Summary

When leukocytes cross endothelial cells during the inflammatory response, membrane from the recently-described lateral border recycling compartment (LBRC) is selectively targeted around diapedesing leukocytes. This “targeted recycling” is critical for leukocyte transendothelial migration (TEM). Blocking homophilic PECAM interactions between leukocytes and endothelial cells blocks targeted recycling from the LBRC and blocks diapedesis. However, the cellular signaling pathways that trigger targeted recycling are not known. We show that targeted recycling from the LBRC is dependent on Src kinase. The selective Src kinase inhibitor PP2 blocked targeted recycling and blocked diapedesis by over 70%. However, Src kinase inhibition did not affect the structure or normal constitutive recycling of membrane from the LBRC in the absence of leukocytes. PECAM, a Src kinase substrate, traffics between the LBRC and the endothelial surface at the cell border. However, virtually all of PECAM in the cell that was phosphorylated on tyrosine residues was found in the LBRC. These findings demonstrate that Src kinase activity is critical for the targeted recycling of membrane from the LBRC to the site of TEM and that the PECAM in the LBRC is qualitatively different from the PECAM on the surface of endothelial cells.

Keywords: PECAM, LBRC, Leukocyte Transendothelial Migration

Introduction

During the inflammatory response leukocytes migrate out of the bloodstream by squeezing between tightly apposed endothelial cells of postcapillary venules at the site of inflammation. Getting leukocytes to the endothelial cell borders involves the sequential action of a series of adhesion molecules and activation steps that allow the leukocyte to roll on the endothelium, then adhere to it and locomote to the cell junctions[1]. The process of diapedesis in which the leukocyte actually moves across the endothelial monolayer also involves adhesion and signaling events between the leukocyte and endothelial cell [1]. There are a number of endothelial molecules concentrated at the cell border whose blockade by antibody, knockdown, or genetic ablation has been shown to inhibit diapedesis. These include PECAM [2-5], CD99 [6], ICAM-2[7], JAM-A[8, 9], and Polio Virus Receptor [10]. It has become apparent that beyond expressing adhesion molecules to recruit white blood cells to the sites of inflammation, the endothelial cell is actively involved in promoting diapedesis [11, 12]

An extensive reticulum of interconnected membrane is present just within the endothelial borders. This compartment contains approximately 1/3 of the total PECAM in the endothelial cell. Membrane from this compartment, which we call the lateral border recycling compartment (LBRC) is constitutively and rapidly trafficking back and forth evenly along the cell borders [11]. However, during leukocyte transendothelial migration (TEM), membrane from the LBRC is targeted directly around the transmigrating leukocyte [11, 12]. This targeted recycling is microtubule-dependent and mediated by kinesin molecular motors [12], and is required for transmigration. Blocking targeted recycling from the LBRC by blocking leukocyte PECAM-endothelial PECAM homophilic interactions, by disrupting microtubule structure or function, or by inhibiting kinesin motors prevents TEM [11, 12]. PECAM-PECAM interactions are required for initiating targeted recycling in most cases, but even in instances of PECAM-independent transmigration, targeted recycling from the LBRC is still required for TEM [12]. Therefore, targeted recycling from the LBRC to surround the leukocyte is a critical independent event in the transmigration process, but the signals required for this membrane trafficking are not known.

In this report we show that diapedesis per se is dependent on Src kinase activity and that blocking endothelial Src kinases inhibits targeted recycling of LBRC membrane around transmigrating monocytes. Furthermore, we demonstrate that virtually all of the phosphorylated PECAM in the endothelial cell is restricted to the LBRC. These data demonstrate that Src kinase is required for the targeted redistribution of membrane from the LBRC to the site of TEM and that the PECAM in the LBRC is qualitatively different from the PECAM on the surface of endothelial cells.

Results

PP2 Blocks Monocyte Diapedesis Across HUVEC

Previous studies have shown that leukocyte migration across endothelial cells is inhibited by PP2, a Src family kinase-specific inhibitor [13]. Src-catalzyed phosphorylation of cortactin was shown to be important for ICAM-1 clustering and actin remodeling required for neutrophil migration across endothelial cells[13]. However, Src kinases might be involved in multiple steps of the transmigration pathway. We focused on the process of diapedesis using an assay system that can distinguish the steps of adhesion, locomotion, and diapedesis [14, 15]. Targeted recycling from the LBRC appears to be downstream of ICAM-1 interactions and independent of the actin cytoskeleton [12].

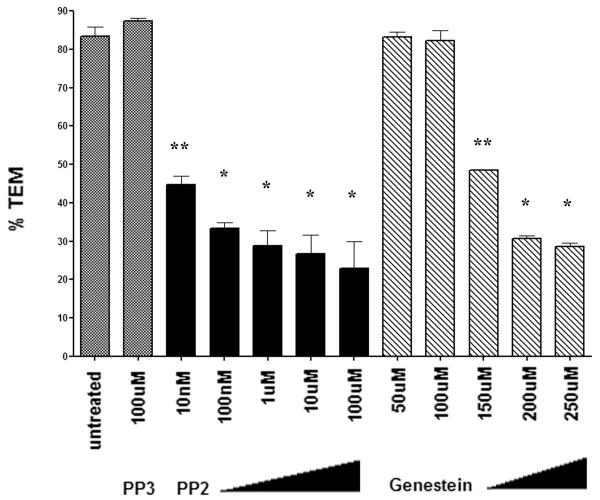

HUVEC were pretreated with PP2 or Genistein, a broad-spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor, then washed extensively to prevent a carryover effect on leukocytes. In control experiments, eluate from pre-treated HUVEC did not have an effect on leukocyte TEM across untreated monolayers and PP2 treatment did not have an effect on monocyte adhesion to HUVEC monolayers. (data not shown). Transmigration was inhibited in a dose dependent fashion by PP2 (Fig 1). TEM was also inhibited at high concentrations of Genistein (greater than 150μM). Transmigration was unaffected by treating the endothelial cells with PP3, an inactive PP2 analog. Our results were in agreement with other studies and showed that Src kinase is required for monocyte diapedesis.

Figure 1. Transmigration requires src kinase activity.

TEM was inhibited by PP2 in a dose dependent manner. Genestein also inhibited TEM at concentrations greater than 100 uM. The data are shown as mean transmigration ± SEM, of 3 fields counted from 2 replicates per condition from three separate experiments. PP2 treatment differed significantly from the nonblocking PP3 condition. Higher concentrations of Genistein blocked transmigration significantly as compared to PP3 (** p<0.005, * p < 0.001, based on one-way ANOVA and Bonferonni correction to compare treated conditions to PP3 control).

Targeted Recycling of Membrane from the LBRC is Dependent on Src Kinase

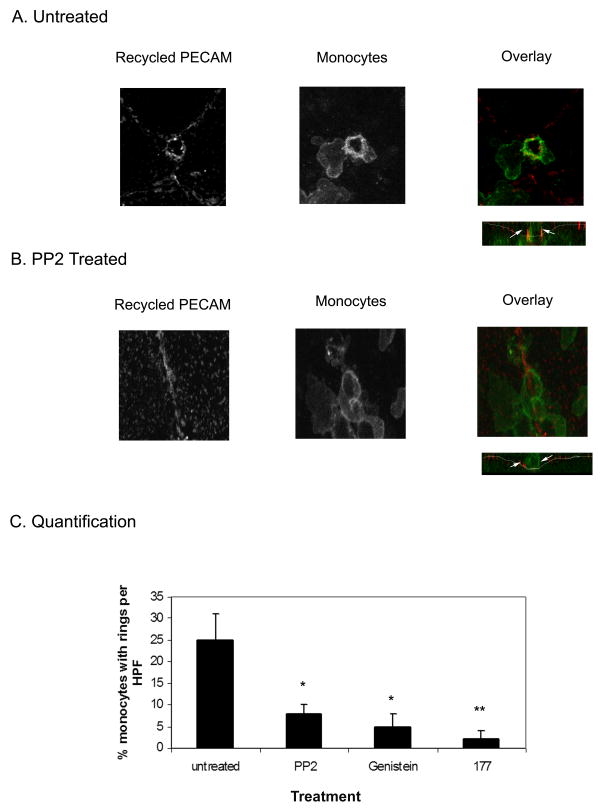

We next examined whether Src kinase is involved in the targeted recycling of membrane from the LBRC that is required for TEM. We used an assay that selectively labels recycling membrane from the LBRC during TEM. [11]. This assay uses Fab fragments of a non-blocking anti-PECAM antibody to mark the location of recycled LBRC membrane. Confocal microscopy was used to analyze areas of the monolayer where monocytes had engaged the EC junctions and were actively crossing the endothelium. Monolayers were treated with PP2 under the same conditions as described for the quantitative experiment shown in Fig 1. The control untreated HUVEC monolayers show a ring of recycled PECAM around actively transmigrating monocytes (Fig. 2a) as previously described. A ring of recycled PECAM as a marker for recycled LRBC membrane can be seen at the endothelial cell junction that exactly corresponds to the endothelial membrane surrounding a monocyte crossing the EC monolayer (see overlay). The orthogonal view shows clearly that this monocyte is in the act of crossing the junction. In contrast, there is no ring of recycled PECAM around monocytes attached to HUVEC monolayers treated with PP2 (Fig 2b). The orthogonal view shows that the monocyte is at the junction but is blocked on the apical surface of the endothelial cells and is unable to cross through. Approximately 90% of all monocytes were unable to transmigrate in the PP2 treated monolayers.

Figure 2. Targeted recycling of PECAM from the LBRC is Src kinase dependent.

The recycling PECAM assay was performed in the presence of transmigrating monocytes. Overlay showing a monocyte interacting with the EC junction, recycled PECAM (left panel) is shown in red, monocytes (right panel) are shown in green. Orthogonal section through the field is shown below the overlay, to demonstrate the extent of diapedesis. (A) In untreated HUVEC monolayers, PECAM recycling from the LBRC is enriched around the transmigrating monocyte (left). The monocyte shown is actively crossing the HUVEC monolayer (arrow). (B) In PP2 treated monolayers, there is no PECAM enrichment around the monocyte (left), and the orthogonal section shows that the monocyte is blocked on the apical side of the endothelial junction (arrow). Images shown are representative of hundreds of leukocytes observed in 4 independent experiments. (C) Quantitative analysis of monocytes interacting with the endothelial cell junctions. The total number of monocytes that had rings of recycling PECAM around them was counted per field (Materials and Methods). Virtually all of the transmigrating monocytes showed rings of enriched PECAM. In comparison there is an inhibition of targeted recycling of PECAM in the PP2 and Genistein treated HUVEC. Endothelial cells treated with anti-PECAM ab (177) are shown as a control. The data are shown as the average % monocytes with associated PECAM enrichment rings per HPF ± SEM of 30 fields analyzed from each of 2 replicates per condition across 4 separate experiments. PP2 and Genistein treatment (*) differed significantly from the untreated control (p < 0.005) and 177 (**) also blocked ring formation significantly (p < 0.001) as determined by comparing PP2, Genistein and 177 to untreated control via one-way ANOVA and bonferonni correction).

We examined many fields in order to quantify these results. The number of rings of recycled LBRC membrane around monocytes were counted per high powered field and taken as a percentage of the total number of monocytes actively engaging an EC junction per high powered field (Fig 2c). In order to catch leukocytes in the process of transmigration, these co-cultures were analyzed at an early time point (10 minutes after adding the monocytes), which is well before most of them have transmigrated. In any given field in the untreated monolayers, approximately 30% of the monocytes are actively crossing the monolayer. Virtually all of these transmigrating leukocytes showed rings of PECAM enrichment around them. In contrast there were very few rings of LBRC recycling seen around monocytes engaging PP2 treated monolayers. These data show that PP2 treatment abolishes targeted recycling of membrane from the LBRC, quantitatively and qualitatively similar to the inhibition of targeted recycling seen when monocyte TEM is blocked by treatment with an anti-PECAM antibody.

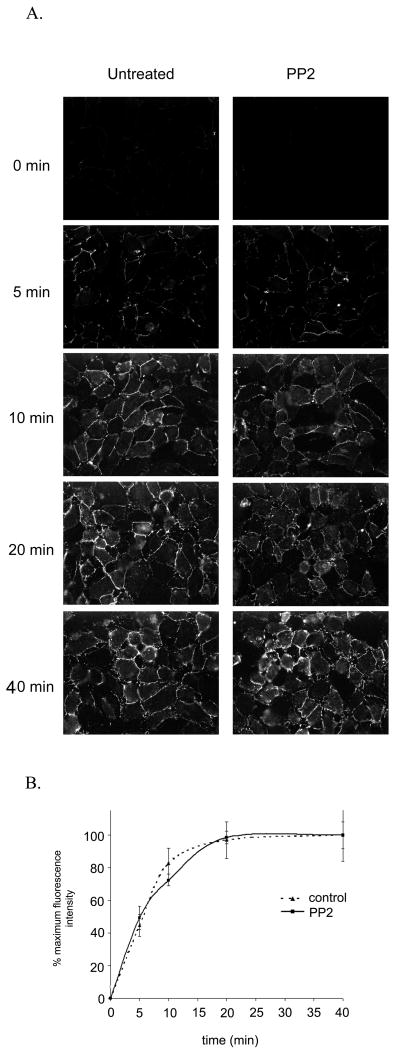

PP2 Treatment Does Not Affect PECAM Constitutive Recycling from LBRC

In resting HUVEC, in the absence of transmigrating leukocytes, PECAM (along with other components of the LBRC) recycles constitutively between the LBRC and the EC junctions. The effect of PP2 on targeted recycling could be indirect, due to an effect on the size, location, or constitutive trafficking of the LBRC. Therefore, we next tested whether PP2 also has an effect on LBRC location or constitutive recycling. In an assay where recycling PECAM (serving as a marker for LBRC membrane) becomes fluorescent as it reaches the cell surface, both the control HUVEC and HUVEC treated with PP2 showed qualitatively and quantitatively similar increased fluorescence associated with the junctions over time. (Fig 3a) These images were then quantified to determine the actual kinetics of recycling (Fig 3b). The PP2 treated cells showed no significant difference in constitutive LBRC recycling, as fluorescence increased in the junctions steadily over time and then saturated at around 20 min. Therefore it seems that Src kinase is required for targeted recycling but not for formation or maintenance of the LBRC.

Figure 3. PP2 has no effect on constitutive recycling of PECAM from the LBRC.

(A) Sample images of HUVEC monolayers from a recycling assay where PECAM becomes fluorescent as it reaches the cell surface (Materials and Methods). HUVEC were untreated (left) or treated with 100μM PP2 for 2hrs (right). Recycled PECAM shown at the timepoints indicated was quantified to determine the kinetics of recycled PECAM. Untreated cells (solid line, squares) and PP2 treated cells (dotted line, circles) show no differences in constitutive recycling of PECAM from the LBRC (p < 0.005 as determined by nonlinear curve fit and F test). Images shown are representative of 20 fields analyzed per condition for each of 3 independent experiments. The data are an average of normalized curves from 3 separate experiments (where each experiment consisted of 20 fields analyzed for 2 replicates per condition.

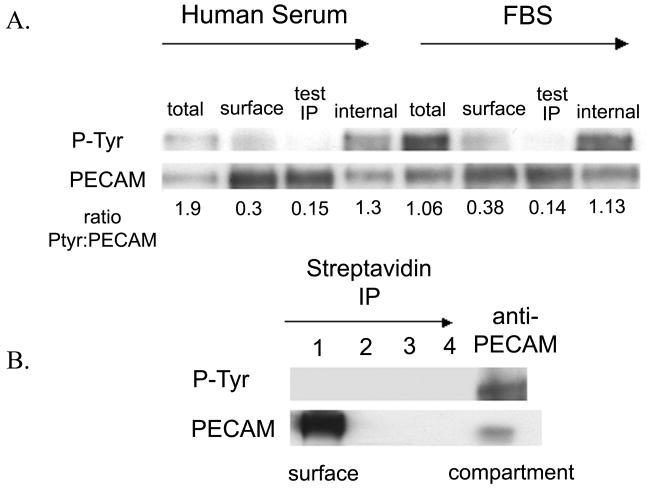

Phosphorylated PECAM is Enriched in the LBRC

There could be many substrates for Src kinase that would be required for targeted recycling. However, an obvious candidate is PECAM, which has two tyrosine residues in ITIM domains that are known to be Src substrates. PECAM is required for TEM in most inflammatory conditions and ∼1/3 of the total PECAM in HUVEC localizes to the LBRC. Therefore, we next examined the distribution of phosphorylated PECAM in endothelial cells. We developed an immunoprecipitation assay in which we could selectively separate PECAM on the surface of HUVEC from that in the LBRC (see Methods). The assay was performed on resting HUVEC (grown in M199) and on cells that were cultured in fetal bovine serum in order to enhance the basal level of tyrosine phosphorylation. Tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM is selectively enriched in the LBRC compared to the PECAM on the surface (Fig 4a). We repeated the assay with a more stringent purification technique using biotin/streptavidin, and again the majority of the tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM localized to the LBRC (Fig 4b), showing that the PECAM in the LBRC is qualitatively different from the PECAM on the endothelial cell surface. Phosphorylated PECAM in HUVEC is almost entirely restricted to the LBRC.

Figure 4. Tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM is selectively enriched in the LBRC.

(A) HUVEC were cultured in standard HS media (left half of blot) or media containing FBS (right half of blot) in order to enhance baseline PECAM phosphorylation levels. The PECAM on the surface and in the compartment was immunoprecipitated (Materials and Methods). Samples of the total lysate (total), surface fraction (surface), and LBRC fraction (internal) were analyzed by western blots using anti-PECAM and anti-phosphotyrosine ab (P-Tyr). A sample from the final round of surface PECAM immunoprecipitation is shown (test IP) to ensure that all the surface tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM had been depleted. The ratio of tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM to total PECAM is shown each sample. In both HS and FBS cultured cells, the LBRC fraction had a greater amount of tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM. (B) The assay was repeated on HS cultured HUVEC and the surface PECAM was exhaustively immunoprecipitated (Materials and Methods) using a more stringent method (lanes 1-4). By the fourth round of immunoprecipitation, all of the surface PECAM has been depleted from the lysate (lane 4). The PECAM in the LBRC is preferentially tyrosine phosphorylated (final lane). Blots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

Src family kinases are known to be involved in leukocyte TEM, however the role of tyrosine phosphorylation in regulating the endothelial junctions during leukocyte TEM remains unclear. In this report we show that Src kinase is involved in the targeted recycling of EC membrane from the LBRC around transmigrating leukocytes. This is a distinct membrane trafficking event that is required for monocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte transmigration [12]. We also found that PECAM phosphorylated on tyrosine residues is selectively located in the LBRC, suggesting a possible mechanism for how tyrosine phosphorylation regulates leukocyte migration through the vascular endothelium.

Src kinase inhibitors inhibit leukocyte TEM. When we performed a time course of PP2 and Genistein treatment, there was no difference in the number of leukocytes that transmigrated, showing that Src inhibitors cause a block rather than a delay in TEM. Our laboratory recently reported that targeted recycling of membrane from the LBRC to the junction at the site of leukocyte diapedesis is critical for leukocyte TEM[11]. We found that PP2 treatment of endothelial cells blocked targeted recycling from the LBRC. However, in the absence of leukocytes, constitutive recycling of membrane from the LBRC was unaffected by treating with PP2. In resting HUVEC, membrane recycles from the junction to the LBRC and back in a continuous process. Our data show that although Src kinase is not involved in the formation or maintenance of the compartment, it is required specifically for targeted recycling during leukocyte TEM.

In order to further investigate the role of Src kinase in targeted recycling during TEM, we focused our attention on PECAM. PECAM is a molecule that is found in the LBRC and is critical to TEM, especially in the assay conditions used for this study. Our laboratory has shown previously that ∼1/3 of the total PECAM in HUVEC localizes to the LBRC. In addition, it has been widely shown that Src kinase phosphorylates PECAM on its tyrosine residues in response to various stimuli. Therefore we directly compared the PECAM in the compartment to the PECAM on the surface of endothelial cells. Our results show that PECAM phosphorylated on tyrosine residues appears to be restricted to the LBRC. This enrichment was observed in HUVEC using two different detection methods and culture conditions. This is a novel finding in that it is the first evidence to date that phosphorylated PECAM is restricted to a subcellular compartment, and that the PECAM in the LBRC differs qualitatively from the rest of the cellular PECAM.

We tried to examine the status of PECAM phosphorylation during TEM. Constitutive PECAM phosphorylation is low in resting endothelial cells. PECAM phosphorylation increases when endothelial cells initially adhere to collagen or fibronectin, [16, 17] but the level of tyrosine phosphorylation drops in resting or confluent monolayers [17]. Similar to previous publications, we found very low levels of phosphotyrosine on PECAM whether they were grown under resting or cytokine activated conditions, and these levels did not change significantly during monocyte transmigration (data not shown.). The sensitivity of our method may have limited our ability to detect a significant change in the phosphorylation of PECAM during TEM. The amount of PECAM on the endothelial cell that interacts with a monocyte during TEM is only about 5-10% of the total PECAM on the endothelial cell, which makes it difficult to detect changes in this pool against the background. It is also possible that since TEM is a rapid process, the endothelial cell PECAM may undergo phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events upon contact with monocytes on the order of seconds that would not be detected when we lysed the cells after transmigration.

We were also unable to detect a reduction in PECAM phosphorylation in PP2 or Genistein treated endothelial cells (data not shown). This could be due to insufficient turnover of phosphorylated PECAM during the PP2 treatment. Another possible explanation is that Fer kinase also phosphorylates PECAM [18] and is not susceptible to PP2. As a positive control, concentrations of PP2 that inhibited leukocyte TEM were able to inhibit VEGF stimulated phosphorylation of Grb10 and TNF stimulated induction of ICAM-1 in HUVEC (data not shown) in accordance with previously published studies[19, 20] proving that this concentration of PP2 does have a measurable effect on Src kinase activity in our endothelial cells. Although previous studies have shown that some kinase inhibitors can inhibit activation induced PECAM phosphorylation on tyrosine [21] and serine residues [22, 23] none have demonstrated a change in baseline PECAM tyrosine phosphorylation in response to PP2 treatment in the absence of activation, or during leukocyte TEM. Therefore, it is not surprising that there was no detectable decrease in PECAM phosphorylation following PP2 treatment of endothelial cells.

Previous studies have shown that other molecules associated with the endothelial junction and phosphorylated by Src kinases such as cortactin[13] are involved in leukocyte TEM. It was recently reported that ICAM-1 mediated phosphorylation of VE-Cadherin is also Src kinase dependent [24] and required for neutrophil TEM. However, just as there are multiple adhesion and activation steps required for the rolling, adhesion, and migration of leukocytes on endothelial cells, there are clearly multiple molecular events associated with TEM. It is possible that several of these steps require Src kinase activity, including targeted recycling. It is interesting to note that PP2 treatment blocks 70-75% of monocyte TEM over the course of an hour, and that during the PECAM recycling assay, a few monocytes are observed with rings of LBRC enrichment around them on the PP2 treated monolayers. This TEM and enrichment could represent an inability to completely shut down Src with the concentrations of PP2 that were used to minimize toxicity to the endothelial cells. It may also represent LBRC recycling under conditions that use a Src-kinase independent mechanism, such as Fer kinase. Since there are no specific Fer kinase inhibitors we were unable to test this.

Our data do not directly demonstrate a role for Src kinase in phosphorylating PECAM. However, although the exact mechanism of how Src kinase regulates targeted recycling remains unclear, our results suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation of PECAM may play a role in targeted recycling. We hypothesize that one of the functions of Src kinase in TEM may be to phosphorylate PECAM so that it can participate in targeted recycling. At this time it is also not known whether PECAM must be phosphorylated to enter the compartment, and how it loses its phosphorylation upon reaching the surface of the endothelial cell. It may be that PECAM becomes dephosphorylated as it leaves the compartment. Although PECAM is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues 663 and 686[25] in response to various stimuli, the role of these tyrosines in leukocyte TEM is unknown. Since PECAM in the LBRC is critical for TEM under most circumstances [12], our study suggests that PECAM tyrosine residues are critical for leukocyte TEM and are involved in targeted recycling of PECAM from the LBRC. SHP-2 is recruited to the cytoplasmic tail of PECAM following phosphorylation of these tyrosine residues in endothelial cells [26, 27] and T cells [28, 29]. These phosphatases may be the link to downstream signaling mechanisms triggering targeted recycling. We plan to test this hypothesis and examine the role of phosphorylation of PECAM's cytoplasmic tyrosines in leukocyte TEM in future work.

We have shown that leukocyte TEM is dependent on Src kinases and that blocking Src kinases blocks targeted recycling of LBRC membrane around transmigrating monocytes. We have also demonstrated that the PECAM in the LBRC is qualitatively different from the PECAM on the surface of endothelial cells. These data provide new insight into the involvement of Src kinases in leukocyte diapedesis, and bring us one step closer to fully understanding the role of the LBRC in endothelial cells during leukocyte TEM.

Materials and Methods

HUVEC Isolation and Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated by previously described methods [30] and cultured on fibronectin-coated tissue culture dishes in medium 199 (M199; Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated normal human serum (from healthy volunteer donors) and penicillin and streptomycin (Mediatech). The cells are cultured under these conditions, as in the absence of exogenous growth factors the ECs grow slowly as they do in vivo on the blood vessel wall and exhibit contact inhibition. HUVEC at passage 2 were cultured on hydrated collagen type I (Vitrogen from Cohesiontech) gels set in 96-well plates [30]. The cells were grown to confluence on the hydrated collagen and cultures that were 2-3 days post confluence were used for all transmigration assays.

Leukocyte Isolation From Peripheral Blood and Transmigration Assay

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from blood through Ficoll gradient separation. The transmigration assay was performed as previously described[31]. The cells were resuspended to a final concentration of 2 × 106 per ml in M199 plus 0.2% Human Serum Albumin (HSA) and added to confluent HUVEC monolayers grown on collagen gels. In some experiments Abs at a concentration of 20 μg/ml were incubated with the PBMC on ice for 20 min before TEM and allowed to remain for the duration of the assay. The PBMC were allowed to transmigrate for 1 hr at 37 ° C in a CO2 incubator. Under these conditions when HUVEC are not cytokine-activated monocytes selectively bind and transmigrate whereas lymphocytes do not[31]. Nonadherent PBMC were removed using several washes with PBS, and the remaining adherent and transmigrated cells were fixed along with the endothelial monolayer by incubation overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The gels were differentially stained with Wright-Giemsa and then visualized on a Zeiss Ultraphot microscope using Nomarski optics. Total adhesion was calculated as the total number of cells, both adherent and transmigrated, per high-powered field (HPF). Transmigration data are expressed as the mean percentage of the total cells that transmigrated below the endothelial layer (%TEM).

PP2 and Genistein Treatment of Endothelial Cells

In some experiments the endothelial cells were treated with the protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor Genistein (Calbiochem), Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (Calbiochem), or PP3 (Calbiochem), and inactive PP2 analog. The compounds were added to HUVEC in M199 media at the indicated concentrations, and then incubated for 2 hours at 37 ° C in a CO2 incubator. Following the treatment, the cells were extensively washed in 1× PBS to prevent a carryover effect on leukocytes that were subsequently added to the cultures. Leukocytes were treated with eluate from the treated HUVEC and tested in a TEM assay across untreated HUVEC as a control experiment.

Membrane Recycling Experiments

An assay in which PECAM that recycles from the LBRC back to the junction becomes selectively fluorescently labeled was developed previously by our laboratory.[11, 12] HUVEC monolayers were incubated for 1 hr at 37 ° C with Fab fragments of P1.1, a monoclonal antibody against domain 5 of PECAM (kind gift from Peter Newman). This antibody labels PECAM but does not inhibit any known PECAM function. This allowed the antibody to label PECAM both on the surface of the endothelial cells and in the LBRC. The monolayers were chilled on ice, and the unbound antibody was washed away. Unconjugated goat anti-mouse F(ab')2 (F(ab')2 fragment specific, Jackson Immunoresearch) was added to the monolayers at saturating concentrations for 1 hr at 4 ° C. The secondary antibody bound all of the P1.1 Fab on the surface of the endothelial cells but not the antibody in LBRC. It has been previously established that the LBRC is inaccessible to small proteins at 4 ° C[11]. After this treatment, unbound antibody was washed away, and the same goat anti-mouse secondary antibody labeled with Alexa-546 was added to the cultures in the cold for 1 hr to allow ample time to penetrate along the endothelial cell borders. In PP2 treated conditions, the cells were treated with 100 μM PP2 for 1 hr prior to antibody incubations, and the drug was present in the 1 hr incubation with P1.1 fab (2 hrs total treatment). Monolayers were then rapidly warmed to 37 ° C for various times to allow membrane recycling to occur before rapid chilling, washing and fixation in 2% PFA. With this method the fluorophore labeled secondary antibody can only bind to Fab fragments that are recycled to the junction from the LBRC. Digitized images were captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M widefield microscope that was equipped with a Princeton Instruments cooled CCD (charged coupled device) camera driven by Image-1/Metamorph Imaging Software (Metamorph Imaging Systems). Metamorph Imaging System Software (Universal Imaging Systems) was used to analyze images.

Targeted Recycling During TEM

A technique to detect PECAM recycling during leukocyte TEM was previously developed in our laboratory[11]. It is important to note that in this assay, a non-blocking anti-PECAM antibody is used to localize PECAM in the LBRC and serves as a surrogate marker for movement of the LBRC membrane. A variation of the procedure for visualizing recycled PECAM was repeated now in the presence of transmigrating monocytes. Monolayers were incubated with P1.1. Fab for 1 hr at 37 °C. As before, some cultures were treated with 100μM PP2 for 1 hr at 37 °C, then subsequently incubated with P1.1. Fab plus PP2 (2 hrs total incubation with drug). The monolayers were chilled on ice, and the unbound antibody was washed away. Unconjugated goat anti-mouse F(ab')2 (F(ab')2 fragment specific, Jackson Immunoresearch) was added to the monolayers at saturating concentrations for 1 hr at 4 ° C. Freshly isolated human PBMC were added to the cultures along with goat anti-mouse F(ab')2 conjugated to Alexa-546. The cells and antibody were added on ice, to allow the monocytes to settle onto the endothelial cell monolayer for 20 min in the cold. The cultures were then quickly warmed to 37 ° C to allow a rapid and synchronous wave of TEM. After 5-10 min, transmigration was stopped by washing and fixation of the monolayers in 2% PFA. As a positive control to inhibit TEM and targeted recycling, in some conditions PBMC were incubated with 20 μg/ml of 177 (a rabbit polyclonal anti-PECAM antibody) on ice for 20 min prior to addition to the endothelial cultures. Monocytes were identified by staining with OKM-1 (anti-CD11b) ab conjugated to Alexa-488 (ATCC). The degree of TEM was analyzed by our usual counting methods. The degree of membrane recycling was visualized by the Alexa-546 conjugated antibody that could only stain the P1.1 Fab on the newly recycled PECAM. The samples were examined using a Zeiss LSM confocal microscope. The confocal images were then analyzed using Metamorph software[11].

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

HUVEC were put on ice, washed twice with cold 1 × PBS then lysed with ice cold RIPA lysis buffer (0.4% NP-40, 100 mM NaCl, 10mM NaPhosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1mM orthovanadate, protease inhibitor cocktail (used at 1:500 dilution, Sigma Cat # 8340). Lysates were cleared of nuclear material by centrifuging at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes twice. The supernatants were pre-cleared with protein-A sepharose beads. 20 μg of purified IgG was then added to each sample and the tubes were rocked at 4 ° C for 4 hours. The immune complexes were precipitated by adding protein-A sepharose to each tube and rocking for 1 hr at 4 ° C. In some experiments IgG directly conjugated to sepharose beads was used for immunoprecipitation (in this case pre-clearing was performed using glycine conjugated sepharose beads). The beads were washed with SA buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 0.0125 M KH2PO4, 0.02% NaN3 pH 7.4), and Detergent buffer (0.1%SDS, 0.05% NP-40, 0.3M NaCl, 0.01 M Tris pH 8.6). Each sample was then boiled for 5 minutes in SDS sample buffer (2% SDS, 0.01% Bromophenol blue, 12% sucrose, in 50 mM carbonate buffer pH 8.2, with 5% β-mercaptoethanol). The samples were run on a 4-12% gradient Tris-Glycine SDS PAGE (Invitrogen) and transferred to a polyvinyldifluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked in 5% BSA and then incubated overnight at 4 ° C with mAbs diluted into 2% BSA. Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG or swine-anti rabbit IgG and proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). In some cases membranes were stripped (Stripping Buffer, Pierce Endogen) blocked overnight in 5% BSA and then re-probed. The following antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation and blotting: 177 (anti-PECAM polyclonal), hec 7 (anti-PECAM monoclonal), both raised in our lab, and 4G10 (mouse mAb anti-phosphotyrosine, Upstate Signaling Solutions).

Isolation of PECAM from Surface and LBRC

HUVEC were incubated with hec 7 on ice to selectively label surface PECAM. The cells were then lysed in RIPA buffer and the lysates were exhaustively immunoprecipitated through several rounds of incubation with protein-A sepharose to bring down all of the surface PECAM. The supernatant was then incubated with fresh hec 7 and immunoprecipitated with protein-A sepharose to bind the remaining PECAM (fraction from the LBRC).

In a more stringent method, all HUVEC cell surface proteins were first biotinylated at 4 ° C. HUVEC were washed in ice-cold Krebs Ringers Bicarbonate Buffer (Sigma) then incubated with 2mM Biotin solution (EZ Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotin, Pierce) for 30 min on ice. The reaction was quenched using 100mM Glycine, and the cells were washed several times in Krebs Ringers buffer. The cultures were then lysed in RIPA buffer. The lysates were exhaustively immunoprecipitated with Streptavidin-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) to deplete all surface proteins from the lysates. The samples were then incubated with hec 7 mAb and protein-A sepharose to immunoprecipitate the remaining PECAM in the lysates (fraction from LBRC).

Samples of the surface and LBRC PECAM fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE. Western blots were performed using hec 7 and 4G10 to visualize tyrosine phosphorylated PECAM.

Statistics

Statistical significance for data from the transmigration and targeted recycling assays was determined by one-way ANOVA' Tukey-Kramer and/or Student's t test where appropriate, using PRISM software (GraphPad)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (HL046489 and HL064774) (W.A.M.) and pre-doctoral and post-doctoral fellowship (T32 AIO7621) (B.D.). We thank Dr. Peter Newman for P1.1 ascites, Ron Liebman for excellent technical assistance, and Drs. M. Resh, Claas Ruffer and Zahra Mamdouh for discussions and comments.

Abbreviations

- TEM

Transendothelial Migration

- LBRC

Lateral Border Recycling Compartment

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: B.D. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results to make the figures and wrote the paper. W.A.M. also designed experiments, provided guidance and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Muller WA. Leukocyte-endothelial-cell interactions in leukocyte transmigration and the inflammatory response. Trends in Immunology. 2003;24:326–333. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178:449–460. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao F, Huynh HK, Eiroa A, Greene T, Polizzi E, Muller WA. Migration of monocytes across endothelium and passage through extracellular matrix involve separate molecular domains of PECAM-1. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1337–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao F, Ali J, Greene T, Muller WA. Soluble domain 1 of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) is sufficient to block transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1349–1357. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao F, Schenkel AR, Muller WA. Transgenic mice expressing different levels of soluble platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-IgG display distinct inflammatory phenotypes. J Immunol. 1999;163:5640–5648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenkel AR, Mamdouh Z, Chen X, Liebman RM, Muller WA. CD99 plays a major role in the migration of monocytes through endothelial junctions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:143–150. doi: 10.1038/ni749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang MT, Larbi KY, Scheiermann C, Woodfin A, Gerwin N, Haskard DO, Nourshargh S. ICAM-2 mediates neutrophil transmigration in vivo: evidence for stimulus specificity and a role in PECAM-1-independent transmigration. Blood. 2006;107:4721–4727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostermann G, Weber KSC, Zernecke A, Schroder A, Weber C. JAM-1 is a ligand of the β2 integrin LFA-1 involved in transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:151–158. doi: 10.1038/ni755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber C, Fraemohs L, Dejana E. The role of junctional adhesion molecules in vascular inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nri2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reymond N, Imbert AM, Devilard E, Fabre S, Chabannon C, Xerri L, Farnarier C, Cantoni C, Bottino C, Moretta A, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. DNAM-1 and PVR regulate monocyte migration through endothelial junctions. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1331–1341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mamdouh Z, Chen X, Pierini LM, Maxfield FR, Muller WA. Targeted recycling of PECAM from endothelial cell surface-connected compartments during diapedesis. Nature. 2003;421:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nature01300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mamdouh Z, Kreitzer GE, Muller WA. Leukocyte transmigration requires kinesin-mediated microtubule-dependent membrane trafficking from the lateral border recycling compartment. J Exp Med. 2008;205:951–966. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Kowalski JR, Zhan X, Thomas SM, Luscinskas FW. Endothelial cell cortactin phosphorylation by Src contributes to polymorphonuclear leukocyte transmigration in vitro. Circ Res. 2006;98:394–402. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000201958.59020.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller WA. PECAM-1: an adhesion molecule at the junctions of endothelial cells. In: van Furth R, Cohn ZA, Gordon S, editors. Mononuclear Phagocytes The Proceedings of the Fifth Leiden Meeting on Mononuclear Phagocytes. Blackwell Publishers; London: 1992. pp. 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schenkel AR, Mamdouh Z, Muller WA. Locomotion of monocytes on endothelium is a critical step during extravasation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:393–400. doi: 10.1038/ni1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bird I, Taylor V, Newton J, Spragg J, Simmons D, Salmon M, Buckley C. Homophilic PECAM-1(CD31) interactions prevent endothelial cell apoptosis but do not support cell spreading or migration. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1989–1997. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu TT, Yan LG, Madri JA. Integrin engagement mediates tyrosine dephosphorylation on platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11808–11813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kogata N, Masuda M, Kamioka Y, Yamagishi A, Endo A, Okada M, Mochizuki N. Identification of Fer Tyrosine Kinase Localized on Microtubules as a Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Phosphorylating Kinase in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3553–3564. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Mas JC, Van Obberghen E. The adapter protein, Grb10, is a positive regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Oncogene. 2001;20:3959–3968. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber C, Negrescu E, Erl W, Pietsch A, Frankenberger M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Siess W, Weber PC. Inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinase suppress TNF-stimulated induction of endothelial cell adhesion molecules. J Immunol. 1995;155:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicmil M, Thomas JM, Sage T, Barry FA, Leduc M, Bon C, Gibbins JM. Collagen, Convulxin, and Thrombin Stimulate Aggregation-independent Tyrosine Phosphorylation of CD31 in Platelets. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27339–27347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalra VK, Shen Y, Sultana C, Rattan V. Hypoxia induces PECAM-1 phosphorylation and transendothelial migration of monocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2025–2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.5.H2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rattan V, Shen Y, Sultana C, Kumar D, Kalra VK. Glucose-induced transmigration of monocytes is linked to phosphorylation of PECAM-1 in cultured endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:E711–E717. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.4.E711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Buul JD, Allingham MJ, Samson T, Meller J, Boulter E, Garcia-Mata R, Burridge K. RhoG regulates endothelial apical cup assembly downstream from ICAM1 engagement and is involved in leukocyte trans-endothelial migration. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1279–1293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilan N, Madri JA. PECAM-1: old friend, new partners. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gratzinger D, Barreuther M, Madri JA. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 modulates endothelial migration through its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masuda M, Osawa M, Shigematsu H, Harada N, Fujiwara K. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is a major SH-PTP2 binding protein in vascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;408:331–336. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sagawa K, Kimura T, Swieter M, Siraganian RP. The Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-2 Associates with Tyrosine-phosphorylated Adhesion Molecule PECAM-1 (CD31) J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31086–31091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton-Nash DK, Newman PJ. A new role for platelet-endthelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31): Inhibition of TCR-mediated signal transduction. J Immunol. 1999;163:682–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller WA, Ratti CM, McDonnell SL, Cohn ZA. A human endothelial cell-restricted, externally disposed plasmalemmal protein enriched in intercellular junctions. J Exp Med. 1989;170:399–414. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller WA, Weigl S. Monocyte-selective transendothelial migration: Dissection of the binding and transmigration phases by an in vitro assay. J Exp Med. 1992;176:819–828. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]