Summary

Background

Studies in Afghanistan have shown substantial mental health problems in adults. We did a survey of young people (11–16 years old) in the country to assess mental health, traumatic experiences, and social functioning.

Methods

In 2006, we interviewed 1011 children, 1011 caregivers, and 358 teachers, who were randomly sampled in 25 government-operated schools within three purposively chosen areas (Kabul, Bamyan, and Mazar-e-Sharif municipalities). We assessed probable psychiatric disorder and social functioning in students with the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire multi-informant (child, parent, teacher) ratings. We also used the Depression Self-Rating Scale and an Impact of Events Scale. We assessed caregiver mental health with both international and culturally-specific screening instruments (Self-Reported Questionnaire and Afghan Symptom Checklist). We implemented a checklist of traumatic events to examine the exposure to, and nature of, traumatic experiences. We analysed risk factors for mental health and reports of traumatic experiences.

Findings

Trauma exposure and caregiver mental health were predictive across all child outcomes. Probable psychiatric ratings were associated with female gender (odds ratio [OR] 2·47, 95% CI 1·65–3·68), five or more traumatic events (2·58, 1·36–4·90), caregiver mental health (1·11, 1·08–1·14), and residence areas (0·29, 0·17–0·51 for Bamyan and 0·37, 0·23–0·57 for Mazar-e-Sharif vs Kabul). The same variables predicted symptoms of depression. Two thirds of children reported traumatic experiences. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress were associated with five or more traumatic events (3·07, 1·78–5·30), caregiver mental health (1·06, 1·02–1·09), and child age (1·19, 1·04–1·36). Children's most distressing traumatic experiences included accidents, medical treatment, domestic and community violence, and war-related events.

Interpretation

Young Afghans experience violence that is persistent and not confined to acts of war. Our study emphasises the value of school-based initiatives to address child mental health, and the importance of understanding trauma in the context of everyday forms of suffering, violence, and adversity.

Funding

Wellcome Trust.

Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health is an important issue on the international public health agenda.1 According to researchers working in conflict zones, however, there is still a serious dearth of systematic empirical information about war-affected and displaced youth.2 Published reports have mainly focused on the identification of traumatic stress and other negative sequelae of war. There is a need to broaden the evidence in conflict and disaster settings to examine all psychosocial dimensions of mental health,3,4 and to identify factors underlying both vulnerability and resilience5 to social and economic upheaval in the wake of war. Published work emphasises crucial gaps in research, policy, and practice for war-affected children,6–8 which demand rigorous research to gain informed understanding of psychosocial wellbeing and mental health. In this context, a child-focused assessment of trauma, suffering, and social functioning is essential.

Afghanistan has endured a combination of armed conflict, widespread poverty, and social injustice. Education and health-care systems have been severely crippled, as are community networks of social support.9,10 Large-scale surveys have shown a broad spectrum of mental health problems in the adult population—including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress—associated with sex and exposure to traumatic events.11,12 However, no systematic survey has focused on young people, although an unpublished UNICEF study in 1997 reported that, among the 300 children interviewed in Kabul, 90% thought that they would die in the war, whereas 80% said they were sad, frightened, and unable to cope with life.13 Conversely, a qualitative study led by Save the Children in 2001–02,14 of 436 children and 215 adult carers in Kabul, argued that the lives of young Afghans were not dominated by fear and war-related trauma.

We did a large-scale survey of mental health in three areas of Afghanistan. To assess child mental health and life adversity from the viewpoint of several informants, we interviewed children, caregivers, and teachers in schools. Schools were the best point of contact for drawing a community sample, ensuring interview privacy, and delivering a complex protocol. We could not overcome barriers to a systematic sampling of families whose children were not sent to school. However, since the fall of the Taliban in 2001, school attendance has grown exponentially for both girls and boys in primary and secondary education. In 2004–05, estimates were that 64% of 7–14-year-old children—48% of girls and 77% of boys—were enrolled nationally,15 and in central and northern Afghanistan demand is especially high. Our aim was to focus on the needs of 11–16-year-old students who were regarded as old enough to report adverse experiences, health, and social functioning. In line with an integrative approach bridging medical and social understandings of war-related trauma,16 we assessed the nature of mental health problems, testing specific associations with sex, traumatic events, caregiver mental health, and sociodemographic characteristics. We also examined exposure to, and nature of, traumatic experiences.

Methods

Study design

From April 26, to Dec 12, 2006, we did a two-stage, school-based cross-sectional survey, interviewing students and their primary caregivers and teachers (figure 1). To capture a range of historical, social, and economic experiences, we selected three research sites (Kabul, Bamyan, and Mazar-e-Sharif municipalities) in central and northern Afghanistan, excluding areas in the south and southeast for security reasons. We built on similar surveys in 2004 in Wardak province where schools could not be randomly selected, and in 2005 in Afghan refugee camps of Pakistan where the protocol was successful, enabling us to refine rapport-building strategies and test instrument reliability.

Figure 1.

Sampling for a two-stage, stratified random survey

We adopted a stratified random-sampling design. Because school records were not centrally available, exhaustive lists of all state-operated schools (n=257 in the three areas), with size of student population, had to be obtained from local administrative offices. In the first stage of sampling (figure 1), we drew a random sample of 25 schools, with probability sampling proportional to size, and with additional stratification in Kabul across its 16 educational zones to achieve spread across city areas. To provide balanced geographical and sex coverage, we selected eight or nine schools per research site, with equal numbers of boys and girls per school (we drew a total of 14 single-sex schools and 11 co-educational schools). For each participating school, we enlisted teachers to compile up-to-date, age-specific class lists for grades 5–10, which cater for 11–16-year-old students. Because of curtailed education under the Taliban regime, each grade includes a wide age range of students.

In the second stage of sampling, we drew a random sample of students, selecting a minimum of 40 participants from each school (20 boys and 20 girls from co-educational schools, which hold separate morning and afternoon shifts for opposite sexes).

We aimed for 290 participants per area, on the basis of power calculations from pilot work that used identical screening instruments with 11–16-year-old Afghan schoolchildren, caregivers, and teachers (α=0·05, two-sided test to detect a 5% difference in prevalence rates for primary outcomes). Our target sample was 15% above this number. Rapport was developed by initiating school-based activities before the survey, offering small, locally-appropriate gifts to respondents (eg, refreshments or notebooks) and schools (eg, heaters and water coolers), and health checks on nutritional status and blood pressure (but not medical care). All selected students agreed to participate and were keen to be interviewed because of the novelty of our research activity. Caregivers (adults with direct responsibility for the children) were recruited through the students. They included male or female parents or other relatives, reflecting the strict gender segregation of daily life and the role of extended families in childcare. To do 40 multi-informant interviews within 10 days for every school, we contacted 1260 students, met with 1021 caregivers (81%), and interviewed 1020 within the allocated time; only one father refused to participate. If a caregiver did not come to school, we could not obtain informed consent, and therefore did not interview the child. Teachers repeatedly asked why all students could not be included; as a matter of courtesy, we interviewed (but excluded from the dataset) a few keen volunteers, unselected by random procedures.

A small team of well-trained researchers moved sequentially from school to school, which maximised data quality and comparability, and rapport and participation. Field researchers, already experienced interviewers, were given 3-weeks' field training by the senior academics and project manager. Training included interview techniques sensitive to gender, age, and ethnic origin, and measurement of health status. Blood pressure measurements helped to establish rapport with participants; high or low blood pressure is a local idiom for anxiety or depression, respectively. Three male and three female staff (fluent in Dari and Pashto) were contracted for 8 months to interview students, caregivers, and teachers in face-to-face, private encounters on school premises. One professional translator handled all verbatim data. An Afghan doctor helped with health checks and referrals. Two Afghan clinical psychologists were involved in piloting and reviewing instruments.

The project manager, fluent in English and local languages, liaised with schools, explained the survey to participants, checked completed questionnaires every day, and verified translations of verbatim data. Study investigators were on-site during staff training, instrument pretesting and review, data collection, translation, and assessment. The protocol was approved by Durham University, the Ministry of Education in Kabul, its subsidiary departments in Kabul, Bamyan, and Mazar-e-Sharif, and all school directors. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians first, then from children and class teachers, in verbal form.

Screening

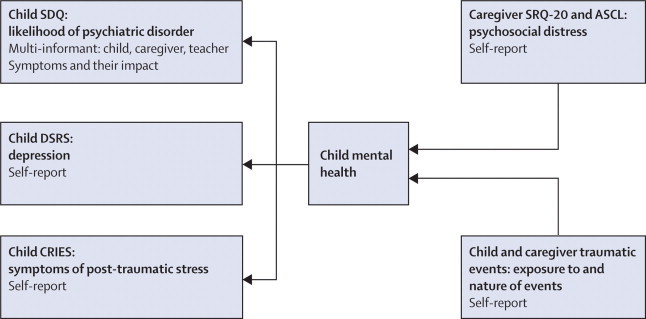

We used several screening instruments for child and adult mental health (figure 2), which were chosen on the basis of simplicity, reliability, good psychometric properties for the target group,17 and extensive use for research in schools, as well as surveys in low-income, conflict, or disaster settings (eg, in Gaza, Bosnia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan; webappendix pp 1–3). If no clinical revalidation is possible, such instruments effectively screen for probable mental health disorders and/or symptoms of distress in children and adolescents. An Afghan clinical psychologist, with professional experience in Afghanistan and the UK, translated instruments from English to Dari and Pashto. Independent of each other, one professional translator and one linguist undertook blind back-translations.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework

Psychometric questionnaires included the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), the Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS), the Child Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES), the Self-Reported Questionnaire (SRQ-20), and the Afghan Symptom Checklist (ASCL).

Sets of translations and back-translations were systematically reviewed for content validity by an Afghan group of bilingual or trilingual fieldworkers and academic staff with expertise in social work, anthropology, and clinical psychology, then vetted by experts in psychology or psychiatry from the UK and the USA. Three extensive pilot surveys, including measurement (test–retest) reliability, were done in Afghan communities (Wardak, Peshawar, and Kabul). These steps conformed to procedures for preparing instruments in transcultural research.18

The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was implemented with students, primary caregivers, and main teachers to identify children for whom a psychiatric disorder was unlikely, possible, or probable. The SDQ is a simple and effective screening tool that provides balanced coverage of behavioural, emotional, and social issues,19,20 and can be self-completed by children aged 11 years or older. Four sub-scales (assessing emotional, behavioural, hyperkinetic, and peer problems to reflect ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria) yield a total score for mental health difficulties, and a fifth taps strengths (prosocial behaviour). Supplementary questions measure the impact of a child's difficulties in terms of distress and interference with everyday home life, friendship, classroom learning, or leisure activities. The SDQ predicts psychiatric disorders on the basis of both symptoms and their impact, and can triangulate ratings across child, parent, and teacher responses, which proves more accurate than ratings from only one informant.21,22 Single-informant SDQ ratings have been used and validated in Bangladesh,23 Pakistan,24,25 Yemen,26 and Gaza.27 The multi-informant categorisation of children28 can be achieved by a computerised algorithm predicting that disorders are likely to be present where symptom scores exceed 95th centiles and impact scores are definite or severe. This algorithm has been validated in the UK and Bangladesh,23,28 and works equally well in both settings. We developed SDQ versions in both Dari and Pashto. Two other instruments were given to students. The Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) is a brief screening tool (18 items, 3-point scale) for child depressive symptoms,29 which discriminates effectively between severely and non-severely depressed children, although various cutoff points are used in publications. The Child Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES-13 items, 4-point scale) measures the impact of traumatic experiences; scores of 17 or more for the 8 items relating to intrusion or avoidance indicate a level of distress consistent with post-traumatic stress.30 We developed DSRS and CRIES versions in Dari and Pashto for the Children and War Foundation.

For caregiver mental health, we used two screening tools, one international and one culturally specific, validated for Afghanistan.31–33 The Self-Reported Questionnaire (SRQ; 20 items, yes/no responses) is recommended for epidemiological research in low-income countries.31,34 The Afghan Symptom Checklist (ASCL; 23-items, 5-point scale) was developed specifically in Kabul to measure psychological distress with culturally specific terminology.32,33

For both children and caregivers, we implemented a traumatic events checklist adapted from the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire35 and the Gaza Traumatic Event Checklist.36 Our review panel selected 20 (yes/no) items covering various events pertinent to Afghanistan, differentiating, where appropriate, direct experience from witnessing or hearing reports of an event, and one yes/no item to allow for any other traumatic experience. Two additional items obtained information about which lifetime event had been the most distressing (from those reported), and when it had occurred. All participants were given the time and opportunity to explain responses in depth, allowing for contextualisation of meaning, time, and place for all items reported. Interviewers recorded statements verbatim. For students, we implemented CRIES for the event reported as most distressing.

Sociodemographic data (eg, displacement, economic status, education, household characteristics) were obtained from caregivers. We featured different markers of financial security, including a material wealth index (MWI) based on household ownership of 15 prespecified items. Other data (health checks, interviews on aspirations, and social environment) are not reported here.

Statistical analysis

We used binary SDQ outcomes (probable vs possible or unlikely psychiatric disorder) with a standard algorithm based on multi-informant ratings of symptoms and impact scores.22,23 We also used binary outcomes for CRIES to assess current psychological impact of the most (if any) distressing item reported (table 1). We used the full range of scores for other outcomes (DSRS, SRQ-20, and ASCL) to show results per unit increase (additional symptom reported on a dimensional scale) rather than arbitrary or disputed thresholds to discriminate poor or good mental health.31 Psychometric scales showed good internal reliability (Cronbach's α>0·74 for child and α>0·84 for adult outcomes).

Table 1.

Mental health status of Afghan 11–16-year-old students and caregivers

| Male (n=503) | Female (n=508) | Total (n=1011) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child's probable psychiatric disorder | |||

| SDQ multi-informant ratings, any disorder | 70 (13·9% [10·9 to 17·0]) | 154 (30·3% [26·3 to 34·3]) | 224 (22·2% [19·6 to 24·7]) |

| Emotional | 51 (10·1% [7·5 to 12·8]) | 131 (25·8% [22·0 to 29·6]) | 182 (18·0% [15·6 to 20·4]) |

| Conduct | 20 (4·0% [2·3 to 5·7]) | 29 (5·7% [3·7 to 7·7]) | 49 (4·8% [3·5 to 6·2]) |

| Hyperkinetic | 1 (0·2% [−0·2 to 0·6]) | 2 (0·4% [−0·2 to 0·9]) | 3 (0·3% [−0·1 to 0·6]) |

| Child's symptoms of depression | |||

| DSRS score | 7·82 (3·67) | 8·83 (4·33) | 8·33 (4·05) |

| Child's symptoms of post-traumatic stress | |||

| CRIES scores in high range (≥17) | 106 (21·1% [17·5 to 24·6]) | 136 (26·8% [22·9 to 30·6]) | 242 (23·9% [21·3 to 26·6]) |

| Caregiver's mental health | |||

| SRQ-20 international instrument | 5·50 (3·74) | 9·43 (4·53) | 7·47 (4·59) |

| ASCL culturally-specific instrument | 38·02 (10·98) | 52·43 (15·82) | 45·26 (15·41) |

Data are mean (SD) or number (% [95% CI]).

We tested associations between three main outcomes (SDQ and CRIES with logistic regression, and DSRS with linear regression) and 11 a-priori risk factors: sex of child, exposure to trauma, residence area, ethnic origin, caregiver mental health, type of caregiver, child and parental education, age, displacement history, material wealth, and household demographic composition. We then built multivariate models (informed by a-priori hypotheses and univariate analyses) with five predictor variables in the following order: sex, traumatic events, caregiver mental health, residence area, and child age. We excluded other variables (eg, wealth and education) and potential effect modification (interaction with sex, age, or wealth) that had no significant effect on mental health outcomes. We present regression models with all five predictors to facilitate comparison across multiple outcomes (table 2). Statistical analyses were adjusted for within-school sex distribution and clustering by school and area (using STATA version 8.2), which accounts for the probability of selecting boys and girls in participating schools, and common variance within the clusters, producing robust standard errors and conservative estimates for group comparisons. Sensitivity analyses using linear or categorical data (eg, for trauma events) yielded similar findings.

Table 2.

Variables associated with child mental health outcomes

|

Likelihood of psychiatric disorder* |

Symptoms of depression† |

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | p value | Adjusted β coefficient | p value | Adjusted OR | p value | |

| Sex of child | ||||||

| Male | 1 | .. | .. | .. | 1 | .. |

| Female | 2·47 (1·65 to 3·68) | <0·0001 | 0·86 (0·24 to 1·48) | 0·009 | 1·16 (0·85 to 1·59) | 0·325 |

| Child exposure to traumatic events | ||||||

| None reported | 1 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| 1, 2 events | 0·97 (0·72 to 1·31) | 0·850 | −0·01 (−0·51 to 0·49) | 0·970 | 1 | .. |

| 3, 4 events | 1·07 (0·69 to 1·65) | 0·768 | 1·41 (0·63 to 2·19) | 0·001 | 2·05 (1·35 to 3·10) | 0·002 |

| ≥5 events | 2·58 (1·36 to 4·90) | 0·006 | 1·73 (0·70 to 2·77) | 0·002 | 3·07 (1·78 to 5·30) | <0·0001 |

| Caregiver's mental health problems | ||||||

| SRQ-20 (per symptom reported) | 1·11 (1·08 to 1·14) | <0·0001 | 0·07 (0·01 to 0·13) | 0·019 | 1·06 (1·02 to 1·09) | 0·002 |

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Kabul | 1 | .. | .. | .. | 1 | .. |

| Bamyan | 0·29 (0·17 to 0·51) | <0·0001 | −2·19 (−3·06 to −1·31) | <0·0001 | 1·15 (0·69 to 1·89) | 0·578 |

| Mazar | 0·37 (0·23 to 0·57) | <0·0001 | −2·42 (−3·29 to −1·55) | <0·0001 | 0·98 (0·70 to 1·37) | 0·893 |

| Child age | ||||||

| (Per year increase) | 1·00 (0·89 to 1·13) | 0·968 | −0·05 (−0·23 to 0·12) | 0·526 | 1·19 (1·04 to 1·36) | 0·016 |

Data are number (95% CI). OR=odds ratio. Analyses are adjusted for within-school sex distribution and clustering by school and residence area.

Multi-informant SDQ ratings (logistic regression for probable vs other outcome, n=1011).

DSRS scores reported by child (linear regression, n=1011).

CRIES scores reported by child (logistic regression for 0–17 vs ≥17, n=642 for sub-sample reporting exposure to traumatic experiences.

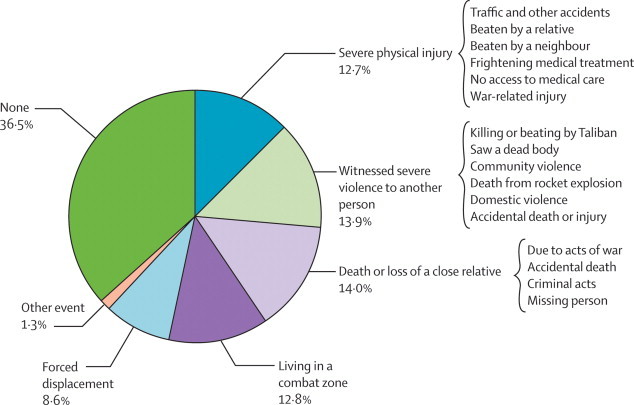

We analysed reports of trauma in terms of exposure and nature of events. For multivariate analysis, we examined the total number of events reported and four categories of exposure (0, 1 and 2, 3 and 4, or 5 or more events). For presentation, we grouped the 21 yes/no trauma event checklist items into six types of events: severe physical injury, witnessed severe violence to another person, death or disappearance of a close relative, living in a combat zone, forced displacement from home, and other event. We did this categorisation for all reported events (figure 3) and the most distressing lifetime event (figure 4). For the latter, we systematically reviewed respondent statements about the specific trauma reported. Content analysis of these verbatim descriptions,37 transcribed and reviewed manually by the research team in both English and vernacular languages, was used to categorise these reports into subtypes of traumatic experience. These subgroups are shown in figure 4 for three of six main categories to illustrate the range of events reported.

Figure 3.

Exposure to traumatic events (n=1011)

Figure 4.

Most distressing lifetime event (n=1011)

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of the study had no role in design or conduct of data collection or data analysis. The corresponding author had access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Our sample, which had equal sex representation across study sites, included 1011 students, 1011 primary caregivers, and each child's main classroom teacher (figure 1). Caregivers included 380 mothers (37·6%), 248 fathers (24·5%), and 128 close female (12·7%) or 255 male (25·2%) relatives (aunts or uncles, grandparents, or older siblings). The dataset excluded nine cases with missing variables of interest.

The mean age of students was 13·5 years (SD 1·6), with 5·7 years (1·9) of formal education. Eight of ten (82·7%) had been displaced because of conflict, economic reasons, or both, including 45·1% displaced three or more times (data not shown). One of ten children had lost one or both parents. Two of ten worked outside school hours. Unpaid work included service in market stalls or family-owned restaurants; paid work consisted of peddling goods, weaving carpets, and working as apprentices; boys earned less than 50 pence a week in apprenticeships. Most households (n=601, 59·4%) were rated as very poor or poor, being unable to feed, shelter, or clothe family members adequately. They averaged 5·6 (SD 3·2) MWI items: 532 (52·6%) had a piped water supply, 775 (76·7%) a radio, and 534 (52·8%) a mobile phone. Most mothers (n=723, 72·6%) and 358 (39·0%) fathers had no formal education (data not collected on deceased individuals).

Among students, 224 (22·2%) met the criteria for a probable psychiatric disorder as predicted by multi-informant SDQ ratings based on symptoms and impact scores (table 1). Sex differences were pronounced for any predicted psychiatric disorder, emotional disorders, and depression, with girls having poor mental health relative to boys (table 1; all p<0·0001). No significant sex differences were noted for CRIES, with 242 (23·9%) students having strong feelings of intrusion and anxiety indicative of post-traumatic stress. All measures of child mental health and social functioning were significantly associated, indicating agreement across multiple informants and different measures (correlations not shown). Associations between child and caregiver mental health were also strong (eg, p<0·0001 between a child's SDQ ratings and the caregiver SRQ-20). These associations remained significant after disaggregation by type and sex of caregiver.

Four variables independently predicted SDQ ratings: being a female child, exposure to multiple traumatic events, caregiver's symptoms of poor mental health, and residence in Kabul (table 2). The same variables were associated with symptoms of depression. As for CRIES, no associations were identified with sex or residence area, but only with number of traumatic events, caregiver mental health, and age of child. Material wealth and paternal or maternal education had no effect on child outcomes. The same results were obtained from analyses based on the culturally-specific ASCL instead of SRQ-20 for caregiver data.

Two risk factors—trauma exposure and caregiver mental health—were present across all three measures of child mental health. Exposure to five or more traumatic events was strongly predictive of poor outcomes (table 2). In particular, CRIES intrusion and avoidance scores showed a dose-response effect (with ORs increasing for three or four, and five or more events). The effect on children of caregiver mental health was also consistent, albeit modest (table 2). Other variables were significant for only one or two outcomes. Thus, child sex predicted SDQ ratings and symptoms of depression, but not CRIES (table 2).

Regarding traumatic events, 642 of all students (63·5% [60·5–66·5]) had at least one traumatic event (figure 3) and 8·4% [6·7–10·1] were exposed to five or more events. No sex differences existed by category of traumatic experiences (except forced displacement, p<0·036).

The most distressing lifetime trauma was related to violence; this encompassed injury, witnessing violence to another person, the death or disappearance of close relatives, living in a combat zone, and forced displacement (figure 4). In relation to injury, children reported serious accidents, severe beatings by relatives or neighbours, frightening medical treatments, and painful illnesses without medical care; only four respondents mentioned war-related events such as landmine injury. In relation to witnessing violence, children reported war-related events (summary executions or beatings during Taliban rule, deaths from rocket explosions, and mutilated or dead bodies), but also community and domestic violence. Deaths and losses of close relatives were mainly related to war, but also included accidents and criminal acts. The lifetime events reported as most distressing included both past and present exposure to violence, during the Taliban period and after the fall of their regime in 2001.

Discussion

Our school-based survey of child mental health in central and northern Afghanistan yielded systematic data for 11–16-year-old students. We provide evidence for several risk correlates, such as female gender, traumatic events, caregiver mental health, and residence area.

Our study shows the feasibility and value of working in schools to identify the nature and risk correlates of child mental health, using lay interviewers and brief screening instruments.34 Teachers said that they had not previously reflected on the effect that mental health difficulties could have for scholastic performance, and students commented that they had never previously been asked about their feelings related to school and home experiences. In this socially conservative context, many female caregivers had never been given the opportunity to visit the school or meet their child's teacher. Our study raised awareness of the importance of child mental health issues within school settings and suggests that school-based interventions could be well received.

Community interventions, in the form of school-based mental health programmes, are novel, localised initiatives in Afghanistan,38 but already advocated24 and successful39 in Pakistan, and for children affected by political violence in the West Bank and Gaza,40 and Indonesia.41 Afghan Government policy has recognised the need for public health interventions to alleviate trauma, mental health disorders, and psychological distress in the general population.10 There is, however, an acute shortage of qualified mental health care practitioners, constraints on the current provision of basic health and social services,42 and inherent challenges in creating effective youth-focused programmes.43,44 Emerging consensus advocates several layers of support for mental health programmes in emergency settings: those targeting the family and community, as well as those offering more specialist care for those in clinical need.4

We emphasise two robust predictors of poor mental health outcomes for young Afghans: exposure to multiple trauma and caregiver mental health. Exposure to multiple trauma is consistent with published findings. We draw attention, however, to the importance of everyday violence that is not only consequent on acts of war. This emphasis broadens understanding of trauma and places it in the context of everyday forms of suffering, violence, and adversity. The consistent, albeit modest, parent–child associations for mental health outcomes point to psychosocial suffering being embedded in household dynamics and shared adverse experiences. Our findings lend support to interventions that address mental health issues in the family and community, framing policies to strengthen whole family units and improve their access to basic social, health, and educational services.10

Gender differences in emotional problems for adolescents are well known across cultures.20,21 In our sample, girls showed a two-fold risk for predicted psychopathology compared with boys, and more symptoms of depression (table 1). Among Afghan adults, gender differences in mental health are pronounced.11,12,31 An unexpected finding20 is the burden of emotional and behavioural problems for boys (SDQ ratings for emotional disorders exceeded those for conduct disorders). Following other published work,45 we found no gender differences for symptoms indicating post-traumatic stress (as measured by CRIES).

Consistent with published research on war zones,5 exposure to traumatic events was strongly associated with mental health outcomes. The experience of five or more traumatic events trebled the risk of probable psychiatric disorders and post-traumatic stress, also increasing depression symptoms. Reports of trauma were related to violence, but not confined to acts of war: accidents, painful medical treatments, and beatings by close relatives or neighbours greatly outnumbered war-related events (involving landmines or combat) in reports of severe physical injury. There was ongoing exposure to violence: children who had witnessed relatives executed or beaten by Taliban and mujahideen militia were still exposed to community and domestic violence (eg, the beating of their mother or sibling by male relatives).

Child–caregiver associations were also consistent across multiple indicators of mental health status. We presented these associations in terms of each additional symptom reported by caregivers on a 20-point symptom scale rather than use SRQ-20 thresholds with disputed significance in the published literature.31,46 Thus, each additional symptom reported by caregivers increased the odds of multi-informant ratings for child psychiatric disorder by 11%. Results from analyses using the culturally-specific instrument (ASCL) for caregiver mental health were the same as those generated with the international instrument (SRQ-20; data not shown). A small but significant effect was also recorded for depression and CRIES, per additional caregiver symptom reported. Associations between child–caregiver mental health have not been previously reported in Afghanistan, but are consistent with the few studies on war-affected adolescents that were able to obtain parent and child data.5 Our data suggest that caregiver's mental health is correlated to the wellbeing of the young individuals under their care.

The greater burden of mental health problems in Kabul than in Bamyan and Mazar-e-Sharif was an unexpected finding of this survey, because violent conflict is etched in the social and political past of all three communities. Children living in Kabul showed higher rates of probable psychiatric disorder and increased depression symptoms than children living in the other two areas, but no differences in symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress. Residence in Kabul was also a risk factor for caregiver mental health (data not shown). We relate area-specific findings to the multiplicity of current social and economic stressors in the capital,47–49 where overcrowding, high living costs, widening inequalities, pressure on resources, and day-to-day stressors might compound other adversities directly related to war. This explanation, while plausible, requires investigation.

Factors other than war-related trauma produce severe psychological distress in conflict-affected populations, but are often not given the attention they deserve.33 Two large-scale studies of adults in Afghanistan11,12 have shown high prevalence of mental health problems associated with female sex and exposure to traumatic events; however, in both surveys, the most common trauma was lack of food or water and ill-health without medical care. In other studies, adult mental health for Afghans was associated with day-to-day social stressors,47,48 poverty,46 and socioeconomic inequalities in access to housing, social care, and health care.50 In our study, poverty and lack of education predicted mental health outcomes for adult caregivers (data not shown), but not for children. One qualitative study14 focusing on children showed that psychosocial wellbeing was mainly affected by daily stressors such as environmental threats (eg, road conditions and traffic accidents). Daily stressors are not to be conflated with traumatic experiences. However, in the aftermath of war, the notion of trauma overlaps with that of social suffering, drawing significance from consequences in both medical and social domains.51

This perspective cautions against simplistic characterisations of trauma. In Afghanistan, there is a spectrum of violence—ranging from armed insurgency to family conflict—which generates sudden pain and persistent suffering. Our data suggest that, in Afghan children's lives, everyday violence matters just as much as militarised violence in the recollection of traumatic experiences. As their most traumatic lifetime experience, respondents identified trauma events linked to physical and social stressors with great repercussions on family dynamics, safety, and health (figure 4). Some children identified severe domestic beatings, a severe accident, or a frightening medical treatment as more traumatic than having witnessed parents and grandparents being killed in rocket attacks. Conversely, others identified as their most severe trauma the death of a relative killed in the past rather than recurrent distressing experiences of severe domestic beatings. The selective prioritisation of a particular event does not mean that it is, by itself, the cause of mental distress.3 However, it suggests that children assign significance to war-related, community, and family traumatic events on the basis of their current life circumstances and needs.52

Evidence of psychological suffering must be balanced, however, against evidence of fortitude and coping with adversity. Our survey data fall just within the expected range for emotional and behavioural disorders in children—namely, an overall rate of 10–15% in children in the general population, which can increase up to 20% in regions of socioeconomic adversity.53 Thus, 22·2% (95% CI 19·6–24·7) of students met multi-informant SDQ criteria for probable psychiatric rating, twice the rate (9·6%) found in UK national school-based surveys28 using the same method. Students, caregivers, and teachers reported many symptoms of mental health difficulties, but also rated the child's social functioning positively (across domains of home, classroom, social, and leisure activities). By age 11–16 years, Afghan teenagers live in a society with multiple exposures to adverse and violent events, affecting everyday personal and social experiences. In this study, 642 (63·5% [60·5–66·5]) child respondents reported exposure to traumatic events; 242 (23·9% [21·3–26·6]) showed substantial psychological distress in the wake of their most frightening lifetime event. The exposure to five or more traumatic events has striking consequences for mental health, but some measure of resilience exists in negotiating the effect of one or two traumatic experiences (table 2). Other published studies have emphasised that war-affected adolescents can have both severe symptoms of psychopathological illness and competent social functioning,3,54 and that focusing on symptoms, without examining social effects, leads to high rates of mental health disorders.55

This study has some limitations: sampling bias, respondent bias, and instrument diagnostic validity. Sampling bias was introduced by purposively choosing three geographical areas (not representative of the country overall) and failing to include children whose families could not, or chose not to, send them to school. Our survey captured a random sample of schoolchildren, yielding the first dataset on a growing proportion of Afghan boys and girls attending state-sponsored schools. Because children not attending school might be at greater risk of mental health disorder than those attending school,21 the sampling bias is likely to underestimate relations observed in our data.

A limitation of psychiatric research is that respondents have different competence and sensitivity when reporting mental health difficulties.21,22 Strict cultural prescriptions for gender segregation and assignment of responsibility for adolescents influenced which caregiver came for the interview (72% were fathers or male guardians for boys and 73% were mothers or female guardians for girls). Female caregivers, who suffered poorer mental health than male caregivers, might have rated their children more negatively, which would exaggerate sex-based associations between adult and child mental health. However, the study derives methodological strength from providing ratings on mental health difficulties and social functioning across three informants (children, caregivers, and teachers):28 this is almost never implemented in low-income or war-affected countries.21 Also, men and women might have been differentially inclined to report their distress or aggravate their problems to show a need for material assistance, although we paid careful attention to issues of communication, rapport, time, and privacy.

We used screening tools that are useful and valid in a range of western and non-western cultures, and in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries, but without clinical revalidation in Afghanistan. Our methodological strengths lie in the use of several instruments, with attention to cross-cultural reliability and validity.18,56 The multi-informant SDQ ratings go beyond symptoms: these systematically include respondents' own assessments of the functional and social significance of a child's mental health difficulties, in terms of causing distress and impairment in daily life. We are aware of debates regarding the relevance of absolute thresholds for community-wide screening across cultures31 and the important distinction between general psychological distress (suffering) and severe mental health disorder (pathology).57 Rather than seeking to establish prevalence rates for specific psychiatric disorders, we focus on risk factors for mental health problems and psychological distress, and the robustness of findings with different instruments.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The study was implemented through partnerships between Durham (UK) and Peshawar (Pakistan) universities, and an independent agency (ALTAI Consulting) based in Kabul. We thank Robert Goodman for reviewing back-translations to finalise versions of the SDQ (now copyrighted in Dari and Pashto); and Atle Dyregrov for making the Dari and Pashto versions of CRIES and DSRS available on the Children and War Foundation website.

Contributors

CP-B and ME wrote the report and assessed all data, with input from other investigators. CP-B, ME, and SS designed the study, pre-tested instruments, reviewed translations, trained staff, and oversaw the pilot and initial data collection. VG liaised with all government and school representatives, managed the local field team, and systematically checked all data. ME handled survey datasets and analysed verbatim interviews. CP-B took responsibility for data analyses.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Web Extra Material

References

- 1.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyden J, de Berry J. Children and youth on the front line: ethnography, armed conflict and displacement. Berghahn Books; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barenbaum J, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M. The psychosocial aspects of children exposed to war: practice and policy initiatives. J Child Psych Psychiatry. 2004;45:41–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Inter-agency Standing Committee; Geneva: 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betancourt T, Khan K. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris J, van Ommeren M, Belfer M, Saxena S, Saraceno B. Children and the Sphere standards on mental and social aspects of health. Disasters. 2007;31:71–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betancourt T, Williams T. Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. Intervention. 2008;6:39–56. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3282f761ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordans M, Tol W, Komproe I, de Jong J. Systematic review of evidence and treatment approaches: psychosocial and mental health care for children in war. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2009;14:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer N, Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Contracting out health services in fragile states. BMJ. 2006;332:718–721. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7543.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Social determinants of health in countries in conflict: a perspective from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; Cairo: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholte WF, Olff M, Ventevogel P. Mental health symptoms following war and repression in eastern Afghanistan. JAMA. 2004;292:585–593. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardozo BL, Bilukha OO, Crawford CAG. Mental health, social functioning, and disability in postwar Afghanistan. JAMA. 2004;292:575–584. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Put W. Addressing mental health in Afghanistan. Lancet. 2002;360:s41–s42. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11816-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Berry J, Fazili A, Farhad S, Nasiry F, Hashemi S, Hakimi M. The children of Kabul: discussions with Afghan families. Save the Children Federation; Kabul: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakhshi P, Trani J. Towards inclusion and equality in education? From assumptions to facts. National disability survey in Afghanistan 2005. Handicap International; Lyon: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein DJ, Seedat S, Iversen A, Wessely S. Post-traumatic stress disorder: medicine and politics. Lancet. 2007;369:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stallard P, Velleman R, Baldwin S. Psychological screening of children for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl. 1999;40:1075–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S. Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999;36:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achenbach TM, Becker A, Dopfner M. Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:251–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackett R, Hackett L. Child psychiatry across cultures. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1999;11:225–235. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullick MSI, Goodman R. Questionnaire screening for mental health problems in Bangladeshi children: a preliminary study. Soc Psych Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:94–99. doi: 10.1007/s001270050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman R, Renfrew D, Mullick M. Predicting type of psychiatric disorder from Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scores in child mental health clinics in London and Dhaka. Europ Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s007870050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syed E, Hussein S, Mahmud S. Screening for emotional and behavioural problems amongst 5–11-year-old school children in Karachi, Pakistan. Soc Psych Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samad L, Hollis C, Prince M, Goodman R. Child and adolescent psychopathology in a developing country: testing the validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Urdu version) Int J Methods Psychiatric Res. 2005;14:158–166. doi: 10.1002/mpr.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alyahri A, Goodman R. The validation of the Arabic SDQ and DAWBA. Eastern Medit Health J. 2006;12:S138–S146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thabet A, Stretch D, Vostanis P. Child mental health problems in Arab children: application of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:266–280. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:534–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birleson P, Hudson I, Buchanan D, Wolff S. Clinical evaluation of a self-rating scale for depressive disorder in childhood (Depression Self-Rating Scale) J Child Psych Psychiatry. 1987;28:43–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith P, Perrin S, Yule W, Haxam B, Stuvland R. War exposure among children from Bosnia-Hercegovina: psychological adjustment in a community sample. J Traumat Stress. 2002;15:147–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1014812209051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventevogel P, De Vries G, Scholte W. Properties of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) as screening instruments used in primary care in Afghanistan. Soc Psych Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:328–335. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller K, Omidian P, Yaqubi A. The Afghan Symptom Checklist: a culturally grounded approach to mental health assessment in a conflict zone. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:423–433. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller KE, Kulkarni M, Kushner H. Beyond trauma-focused psychiatric epidemiology: bridging research and practice with war-affected populations. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:409–422. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harpham T, Reichenheim M, Oser R. Measuring mental health in a cost-effective manner. Health Policy Planning. 2003;18:344–349. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mollica R, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Mental Dis. 1992;180:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thabet A, Vostanis P. Post-traumatic stress reactions in children of war. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th edn. AltaMira Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Berry J. Community psychosocial support in Afghanistan. Intervention. 2004;2:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman A, Mubbashar MH, Gater R, Goldberg R. Randomised trial of impact of school mental-health programme in rural Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Lancet. 1998;352:1022–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)02381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khamis V, Macy R, Coignez V. The impact of the classroom/community/camp-based intervention (CBI) program on Palestinian children. USAID; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tol W, Komproe I, Susanty D, Jordans M, Macy R, De Jong J. School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in Indonesia: a randomized cluster trial. JAMA. 2008;300:655–662. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldman R, Strong L, Wali A. Afghanistan's health system since 2001: condition improved, prognosis cautiously optimistic. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Berry J. The challenges of programming with youth in Afghanistan. In: Hart J, editor. Years of conflict: adolescence, political violence and displacement. Studies in forced migration. Berghahn Books; Oxford: 2008. pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostelny K. A culture-based, integrative approach: helping war-affected children. In: Boothby N, Strang A, Wessels M, editors. A world turned upside down: social ecological approaches to children in war zones. Kumarian Press; Bloomfield CT: 2006. pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heptinstall E, Sethna V, Taylor E. PTSD and depression in refugee children: Associations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stress. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0422-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Husain N, Chaudhry IB, Afridi MA, Tomenson B, Creed F. Life stress and depression in a tribal area of Pakistan. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:36–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzi H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcult Psychiatry. 2008;45:611–638. doi: 10.1177/1363461508100785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M, Mojadidi A, McDade T. Social stressors, mental health, and physiological stress in an urban elite of young Afghans in Kabul. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:627–641. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith D. Love, fear and discipline: everyday violence toward children in Afghan families. Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit; Afghanistan: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rasekh Z, Bauer H, Manos M, Lacopino V. Women's health and human rights in Afghanistan. JAMA. 1998;280:449–455. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleinman A, Das V, Lock M, editors. Social suffering. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones L, Kafetsios K. Assessing adolescent mental health in war-affected societies: the significance of symptoms. Child Abuse Neglect. 2002;26:1059–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thabet AAM, Abed Y, Vostanis P. Emotional problems in Palestinian children living in a war zone: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2002;359:1801–1804. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eyber C, Ager A. Poverty and displacement: youth agency in Angola. In: Carr S, Sloan T, editors. Community psychology and global poverty. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bird HB, Yager TJ, Staghezza B, Gould MS, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M. Impairment in the epidemiological measurement of childhood psychopathology in the community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:796–803. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199009000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Ommeren M. Validity issues in transcultural epidemiology. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:376–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Summerfield D. Trauma and the experience of war: a reply. Lancet. 1998;351:1580–1581. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.