Summary

Regulated production and elimination of the signaling lipids phosphatidic acid (PA), diacylglycerol (DAG), and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2) creates a complex and interconnected signaling network that modulates a wide variety of eukaryotic cell biological events. PA production at the plasma membrane and on trafficking membrane organelles by classical Phospholipase D (PLD) through the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine (PC) has been studied widely. In this chapter, we review a newly identified, non-canonical member of the PLD superfamily, MitoPLD, which localizes to the mitochondrial surface and plays a role in mitochondrial fusion via the hydrolysis of cardiolipin (CL) to generate PA. The role of PA in facilitating the mitochondrial fusion event carried out by proteins known as Mitofusins is intriguing in light of the role classic PLD-generated PA plays in facilitating SNARE-mediated fusion of secretory membrane vesicles into the plasma membrane. In addition, however, PA on the mitochondrial surface may also trigger a signaling cascade that elevates DAG, leading to downstream events that affect mitochondrial fission and energy production. PA production on the mitochondrial surface may also stimulate local production of PI4,5P2 to facilitate mitochondrial fission and subcellular trafficking or facilitate Ca2+ influx.

Keywords: phosphatidic acid, MitoPLD, mitochondrial fusion, fission, insulin signaling, calcium homeostasis

1. Introduction

The lipid second messenger phosphatidic acid (PA) plays pleiotropic roles in the regulation of a variety of cell functions including receptor signaling, membrane vesicle trafficking, and cytoskeletal organization [1–4]. Although the bulk of cellular PA is synthesized via acylation pathways, PA is also produced via other types of lipid-modifying enzymes on a much faster time scale, and this latter pathway serves to generate PA that functions in a signaling context in many types of cell biological processes. There are two major families of enzymes involved in generation of PA during signaling events - Phospholipase D (PLD1 and PLD2 in mammals), classical members of which hydrolyze phosphatidylcholine (PC) to yield choline and PA, and diacylglycerol kinases (DAGKs), which generate PA by phosphorylating DAG [this issue, see 5]. Conversely, PA can be converted into DAG through dephosphorylation, via the action of Type I or Type II phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolases [this issue, see 6]. Finally, one of the actions undertaken by PLD-generated PA is to stimulate the recruitment and activation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5 Kinases [PIP5Ks, this issue, see 7] to generate Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI4,5P2), which can be hydrolyzed by Phospholipase C (PLC) as another way to generate DAG (Fig. 1). Thus, the lipids PA, DAG, and PI4,5P2 form a complex and interconnected signaling network that regulates a diverse set of cell biological pathways.

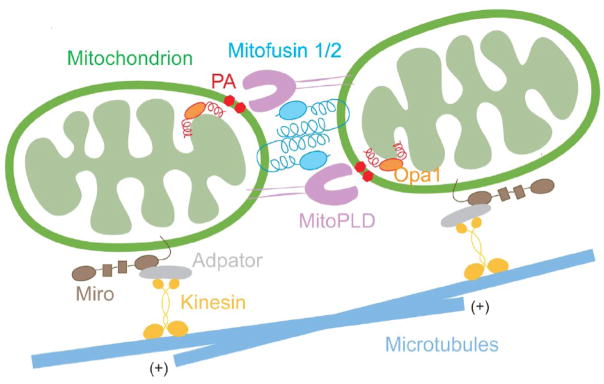

Figure 1. Signaling Lipids.

Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and Cardiolipin (CL), which are major phospholipids in the plasma membrane and mitochondria, respectively, can be converted by members of the Phospholipase D superfamily into PA, which in turn can be used to generate DAG via action of PA Phosphatase. PA also stimulates the enzyme Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-Kinase to generate PI4,5P2, which can be converted to DAG via the action of Phospholipase C. Several of these actions are reversible, for example conversion of DAG back to PA by DAG Kinase.

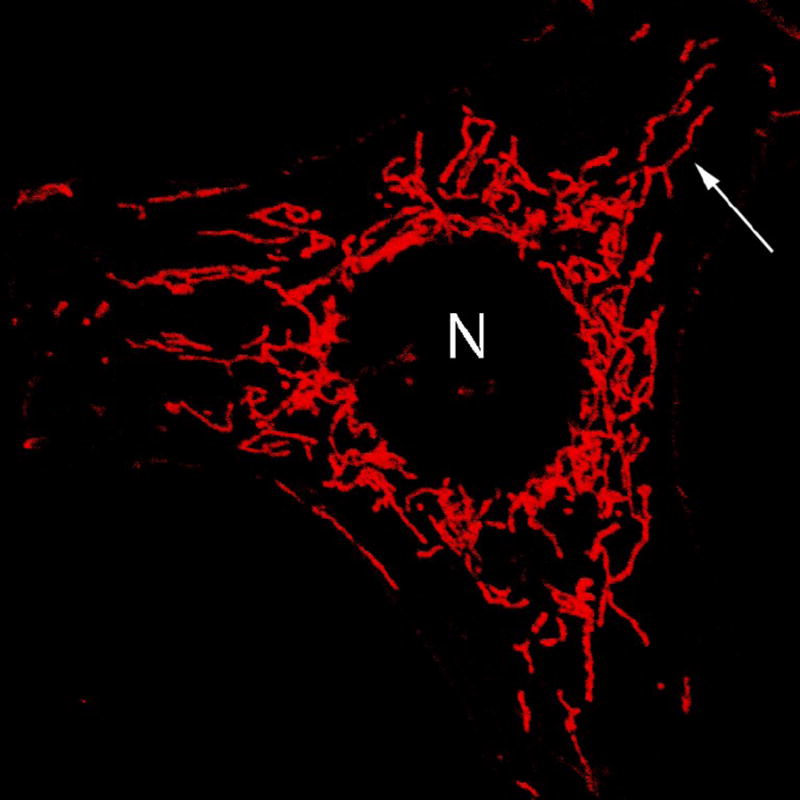

While there have been hundreds of reports that have described PLD, PIP5K, and DAGK activities on the plasma membrane, secretory apparatus, nuclear envelope, and trafficking membrane vesicles, relatively little is known regarding lipid signaling at the surface of mitochondria. Mitochondria are stereotypically viewed as kidney-shaped organelles scattered throughout the cytosol, as a result of the images obtained from electron microscopy thin sections that are frequently presented in textbooks and reviews. In fact, however, many of these images are actually presenting oblique slices of long mitochondrial tubules that are part of a network-like structure that extends from the perinuclear region to as far as the edge of the cell (Fig. 2). Mitochondria are constantly undergoing fission and fusion, and their morphology is ultimately regulated by the fusion to fission balance, which can vary in different cell types [8]. The balance is dynamically controlled – mitochondrial tubules undergo massive fission during cytokinesis and then rapidly fuse together again in the synthesis phase of the cell cycle [9, 10]. Insulin and other growth factor stimulation increases the fusion to fission balance [11, 12], which may reflect the fact that larger mitochondria are more efficient at generating energy. In contrast, induction of apoptosis triggers mitochondrial fragmentation by increasing the rate of fission, although the fission in itself does not cause cell death [13]. Directed subcellular localization of mitochondria is also important to ensure that they function properly in the context of generating energy where it is needed in the cell, in particular for cells with localized high energy requirements, such as neurons, at axonal sites of synaptic transmission, which are distant from the cell body [14, 15], and lymphocytes, at regions of myosin dynamics during chemotaxis [16]. In pancreatic acinar cells, mitochondria form a belt surrounding the granule-rich region to confine Ca2+ signaling within the apical pole [17]. Subcellular mitochondrial trafficking is affected by mitochondrial morphology [18], and genetic mutations that lead to fission and fusion dysfunction not only cause mitochondrial aggregation or fragmentation in cultured cells, but cause diseases such as type 2A Charcot-Marie-Tooth, an inherited peripheral neuropathy [19, 20] characterized by blunted synaptic transmission and axonal die-back from their distal target sites.

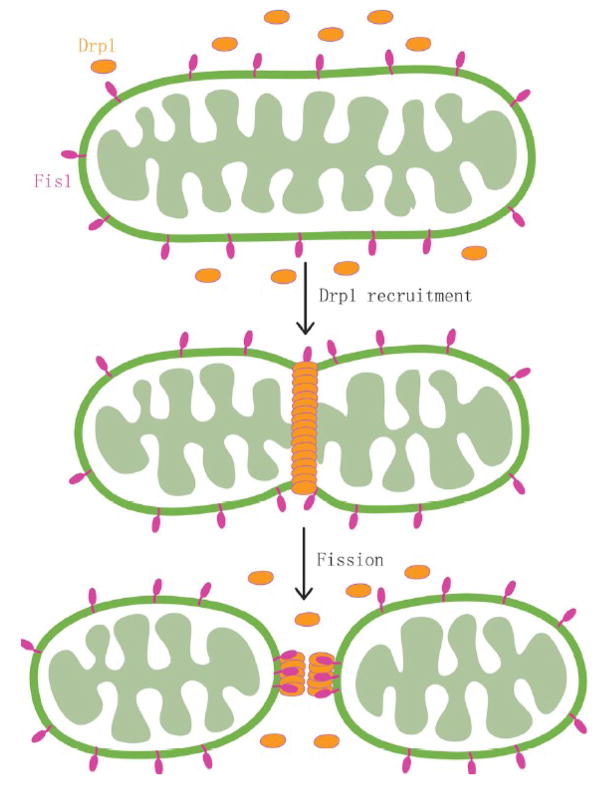

Figure 2. Tubular mitochondrial morphology.

HeLa cell expressing mitochondrially-targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) demonstrates tubular organization of mitochondria. N, nucleus. Arrow, typical branched, tubular mitochondria.

Some of the proteins important for mitochondrial fusion and fission have been identified, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. The proteins tend to function specifically for mitochondria, but in a manner analogous to how similar types of proteins function in fusion and fission of cytosolic membrane vesicles as they bud from and fuse into subcellular membrane compartments. For example, the proteins called Mitofusins (Mfns) that mediate mitochondrial fusion perform a function similar to that undertaken by SNARE complex proteins for other types of membrane fusion [21, 22], although there are distinct aspects to the fusion mechanism [8, 23]. Similarly, fission is mediated by a dynamin-related protein, Drp1 [10, 24], which functions analogously to dynamin during the process of endocytosis. Mitochondria translocate through the cell via microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton, using both unique tethering proteins and universal components of the cytoskeleton [18, 25], and this movement is promoted by the mitochondrial Rho GTPases (Miro 1 and Miro 2) [26, 27]. As described in other chapters in this issue, PA, DAG, and PI4,5P2 regulate numerous aspects of cytosolic membrane vesicle fusion, fission, and trafficking through effects on the recruitment and function of protein partners. Similar types of roles for lipid signaling on the surface of mitochondria are just beginning to be reported and appreciated [28].

Figure 3. Mitochondrial fusion.

Model for mitochondrial fusion and trafficking. During fusion, the mitochondrial outer membrane protein Mitofusin 1 and 2 tether adjacent mitochondria through their coiled-coil domains, bringing the MitoPLD dimer into close contact with its substrate, cardiolipin, at the opposing mitochondrial membrane. This generates PA, which facilitates outer membrane fusion. Inner membrane fusion is facilitated by an inter-membrane protein, Opa1. Mitochondrial movement along microtubules is promoted by the interaction of an outer membrane protein, Miro, with kinesin, through an adaptor protein.

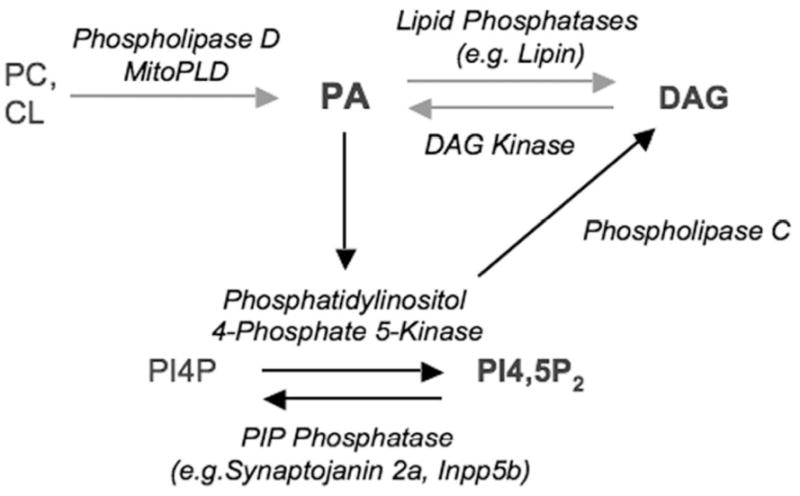

Figure 4. Mitochondrial fission.

Model for mitochondrial fission. The fission protein, Fis1, resides in the mitochondrial outer membrane and recruits dynamin-like protein (Drp1) during mitochondrial fission. Drp1 assembles around the fission site to create membrane constriction.

Reports of PLD activity in association with mitochondria have been relatively sparse. A PLD activity with unique biochemical properties (metal or calcium ion-stimulated, phosphatidylethanolamine-preferring) was described more than a decade ago [29], but has never been cloned. The classic isoform PLD1 has also been reported as being co-enriched with mitochondrial fractions of cell lysates prepared from Alzheimer’s disease patients [30], although this may reflect association of PLD1 with amyloid precursor protein (APP) [31], rather than specific interaction with the mitochondria per se, and other organelles significantly co-fractionate in those fractions as well (e.g. endoplasmic reticulum and nuclei). More recently, PLD1 overexpression was demonstrated to trigger translocation of a DAG-binding protein, Protein Kinase D1 (PDK1), to the mitochondria [32]. In addition, it was shown that mitochondrial stress results in increases in DAG levels on the mitochondrial surface. The PLD1 connection is intriguing and could ensue from several possible mechanisms. PLD1 overexpression could initiate mitochondrial stress, causing increases in DAG and subsequent PKD1 translocation. Alternately, PA produced by PLD1 at the Golgi or in the ER could be converted to DAG by a PA Phosphatase such as Lipin 1 and transferred to mitochondria through Mitochondrial-Associated ER Membranes (MAM) [33]. Finally, PLD1 could produce the PA at the mitochondrial surface, although there is no evidence for PLD1 localization or PLD1-generated PA or DAG production there at present.

As described in further detail below, our research group has described a divergent and intriguing PLD superfamily member, denoted MitoPLD, which anchors into the cytoplasmic surface of mitochondria and operates there in trans on the surface of other mitochondria brought into close proximity during the process of fusion [23]. Possessing a typical HKD catalytic motif, MitoPLD produces PA similar to classical PLDs, although it does so using a mitochondrial-specific lipid, cardiolipin (CL), instead of PC, as the substrate. A role for PA production on the mitochondrial surface in mitochondrial fusion has been identified; however, as is the case for classic PLD isoforms in other membrane compartments, there may be additional functions for MitoPLD as well, making the study of PA signaling on the mitochondrial surface a topic of emerging interest.

2. A PA production pathway on the mitochondrial surface regulates mitochondrial fusion

A BLAST search of the human genome for additional members of the PLD superfamily uncovered a protein with a single HKD half-catalytic site, later named MitoPLD, which was predicted to localize to mitochondria based on an N-terminal leader sequence [23]. There are at least half a dozen currently uncharacterized proteins that encode HKD (PLDc) domains in the mammalian genome, although many are quite divergent and it is not clear whether they retain enzymatic capability. Sequence analysis revealed that MitoPLD is more similar to ancestral prokaryotic PLD superfamily members such as Nuc, which is a DNA endonuclease, and cardiolipin synthase, than to classical mammalian PLD family members [23]. Although seemingly odd, similar types of conservation relationships (greater similarity to prokaryotic superfamily members than to other mammalian ones) are found for many other proteins that localize to mitochondria, potentially reflecting the fact that mitochondria arose from eukaryotic capture of a prokaryotic organism, and although many of the genes initially encoded by the mitochondrial genome have since relocated to the eukaryotic genome, they still retain evolutionary signatures of their origin.

Virtually all PLDs, prokaryotic and eukaryotic, encode two half-catalytic HKD domains [34] that fold together to form the functional enzymatic unit [this issue, 35]. The sole prior exception to this was the protein Nuc, which encodes only one half-catalytic site and dimerizes to achieve a functional enzymatic site [36]. Split-Venus complementation and co-immunoprecipitation approaches were thus employed to demonstrate that MitoPLD also dimerizes to generate an active enzymatic complex. Surprisingly though, MitoPLD displayed neither endonuclease nor CL synthase activity, but rather the reverse of CL synthase activity, i.e. hydrolysis of CL to generate PA. Even more surprisingly, protease surface digestion of intact mitochondria revealed MitoPLD to be an outer membrane-anchored protein with its amino-terminus serving as a transmembrane segment and the carboxy-catalytic-terminus protruding into the cytosol. Since cardiolipin is primarily an inner membrane-specific lipid, this physical arrangement raised issues of how MitoPLD could possibly access its substrate. However, the outer mitochondrial membrane does contain 10–20% of the total mitochondrial cardiolipin [37, 38], in particular at sites at which the outer and inner membranes come into contact [37], which are thought to represent locations at which mitochondrial fusion takes place. Intriguingly, this also suggests that MitoPLD most likely generates PA at the contact sites and functions there.

With respect to function, manipulation of MitoPLD expression was found to phenocopy gain and loss of proteins involved in mitochondrial fusion. Three proteins were previously known to mediate mitochondrial fusion: Mitofusin 1 (Mfn1) and Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) anchor in the outer membrane and tether adjacent mitochondria together via SNARE complex-like coiled-coil domains to promote outer membrane fusion [21]. Another protein, OPA1, is located in the inner membrane and intermembrane space and mediates inner membrane fusion [20]. Overexpression of MitoPLD caused aggregation of mitochondria [23], similar to overexpression of Mfn1 [21], whereas knock-down of MitoPLD or expression of a MitoPLD dominant-negative isoform led to mitochondrial fragmentation [23], similar to what is observed for cells lacking Mfn proteins [21], indicating that MitoPLD functions as a vital component of the fusion machinery by generating PA. How PA facilitates mitochondrial fusion remains to be determined, but the requirement for PA is surprisingly similar to its requirement in the fusion of secretory vesicles into the plasma membrane through SNARE-complex mediated action [39–42].

In both cases, the actual fusion event is mediated by protein machinery that triggers complex formation of coiled-coil domains in trans. For SNARE complex proteins, in the classical setting of fusion of secretory vesicles into the plasma membrane, the vesicles contain a v-SNARE protein, and the target membrane a t-SNARE protein. Each SNARE has a coiled-coil domain. The v-SNARE and t-SNARE proteins align their coiled-coil domains in a head-to-head orientation, which, through interacting, pull the membrane vesicle into contact with the plasma membrane to initiate the fusion reaction. Precisely how PA facilitates the fusion event is not understood, although a direct effect on the SNARE mechanism has been demonstrated [41], which may involve recruitment of the v-SNARE towards the plasma membrane through positively-charged amino acids in the v-SNARE interacting with PA on the plasma membrane. The Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion reaction also involves dimerization of coiled-coil domains, but there are differences. In this case, a homodimer is formed, since each mitochondrial surface expresses Mfn, and the coiled-coil domains align head-to-tail, which would be a non-functional orientation for classic SNARE proteins. How Mfn causes the fusion process to proceed beyond this point and what role PA plays in it is unknown, save that the progression of fusion also requires the activity of the Mfn GTPase. Nonetheless, the two distinct protein fusion machineries are facilitated by local PA production, suggesting that PA may play a common role in the fusion events.

Two questions that arose from this study were whether the fusion event is regulated by PA production, or by depletion of the substrate, CL, and would MitoPLD-triggered CL depletion affect other processes, since CL is important for efficient oxidative phosphorylation [43, 44] and mediates apoptotic pathways [45]. As reported [23], no obvious perturbations in normal cell function were observed even with substantial MitoPLD overexpression. The cells were viable and proliferated normally. Cytochrome c was still localized to the mitochondria and MitoPLD overexpression didn’t alter mitochondrial membrane potential. This agrees with another study on CL synthase RNAi knockdown that reported that cells with only 25% of the normal amount of CL can function properly in the absence of apoptotic signals [46]. MitoPLD is not an abundant protein; hence its effects on total CL are unlikely to be significant during fusion events, although substantial changes in localized microregions can not be ruled out.

The findings raise many questions. Does MitoPLD-generated PA recruit signaling proteins, as do PLD1 and PLD2 at other membrane surfaces? How is PA signaling terminated at the mitochondrial surface? Are other lipid signaling pathways activated as a consequence of MitoPLD-generated PA production, and what processes might they impact on?

3. PA signaling pathways on the mitochondrial surface

3.1 PA signaling and diabetes

As a potent bioactive signaling lipid, PA generated on the plasma membrane by classic PLD isoforms is well-known to be turned over rapidly to terminate PA-mediated signaling events through the action of PA phosphatases (PAPs), which convert the PA to DAG [this issue, 6]. Interestingly, several studies have reported that there is a dynamic pool of DAG generated on the mitochondrial surface that can be observed using fluorescent sensors, in particular when DAG-metabolizing enzymes are blocked [47, 48] or under conditions of mitochondrial stress [32]. In the latter case, the DAG has been shown to recruit Protein Kinase D1 to mitochondria. The mechanism responsible for this DAG production and its physiological significance have not been established, but there are several intriguing possibilities. The first is suggested by studies on insulin signaling in muscle and liver cells. Among many other actions, insulin stimulates shifts in mitochondrial energy production via the activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which is located in the mitochondrial interior. PDH is activated as a consequence of translocation of protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) from the cytosol to the mitochondria [49]. However, it is not currently understood how PKCδ at the external face of the mitochondria elicits changes in PDH phosphorylation – presumably there are intervening steps in the signaling pathway. DAG is the only signal known to be able to recruit PKCδ to membrane surfaces [50–52]. The origin of the pool of DAG that could function to recruit PKCδ to the mitochondrial surface is not known. The generation of DAG could occur either from dephosphorylation of PA or from hydrolysis of phosphoinositides by phospholipase C (PLC). Although PLC signaling is best known for taking place on the plasma membrane and in the nucleus, and the activation of PLC requires G-protein subunits [53], which have not been found at mitochondria, one isoform of PLC has been observed to localize to mitochondria [54], as discussed below. Production of DAG could also be mediated by dephosphorylation of PA via Type I or Type II PAPs [this issue, 6]. Type 2 PAPs are multi-pass transmembrane proteins that place their catalytic sites on the external surface of the cell or in the lumen of organelles [55], making them unlikely candidates for mediating conversion of PA on cytoplasmic-facing membrane leaflets to DAG. Recently however, Type I PAPs were identified as a pre-existing gene family known as the Lipins [56, 57]. Loss of activity of Lipin 1 causes a Type-II related diabetic lipodystrophy known as fatty liver dystrophy (fld) [58–60]. The syndrome is also characterized by abnormal mitochondrial handling of glucose and fatty acid metabolism [61], suggesting that PA or DAG on the outer mitochondrial surface might serve as a sensor for regulating mitochondrial energetics. These newly-found Type I PAP enzymes thus represent possible candidates for converting PA to DAG on the mitochondrial surface.

Placing these observations together, one possibility would be that insulin signaling stimulates mitochondrial fusion, resulting in increased MitoPLD-generated PA as fusing mitochondria come into contact. Increased PA on the mitochondrial surface would then recruit a Type I PAP such as Lipin, which would terminate the PA signaling by generating DAG. The DAG would recruit PKCδ, which in turn would active PDH and increase mitochondrial energy production. Exploration of this topic represents an area for future investigation.

3.2 PA, DAG, and potential roles in mitochondrial fusion and fission

PA and DAG have each been demonstrated to facilitate both fusion and fission of cytoplasmic membrane compartments in specific settings, for example, endocytosis from the plasma membrane [62, 63], budding of vesicles from the Golgi [64–70], peroxisome division [71], insertion of membrane vesicles into the plasma membrane [40, 72, 73], and fusion of nuclear envelope membrane precursor vesicles [74]. PA generation is required for mitochondrial fusion [23], but it has not been determined whether PA directly facilitates fusion, or whether the fusion event is promoted by DAG subsequent to metabolism of the PA by a PAP such as Lipin. Even more intriguingly, a link between fusion and fission has been described. Mitochondria undergo fusion on average every 24 minutes, but at seemingly random times within that average time frame [75]. Once fusion occurs, though, a fission event rapidly follows (on average, within 1.3 minutes). Thus, some consequence of the fusion event triggers a subsequent fission event. This is an attractive finding from the perspective of a pro-homeostasis mechanism evolved to prevent excessive fusion in the cell and to target fission events onto the largest of the mitochondria. The mechanism underlying the linkage of fission to fusion is not known, but an intriguing possibility would be that early stages of the fusion reaction lead to generation of PA and the completion of fusion, following which the PA is metabolized to DAG, elevated levels of which promote fission. Such a function would be consistent with roles for DAG in membrane fission at the trans-Golgi [66, 68] and in peroxisome division [71]. Examination of the linkage of fusion and fission in cell lines lacking MitoPLD or PAPs such as Lipin should provide insight into this possibility.

3.3 PI4,5P2 signaling pathways and potential roles on the mitochondrial surface

PLC-δ1 has been reported to localize to mitochondria and to facilitate mitochondrial calcium uptake [76, 77] through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. PI4,5P2 hydrolysis generates both phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphsophate (IP3) and DAG; the latter in this case is thought to be the relevant lipid signal that stimulates the Ca2+ uptake [54]. The requirement for biologically active PLC at the mitochondrial surface implies that PI4,5P2 should be found there, which has been reported [78]. Approximately 5% of the cellular PI4,5P2 is found at the mitochondrial outer membrane, resulting in a density for PI4,5P2 of approximately 25% of that found at the plasma membrane [79]. A PI4,5P2 -metabolizing enzyme, Synaptojanin 2a, has also been observed at the mitochondrial surface [79], and a second mitochondrial-localized PI4,5P2 phosphatase elicits changes in mitochondrial shape when overexpressed or targeted to the outer mitochondrial surface [80], suggesting that the endogenous levels of PI4,5P2 on the mitochondrial surface are physiologically significant. PI4,5P2 regulates F-actin assembly, which has been linked to recruitment of Drp1, a component of the mitochondrial fission apparatus, to future sites of cleavage [80], and F-actin interaction has been reported to regulate mitochondria subcellular movement [reviewed in 18]. PI4,5P2 is also key to linking membrane vesicles to dynein/kinesins to enable microtubule-based trafficking, and it may play a similar function for mitochondria, since overexpression of a PI4,5P2 -sequestering PLC-PH domain sensor disrupts the directed mitochondrial movement observed in neurons in response to nerve growth factor extracellular stimulation [14, 15, 25]. Mitochondria become redistributed in migrating cells [16], suggesting possible roles for PI4,5P2 in that process. Intriguingly, the atypical Rho GTPase, Miro, has been shown to have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking by residing on the mitochondrial outer membrane and interacting with kinesin-binding proteins [18, 26, 27]. Although compelling evidence suggests Miro acts as a calcium sensor using EF-hands to control mitochondrial mobility [81–83], as a GTPase, Miro can also be activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that remain to be identified. However, given the recent findings that DAG and PA can function at other subcellular membrane surfaces to recruit GEFs that activate the small GTPases Ras [84, 85] and Rac [86], it is possible that Miro could be regulated by mitochondrial lipid signals, such as DAG, PA, or PI4,5P2, via recruitment of its GEF. Moreover, microtubule motors (Dynein) have also been linked to Drp1 recruitment, again suggesting a role for PI4,5P2 [87].

Finally, the Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-Kinase that generate PI4,5P2 are well known to be recruited and regulated by PLD-generated PA [88]; hence most of the components that would be necessary for a signaling network involving MitoPLD-generated PA stimulation of PI4,5P2 synthesis leading to regulation of mitochondrial fission, movement, and Ca2+ homeostasis have been described, and the stage is set for conducting studies to establish their cell biological significance.

4. Conclusions

This review discusses a newly found pool of PA generated by MitoPLD and how this pool of PA on the mitochondrial surface might serve as a signaling lipid and function in diverse cell biological settings related to mitochondrial biology. MitoPLD mirrors its classic family members PLD1 and 2 by producing one or more potent lipid second messengers on the mitochondrial surface. Besides promoting mitochondrial fusion, MitoPLD-generated PA may also regulate mitochondrial fission, translocation, calcium homeostasis, and energy production. This field represents a novel area for future study and may identify even more players involved in signaling pathways on the mitochondrial surface.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH awards GM071520 and GM084251.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haucke V, Di Paolo G. Lipids and lipid modifications in the regulation of membrane traffic. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2007;19:426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang P, Frohman MA. The potential for phospholipase D as a new therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:707–716. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins GM, Frohman MA. Phospholipase D: a lipid centric review. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62:2305–2316. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5195-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott M, Wakelam MJ, Morris AJ. Phospholipase D. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:225–253. doi: 10.1139/o03-079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topham M. Diacylglycerol Kinases as Sources of Phosphatidic Acid. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brindley DN, Pilquil C, Sariahmetoglu M, Reue K. Phosphatidate degradation: Lipins and lipid phosphate phosphatases. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockcroft S. Phosphatidic acid regulation of Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinases. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.03.007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2006;22:79–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margineantu DH, Gregory Cox W, Sundell L, Sherwood SW, Beechem JM, Capaldi RA. Cell cycle dependent morphology changes and associated mitochondrial DNA redistribution in mitochondria of human cell lines. Mitochondrion. 2002;1:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(02)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taguchi N, Ishihara N, Jofuku A, Oka T, Mihara K. Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:11521–11529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawlikowska P, Gajkowska B, Orzechowski A. Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2): a key player in insulin-dependent myogenesis in vitro. Cell and tissue research. 2007;327:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson-Fritch L, Nicoloro S, Chouinard M, Lazar MA, Chui PC, Leszyk J, Straubhaar J, Czech MP, Corvera S. Mitochondrial remodeling in adipose tissue associated with obesity and treatment with rosiglitazone. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:1281–1289. doi: 10.1172/JCI21752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka A, Youle RJ. A chemical inhibitor of DRP1 uncouples mitochondrial fission and apoptosis. Molecular cell. 2008;29:409–410. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chada SR, Hollenbeck PJ. Mitochondrial movement and positioning in axons: the role of growth factor signaling. The Journal of experimental biology. 2003;206:1985–1992. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chada SR, Hollenbeck PJ. Nerve growth factor signaling regulates motility and docking of axonal mitochondria. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1272–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campello S, Lacalle RA, Bettella M, Manes S, Scorrano L, Viola A. Orchestration of lymphocyte chemotaxis by mitochondrial dynamics. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2879–2886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinel H, Cancela JM, Mogami H, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH. Active mitochondria surrounding the pancreatic acinar granule region prevent spreading of inositol trisphosphate-evoked local cytosolic Ca(2+) signals. Embo J. 1999;18:4999–5008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollenbeck PJ, Saxton WM. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5411–5419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, Zappia M, Nelis E, Patitucci A, Senderek J, Parman Y, Evgrafov O, De Jonghe P, Takahashi Y, Tsuji S, Pericak-Vance MA, Quattrone A, Battologlu E, Polyakov AV, Timmerman V, Schroder JM, Vance JM. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nature Genetics. 2004;36:449–451. doi: 10.1038/ng1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olichon A, Guillou E, Delettre C, Landes T, Arnaune-Pelloquin L, Emorine LJ, Mils V, Daloyau M, Hamel C, Amati-Bonneau P, Bonneau D, Reynier P, Lenaers G, Belenguer P. Mitochondrial dynamics and disease, OPA1. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Cell Research. 2006;1763:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koshiba T, Detmer SA, Kaiser JT, Chen HC, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Structural basis of mitochondrial tethering by mitofusin complexes. Science. 2004;305:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1099793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SY, Huang P, Jenkins GM, Chan DC, Schiller J, Frohman MA. A common lipid links Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion and SNARE-regulated exocytosis. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8:1255–1262. doi: 10.1038/ncb1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smirnova E, Shurland DL, Ryazantsev SN, van der Bliek AM. A human dynamin-related protein controls the distribution of mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:351–358. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vos KJ, Sable J, Miller KE, Sheetz MP. Expression of phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate-specific pleckstrin homology domains alters direction but not the level of axonal transport of mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3636–3649. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo X, Macleod GT, Wellington A, Hu F, Panchumarthi S, Schoenfield M, Marin L, Charlton MP, Atwood HL, Zinsmaier KE. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron. 2005;47:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fransson S, Ruusala A, Aspenstrom P. The atypical Rho GTPases Miro-1 and Miro-2 have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;344:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: More than just a powerhouse. Current Biology. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madesh M, Balasubramanian KA. Metal ion stimulation of phospholipase D-like activity of isolated rat intestinal mitochondria. Lipids. 1997;32:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s11745-997-0061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin JK, Kim NH, Lee YJ, Kim YS, Choi EK, Kozlowski PB, Park MH, Kim HS, Min DS. Phospholipase D1 is up-regulated in the mitochondrial fraction from the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;407:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin JK, Ahn BH, Na YJ, Kim JI, Kim YS, Choi EK, Ko YG, Chung KC, Kozlowski PB, Min DS. Phospholipase D1 is associated with amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28:1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowell CF, Doppler H, Yan IK, Hausser A, Umezawa Y, Storz P. Mitochondrial diacylglycerol initiates protein-kinase-D1-mediated ROS signaling. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:919–928. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnoczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond SM, Altshuller YM, Sung TC, Rudge SA, Rose K, Engebrecht J, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. Human ADP-ribosylation factor-activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase D defines a new and highly conserved gene family. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:29640–29643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uesugi Y, Hatanaka T. Phospholipase D mechanism using Streptomyces PLD. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.020. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuckey JA, Dixon JE. Crystal structure of a phospholipase D family member. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:278–284. doi: 10.1038/6716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JH, Dai Q, Chen J, Durrant D, Freeman A, Liu T, Grossman D, Lee RM. Phospholipid scramblase 3 controls mitochondrial structure, function, and apoptotic response. Molecular Cancer Research. 2003;1:892–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hovius R, Thijssen J, Vanderlinden P, Nicolay K, Dekruijff B. Phospholipid Asymmetry of the Outer-Membrane of Rat-Liver Mitochondria - Evidence for the Presence of Cardiolipin on the Outside of the Outer-Membrane. Febs Letters. 1993;330:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80922-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeniou-Meyer M, Zabari N, Ashery U, Chasserot-Golaz S, Haeberle AM, Demais V, Bailly Y, Gottfried I, Nakanishi H, Neiman AM, Du G, Frohman MA, Bader MF, Vitale N. Phospholipase D1 production of phosphatidic acid at the plasma membrane promotes exocytosis of large dense-core granules at a late stage. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:21746–21757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang P, Altshuller YM, Hou JC, Pessin JE, Frohman MA. Insulin-stimulated plasma membrane fusion of Glut4 glucose transporter-containing vesicles is regulated by phospholipase D1. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16:2614–2623. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vicogne J, Vollenweider D, Smith J, Huang P, Frohman M, Pessin J. Asymmetric phospholipid distribution drives in vitro reconstituted SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14761–14766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606881103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu L, Liao H, Castle A, Zhang J, Casanova J, Szabo G, Castle D. SCAMP2 interacts with Arf6 and phospholipase D1 and links their function to exocytotic fusion pore formation in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4463–4472. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoch FL. Cardiolipins and biomembrane function. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1992;1113:71–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlame M, Rua D, Greenberg ML. The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Progress in lipid research. 2000;39:257–288. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright MM, Howe AG, Zaremberg V. Cell membranes and apoptosis: role of cardiolipin, phosphatidylcholine, and anticancer lipid analogues. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:18–26. doi: 10.1139/o03-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi SY, Gonzalvez F, Jenkins GM, Slomianny C, Chretien D, Arnoult D, Petit PX, Frohman MA. Cardiolipin deficiency releases cytochrome c from the inner mitochondrial membrane and accelerates stimuli-elicited apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:597–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallegos LL, Kunkel MT, Newton AC. Targeting protein kinase C activity reporter to discrete intracellular regions reveals spatiotemporal differences in agonist-dependent signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:30947–30956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sato M, Ueda Y, Umezawa Y. Imaging diacylglycerol dynamics at organelle membranes. Nature methods. 2006;3:797–799. doi: 10.1038/nmeth930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caruso M, Maitan MA, Bifulco G, Miele C, Vigliotta G, Oriente F, Formisano P, Beguinot F. Activation and mitochondrial translocation of protein kinase C delta are necessary for insulin stimulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in muscle and liver cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:45088–45097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dries DR, Gallegos LL, Newton AC. A single residue in the C1 domain sensitizes novel protein kinase C isoforms to cellular diacylglycerol production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:826–830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho W. Membrane targeting by C1 and C2 domains. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:32407–32410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stahelin RV, Digman MA, Medkova M, Ananthanarayanan B, Rafter JD, Melowic HR, Cho W. Mechanism of diacylglycerol-induced membrane targeting and activation of protein kinase Cdelta. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:29501–29512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drin G, Scarlata S. Stimulation of phospholipase C beta by membrane interactions, interdomain movement, and G protein binding - How many ways can you activate an enzyme? Cellular Signalling. 2007;19:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knox CD, Belous AE, Pierce JM, Wakata A, Nicoud IB, Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Chari RS. Novel role of phospholipase C-delta 1: regulation of liver mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2004;287:G533–G540. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jasinska R, Zhang QX, Pilquil C, Singh I, Xu J, Dewald J, Dillon DA, Berthiaume LG, Carman GM, Waggoner DW, Brindley DN. Lipid phosphate phosphohydrolase-1 degrades exogenous glycerolipid and sphingolipid phosphate esters. Biochemical Journal. 1999;340:677–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donkor J, Sariahmetoglu M, Dewald J, Brindley DN, Reue K. Three mammalian lipins act as phosphatidate phosphatases with distinct tissue expression patterns. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:3450–3457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han GS, Wu WI, Carman GM. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:9210–9218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600425200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris TE, Huffman TA, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Kumar A, Lawrence JC., Jr Insulin controls subcellular localization and multisite phosphorylation of the phosphatidic acid phosphatase, lipin 1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:277–286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loos RJ, Rankinen T, Perusse L, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Bouchard C. Association of lipin 1 gene polymorphisms with measures of energy and glucose metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007;15:2723–2732. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nature Genetics. 2001;27:121–124. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu J, Lee WN, Phan J, Saad MF, Reue K, Kurland IJ. Lipin deficiency impairs diurnal metabolic fuel switching. Diabetes. 2006;55:3429–3438. doi: 10.2337/db06-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du G, Huang P, Liang BT, Frohman MA. Phospholipase D2 localizes to the plasma membrane and regulates angiotensin II receptor endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1024–1030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee CS, Kim IS, Park JB, Lee MN, Lee HY, Suh PG, Ryu SH. The phox homology domain of phospholipase D activates dynamin GTPase activity and accelerates EGFR endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:477–484. doi: 10.1038/ncb1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen YG, Siddhanta A, Austin CD, Hammond SM, Sung TC, Frohman MA, Morris AJ, Shields D. Phospholipase D stimulates release of nascent secretory vesicles from the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:495–504. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang JS, Gad H, Lee S, Mironov A, Zhang L, Beznoussenko GV, Valente C, Turacchio G, Bonsra AN, Du G, Baldanzi G, Graziani A, Bourgoin S, Frohman MA, Luini A, Hsu VW. COPI vesicle fission: a role for phosphatidic acid and insight into Golgi maintenance. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1146–1153. doi: 10.1038/ncb1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bossard C, Bresson D, Polishchuk RS, Malhotra V. Dimeric PKD regulates membrane fission to form transport carriers at the TGN. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1123–1131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diaz Anel AM. Phospholipase C beta3 is a key component in the Gbetagamma/PKCeta/PKD-mediated regulation of trans-Golgi network to plasma membrane transport. The Biochemical journal. 2007;406:157–165. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fernandez-Ulibarri I, Vilella M, Lazaro-Dieguez F, Sarri E, Martinez SE, Jimenez N, Claro E, Merida I, Burger KN, Egea G. Diacylglycerol is required for the formation of COPI vesicles in the Golgi-to-ER transport pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3250–3263. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghanekar Y, Lowe M. Protein kinase D: activation for Golgi carrier formation. Trends in cell biology. 2005;15:511–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shemesh T, Luini A, Malhotra V, Burger KN, Kozlov MM. Prefission constriction of Golgi tubular carriers driven by local lipid metabolism: a theoretical model. Biophysical journal. 2003;85:3813–3827. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74796-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo T, Gregg C, Boukh-Viner T, Kyryakov P, Goldberg A, Bourque S, Banu F, Haile S, Milijevic S, San KH, Solomon J, Wong V, Titorenko VI. A signal from inside the peroxisome initiates its division by promoting the remodeling of the peroxisomal membrane. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:289–303. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vitale N, Caumont AS, Chasserot-Golaz S, Du G, Wu S, Sciorra VA, Morris AJ, Frohman MA, Bader MF. Phospholipase D1: a key factor for the exocytotic machinery in neuroendocrine cells. Embo J. 2001;20:2424–2434. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jun Y, Fratti RA, Wickner W. Diacylglycerol and its formation by phospholipase C regulate Rab- and SNARE-dependent yeast vacuole fusion. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:53186–53195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barona T, Byrne RD, Pettitt TR, Wakelam MJ, Larijani B, Poccia DL. Diacylglycerol induces fusion of nuclear envelope membrane precursor vesicles. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:41171–41177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, Stiles L, Haigh SE, Katz S, Las G, Alroy J, Wu M, Py BF, Yuan J, Deeney JT, Corkey BE, Shirihai OS. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. Embo J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Belous AE, Jones CM, Wakata A, Knox CD, Nicoud IB, Pierce J, Chari RS. Mitochondrial calcium transport is regulated by P2Y1- and P2Y2-like mitochondrial receptors. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2006;99:1165–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knox CD, Pierce JM, Nicoud IB, Belous AE, Jones CM, Anderson CD, Chari RS. Inhibition of phospholipase C attenuates liver mitochondrial calcium overload following cold ischemia. Transplantation. 2006;81:567–572. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000199267.98971.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Watt SA, Kular G, Fleming IN, Downes CP, Lucocq JM. Subcellular localization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate using the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C delta1. The Biochemical journal. 2002;363:657–666. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nemoto Y, De Camilli P. Recruitment of an alternatively spliced form of synaptojanin 2 to mitochondria by the interaction with the PDZ domain of a mitochondrial outer membrane protein. EMBO J. 1999;18:2991–3006. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.De Vos KJ, Allan VJ, Grierson AJ, Sheetz MP. Mitochondrial function and actin regulate dynamin-related protein 1-dependent mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol. 2005;15:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Macaskill AF, Rinholm JE, Twelvetrees AE, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Muir J, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Attwell D, Kittler JT. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang X, Schwarz TL. The mechanism of Ca2+-dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saotome M, Safiulina D, Szabadkai G, Das S, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G. Bidirectional Ca2+-dependent control of mitochondrial dynamics by the Miro GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20728–20733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mor A, Campi G, Du G, Zheng Y, Foster DA, Dustin ML, Philips MR. The lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 receptor costimulates plasma membrane Ras via phospholipase D2. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:712–719. doi: 10.1038/ncb1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao C, Du G, Skowronek K, Frohman MA, Bar-Sagi D. Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:707–712. doi: 10.1038/ncb1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nishikimi A, Fukuhara H, Su W, Hongu T, Takasuga S, Mihara H, Cao Q, Sanematsu F, Kanai M, Hasegawa H, Tanaka Y, Shibasaki M, Kanaho Y, Sasaki T, Frohman MA, Fukui Y. Sequential Regulation of DOCK2 Dynamics by Two Phospholipids during Neutrophil Chemotaxis. Science. 2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1170179. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Varadi A, Johnson-Cadwell LI, Cirulli V, Yoon Y, Allan VJ, Rutter GA. Cytoplasmic dynein regulates the subcellular distribution of mitochondria by controlling the recruitment of the fission factor dynamin-related protein-1. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4389–4400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Honda A, Nogami M, Yokozeki T, Yamazaki M, Nakamura H, Watanabe H, Kawamoto K, Nakayama K, Morris AJ, Frohman MA, Kanaho Y. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase alpha is a downstream effector of the small G protein ARF6 in membrane ruffle formation. Cell. 1999;99:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]