Abstract

In order to efficiently generate genetically engineered mouse (GEM) fetuses or neonates of a specified age range, researchers must develop strain-specific strategies, including reliable early pregnancy detection. The authors evaluated pregnancy indices (pregnancy rate, plug rate, pregnant plugged rate, first litter size and body weight) in two GEM breeding colonies: homozygous soluble epoxide hydrolase knockout (sEHKO) mice (n = 164 females) and L7-tau-green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice (n = 61 females). The goals of the study were to determine the most accurate early pregnancy indicator and to reliably and cost-effectively produce timed pregnant females that were between gestation days 16 and 18. The authors set up each timed mating by placing two naturally synchronized females with a male for 48 h. When males were present, personnel checked each female daily for a vaginal plug. They then weighed the females immediately, 1 week and 2 weeks after removing the males. In both sEHKO and GFP colonies, increases in body weight at 1 and 2 weeks after timed male exposure more reliably and consistently indicated pregnancy than did plug detection. Further evaluations and protocol refinements are planned based on litter size and litter number in these colonies.

Genetically engineered mice (GEMs) are useful animal models that contribute to our basic understanding of biology, gene function and disease prevention. GEMs also help researchers to evaluate the role of genetic defects in specific diseases and to develop new therapies.

Academic research departments and institutions are increasingly developing mouse breeding colony ‘cores’ and services to supply researchers with GEMs1. In addition to managing GEM breeding colonies, these cores can provide services such as timed matings of different strains of GEMs1. Investigators might need timed pregnant GEMs for primary tissue culture research or for age-specific fetal and neonatal studies. Early pregnancy detection allows investigators to know in advance how many timed pregnant mice will be available each week for experiments. Additionally, researchers can reuse non-pregnant females in timed mating protocols sooner, reducing experiment length and the number of females needed in a study.

Pregnancy indices such as plug formation, ease of plug detection, correlation of the presence of vaginal plugs with pregnancy and correlation of litter size with parity status (litter number) can vary among GEM strains. To improve early pregnancy detection and optimize the number of fetuses or neonates produced, researchers need to develop strain-specific timed pregnancy protocols. The objective of this study was two-fold. First, we evaluated pregnancy indices (pregnancy rate, plug rate, pregnant plugged rate, first litter size and body weight) in two GEM breeding colonies: homozygous soluble epoxide hydrolase knockout (sEHKO) mice (n = 164 females) and L7-tau-green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice (n = 61 females). We also sought to reliably and cost-effectively produce timed pregnant sEHKO and GFP females between gestation days 16 and 18.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The Oregon Health and Science University IACUC approved all aspects of the study. Mice were housed in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals2. Mice were housed in small static polycarbonate isolator (shoebox) cages (7.7 in × 12.17 in × 5.875 in; total floor space 67.6 in2; Thoren Caging Systems, Inc., Hazelton, PA) on sterile EcoFRESH bedding (Absorption Corp, Ferndale, WA). Mice were kept on a 12-h:12-h light: dark cycle in a temperature-controlled (20.0–22.2 °C) and humidity-controlled (30–70%) room. Cages were changed weekly. Mice had ad libitum access to food (Picolab Rodent Diet 5053, Purina Mills, LLC, St. Louis, MO) and drank municipal water that had been filtered twice through an automatic watering system (with final filtration occurring through a 5-μm filter).

The Department of Comparative Medicine at Oregon Health and Science University monitored the health of the institutional mouse colonies by exposing sentinels (CD-1 females, 4–6 weeks of age; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) to dirty bedding. According to institutional health reports, sentinel mice were negative for the following viral pathogens: mouse parvovirus, Sendai virus, pneumonia virus of mice, mouse hepatitis virus, minute virus of mice, Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus, reovirus and epizootic diarrhea of infant mice virus. Sentinel animals were also negative for the following bacterial, mycoplasmal and fungal pathogens: Mycoplasma pulmonis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Corynebacterium kutscheri, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pasteurella multocida, Pasteurella pneumotropica, Pasteurella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Beta Streptococcus spp. Groups B and C, Beta Streptococcus spp., Salmonella spp., Citrobacter rodentium and Citrobacter spp. Additionally, sentinels were free of ectoparasites, endoparasites and enteric protozoa.

In this study we used two different GEM colonies. The sEHKO strain originated on a B6J;129X1 background and was backcrossed to C57BL/6J for at least six generations before becoming homozygous3,4. These mice lack the gene Ephx2, which encodes soluble epoxide hydrolase, an enzyme responsible for the metabolism of P450 eicosanoids3,4. Mice homozygous with respect to the targeted gene deletion were viable, fertile and of normal size and had no gross physical or behavioral abnormalities. As previously described3,4, animals were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; primer sequences available from the authors on request). The expected sizes of the PCR products were 233 base pairs (bp) for the wild-type allele and 190 bp for the sEHKO allele; the presence of both PCR products was expected for heterozygotes. Every set of PCR reactions contained a negative control (no DNA) and a positive control (heterozygous DNA). We maintained the breeding colony using homozygous sEHKO breeding harems (2 females, 1 male). We used timed pregnant sEHKO mice to generate primary astrocyte and neuronal cultures for in vitro ischemia studies.

The GFP transgenic strain was developed on a C57BL/6 background. Mice were generated using a transgene that comprised the promoter of the L7 gene fused to cDNA encoding the tau-GFP fusion protein5. These mice only express tau-GFP under the control of the L7 promoter in cerebellar neurons5. Mice homozygous with respect to the transgene were viable, fertile and of normal size and had no gross physical or behavioral abnormalities. As previously described5, this strain was genotyped by PCR (primer sequences available from the authors on request); the GFP transgene had an expected size of 420 bp. We maintained the breeding colony using homozygous GFP breeding harems (2 females, 1 male). We used timed pregnant GFP mice to generate primary Purkinje cell cultures for in vitro ischemia studies.

Breeding colony database

We collected colony data daily and entered the data into a customized version of a relational database management system called gMouse (Circusoft Instrumentation LLC, Hockessin, DE)6. This system allows us to track an individual mouse by age, sex, genotype, colony or assigned user. We can also calculate reproductive indices for individual breeders and for specific colonies during a specified time interval. Finally, we can set up a centralized calendar for weaning, genotyping and animal distribution to investigators and projects.

Estrous cycle synchronization

We modified a previously described protocol for inducing estrus and proestrus in female mice by exposing them to bedding soaked with male urine (Whitten effect)7. We pair-housed sexually mature females (at least 60 d old) for at least 1 week. Sexually mature male mice (at least 60 d old) were separately group-housed (n = 4–5 mice per cage) for 1 week. We then exposed the females for 4 d to bedding soaked with male urine. Next we placed one male with a pair of naturally synchronized females for a period of 48 h in order to generate timed pregnant females 16 d after removal of males, between gestation days 16 and 18.

Vaginal plug detection, body weight measurement and pregnancy confirmation

During timed male exposure (48 h), we checked females for the presence of a vaginal plug every morning between 7:00 and 10:00 AM (Fig. 1). Upon removal of males, we measured a baseline body weight (day 1) for all females. We weighed all females again 7 and 14 d after removal of the males. We confirmed pregnancy either by the presence of fetuses at the time of euthanasia and fetal tissue harvest (16 d after removal of males) or by the birth of a litter.

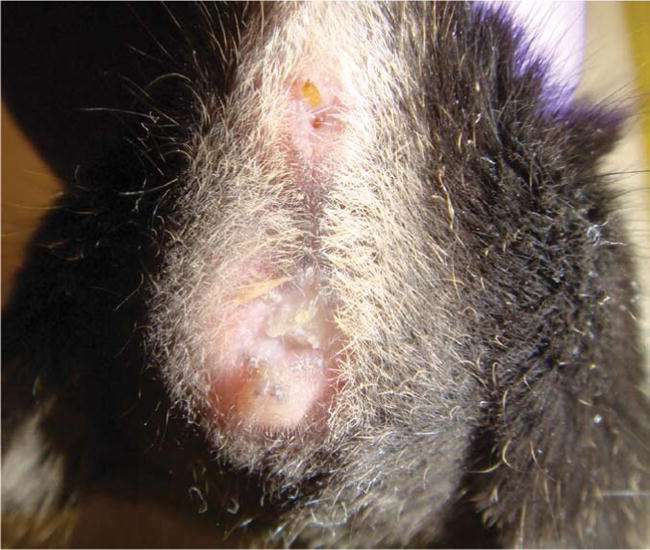

FIGURE 1.

Representative vaginal plug in a naturally synchronized female sEHKO mouse after timed exposure (48 h) to a male.

Evaluation of pregnancy indices

For each colony, we recorded and averaged the following pregnancy indices: pregnancy rate (number of pregnant females/total number of females × 100%), plug rate (number of females with plugs/total number of females × 100%), ‘plugged’ pregnant rate (number of pregnant females with plugs/total number of females with plugs × 100%) and size of first litters (number of pups). We tracked and recorded all data using customized spreadsheets (Microsoft Office Excel 2007, Redmond, WA).

Statistics

Values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. or as percentages. The size of the first litters within each colony is presented as a box-and-whisker plot. We used two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Newman-Keuls test to determine statistical significance of difference between baseline and weekly body weights (g, % baseline body weight). Statistical significance was P < 0.05. We carried out all statistical analyses using SigmaStat Statistical Software, Version 3.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Pregnancy indices in sEHKO and GFP mice

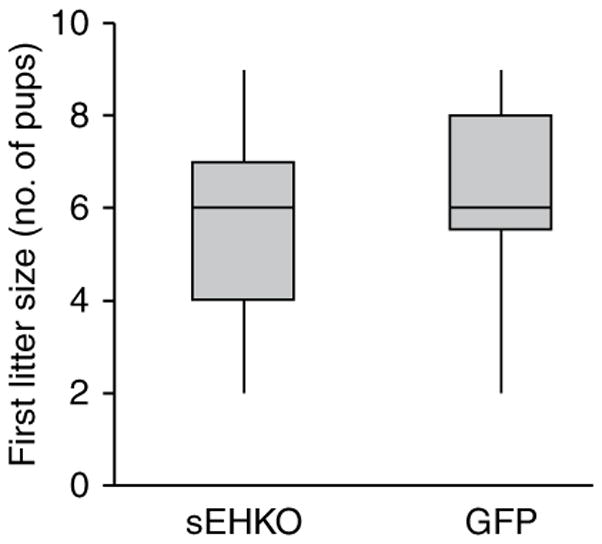

Synchronized females in the sEHKO (n = 164) and GFP (n = 61) colonies had pregnancy rates of 35% and 51%, respectively. Observed plug rates were 70% in the sEHKO colony and 21% in the GFP colony. Plugged pregnant rates were 41% and 69%, respectively, in sEHKO (n = 115 plugged females) and GFP (n = 13 plugged females) colonies. Average first litter sizes in the sEHKO (n = 56 litters) and GFP (n = 31 litters) colonies were 5.5 ± 0.2 and 6.5 ± 0.3 pups, respectively. Litter size for first litters ranged from two to nine pups in both the sEHKO and GFP colonies. There were no outliers for first litter size in either colony (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Box-and-whisker plot of first litter size (number of pups per first litter) in naturally synchronized female sEHKO mice (n = 56 litters) and GFP mice (n = 31 litters) after timed exposure (48 h) to males.

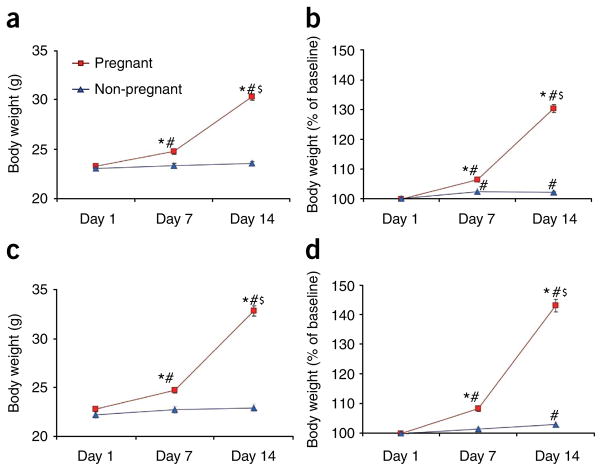

Body weight changes following timed male exposure

In the sEHKO colony, baseline body weights of pregnant (23.3 ± 0.3 g, n = 57) and non-pregnant (23.1 ± 0.2, n = 107) female mice did not differ significantly (Fig. 3a,b). Pregnant sEHKO mice had significantly higher body weights than did non-pregnant female mice at day 7 (24.8 ± 0.3 g vs. 23.4 ± 0.2 g, P < 0.001; 107 ± 1% baseline body weight vs. 102 ± 0% baseline body weight, P < 0.001) and day 14 (30.3 ± 0.3 g vs. 23.6 ± 0.2g, P < 0.001; 130 ± 1% baseline body weight vs. 102 ± 0% baseline body weight, P < 0.001; Fig. 3a,b). In pregnant sEHKO mice, body weights at days 7 and 14 were significantly higher than baseline body weight (P < 0.001). We also observed a significant increase in body weight in pregnant sEHKO mice between days 7 and 14 (P < 0.001; Fig. 3a,b). In non-pregnant sEHKO mice, body weights at days 7 and 14 (expressed as a percentage of baseline body weight) were also significantly higher than baseline body weight (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3.

Body weight in naturally synchronized female sEHKO and GFP mice after timed exposure (48 h) to males. Baseline body weight was measured immediately after removal of males (day 1), and body weight was measured weekly thereafter (days 7 and 14). Values are means ± s.e.m. (a,b) sEHKO female mice (n = 57 pregnant, n = 107 non-pregnant). (c,d) GFP female mice (n = 31 pregnant, n = 30 non-pregnant). *P < 0.05 compared with non-pregnant mice of each strain at each time point; #P < 0.05 compared with baseline body weight for each group; $P < 0.05 compared with body weight at day 7 for each group.

In the GFP colony, baseline body weights of pregnant (22.9 ± 0.3 g, n = 31) and non-pregnant (22.3 ± 0.4 g, n = 30) female mice did not differ significantly (Fig. 3c,d). Pregnant GFP mice had significantly higher body weights than did non-pregnant mice at day 7 (24.8 ± 0.3 g vs. 22.8 ± 0.4 g, P < 0.001; 108 ± 1% baseline body weight vs. 102 ± 1% baseline body weight, P < 0.001) and day 14 (32.8 ± 0.5 g vs. 23.0 ± 0.4 g, P < 0.001; 143 ± 2% baseline body weight vs.103 ± 1% baseline body weight, P < 0.001; Fig. 3c,d). In pregnant GFP mice, body weights at days 7 and 14 were significantly higher than baseline body weight (P < 0.001). We also observed a significant increase in body weight in pregnant GFP mice between days 7 and 14 (P < 0.001; Fig. 3c,d). In non-pregnant GFP mice, body weight at day 14 (expressed as a percentage of baseline body weight) was significantly higher than baseline body weight (P = 0.044).

DISCUSSION

Timed pregnant mice are used by investigators to generate primary cultures from fetal or neonatal tissues for experimental studies. For example, in this study, primary astrocyte, neuronal and Purkinje cell cultures were derived from timed pregnant sEHKO and GFP mice for in vitro ischemia studies. Timed pregnant mice are also useful for age-specific fetal and neonatal studies.

To efficiently produce timed pregnant mice for experimental studies, males should be placed with females that are in the proestrus stage of the estrous cycle8. If males are placed with females regardless of estrous cycle stage9, more females may be required, as a relatively small proportion of females will be in pro-estrus on any given day, even if researchers use vaginal cytology or impedance measurements to determine the estrous cycle stage of females. Researchers should synchronize the estrous cycles of the female mice to ensure that a greater proportion of females will be in proestrus during timed mating, thus reducing the overall number of females needed to generate a certain number of timed pregnant mice.

The estrous cycles of female mice can be synchronized by hormone priming with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or by exposing the female mice to male urine, thereby taking advantage of the Whitten effect7,8. The pheromones present in male mouse urine induce estrus in housed female mice9–14. Because the effects of PMSG and hCG have not been characterized in many GEM strains, including those being used in our laboratories, we chose to synchronize sEHKO and GFP female mice for timed matings by using the Whitten effect. In addition, some of our investigators were concerned that these exogenous gonadotropins could confound outcomes in tissue preparations and culture models.

We modified a previously described protocol for naturally inducing estrus and proestrus in female mice through exposure to bedding soaked with male urine (Whitten effect)7. One limitation of our study was that we did not carry out vaginal cytology analysis to determine the estrous stage in each female before placing the females with males. However, in group-housed (n = 6–8 females per cage) female mice, this protocol has previously induced estrus and proestrus in 51% and 76% of female mice, respectively7. Instead of housing females in large groups, as previously described for estrous cycle synchronization7, we elected to pair-house females throughout the study. We chose to do this because the number of females available for timed pregnant matings varied greatly each week, depending on the production of mature female offspring from the breeding colony and the number of non-pregnant females that had been used in previous timed mating protocols. To minimize confounding factors that could arise from changing or variable group numbers for each timed mating cycle, we wanted to standardize the number of females per cage throughout the study. In addition, pair-housing ensured that the same females would be together throughout the study and upon introduction of a male.

After exposing the synchronized female mice to the male mice, we recorded different pregnancy indices to try to determine which of the female mice had become pregnant. Early pregnancy detection in timed pregnant studies provides multiple advantages. First, personnel receive advance notice of how many timed pregnant mice will be available in a given week, thus allowing them to better plan experiments. Second, laboratory personnel can recycle non-pregnant females back into timed mating protocols sooner, thus reducing overall per diems and the number of female mice needed in a study.

The most commonly used methods to detect pregnancy in mice include looking for a vaginal or copulation plug8,9,15,16, ultrasonography17, weight gain18, abdominal palpation16, placental sign19,20 and visual inspection of the female16. These methods vary in terms of the technical skills, evaluation time and equipment needed; cost; and window of reliable detection (i.e., how early in gestation pregnancy can be reliably detected). We used visualization of vaginal plugs and body weight gain after timed male exposure for pregnancy detection. These techniques required minimal labor costs, technical skills (general mouse handling skills), evaluation time (< 1 min per mouse on a daily or weekly basis) and equipment (balance for weighing mice). By using these techniques, personnel could also possibly detect pregnancy during the first week of gestation.

Vaginal or copulation plugs form from coagulated secretions of the coagulating and vesicular glands of the male mouse9. Because mating usually occurs during the dark hours of the light cycle, it is best to look for vaginal plugs early in the morning8,9. The time period during which a plug is visible varies greatly, for up to 48 h in many inbred strains8,9 and for several days in outbred mice16. Plug formation and appearance also vary among mouse strains: some strains, such as sEHKO mice, have large, opaque, well-formed plugs (Fig. 1), whereas others, such as GFP mice, have small, almost translucent, indiscrete plugs. Variation in plug visibility, formation and appearance may partly explain why plug rates were lower in naturally synchronized GFP mice (21%) than in sEHKO mice (70%) and may account for the reported variation in plug rates within and among other mouse strains.

The day on which a plug is found is generally considered to be gestational day 1 (ref. 21). However, the presence of a plug indicates only that sexual activity has occurred and, because plugs may have been either poorly formed or dislodged, does not guarantee that a female is pregnant8,9,15,16. Plugged pregnant rates (number of plugged pregnant females/total number of plugged females × 100%) vary tremendously among mice. For example, in CD-1 mice, an outbred stock, about 70–75% of plugged females will be pregnant, whereas less than 50% of inbred plugged female mice might be pregnant21,22. In this study, plugged GFP females were more likely to be pregnant than plugged sEHKO females (69% for GFP versus 41% for sEHKO). In other GEM strains with low plugged pregnant rates, investigators can still define gestational age ranges in timed pregnant females by limiting the period of exposure to males as we did in this study for the GFP and sEHKO females.

Our investigators chose to purchase timed pregnant wild-type controls (C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) for sEHKO studies and C57BL/6NCrl (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) for GFP studies) for their experiments; therefore, we could not evaluate pregnancy indices from naturally synchronized wild-type controls. Though pregnancy indices in naturally synchronized mouse strains are rarely reported, some information from commercial vendors is available on pregnancy indices and litter sizes in unsynchronized C57BL/6J and C57BL/6NCrl mice to allow for limited comparisons between our sEHKO and GFP colonies and their respective wild-type counterparts.

Depending on housing location and husbandry management, plugged pregnant rates can range from 33% to 85% in unsynchronized C57BL/6J females (Technical Information Services, The Jackson Laboratory; personal communication). Our observed plugged pregnant rate of 41% in synchronized sEHKO mice on a C57BL/6J background falls within this range, suggesting that natural estrous synchronization may not optimize plugged pregnancy rates. In unsynchronized C57BL/6NCrl females (n = 489), pregnancy, plug and plugged pregnant rates in females exposed to males for 24 h were 11%, 30% and 37%, respectively (K.P.-C., unpublished data), versus 51%, 21% and 69%, respectively, in our naturally synchronized GFP females (n = 61). These data suggest that natural estrous synchronization improved pregnancy and plugged pregnant rates in GFP mice. Average litter size for first litters in sEHKO mice was comparable (5.5 ± 0.2 pups per first litter) to the overall average litter size (5.5 pups per litter) reported in unsynchronized C57BL/6J females (n = 50 females; Technical Information Services, The Jackson Laboratory, personal communication and ref. 23). Average litter size for first litters in C57BL/6NCrl mice (7.5 ± 0.3, n = 34 litters; K.P.-C., unpublished data) was greater than that of GFP mice (6.5 ± 0.3, n = 27 litters).

To measure body weight gain, we weighed GFP and sEHKO female mice at 1-week intervals, starting after timed exposure to males. We confirmed pregnancy by the presence of fetuses 16 d after removal of males or by the birth of a litter. We stratified body weights according to confirmation of first litter pregnancy, thus minimizing any confounding effects due to pseudo-pregnancy, litter number or parity status. In addition to presenting absolute weight at each time point as others have done18, we normalized weekly body weights to the baseline body weight taken at the time of removal of the males. This allowed us to determine whether percentage weight gain was indicative of pregnancy in each of the two GEM strains. Females that were later confirmed to be pregnant had significant increases in body weight at 7 and 14 days after timed male exposure.

Although plug rate was much lower in GFP mice than in sEHKO mice, plugged females were more likely to be pregnant in the GFP than the sEHKO colonies. Furthermore, in both the sEHKO and GFP colonies, increases in body weight 7 and 14 d after timed male exposure more accurately indicated pregnancy than did the presence of vaginal plugs. These findings suggest that, in these two specific GEM breeding colonies, using body weight change instead of plug presence as an indicator of pregnancy could help detect pregnancy within the first week of gestation. This could help reduce both the number of females needed for timed matings and the number of unexpected pups born 3 weeks later.

One reproductive index that we did not evaluate extensively in this study was litter size relative to litter number. In most female mice, litter size begins to decrease after four or five litters, with the second and third litters generally being the largest8,16. Differences in number and growth of offspring between litter numbers have also been observed in other mouse strains24,25. Thus, in order to optimize production of offspring in timed mating protocols, researchers should evaluate litter size and number in each individual GEM strain.

Assessing pregnancy indices (pregnancy rate, plug rate, pregnant plugged rate, first litter size and body weight) in our GFP and sEHKO breeding colonies provided useful strain-specific information for refining timed pregnancy protocols, which can reduce overall costs and labor. To generate timed pregnant females within a specific 24- or 48-h gestation window, we plan to further refine our timed mating protocols by limiting male exposure to 24 or 48 h in naturally synchronized GFP and sEHKO females. We also plan to weigh GFP and sEHKO females daily after timed male exposure to determine whether we can detect significant weight gain due to pregnancy even sooner than 1 week after removal of males from synchronized females. Additionally, we want to determine whether we can correlate gestational day to percentage of weight gain in each colony, regardless of litter number. Further evaluations and refinements are planned based on litter size and litter number in our sEHKO and GFP colonies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants NS49210, NS20020 and NS044313 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Debra L. Hickman for her review and comments on preliminary versions of this manuscript; Nabil Alkayed, MD, PhD and Paco Herson, PhD for their support of this study by providing the sEHKO and GFP mouse colonies, respectively; Sarah Shangraw for assistance with the husbandry manipulations and body weight measurements of the animals used in this study; Jennifer Young, Patty Ayala and Melissa Hernandez for collecting data regarding litter size; John Todd and Ashley Branch for assistance with manuscript figures; and Charles River Laboratories and The Jackson Laboratory for providing information on pregnancy indices in C57BL/6NCrl and C57BL/6J mice, respectively.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Southwell K. The benefits of a rodent breeding service. Tech Talk. 2008;13:4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinal CJ, et al. Targeted disruption of soluble epoxide hydrolase reveals a role in blood pressure regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40504–40510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase gene deletion is protective against experimental cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:2073–2078. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekirnjak C, Vissel B, Bollinger J, Faulstich M, du Lac S. Purkinje cell synapses target physiologically unique brainstem neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;15:6392–6398. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06392.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham SM, Klatil F, Murphy SJ. Developing a mouse colony database from scratch: options and challenges. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2005;44:62–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalal SJ, Estep JS, Valentin-Bon IE, Jerse AE. Standardization of the Whitten Effect to induce susceptibility to Neisseria gonorrhoeae in female mice. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2001;40:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pritchett KR, Taft RA. In: The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models. chap 3. Fox JG, et al., editors. Vol. 3. Academic; San Diego: 2007. pp. 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suckow MA, Danneman P, Brayton C. The Laboratory Mouse. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chipman RK, Fox KA. Oestrous synchronization and pregnancy blocking in wild house mice (Mus musculus) J Reprod Fertil. 1966;12:233–236. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0120233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gangrade BK, Dominic CJ. Oestrous induction in unisexually grouped mice by multiple short-term exposures to males. Experientia. 1983;39:431–432. doi: 10.1007/BF01963166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harman SM, Talbert GB. Effect of maternal age on synchronization of ovulation and mating and on tubal transport of ova in mice. J Gerontol. 1974;29:493–498. doi: 10.1093/geronj/29.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharmann W, Wolff D. Production of timed pregnant mice by utilization of the Whitten effect and a simple cage system. Lab Anim Sci. 1980;30:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitten WK. Pheromones and mammalian reproduction. Adv Reprod Physiol. 1966;1:155–177. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinlivan LJ. Troubleshooting mouse breeding: vaginal plug detection. Tech Talk. 2007;12:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silver LM. Mouse Genetics: Concepts and Applications. chap 4. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown SD, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of mouse pregnancy and gestational staging. Comp Med. 2006;56:262–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onojafe FI. Vaginal mucous plug and weight gain in mice. Tech Talk. 2005;10:4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Feo VJ. In: Cellular Biology of the Uterus. Wynn RM, editor. chap 8. Plenum; New York: 1967. pp. 191–290. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanjo H. On the placental sign as an early indicator of pregnancy in mice. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1963;38:321–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charles River Laboratories. Pregnant Animal Guarantee Policy. Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, DE: 2008. < http://www.criver.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/rm_rm_c_pregnant_animal_guarantee.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charles River Laboratories. Technical Sheet: Protocol for Setting up Timed Pregnant Rats and Mice. Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, DE: 2008. < http://www.criver.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/rm_rm_d_pregnant_rodent.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flurkey K, Currer JM, Leiter EH, Witham B. The Jackson Laboratory Handbook on Genetically Standardized Mice. 6. chap 4. The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, ME: 2009. pp. 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krackow S, Gruber F. Sex ratio and litter size in relation to parity and mode of conception in three inbred strains of mice. Lab Anim. 1990;24:345–352. doi: 10.1258/002367790780865895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagasawa H, Koshimizu U. Difference in reproductivity and offspring growth between litter numbers in four strains of mice. Lab Anim. 1989;23:357–360. doi: 10.1258/002367789780746060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]