Abstract

We report studies of the nonlinear nature of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) responses to short transient deactivations in human visual cortex. Both functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) have been used to compare and contrast the hemodynamic response functions (HRFs) associated with transient activation and deactivation in primary visual cortex. We show that signal decreases for short duration deactivations are smaller than corresponding signal increases in activation studies. Moreover, the standard balloon model of BOLD effects may be modified to account for the observed nonlinear nature of deactivations by appropriate changes to simple hemodynamic parameters without recourse to new assumptions about the nature of the coupling between activity and oxygen use.

Keywords: Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD), Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), Hemodynamic response functions (HRFs), Balloon model

1. Introduction

Functional MRI based on the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) effect records the magnetic resonance (MR) signal changes produced by alterations in tissue blood volume, flow and oxygenation. The time course of the BOLD signal change observed following a transient change in neural activity (the hemodynamic response function or HRF) reflects the physiological adjustments in blood flow and volume that accompany the changes in oxygen metabolic demand. These changes are not quantitatively matched to the changes in oxygen use and it is this mismatch that underlies the positive BOLD signal change. The MR signal increase following a transient excitation is believed to arise because the flow and oxygenation increase are greater than are required to meet metabolic demand. Conversely, during a steady state of continuous activation, an equilibrium is established between flow and metabolism. When a transient decrease in activation occurs (e.g., by interrupting a stimulus) the oxygen demand is reduced. Experimentally, the sub-sequent HRF for this “deactivation” corresponds to an MR signal decrease, suggesting that flow is reduced to a degree greater than that required to reestablish the same level of tissue oxygenation, or that oxygen demand remains high in the presence of decreased activity. The quantitative and temporal natures of the coupling of the physiological changes to decreases in neural activity are not well established. Furthermore, most analyses of event-related fMRI studies assume that the HRF for transient neural deactivation is simply the inverse of that for activation, which has not been established either [1–9].

We used transcranial near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) [10] and fMRI at 3 T to investigate both positive and negative BOLD effects. Using NIRS, we recorded relative concentration changes in both oxy- and deoxy- as well as total hemoglobin levels by measuring changes of absorption at two different wavelengths in brain in response to both transient activations and deactivations. Similar experiments were also performed using fMRI. The BOLD response to transient activations has been well studied previously, and for successive short duration stimuli the BOLD responses do not add linearly [11–13], but overpredict the effects of longer durations of a stimulus. A further characteristic of a linear system is that changes in response to both activation and deactivation should be reciprocal, but relatively few studies have looked at deactivations. Birn and Bandettini [14] found the decrease in BOLD to removing a stimulus for short durations was smaller than predicted by a linear system. Hence, the BOLD response to both activation and deactivation is not reciprocal. The BOLD effect reflects changes in neuronal activity, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen, cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume, and the precise nature of these is different for negative and positive BOLD signals.

We have investigated the hemodynamic response functions in visual cortex in response to both short activations (relative to a resting baseline) as well as to short interruptions of a steady-state activating stimulus (deactivations). We also compared BOLD and NIRS measurements during various stimulation paradigms and have developed modifications to the standard balloon model [15,16] to account for the results. The extent to which positive and negative responses differ may shed light on models of BOLD responses and is important for the design and interpretation of experiments and for choosing appropriate methods of data analysis.

2. Method

2.1. Subjects

A total of 12 healthy volunteers (four females, mean age 25.8, range 21–30 years) participated in the studies. All had normal or corrected to normal vision. Written informed consents were obtained from all volunteers prior to the examinations. Five of the subjects participated in the NIR experiments and 10 of the subjects in fMRI experiments. Three of the subjects participated in both the NIR and fMRI experiments. All subjects were instructed to keep their eyes open and maintain constant attention throughout all experiments.

2.2. Stimulus presentation

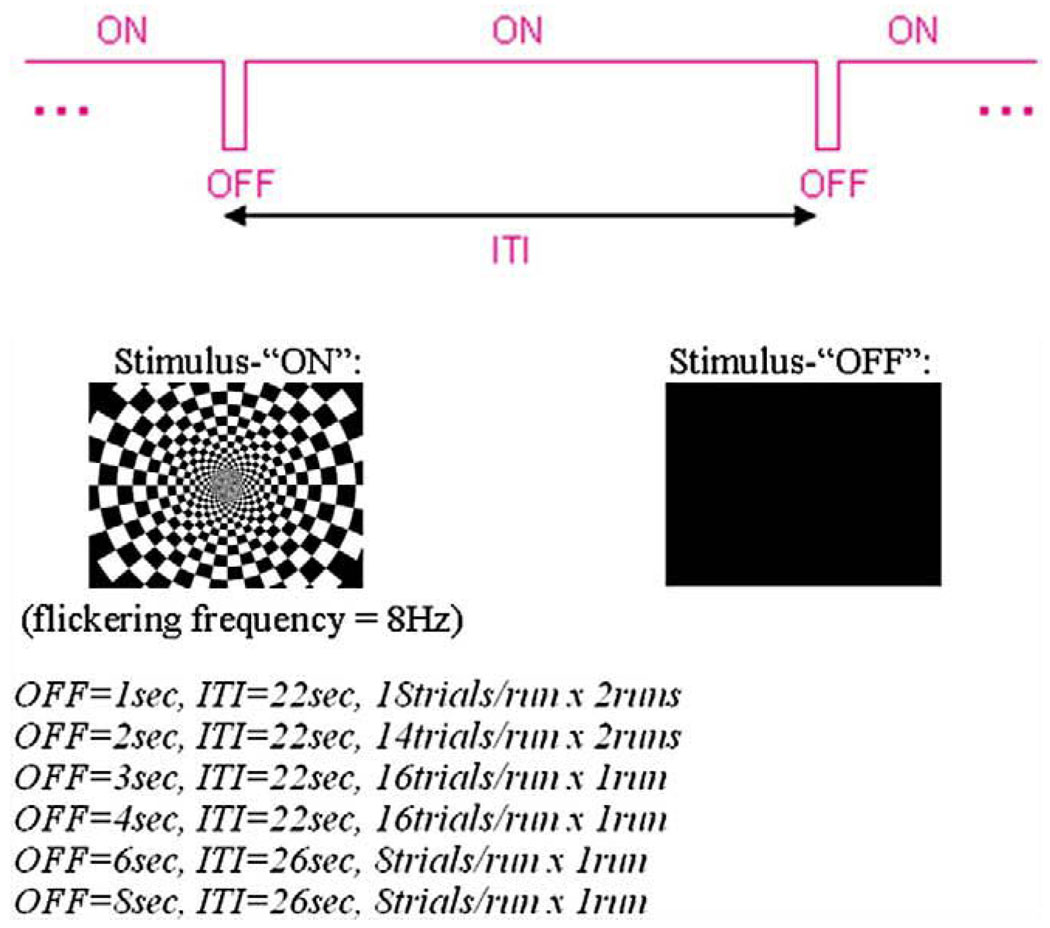

An 8-Hz large-field contrast-reversing checkerboard pattern at 100% contrast served as a visual excitation stimulus (denoted as condition “ON”). A spatially uniform black screen served as a second condition (“OFF”). The scanner room lights were dim during all examinations. Combinations of these stimuli generated by E-prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.) were presented to the subjects in an event-related manner (Fig. 1): various durations of visual inactivity (stimulus “OFF” for 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 or 8 s) were interspersed during otherwise continuous visual stimulation (“ON”) to assess the ability to detect transient deactivations and to test the signal linearity. A total of eight scan runs were acquired, consisting of two repeated runs each of 1-s (18 trials/run) and 2-s (14 trials/run) duration of stimulus-OFF, and one run each of 3-s (16 trials/run), 4-s (16 trials/run), 6-s (8 trials/run) and 8-s (8 trials/run) duration of stimulus-OFF. Each run started with a flashing checkerboard (“ON”) for 22 s, followed by the variable durations of stimulus-OFF. The stimulus interval was 22 s for 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-s stimulus-OFF and 26 s for the 6- and 8-s stimulus-OFF.

Fig. 1.

Stimulus presentation in Paradigm III.

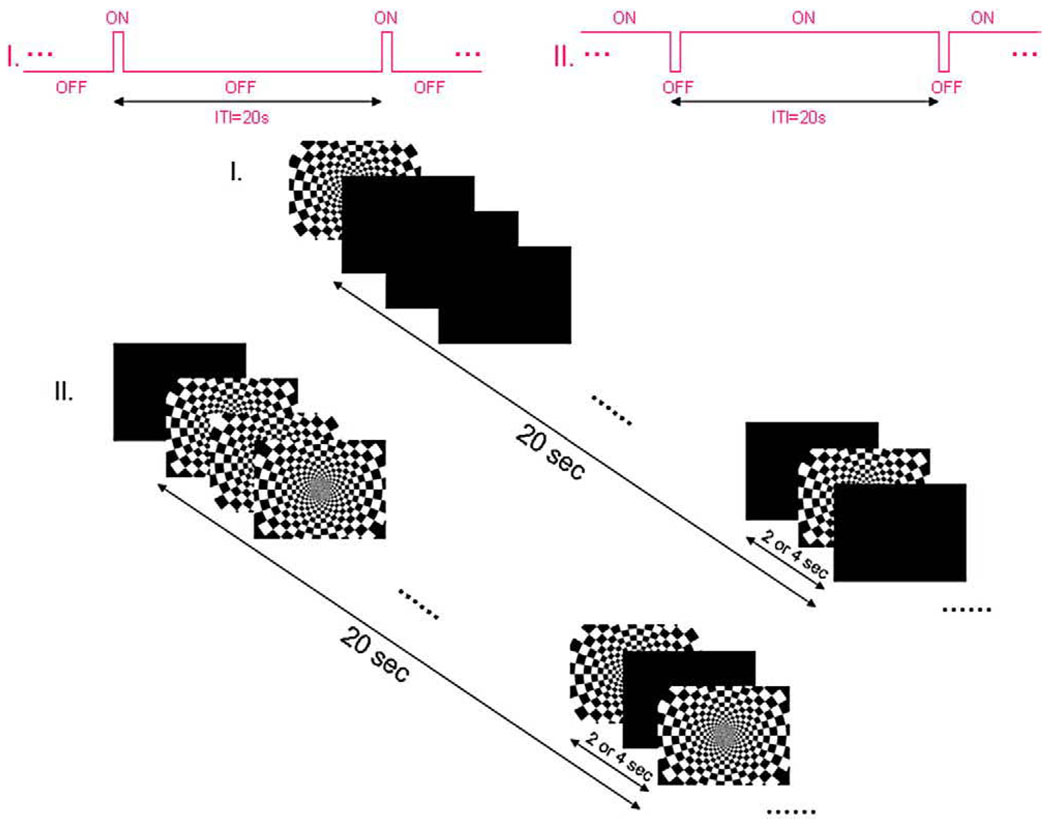

We also investigated the hemodynamic response functions in visual cortex in response to transient activations as well as to transient deactivations. Two reverse event-related paradigms (Fig. 2) were generated using E-prime (Psychology Software Tools) and presented to the subjects: in the first, a transient activating stimulus (stimulus ON for 2 or 4 s) was presented within an otherwise continuous black screen (OFF). In the second, a transient deactivation was produced [stimulus OFF for 2 or 4 s, interspersed during an otherwise continuous visual stimulation (ON)]. In total, 80 trials were presented in four runs, and each condition (2 or 4 s of flickering checkerboard ON and 2 or 4 s of black screen OFF) was presented 20 times with a 20-s target-to-target interval. In addition, the pattern of baseline condition was always viewed for 20 s before the first target presentation to reach a steady state.

Fig. 2.

Two reverse paradigms (I and II) of stimulus presentation.

To localize each subject's visual area, we performed a retinotopic mapping in which a traveling wedge of flickering checkerboard was presented before the actual functional runs.

2.3. Data acquisition

NIR data were collected using a multi-channel (3×5) near-infrared optical topography system (Hitachi topoETG4000). Optodes were positioned to be able to sample signals from a central posterior region corresponding to the primary visual cortex. Optical signals representing [Hb], [HbO2] and total blood relative volume changes were collected as described previously [10].

MR images were acquired on a 3-T Philips Achieva using an eight-channel SENSE head coil. Ten T1-weighted anatomic images were collected parallel to a line passing through the anterior–posterior commissures (AC-PC line) with 5 mm slice thickness and 1-mm gap and positioned to cover the visual areas. Then functional BOLD images were collected in the same planes, using a gradient echo EPI sequence (TR/TE=1 s/35 ms, flip angle=70°, FOV=22×22cm2 and acquisition matrix size=80×80 reconstructed to 128×128).

2.4. Data analysis

The hemoglobin concentration changes in different zones of the visual cortex obtained using the NIR spectrometer and the BOLD signals obtained from the MR scanner were both analyzed using BrainVoyager QX and additional software running under MATLAB.

fMRI data were first motion corrected, realigned and coregistered with T1-weighted structural images collected using identical slice prescriptions, then registered to Talaraich coordinates. We performed an event-related general linear model analysis to compute the activation maps and then examined the time courses of the signals within the activated regions of interest for both transient activations and deactivations.

NIR data were down sampled from 10 to 1 Hz, temporally filtered (using a linear trend filter), then analyzed to obtain measurements of the event-related oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration changes for both ON and OFF stimuli.

3. Results

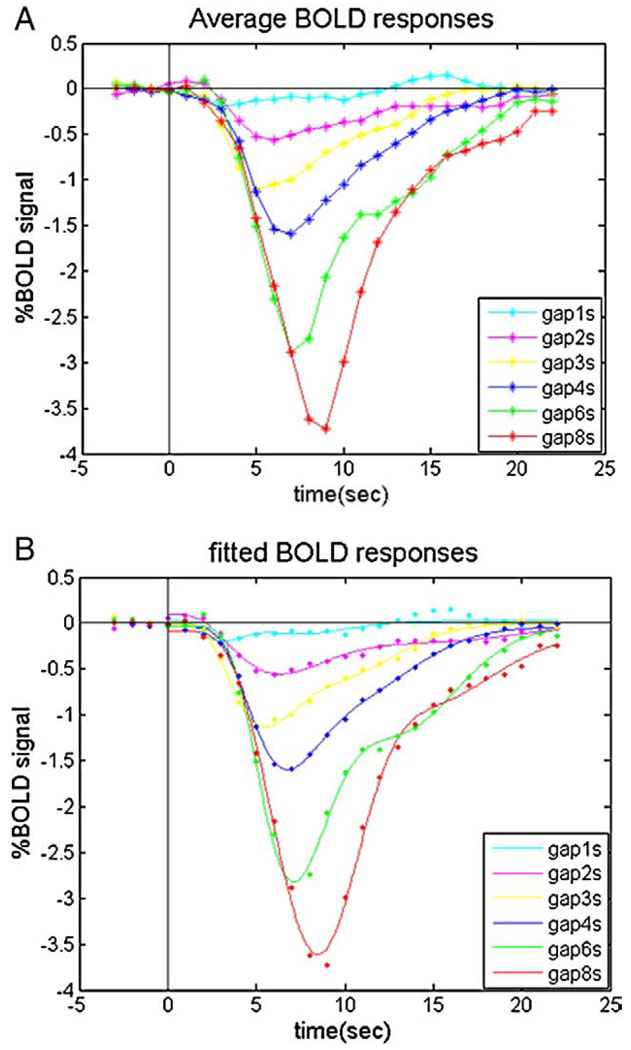

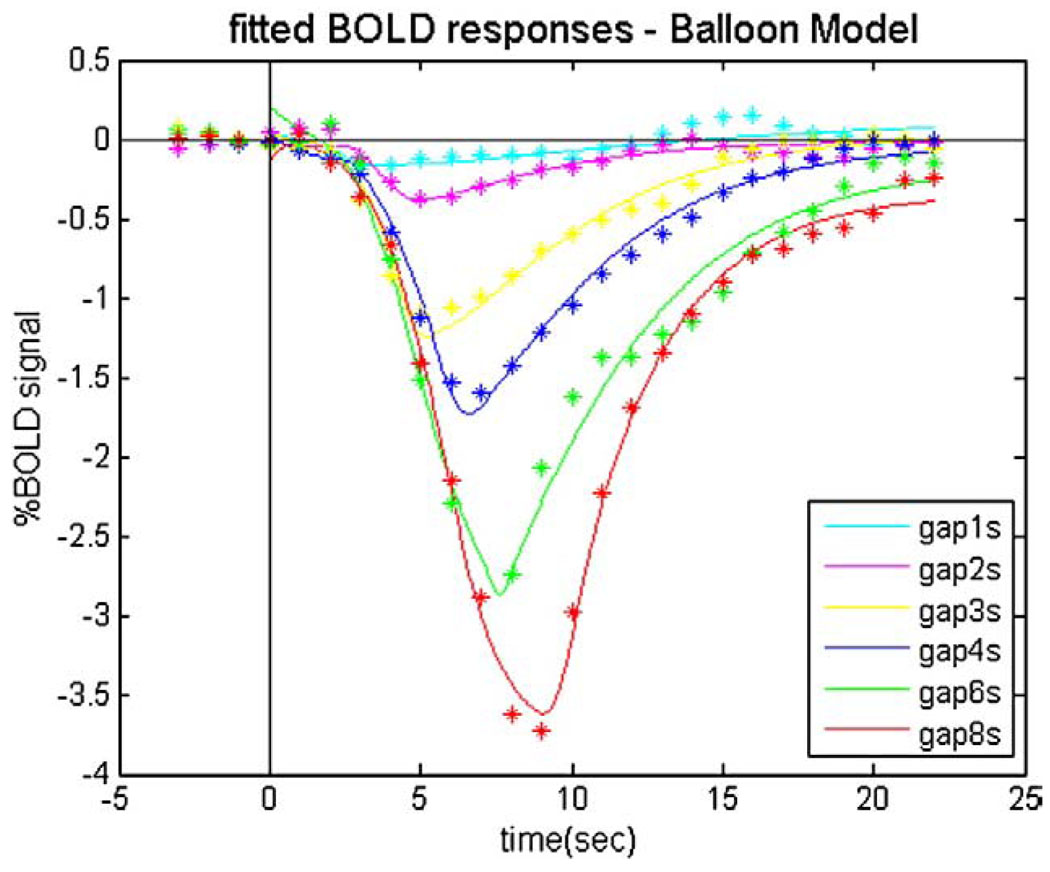

Negative BOLDr esponses (or signal decreases) were found when the flickering checkerboard was interrupted. Fig. 3A shows the BOLD response curves following stimulus gaps ranging from 1- to 8-s duration, averaged across subjects.

Fig. 3.

The average (n=5) event-related BOLD signal changes in the primary visual cortex in response to varying durations of stimulus interruption. (A) Measured BOLD responses; (B) fitted BOLD responses using the gamma-variate function.

We performed a least squares fit of the experimental signal–time curves with a double gamma-variate function of the form [17]

| (1) |

The fitted initial values for visual areas were selected as: a=7, b=0.9, d=6.3, a’=14, b’=0.9, d’=12.6, c=0.35, E=0.05.

Then we obtained the magnitude and temporal parameters of the fitted hemodynamic response functions (Fig. 3B) as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4. Comparing the fitted responses, we found that the deactivations to very short durations (<2 s) of stimulus OFF were barely detectable in area V1.

Table 1.

List of the amplitudes of peak and the time to peak for fitted BOLD response to varying durations of stimulus interruption

| Duration of gaps | 1 s | 2 s | 3 s | 4 s | 6 s | 8 s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (%) | −0.20 | −0.38 | −1.13 | −1.60 | −2.82 | −3.61 |

| Time to peak (s) | 3.15 | 5.28 | 5.56 | 6.76 | 7.12 | 8.48 |

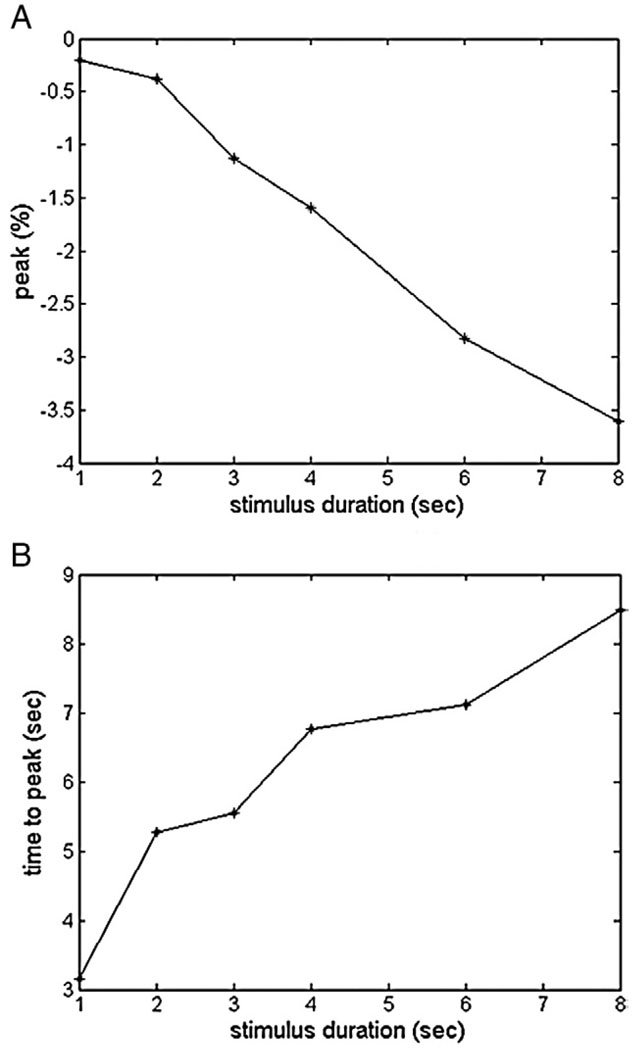

Fig. 4.

Trend of the amplitudes of peak and the time to peak for fitted BOLD response to varying durations of stimulus interruption.

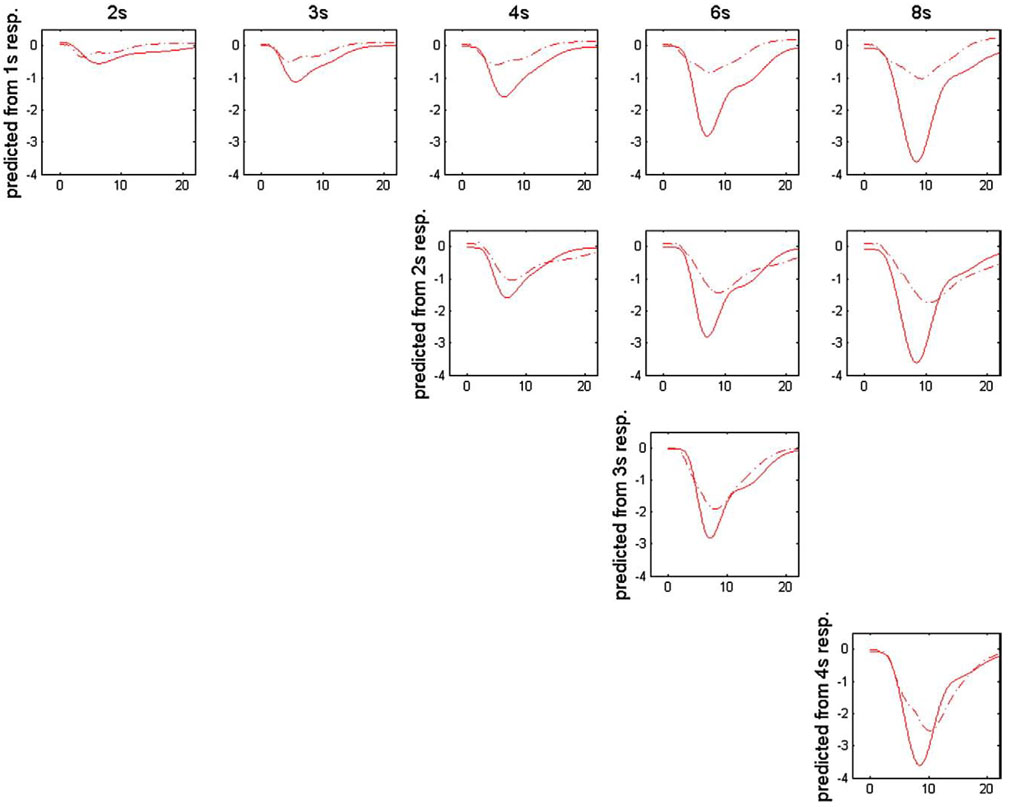

As shown in Fig. 5, we used the responses to shorter stimulus gaps to predict the responses to longer gaps. Unlike the corresponding prediction of activation responses [11–13], the predicted curves of deactivation signals always tend to underestimate the experimental responses.

Fig. 5.

Comparison between the measured (solid line) and predicted (dash line) BOLD response curves assuming linearity. The predictions using the response to shorter duration gaps are shown in the same row, and the measured responses to 2-, 3-, 4-, 6- and 8-s stimulus gaps plotted together with the corresponding predictions are shown in different columns.

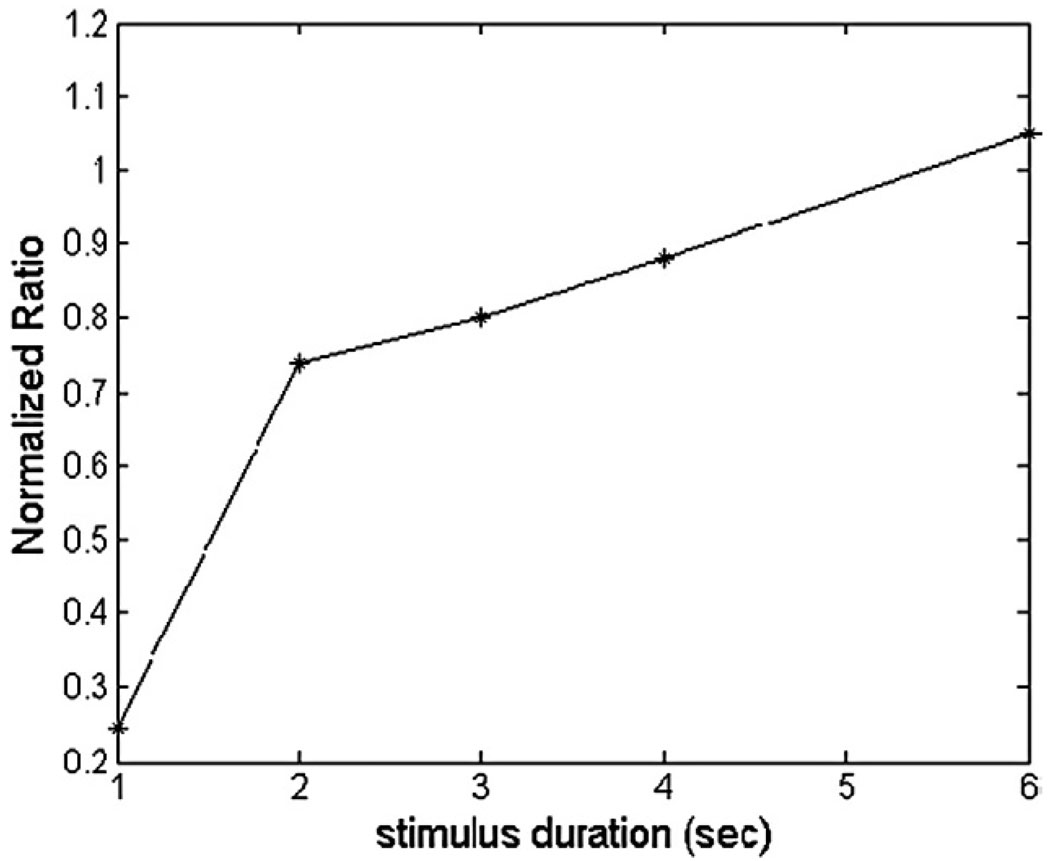

The ratios of the areas under the experimental BOLD response curves to various durations of the stimulus-OFF were calculated, with the ratio at the longest duration (8 s) normalized to 1, as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The normalized ratio of the area under the average BOLD responses curve to various durations of the stimulus-OFF. NR>1: overestimate the responses to longer duration of gap; NR=1: perfect prediction (ideal linear systembehavior);NR<1: underestimate the responses to longer duration of gap.

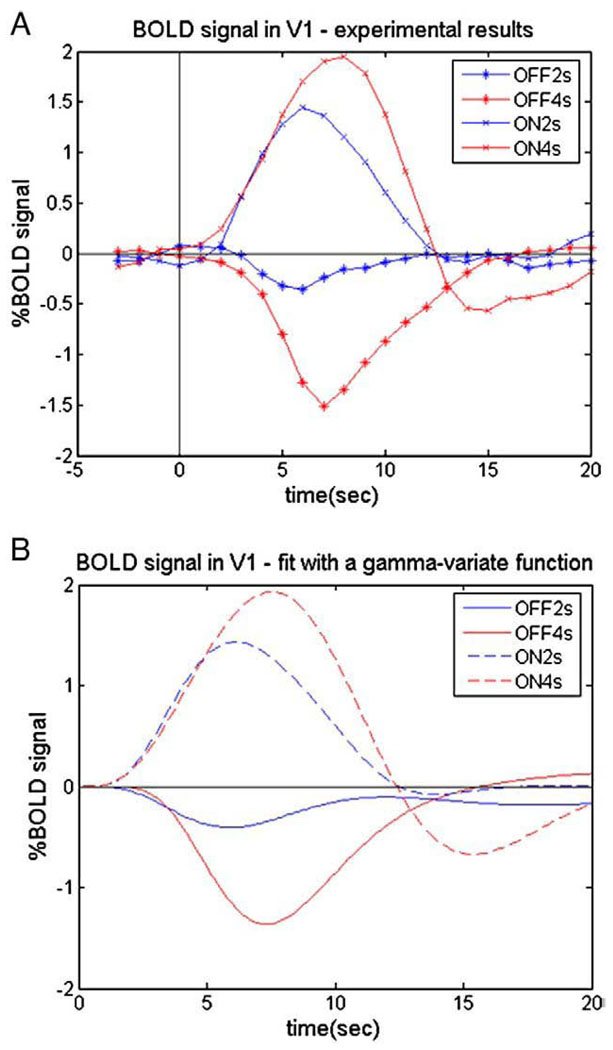

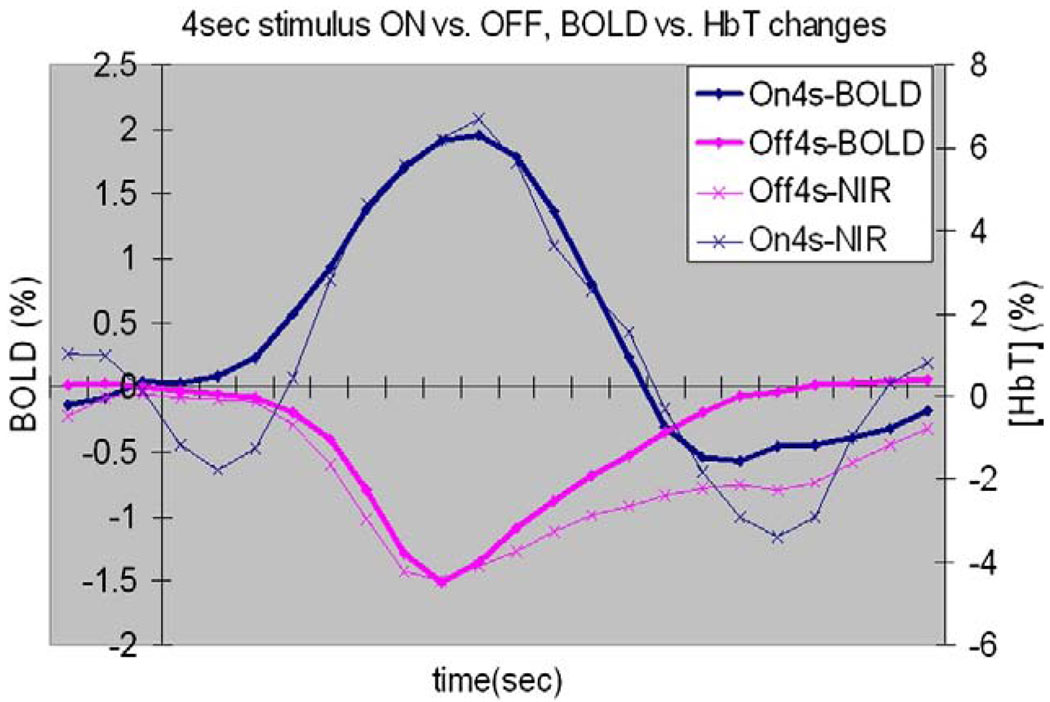

The BOLD MR signal in primary visual area V1 showed different transient hemodynamic responses to the ON and OFF conditions as expected. A positive BOLD effect was found in V1 in response to the brief checkerboard stimuli, whereas a negative BOLD response (or signal decrease) was found when the checkerboard was interrupted (Fig. 7A). To compare the activation and deactivation responses, again, we performed a least squares fit of the experimental signal–time curves with a gamma-variate function of the form of Eq. (1) [17].

Fig. 7.

BOLD responses in VI. (A) Measured BOLD responses; (B) fitted BOLD responses using the gamma-variate function. Deactivation responses are smaller and have longer latency but shorter time to peak, more narrow width and no significant post overshoot.

We then obtained the magnitudes and temporal parameters of the fitted hemodynamic response functions (Fig. 7B) as shown in Table 2. Comparing the fitted responses, we found that the deactivation response to a 2-s stimulus OFF was very small in V1 compared to the positive signal increase recorded for a 2-s ON stimulus. In addition, the ON responses for 2 and 4 s were not related in strictly linear fashion, in agreement with previous reported investigations [18] which verified that both the CBF and BOLD response nonlinearities showed an overprediction of the ON response magnitude for long-duration responses based on summing short-duration responses in primary visual area. However, the OFF responses behaved quite differently: the negative BOLD changes did not behave linearly and the predictions using short-duration data tend to underestimate the OFF responses to longer durations of deactivation. These results are consistent with the previous report of Birn and Bandettini [14]. The deactivation responses were smaller and also had slightly longer latencies and shorter times to peak and showed no significant post-stimulus overshoots.

Table 2.

Amplitudes of peak and post undershoot/overshoot, time to peak and post undershoot/overshoot for BOLD response to stimulus-ON (2 or 4 s) and stimulus-OFF (2 or 4 s)

| Parameters | T_peak (s) |

A_peak (%) |

T_undershoot (s) |

A_undershoot (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| on2s | 6.12 | 1.43 | 13.88 | −0.08 |

| on4s | 7.53 | 1.93 | 15.37 | −0.67 |

| off2s | 5.90 | −0.41 | – | – |

| off4s | 7.31 | −1.37 | – | – |

There are significant differences in T_peak.

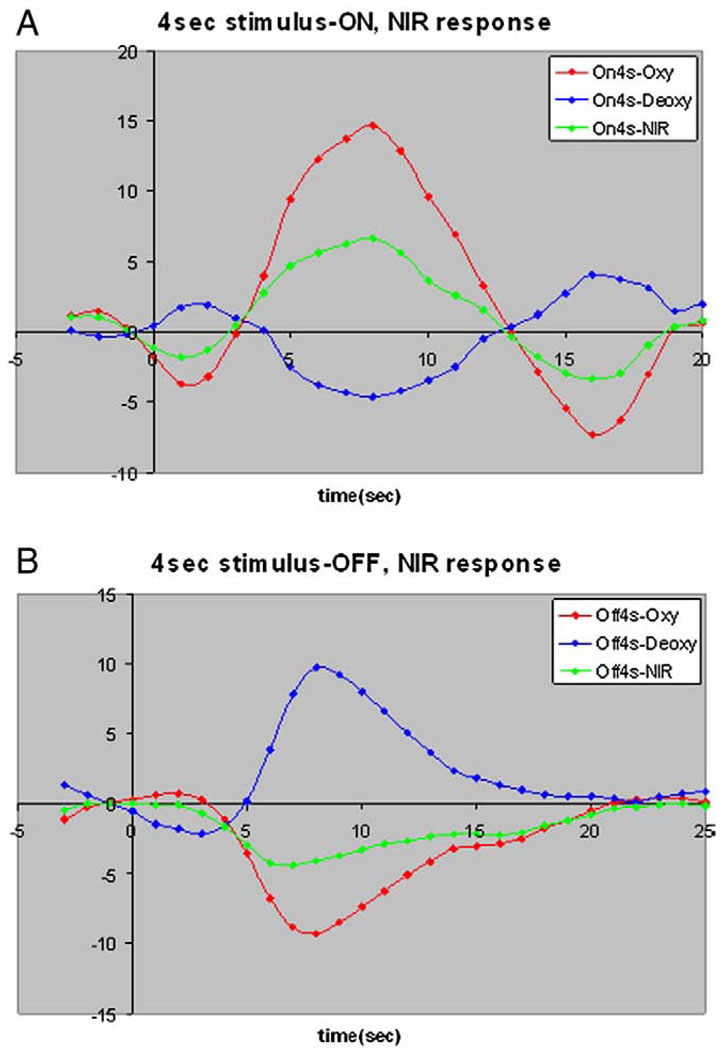

The NIR data also showed transient changes in both oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobins (Fig. 8) consistent with the BOLD data. In response to the transient deactivation (Fig. 8B), the total hemoglobin in the visual cortical area sampled by the NIR optodes decreased, and there was a corresponding increase in tissue deoxy-hemoglobin. The time course for vasoconstriction when regions deactivate does not appear significantly slower than that for vasodilation when areas activate. Our NIR studies found, as expected, that brief (4 s) activation increased oxy- (HbO2) and total hemoglobin (HbT) and decreased deoxyHb (Hb) (Fig. 8A), while transient deactivation decreased HbT and HbO2, and increased Hb in V1 (Fig. 8B). Also, the pre-undershoot/overshoot and post-undershoot/overshoot are more pronounced for NIR data in response to brief activation as compared to the response to brief deactivation.

Fig. 8.

Transient changes in both oxy-hemoglobin and deoxy-hemoglohin in VI. (A) NIR data in response to 4-s stimulus-ON. (B) NIR data in response to 4-s stimulus-OFF.

These observations were qualitatively and quantitatively consistent with the observed fMRI time courses for a 4-s activation/deactivation (Fig. 9), verifying that NIRS can be used as an alternative method for measuring hemodynamic responses in event-related studies of activation [10]. The total hemoglobin, which reflects the change of blood volume, showed a similar behavior to the BOLD response, but the blood volume change to stimulus onset was a little bit slower, whereas the volume change to stimulus offset was slightly faster. However, the NIR response to 2-s deactivation was again significantly blunted compared with that for the 2-s activation, suggesting that the assumption of a universal HRF for all fMRI activations and deactivations needs closer scrutiny.

Fig. 9.

Compare BOLD responses with NIR [HbT] responses to 4-s stimulus-ON/OFF in VI. They showed similar relative magnitude and temporal properties for activation and deactivation.

Both the fMRI and NIRS data demonstrate the HRF to deactivation is smaller and has a different time course to the HRF for transient activation. Moreover, the HRF for deactivation exhibits a greater degree of nonlinearity. Our ability to detect short (<2 s) deactivations is therefore less than our ability to detect corresponding activations. During a steady-state excitation, equilibrium is achieved between blood flow, volume and oxygenation. When this is interrupted, the sequence of physiological changes is different from those involved in the vasodilation that occurs in response to transient excitations, and the HRF presumably reflects those differences.

3.1. Balloon model

To account for our findings, we adapted the standard balloon model [15,16] in which flow is regulated in a manner that leads to over- and under swings in blood oxygenation relative to the levels required to maintain metabolic demand [1,2,6,8]. The key physiological variables incorporated in the model are the total deoxyhemoglobin (q) and the blood volume (v), both normalized to their values at rest. In this model, the fractional BOLD signal change is written as:

| (2) |

where k1, k2, k3 are dimensionless parameters and depend on several experimental and physiological parameters, and V0 is the resting venous blood volume fraction.

The central idea of the model is that the venous compartment is treated as a distensible balloon. The inflow to the balloon fin is the cerebral blood flow, while the outflow from the balloon fout is an increasing function of the balloon volume. The two dynamical variables are the total deoxyhemoglobin q(t) and the volume of the balloon v(t). Equations may then be developed assuming conservation of mass for blood and deoxyhemoglobin as they pass through the venous balloon:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where τ0 is the mean transit time through the balloon at rest, E(t) is the oxygen extraction fraction and E0 is the resting oxygen extraction fraction.

In our simulations, the outflow (Eq. (20)) was modeled as a pure function of blood volume v. Experimental studies of altered flow states [19] have indicated that the steady-state relationship between cerebral blood volume (CBV) and flow (CBF) can often be described by an empirical power law: v=fα. However, the prevailing conditions during the transition between steady-state levels may be different. For calculation purposes, Buxton proposed a simple model for such viscoelastic effects in which fout is treated as a function both of the balloon volume and the rate of change of that volume [15,16].

| (5) |

| (6) |

where α is the stiffness exponent coefficient and τ controls how long this transient adjustment requires.

From the given initial conditions and using careful selections of the model parameters ki, V0, E0, α and τ0 (which may be estimated from early numerical and experimental measurements: k1=7E0 [20], k2=2, k3=2E0−0.2 [21]), different temporal patterns of response may be created for different functional forms of fin(t). In our case, we chose V0=0.03, E0=0.4, α=0.5 and τ0=4 for the initial values for responses to visual stimulus-ON. These are typical resting values. However, this baseline condition is changed after viewing continuous visual stimulation (“ON”), so V0=0.04, E0=0.26, α=0.5 and τ0=4 are the initial values for transient responses to stimulus-OFF. These values are steady-state values which were generated from the resting values.

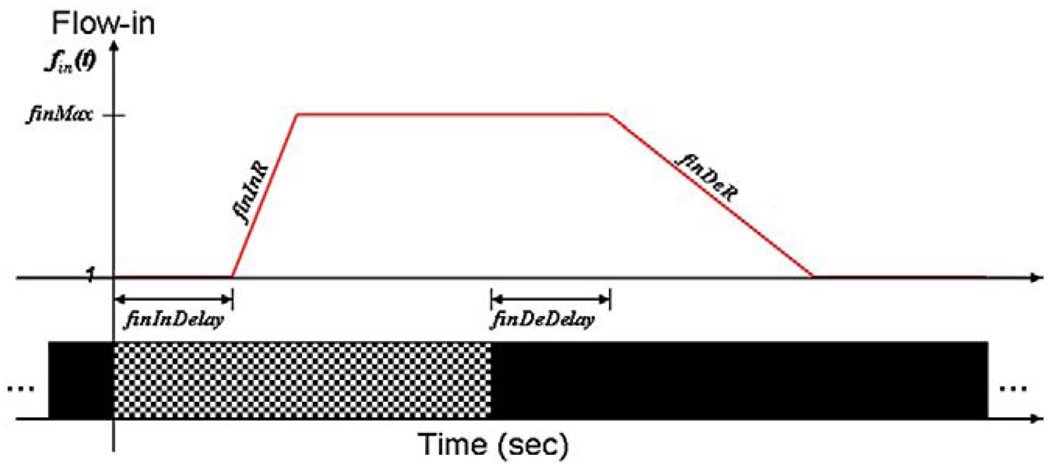

We performed a least squares fit of the experimental signal–time curves of the fractional BOLD signal change using Eqs. (2), (3) and (4). To obtain the value of fin(t) at any specified time, we assume =1 at rest and introduce some new parameters: maximal inflow, denoted as finMax; inflow decrease rate |dfin/dt|activation, denoted as finDeR; inflow increase rate |dfin/dt|deactivation, denoted as finInR; delay of inflow increase with response to stimulus-ON, denoted as finInDelay; and delay of inflow decrease with response to stimulus-OFF, denoted as finDeDelay (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Functional form of Flow-in based on the introduced parameters: finMax, finDeR (l/s), finInR (1/s), finInDelay (s) and finDeDelay (s).

To solve the nonlinear data fitting, the initial values were selected as finMax=1.6, finDeR=1.2 s−1, finInR=0.3 s−1, finDeDelay=2 s and finInDelay=1.5 s. The best fitting parameters derived by least squares curve fitting for each data set are shown in Table 3, and fitted BOLD responses to deactivations by the modified balloon model are shown in Fig. 11.

Table 3.

List of the parameters which are used to describe functional forms of fin(t) in the balloon model; they were derived by least squares curve fitting of experimental data

| finMax | finDeR (s−1) | finInR (s−1) | finDeDelay (s) | finInDelay (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFF_1s | 1.61 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 1.95 | 1.26 |

| OFF_2s | 1.59 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 2.00 | 1.43 |

| OFF_3s | 1.56 | 0.15 | 0.89 | 1.55 | 2.05 |

| OFF_4s | 1.51 | 0.12 | 0.62 | 2.27 | 2.27 |

| OFF_6s | 1.51 | 0.14 | 1.53 | 2.00 | 1.49 |

| OFF_8s | 1.59 | 0.13 | 0.86 | 1.89 | 1.04 |

| Average | 1.56 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 1.94 | 1.59 |

Fig. 11.

BOLD responses to deactivation and their fits. The data can be well modeled by the modified balloon model.

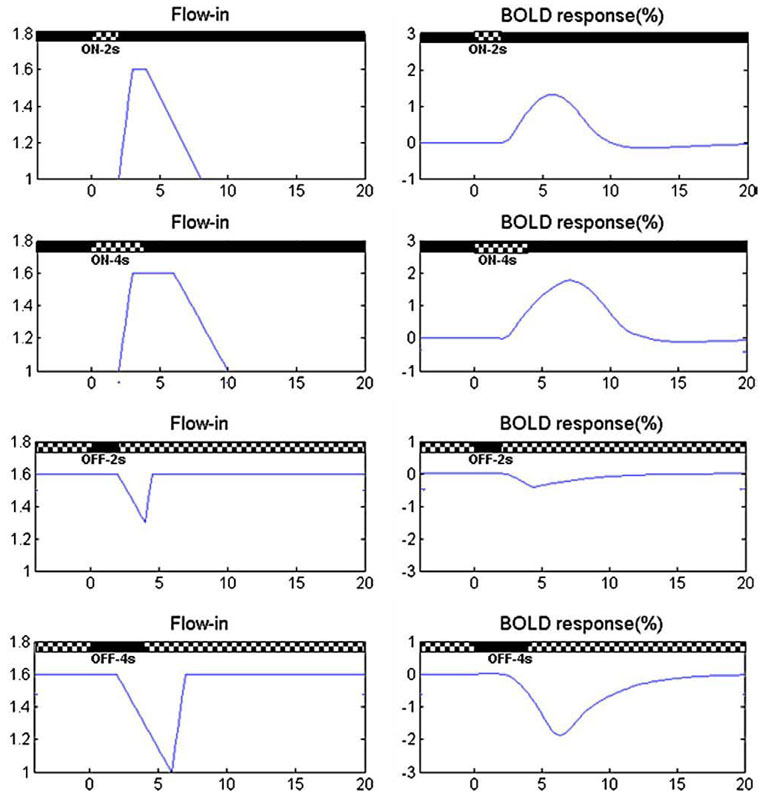

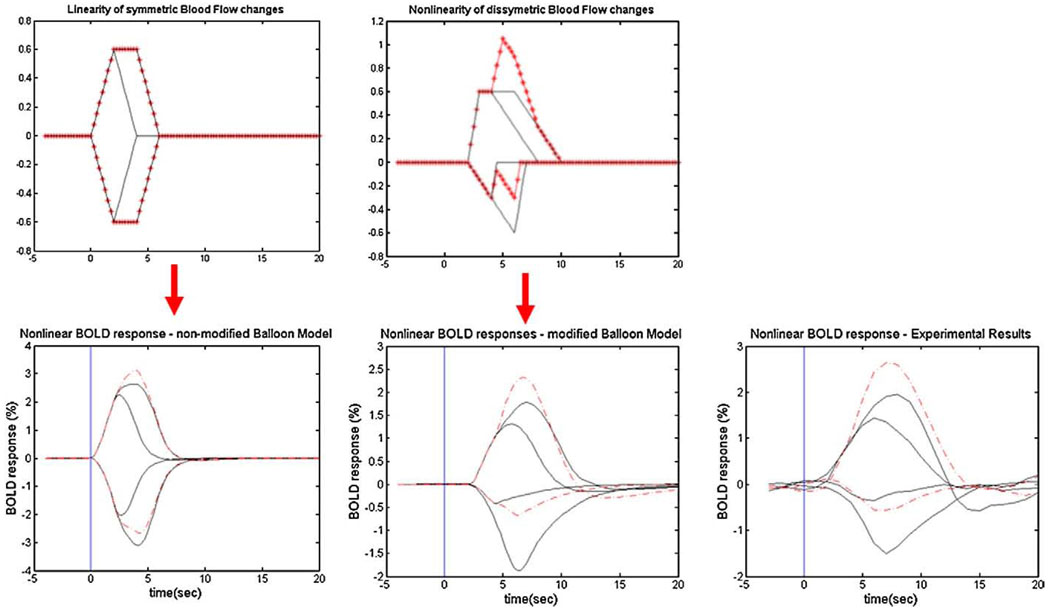

As shown in Fig. 11, the modified balloon model fits the BOLD responses to deactivations quite well. Table 3 suggests that it takes longer for the blood inflow to change in response to stimulus OFF than to ON. These are consistent with the experimental results that BOLD response to deactivation has longer latency as seen in Fig. 7. It also shows that the increase in the rate of blood inflow to an activation is usually larger than the rate of decrease when deactivating. Based on these fitting results, nonlinear responses can be obtained from the model by assuming different time courses for flow decreases compared to flow increases. For example, if we assume the Flow-in at rest is 1, and maximal Flow-in is 1.6, we can then also postulate that the increase of Flow-in during balloon inflation occurs more rapidly than the decrease of Flow-in during deflation. If we set the time for Flow-in to reach its maximum to be 1 s, but the time for it to go back to the rest level as 4 s, then we obtain significant differences in Flow-in patterns in response to the ON or OFF conditions for different stimulus durations, as shown in the left column in Fig. 12. Here the delay of Flow-in changes in response to both the ON and OFF conditions is set to 2 s. We select the time τ± in Eq. (6) as the time of Flow-in to increase or decrease. In this way, we are able to obtain different patterns of BOLD responses to stimulus-ON/OFF, as shown in the right column in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

BOLD responses obtained by the balloon model using different patterns of Flow-in.

With these small but significant modifications, the nonlinearities and shapes of the BOLD responses to both activations and deactivations obtained by the balloon model agree well with our experimental results (Fig. 13). For example, the absence of a post-stimulus overshoot for BOLD responses to transient stimulus-OFF and the magnitudes of the BOLD responses to short OFF stimuli were well modeled. Unlike the case of the BOLD response to activation, linear convolution of HRFs from short duration interruptions tends to underestimate BOLD responses for deactivations. The standard balloon model predicts nonlinear superposition of HRFs, but it predicts reciprocal behavior for transient activations and deactivations. As shown in Fig. 13, the modified balloon model models the BOLD responses to both activation and deactivations well and does not predict reciprocal HRFs.

Fig. 13.

BOLD responses obtained by the nonmodified and modified balloon model compared to experimental results. Red dash line shows linear convolution of HRF to 2 s. The modified balloon model predicts the experimental data better and shows similar nonlinear properties of BOLD response to both activations and deactivations.

The nonlinear responses can be explained by different Flow-in time constants to stimulus onsets and offsets, suggesting that BOLD fMRI closely reflects the underlying nonlinear relationships of physiological factors and asymmetric Flow-in increases compared to decreases.

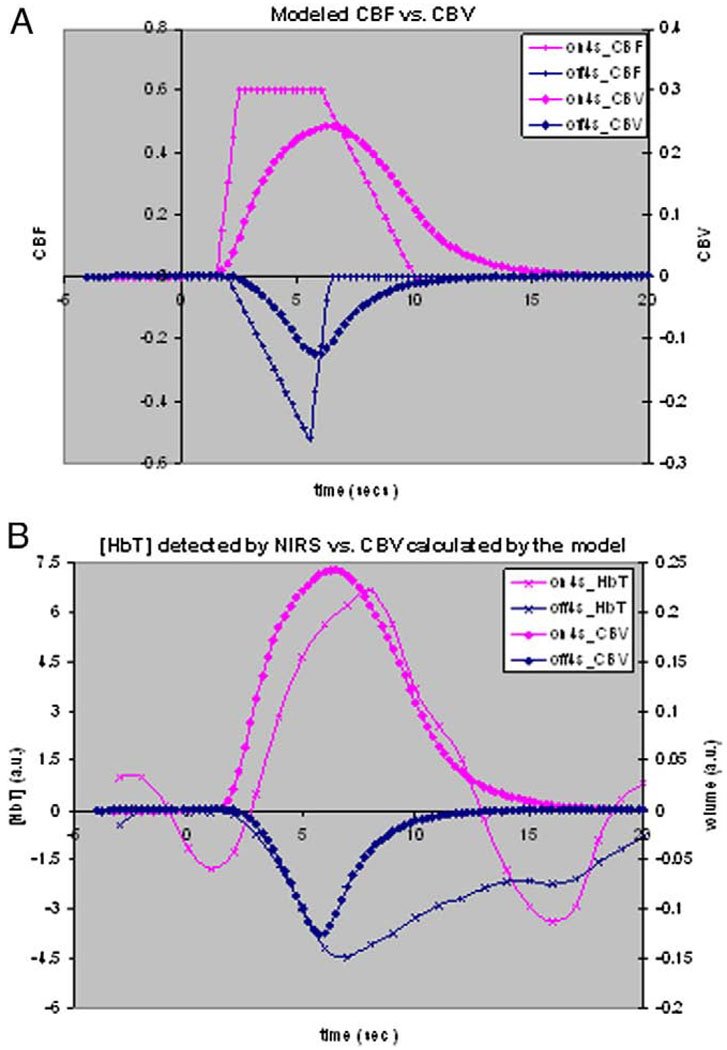

The simulations in this modified balloon model study not only show accurate estimations of observed BOLD dynamics, but they also show reasonable nonlinear hemodynamic relationships between underlying physiological variables. Fig. 14A shows that blood volume dynamics are always slower than flow changes during both stimulus onset and cession period. These timing differences have been used to explain the post-stimulus undershoot that is often observed for activation. NIRS experiments also verified this. As shown in Fig. 14B, concentration changes of total hemoglobin, which are associated with blood volume changes, show a smaller and slower decrease during the OFF period, which is consistent with the blood volume changes predicted by this modified balloon model.

Fig. 14.

(A) Simulation of blood volume compared with functional form of blood flow, using the modified balloon model. (B) Simulated blood volume shows a smaller and slower decrease during the OFF period and is consistent with the change patterns of total hemoglobin detected by NIRS.

4. Conclusion

We have investigated the hemodynamic response functions (HRFs) in the visual cortex in response to both short activations (relative to a resting baseline) and short interruptions of a steady-state activating stimulus (deactivations). Transient deactivation is not the mirror image of transient activation. The HRF for deactivation differs in magnitude and shape to that for increased activation. For short-duration stimuli, the HRFs do not add linearly and the magnitude of deactivation responses is smaller than for activation. The sensitivity to detect transient deactivation is therefore lower than for detecting activation. The extent to which these responses differ may shed light on models of BOLD responses and is important for the design and interpretation of experiments and methods of data analysis.

We modified the balloon model by assuming that the increase of Flow-in during inflation occurs more rapidly than the decrease of Flow-in during deflation. By this means the experimental responses can be well modeled, and the different nonlinear properties for both activation and deactivation were also predicted. The nonlinearity responses can be explained by different flow-in time constants for stimulus onsets and offsets, suggesting that hemodynamic effects alone can explain the causes of the nonlinear BOLD fMRI responses.

Acknowledgment

We thank Robin Avison and Donna Butler for technical assistance, Chris Cannistraci and Blake Niederhauser for discussion and constructive comments, and Nancy Hagans for helpful administrative coordination.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 EB000461.

References

- 1.Buxton RB, Frank LR. A model for the coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during neural stimulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:64–72. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friston KJ, Mechelli A, Turner R, Price CJ. Nonlinear responses in fMRI: the balloon model, Volterra kernels, and other hemodynamics. Neuroimage. 2000;12:466–477. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobbie R. Intermediate physics for medicine and biology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 136–227. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyder F. Neuroimaging with calibrated fMRI. Stroke. 2004;35(Suppl I):2635–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143324.31408.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duysens J, Schaafsma SJ, Orban GA. Cortical off response tuning for stimulus duration. Vision Res. 1996;36(20):3243–3251. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(96)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayhew J, Johnston D, Martindale J, Jones M, Berwick J, Zheng Y. Increased oxygen consumption following activation of brain: theoretical footnotes using spectroscopic data from barrel cortex. Neuroimage. 2001;13:973–985. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412(6843):150–157. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obata T, Liu TT, Miller KL, Luh WM, Wong EC, Frank LR, et al. Discrepancies between BOLD and flow dynamics in primary and supplementary motor areas: application of the balloon model to the interpretation of BOLD transients. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ellerman JM, et al. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J. 1993;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennan RP, Horovitz SG, Maki A, Yamashita Y, Koizumi H, Gore JC. Simultaneous recording of event-related auditory oddball response using transcranial near infrared optical topography and surface EEG. Neuroimage. 2002;16:587–592. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ. Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu HL, Gao JH. An investigation of the impulse functions for the nonlinear BOLD response in functional MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;18:931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robson MD, Dorosz JL, Gore JC. Measurements of the temporal fMRI response of the human auditory cortex to trains of tones. Neuroimage. 1998;7:185–198. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birn RM, Bandettini PA. The effect of stimulus duty cycle and “off” duration on BOLD response linearity. Neuroimage. 2005;27:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buxton RB, Uludag K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modeling the hemo-dynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S220–S233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton RB, Wong EC, Frank LR. Dynamics of blood flow and oxygenation changes during brain activation: the balloon model. MRM. 1998;39:855–864. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao CH, Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Aston JAD, Duncan GH, Evans AC. Estimating the delay of the fMRI response. Neuroimage. 2002;16:593–606. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller KL, Luh WM, Liu TT, Martinez A, Obata T, Wong EC, et al. Nonlinear temporal dynamics of the cerebral blood flow response. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;13:1–12. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grubb RL, Raichle ME, Eichling JQ, Ter-Pogossian MM. The effects of changes in PaCO2 on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and vascular mean transit time. Stroke. 1974;5:630–639. doi: 10.1161/01.str.5.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa S, Lee TM, Kay AR, Tank DW. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9868–9872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boxerman JL, Bandettini PA, Kwong KK, Baker JR, Davis TL, Rosen BR, et al. The Intravascular contribution to fMRI signal change: Monte Carlo modeling and diffusion-weighted studies in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:4–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]