Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) has many essential functions and its homeostasis is highly regulated. We previously found that hypertonic stress increases PIP2 by selectively activating the β isoform of the type I phosphatidylinositol phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5Kβ) through Ser/Thr dephosphorylation and promoting its translocation to the plasma membrane. Here we report that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) also induces PIP5Kβ Ser/Thr dephosphorylation, but it has the opposite effect on PIP2 homeostasis, PIP5Kβ function, and the actin cytoskeleton. Brief H2O2 treatments decrease cellular PIP2 in a PIP5Kβ-dependent manner. PIP5Kβ is tyrosine phosphorylated, dissociates from the plasma membrane, and has decreased lipid kinase activity. In contrast, the other two PIP5K isoforms are not inhibited by H2O2. We identified spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), which is activated by oxidants, as a candidate PIP5Kβ kinase in this pathway, and mapped the oxidant-sensitive tyrosine phosphorylation site to residue 105. The PIP5KβY105E phosphomimetic is catalytically inactive and cytosolic, whereas the Y105F non-phosphorylatable mutant has higher intrinsic lipid kinase activity and is much more membrane associated than wild type PIP5Kβ. These results suggest that during oxidative stress, as modeled by H2O2 treatment, Syk-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PIP5Kβ is the dominant post-translational modification that is responsible for the decrease in cellular PIP2.

Oxygen-derived free radicals are by-products of metabolic reactions in eukaryotic cells. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)4 act as endogenous signaling molecules (1). However, excessive ROS production leads to deleterious effects on cellular homeostasis by inducing DNA damage, lipid/protein oxidation, and ultimately apoptosis or necrosis. Acute and chronic oxidative stress have been implicated in the pathophysiology of shock and sepsis associated with traumatic injuries such as massive thermal burn (2–4), Alzheimer disease, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis (5–7).

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) has emerged as an integral component of the stress response. This is concordant with its essential role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, endocytosis, exocytosis, plasma membrane (PM) scaffolding, and ion channels/transporter (8). PIP2 is also essential for InsP3-mediated Ca2+ generation, protein kinase C activation, and PIP3 generation (9, 10). PIP2 synthesis is depressed in the heart sarcolemma during oxidative stress, suggesting that PIP2 depletion may contribute to cardiac dysfunctions (11). Recently, Divecha and colleagues (12) reported that prolonged (many hours) treatment of HeLa cells with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) induces apoptosis by depleting PIP2. Apoptosis can be attenuated by overexpression of a type I phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase (PIP5Kβ). We found using isoform-specific PIP5K knockdown by RNA interference (RNAi) that PIP5Kβ synthesizes a large fraction of the ambient PIP2 pool in HeLa cells (13). Hypertonicity is another type of stress that increases PIP2 and may be protective against cell injury (14, 15) by activating PIP5Kβ through Ser/Thr dephosphorylation (16). This effect is specific for PIP5Kβ, because depletion of the other two PIP5K isoforms (α and γ) individually does not substantially abrogate the hypertonicity induced PIP2 increase.

In the present study, we used H2O2 to model oxidative stress in tissue culture cells, and examined the effect on PIP2 homeostasis and PIP5Kβ function. We found that a brief H2O2 treatment decreases cellular PIP2 and inactivates PIP5Kβ through tyrosine phosphorylation. We identified spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) as a candidate kinase in this pathway. Syk is a member of the Syk/Zap-70 nonreceptor tyrosine kinase family that is abundant in hematopoietic cells (17) but is also found in nonhematopoietic lineages (18), including HeLa and COS cells (19, 20).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

PIP5K and Syk Overexpression

The mouse and human β and α isoform designations are reversed. In this paper, we will follow the recent GenBankTM guideline to use the human isoform designation (8). Myc- or HA-tagged PIP5Kα, -β, and -γ87 were generated as described previously (21). Untagged, HA- or Myc-tagged human Syk were cloned into the pCMV5 vector. A Myc-dominant negative (DN) Syk construct containing the Syk SH2 domains but not the kinase domain (amino acids 1–261) was generated as described in Ref. 22.

Cell Culture

HeLa and COS cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mm HEPES, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2.

Antibodies and Other Reagents

The antibodies used and their sources are as follows: monoclonal anti-(α)-c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-70), α-phosphotyrosine (α-Tyr(P), Santa Cruz, sc-7020), monoclonal α-HA (Covance), monoclonal α-actin (Sigma, A4700), and α-Syk (Santa Cruz, sc-1077). FITC-labeled phalloidin was purchased from Sigma (p-5282). All tyrosine kinase inhibitors were from Calbiochem. All other chemicals were from Sigma, unless otherwise indicated.

Oxidative Stress and Inhibitor Treatment

Cells were treated with H2O2 or pervanadate (PV). In some experiments, cells were preincubated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for 30 min before stimulation.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Lipids were extracted, deacylated, and analyzed on anion exchange HPLC columns (23, 24). Individual peaks were identified with glycerophosphoryl inositol standards.

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

Cells were labeled for 4 h in phosphate-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and 40 μCi/ml of [32P]orthophosphate (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Samples were processed by chloroform:methanol extraction and lipids were separated by TLC (25). Fluorograms were obtained using a PhosphorImager.

RNAi

The small interfering RNA sequences targeting human PIP5Kβ were transfected to HeLa cells as described previously (13, 16). Firefly luciferase small interfering RNA (nucleotides 695–715) was used as a control. 48 h later, cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and stimulated with H2O2. Because we were not able to detect endogenous PIP5Kβ in HeLa cells with the currently available antibodies, reverse transcriptase-PCR was used to assess the extent of PIP5Kβ knockdown, as described in Ref. 26.

Immunoprecipitation

HeLa or COS cells overexpressing tagged PIP5K or Syk were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (16) and incubated with α-Myc or α-HA antibody followed by Protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) to pull down the respective epitope-tagged proteins.

In Vitro Lipid Kinase Assay

Lipid kinase activity was measured by the phosphorylation of PI4P containing micelles, using [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer) as a phosphate donor and immunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5K as the enzyme (16). The Protein G-Sepharose beads containing immunoprecipitated PIP5K were washed twice in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 1% Triton X-100) and then twice in kinase buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1 m NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol). Half of the sample was used for Western blot analysis to determine the amount of PIP5K. The other half was resuspended in 40 μl of kinase buffer containing 50 μm PI4P micelles. Substrate was generated by bath sonication of 70 μm PI4P (Avanti) and 35 μm phosphatidylserine (Avanti) in the lipid kinase buffer described above. The lipid kinase reaction was started by the addition of an ATP mixture (0.1 mm ATP, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and 15 mm MgCl2) to a final volume of 50 μl. The reaction was terminated by 80 μl of 1 n HCl after 5–20 min at room temperature. Lipids were extracted with chloroform:methanol and analyzed by TLC. Lipid kinase activity in the linear range was normalized against the amount of immunoprecipitated PIP5K used.

In Vitro Protein Phosphorylation Assay

COS cells were transfected with Myc-PIP5K or untagged Syk individually. In some samples, Syk-transfected cells were exposed to H2O2. PIP5K or Syk were immunoprecipitated by incubation with α-Myc or α-Syk antibody, respectively, at 4 °C overnight in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein G-Sepharose beads were then added. After 1 h at 4 °C, beads containing PIP5K or Syk were washed and mixed together, and 2 μm ATP was added to initiate in vitro protein phosphorylation. After 20 min at room temperature, samples were centrifuged for 20 s at 17,000 × g and proteins bound to the beads were subjected to Western blotting with α-Tyr(P) and α-Myc. In some cases, piceatannol was added to the immunoprecipitated Syk prior to mixing with immunoprecipitated PIP5K.

PIP5Kβ Tyrosine Phosphorylation Mutant

Potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites were identified using the NetPhos program. Point mutations were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The C-terminal truncation mutant was generated by subcloning.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence labeling was performed as described previously (16). Images were captured on an Axiovert 100M/LSM Meta 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). In some experiments, images from random fields were analyzed by eye in a blinded fashion, to distinguish between cells with normal long actin stress fibers, versus those with abnormal short actin filaments.

Actin Pool Assay

Cells were extracted with a buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 20 mm PIPES, 40 mm KCl, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitors and subjected to differential centrifugation to isolate the Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions (16, 27).

Multistep PM Fractionation

The procedure was as described in Ref. 28. Cells were lysed by Dounce homogenization in a buffer containing 250 mm sucrose, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitors. Unbroken cells and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min to obtain the post-nuclear fraction. The supernatant was centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The high speed supernatant was collected and referred to as the cytosolic fraction (Cyt). The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of homogenization buffer and overlaid onto a 0.8-ml cushion of 1.12 m sucrose. After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h, the PM-enriched layer at the top of the sucrose cushion was collected with a syringe and centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet (referred to as “PM”) was re-suspended in sample buffer, boiled, and analyzed on SDS-PAGE in parallel with the Cyt fraction.

One-step Microsome Fractionation

Cells were lysed by Dounce homogenization. Lysates were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min to obtain a postnuclear fraction. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 min to separate microsomes from the cytosolic fraction. Samples were analyzed by Western blot.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± S.E. A two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups, and a one-way analysis of variance was used to compare values among the treatments using the Sigma Plot software. Significant differences among the treatment groups were assessed by post hoc analysis (multiple comparisons versus control group was done with the Dunnett's method; pairwise multiple comparison procedures were done with the Holm-Sikak method). Significance was determined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Short Term H2O2 Treatment Perturbs Phosphoinositide Homeostasis

After a 20-min exposure to 0.3 or 0.5 mm H2O2, HeLa cells had a small but statistically significant dose-dependent decrease in total PIP2 and a large increase in PIP (Fig. 1A). HPLC analyses, which can distinguish between many of the PIP2 and PIP isomers, confirmed that PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) was decreased and PI4P was increased (Fig. 1B). Similar responses were observed in COS cells (data not shown).

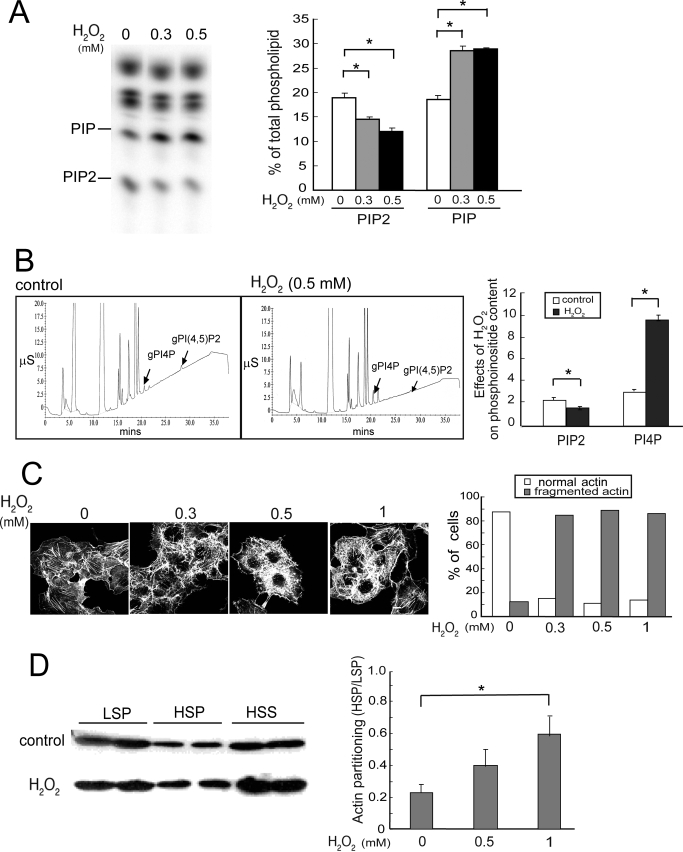

FIGURE 1.

H2O2 disrupts phosphoinositide homeostasis and the actin cytoskeleton. Cells were treated without (Control) or with H2O2 for 20 min unless otherwise indicated. A, TLC. HeLa cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and exposed to H2O2. 32P-Labeled lipids were analyzed by TLC and PhosphorImager analysis. Left, a typical fluorogram of 32P-labeled lipids after separation by TLC; right, quantitation of 32P-labeled lipids (mean ± S.E., n = 3). Amounts of [32P]PIP2 and PIP were expressed as a percentage of the total labeled phospholipids. Asterisks denote statistically significant compared with control, with p < 0.05, in this and all other panels in this figure. B, HPLC. HeLa cells were exposed to 0 or 0.5 mm H2O2 and lipids were extracted. Phospholipids were deacylated and negatively charged glycerol head groups were eluted and detected with suppressed conductivity (μS, microsiemen units). Left, HPLC elution profiles; right, quantitation (mean ± S.E., n = 3). C, actin cytoskeleton. COS cells were fixed and stained with FITC-phalloidin to detect polymerized actin fibers. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. Left, representative images; right, scoring of actin morphology in cells from 10 randomly chosen fields per condition in a blinded fashion. The percentage of cells with normal long or abnormal actin stress fibers were plotted. 40–50 cells were analyzed per condition. D, partitioning of actin in Triton-soluble and -insoluble fractions. HSS, high speed supernatant. Left, Western blot of a representative experiment. Two samples from each condition are shown, and the amount of high speed supernatant loaded is half as much as that in the LSP and HSP; right, ratios of actin in HSP/LSP fractions. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

The H2O2-induced perturbation in PIP2 and PI4P homeostasis was blocked by pretreating cells with the free radical scavenger glutathione (GSH), but not by its inactive oxidized form, GSSH (data not shown). These results suggest that the phosphoinositide changes are due to oxidative stress. In this article, we will focus on the mechanisms by which H2O2 induce PIP2 decrease.

H2O2 Treatment Disrupts the Actin Cytoskeleton

PIP2 is an important regulator of the actin cytoskeleton (8, 29). We have previously shown that hypertonic stress increased PIP2 synthesis and induced actin polymerization and stress fiber assembly (25). Here, we determined if a drop in PIP2 during oxidative stress may have the opposite effect on the actin cytoskeleton. Cells treated with H2O2 were stained with FITC-labeled phalloidin (Fig. 1C). Confocal microscopy showed that the long central parallel actin stress fibers were replaced by shorter and disordered actin filaments, whereas cortical actin staining was less obviously affected. The results were reproducible in two separate experiments.

We employed differential centrifugation after Triton X-100 extraction to determine whether actin partitioning was altered (Fig. 1D). The amount of actin recovered in the low speed pellet (LSP), which contains highly cross-linked actin filaments (such as stress fibers and cortical actin networks), was decreased, whereas that in the high speed pellet (HSP), which contains polymerized actin that is not highly cross-linked, increased (Fig. 1D, left panel). The amount of actin in the high speed supernatant, which contains actin monomers and small oligomers, was relatively unchanged. As a consequence, the ratio of actin in HSP versus LSP increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1D, right). Statistical analysis showed that the extent of increase was not statistically significant after treatment with 0.5 mm H2O2, but was highly significant after treatment with 1 mm H2O2. Because even 0.3 mm H2O2 reproducibly generated fragmented actin filaments when examined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1C), the lack of statistical significance at 0.5 mm H2O2 in the differential sedimentation experiment (Fig. 1D) may be because some of the shortened filaments were still sufficiently cross-linked to be sedimented by low speed centrifugation. Taken together, our results suggest that H2O2 does not induce net actin depolymerization per se, but causes actin filament shortening and stress fiber disorganization.

PIP5Kβ Is Tyrosine Phosphorylated during Oxidative Stress

It is well established that oxidative stress promotes tyrosine phosphorylation by inhibiting tyrosine phosphatases (30). We therefore tested the effects of the potent tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, PV, on phosphoinositide homeostasis in HeLa cells. PV mimicked the effects of H2O2 by decreasing PIP2 and increasing PI4P (Fig. 2A).

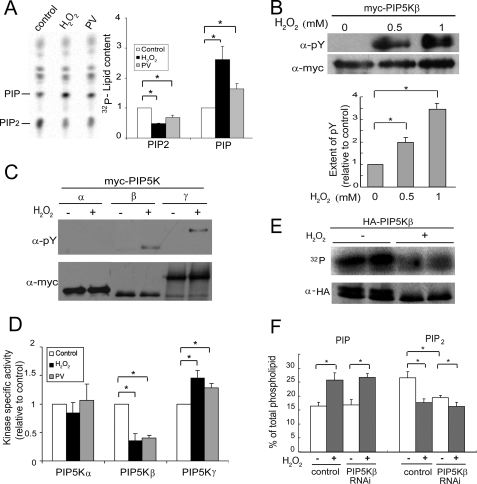

FIGURE 2.

H2O2 induces PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation and decreases its lipid kinase activity. A, PV and H2O2 have similar effects on phosphoinositide homeostasis. HeLa cells labeled with [32P]orthophosphate were treated with either 1 mm H2O2 or 10 μm PV for 15 min. Lipids were extracted and resolved by TLC. Left, fluorogram; right, quantitation. The amount of PIP2 or PIP in the control sample was set as 1. B, PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation. COS cells transfected with Myc-PIP5Kβ were exposed to 0.5 or 1 mm H2O2 for 20 min. Myc-PIP5Kβ was immunoprecipitated and Western blotted with α-Myc and α-Tyr(P). Top, Western blots; bottom, quantitation of tyrosine phosphorylation. The ratio of α-Tyr(P) to α-Myc PIP5Kβ intensity in the absence of H2O2 is set as 1. Values shown are mean ± S.E., n = 3. Asterisks denote statistically significant compared with control, with p < 0.05, in this and all other panels in this figure. C, H2O2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PIP5Kβ and γ87, but not PIP5Kα. Cells were incubated with 1 mm H2O2 for 15 min. D, H2O2 has differential effects on the lipid kinase activity of the three PIP5K isoforms. COS cells transiently transfected with Myc-PIP5K isoforms were exposed to either 1 mm H2O2 or 10 μm PV for 15 min. Immunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5Ks were used in an in vitro lipid kinase assay and their activity in the linear range was normalized against the amount of immunoprecipitated kinase. The specific activity (mean ± S.E., n = 3) of each control untreated PIP5K isoform was set as 1. E, H2O2 also induces PIP5Kβ Ser/Thr dephosphorylation. COS cells expressing HA-PIP5Kβ were labeled with 32P and exposed to 1 mm H2O2. Immunoprecipitated HA-PIP5Kβ was subjected to SDS-PAGE. 32P-Labeled proteins were detected by PhosphorImager and total HA-PIP5Kβ was detected by Western blotting. Data shown are representative of those from two independent experiments. F, effects of PIP5Kβ depletion by RNAi on the H2O2-induced decrease in PIP2. HeLa cells were transfected with small interfering RNA oligonucleotides targeting PIP5Kβ or firefly luciferase (negative control). Cells were stimulated with H2O2 (0.5 mm, 15 min), and 32P incorporation into PIP and PIP2 was quantitated after TLC. The amount of [32P]phosphoinositide was expressed as a percentage of total labeled phospholipids. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 7 from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

PIP2 homeostasis is maintained by the balance between its synthesis and degradation. Because PIP5Kβ accounts for most of the ambient PIP2 pool in HeLa cells (13), we examined the possibility that the decrease in total PIP2 in oxidatively stressed cells was due to PIP5Kβ inactivation by tyrosine phosphorylation. PIP5Kβ was tyrosine phosphorylated after treatment with 0.5 mm H2O2 and the extent of phosphorylation increased further at 1 mm H2O2 (Fig. 2B). In addition, PIP5Kγ87 was also tyrosine phosphorylated, whereas PIP5Kα was not (Fig. 2C). PIP5Kγ90, a splice variant that contains 28 additional amino acid residues at the COOH-terminal tail compared with PIP5Kγ87, was tyrosine phosphorylated as well (data not shown).

We next examined the effect of H2O2 or PV on the activity of these lipid kinases. Overexpressed Myc-tagged PIP5Ks were immunoprecipitated from cells treated with or without H2O2 or PV and used for in vitro lipid kinase assay (Fig. 2D). PIP5Kβ showed a significant drop in activity. PIP5Kα activity was not significantly affected, as would be consistent with its lack of tyrosine phosphorylation. In contrast, PIP5Kγ87, which was also tyrosine phosphorylated, had increased activity. Taken together, our results suggest that oxidative stress selectively represses PIP5Kβ activity by tyrosine phosphorylation, and this inhibition could account for the PIP2 decrease in oxidant-stressed cells. Although PIP5Kγ enzymatic activity is increased, it may not be able to compensate for the PIP5Kβ-induced decrease in the ambient PIP2 pool because PIP5Kγ accounts for a much smaller fraction of the total pool (13).

PIP5Kβ Is Also Ser/Thr Dephosphorylated during Oxidative Stress

PIP5Kβ is constitutively Ser/Thr phosphorylated (31, 32), and is dephosphorylated in response to hypertonic stress (16). We therefore examined the effect of ROS on PIP5Kβ Ser/Thr phosphorylation. H2O2 decreased 32P incorporation into PIP5Kβ (Fig. 2E), despite tyrosine phosphorylation. Western blots confirmed that there was significant overall dephosphorylation. HA-PIP5Kβ, which under favorable conditions migrated as a doublet (16), lost the upper hyperphosphorylated band after H2O2 treatment. Results shown are representative of two independent 32P and Western blot experiments. A similar collapse of the doublet was reported previously after exposure to hypertonic saline (16). Thus, PIP5Kβ is simultaneously Ser/Thr dephosphorylated and tyrosine phosphorylated after H2O2 treatment. The conundrum of why PIP5Kβ activity is inhibited despite Ser/Thr dephosphorylation can be explained by postulating that the inhibitory effect of tyrosine phosphorylation overrides activation by Ser/Thr dephosphorylation to generate an inhibited molecule.

PIP5Kβ Depletion Decreases Ambient PIP2 and Blunts Further PIP2 Decrease by H2O2

To evaluate the contribution of PIP5Kβ to the H2O2-induced PIP2 response, we used RNAi to partially deplete endogenous PIP5Kβ. RNAi decreased PIP5Kβ mRNA to 44 ± 8.4% (p < 0.007, n = 4) of the control level (data not shown) and ambient PIP2 pool to 72% of control (Fig. 2F). These values are consistent with those described previously (13, 16). H2O2 treatment decreased PIP2 by 16 and 33% in PIP5Kβ and control RNAi-treated cells, respectively. Thus, there is a 53% decrease in the PIP2 response; the residual response is likely to be due to residual PIP5Kβ incomplete knockdown. Our results suggest that the oxidant-induced PIP2 decrease can be attributed primarily to inhibition of PIP5Kβ. In contrast, PIP5Kβ depletion had no effect on the PIP response, suggesting that the increase in PIP is not related to the decrease in PIP2, and that the cells were able to respond to H2O2.

Oxidative Stress Decreases PIP5Kβ Association with the PM

PIP5Kβ is a cytosolic protein that is partially PM-associated (13, 25, 33). Using immunofluorescence, we found that H2O2 treatment decreased PIP5Kβ at the cell periphery (Fig. 3A). This was confirmed biochemically by isolating PM-enriched fractions. H2O2 treatment decreased the amount of Myc-PIP5Kβ recovered in the PM fraction by ∼65% (Fig. 3B). Western blotting with an α-phosphotyrosine (Tyr(P)) antibody showed that there is a preferential enrichment of tyrosine-phosphorylated PIP5Kβ in the cytosol fraction after PV treatment (Fig. 3C). Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation promotes PIP5Kβ dissociation from membranes.

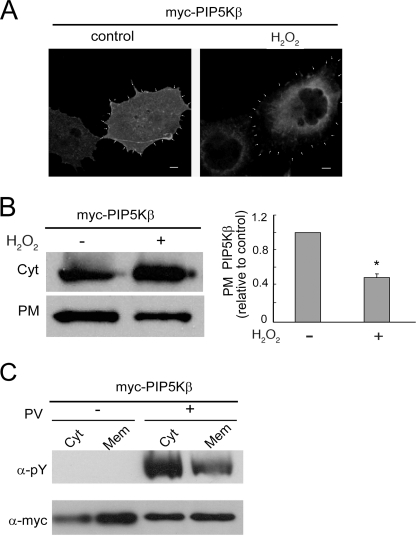

FIGURE 3.

H2O2 decreases PIP5Kβ membrane association. COS cells overexpressing Myc-PIP5Kβ were exposed to 1 mm H2O2 or 10 μm PV for 15 min. A, immunofluorescence localization. Cells were stained with α-Myc/FITC. The periphery of the cell, based in cortical phalloidin actin staining (not shown), is outlined by arrowheads. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, decrease in PIP5Kβ association with a PM-enriched fraction. Cell homogenates were subjected to sequential multistep centrifugation. The PM-enriched and cytosolic (Cyt) fractions were blotted with α-Myc. Left, Western blot; right, change in PM-associated Myc-PIP5Kβ. The ratios of PM/PM + Cyt Myc-PIP5Kβ were plotted (mean ± S.E., n = 3), relative to that of the untreated control set as 1. Asterisk denotes statistically significant, with p < 0.05. C, preferential decrease in tyrosine-phosphorylated Myc-PIP5Kβ from microsome membranes. Cytosol (Cyt) and microsome membranes (Mem) from PV-treated cells were separated and blotted with α-Tyr(P) and α-Myc. The Tyr(P)/Myc ratios are 3.54 and 1.86 for Cyt and Mem from H2O2-treated cells. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

Syk Phosphorylates PIP5Kβ

We employed a pharmacological screen to identify potential candidate tyrosine kinase(s) that phosphorylate(s) PIP5Kβ. Cells transfected with Myc-PIP5Kβ were preincubated with different tyrosine kinase inhibitors for 15 min before PV stimulation. The inhibitors (their primary targets and doses used) were as follows: G957 (a Bcr/Abl inhibitor, 100 μm), AG1296 (a platelet-derived growth factor inhibitor, 10 μm), AG1478 (an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, 30 nm), PP2 (a Src family kinase inhibitor, 100 nm), and piceatannol (a Syk inhibitor, 100 μm). Most of the inhibitors tested had no effect on PV-induced PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation even when used at a minimum of 10 times of their estimated IC50 (data not shown). Among these, only PP2 and piceatannol decreased PV-induced PIP5Kβ phosphorylation (data not shown). They also decreased H2O2-induced PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation, but not basal phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). Syk is activated downstream of the Src family kinases during oxidative stress (34) and is inhibited by piceatannol with an in vitro IC50 of ∼25 μm (35). Therefore, complete inhibition of H2O2-induced PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation by 60 μm piceatannol strongly implicates Syk in PIP5Kβ regulation and disruption of PIP2 homeostasis by H2O2. We performed additional experiments to evaluate this possibility.

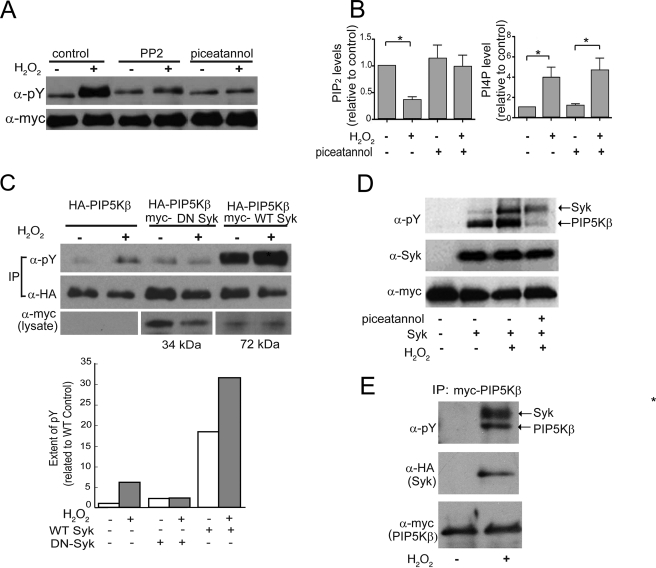

FIGURE 4.

PIP5Kβ is tyrosine phosphorylated by Syk in vivo and in vitro. COS cells (unless indicated otherwise) were transfected with epitope-tagged PIP5Kβ and Syk, and stimulated with 1 mm H2O2 for 15 min, with or without prior incubation for 30 min with protein kinase inhibitors. A, effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cells were pretreated with 80 nm PP2 or 60 μm piceatannol prior to H2O2 stimulation. Immunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5K was Western blotted with α-Tyr(P) and α-Myc. B, effects of piceatannol on H2O2-induced PIP2 (left) and PIP (right) responses. 32P-Labeled HeLa cells were pretreated with 60 μm piceatannol or vehicle prior to H2O2 stimulation. 32P-Labeled lipids were analyzed by TLC and quantitated. PIP2 and PI4P levels (mean ± S.E., n = 3) were expressed relative to that of mock-treated control, whose value was set as 1. Asterisks denote statistically significant, with p < 0.05. C, effects of WT and DN Syk on the tyrosine phosphorylation of coexpressed PIP5Kβ. HA-PIP5Kβ was immunoprecipitated and blotted with α-Tyr(P) or α-HA antibody. Expression of DN Syk (34 kDa) and WT Syk (72 kDa) was confirmed by Western blotting of the lysates. Top, Western blot from a representative experiment (out of two performed); bottom, the ratios of tyrosine phosphorylation of the H2O2-treated versus untreated samples are indicated. Note that the actual extent of phosphorylation in the WT Syk-transfected sample is 18 times more than that without transfected Syk, in the absence of H2O2. D, Syk phosphorylates PIP5Kβ in vitro. Immunoprecipitated Syk was mixed with separately immunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5Kβ in the presence of ATP. Tyrosine phosphorylation was detected with α-Tyr(P) antibody. H2O2 was added to Syk expressing cells prior to immunoprecipitation. Piceatannol was added to the immunoprecipitated Syk prior to mixing with the immunoprecipitated PIP5Kβ. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. E, H2O2 promotes Syk association with PIP5Kβ. Cells were co-transfected with HA-Syk and Myc-PIP5Kβ. Myc-PIP5Kβ was immunoprecipitated (IP) with α-Myc and subjected to Western blotting. HA-Syk was expressed at similar levels under all conditions (data not shown). Coimmunoprecipitation data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

First, piceatannol, which inhibited H2O2-induced PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation, also prevented the H2O2-dependent decrease in cellular PIP2 (Fig. 4B, left panel). Thus, Syk-mediated PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation is linked to the oxidant-induced PIP2 decrease in cells. Significantly, piceatannol had little effect on the H2O2-induced increase in PI4P (Fig. 4B, right panel). Thus, although PI4P is the obligatory substrate for PIP2 synthesis by type I PIP5Ks, its increase in response to ROS is independent of a decrease in its utilization for PIP2 synthesis.

Second, overexpressed WT Syk increased PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation under basal conditions and phosphorylation was further increased by H2O2 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, DN Syk blocked H2O2-induced tyrosine phosphorylation, establishing that endogenous Syk is likely to be responsible for the oxidant-induced PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation.

Third, Syk phosphorylated PIP5Kβ in vitro (Fig. 4D). Western blotting with α-Tyr(P) showed that Syk and Myc-PIP5Kβ were both tyrosine phosphorylated in vitro and phosphorylation was further increased by activating Syk by treating cells with H2O2 prior to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4D). Piceatannol added to the kinase reaction mixture containing immunoprecipitated Syk and PIP5Kβ blocked PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation in vitro. Piceatannol only partially inhibited Syk tyrosine phosphorylation, presumably because Syk was already tyrosine phosphorylated prior to immunoprecipitation, and only further autophosphorylation was inhibited by piceatannol added in vitro.

Fourth, pulldown assays showed that immunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5Kβ associated with HA-Syk in an H2O2-dependent manner (Fig. 4E). This interaction was specific because HA-Syk was not precipitated in the absence of Myc-PIP5K (data not shown). Similar results were obtained using the opposite strategy of immunoprecipitating HA-Syk to detect associated Myc-PIP5Kβ (Fig. 6B). Taken together, this series of experiments show that PIP5Kβ is a bona fide Syk substrate and that Syk is activated by ROS to phosphorylate PIP5Kβ.

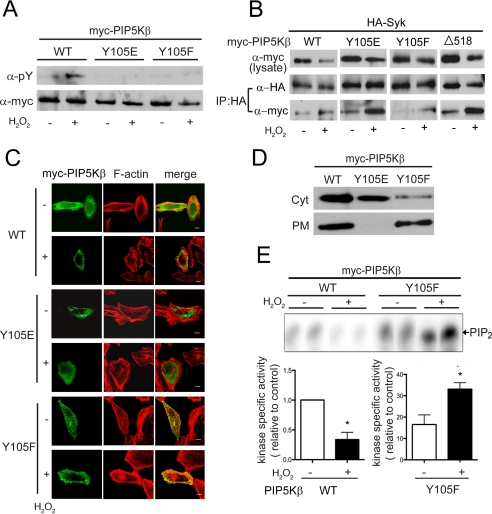

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of the PIP5KβY105 mutants. Cells transfected with WT or mutant PIP5Kβ were exposed to 1 mm H2O2 for 15 min. A, tyrosine phosphorylation. Myc-PIP5Kβs immunoprecipitated from COS cells were blotted with α-Tyr(P) and α-Myc. Data shown are representative of at least three experiments. B, association with Syk. COS cells were cotransfected with HA-Syk and Myc-PIP5Kβ. HA-Syk was immunoprecipitated and coimmunoprecipitated Myc-PIP5Kβ was detected by Western blotting. Data shown are representative of at least three experiments. C, subcellular distribution. HeLa cells overexpressing PIP5K WT or mutants were fixed and stained with α-Myc/FITC and TRITC-phalloidin (F-actin). Scale bars, 10 μm. D, membrane association. The PM-enriched and cytosolic (Cyt) fractions from COS cells were blotted with α-Myc. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. E, in vitro lipid kinase activity. PIP5Kβ WT and Y105F were immunoprecipitated from control or H2O2-treated COS cells and assayed for lipid kinase activity in vitro. 32P-Labeled PIP2 were quantified after separation by TLC. Top, fluorogram from a representative experiment. Bottom, specific activity of the lipid kinases, calculated by normalizing the amount of [32P]PIP2 generated (in the linear range of the reaction) relative to the amount of Myc-PIP5Kβ used. The value for WT was defined as 1. Values shown are mean ± S.E. (n = 3).Asterisks denote statistically significant, with p < 0.05. Note the different scales used for the WT and Y105F samples. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

Mapping the PIP5Kβ Tyrosine Phosphorylation Site

The PIP5Kβ sequence was analyzed with the NetPhos software to identify sites with high likelihood of phosphorylation. Tyrosines at positions 21, 105, 209, 239, 285, 498, 518, and 538 in PIP5Kβ were scored the highest as possible candidates (Fig. 5A). These residues were individually mutated to alanine (A) and coexpressed with Syk (Fig. 5B). A C-terminal truncation mutant was also generated (denoted by Δ). The Y105A and Δ518 (lacking residues 518–539) mutants were less phosphorylated by Syk (Fig. 5B).

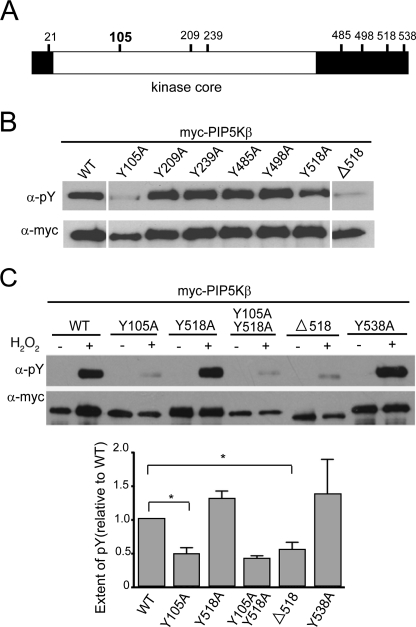

FIGURE 5.

Identification of the H2O2/Syk-dependent PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation site(s). A, map of potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites in PIP5Kβ. PIP5Kβ (human isoform designation used here; equivalent to mouse PIP5Kα) has 540 residues and its kinase core spans residues 26 to 398. Potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites predicted by the NetPhos program are indicated. Tyr-105 (bold) is identified as the bona fide phosphorylation site in this paper. B, tyrosine phosphorylation of PIP5Kβ mutants in COS cells overexpressing Syk. Point or truncated mutants were coexpressed with Syk in COS cells and immunoprecipitated. The immunoprecipitates were blotted with α-Tyr(P) and α-Myc. The images shown were assembled from a single Western blot in which 4 lanes were removed. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. C, response of PIP5Kβ mutants to H2O2, in the absence of overexpressed Syk. PIP5Kβ mutants were immunoprecipitated from COS cells and immunoblotted. Top, Western blot of a representative experiment. Bottom, relative extent of tyrosine phosphorylation. The intensity of the α-Tyr(P) band was normalized against that of the α-Myc band. The response of WT PIP5Kβ (extent of Tyr(P)) is defined as 1. Data from three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.) are shown in the lower panel. Asterisks denote statistically significant, with p < 0.05. Error bars indicate S.E.M.

Similar results were obtained after cells without transfected Syk were stimulated with H2O2 (Fig. 5C). PIP5KβY105A and Y105F (phenylalanine (F), which is sterically more similar to tyrosine) were much less tyrosine phosphorylated than the WT enzyme (Figs. 5C and 6A). Thus, Tyr-105 is the physiologically relevant oxidant-sensitive site.

We investigated why Δ518 is not tyrosine phosphorylated. We mutated the only two tyrosine residues (Tyr-518 and Tyr-538) in the deleted tail individually to alanines in the context of the full-length protein, and found that these mutants were still tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, the tail spanning residues 518–539 is not phosphorylated per se. Furthermore, the lack of phosphorylation of PIP5KβΔ518 is not due to an inability to interact with Syk, because it coimmunoprecipitated with Syk in pulldown experiments (Fig. 6B).

Functional Characterization of PIP5KβY105 Mutants

We generated Y105E as a phosphomimetic and another nonphosphorylatable mutant Y105F to evaluate the relationship between tyrosine phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and altered behavior. As expected, compared with WT PIP5Kβ, these mutants were less tyrosine phosphorylated after H2O2 stimulation (Fig. 6A). However, like WT PIP5Kβ, both still coimmunoprecipitated with Syk in an H2O2-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). Thus, their lack of phosphorylation was due to mutation of the phosphorylation site per se and not to altered interaction with Syk.

Significantly, these mutants were functionally altered. Unlike WT PIP5Kβ, the Y105E mutant appeared to be predominantly cytosolic, whereas the Y105F mutant was much more PM associated (Fig. 6, C and D). Furthermore, the latter was still strongly PM associated after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 6C). These mutants also had significantly altered lipid kinase activities. PIP5KβY105E was essentially catalytically inactive (data not shown). PIP5KβY105F had much higher basal activity than the WT enzyme and its activity increased further after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 6E). The low activity of the Y105E mutant was unlikely to be due to nonspecific protein denaturation, because both PIP5KβY105E and Y105A are soluble and associate with Syk. Therefore, these results establish that PIP5Kβ is potently inhibited by tyrosine phosphorylation.

In addition, low level PIP5KβY105F overexpression induced a loss of actin stress fibers and accumulation of vesicular actin staining even in the absence of H2O2 treatment (Fig. 6C). This phenotype is similar to that previously reported at much higher levels of overexpression of WT PIP5Kβ (21, 36). The dramatic effect of PIP5KβY105F on the actin cytoskeleton and abnormal accumulation of actin-coated vesicles in the cytoplasm can be explained by its much higher catalytic activity than the WT PIP5Kβ.

DISCUSSION

ROS are endogenous signaling molecules that become destructive when they overwhelm the antioxidant defense in the cellular milieu. For example, massive thermal burn coupled with subsequent septic complications is associated with acute escalation of oxidant and inflammatory stimuli that precipitate multiple organ failure (3). In addition, excessive ROS are released under chronic inflammatory conditions that have been implicated in the progression of diabetic and neurodegenerative diseases (6, 7).

The mechanisms of oxidant-induced injury are unclear, but breakdown of the actin cytoskeleton and consequent breaching of the endothelial barrier is likely to be causative (3). PIP2, an important regulator of the actin cytoskeleton (29), is decreased during oxidative stress (11, 12), raising the possibility that reduction in PIP2 may contribute to cytoskeletal dysfunction. In addition, because PIP2 also regulates membrane trafficking, ion channels/transporter activity, and is an obligatory precursor for at least three important signaling molecules (PIP3, diacylglycerol, and InsP3), a decrease in PIP2 can have profound effects on the cell.

Here we show that acute oxidant stress, induced by addition of low concentrations of H2O2 for 15–20 min to cells in culture, disrupts phosphoinositide homeostasis by increasing PI4P and decreasing PIP2 levels. RNAi studies showed that the PIP2 decrease is dependent on PIP5Kβ. Furthermore, the PIP2 decrease, but not the PI4P increase, is mitigated by piceatannol, a Syk inhibitor that inhibits PIP5Kβ tyrosine phosphorylation. Using a variety of approaches, including in vitro phosphorylation, coimmunoprecipitation, and overexpression of WT and DN Syk, we establish for the first time that Syk is an excellent candidate for PIP5Kβ tyrosine kinase during H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Additional studies will be required to determine whether Syk-dependent PIP5Kβ regulation also depresses PIP2 during physiologically induced oxidative stress.

Syk is a member of the Syk/Zap-70 protein-tyrosine kinase family that was originally identified in the hematopoietic cell, but has recently also been found in epithelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and neurons (18–20). In immune cells, Syk is an essential component of the machinery that signals through immune receptors, including the B-cell antigen receptor and the FcγR (17, 37). It also has a crucial role in ROS-activated signaling in B lymphocytes (17, 34). Activated Syk is autophosphorylated to initiate the recruitment of multiple downstream players. Our finding that Syk and PIP5Kβ association is enhanced by H2O2 suggests that PIP5Kβ is an integral component of the ROS signaling cascade.

In nonhematopoietic cells, Syk has also been implicated in the endocytic entry of Shiga toxin and as a tumor suppressor or promoter in several types of cancer (38, 39). It is not known how Syk alters membrane transport and tumor progression. Because PIP5Kβ is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis in HeLa cells (33), it is intriguing to speculate that Syk phosphorylation of PIP5Kβ may regulate the dynamics of endocytosis. In addition, Syk inactivation of PIP5Kβ may induce apoptosis by decreasing PIP2 generation and disrupting the actin cytoskeleton.

Paradoxically, although all three PIP5K isoforms have a highly homologous central kinase domain, and conserved a tyrosine residue at 105 equivalents, they nevertheless, respond very differently to oxidative stress. Unlike PIP5Kβ, PIP5Kγ87, which is also tyrosine phosphorylated during oxidative stress, is activated rather than inhibited. We do not know why PIP5Kγ and -β have opposite responses to ROS. One possibility is that PIP5Kγ is phosphorylated at other tyrosine residues that are dictated by its unique N- and C-terminal extensions. This possibility is consistent with our finding that the C-terminal tail of PIP5Kβ is required for phosphorylation of the upstream Tyr-105. Additional studies will be required to determine how the extension regulates phosphorylation at the kinase core. Unexpectedly, PIP5Kα is not tyrosine phosphorylated under similar conditions despite having a higher degree of sequence similarity to PIP5Kβ than PIP5Kγ. One potential explanation is that the equivalent phosphorylation site is obscured by the unique flanking sequences of PIP5Kα; another is that PIP5Kα is partitioned into a membrane microdomain that is not accessible to Syk.

The differential responses of the PIP5Ks to oxidant stress are consistent with emerging evidence that they have non-redundant roles in the cell (8, 26, 40–43). For example, although all PIP5K are associated with the PM as peripheral proteins, RNAi and gene knock-out studies suggest that they generate functionally distinct PM PIP2 pools (43). In the cells studied here, PIP5Kβ is inactivated by oxidative stress and this may lead to cytoskeletal disruption. Because PIP5Kβ accounts for a larger portion of the ambient PIP2 pool than the other PIP5Ks in HeLa cells (13), oxidant-induced inhibition of PIP5Kβ decreases overall PIP2 to initiate apoptosis. In contrast, PIP5Kγ, which is activated by ROS, may have an anti-apoptotic role. Thus, the balance between these positive and negative signals may dictate the ultimate fate of cells exposed to oxidative stress. This would explain why Syk, which regulates both PIP5Ks, acts either as a tumor suppressor or promoter depending on the cellular context (37, 38).

Our results also show that there is a complex interplay in the regulation of PIP5Kβ during oxidative stress. PIP5Kβ, which is constitutively Ser/Thr phosphorylated, is activated by Ser/Thr dephosphorylation during hypertonic stress without incurring tyrosine phosphorylation (25). However, during oxidative stress, PIP5Kβ is both Ser/Thr dephosphorylated and tyrosine phosphorylated. Because oxidative and hypertonic stress exert opposite effects on PIP5Kβ behavior, we suggest that Tyr-105 tyrosine phosphorylation is the dominant signal in determining PIP5Kβ localization and activity. The high basal activity of PIP5KβY105F, which cannot be tyrosine phosphorylated on Tyr-105, is consistent with this possibility. In contrast, WT PIP5Kβ, which may be dynamically tyrosine phosphorylated/dephosphorylated, is likely to have lower overall catalytic activity. We postulate that the activity of PIP5KβY105F may increase further during oxidative stress because it is activated by Ser/Thr dephosphorylation. The dramatic disruption of the actin cytoskeleton and the accumulation of abnormal vesicles in cells expressing PIP5KβY105F highlight the importance of dynamic regulation of the PIP5Kβ activity to maintain normal cellular functions.

The opposite effects of oxidant and hypertonic stress on PIP5Kβ may explain why hypertonic resuscitation, which is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of several types of traumatic injuries (The ROC Consortium, NHLBI, National Institutes of Health), may be effective in protecting against complications of burn injury (15, 44). Burn trauma induces massive oxidative stress (2, 4) that compromises the endothelial barrier in the lung microvasculature (4). The oxidant-induced disruption of the actin cytoskeleton and decrease in PIP2 described here could contribute to the breaching of the endothelial barrier. Hypertonicity-induced increases in PIP2 levels and actin stabilization may protect against ROS-induced damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. W. Hilgemann for the use of the HPLC apparatus, C. Shen for help with HPLC analyses, and Arianna Nieto and David Pardon-Perez for technical expertise.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 5P50-GM21681 and Robert A. Welch Foundation I-1200 grant.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PM

- plasma membrane

- PIP5Kβ

- phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase

- Syk

- spleen tyrosine kinase

- DN

- dominant negative

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- LSP

- low speed pellet

- HSP

- high speed pellet

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PIPES

- 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- WT

- wild type

- Cyt

- cytosolic fraction

- PI4P

- phosphoinositol 4-phosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Genestra M. (2007) Cell Signal. 19,1807–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parihar A., Parihar M. S., Milner S., Bhat S. (2008) Burns 34,6–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnage R. H., Nwariaku F., Murphy J., Schulman C., Wright K., Yin H. (2002) World J. Surg. 26,848–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton J. W. (2003) Toxicology 189,75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giorgio M., Trinei M., Migliaccio E., Pelicci P. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8,722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fridlyand L. E., Philipson L. H. (2006) Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2,241–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slemmer J. E., Shacka J. J., Sweeney M. I., Weber J. T. (2008) Curr. Med. Chem. 15,404–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao Y. S., Yin H. L. (2007) Pflugers Arch. 455,5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge M. J. (1993) Nature 361,315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rameh L. E., Cantley L. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274,8347–8350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesaeli N., Tappia P. S., Suzuki S., Dhalla N. S., Panagia V. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 382,48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halstead J. R., van Rheenen J., Snel M. H., Meeuws S., Mohammed S., D'Santos C. S., Heck A. J., Jalink K., Divecha N. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16,1850–1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y. J., Li W. H., Wang J., Xu K., Dong P., Luo X., Yin H. L. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167,1005–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burg M. B., Ferraris J. D., Dmitrieva N. I. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87,1441–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton J. W., Maass D. L., White D. J. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290,H1642–H1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto M., Chen M. Z., Wang Y. J., Sun H. Q., Wei Y., Martinez M., Yin H. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281,32630–32638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurosaki T., Takata M., Yamanashi Y., Inazu T., Taniguchi T., Yamamoto T., Yamamura H. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179,1725–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagi S., Inatome R., Takano T., Yamamura H. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288,495–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renedo M. A., Fernández N., Crespo M. S. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31,1361–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauvrak S. U., Wälchli S., Iversen T. G., Slagsvold H. H., Torgersen M. L., Spilsberg B., Sandvig K. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17,1096–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozelle A. L., Machesky L. M., Yamamoto M., Driessens M. H., Insall R. H., Roth M. G., Luby-Phelps K., Marriott G., Hall A., Yin H. L. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10,311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonnerot C., Briken V., Brachet V., Lankar D., Cassard S., Jabri B., Amigorena S. (1998) EMBO J. 17,4606–4616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasuhoglu C., Feng S., Mao J., Yamamoto M., Yin H. L., Earnest S., Barylko B., Albanesi J. P., Hilgemann D. W. (2002) Anal. Biochem. 301,243–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasuhoglu C., Feng S., Mao Y., Shammat I., Yamamato M., Earnest S., Lemmon M., Hilgemann D. W. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283,C223–C234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto M., Hilgemann D. H., Feng S., Bito H., Ishihara H., Shibasaki Y., Yin H. L. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152,867–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao Y. S., Yamaga M., Zhu X., Wei Y., Sun H. Q., Wang J., Yun M., Wang Y., Di Paolo G., Bennett M., Mellman I., Abrams C. S., De Camilli P., Lu C. Y., Yin H. L. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 184,281–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watts R. G., Crispens M. A., Howard T. H. (1991) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 19,159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei Y. J., Sun H. Q., Yamamoto M., Wlodarski P., Kunii K., Martinez M., Barylko B., Albanesi J. P., Yin H. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277,46586–46593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin H. L., Janmey P. A. (2003) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65,761–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denu J. M., Dixon J. E. (1998) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2,633–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S. J., Itoh T., Takenawa T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276,4781–4787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S. Y., Voronov S., Letinic K., Nairn A. C., Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168,789–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padrón D., Wang Y. J., Yamamoto M., Yin H., Roth M. G. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162,693–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin S., Inazu T., Takata M., Kurosaki T., Homma Y., Yamamura H. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 236,443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto N., Hasegawa H., Seki H., Ziegelbauer K., Yasuda T. (2003) Anal. Biochem. 315,256–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown F. D., Rozelle A. L., Yin H. L., Balla T., Donaldson J. G. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154,1007–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tohyama Y., Yamamura H. (2006) IUBMB Life 58,304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakraborty G., Rangaswami H., Jain S., Kundu G. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281,11322–11331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L., Devarajan E., He J., Reddy S. P., Dai J. L. (2005) Cancer Res. 65,10289–10297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasaki J., Sasaki T., Yamazaki M., Matsuoka K., Taya C., Shitara H., Takasuga S., Nishio M., Mizuno K., Wada T., Miyazaki H., Watanabe H., Iizuka R., Kubo S., Murata S., Chiba T., Maehama T., Hamada K., Kishimoto H., Frohman M. A., Tanaka K., Penninger J. M., Yonekawa H., Suzuki A., Kanaho Y. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201,859–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Paolo G., Moskowitz H. S., Gipson K., Wenk M. R., Voronov S., Obayashi M., Flavell R., Fitzsimonds R. M., Ryan T. A., De Camilli P. (2004) Nature 431,415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y., Lian R., Chen X., Bach T. L., Lian L., Petrich B. G., Monkley S. J., Critchley D. R., Sasaki T., Birnbaum M. J., Weisel J. W., Hartwig J., Abrams C. S. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118,812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y., Chen X., Lian L., Tang T., Stalker T. J., Sasaki T., Kanaho Y., Brass L. F., Choi J. F., Hartwig J. H., Abrams C. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105,14064–14069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kreimeier U., Messmer K. (2002) Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 46,625–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]