Abstract

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) participates in the control of both motivation and addiction. To test the possibility that opioids in the NAc can cause rats to select ethanol in preference to food, Sprague-Dawley rats with ethanol, food, and water available, were injected with two doses each of morphine, the μ-receptor agonist [D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol]-Enkephalin (DAMGO), the δ-receptor agonist DAla-Gly-Phe-Met-NH2 (DALA), the k-receptor agonist (±)-trans-U-50488 methanesulfonate (U-50,488H), or the opioid antagonist naloxone methiodide (m-naloxone). As an anatomical control for drug reflux, injections were also made 2 mm above the NAc. The main result was that morphine in the NAc significantly increased ethanol and food intake, whereas m-naloxone reduced ethanol intake without affecting food or water intake. Of the selective receptor agonists, DALA in the NAc increased ethanol intake in preference to food. This is in contrast to DAMGO, which stimulated food but not ethanol intake, and the k-agonist U-50,488H, which had no effect on intake. When injected in the anatomical control site 2 mm dorsal to the NAc, the opioids had no effects on ethanol intake. These results demonstrate that ethanol intake produced by morphine in the NAc is driven in large part by the δ-receptor. In light of other studies showing ethanol intake to increase enkephalin expression in the NAc, the present finding of enkephalin-induced ethanol intake suggests the existence of a positive feedback loop that fosters alcohol abuse. Naltrexone therapy for alcohol abuse may then act, in part, in the NAc by blocking this opioid-triggered cycle of alcohol intake.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens; opioids; morphine; naloxone; DAMGO; DALA; U-50,488H; ethanol; microinjection; feeding; rat

1. Introduction

Ethanol is not only a drug of abuse but is also a food containing calories. The nucleus accumbens (NAc), particularly the shell region, participates in the control of drug abuse and food intake [1]. Opioids have been implicated in the rewarding nature of both drugs and food and the motivation to consume them [2–4]. Ethanol intake may therefore be regulated, in part, by opioids in the NAc.

Opioids are well-known for affecting food intake through their actions in the NAc [5]. Studies using in vitro radiography have demonstrated high densities of all three opioid receptors, μ, δ, and k, in the NAc of the rat [6–9]. In general, stimulation of the μ-receptor in the NAc of sated rats produces robust increases in food intake [10–13]. Stimulation of the δ-receptor in this nucleus also increases food intake [12–14], whereas stimulation of the k-receptor does not affect consumption [12].

In addition to influencing eating behavior, opioids have strong effects on the ingestion of ethanol. Peripheral injection studies show that the general opioid agonist morphine has a bimodal effect on voluntary ethanol intake, with low doses stimulating and high doses inhibiting it [4, 15, 16]. Further, the general opioid antagonist, naloxone, decreases ethanol consumption [15–17], and the long-acting opioid antagonist, naltrexone, is used in the treatment of alcohol abuse in humans, particularly in those with the Asp40 allele of the μ-receptor [18, 19]. With central injection studies, naloxone methiodide (m-naloxone), a quaternary derivative of naloxone, is found to decrease operant responding for ethanol, but not water, when injected into the NAc of Wistar rats [20]. Additionally, microinjection of the μ-receptor agonist [D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol]-Enkephalin (DAMGO) in the NAc increases intake of ethanol when food is not available [2], while injection of a μ-receptor antisense oligonucleotide in ethanol-preferring rats can suppress ethanol intake [21]. Other evidence suggests the involvement of the δ-opioid receptor system, showing NAc injection of a δ- but not μ-antagonist to suppress operant responding for ethanol in Wistar rats [22].

In addition to opiates affecting ethanol intake, evidence suggests that the drinking of ethanol can, in turn, alter the endogenous opioid peptides in the NAc. Acute ethanol exposure produces an increase in enkephalin mRNA [23] and the recovery of enkephalin and dynorphin from microdialysis probes in the accumbens [24, 25]. Further, long-term exposure to ethanol affects the binding ability of both the μ- and δ-receptors [26–29]. These findings suggest the existence of a positive feedback loop between the consumption of ethanol and opioid expression or opioid receptor action in the NAc, which may ultimately contribute to alcohol abuse.

To test this hypothesis, the relationship between specific opioid receptor systems and specific consummatory behaviors was examined. Agonists of all three opioid receptors, as well as an antagonist, were microinjected at two doses each in the NAc shell, and their effect on the consumption of ethanol, food, and water was examined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects and home cage conditions

Subjects were male Sprague-Dawley rats from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) that weighed between 200 and 250g at the start of the experiment. They were individually housed in hanging wire cages and maintained on a 12:12-hr light-dark cycle with lights off at 6:00 AM. The subjects had access to LabDiet rodent chow (St. Louis, MO) on an ad libitum basis. Water was always available, either through an automated system when the animals did not have access to ethanol or through graduated cylinders with non-drip sippers attached to the cages when ethanol was present. All procedures used in these studies were approved by the Princeton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Measures were taken to minimize discomfort for the animals.

2.2 Acquisition of oral ethanol intake

Subjects were acclimated to ethanol gradually, using a two-bottle choice procedure as reported previously [30]. Animals were exposed to unsweetened ethanol and water in plastic bottles for 12 h each day, starting 4 h into the dark cycle. Every four days, the concentration of ethanol was increased in the following manner: 1%, 2%, 4%, and 7% (v/v). Surgeries were performed after the subjects had at least 4 d of access to 7% ethanol. Subjects were then allowed one week of recovery before microinjections began. To control for variability of ethanol intake both between individual animals and across weeks, the effects produced by each injection were compared to vehicle injections on counterbalanced consecutive days.

2.3 Surgery

Subjects were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (80 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), supplemented with ketamine when necessary. Guide shafts (21-gauge stainless steel, 10 mm in length) were implanted perpendicularly according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson [31] in the NAc shell (A-P +1.2, L 0.8, V 4.5), with reference to bregma, the midsaggital sinus, and the level skull surface. The injectors protruded 4.5 mm beyond the guide shafts for injection. Injections were made unilaterally, as we have previously found this to be effective in altering consummatory behavior [30]. An anatomical control site 2 mm dorsal to this location was also tested. Other than the time of injection, stainless steel stylets were left in the guide shafts to prevent occlusion.

2.4 Microinjection procedures

All solutions were delivered through concentric microinjectors made of 26-gauge stainless steel outside with fused-silica tubing inside (74 μm ID, 154 μm OD, Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix AZ). The silica injector tip protruded beyond the implanted guide shaft to reach into the region of interest (V 9.0 for NAc shell, V 7.0 for anatomical control). Doses were chosen based on our tests and on literature showing the opioid agonists to increase food intake [10, 12, 32, 33] and the opioid antagonist to suppress operant responding for ethanol [20]. Morphine sulfate (12.7 nmol, 25.4 nmol), the opioid antagonist m-naloxone (3.2 nmol. 6.4 nmol), the selective μ-receptor agonist DAMGO (2.9 nmol, 5.8 nmol), and the k-receptor agonist (±)-trans-U-50488 methanesulfonate (U-50,488H, 10.7 nmol, 21.4 nmol) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). The δ-receptor agonist was D-Ala-Gly-Phe-Met-NH2 (DALA; 7.1 nmol, 14.2 nmol), from American Peptide Co. Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Drugs were dissolved in preservative-free 0.9% NaCl solution (Hospira Inc, Lake Forest, IL) and prepared fresh immediately prior to microinjection.

To minimize stress from injections, the animals were handled extensively throughout their ethanol training prior to the initiation of the tests. Injections were counterbalanced so that each animal received vehicle or peptide in opposite order on two consecutive days, and they were given 3.5 hours into the dark cycle, 30 min prior to daily ethanol access. All injections were made using a syringe pump, which infused 0.5 μl during 47 sec at a flow rate of 0.6 μl/min, with the microinjector remaining in place for another 47 sec prior to removal to allow diffusion. Ethanol, food and water intake were measured every hour for three hours after ethanol access starting from 30 min after all injections, to allow any initial sedative effects to abate [12, 34]. Each group received tests with only a single peptide or drug, with a week elapsing between sets of injections to allow full recovery from the prior injection. For the anatomical control location, drugs were tested in a single group of animals at the most effective dose in the NAc.

2.5 Blood ethanol assessment

To determine blood ethanol concentration (BEC), tail vein blood was sampled 2.5 hours after the start of daily ethanol access approximately one week after completion of the set of microinjections and was analyzed using an Analox GM7 Fast Enzymatic Metabolic Analyser (Luneburg, MA). At this time point, mean BEC for all groups averaged 18.9 ± 4.0 mg/dl.

2.6 Histology and data analysis

Injection sites were verified by injecting 0.25 μl methylene blue dye (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Brains were kept in formalin for a minimum of 1 week prior to slicing, then cut in 40 μm sections on a freezing microtome and slide-mounted for microscopic verification. Behavioral data from animals with injector tips in the region of interest were included in the analysis; those with probes 0.5 mm or farther from the target regions, 1 to 2 animals per group, were discarded from the analysis. In addition, animals consuming little ethanol on measurement days (less than 0.35 g/kg during 4 h) were excluded from the analysis.

The measures of ethanol, food, and water intake were statistically analyzed with tests of the simple effects of each dose and time point for the different compounds, using paired, two-tailed t-tests [35]. As the behavioral effects of opioid injections are known to vary heavily over time [36], and the doses used for each compound were within the same order of magnitude, an overall repeated-measures ANOVA could not be employed. In the figures, data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the difference (SED) between drug and vehicle as recommended for paired t-tests [35]. The vehicle intake presented is the average between the two injections, as intake after vehicle did not significantly differ within each group.

3. Results

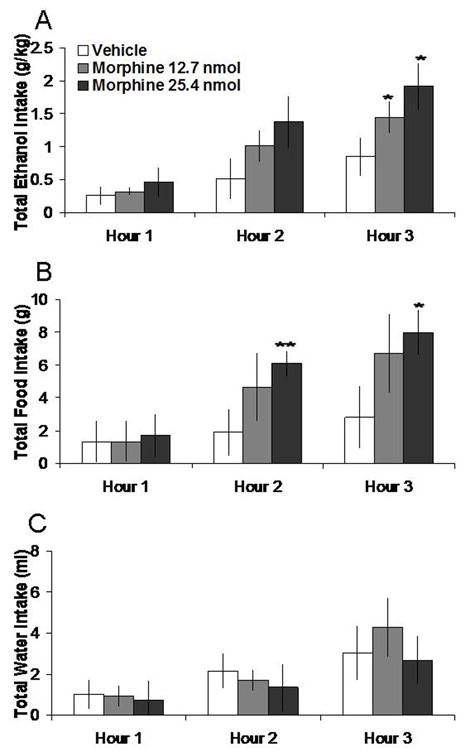

3.1 Morphine microinjections in the NA increase both ethanol and food intake

Injection of morphine in the NAc, compared to vehicle, increased 7% ethanol and food intake. Tests of the simple effects (Fig. 1) showed that morphine at the 3 h time-point increased ethanol intake by 82% at the 12.7 nmol dose (t = 2.81, df = 4, p < 0.05) and by 112% at the 25.4 nmol dose (t = 2.98, df = 4, p < 0.05). Morphine at the higher dose of 25.4 nmol also stimulated food intake, causing a 144% increase at 2 h (t = 4.93, df = 4, p < 0.01) and 171% increase at 3 h (t = 3.75, df = 4, p < 0.05). Neither dose altered water intake, as illustrated in Figure 1. Morphine in the anatomical control site 2 mm above the NAc had no significant effects on intake of ethanol, food, or water (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of morphine injection (12.7 nmol, 25.4 nmol, n = 5) in the NAc on ethanol, food, and water consumption in the dark. A. Morphine at both doses stimulates 7% ethanol intake. B. The higher dose of morphine stimulates food intake. C. Morphine does not significantly affect water intake. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. The vehicle shown is averaged from both injections.

Table 1.

Injection in the anatomical control location, 2 mm dorsal to the NAc, does not significantly affect ethanol intake, but alters food and water intake in a few cases (n = 5).

Anatomical control injection effects on ethanol, food, and water intake

| Drug | Nutrient | Hour 1 | Hour 2 | Hour 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Morphine 25.4 nmol |

Ethanol (g/kg) | 0.34 ± 0.09 0.19 ± 0.04 |

0.56 ± 0.16 0.41 ± 0.11 |

0.86 ± 0.28 0.56 ± 0.12 |

| Vehicle Morphine 25.4 nmol |

Food (g) | 1.30 ± 0.36 0.54 ± 0.42 |

2.70 ± 0.76 1.14 ± 0.56 |

3.26 ± 0.63 4.20 ± 0.60 |

| Vehicle Morphine 25.4 nmol |

Water (ml) | 1.44 ± 0.54 0.50 ± 0.22 |

3.10 ± 0.59 1.74 ± 0.74 |

4.56 ± 0.77 3.30 ± 1.17 |

| Vehicle M-naloxone 6.4 nmol |

Ethanol (g/kg) | 0.35 ± 0.12 0.30 ± 0.08 |

0.59 ± 0.16 0.58 ± 0.11 |

0.85 ± 0.23 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| Vehicle M-naloxone 6.4 nmol |

Food (g) | 1.26 ± 0.77 0.36 ± 0.27 |

2.90 ± 1.19 1.76 ± 0.39 |

3.90 ± 1.25 4.20 ± 0.68 |

| Vehicle M-naloxone 6.4 nmol |

Water (ml) | 2.20 ± 0.67 1.42 ± 0.22 |

4.26 ± 1.03 3.18 ± 0.83* |

5.92 ± 1.26 4.88 ± 1.41 |

| Vehicle DAMGO 5.8 nmol |

Ethanol (g/kg) | 0.42 ± 0.12 0.15 ± 0.05 |

0.64 ± 0.17 0.59 ± 0.15 |

0.86 ± 0.24 1.06 ± 0.29 |

| Vehicle DAMGO 5.8 nmol |

Food (g) | 1.36 ± 0.35 1.58 ± 0.65 |

3.08 ± 0.94 4.94 ± 1.03 |

4.14 ± 0.41 5.40 ± 1.00 |

| Vehicle DAMGO 5.8 nmol |

Water (ml) | 1.32 ± 0.51 1.80 ± 0.89 |

3.14 ± 1.54 4.62 ± 1.86 |

3.88 ± 1.68 6.34 ± 1.99 |

| Vehicle DALA 14.2 nmol |

Ethanol (g/kg) | 0.30 ± 0.15 0.41 ± 0.17 |

0.55 ± 0.16 0.67 ± 0.18 |

0.77 ± 0.19 0.83 ± 0.20 |

| Vehicle DALA 14.2 nmol |

Food (g) | 2.43 ± 0.50 2.20 ± 0.60 |

4.64 ± 0.39 2.38 ± 0.68* |

5.52 ± 0.48 3.12 ± 0.89 |

| Vehicle DALA 14.2 nmol |

Water (ml) | 2.00 ± 0.55 3.90 ± 1.23 |

4.16 ± 1.09 6.00 ± 1.14** |

5.80 ± 1.24 7.18 ± 1.04 |

| Vehicle U-50,488H 2.2 nmol |

Ethanol (g/kg) | 0.26 ± 0.10 0.39 ± 0.11 |

0.52 ± 0.11 0.56 ± 0.11 |

0.78 ± 0.20 0.82 ± 0.16 |

| Vehicle U-50,488H 2.2 nmol |

Food (g) | 1.06 ± 0.85 1.90 ± 0.79 |

3.12 ± 0.78 3.34 ± 0.82 |

3.82 ± 1.05 3.82 ± 1.08 |

| Vehicle U-50,488H 2.2 nmol |

Water (ml) | 1.72 ± 0.32 1.94 ± 0.58 |

3.00 ± 0.39 3.88 ± 0.87 |

4.98 ± 0.90 4.98 ± 1.10 |

Values are mean ± S.E.M.,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

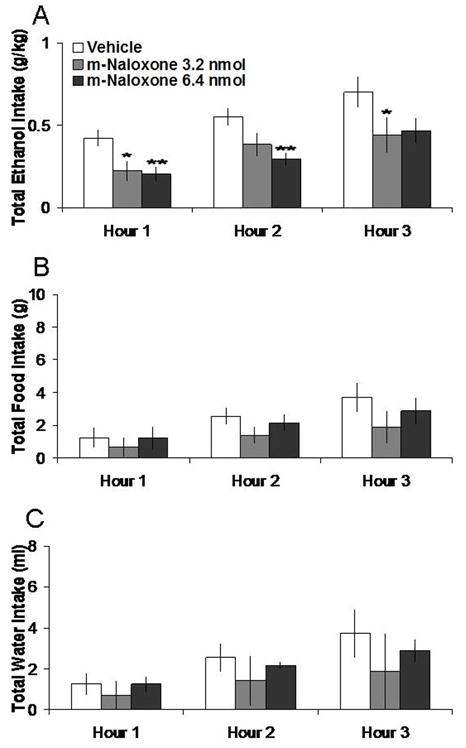

3.2 M-naloxone microinjection in the NAc decreases ethanol intake

Injection of m-naloxone in the NAc, compared to vehicle, selectively decreased 7% ethanol intake. Tests of the simple effects (Fig. 2) revealed that m-naloxone at the 3.2 nmol dose decreased ethanol intake by 43% at 1 h (t = 2.94, df = 4, p < 0.05) and by 41% at 3 h (t = 2.89, df = 4, p < 0.05). At the 6.4 nmol dose, m-naloxone similarly decreased ethanol intake, by 54% at 1 h (t = 5.78, df = 4, p < 0.01) and by 47% at 2 h (t = 7.33, df = 4, p < 0.01). Neither dose affected food or water intake, as illustrated in Figure 2. M-naloxone in the anatomical control site 2 mm above the NAc had no significant effects on intake of ethanol or food but suppressed water intake at the 3 h time-point (t = 4.01, df = 4, p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Effects of m-naloxone injection (3.2 nmol, 6.4 nmol, n = 5) in the NAc on ethanol, food, and water consumption. A. M-naloxone at both doses suppresses 7% ethanol intake. B. M-naloxone does not significantly affect food intake. C. M-naloxone does not significantly affect water intake. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. The vehicle shown is averaged from both injections.

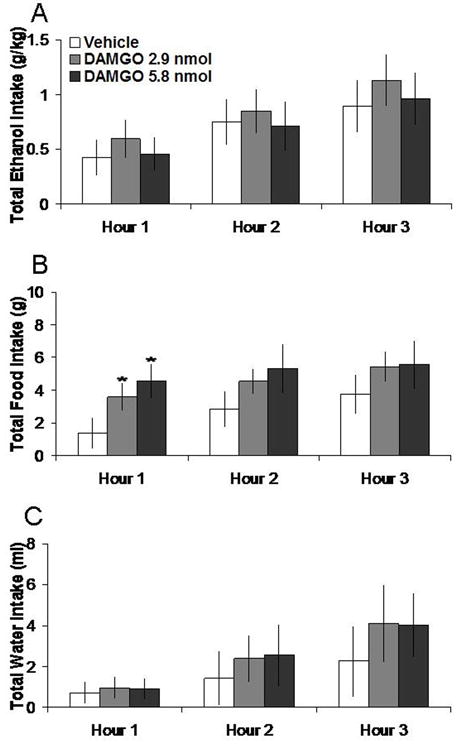

3.3 DAMGO microinjection in the NAc increases food intake

Injection of DAMGO in the NAc, compared to vehicle, did not significantly affect 7% ethanol but instead enhanced food intake. Tests of the simple effects (Fig. 3) revealed that DAMGO at the 2.9 nmol dose increased food intake by 181% at 1 h (t = 2.80, df = 4, p < 0.05), while at the 5.8 nmol dose, it increased it by 205% at 1 h (t = 3.00, df = 4, p < 0.05). Neither dose significantly altered ethanol or water intake, as illustrated in Figure 3. Injection of DAMGO in the anatomical control site had no significant effects on intake of ethanol, food, or water (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Effects of DAMGO (2.9 nmol, 5.8 nmol, n = 5) in the NAc on ethanol, food, and water consumption. A. DAMGO does not significantly affect 7% ethanol intake. B. DAMGO at both doses increases food intake. C. DAMGO does not significantly affect water intake. *p < 0.05. The vehicle shown is averaged from both injections.

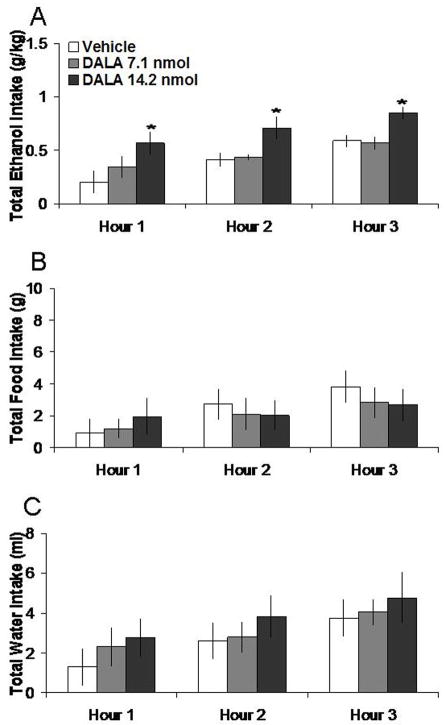

3.4 DALA microinjection in the NAc increases ethanol intake

Injection of DALA in the NAc, compared to vehicle, selectively enhanced 7% ethanol intake. Tests of the simple effects showed that it increased ethanol intake by 221% at the 1 h time-point (t = 3.66, df = 4, p < 0.05), by 70% at the 2 h time-point (t = 2.83, df = 4, p < 0.05), and by 31% at the 3 h time-point (t = 3.53, df = 4, p < 0.05). The lower dose of DALA did not significantly affect ethanol intake. In addition, neither dose significantly altered food or water intake, as illustrated in Figure 4. Injection of DALA in the anatomical control site had no significant impact on intake of ethanol, but lowered food intake at 2h (t = 3.07, df = 4, p < 0.05) and increased water intake at 3 h (t = 5.27, df = 4, p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Effects of DALA (7.1 nmol, 14.2 nmol, n = 5) in the NAc on ethanol, food, and water consumption. A. DALA at the higher dose significantly increases 7% ethanol intake. B. DALA does not significantly affect food intake. C. DALA does not significantly affect water intake. *p < 0.05. The vehicle shown is averaged from both injections.

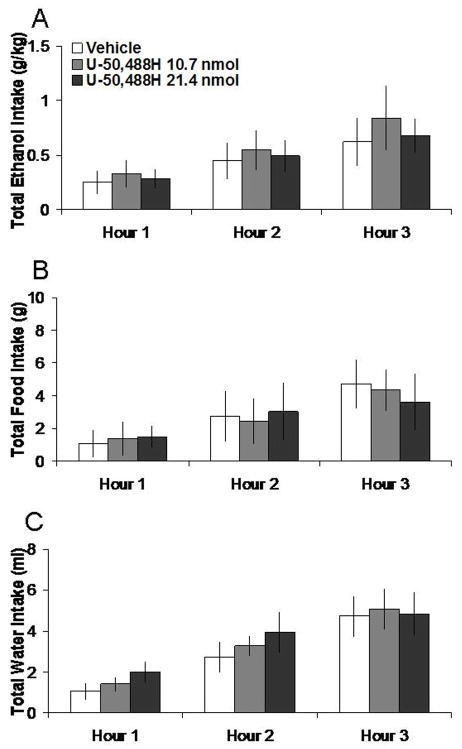

3.5 Kappa agonist microinjection in the NAc does not affect ethanol intake

Unlike the other agonists, U-50,488H in the NAc at 10.7 nmol or 21.4 nmol had no significant effects on intake of 7% ethanol, food, or water. These data are illustrated in Figure 5. Additionally, U-50,488H in the anatomical control site had no impact on intake of ethanol, food, or water (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Effects of U-50,488H (10.7 nmol, 21.4 nmol, n = 5) in the NAc on ethanol, food, and water consumption. A. U-50,488H does not significantly affect 7% ethanol intake. B. U-50,488H does not significantly affect food intake. C. U-50,488H does not significantly affect water intake. The vehicle shown is averaged from both injections.

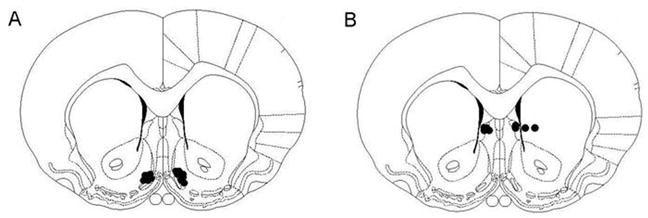

Histology

Histological verification revealed that NAc injections were made into the medial shell region of the NAc (Fig. 6A). The anatomical control injections were made into the intermediate part of the lateral septal nucleus and the caudate putamen (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Injection sites for all drugs. A. NAc injections. B. Control injections. All injections were unilateral. Black dots indicate injector placement for animals included in data analysis. Sections are +1.2 mm from Bregma along the rostral-caudal axis. Adapted from The Rat Brain, compact 3rd edition, G. Paxinos and C. Watson, Copyright 1997, with permission from Elsevier.

4. Discussion

In this study, morphine injected in the NAc shell dose-dependently increased voluntary 7% ethanol and food intake, without affecting water intake. The general opioid antagonist m-naloxone selectively decreased ethanol intake without affecting food or water intake. In addition to replicating prior investigations describing the effects of morphine on food intake [37–39], this study provides new evidence for the involvement of NAc opioids in the control of ethanol intake. It demonstrates that ethanol consumption is stimulated by morphine in the NAc while reduced by antagonism of opioid receptors.

As both morphine and m-naloxone act to some degree on all three main opioid receptor types, agonists of each receptor were examined to determine how the activity of each in the NAc shell contributes to ethanol and food consummatory behavior. Interestingly, in ethanol-drinking rats, the μ-receptor agonist, DAMGO, had no effect on ethanol intake and channeled its stimulation into feeding at both doses. In contrast, the δ-receptor agonist, DALA, selectively increased ethanol intake at one dose, while the k-agonist, U-50,488H, produced no change in either ethanol or food intake. These results suggest that the increase in 7% ethanol intake induced by morphine in the NAc with food simultaneously available is most likely due to an increase in activity at the δ-receptor system in this nucleus.

The δ-opioid receptor in the NAc shell may have a special role in controlling ethanol intake with food present. Previous studies have shown that, in ethanol-naïve rats, injection of δ-agonists in the NAc, at doses similar to those used here, produces a significant increase in feeding [12–14]. The present study provides evidence to suggest that this pattern changes dramatically after the animals learn to drink ethanol. That is, when the δ-agonist increases the consumption of ethanol, it no longer affects food intake in ethanol-drinking rats. This finding suggests that chronic availability and consumption of ethanol may mask the feeding-stimulatory effect of δ-opioid stimulation or supplant food as the preferred substance for the opioid-induced appetitive behavior. The greater importance of the δ- rather than the μ-receptors in the NAc shell for the drinking of ethanol is underscored by previous findings that an antagonist of the δ- but not μ-receptor suppresses responding for ethanol [22].

The results obtained with stimulation of the μ-receptor were somewhat surprising. Instead of increasing ethanol intake, DAMGO caused rats in our study to consume more food, similar to the findings in ethanol-naïve subjects [10–12, 14]. The μ-opioid receptor system is believed to have a role in controlling ethanol intake and in the development of alcoholism in humans and laboratory animals [4, 17, 40]. In addition, Zhang and Kelley [2] have shown that DAMGO microinjection in the NAc increases intake of 6% ethanol in Sprague-Dawley rats. A notable difference between that study and the present one is that we also provided food as an alternative source of calories. In studies of food intake, stimulation of μ-opioid receptors in the NAc is found to preferentially increase the ingestion of the more palatable or calorically dense foods [3, 39, 41, 42]. Since Sprague-Dawley rats in taste preference tests show avoidance of ethanol in concentrations above 6% [43, 44], the μ-receptor stimulation in the current study may have led rats to consume the food, which was far more palatable than the bitter 7% ethanol they were given. Further, since laboratory chow contains 4.0 kcal/g gross energy compared to about 0.5 kcal/g for the ethanol solution, caloric content may have also been a factor.

It might be noted that this study was carried out in a species of rat that was not bred to prefer ethanol. The outbred animals were trained to voluntarily consume ethanol by using increasing concentrations of unsweetened ethanol. Thus, their baseline intake was moderate, and their drinking patterns were sometimes variable, commensurate with a model of social or early drinking rather than of alcoholism. It is possible, therefore, that these rats were not consuming ethanol for its post-ingestive pharmacological effects and that injections that affected ethanol intake altered some non-pharmacological property of ethanol drinking. Stimulation of μ-receptors with DAMGO in the NAc not only enhances consumption of a high-fat diet [3, 39] but also preferentially enhances consumption of food containing preferred flavors [45]. In addition, stimulation of these receptors with either DAMGO or morphine in the NAc shell enhances positive hedonic affective responses to the taste of sucrose [46, 47]. While it cannot be ruled out that the changes in ethanol intake in the present study occurred due to altered taste hedonics, this appears less likely given our finding that DAMGO, which is known to enhance positive responses to tastes, enhanced the consumption of food rather than ethanol.

Injections of the opioid peptides in the control site 2 mm dorsal to the NAc shell failed to have any observable effects on ethanol intake, although they did lead to changes in food and water intake in a few cases. Therefore, the behavioral changes produced by injection into the NAc shell, particularly those with ethanol intake, are unlikely to be due to the diffusion of the drug along the cannula tract. Other studies show that injection of 0.5 μl of a solution has a spread of only about 1 mm in diameter [48] and that both morphine and m-naloxone remain fairly restricted to the injection site [48, 49]. From mapping studies, it is important to note that opioids may act in multiple areas of the brain to stimulate feeding [50–52]. In addition to acting in the NAc shell, it cannot be ruled out that the opioids in the present study also affected the nearby NAc core. Prior studies have shown that intake of a high-fat diet is enhanced by injection of DAMGO into either the shell or core [3]. On the other hand, while the NAc shell is critically involved in food intake, the NAc core is believed to be more important in learning how to obtain food [53]. Thus, while the present results point to the NAc shell as an important locus in opioid control of consummatory behavior, they do not exclude the possibility that nearby sites such as the NAc core may also participate in this process.

The circuitry by which NAc opioids increase ethanol intake may involve different pathways. Opioids in the NAc activate an output to the globus pallidus in a circuit that has hedonic impact and fosters prolonged intake of preferred substances [54]. Opioid peptides may also act to increase ethanol intake through their effects on the release of dopamine (DA), which is believed to be important in appetitive responding for ethanol [55, 56]. Peripheral and ventricular administration of μ- and δ-opioid agonists stimulates DA release in the NAc shell, while k-agonists decrease DA release [57–61]. This is consistent with the present finding that the μ- and δ-agonists, but not the k-agonist, stimulate nutrient intake. The release of DA can facilitate the intake of food and water as well as ethanol and other drugs of abuse [55, 62–64]. Conversely, the intake of food, ethanol, and various drugs can cause the release of accumbens DA [65–69], an effect similarly seen with ethanol injected directly into the NAc [70, 71]. We have reported that, when injected in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, the feeding-stimulatory peptides, galanin and opioids, can elicit ethanol intake as well as the release DA in the NAc [72–74]. Together, this evidence suggests a key role for DA in mediating opioid-induced ethanol intake.

In summary, morphine and DALA injected in the NAc shell can stimulate ethanol intake, while m-naloxone diminishes it. In contrast, DAMGO, an agonist of the μ-receptor, stimulates eating rather than intake of 7% ethanol, consistent with the idea that it is the μ-opioid system that relates more to palatability [5, 47, 75]. The finding that DALA can stimulate ethanol intake rather than feeding suggests that the δ-opioid receptor system in the NAc is susceptible to being co-opted by voluntary ethanol consumption. Given ethanol’s known ability to increase the expression and release of endogenous opioids in the NAc shell [23–25], these new findings support a role for accumbens opioids not only in ethanol intake but also in a positive feedback mechanism that fosters the over-consumption of ethanol. Thus, it is possible that opioid-antagonist therapy in alcoholic patients acts, in part, through the NAc reinforcement system.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Miriam Bocarsly for her technical assistance. This research was supported by USPHS Grant AA12882 and the E.H. Lane Foundation.

References

- 1.Gianoulakis C. Endogenous opioids and addiction to alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4(1):39–50. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang M, Kelley A. Intake of saccharin, salt, and ethanol solutions is increased by infusion of a mu opioid agonist into the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;159(4):415–423. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0932-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang M, Kelley A. Enhanced intake of high-fat food following striatal mu-opioid stimulation: microinjection mapping and fos expression. Neuroscience. 2000;99(2):267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulm RR, Volpicelli JR, Volpicelli LA. Opiates and alcohol self-administration in animals. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(Suppl 7):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE, Will MJ. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(5):773–795. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atweh S, Kuhar M. Autoradiographic localization of opiate receptors in rat brain. III. The telencephalon. Brain Res. 1977;134(3):393–405. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis M, Akil H, Watson S. Autoradiographic differentiation of mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors in the rat forebrain and midbrain. J Neurosci. 1987;7(8):2445–2464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman R, Snyder S, Kuhar M, Young Wr. Differentiation of delta and mu opiate receptor localizations by light microscopic autoradiography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77(10):6239–6243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.6239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharif N, Hughes J. Discrete mapping of brain Mu and delta opioid receptors using selective peptides: quantitative autoradiography, species differences and comparison with kappa receptors. Peptides. 1989;10(3):499–522. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(89)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald A, Billington C, Levine A. Alterations in food intake by opioid and dopamine signaling pathways between the ventral tegmental area and the shell of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2004;1018(1):78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar R, Lamonte N, Israel Y, Kandov Y, Ackerman T, Khaimova E. Reciprocal opioid-opioid interactions between the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens regions in mediating mu agonist-induced feeding in rats. Peptides. 2005;26(4):621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakshi V, Kelley A. Feeding induced by opioid stimulation of the ventral striatum: role of opiate receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265(3):1253–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragnauth A, Znamensky V, Moroz M, Bodnar R. Analysis of dopamine receptor antagonism upon feeding elicited by mu and delta opioid agonists in the shell region of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2000;877(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragnauth A, Moroz M, Bodnar R. Multiple opioid receptors mediate feeding elicited by mu and delta opioid receptor subtype agonists in the nucleus accumbens shell in rats. Brain Res. 2000;876(1–2):76–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02631-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbell C, Czirr S, Hunter G, Beaman C, LeCann N, Reid L. Consumption of ethanol solution is potentiated by morphine and attenuated by naloxone persistently across repeated daily administrations. Alcohol. 1986;3(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(86)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;129(2):99–111. doi: 10.1007/s002130050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oswald L, Wand G. Opioids and alcoholism. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(2):339–358. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien C, Volpicelli L, Volpicelli J. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism: a clinical review. Alcohol. 1996;13(1):35–39. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)02038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anton R, Oroszi G, O’Malley S, Couper D, Swift R, Pettinati H, Goldman D. An evaluation of mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) as a predictor of naltrexone response in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE) study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):135–144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyser C, Roberts A, Schulteis G, Koob G. Central administration of an opiate antagonist decreases oral ethanol self-administration in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(9):1468–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers R, Robinson D. Mmu and D2 receptor antisense oligonucleotides injected in nucleus accumbens suppress high alcohol intake in genetic drinking HEP rats. Alcohol. 1999;18(2–3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyytia P, Kiianmaa K. Suppression of ethanol responding by centrally administered CTOP and naltrindole in AA and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(1):25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliva J, Ortiz S, Perez-Rial S, Manzanares J. Time dependent alterations on tyrosine hydroxylase, opioid and cannabinoid CB1 receptor gene expressions after acute ethanol administration in the rat brain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(5):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marinelli P, Bai L, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. A microdialysis profile of Met-enkephalin release in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183008.62955.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinelli P, Lam M, Bai L, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. A microdialysis profile of dynorphin A(1–8) release in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(6):982–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliva J, Manzanares J. Gene transcription alterations associated with decrease of ethanol intake induced by naltrexone in the brain of Wistar rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(6):1358–1369. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charness ME, Gordon AS, Diamond I. Ethanol modulation of opiate receptors in cultured neural cells. Science. 1983;222(4629):1246–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.6316506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charness ME, Querimit LA, Diamond I. Ethanol increases the expression of functional delta-opioid receptors in neuroblastoma × glioma NG108-15 hybrid cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(7):3164–3169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charness ME, Hu G, Edwards RH, Querimit LA. Ethanol increases delta-opioid receptor gene expression in neuronal cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44(6):1119–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider E, Rada P, Darby R, Leibowitz S, Hoebel B. Orexigenic peptides and alcohol intake: differential effects of orexin, galanin, and ghrelin. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(11):1858–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paxinos G, Watson C. Compact. 3. xxxiii. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. The rat brain, in stereotaxic coordinates; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majeed NH, Przewlocka B, Wedzony K, Przewlocki R. Stimulation of food intake following opioid microinjection into the nucleus accumbens septi in rats. Peptides. 1986;7(5):711–716. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakshi VP, Kelley AE. Sensitization and conditioning of feeding following multiple morphine microinjections into the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1994;648(2):342–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox R, Bozarth M, Levitt R. Reversal of morphine-induced catalepsy by naloxone microinjections into brain regions with high opiate receptor binding: a preliminary report. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keppel G, Wickens T. Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook. 4. Upper Saddle River; New Jersey, Prentice Hall: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craft RM. Sex differences in analgesic, reinforcing, discriminative, and motoric effects of opioids. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16(5):376–385. doi: 10.1037/a0012931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakshi V, Kelley A. Striatal regulation of morphine-induced hyperphagia: an anatomical mapping study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;111(2):207–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02245525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mucha RF, Iversen SD. Increased food intake after opioid microinjections into nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area of rat. Brain Res. 1986;397(2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Gosnell B, Kelley A. Intake of high-fat food is selectively enhanced by mu opioid receptor stimulation within the nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285(2):908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koob G, Roberts A, Kieffer B, Heyser C, Katner S, Ciccocioppo R, Weiss F. Animal models of motivation for drinking in rodents with a focus on opioid receptor neuropharmacology. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2003;16:263–281. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47939-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley A, Bakshi V, Haber S, Steininger T, Will M, Zhang M. Opioid modulation of taste hedonics within the ventral striatum. Physiol Behav. 2002;76(3):365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olszewski PK, Shaw TJ, Grace MK, Hoglund CE, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB, Levine AS. Complexity of neural mechanisms underlying overconsumption of sugar in scheduled feeding: Involvement of opioids, orexin, oxytocin and NPY. Peptides. 2009;30(2):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tordoff M, Alarcon L, Lawler M. Preferences of 14 rat strains for 17 taste compounds. Physiol Behav. 2008:308–332. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrow N, Kiefer S, Metzler C. Gustatory and olfactory contributions to alcohol consumption in rats. Alcohol. 1993;10(4):263–267. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woolley JD, Lee BS, Fields HL. Nucleus accumbens opioids regulate flavor-based preferences in food consumption. Neuroscience. 2006;143(1):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pecina S, Berridge KC. Opioid site in nucleus accumbens shell mediates eating and hedonic ‘liking’ for food: map based on microinjection Fos plumes. Brain Res. 2000;863(1–2):71–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pecina S, Berridge K. Hedonic hot spot in nucleus accumbens shell: where do mu-opioids cause increased hedonic impact of sweetness? J Neurosci. 2005;25(50):11777–11786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2329-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melzacka M, Nesselhut T, Havemann U, Vetulani J, Kuschinsky K. Pharmacokinetics of morphine in striatum and nucleus accumbens: relationship to pharmacological actions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23(2):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schroeder RL, Weinger MB, Vakassian L, Koob GF. Methylnaloxonium diffuses out of the rat brain more slowly than naloxone after direct intracerebral injection. Neurosci Lett. 1991;121(1–2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90678-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gosnell B, Morley J, Levine A. Opioid-induced feeding: localization of sensitive brain sites. Brain Res. 1986;369(1–2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanley BG, Lanthier D, Leibowitz SF. Multiple brain sites sensitive to feeding stimulation by opioid agonists: a cannula-mapping study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31(4):825–832. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levine A. The animal model in food intake regulation: examples from the opioid literature. Physiol Behav. 2006;89(1):92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelley AE. Functional specificity of ventral striatal compartments in appetitive behaviors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:71–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith KS, Berridge KC. Opioid limbic circuit for reward: interaction between hedonic hotspots of nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2007;27(7):1594–1605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4205-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Czachowski CL, Chappell AM, Samson HH. Effects of raclopride in the nucleus accumbens on ethanol seeking and consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(10):1431–1440. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzales RA, Job MO, Doyon WM. The role of mesolimbic dopamine in the development and maintenance of ethanol reinforcement. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103(2):121–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlezon WJ, Beguin C, DiNieri J, Baumann M, Richards M, Todtenkopf M, Rothman R, Ma Z, Lee D, Cohen B. Depressive-like effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316(1):440–447. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Badiani A, Rajabi H, Nencini P, Stewart J. Modulation of food intake by the kappa opioid U-50,488H: evidence for an effect on satiation. Behav Brain Res. 2001;118(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(14):5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Opposite effects of mu and kappa opiate agonists on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and in the dorsal caudate of freely moving rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244(3):1067–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg T. The effects of opioid peptides on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1990;55(5):1734–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baldo BA, Sadeghian K, Basso AM, Kelley AE. Effects of selective dopamine D1 or D2 receptor blockade within nucleus accumbens subregions on ingestive behavior and associated motor activity. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137(1–2):165–177. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pal GK, Thombre DP. Modulation of feeding and drinking by dopamine in caudate and accumbens nuclei in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1993;31(9):750–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samson HH, Chappell A, Slawecki C, Hodge C. The effects of microinjection of d-amphetamine into the n. accumbens during the late maintenance phase of an ethanol consumption bout. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca M, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, Lecca D. Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hernandez L, Hoebel BG. Food reward and cocaine increase extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens as measured by microdialysis. Life Sci. 1988;42(18):1705–1712. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rada P, Mark G, Pothos E, Hoebel B. Systemic morphine simultaneously decreases extracellular acetylcholine and increases dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30(10):1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weiss F, Parsons L, Schulteis G, Hyytia P, Lorang M, Bloom F, Koob G. Ethanol self-administration restores withdrawal-associated deficiencies in accumbal dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine release in dependent rats. J Neurosci. 1996;16(10):3474–3485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03474.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson C, Nomikos GG, Collu M, Fibiger HC. Dopaminergic correlates of motivated behavior: importance of drive. J Neurosci. 1995;15(7 Pt 2):5169–5178. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ericson M, Molander A, Lof E, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Ethanol elevates accumbal dopamine levels via indirect activation of ventral tegmental nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;467(1–3):85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tuomainen P, Patsenka A, Hyytia P, Grinevich V, Kiianmaa K. Extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens in AA and ANA rats after reverse microdialysis of ethanol into the nucleus accumbens or ventral tegmental area. Alcohol. 2003;29(2):117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rada P, Mark GP, Hoebel BG. Galanin in the hypothalamus raises dopamine and lowers acetylcholine release in the nucleus accumbens: a possible mechanism for hypothalamic initiation of feeding behavior. Brain Res. 1998;798(1–2):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rada P, Avena N, Leibowitz S, Hoebel B. Ethanol intake is increased by injection of galanin in the paraventricular nucleus and reduced by a galanin antagonist. Alcohol. 2004;33(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barson J, Rada P, Leibowitz S, Hoebel B. Neuroscience 2008. Society for Neuroscience; Washington, DC: 2008. Opioids in the hypothalamus raise dopamine and lower acetylcholine release in the nucleus accumbens. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giraudo SQ, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Differential effects of neuropeptide Y and the mu-agonist DAMGO on ‘palatability’ vs. ‘energy’. Brain Res. 1999;834(1–2):160–163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]