Abstract

Purpose

The antiviral activity of an established antibacterial CAP37 domain and its extracellular mechanism of action were investigated.

Methods

CAP37-derived peptides modified to assess the importance of disulfide bonds were evaluated in cytotoxicity, and antiviral assays (direct time kill, dose-dependency and TOTO-1) for adenovirus (Ad) and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1).

Results

Variable virus, adenovirus serotype-dependant, and dose-dependent inhibition were demonstrated without cytotoxicity. For Peptide A (CAP3720-44), TOTO-1 dye uptake was demonstrated for Ad5 and HSV-1.

Conclusions

Unlike the antibacterial activity of this CAP37 domain, its antiviral activity is not fully dependent upon disulfide bond formation. Viral inhibition appears to result, in part, from disruption of the envelope and/or capsid.

Keywords: CAP37, Azurocidin, Adenovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus, Antimicrobial Peptide

Introduction

CAP37, a cationic antimicrobial protein and inflammatory mediator, plays an important role as part of the innate immune response to microbial pathogens.1 The molecule is expressed as a single copy per haploid genome2 in activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes3 (PMNs), platelets4 and ocular epithelia.5 It was first isolated from the granule fractions of human PMNs and viewed as part of the oxygen-independent killing mechanism of the PMN because of its strong antimicrobial activity.6 CAP37 or its peptide derivatives demonstrate potent in vitro inhibitory activity against a number of Gram-negative bacteria: Pseudomonas aeruginosa7, Escherichia coli,7, 8 Salmonella typhimurium,7 certain Gram-positive bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus,7 Enterococcus faecalis9 and fungi: Candida albicans.7, 8, 10 The antimicrobial domain of the CAP37 protein has been attributed to amino acid residues 20 to 44, and it was proposed that its maximal inhibitory activity may require the formation of intra-molecular disulfide bonds between cysteine residues at positions 26 and 42.7 In the Staphylococcus aureus rabbit keratitis model, the expression of CAP37 was up-regulated during infection in bulbar conjunctiva, corneal epithelial cells, stromal keratocytes, ciliary epithelium, and related limbus and ciliary vascular endothelium.5 In the porcine pneumonia model, the systemic addition of CAP37 to a standard antibiotic regimen reduced elevated body temperature faster than antibiotic treatment alone.11

CAP37 is also an important broad effector molecule of innate immunity that has potent chemotactic activity for monocytes,12, 13 binds heparin and LPS,4, 7, 14 augments leukocyte adhesion to endothelial layers,15 and localizes in atherosclerotic plaques and modulates smooth muscle.16 CAP37 also plays a significant role in the three events associated with corneal wound healing: proliferation, migration, and adhesion. Specifically, CAP37 has been shown to modulate corneal epithelial cell proliferation and migration and up regulate adhesion molecules involved in leukocyte epithelial and epithelial extracellular matrix interactions.17

Recently, the class of antimicrobial peptides and proteins (of which CAP37 is a member) has been shown to have a broader antimicrobial role in the mucosal innate immunity of the eye.18 - 21 Not only do the cationic antimicrobial peptides (cathelicidin [LL-37], human alpha defensin-1, defensin-like chemokines I-TAC and IP-10), collectively play an important role in the ocular defense against potentially pathogenic bacteria and fungi, but some antimicrobial peptides and proteins also demonstrate virus-specific and serotype-dependent antiviral activity against two common ocular viral pathogens: adenovirus, a non-enveloped virus18, 22 and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), an enveloped virus.18, 22 - 24 The goals of the current study were to determine the antiviral activity of the established antibacterial domain of CAP37, to determine the importance of two cysteine residues in this domain, and to investigate the extracellular mechanism of antiviral action.

Methods

Viruses and Cells

The ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) reference strain of Ad3 and clinical isolates of Ad5, Ad8 and Ad19 were grown in A549 monolayers. HSV-1 Mckrae strain was grown in Vero cells. Virus stocks were prepared, titered by standard plaques assay, aliquoted, and frozen at -70°C. The original stock titers (pfu/ml) of the viruses used in this study were: 108 PFU/ml for Ad3, Ad5, Ad19, 107 PFU/ml for HSV-1, and 105 PFU/ml for Ad8. A549 cells, an epithelial-like cell derived from human lung carcinoma cells, (CCL-185, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium with Earle's salts, supplemented with 6% fetal bovine serum, 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B, 100 units/ml penicillin G, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.5 mg/ml gentamicin (Sigma Cell Culture Reagents, St. Louis, MO).

Synthesis of Peptides Based on CAP37 for Structural Activity Relationship Studies

Four 25-amino acid (aa) peptides were used in the current study. The synthesized peptides were based on aa residues 20-44 of the native CAP37 protein (Table 1). The peptides were designated CAP37 A, B, C, D:

Table 1. Amino Acid Sequences of CAP37 and Cathepsin G Peptides.

| Peptide A (CAP3720-44) |

| Asn-Gln-------------Gly-Arg-His-Phe-Cys-Gly-Gly-Ala-Leu-Ile-His-Ala-Arg-Phe-Val-Met-Thr-Ala-Ala-Ser-Cys-Phe-Gln |

| Peptide B (CAP3720-44 ser26) |

| Asn-Gln-------------Gly-Arg-His-Phe-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ala-Leu-Ile-His-Ala-Arg-Phe-Val-Met-Thr-Ala-Ala-Ser-Cys-Phe-Gln |

| Peptide C (CAP3720-44 ser42) |

| Asn-Gln-------------Gly-Arg-His-Phe-Cys-Gly-Gly-Ala-Leu-Ile-His-Ala-Arg-Phe-Val-Met-Thr-Ala-Ala-Ser-Ser-Phe-Gln |

| Peptide D (CAP3720-44 ser26/42) |

| Asn-Gln-------------Gly-Arg-His-Phe-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ala-Leu-Ile-His-Ala-Arg-Phe-Val-Met-Thr-Ala-Ala-Ser-Ser-Phe-Gln |

| *Cathepsin G20-47 Peptide |

| Ile-Gln-Ser-Pro-Ala-Gly-Gln-Ser-Arg-Cys-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu-Val-Arg-Glu-Asp-Phe-Val-Leu-Thr-Ala-Ala-His-Cys-Trp-Gly |

To preserve maximum sequence similarity between the alignment of Cathepsin G Peptide (20-47) and CAP37, the Cathepsin G Peptide (20-47) sequence required the insertion of residues 22-24, thus making the resultant peptide three amino acids longer than the CAP37 peptides8. The 12 identical residues of the CAP3720-44 peptide contained in the Cathepsin G20-47 Peptide, including the cysteine residues at position 26 and 428, are in bold.

CAP3720-44 has two cysteines at positions 26 and 42 (bold) and is synthesized exactly based on the native CAP37 sequence.

CAP3720-44 ser 26 has the cysteine at position 26 replaced by a serine.

CAP3720-44 ser 42 has the cysteine at position 42 replaced by a serine.

CAP3720-44 ser26/42 has both cysteine residues at positions 26 and 42, respectively, replaced by serine residues (Table 1). Previous studies have shown that peptide D (CAP3720-44 ser26/42) is inactive in antibacterial assays and served as an inactive control in the viral inhibition studies. An additional control peptide based on the amino acid sequence of cathepsin G was also included in some studies. Cathepsin G is another neutrophil-derived granule protein, which has strong sequence homology with CAP37 (Table 1). Cathepsin G20-47 peptide and CAP3720-44 are of similar size and have 12 identical residues including the cysteine residues at position 26 and 42.8 Cathepsin G20-47 has previously been shown to have negligible antibacterial activity.8

Peptides were synthesized by tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)/benzyl solid-phase synthesis on an Applied Biosystems peptide synthesizer (model 433A, Foster City, CA) as previously described.8 The peptides were purified by analytical RP-HPLC on a C18 silica SUPER-ODS column (2.1×100 mm, 2 μm particle size, 300 A pore size; TosoHaas, Montgomeryville, PA), using a gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous TFA and monitored at 214 nm. The HPLC fractions were screened by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS). The mass of peptides A, B, C, and D were confirmed at 2723, 2706, 2706, and 2691 respectively. The purified peptides were lyophilized in the form of trifluoroacetate salts. The purity and integrity of the peptides was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS and electrospray ionization MS, and by N-terminal Edman sequencing, using previously described protocols.25 The synthesis of the Cathepsin G20-47 peptide has been previously described.8

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the synthetic peptides on A549 cells was evaluated using the Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS LDH (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) is a stable enzyme normally found in the cytosol of all cells, but rapidly releases into the supernatant upon damage of the plasma membrane. The sensitivity of this colorimetric assay is less than 100 lysed cells per well of a 96-well plate. Cytotoxicity determinations were based on the measurement of LDH released from A549 cells treated with CAP37 peptides A, B, C, and D and the Cathepsin G20-47 peptide at concentrations of 7.5, 0.75 and 0.075 μg/ml for 1, 2, 5, 7, and 9 days. These peptide concentrations (7.5, 0.75 and 0.075 μg/ml) were chosen based on possible residual peptide present in the media following dilutions during viral titrations. The incubation times represent various times to assess cytopathic effect including the time required for the viral titrations of HSV-1 and various adenovirus serotypes. At the end of the incubation period, the percent cytotoxicity was measured for each sample using the formula (experimental value – low control)/(high control – low control) × 100. The low control is delineated as the LDH activity released from the untreated cells and the high control is the maximum releasable LDH activity in the cells. Each assay was run with triplicate samples and controls and the absorbance read at 490 nm on a Molecular Devices Thermomax microplate reader (Sunnyvale, CA). Three independent assays were performed.

Direct Viral Time Kill Assay

Stock solutions of peptides were prepared in non-pyrogenic sterile water for injection and diluted in sterile tryptone-saline (4 g/l tryptone, 5.33 g/l NaCl, pH 5.5, prepared in sterile water for injection). Frozen virus stocks were thawed in a 37°C water bath and diluted in tryptone-saline. Virus and peptide stocks were mixed to produce a final peptide concentration of 500 μg/ml and approximately 104 PFU/ml. Previous studies had demonstrated that the antimicrobial activity of CAP37 was pathogen (e.g. bacterium, fungus) and dose-dependent.8, 9 The concentration chosen for the initial study (500 μg/ml) was based upon the fungal studies performed by one of the authors (HAP) and our previous antiviral studies using a similar cationic antimicrobial peptide (LL-37) that demonstrated differential inhibition of HSV-1 and various adenovirus serotypes.18 Subsequent assays (Increasing Concentration Direct Inhibition Assay and TOTO-1 Assay) were performed with various concentrations of Peptide A (CAP3720-44) ranging from 10 to 750 μg/ml.

The virus/peptide and virus/tryptone-saline Control mixtures were incubated in a 37°C water bath. The time points of incubation were 1 hour and 4 hours and aliquots were removed at 1 and 4 hours for viral titer assay. The aliquots of the virus/peptide mixtures and Control mixtures were diluted in ice cold tissue culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum to stop the activity. CAP37 peptides in vitro are active at pH < 6.0, and the addition of the medium with FBS raises the pH to 7.4 which stops their activity. Furthermore, the active/free peptide concentration is also reduced below its viral inhibitory levels due to a plasma protein binding. The dilutions were plated onto A549 cell monolayers. The plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. Plaques were visible for HSV-1 in 5 days; Ad5 in 7 days; Ad3 and Ad19 in 8-9 days and for Ad8 in 9-10 days. When plaques were visible, the cells were stained with gentian violet and counted using a 25× dissecting microscope. The viral titers were then calculated, and expressed as plaque forming units per milliliter (PFU/ml). The Direct Time Kill Assays were repeated 7 times for all viruses except Ad8 which was done 6 times. The dose-dependent and TOTO-1 assays with Peptide A (CAP3720-44) were performed in duplicate.

TOTO-1 Assay

Capsid integrity for Ad5 and virion envelope/capsid integrity for HSV-1 was determined using the fluorescent, bis-intercalating DNA dye TOTO-1 iodide (T3600 Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as previously described.26, 27 Briefly for Ad5, two peptides and one protein were compared: Peptide A (CAP3720-44), Cathepsin G Peptide (20-47), a similar peptide also derived from neutrophil azurophil granules that served as a negative control28, and the enzyme, Proteinase K that served as a positive control. Only Peptide A (CAP3720-44) was tested with HSV-1. Each peptide/protein was incubated at various concentrations (2 μg/ml - 500 μg/ml) with or without each virus (∼5 × 104 PFU/ml) for 5 hours at 37°C. Equal volumes (75 μl) of reaction mixture were added to 120 nM TOTO-1 in buffer (tryptone-saline, pH 8.0). Samples were placed in optical bottom 96 well plates (Nunc 165305, Rochester, NY) and read with a Biotek Synergy 2 microplate reader (Winoosky, VT) with 485/20 excitation and 516/20 emission filters and a sensitivity setting of 100. Purified adenovirus DNA was used for DNA concentration standards (catalog #15270010, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California 92008). The Ad5 and HSV-1 viruses exhibited negligible fluorescence (data not shown). TOTO-1 fluorescence was determined by subtracting peptide- and virus-derived fluorescence from raw fluorescence readings. All readings were in the linear range and the experiment was repeated at least twice on different days for each virus tested.

Statistical Analysis

The titer data from the direct inactivation assays was Log10 transformed and analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's pair-wise comparisons (Minitab Version 12, Minitab Inc., State College, PA). Significance was established at the p ≤ 0.05 confidence level. In the TOTO-1 assay, the t-test was used to compare the fluorescence of Peptide A (CAP3720-44) to Cathepsin G Peptide at equivalent concentrations for Ad5 using Excel software. Significance was established at the p ≤ 0.05 confidence level.

Results

Cytotoxicity Assay

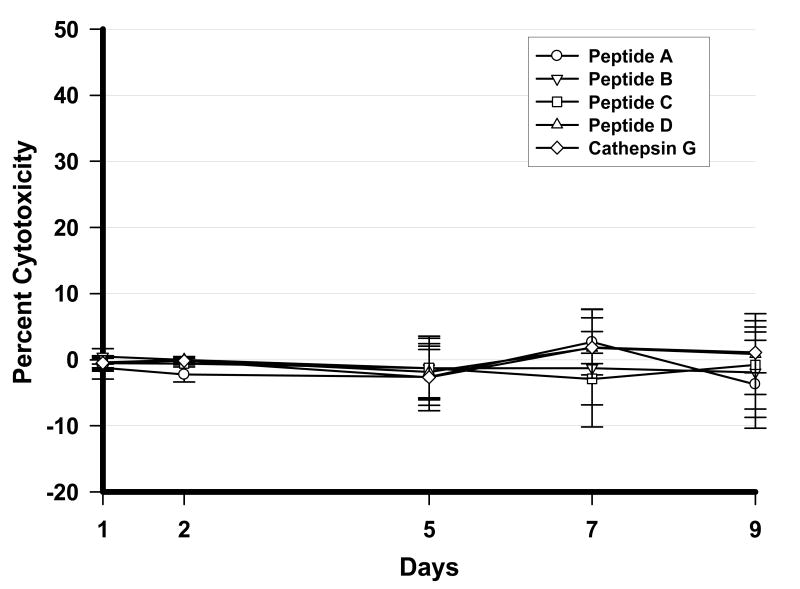

The toxicity produced in A549 cells in response to incubation with each of the synthetic peptides was minimal even at the highest concentration (7.5 μg/ml) of peptide tested (Figure 1). The mean cytotoxicity over the entire incubation time did not exceed 2.9% for any of the test peptides. Therefore, antiviral activity demonstrated by some peptides in subsequent assays in A549 cells cannot be attributed to any confounding direct cell cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity induced in A549 cells following incubation with lower peptide concentrations of 0.75 and 0.075 μg/ml was negligible and the data is not shown.

Figure 1.

Determination of cytotoxicity of CAP37 peptides on A549 cells. Cell cultures containing 6.25 × 103 A549 cells/well in a 96-well plate were treated with 7.5 μg/ml of CAP37 peptides [A (CAP3720-44), B (CAP3720-44 ser26) C (CAP3720-44 ser42) and D (CAP3720-44 ser26/42)] as well as 7.5 μg/ml of a similar Cathepsin G20-47 peptide as a negative control for 1, 2, 5, 7, and 9 days. Cytotoxicity was measured using the colorimetric Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), and the percent cytotoxicity measured based upon LDH release from the damaged cell into the media according to the formula described under Methods. Data presented represents three independent experiments. Overall, the toxicity produced in A549 cells in response to incubation with each of the synthetic peptides was minimal even at the highest concentration (7.5 μg/ml) of peptide tested. The mean cytotoxicity over the entire incubation time did not exceed 2.9% for any of the test peptides. Three independent assays were performed with each assay using triplicate samples.

Direct Time Kill Assay

Significant viral inhibition was demonstrated for Ad3, Ad5 and HSV-1 by most derived CAP37 peptides, while the oculotropic adenovirus serotypes, Ad8 and Ad19, were not inhibited by any CAP37 peptides tested in this assay (Figure 2). Among those viruses inhibited by CAP37-derived peptides, a statistically-significant reduction in viral titers required 4 hours of incubation for Ad3 and HSV-1. In contrast, Ad5 was significantly inhibited at 1 hour by Peptide A (CAP3720-44) (data not shown), but required 4 hours for maximal inhibition.

Figure 2.

Time-kill assay of adenovirus strains, Ad3, Ad5, Ad8, Ad19 and herpes simplex virus type 1 with CAP37 peptides. The reduction in adenoviral serotypes and HSV-1 viral titers compared to the tryptone-saline control line are shown in a Direct Time Kill Assay following 4 hours of in vitro incubation with 500μg/ml of different CAP37-derived peptides. * Denotes a statistically-significant (ANOVA p ≤ 0.05) reduction in viral titers compared with the tryptone-saline control line. All peptides were inhibitory for Ad3 and HSV-1. ** Denotes that for Ad5, Peptide A (CAP3720-44) was significantly more inhibitory than Peptide B (CAP3720-44 ser 26), but both demonstrated significant inhibition relative to the tryptone-saline control (ANOVA p ≤ 0.05). None of the peptides tested were inhibitory for the oculotropic viruses, Ad8 and Ad19. The Direct Time Kill Assays were repeated 7 times for all viruses except Ad8 which was done 6 times.

For Ad3, all peptides tested [A (CAP3720-44), B (CAP3720-44 ser 26), C (CAP3720-44 ser 42), and D (CAP3720-44 ser 26/42)] demonstrated a statistically-significant reduction in viral titers compared to the tryptone-saline control (ANOVA, p = 0.008). There were no differences among the peptides (Fisher's Pair-wise comparison). The same inhibitory results were demonstrated for all peptides against HSV-1 (ANOVA, p = 0.028), except that the magnitude of inhibition was greater for HSV-1 (range 1.49 - 1.91 log10 reduction) than for Ad3 (range 0.73 - 1.28 log10 reduction). In contrast, for Ad5, the importance of the cysteine residues was clearly demonstrated. Only Peptides A (CAP3720-44) and B (CAP3720-44 ser 26) demonstrated significantly greater inhibitory activity than the tryptone-saline control (ANOVA, p < 0.001), and Peptide A (CAP3720-44) was significantly more inhibitory than Peptide B (CAP3720-44 ser 26). In fact, Peptide A (CAP3720-44) demonstrated the greatest inhibitory activity against Ad5 (2.21 log10 reduction) of all peptides and viruses tested in this assay.

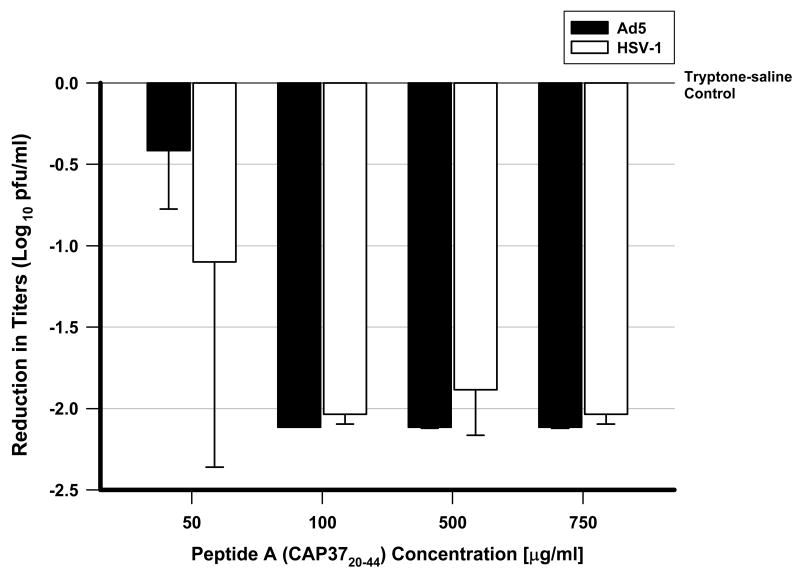

Direct Inhibition Assay at Different Peptide Concentrations

Compared to the tryptone-saline Control line (Figure 3), Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of both Ad 5 and HSV-1, up to a concentration of 100 μg/ml, following 4 hours of incubation. Above the concentration of 100 μg/ml of Peptide A (CAP 3720-44), the inhibitory effect remained stable (∼ 2 log reductions) for both viruses.

Figure 3.

Dose-response inhibition of Ad5 and HSV-1 by Peptide A (CAP3720-44). Peptide A (CAP3720-44) directly inhibits Ad5 (solid bar) and HSV-1 (open bar) in an Increasing Concentration Direct Inhibition Assay following 4 hours of incubation. This figure is constructed as the log reduction of viral titers for Ad5 and HSV-1 at different concentrations in which each bar represents the mean difference of the resultant titers between the peptide-treated group at that concentration and its respective negative tryptone-saline control. Therefore the respective negative controls for each concentration of Peptide A (CAP3720-44) are represented by the top line labeled Tryptone-saline Control at the 0 level on the y axis. An increasing antiviral effect is demonstrated for Peptide A (CAP3720-44) as the concentration increases from 0 to 100 μg/ml. Above 100 μg/ml, the antiviral effect is constant. The dose-dependent assay with Peptide A (CAP3720-44) was performed in triplicate.

Effect of CAP37 on Virus Capsid Integrity Using the TOTO-1 Assay

TOTO-1 is a commercially available fluorescent DNA-intercalating dye that has previously been used to assess adenovirus capsid integrity and disassembly.26, 27 TOTO-1 does not have access to DNA when capsids are intact, but can intercalate with the DNA when the integrity of the capsid is compromised. The extent of virus capsid disruption can be measured because TOTO-1 fluorescence increases 100-fold upon binding with DNA.

In the current study, a reproducible peptide dose-dependent increase in TOTO-1 fluorescence was observed for Ad5 with the most rapid uptake of fluorescence (slope of curve) between concentrations of 10 and 100 μg/ml Peptide A (CAP 3720-44). At a Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) concentration of 500 μg/ml, there was a 65-85% increase in fluorescence. The observed differences in fluorescence between Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) and the negative control, Cathepsin G20-47 peptide were statistically-significant at concentrations of 100 μg/ml (p = 0.034) and 500 μg/ml (p = 0.032) (t-test).

Overall there was minimal fluorescence for the negative control, Cathepsin G20-47 peptide. However, while there was a wide standard deviation at 10μg/ml, there were no statistically-significant differences in TOTO-1 fluorescence for Cathepsin G20-47 peptide when comparing 10 μg/ml with 100 μg/ml (p=0.144) and 500 μg/ml (p=0.147) (t-test). For HSV-1, the most rapid uptake of fluorescence (slope of curve) occurred between concentrations of 100 and 500 μg/ml Peptide A (CAP 3720-44).

The results appear to support a model of specific capsid disruption by increasing concentrations of peptide A (CAP3720-44) for Ad5. Cathepsin G20-47 peptide is a similar-sized peptide that is also derived from neutrophil azurophil granules28 but had no disruptive effect on Ad5 capsid integrity. Cathepsin G20-47 peptide has previously been shown to have negligible antibacterial activity.8 Proteinase K, an enzyme known to disrupt viral capsids, served as a positive control in this experiment at concentrations of 2, 20 and 200 μg/ml. Additional negative controls of TOTO-1 in buffer solution and virus without the TOTO-1 dye were also associated with negligible fluorescence.

Discussion

The goals of the current study were to determine the antiviral activity of the established antibacterial domain of CAP37, to determine the importance of two cysteine residues in this domain, and to investigate the extracellular mechanism of antiviral action. We first demonstrated that none of the peptides' attributed antiviral activity was due to a possible confounding direct cytotoxicity in A549 cells (Figure 1). We determined that the cysteine residues required for full levels of antibacterial function are not necessary for most of its antiviral activity. Previous studies with the same CAP37-derived peptides reported potent in vitro inhibitory activity against a number of Gram-negative bacteria: Pseudomonas aeruginosa,7 Escherichia coli,7, 8 Salmonella typhimurium7, certain Gram-positive bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus,7 Enterococcus faecalis,9 and fungi: Candida albicans.7, 8,10 The antimicrobial domain of the CAP37 protein was attributed to amino acid residues 20 to 44, and it was proposed that its maximal inhibitory activity may require the formation of intra-molecular disulfide bonds between cysteine residues at positions 26 and 42.7 In the current study, we characterized the antiviral activity of the established antibacterial domain with the same peptides and found the antiviral activity in the domain to be more complex. The presence of a disulfide bond was not required to explain the observed results; namely, that inhibition by CAP37-derived peptides was different for different viruses (Ad5 versus HSV-1) and different serotypes of human adenoviruses (Ad3, Ad5 versus Ad8, Ad19). Since we observed different antiviral inhibitory activity among the CAP37-derived peptides, it suggests that the cysteine to serine variations may alter more than just disulfide bond status, and that observed differences in antiviral activity may be due to other mechanisms (e.g altered peptide folding/tertiary structures). The observed differences in results between bacteria and viruses are not surprising given the different attributed mechanisms of action of antimicrobial peptides against bacteria (increased poration of lipid membranes)29, 30 and viruses (direct inactivation and/or blockage of virus entry).31, 32

An important question raised by the current study is the relationship between the in vitro antiviral activity demonstrated by CAP37-derived peptides at the concentrations tested [18.4 μM (50 μg/ml) to 275 μM (750 μg/ml)] and the actual antimicrobial role they may play during ocular viral infection. The expected physiological levels of CAP37 will vary depending upon the state of the tissue. The amount of CAP37 present in the human neutrophil ranges from 11 fg to 1 pg/neutrophil.12, 33, 34 Depending on the number of neutrophils present in the tissue, the physiological or normal range of CAP37 could reach levels of 5 μg/ml of blood (0.135 μM).34 However, these levels are likely to be elevated greatly in inflammatory and disease states following the attraction of large numbers of neutrophils but the actual levels are currently unknown. Theoretically, much higher local concentrations could also be achieved within intracellular endosomes or vacuoles following neutrophil release of their antimicrobial peptides/proteins into these small volume structures.

The current study expands the antimicrobial activity of the multi-functional protein CAP37 to include antiviral activity in the established antibacterial domain that is both virus and Ad serotype-specific. Furthermore, we observed in vitro that CAP37 effectively inhibited HSV-1 and the respiratory adenovirus serotypes that also infect the eye; Ad3 (Species B) and Ad5 (Species C), but had no effect on the Species D oculotropic serotypes Ad8 and Ad19 that are specific and unique to the eye.

The current results for CAP37 are similar to those reported for other antimicrobial peptides expressed on the ocular surface [cathelicidin, human defensins (alpha 1, beta 1, and beta 2), and defensin-like chemokines (IP-10, I-TAC)18, 22 that demonstrated variable antiviral activity that was often virus-specific and serotype-dependent. Overall, these results support an emerging view that the complex, integrated system of innate immunity on the ocular surface is characterized, in part, by multi-functional peptides and proteins. With respect to antimicrobial function, no single antimicrobial peptide inhibits all pathogenic micro-organisms: bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Nor does any single antimicrobial peptide inhibit all ocular viruses.18 - 22, 35

Another goal of the current study was to study the extracellular mechanism of antiviral action. The TOTO-1 assay has been used in other studies to demonstrate disruption of the adenovirus capsid.26, 27 In the Direct Inhibition Assay at different peptide concentrations of Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) (Figure 3), we found that for both Ad5 and HSV-1 the initial inhibitory concentrations of Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) (50 μg/ml) increased to a maximal inhibitory effect at 100 μg/ml (Figure 2). Above 100 μg/ml, no additional inhibition was demonstrated for either Ad5 or HSV-1. For Ad5, a non-enveloped virus, a rapid increase in fluorescence from 10 μg/ml to 100 μg/ml in the TOTO-1 assay may represent incremental capsid disruption (Figure 4) up to a threshold point of an irreversibly damaged virion incapable of cell uptake and replication. Increasing fluorescence observed at a higher concentration of peptide (500 μg/ml) for Ad5 may represent additional capsid breakdown and DNA intercalation of dye. However, as the threshold for virion viability had already been exceeded at 100 μg/ml, there is no additional in vitro viral inhibition (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Demonstration of Ad5 and HSV-1 capsid disruption by CAP37 peptide A using the TOTO-1 assay. These data display increasing fluorescence representing access of a DNA-intercalating fluorescent dye (TOTO-1) into viral DNA. Compared to Cathepsin G20-47 peptide, another neutrophil azurophil granule-derived, similar-sized peptide28, the results support a model of specific capsid disruption of Ad5 by Peptide A (CAP3720-44) at concentrations of 100 μg/ml (p=0.034) and 500 μg/ml (p=0.032). For HSV-1, increasing concentrations of Peptide A (CAP3720-44) from 100 to 500 μg/ml was also associated with increasing fluorescence. Proteinase K, an enzyme known to disrupt viral capsids, served as a positive control in these experiments at concentrations of 2, 20 and 200 μg/ml. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The TOTO-1 assay with Peptide A (CAP3720-44) was performed in duplicate.

The different results for HSV-1 may be based upon differences in virion structure. The reason for no increase in fluorescence in the TOTO-1 assay for HSV-1 between 10 and 100 μg/ml is unknown but may be related to the presence of the lipid membrane that surrounds the capsid which impedes the access of the Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) to the nucleocapsid. For HSV-1 the observed limited antiviral effect at 50 μg/ml by Peptide A (CAP 3720-44) (Figure 3) may be explain by another mechanism based on the inhibition of cell receptor binding and viral uptake into the cell. At a concentration of 100 μg/ml and higher, the mechanism for HSV-1 could be based upon complete destruction of the lipid membrane and capsid disruption as previously described for Ad5, a non-enveloped virus. This data is consistent with the hypothesis that CAP37 inhibits extracellular virus by compromising the integrity of the capsid for Ad5 and the envelope/capsid for HSV-1.

Finally, relative to proteinase K, the activity of the peptides is substantially lower even at higher concentrations suggesting that they are not very efficient at increasing dye access. Therefore, our results do not preclude the possibility that the peptides may also work by an additional unknown inhibitory mechanism before acting on the capsid to increase dye access.

Acknowledgments

Support: NIH Grant EY08227 (YJG), NIH Core Grant EY08098 (OVSRC), NIH Grant AI28018 (HAP), NIH Grant EY015534 (HAP), The Eye & Ear Foundation of Pittsburgh, Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology

References

- 1.Pereira HA. Novel therapies based on cationic antimicrobial peptides. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:229–234. doi: 10.2174/138920106777950771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linzmeier RM, Ganz T. Copy number polymorphisms are not a common feature of innate immune genes. Genomics. 2006;88:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson M, Sørensen OE, Mörgelin M, Weineisen M, Sjöbring U, Herwald H. Activation of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils by streptolysin O from Streptococcus pyogenes leads to the release of proinflammatory mediators. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:982–90. doi: 10.1160/TH05-08-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flodgaard H, Ostergaard E, Bayne S, et al. Covalent structure of two novel neutrophil leucocyte-derived proteins of porcine and human origin. Neutrophil elastase homologues with strong monocyte and fibroblast chemotactic activities. Eur J Biochem. 1991;197:535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruan X, Chodosh J, Callegan MC, et al. Corneal expression of the inflammatory mediator CAP37. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1414–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafer WM, Martin LE, Spitznagel JK. Cationic antimicrobial proteins isolated from human neutrophil granulocytes in the presence of diisopropyl fluorophosphate. Infect Immun. 1984;45:29–35. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.29-35.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campanelli D, Detmers PA, Nathan CF, Gabay JE. Azurocidin and a homologous serine protease from neutrophils. Differential antimicrobial and proteolytic properties. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:904–915. doi: 10.1172/JCI114518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira HA, Erdem I, Pohl J, Spitznagel JK. Synthetic bactericidal peptide based on CAP37: a 37-kDa human neutrophil granule-associated cationic antimicrobial protein chemotactic for monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4733–4737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almeida RP, Vanet A, Witko-Sarsat V, et al. Azurocidin, a natural antibiotic from human neutrophils: expression, antimicrobial activity, and secretion. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;7:355–366. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe D, Cukierman T, Gabay JE. Basic residues in azurocidin/HBP contribute to both heparin binding and antimicrobial activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27477–27488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luritzen B, Lykkesfeldt J, Djurup R, Flodgaard H, Svendsen O. Effects of heparin-binding protein (CAP37/azurocidin) in a porcine model of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae-induced pneumonia. Pharmacol Res. 2005;51:509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira HA, Shafer WM, Pohl J, Martin LE, Spitznagel JK. CAP37, a human neutrophil-derived chemotactic factor with monocyte specific activity. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1468–1476. doi: 10.1172/JCI114593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuyama Y, Cho JH, Nakajima Y, et al. Binding between azurocidin and calreticulin: its involvement in the activation of peripheral monocytes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2004;135:171–177. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brackett DJ, Lerner MR, Lacquement MA, He R, Pereira HA. A synthetic lipopolysaccharide-binding peptide based on the neutrophil-derived protein CAP37 prevents endotoxin-induced responses in conscious rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2803–2811. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2803-2811.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee TD, Gonzalez ML, Kumar P, Grammas P, Pereira HA. CAP37, a neutrophil-derived inflammatory mediator, augments leukocyte adhesion to endothelial monolayers. Microvasc Res. 2003;66:38–48. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(03)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez ML, Ruan X, Kumar P, Grammas P, Pereira HA. Functional modulation of smooth muscle cells by the inflammatory mediator CAP37. Microvasc Res. 2004;67:168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira HA, Ruan X, Gonzalez ML, Tsyshevskaya-Hoover I, Chodosh J. Modulation of corneal epithelial cell functions by the neutrophil-derived inflammatory mediator CAP37. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4284–4292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon YJ, Huang LC, Romanowski EG, et al. Human cathelicidin (LL-37), a multifunctional peptide, is expressed by ocular surface epithelia and has potent antibacterial and antiviral activity. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:385–394. doi: 10.1080/02713680590934111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntosh RS, Cade JE, Al-Abed M, et al. The spectrum of antimicrobial peptide expression at the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1379–1385. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikeda A, Sakimoto T, Shoji M, Sawa J. Expression of alpha- and beta-defensins in human ocular surface tissue. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0163-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDermott AM. Defensins and other antimicrobial peptides at the ocular surface. The Ocular Surface. 2004;2:229–247. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey SA, Romanowski EG, Yates KA, Gordon YJ. Adenovirus-directed ocular innate immunity: the role of conjunctival defensin-like chemokines (IP-10, I-TAC) and phagocytic human defensin-alpha. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3657–3665. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenssen H, Andersen JH, Mantzilas D, Gutteberg TJ. A wide range of medium-sized, highly cationic, alpha-helical peptides show antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus. Antiviral Res. 2004;64:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha S, Cheshenko N, Lehrer RI, Herold BC. NP-1, a rabbit alpha-defensin, prevents the entry and intercellular spread of herpes simplex virus type 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:494–500. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.494-500.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubalek F, Edmondson DE, Pohl J. Synthesis and characterization of a collagen model. dO-phosphohydroxylysine-containing peptide. Anal Biochem. 2002;306:124–134. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rexroad J, Wiethoff CM, Green AP, Kierstead TD, Scott MO, Middaugh CR. Structural stability of adenovirus type 5. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:665–67. doi: 10.1002/jps.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR. Adenovirus Protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J Virol. 2005;79:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.1992-2000.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pham CTN. Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nature Reviews/Immunology. 2006;6:541–550. doi: 10.1038/nri1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shai Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002;66:236–248. doi: 10.1002/bip.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bultmann HC, Brandt CR. Peptides containing membrane-transiting motifs inhibit virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36018–36023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinones-Mateu ME, Lederman MM, Feng Z, et al. Human epithelial beta-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. Aids. 2003;17:F39–48. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitznagel JK. Antibiotic proteins of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1381–1386. doi: 10.1172/JCI114851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostergaard E, Flodgaard H. A neutrophil-derived proteolytic inactive elastase homologue (hHBP) mediates reversible contraction of fibroblasts and endothelial cell monolayers and stimulates monocyte survival and thrombospondin secretion. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:316–323. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.4.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes RJ, McElveen JE, Dua HS, Tighe PJ, Liversidge J. Expression of human beta-defensins in intraocular tissues. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3026–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]