Abstract

Progress in learning about underlying carotenoid bioactivity mechanisms has been limited due to lack of commercially available radiolabeled lycopene (LYC), phytoene (PE), and phytofluene (PF). Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. VFNT cherry) cell cultures have been treated to produce [14C]-PE and PF but with relatively low yields. To increase carotenoid production, two bleaching herbicides were administered during the culture incubation, 2-(4-chlorophenyl-thio) triethylamine and norflurazon separately or in combination to produce varying ratios of PE, PF, and LYC. Treatment with both herbicides resulted in optimal production of all three carotenoids. Subsequently, cultures were incubated in [14C] sucrose-containing media to produce labeled LYC, PE, and PF. Adding [14C] sucrose on day 1 of the 14-d culture incubation cycle to norflurazon-treated cultures led to a small increase in labeling efficiency compared to adding it on day 7. Improved culture conditions efficiently provided sufficient 14C-carotenoids for future cell culture and animal metabolic tracking studies.

Keywords: Solanum lycopersicum, bleaching herbicide, radiolabeling, metabolic tracer, cell culture, lycopene, phytoene, phytofluene

I. Introduction

A substantial body of epidemiological evidence suggests that tomato consumption is associated with a decreased risk of a variety of cancers including lung, stomach, and prostate with the strongest evidence for prostate cancer (1, 2). Tomatoes provide many nutrients to the diet including carotenoids which are 40 carbon, pigmented compounds that range from colorless to red, yellow, and orange (3). The most predominant carotenoid in red tomatoes is lycopene (LYC), followed in concentration by phytoene (PE), phytofluene (PF), beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, and lutein and zeaxanthin (3). These prominent carotenoids are believed to be critical to the efficacy of tomatoes to prevent disease, however the majority of disease prevention research focuses on LYC alone.

To best understand the underlying mechanisms of prostate cancer risk reduction afforded by tomato consumption, a number of investigations into the bioavailability, biodistribution, and metabolism of tomato carotenoids have been undertaken (4–9). Further progress on mechanisms has been hampered because there is no commercial source for isotopically labeled PE, PF, or LYC.

Plant cell culture is a useful method for radiolabeled bioactive compound production offering several advantages compared to whole plant biolabeling, such as the ability to target selected tissue sources based on desired secondary metabolite profiles, shortened culture periods, relative ease of extraction, and uniform exposure to isotopically labeled carbon sources in the media (10–14).

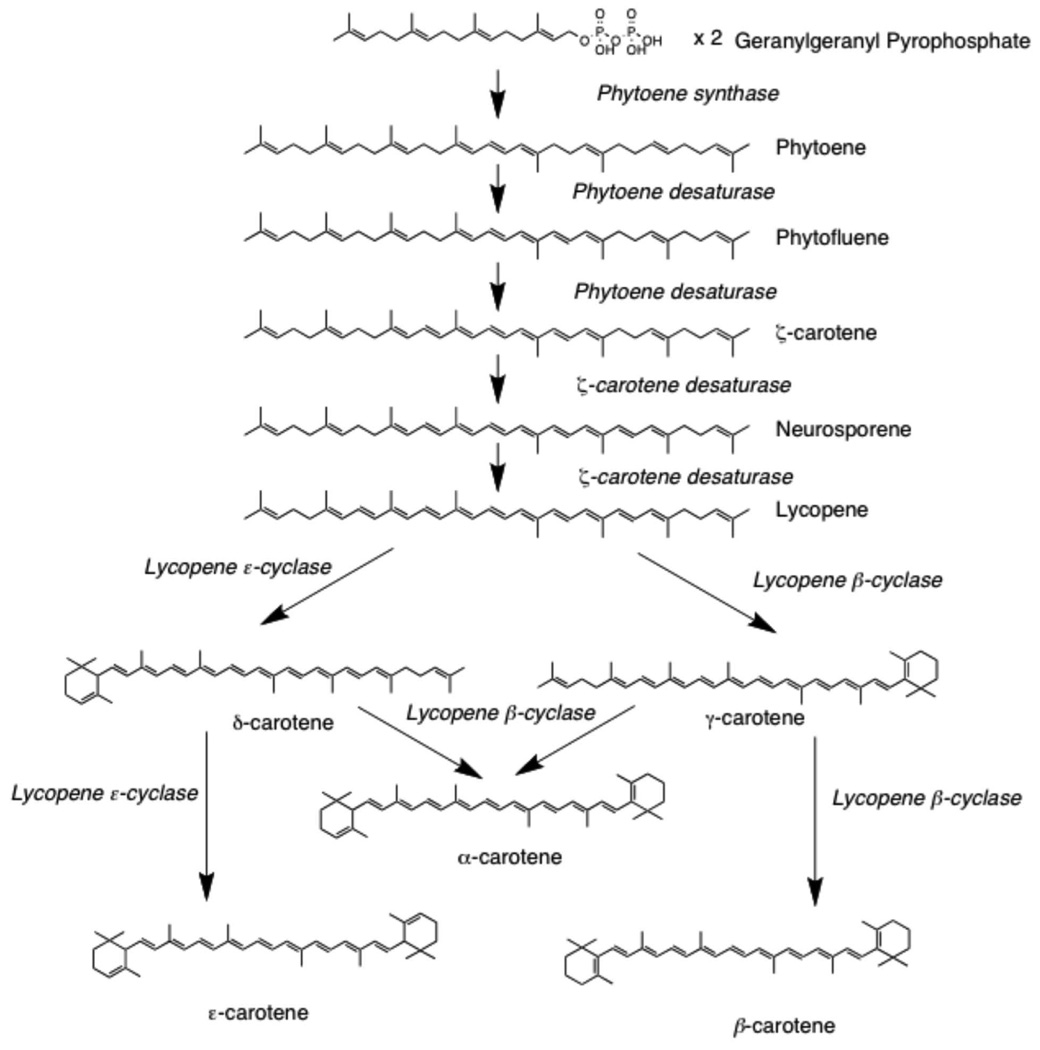

In order to enhance in vitro carotenogenesis, bleaching herbicides have been utilized (14–17). Bleaching herbicides interrupt normal carotenogenesis either in vivo or in vitro, causing a fatal loss of photoprotection in the plant, leading to chlorophyll destruction upon light exposure (18). Previously, the bleaching herbicide norflurazon (NORF) was utilized to promote 14C-PE and PF accumulation in tomato cv. VFNT cherry cells, and the tracers were used for in vitro investigation of their uptake into prostate cancer cells. NORF is a phytoene desaturase (PDS) inhibitor, preventing conversion of PE, the first carotenoid in carotenogenesis, to PF (Figure 1) (15). Further, NORF causes a concomitant increase in PDS expression as well as a modest increase in phytoene synthase (PSY) expression, likely due to increased photooxidative stress or a lack of end-product regulation of carotenogenesis (Figure 1) (19).

Figure 1.

Tomato carotenoid biosynthetic pathway.

The bleaching herbicide 2-(4-chlorophenyl-thio) triethylamine (CPTA) has also been widely used in in vitro tomato research for the study of LYC accumulation and ripening mechanisms (16, 17, 20). CPTA inhibits lycopene cyclase (LCYC) causing LYC accumulation and a lack of downstream cyclic carotenoid production (Figure 1). Because CPTA seems to cause an overall increase in carotenogenesis, it was hypothesized that CPTA, in combination with the previously used NORF treatment, would yield greater PE and PF than NORF alone.

Another goal of this study was to enhance the radiolabeling efficiency of targeted carotenoids. Plant secondary metabolites are produced during the growth plateau phase of cell culturing (21). Therefore, examining different [14C]-sucrose-dosing times during the growth cycle may lead to targeted enrichment of carotenoids. The timing effect of adding [14C]-sucrose with NORF on 14C-enrichment of PE and PF was examined.

Materials and Methods

Tomato Cell Suspension Cultures and Herbicide Treatments

Suspension cultures were initiated and maintained according to a previously-described method using tomato cv. VFNT cherry calyces for callus initiation (17). Friable callus was transferred from agar-solidified media to solution media and subsequently transferred to fresh media every two weeks using published media formulations and culturing methods (14).

To alter the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, thus optimizing specific carotenoid accumulation, cell cultures were treated with herbicides. Eighty mL of fresh media, containing indole-3-acetic acid (5 mg/L) and all-trans-zeatin (2 mg/L) growth regulators in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, was inoculated with 8 mL spent media and 4 mL packed cells. A 2×2 factorial design for the herbicide treatment experiments was used. Based on previous work, herbicide treatments were as follows: cultures were either aseptically treated on day 1 with filter-sterilized aqueous CPTA (74.5 mg/L media, a gift from Betty K. Ishida, USDA ARS, St. Albany, CA) on day 7 with filter-sterilized NORF (0.75 mg/L media, Syngenta, Greensboro, NC) dissolved in DMSO, with both herbicides on respective days, or with neither (control treatment) (14, 17). Subsequently, for PE, PF, and LYC radiolabeling, cultures were treated with both CPTA and NORF, and for [14C]-sucrose dose timing experiments cultures were treated with NORF only.

14C Radiolabeling of Herbicide-treated Suspension Cultures

To safely and efficiently 14C label carotenoids from tomato cell suspension cultures, cells were subcultured into a reduced volume of media (72 mL), and 8 mL fresh media containing 0.45 mCi/mL uniformly labeled [14C]-sucrose (10 mCi/mmol) (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) was added on either day 1 or day 7 of the 14-d growth period. The final radiolabel specific activity was 45 uCi/mL fresh media. Cultures were grown in a previously described enclosed Plexiglass radiolabeling chamber equipped with NaOH traps and an air-flushing system to prevent escape of 14CO2 from the growth chamber (12). The growth environment was controlled; rotary shakers were set to 160 rpm, growing temperature was 22°C, cultures were grown in darkness, and chamber air was flushed four times per day.

In CPTA-treated tomato cv. VFNT cherry cells, the majority of LYC is produced after the end of growth, and continues to increase in concentration up to 32 days after inoculation (16). Preliminary studies (data not shown), indicated that when tomato cv. VFNT cherry cultures treated with CPTA were harvested at 14, 21, and 28 days, LYC concentration increased over time; however, harvest mass drastically decreased, resulting in overall lower LYC yield at 21 and 28 d compared to a 14-d culture duration. For this reason a 14-d growth period was selected for further studies. Because NORF is added on day 7 (as opposed to day 1 in the case of CPTA), carotenogenesis in NORF-only treated cultures is very low during the first 7-d of the 14-d growth period. It was hypothesized that adding [14C]-sucrose on day 7 of the growth cycle (rather than initially on day 1) would lead to increased 14C-enrichment of PE and PF in NORF treated cultures.

Three, 14-d long [14C]-radiolabeling runs were conducted. The first examined the carotenoid labeling efficiency of CPTA and NORF-treated cells with [14C]-sucrose (12 flasks) provided on day 1. The next two runs (6 flasks/run) compared the effect of [14C]-sucrose dose timing (day 1 vs. 7) on PE and PF labeling efficiency in NORF-only treated cultures.

Suspension Culture Harvest

Labeled and non-labeled cultures were harvested on day 14 using Whatman #4 filters with a Büchner funnel over a vacuum. Filtration was ended and cultures were collected and weighed when no further liquid was expressed from the funnel for 30 s. Samples of each flask (~1g) were collected for further carotenoid and 14C scintillation analysis and the remaining cells were combined for carotenoid preparatory extraction and isolation for future cell culture and animal metabolic studies. When cultures were collected from the radiolabeling chamber, samples were also taken from the NaOH traps and spent media for determination of cell labeling efficiency.

Carotenoid Extraction of Tomato Cells

Labeled and non-labeled carotenoids were extracted from frozen tomato cells as previously described (14) by using 0.25–1.0 g cells suspended in 5 mL ethanol with 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene and homogenization for 20 s using a tissue homogenizer (Kinematic PCU1; Brinkmann, Westbury, NY). The cells were heated (60°C) and vortexed every 10 min for 30 min. Samples were then placed on ice, 2 mL HPLC grade water and 6 mL hexane were added, samples were vortexed ~30 s, and then centrifuged 10 min at 4 °C to separate solvent layers. The carotenoid-containing hexane phase was removed and the hexane extraction and centrifugation was repeated two more times. Reserved hexane was dried under educed pressure (Speedvac concentrator, model AS160, Savant, Milford, MA) and stored under argon at −80°C for no longer than 48 hrs before analysis.

High Pressure Liquid Chromatography-Photodiode Array (HPLC-PDA) Carotenoid Analysis

Samples were analyzed using a HPLC-PDA system and methods for carotenoid separation using a C30 reverse-phase column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 3 um, YMC, Wilmington, NC), with mobile phases consisting of methanol, methyl-tert butyl ether, and ammonium acetate (12) for the quantification and isolation of PE and PF from tomato cell suspension cultures (14). All carotenoids were identified and quantified through comparison to UV spectra, retention times and standard curves of analytical standards of PE, PF, LYC, BC, LUT (gifts from Hansgeorg Ernst, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany), zeta-carotene (ZC), and delta-carotene (DC) (Carotenature, Lupsingen, Switzerland) with published extinction coefficients (22).

Radiolabeled PE, PF, and LYC were first separated using a method developed by Craft (23) on an HPLC-UV/VIS Varian Prostar dual wavelength detector with Dynamax, SD-200 pumps (Varian, Palo Alto, CA), quantified, and collected. Roughly equivalent amounts of carotenoids (generally between 100–200 ng) were then repurified using the method described earlier using a C30 column and the HPLC-PDA system. Carotenoid fractions were collected according to characteristic retention times, quantified based on authentic standards, and solvents were removed under argon. Biosafe II liquid scintillation cocktail (20 mL) (Research Products International Corp., Mount Prospect, IL) was first added to the dried carotenoid fractions, held in darkness overnight, and analyzed for 14C content using a Beckman liquid scintillation counter, model LS-6500 (Bakersfield, CA).

Analysis of 14C Accumulation in Samples and System Labeling Efficiency

Known amounts of labeled carotenoids, media, or NaOH traps were added to BioSafe II (20 mL). Tomato cells (0.05 g) were solubilized in glass scintillation vials using 1 mL TS-2 Tissue Solubilizer (Research Products International Corp., Mount Prospect, IL) for 6 hr at 50°C with vigorous mixing by vortex every 30 min to ensure that all cells were dissolved. This mixture was bleached with 1 mL 30% H2O2 and neutralized with 0.5 mL glacial acetic acid. Samples were held at room temperature for 45 min, scintillation cocktail was added, and then kept in darkness overnight; 14C content was analyzed by scintillation counting the following day.

Statistical Analysis

Treatment group differences were determined by using ANOVA procedures when the assumptions of ANOVA were met, otherwise the Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were used to evaluate group differences using the statistical analysis software SAS v. 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Herbicide-Induced Carotenoid Accumulation

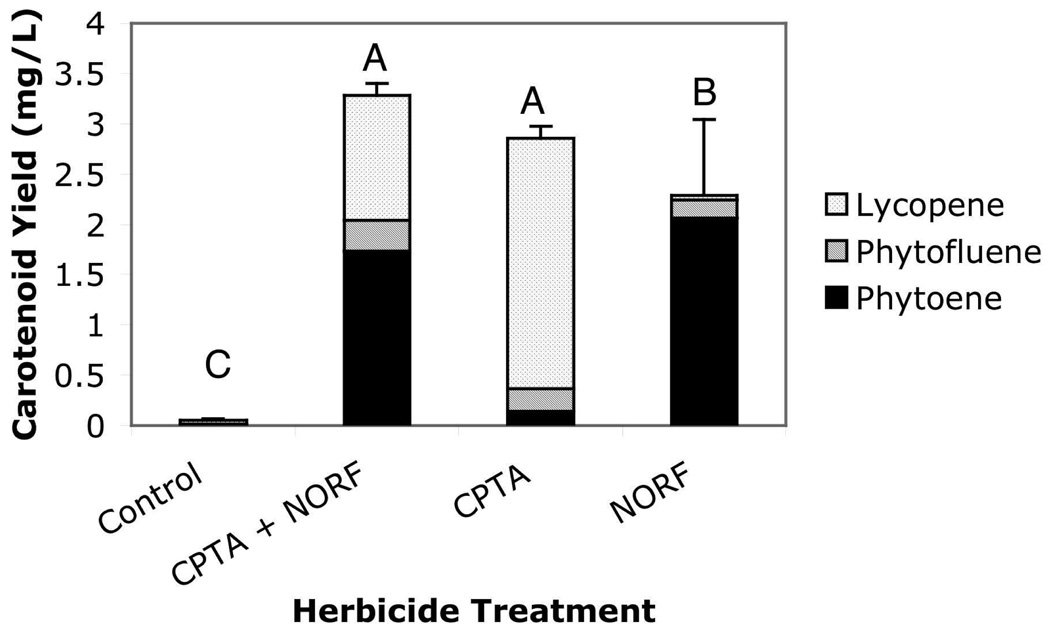

Herbicide treatments did not affect cell biomass, where the average yield for all cultures was 153 ± 11 (standard error of the mean, SEM) g of tomato cells/L (n=12). Carotenoid yields, however, were enhanced by herbicide treatments. CPTA alone or in combination with NORF resulted in the greatest total carotenoid (combined LYC, PE, and PF) yields (2.86 and 3.28 mg/L, respectively) followed by the NORF alone treatment (2.29 mg/L). Control cultures had substantially lower total carotenoid yield (0.017 mg/L) (Figure 2). When herbicide treatments were compared, the combination treatment produced significantly more LYC than the NORF treatment (1.24 vs 0.04 mg/L; p= 0.05) and more PE than the CPTA treatment (1.74 vs. 0.14 mg/L; p=0.05). CPTA treatment led to significantly greater LYC accumulation (2.49 mg/L) than NORF or control treatments (0.04 and 0.04 mg/L; p<0.001 and p=0.02). NORF caused greater PE and PF accumulation (2.06 and 0.18 mg/L, respectively) than control (0 and 0.01 mg/L, respectively; p=0.02 and 0.02) and more PE than CPTA treatment (0.14 mg/L; p=0.034) (Figure 2). The effects of herbicide treatments on other minor, quantified carotenoids (LUT, BC, DC, and ZC) are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Effects of herbicide treatments on production of three carotenoids from tomato cv. VFNT cherry cell culture grown for 14-d. See method section for details of treatments. Bars with different letters are significantly different according to Kruskal-Wallis test (alpha = 0.05). Error bars represent SEM for combined PE, PF, and LYC (n=3 trials, analyzed 3 flasks/trial in duplicate).

Table 1.

Yield of minor carotenoids following herbicide treatment of tomato cv. VFNT cherry cell cultures after a 14-d growth period. Data are averages of 2 trials, each analyzing 3 flasks, in duplicate.

| (ug/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | β-carotene | ζ-carotene | Lutein | δ-carotene |

| Control | 16.3 | 0.709 | 16.6 | 0.00 |

| CPTA | 9.17 | 1.12 | 7.53 | 0.00 |

| NORF | 7.64 | 20.7 | 13.5 | 10.2 |

| NORF and CPTA | 7.17 | 26.8 | 10.1 | 1.64 |

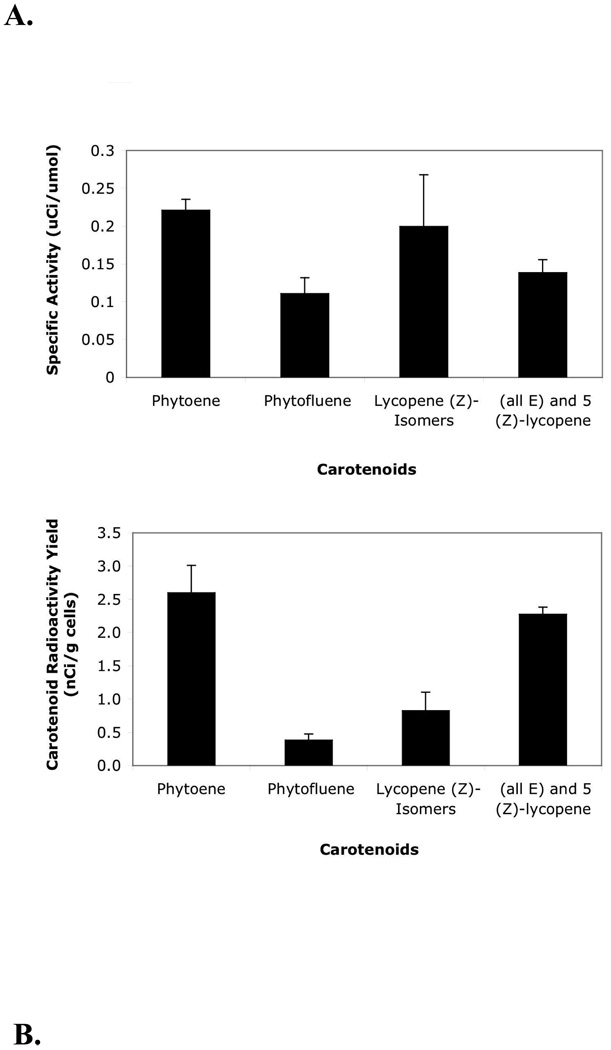

[14C]-Carotenoid Yields from Tomato Cell Cultures Treated with CPTA and NORF

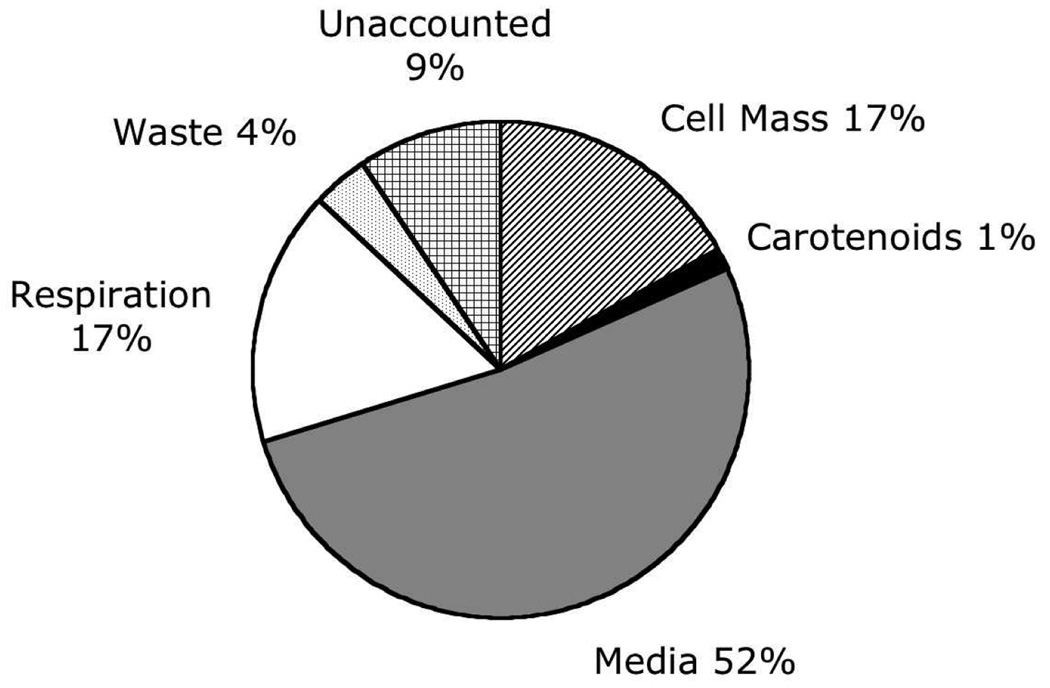

Cultures treated with CPTA (day 1) and NORF (day 7) and dosed with [14C]-sucrose (day 1) were harvested and weighed after vacuum filtration, and average mass yield was 151 ± 2 (SEM) g/L (n=12). Upon harvest, samples of culture media, NaOH traps, and system clean-up rinse water analyzed by scintillation counting indicated 52, 17, and 4% of the initial [14C]-sucrose dose were retained in these system compartments. Eighteen percent of the initial 14C dose accumulated in tomato cells and an estimated 0.02% was deposited in combined PE, PF, and LYC. The remaining 9% of the initial [14C]-sucrose was likely distributed throughout all experimental compartments (Figure 3). The specific activity of the carotenoids analyzed ranged from 0.11–0.22 uCi/umol (Figure 4A). Phytoene was the most abundant source of radiolabeled carotenoid (2.6 nCi/g cells) followed by all-(E)- and 5-(Z)-LYC, other LYC (Z)-isomers, and PF (2.3, 0.8, and 0.4 nCi/g cells, respectively) (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

Percent recovery of 14C sucrose provided on day 1 of a 14-d growth period to tomato cell cultures treated with CPTA on day 1 and NORF on day 7.

Figure 4.

Carotenoid specific activity (A) and radioactivity yield (B) of carotenoids from CPTA and NORF treated cell cultures. [14C]-sucrose was provided on day 1 of a 14-d growth period. Error bars represent standard error of the mean, n=3 culture flasks analyzed in duplicate for each carotenoid.

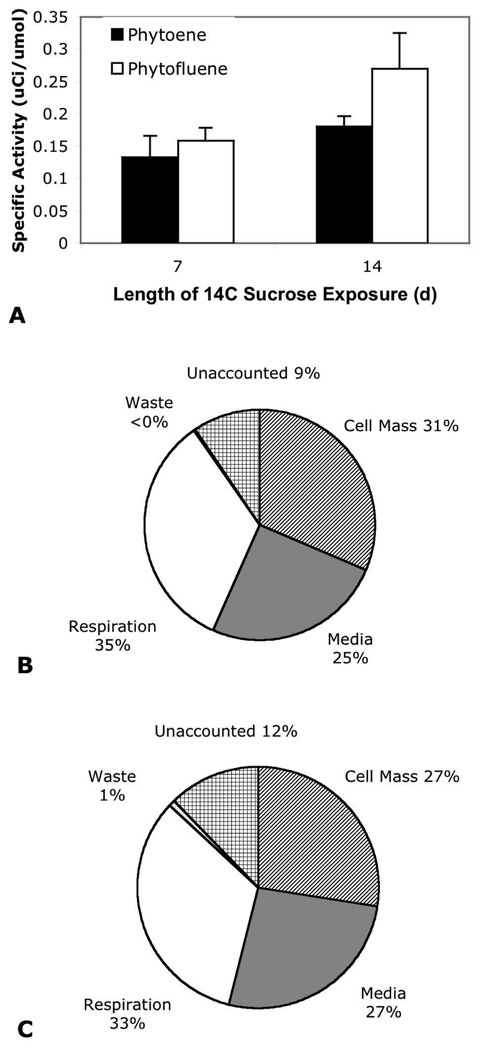

Labeling Efficiency of Cultures Dosed with [14C] Sucrose on Day 1 or Day 7

To examine the effect of [14C] sucrose dose administration timing on carotenoid enrichment, labeled sucrose was added to NORF-treated cell cultures on either day 1 or day 7 of the 14-d growth cycle. In this trial, cultures dosed on day 1 yielded 167 ± 3 (SEM) g/L (n=6) fresh mass and cultures dosed on day 7 averaged 174 ± 2 (SEM) g/L (n=4). Dosing on day 1 vs. day 7 led to a small increase of 14C content in both PF and PE, causing a 69% and 38% increase in specific activities, respectively. Labeled carbon distribution throughout experimental compartments was similar between the two radiolabeling runs (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Carotenoid specific activity (A) and 14C distribution in compartments of cultures treated with [14C]-sucrose on day 1 (full growth period) (B) or day 7 of the growth period (day 7–14) (C).

Discussion

Experiments investigating the effect of CPTA and/or NORF on carotenoid content of tomato cell cultures revealed several key points: A.) all herbicide treatments increased total carotenoid content, B.) the combination treatment unexpectedly produced LYC even in the presence of NORF, C.) unexpected carotenoids were detected, and D.) unique mixtures of carotenoids were efficiently produced with each herbicide treatment. The use of successive CPTA (day 1) and NORF (day 7) treatments in a continuous growth cycle allows for the most robust production of a useful mixture of carotenoids for subsequent radiolabeling studies. In contrast, single herbicide treatments would be more effective in maximizing the yield of specific [14C]-labeled carotenoids.

Bleaching herbicides increase total carotenoid content in tomato, pepper, and daffodil plants as well as tomato cell cultures (14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 24–26). The results from the current study confirmed either or both herbicides led to a greater total carotenoid yield than untreated cultures (135–193 fold). For NORF treatment, this has been attributed to either an upregulation of the metabolic pathway to compensate for a lack of photoprotective carotenoids or increased photostability of carotenoid precursors compared to their downstream products with longer polyene chains (24). The findings from the current report support the first hypothesis, but not the second. In the current study work, cell culture experiments were carried out in darkness where photostability would not be a contributing factor in carotenoid accumulation. With regards to increased carotenoid accumulation in tomato cultures with CPTA treatment, this may occur because of an upregulation of carotenogenesis in response to decreased BC or its derivatives, which may normally feed-back inhibit upstream carotenogenic enzymes (27). This hypothesis has been supported by increased PSY, PDS, and LCYC mRNA expression and protein levels observed in carotenogenic daffodil flowers treated with CPTA (25).

Secondly, it was hypothesized that LYC biosynthesis would be blocked in cultures treated with CPTA and NORF in combination causing a substantial elevation of PE and PF accumulation compared to NORF alone. The results did not support this hypothesis, showing instead that the combined and CPTA alone treatments resulted in similar total major carotenoid content. Surprisingly, the combination-treated cells accumulated 37% of the amount of LYC as that found with the CPTA alone treatment. Tomato cell cultures treated with CPTA appear to synthesize LYC steadily throughout the growth period (17); thus the observed LYC was most likely produced in the first 7-d of the 14 growth period, while further LYC synthesis was most likely halted with NORF treatment on day 7.

In addition to detecting PE, PF, and LYC, we detected BC, DC, and LUT in small amounts (Table 1). This was surprising because CPTA is a LCYC inhibitor; however, the level of CPTA provided may have been less than that necessary for complete LCYC inhibition, or there may be an alternate pathway for carotenoid cyclization. Zeta-carotene accumulation increased in NORF-treated cells compared to control, which is also unexpected as NORF is a PDS inhibitor (Figure 1). Because PF was present at approximately 1/10 the amount of PE, and ZC was present at roughly 1/10 of PF, the chosen NORF dose caused inhibition of PDS, although it was incomplete.

Lastly, different herbicide treatments led to different mixtures of carotenoids. The combined herbicide treatment (NORF + CPTA) led to excellent production of all three tomato carotenoids of interest (Figure 2). This novel method of producing carotenoids was thus chosen for subsequent radiolabeling studies. Tailored mixtures, predominant in one or another of the target carotenoids, could be encouraged by further alterations of the herbicide treatment.

The current studies led to several improvements to the previously established carotenoid radiolabeling system (14). Previously, harvest yield obtained from tomato cv. VFNT cherry cell cultures was ~ 70 g/L while the average for the current experiments was nearly double (~ 165 g/L). This difference was likely due to adaptation of the cultures over time, in that the tomato suspension cultures had been continuously cultured over a period of 12–24 mo longer than the time of previous experimentation. Productivity differences between experiments could be responsible for the higher carotenoid yields and lower enrichments of the carotenoids, such that more 14C was channeled into other biosynthetic pathways than carotenogenesis. Between the 2 current experiments it was also observed different 14C distribution in the experimental compartments, which is likely attributed to later runs accumulating more cell mass (see Figure 3 & Figure 5). Contrary to the hypothesis, adding [14C]-sucrose later in the growth period did not significantly enhance the specific activity of PE and PF, but instead led to lower 14C enrichment. It is concluded that tomato cells should be grown with [14C]-sucrose for the full growth period, and that the combined CPTA and NORF herbicide treatment induces the production of all three major tomato carotenoids.

The methods described here for increasing total carotenoid yield, improving carotenoid profiles, and increasing carotenoid specific activity along with a recently improved tomato cell extraction protocol (28), enhance the efficient production of radiolabeled carotenoids. In addition, these results demonstrate that changing herbicide treatments can alter carotenoid profiles. For example, lowering the NORF dose could potentially reduce efficiency of PDS inhibition and allow for a greater accumulation of PF. One future direction of interest would be to use a high LYC producing tomato cell line to further increase overall carotenoid-producing potential. The methods described here could also be used for producing stable isotope labeled tracers for human metabolic research, using [13C]-glucose as the primary carbon source for the cultures.

Safety

All radiolabeled materials were handled according to the University of Illinois Division of Research Safety Radiation Safety Manual.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Betty Ishida (USDA), for the gift of CPTA, and Hansgeorg Ernst (BASF) for phytoene and phytofluene standards, Nicola Lancki and Mary Kim for assistance with plant cell culturing, Neal Craft and Chi-Hua Lu for helpful discussions on HPLC methodology, and Jessica Campbell for valuable ideas on experimental design. We are also grateful to the University of Illinois Jonathan Baldwin Turner Fellowship Program (College of ACES), and the NIH for funding this research (NIH/NCI CA 112649-01A1).

References

- 1.Giovannucci E. Tomatoes, tomato-based products, lycopene, and cancer: review of the epidemiologic literature. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999;91:317–331. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etminan M, Takkouche B, Caamano-Isorna F. The role of tomato products and lycopene in the prevention of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell JK, Canene-Adams K, Lindshield BL, Boileau TW, Clinton SK, Erdman JW., Jr Tomato phytochemicals and prostate cancer risk. J. Nutr. 2004;134:3486S–3492S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3486S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unlu NZ, Bohn T, Francis D, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. Carotenoid absorption in humans consuming tomato sauces obtained from tangerine or high-beta-carotene varieties of tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:1597–1603. doi: 10.1021/jf062337b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sicilia T, Bub A, Rechkemmer G, Kraemer K, Hoppe PP, Kulling SE. Novel lycopene metabolites are detectable in plasma of preruminant calves after lycopene supplementation. J. Nutr. 2005;135:2616–2621. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.11.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boileau TW, Boileau AC, Erdman JW., Jr Bioavailability of all-trans and cis-isomers of lycopene. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2002;227:914–919. doi: 10.1177/153537020222701012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paetau I, Khachik F, Brown ED, Beecher GR, Kramer TR, Chittams J, Clevidence BA. Chronic ingestion of lycopene-rich tomato juice or lycopene supplements significantly increases plasma concentrations of lycopene and related tomato carotenoids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998;68:1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell JK, Engelmann NJ, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Phytoene, phytofluene, and lycopene from tomato powder differentially accumulate in tissues of male Fisher 344 rats. Nutr Res. 2007;27:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaripheh S, Erdman JW., Jr The biodistribution of a single oral dose of [14C]-lycopene in rats prefed either a control or lycopene-enriched diet. J. Nutr. 2005;135:2212–2218. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.9.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitrac X, Krisa S, Decendit A, Vercauteren J, Nuhrich A, Monti JP, Deffieux G, Merillon JM. Carbon-14 biolabelling of wine polyphenols in Vitis vinifera cell suspension cultures. J. Biotechnol. 2002;95:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(01)00441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousef GG, Seigler DS, Grusak MA, Rogers RB, Knight CT, Kraft TF, Erdman JW, Jr, Lila MA. Biosynthesis and characterization of 14C-enriched flavonoid fractions from plant cell suspension cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:1138–1145. doi: 10.1021/jf035371o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grusak MA, Rogers RB, Yousef GG, Erdman JWJ, Lila MA. An enclosed-chamber labeling system for the safe 14C-enrichment of phytochemicals in plant cell suspension cultures. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 2004;40:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reppert A, Yousef GG, Rogers RB, Lila MA. Isolation of radiolabeled isoflavones from kudzu (Pueraria lobata) root cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:7860–7865. doi: 10.1021/jf801413z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell JK, Rogers RB, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Biosynthesis of 14C-phytoene from tomato cell suspension cultures (Lycopersicon esculentum) for utilization in prostate cancer cell culture studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:747–755. doi: 10.1021/jf0581269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bramley PM. Carotenoid biosynthesis: a target site for bleaching herbicides. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1994;22:625–629. doi: 10.1042/bst0220625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishida BK, Mahoney NE, Ling LC. Increased lycopene and flavor volatile production in tomato calyces and fruit cultured in vitro and the effect of 2-(4-chlorophenylthio)triethylamine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:4577–4582. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson GH, Mahoney NE, Goodman N, Pavlath AE. Regulation of lycopene formation in cell suspension culture of VFNT tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) by CPTA, growth regulators, sucrose, and temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 1995;46:667–673. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Windhovel U, Sandmann G, Boger P. Genetic engineering of resistance to bleaching herbicides affecting phytoene desaturase and lycopene cyclase in cyanobacterial carotenogenesis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1997;57:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano G, Bartley GE, Scolnik PA. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato development. Plant Cell. 1993;5:379–387. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fosket DE, Radin DN. Induction of carotenogenesis in cultured cells of Lycopersicon Esculentum cultivar Ep-7. Plant Sci. Lett. 1983;30:165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourgaud F, Gravot A, Milesi S, Gontier E. Production of plant secondary metabolites: A historical perspective. Plant Sci. 2001;161:839–851. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britton G. UV/Visible Spectroscopy. In: Britton G, Liaaen-Jensen S, Pfander H, editors. Carotenoids: Spectroscopy. Basel: Birkhauser; 1995. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craft NE. Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry. Anonymous: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2001. Chromatographic techniques for carotenoid separation; p. Unit F2.3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simkin AJ, Breitenbach J, Kuntz M, Sandmann G. In vitro and in situ inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis in Capsicum annuum by bleaching herbicides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:4676–4680. doi: 10.1021/jf0006426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Babili S, Hartung W, Kleinig H, Beyer P. CPTA modulates levels of carotenogenic proteins and their mRNAs and affects carotenoid and ABA content as well as chromoplast structure in Narcissus pseudonarcissus flowers. Plant Biol. 1999;1:607–612. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson DJ, Rahman FMM, Buckle KA, Lee TH. Chemical regulation of plastid development. II. Effect of CPTA on the ultrastructure and carotenoid composition of chromoplasts of Capsicum annuum cultivars. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1974;1:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corona V, Aracri B, Kosturkova G, Bartley GE, Pitto L, Giorgetti L, Scolnik PA, Giuliano G. Regulation of a carotenoid biosynthesis gene promoter during plant development. Plant J. 1996;9:505–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09040505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu CH, Engelmann NJ, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Optimization of lycopene extraction from tomato cell suspension culture by response surface methodology. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:7710–7714. doi: 10.1021/jf801029k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]