Abstract

In response to cold, Escherichia coli produces cold shock proteins (CSPs) that have essential roles in cold adaptation as RNA chaperones. Here, we demonstrate that Arabidopsis cold shock domain protein 3 (AtCSP3), which shares a cold shock domain with bacterial CSPs, is involved in the acquisition of freezing tolerance in plants. AtCSP3 complemented a cold-sensitive phenotype of the E. coli CSP quadruple mutant and displayed nucleic acid duplex melting activity, suggesting that AtCSP3 also functions as an RNA chaperone. Promoter-GUS transgenic plants revealed tissue-specific expression of AtCSP3 in shoot and root apical regions. When exposed to low temperature, GUS activity was extensively induced in a broader region of the roots. In transgenic plants expressing an AtCSP3-GFP fusion, GFP signals were detected in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. An AtCSP3 knock-out mutant (atcsp3-2) was sensitive to freezing compared with wild-type plants under non-acclimated and cold-acclimated conditions, whereas expression of C-repeat-binding factors and their downstream genes during cold acclimation was not altered in the atcsp3-2 mutant. Overexpression of AtCSP3 in transgenic plants conferred enhanced freezing tolerance over wild-type plants. Together, the data demonstrated an essential role of RNA chaperones for cold adaptation in higher plants.

Many plant species acquire substantial freezing tolerance after exposure to low but non-freezing temperatures, a process known as cold acclimation (1). Cold acclimation (CA)2 induces cellular and physiological changes including alteration in gene expression (2). Cold-regulated (COR) genes are highly expressed during cold acclimation and contribute substantially to acquiring freezing tolerance. The C-repeat-binding factors (CBF) or dehydration responsive element-binding protein 1 (DREB1) have been identified as transcription activators for COR gene expression (3, 4). They play a key role in the signal transduction pathway for cold acclimation and ectopic expression of CBF genes in plants confers tolerance against freezing and other related stresses (3, 4). In addition to the major CBF-dependent pathway, CBF-independent pathways are also thought to be necessary for cold acclimation (5–7). Elucidating the role of these non-CBF pathways is thus required to fully understand cold acclimation mechanisms in plants.

Cold acclimation is also observed in diverse organisms including bacteria, where it is known as the cold shock response. The major cold shock protein (CSP) in Escherichia coli, CspA, is dramatically induced immediately following a temperature downshift and accumulates to represent up to 10% of total soluble protein (8, 9). Nine members of the CSP gene family (cspA to cspI) have been identified in E. coli, and four of these have been shown to be induced by cold shock (10). The three-dimensional structure of CSP proteins consists of a closed five-stranded anti-parallel β-barrel capped by a long flexible loop and contains two consensus RNA-binding motifs (RNP1 and RNP2) that contribute to bind nucleic acids (8, 11, 12). CSPs can destabilize the secondary structures in RNA and thus function as RNA chaperones to regulate transcription and translation in bacteria (11, 13). Bacterial CSPs are considered to be the most ancient form of the RNA binding protein, which is also found in eukaryote proteins as a RNA-binding domain called the cold shock domain (CSD) (13).

Among the most widely studied eukaryotic CSD proteins is the Y-Box protein family. All vertebrate Y-box proteins contain a variable N-terminal domain, cold shock domain, and a C-terminal auxiliary domain. Y-box protein was originally identified as a protein binding to the Y-box sequence (CTGATTGG) of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II gene promoter (14). Subsequent studies have shown that Y-box proteins are transcription factors that can negatively or positively regulate gene expression in several genes (15, 16). Despite the function as a transcription factor, the majority of the human Y-box protein YB-1 is found in the cytosol as part of the messenger ribonucleoprotein complex (mRNP). YB-1 stimulates or inhibits translation depending on the YB-1/mRNA ratio (17, 18). Another class of eukaryotic CSD protein is the newly emerging LIN28 family. Initially identified as a heterochronic gene in Caenorhabditis elegans (19), LIN28 is now known to function in the enhancement of translation (20), biogenesis of miRNA (21), and generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (22).

Highly conserved CSD is also found in a diverse genera of lower and higher plants (23). In wheat, the wheat cold shock protein 1 (WCSP1) accumulates in crown tissue during cold acclimation (24) and is composed of a CSD and a glycine-rich domain containing three CCHC zinc fingers (Fig. 1A). WCSP1 displays activity to bind ssDNA, dsDNA, and RNA, and unwinds nucleic acid duplexes (24–26). Heterologous expression of WCSP1 in an E. coli cspA, cspB, cspE, cspG quadruple deletion mutant complemented its cold sensitive phenotype. WCSP1 was also demonstrated to have transcriptional anti-termination activity in E. coli (26). These studies indicated that WCSP1 functions as a RNA chaperone to destabilize RNA secondary structures. However, the detailed functions of WCSP1 in planta remain to be elucidated.

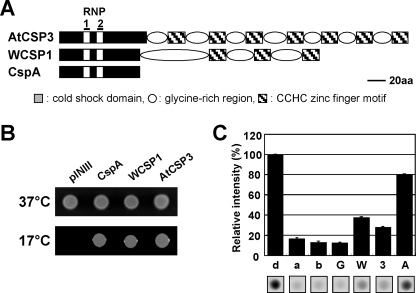

FIGURE 1.

Biochemical characterization of AtCSP3. A, schematic representation of the primary structure of AtCSP3 aligned with E. coli CspA and wheat WCSP1. B, complementation of cold sensitive growth of BX04 (ΔcspAΔcspBΔcspEΔcspG) with AtCSP3, cspA, and WCSP1. Overnight cultures of BX04/pINIII, BX04/AtCSP3, BX04/cspA, and BX04/WCSP1 were diluted to adjust cell density, spotted onto plates, and incubated at 37 °C for 1 day or 17 °C for 3 days. C, nucleic acid melting activity of AtCSP3. One pmol of annealed molecular beacon (a) was incubated with 300 pmol of GST (G), AtCSP3 (3), WCSP1 (W), CspA (A), or equal amount of the buffer (b). Fluorescence is expressed as a relative value against fluorescence of denatured beacon (d).

Arabidopsis thaliana has four CSD proteins that displayed differential regulation in response to low temperature (23). Two of these proteins (AtGRP2/AtCSP2/At4g38680 and AtGRP2b/AtCSP4/At2g21060) contain two CCHC zinc fingers and the other two (AtCSP1/At4g36020 and AtCSP3/At2g17870) contain seven CCHC zinc fingers within the glycine-rich region (23). AtCSP2 has been subject to further characterization (27–29) and shown to unwind a nucleic acid duplex and partially complement the E. coli cspA, cspB, cspE, cspG quadruple deletion mutant (27). AtCSP2 is regulated by developmental cues, as well as low temperature (27, 28), and is possibly involved in flowering time control (28). AtCSP2 mRNA (27, 28) and protein levels (27) increased during cold acclimation, and localization of AtCSP2::GFP was shown to be in the nucleolus and cytoplasm (27).

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism of Arabidopsis CSD proteins during cold acclimation, we have chosen the Arabidopsis AtCSP3 (At2g17870) protein for further characterization. AtCSP3 was shown to function as an RNA chaperone, sharing this biochemical function with bacterial CSPs and wheat WCSP1. In vivo functional analyses with overexpressors and a knock-out mutant as well as expression analyses indicate that AtCSP3 regulates freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis during cold acclimation independent of the CBF/DREB1 pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant Protein Production and Biochemical Characterization

For recombinant protein production, AtCSP3 was amplified from A. thaliana (Col-0) cDNA template with the primers listed in supplemental Table S2. The amplified PCR products were digested with SalI and NotI and ligated into predigested pGEX-6P-3 (GE Healthcare) to produce pGEX-AtCSP3. Construction of pGEX-WCSP1 and pGEX-CspA was described previously (26). Recombinant proteins were overexpressed in E. coli BL21 cells containing each plasmid and were purified with GST-Sepharose column chromatography and PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) digestion (25, 26). Gel shift analysis and in vitro DNA-melting assays with the purified recombinant AtCSP3 protein were performed as previously described (25).

Bacterial Complementation

AtCSP3 was cloned into the pINIII vector by creating an in-frame N-terminal NdeI and a C-terminal BamHI sites using PCR primers (supplemental Table S2). Construction of pINIII-WCSP1 and pINIII-cspA was described previously (26). These pINIII constructs were transformed into E. coli BX04 (ΔcspA, ΔcspB, ΔcspE, ΔcspG) cells. Cultures of BX04 cells with respective plasmids were diluted and spotted onto LB-ampicillin plates and grown at either 37 or 17 °C.

AtCSP3 Promoter::GUS and AtCSP3 Promoter::AtCSP3-GFP Analysis

The promoter region of AtCSP3 (1219-bp) was cloned by genomic PCR with a primer set (supplemental Table S2). The PCR product was digested with PstI and BamHI and inserted into pBI121 (Clontech). Arabidopsis (Col-0) plants were transformed by the Agrobacterium-mediated floral dip method (30). Tissues from transgenic plants were fixed and stained in 1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (X-gluc) solution.

A genomic fragment including the promoter and coding regions of AtCSP3 (2125 bp) was amplified by PCR (supplemental Table S2) and cloned into pENTR directional TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and further transferred into pGWB4 binary vector (T. Nakagawa, Shimane University) using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). Independent T2 progeny of 10-day-old transgenic seedlings were used for analyzing GFP activity. To visualize nuclei, seedlings were soaked in solution of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 μg/ml).

T-DNA Knock-out Mutant and Overexpression of AtCSP3

The homozygous atcsp3-2 mutant was identified by genomic PCR. Disruption of AtCSP3 expression was confirmed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using gene-specific primers (supplemental Table S2). Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as described (27). 35S::AtCSP3 was generated by cloning AtCSP3 into the XbaI-SacI site of pBI121. Homozygous T3 plants were used for analysis. For complementation analysis, promoter of 35S::AtCSP3 was replaced by the 1219-bp AtCSP3 promoter, and the resulting construct was used to transform atcsp3-2 using Agrobacterium.

Northern and Western Blot Analysis

Total RNA extraction and gel blot analysis were performed as described (24). Specific hybridization probes for CBFs (31), COR15A (32), COR47 (33), RD29A, and KIN1 (33), and ZAT12 (34) were generated by PCR (supplemental Table S2). Protein extraction and Western blot analysis were performed as described (27). Chemiluminescent signals were analyzed using a LAS3000 luminoimager (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Freezing Tolerance Analysis

Freeze-thaw survival was determined as previously described (5). Non-acclimated and cold-acclimated (7 days at 4 °C) seedlings were transferred to a programmed freezer LU-112 (TABAI, Tokyo, Japan) set at −2 °C and maintained for 2 h prior to ice nucleation with ice chips and further incubation at −2 °C for 14 h. Subsequently, the chamber temperature was cooled at a rate of −1 °C per hour. Plates were then maintained at 4 °C for 12 h for thawing. Survival rate was scored after 7 days.

For electrolyte leakage tests, one excised rosette leaf was placed in a tube containing 300 ml of ice-containing distilled water for ice nucleation and the tube was maintained at −2 °C for 1 h in the programmed freezer. The chamber was then cooled at a rate of −1 °C h−1. The tubes were removed upon reaching the designated temperatures and were placed at 2 °C for 1 h for slow thawing and subsequently shaken at 25 °C for 2 h. The electrolyte leakage was measured using a compact conductivity meter C-172 (HORIBA, Kyoto, Japan). Electrolyte leakage was expressed as the percentage conductivity of the sample frozen to −80 °C.

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from 10-day-old seedlings of WT and the atcsp3-2 mutant with RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). 44k Agilent Arabidopsis 3 microarray (Agilent Technologies) were utilized for the analysis. Hybridization, washing, and scanning were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. The microarray analysis was performed with RNA isolated from two independently harvested plant tissues.

RESULTS

Biochemical Function of AtCSP3 Protein

AtCSP3 is comprised of a cold shock domain (CSD) with two consensus RNA-binding motifs (RNP1 and RNP2) and a glycine-rich region interspersed by seven CCHC-type zinc finger motifs (Fig. 1A). Recombinant AtCSP3 protein was purified and its nucleic acid-binding activity was tested by gel shift analysis (supplemental Fig. S1). Band shifts appeared on gels indicated that AtCSP3 was able to bind ss/dsDNA and mRNA (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). To determine if AtCSP3 complements the CSP function in E. coli, BX04 (ΔcspA, ΔcspB, ΔcspE, ΔcspG), which is defective in growth at low temperature (35), was utilized. BX04 transformed with the vector alone showed no visible growth at 17 °C, whereas this growth defect was suppressed by expression of AtCSP3 in BX04 (Fig. 1B). Similar suppression of the growth defect was observed with BX04 cells expressing cspA or WCSP1. The main activity of E. coli CSPs is to melt double-stranded nucleic acid. It was therefore tested if AtCSP3 has nucleic acid melting activity. An in vitro molecular beacon system (26) was utilized to quantitate the melting activity. Recombinant AtCSP3 exhibited a relative beacon fluorescence (27.3%) that is substantially higher than that with buffer alone (14.4%) or GST (14.0%) (Fig. 1C), indicating melting activity of AtCSP3. Under the conditions utilized, a slightly higher activity was observed with WCSP1, however, the activity exhibited by CspA (80.0%) was distinctively higher than that of both plant CSD proteins (Fig. 1C).

Expression of AtCSP3 during Cold Acclimation

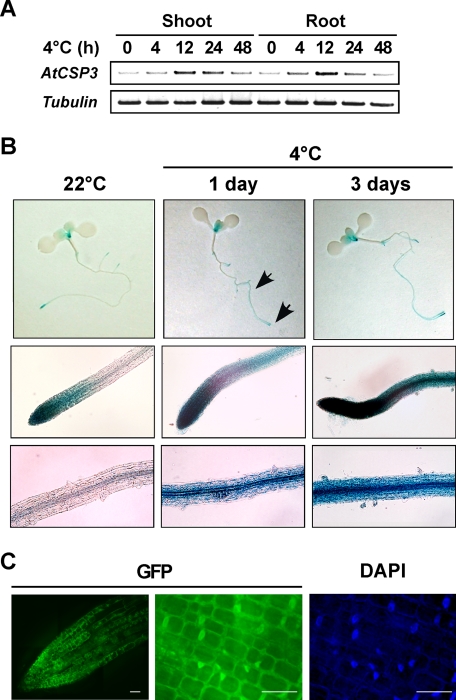

RT-PCR analyses were performed to investigate regulation of AtCSP3 expression (Fig. 2A). AtCSP3 transcripts were transiently up-regulated by cold treatment in both shoot and root of 10-day-old seedlings (Fig. 2A). To determine the temporal and spatial expression pattern of AtCSP3 expression, we analyzed transgenic plants transformed with an AtCSP3 promoter::GUS fusion construct. During seed germination, GUS activity was not detected in dry or imbibed seeds of the transgenic plants. GUS activity was first detectable in primary root after 2 days of germination (supplemental Fig. S2, A–C) and was limited to the tip region of the primary root at 4 days postgermination. In 10-day-old seedlings, GUS staining was detected in both the root tip and shoot apex (Fig. 2B). GUS expression in the root tip and shoot apex was maintained in 3-week-old seedlings (supplemental Fig. S2, I and J). In response to cold, GUS activity was induced and detectable in a broader region in roots of 10-day-old seedlings (Fig. 2B). After flowering stage, pollen within anthers (supplemental Fig. S2, G and H), and the base of siliques (supplemental Fig. S2F) showed GUS staining.

FIGURE 2.

Expression in response to cold and subcellular localization of AtCSP3. A, semi-quantitative RT-PCR with RNA from shoot and root tissues of 10-day-old seedlings. B, histochemical localization of GUS activity in AtCSP3 promoter-GUS transgenic seedlings. 10-day-old seedlings grown on agar plates were treated with cold stress (4 °C for 1 or 3 days). The top row (panels) shows whole seedlings. Middle and bottom rows show root tip including distal elongation zone and the central portion of the root, respectively (indicated by arrows). Scale bars are: top, 1 μm; middle, 50 μm; bottom, 20 μm. C, fluorescence microscopic images of the cells expressing the AtCSP3-GFP fusion gene. Deconvolution images of primary root tip from 10-day-old transgenic seedling were visualized for GFP (left and middle panel). DAPI staining (right panel) was performed for nuclear localization. Scale bars are 10 μm.

To examine the subcellular localization of AtCSP3, the promoter and coding region of AtCSP3 was fused in-frame to the GFP reporter gene and introduced into transgenic plants. AtCSP3-GFP was detected in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of root tip cells (Fig. 2C). Similar to the GUS reporter assay, expression of AtCSP3-GFP was detected in the apical regions of roots (Fig. 2C) and shoots (data not shown) and was expanded to a broader region in response to cold (supplemental Fig. S2K). The nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of GFP was not altered by cold treatment (data not shown).

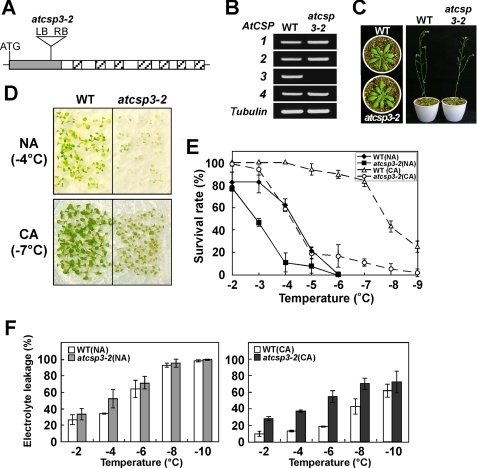

The atcsp3-2 Mutant Exhibits Reduced Freezing Tolerance

A T-DNA mutation line (WiscDsLox353G12) containing a T-DNA inserted 171-bp downstream of the AtCSP3 start codon (Fig. 3A) was obtained from the ABRC collection. RT-PCR analysis confirmed the specific disruption of AtCSP3 expression in this line (atcsp3-2) (Fig. 3B). The atcsp3-2 mutant did not show any abnormal morphological or developmental phenotypes under normal growth conditions (Fig. 3C). To understand the role of AtCSP3 in cold acclimation, we examined freezing tolerance of the 10-day-old seedlings in wild-type and atcsp3-2 backgrounds. Freezing tolerance was scored by survival rate after a freeze-thaw program. Under a non-acclimated (NA) condition, freezing tolerance of atcsp3-2 was diminished as compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 3, D and E). Both wild type and atcsp3-2 showed increased freezing tolerance after cold acclimation, however, the difference in freezing tolerance became more prominent under the cold-acclimated condition (Fig. 3, D and E). This suggested that AtCSP3 is involved in both constitutive and cold-induced tolerance against freezing. An electrolyte leakage analysis was performed to compare freezing tolerance at cellular levels. Rosette leaves of atcsp3-2 plants exhibited higher levels of leakage than the wild-type under non-acclimated condition. After cold acclimation, wild-type showed great induced tolerance against electrolyte leakage, while atcsp3-2 showed only small induced-tolerance (Fig. 3F). To establish the causal effect of AtCSP3 in the diminished freezing tolerance, we transformed atcsp3-2 mutant plants with the AtCSP3 gene containing its own 1.2-kb promoter region. Two independent lines of transgenic plants restored freezing tolerance (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 3.

Freezing tolerance of the atcsp3-2 mutant. A, schematic representation of the position of T-DNA insertion within the cold shock domain of AtCSP3. B, RT-PCR expression analysis of AtCSP genes in WT and the atcsp3-2 mutant. The tubulin gene was amplified as a control. C, phenotypes of 3- (left) and 5-week-old (right) wild-type and atcsp3-2 mutant plants grown in soil. D, freezing tolerance of 2-week-old wild-type and atcsp3-2 mutant seedlings grown on plates with CA and without NA. The photographs were taken at 7 days after recovery from freezing treatment. E, survival rates for 2-week-old wild type and atcsp3-2 mutant seedlings with or without cold acclimation at different freezing temperatures. F, electrolyte leakage of 3-week-old rosette leaves of wild type and atcsp3-2 mutant with or without cold acclimation. For cold acclimation, plants were treated at 4 °C for 7 days under continuous white light.

Expression of Cold-inducible Genes in atcsp3-2 Mutant

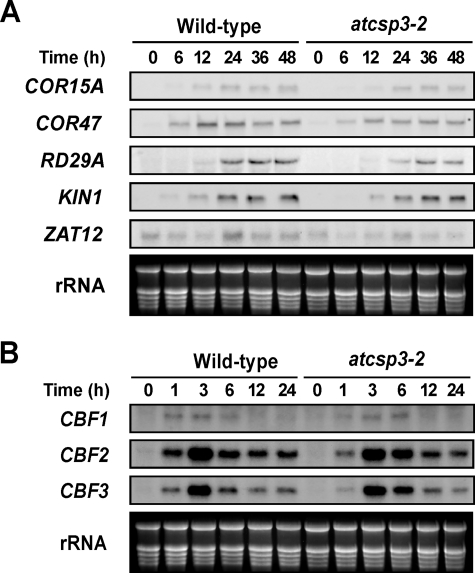

To determine whether the decreased freezing tolerance in atcsp3-2 mutant is associated with CBF/DREB1-dependent pathway, the effect of the atcsp3-2 mutation on transcript levels of cold-inducible and CBF (DREB1)-regulated genes was measured. Transcript levels of four CBF-regulon genes, COR15, COR47, LTI78, KIN1, and a non-CBF-regulon gene, ZAT12, increased in response to cold in both wild-type and atcsp3-2 in a similar manner (Fig. 4A). Expression of three CBF genes, CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3, were also induced to similar levels by cold treatment in both wild type and atcsp3-2, although the induction kinetics may be slightly altered (Fig. 4B). Together, these data suggested that the CBF-dependent pathway is functioning in atcsp3-2 and that the impaired freezing tolerance in atcsp3-2 may be due to a defect in a non-CBF pathway.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of cold-inducible genes in wild type and atcsp3-2 mutant plants. Northern blot analysis with total RNA (10 μg) from 10-day-old seedlings that were treated with cold (4 °C) for the indicated times periods. Ethidium bromide-stained rRNA was used as a loading control. A, transcript levels of COR15A, COR47, LTI78, KIN1, and ZAT12 in wild type and atcsp3-2 mutant plants. B, transcript levels of CBF/DREB1 genes in wild type and atcsp3-2 mutant.

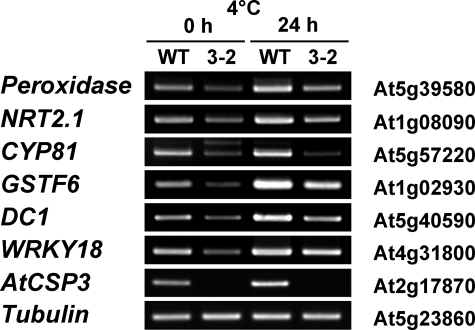

Microarray analysis utilizing the 44 k Agilent Arabidopsis 3 microarray (Agilent Technologies) revealed a total of 19 genes that were down-regulated in atcsp3-2, with a ratio of ≥2.5 (supplemental Table S1). Most of the down-regulated genes in atcsp3-2 were considered abiotic stress-inducible according to data from the Arabidopsis eFP Browser (supplemental Table S1). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed to confirm the expression of six of cold inducible down-regulated candidates (Fig. 5). The expression of the cytochrome P450 (At5G57220), putative peroxidase (At5g39580), glutathione S-transferase (At1g02930), WRKY18 (At4g31800), DC1 domain-containing (At5g40590), and NRT2.1 (At1g08090) was lower in atcsp3-2 mutant. Expression of these genes was induced in wild-type and atcsp3-2 mutant plant after cold treatment (4 °C, 24 h), however, their expression was still suppressed in atcsp3-2 (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

RT-PCR expression analysis of genes selected from microarray analysis. Wild-type and atcsp3-2 mutant seedlings were treated with or without cold acclimation for 24 h. Primers of six down-regulated genes in atcsp3-2 mutant plants were described in supplemental Table S2. The tubulin gene was amplified as a control.

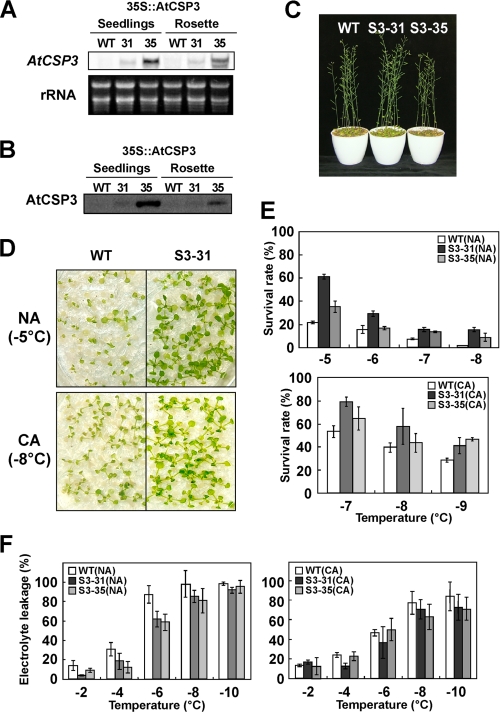

Overexpression of AtCSP3 Confers Freezing Tolerance

To analyze the effect of AtCSP3 expression on freezing tolerance, we selected two homozygous 35S::AtCSP3 transgenic lines with different transgene expression levels (Fig. 6A). The levels of AtCSP3 accumulation in the overexpression lines were higher than that of wild type (Fig. 6B). The 35S::AtCSP3 plants showed no difference in phenotype compared with wild type under normal growth conditions except for a shorter statue of the S3–35 line (Fig. 6C), which may be due to possible negative effects of highly elevated overexpression of AtCSP3 in this line. To evaluate effect of over/ectopic expression of AtCSP3 on freezing tolerance, the 35S::AtCSP3 lines and wild-type plants were exposed to freezing temperatures under non- or cold-acclimated conditions (Fig. 6, D and E). As shown in Fig. 5D, 35S::AtCSP3 transgenic plants displayed higher survival rate than wild-type plants at the freezing temperature of −5 °C (NA) and −8 °C (CA). Comparison of the survival after a range of freezing temperatures indicated both 35S::AtCSP3 lines were more freezing tolerant than wild-type under NA and CA conditions (Fig. 6E). Although the level of transgene expression did not directly correlate with the tolerance, this can be explained by the possible negative effects on plant growth caused by the extreme high expression of AtCSP3 in S3–35. Electrolyte leakage measurement also indicated that the rosette leaves of 35S::AtCSP3 plants were more freeze tolerant than wild type under cold-acclimated and non-acclimated conditions (Fig. 6F).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of AtCSP3 overexpression on freezing tolerance. Northern (A) and Western (B) blot analyses of 10-day-old seedlings and 3-week-old rosette leaves in two independent transgenic lines (S3–31 and S3–35). C, phenotypes of 5-week-old WT and AtCSP3 overexpression plants (S3–31 and S3–35). D, freezing tolerance of 2-week-old wild-type and the S3–31 line under NA and CA conditions. The photographs were taken 7 days after freezing treatment. E, survival rates for 2-week-old WT, S3–31, and S3–35 seedlings under NA and CA conditions. F, electrolyte leakage of 3-week-old rosette leaves from WT, S3–31, and S3–35.

DISCUSSION

Cold shock domain proteins have been identified in a variety of organisms ranging from bacteria to mammals. In higher plants, cold shock domain proteins are involved in the cold response and share conserved functions with bacterial CSPs (26, 27). In the current study, we have shown that the Arabidopsis AtCSP3 functions as a RNA chaperone and is involved in the acquisition of freezing tolerance.

Expression analysis indicated that the level of AtCSP3 transcripts increased in response to cold in both shoots and roots (Fig. 2, A and B), with a maximum level of expression at around 12 h of cold treatment. The fact that AtCSP3 expression was not modulated by drought, NaCl, or ABA (data not shown), suggested that AtCSP3 function is mainly associated with cold stress. The spatial expression pattern of AtCSP3 was characterized using a reporter gene fusion construct (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S2). AtCSP3 promoter-GUS expression was limited to shoot and root apical regions of vegetative plants, which are considered to be tissues that primarily sense environmental cues. The shoot apical meristem was reported to sense low temperature signals during vernalization (36, 37), whereas root tips are also known to sense environmental signals such as gravity and water availability (38). In response to cold, GUS and GFP expression was extended to a broader region of root (Fig. 2B, and supplemental Fig. S2K). Because root growth was inhibited during cold treatment, this extension was not due to cell division of GUS-expressing cells. It is thus plausible that a signal from root tip is transduced toward the basal part of root to induce expression of AtCSP3.

Transgenic expression of AtCSP3-GFP driven by the native AtCSP3 promoter revealed that AtCSP3 was localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. S2K). The nuclear and cytoplasmic localization is consistent with a role for AtCSP3 involving interaction with mRNA. Arabidopsis LOS4 encodes a DEAD-box RNA helicase and is required for efficient export of RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (39). LOS4 also localizes to the nucleus and cytoplasm, and might be important for nuclear pore remodeling under cold temperatures (39, 40). RNA helicases and RNA chaperones are involved in various steps of RNA metabolism (41). In Bacillus subtilis, CspB physically interacts with cold-induced DEAD-box RNA helicases, CshA and CshB (42). It will be interesting to determine if plant CSD proteins interact with RNA helicases.

The atcsp3-2 mutant plant was more sensitive to freezing than wild type under both NA and CA conditions (Fig. 3, D–F). A change in freezing tolerance may reflect altered expression of cold-regulated genes, however, expression analysis of CBFs and CBF regulon genes indicated that the CBF pathway is functioning normally in atcsp3-2 (Fig. 4). On the other hand, several genes were identified that were down-regulated in atcsp3-2. Most of these down-regulated genes in atcsp3-2 have been linked to stress responses (supplemental Table S1 and Fig. 5); however, it is not yet clear how they are related or their potential mechanistic role in freezing tolerance. It is interesting to note that six of the down-regulated genes in atcsp3-2 are known to be up-regulated in the ada2b-1 mutant (43). ADA2 is a histone acetyltransferase with a putative transcriptional adaptor function (43, 44). The ada2b-1 mutant is constitutively more freezing tolerant than wild-type plants without overexpressing COR genes (43), suggesting there may be a cross-talk between the AtCSP3 and ADA2. Current information suggests that AtCSP3 controls the expression of genes that are necessary for freezing tolerance but are not CBF-regulated genes. Molecular genetic analyses of several mutants such as esk1 and hos9 have indicated a significant role for such CBF-independent pathways in freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis (5, 6, 45).

The biochemical activity of AtCSP3 is very similar to that of WCSP1, unwinding dsDNA, and binding RNA and DNA (supplemental Fig. S1). In addition, AtCSP3 complemented the E. coli csp mutant (Fig. 1B). These data suggested that AtCSP3 functions as RNA chaperone in vivo. AtCSP3 may thus act to enhance translation of bulk or specific mRNA important for freezing tolerance by destabilizing RNA duplex produced under low temperature conditions. Another possibility is that AtCSP3 regulates mRNA stability by mediating RNA duplex formation, which can stabilize mRNA from exonucleolytic degradation. In bacterial systems, RNA chaperones regulate gene expression at both the transcription and post-transcription levels. Our data, together with the recent finding that bacterial CSPs can confer stress tolerance in plants (46), support a functional conservation of plant and bacterial CSD proteins in acquiring stress tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Masayori Inouye and Tsuyoshi Nakagawa for providing the E. coli BX04 strain and the pGWB4 binary vector, respectively. We also thank ABRC for supplying the mutant Arabidopsis line and Dr. Derek Goto for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Scientific Research B 19380063) and National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) (Development of Innovative Crops through the Molecular Analysis of Useful Genes 3202) (to R. I. and K. S., respectively).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1 and S2.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1 and S2.

- CA

- cold acclimation

- COR

- cold-regulated

- CA

- cold acclimation

- CSP

- cold shock protein

- CSD

- cold shock domain

- GUS

- β-glucuronidase

- MHC

- major histocompatibility complex

- mRNP

- messenger ribonucleoprotein complex

- NA

- non-acclimation

- WT

- wild type

- X-gluc

- 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sakai A., Larcher W. (1987) Frost Survival of Plants: Responses and Adaptations to Freezing Stress, Springer-Verlag, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guy C. (1990) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 41,187–223 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Q., Kasuga M., Sakuma Y., Abe H., Miura S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (1998) Plant Cell 10,1391–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaglo-Ottosen K. R., Gilmour S. J., Zarka D. G., Schabenberger O., Thomashow M. F. (1998) Science 280,104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xin Z., Browse J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95,7799–7804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu J., Shi H., Lee B. H., Damsz B., Cheng S., Stirm V., Zhu J. K., Hasegawa P. M., Bressan R. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101,9873–9878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu J., Verslues P. E., Zheng X., Lee B. H., Zhan X., Manabe Y., Sokolchik I., Zhu Y., Dong C. H., Zhu J. K., Hasegawa P. M., Bressan R. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102,9966–9971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Phadtare S., Tyagi S., Inouye M., Severinov K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277,46706–46711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phadtare S., Alsina J., Inouye M. (1999) Curr. Opin Microbiol. 2,199–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanaka K., Fang L., Inouye M. (1998) Mol. Microbiol. 27,247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber M. H., Fricke I., Doll N., Marahiel M. A. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30,375–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloks C. P., Spronk C. A., Lasonder E., Hoffmann A., Vuister G. W., Grzesiek S., Hilbers C. W. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 316,317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graumann P. L., Marahiel M. A. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci 23,286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Didier D. K., Schiffenbauer J., Woulfe S. L., Zacheis M., Schwartz B. D. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85,7322–7326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashi K., Inagaki Y., Suzuki N., Mitsui S., Mauviel A., Kaneko H., Nakatsuka I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278,5156–5162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasham A., Moloney S., Hale T., Homer C., Zhang Y. F., Murison J. G., Braithwaite A. W., Watson J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278,35516–35523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nekrasov M. P., Ivshina M. P., Chernov K. G., Kovrigina E. A., Evdokimova V. M., Thomas A. A., Hershey J. W., Ovchinnikov L. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278,13936–13943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisarev A. V., Skabkin M. A., Thomas A. A., Merrick W. C., Ovchinnikov L. P., Shatsky I. N. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277,15445–15451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss E. G., Lee R. C., Ambros V. (1997) Cell 88,637–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polesskaya A., Cuvellier S., Naguibneva I., Duquet A., Moss E. G., Harel-Bellan A. (2007) Genes Dev. 21,1125–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viswanathan S. R., Daley G. Q., Gregory R. I. (2008) Science 320,97–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J., Vodyanik M. A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J. L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G. A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., Slukvin I. I., Thomson J. A. (2007) Science 318,1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlson D., Imai R. (2003) Plant Physiol. 131,12–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlson D., Nakaminami K., Toyomasu T., Imai R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277,35248–35256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakaminami K., Sasaki K., Kajita S., Takeda H., Karlson D., Ohgi K., Imai R. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579,4887–4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakaminami K., Karlson D. T., Imai R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103,10122–10127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki K., Kim M. H., Imai R. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364,633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fusaro A. F., Bocca S. N., Ramos R. L., Barrôco R. M., Magioli C., Jorge V. C., Coutinho T. C., Rangel-Lima C. M., De Rycke R., Inzé D., Engler G., Sachetto-Martins G. (2007) Planta 225,1339–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J. S., Park S. J., Kwak K. J., Kim Y. O., Kim J. Y., Song J., Jang B., Jung C. H., Kang H. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35,506–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998) Plant J. 16,735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medina J., Bargues M., Terol J., Pérez-Alonso M., Salinas J. (1999) Plant Physiol. 119,463–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilmour S. J., Artus N. N., Thomashow M. F. (1992) Plant Mol. Biol. 18,13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin C., Thomashow M. F. (1992) Plant Physiol. 99,519–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fowler S., Thomashow M. F. (2002) Plant Cell 14,1675–1690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia B., Ke H., Inouye M. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 40,179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwabe W. W. (1954) J. Exp. Bot. 5,389–400 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtis O. F., Chang H. T. (1930) Amer. J. Bot. 17,1047–1048 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi H. (1997) J. Plant Res. 110,163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Z., Lee H., Xiong L., Jagendorf A., Stevenson B., Zhu J. K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99,11507–11512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong Z., Dong C. H., Lee H., Zhu J., Xiong L., Gong D., Stevenson B., Zhu J. K. (2005) Plant Cell 17,256–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sommerville J. (1999) Bioessays 21,319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunger K., Beckering C. L., Wiegeshoff F., Graumann P. L., Marahiel M. A. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188,240–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vlachonasios K. E., Thomashow M. F., Triezenberg S. J. (2003) Plant Cell 15,626–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stockinger E. J., Mao Y., Regier M. K., Triezenberg S. J., Thomashow M. F. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29,1524–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xin Z., Mandaokar A., Chen J., Last R. L., Browse J. (2007) Plant J. 49,786–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castiglioni P., Warner D., Bensen R. J., Anstrom D. C., Harrison J., Stoecker M., Abad M., Kumar G., Salvador S., D'Ordine R., Navarro S., Back S., Fernandes M., Targolli J., Dasgupta S., Bonin C., Luethy M. H., Heard J. E. (2008) Plant Physiol. 147,446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.