Abstract

Endocannabinoids, endogenous lipid ligands of cannabinoid receptors, mediate a variety of effects similar to those of marijuana. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are highly abundant in the brain and mediate psychotropic effects, which limits their value as a potential therapeutic target. There is growing evidence for CB1 receptors in peripheral tissues that modulate a variety of functions, including pain sensitivity and obesity-related hormonal and metabolic abnormalities. In this review we propose that selective targeting of peripheral CB1 receptors has potential therapeutic value because it would help to minimize addictive, psychoactive effects in the case of CB1 agonists used as analgesics, or depression and anxiety in the case of CB1 antagonists used in the management of cardiometabolic risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome.

Introduction

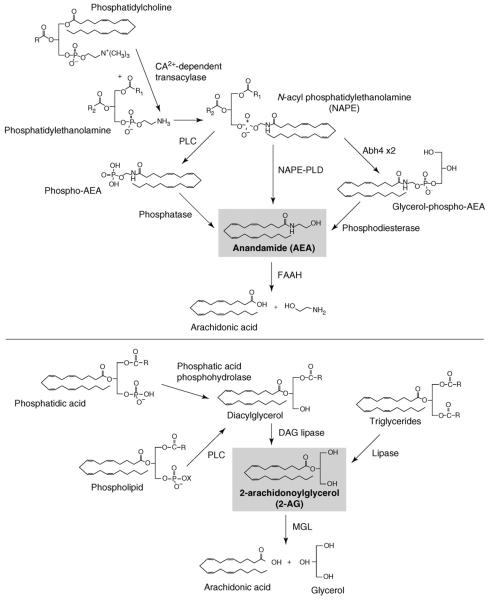

The age-old use of cannabis has acquainted humankind with the potent effects of this plant on mood and sensory perception. However, as reflected in its empirical use for medicinal purposes over the centuries, cannabis can cause many other effects, such as alleviating pain and nausea, increasing appetite or suppressing disturbed gastrointestinal motility and secretions, all of which have become a source of growing interest due to their potential therapeutic exploitation. The discovery of specific cell membrane receptors for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive ingredient of cannabis, was followed by the isolation and identification of endogenous ligands, called endocannabinoids (reviewed in Ref. [1]). Endocannabinoids are lipid mediators generated in the cell membrane from phospholipid precursors via multiple, parallel biosynthetic pathways (Figure 1) [2]. The two main endocannabinoids are arachidonoyl ethanolamine or anandamide, selectively degraded by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), selectively degraded by monoglyceride lipase (MGL) (Figure 1). They interact with the same receptors that recognize the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana (cannabis) and can produce similar biological effects. To date, two G-protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors have been identified: CB1, expressed at very high levels in the brain but also present at lower yet functionally relevant levels in many peripheral tissues, and CB2, expressed predominantly although not exclusively in cells of the immune and hematopoietic systems [1]. Selective pharmacological inhibitors of cannabinoid receptors and mouse strains deficient in these receptors have been key tools in uncovering a growing list of biological functions that are under tonic control by endocannabinoids. Not surprisingly, this has focused attention on the endocannabinoid system as a potential target for pharmacotherapy [1]. To date, the primary focus has been on the CB1 receptor as a druggable target, because of its well-documented role in the control of pain, nausea, mood and anxiety, appetite, and drug and alcohol reward. All of these effects involve activation of CB1 receptors in the central nervous system, and therein lies the dilemma. The medicinal use of cannabis has provided ample evidence for its efficacy in relieving not only pain and nausea but also anxiety. However, the psychoactive properties of cannabis and its potent synthetic analogs preclude their general use as therapeutics. Although CB1 receptors responsible for the addictive nature of cannabis and those implicated in analgesia, antinausea or anxiolytic effects might be located at distinct sites in the brain [3], they are pharmacologically indistinguishable. The same conundrum is faced when CB1 receptor blockade is considered for therapeutic purposes. The role of CB1 receptors in the central neural control of appetite [4] and evidence for the tonic activity of the endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor system in obesity [5,6] provide a rationale for the use of CB1 antagonists as antiobesity agents. However, an increased incidence of anxiety and depression in obese patients treated with the first such CB1 antagonist, rimonabant [7], limits the usefulness of such compounds, because these side effects most likely represent a ‘class’ effect due to blockade of CB1 receptors in the CNS. A potential resolution of this dilemma might be suggested by recently emerging evidence for the existence and functional relevance of a peripheral endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor system [5,6,8-11]. We briefly review such evidence and its potential therapeutic significance, with a focus on inflammatory pain and the metabolic syndrome as examples of conditions that could benefit from the availability of peripherally restricted CB1 agonists or antagonists, respectively.

Figure 1.

Enzymatic pathways of the biosynthesis and degradation of the two main endocannabinoids, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Note that both endocannabinoids can be generated by multiple, parallel biosynthetic pathways, whereas their enzymatic degradation occurs predominantly through a single, selective pathway. Selective inhibition of the degrading enzymes FAAH and MGL might have therapeutic potential in conditions where an increase in endocannabinoid tone is desirable.

CB1 receptors involved in pain control

A time-honored target of screening chemical compounds for cannabinoid-like activity in rodents has been the ‘Billy Martin-tetrad’ [12]—analgesia, hypomotility, catalepsy and hypothermia—establishing pain relief as one of the defining features of a cannabinoid. Until recently, it had been widely assumed that CB1 receptor-induced analgesia is centrally mediated, which is not surprising in view of the predominant expression of CB1 receptors in the brain, including various sites involved in pain control. Evidence that CB2 [13], TRPV1 [14], and possibly GPR55 [15] receptors might also contribute to the analgesic effect of cannabinoids will not be discussed in this brief review. As far as CB1 receptors are concerned, there is ample evidence for their presence in various structures in the spinal cord and brain that are involved in pain regulation and in the affective response to nociceptive stimuli. The analgesic response to microinjection of cannabinoids into such sites and their inhibition by similar localized or systemic administration of a CB1 antagonist [16] are evidence for their role in cannabinoid-induced analgesia. However, such evidence does not exclude the possible involvement of additional, peripherally located CB1 receptors in the analgesic response to systemically administered CB1 agonists. CB1 receptors are expressed by neurons in the dorsal root ganglia [17] and are axonally transported to peripheral sensory nerve terminals [18]. Both the expression and axonal transport of CB1 receptors in these neurons appear to be increased in response to peripheral inflammation [19].

Peripheral CB1 receptors and inflammatory pain

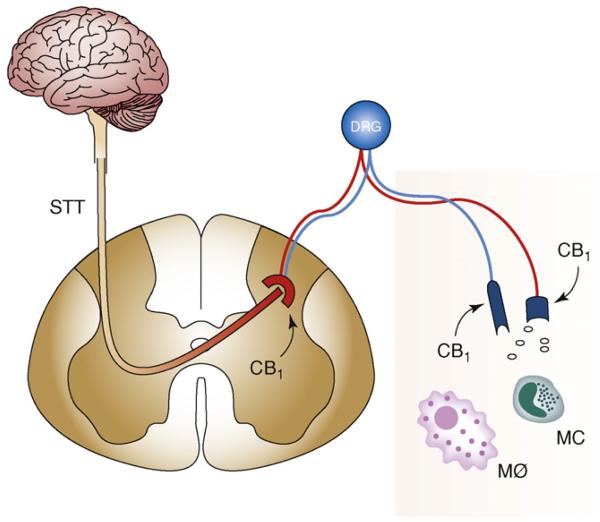

The role of CB1 receptors in peripheral sensory nerve terminals in cannabinoid-induced relief of inflammatory/neuropathic pain was suggested by several lines of evidence (Figure 2). In inflammatory pain models such as carrageenan-induced paw edema or heat injury to the paw, microinjection into the affected paw of low doses of cannabinoids, including highly selective CB1 agonists such as arachidonoyl-2-chloroethylamide, caused analgesia [20] and inhibition of noxious, mechanically evoked responses of dorsal horn neurons [21]. These effects could be prevented by a CB1 receptor antagonist injected into the affected paw or administered systemically [20,22]. The possibility that spillover of the agonist into the systemic circulation might be required for the analgesia to develop was discounted by the lack of an analgesic response when the same dose of the agonist was microinjected into the contralateral paw. CB1 receptors in the inflamed paw might also be targeted by endocannabinoids, which were reported to be present in the skin at levels sufficient to activate CB1 receptors [23]. These receptors might be tonically activated during inflammation as a result of an injury-induced increase in the tissue levels of 2-AG [24,25]. Such tonic CB1 activation is also reflected by the enhanced and prolonged pain response following CB1 antagonist treatment [23].

Figure 2.

Peripheral mechanism of CB1-mediated analgesia in inflammatory/neuropathic pain. CB1 receptors in DRG neurons are axonally transported to peripheral sensory nerve terminals via C fibers. Their activation by locally released endocannabinoids or exogenous CB1 agonists counteracts inflammatory/neuropathic pain. STt, spinothalamic tract; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; MC, mast cell; Mø, macrophage.

Global genetic ablation of CB1 receptors confirmed their role in cannabinoid-induced analgesia [26,27] but did not identify the location of the receptors involved. In a recent study, CB1 receptors were selectively ablated in primary nociceptive sensory neurons [24]. As a result, CB1 receptors were significantly reduced in dorsal root ganglion neurons owing to their selective loss from small diameter C- and A-δ neurons, without any change in CB1 receptors elsewhere, including the central nervous system. Mice with the selective knockout displayed enhanced basal pain sensitivity to noxious heat or mechanical stimuli and increased neuropathic pain induced by nerve injury, and a markedly reduced analgesic response to locally or systemically, but not intrathecally, administered cannabinoids [24]. These findings strongly suggest that by suppressing pain initiation, activation of peripheral CB1 receptors is paramount in the analgesic response to systemically administered cannabinoids, at least for inflammatory pain. As a corollary, a CB1 agonist with reduced brain penetration would be expected to retain analgesic efficacy with much reduced or absent CNS side effects. Indeed, a recently developed, peripherally restricted CB1/CB2 agonist (respective binding IC50s of 15 and 98 nM) has been reported to be a potent analgesic in a rat neuropathic pain model, but to cause no significant catalepsy at the maximal analgesic dose [28]. The analgesia was mediated by CB1 receptors, as indicated by its prevention by pre-treatment with a CB1 but not with a CB2 antagonist. Interestingly, despite its low brain penetration, this CB1 agonist displayed good oral bioavailability and efficacy [28], an important practical requirement for potential future therapeutic application.

It needs to be pointed out that there might be alternative strategies to minimize unwanted CNS side effects of global CB1 receptor activation. Potentiation of the action of endogenous anandamide by blocking its degradation with the FAAH inhibitor URB597 produces CB1-mediated analgesia without causing behavioral effects predictive of addictive potential [2]. Also, oromucosal administration of Sativex, a cannabis extract containing cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, was found to alleviate neuropathic pain without causing significant psychotropic effects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled human clinical trial [29]. In this case, the presence of the nonpsychotropic cannabidiol in the mixture and/or self-titration of the medication by patients to minimize side effects might have contributed to the lack of significant psychotropic effects [29].

CB1 receptors and metabolic regulation in obesity

Smoking cannabis increases appetite. Tolerance develops to this effect upon chronic exposure, yet the parallel weight gain is maintained, suggesting that the latter cannot be entirely accounted for by increased caloric intake [30]. The reciprocal of this observation was documented in one of the first studies examining appetite suppression by CB1 receptor blockade. On chronic administration to rats, the CB1 antagonist rimonabant reduced food intake transiently, but caused a lasting reduction in body weight [31], again pointing to a metabolic effect independent of energy intake. This conclusion gained further support by several additional observations. First, CB1-receptor-deficient mice have a lean phenotype relative to their wild-type littermates, and the difference remains unaffected on pair feeding in the adult animals, indicating increased energy expenditure in the latter [8]. Second, in mice with high-fat diet-induced obesity (DIO), chronic treatment with rimonabant caused a transient reduction in food intake but a sustained reduction of body weight [32,33]. This indicates that CB1 blockade must increase energy expenditure, which recently received direct experimental support [26,34]. Third, CB1 receptor-deficient C57Bl6 mice are resistant to DIO despite their overall caloric intake being identical to that in their wild-type littermates that do become obese on the same diet [4,28].

DIO in C57Bl6 mice is actually a mouse model of the metabolic syndrome, because it is accompanied by fatty liver, dyslipidemia and insulin and leptin resistance similar to the metabolic syndrome in humans [35].CB1-knockout mice are also resistant to these associated phenotypes [5,36], which are accordingly corrected by CB1 antagonist treatment of control mice with DIO [37] or of genetically obese mice [38]. The results of recent clinical trials with rimonabant involving obese subjects with the metabolic syndrome suggest a similar CB1 receptor involvement in human obesity and the associated hormonal/metabolic abnormalities. Rimonabant treatment for 1–2 years resulted not only in weight loss, but also in lower plasma triglycerides, increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, reductions in the elevated plasma levels of insulin and leptin and increased plasma adiponectin levels [39-42].

A question of obvious importance is the location of CB1 receptors involved in these obesity-related or diet-induced changes and their reversal by CB1 antagonist treatment. As discussed in more detail below, CB1 receptors and endocannabinoids are present in peripheral tissues involved in hormonal/metabolic control, including adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle and the endocrine pancreas, and there is evidence for the upregulation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) in these tissues in experimental and human obesity [43]. However, central neural mechanisms have been implicated in the control of peripheral energy metabolism and its hormonal regulation [44,45]. The relative contribution of central versus peripheral CB1 receptors in these effects has not only theoretical but also practical implications in terms of selective therapeutic targeting of the receptors involved.

So what type of evidence should one look for before accepting the premise of a dominant role for peripheral CB1 receptors in the development and maintenance of the metabolic syndrome? Evidently, CB1 receptors and their endocannabinoid ligands should be present in peripheral tissues with a major role in energy homeostasis, and selective activation of these receptors, such as can be achieved in isolated tissues or cells, should lead to hormonal/metabolic changes similar to those found in obesity. However, such evidence by itself does not prove that under in vivo conditions, activation of such peripheral CB1 receptors is necessary, let alone sufficient, to produce these phenotypes. More direct evidence to support such a conclusion would be 1) the loss of the CB1 response in mice with tissue/cell-specific knockout of the receptor; and rescue of the response in CB1−/− mice in which CB1 receptors are transgenically expressed in the relevant target tissue only; 2) persistence of the response following disruption of central neural input into target tissue(s); and 3) inhibition of the response by peripherally restricted CB1 receptor antagonists, or a combination of such evidence.

Possible role of peripheral CB1 receptors

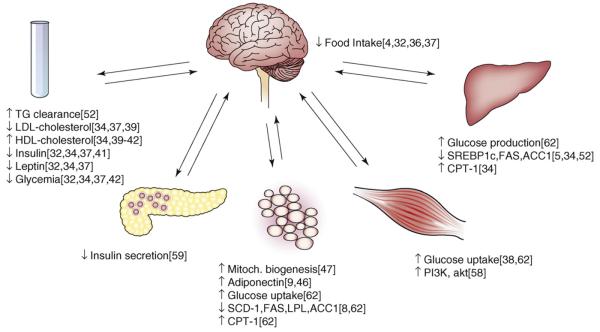

CB1 receptors are expressed in adipocytes (Figure 3) [7,8], where their activation decreases and their blockade increases the expression and release of adiponectin [8,46], an adipokine that promotes energy expenditure by stimulating fatty acid β-oxidation. CB1 blockade was also found to increase mitochondrial biogenesis through increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in mouse white adipocytes [47]. Such effects might account for the increase in total energy expenditure detected by indirect calorimetry in rodents [33,34] or humans treated with a CB1 antagonist [48]. By contrast, increased activity of the endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor system in adipose tissue might contribute to the development of obesity both in genetically obese Zucker rats [49], which express increased levels of CB1 receptors in their adipocytes [8], and in obese individuals, in whom the levels of 2-AG are increased in visceral but not in subcutaneous fat tissue [46]. However, direct evidence that the target of CB1 antagonists or endocannabinoids in such cases is the adipocyte would need to be confirmed by studies using adipocyte-specific CB1-knockout mice.

Figure 3.

Metabolic/hormonal effects of CB1 receptor blockade or ablation mediated at sites in the brain and various peripheral tissues. Numbers next to individual effects are corresponding original reports as listed in References.

The liver is also a potential target of the metabolic actions of endocannabinoids (Figure 3). Both anandamide and 2-AG are present in the liver at levels similar to those in brain, and although the hepatic levels of CB1 receptor mRNA and protein are very low, tissue levels of both CB1 receptors and anandamide are increased in the liver of mice with DIO [4]. The liver is the major site of de novo lipogenesis, and diets high in saturated fats result in increased hepatic lipogenesis [50,51]. This and the reduced expression of the lipogenic transcription factor SREBP1c in the liver of CB1−/− mice suggest the involvement of hepatic endocannabinoids in DIO. Indeed, treatment of intact wild-type mice or isolated hepatocytes with a CB1 agonist increased de novo lipogenesis. Conversely, the increase in hepatic lipogenesis induced by a high-fat diet was reduced by CB1 blockade and was absent in CB1−/− mice, which were resistant to both obesity and hepatic steatosis induced by the high-fat diet [4]. These findings strongly suggest the involvement of hepatic CB1 receptors in the diet-induced increase in de novo lipogenesis, but did not exclude the involvement of additional, extrahepatic CB1 receptors.

Interestingly, CB1−/− mice on a high-fat diet do not develop dyslipidemia and remain insulin and leptin sensitive [5,34,36], suggesting a wider role of the ECS in the metabolic syndrome as a whole. The role of hepatic CB1 receptors in these various endophenotypes was further defined in a recent study through the use of mice with hepatocyte-selective deletion of CB1 receptors (LCB1−/− mice) [34]. When placed on a high-fat diet, LCB1−/− mice became as obese as their wild-type littermates, but had significantly less hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia, and remained insulin and leptin sensitive [34]. These findings suggest that endocannabinoid activation of hepatic CB1 receptors regulates not only hepatic fat metabolism, but also insulin and leptin sensitivity. The absence of hepatic CB1 receptors also prevented the diet-induced increase in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decrease in HDL cholesterol, whereas the hypertriglyceridemia was partially reduced [34]. A recent report indicates that over-activity of the endocannabinoid system induced by blockade of MGL in mice results in a rise in the plasma levels of apoE-depleted triglycerides, due to a CB1 receptor-mediated reduction in triglyceride clearance without a change in triglyceride secretion [52]. The absence of this effect in apoE-deficient mice despite full-blown cannabinoid behavioral effects suggests a peripheral mechanism [52], the location of which remains to be identified.

The two most important tissues responsible for dietinduced insulin resistance are the liver and skeletal muscle [53-55], which means that activation of hepatic CB1 receptors likely results in the production/release of a soluble mediator(s) that is involved in inducing insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Additional communication between the liver and the hypothalamus might also occur in view of the role of hypothalamic mechanisms in dietinduced insulin resistance [55,56]. Soluble mediators might also need to be postulated to account for diet-induced leptin resistance, which involves hypothalamic leptin resistance and a defect in the access of the adipocyte-derived leptin to hypothalamic sites of action [57]. Additional direct effects of CB1 activation on skeletal muscle are likely in view of a recent report that genetic silencing or pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors in skeletal muscle cells leads to increased glucose uptake through a protein-kinase-A-dependent increase in PI3 kinase activity and expression [58].CB1 receptors in pancreatic β-cells might also influence insulin secretion (Figure 3) [59].

In addition to obesity, chronic alcoholism is a major cause of fatty liver, with both obesity and alcohol promoting increased hepatic lipogenesis and decreased elimination of fat from the liver. Interestingly, this parallel extends to the potential involvement of the endocannabinoid system, as indicated by recent findings that mice with either global or hepatocyte-specific deletion of CB1 receptors are protected from alcohol-induced fatty liver [48]. Findings in that study suggest that a paracrine interaction between stellate cell-derived 2-arachidonoylglcerol and CB1 receptors on hepatocytes plays a key role in the development of alcohol-induced steatosis [60]. This implicates, for the first time, the hepatic stellate cell in the control of hepatic lipogenesis. Interestingly, CB1 receptors have been also identified in hepatic stellate cells, where their activation appears to contribute to the development of fibrosis [61], a potential late consequence of both alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver.

Clinical implications

Regardless of the specific mechanisms involved, the findings discussed above suggest that CB1 antagonists with restricted access to sites in the CNS should have efficacy in the treatment of hepatic steatosis of various etiologies, and also in the treatment of dyslipidemias and insulin resistance. This possibility is also supported by a recent report that lipid mobilization in white adipose tissue could be elicited and overall insulin sensitivity increased by systemically, but not by centrally, administered rimonabant in rats with DIO [62]. Such an approach only allows an indirect estimation of the effects of peripheral CB1 blockade, because systemically administered CB1 antagonists will act both in the CNS and periphery, and the centrally mediated reduction in food intake will have secondary effects on metabolism. Although a pair-feeding paradigm has been used in this and many other studies to distinguish between food-intake-dependent and independent effects, the finding of a similar effect of pair feeding and CB1 blockade on a metabolic parameter does not necessarily exclude a possible peripheral mechanism of action. This issue could be more definitively addressed through the use of a peripherally restricted CB1 antagonist. It has been recently reported that LH-21, a neutral CB1 antagonist with limited brain penetration, reduced food intake [63] but did not affect dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis in obese Zucker rats [64]. However, the affinity of this compound for CB1 receptors (Kd: 690 nM [63]) is more than two orders of magnitude lower than the CB1 affinity of rimonabant, making it unlikely that it had any effect on CB1 receptors at the dose of 3 mg/kg used in the above studies. Indeed, LH-21 was recently reported to suppress food intake equally in wild-type and CB1-receptor-knockout mice [65], indicating that this effect was unrelated to CB1 blockade. A clear definition of the contribution of peripheral CB1 receptors to the metabolic effects of CB1 blockade must therefore await the introduction of potent, specific, selective and peripherally restricted CB1 antagonists (see Update). A further requirement for such a compound being considered for human pharmacotherapy is oral bioavailability, an important challenge given that reduced brain penetration achieved by decreasing lipid solubility usually results in a parallel reduction in absorption from the gastrointestinal tract.

Concluding remarks

In summary, peripheral CB1 receptors might represent a novel therapeutic target for certain pathological conditions, including inflammatory/neuropathic pain and various components of the metabolic syndrome. CB1 agonists or antagonists with restricted access to CNS will likely retain therapeutic efficacy in these conditions, but are expected not to cause centrally mediated side effects, such as addictive psychotropic actions in the case of agonists or anxiety and depression in the case of antagonists.

Update

After this manuscript was submitted, an abstract describing orally effective, peripherally restricted CB1 antagonists effective against obesity and related metabolic alterations appeared: McElroy, J. et al. (2008) Non-brain-penetrant CB1 receptor antagonists as novel treatment of obesity and related metabolic disorders. Obesity 16 (Suppl. 1), S47.

Acknowledgements

The work of G.K., D. O-H. and S.B. is supported by intramural funds of the National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- Inflammatory pain

A pain modality initiated by tissue injury that triggers the local infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as mast cells and macrophages that, in turn, release proinflammatory mediators such as histamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes and cytokines. These proinflammatory mediators can directly activate C-fiber nociceptors to cause inflammatory pain, or can sensitize touch-sensitive fibers to result in neuropathic pain or allodynia.

- Metabolic syndrome (syndrome X)

A constellation of medical conditions that predispose an individual to type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Its main features are central or visceral obesity manifesting in increased waist circumference, fasting hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, elevated circulating triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol and elevated blood pressure [35].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited.

References

- 1.Pacher P, et al. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, et al. Multiple pathways involved in the biosynthesis of anandamide. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kathuria S, et al. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Marzo V, et al. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature. 2001;410:822–825. doi: 10.1038/35071088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osei-Hyiaman D, et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1298–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engeli S, et al. Activation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:2838–2843. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg BA, Cannon CP. Cannabinoid-1 receptor blockade in cardiometabolic risk reduction: safety, tolerability, and therapeutic potential. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007;100(12A):27P–32P. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cota D, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:423–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI17725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensaid M, et al. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 increases Acrp30 mRNA expression in adipose tissue of obese fa/fa rats and in cultured adipocyte cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:908–914. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.4.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagotto U, et al. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr. Rev. 2006;27:73–100. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Marzo V. The endocannabinoid system in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1356–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiley JL, Martin BR. Cannabinoid pharmacological properties common to other centrally acting drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;471:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: a therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:319–334. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maione S, et al. Elevation of endocannabinoid levels in the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey through inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase affects descending nociceptive pathways via both cannabinoid receptor type 1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;316:969–982. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staton PC, et al. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 plays a role in mechanical hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;139:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin WJ, et al. Cannabinoid receptor-mediated inhibition of the rat tail-flick reflex after microinjection into the rostral ventromedial medulla. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;242:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohmann AG, Herkenham M. Localization of central cannabinoid CB1 receptor messenger RNA in neuronal subpopulations of rat dorsal root ganglia: a double-label in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 1999;90:923–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohmann AG, Herkenham M. Cannabinoid receptors undergo axonal flow in sensory nerves. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1171–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amaya F, et al. Induction of CB1 cannabinoid receptor by inflammation in primary afferent neurons facilitates antihyperalgesic effect of peripheral CB1 agonist. Pain. 2006;124:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez T, et al. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors suppresses the maintenance of inflammatory nociception: a comparative analysis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;150:153–163. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly S, et al. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid CB1 receptors inhibits mechanically evoked responses of spinal neurons in noninflammed rats and rats with hindpaw inflammation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:2239–2243. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johanek LM, Simone DA. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid receptors attenuates cutaneous hyperalgesia produced by a heat injury. Pain. 2004;109:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calignano A, et al. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature. 1998;394:277–281. doi: 10.1038/28393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal N, et al. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrosino S, et al. Changes in spinal and supraspinal endocannabinoid levels in neuropathic rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledent C, et al. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmer A, et al. Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dziadulewicz EK, et al. Naphthalen-1-yl-(4-pentyloxynaphthalen-1-yl)methanone: a potent, orally bioavailable human CB1/CB2 dual agonist with antihyperalgesic properties and restricted central nervous system penetration. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:3851–3856. doi: 10.1021/jm070317a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurmikko TJ, et al. Sativex successfully treats neuropathic pain characterised by allodynia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2007;133:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg I, et al. Effects of marihuana use on body weight and caloric intake in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1976;49:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00427475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombo G, et al. Appetite suppression and weight loss after the cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716. Life Sci. 1998;63:PL113–PL117. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravinet Trillou C, et al. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003;284:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00545.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herling AW, et al. CB1 receptor antagonist AVE1625 affects primarily metabolic parameters independently of reduced food intake in Wistar rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293:E826–E832. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00264.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osei-Hyiaman D, et al. Hepatic CB(1) receptor is required for development of diet-induced steatosis, dyslipidemia, and insulin and leptin resistance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3160–3169. doi: 10.1172/JCI34827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravinet Trillou C, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2004;28:640–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poirier B, et al. The anti-obesity effect of rimonabant is associated with an improved serum lipid profile. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2005;7:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YL, et al. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 on oxygen consumption and soleus muscle glucose uptake in Lep(ob)/Lep(ob) mice. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2005;29:183–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Gaal LF, et al. Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pi-Sunyer FX, et al. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006;295:761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Despres JP, et al. Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2121–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheen AJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of rimonabant in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2006;368:1660–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellocchio L, et al. The endocannabinoid system and energy metabolism. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:850–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obici S, Rossetti L. Minireview: nutrient sensing and the regulation of insulin action and energy balance. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5172–5178. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buettner C, et al. Leptin controls adipose tissue lipogenesis via central, STAT3-independent mechanisms. Nat. Med. 2008;14:667–675. doi: 10.1038/nm1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matias I, et al. Regulation, function, and dysregulation of endocannabinoids in models of adipose and beta-pancreatic cells and in obesity and hyperglycemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:3171–3180. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tedesco L, et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade promotes mitochondrial biogenesis through endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in white adipocytes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2028–2036. doi: 10.2337/db07-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Addy C, et al. The acyclic CB1R inverse agonist taranabant mediates weight loss by increasing energy expenditure and decreasing caloric intake. Cell Metab. 2008;7:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gary-Bobo M, et al. Rimonabant reduces obesity-associated hepatic steatosis and features of metabolic syndrome in obese Zucker fa/fa rats. Hepatology. 2007;46:122–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.21641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sampath H, et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 mediates the prolipogenic effects of dietary saturated fat. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2483–2493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin J, et al. Hyperlipidemic effects of dietary saturated fats mediated through PGC-1beta coactivation of SREBP. Cell. 2005;120:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruby MA, et al. Overactive endocannabinoid signaling impairs apolipoprotein E-mediated clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:14561–14566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807232105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, et al. Overfeeding rapidly induces leptin and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2001;50:2786–2791. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kraegen EW, et al. Development of muscle insulin resistance after liver insulin resistance in high-fat-fed rats. Diabetes. 1991;40:1397–1403. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.11.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ono H, et al. Activation of hypothalamic S6 kinase mediates diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2959–2968. doi: 10.1172/JCI34277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cota D, et al. The role of hypothalamic mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling in diet-induced obesity. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7202–7208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1389-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El-Haschimi K, et al. Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1827–1832. doi: 10.1172/JCI9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Esposito I, et al. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist Rimonabant stimulates 2-deoxyglucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells by regulating phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1678–1686. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakata M, Yada T. Cannabinoids inhibit insulin secretion and cytosolic Ca(2+) oscillation in islet beta-cells via CB1 receptors. Regul. Pept. 2008;145:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeong WI, et al. Paracrine activation of hepatic CB1 receptors by stellate cell-derived endocannabinoids mediates alcoholic fatty liver. Cell Metab. 2008;7:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teixeira-Clerc F, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonism: a new strategy for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2006;12:671–676. doi: 10.1038/nm1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nogueiras R, et al. Peripheral, but not central. CB1 antagonism provides food intake independent metabolic benefits in diet-induced obese rats. Diabetes. 2008;59:2977–2991. doi: 10.2337/db08-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pavon FJ, et al. Antiobesity effects of the novel in vivo neutral cannabinoid receptor antagonist 5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-3-hexyl-1H-1,2,4-triazole–LH 21. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pavon FJ, et al. Central versus peripheral antagonism of cannabinoid CB1 receptor in obesity: effects of LH-21, a peripherally acting neutral cannabinoid receptor antagonist, in Zucker rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(Suppl 1):116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen RZ, et al. Pharmacological evaluation of LH-21, a newly discovered molecule that binds to cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;584:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]