Abstract

The DNA-templated polymerization of synthetic building blocks provides a potential route to the laboratory evolution of sequence-defined polymers with structures and properties not necessarily limited to those of natural biopolymers. We previously reported the efficient and sequence-specific DNA-templated polymerization of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) aldehydes. Here, we report the enzyme-free, DNA-templated polymerization of side-chain-functionalized PNA tetramer and pentamer aldehydes. We observed that the polymerization of tetramer and pentamer PNA building blocks with a single lysine-based side chain at various positions in the building block could proceed efficiently and sequence-specifically. In addition, DNA-templated polymerization also proceeded efficiently and in a sequence-specific manner with pentamer PNA aldehydes containing two or three lysine side chains in a single building block to generate more densely functionalized polymers.

To further our understanding of side-chain compatibility and expand the capabilities of this system, we also examined the polymerization efficiencies of 20 pentamer building blocks each containing one of five different side-chain groups and four different side-chain regio- and stereochemistries. Polymerization reactions were efficient for all five different side-chain groups and for three of the four combinations of side-chain regio- and stereochemistries. Differences in the efficiency and initial rate of polymerization correlate with the apparent melting temperature of each building block, which is dependent on side-chain regio- and stereochemistry, but relatively insensitive to side-chain structure among the substrates tested. Our findings represent a significant step towards the evolution of sequence-defined synthetic polymers and also demonstrate that enzyme-free nucleic acid-templated polymerization can occur efficiently using substrates with a wide range of side-chain structures, functionalization positions within each building block, and functionalization densities.

Introduction

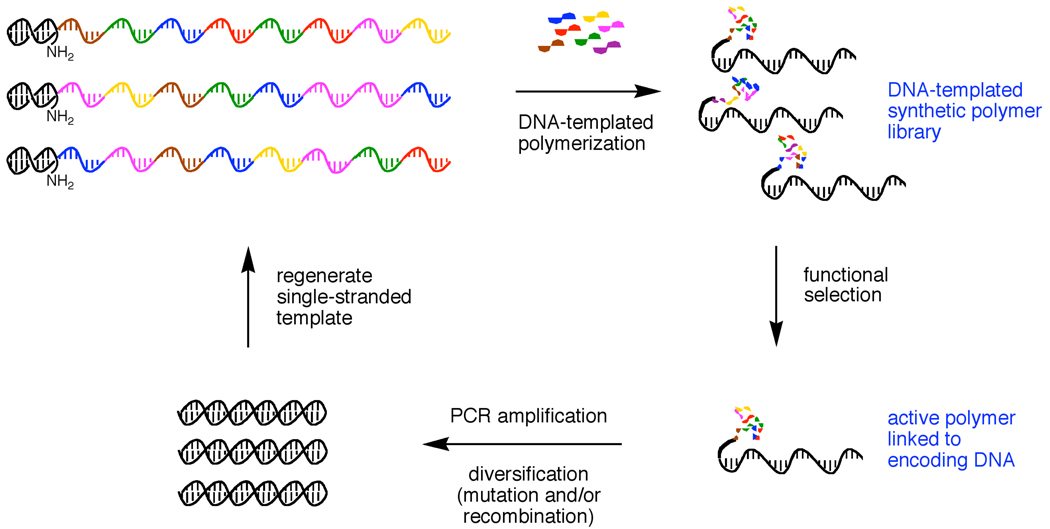

The nucleic acid-templated polymerizations of DNA, RNA, and proteins1–3 are essential components of all known living systems. Template-directed polymerization mediates the translation of genetic information into functional macromolecules and ultimately enables the evolution of biopolymers. Over the past few decades, several researchers have explored the use of nucleic acid-templated polymerization reactions in the absence of enzymes to generate sequence-defined synthetic oligomers and polymers without the structural constraints imposed by the biosynthetic machinery.4–16 The DNA- or RNA-templated polymerization of synthetic building blocks raises the possibility of performing test tube evolution on synthetic polymers towards desired functional properties through iterated cycles of translation (polymerization), selection, amplification, and mutation (as an example, see Figure 1).17

Figure 1.

Example of a simplified scheme for the evolution of synthetic polymers using DNA-templated polymerization. (Note that the functional selection of a DNA-templated polymer will additionally require displacement of the polymer from its DNA template to allow the polymer to fold).

Building on the findings of Orgel, Lynn, and their respective coworkers,5,12,14 we previously developed the efficient and sequence-specific DNA-templated polymerization of unfunctionalized peptide nucleic acid (PNA) aldehydes using reductive amination coupling reactions.18 In contrast to the 2-methylimidazole-activated phosphate-coupling chemistry pioneered by Orgel and further developed by other researchers,10,19,20 this system relies on typically more efficient DNA-templated reductive amination reactions first reported by Lynn and coworkers.12 We considered PNA-based structures ideal initial targets for the nucleic acid-templated polymerization of non-natural polymers because of their ability to bind DNA sequence-specifically,21 their synthetic accessibility, and their ability to display side-chain functional groups that can be derived from corresponding (D)- or (L)-amino acids.22,23 Although functionalized PNA oligomers containing side-chain modifications have been shown to hybridize to DNA,22–25 the nucleic acid-templated polymerization of side-chain-containing building blocks has not been previously reported despite the potential of functionalized synthetic polymers to possess properties not available to their non-functionalized counterparts.26

In this work we examined the DNA-templated polymerization of PNA aldehyde tetramer or pentamer building blocks bearing one or multiple side chains at various positions within the building block. We observed efficient and sequence-specific polymerization for building blocks functionalized at any of the nucleotide positions tested (all but the final position bearing the aldehyde group), as well as for multiply functionalized substrates containing up to three lysine side chains. We also evaluated the DNA-templated polymerization behavior of 20 different PNA aldehyde pentamer building blocks containing all possible combinations of five side-chain groups and four side-chain regio- and stereochemistries. Our results show that three of the four combinations of regio- and stereochemistry support efficient and sequence-specific DNA-templated polymerization, laying the foundation for the use of functionalized PNA-based building blocks in future templated polymerization-based synthetic polymer evolution efforts. These findings also demonstrate that the non-enzymatic nucleic acid-templated synthesis of polymers with non-nucleic acid backbones can support a diverse collection of side-chain structures, attachment points, stereochemistries, and densities— features of possible relevance to prebiotic chemistry.

Results and Discussion

DNA-Templated Polymerizations of Functionalized PNA Tetramer Building Blocks

We previously reported the DNA-templated polymerization of the unfunctionalized NH2-gvvt-CHO set of PNA aldehyde tetramers (lower case indicates PNA, v = a, c, or g).18 Based on these findings, we examined the DNA-templated polymerization of side-chain-functionalized PNA aldehyde tetramer building blocks. Recent reports have demonstrated that γ-substituted PNA thymine monomers based on (L)-lysine can be readily synthesized and incorporated into PNA oligomers without impairing DNA hybridization.24 The γ-substituted (L)-lysine thymine monomer (t*) was synthesized following literature precedent,24 and incorporated at the third position of a tetramer PNA aldehyde H2N-ggt*t-CHO using Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis on threonine-linked resin as we described previously.18 In addition, the non-functionalized PNA tetramer building block H2N-ggtt-CHO was synthesized for comparison purposes (Table S1). Although this tetramer was not present in the gvvt set,18 our sequence choice was motivated by the synthetic accessibility of the functionalized thymine monomer and the necessity for thymine at the terminal (aldehyde) position.

We also constructed a functionalized tetramer aldehyde from the H2N-gvvt-CHO set by synthesizing a γ-substituted (L)-lysine-based guanine PNA monomer. We coupled glycine allyl ester with Fmoc-lysinal to form the γ-substituted PNA backbone (Scheme 1). N-benzhydryloxycarbonyl (Bhoc)-protected guanine-9-acetic acid was prepared using the method of Debaene and Winssinger27 and acylation with the γ-substituted PNA backbone using BOP reagent followed by ester deprotection provided the Fmoc-protected lysine-functionalized PNA guanine monomer acid. The γ-(L)-lysine-functionalized guanine monomer (g*) was then used to synthesize PNA aldehyde H2N-ggg*t-CHO (Table S1).18 We previously showed that the unfunctionalized H2N-gggt-CHO building block undergoes efficient and sequence-specific DNA-templated polymerization.18

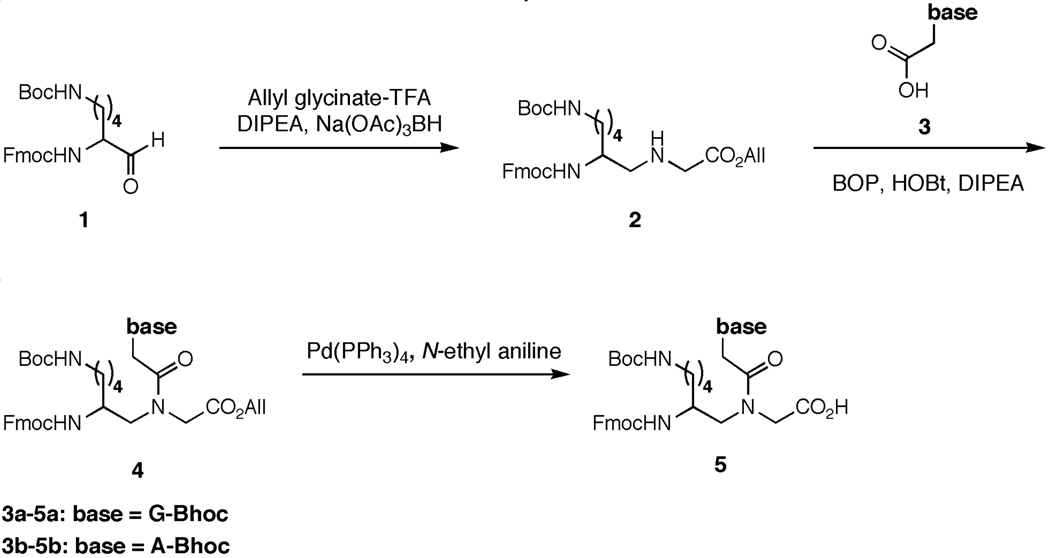

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of γ-functionalized adenine and guanine PNA monomers. Route adapted from Englund et al.24 and Thomson et al.45

We prepared DNA templates containing a 5’-amine-terminated hairpin followed by ten successive repeats of the four-base DNA codon complementary to both sets of tetramer building blocks (5’-AACC-3’ for H2N-ggtt-CHO and H2N-ggt*t-CHO; 5’-ACCC-3’ for H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO) (Figure S1a). To evaluate the basic sequence specificity of DNA-templated polymerization reactions, we also synthesized mismatched DNA templates in which five repeats of the appropriate matched codon were followed by five repeats of a mismatched codon (5’-ACAC-3’ for H2N-ggtt-CHO and H2N-ggt*t-CHO; 5’-CACA-3’ for H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO) (Figure S1a). If polymerization proceeds sequence-specifically through a DNA-templated mechanism, as opposed to a non-templated, intermolecular mechanism, truncated products ending after five reductive amination couplings should predominantly result from the use of this mismatched template.

Polymerization reactions for the functionalized and unfunctionalized tetramer PNA aldehyde building blocks were performed for 30 min at a reaction temperature that balanced coupling efficiency and sequence specificity (40°C for H2N-ggtt-CHO and H2N-ggt*t-CHO; 50°C for H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO), and quenched by addition of excess allylamine. Denaturing PAGE analysis was used to determine the extent of polymerization for each PNA aldehyde tetramer (Figure S1a, S1b). The unfunctionalized H2N-ggtt-CHO building block polymerized efficiently, affording full-length product in 82% yield (Figure S1a, S1b). Gratifyingly, the (L)-lysine-functionalized H2N-ggt*t-CHO tetramer participated in DNA-templated polymerization with comparable efficiency, providing full-length product in 90% yield (Figure S1a, S1b). Both the functionalized and unfunctionalized building block gave predominantly truncated product when reacted with the mismatched template (Figure S1a). The polymerization of the H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO tetramer building blocks also proceeded in a highly efficient manner, both affording > 80% full-length 40-mer PNA product (Figure S1b) and generating predominantly truncated product when a mismatched template was used (Figure S1a). These results demonstrate the ability of the DNA-templated polymerization of tetramer PNA aldehydes to support side-chain functionalized substrates without compromising polymerization efficiency and basic sequence specificity.

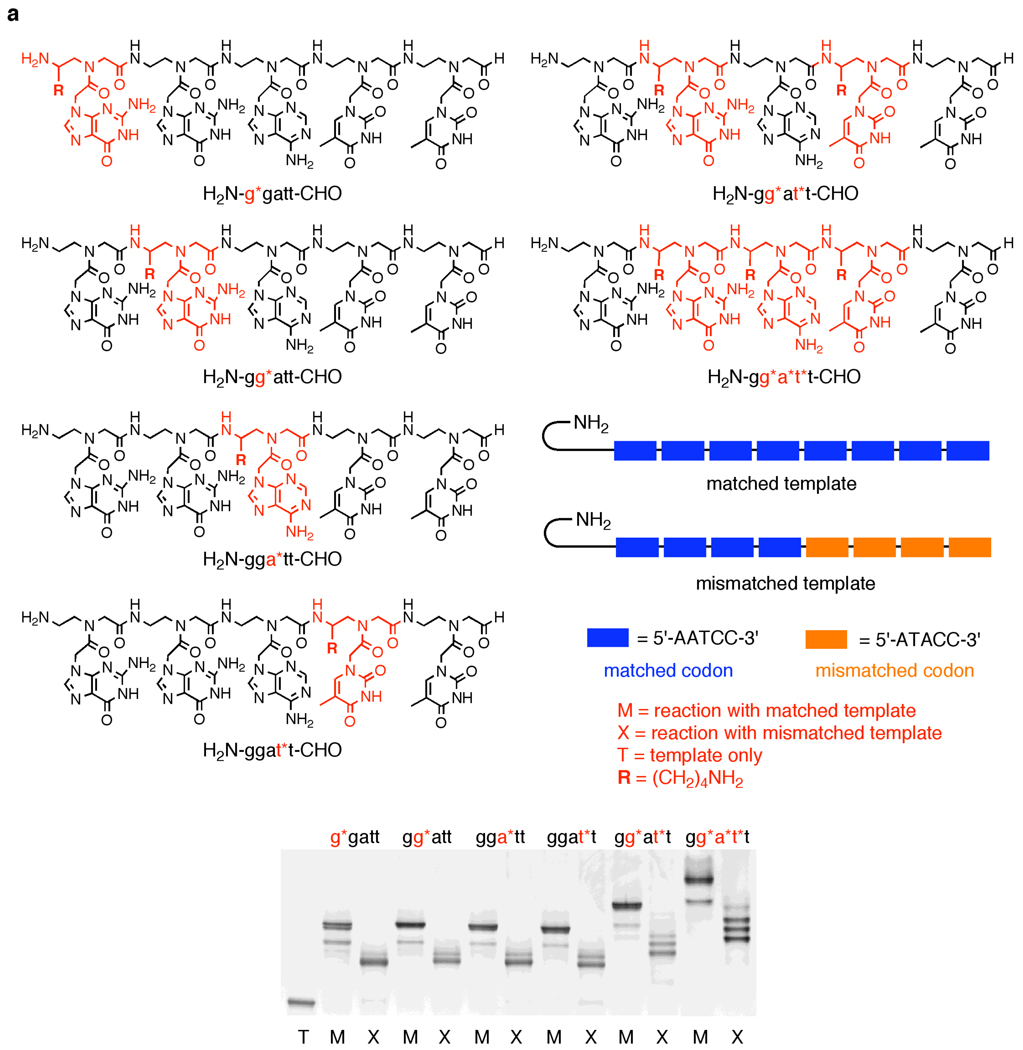

PNA Pentamer Building Blocks Containing Lysine Side Chains at Different Positions

To expand the number of viable codons with uniform purine content, and therefore uniform template melting temperatures28 in a future PNA selection system involving side-chain-functionalized building blocks, and to mitigate the effect of a more diverse set of potentially destabilizing side-chain modifications, we turned to pentamer PNA aldehydes that offer larger codon diversity and greater potential affinities to DNA templates. We focused our studies on the PNA pentamer aldehyde H2N-ggatt-CHO. A γ-substituted (L)-lysine-based PNA adenine monomer (a*) was prepared similarly to the g* monomer (Scheme 1). To study the effect of functionalized monomer position on polymerization, g*, a*, and t* γ-(L)-lysine based monomers were incorporated at the first, second, third and fourth positions of the H2N-ggatt-CHO building block, resulting in H2N-g*gatt-CHO, H2N-gg*att-CHO, H2N-gga*tt-CHO, and H2N-ggat*t-CHO pentamer PNA aldehydes (Figure 3a, Table S1). The terminal, aldehyde-bearing position was not as readily available for functionalization since its synthesis involves allylamine,18 which is incompatible with the Fmoc-protected amino aldehydes used to make the functionalized PNA backbone (data not shown). We also combined functionalized γ-(L)-lysine based monomers in a single building block to create the multiply functionalized H2N-gg*at*t-CHO, H2N-gg*a*t*t-CHO and H2N-g*g*a*t*t-CHO pentamer aldehydes (Figure 3a, Table S1) containing two, three, or four side-chain modifications respectively.

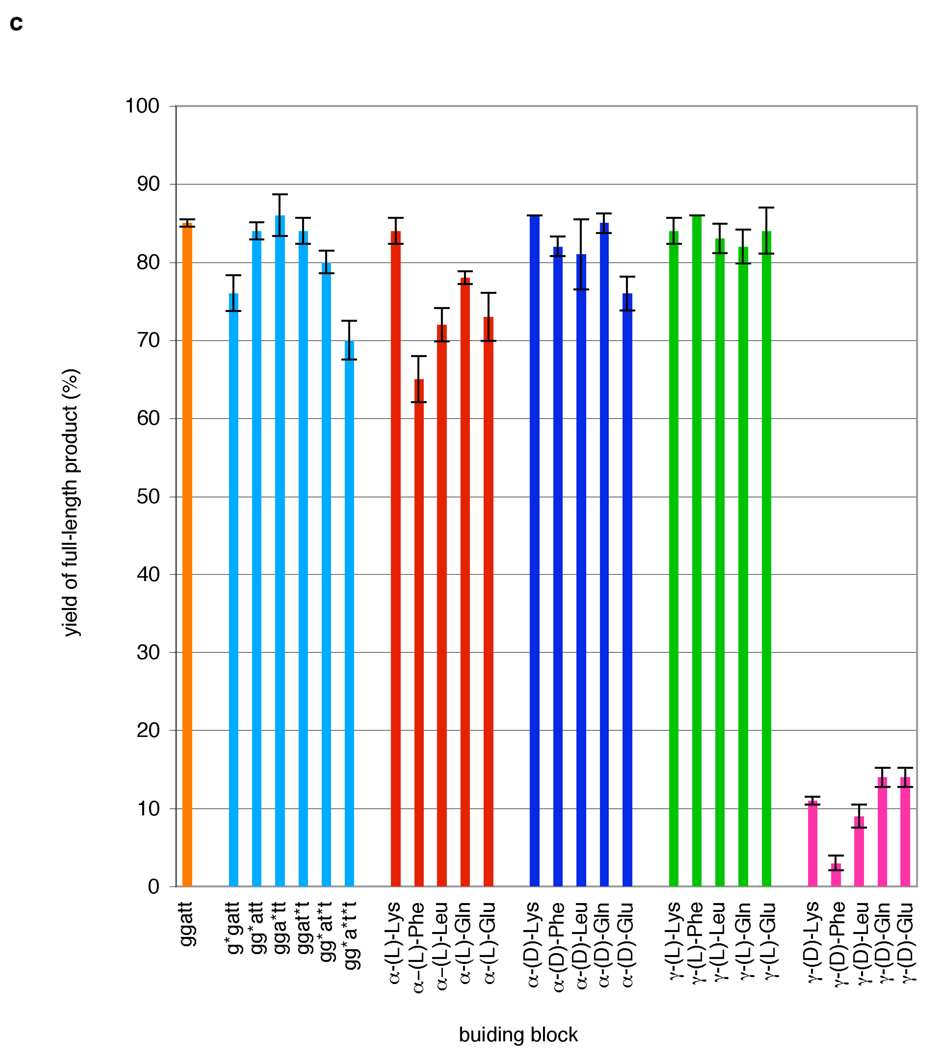

Figure 3.

(a) Polymerization of functionalized H2N-ggatt-CHO PNA pentamer aldehydes containing one or more γ-(L)-lysine side chains at various nucleotide positions in the presence of matched and mismatched DNA templates. Reactions were performed for 30 minutes at 50°C (for singly functionalized building blocks), 55°C (for H2N-gg*at*t-CHO) or 60°C (for H2N-gg*a*t*t-CHO) in 10 mM TAPS pH 8.5 with 100 mM NaCl, using 0.4 µM DNA template and 12.8 µM of the indicated PNA pentamer aldehyde and then quenched with excess allyl amine. Prior to the addition of NaBH3CN, reactions were pre-equilibrated to the reaction temperature as described in Figure 2. (b) Polymerization of side-chain functionalized H2N-ggat*t-CHO PNA pentamer aldehydes in the presence of matched and mismatched DNA templates. Reactions were performed as in Figure 3a. Reactions with the unfunctionalized and both α-functionalized building blocks were performed at 40 °C. Reactions with γ-(L) functionalized building blocks were performed at 50 °C and reactions with γ-(D) functionalized building blocks were performed at 40 °C; temperatures were chosen to optimize efficiency and sequence specificity. (c) Comparison of polymerization efficiencies of functionalized PNA pentamer aldehydes. Product yield was determined by gel densitometry using denaturing PAGE. Values represent the average and standard deviation of three independent reactions.

We prepared DNA templates containing a 5’-amine-terminated hairpin followed by eight successive repeats of the five-base DNA codon 5’-AATCC-3’ complementary to the pentamer PNA building blocks described above (Figure 2). Full-length polymerization products therefore contain 40 PNA nucleotides arising from eight consecutive reductive amination coupling reactions. To evaluate the basic sequence specificity of DNA-templated polymerization reactions, we also synthesized mismatched DNA templates in which four repeats of 5’-AATCC-3’ were followed by four repeats of the mismatched codon 5’-ATACC-3’ (Figure 3a). Sequence-specific polymerization using this mismatched template should result in predominantly truncated products ending after four reductive amination couplings.

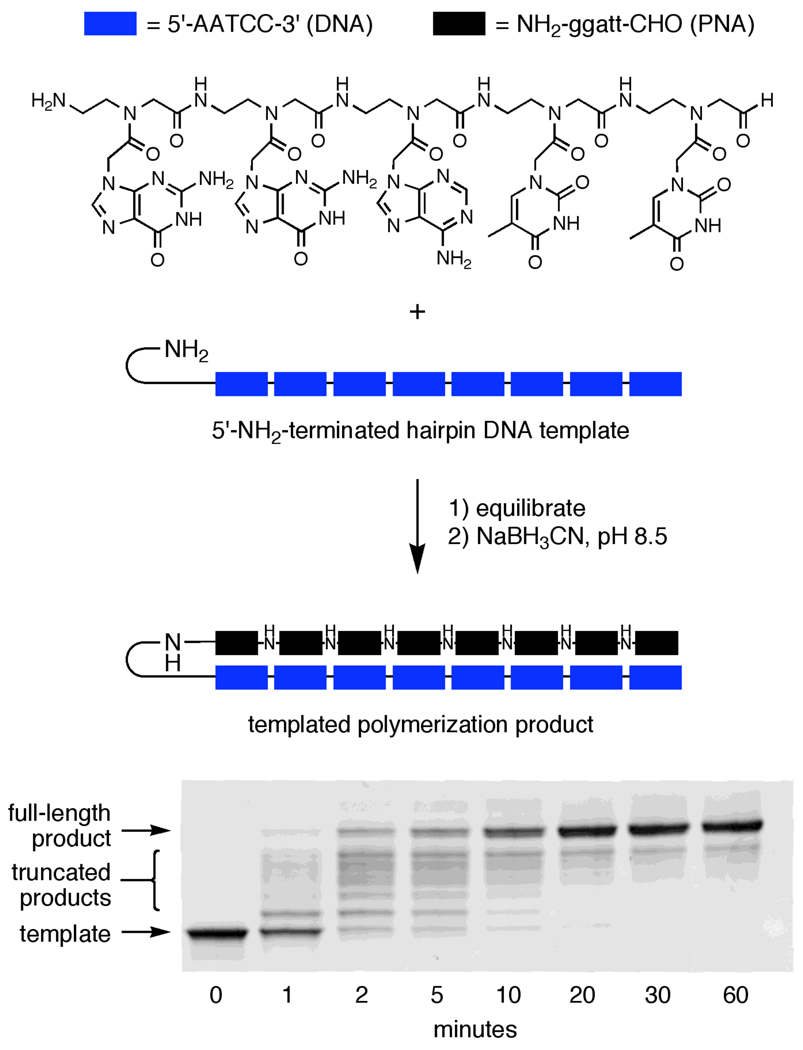

Figure 2.

DNA-templated polymerization of unfunctionalized PNA pentamer aldehydes. Reactions were performed at 40 °C in 10 mM TAPS pH 8.5 with 100 mM NaCl, using 0.4 µM DNA template and 12.8 µM (four equivalents per template codon) of PNA pentamer aldehyde NH2-ggatt-CHO. Prior to the addition of NaBH3CN, reactions were pre-equilibrated to 40 °C by heating to 95 °C for 10 minutes and slowly cooling to 40 °C over 15 minutes. After the indicated times, the reactions were quenched with excess allyl amine and subjected to gel filtration and denaturing PAGE analysis (bottom).

DNA-Templated Polymerizations of Lysine-Containing PNA Pentamer Building Blocks

Polymerization reactions contained 0.4 µM DNA template and 12.8 µM PNA building block (4 equiv per template codon) in aqueous pH 8.5 buffer. This reaction stoichiometry was determined empirically so as to balance coupling efficiency and sequence specificity based upon our previous studies with PNA tetramer aldehydes18 as well as polymerization experiments with the unfunctionalized H2N-ggatt-CHO pentamer aldehyde (Figure S2). A solution containing DNA template and PNA aldehyde was equilibrated at the reaction temperature (60°C for H2N-gg*a*t*t-CHO; 55°C for H2N-gg*at*t-CHO; 50°C for all other building blocks containing γ-(L)-side chains, chosen empirically to balance coupling efficiency and sequence specificity) before 80 mM NaBH3CN was added to initiate reductive amination. After 30 min at the reaction temperature, the reactions were quenched by addition of excess allylamine. Denaturing PAGE analysis was used to determine the extent of polymerization for each PNA aldehyde pentamer (Figure 3a, Figure 3b, and Figure 3c).

Consistent with our previous studies using PNA aldehyde tetramers,18 the unfunctionalized H2N-ggatt-CHO pentamer polymerized efficiently in a DNA-templated format (Figure 2), resulting in 85% yield of full-length 40-mer product (confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry) resulting from eight consecutive coupling reactions (Figure 3c and Supporting Information, Table S2). In contrast, predominantly truncated product corresponding to four templated coupling reactions without additional non-templated couplings resulted from polymerization reactions conducted under the same conditions but using the mismatched template (Figure 3b). These results demonstrate the efficiency and basic sequence specificity of the DNA-templated unfunctionalized PNA pentamer polymerization system.

Next we evaluated the polymerization efficiency and sequence specificity of the H2N-g*gatt-CHO, H2N-gg*att-CHO, H2N-gga*tt-CHO, and H2N-ggat*t-CHO PNA building blocks (Figure 3a) containing γ-(L)-lysine side chains. The singly-functionalized substrates all polymerized efficiently on DNA templates, providing full-length products in 76–86% yield (Figure 3c), similar to that of the unfunctionalized substrate. The position of the functionalized monomer within the building block did not affect polymerization efficiency, with the exception of the H2N-g*gatt-CHO building block, which showed a slight reduction (∼10%) in polymerization efficiency compared with the unmodified H2N-ggatt-CHO building block (Figure 3c), possibly due to the proximity of the functionalized monomer to the reacting amine group. All of the singly-functionalized building blocks exhibited excellent sequence specificity when polymerized using the mismatched template (Figure 3a).

The ability of the DNA-templated polymerization to tolerate side chains at four different nucleotide positions within the building block raises the possibility that more densely functionalized polymers could be generated using the H2N-gg*at*t-CHO, H2N-gg*a*t*t-CHO, and H2N-g*g*a*t*t-CHO substrates. Indeed, the doubly and triply functionalized H2N-gg*at*t-CHO and H2N-gg*a*t*t-CHO building blocks both polymerized efficiently, affording full-length product (confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry) in 80% and 70% yield, respectively, and generating predominantly truncated products in the presence of the mismatched template (Figure 3a, 3c and Supporting Information, Table S2). These results show that the position of the functionalized monomer has little effect on the polymerization efficiency, and demonstrate the system’s ability to polymerize highly-functionalized building blocks. Although we were able to observe complete consumption of the DNA template in the polymerization reaction of the quadruply functionalized H2N-g*g*a*t*t-CHO building block, we did not observe a well-defined product species by PAGE analysis. We speculate that the combination of the highly-positively charged H2N-g*g*a*t*t-CHO building block containing four lysine side chains and the negatively-charged DNA template result in polymerization product with modest net charge and therefore poor electrophoretic mobility.

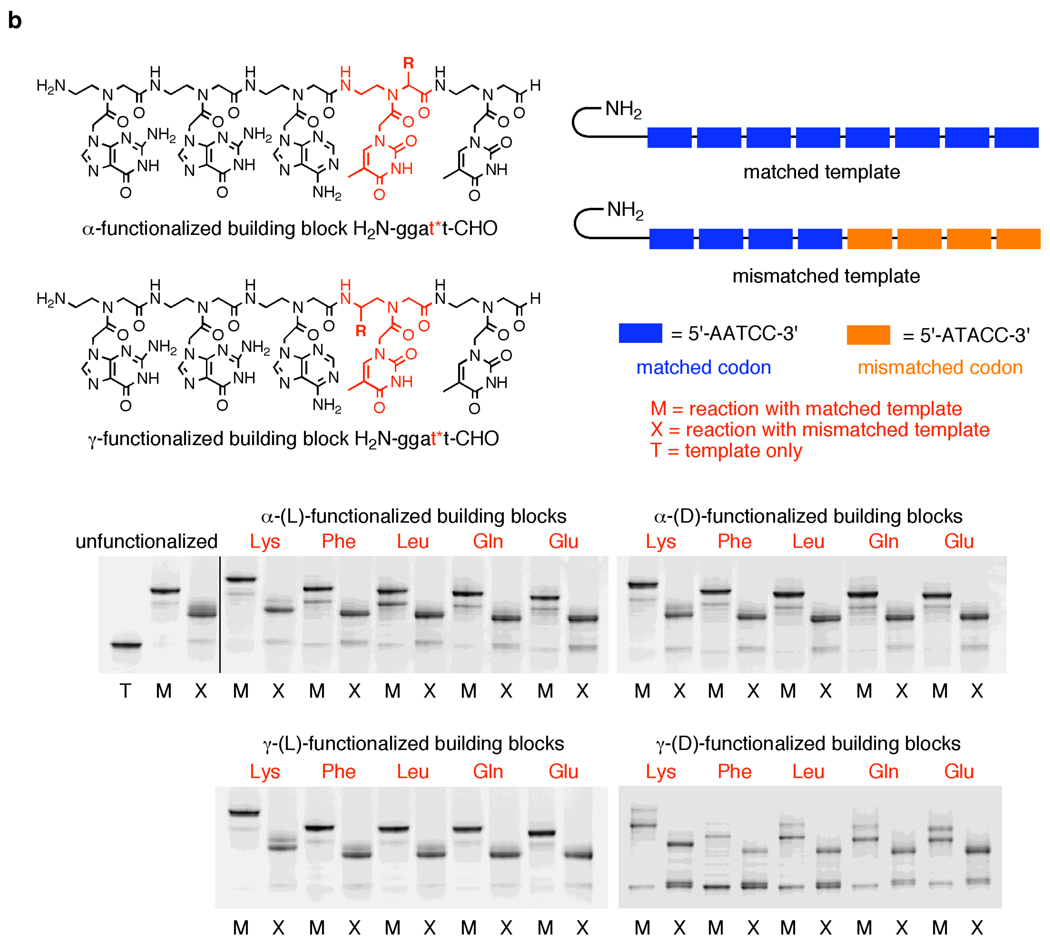

PNA Building Blocks Containing 20 Combinations of Side Chain Structure, Stereochemistry, and Regiochemistry

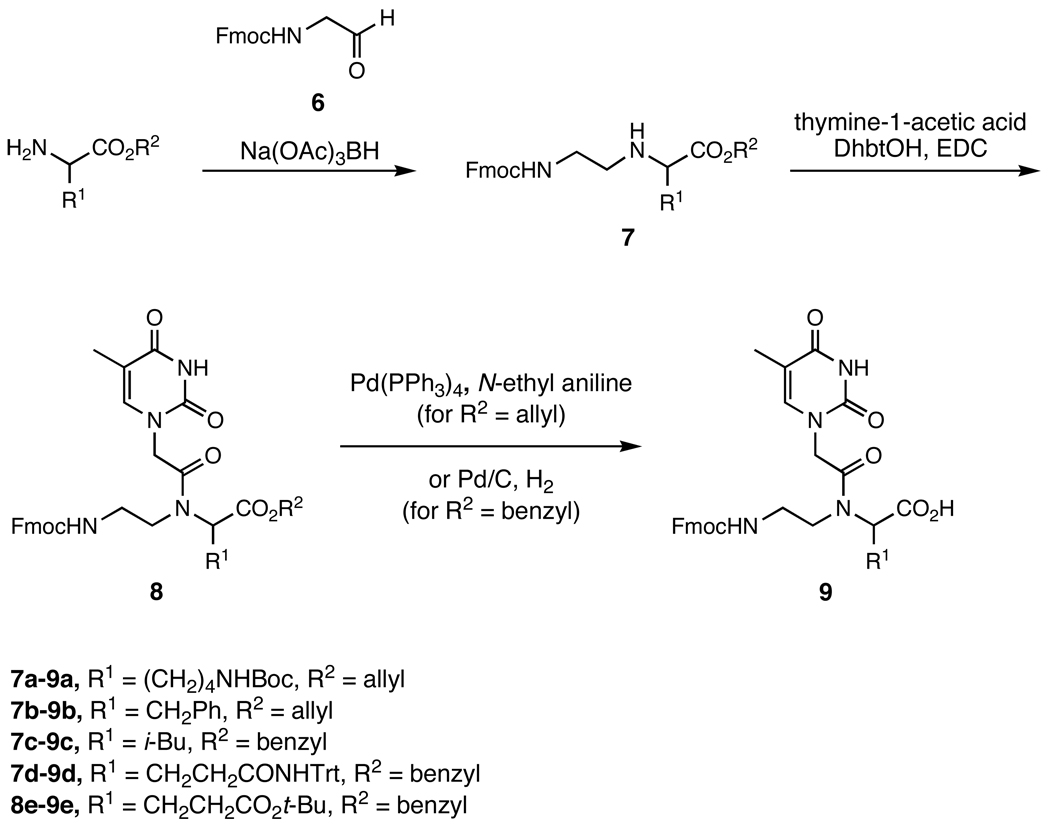

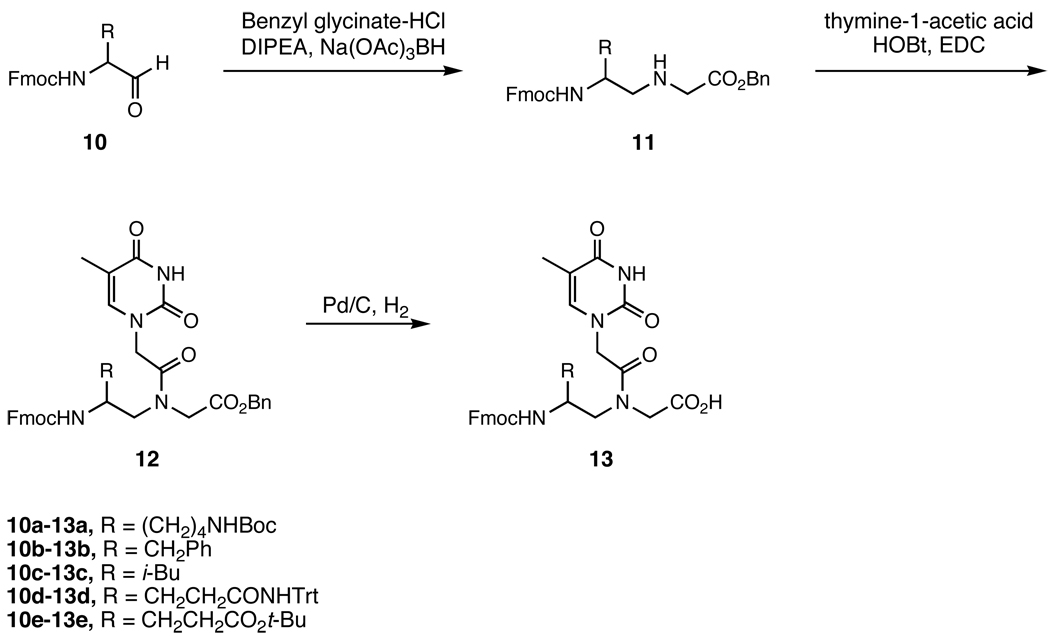

We also examined the compatibility of DNA-templated polymerization with functionalized building blocks bearing side chains of different structure, regiochemistry, and stereochemistry. The achiral PNA backbone can be functionalized at the α- or γ-carbons using one of two side-chain stereochemistries at each position. The effect of side-chain groups on the melting temperature (Tm) of PNA oligomers is known to be dependent on the nature of the modification and on its regio- and stereochemistry.22–25,29 To elucidate the effect of side-chain identity and position on DNA-templated polymerization, thymine-containing PNA mononucleotides containing all four combinations of side-chain attachment point (α or γ) and stereochemistry ((D) or (L)) were synthesized from (D)- or (L)-lysine, phenylalanine, leucine, glutamine, and glutamate in accordance with literature precedent.22,24 The α-modified backbones were prepared by coupling Fmoc-glycinal with the appropriate benzyl or allyl esterprotected amino acid (Scheme 2), while the γ-modified backbones were made by coupling the appropriate Fmoc-protected amino aldehyde with glycine benzyl ester (Scheme 3). Acylation with 1-thymine acetic acid followed by ester deprotection provided the Fmoc-protected functionalized PNA monomer acids. In total, we synthesized all 20 functionalized PNA thymine mononucleotides encompassing aliphatic, aromatic, polar, anionic, and cationic side-chain groups combined with both possible side-chain regiochemistries and both possible side-chain stereochemistries.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of α-functionalized PNA monomers. Route adapted from Haaima et al.22 and Englund et al.24

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of γ-functionalized PNA monomers. Route adapted from Englund et al.24

Each functionalized thymine PNA monomer (t*) was incorporated at the fourth position of a pentamer PNA aldehyde H2N-ggat*t-CHO. We chose to incorporate diverse side-chain-modifications at this position due to the synthetic accessibility of functionalized thymine PNA monomers.

DNA-Templated Polymerization of PNA Building Blocks Containing Diverse Side Chains

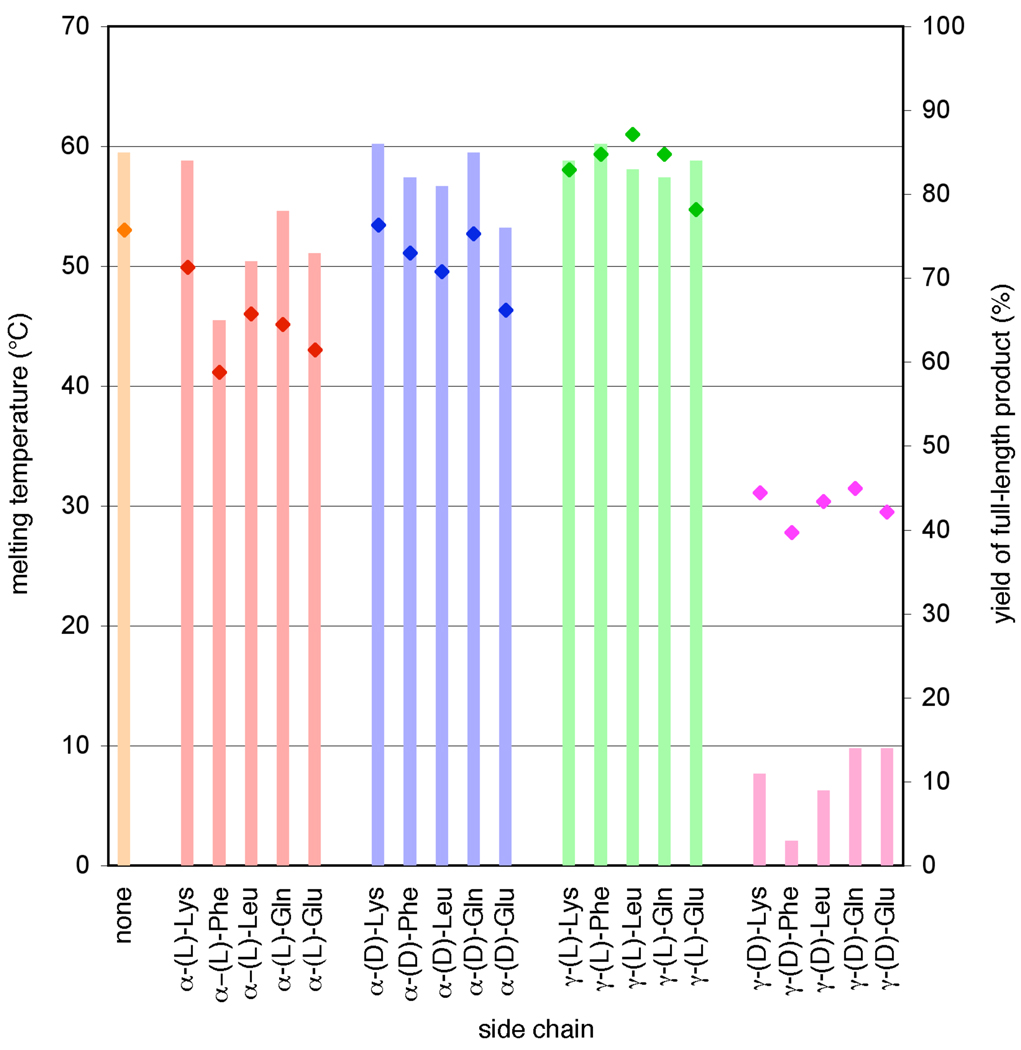

We examined the DNA-templated polymerization efficiency and sequence specificity of the H2N-ggat*t-CHO PNA building blocks (Figure 3b) containing the 20 side chains at the t* position using the approach described above. To balance coupling efficiency and sequence specificity, reactions with building blocks containing γ-(L)-side chains were performed at 50°C. Reactions with all other pentamer building blocks were performed at 40°C. The substrates bearing side chains at the α-position polymerized efficiently on DNA templates, providing full-length products in 66–86% yield (Figure 3c), similar to that of the unfunctionalized substrate. Side-chain composition did not significantly influence yields of full-length product for a given side-chain regio- and stereochemistry, although the lysine-based building blocks consistently afforded slightly higher amounts of full-length product. While both (L)- and (D)- side-chain stereochemistries allowed for efficient polymerization, α-(D) building blocks produced full-length product yields that were, on average, 7% higher than those observed from their enantiomers. Both α-(L) and α-(D) building blocks generated predominantly truncated product in the presence of a mismatched template (Figure 3b), exhibiting comparable sequence specificity to that of the non-functionalized substrate.

In contrast to the efficient polymerization observed with both enantiomers of all five α-functionalized building blocks, the DNA-templated polymerization of PNA aldehydes functionalized at the γ-position (Figure 3b), under the above conditions, was highly dependent on side-chain stereochemistry. Building blocks containing γ-(L) side chains were very efficient substrates for templated polymerization and generated full-length products in 84% average yield (Figure 3c), the highest of the four types of side chains described in this work. The enantiomeric γ-(D) PNA aldehydes, however, were very poor polymerization substrates, affording full-length products in only 3–14% yield (Figure 3c). We also performed the polymerization of γ-(D)-functionalized building blocks at 25 °C instead of 40 °C, and while product yields improved (20–50%, data not shown), they remained significantly lower than those of the other functionalized building blocks studied here.

Unlike the dramatic effect of stereochemistry on the polymerization of γ-functionalized building blocks, γ-side-chain structure did not significantly influence polymerization efficiency. Indeed, the polymerization efficiencies of γ-(L)-functionalized building blocks (Figure 3c) exhibited the least sensitivity to variations in side-chain structure of all four types of side chains tested. In addition, the DNA-templated polymerization of γ-functionalized PNA aldehydes exhibited the same inability to generate significant full-length product in the presence of mismatched templates as with the α-building blocks (Figure 3b), although the γ-(L) building blocks required polymerization at a higher temperature (50 °C) to exhibit sequence specificity comparable to that of the α-functionalized building blocks at 40 °C (Figure 3b). The polymerization efficiency of the γ-(L) building blocks on a matched template did not suffer as a result of the higher temperature (data not shown). Our results indicate that the presence of a variety of non-polar, polar, and charged side chains in all three polymerization-competent substrate types (α-(L), α-(D), and γ-(L)) does not significantly impair sequence specificity.

Relationship Between Melting Temperature and Polymerization Efficiency

We hypothesized that the observed differences in polymerization efficiency reflect the ability of a functionalized building block to bind the DNA template, rather than the ability of a substrate to adopt conformations that favor polymerization once paired with the template. This model predicts that polymerization efficiencies should correlate strongly with melting temperatures of the PNA aldehyde building blocks. To test this hypothesis, we measured the apparent aggregate melting temperature of eight equivalents (one equivalent per template codon) of each functionalized building block, as well as that of the unfunctionalized substrate, hybridized to a linear DNA template containing eight successive repeats of the 5’-AATCC-3’ codon. All but two building blocks exhibited a single cooperative melting transition (Figure S3a–d) presumably corresponding to the assembly of eight pentamer PNA aldehydes on the DNA template. Both the γ-(D)-glutamine and the γ-(D)-glutamate building blocks exhibited two cooperative melting transitions—a major transition at ∼32 °C and a minor transition at ∼47 °C. For these two building blocks, melting temperatures were computed using the major transition.

The apparent melting temperatures (Table 1) correlated strongly with observed DNA-templated polymerization efficiencies for virtually all of the 20 building blocks tested (Figure 4). Similar to the polymerization efficiency trends, side-chain regio- and stereochemistry were major determinants of Tm, with γ-(L) ≥ α-(D) ≥ α-(L) >> γ-(D), while side-chain structure did not strongly influence melting temperatures. Compared to unmodified PNA, the γ-(L)-functionalized PNA building blocks exhibited significantly higher melting temperatures while α-functionalized PNA building blocks showed modest reductions in Tm. These observations are consistent with previous reports,22–25,29 although only a small number of studies using γ-modified PNAs have been described. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that melting temperatures of side-chain-modified PNA aldehydes are the major determinant of their polymerization efficiencies, rather than the possibility that specific side-chain structures or stereochemistries perturb chemical steps involved in building block coupling without affecting pairing to the template.

Table 1.

Apparent Aggregate Melting Temperature for PNA-DNA Duplexes

| α-Building Block | Apparent Tm (°C) | γ-Building Block | Apparent Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (L)-Lysine | 49.9 | (L)-Lysine | 58.0 |

| (L)-Phenylalanine | 41.1 | (L)-Phenylalanine | 59.3 |

| (L)-Leucine | 46.0 | (L)-Leucine | 61.0 |

| (L)-Glutamine | 45.1 | (L)-Glutamine | 59.3 |

| (L)-Glutamate | 43.0 | (L)-Glutamate | 54.7 |

| (D)-Lysine | 53.4 | (D)-Lysine | 31.1 |

| (D)-Phenylalanine | 51.1 | (D)-Phenylalanine | 27.8 |

| (D)-Leucine | 49.5 | (D)-Leucine | 30.4 |

| (D)-Glutamine | 52.7 | (D)-Glutamine | 31.5 |

| (D)-Glutamate | 46.3 | (D)-Glutamate | 29.5 |

| Unfunctionalized | 53.0 |

Conditions for Tm measurement: 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 0.67 µM (AATCC)8 DNA template, 5.33 µM PNA NH2-ggat*t-CHO building block; UV measured at 260 nm from 20 °C to 90 °C, in 0.1 °C increments. Values for γ-(D)-glutamine and γ-(D)-glutamate correspond to the major hypochromicity transition (see main text).

Figure 4.

Correlation between apparent aggregate melting temperatures and polymerization efficiencies of functionalized building blocks. The melting temperatures (diamonds) from Table 1 are superimposed on the polymerization efficiency data (bars) from Figure 3c.

Modeling the Effects of Side Chains on PNA-DNA Heteroduplex Structure

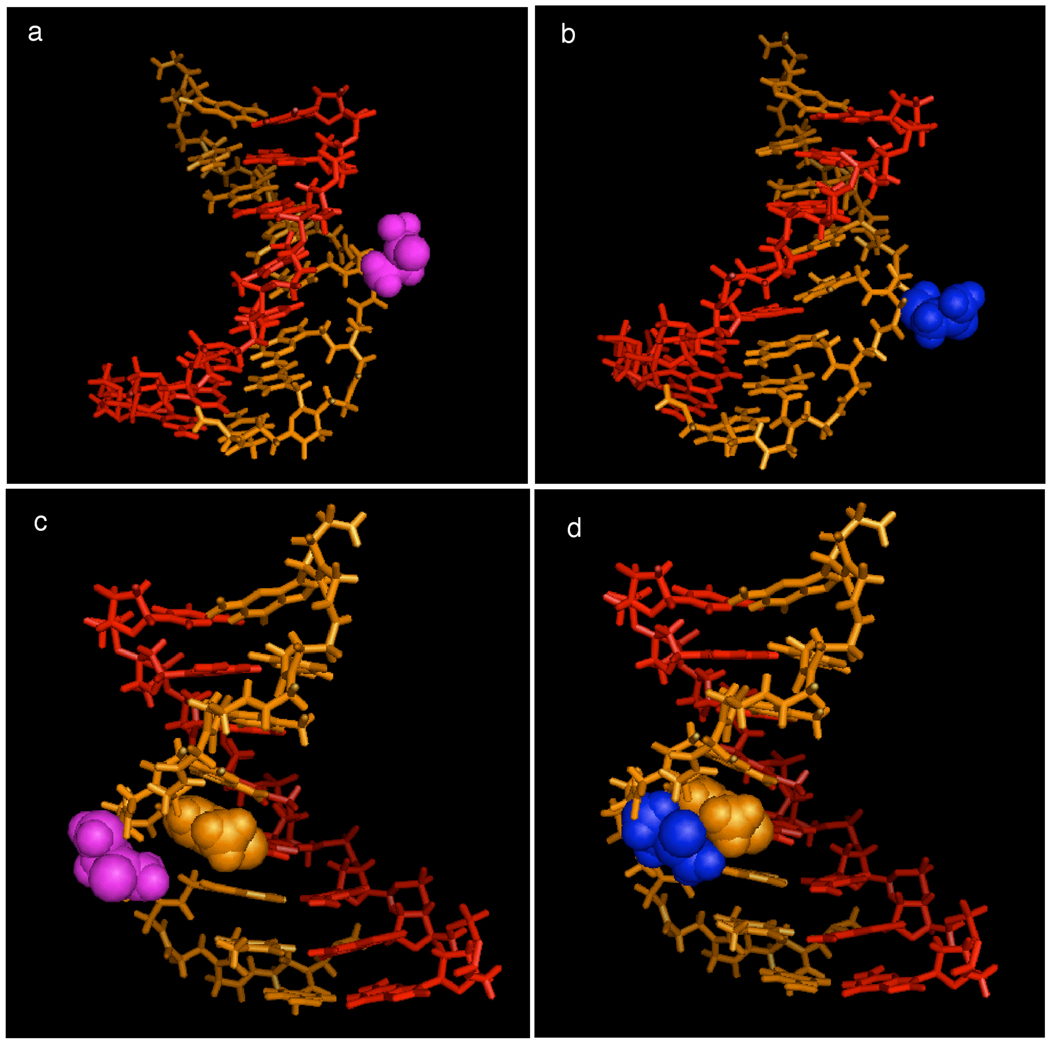

To understand the effect of side-chain regio- and stereochemistry on Tm and polymerization efficiency, we modeled the conformation that the α-(L), α-(D), γ-(L), and γ-(D) building blocks containing a glutamine side chain would adopt when placed in the middle of a PNA-DNA duplex.30 We optimized side-chain geometry using molecular mechanics and the Amber99 force field with an explicit solvation model while fixing the position of the other PNA-DNA heteroduplex atoms. The results suggest that the slightly increased polymerization efficiency and Tm observed for α-(D) building blocks over α-(L) building blocks may arise from the slightly lower steric hindrance imposed by α-side chains of (D) stereochemistry (Figure 5b) than those of (L) stereochemistry (Figure 5a) in the template-substrate complex. Indeed, a single point energy calculation predicts that the α-(D)-glutamine-containing solvated duplex structure is stabilized compared with the α-(L)-glutamine-containing structure (see Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

PNA-DNA heteroduplex gctat*gtc • d(GACATAGC) with glutamine side-chain modeled at α- and γ- carbons on the t* thymine PNA nucleotide. (a) α-(L)-glutamine modification; (b) α-(D)-glutamine modification; (c) γ-(L)-glutamine modification; (d) γ-(L)-glutamine modification. Side-chain geometry was optimized using molecular mechanics with an Amber99 force field and an explicit solvation model; the other atoms within the PNA-DNA heteroduplex were fixed during the optimization. Optimization was performed using HyperChem 8.0, and the optimized structures were rendered with PyMol. Colors indicate the following: PNA (orange), DNA (red), (D)-glutamine (blue), (L)-glutamine (magenta). In (c) and (d), the PNA thymine nucleobase that introduces a steric clash with the γ-(D)-glutamine side chain is shown as an orange space-filling representation.

In contrast to the α-functionalized substrates, the polymerization efficiencies and melting temperatures observed for γ-(L) building blocks differ greatly from their γ-(D) counterparts. Our modeling results suggest that the inability of γ-(D)-functionalized building blocks to polymerize efficiently on DNA templates and their unusually low Tm is likely due to a severe steric clash between the γ-(D) side chain and the interior of the PNA-DNA heteroduplex (Figure 5d). Consistent with our findings, this steric clash is predicted to be completely alleviated in the case of the γ-(L)-side-chain stereochemistry (Figure 5c), and single point energy calculations predict the γ-(L)-glutamine structure to be much more stable than the γ-(D)-glutamine structure (see Supporting Information).

Polymerization Rate

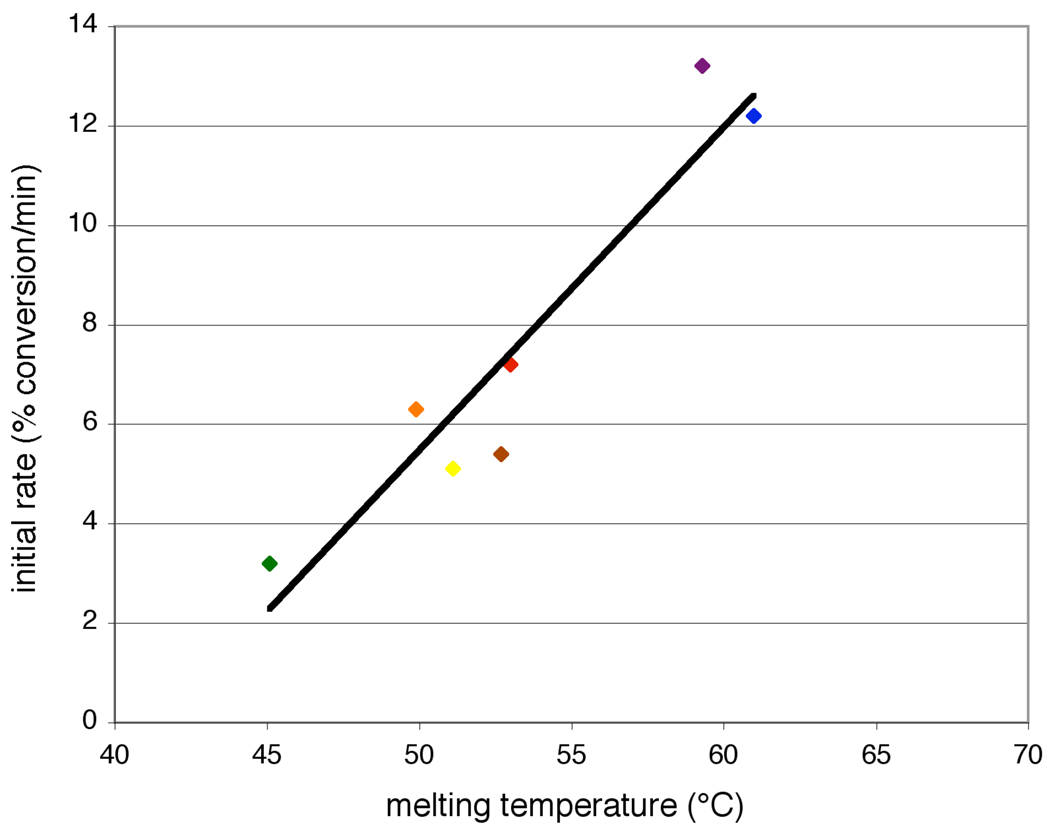

We further hypothesized that the kinetics of DNA-templated polymerization should be consistent with the above trends in PNA-DNA duplex stability. To explore the effect of building block functionalization on polymerization kinetics, we measured the initial rates of full-length product formation at 40 °C for a representative set of α-(L)-, α-(D)-, and γ-(L)-functionalized building blocks, as well as for the unfunctionalized building block. The building blocks were polymerized as before, however the reactions were quenched with excess allyl amine at several timepoints before 10% of the template had been consumed. The initial rate of full-length product formation was then estimated by linear regression.

At 40 °C, the γ-(L) building blocks polymerize at the fastest initial rate (∼13% conversion/min) and have the highest apparent Tm (∼60 °C). The α-substituted building blocks attain comparable product yield after 30 minutes (Figure 3b), however polymerize with a substantially decreased initial rate (3–7% conversion/min), consistent with their lower Tm’s (45–53 °C), than the γ-(L) building blocks. Among the building blocks whose polymerization rates were measured, the α-(L)-glutamine building block exhibited both the lowest initial rate of product formation (3.2% conversion/min) and the lowest Tm (45.1 °C).

These results support the hypothesis that building blocks with higher apparent aggregate melting temperatures polymerize at a faster initial rate than do building blocks with lower apparent melting temperatures (Figure 6). Since the polymerization reactions are equilibrated prior to reductive amination, building block Tm determines the proportion of building block annealed to the template. The correlation between polymerization rate and melting temperature therefore suggests that under the conditions tested, the rate of covalent bond formation exceeds the rate of building block-template dissociation, and that building block-template hybridization is at least partially rate-determining for full-length product formation. This characteristic has been previously observed for other DNA-templated reactions31–33 when rates of bond formation in the base-paired complex exceed the rate of template-reagent hybridization.

Figure 6.

Correlation between initial rate of product formation and apparent aggregate melting temperature. Initial rates were measured for α-(L)-glutamine (green), α-(L)-lysine (orange), α-(D)-phenylalanine (yellow), α-(D)-glutamine (brown), γ-(L)-phenylalanine (purple), γ-(L)-leucine (blue) and unfunctionalized (red) building blocks by measuring product formation before 10% of the template was consumed. Reactions were performed as described in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Melting temperatures are from Table 1. The trend line was generated by computing a linear regression (r2 = 0.89) for the data.

Conclusion

We describe here the DNA-templated polymerization of functionalized PNA aldehydes, representing the first non-enzymatic translation of a nucleic acid sequence into a side-chain-containing synthetic polymer. Researchers have also been able to generate modified biopolymers enzymatically by exploiting the tolerance of DNA34–39 and RNA40–42 polymerases, or of the ribosome43,44 for modified substrates; such an approach, however, is limited to backbone structures that are compatible with the biosynthetic machinery. The findings reported here lay a foundation for the evolution of sequence-defined synthetic polymers bearing side-chain functionality determined by the researcher, rather than by compatibility with the biosynthetic machinery. In addition, these results demonstrate that oligomeric building blocks containing side-chains of varying position within the building block, structure, regiochemistry, and stereochemistry can participate in the non-enzymatic translation of nucleic acid sequences into non-nucleic acid polymers, a step presumed to have occurred (though under very different conditions than the ones used here) in the prebiotic world.

We found that PNA aldehydes functionalized with lysine side chains at various positions within the building block undergo efficient and sequence-specific DNA-templated polymerization. The tolerance of this reaction to the position of the nucleotide containing the side-chain within the building block also enables DNA-templated polymerization to generate densely functionalized sequence-defined synthetic polymers from multiply-functionalized building blocks, including a PNA 40-mer in which 24 of the PNA nucleotides contain a side-chain group.

In addition, our studies reveal that polar, positively and negatively charged, aromatic, and aliphatic side chains can be polymerized in an efficient and sequence-programmed manner on a DNA-template. By measuring the polymerization efficiencies of building blocks modified at the α- and γ-positions with both possible stereochemistries at each position, we observed that all functionalized building blocks with the exception of those with (D)-side chains at the γ-carbon are efficient DNA-templated polymerization substrates. Polymerization efficiency depends predominantly on side-chain position and stereochemistry rather than on side-chain size, hydrophobicity, or charge. Apparent aggregate melting temperatures correlate with polymerization rate and suggest that building block hybridization to the template is at least partially rate-limiting for polymerization. In light of our findings, we conclude that PNA aldehydes functionalized at the γ-carbon with (L)-side chains or at the α-carbon with either side-chain stereochemistry are efficient participants in DNA-templated polymerization. In contrast, γ-(D)-modified PNA building blocks are unsuitable for DNA-templated polymerization, likely because of poor hybridization to the template resulting from steric interference with the PNA nucleobases.

The DNA-templated polymerization of functionalized building blocks combined with functional selection, amplification, and template mutation provides a potential method for realizing the laboratory evolution of sequence-defined polymers bearing diverse chemical functional groups. Such a system raises the possibility of discovering synthetic polymers with functional properties that in principle could extend beyond those of natural proteins and nucleic acids by virtue of specialized building blocks containing, for example, biophysical probes, small-molecule catalysts, electroactive groups, or known ligands to biological targets.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Small molecules were purified by flash chromatography using a Biotage SP4 purification system and a hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient. Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on E. Merck precoated (0.25 mm) silica gel 60-F254 plates. Visualization was accomplished with UV light and staining with 0.3% ninhydrin in n-butanol followed by heating. Characterization of small-molecule products was accomplished through proton magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (13C-NMR) obtained using Varian iNOVA 500 (500 MHz) NMR spectrophotometers at 22°C as well as electrospray mass spectrometry on a Waters Q-TOF Premier instrument. Unless otherwise noted, all commercially available reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was distilled from sodium and benzophenone prior to use. Dimethylformamide (DMF) and CH2Cl2 were purified by passage through activated alumina. Fmoc-protected amino acids were purchased from Novabiochem. Amino ester hydrochlorides were purchased from Chem-Impex International, Inc. All non-functionalized PNA monomers were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized using standard automated solid-phase phosphoramidite coupling methods on a PerSeptive Biosystems Expedite 8909 DNA synthesizer. All reagents and phosphoramidites for DNA synthesis were purchased from Glen Research. Oligonucleotides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC using a C18 stationary phase and an acetonitrile/100 mM triethyl ammonium acetate (TEAA) gradient and quantitated using UV spectroscopy carried out on a Nanodrop ND1000 Spectrophotometer.

Abbreviations: RT, room temperature; Fmoc, Fluorenyl methoxy carbonyl; Boc, tert-Butyl oxy carbonyl; BOP, Benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate; DhbtOH, 3-Hydroxy-1,2,3-benzo-triazin-4(3H)-one; EDC, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride; HOBt, 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole; EtOAc, ethyl acetate; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TAPS, N-Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid; TBE, tris/borate/EDTA;

Synthesis of γ-(L)-Lysine-Functionalized Guanine and Adenine Fmoc-PNA Monomers

The synthesis of γ-(L)-lysine-functionalized Fmoc-PNA guanine and adenine monomers was adapted from the previously described syntheses of the Boc-γ-(L)-lysine(Fmoc) thymine monomer24 and unfunctionalized Fmoc-PNA guanine and adenine monomers.45

tert-Butyl (S)-5-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-oxohexyl-carbamate (1)

This compound was prepared according to the protocols of Wang et al.46

(S)-allyl 2-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexylamino)acetate (2)

To a stirring solution of Boc-Gly-OH (3 g) in 30 mL dry acetonitrile was added Cs2CO3 (6.70 g). After 30 min., allyl bromide (1.95 g) was added. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was suspended in EtOAc and washed with H2O, 1M aqueous HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield 3.32 g (90.0%) of Boc-Gly-OAll as a yellow oil. Boc-Gly-OAll (3.32) was dissolved in 20 mL of anhydrous TFA and stirred for one hour. The reaction was evaporated under reduced pressure, after which toluene and CH2Cl2 were added and evaporated under reduced pressure to get rid of residual TFA. The resulting crystalline solid was suspended in 10 mL of dry CH2Cl2 and dissolved by the addition of N,N,-Diisopropylethylamine (2.0 mL). To this stirring solution was added 1 (1.10 g) in 10 mL of dry CH2Cl2. After 15 min., sodium triacetoxyborohydride (621 mg) was added. After one hour, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 15 mL of saturated aqueous Na2CO3. After stirring for 10 minutes, the reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by flash column chromatography [Rf = 0.50 (EtOAc)] to yield 1.20 g (89.0%) of 2 as a white foam. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.69 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.56 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.29 (m, 4H, Fmoc–H), 5.85 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.43 (br s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 5.17–5.30 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 4.84 (br s, 1H, Boc–NH), 4.56 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, O–CH2–CH=CH2), 4.36 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.16 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.63 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.34 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2All), 3.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.4, 156.7, 144.3, 141.5, 132.1, 127.8, 127.2, 125.3, 120.1, 118.8, 79.1, 66.5, 65.6, 60.6, 53.0, 51.1, 50.9, 47.5, 40.4, 32.8, 30.0, 28.7, 23.2, 14.4; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C31H41N3O6 [M + H]+, 552.31, found 552.31.

2-(2-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-guanin-9-yl)acetic acid (3a)

This compound was prepared according to the protocols of Debaene and Winssinger.27

(S)-allyl 2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(2-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-guanin-9-yl)acetamido)acetate (4a)

To a stirring solution of 2 (600 mg) in 8 mL of dry DMF was added 3a (457 mg), BOP reagent (602 mg), HOBt (184 mg), and N,N,-Diisopropylethylamine (285 µL). After 6 hours, the reaction was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was dissolved in EtOAc and washed with H2O, 1M aqueous HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced. The resulting oil was purified by flash column chromatography [Rf = 0.40 (10% MeOH/EtOAc)] to yield 386 mg (37.2%) of 11a as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ major rotamer only 7.98 (s, 1H, guanine–H), 7.10–7.80 (m, 18H, Fmoc–H + phenyl–H), 6.36 (s, 1H, Bhoc–CH–O), 5.85 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.14–5.33 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 4.80 (s, 2H, guanine–CH2–CO), 4.54 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, O–CH2–CH=CH2), 4.18–4.42 (m, 4H, guanine–CH2–CO + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.16 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.63 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.34 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2All), 3.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.7, 167.1, 166.8, 162.8, 157.7, 156.7, 149.3, 147.4, 143.9, 141.5, 131.8, 127.2–128.8, 124.6, 120.2, 119.2, 118.8, 78.9, 66.2, 53.0, 50.1, 47.6, 44.4, 40.4, 36.7, 31.7, 28.7, 23.2; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C52H57N8O10 [M + H]+, 953.42, found 953.42.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(2-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-guanin-9-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (5a)

To a stirring solution of 4a (386 mg) in 8 mL of THF at RT was added N-ethyl aniline (960 µL) followed by (Ph3P)4Pd (205 mg). After stirring for 60 minutes, the reaction was evaporated under reduced pressure to give a yellow film. The yellow film was redissolved in EtOAc and washed with saturated aqueous NaHSO4, H2O and brine to afford 250 mg (68%) of 5a as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer only 11.20 (s, 1H, guanine–H), 7.20–7.90 (m, 18H, Fmoc–H + phenyl–H), 6.84 (s, 1H, Bhoc–CH–O), 4.18–4.42 (m, 4H, guanine–CH2–CO + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.16 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.63 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.34 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2H), 3.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 207.2, 156.5, 154.2, 144.3, 141.5, 140.7, 135.5, 134.4, 133.8, 132.2, 127.2–129.5, 120.8, 78.7, 47.8, 31.4, 29.0, 22.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C49H52N8O10 [M – H]−, 911.37, found 911.3.

2-(6-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-adenin-9-yl)acetic acid (3b)

This compound was prepared according to the protocols of Debaene and Winssinger.27

(S)-allyl 2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(6-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-adenin-9-yl)acetamido)acetate (4b)

Following the procedure used to prepare compound 4a, 2 (600 mg) was converted to 350 mg (34.3%) of 4b [Rf = 0.70 (10% MeOH/EtOAc)]as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ major rotamer only 9.03 (s, 1H, Bhoc–NH), 8.64 (s, 1H, adenine–H), 7.96 (s, 1H, adenine–H), 7.10–7.69 (m, 18H, Fmoc–H + phenyl–H), 6.96 (Bhoc–CH), 5.85 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.43 (br s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 5.17–5.30 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 4.84 (br s, 1H, Boc–NH), 4.56 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, O–CH2–CH=CH2), 4.42 (m, 2H, adenine–CH2–CO), 4.36 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.16 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.63 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.34 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2All), 3.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.4, 168.8, 167.5, 166.9, 156.7, 152.9, 152.8, 151.7, 150.6, 149.5, 144.3, 141.5, 132.1, 127.8, 127.2, 125.3, 121.5, 120.1, 119.0, 79.4, 78.9, 66.5, 65.6, 60.6, 53.0, 51.1, 50.9, 47.5, 40.4, 32.8, 30.0, 28.7, 23.2, 14.4; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C52H57N8O9 [M + H]+, 937.42, found 937.4.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(6-(benzhydryloxycarbonylamino)-adenin-9-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (5b)

Following the procedure used to prepare compound 5a, 4b (350 mg) was converted to 269 mg (80.5%) of 5b as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer only 10.89 (s, 1H, Bhoc–NH), 8.50 (m, 1H, adenine–H), 7.96 (s, 1H, adenine–H), 7.10–7.69 (m, 18H, Fmoc–H + phenyl–H), 6.96 (Bhoc–CH), 5.85 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.43 (br s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.84 (br s, 1H, Boc–NH), 4.42 (m, 2H, adenine–CH2–CO), 4.36 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.16 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.63 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.34 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2H), 3.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.59 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 171.4, 167.4, 156.9, 153.0, 144.5, 141.6, 132.2, 127.2–129.2, 125.9, 120.8, 77.9, 65.7, 47.5, 45.2, 32.0, 30.0, 29.0, 23.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C49H52N8O9 [M – H]−, 895.38, found 895.3.

Synthesis of α-Functionalized Thymine Fmoc-Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Monomers

The synthesis of α-functionalized Fmoc-PNA thymine monomers was adapted from the previously described syntheses of α-functionalized Boc-PNA thymine monomers.22,23 The representative synthesis of the α-(L)-lysine-thymine monomer is provided below.

(4H-fluoren-9-yl)methyl 2-oxoethylcarbamate (6)

This compound was prepared according to the protocols of Wang et al.46

(S)-allyl 2-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexanoate (7a)

To a stirring solution of 6 (773 mg) and Nε-Boc-L-lysine allyl ester hydrochloride in 12 mL dry CH2Cl2 was slowly added N,N,-Diisopropylethylamine (340 µL) over 2 minutes. After stirring for 10 minutes at RT, sodium triacetoxyborohydride (525 mg) was added to the reaction. After 90 minutes of additional stirring at RT, the reaction was quenched with saturated aqueous Na2CO3. The reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 and the combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by flash column chromatography [Rf = 0.60 (EtOAc)] to yield 716 mg (61.2%) of 7a as a clear, colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.56 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.29 (m, 4H, Fmoc–H), 5.86 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.58 (br s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 5.17–5.30 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 4.81 (br s, 1H, Boc–NH), 4.57 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, O–CH2–CH=CH2), 4.34 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O) 4.17 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.25 (m, 1H, NH–CH–CO2All), 3.17 (t, 2H, J = 2.5 Hz, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 3.04 (m, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.50–2.76 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–NH), 1.16–1.66 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.41 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.2, 156.3, 155.9, 143.9, 141.0, 131.7, 127.0, 127.6, 124.8, 120.0, 119.2, 78.6, 66.2, 65.1, 60.9, 60.0, 47.0, 40.9, 40.0, 32.8, 29.9, 28.0, 22.4, 14.0; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C31H41N3O6 [M + H]+, 552.31, found 552.30.

(S)-allyl 2-(N-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexanoate (8a)

To a stirring solution of 7a (358 mg), 1-thymine acetic acid (239 mg), and DhbtOH (212 mg) in DMF (13 mL) at 40 °C was added EDC (268 mg). After stirring overnight at 40 °C, H2O was then added, forming a white precipitate, and the reaction mixture was extracted into EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with 1M aqueous HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, H2O and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 426 mg (93.4%) of 8a as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.33 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.86 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.67 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH), 7.28–7.42 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.77 (m, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 5.87 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.15–5.31 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 4.77 (s, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.52 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, O–CH2–CH=CH2), 4.37 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.32 (m, 1H, N–CH–CO2All), 4.22 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.40 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–NH), 3.29 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.91 (m, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2) 1.75 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.10–1.50 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.35 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3), minor rotamer 5.96 (m, 1H, CH2–CH=CH2), 5.20–5.37 (m, 2H, CH=CH2), 1.77 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 171.3, 168.2, 165.2, 157.0, 156.4, 151.9, 144.3, 143.0, 141.8, 133.2, 128.4, 127.6, 125.8, 121.0, 118.2, 108.6, 78.0, 66.2, 65.9, 60.4, 49.2, 47.7, 47.0, 38.1, 30.2, 29.0, 23.9, 21.7, 15.3, 12.6; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C38H47N5O9 [M + H]+, 718.35, found 718.34.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexanoic acid (9a)

Following the procedure used to prepare compound 5a, 8a (426 mg) was converted to 347 mg (85%) of 9a as a flakey-off white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.33 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.86 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.67 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.28–7.42 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.77 (m, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.65 (s, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.35 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.29 (m, 1H, N–CH–CO2H), 4.22 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.37 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–NH), 3.25 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.88 (m, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2) 1.74 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.10–1.50 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.34 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 171.3, 165.2, 156.4, 151.9, 144.7, 141.6, 132.9, 132.1, 129.7, 128.4, 128.0, 125.9, 120.8, 108.8, 78.1, 66.2, 60.3, 55.8, 47.7, 29.0, 21.6, 15.0, 12.6; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C38H47N5O9 [M – H]−, 676.30, found 676.30.

The following α-functionalized thymine monomers were prepared analogously:

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexanoic acid

All characterization data matched 9a.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-3-phenylpropanoic acid (9b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.32 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.86 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.62 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.08–7.42 (m, 10H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H + phenyl–H), 6.88 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.5–4.6 (m, 1H, N–CH–CO2H) 4.53 (q, J = 20 Hz, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.27 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.17 (t, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 2.60–3.20 (m, 6H, phenyl–CH2–CH + Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–N + Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 1.76 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.1, 168.5, 166.3, 165.2, 165.1, 165.0, 151.8, 151.7, 151.5, 143.2, 143.1, 142.8, 141.5, 140.6, 140.1, 139.0, 138.1, 136.1, 133.2, 130.6, 130.2, 129.7, 129.6, 129.2, 128.9, 128.8, 128.4, 127.8, 127.7, 127.2, 126.5, 124.9, 124.0, 122.1, 120.7, 120.6, 110.5, 109.3, 108.7, 78.9, 43.7, 42.5, 28.1, 18.8, 12.7, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C33H32N4O7 [M – H]−, 595.22, found 595.2.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-3-phenylpropanoic acid

All characterization data matched 9b.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-4-methylpentanoic acid (9c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.28 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.86 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.67 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H) 7.2–7.5 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.86 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.65 (s, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.2–4.6 (m, 4H, N–CH–CO2H + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.36 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–N), 3.20 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 1.4–1.8 (m, 3H, CH3–CH–CH3 + CH–CH2–CH), 1.74 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3) 0.86 (m, 6H, CH3–CH–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 173.3, 170.3, 168.4, 165.2, 157.0, 156.3, 152.2, 151.7, 144.5, 143.1, 141.5, 139.9, 136.2, 134.3, 133.2, 131.9, 128.9, 128.8, 128.6, 128.3, 127.7, 125.8, 125.6, 125.0, 120.8, 117.0, 115.2, 108.7, 67.7, 66.1, 57.1, 48.9, 47.5, 45.6, 38.3, 35.1, 31.1, 25.8, 25.1, 23.5, 22.5, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C30H34N4O7 [M – H]−, 561.23, found 561.2.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-4-methylpentanoic acid

All characterization data matched 9c.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-5-oxo-5-(tritylamino)pentanoic acid (9d)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.27 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 8.58 (s, 1H, trityl–NH), 7.87 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.65 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.10–7.44 (m, 20H, thymine–H + trityl–H + Fmoc–H), 4.61 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.33 (d, 2H, J = 10 Hz, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.24 (m, 1H, N–CH–CO2H), 4.14 (t, 1H, J = 10 Hz, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.58 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–N), 3.20 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.00–2.44 (m, 4H, CH–CH2–CH2–CO–NH–trityl), 1.72 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 172.2, 169.1, 168.0, 165.1, 157.0, 151.7, 145.6, 145.5, 144.5, 143.0, 141.4, 129.2, 128.3, 128.1, 127.8, 127.0, 125.8, 120.8, 108.7, 69.9, 69.0, 67.7, 66.2, 47.4, 28.1, 25.8, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C48H45N5O8 [M – H]−, 818.32, found 818.3.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-5-oxo-5-(tritylamino)pentanoic acid

All characterization data matched 9d.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-5-tert-butoxy-5-oxopentanoic acid (9e)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.29 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.87 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.66 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.28–7.42 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.86 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.63 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.33 (d, 2H, J = 10 Hz, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.18–4.29 (m, 2H, N–CH–CO2H + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.44 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2–N), 3.25 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.22 (t, 2H, J = 10 Hz, CH2–CH2–CO2t-Bu), 2.08–2.18 (m, 2H, CH–CH2–CH2–CO2t-Bu), 1.73 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.36 (m, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 172.5, 168.0, 165.1, 157.0, 151.7, 144.5, 143.0, 141.4, 128.3, 127.7, 125.8, 120.8, 119.1, 108.6, 80.4, 66.1, 59.8, 48.6, 47.5, 32.2, 30.9, 28.1, 24.8, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C33H38N4O9 [M – H]−, 633.25, found 633.2.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)ethyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)-5-tert-butoxy-5-oxopentanoic acid

All characterization data matched 9e.

Synthesis of γ-Functionalized Thymine Fmoc-Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) Monomers

The synthesis of γ-functionalized Fmoc-PNA thymine monomers was adapted from the previously described synthesis of the Boc-γ-(L)-lysine(Fmoc) thymine monomer.24 The representative synthesis of the γ-(D)-lysine-thymine monomer is presented below.

tert-Butyl (R)-5-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-oxohexyl-carbamate (10a)

This compound was prepared according to the protocols of Wang et al.46

(R)-benzyl 2-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexylamino)acetate (11a)

To a stirring solution of 10a (965 mg) and benzyl glycinate hydrochloride (473 mg) in 15 mL CH2Cl2at RT was added N,N,-Diisopropylethylamine (410 µL) over 2 minutes. After stirring for 10 minutes, sodium triacetoxyborohydride (630 mg) was added. After stirring for 90 minutes, 15 mL of saturated aqueous Na2CO3 was added to quench the reaction. After stirring for 10 minutes, the reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by flash column chromatography [Rf = 0.50 (EtOAc)] to yield 662 mg (51.7%) of 11a as a clear, colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.71 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.58 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.25–7.37 (m, 9H, Fmoc–H + phenyl–H), 5.24 (br d, 1H, J = 10 Hz, Fmoc–NH), 5.12 (s, 2H, O–CH2–phenyl), 4.80 (br s, 1H, Boc–NH), 4.39 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.18 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.65 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 3.41 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CO2Bn), 3.06 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Boc–NH–CH2–CH2), 2.61 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–NH), 1.2–1.5 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.43 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.4, 156.8, 156.3, 144.1, 141.8, 135.9, 128.7, 128.5, 128.1, 127.7, 125.2, 79.4, 66.8, 66.3, 53.0, 51.4, 47.9, 47.0, 40.3, 33.0, 30.4, 28.8, 23.3; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C35H43N3O6 [M + H]+, 602.32, found 602.32.

(R)-benzyl 2-(N-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetate (12a)

To a stirring solution of 11a (662 mg), 1-thymine acetic acid (262 mg) and HOBt (8.13 mg) in 23 mL dry DMF at RT was added EDC (315 mg). After stirring overnight, H2O was added, forming a white precipitate. The reaction mixture was extracted into EtOAc. The combined organic layers were subsequently washed with 1M aqueous HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, H2O and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield 500 mg (59.2%) of 12a as a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.33 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.86 (m, 2H, Fmoc–CH), 7.67 (m, 2H, Fmoc–CH), 7.35 (m, 9H, phenyl–H + Fmoc–H), 7.19 (s, 1H, thymine–H), 6.79 (m, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 5.20 (d, 2.5 Hz, 1H, Boc–NH), 5.12 (s, 2H, O–CH2–phenyl), 4.73 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.26–4.40 (m, 3H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2+ Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.21 (t, J = 10 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 4.11 (m, 2H, N–CH2–CO2Bn), 3.33 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N), 2.91 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–NH–Boc), 1.69 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.10–1.50 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.36 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3), minor rotamer 11.32 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 1.72 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.8, 168.6, 165.0, 156.1, 156.7, 152.0, 144.2, 142.3, 141.8, 128.8, 128.7, 128.3, 128.0, 125.8, 120.6, 109.0, 77.9, 66.8, 66.5, 66.3, 60.4, 52.1, 50.2, 47.8, 29.9, 28.8, 23.7, 21.6, 15.0, 12.6; HRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C42H49N5O9 [M + H]+, 768.36, found 768.36.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (13a)

To a stirring solution of 12a (748 mg) in 91.3 mL dry methanol was added Pd/C (183 mg) over two minutes. The reaction mixture was placed under H2 (balloon pressure). After stirring overnight, TLC analysis showed disappearance of starting material [Rf = 0.40 (EtOAc)], and the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield 352 mg (80.0%) of 13a as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.33 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.87 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.69 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.35 (m, 4H, Fmoc–H), 7.17 (s, 1H, thymine–H), 6.75 (m, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.65 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.43 (m, 2H, N–CH2–CO2H), 4.33 (m, 1H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2), 4.25 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O), 4.20 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.35 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N), 2.86 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–NH–Boc), 1.69 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.10–1.50 (m, 6H, CH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.35 (s, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3), minor rotamer 11.35 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.20 (s, 1H, thymine–H), 1.67 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 174.0, 165.1, 156.3, 151.7, 140.1, 136.1, 130.2, 129.6, 128.0, 110.5, 84.0, 65.5, 49.2, 45.6, 31.6, 30.8, 29.7, 29.2, 28.9, 28.1, 26.9, 22.7, 18.1, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C38H47N5O9 [M – H]−, 676.30, found 676.2.

The following γ-functionalized thymine monomers were prepared analogously:

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((4H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-6-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)hexyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid

All characterization data matched 13a.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-3-phenylpropyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (13b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.24 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.85 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.50–7.62 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.10–7.42 (m, 10H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H + phenyl–H), 4.68 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 3.96–4.80 (m, 6H, N–CH2–CO2H + Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2 + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.30–3.80 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N), 2.64–3.06 (m, 2H, phenyl–CH2–CH), 1.70 (m, 3H, thymine–CH3), minor rotamer 11.31 (s, 1H, imide–NH); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.1, 163.0, 151.7, 149.3, 142.8, 141.4, 140.6, 139.3, 139.0, 136.1, 130.2, 130.1, 129.8, 129.6, 129.3, 129.1, 128.9, 128.8, 128.7, 128.4, 128.3, 128.0, 127.7, 125.9, 124.9, 124.6, 122.1, 121.9, 120.8, 120.6, 108.8, 78.9, 47.3, 42.5, 36.5, 31.5, 31.4, 28.1, 18.8, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C33H32N4O7 [M – H]−, 595.22, found 595.2.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-3-phenylpropyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid

All characterization data matched 13b.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-4-methylpentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (13c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.29 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.87 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.68 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H) 7.1–7.4 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.26 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.67 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 3.8–4.5 (m, 6H, N–CH2–CO2H + Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2 + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.30–3.52 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N), 1.70 (s, 1H, thymine–CH3), 1.2–1.6 (m, 3H, CH3–CH–CH3 + CH–CH2–CH), 0.84 (t, J = 20 Hz, 6H, CH3–CH–CH3), minor rotamer 11.27 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 1.72 (s, 1H, thymine–CH3), 0.82 (t, J = 20 Hz, 6H, CH3–CH–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 171.4, 171.0, 165.1, 156.7, 156.6, 151.7, 144.8, 144.6, 144.5, 144.4, 142.6, 141.5, 128.3, 127.7, 125.9, 125.8, 124.9, 120.8, 120.7, 110.9, 108.8, 65.9, 65.8, 52.4, 52.1, 48.6, 48.4, 48.3, 47.6, 31.1, 25.0, 24.1, 22.4, 22.1, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C30H34N4O7 [M – H]−, 561.23, found 561.2.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-4-methylpentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid

All characterization data matched 13c.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-5-oxo-5-(tritylamino)pentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (13d)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.28 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 8.59 (s, 1H, trityl–NH), 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.68 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.10–7.42 (m, 20H, thymine–H + trityl–H + Fmoc–H), 6.85 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.64 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.16–4.36 (m, 3H, Fmoc–CH–CH2–O + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.92 (m, 2H, N–CH2–CO2H), 3.24–3.44 (m, 3H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2 + Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N) ), 2.16–2.42 (4H, CH–CH2–CH2–CO–NH–trityl), 1.64 (s, 1H, thymine–CH3), minor rotamer 11.25 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 8.53 (s, 1H, trityl–NH), 1.66 (s, 1H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 172.2, 170.9, 168.1, 156.9, 151.6, 145.6, 144.6, 144.5, 142.5, 141.4, 129.2, 128.3, 128.1, 127.8, 127.0, 125.9, 125.6, 120.8, 108.9, 69.9, 66.1, 47.5, 33.2, 31.1, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C48H45N5O8 [M – H]−, 818.32, found 818.3.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-5-oxo-5-(tritylamino)pentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid

All characterization data matched 13d.

(R)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-5-tert-butoxy-5-oxopentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid (13e)

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ major rotamer 11.29 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 7.88 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.68 (m, 2H, Fmoc–H), 7.12–7.43 (m, 5H, Fmoc–H + thymine–H), 6.86 (s, 1H, Fmoc–NH), 4.66 (m, 2H, thymine–CH2–CO), 4.1–4.5 (m, 6H, N–CH2–CO2H + Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2 + Fmoc–CH–CH2–O + Fmoc–CH–CH2), 3.26–3.60 (m, 2H, Fmoc–NH–CH–CH2–N), 2.16 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–CO2t-Bu), 1.74 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–CH), 1.68 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3), 1.36 (m, 9H, tert–butyl–CH3), minor rotamer 11.27 (s, 1H, imide–NH), 1.71 (s, 3H, thymine–CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 172.6, 170.1, 168.1, 165.1, 156.8, 151.6, 144.4, 142.5, 141,1, 139.9, 128.3, 127.7, 125.9, 125.6, 120.8, 108.9, 80.3, 67.7, 66.0, 48.4, 47.5, 35.1, 32.2, 31.1, 28.4, 25.8, 21.7, 12.6; LRMS (ESI-MS m/z) mass calcd for C33H38N4O9 [M – H]−, 633.25, found 633.2.

(S)-2-(N-(2-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)-5-tert-butoxy-5-oxopentyl)-2-(thymin-1(2H)-yl)acetamido)acetic acid

All characterization data matched 13e.

Synthesis of PNA Pentamer Aldehydes

PNA pentamer aldehydes were synthesized using pre-loaded H-Thr-Gly-NovaSyn® TG resin (Novabiochem) and standard automated Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis on an Applied Biosystems 433A peptide synthesizer by adapting previously described protocols.18 PNA pentamer aldehydes were purified by reverse-phase High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) using a C18 stationary phase and an acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) gradient, characterized by electrospray mass spectrometry on a Waters Q-TOF Premier instrument, and quantitated using UV spectroscopy carried out on a Nanodrop ND1000 spectrophotometer.

DNA-Templated Reductive Amination Protocol for Tetramer Building Blocks

Polymerization reactions were prepared by mixing 1 µL 500 mM TAPS pH 8.5 buffer, 1.25 µL 4M NaCl, 20 pmol DNA template and 800 pmol PNA tetramer aldehyde with water to a total volume of 50 µL. DNA template sequence for H2N-ggtt-CHO and H2N-ggt*t-CHO matched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N-TCGCCTTCGTCCTCGAAGGCGAAACCAACC AACCAACCAACCAACCAACCAACCAACCAACC-3’. DNA template sequence for H2N-ggtt-CHO and H2N-ggt*t-CHO mismatched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N- TCGCCTTCGTC CTCGAAGGCGAAACCAACCAACCAACCAACCACACACACACACACACACAC-3’. DNA template sequence for H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO matched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N-TCGCCTTCGTCCTCGAAGGCGAACCCACCCACCCACCCACCC ACCCACCCACCCACCCACCC-3’. DNA template sequence for H2N-gggt-CHO and H2N-ggg*t-CHO mismatched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N-CGCCTTCGTCCTCGAAGGCGAACCCACCCACCCACCCACCCCACACACACACACACACACA-3’. Reactions were heated to 95 °C and then slowly cooled to the reaction temperature. Reductive amination was initiated by the addition of 1 µL of 4M aqueous sodium cyanoborohydride, and reactions were quenched at the indicated time by the addition of 2.5 µL neat (13.3 M) allyl amine. The quenched reactions were desalted using Princeton Separation sephadex minicolumns and separated by denaturing PAGE on a 15% TBE/urea polyacrylamide gel. Denaturing polyacrylamide gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination and densitometry using standard procedures.

DNA-Templated Reductive Amination Protocol for Pentamer Building Blocks

Polymerization reactions were prepared by mixing 1 µL 500 mM TAPS pH 8.5 buffer, 1.25 µL 4M NaCl, 20 pmol DNA template and 640 pmol PNA pentamer aldehyde with water to a total volume of 50 µL. DNA template sequence for matched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N-TCGCCTTCGTCCTCGAAGGCGAAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCC-3’; DNA template sequence for mismatched codon polymerization: 5’-H2N-TCGCCTTCGTCCTCGAAGGCGAAATCCAATCCAATCCAATCCATACCATACCATACCATACC-3’. Reactions were heated to 95 °C and then slowly cooled to the reaction temperature. Reductive amination was initiated by the addition of 1µL of 4M aqueous sodium cyanoborohydride, and reactions were quenched at the indicated time by the addition of 2.5 µL neat (13.3 M) allyl amine. The quenched reactions were desalted using Princeton Separation sephadex minicolumns and separated by denaturing PAGE on a 15% TBE/urea polyacrylamide gel. Denaturing polyacrylamide gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination and densitometry using standard procedures.

Supplementary Material

ESI-MS characterization of PNA tetramer and pentamer aldehydes, MALDI-TOF characterization of DNA-templated polymer products, polymerization of functionalized tetramer aldehydes, molecular modeling protocols, data for melting experiments, and 1H and 13C spectra for all compounds listed in the Experimental Section. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research (N00014-03-1-0749), NIH Grant R01GM065865, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Dr. Yinghua Shen and Walter E. Kowtoniuk for assistance with mass spectrometry, and Leslie Vogt for assistance with molecular modeling. Y.B. gratefully acknowledges the support of an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. M.B. thanks the Harvard College Research Program and the Pechet Family Fund for Undergraduate Research for support.

References

- 1.Kuchta RD, Benkovic P, Benkovic S. J. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6716–6725. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steitz TA. Harvey Lect. 1997–1998;93:75–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yonath A. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:257–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bag BG, von Keidrowski G. Pure Appl. Chem. 1996;68:2145–2152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böhler C, Nielsen PE, Orgel LE. Nature. 1995;376:578–581. doi: 10.1038/376578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung NM, Lohrmann R, Orgel LE. Biochimica, Biophysica Acta. 1971;228:536–543. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(71)90059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozlov IA, Zielinski M, Allart B, Kerremans L, Van Aerschot A, Busson R, Herdewijn P, Orgel LE. Chem. Eur. J. 2000;6:151–155. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000103)6:1<151::aid-chem151>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimoto K, Matsuda S, Takahashi N, Saito I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5646–5647. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gat Y, Lynn DG. In: Templated Organic Synthesis. Diederich F, Stang P, editors. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce GF. Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology. Vol. LII. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1987. pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozlov IA, De Bouvere B, Van Aerschot A, Herdewijn P, Orgel LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2653–2656. doi: 10.1021/ja983958r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Zhan Z-YJ, Knipe R, Lynn DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:746–747. doi: 10.1021/ja017319j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orgel LE. Nature. 1992;358:203–209. doi: 10.1038/358203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt JG, Christensen L, Nielsen PE, Orgel LE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4792–4796. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.23.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt JG, Nielsen PE, Orgel LE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4797–4802. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.23.4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walder JA, Walder RY, Heller MJ, Freier S, Letsinger RL, Klotz IM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:51–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichida JK, Zou K, Horhota A, Yu B, McLaughlin LW, Szostak JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2802–2803. doi: 10.1021/ja045364w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum DM, Liu DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13924–13925. doi: 10.1021/ja038058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue T, Orgel LE. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;162:201–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue T, Orgel LE. Science. 1983;219:859–862. doi: 10.1126/science.6186026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Bërg RH, Buchardt O. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haaima G, Lohse A, Buchardt O, Nielsen PE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:1939–1942. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Püschl A, Sforza S, Haaima G, Dahl O, Nielsen PE. Tet. Lett. 1998;39:4707–4710. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Englund EA, Appella DH. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3465–3467. doi: 10.1021/ol051143z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dragulescu-Andrasi A, Rapireddy S, Frezza BM, Gayathri C, Gil RR, Ly DH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10258–10267. doi: 10.1021/ja0625576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koppelhus U, Awasthi SK, Zachar V, Holst HU, Ebbesen P, Nielsen PE. Antisense and Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002;12:51–63. doi: 10.1089/108729002760070795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debaene F, Winssinger N. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4445–4447. doi: 10.1021/ol0358408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giesen U, Kleider W, Berding C, Geiger A, Orum H, Nielsen P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5004–5006. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.21.5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Englund EA, Appella DH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1414–1418. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eriksson M, Nielsen PE. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:410–413. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gartner ZJ, Grubina R, Calderone CT, Liu DR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1370–1375. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gartner ZJ, Kanan MW, Liu DR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1796–1800. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1796::aid-anie1796>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gartner ZJ, Liu DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6961–6963. doi: 10.1021/ja015873n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horhota A, Zou K, Ichida JK, Yu B, McLaughlin LW, Szostak JW, Chaput JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7427–7434. doi: 10.1021/ja0428255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Latham JA, Johnson R, Toole JJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2817–2822. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.14.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SE, Sidorov A, Gourlain T, Thorpe SJ, Brazier JA, Dickman MJ, Hornby DP, Grasby JA, Williams DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1565–1573. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrin DM, Garestier T, Helène C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1556–1663. doi: 10.1021/ja003290s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakthivel K, Barbas CFI. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2872–2875. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2872::AID-ANIE2872>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thum O, Jäger S, Famulok M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:3990–3993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dewey TM, Mundt AA, Crouch GJ, Zyzniewski MC, Eaton BE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8474–8475. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matulic-Adamic J, Daniher AT, Karpeisky A, Haeberli P, Sweedler D, Beigelman L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaish NK, Fraley AW, Szostak JW, McLaughlin LW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3316–3322. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forster AC, Tan Z, Tan MN, Nalam H, Lin H, Qu H, Cornish VW, Blacklow SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6353–6357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132122100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Josephson K, Hartman MCT, Szostak JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11727–11735. doi: 10.1021/ja0515809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson SA, Josey JA, Cadilla R, Gaul MD, Hassman CF, Luzzio MJ, Pipe AJ, Reed KL, Ricca DJ, Wiethe RW, Noble SA. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:6179–6194. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang G, Mahesh U, Chen GYJ, Yao SQ. Org. Lett. 2003;5:737–740. doi: 10.1021/ol0275567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ESI-MS characterization of PNA tetramer and pentamer aldehydes, MALDI-TOF characterization of DNA-templated polymer products, polymerization of functionalized tetramer aldehydes, molecular modeling protocols, data for melting experiments, and 1H and 13C spectra for all compounds listed in the Experimental Section. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.