Abstract

The hexane- and ethyl acetate-soluble extracts of the leaves of Brassaiopsis glomerulata (Blume) Regel (Araliaceae), collected in Indonesia, were found to inhibit aromatase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of estrogens from androgens, in both enzyme- and cell-based aromatase inhibition (AI) assays. Bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of six known compounds of the steroid and triterpenoid classes (1–6) from the hexane extract, of which 6β-hydroxystimasta-4-en-3-one (5), was moderately active in the cell-based AI assay. Fractionation of the ethyl acetate extract afforded seven pure isolates (7–13) of the modified peptide, fatty acid, monoterpenoid, and benzenoid types, including six known compounds and the new natural product, N-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester (9). The absolute stereochemistry of 9 and the other two peptides, 7 and 8, was determined by Marfey’s analysis. Linoleic acid (10) was found to be active in the enzyme-based AI assay, while 9 and (−)-dehydrololiolide (12) showed activity in the cell-based AI assay.

Keywords: Brassaiopsis glomerulata, Araliaceae, activity-guided isolation, aromatase inhibitors, breast cancer, modified peptides, monoterpenoids, N-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester

1. Introduction

Brassaiopsis glomerulata is a member of the Araliaceae that occurs in south and southeast Asia, including the Vietnamese peninsula (Van Kiem et al., 2003) and in Indonesia. B. glomerulata is a large shrub or small tree with thorns on the stems, palmate leaves with 5–7 leaflets, pendulous panicles, and flowers in glomerulous heads (Regel, 1863). This species has several reported medicinal uses. In Vietnam, the plant is used to treat rheumatism and back pain (Van Kiem et al., 2003). In India, a group of indigenous tribes called the Nagas drink a juice extract of B. glomerulata bark to aid in digestion and to alleviate constipation. The Nagas also used a paste of the bark of B. glomerulata to treat bone fractures and sprains (Changkija, 1999). This species is also used medicinally in China as one of several kinds of “tongcao” (unblocking herbs used to promote urination and assist in lactation) (Shen et al., 1998). Owing to its use as a “tongcao”, B. glomerulata was tested using in vivo anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and diuretic models (Shen et al., 1998). Moreover, B. glomerulata is reported to inhibit carrageenan-induced swelling of rat paws (anti-inflammatory), and induce an antipyretic effect using a rat fever model induced by beer yeast or carrageenan, but no diuretic effect was reported (Shen et al., 1998).

Aromatase is the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the biosynthesis of estrogens (estrone and estradiol) from androgens (androstenedione and testosterone) (Brueggemeier, 2006; Johnston and Dowsett, 2003). Inhibition of aromatase has been shown to reduce estrogen production throughout the body to nearly undetectable levels and aromatase inhibitors are being used clinically to retard the development and progression of hormone-responsive breast cancers [FDA approved aromatase inhibitors include anastrozole (Arimidex®), letrozole (Femara®), and exemestane (Aromasin®)]. As part of a research project directed toward the study of new naturally occurring chemopreventive agents from plants (Kinghorn et al., 2004), the leaves of Brassaiopsis glomerulata (Blume) Regel (Araliaceae), collected in Indonesia, were found to inhibit the aromatase enzyme. Very limited phytochemical studies have been performed on plants in the genus Brassaiopsis, with the only isolates reported to date being three known triterpenes of the lupane subgroup (Van Kiem et al., 2003). Due to the strong aromatase activity and the lack of previous phytochemical research, bioassay-guided fractionation of the leaves of B. glomerulata was initiated to isolate and identify compounds with potential aromatase inhibitory (AI) activity.

2. Results and Discussion

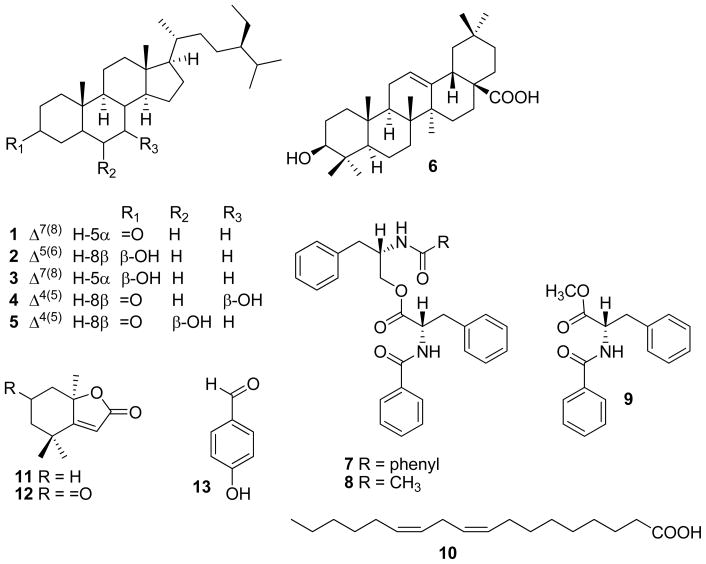

A hexane-soluble extract of the leaves of B. glomerulata exhibited significant aromatase inhibition with both enzyme-based and cell-based AI assays [6.9 percent control activity (PCA) at 20 μg/mL and 7.2 PCA at 20 μg/mL, respectively]. Bioassay-guided fractionation of the hexane extract led to the isolation of six compounds of the steroid and triterpenoid classes [spinasterone (1) (Wandji et al., 2002), stigmasterol (2) (Forgo and Kover, 2004), spinasterol (3) (Kojima et al., 1990), 7β-hydroxy-4,22-stigmastadien-3-one (4) (Ayyad, 2002), 6β-hydroxystigmasta-4-en-3-one (5) (Kontiza et al., 2006), and oleanolic acid (6) (Seebacher et al., 2003)]. The ethyl acetate extract of B. glomerulata was also found to exhibit moderate aromatase inhibition with the enzyme-based and cell-based AI assays (59.3 PCA at 20 μg/mL and 37.0 PCA at 20 μg/mL, respectively).

Bioassay-guided fractionation of the ethyl acetate extract led to the isolation of seven compounds of the dipeptide, modified peptide, fatty acid, monoterpenoid, and benzenoid classes [N-benzoyl-L-phenylalaninyl-N-benzoyl-L-phenylalaninate (7) (Catalan et al., 2003), N-acetyl-L-phenylalaninyl-N-benzoyl-L-phenylalaninate (8) (Xiao et al., 2002), N-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester (9) (Li et al., 2000), linoleic acid (10) (Ramsewak et al., 2001), (−)-dihydroactinidiolide (11) (Mori and Khlebnikov, 1993), (−)-dehydrololiolide (12) (Ravi et al., 1982), and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (13) (Levin and Du, 2002)].

Compound 9 was found to be a new natural product, not previously isolated from any organism. This compound was previously obtained as a synthetic peptide derivative, and was obtained using Lewis-acid cleavage of a resin-bond carbamate (Li et al., 2000). The stereochemistry of 9 at position C-8 was assigned tentatively as L based on the comparison of the observed [α]D of +75° with the literature (Li et al., 2000). Following hydrolysis, a Marfey’s analysis was undertaken to confirm the stereochemistry at this position. Marfey’s analysis has become one of the standard methods for the determination of absolute configuration of compounds containing modified amino acid residues (Lang et al., 2006; Mitova et al., 2006). In the region of interest in the HPLC chromatogram, a peak appeared corresponding to the L-phe Marfey’s derivative. To confirm this assignment, the Marfey’s derivatives of L-phe and D-phe were co-injected separately with the Marfey’s derivative of the hydrolysate of 9. The L-phe derivative directly overlapped the peak of the hydrolysate derivative, while the D-phe derivative eluted considerably after the hydrolysate derivative. The stereochemistry of 9 at position C-8 was therefore determined to be L.

Marfey’s analysis was also performed to confirm the stereochemistry of 7, with positions C-8 and C-8′ both being found to have the L configuration, with this not having been determined at the time of its previous isolation as a natural product (Catalan et al., 2003). Furthermore, the absolute stereochemistry of 8 at positions C-8 and C-8′ was not assigned previously (Xiao et al., 2002). Using Marfey’s analysis, the stereochemistry of positions C-8 and C-8′ for compound 8 was determined to be L at both positions.

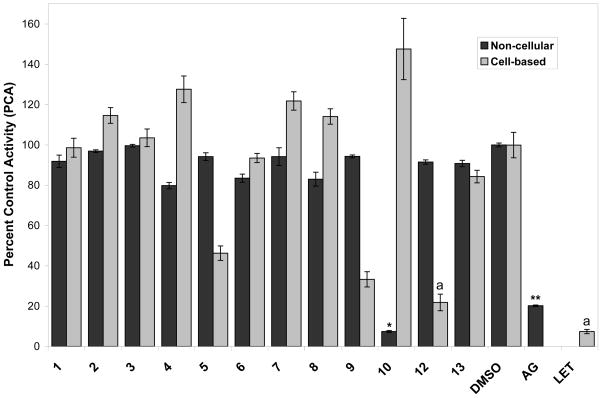

The fatty acid, linoleic acid (10), was found to be significantly more active than the positive control, aminoglutethimide (AG) in the enzyme-based AI assay (7.4 PCA at 20 μg/mL) (P < 0.0001). However, linoleic acid (10) was inactive in the cell-based assay [147.6 PCA at 100 μM, the interference of fatty acids in a noncellular, enzyme-based radiometric AI assay was previously reported in Balunas et al., 2006]. Upon the isolation of linoleic acid from the ethyl acetate extract, the hexane extract was reexamined for the presence of this compound using comparative TLC patterns and trace amounts of it were found in the hexane extract also. Since unsaturated fatty acids can readily undergo lipid oxidation, forming hydroperoxides in the presence of oxygen (Banni et al., 1996; Boyd et al., 1992; Lee et al., 2005), it is possible that linoleic acid in the B. glomerulata extracts may have been oxidized during the course of bioassay-guided fractionation, resulting in decreasing levels of activity of subsequent fractionation steps.

The monoterpenoid (−)-dehydrololiolide (12), was found to be active in the cell-based AI bioassay (21.8 PCA at 50 μM), with no statistical difference in aromatase inhibition activity between compound 12 and the positive control, letrozole (P < 0.0001). The other monoterpenoid isolated from the ethyl acetate extract, (−)-dihydroactinidiolide (11), was not able to be tested in either AI assay due to compound volatilization. Monoterpenoids commonly undergo volatilization and are thus often used for flavoring or as perfume ingredients. The decreasing levels of activity of B. glomerulata during the course of bioassay-guided fractionation may be the result of other active and similarly volatile monoterpenoids. Two chlorinated monoterpenoid pesticides, toxaphene and chlordane, have previously been reported to decrease aromatase activity in a SK-BR-3 cell-based AI assay, although the compounds were not direct inhibitors of aromatase but rather suppressed aromatase expression by antagonizing estrogen-related receptor α-1 (ERRα-1) (Chen et al., 2001; Yang and Chen, 1999). The difference in the activity of 12 in the enzyme-based AI assay (91.5 PCA at 20 μg/mL) and in the cell-based AI assay (21.8 PCA at 50 μM) may be the result of indirect modulation of aromatase expression as was found with these chlorinated monoterpenoid pesticides.

The new natural product, N-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester, 9, was also found to be moderately active in the cell-based AI bioassay (33.3 PCA at 50 μM), although 9 was not active in the enzyme-based AI assay (94.3 PCA at 20 μg/mL). Some structural similarities exist between the chemical structure of 9 and letrozole, one of the AIs currently in clinical use, with two benzyl rings separated by an alkyl linker that contains a nitrogen. However, a detailed investigation of the structural similarities of 9 as compared with anastrozole and letrozole was not possible during the course of the present study.

6β-Hydroxystigmasta-4-en-3-one (5) was found to be weakly active in the cell-based AI bioassay. Interestingly, compound 5, as well as compounds 9 and 12, were not active in the enzyme-based AI assay, perhaps indicating that they are acting through indirect regulation or modulation of aromatase expression rather than through direct aromatase inhibition (Chen et al., 2001; Díaz-Cruz et al., 2005; Yang and Chen, 1999).

Brassaiopsis glomerulata has been reported to have various ethnobotanical uses, as mentioned earlier. The past history of medicinal use by human populations of B. glomerulata may be indicative of being safe when consumed. The strong aromatase inhibition of the hexane extract of B. glomerulata in both enzyme- and cell-based assays, coupled with the possibility of a favorable safety profile, may point to the potential for use of B. glomerulata for the chemoprevention of breast cancer. Further investigations of B. glomerulata are needed, including a recollection and subsequent bioassay-guided compound isolation, as well as further biological studies on the mechanism of aromatase inhibition and in vivo testing.

3. Experimental

3.1 General experimental procedures

Enantiomerically pure standards L-phenylalaninol (L-phe-ol), D-phenylalaninol (D-phe-ol), L-phenylalanine (L-phe), and D-phenylalanine (D-phe) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Nα-(2,4-dinitro-5-fluorophenyl)-L-alaninamide (L-FDAA, Marfey’s reagent) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HPLC of Marfey’s derivatives was performed using two Waters 515 pumps and a Waters 2487 dual wavelength (Waters, Milford, MA). A preparative Waters SunFire™ C18 column (19 × 150 mm) was used for fractionation, while an analytical Waters SunFire™ C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm) was used for Marfey’s analysis. Solvents were HPLC grade and used without further purification. Radiolabeled [1β-3H]androst-4-ene-3,17-dione, scintillation cocktail 3a70B, SK-BR-3 human breast cancer cells were obtained as described previously (Brueggemeier et al., 2005). Radioactivity was counted on an LS6800 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

3.2. Plant Material

The leaves of Brassaiopsis glomerulata (Blume) Regel were collected by Dr. Soedarsono Riswan, Herbarium Bogoriense, Bogor, Indonesia, in 1996 (collection number BK-35). Plant material was stored at ambient temperature at the UIC Pharmacognosy Field Station in Downers Grove, Illinois until used for the present study. A voucher specimen (accession number P1750) has been deposited at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois.

3.3. Extraction and isolation

Air-dried leaves of B. glomerulata (1.1 kg) were ground and extracted with methanol overnight (3 × 3 L). The macerate was concentrated in vacuo (46.1 g) and partitioned to afford a petroleum ether extract (11.6 g), an ethyl acetate extract (8.2 g), and an aqueous extract (13.3 g). The petroleum ether extract was fractionated using Si gel vacuum liquid chromatography (Aldrich, Si gel 60, 63–200 mesh, 8.5 × 18 cm) using 100% petroleum ether, followed by a gradient of increasing polarity of petroleum ether-ethyl acetate, followed, in turn, by ethyl acetate-methanol. The column was then washed with 100% methanol. Altogether, ten pooled fractions (F005–F014) were collected. Compound 1 (3.6 mg) was obtained as a precipitate from F006. A white solid precipitated from fraction F007, a mixture of two related compounds, and was chromatographed using silica gel (Aldrich, Si gel 60, 230–400 mesh, 4.5 × 46 cm), beginning with 8:1 hexane-ethyl acetate, followed by a gradient of increasing polarity, and washed with 100% methanol to afford purified stigmasterol (2, 2.2 mg) and purified spinasterol (3, 1.9 mg).

Fractions F008, F009, and F010 were all considered active in the noncellular assay and were combined based on similar TLC profiles (for a total of 3.1 g). F008–F010 was fractionated using Diaion HP-20 sorbent (Aldrich, 4.0 × 21 cm), eluted by 1:1 MeOH-H2O, 3:1 MeOH-H2O, 100% MeOH, 3:1 MeOH-acetone, 1:1 MeOH-acetone, and 100% acetone. Compound 6 (2.7 mg) was obtained as a white precipitate from the 100% MeOH fraction. The 3:1 MeOH-acetone fraction (1.9 g) was further fractionated (Aldrich, Si gel 60, 230–400 mesh, 2.5 × 45 cm), starting with 9:1 hexane-acetone and continuing with increasing polarity until washing with 100% acetone, followed by 100% methanol. Five pooled fractions were obtained with the 3:2 hexane-acetone fraction (0.09 g) being further fractionated by preparative reversed-phase HPLC (92% methanol in water, 8 mL/min, monitoring at 238 and 275 nm), yielding 4 (1.1 mg, tR 36.8 min) and 5 (0.4 mg, tR 50.4 min).

The ethyl acetate extract (8.1 g) was fractionated using Si gel vacuum liquid chromatography (Aldrich, Si gel 60, 63–200 mesh, 8.5 × 19 cm), beginning with 100 % petroleum ether, followed by a gradient of petroleum ether-ethyl acetate, ethyl acetate-methanol, and 100% methanol. Altogether 17 pooled fractions (F029–F045) were collected. Compound 7 (19.8 mg) precipitated from fraction F034. F031 (0.01 g) was subjected to further fractionation (Aldrich, Si gel 60, 230–400 mesh, 1.0 × 15 cm) using an isocratic 5:1 hexane-ethyl acetate system, yielding pure compound 10 (0.1 mg). Fractions F032 and F033 were combined (0.1 g) and fractionated by preparative reversed-phase HPLC separations (60 % water in acetonitrile, 7 mL/min, monitoring at 220 and 254 nm) to afford 11 (0.9 mg, tR 11.5 min).

Fraction F034 (0.3 g) was chromatographed using Sephadex LH-20 gel (Aldrich, 2.5 × 76 cm) in methanol, to afford 12 pooled fractions (F055–F066). The combination of F057–F058 (0.1 g) was worked up by preparative reversed-phase HPLC separations (7 mL/min, monitoring at 220 and 254 nm). The solvent conditions for separation involved a 85:15 water-acetonitrile system for 10 min followed by a 60 min gradient to 1:9 water-acetonitrile, to afford compounds 12 (3.5 mg, tR 29.5 min), 9 (0.8 mg, tR 46.1 min), and 8 (3.7 mg, tR 50.8 min). Fractions F059 and F060 were combined (0.02 g) and separated using preparative reversed-phase HPLC separations (7 mL/min, monitoring at 220 and 254 nm). The solvent conditions for separation involved a 85:15 water-acetonitrile system for 15 min followed by a 45 min gradient to 1:9 water-acetonitrile, to afford compound 13 (1.9 mg, tR 24.2 min).

3.4. Marfey’s analysis

Samples of 7–9 were independently hydrolyzed at 110 °C with 6 N HCl for 1 h (Fujii et al., 2002). Hydrolysates were dried and Marfey’s derivatives were prepared following a published procedure (Fujii et al., 2002). The dried hydrolysates of 7–9, as well as the standards L-phe-ol, D-phe-ol, L-phe, and D-phe, were each dissolved in 100 μL of water. A 1 M sodium bicarbonate solution was prepared and 40 μL were added to each sample. A 1% w/v solution of L-FDAA in acetone was prepared and 100 μL was added to each vial. Each vial was then vortexed and incubated at 40 °C for 1 h. To quench reactions, 40 μL of 1 N HCl were added. Each of the Marfey’s derivatives of the hydrolysates and standards were separately analyzed by HPLC. All four Marfey’s derivatives of the standards were then analyzed concurrently. Each Marfey’s derivative of the hydrolysates was then analyzed concurrently with each Marfey’s derivative of the standards. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by HPLC using a five-minute isocratic mobile phase of 30% CH3CN/70% 0.01 N aqueous TFA followed by a gradient elution profile to 90% CH3CN/10% 0.01 N aqueous TFA over 60 min at a flow of 1 mL/min, monitoring at 340 nm and 256 nm.

3.5. Noncellular, enzyme-based aromatase bioassay

This assay was performed as described in earlier publications (Balunas et al., 2006; Kellis and Vickery, 1987; O’Reilly et al., 1995). Human placental microsomes were obtained from human term placentas that were processed at 4 °C immediately after delivery from The Ohio State University Medical Center [OSU Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol number 2002H0105, last approved in December 2006]. Extracts and compounds were originally screened at 20 μg/mL in DMSO using a noncellular microsomal radiometric aromatase assay. Samples [extracts or compounds, DMSO as negative control, or 50 μM (±)-aminoglutethimide (AG) as positive control] were tested in triplicate. Each reaction mixture included sample, 100 nM [1β-3H]androst-4-ene-3,17-dione (400,000 – 450,000 dpm), 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 5% propylene glycol, and an NADPH regenerating system (containing 2.85 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 1.8 mM NADP+, and 1.5 units glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). Microsomal aromatase (50 μg) was added to initiate the reactions, which were then incubated in a shaking water bath at 37 °C, and quenched after 15 min using 2 mL CHCl3. An aliquot of the aqueous layer was then added to 3a70B scintillation cocktail for quantitation of the formation of 3H2O. Percent control activity (PCA) was determined as previously described (Balunas et al., 2006; Kellis and Vickery, 1987; O’Reilly et al., 1995).

3.6. Cell-based aromatase bioassay

Samples found to be active using the noncellular assay were further tested at various concentrations in SK-BR-3 human breast cancer cells that overexpress aromatase, using a previously described method (Balunas et al., 2006; Natarajan et al., 1994; Richards and Brueggemeier, 2003). Cells were treated in triplicate with samples or 0.1% DMSO (negative control) or 10 nM letrozole (positive control). Results are initially determined as picomoles of 3H2O formed per hour incubation per million live cells (pmol/h/106 cells), with PCA calculated by comparison with the negative control, DMSO.

Fig. 1.

Compounds isolated from Brassaiopsis glomerulata.

Fig. 2.

Percent control activity (PCA) at 20 μg/mL for compounds 1–13 isolated from Brassaiopsis glomerulata in the noncellular, enzyme-based aromatase bioassay and in SK-BR-3 hormone-independent human breast cancer cells that overexpress aromatase (DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide, blank/negative control; AG = aminoglutethimide, positive control in noncellular assay, 50 μM; LET = letrozole, positive control in cell-based assay, 10 nM). Each bar represents the mean and standard error of three replicates, with statistically significant differences indicated in the non-cellular assay by different numbers of stars and in the cell-based assay by different letters (P < 0.0001).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant P01 CA48112 (P.I., J.M. Pezzuto), R01 CA73698 (P.I., R.W. Brueggemeier), The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (OSUCCC) Breast Cancer Research Fund (to R.W. Brueggemeier), OSUCCC Molecular Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention Program (to A.D. Kinghorn), and a Dean’s Scholar Award and University Fellowship from the University of Illinois at Chicago (to M.J. Balunas).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ayyad SN. A new cytotoxic stigmastane steroid from Pistia stratiotes. Pharmazie. 2002;57:212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balunas MJ, Su B, Landini S, Brueggemeier RW, Kinghorn AD. Interference by naturally occurring fatty acids in a noncellular enzyme-based aromatase bioassay. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:700–703. doi: 10.1021/np050513p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banni S, Contini MS, Angioni E, DeLana M, Dessi MA, Melis MP, Carta G, Corongiu FP. A novel approach to study linoleic acid autoxidation: Importance of simultaneous detection of the substrate and its derivative oxidation products. Free Radic Res. 1996;25:43–53. doi: 10.3109/10715769609145655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd LC, King MF, Sheldon B. A rapid method for determining the oxidation of n-3 fatty acids. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1992;69:325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemeier RW. Update on the use of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:1919–1930. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.14.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemeier RW, Diaz-Cruz ES, Li PK, Sugimoto Y, Lin YC, Shapiro CL. Translational studies on aromatase, cyclooxygenases, and enzyme inhibitors in breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;95:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan CA, de Heluani CS, Kotowicz C, Gedris TE, Herz W. A linear sesterterpene, two squalene derivatives and two peptide derivatives from Croton hieronymi. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:625–629. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changkija S. Folk medicinal plants of the Nagas in India. Asian Folkl Stud. 1999;58:205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SU, Zhou DJ, Yang C, Okubo T, Kinoshita Y, Yu B, Kao YC, Itoh T. Modulation of aromatase expression in human breast tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cruz ES, Shapiro CL, Brueggemeier RW. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress aromatase expression and activity in breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2563–2570. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgo P, Kover KE. Gradient enhanced selective experiments in the 1H NMR chemical shift assignment of the skeleton and side-chain resonances of stigmasterol, a phytosterol derivative. Steroids. 2004;69:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii K, Yahashi Y, Nakano T, Imanishi S, Baldia SF, Harada K. Simultaneous detection and determination of the absolute configuration of thiazole-containing amino acids in a peptide. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6873–6879. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SR, Dowsett M. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: lessons from the laboratory. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:821–831. doi: 10.1038/nrc1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis JT, Jr, Vickery LE. Purification and characterization of human placental aromatase cytochrome P-450. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4413–4420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn AD, Su BN, Jang DS, Chang LC, Lee D, Gu JQ, Carcache-Blanco EJ, Pawlus AD, Lee SK, Park EJ, Cuendet M, Gills JJ, Bhat K, Park HS, Mata-Greenwood E, Song LL, Jang M, Pezzuto JM. Natural inhibitors of carcinogenesis. Planta Med. 2004;70:691–705. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima H, Sato N, Hatano A, Ogura H. Sterol glucosides from Prunella vulgaris. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2351–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Kontiza I, Abatis D, Malakate K, Vagias C, Roussis V. 3-Keto steroids from the marine organisms Dendrophyllia cornigera and Cymodocea nodosa. Steroids. 2006;71:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang G, Mitova MI, Cole ALJ, Din LB, Vikineswary S, Abdullah N, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. Pterulamides I–VI, linear peptides from a Malaysian Pterula sp. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1389–1393. doi: 10.1021/np0600245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Oe T, Arora JS, Blair IA. Analysis of FeII-mediated decomposition of a linoleic acid-derived lipid hydroperoxide by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:661–668. doi: 10.1002/jms.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JI, Du MT. Rapid, one-pot conversion of aryl fluorides into phenols with 2-butyn-1-ol and potassium t-butoxide in DMSO. Synth Commun. 2002;32:1401–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Li WR, Yo YC, Lin YS. Efficient one-pot formation of amides from benzyl carbamates: Application to solid-phase synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8867–8875. [Google Scholar]

- Mitova MI, Stuart BG, Cao GH, Blunt JW, Cole ALJ, Munro MHG. Chrysosporide, a cyclic pentapeptide from a New Zealand sample of the fungus Sepedonium chrysospermum. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1481–1484. doi: 10.1021/np060137o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Khlebnikov V. Carotenoids and degraded carotenoids, 8. Synthesis of (+)-dihydroactinidiolide, (+)-actinidiolide and (−)-actinidiolide, (+)-loliolide and (−)-loliolide as well as (+)-epiloliolide and (−)-epiloliolide. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1993:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan N, Shambaugh GE, 3rd, Elseth KM, Haines GK, Radosevich JA. Adaptation of the diphenylamine (DPA) assay to a 96-well plate tissue culture format and comparison with the MTT assay. Biotechniques. 1994;17:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly JM, Li N, Duax WL, Brueggemeier RW. Synthesis, structure elucidation, and biochemical evaluation of 7α- and 7β-arylaliphatic-substituted androst-4-ene-3,17-diones as inhibitors of aromatase. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2842–2850. doi: 10.1021/jm00015a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsewak RS, Nair MG, Murugesan S, Mattson WJ, Zasada J. Insecticidal fatty acids and triglycerides from Dirca palustris. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5852–5856. doi: 10.1021/jf010806y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi BN, Murphy PT, Lidgard RO, Warren RG, Wells RJ. C-18 terpenoid metabolites of the brown alga Cystophora moniliformis. Aust J Chem. 1982;35:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Regel E. Brassaiopsis glomerulata Blume (t.411) Araliaceae Gartenflora. 1863;12:275–276. [Google Scholar]

- Richards JA, Brueggemeier RW. Prostaglandin E2 regulates aromatase activity and expression in human adipose stromal cells via two distinct receptor subtypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2810–2816. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebacher W, Simic N, Weis R, Saf R, Kunert O. Complete assignments of H-1 and C-13 NMR resonances of oleanolic acid, 18α-oleanolic acid, ursolic acid and their 11-oxo derivatives. Magn Reson Chem. 2003;41:636–638. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Zeng N, Jia M, Zhang Y, Wei Y, Ma Y. Experimental studies on anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and diuretic effects of several species of Tongcao and Xiao-tongcao. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 1998;23:687–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kiem P, Dat NT, Van Minh C, Lee JJ, Kim YH. Lupane triterpenes from the leaves of Brassaiopsis glomerulata. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26:594–596. doi: 10.1007/BF02976706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandji J, Tillequin F, Mulholland DA, Wansi JD, Fomum TZ, Fuendjiep V, Libot F, Tsabang N. Fatty acid esters of triterpenoids and steroid glycosides from Gambeya africana. Planta Med. 2002;68:822–826. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YQ, Li L, You XL, Bian BL, Liang XM, Wang YT. A new compound from Gastrodia elata Blume. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2002;4:73–79. doi: 10.1080/10286020290019730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Chen S. Two organochlorine pesticides, toxaphene and chlordane, are antagonists for estrogen-related receptor α-1 orphan receptor. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4519–4524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]