Abstract

Melanocytes synthesize and store melanin within tissue-specific organelles, the melanosomes. Melanin deposition takes place along fibrils found within these organelles and fibril formation is known to depend on trafficking of the membrane glycoprotein Silver/Pmel17. However, correctly targeted, full-length Silver/Pmel17 cannot form fibers. Proteolytic processing in endosomal compartments and the generation of a lumenal Mα fragment that is incorporated into amyloid-like structures is also essential. Dominant White (DWhite), a mutant form of Silver/Pmel17 first described in chicken, causes disorganized fibers and severe hypopigmentation due to melanocyte death. Surprisingly, the DWhite mutation is an insertion of three amino acids into the transmembrane domain; the DWhite-Mα fragment is unaffected. To determine the functional importance of the transmembrane domain in organized fibril assembly, we investigated membrane trafficking and multimerization of Silver/Pmel17/DWhite proteins. We demonstrate that the DWhite mutation changes lipid interactions and disulfide bond-mediated associations of lumenal domains. Thus, partitioning into membrane microdomains and effects on conformation explain how the transmembrane region may contribute to the structural integrity of Silver/Pmel17 oligomers or influence toxic, amyloidogenic properties.

Keywords: Amyloid fibrils, Silver/Pmel17, Dominant White, Melanosome biogenesis, Protein sorting

Introduction

Melanocytes and retinal pigment epithelial cells synthesize and store melanin within a specialized organelle, the melanosome (Hearing, 2000; Marks and Seabra, 2001). Based on observations using the electron microscope, biogenesis of melanosomes involves four maturational stages (Seiji et al., 1963). Stage I melanosomes are spherical and essentially lack melanin; progression from stage I to stage II is characterized by elongation and appearance of a fibrillar internal matrix. Deposition of melanin on this melanosomal matrix becomes evident at stage III until the organelle is completely filled with melanin (stage IV) (Seiji et al., 1963). The fibrillar matrix is thought to participate in the conversion of toxic melanin intermediates to melanin and/or play a role in binding and retention of melanin precursors the release of which may be toxic to the cell (Chakraborty et al., 1996; Fowler et al., 2006; Lee et al., 1996). Structurally, the fibrillar striations resemble amyloid (Fowler et al., 2006) and appear to be proteinaceous with Silver protein (also known as Pmel17/gp100/Silv/ME20; referred to hereafter as Silver) as a major component (Berson et al., 2001). Thus Silver has also emerged as an important model for amyloid but the protein sorting pathways and structural events that participate in generating ordered striations important for organelle biogenesis and cell health are still not well understood.

Silver is a type I integral membrane protein that during biosynthesis undergoes O- and N-linked glycosylation, a modification that occurs in the Golgi (Raposo and Marks, 2007; Theos et al., 2005). Delivery of Silver to endosomal compartments and proteolytic processing yields a smaller membrane-bound fragment Mβ, and a larger fragment, Mα (Raposo and Marks, 2007; Theos et al., 2005). Disulfide bonds tether the luminal (Mα) and transmembrane (Mβ) fragments but upon arrival in endosomal compartments/stage I melanosomes, cleavage within Mβ releases the remaining fragments and Mα participates in the formation of fibrils (Kummer et al., 2009; Raposo and Marks, 2007; Theos et al., 2005).

The Dominant White (DWhite) mutation first described in chicken is due to the insertion of three amino acids (tryptophan/alanine/proline, WAP) into the transmembrane domain (Kerje et al., 2004) and, in vivo, results in a hypomelanotic phenotype (Brumbaugh, 1971) most likely due to melanocyte death (Hamilton, 1940; Jimbow et al., 1974). By electron microscopy, melanosomes of heterozygotes appear round and lack organized fibrillar structures (Brumbaugh and Lee, 1975). A cDNA to DWhite (MMP115) isolated from cultured pigmented epithelial cells (PEC) of White Leghorn chickens (Mochii et al., 1991) led to the characterization of DWhite protein as a PEC-specific marker. A monoclonal antibody (MC/1) against the central portion of chicken Silver (chSilver), recognizes a protein of 115 kDa (Mochii et al., 1988) and by immunohistochemical observation, labels melanosomes in a melanoma cell line (Mochii et al., 1991). However, membrane trafficking or structural details that contribute to the defective formation of fibrils have not been analyzed and the mechanism of how DWhite alters the cell biology or biochemistry of Silver to result in melanocyte death and depigmentation remains unclear.

Although melanosome fibrils resemble amyloid associated with neurodegenerative diseases, ordinarily they play an important role in melanin storage (Fowler et al., 2007; Raposo and Marks, 2007). Mutations in Silver protein resulting in loss of fibrillar striations have now been described in mouse (Kwon et al., 1995; Martinez-Esparza et al., 1999), horse (Brunberg et al., 2006; Reissmann et al., 2007), cattle (Gutierrez-Gil et al., 2007; Kuhn and Weikard, 2007), dog (Clark et al., 2006), zebrafish (Schonthaler et al., 2005) and chicken (Kerje et al., 2004) and the importance of trafficking and processing of Silver in the production of organized fibrils and melanocyte health is beginning to emerge (see (Raposo and Marks, 2007; Theos et al., 2005) for recent reviews). The premature truncation of murine Silver (mSilver) protein is thought to destabilize melanocytes (Martinez-Esparza et al., 1999), and the marked loss of mature melanosomes as well as HMB45 immunoreactivity is associated with trafficking defects (Theos et al., 2006a). These observations and the desire to understand how the cell avoids toxicity, prompted us to determine whether DWhite affects trafficking and/or processing of mutant Silver. The dominant-negative phenotype of the mutation also suggested that DWhite interferes with the function of wild-type Silver by disabling multimerization or causing non-functional multimers. We investigated the targeting and fibril assembly of DWhite by expressing human Silver (hSilver) alone or in combination with DWhite in primary cultures of mouse melanocytes or non-pigmented HeLa cells. We tested subcellular distribution, production of Mα interaction with lipids and organization into multimers. To our surprise, we detected no profound differences in subcellular localization. Instead, we found that the DWhite mutation affects partitioning into detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs). DWhite and hSilver proteins physically interact and this interaction correlates with loss of mature fiber. Examination of DWhite-hSilver complexes revealed that the consequence of the dominant negative role of DWhite is a specific alteration of how non-mutant Mα fragments are assembled.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Primary melanocytes were isolated from 1-day-old mice and were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 30 mM sodium bicarbonate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.35, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 ng/ml tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate and 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

HeLa cells were obtained from D. Shields (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and cultured in DME (4.5 g/l glucose), supplemented with 10 % FBS and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin.

Plasmids and transfections

Plasmids used: encoding rab5Q79L (J. Backer, Albert Einstein College of Medicine), hSilver (pCI-Pmel17) (M. Marks, University of Pennsylvania), and DWhite, (M. Mochii, University of Hyogo, Japan). Deletion of the three amino acids introduced by DWhite was done by QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Epitope-tagged derivatives of plasmids were generated by an in-frame insertion of hemagglutinin (HA) (YPYDYPDYA) or Myc (MEQKLISEEDLN) peptide sequences. All constructs were cloned in pcDNA3 and their sequences confirmed. Plasmids were transfected into cells using TransFectin (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions and medium was replaced after 4 h incubation. Cells were used for experiments 24 h after transfection.

Reagents and antibodies

Antibodies used were as follows: anti-myc (E biosource and Santa Cruz Biotechnology), -HA (Covance), -EEA1 and -caveolin-1 (Transduction Labs), -mannose-6-phosphate receptor (MPR) (D. Shields, Albert Einstein College of Medicine), -tyrosinase (Pep7) and -mSilver (Pep13) (V. Hearing, NCI/National Institute of Health), -hSilver-N terminus (Pmel-N) and C terminus (Pmel-C) (M. Marks, University of Pennsylvania), -Hmb50 (Neolabs), -HMB45 (Dako) and anti-guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) (P. Scherer, Albert Einstein College of Medicine). Horseradish peroxidase- and ALEXA-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories and Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, respectively. [35S]Methionine/cysteine (Expre35S35S) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Methionine/cysteine-deficient and complete DME, RPMI 1640 medium, leupeptin, pepstatin, and stock chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells grown on polylysine-coated coverslips were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature (RT), permeabilized and non-specific binding sites blocked by a 30-min incubation with 5% BSA 0.5% FBS, and 0.02% saponin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Primary antibodies were diluted 1:300 and ALEXA-conjugated secondary antibodies from Molecular Probes, 1:1000. Incubations were for 1 h (RT). Coverslips mounted on glass slides with Prolong Gold Antifade (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) were analyzed on a BioRad Radiance 2000 laser scanning confocal microscope. Standard filters with narrow emissions for imaging green and red channels were used, and absence of bleed through from one wavelength to a longer wavelength was achieved by balancing laser intensities with gain settings. Fluorescence signals were classified according to green, red, or yellow fluorescence using BioRad colocalization software and digital images were processed using Adobe Photoshop software (San Jose, CA).

Detergent extraction and rafts

Monolayers of cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, scraped off the dish then lysed in 1 ml 1% Triton X-100 buffer (25 mM MES, pH 6.9, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM iodoacetamide and a mixture of protease inhibitors (1 mU/ml aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin, 10 μM pepstatin, 5 mM EDTA, 1 μM E64)). Lysates were adjusted to 40% sucrose by addition of 80% sucrose before layering 35% sucrose, then 16% sucrose on top. After centrifugation at 100,000g for 12 h at 4 °C, 12 fractions were collected from top to bottom. Content of proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Subcellular fractionation

For sucrose gradient sedimentation, the cells were scraped and lysed in buffered 0.3 M sucrose plus protease inhibitors by eight passages through a 21-gauge needle followed by eight passages through a ball-bearing cell cracker with 0.002-inch clearance. Post nuclear supernatants of lysates were layered atop a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of 0.317 ml each of 0.8, 1.1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 M sucrose. The gradients were spun in a RP55S (Sorvall) rotor at 167,000g for 2 h. After centrifugation, 12 fractions, 0.18 ml each, were collected from the top.

Triton-insoluble fibrils were isolated essentially as described (Berson et al., 2003). Briefly, membrane pellets collected by sedimentation at 100,000g were resuspended in 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and a final concentration of 1% Triton X-100. Samples were incubated with rotation for 2 h at 4 °C. Triton X-insoluble pellets were collected by a 15-min sedimentation at 20,000g. Pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with sonication and volumes adjusted to that of the soluble fraction. Soluble and pellet fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Antibodies to be used were coupled to anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-conjugated magnetic beads by 1 h incubation in lysis buffer at 4 °C and nutation. Beads were collected by magnet, and after washing, added to cell lysates.

Cells transfected to express Silver constructs were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, and a mixture of protease inhibitors. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 4 min and antibody-coated beads were added to the supernatants. For co-immunoprecipitation experiments, the incubations were done at 4 °C, for 4 h with nutating. Antibody-bound proteins were collected by magnet and after washes, beads were stripped by the addition of sample buffer and boiling. Magnetic particles were collected by magnet and supernatants were loaded for SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membrane. For Western blot analysis, nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in 5% milk protein, incubated with primary antibodies either for 1 h (RT) or overnight (4 °C). Detection of bound antibody was done with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and ECL.

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation

Cells were pulse labeled for 30 min with [35S]methionine/cysteine and chased for the indicated times. Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer and processed as above.

Size-exclusion chromatography

Cells were lysed in CHAPS or lauryl maltoside detergents, 10 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) buffer, pH 6.5, supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (1 mU/ml aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin, 10 μM pepstatin, 5 mM EDTA, 1 μM E64, and 10 mM iodoacetamide). Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 1000g for 5 min. Gel filtration of supernatant (1 mg/ml) was done by FPLC on a Superdex 300 column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and a fraction volume of 0.5 ml. Each column was calibrated with protein markers as molecular weight standards (thyroglobulin, 669 kDa; ferritin, 440 kDa; aldolase, 158 kDa; ovalbumin, 43 kDa). Collected fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and after transfer to nitrocellulose, immunoblots were probed with the indicated antibodies.

Results

DWhite mutation reduces formation of mature hSilver

Previous reports have demonstrated that processing of hSilver in a post-Golgi compartment yields Mα and Mβ fragments and that the lumenal domain Mα is strictly required in fibril formation (Berson et al., 2001, 2003). To begin to examine how the insertion of WAP into the transmembrane domain of chicken Silver (DWhite) may alter Mα associations, we constructed mammalian expression vectors of chSilver and DWhite epitope-tagged at the N- and/or C-termini (Fig. 1A). Potential influences of the epitope tag on protein trafficking were excluded by testing constructs in mouse melanocytes using immunofluorescence. MC/1 (anti-chSilver) and Pep13 (anti-murine Silver, mSilver) antibody labeling overlapped significantly regardless of which chSilver constructs the melanocytes expressed (data not shown). Based on these observations, the N-Myc and C-HA dual epitope-tagged chSilver/DWhite (schematic shown in Fig. 1B) was used for subsequent analysis, and outcomes were confirmed with constructs bearing single tags.

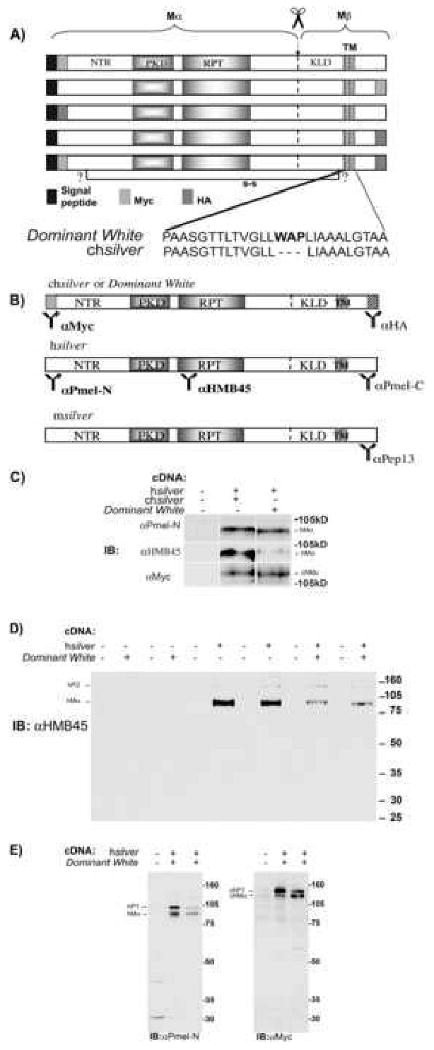

Fig. 1.

Expression of DWhite inhibits immunorecognition of hSilver by HMB45. (A) Schematic depiction of chSilver protein chimera fused to Myc and/or HA epitope tags. N-terminal signal peptide, lumenal domain (Mα), transmembrane domain (TM) and a short cytoplasmic sequence are indicated. Scissors specify a cleavage site that generates Mα and Mβ fragments. N-terminal region (NTR), polycystic kidney disease protein-1-like repeat domain (PKD), a domain of imperfect repeats (RPT) and “Kringle-like” domain (KLD) are also shown. Identity of cysteine residues that tether Mα to Mβ is currently not known and indicated by (?). The DWhite mutation is due to insertion of tryptophan, alanine and proline (WAP) into the transmembrane region. (B) Antibodies with the corresponding domains they recognize, ch- and hSilver constructs used in this study are indicated. Domains immunoreactive to anti-Myc, Pmel-N and HMB45 are shown in bold. (C) Combined expression of h- and chSilver or DWhite was analyzed by transient transfection of HeLa cells. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blots were probed with the antibodies as indicated. The HMB45-positive epitope is not affected by the presence of wild-type chSilver; HMB45-immunoreactive levels are reduced in the presence of DWhite. (D) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with hSilver and DWhite in duplicate and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot. Migration of MW protein standards is indicated on the right and the relevant bands by arrows on the left. HMB45 antibody recognizes protein bands of approximately 128 and 85 kDa corresponding to hP2 and hMα. HMB45 does not crossreact with DWhite protein. (E) HeLa cells transfected with hSilver and DWhite were processed as in (D) and immunoblots were probed with anti-Pmel-N or anti-Myc antibodies. MW standards are shown on the left. Pmel-N antibody detects bands of approximately 97 and 85 kDa, corresponding to hP1 and hMα. The anti-Myc antibody detects two bands of tagged chSilver of approximately 115 and 107 kDa, corresponding to chP1 and chMα. Antibody labeling is specific to the respective Silver isoforms and no crossreactivity is observed.

Antibodies to hSilver (shown in Fig. 1B) have been extensively characterized previously (Harper et al., 2008; Hoashi et al., 2006). N- or C-terminus-reactive antibodies (Pmel-N, Pmel-C, Fig. 1B) detect hSilver in premelanosome/stage I melanosomal compartments but not stage II melanosomes (Harper et al., 2008; Raposo et al., 2001) and Pmel-C does not identify fibrils (Berson et al., 2003). In contrast, the HMB45 antibody predominantly reacts with human Mα (hMα) or proteolytic fragments derived from hMα within organized fibrillar structures (Berson et al., 2001; Hoashi et al., 2006; Kikuchi et al., 1996; Kushimoto et al., 2001; Theos et al., 2005). Thus, to selectively evaluate the intracellular distribution and processing of DWhite relative to hSilver, we typically used N-terminus directed antibodies: Myc to chSilver, Pmel-N to hSilver (Fig. 1B, shown in bold typeface). To better understand the dominant-negative role of DWhite in mature fibril formation, we utilized the reactivity of HMB45 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1B, shown in bold typeface).

Since Pmel-N antibody targets the N-terminal 17 residues of hSilver (Berson et al., 2003) within the well conserved N-terminal region (NTR) (Theos et al., 2005), we checked if Pmel-N antibody recognizes epitopes on chSilver or DWhite (shown) proteins. We observed no cross reactivity (Fig. 1E).

The HMB45 epitope is located within the RPT domain (Harper et al., 2008; Hoashi et al., 2006) (schematic shown in Fig. 1B) with considerable sequence heterogeneity (Theos et al., 2005). Not surprisingly, the HMB45 mAb does not substantially recognize chSilver, wild type (not shown) or DWhite (Fig. 1D).

To avoid high background levels of endogenous HMB45 immunoreactivity in melanocytes, hSilver and chSilver, mutant and wild type were co-expressed in non-pigmented HeLa cells (Fig. 1C-E). As observed previously in Hela cells expressing hSilver alone, HMB45 primarily reacts with full-length Mα (∼85 kDa) (Harper et al., 2008; Hoashi et al., 2006) and not with the subsequent Mα cleavage products (∼30-60 kDa) that accumulate in melanocytes (Chiamenti et al., 1996; Kushimoto et al., 2001). The Pmel-N antibody detects the ER-associated precursor form P1, Golgi-modified P2 as well as the proteolytic fragment Mα (Berson et al., 2003; Harper et al., 2008).

When non-mutant chSilver was co-expressed with hSilver, the amount of HMB45-reactive hMα did not change (Fig. 1C, D). By contrast and consistent with its dominant inhibitory effect on organized fibrous striations within melanosomes (Brumbaugh and Lee, 1975) co-expressing hSilver and DWhite resulted in a dramatic decrease of HMB45 staining relative to Pmel-N-reactive hMα indicating a loss of mature structures (Fig. 1C, D).

The DWhite mutation does not affect targeting to premelanosomes/endosomes or processing

In general, stage I melanosomes are found near the perinuclear region, whereas stage II melanosomes distribute towards the cell periphery (Raposo et al., 2001). Indeed, when melanocytes were transfected with h- and chSilver cDNAs and the subcellular location of both proteins was determined by postfixation labeling, they were observed within punctate structures in the perinuclear region (DWhite and hSilver shown, Fig. 2A). Based on the location within the cell and the inefficiency of Pmel-N in detecting stage II melanosomes (Harper et al., 2008), colocalization of DWhite with hSilver-positive compartments is likely to represent correct targeting to stage I melanosomes. As the insets depicting enlarged areas demonstrate, hSilver exhibits a somewhat broader distribution to the cell periphery.

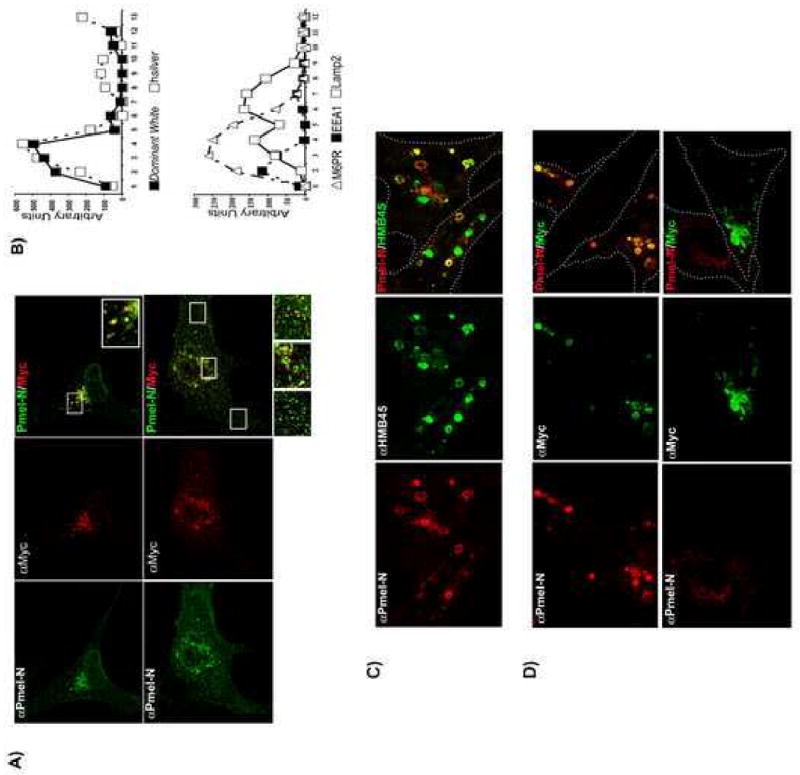

Fig. 2.

Subcellular distribution of hSilver and DWhite. (A) Melanocytes transiently expressing hSilver and DWhite were stained with antibodies as described in Materials and methods and observed by confocal microscopy. Overlapping and single channel images of immunolabeled hSilver (Pmel-N, green) and DWhite (Myc, red) are shown. Insets are enlargements of the boxed areas. (B, upper panel) Postnuclear supernatant of HeLa cells transiently expressing hSilver or DWhite was fractionated by sucrose gradient sedimentation. Twelve equal volume aliquots were collected from the top of the gradient and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B, lower panel) Distribution of endosomal/lysosomal markers. (C) HeLa cells transiently transfected to co-express constitutively active rab5Q79N, hSilver and DWhite were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-Silver antibodies: Pmel-N (red), HMB45 (green). Cell outlines are indicated by dotted lines in merged image. Formation of large vacuoles reflects rab5Q79N localization and a subpopulation of these rab5Q79N-positive endosomes is labeled by HMB45 but not Pmel-N antibody. (D) Experiment as in (C) was analyzed by using antibodies directed against the N-terminus of hSilver (Pmel-N, red) and DWhite (Myc, green). Two of the three cells expressing both constructs are in the plane of focus in D-upper panel. D-lower panel shows two cells; plane of focus is on the cell expressing DWhite and no detectable hSilver.

To avoid potential influence of endogenous mouse Silver (mSilver) and obtain more quantitative data on protein trafficking, each construct was expressed separately in HeLa cells and analyzed by sucrose gradient fractionation followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). The majority of Silver and DWhite proteins are recovered in nearly identical positions on the gradient and co-migrate with MPR-positive fractions (Fig. 2B, bottom panel). DWhite however, was excluded from dense sucrose fractions where a small percentage of hSilver accumulates.

Constitutively active rab5 (rab5Q79N) improves the detail of endosomal localization by producing enlarged vacuoles and the presence of internal vesicles identifies these enlarged organelles as multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (Volpicelli et al., 2001). By immuno electron microscopy, stage I melanosomes correspond to early MVB compartments and Silver protein content is readily revealed by the Pmel-N antibody (Raposo et al., 2001). During progression to stage II and the continued maturation of Silver protein, Pmel-N antibody reactivity declines and HMB45 reactivity shifts from limiting membranes to the fibrillar structures within the lumen of melanosomes (Raposo et al., 2001). To determine if the DWhite mutation influenced the production of mature fibrils by affecting distribution specifically to rab5-positive compartments, sorting of Silver protein to rab5Q79N enlarged vacuoles was examined (Fig. 2C). Expression of rab5Q79N clearly delineated the limiting membrane and lumenal compartment (Fig. 2C, D). In hSilver/rab5Q79N co-expressing HeLa cells, both HMB45 and Pmel-N antibodies label limiting membranes of rab5-positive organelles (Fig. 2C). Strong lumenal labeling of HMB45-reactive hSilver (Fig. 2C) was observed whereas, as expected, lumenal localization of hSilver detected by Pmel-N antibody was less evident. Localization to the vacuolar perimeter in a cell expressing no detectable hSilver (Fig. 2D, bottom panels) revealed clear access of DWhite to this endocytic compartment. Similar results were obtained when DWhite was expressed alone (not shown). Cell surface accessibility was determined by cell surface biotinylation experiments and found to be the same for wild-type and mutant Silver proteins (data not shown).

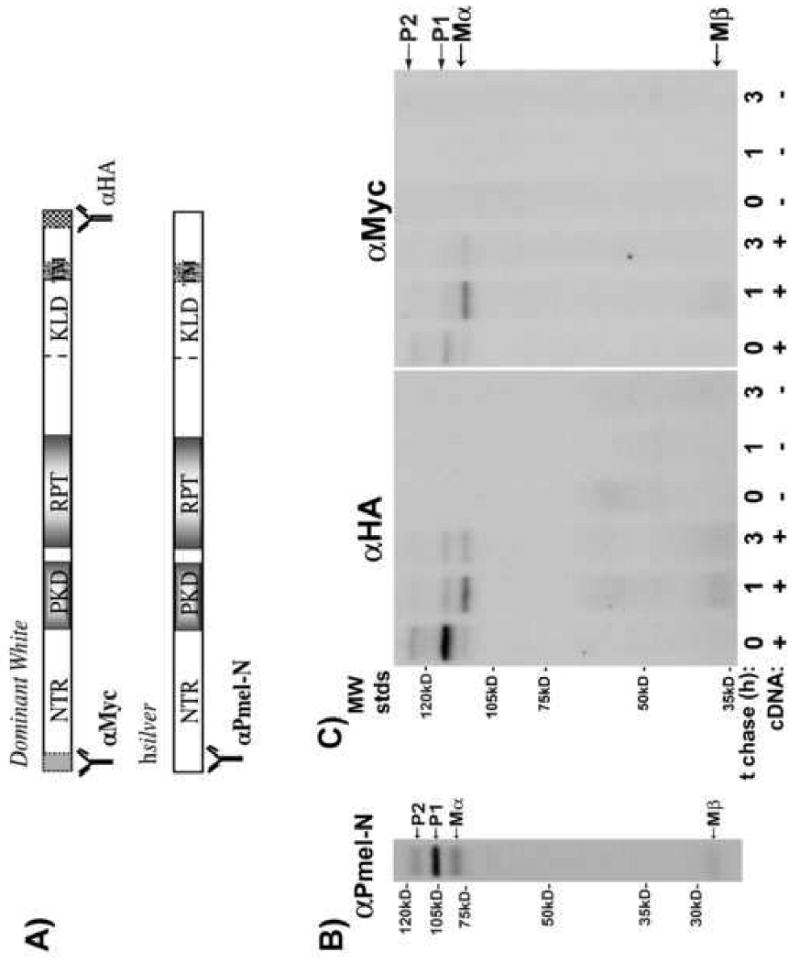

As another means to determine potential differences in targeting, we compared the kinetics of proteolytic processing of DWhite to those already described for hSilver (Berson et al., 2003). Metabolic pulse-chase analysis has demonstrated that newly synthesized hSilver (P1, ∼ 97 kDa) undergoes carbohydrate modification in the Golgi (P2, ∼128 kDa) and is further processed to Mα (∼85 kDa) and Mβ (∼38 kDa) fragments in an acidic, post Golgi compartment (Berson et al., 2001, 2003). Consistent with previous reports, when HeLa cells expressing hSilver are metabolically radiolabeled and chased, we can clearly identify P1, P2, Mα and Mβ fragments precipitated from lysates using the αPmel-N antibody at the 1-h time point (Fig. 3A). To determine the order of appearance of P1, Golgi-modified P2 forms and processing to Mα and Mβ peptides of mutant chSilver, HeLa cells expressing DWhite were pulse-labeled and chased for 1 to 3 h. DWhite protein is initially synthesized as a precursor (P1, ∼115 kDa) and after adjusting for the small contribution of the epitope tags, the difference in molecular weight to that of hSilver can be attributed to additional amino acid sequence deduced from the cloned cDNA (Kerje et al., 2004). Within one hour of chase, the intensity of P1 declines and the carbohydrate-modified P2 form (∼136 kDa) is recovered by both N- (myc) and C- (HA) terminus-directed antibodies. In agreement with previous reports for hSilver (Berson et al., 2001), within 1 h of chase, DWhite processing generates Mα (∼107 kDa) and Mβ (∼36 kDa) fragments the association of which can be confirmed by the ability to immunoprecipitate both peptides using either the anti-myc or -HA antibodies (Fig. 3B). Thus, the DWhite mutation does not affect trafficking to a post-Golgi processing compartment or the processing itself.

Fig. 3.

Processing of DWhite generates lumenal domain Mα. (A) Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation experiments and the regions of Silver protein they recognize are indicated. (B) HeLa cells expressing hSilver were labeled for 30 min with [35S]methionine/cysteine then chased for 1 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Pmel-N. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and bands visualized by fluorography. As reported previously, Mα and Mβ processed forms were observed within 1 h of chase. (C) HeLa cells expressing DWhite were radiolabeled in parallel for 30 min then chased for 0, 1 or 3 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (C-terminus) or anti-Myc (N-terminus) antibodies and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Mα and Mβ processed forms were observed within 1 h chase irrespective of the Silver protein the cells synthesized.

Silver proteins of mouse, chicken and human origin, interact

Although the subdomains of Silver proteins are highly conserved across species, the consensus of amino acid sequences between human and chicken Silver proteins falls off sharply (Theos et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the dominant-negative effect of the mutation on the production of mature fiber (Fig. 1C, D), predicts that DWhite and hSilver physically interact. To test for such interaction, we transiently co-expressed hSilver and DWhite constructs in melanocytes and non-pigmented HeLa cells and used a panel of antibodies to immunoprecipitate the respective proteins. As shown in Fig. 4A, mSilver protein is readily detected in immunoprecipitates of hSilver and DWhite from melanocyte homogenates. To confirm antibody specificity, the immunoprecipitation experiments were repeated with cell lysates from untransfected melanocytes. Antibodies to chicken or human Silver proteins do not cross-react with mSilver (Fig. 4B).

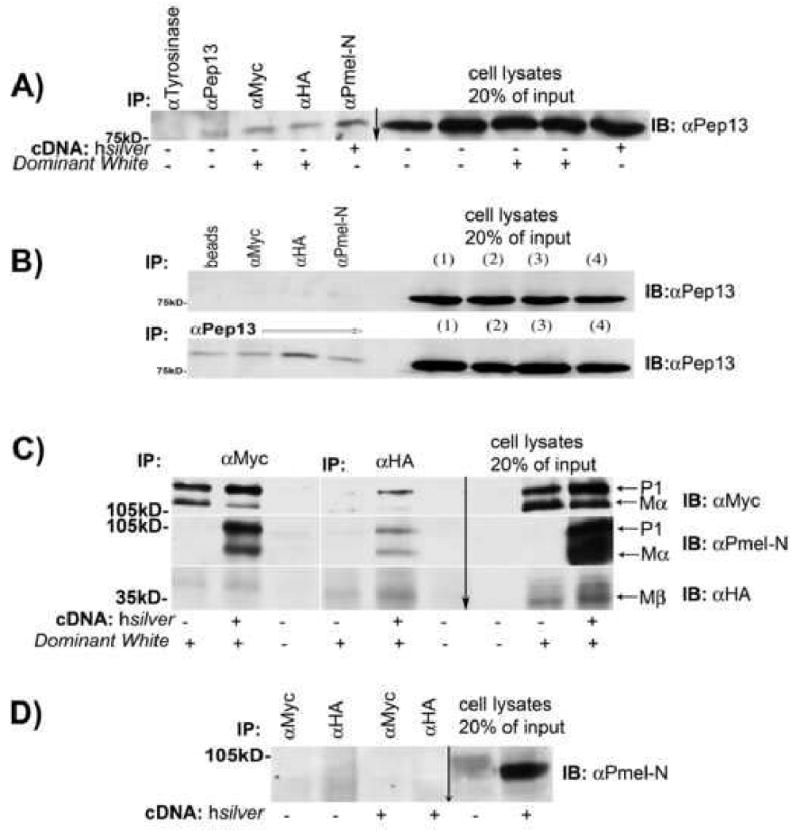

Fig. 4.

Endogenous and exogenously expressed Silver proteins physically interact. (A) Cell lysates of mouse melanocytes transiently expressing hSilver or DWhite were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. Immunoblots were probed with anti-murine Silver (mSilver) antibody Pep13; 20% of the original lysate was loaded as input. (B, upper) In control experiments, antibodies to epitope-tagged DWhite or hSilver do not immunoprecipitate mSilver from untransfected cells. (B, lower) A sequential round of immunoprecipitation with Pep13, shows appropriate capture of mSilver. (C) HSilver and DWhite proteins were expressed in HeLa cells, and antibodies to epitope-tagged DWhite (αMyc and αHA) were used in co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Arrows indicate the respective P1, Mα and Mβ isoforms of Silver captured by the antibodies. (D) Epitope-directed antibodies fail to immunoprecipitate hSilver in the absence of DWhite.

The deduced amino acid sequence of mSilver is shorter than its human homologue by 42 amino acids and newly synthesized, mP1 is ∼85 kDa (Kwon et al., 1995). We observed that N-terminus-directed antibodies to ch- or hSilver captured the 85-kDa form of mSilver. To confirm that full-length, P1-Silver isoforms participated in this association, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were repeated in HeLa cells expressing chicken and/or human Silver. Immunoprecipitation of DWhite-P1 correlated with capture of both hP1 and hMα as interaction partners (Fig. 4C). Neither tag-directed antibody (myc or HA) immunoprecipitated hSilver (Fig. 4D). Consistent with the observations that a common conformation-dependent structure permits interaction of a wide variety of amyloidogenic proteins (Kayed et al., 2003), our co-immunoprecipitation experiments show that human, murine and chicken Silver proteins physically interact. This analysis also demonstrates that full-length silver protein P1 is incorporated into multimers.

Triton insolubility of DWhite is similar to hSilver

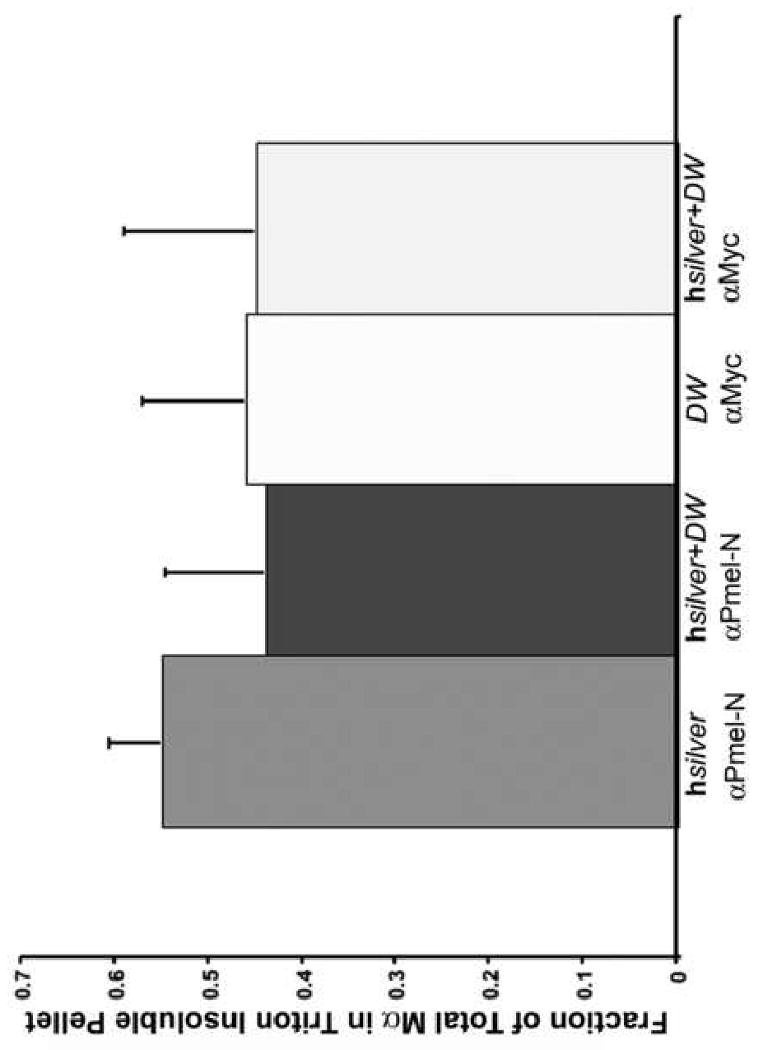

Despite correct endosomal localization and processing to chMα, co-expression of DWhite reduced HMB45-immuoreactive hMα (Fig. 1C, D). Since it is the Mα fragment that has been shown to form insoluble, HMB45-positive aggregates in Triton X-100 (Berson et al., 2003), we wanted to know if loss of HMB45 antigenicity reflected changes in detergent solubility. We therefore examined Triton X-100-insoluble complexes of DWhite alone or when co-expressed with wild-type Silver. Comparison of Mα recovered in the Triton X-100-insoluble pellet as a fraction of starting material and visualized by N-terminus-directed antibodies, revealed that the transmembrane mutation had no effect on overall detergent solubility (Fig. 5). As in previous experiments, coexpression of DWhite and hSilver reduced HMB45 immunoreactivity of Triton X-100-insoluble hMα (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

A fraction of DWhite Mα is Triton X-100 insoluble. Cell homogenates of HeLa cells expressing hSilver and/or DWhite were separated into Triton X-100-soluble and -insoluble fractions followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies as indicated. Averages of Triton-insoluble hSilver Mα recovered as fraction of total are shown (n=16, from eight separate experiments performed in duplicate). Detergent insolubility of Mα (shown) or Mα plus P1 (data not shown) was not significantly altered by DWhite.

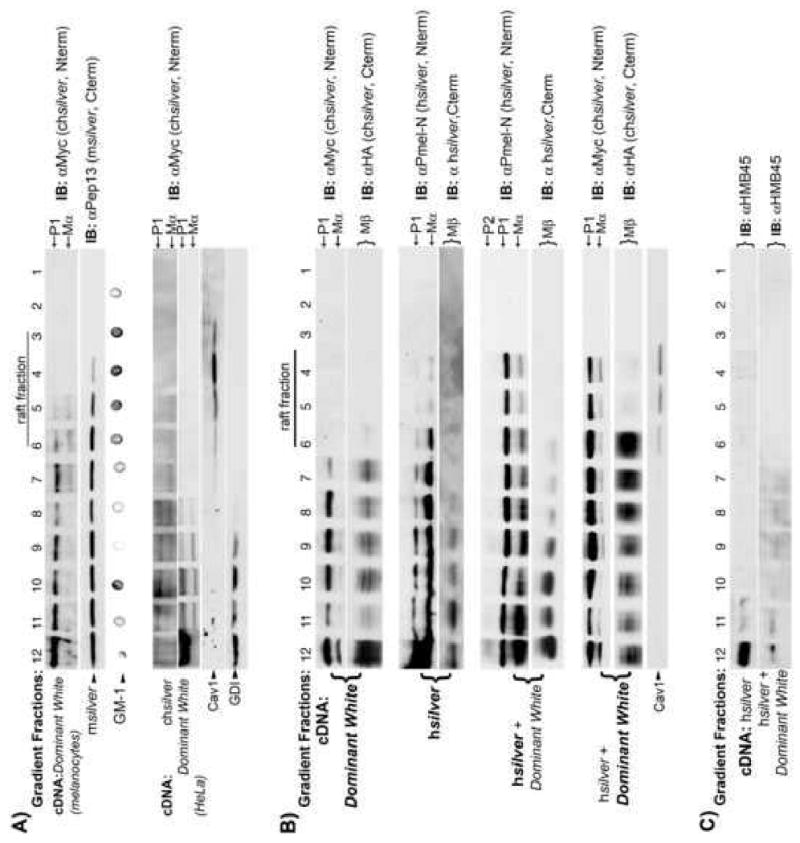

DWhite associates with DRMs in the presence of wild-type Silver protein

Internal membranes of MVBs typically have a high glycosphingolipid and cholesterol content (Mobius et al., 2003) that form DRMs. DRMs may play a role in progression from early to late endosomes (Gruenberg, 2001, 2003; Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004) and early to late stage I melanosomes (Hurbain et al., 2008). Association of proteins with DRMs is commonly determined by their ability to float in cold Triton X-100 and thus, to analyze if the transmembrane domain is important for DRM association, melanocytes as well as non-pigmented HeLa cells expressing hSilver and/or DWhite were lysed in cold Triton X-100 and DRMs were isolated by flotation. The distribution on these gradients of DWhite-P1 and DWhite-Mα in melanocytes expressing DWhite protein resembles that of endogenous mSilver (Fig. 6A, upper). Whereas wild-type chSilver Mα (Fig. 6A, lower) floats with the DRM fractions, none of the DWhite-P1 or Mα floats when expressed in HeLa cells alone (Fig. 6A lower and 6B upper). Co expression of hSilver in HeLa cells relocates DWhite-P1 and Mα to DRMs (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6C, HMB45-positive hSilver is recovered as a pellet at the bottom of raft gradients (Fig. 6C, hSilver). Differences in recoveries of hMα are somewhat variable between experiments and not readily attributable to the presence of DWhite. DWhite does not influence the migration of hSilver in raft gradients (Fig. 6B, compare hSilver and hSilver+ DWhite, detected by anti Pmel-N immunoblot). It is noteworthy that Mβ does not float and that hMβ in particular is restricted to the load fraction (Fig. 6B). Importantly, co-expression of DWhite and hSilver both drastically alters HMB45 immuoreactivity of hMα (Fig. 6C, hSilver + DWhite) and enables DRM associations of mutant chMα.

Fig. 6.

Co-expression of hSilver targets DWhite to DRMs. (A) DWhite protein distribution in the detergent-resistant fraction of raft gradients is cell type specific. Melanocytes expressing DWhite (A, upper) or HeLa cells expressing hSilver, chSilver or DWhite (A-lower, B and C) were extracted in cold 1% Triton X-100 as detailed in Materials and methods and fractionated on a sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected from the top of the gradient (1–12) and analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies. GDI and GM-1 (melanocytes) or caveolin1 (HeLa) were used to delineate the soluble and detergent-resistant fractions, respectively. (A-upper) DWhite Mα is recovered in DRMs in melanocytes. DWhite-P1 also enters the raft fraction in parallel to endogenous mSilver. (A-lower) In contrast, DWhite Mα partitions into the detergent-soluble fraction in HeLa cells; non-mutant chSilver Mα is recovered in DRMs. (B) In a separate experiment, DWhite Mα and Mβ fragments are recovered in detergent-soluble fractions of raft gradients (HeLa). hMα expressed alone or in concert with chSilver, (DWhite shown) partitions into DRMs. Co-expression of hSilver and DWhite shifts DWhite Mα fragment distribution to DRMs. (C) Co-expression of hSilver and DWhite results in reduced recoveries of HMB45-immunoreactive hSilver in pellet fraction 12 concomitant with a broader distribution within the gradient.

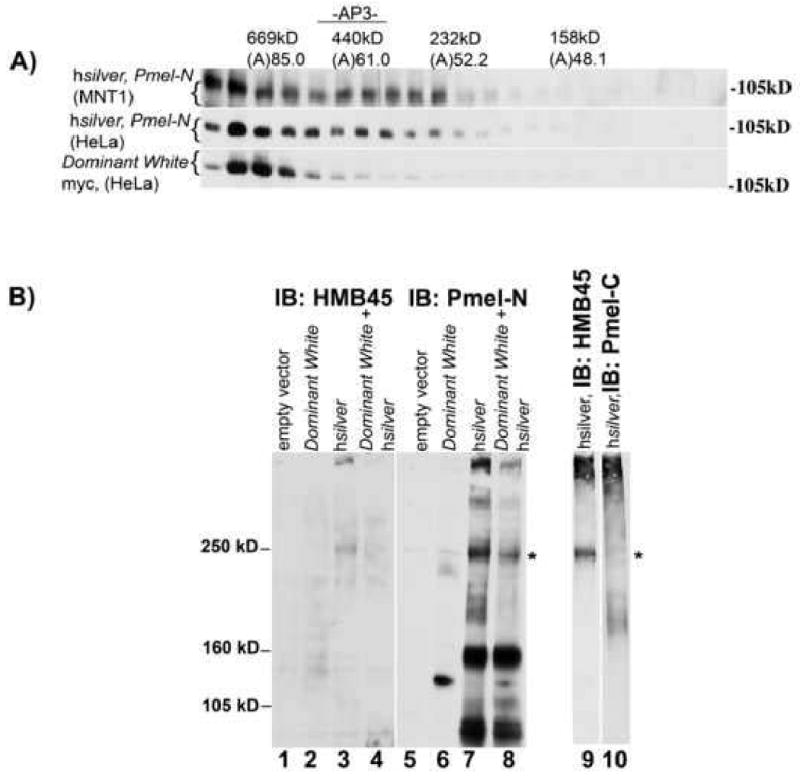

DWhite inhibits formation of HMB45-positive, higher-order disulfide-linked hMα multimers

Membrane microdomains are thought to also participate in structuring amyloid fibrils (Ehehalt et al., 2003; Gellermann et al., 2005; Kakio et al., 2003; Sanghera and Pinheiro, 2002; Schneider et al., 2008) and it has been suggested that on arrival and budding into the lumen of MVBs, the growth of amyloid-like Silver fiber may depend on lipids contributed by intralumenal vesicles (ILVs) (Hurbain et al., 2008). Based on our observations that mutant Silver is excluded from DRMs, alterations in multimer structure was a strong possibility. To test for an effect of the transmembrane domain on the oligomeric state of full-length Silver proteins, cells were solubilized in nonionic detergents and cell lysates were fractionated using non-denaturing Sephacryl S300 size exclusion chromatography. Western blot analysis shows that higher-order assemblies are formed by endogenous hSilver from MNT1 human melanoma and by hSilver or DWhite expressed in HeLa cells (Fig. 7A, fractions 1 to 4). The distribution of wild-type Silver however, also includes particles with a Stoke's radius indicating smaller complexes (Fig. 7A, fractions 5 to 10). These smaller complexes were not observed with DWhite. As hSilver formed smaller complexes in both melanoma and HeLa cells, we can rule out that they involve interactors specific to melanocytes (compare hSilver, MNT1 and hSilver, HeLa, fractions 5 to 10) or DWhite (not shown). Molecular weight determinations, immunoreactivity to both N- and C-terminus-directed antibodies (Pmel-N: hSilver, and Myc: DWhite shown) and lack of immunorecognition by HMB45 (not shown), identify the detergent-soluble Silver as the P1 isoform. These measurements suggest that full-length Silver multimerizes and DWhite-P1 associations tend to form large aggregates.

Fig. 7.

Disulfide bond formation mediates hSilver multimerization. (A) Detergent extracts of cells were fractionated by size exclusion chromatography on FPLC columns. Positions of protein standards and the distribution of endogenous AP3 complex are indicated. Immunoblot analysis is of fractions isolated from MNT1 human melanoma cell lysates with endogenous expression of hSilver or lysates of HeLa cells expressing hSilver or DWhite constructs. By FPLC column chromatography, Silver protein complexes of approximately 600 and 300 kDa are isolated. Based on molecular weight and costaining by N-(shown) and C-terminus directed antibodies, bands represent the P1 form of Silver. (B) HeLa cells expressing the indicated recombinant proteins were lysed in the presence of 10 mM iodoacetamide to protect free thiol groups and lysates were analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Immunoblots were prepared and probed with HMB45 (left panel: lanes 1 to 4, right panel: lane 9), Pmel-N (middle panel: lanes 5 to 8) or Pmel-C (right panel: lane 10) antibodies. Immunoreactivity to αPmel-N reveals bands consistent with monomer and greater-order associations of hSilver (lanes 7 and 8). In the presence of DWhite, levels of disulfide-linked higher-order associations and HMB45-reactive bands of hSilver are reduced (compare lanes 7 and 8; 3 and 4). HMB45 antibody recognizes these higher-order (indicated by *, ∼250 kDa and larger) but not smaller hSilver multimers (lanes 3 and 7). HMB45-positive peptides are not recognized by the COOH terminus-directed antibody, pmel-C (lanes 9 and 10).

Sequence homology modeling of Silver proteins has demonstrated several highly conserved cysteine residues from fish to man (Theos et al., 2005). To determine if disulfide-mediated protein assembly contributes to fibril construction, we expressed hSilver and/or DWhite in non-pigmented cells, lysed cells in SDS-containing buffer and analyzed cell lysates by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Based on immunorecognition by antibodies directed against the N-terminus (Pmel-N, Fig. 7B, lanes 7 and 8) but not the C-terminus (Pmel-C, Fig. 7B, lane 10), the majority of the bands represent Mα and not P1 or P2 forms of hSilver. By 4 % acrylamide SDS-PAGE, we resolved a fast migrating, ∼85-kDa band consistent with an Mα monomer (Pmel-N, Fig. 7B, lanes 7 and 8, bottom of gel) and slower migrating, disulfide-linked multimers consistent with a dimer (∼160 kDa), trimer (∼250 kDa) and higher order associations of hSilver (Pmel-N, Fig. 7B, lane 7). In the presence of DWhite, hSilver formed fewer of the higher-order disulfide-mediated multimers (compare lanes 7 and 8). As indicated by an asterisk, these disulfide-linked Mα complexes that resolve near the 250-kDa MW marker are specifically identified by immunoreactivity to HMB45 (Fig. 7B, lane 9, indicated by asterisk). These results support the importance of correct alignment and distinct disulfide pairing of lumenal domains for the structural organization of mature fibers.

Discussion

The genetic mutation DWhite affects plumage color by triggering the premature death of melanocytes (Hamilton, 1940; Jimbow et al., 1974). Ultrastructurally, melanocytes from feathers of even heterozygous birds harbor melanosomes with abnormal spherical morphology and disorganized fibrils (Brumbaugh, 1971; Brumbaugh and Lee, 1975; Jimbow et al., 1974). To date, how DWhite mutation contributes to cytotoxicity or exerts its dominant-negative effect is not known. To better understand the role of the integral membrane protein Silver in the construction of an organized scaffolding important for cell function, we analyzed the contribution of DWhite to sorting to stage I melanosomes/endosomes, proteolytic maturation of Silver/DWhite proteins and their multimerization. DWhite mutation does not significantly impinge on early steps of melanosome biogenesis: transport along the secretory route to endosomes in non-pigmented cells or stage I melanosomes in melanocytes, generation of DWhite Mα fragments and formation of Triton-insoluble complexes. The DWhite mutation does prevent DRM localization. Somewhat unexpectedly, expression of non-mutant Silver protein restores lipid interaction. Of particular interest in regard to construction of HMB45-positive, mature fibers is our observation that the dominant-negative phenotype of the transmembrane defect is to reduce disulfide-mediated Mα-lumenal domain oligomerization.

How then, do the altered associations of Mα fragments explain the observed absence of stage II melanosomes? Current thinking suggests that for fibril formation, Silver proteins must localize to cholesterol/sphingolipid-rich ILVs or membrane domains destined for ILVs (Theos et al., 2006b). At least two different pathways to sort cargo for delivery to ILVs within MVBs have been described: one requires the function of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) and a second that depends on ceramide (Trajkovic et al., 2008). By deletion analysis, sorting of hSilver into ILVs is insensitive to inhibition of Hrs and ESCRT complexes and does not depend on cytoplasmic and transmembrane determinants (Theos et al., 2006b). When targeting of the hSilver-lumenal domain to ILVs was examined, it was found that only deletions of the N-terminal region (NRT) or the polycystic kidney disease protein-1 like repeat domain (PKD) had a dramatic effect (Theos et al., 2006b). DWhite protein (this report) targets essentially correctly to limiting membranes of rab5-positive MVB compartments but is recruited to DRMs only in the presence of wild-type Silver. The possibility of a direct glycosphingolipid and PKD or NTR domain interaction has been considered (Theos et al., 2006b) and Mα domain expressed alone appears to participate in ILV- and perhaps lipid-dependent growth of premelanosome fibrils. Worthy of note in this regard is the inability of intracellularly generated DWhite Mα to associate with DRMs (this report). Our experiments suggest that a critical role of the Silver transmembrane domain is to influence Mα lipid interaction.

A recent study using electron tomography offers additional clues (Hurbain et al., 2008). Early stage I melanosomes contain ILVs in close apposition to the limiting membrane, and adjacent to ILVs, thin, short hSilver fibrils are observed (Hurbain et al., 2008). Importantly, progression to stage II is mediated by events in late stage I compartments: accumulation of fibril and maturation to organized parallel sheets (Hurbain et al., 2008). Thus, failure to interact with lipid microdomains, a recessive phenotype of the DWhite mutation, may restrict ILV-dependent transition from early to late stage I melanosomes. Non-mutant Silver can restore DWhite-DRM interaction and possibly the targeting to late stage I melanosomes. Questions remain. How does the DWhite mutation contribute to the absence of stage II melanosomes in heterozygotes? Our studies show that the mutation alters intermolecular disulfide bonds within wild-type Mα and this dominant-negative phenotype changes fiber organization and accumulation (as determined by loss of HMB45 reactivity). Although speculative, as summarized in the cartoon shown in Fig. 8, we suggest that the insertion of tryptophan, alanine and proline into the transmembrane domain specifically impacts alignment and packing of mutant Silver or mutant/wild-type Silver multimers and prevents their organization into parallel sheets (Hurbain et al., 2008). Thus, abrogation of specific fibrillar structures essential for stage II progression may block the production of stage II melanosomes.

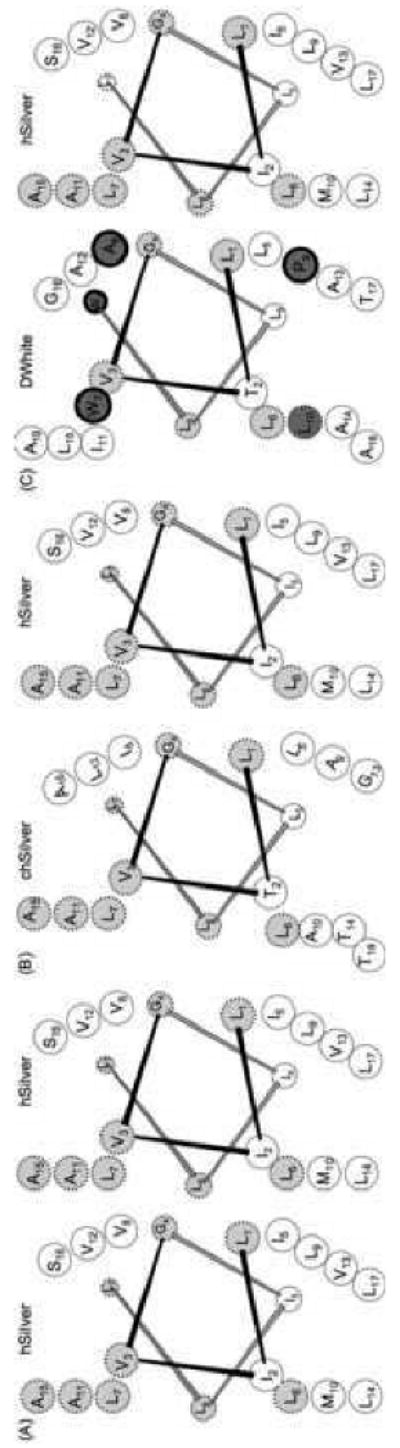

Fig. 8.

Helical wheel projections of hSilver sequence predicted to span the lipid bilayer. The structural model is not intended to suggest distinct alignments for fibril assembly but to illustrate potential consequences introduced by the insertion of WAP. Helical wheel representation of sequences predicted to span the lipid bilayer (JPRED3) and conserved residues (light grey, dashed outline) are shown. The three amino acids introduced by the mutation are highlighted in dark grey and bold outline. Side chains that occupy a, b, c and d positions are indicated for (A) hSilver-hSilver, (B) chSilver-hSilver and (C) DWhite-hSilver pairs. Transmembrane domains are positioned in parallel only to demonstrate that the register of conserved residues V3, L7 A11, A15 from h and chSilver is not preserved in the presence of DWhite. Note also that P9 and W7 occur in positions that may allow local deformation of helix-helix alignment. Position of conserved L7, (L10 in case of DWhite) has been transposed from c to b of the helix surface as a consequence of the mutation.

At what stage along the secretory pathway do multimers form? Remarkably, size exclusion chromatography on FPLC columns and co-immunoprecipitation experiments reveal that the ER-associated, full-length P1 form of Silver protein is incorporated into multimers. Thus, in contrast to the existing models, the initial steps in polymerization may take place as early as in the ER. Nevertheless, the broad range of P1-hSilver observed by FPLC chromatography and the small amounts of non-mutant Silver but no DWhite recovered in subcellular fractions of sucrose gradients are questions that remain open, and more work will be necessary to determine how differences in oligomeric states relate to organelle distribution.

Folding of Silver protein in the ER most likely follows a two-stage process proposed for membrane proteins in general (Popot and Engelman, 1990). Formation of the transmembrane domain (first stage) is influenced by hydrophobic effects of the lipid bilayer (Popot and Engelman, 1990) and limits the possible structures so that most transmembrane segments fold predominantly as α-helices (von Heijne, 1996; White and Wimley, 1999). Although proline is considered a helix-breaker in water-soluble proteins, proline residues are often found in transmembrane helices and their most common effect is to bend the helix (Bywater et al., 2001; Chou and Fasman, 1974; von Heijne, 1991). Therefore, we hypothesize that the proline residue inserted as a consequence of the DWhite mutation introduces a kink and thereby changes the operational length of the transmembrane domain. The altered disposition of the heteromultimer within the membrane may in turn influence the vertical alignment and interactions of the lumenal domains. The mutation is likely to also change transmembrane side-to-side association and these interactions are particularly sensitive to steric clashes (Popot and Engelman, 2000; White and Wimley, 1999). The cartoon showing helical wheel projections of predicted transmembrane sequences (Fig. 8) identifies conserved side chains occupying potential interaction site(s). These diagrams suggest that a bulky tryptophan residue (and perhaps proline) may introduce voids in transmembrane packing that influence oligomerization. Disorganized aggregates of even non-disease-related proteins have been shown to be more cytotoxic than their organized, mature fibrillar structures (Bucciantini et al., 2002). Ultimately, levels of harmful melanin intermediates and/or the pathogenic structural nature of oligomers containing DWhite protein result in premature death of melanocytes and the amelanotic phenotype.

We have focused on the melanosome and how the trafficking, posttranslational processing and multimerization processes transform the cargo membrane protein Silver into structures that affect organelle maturation and cell health. Melanosomes belong to a larger group of lysosome-related organelles that are derived from MVBs (Bonifacino, 2004; Raposo and Marks, 2002, 2007) and it will be of interest to determine if common mechanisms drive organelle biogenesis and influence function in diverse cell types. Moreover, our model for fiber formation highlights the importance of the transmembrane region in organizing lumenal domain interaction and suggests how protein multimerization may be selectively controlled.

Acknowledgments

We thank National Institutes of Health Grant DK56027 (to R. Kuliawat) and Irene Diamond Professorship in Immunology (to L. Santambrogio) for funding. We acknowledge Einstein Analytical Imaging Facility, J. Zhong and S.-R. Kim for technical assistance. We are grateful to Drs. J. Backer, M. Mochii, M. Marks, V. Hearing, P. Scherer and D. Shields, for kindly providing reagents used in our studies. We especially thank M. Marks, C. Riebeling, A. Muesch and P. Arvan for enthusiastic discussion and helpful comments. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berson JF, Harper DC, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Pmel17 initiates premelanosome morphogenesis within multivesicular bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3451–3464. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson JF, Theos AC, Harper DC, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Proprotein convertase cleavage liberates a fibrillogenic fragment of a resident glycoprotein to initiate melanosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:521–533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS. Insights into the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles from the study of the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1038:103–114. doi: 10.1196/annals.1315.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh JA. The ultrastructural effects of the I and S loci upon black-red melanin differentiation in the fowl. Dev Biol. 1971;24:392–412. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(71)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh JA, Lee KW. The gene action and function of two dopa oxidase positive melanocyte mutants of the fowl. Genetics. 1975;81:333–347. doi: 10.1093/genetics/81.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunberg E, Andersson L, Cothran G, Sandberg K, Mikko S, Lindgren G. A missense mutation in PMEL17 is associated with the Silver coat color in the horse. BMC Genet. 2006;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bywater RP, Thomas D, Vriend G. A sequence and structural study of transmembrane helices. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2001;15:533–552. doi: 10.1023/a:1011197908960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty AK, Platt JT, Kim KK, Kwon BS, Bennett DC, Pawelek JM. Polymerization of 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid to melanin by the pmel 17/silver locus protein. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:180–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.t01-1-00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamenti AM, Vella F, Bonetti F, Pea M, Ferrari S, Martignoni G, Benedetti A, Suzuki H. Anti-melanoma monoclonal antibody HMB-45 on enhanced chemiluminescence-western blotting recognizes a 30-35 kDa melanosome-associated sialated glycoprotein. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:291–298. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou PY, Fasman GD. Prediction of protein conformation. Biochemistry. 1974;13:222–45. doi: 10.1021/bi00699a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Wahl JM, Rees CA, Murphy KE. Retrotransposon insertion in SILV is responsible for merle patterning of the domestic dog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1376–1381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506940103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehehalt R, Keller P, Haass C, Thiele C, Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Alory-Jost C, Marks MS, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Functional amyloid formation within mammalian tissue. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Functional amyloid – from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellermann GP, Appel TR, Tannert A, Radestock A, Hortschansky P, Schroeckh V, Leisner C, Lutkepohl T, Shtrasburg S, Rocken C, Pras M, Linke RP, Diekmann S, Fandrich M. Raft lipids as common components of human extracellular amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6297–6302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407035102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J. The endocytic pathway: a mosaic of domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:721–730. doi: 10.1038/35096054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J. Lipids in endocytic membrane transport and sorting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:382–388. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nrm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Gil B, Wiener P, Williams JL. Genetic effects on coat colour in cattle: dilution of eumelanin and phaeomelanin pigments in an F2-backcross Charolais × Holstein population. BMC Genet. 2007;8:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HL. A study of the physiological properties of melanophores with special reference to their role in feather coloration. Anat Rec. 1940;78:525–547. [Google Scholar]

- Harper DC, Theos AC, Herman KE, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Premelanosome amyloid-like fibrils are composed of only Golgi-processed forms of Pmel17 that have been proteolytically processed in endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2307–2322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing VJ. The melanosome: the perfect model for cellular responses to the environment. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;13 8:23–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoashi T, Muller J, Vieira WD, Rouzaud F, Kikuchi K, Tamaki K, Hearing VJ. The repeat domain of the melanosomal matrix protein PMEL17/GP100 is required for the formation of organellar fibers. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21198–21208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurbain I, Geerts WJ, Boudier T, Marco S, Verkleij AJ, Marks MS, Raposo G. Electron tomography of early melanosomes: Implications for melanogenesis and the generation of fibrillar amyloid sheets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19726–19731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803488105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimbow K, Szabo G, Fitzpatrick TB. Ultrastructural investigation of autophagocytosis of melanosomes and programmed death of melanocytes in White Leghorn feathers: a study of morphogenetic events leading to hypomelanosis. Dev Biol. 1974;36:8–23. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakio A, Nishimoto S, Kozutsumi Y, Matsuzaki K. Formation of a membrane-active form of amyloid beta-protein in raft-like model membranes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:514–518. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerje S, Sharma P, Gunnarsson U, Kim H, Bagchi S, Fredriksson R, Schutz K, Jensen P, von Heijne G, Okimoto R, Andersson L. The Dominant white, Dun and Smoky color variants in chicken are associated with insertion/deletion polymorphisms in the PMEL17 gene. Genetics. 2004;168:1507–1518. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A, Shimizu H, Nishikawa T. Expression and ultrastructural localization of HMB-45 antigen. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, Weikard R. An investigation into the genetic background of coat colour dilution in a Charolais × German Holstein F2 resource population. Anim Genet. 2007;38:109–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer MP, Maruyama H, Huelsmann C, Baches S, Weggen S, Koo EH. Formation of Pmel17 amyloid is regulated by juxtamembrane metalloproteinase cleavage, and the resulting C-terminal fragment is a substrate for gamma-secretase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2296–2306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808904200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushimoto T, Basrur V, Valencia J, Matsunaga J, Vieira WD, Ferrans VJ, Muller J, Appella E, Hearing VJ. A model for melanosome biogenesis based on the purification and analysis of early melanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10698–10703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191184798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BS, Halaban R, Ponnazhagan S, Kim K, Chintamaneni C, Bennett D, Pickard RT. Mouse silver mutation is caused by a single base insertion in the putative cytoplasmic domain of Pmel 17. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ZH, Hou L, Moellmann G, Kuklinska E, Antol K, Fraser M, Halaban R, Kwon BS. Characterization and subcellular localization of human Pmel 17/silver, a 110-kDa (pre)melanosomal membrane protein associated with 5,6,-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) converting activity. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:605–610. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MS, Seabra MC. The melanosome: membrane dynamics in black and white. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:738–748. doi: 10.1038/35096009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Esparza M, Jimenez-Cervantes C, Bennett DC, Lozano JA, Solano F, Garcia-Borron JC. The mouse silver locus encodes a single transcript truncated by the silver mutation. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:1168–1171. doi: 10.1007/s003359901184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobius W, van Donselaar E, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Shimada Y, Heijnen HF, Slot JW, Geuze HJ. Recycling compartments and the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies harbor most of the cholesterol found in the endocytic pathway. Traffic. 2003;4:222–231. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochii M, Agata K, Kobayashi H, Yamamoto TS, Eguchi G. Expression of gene coding for a melanosomal matrix protein transcriptionally regulated in the transdifferentiation of chick embryo pigmented epithelial cells. Cell Differ. 1988;24:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(88)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochii M, Agata K, Eguchi G. Complete sequence and expression of a cDNA encoding a chicken 115-kDa melanosomal matrix protein. Pigment Cell Res. 1991;4:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1991.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot JL, Engelman DM. Membrane protein folding and oligomerization: the two-stage model. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4031–4037. doi: 10.1021/bi00469a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot JL, Engelman DM. Helical membrane protein folding, stability, and evolution. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Marks MS. The dark side of lysosome-related organelles: specialization of the endocytic pathway for melanosome biogenesis. Traffic. 2002;3:237–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Marks MS. Melanosomes – dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:786–797. doi: 10.1038/nrm2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Tenza D, Murphy DM, Berson JF, Marks MS. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:809–824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissmann M, Bierwolf J, Brockmann GA. Two SNPs in the SILV gene are associated with silver coat colour in ponies. Anim Genet. 2007;38:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghera N, Pinheiro TJ. Binding of prion protein to lipid membranes and implications for prion conversion. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:1241–1256. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Rajendran L, Honsho M, Gralle M, Donnert G, Wouters F, Hell SW, Simons M. Flotillin-dependent clustering of the amyloid precursor protein regulates its endocytosis and amyloidogenic processing in neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2874–2882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5345-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonthaler HB, Lampert JM, von Lintig J, Schwarz H, Geisler R, Neuhauss SC. A mutation in the silver gene leads to defects in melanosome biogenesis and alterations in the visual system in the zebrafish mutant fading vision. Dev Biol. 2005;284:421–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiji M, Fitzpatrick TB, Simpson RT, Birbeck MS. Chemical composition and terminology of specialized organelles (melanosomes and melanin granules) in mammalian melanocytes. Nature. 1963;197:1082–1084. doi: 10.1038/1971082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theos AC, Truschel ST, Raposo G, Marks MS. The Silver locus product Pmel17/gp100/Silv/ME20: controversial in name and in function. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18:322–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theos AC, Berson JF, Theos SC, Herman KE, Harper DC, Tenza D, Sviderskaya EV, Lamoreux ML, Bennett DC, Raposo G, Marks MS. Dual loss of ER export and endocytic signals with altered melanosome morphology in the silver mutation of Pmel17. Mol Biol Cell. 2006a;17:3598–3612. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theos AC, Truschel ST, Tenza D, Hurbain I, Harper DC, Berson JF, Thomas PC, Raposo G, Marks MS. A lumenal domain-dependent pathway for sorting to intralumenal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes involved in organelle morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006b;10:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli LA, Lah JJ, Levey AI. Rab5-dependent trafficking of the m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor to the plasma membrane, early endosomes, and multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47590–47598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. Proline kinks in transmembrane alpha-helices. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:499–503. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. Principles of membrane protein assembly and structure. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1996;66:113–139. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(97)85627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]