Abstract

Ten years of participant-observation fieldwork and photography among a multi-ethnic social network of homeless heroin injectors and crack smokers in California reveal hierarchical interpersonal relations between African Americans, whites and Latinos despite the fact that they all share a physical addiction to heroin and live in indigent poverty in the same encampments. Focusing on tensions between blacks and whites, we develop the concept of ‘ethnicized habitus’ to understand how divisions drawn on the basis of skin color are enforced through everyday interaction to produce ‘intimate apartheid’ in the context of physical proximity and shared destitution. Specifically, we examine how two components of ethnic habitus are generated. One is a simple technique of the body, a preference for intravenous versus intramuscular or subcutaneous heroin injection. The second revolves around income-generation strategies and is more obviously related to external power constraints. Both these components fit into a larger constellation of ethnic distinction rooted in historically entrenched political, economic and ideological forces. An understanding of the generative forces of the ethnic dimensions of habitus allows us to recognize how macro-power relations produce intimate desires and ways of being that become inscribed on individual bodies and routinized in behavior. These distinctions are, for the most part, interpreted as natural attributes of genetics and culture by many people in the United States, justifying a racialized moral hierarchy.

Keywords: United States, urban poverty, crack, substance abuse, injection drug use

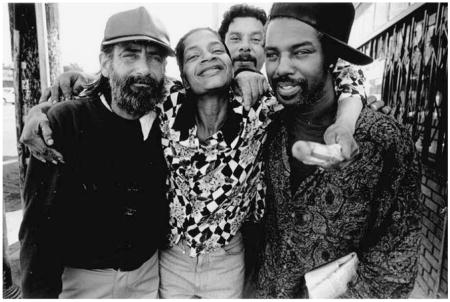

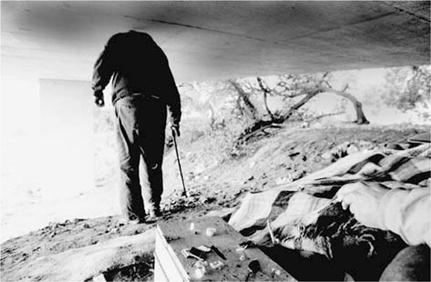

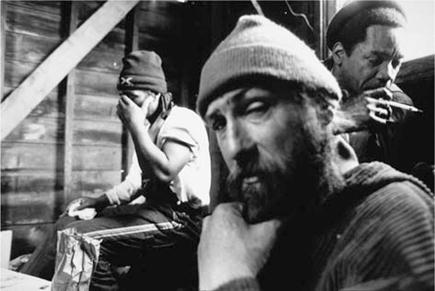

At first sight, street corners where homeless heroin addicts congregate in San Francisco look like a whirlwind of multicultural diversity. Indeed, one might think that physical and psychological addiction to the point of indigence would reduce humans to some sort of common – if not solidary – essence. The decade that we have spent conducting participant-observation research among a social network of approximately two dozen homeless heroin injectors who also smoke crack and drink alcohol, however, reveals deep divisions across ethnic lines that are interpreted racially. The group of homeless we have been studying is composed of African American, Latino, and white men and women in advanced middle age. They represent the demographic mainstream of street-based substance abusers in the United States. They came of age in the 1960s; became addicted to heroin in the 1970s; became chronic cocaine users in the 1980s and then crack smokers in the 1990s (Golub and Johnson, 2001). In San Francisco this ethnically diverse aging street-based population commingles intensely across ethnic lines, simultaneously sharing and competing for the same limited resources – especially public space, income and drugs.

Sociologists and anthropologists critiquing the structure of racism in the urban United States have coined phrases such as ‘de facto inner-city apartheid’ (Bourgois, 2003) and ‘hyperghetto’ (Wacquant, 2002) to convey the extent of the phenomenon of segregation by skin color – primarily black versus white, but also brown. Homeless drug injectors in San Francisco, however, are not confined to segregated neighborhoods. On the contrary, they usually operate in heavily transited multi-ethnic business thoroughfares or empty urban de-industrialized wastelands near railroad tracks, warehouses and highway intersections. We have been observing dramatic distinctions, however, across ethnic lines in their behaviors. Their interpersonal relations, especially those between African Americans and whites, are generally hostile and sometimes violent. They refer to each other routinely, for example, with racist epithets and derogatory dictums. We have developed the term ‘intimate apartheid’ to convey how an overwhelmingly coercive form of historically engrained segregation and conflict operates at the interpersonal level in the United States to re-cement racialized distinctions among homeless addicts who survive on the street side-by-side, physically and/or psychologically dependent on the same drugs. We draw on the concept of habitus (see review of concept by Wacquant, 2004) to understand the overwhelming and coercive nature of these divisions that manifest themselves in the purposeful demarcations the homeless draw between the racialized categories ‘black’ and ‘white’ (and to a lesser extent ‘Latino’) within their encampments. Understanding these divisions as expressions of habitus links social structural power relations to intimate ways of being at the level of individual interactions to show how everyday practices and preconscious patterns of thought generate and reproduce social inequality.

Techniques of the body

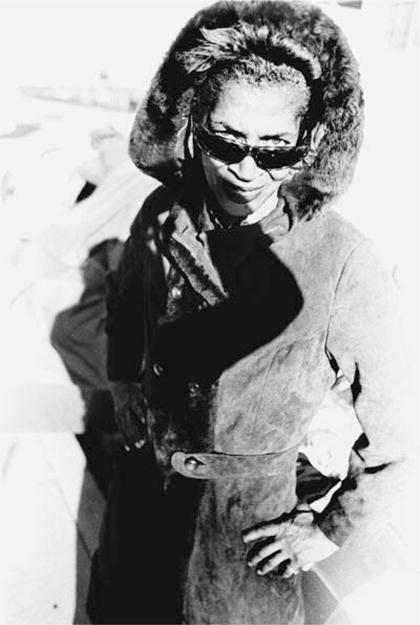

The centrality of racism to symbolic domination in the United States suggests that the ethnic dimensions of habitus should be significant in that country. Indeed, it is surprising that the relationship between habitus and ethnicity has not been explicitly analyzed in the United States. The ‘ethnicized’ dimensions of habitus that we have been observing ethnographically manifest themselves as distinct body postures, scarring patterns, disease infection rates, clothing style preferences, bathing practices, smell management, poly-drug consumption choices, mechanisms of drug administration, relationships to sexuality, income-generating strategies, family structures, and tenors of interpersonal relations. To explore this phenomenon we have chosen only two specific examples of ethnic components of habitus to explicate in detail with respect to the African American and the white members of our social network of homeless injectors. The first is based on Marcel Mauss’s concept of techniques of the body (Mauss, 1936), referring to ways of walking and dressing as well as to pre-conscious ways of holding the body. These forms of embodiment carry symbolic power implications that tend to be naturalized as characterological or racial/cultural deficiencies or superiorities (Bourdieu, 2000).

The homeless in our scene notice the visible distinctions in caring for and carrying the body across ethnic groups and they refer to them in racist language such as: ‘niggers like that crack’ or, vice versa, ‘whites smell bad.’

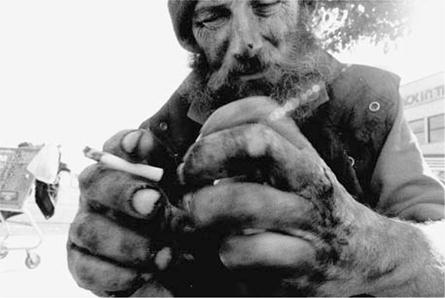

The specific bodily technique we are examining in this article at first sight appears neutral, even banal: it is the apparently trivial detail of the mechanism of drug administration. Both the African Americans and the whites prefer intravenous injection of heroin because of the initial rush of pleasure provided by a direct deposit of the drug into the vein. The veins of both the African Americans and the whites, however, are scarred from lifetime careers of daily multiple injections of heroin. The whites claim that this scarring makes it virtually impossible for them to locate a vein in which to inject their heroin. Usually they hastily administer their injections into body fat or muscle tissue, sometimes directly through their clothes, rendering them especially vulnerable to contracting abscesses (Ciccarone et al., 2000).

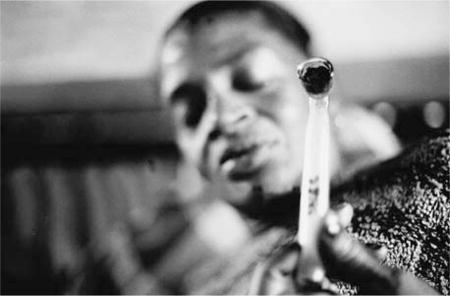

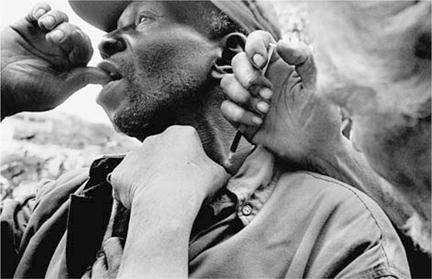

In contrast, the elderly African American homeless heroin addicts in our social network usually manage to find a vein. It sometimes takes them 40 minutes, or even longer, to administer their injections. They painstakingly search for them, repeatedly probing with their needles, sometimes seeking dangerous or painful parts of the body, such as the jugular or between the toes. At the end of their injection sessions they often have blood dripping from their multiple puncture sites. Their used syringes carry visible traces of blood, rendering them more vulnerable to the spread of blood-borne diseases such as HIV (Bourgois et al., 1997).

Income-generating strategies

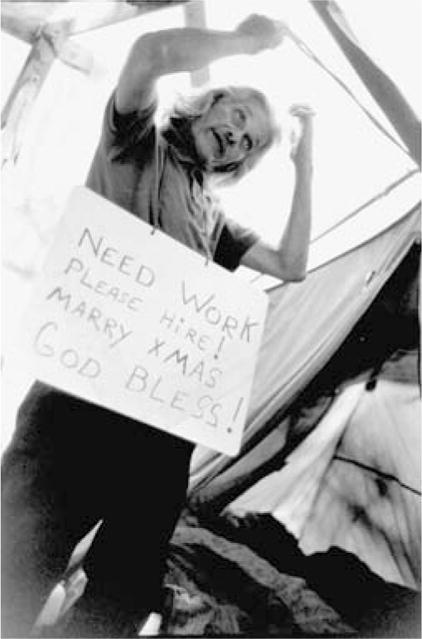

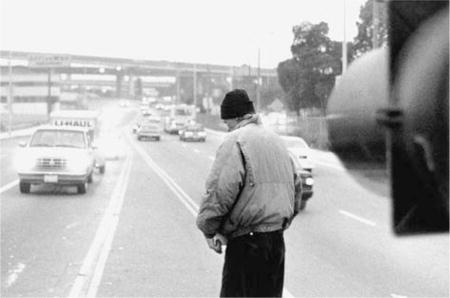

The second component of habitus we have chosen to analyze in detail here is more evidently related to material power relations and the economic field: the whites and the African Americans rely on distinct combinations of income-generating strategies. In summary, the whites earn the bulk of their income from passive begging by ‘flying signs’ along highway access ramps to elicit contributions of small change from commuters: ‘Please help, God Bless, Vietnam Vet, Will work for food.’

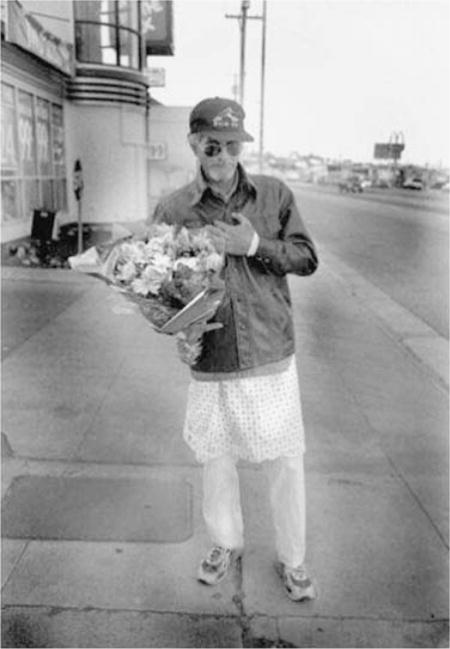

Dejected, their eyes on the ground, dressed in rags, with visible scars and scabs, the whites elicit pity and/or disgust precipitating gifts of spare change.

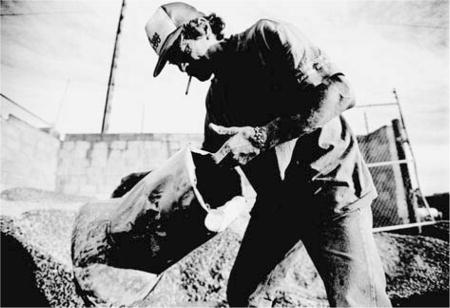

The whites also often work part-time as off-the-books, just-in-time laborers for small business owners in the neighborhood, who are usually Arab, Latino, or whites of European descent.

Usually they are hired for only a few hours per day on discrete manual labor tasks, such as sweeping the sidewalk, unloading trucks, or stocking items in stores. They often receive below minimum wage. Many also obtain a proportion of their income from recycling cans and scavenging through garbage dumpsters. Most of them further supplement their funds through opportunistic theft from backyards, warehouses and unlocked cars.

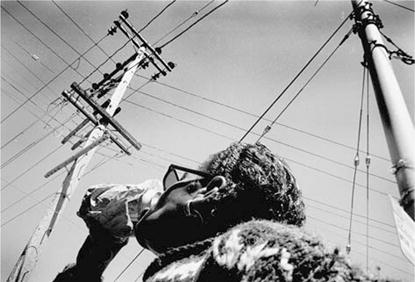

In contrast, the African Americans in our network rarely fly signs or beg passively. When they do panhandle, it is usually accompanied by both visual and verbal contact. They tend to offer a service, such as washing a windshield at a gas station. Rather than attempting to evoke pity from passersby through a passive demeanor, they are more likely to humor, cajole or even threaten potential contributors, sometimes demanding money. Most importantly, a larger proportion of their income is generated by burglary, especially from construction sites, warehouses and car trunks.

The African Americans also tend to professionalize and specialize in what they steal. For example, they stake out their sites in advance, and sometimes even dress in the disguise of maintenance workers or delivery personnel to access private property unobtrusively. They develop long-term relationships with professional fences, who purchase their products, and private businesses that commission them to steal items. They often also recycle and scavenge through the garbage, as do the whites. Carrying stolen items in a shopping cart full of recyclable tin cans and filthy bric-a-brac is an effective way to camouflage the transport of valuable stolen items.

The African Americans are rarely employed as day laborers by local businesses. In fact, they criticize the relationships that the whites develop with employers as being akin to slavery. They consider just-in-time, odd-job, and off-the-books working conditions to be demeaning, exploitative and feminizing. Indeed, the white addicts are often forced to grovel obsequiously in front of their bosses in order to obtain a few hours of legal work. The whites strive to persuade the small business owners who hire them that they are that particular employer’s chosen, worthy homeless person. They demonstrate appreciation for the favor of receiving below-minimum- wage payment and no benefits. Furthermore, many of the storekeepers and small business owners who hire the white heroin injectors manipulatively pay only the cost for the minimum dose of a morning dose of heroin to their favorite homeless person. This assures the employer that every morning this particular addict, driven by impending heroin withdrawal symptoms, will faithfully knock on the business door, asking, ‘Any work for me today, Boss?’

The generative forces of habitus

If we were to leave our ethnography of ethnically distinct practices at the level of description, the insights provided by the concept of habitus and by a focus on techniques of the body would not go much beyond the ethnography of a stereotype. A straightforward phenomenological description of the effects of habitus risks reifying stereotypes around culture. Indeed, the homeless heroin addicts themselves talk about their easily observable distinct injection practices and income-generating strategies in a moralized racist discourse: ‘niggers are thieves’ is countered by ‘whites are lame no-hustles who lack self-respect and initiative’. In order to open the black box of habitus and de-essentialize the existence of these patterns in everyday interactions at the level of individuals, we need to look at the generative forces of habitus formation. To denaturalize the practices and the forms of embodiment that are associated visibly with ethnicity, we need to relate habitus to the structures of symbolic power that give it meaning.

It is easy to identify the significant generative dimensions of the distinct ethnic income-generating strategies that we have described. Arguably, slavery is an identifiable sediment from history within the habitus of many African Americans in the United States. The ongoing structural effects of slavery on regional location and on class positioning in contemporary society are of course extremely complex. The effects of slavery have been mediated over many generations of upward – and sometimes downward – mobility as well as by identifiable patterns of rural-urban migration, but they continue to impinge actively on the lives of the descendants of slaves. More importantly, different forms of institutionalized racism – indentured sharecropping under Jim Crow, ghettoized industrial labor, massive incarceration and the hyperghetto – have replaced, supplanted, reinforced, and contradicted the ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery under democracy and industrial capitalism that was a unique characteristic of the United States and helps explain the virulence of its contemporary form of racism (see analysis by Wacquant, 2005). The memory of slavery retains immense symbolic importance in the United States. The institution is evoked in intimate, painful ways in everyday parlance, spawning emotions among both whites and blacks. For example, a front-page New York Times article on the new technology of genetic testing featured the satisfaction of an African American woman with ‘light skin’ who wanted to prove to her friends that ‘more white is showing in the color, but underneath, I’m deepest Africa’, in order to counter their derogatory insinuations that her ‘high yellow’ skin color was evidence of ‘… the legacy of a slave owner who … “went down to that cabin and had what he wanted” with her great-great-great grandmother’ (Harmon, 2005).

Concretely, the memory of slavery as a sediment from history manifests itself in the ways that unemployed African American drug users on the street experience humiliation around the kind of subordinated patron-client relationships that business owners impose on day laborers. The white homeless do not resonate with the same sense of outrage and insult at the hands of their often abusive part-time employers. The African Americans are acutely attuned to any explicit or even inadvertent racist expressions by business owners. Their explicit resistance to exploitation, racism and humiliation is also rooted in the historical migration experience of African Americans to San Francisco. All the African Americans in our sample (and the majority of middle-aged African Americans in San Francisco) are the first generation born from rural immigrants from east Texas and Louisiana, a region with some of the Deep South’s highest rates of per capita lynching in the 1910s and 1920s (Beck and Tolnay, 1990; Broussard, 1993). They were fleeing violent racism, plantation labor, or sharecropping debt peonage and came to work in San Francisco during the Second World War. All the parents of the African Americans in our sample and some of the injectors in their youth worked in unionized industrial jobs in shipyards, on docks, or in steel factories. The industrial unionized economy, however, has been largely wiped out in the US. Even though these jobs have disappeared with the restructuring of the global economy, a memory and consciousness of unionized resistance to exploitation remains in the second generation, and they find it especially noxious to have to re-enter a subordinated labor relationship in the early 21st century.

Many of the whites are also second generation descendants of rural immigrants from impoverished backgrounds, but, unlike the African Americans, they have no salient living memory of that migration and they do not retain relationships to their parents’ and grandparents’ home communities. Most importantly, the parents of the white injectors tended to have been precarious members of the entrepreneurial petty bourgeoisie (bar owners, sign painters, foundry contractors), or lumpen themselves (beatnik poets). Many of the whites worked for their fathers as children. With respect to class, both the African Americans and the whites have been downwardly mobile and technically lumpenized, but they have very different relationships to conceptions of exploitation and distinct tolerances for subordination within humiliating patron-client employment relationships. In other words, the legacy of slavery and the destruction of the unionized industrial labor market, exacerbated by the ongoing active experience of racism in the United States, helps explain why blacks refuse demeaning jobs and submissive relationships with patrons.

De facto workplace apartheid and intimate practices

The African Americans do occasionally obtain casual, off-the-books day labor jobs like the whites and Latinos. When this occurs, the aforementioned sediments from history and contemporary political economy express themselves in individual everyday practices of resistance to exploitation and racist disrespect. Of course, in everyday interaction at the work site this is not understood to be a structural inheritance of historical as well as contemporary racist power relations or political economic forces. On the contrary, African American oppositionality at work is usually interpreted in moral terms as either a character flaw or as an essentialized cultural/genetic trait. An example from our fieldwork notes illustrates how structural power dimensions are misrecognized in th e logic of practice by all the actors – both those who benefit and those who suffer:

Jeff’s fieldnotes from December 1998

I start taking photos of Carter stacking Christmas trees in the back of the lot. He is the only African American in the homeless scene to have been hired at the lot. I think it must have something to do with the upturn in the dotcom economy of the Bay Area. He calls out to his fellow workers – none of whom are African American – in the front of the lot to come back and pose for a group portrait. They ignore him. He calls out several more times, practically pleading for them to come.

A bit embarrassed for him, I continue taking pictures and then walk to the front of the lot where Felix, one of the Latino homeless men who often shares heroin and crack with Carter, whispers to me, ‘The boss fired Carter yesterday.’ Felix explains that Carter left on his lunchtime break and did not return until an hour before closing time at 6 pm, and tried to pretend he was merely returning from a 15 minute break. The boss caught him and fired him.

This morning Carter begged for his job back and the boss made him admit in front of all the other workers:

[Felix imitating Carter’s stammer when nervous] ‘I … I … guess … I guess I really took a five hour break yesterday.’

[Felix imitating the boss] ‘That’s more like it.’

The manager of the Christmas tree lot then agreed to rehire Carter, but only on condition of ‘work punishment.’ That is why he is alone in the back of the lot making stands for the trees. He is not allowed into the front of the lot where the workers interact with the customers and earn tips on sales.

As Felix is telling all this to me, the boss walks over to us, asking me if I want to buy a tree. When I explain I am just visiting Felix he responds, ‘Sorry, you gotta move on. I got to keep Felix working before I lose him.’

From everyone’s perspective – even Carter’s – there is a race-blind reason for why the only African American in our network who obtained a job at the Christmas tree lot should be relegated to work punishment in the back. He is objectively a lousy worker who does not obey orders with discipline. Carter is not easily exploitable. He also resists exploitation. This dynamic is illustrated by the conversation Philippe had with Carter only three hours after Jeff photographed him on work punishment standing in front of the corner liquor store across the street from the Christmas tree lot where Carter was taking yet another extended impromptu break from work. The conversation reveals the habituses of both the African American hustler and the white middle-class ethnographer. Philippe was excited by the fact that Carter was working legally and Philippe was eager to provide moral support to encourage Carter to continue working legally. Philippe was nervous about the possibility that Carter might quit his job. Consequently, he eagerly steered the conversation to the subject of earning tips, since he thought that the ability to earn tips in the legal economy most coincided with the sense of achievement that an outlaw experiences in the hustling economy and he wanted to valorize legal income generation. Ironically, Philippe did not realize at the time that Carter was on work punishment. He was puzzled by Carter’s distaste for his legal job. In turn, Carter masked his shame at not being allowed to interact with the public and earn tips by critiquing exploitation and celebrating masculine bravado, despite at the same time yearning for stable, decently remunerated employment:

Philippe: What’s up, Carter? You’re on break now?

Carter: Nah. I just took one ’cause I seen y’all from across the street.

Philippe: [Nervously] I’m gonna get you in trouble? You’ll have to go back to work soon.

Carter: Man, you know what? Just fuck ’em! What they gonna do, send me home? Fuck it. Pay me off and I’m going.

Philippe: Well, if you’re not going back, let’s at least walk around the corner so the boss doesn’t see you. I don’t want you to get fired.

[Walking to the back alley] The tips are good there? Aren’t you earning good money slinging trees?

Carter: Oh, they been OK … Uh … uh … uh, I mean, they been OK … Uh, they ain’t all that great either.

I mean, the law of averages and chances on shit I do out here [pointing down the alley]. On takin’ penitentiary chances … stealin’, I do better than I do over there [pointing in the direction of the Christmas tree lot].

It’s just that this Christmas tree work is steady and keepin’ me out of trouble. It’s uh… an hourly wage and I know that’s guaranteed money.

Philippe: But isn’t it kind of nice to have a steady income?

Carter: Yeah … [Imitating a whiter voice] yeah … yeah. [We laugh]

Philippe: But Carter, seriously, isn’t it a relief not to have to be hitting licks all the time? I mean, doesn’t stealing give you more anxiety?

Carter: [Long pause, and then thoughtfully] It gives me … a rush. A fuckin’ rush, Philippe. I mean, actually working over there [frowning in the direction of the Christmas tree lot], I be, in a way … bored. Unless, I run across a little fine ol’ chick buyin’ a tree, or this’n that. Otherwise I be bored.

Philippe: Explain to me the difference between working legally and hitting licks …

Carter: Taxes! [Laughs] Fuckin’ taxes. [Laughing heartily]

I don’t know. Shit! What the fuck you askin’ me for, Philippe? I’m the lowest man on the fuckin’ totem pole! You’re the professor working legally.

Philippe: Well, is working boring for you?

Carter: No. It’s not boring to work, right, but if I had a mother fuckin’ dental plan, a benefit package, a credit union, and all of that … no motherfucker could pull me from my job. I’d be workin’ 24/7, with all the overtime I could get.

A job like this [pointing in the direction of the Christmas tree lot] is only gonna last a month, but I’m tryin’ to get all I could get. Save up enough money for a methadone program.

Philippe: Why can’t you save just as much money when you hit a good lick?

Carter: It depends on the lick. You gotta backtrack from what you had to do to survive up until the time that you was able to hit the lick.

If people took care of you up until that time, you gotta take care of them, naturally, right? And then you go from there on whatever you got left, right, to carry yourself along until you gotta do somethin’ else.

But I have a debt right now. I got a debt every morning. Shit! I wake up and start getting to sniffle – dopesick. I got a debt!

Despite Carter’s jesting, he made a concerted attempt at stability via legal employment. He even gave Jeff $60 from his paycheck to hold for him as the first half of the down payment on a methadone drug treatment program:

Carter: I’m gonna try to get back on the stick. $60, that’s a gram. So you see I’m serious. I swear it. I’m going to try this time while I got a chance to do it right now. The methadone will keep me from buyin’ dope and takin’ breaks to fix every day!

This way I can focus on being clean; on going and getting a valid driver’s license; on getting a drivin’ job; and bein’ able to take a drug test and come up clean.

Carter proved serious in his attempt to extricate himself from his outlaw lifestyle and become a legal worker. He stayed working legally at the lot right through the end of the Christmas season, even though he was never taken off work punishment and was not allowed to earn tips. He was not admitted, however, to the methadone drug treatment program because it had a month-long waiting list, and by the time he was eligible his job had ended. He no longer had the motivation to quit heroin – or the stable income to pay for the for-profit treatment program. Structural forces – the inadequacy of public sector treatment programs and the instability of day labor jobs – conspired to reroute Carter into the outlaw version of his habitus.

The Christmas tree lot owner, who shooed Jeff away for distracting Felix, might not have demonstrated the same tolerance towards Carter, but he was not explicitly racist. He merely hired, fired, rewarded or punished his workers on the basis of performance and market forces. Significantly, some of the African American homeowners in the neighborhood also preferentially hired white or Latino, rather than African American, homeless drug use to perform odd-jobs for them such as cleaning their yards or painting their houses. The Christmas tree owner would be offended were he to be accused of discriminating against and humiliating African Americans in his work-management practices. He would even argue that he was anti-racist because, in subsequent years, he displayed a genuine concern for affirmative action by hiring an African American manager in order to recruit more seasonal black employees. Good intentions, however, do not substantially alter power relations because, as the concept of habitus suggests, the ongoing basis for inequalities is not conscious. It is the result of the logic of practices that emerge from the conjugation of habituses in any given set of fields of power. They enforce ‘… the extraordinary inertia which results from the inscription of social structures in bodies’ (Bourdieu, 2000).

Unlike the Christmas tree lot owner, most of the small business owners who employed off-the-books homeless laborers in the neighborhood were consciously racist. Their interactions with the African American homeless were often purposefully hostile. A Lebanese corner store owner in the neighborhood, for example, was shocked by how the African American lumpen and the homeless more broadly were treated by his colleagues:

I’m not like the other storekeepers. Whenever I have a choice of who to hire, I always hire a black man because I feel that they are discriminated against. Le racisme est le fléaux de l’Amerique (Racism is the scourge of America). Homelessness, too! Giving small amounts of money to the homeless is just a normal human thing to do – something that Americans do not do. In the Middle East you never have homelessness because a homeless person will always be allowed to sleep in the foyer of your building. Here people do not tolerate them. And if they are black, forget it!

Active racism on the part of the general public inhibits other non-criminal means of generating income for the African Americans, such as begging. They do not elicit generous pity from passersby as readily as do the whites. Even the oldest, feeblest-looking African Americans in our network seem to inspire fear and distrust in much of the general public who otherwise contribute spare change to visibly needy white street people. The police also subject the African Americans to more rigorous enforcement of anti-loitering and aggressive panhandling laws than they do to the whites. Consequently, even if they wanted to, the African American homeless do not have the option of generating as significant a proportion of their income from passive begging as do the white street people. They do not, however, discuss their rejection of passive begging as the outcome of limited options due to racism. Instead, they refer to it as a personal disposition. They consider begging to be ‘awkward’ or ‘boring’. They do not describe it as avoiding an experience of racism and humiliation but rather as simply a naturalized fact of their personality, upbringing and sense of personal dignity: ‘I just never, ever could do it. It’s just too … un-me. I just didn’t grow up on doing things like that – begging.’

The whites do not enjoy begging. Most are explicitly ashamed of it. Nevertheless, it is an effective, low-risk way for them to support their heroin habits and almost all of them in our network mobilized a significant portion of their income in that manner. Furthermore, their passive, dejected way of begging reduced their risk of arrest and police harassment.

Kinship and childhood socialization

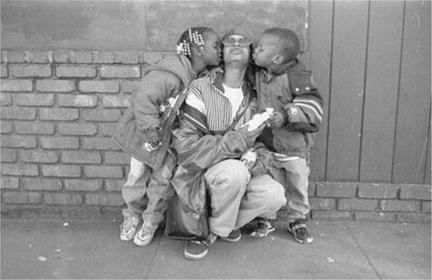

Family and childhood experiences are another crucial generative dimension of habitus. Childhood formations continue to haunt or reward individuals even as their lives unfold and change dramatically. Despite growing up in the same neighborhoods as the whites in our network, all the African Americans spent crucial parts of their adolescence in juvenile correctional facilities due to gang fighting before they began using drugs. In contrast, the whites for the most part were not members of adolescent youth gangs. They initiated their prison careers in their early 20s, only several years after they had become daily heroin injectorswhen they started committing crimes to support their habit. Gang membership in working-class and lumpen communities is often a way for male adolescents to assert their sense of achievement in the context of social marginalization (Bourgois, 1997; Vigil, 2002). It is not surprising, consequently, that the African Americans as adults identify themselves in a celebratory manner as successful outlaws. They also receive respect from youth on the street for being what is known in street parlance as ‘OGs’, that is, original gangsters. In other words, being a street-based outlaw can be a rewarding construction of masculinity for African Americans. Furthermore, even though they have been thrown out of their natal households for stealing, they are usually still in active contact with their relatives, visiting for extended stays over holidays and family reunions. They know their mothers’ phone numbers by heart and the names of the neighborhoods where their children live. Their children even visit them on occasion on the street. There is a certain amount of tolerance and understanding among their kin for their lumpen condition of indigent addiction.

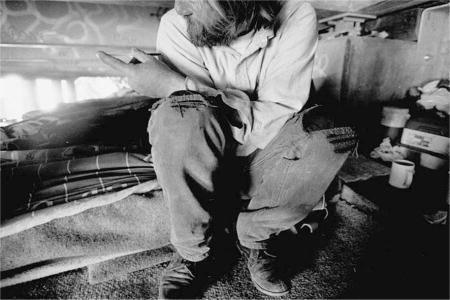

In contrast, the whites are total outcasts from their families as well as pariahs from the larger working-class society from which they originated. This ostracism shames them. They often do not know the city of residence of their mother, father, or even their children. There is no ‘OG’ white masculine space in the lumpen street world or in white working-class families. Their lumpen oppositional masculine options, such as being grey-haired, pony-tailed, pot-bellied bikers with tattoos, or Vietnam veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome, are more pathetic than dignified.

It is not surprising, consequently, that they should feel like failures rather than effective self-respecting outlaws.

Ecstasy versus depression

Most of the same generative forces affecting income-generating strategies also explain why African Americans and whites administer their heroin injections differently.

Heroin users obtain a sudden exhilarating rush of pleasure when they inject intravenously. This way of pursuing pleasure at the moment of getting high has to be understood as part of the embodied dispositions that both express and also form identity.

Outcasts in rags surviving from pitiful begging and humiliating, exploitative part-time labor do not think of themselves as having fun. Instead, they slump their shoulders, stare at the ground despondently, avoid bathing and no longer bother to seek the exhilarating rush of an intravenous injection. Someone who feels like a failure will experience drugs differently. Giving up the pursuit of the intravenous rush of pleasure is consistent with the constellation of dispositions and techniques of the body that characterize the whites: they dress in rags, are malodorous, limp dejectedly with canes and often drink themselves into a stupor before the end of the day. Many of the whites claim that they no longer enjoy their highs. They nod after injecting, but they nod discreetly as if dozing in contrast to the African Americans who will sometimes moan loudly with pleasure and drape their bodies in a relaxed pose.

Considering themselves to be triumphant, resistant and effective outlaws, the African Americans persevere in seeking the pleasure of an exhilarating high. This is consistent with their intimate bodily practices, such as their commitment to staying well-dressed, to bathing against all odds, to walking energetically with shoulders raised and a steady gaze. This way of being is also consistent with maintaining a thick dynamic social network of extended family and of friends and acquaintances (some of them sexualized) on the street.

Habitus, culture and social inequality

These contrasts between African Americans and whites are not merely enduring cultural traits. The critical analytical purpose of the concept of habitus is dissipated if we lose sight of the generative forces in the crucible of symbolic power relations that produce cultural repertoires.

In this case, a close examination of the ethnic dimensions of habitus among the homeless in San Francisco has allowed us to develop a concept that we are calling intimate apartheid. It helps us understand the production and maintenance of dramatic barriers between individuals of different ethnicities who otherwise survive together in close proximity, physically dependent on the very same drugs. In fact, African Americans and whites often sleep, inject, smoke and drink side-by-side in the very same encampments, but remain worlds apart. Marginalized by bourgeois and working-class society, homeless drug users are nevertheless still embroiled in the larger field of power informed by racism in the US – especially those dimensions that are dynamized by the particular US obsession with phenotype.

On one level among the Edgewater homeless, and in popular culture more broadly, cultural distinctions and ethnic styles are expressions of creative diversity. They can be interpreted as a dynamic of resistance to subordination or as an assertion of dignity and self-respect. But these ethnic symbols also carry a valence of power with devastating implications for the socially vulnerable. What we are calling the ethnic components of habitus express themselves as everyday practices, emotions and beliefs that enforce social hierarchies and constrain life choices, trapping entire categories of people into socially structured patterns of suffering. The ethnic components of habitus thereby become an integral dimension of the symbolic violence that legitimizes and administers social hierarchy in the United States, where popular common sense understands subordination as being justified by the moral worth of racial essences. At the same time, writing and photographing ethnically patterned habitus risks reifying the very same stereotypical racialization that we are critiquing (Schonberg and Bourgois, 2002). The concept of intimate apartheid draws on an analysis of the ethnic components of habitus. It is useful for calling attention to the coercive, involuntary and violent genesis of cultural distinctions in the United States at the level of the individual. Intimate apartheid on the street operates at the capillary level, manifesting itself in the devastating practices that fuel dramatic ethnic disparities at the macro-level. For example, in the early 2000s, African American men had six times higher murder rates than white men; their incarceration rates were almost seven times higher; they were over twice as likely to be unemployed; and they were approximately seven times more likely to be infected by HIV (Parker and Pruitt, 2000; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004, 2005; Pettit and Western, 2004; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). Most people in the United States are convinced that the behaviors that propel these ethnic disparities are caused by individual moral flaws that stem from defects in character and/or culture and genotype. They treat ethnic hierarchies as a natural racialized fact that reflects people’s just desserts. They are blind to structural and ideological forces around racism since in everyday interactions individuals – and more importantly categories of individuals defined by skin color – confirm to themselves and others that they deserve their fate. Understanding the ethnic components of habitus and the invisible and unconscious coerciveness of intimate apartheid untangles the symbolic violence that blames victims and hides power. It identifies the brutal play of structural forces that express themselves in everyday behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant DA10164. Comparative and background data was also drawn from NIH grants MH64388, MH78743, NR08324, DA016165, DA017389; and from Russell Sage Foundation 87-03-04, the Wenner Gren Trustee Program, National Endowment for the Humanities RA20229 (through the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton). We thank our study participants for allowing us to document their lives. Laurie Hart’s detailed edits and restructuring of our argument were most helpful. Loïc Wacquant clarified the article’s title just in time. Ann Magruder, Emiliano Bourgois-Chacón, Xarene Eskander, and especially Fernando Montero Castrillo helped with typing and final edits.

Biographies

PHILIPPE BOURGOIS is Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, San Francisco. He is best known for his multiple award-winning book In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio (Cambridge University Press), based on five years living next to a crack house in East Harlem in the late 1980s. Since November 1994 he has been conducting participant-observation with photographer Jeff Schonberg among homeless heroin injectors and crack smokers in San Francisco. They are completing a photo-ethnography entitled Righteous Dopefiend (University of California Press). Dr Bourgois has also worked in Central America, publishing Ethnicity at Work: Divided Labor on a Central American Banana Plantation (Johns Hopkins University Press), as well as four co-edited volumes (including Violence in War and Peace, Blackwell), and over 90 articles on ethnic conflict, immigration, labor conflicts, political violence, HIV, and street children. Address: Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine, University of California, Box 0850, 3333 California Street, San Francisco CA 94143-0850, USA. [email: philippe.bourgois@ucsf.edu]

JEFF SCHONBERG is a photographer and ethnographer currently enrolled in the Joint Doctoral Program in Medical Anthropology at the University of California in San Francisco and in Berkeley. His projects include work on gangs and inner-city violence, street children, the drug economy and social upheaval in South America. He is currently conducting fieldwork among homeless heroin injectors and crack smokers in San Francisco and is co-authoring with Philippe Bourgois Righteous Dopefiend (University of California Press, in press). Address: Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine, University of California, Box 0850, 3333 California Street, San Francisco CA 94143-0850, USA. [email: jasphoto@pacbell.net]

References

- Beck E, Tolnay S. The Killing Fields of the Deep South: The Market for Cotton and the Lynching of Blacks, 1882–1930. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:526–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Pascalian Meditations. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Overachievement in the Underground Economy: The Life Story of a Puerto Rican Stick-up Artist in East Harlem. Free Inquiry for Creative Sociology. 1997;25(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Lettiere M, Quesada J. Social Misery and the Sanctions of Substance Abuse: Confronting HIV Risk among Homeless Heroin Addicts in San Francisco. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):155–73. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard A. Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900–1954. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Homicide Trends in the US: Trends by Race. US Department of Justice; 2004. [accessed 11 August 2005]. electronic document available online at: [ http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/homicide/race.htm] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prison Statistics: Summary Findings on June 30, 2004. US Department of Justice; 2005. [accessed 11 August 2005]. electronic document, available online at: [ http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/prisons.htm] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [accessed 3 August 2005]. electronic document available online at: [ http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/Facts/afam.htm] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Bourgois P, Murphy EL, Kral A, Seal KH, Moore JD, Edlin B. Risk Factors for Abscesses in Injectors of “Black Tar” Heroin: A Cross-Methodological Approach. 128th APHA Annual Meeting; Boston, MA. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. Variation in Youthful Risks of Progression from Alcohol and Tobacco to Marijuana and to Hard Drugs across Generations. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(2):225–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon A. Blacks Pin Hope on DNA to Fill Slavery’s Gaps in Family Trees. The New York Times. 2005 25 July;:1. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss M. Les Techniques du Corps. Journal de Psychologie. 1936;32(3–4):365–86. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Karen F, Pruitt MV. Poverty, Poverty Concentration, and Homicide. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(2):555–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(2):151–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg J, Bourgois P. The Politics of Photographic Aesthetics: Critically Documenting the HIV Epidemic among Heroin Injectors in Russia and the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:387–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil JD. Rainbow of Gangs: Street Cultures in the Mega-City. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. From Slavery to Mass Incarceration: Rethinking the “Race Question” in the US. New Left Review. 2002;13:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Habitus. In: Zafirovski M, editor. International Encyclopedia of Economic Sociology. London: Routledge; 2004. pp. 315–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Race as Civic Felony. International Social Science Journal. 2005;183:127–42. [Google Scholar]