobic, gram-negative, non-endospore forming, rod-shaped bacteria that ferment lactose to form gas within 48 h of being placed in lactose broth at 35 °C (Tortora et al., 2001). This group of bacteria is often called enterics or coliforms, and includes Escherichia coli, Enterobacter and Klebsiella species (Tortora et al., 2001). The term coliform (or enteric) reflects the association of this group with the intestinal tracts of humans and other animals, and the presence of coliform bacteria (total, fecal, or a specific species) are used to indicate that water has been polluted with feces (EPA, 2000).

Standard culture-based methods used for testing microbiological water quality (EPA, 2000; Leclerc et al., 2002) are labor-intensive, costly, samples must be processed quickly (within 4 h), and there is at least a 24-h time delay between sample collection and availability of test results. Unfortunately, estimating levels of fecal pollution within dynamic, marine ecosystems based upon the test results of >1 day previously is not adequate to protect fully the public from potential health risks; especially given recent data indicating that concentrations of fecal indicators show extreme daily variability (Leecaster and Weisberg, 2001; Boehm et al., 2002). In addition, the required short processing time is a major burden to water quality sampling programs. Therefore, a need exists for the development of methods capable of rapidly, cheaply and accurately monitoring waters for the presence of fecal indicator microbes (Straub and Chandler, 2003; EST, 2004). Methods that can be used on-site or as part of an in situ biosensor, and thereby circumventing the need to return samples to the laboratory, are especially needed. In addition, quicker methods will provide microbial ecologists a needed tool to better describe the survival, distribution and metabolic state of fecal indicators in rapidly changing coastal ecosystems. Moreover, the rapid identification of aquatic microbes via in situ biosensors, combined with physical and chemical measurements of the environment, is critical to expanding our knowledge of coastal dynamics and the microbial processes that impact marine ecosystems such as the introduction and spread of microbial pollutants and the initiation of harmful algal blooms (Kroger et al., 2002).

Molecular biological techniques may have promise for improving fecal indicator monitoring (Kroger et al., 2002; Straub and Chandler, 2003). Nucleic acid detection methods are especially attractive due to their speed, sensitivity, selectivity and potential to be used on-site or integrated into automated, in situ biosensors capable of monitoring aquatic environments in real time (Kroger et al., 2002; Straub and Chandler, 2003; Glasgow et al., 2004). The most widely used nucleic acid detection schemes make use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify DNA signatures of microbial species; but nucleic acid amplification methods, including PCR, may not be ideal for microbial sampling of aquatic environments (e.g. fecal indicator monitoring) as they typically require expensive and complex instrumentation, are not always quantitative, and are prone to error due to inhibition of the amplification reaction by substances in water, i.e. humic compounds and colloidal matter (Reischl and Kochanowski, 1995; Orlando et al., 1998; Lantz et al., 2000; Loge et al., 2002). Additionally, PCR methods may amplify DNA extracted from non-viable cells, so contamination levels could be overestimated and inconsistent with actual public health threats (Keer and Birch, 2003).

Non-traditional nucleic acid detection methods, including those using analytical electrochemistry, have the potential to overcome the limitations of detection assays requiring a nucleic acid amplification step (e.g. PCR). Direct, electrochemical detection of nucleic acids from environmental samples not only could match the sensitivity, selectivity and speed of methods requiring an amplification step, but may also offer advantages over such assays as electrical methods use compact, lowcost devices that can be more easily integrated into automated biosensors (Wang, 2002; Drummond et al., 2003; Ng and Ilag, 2003; Kerman et al., 2004). Moreover, the inherent miniaturization of electrochemical detection systems makes them ever more attractive for meeting the requirements of on-site water quality testing.

Electrochemical detection of DNA/RNA often involves monitoring an electrical current response resulting from the hybridization of DNA probes to complementary target sequences under controlled potential conditions (Wang, 2000). Numerous approaches to electrochemical DNA detection have been formulated, including detection based upon intrinsic redox properties of nucleic acids, monitoring of DNA-specific redox reporters, use of enzyme or nanoparticle tags and tracking DNA-mediated charge transport (Drummond et al., 2003; Kerman et al., 2004). The majority of these approaches have been evaluated using synthetic oligonucleotides or PCR-amplified nucleic acids as hybridization targets. The use of these methods for the detection of nucleic acids from cells has proven to be challenging due to the complexity of native DNA and RNA molecules (Ng and Ilag, 2003).

Wang reported a novel strategy for label-free, electrical sensing of synthetic oligonucleotides based upon tracking the oxidation of target guanine nucleotides (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002). The use of DNA probe-coated magnetic beads that capture target sequences from complex samples, and thus provide a means for their selective purification, in combination with the electrochemical monitoring of the oxidation state of guanine nucleotides may allow for detection of native nucleic acids lysed from bacterial cells. To test this idea, and to show the applicability of electrochemical detection of nucleic acids to water quality monitoring, we used pulse voltammetry to detect RNA from a representative indicator bacteria, E. coli. The method outlined does not require a pre-amplification of target nucleic acids, can detect RNA directly from lysed cells, and has the potential to be used on-site or integrated into in situ biosensors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The concept

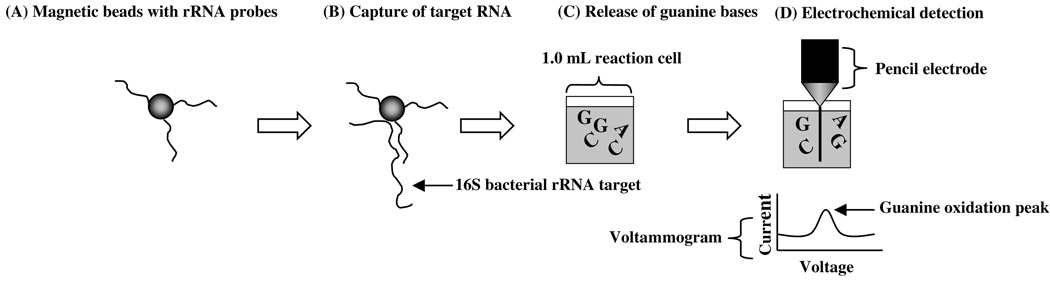

A schematic representation of the electrochemical RNA detection assay is shown in Fig. 1. First, streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, conjugated to biotin-labeled oligonucleotide probes (Fig. 1A, ENTI-2a-R), are hybridized to a sample containing 16S ribosomal RNA (Fig. 1B). Following a series of washes, RNA molecules hybridized to DNA probes are released from magnetic beads by treatment with base (NaOH). Next, a strong acid (H2SO4) is added to the reaction to release individual guanine nucleotides into solution (Fig. 1C). The guanine nucleotides are then detected at pencil graphite electrodes by monitoring their oxidation via electrochemistry (Fig. 1D, differential pulse voltammetry).

Fig. 1.

Outline of the electrochemical RNA hybridization assay. First, DNA probe-labeled (ENTI-2a-R oligonucleotide) magnetic beads (A) are hybridized to bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (B). After a series of washings and magnetic separation steps to remove non-specifically bound nucleic acids, guanine bases are released into solution from DNA probe-RNA assemblies by treatment with sulfuric acid (C). Lastly, released guanine bases are detected by pulse voltammetry at a pencil graphite electrode (D). The resultant voltammograms display current peaks, resulting from the oxidation of guanine, whose height is proportional to the amount of RNA hybridized to DNA probes (D).

2.2. Apparatus

Differential pulse voltammetric measurements were performed with a CH 1232 portable biopotentiostat (CH Instruments, Austin, Texas). The microsphere preparation and hybridization reactions were carried out with a MCB 1200 Biomagnetic Processing Platform (Dexter Magentic Technologies, Fremont, California). The three-electrode system included a graphite working electrode, a Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode.

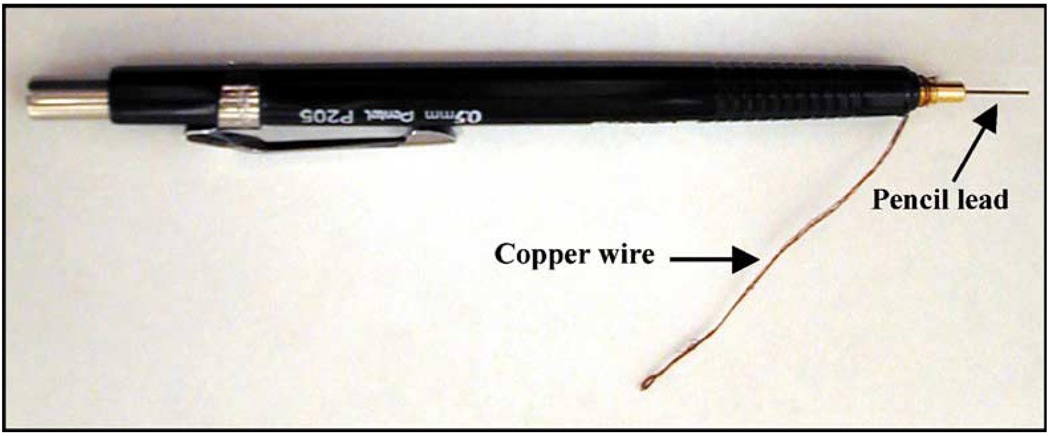

2.3. Electrode preparation

The preparation of pencil graphite electrodes was carried out as described earlier (Wang et al., 2000). In brief, a mechanical pencil Model P250 (Pentel Ltd., Japan) was used as a holder for the graphite lead. The pencil graphite leads (HI-POLYMER C505) were obtained from the same source. Electrical contact to the lead was achieved by wrapping a copper wire around the metallic part of the pencil that holds the graphite rod in place (Fig. 2). A total of 10 mm of fresh graphite (16.36 mm2 of active electrode area) was immersed in solution per measurement.

Fig. 2.

Preparation of pencil electrodes. A picture of a pencil electrode that is ready for the electrochemical detection of nucleic acids.

2.4. Materials and reagents

All stock reagents were prepared using deionized and autoclaved water. Stock reagents were of molecularbiology grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Proactive™ (paramagnetic) streptavidin-coated microspheres (CMO1N, lot 5776) were from Bang’s Laboratories Inc. (Fischers, Indiana).

2.5. Oligonucleotide probes

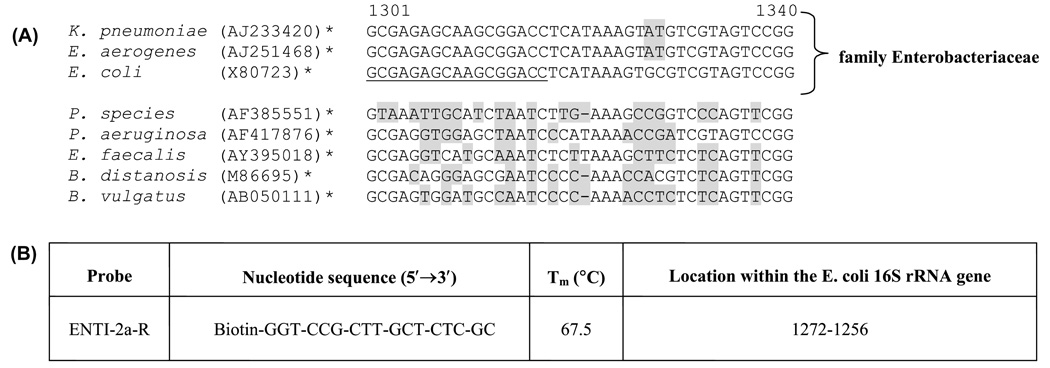

Biotin-modified oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Genosys Ltd. (The Woodlands, Texas). To evaluate the electrochemical assay, an oligonucleotide probe, ENTI (16S rRNA gene), was used for selective identification of bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriacae (Loge et al., 1999). The oligonucleotide sequence of ENTI was modified to remove predicted secondary structures, and thus enhance its usefulness as a probe in nucleic acid hybridization assays (Sohail et al., 1999). The specificity of the modified oligonuclotide, ENTI-2a-R, for Enterobacteriacae was verified by in silico analysis (Fig. 3). In brief, the 16S rRNA gene of the Enterobacteria E. coli (GenBank™ accession #X80724; ATCC 25922) was used as a BLAST 2.0 query sequence to retrieve representative nucleotide sequences from the GenBank™ database (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The retrieved 16S rRNA sequences were aligned using default parameters of the Align X command of the Vector NTI® Software Suite (Version 7, Bethesda, Maryland). OLIGO Primer Analysis Software (Molecular Biology Insights Inc., Cascade, Colorado) was used to estimate the melting temperature and potential secondary structures within ENTI-2a-R.

Fig. 3.

Oligonucleotide probe used in this study. Part (A) is a nucleotide sequence alignment of representative bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA genes, assembled according to Section 2.5. The position of probe ENTI-2a-R is underlined. The probe was designed to selectively hybridize to 16S rRNA from species belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae (coliforms or enterics). Individual bases not identical to corresponding probe bases are highlighted in grey. Numbers denoted by an asterisk (*) refer to GenBank™ sequence accession numbers, which can be retrieved at http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. The table marked (B) provides a summary of ENTI-2a-R including the nucleotide sequence, calculated melting temperature (Tm) and location within the E. coli 16S rRNA gene.

2.6. Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains of E. coli (ATCC 25922), Enterobacter aerogenes (ATCC 13048), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 35657) and Pseudomonas aeroginosa (ATCC 27853) were obtained from the American Type Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia). The bacterial isolates were recovered from −70 °C storage and grown aerobically, with shaking (120 RPM), at 37 °C for 15 h in autoclaved Nutrient Broth (Difco™ 233000). Bacteria were enumerated by spreading serial dilutions of the overnight cultures on sterile Nutrient Agar (Difco™ 212000). Plates were grown for 15 h at 37 °C and resultant bacterial colonies counted to express bacteria concentrations as colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of culture (Ausubel et al., 1999). The Enterococcus faecalis species was cultured and enumerated identically, except Luria-Bertani broth and agar were used as growth media.

2.7. Bacterial RNA isolation

For all species, total RNA from 109 CFU was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, California) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA isolated from 109 CFU was suspended in a final volume of 100 µL of nuclease-free water. Total RNA concentrations were determined by optical density readings at 260 nm using an Eppendorf® BioPhotometer (Hamburg, Germany). The purity and integrity of isolated RNA was assessed by spectroscopy and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively (Ausubel et al., 1999).

2.8. RNA hybridization procedure and voltammetric detection

Hybridization assays were carried out on an MCB 1200 Biomagnetic processing platform using a modified procedure recommended by Bangs Laboratories (Wang et al., 2000). For each hybridization reaction, 100 µg of streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were transferred to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. The beads were washed twice with 100 µL TTL buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 M LiCl) and suspended in 21 µL TTL buffer. Subsequently, 4 µL (1000 pM stock) of biotinylated capture probe, ENTI-2a-R, were added to the mixture and incubated for 20 min with gentle mixing. The probe-coated magnetic beads were then washed twice with 100 µL TT buffer and suspended in 50 µL of RNA hybridization buffer (3 M Guanidine Thiocyanate, 50 mM Tris, 15mM EDTA, 2% Sarkosyl, 0.2% SDS, pH 8.9). Ten microliter of isolated bacterial RNA were added per reaction, and allowed to hybridize to probecoated magnetic beads for 1 h at room temperature. Following a 1-h incubation, the resulting bead-RNA assemblies were washed twice for 1 min with 100 µL of sodium acetate buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.9). Next, the DNA probe-RNA hybrids were released from magnetic beads by treatment with 0.05 M NaOH (50 µL per reaction) for 5 min with gentle mixing. After a subsequent magnetic separation, the 50 µL NaOH solution (containing the DNA probes and bacterial RNA) was transferred to a 1.0 mL glass cell and 3 µL of 3 M H2SO4 was added to release individual guanine nucleotides into solution. In preparation for electroanalysis, the resultant solution was heated to dryness and nucleotides were re-suspended in 1.0 mL of 0.5 M Sodium Acetate (pH 5.9) buffer spiked with 2 µg (1 µg/µL stock in 1% HNO3) of Copper (II) in order to increase the electrochemical signal.

The detection of acid-released guanine bases was carried out at pencil graphite electrodes and in connection to a CH 1232 biopotentiostat. First, each pencil graphite electrode surface was pre-conditioned for 60 s at 1.4 V. Next, guanine nucleotides were accumulated at the graphite electrode for 120 s at −0.05 V. The accumulated guanine bases were then detected using a differential pulse voltammetric scan from 0.0 to +0.5 V with a rate of 15 mV s−1 and amplitude of 25 mV. The redox current peak data were filtered and baseline corrected using default parameters of the CH instrument software.

2.9. Detection of RNA directly from E. coli cell lysates

Approximately 109 CFU of E. coli were collected from a freshly grown culture (Section 2.6) by centrifugation for 1 min at 10 000 RPM in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. After removing the supernatant, the cell pellets were re-suspended in 1.0 mL of hybridization buffer to lyse cells (same as hybridization buffer in Section 2.8; 3 M Guanidine Thiocyanate, 50 mM Tris, 15 mM EDTA, 2% Sarkosyl, 0.2% SDS, pH 8.9) and heated at 85 °C for 10 min. Next, the resultant lysate was vortexed briefly (5–10 s) and passed through a 0.2 µM syringe filter (VWR International #28146-006, Rochester, New York) to remove cellular debris. The crude homogenate, containing ribosomal RNA, was used directly in the electrochemical detection scheme (Section 2.8). In brief, newly prepared probe-coated magnetic beads were suspended in filtered E. coli cell lysate and allowed to hybridize to target RNA for 1 h at room temperature. All other steps in the electrochemical scheme (Section 2.8) were identical to those used in the detection of isolated RNA.

3. Results

3.1. Assay design and rationale

We designed this study to explore the feasibility of using electrochemical, nucleic acid hybridization assays to detect aquatic microbes as a first step toward fielddeployable (i.e. on-site) instruments, including automated, in situ biosensors. As a result of three significant findings, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was selected as the hybridization target rather than genomic DNA. First, molecular methods able to simultaneously detect and determine the viability of target microbes from environmental reservoirs should give a more accurate measurement of the threat these agents pose to public health (Keer and Birch, 2003). Second, current data shows rRNA to be a better indicator of microbial viability in comparison to DNA (McKillip et al., 1998, 1999; Meijer et al., 2000; Villarino et al., 2000; Keer and Birch, 2003). Third, the greater abundance or rRNA per cell versus genomic DNA may by-pass the need for nucleic acid amplification, simplifying design of field sensors.

The assay developed uses DNA probe-coated magnetic beads in combination with the electrochemical monitoring of changes in the oxidation state of guanine nucleotides to selectively and directly detect microbial RNA (Fig. 1). As a proof-of-concept, a DNA probe was designed for specific capture and detection of bacterial 16S rRNA belonging to the family Enterobacteriacae (Loge et al., 1999). Several species of enterobacteria (coliforms), including E. coli, Enterobacter and Klebsiella species are used as indicators of fecal pollution (Simpson et al., 2002). The electrochemical RNA assay was evaluated using E. coli, which is used routinely to indicate fecal contamination of waters (EPA, 1998, 2000). The specificity of the probe for the family Enterobacteriacae was predicted by in silico analysis (Fig. 3); based upon conserved nucleotide sequences within 16S rRNA genes.

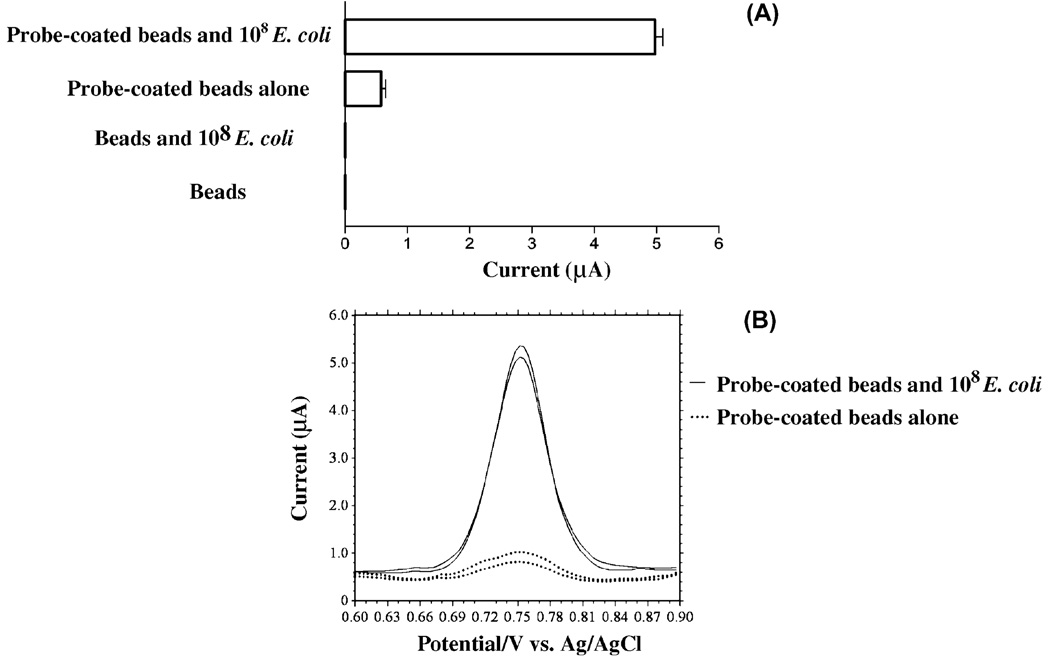

3.2. The electrochemical response is due to RNA specifically binding to DNA probes

DNA probes hybridized to synthetic oligonucleotides can be detected electrochemically based upon the oxidation of guanine bases (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002). The data in Fig. 4 showed for the first time that electrochemical oxidation of guanine bases can be used to detect bacterial rRNA molecules (E. coli) hybridized to DNA probes. Electroanalysis of samples containing DNA probe-coated beads in the absence of RNA resulted in a low, but measurable current (<1 µA) since the nucleotide sequence of ENTI-2a-R contains guanine nucleotides (Fig. 4). The absence of current peaks for samples containing E. coli RNA plus beads lacking DNA probes indicated that bacterial RNA is forming specific base pairings with complementary DNA probe sequences (Fig. 4) rather than nonspecifically binding to magnetic beads. The observation of symmetrical current peaks with a peak potential of +0.75 V (Fig. 4B) is consistent with the oxidation of guanine bases (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002).

Fig. 4.

The voltammetric response is due to binding of RNA to DNA probe-coated beads and subsequent oxidation of guanine bases. (A) The current response resulting from the oxidation of guanine bases is observed only upon exposing DNA probe-coated magnetic beads to isolated RNA (probe-coated beads and 108 E. coli). Due to the presence of guanine bases within the nucleotide sequence of ENTI-2a-R (bar labeled probe-coated beads alone), samples containing DNA probe-coated beads in the absence of RNA results in a measurable current (<1 µA). Isolated E. coli RNA does not non-specifically bind magnetic beads not conjugated to DNA probes (beads and 108 E. coli). (B) Voltammograms of data in panel (A) showing the selective oxidation of guanine bases, as defined by the observation of voltammetric peaks at about +0.75 V. The mean current peak heights of samples from two independent experiments are shown in panel (A).

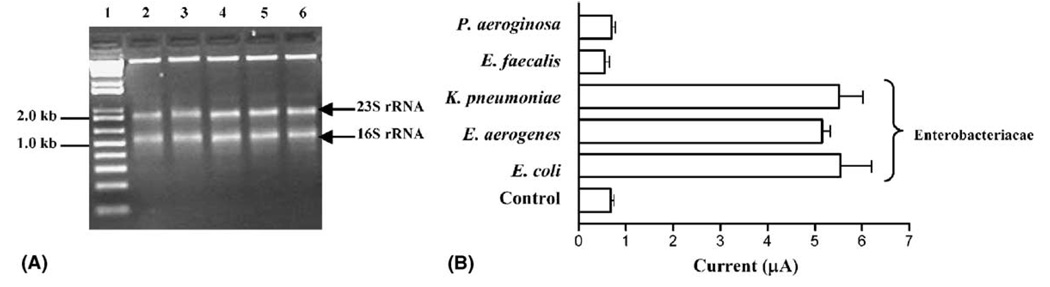

3.3. Assay specificity

Selective hybridization of target nucleic acids is a requisite for biologically-relevant assays (Ross, 1999). Hence, the ENTI-2a-R probe, was tested for its ability to selectively bind RNA isolated from other members of the family Enterobacteracae in addition to E. coli. Selective hybridization of enterobacteria RNA (E. coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Klebsiella pneumoniae) was observed upon using RNA isolated from 108 CFU per hybridization reaction as the DNA probe target (Fig. 5A). In all cases, inclusion of enterobacterial RNA in the reaction mixture resulted in current peak heights about six times greater than corresponding negative controls. The non-enterobacteria tested, Enterococcus faecalis and P. aeroginosa, were negative in identical and parallel reactions. In these cases, using RNA from 108 CFU per reaction as the hybridization target produced current peak heights (<1.0 µA) similar to those observed for the negative controls (Fig. 5A). The observed specificity of ENTI-2a-R was consistent with our in silico predictions (Fig. 3). The isolation of total RNA from 108 CFU of each bacterial species yielded similar amounts of 16S rRNA molecules available for DNA probe binding (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Specificity of the electrochemical RNA detection assay. (A) A 1.0% agarose gel loaded with total RNA isolated from 108 CFU of E. coli (lane 2), Enterococcus faecalis (lane 3), Klebsiella pneumoniae (lane 4), Enterobacter aerogenes (lane 5), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (lane 6). Lane 1 contains a molecular weight standard. The arrows (←) show the positions of 16S and 23S rRNA transcripts. (B) The ENTI-2a-R DNA probe selectively hybridizes RNA isolated from bacterial species belonging to the family Enterobacteriacae. For each species, RNA isolated from 108 CFU was included per hybridization reaction. The current peak height values plotted are the mean of samples from two independent experiments, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. The control reactions consisted of DNA probe-coated magnetic beads in the absence of bacterial RNA.

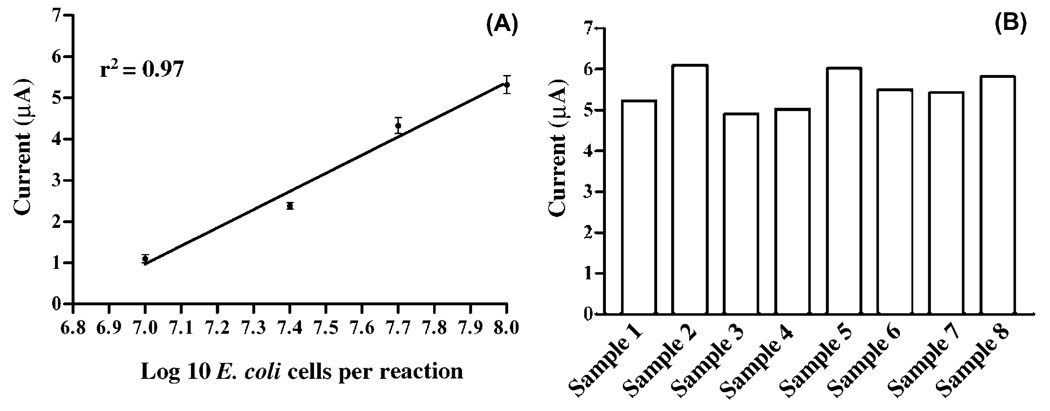

3.4. Current peak height is reproducible and is proportional to RNA target concentration

The consistency of molecular-based detection schemes is an important factor in evaluating novel assays. The reproducibility of the electrochemical RNA assay in detecting RNA isolated from 108 CFU of E. coli was examined. Electroanalysis of 8 identical samples yielded reproducible current peak heights with a relative standard deviation of less than 10.0% (Fig. 6B). Such precision compares favorably with values reported for similar electrochemical methods (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002). The resulting relative standard deviation of the assay reflects the reproducibility of the hybridization and electrical detection steps.

Fig. 6.

Current signal peak height is proportional to the concentration of E. coli. (A) The voltammetric response is proportional to the amount of target RNA provided per 50 µL hybridization reaction. A series of dilutions of E. coli RNA, varying from the amount isolated from 107 to 108 CFU were used as targets in the standard assay (Section 2.8). For clarity, total RNA was isolated from enumerated E. coli cultures as described in Section 2.7. The mean current peak heights of samples from two independent experiments are shown. (B) Reproducibility of detecting E. coli RNA via the electrochemical assay. The current peak heights of 8 independent reactions, each containing total RNA isolated from 108 CFU, are depicted.

The electrochemical RNA assay was further characterized by examining the sensitivity of the procedure. Current peak heights were proportional to the amount of RNA provided per 50 µL hybridization reaction. Fig. 6A shows a logarithmic plot of current peak height versus E. coli RNA concentration (labeled as the equivalent number of E. coli CFU), which displayed a linear range of quantification (correlation coefficient, r2 = 0.97). Electroanalysis of total RNA isolated from 107 CFU of E. coli resulted in current peak heights 2 times greater than corresponding negative control reactions (average peak height of ~0.5 µA), and thus was considered the limit of detection for the assay (Fig. 6B).

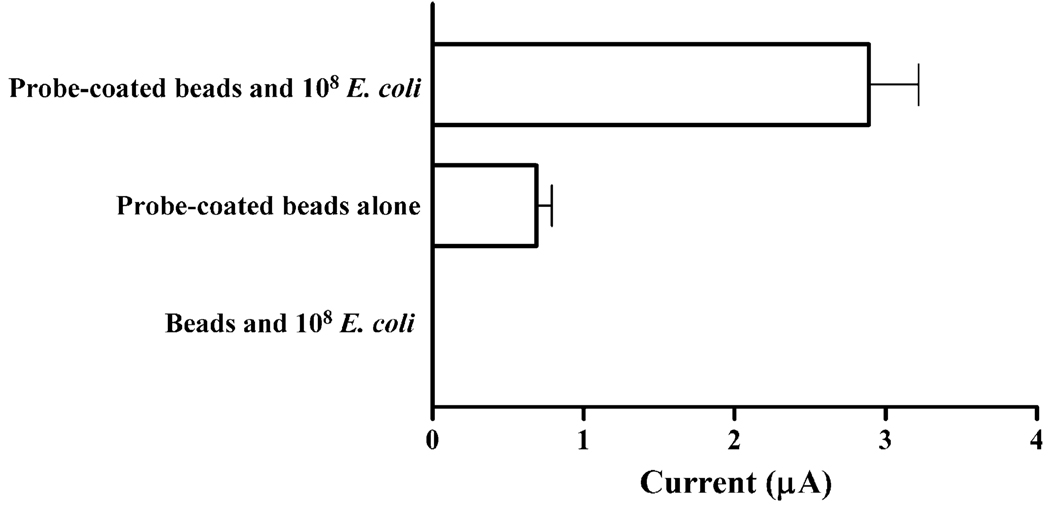

3.5. E. coli RNA can be detected directly from lysed cells via electrochemistry

The integration of nucleic acid hybridization assays into remote biosensors requires automated methods for the isolation of nucleic acids (Straub and Chandler, 2003). To simplify the challenge of remote isolation of nucleic acids, we explored the use of reagents that provide all the chemicals needed for cell lysis and selective nucleic acid hybridizations in one reaction. Reagents that meet these criteria often contain chaotropic-salts, which are particularly useful in DNA/RNA hybridization assays as they simultaneously lyse cells, inhibit nucleases, and provide adequate hybridization stringency (Van Ness and Chen, 1991). Hence, cell lysates prepared in chaotropic-salt containing buffers can be used directly in DNA probe assays (Van Ness and Chen, 1991; Scholin et al., 1996). The chaotroic-salt based lysis/hybridization buffer used in this study (Sections 2.8 and 2.9) was slightly modified from a reagent previously integrated into an automated, marine biosensing platform for the detection of rRNA from harmful algae (Scholin et al., 1996, 1999, in press). The data presented in Fig. 7 show that our electrochemical method can be used to selectively detect nucleic acid hybridizations directly from microbial (E. coli) cell extracts. The mean current peak height for detection of 16S rRNA from 108 lysed cells is less (3 µA, Fig. 7) than the mean current peak height for detection of 16S rRNA from total RNA isolated from 108 E. coli (5 µA, Fig. 4). The reason for the discrepancy is unclear, but may be due to differences in the methods used to obtain RNA.

Fig. 7.

Electrochemical detection of E. coli RNA directly from cell lysates. Approximately 108 CFU of lysed E. coli were used in each 50 µL hybridization reaction. The mean current peak heights and standard deviation of samples from two independent experiments are shown. The current response resulting from the oxidation of guanine bases is observed only upon exposing DNA probe-coated magnetic beads to cell lysates containing RNA (probe-coated beads and 108 E. coli). Due to the presence of guanine bases within the nucleotide sequence of ENTI-2a-R (bar labeled probecoated beads alone), samples containing DNA probe-coated beads in the absence of RNA results in a low, but measurable current (<1 µA). RNAcontaining E. coli lysates do not non-specifically bind magnetic beads not conjugated to DNA probes (beads and 108 E. coli).

4. Discussion

4.1. Assay performance

This study was designed to explore the potential of using electrochemical, nucleic acid hybridization assays for detecting aquatic microbes as a first step toward providing field-deployable instruments, including automated, in situ biosensors. Wang (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002) previously reported a novel strategy for sensitive electrical DNA sensing based upon tracking the oxidation of guanine nucleotides. Therefore, we hypothesized that the use of DNA probe-coated magnetic beads in combination with electrochemical monitoring of changes in the oxidation state of guanine nucleotides would allow for selective and direct detection of microbial nucleic acids. The results here demonstrate the feasibility of this concept by the detection of RNA from the fecal indicator E. coli. Ribosomal RNA was selected as the hybridization target due to its high cellular abundance and use as a cell viability marker (Keer and Birch, 2003).

Molecular techniques are a promising means for improving fecal indicator monitoring (Kroger et al., 2002; Straub and Chandler, 2003). Unfortunately, molecular detection techniques often (e.g. PCR) require a enzymatic amplification of nucleic acids, which may not be ideally suited for environmental monitoring since they require complex and expensive instruments, are not always quantitative, and are prone to errors by inhibition of the amplification reaction (Reischl and Kochanowski, 1995; Orlando et al., 1998; Lantz et al., 2000; Loge et al., 2002). The development of molecular assays capable of detecting microbial DNA and RNA directly, without any amplification steps, is challenging. Recent studies have made progress in this area by using the principles of analytical electrochemistry. For instance, a method published by Gabig-Ciminska in 2004 detected 1010 molecules of isolated E. coli RNA per reaction by electrochemical monitoring of alkaline phosphatase substrates at gold electrodes (Gabig-Ciminska et al., 2004b). Since actively growing E. coli contain ~104 16S rRNA molecules per cell, 1010 molecules is equivalent to the amount of 16S rRNA isolated from 106 cells (Neidhart et al., 1990). Although the sensitivity of our assay is similar (107 E. coli cells, Fig. 6A), it has a practical advantage over the alkaline phosphatase method. In contrast to the alkaline phosphatase technique, which uses gold electrodes that are expensive and require electrochemical expertise for fabrication, the assay presented here is readily accessible to non-electrochemists as it uses inexpensive pencil electrodes that are easy to make (Section 2.3 and Fig. 2).

As mentioned, electroanalysis of DNA probe-coated beads alone resulted in measurable currents, due to the presence of guanine nucleotides within ENTI-2a-R probe (Fig. 4). Further lowering of the detection limit is anticipated by longer hybridization times and substituting the guanines of ENTI-2a-R with inosine nucleotides, thereby eliminating current peaks contributed by DNA probes alone (Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Kawde, 2002).

The method presented has potential for the monitoring of dynamic marine environments for the presence of fecal pollution since it is rapid (4 h using isolated RNA), reproducible (Fig. 6B) and displays specificity (Fig. 5) for bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriacae, which includes fecal indicators routinely used in water quality monitoring programs and management standards (Simpson et al., 2002). In addition, because the US EPA methods for determining fecal pollution in a given body of water call for enumeration of bacterial indicators (EPA, 1998, 2000), the quantitative character (Fig. 6A) of this method further highlights the potential of this and other electrochemical assays as water quality monitoring tools. Moreover, the assay uses RNA as the hybridization target, which can be a better indicator of microbial viability relative to DNA (Keer and Birch, 2003). An added, practical feature of this method is that it can be rapidly modified to detect other relevant aquatic microbes, e.g. human pathogens and invasion species, since it requires only a single DNA probe for detection. Although the assay is being developed for field applications, the cost of running the assay in a laboratory is similar to standard microbial techniques due to the benefits of saving time and use of inexpensive materials. More specifically, the assay takes only hours (as opposed to days for culture-based techniques) to complete and uses inexpensive reagents, e.g. a standard mechanical pencil (Fig. 2) for analysis.

4.2. The electrochemical assay: applications to on-site and in situ, aquatic biosensing

Electrochemical biosensors have recently received much attention for the detection of microbial nucleic acids. Electrochemical DNA/RNA biosensors translate nucleic acid recognition events, specifically the formation of nucleotide-to-nucleotide base pairings, into useful electrical signals (Wang, 2000, 2002). The high sensitivity of these biosensors, together with their compatibility with automation technology, low cost, and independence of sample turbidity or optical pathway make them promising avenues for the development of portable, automated microbial detection instruments.

In keeping consistent with our long-term goals, the current assay was designed to have the potential to be integrated into automated biosensing platforms. As suggested below, we took advantage of several methods and strategies that should simplify the transfer of electrochemical assays from the laboratory bench to fielddeployable instruments, including automated, in situ biosensors. First, the detection of RNA was achieved by a rapid and sensitive electrochemical method, differential pulse voltammetry (Wang, 2000). Second, magnetic microspheres were used as a solid support for DNA probes. DNA-coated magnetic beads have potential to be of use in the biosensing field. Magnetic beads provide a large surface area for oligonucleotide attachment and allows for effective removal of non-target nucleic acids; as non-specific binding of such molecules often hampers biosensing of nucleic acids (Wang, 2000, 2002). Second, we made use of biomagnetic processing technology (MCB 1200 Biomagnetic Processing Platform, Section 2.3), which effectively combines efficient magnetic mixing and separation into a single, automatable procedure. Third, the RNA assay takes advantage of an electrochemical device that is small, inexpensive, and has proven itself useful in automated sensing applications, e.g., remote detection of explosives (TNT) in marine environments (Wang and Thongngamdee, 2003). Fourth, the method makes use of pencil graphite electrodes, which have been shown to possess features conducive to the development of electrical biosensors including low cost, favorable signal-to-background characteristics, and readily renewable surfaces (Wang and Kawde, 2002). Lastly, the assay described here uses a buffer that lyses cells, provides adequate nucleic hybridization stringency, and appears to be compatible with downstream electrochemical detection methods (Fig. 7). This finding is consistent with a recent study that showed direct electrochemical detection of 107 lysed Bacillus cereus cells (Gabig-Ciminska et al., 2004a). The use of this, and related reagents that allow the selective detection of nucleic acids directly from cell extracts, may eliminate a need to isolate nucleic acids prior to electrochemical detection, thereby streamlining the design of automated biosensors.

4.3. Future work

A new label-free method for the detection of RNA from coliform bacteria, including the fecal pollution indicator, E. coli, was developed to demonstrate the concept that electrochemical, nucleic acid hybridization assays can be used to detect and quantify aquatic microbes. The assay development process described in our study is the first step toward a long-term goal of capitalizing on biotechnology advances to develop field-deployable instruments, including automated, in situ biosensors for remote monitoring of aquatic environments.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Lin Lin of New Mexico State University for her participation in training Dr. Michael LaGier in the basics of analytical electrochemistry. Financial support from the National Science Foundation (Grant no. OCE-332918) as part of the National Oceans Partnership Program (NOPP) is gratefully acknowledged. This research was supported in part by an NIEHS Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences Center Grant (ES 05705) to the University of Miami. This research was carried out in part under the auspices of the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS), a joint institute of the University of Miami and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, cooperative agreement #NA17RJ1226.

References

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. fourth ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm AB, Grant SB, Kim JH, Mowbray SL, McGee CD, Clark CD, Foley DM, Wellman DE. Decadal and shorter period variability of surf zone water quality at Huntington Beach, California. Environmental Science and Technology. 2002;36:3885–3892. doi: 10.1021/es020524u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli VJ, Dufour AP, McCabe LJ, Levin MA. Swimming-associated gastroenteritis and water quality. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;115:606–616. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli VJ, Dufour AP, Levin MA, McCabe LJ, Haberman PW. Relationship of microbial indicators to health effects at marine bathing beaches. American Journal of Public Health. 1979;69:690–696. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.7.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond TG, Hill MG, Barton JK. Electrochemical DNA sensors. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21:1192–1199. doi: 10.1038/nbt873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour AP. Bacterial indicators of recreational water quality. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1984;75:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Bacterial water quality standard for recreational waters (freshwater and marine waters) United States Environmental Protection Agency; 1998. EPA-823-R-98-003. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Improved enumeration methods for recreational water quality indicators: Enterococci and Escherichia coli. United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2000. EPA-821-R-97-004. [Google Scholar]

- EST. Environmental Science and Technology. Vol. 38. 2004. Rapid indicators of beach pollution needed; pp. 283A–284A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabig-Ciminska M, Andresen H, Albers J, Hintsche R, Enfors SO. Identification of pathogenic microbial cells and spores by electrochemical detection on a biochip. Microbial Cell Factories. 2004a;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabig-Ciminska M, Holmgren A, Andresen H, Bundvig Barken K, Wumpelmann M, Albers J, Hintsche R, Breitenstein A, Neubauer P, Los M, Czyz A, Wegrzyn G, Silfversparre G, Jurgen B, Schweder T, Enfors SO. Electric chips for rapid detection and quantification of nucleic acids. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2004b;19:537–546. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(03)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow HB, Burkholder JM, Reed RE, Lewitus AJ, Kleinman JE. Real-time remote monitoring of water quality: a review of current applications, and advancements in sensor, telemetry, and computing technologies. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2004;300:409–448. [Google Scholar]

- Kay D, Fleisher JM, Salmon RL, Jones F, Wyer MD, Godfree AF, Zelenauch-Jacquotte Z, Shore R. Predicting likelihood of gastroenteritis from sea bathing: results from randomised exposure. Lancet. 1994;344:905–909. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keer JT, Birch L. Molecular methods for the assessment of bacterial viability. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2003;53:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerman K, Kobayashi M, Tamiya E. Recent trends in electrochemical DNA biosensor technology. Measurement Science and Technology. 2004;15:R1–R11. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger S, Piletsky S, Turner AP. Biosensors for marine pollution research, monitoring and control. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2002;45:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(01)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PG, Abu al-Soud W, Knutsson R, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Radstrom P. Biotechnical use of polymerase chain reaction for microbiological analysis of biological samples. Biotechnolology Annual Reviews. 2000;5:87–130. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(00)05033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc H, Schwartzbrod L, Dei-Cas E. Microbial agents associated with waterborne diseases. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2002;28:371–409. doi: 10.1080/1040-840291046768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leecaster MK, Weisberg SB. Effect of sampling frequency on shoreline microbiology assessments. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2001;42:1150–1154. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge FJ, Emerick RW, Thompson DE. Development of a fluorescent 16S rRNA oligonucleotide probe specific to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Water Environment Research. 1999;71:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Loge FJ, Thompson DE, Call DR. PCR detection of specific pathogens in water: a risk-based analysis. Environmental Science and Technology. 2002;36:2754–2759. doi: 10.1021/es015777m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillip JL, Jaykus LA, Drake M. rRNA stability in heatkilled and UV-irradiated enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli O157:H7. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64:4264–4268. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4264-4268.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillip JL, Jaykus LA, Drake M. Nucleic acid persistence in heat-killed Escherichia coli 0157:H7 from contaminated skim milk. Journal of Food Protection. 1999;62:839–844. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.8.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A, Roholl PJ, Gielis-Proper SK, Meulenberg YF, Ossewaarde JM. Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro and in vivo: a critical evaluation of in situ detection methods. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2000;53:904–910. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.12.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhart FC, Ingraham JI, Schaechter M. A Molecular Approach. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1990. Physiology of the Bacterial Cell. [Google Scholar]

- Ng JH, Hag LL. Biochips beyond DNA: technologies and applications. Biotechnology Annual Reviews. 2003;9:1–149. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(03)09001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando C, Pinzani P, Pazzagli M. Developments in quantitative PCR. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 1998;36:255–269. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1998.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. Nucleic Acid Hybridization: Essential Techniques Series. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reischl U, Kochanowski B. Quantitative PCR. A survey of the present technology. Molecular Biotechnology. 1995;3:55–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02821335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholin CA. Monographs on Oceanographic Methodology, UNESCO reports in Marine Science. Paris: UNESCO; Prospects for developing automated systems for in situ detection of harmful algae and their toxins. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Scholin CA, Buck KR, Britschgi T, Cangelosi G, Chavez FP. Identification of Pseudo-nitzschia australis (Bacillariophyceae) using rRNA-targeted probes in whole cell and sandwich hybridization formats. Phycologia. 1996;35:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Scholin CA, Marin R, Miller P, Doucette G, Powell C, Howard J, Haydock P, Ray J. Application of DNA probes and a receptor binding assay for detection of Pseudonitzschia (Bacillariophyceae) species and domoic acid activity in cultured and natural samples. Journal of Phycology. 1999;35:1356–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JM, Santo Domingo JW, Reasoner DJ. Microbial source tracking: state of the science. Environmental Science and Technology. 2002;36:5279–5288. doi: 10.1021/es026000b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohail M, Akhtar S, Southern EM. The folding of large RNAs studied by hybridization to arrays of complementary oligonucleotides. RNA. 1999;5:646–655. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub TM, Chandler DP. Towards a unified system for detecting waterborne pathogens. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2003;53:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL. Microbiology, An Introduction. 7th ed. New York: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness J, Chen L. The use of oligonucleotide probes in chaotrope-based hybridization solutions. Nucleic Acids Research. 1991;19:5143–5151. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarino A, Bouvet OM, Regnault B, Martin-Delautre S, Grimont PAD. Exploring the frontier between life and death in Escherichia coli: evaluation of different viability markers in live and heat- or UV-killed cells. Research in Microbiology. 2000;151:755–768. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)01141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Analytical Electrochemistry. second ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Electrochemical nucleic acid biosensors. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2002;469:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kawde AN. Amplified label-free electrical detection of DNA hybridization. The Analyst. 2002;127:383–386. doi: 10.1039/b110821m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Thongngamdee S. On-line electrochemical monitoring of (TNT) 2,4, 6-trinitrotoluene in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2003;485:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kawde AN, Sahlin E. Renewable pencil electrodes for highly sensitive potentiometric measurements of DNA and RNA. The Analyst. 2000;125:5–7. doi: 10.1039/a907364g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]