Abstract

Warfarin is a widely used oral anticoagulant which is mostly administrated as a racemic mixture containing equal amount of R- and S-enantiomers. The two enantiomers are shown to exhibit significant differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. In this study, a new chiral micellar electrokinetic chromatography-mass spectrometry (MEKC-MS) method has been developed using a polymeric chiral surfactant, polysodium N-undecanoyl-L, L-leucylvalinate (poly-L, L-SULV), as a pseudostationary phase for the chiral separation of (±)-warfarin (WAR) and (±)-coumachlor (COU, internal standard). Under optimum MEKC-MS conditions, the enantio-separation of both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU was achieved within 23 min. Calibration curves were linear (R=0.995 for (R)-WAR and R=0.989 for (S)-WAR) over the concentration range 0.25–5.0 μg/mL. The MS detection was found to be superior over the commonly used UV detection in terms of selectivity and sensitivity with LOD as low as 0.1μg/mL in human plasma. The method was successfully applied to determine WAR enantiomeric ratio in patients plasma undergoing warfarin therapy.

Keywords: Micellar electrokinetic chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (MEKC-ESI-MS), Warfarin, Poly-L, L-SULV, Chiral analysis

1. Introduction

Warfarin (WAR) is widely used as an oral anticoagulant and functions as a vitamin K antagonist by inhibiting the synthesis of vitamin K reductase and vitamin K epoxide reductase, thus decreasing the ability of blood to form clot. The concentration of WAR in plasma must be carefully monitored by repeated analysis of prothrombin time (International Normalized Ratio, INR) because WAR has a very narrow therapeutic window which leads to a very large variation in dosage required for optimal INR. Furthermore, (R)- and (S)- enantiomers of WAR exhibit considerable differences in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. For example, the (S)-WAR is 2–5 times more potent anticoagulant, and is metabolized much quicker (~1.5 times faster) than the (R)-WAR [1]. At steady state, the (S)-WAR is present at only half the concentration of (R)-WAR. A possible association between the WAR enantiomers and genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450(CYP)2C9 has been purposed [2]. Therefore, a sensitive chiral assay for the determination of (R) - and (S)-WAR concentrations in human plasma might be highly valuable for clinical patients care.

Historically, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection is commonly seen as the analytical method for the determination of WAR enantiomers [3–7]. However, analysis of WAR in biological samples is troublesome due to low sensitivity and specificity of UV-detection. Recently, several tandem mass spectrometry methods coupled to supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) or HPLC for WAR analysis have been published. The SFC-MS-MS application has been described for the highthroughput determination of WAR enantiomers in plasma samples by Coe et al. [8]. However, the robustness of SFC equipment (e.g., pump used to deliver CO2 mobile phase) is a critical factor. Using HPLC-MS-MS both enantiomers of WAR and coumachlor (COU) were reproducibly separated in 8 min on a β-cyclodextrin column with limit of detection as low as 1ng/mL [9].

Although the achiral analysis of charged compounds in CE-MS is simply accomplished by the use of volatile buffers, chiral analysis is problematic mainly due to non-volatility and background noise created by the use of low molecular mass chiral selectors (e.g., cyclodextrins and its derivatives, macrocyclic antibiotics, and low molecular crown ethers) [11]. To circumvent the aforementioned problems the partial filling technique with or without counter current migration have been reported [12–14]. Tanaka has applied a partial filling technique for CE-MS to successfully separate some acidic enantiomers including racemic warfarin [15]. However, the partial filling technique have some limitations such as much lower resolution and lower peak capacity compared to the standard MEKC-MS [16].

Micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) is one of the CE modes, which is capable of separating both charged and neutral enantiomers with high efficiency, selectivity and flexibility. As one of the most potential techniques in CE, coupling MEKC with ESI-MS is very attractive and advantageous. However, direct coupling of MEKC to MS has been considered problematic because the nonvolatile surfactants and buffer salts [used as MEKC background electrolyte (BGE)] can contaminate ion source producing a high background noise and suppressing the analyte ionization [16–20]. As a potential solution to this problem, the use of polymeric chiral surfactants (also called molecular micelles or micelle polymers) in MEKC have been effectively utilized for chiral separation and MS detection of a variety of compounds, which includes binaphthol [21], β-blockers [22], benzodiazepines [23], and phenylethylamines [24–26]. It should be noted that most of the afore- mentioned classes of chiral compounds were simultaneously analyzed by MEKC-MS due to wider migration window offered by polymeric chiral surfactants. In addition, polymeric surfactants have several notable advantages over the conventional micelles (formed from monomeric surfactants). This includes zero critical micelle concentration (CMC), very stable micellar structure, low surface activity, low volatility as well relatively narrow size range and high molecular weight. Therefore, all of the aforementioned characteristics make polymeric surfactants very compatible for on-line MEKC-ESI-MS.

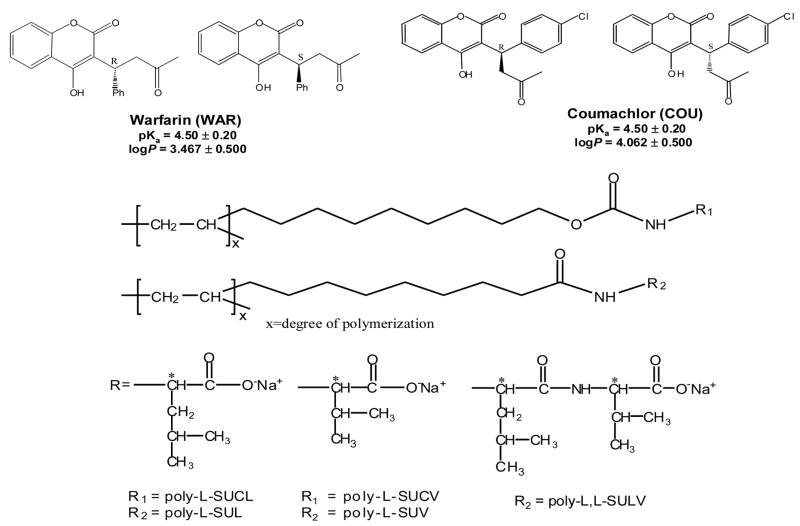

As a continuous endeavor towards developing new applications of chiral MEKC-ESI-MS using polymeric surfactant, in the present study we sequentially optimized the MEKC-MS parameters for simultaneous analysis of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU (Fig. 1). Using a novel polymeric surfactant, MEKC-ESI-MS conditions were first optimized. Next, the developed method was applied for profiling plasma samples of patients undergoing the anticoagulant therapy.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of (±)-warfarin (WAR), (±)-coumachlor (COU) and polymeric surfactants as pseudostationary phase in MEKC-ESI-MS. The pKa and log P were calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software, Version 8.14 for Solaris.(1194–2006, ACD Labs)

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Racemic mixtures of WAR and COU (Fig. 1) were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). (R)-WAR (>99%) and (S)-WAR (>99%) were obtained from Cedra Co. (Austin, TX, USA). Analytical grade ammonium acetate (as 7.5 M NH4OAc solution) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile (ACN) and methanol (MeOH), both HPLC grade, were purchased from Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI, USA). Ammonium hydroxide (NH3·H2O) and acetic acid (HOAc) were supplied by Fisher Scientific (Springfield, NJ, USA). Perchloric acid was obtained from J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) as a 70% (v/v) solution. Water used in all experiments was triply deionized and obtained from Barnstead Nanopure II water system (Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA, USA). All polymeric surfactants (Fig. 1) were synthesized according to the procedures previously reported [22,27]. Recent studies are in our laboratory suggested excellent interbatch reproducibility of our polymeric surfactants. For example, four different batches of polymeric N-undecenoxycarbony-L-leucinate (poly-L-SUCL) provided average resolution of 2.0 for enantiomers of (±)-binaphthol with a relative standard deviation of 3.6%.

2.2. Buffers and sheath liquid preparation

The background electrolyte (BGE) was prepared by diluting the stock 7.5 M ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) solution and then adjusting to the desired pH values with HOAc or NH3·H2O using an Orion 420A pH meter (Beverly, MA). The chiral MEKC running buffers were prepared by adding various amounts of polymeric surfactant to the BGE solution. The sheath liquid [80/20 (v/v) of MeOH-NH4OAc, 5 mM NH4OAc, pH 6.8] was prepared by mixing aqueous NH4OAc buffer (adjusted to the desired pH value) with MeOH. The running MEKC buffers and sheath liquid were filtered with 0.45 μm PTFE membranes and degassed for 20 min before use.

2.3. Standard solutions and plasma preparation

The stock solutions of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU were prepared at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL in ACN-H2O (40:60, v/v). The working standard solution was obtained by diluting the stock solution to desired concentration with ACN-H2O (40:60, v/v). The migration order of enantiomers was established by spiking the racemic warfarin standard solution with individual enantiomers.

Blank and patient’s human plasma were obtained from Mercer University Southern School of Pharmacy (Atlanta, GA, USA) and stored under −80 °C until the assay was performed. For blank plasma samples, a 300 μL aliquot of plasma was spiked with the desired volume of (±)-WAR solution at levels of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0 μg/mL and an internal standard of (±)-COU was added at a concentration of 2.0 μg/mL in each of the five eppendorf tubes. Both the spiked plasma and the patient’s plasma were deproteinized by adding 0.2 mL of 10% HClO4 and vortexed for 30 s. The samples were centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 min and then the supernatant was transferred to a MAX solid- phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) which had been previously conditioned with 1 mL of CH3OH and 1 mL of H2O, respectively. After loading sample on the cartridge, the column was washed with 2 mL of 2% NH3·H2O and then 2 mL of H2O. Finally, the (±)-WAR and (±)-COU were eluted with 2 mL of 5% HCOOH in ACN-MeOH (50:50, v/v). The eluate from the SPE column was evaporated to dryness in a water bath at 60 °C under a stream of N2. The residue was reconstituted with 50 μL of ACN-H2O (40:60, v/v) and injected into the capillary by applying a pressure of 5 mbar for 2 s. Using this injection time and pressure, the reproducibility (i.e.,%RSD) of migration time, peak area and resolution of (±)-WAR were 1.2%, 3.1% and 5.2%, respectively.

2.4. Instrumentation and method

All MEKC-ESI-MS experiments were carried out with an Agilent capillary electrophoresis (CE) system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) interfaced to an Agilent 1100 series MSD quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with an Agilent CE-MS adapter kit (G1603A), and an Agilent CE-ESI-MS sprayer kit (G1607). The sheath liquid was delivered by an Agilent 1100 series isocratic HPLC pump equipped with a 1:100 splitter. Nitrogen was used as both nebulizing gas and drying gas. The Agilent ChemStation and CE-MSD add-on software were employed for instrument control and data analysis. A 120 cm long fused silica capillary (OD 375 μm, ID 50 μm, obtained from Polymicro Technologies Inc., Phoenix, AZ, USA) was used for MEKC-UV-MS set-up. The UV detection window was fabricated by burning 1–2 mm segment of polyimide coating of the capillary at 60 cm from the inlet side.

2.5. Chiral MEKC-ESI-MS conditions

Before the capillary was installed into the ESI-MS sprayer, the capillary was flushed with 1M NH3·H2O for 30 min and water for 10 min at 45°C. After the installation of the capillary into the sprayer, the capillary was flushed with 1M NH3·H2O and water for 3 min each, followed by a final rinse with the running buffer for 4 min before injection. The separation voltage was set at 30 kV, employing a voltage ramp of 3 kV/s. The UV detection wavelength was set at 254 nm (bandwidth, 10 nm). In order to ensure good repeatability for the migration time, a fresh buffer vial was always used for each MEKC run. The sample was injected by applying a pressure of 5 mbar for 2 s. Unless otherwise stated, the following ESI-MS conditions were used: sheath liquid, MeOH/H2O (80:20 v/v) containing 5 mM NH4OAc at pH 6.8; sheath liquid flow rate, 5 μL/min; capillary voltage, −3000 V; fragmentor voltage, 91 V; drying gas flow rate, 6.0 L/min; drying gas temperature, 200 °C; nebulizer pressure, 4 psi (275.8 mbar). The ESI-MS detection was performed in the selective ion monitoring (SIM) mode. The fragmentor voltages were optimized by directly infusing the standard solution of 10 μg/mL WAR and COU from the CE inlet vial using 50-mbar pressure into the MS. The negative [M-H]− ions were monitored at m/z 307.0 for (±)-warfarin (WAR) and at m/z 341.5 for (±)-coumachlor (COU).

Chiral resolution (Rs), selectivity (α), and separation efficiency (Navg)(at the base width) of enantiomers were calculated with Agilent Chemstation software (V 9.0). The noise level was determined using 6 times the standard deviation of the linear regression of the baseline drift for a selected time range between 8 and 18 min. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N (avg)) was obtained as the ratio of peak height of first eluting enantiomer over the noise level. The calibration curves for (S)-WAR and (R)-WAR were obtained by plotting the peak area ratio of the respective WAR enantiomer to the internal standard [(S)-coumachlor and (R)-coumachlor] versus spiking concentration. To assess linearity, the line of best fit was determined by least-squares regression.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Selection of polymeric surfactant

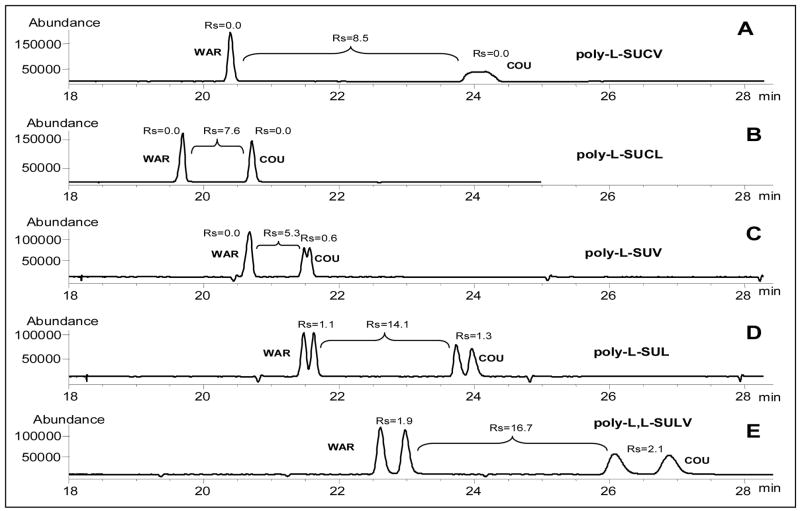

Generally, based on the linkage of amino acid or peptide to the hydrocarbon tail, the chiral polymeric surfactant could be classified as amide or carbamate types. The carbamate-type single amino acid polymeric surfactant consists of two carbonyls and one amide group, which is attached to the hydrocarbon chain with a carbamate linker. On the other hand, the amide-type polymeric surfactant has the same number of carbonyls and amide on the head group, but the amide linker is attached to the hydrocarbon chain. However, the dipeptide amide surfactant i.e., poly(sodium N-undecenoyl-L, L-leucyl-valinate (poly-L, L-SULV) has four carbonyl groups and two amide groups with two chiral centers (Fig. 1). It has been well recognized that the type of chiral polymeric surfactants showed different enantioselectivity which is analyte dependent [20, 23, 28]. In order to achieve the best chiral resolution for simultaneous separation of(±)-WAR and (±)-COU in MEKC-ESI-MS using volatile BGE, five polymeric surfactants, including two carbamate type polymers [poly-L-SUCL and poly(sodium N-undecenoxycarbonyl-L-valinate (poly-L-SUCV)], and three amide type polymers [poly(sodium N-undecenoyl-L-leucinate (poly-L-SUL), poly(sodium N-undecenoyl-L-valinate (poly-L-SUV) and (poly-L, L-SULV)] were synthesized and evaluated in our laboratory. Electropherograms in Fig. 2 shows that the two carbamate type polymeric surfactants (i.e., poly-L-SUCV and poly-L-SUCL,) do not exhibit any chiral resolution for (±)-WAR and (±)-COU (Fig. 2A and 2B). Among the amide-type polymeric surfactants, using NH4OAc as BGE, poly-L-SUV shows partial chiral resolution but only for (±)-COU (Fig. 2C). However, the use of different BGE (e.g., 25 mM monobasic phosphate at pH 5.6) in MEKC-UV was reported to provide chiral separation of warfarin using poly-L-SUV [29]. However, it is now well established phosphate being a non-volatile buffer is not suitable for MEKC-MS. For MEKC-MS the choice of BGE is rather limited compared to MEKC-UV. Using NH4OAc as BGE, the leucine derivative, poly-L-SUL, could resolve both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU, but still could not provide baseline resolution values (Fig. 2D). However, the dipeptide amide derivative (i.e., poly-L, L-SULV) provided the best chiral resolution for both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU (Fig. 2E). The improved chiral separations with poly-L, L-SULV could be attributed to a greater number of hydrogen bonding sites as well as the presence of two chiral centers on the head group of this polymeric surfactant. In addition, poly-L, L-SULV also provided the best achiral RS (RS =16.7) between (±)-WAR and (±)-COU. Therefore, poly-L, L-SULV was chosen as the best pseudostationary phase for sequential optimization of MEKC-ESI-MS parameters to achieve simultaneous enantioseparation of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU.

Fig. 2.

Enantioselectivity of different polymeric surfactants for separation of (±)-warfarin (WAR) and (±)-coumachlor (COU). MEKC-ESI-MS conditions: 120 cm long (50μm, I. D.) fused-silica capillary (UV detection window at 60cm). Applied voltage, +30 kV. UV detection, 254 nm (bandwide,10 nm). Capillary temperature, 20°C. Injection: 5 mbar, 2 sec. Running buffer, 25 mM NH4OAc/25mM polymeric surfactant at pH=5.5. Spray chamber parameters, nebulizing gas pressure at 4 psi (275.8 mbar); drying gas temperature at 200°C; drying gas flow rate at 6L/min; capillary voltage at −3000V. Sheath liquid composition, MeOH/H2O (80/20, v/v) containing 5 mM NH4OAc at pH=6.8; sheath liquid flow rate at 5μL/min. SIM negative ion mode. Sample concentration: 0.1 mg/mL for (±)-WAR and (±)-COU.

3.2. Optimization of MEKC-MS conditions

3.2.1. Effect of BGE pH

The pH of the volatile BGE is one of the most important parameters in MEKC-MS. This is because pH of the BGE not only alters the charge on the analyte and chiral polymeric surfactant possessing ionizable heads, but also the magnitude of the electroosmotic flow (EOF) and MS detection sensitivity. The effect of running buffer pH on the chiral resolution (RS), migration time, column efficiency (Navg) and S/N(avg) of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU was examined in the pH of range of 5.5–8.0 (Table 1). As it can be seen, the migration time, chiral [RS(WAR) and RS(COU)] and achiral [RS(WAR-COU)] resolutions for both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU decreases with an increase in pH from 5.5 to 8.0. This observation is not surprising because at high pH the effective charge of the analyte and poly-L, L-SULV increases, which results in enhancement of electrostatic repulsive interactions between the analyte and poly-L, L-SULV decreasing chiral RS. Furthermore, as buffer pH increases, the magnitude of EOF increases, which results in increase in Navg of both enantiomers but also narrows the migration window, and therefore both achiral and chiral RS decreases. It is noticeable that the S/N(avg)for MS response of both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU increases with increasing pH of the running buffer due to faster migration that results in sharper peaks. Besides effect of decreasing migration time, the use of high pH could also facilitates ionization of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU under negative ion mode during ESI process. As a compromise between chiral RS and MS response, buffer pH of 6.0 was chosen as an optimal pH condition.

Table 1.

Optimization of MEKC-MS conditions

| MEKC-MS Conditions |

pH | Concentration of poly- L, L-SULV (mM) |

Concentration of BGE (mM) |

Nebulizing gas pressure (psi) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 5.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 25 | 35 | 45 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Migration time, tavg (min) | (R)-WAR | 21.5 | 20.4 | 19.5 | 19.0 | 18.2 | 18.7 | 19.3 | 20.4 | 19.5 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 25.7 | 24.6 | 22.2 | 20.5 |

| (S)-WAR | 21.7 | 20.6 | 19.6 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 18.8 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 19.6 | 22.9 | 23.3 | 26.2 | 24.8 | 22.5 | 20.6 | |

| (R)-COU | 24.8 | 22.6 | 21.2 | 20.2 | 19.4 | 20.2 | 21.0 | 22.7 | 20.8 | 24.6 | 25.9 | 29.7 | 27.2 | 24.7 | 22.3 | |

| (S)-COU | 25.1 | 23.1 | 21.5 | 20.5 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 23.2 | 21.2 | 25.2 | 26.5 | 30.5 | 27.82 | 25.2 | 22.7 | |

| RS | R, S-(WAR) | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| WAR/COU) | 12.9 | 13.2 | 11.1 | 8.3 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 13.2 | 9.6 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 12.2 | 16.4 | 14.0 | 8.4 | |

| R, S-(COU) | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 1.5 | |

| Plate Number (Navg) | (R)-WAR | 327000 | 411000 | 455100 | 500200 | 270400 | 363500 | 366300 | 409500 | 354200 | 461200 | 437200 | 415000 | 554600 | 461200 | 297000 |

| (S)-WAR | 309700 | 397900 | 426300 | 357000 | 261300 | 323900 | 328300 | 397900 | 354600 | 459200 | 409500 | 356800 | 574700 | 459200 | 303000 | |

| (R)-COU | 173900 | 274200 | 332600 | 380500 | 83800 | 126000 | 160600 | 274200 | 465100 | 233700 | 200600 | 83500 | 364700 | 233700 | 161200 | |

| (S)-COU | 156300 | 232100 | 275000 | 329200 | 65700 | 83100 | 118800 | 233900 | 384400 | 162600 | 128430 | 17100 | 308100 | 162600 | 121600 | |

| S/N(avg) | (R)-WAR | 87 | 90 | 105 | 173 | 335 | 293 | 322 | 117 | 195 | 284 | 250 | 234 | 176 | 318 | 499 |

| (S)-WAR | 82 | 87 | 103 | 184 | 322 | 270 | 306 | 114 | 217 | 286 | 229 | 223 | 177 | 320 | 531 | |

| (R)-COU | 50 | 57 | 73 | 140 | 146 | 145 | 179 | 73 | 162 | 157 | 107 | 85 | 110 | 157 | 259 | |

| (S)-COU | 48 | 51 | 69 | 129 | 138 | 136 | 172 | 68 | 156 | 137 | 89 | 41 | 100 | 137 | 236 | |

3.2.2. Effect of concentration of polymeric surfactant

The concentration of polymeric surfactant in MEKC-ESI-MS not only has a significant effect on chiral resolution, but also influences the S/N(avg) of ESI-MS detection. Since the molecular weight of poly-L, L-SULV is oustside the MS range no spectral clutter or background ions are seen in MEKC-MS with positive polarity. We speculate that a decrease in S/N with increase in surfactant concentration is possibly due to the entrance of trimers or tetramers into the ionization source when surfactant are used at high concentration which in turn deteriorates the ESI-MS signal. For polymeric surfactant, very low concentration can also be used in MEKC due to zero CMC. In fact, to obtain higher S/N(avg) in MEKC-ESI-MS, it is better to use the polymeric surfactant concentration as low as possible. On the other hand, very low concentration of the polymeric surfactant in the running buffer results in unsatisfactory chiral resolution. In order to determine the optimum polymeric surfactant concentration for the separation and detection of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU, the concentration of poly-L, L-SULV in the running buffer was investigated in the range of 10 mM to 25 mM. As can be seen in Table 1, from 10–20 mM increase in surfactant concentration there is no definite trend in S/N. However, the S/N shows a significant decrease from 20 to 25 mM. In addition, increasing the concentration of poly-L, L-SULV from 10 to 25 mM increases both RS (chiral and achiral) and Navg. Although 25 mM poly-L, L-SULV provided lower S/N, complete baseline separation of (±)-WAR enantiomers, was achieved and was therefore considered as an optimum polymeric surfactant concentration.

3.2.3. Effect of NH4OAc concentration

When a MEKC-ESI-MS method is developed, volatile salts such as NH4OAc needs to be used as the BGE in order to reduce background noise. Moreover, due to the competition between analyte and NH4OAc ions for ionization during ESI process, higher concentrations of NH4OAc could suppress the MS signal. On the other hand, very low concentration of NH4OAc results in poor resolution of enantiomers. Thus, a proper concentration of NH4OAc must be optimized in MEKC-ESI-MS. From Table 1, it is evident that the migration times of both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU increases upon increasing the concentration of NH4OAc from 15 to 45 mM. This is due decrease in zeta potential which in turn lower EOF [30]. Overall, the best chiral RS, Navg and S/N(avg) for (±)-WAR and (±)-COU was observed at 25 mM of NH4OAc. However, upon further increasing NH4OAc concentration the Navg and the S/N(avg) of MS detection decreases (Table 1), and there was no significant gain in chiral Rs of (±)-WAR. Moreover, the peak of (S)-COU was deformed at 45 mM NH4OAc due to Joule heating effect (data not shown). Therefore, 25 mM of NH4OAc was chosen because it establishes a good compromise between chiral RS and MS sensitivity of the investigated analytes with a suitable analysis time.

3.3. Effect of spray chamber parameters

It is now well-established that for open tubular CE-ESI-MS or MEKC-ESI-MS, there is a suction effect at the outlet end of capillary due to nebulizing gas pressure when capillary is connected to ESI-MS interface [21–26]. The chiral RS and the migration time of analytes could strongly impact by this suction effect. The data in column 4, Table 1 shows that the migration time, RS (chiral and achiral) and Navg decreases when the nebulizing gas pressure is increased from 2–6 psi (i.e.,137.9 to 413.6 mbar). In contrast, the S/N(avg) increases four-fold due to increase in peak height upon increasing the nebulizing gas pressure. Therefore, the nebulizing gas pressure at 4 psi (275.8 mbar) is chosen as a good compromise between chiral RS and MS signal response.

Apart from the nebulizing gas pressure, the other two spray chamber parameters, drying gas flow rate and drying gas temperature, have no influence on the RS, Navg and the migration time of the analytes, but have significant effect on the MS signal response [22]. For MEKC-ESI-MS, in the range of 5 to 8 L/min of the drying gas flow rate and of 200 to 300°C of the drying gas temperature, ESI shows good stability of MS signal response [22–24]. These two parameters were sequential optimized over the aforementioned rangers (data not shown). The results indicated that the drying gas flow rate of 6 L/min and the drying gas temperature of 200°C are optimum conditions for MS signal response for both enantiomers.

Both (±)-WAR and (±)-COU were best resolved within 25 min with high sensitivity using the following MEKC-ESI-MS conditions. MEKC: 25 mM NH4OAc/25 mM poly-L, L-SULV; applied voltage, 30kV; capillary temperature, 20°C. Spray chamber parameters: dyring gas temperature, 200°C; drying gas flow rate, 6L/min, nebulizing gas pressure, 4 psi. capillary voltage, −3000 V; fragmentor voltage, 91 V; Sheath liquid: MeOH/H2O = 80/20 (v/v) containing 5 mM NH4OAc at pH 6.8; sheath liquid flow rate at 5 μL/min.

3.4. Application of MEKC-ESI-MS method for (±)-warfarin assay in human plasma samples

In order to evaluate the feasibility of MEKC-ESI-MS as a new chiral assay of (±)-WAR enantiomers, calibration plots of both enantiomers in blank plasma samples were generated by plotting the peak area ratio. The calibration curves of both (R)- and (S)-WAR were obtained by spiking standard (±)-WAR solution at levels from 0.5–10.0 μg/mL, and an internal standard of (±)-COU was added at a concentration of 2.0 μg/mL at each concentration level. Good linearity for both (R)-WAR (R = 0.9956) and (S)-WAR (R = 0.9897) in the range from 0.25 to 5 μg/mL was obtained. Mean plasma concentrations of (R)- and (S)-enantiomer in clinical study were reported to be ~0.9 and ~0.5 μg/mL, respectively[31]. Therefore, our developed MEKC-MS method can be applied for the effective determination of warfarin enantiomers in human plasma.

Both UV and MS detections were conducted simultaneously in which solutes were first detected by UV detector by placing the UV-alignment interface at 60 cm from the inlet end of the capillary, and then ESI-MS detection was performed at the outlet end of the capillary (ca. 120 cm). It is clear from Fig. 3 that Rs remains essentially the same when peaks are detected at an effective length of 60 cm for UV or at 120 cm for MS. As we have discussed earlier, when the capillary is inserted in the nebulizer, the resolution is deteriorated due to suction effect at the outlet end of capillary. Thus, the use of longer capillary provided no significant gain in resolution due to the suction effect.

Fig. 3.

Simultaneous UV and MS detection of (±)-WAR and (±)-COU at the LOD (5μg/mL) of MEKC-UV.

The MEKC-UV detection at 254 nm provided a LOD of 5 μg/mL at S/N =3. However, the S/N only increase ~two fold at 214 nm (S/N =5, data not shown). On the other hand, MEKC-MS provided much higher sensitivity (5 μg/mL at S/N ≥15) of WAR enantiomers (Figure 3). The LOD for MEKC-MS was 0.1 μg/mL (S/N =3) (chromatogram not shown). Therefore, it is clear that much lower LODs for can be reached in MEKC-ESI-MS when polymeric surfactant is used as chiral additive than MEKC-UV which is consistent with our previous comparison for other chiral analytes [22–24].

The developed MEKC-MS assay was next applied to the analysis of warfarin enantiomers in three patients undergoing warfarin therapy. Fig. 4 shows several overlaid electropherograms for determination of (R)-WAR and (S)-WAR in human plasma by the chiral MEKC-ESI-MS. This includes a blank human plasma spiked with (±)-WAR standard (2 μg/mL) and (±)-COU (internal standard, 2 μg/mL) (Fig. 4A), two normal patients plasma (Fig. 4B and 4C), and a mutant gene (CYP2C9*2 or*3) patient plasma (Fig. 4D). Although the S/N of (±)-COU is rather low, this can be improved by increasing the injection time or the use of higher (±)-COU concentration as very high resolution was obtained. The WAR R/S ratio in normal patient’s plasma samples were found to be 2.24 (Fig. 4B) and 6.20 (Fig. 4C), respectively. It is well-documented that after oral administration of a WAR racemic mixture, concentrations of R-enantiomer in blood plasma is higher than S-enantiomer because of stereoselective metabolism [1]. However, for mutant gene patient’s sample (Fig. 4D), the warfarin R/S ratio was found to be much lower (i.e.,0.27). Therefore, it appears that the S-enantiomer of WAR is metabolized much slower than R-enantiomer in a mutant gene.

Fig. 4.

Determination of (R)-WAR and (S)-WAR concentration and enantiomeric ratio in human plasma samples. The conditions are the same as in Fig. 2. (A) Blank plasma spiked with racemic warfarin (2 μg/mL) standard and coumachlor (2 μg/mL, I. S.); (B) and (C) Normal patient plasma spiked with 2 μg/mL of coumachlor [ B: (R)-WAR = 0.80 μg/mL; (S)-WAR = 0.35 μg/mL; R/S = 2.24 and C: (R)-WAR = 2.30 μg/mL; (S)-WAR = 0.38 μg/mL; R/S = 6.20 ]; (D) Mutant gene (CYP2C9*2 or*3) patient plasma spiked with 2 μg/mL of coumachlor [(R)-WAR = 0.67μg/mL; (S)-WAR= 2.5 μg/mL; R/S= 0.27)].

4. Conclusions

For the first time, a specific and sensitive MEKC-ESI-MS method for the analysis of (R)-WAR and (S)-WAR enantiomers has been developed, using a polymeric surfactant, poly-L, L-SULV, as a pseudostationary phase. While the HPLC MS/MS method reported in the literature[9] is faster and sensitive, the lack of achiral selectivity of the β-cyclodextrin column resulted in co-elution of WAR enantiomers with the internal standard (COU). This suggests that HPLC-MS method will provide co-elution if attempted for the simultaneous enantioseparation of several of the positional and optical isomers of warfarin hydroxylated metabolites of identical m/z. It is widely known that the chiral columns are more expensive, requires large volumes of organic solvent which in turn increases their disposal cost. In addition, large volumes of sample requirement in HPLC-MS also means that the technique is not very well suited for the biological samples that are volume-limited.

In contrast to HPLC-MS the most attractive feature of MEKC-MS is its sample requirement (e.g., few nanoliters) [10]. An additional advantage of MEKC-MS is very low consumption of inexpensive chiral surfactant usually either added to the run buffer. Our results suggest that MEKC-MS assay may be applied to the analysis of plasma samples of patient’s undergoing (±)-WAR therapy if further improvement and method validation are conducted. For example, note that our developed MEKC-MS method is based on a single quadrupole MS which is at least an order of magnitude less sensitive than the current state-of-the-art triple quadrupole MS. Further investigation is underway for simultaneous enantioseparation of (±)-WAR and its mono-hydroxylated metabolites in plasma samples. Such studies may provide us some new insights in stereoselective and regioselective metabolisms of this anionic chiral drug in plasma samples of patient’s with normal vs. mutated gene [32].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. GM 62314). The authors would like to thank Drs. Michael Jann, Andrea Redman and Christine Hon (Mercer University) for providing us the blank plasma and patient plasma samples profiled in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Toon S, Low LK, Gibaldi M, Trager WF, O’Reilly RA, Motley CH, Goulart DA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;39:15. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henne KR, Gaedigk A, Gupta G, leeder JS, Rettie AE. J Chromatogr B. 1998;710:143. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi H, Kashima T, Kimura S, Muramoto N, Nakahata H, Kubo S, Shimoyama Y, Kajiwara M, Echizen H. J Chromatogr B. 1997;701:71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ring PR, Bostick JM. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2000;22:573. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naidong W, Ring PR, Midtlien C, Jiang X. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2001;25:219. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lombardi R, Chantarangkul V, Cattaneo M, Tripodi A. Thromb Res. 2003;111:281. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osman A, Arbring K, Lindahl T. J Chromatogr B. 2005;826:75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coe RA, Rathe JO, Lee JW. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;42:573. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidong W, Ring PR, Midtlien C, Jiang W. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2001;25:219. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamsi SA, Miller BE. Electrophoresis. 2004;23–24:3927. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamsi SA. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:4036. doi: 10.1002/elps.200290017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jäverfalk EM, Amini A, Westerlund D, Andren Per E. J Mass Spectrom. 1998;33:183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherkaoui S, Rudaz S, Varesio E, Veuthey JL. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:3308. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200109)22:15<3308::AID-ELPS3308>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka Y, Otsuka K, Terabe S. J Chromatogr A. 2000;875:323. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)01334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka Y, Kishimoto Y, Terabe S. J Chromatogr A. 1998;802:83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mol R, de Jong J, Somsen GW. In: Electrokinetic Chromatography: Theory, Instrumentation and Applications. Pyell U, editor. John Wiley and Sons; Chischester, England: 2006. p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaki H, Itou N, Terabe S, Takada Y, Sakairi M, Koizumi H. J Chromatogr A. 1995;716:69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozaki H, Terabe S. J Chromatogr A. 1998;794:317. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihama Y, Katayama H, Asakawa N. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:45. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersson P, JÖrntén-Karlsson M, Stålebro M. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:999. doi: 10.1002/elps.200390144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamsi SA. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5130. doi: 10.1021/ac012412b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbay C, Rizvi SAA, Shamsi SA. Anal Chem. 2005;(77):1672. doi: 10.1021/ac0401422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou JG, Rizvi SAA, Zheng J, Shamsi SA. Electrophoresis. 2006;(27):1263. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou JG, Zheng J, Rizvi SAA, Shamsi SA. Electrophoresis. 2007 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou JG, Zheng J, Shamsi SA. Electrophoresis. 2007 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizvi SAA, Zheng J, Shamsi SA. Anal Chem. 2007;79:879. doi: 10.1021/ac061228t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamsi SA, Macossay J, Warner IM. Anal Chem. 1997;69:2980. doi: 10.1021/ac970037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizvi SAA, Simons DN, Shamsi SA. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:712. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agnew-Heard KA, Sanchez Pena M, Shamsi SA, Warner IM. Anal Chem. 1997;69:958. doi: 10.1021/ac960778w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chankvetadze B. Capillary Electrophoresis in Chiral Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2001. p. 1346.p. 1791. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Fasco MJ, Huang Z, Guengerich FP, Kaminsky LS. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]