Abstract

The period surrounding release from prison is a critical time for parolees, bearing the potential for a drug-free and crime-free life in the community but also high risks for recidivism and relapse to drugs. The authors describe two projects. The first illustrates the use of a formal Delphi process to elicit and combine the expertise of treatment providers, researchers, corrections personnel, and other stakeholders in a set of statewide guidelines for facilitating re-entry. The second project is a six-session intervention to enable women to protect themselves against acquiring or transmitting HIV in their intimate relationships.

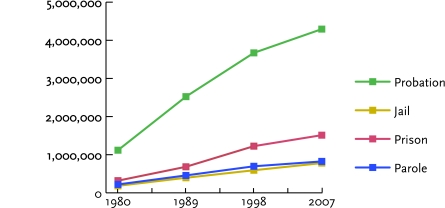

Of the nearly 1.8 million admissions to substance abuse treatment in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2006, 38 percent resulted from criminal justice referrals (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). In some jurisdictions, criminal justice referrals account for even higher percentages of substance abuse treatment entries—for example, two-thirds of those in Kentucky (Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, 2006). Although most offenders who enroll in treatment do so in lieu of incarceration, a significant percentage are re-entering their communities after having served terms in jail or prison (for data on the increasing size of adult correctional populations, see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The Growth in Adult Correctional Populations, 1980–2007

Figure adapted from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance/corr2.htm).

The period following release from incarceration is often very difficult. Offenders must balance their new freedom with the requirements of parole and other expectations. They often desire to make up for time lost while incarcerated and need to adjust to personal relationships that may have changed. Research to date has established a few firm principles for assisting substance-involved offenders during this period. We know that:

prison-based treatment can enhance offenders’ chances of making a successful transition (Leukefeld, Farabee, and Tims, 2002);

offenders who attend community aftercare following prison-based treatment have less drug use and fare better economically than those who do not (O’Connell et al., 2007); and

in the broad population of offenders, coerced community treatment results in outcomes that are as good as those obtained with uncoerced treatment, and these results very likely apply as well to offenders in re-entry.

Beyond these general principles, substance abuse researchers and clinicians are working to identify treatment approaches that can respond to the special needs of substance-abusing parolees (Prendergast, 2009). To succeed, these efforts and any resulting interventions must mesh successfully with the criminal justice system, which has ultimate supervisory authority over offenders during re-entry (Heaps et al., 2009).

This article describes two projects aimed at improving treatment for re-entering offenders, both conducted at the University of Kentucky Central States Research Center (KCSRC) for the NIDA Criminal Justice–Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS) network. The first project brought together justice and treatment providers and other stakeholders to jointly generate guidelines for facilitating successful re-entry. The resulting Kentucky Re-Entry Guidelines for Drug-Abusing Offenders (Staton Tindall et al., 2007a) will serve as a framework for re-entry activities in Kentucky. The process through which these diverse collaborators were able to efficiently integrate their expertise in a substantive consensus document may be useful to other States and communities. In the second project, KCSRC is conducting trials of an intervention it developed to reduce HIV acquisition and transmission among women making the transition from incarceration to life in their communities. Preliminary data suggest that the intervention successfully alters assumptions and reduces risky behaviors.

A PROCESS FOR AGREEMENT

One challenge in coordinating criminal justice and substance abuse efforts is simply the number of concerns and perspectives to be considered. To ensure representation of relevant knowledge areas and stakeholder interests in the new guidelines, KCSRC solicited input from more than 40 individuals, including wardens and deputy wardens from correctional facilities, prison- and jail-based substance abuse treatment providers, probation and parole officers and supervisors, transition case managers and supervisors, and community treatment administrators and counselors. To facilitate the task of eliciting, evaluating, and merging all these perspectives, KCSRC implemented a formal Delphi process.

Delphi processes are designed to generate consensus analyses of complex issues in which multiple viewpoints and types of expertise count (Linstone and Turoff, 1975). For example, educators might use a Delphi process to reach agreement on what subject matter students should master to merit certification in a particular academic or professional field. A basic Delphi process involves three stages: Administrators (1) circulate questions that solicit each participant’s thoughts and priorities regarding the issue, (2) construct a document from the feedback and circulate it for comment and revision, and (3) repeat the second step until a version of the document emerges that the great majority of participants endorse. The process may be conducted entirely by mail or through a combination of mail and face-to-face group meetings.

Because the number of participants and the range of relevant expertise needed to adequately analyze reentry issues could be unwieldy for a traditional Delphi process, KCSRC utilized a modified “rotational” process. In this approach, participants were divided into sub-panels for quicker turnover of ideas (Custer, Scarcella, and Stewart, 1999). The process extended over nine quarterly meetings. Participants said the face-to-face discussions were critical for appreciating how complex reentry is for the offender and the need for systems integration to enhance his or her chances of success.

The Kentucky Re-Entry Guidelines for Drug-Abusing Offenders (see page 26) exemplifies what States and/or communities can do to develop their own guidelines. Self-generated, customized guidelines fit local organizational structures and philosophies; they are therefore easier to implement than the generic suggestions developed, for example, by the Department of Justice Reentry Partner Initiative, the Urban Institute, the National Institute of Corrections, and the Reentry Policy Council. Nevertheless, as barriers to re-entry exist everywhere, even customized guidelines must be coupled with commitments to organizational and systems change.

THE KENTUCKY RE-ENTRY GUIDELINES FOR DRUG-ABUSING OFFENDERS

Increasing communication and collaboration across agencies—prison treatment, community treatment, and parole—is important to establish a continuum of care for offenders at community re-entry.

More consistency within and across prison-based drug abuse treatment and community-based treatment will increase treatment participation and decrease recidivism and relapse.

Re-entry processes should be tailored to meet the needs of the individual and should begin at least 6 months before re-entry so that each offender’s unique contextual factors and barriers can be addressed.

Preparation before release from prison is crucial in the key areas of living arrangements, employment, and family support and should address offenders’ needs for a resumé, driver’s license, Social Security card, job training, and appropriate medications.

Community support systems—including Alcoholics Anonymous/Narcotics Anonymous, family support, and mentorship programs— should be identified and used.

Case management approaches should target living arrangements, employment, and family support at re-entry.

REDUCING POST-RELEASE HIV RISK

Epidemiological and survey data reveal a pressing need to increase HIV services for offenders. HIV infection is more prevalent among offenders than among the general U.S. population (Maruschak, 2007), with about 25 percent of all infected individuals cycling through the criminal justice system (Hammett, Harmon, and Rhodes, 2002). Ideally, correctional institutions and community-based treatment programs should provide comprehensive HIV programming with education, rapid testing, prevention and treatment interventions, and medical care referrals at community re-entry. Actual circumstances are far from this ideal, with only about half of all correctional agencies and half of all community-based treatment programs providing even HIV testing (Oser, Staton Tindall, and Leukefeld, 2007).

The prevention of HIV infection in women offenders is a particularly urgent public health priority. Women are the fastest-growing group of U.S. prisoners. Their HIV infection rate is higher than that of male prisoners and about 15 times that of women in the general U.S. population (De Groot and Cu Uvin, 2005). Moreover, women offenders are more likely than their male counterparts to have been sentenced for drug crimes (31.5 versus 20.7 percent) and so have higher risks of HIV exposure associated with drug abuse. Women’s risks of acquiring or transmitting HIV, like other problem behaviors, increase during the adjustment period following release from prison (Reentry Policy Council, 2005).

KCSRC has developed and tested an intervention to enable women to assess their own risks of HIV infection accurately as well as to be assertive and persuasive advocates for safe behaviors with their intimate partners. Many women offenders have participated in relationships that feature risky sexual behaviors and drug abuse (Covington, 1998), as well as emotional, physical, and sexual abuse (Bond and Semaan, 1996).

To identify beliefs and assumptions that limit women’s abilities to refuse or avoid risky behaviors in their intimate relationships, KCSRC investigators conducted six focus groups (Staton Tindall et al., 2007b). Focus group moderators used a script informed by a review of the scientific literature on women’s relationships and by consultation with substance abuse treatment clinicians. The 56 women who participated in the group discussions were all in substance abuse treatment, but they came from various levels of corrections—prison, transitional prison, community re-entry, and drug court supervision. KCSRC investigators analyzed the focus group transcripts and forwarded their findings to a panel of women substance abuse treatment clinicians and researchers for their review. This process led to the identification of seven “Risky Relationship Thinking Myths” (see Thinking Myths) which then became targets of the intervention.

The KCSRC intervention, which is called Reducing Risky Relationships–HIV (RRR–HIV), counters the thinking myths with facts and builds skills for promoting safe behaviors with partners and opting out of unsafe behaviors. In each of five sessions that take place in prison in the weeks before community re-entry, participants examine the presence and impact of one of the thinking myths in their own relationships (see Learning to Make Healthy Choices). Activities include “relationship thought mapping” and structured stories to target specific change. Take away handouts and homework are distributed for review and preparation for the next session. A sixth and final session, conducted with individual participants by telephone 30 days after community re-entry, reviews and reinforces the contents of the earlier sessions. A manual for RRR–HIV delivery is available from the corresponding author, but it is not intended for implementation until efficacy studies are complete.

KCSRC is collaborating with CJ-DATS Research Centers in Connecticut, Delaware, and Rhode Island on a trial of the intervention’s efficacy. Women prisoners were recruited 6 weeks before community re-entry and randomized to receive either RRR–HIV or to view an educational video about HIV. Clinicians who delivered RRR–HIV used the manual and received super-vision after each session. To ensure fidelity and consistency in delivery, a single individual supervised all clinicians for the entire study. In addition, biweekly cross-site conference calls made it possible to update implementation, review data quality, and resolve problems.

Altogether, 422 women were randomized in the trial: 215 to receive RRR–HIV and 207 to view the educational video. Sixty-eight percent of the participants were African-American, and the mean age was 35 years (SD = 9.1 years). Clinicians have conducted 30-day follow up interviews with 168 of the women who received RRR–HIV. These women reported significantly fewer risky behaviors in the month post-release compared with the month immediately prior to incarceration. Their average:

number of sex partners decreased from 4.3 to 0.5 (P = .004);

occasions of unprotected sex decreased from 29.6 to 5.9 (P < .001);

condom self-efficacy (i.e., ability to purchase, carry, and use condoms correctly and confidently and to insist upon condom use with potential partners; Kowalewski, Longshore, and Anglin, 1994) increased significantly (P < .001); and

relationship power, as indicated by the extent of their emancipation from the seven thinking myths, increased significantly (P < .001).

In the 30-day follow up interviews completed thus far, the 168 women who received RRR–HIV were more likely than 162 women from the video-only education intervention to endorse these true propositions:

women who use drugs do not make healthy choices (P = .001);

HIV can be transmitted by shared injection equipment (P = .001);

using crack/cocaine increases HIV/hepatitis risk (P = .020);

one can’t judge HIV risks based only on a partner’s appearance (P = .009);

greater condom self-efficacy decreases HIV risk (P = .048; Kowalewski, Longshore, and Anglin, 1994); and

male and female condoms should not be used together (P < .001).

Offenders who have key identification and job-seeking documents in hand upon release from incarceration are better prepared for a smooth community re-entry. Prescriptions should also be filled to avoid lapses in medication regimens. Some facilities provide small cash disbursements.

THINKING MYTHS

The responses of 56 women in focus groups revealed ideas and assumptions that can make women more vulnerable to HIV acquisition and transmission in their intimate relationships. Researchers codified them into seven Risky Relationship Thinking Myths:

Fear of Rejection: “Having sex without protection will strengthen my relationship.”

Self-Worth: “I only think good things about myself when I am in a relationship, even if it is risky.”

Drug Use: “I can use drugs and still make healthy decisions about sex.”

Safety: “I know my partner is safe by the way my partner looks, talks, and/or acts.”

Trust: “I’ve been with this partner for a long time, so there’s no need to practice safe sex.”

Invincibility: “I will not get HIV, because I’m not really at risk.”

Strategy/Power: “I have to use sex to get what I want.”

These findings are encouraging but should be interpreted with caution. Although every woman eligible for release was invited to join the study, the participants were not a random sample of incarcerated women. In addition, the study data are self-reported and thus are subject to potential bias. Participants may have under-reported sexual risk behaviors, although there is reason to believe that they may have been reasonably forthcoming. Studies have shown that in the case of drug abuse, also a sensitive activity (as well as an illegal one), urinalysis results generally confirm individuals’ self-reports to clinicians and researchers (Del Boca and Noll, 2000; Rutherford et al., 2000). Finally, self-reports may have been biased by faulty recall of risky sexual and other behaviors that occurred before prison.

LEARNING TO MAKE HEALTHY CHOICES

The Reducing Risky Relationships–HIV intervention begins prior to discharge from prison. Once a week for 5 weeks, the women meet for 90-minute group sessions in which they learn new thinking patterns and concrete ways to avoid contracting or transmitting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Thirty days after release from prison, each woman participates in a 30-minute follow up session by phone or in person.

Session One: The Facts about HIV. This session, the most didactic, teaches women general facts and transmission information about HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV). The interventionist also discusses behaviors that increase risk for contracting HIV, HBV, and HCV. Participants learn the risks associated with indirect sharing; how these risks can be reduced by sterilizing intravenous drug use paraphernalia; how the use of crack and cocaine increases risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV; how using male and female condoms can reduce HIV, HBV, and HCV transmission risk; and why the HIV test and risk reduction counseling are important.

Session Two: HIV Addictive Risky Relationships. This session focuses on the drug use thinking myth. The interventionist leads discussions of similarities in the experiences of falling in love, using substances, and being involved in risky relationships; the characteristics of healthy and unhealthy relationships, including sexual relationships; and connections between women’s drug use and risky behaviors. The interventionist presents the physiological effects of drugs and helps participants develop a plan for avoiding drug use.

Session Three: HIV Partner Risky Relationships. This session addresses the fear of rejection and self-worth thinking myths. Discussion material includes the different types of abuse, the cycle of violence and the fact that lulls between abusive episodes do not mean abuse has ended, and how abuse increases women’s risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Women are asked to think of ways they can protect themselves and cope with the painful feelings of abuse without using substances.

Session Four: HIV Risky Sexual Relationships. This session counters the safety, trust, and invincibility thinking myths. Topics covered include the right of women to protect themselves sexually, relationship triggers that can lead to engaging in risky and unprotected sex, and the connection between substance use and risky sex. The interventionist teaches effective communication skills for negotiating safer sex and assists the group in creating a plan to avoid responding to triggers with risky sex.

Session Five: Positive Relationships. This session focuses on the strategy/power thinking myth. The discussion underscores the importance of having multiple supportive relationships, making the point that depending on one person for support can place women in a vulnerable position. The interventionist helps the participants identify areas of support that women need when leaving prison and times when women should call upon others for support. Participants create a list of people they can count on for support and a list of ways they can contribute to relationships. The group also discusses places to find new relationships.

Session Six: Community Follow up. In this post-release session, the interventionist helps participants apply the previous lessons to their lives outside prison. This session also provides support and encouragement for participants as they transition to the community.

Those study limitations notwithstanding, our results suggest that RRR–HIV may be an effective HIV prevention intervention and, more broadly, that HIV prevention for women can be successfully initiated within prison and after community re-entry. We are currently completing 30-day and 90-day follow up data collection, examining changes from baseline to follow up, and assessing additional outcomes that may differ between the intervention group and the educational video comparison group on relationship thinking myths and HIV risk behaviors.

RE-ENTRY OPPORTUNITY

Re-entry is a period of opportunity for offenders to learn to lead crime-free and drug-free lives in their communities. Elevated risks for recidivism, substance abuse relapse, and HIV infection also make re-entry a time of opportunity for interventions to have crucial, lasting impacts. For example, women who use the lessons of RRR-HIV to protect themselves during re-entry may never again be subject to such a confluence of diverse situational risk factors for acquiring the virus.

Many key questions remain to be answered, however, if we are to take full advantage of the potential for facilitated re-entry to reduce relapse, recidivism, and their associated harms. For example, what motivates some drug-involved offenders to pursue drug abuse treatment and other services during re-entry while others do not? Another important question regards the potential of pharmacotherapy for opioid addiction to reduce relapse, recidivism, and infectious disease transmission during re-entry (Cropsey, Villalobos, and St. Clair, 2005). Criminal justice authorities generally have been wary of methadone and buprenorphine therapy, but naltrexone, as a non-opioid, may be more acceptable (Marlowe, 2006; O’Brien and Cornish, 2006). Re-entry protocols could be tested in which pharmacotherapy is begun in prison and subsequently administered by community treatment organizations or public health departments.

Clinicians and researchers need to work together to better understand how environments and expectations affect risky behaviors, such as substance abuse, during re-entry. In our experience, drug abuse and criminal justice practitioners are well aware of the importance of community re-entry, but collaboration is complicated by practical matters such as confidentiality laws, regulations, and practice traditions. Formal mechanisms such as the Delphi process can facilitate working through some of these complications by providing stakeholders with a shared awareness of the many dimensions of re-entry. Guidelines like those developed in Kentucky can serve as community-tailored roadmaps for re-entry.

Hemera Technologies/©Jupiter Images

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support was provided under a cooperative agreement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA). The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaborative contributions by Federal staff from NIDA, members of the NIH/NIDA CJ-DATS Coordinating Center (University of Maryland at College Park, Bureau of Governmental Research, and Virginia Commonwealth University), and the nine Research Center grantees of the NIH/NIDA CJ-DATS Cooperative (Brown University, Lifespan Hospital; Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Center for Therapeutic Community Research; National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Center for the Integration of Research and Practice; Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research; University of Delaware, Center for Drug and Alcohol Studies; University of Kentucky, Center on Drug and Alcohol Research; University of California, Los Angeles, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; and University of Miami, Center for Treatment Research on Adolescent Drug Abuse). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH/NIDA or other participants in CJ-DATS.

REFERENCES

- Bond L, Semaan S. At risk for HIV infection: Incarcerated women in a county jail in Philadelphia. Women & Health. 1996;24(4):27–45. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Drug and Alcohol Research. Adult KTOS FY 2006 Analysis. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Covington SS. Women in prison: Approaches in the treatment of our most invisible population. Women & Therapy. 1998;21(1):141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Villalobos GC, St Clair CL. Pharmacotherapy treatment in substance-dependent correctional populations: A review. Substance Use &Misuse. 2005;40(13–14):1983–1999. doi: 10.1080/10826080500294866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custer RL, Scarcella JA, Stewart BR. The modified Delphi technique: A rotational modification. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education. 1999;15(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AS, Cu Uvin S. HIV infection among women in prison: Considerations for care. Infectious Diseases in Corrections Report. 2005. May–Jun. www.idcronline.org/archives/mayjune05/article.html.

- Del Boca FK, Noll JA. Truth or consequences: The validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 3):S347–S360. doi: 10.1080/09652140020004278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Harmon P, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates and releasees from U.S. correctional facilities, 1997. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(11):1789–1794. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaps MM, et al. Recovery-oriented care for drug-abusing offenders. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2009;5(1):31–36. doi: 10.1151/ascp095131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski MR, Longshore D, Anglin MD. The AIDS risk reduction model: Examining intentions to use condoms among injection drug users. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24(22):2002–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld C, Farabee D, Tims FM. Clinical and policy opportunities. In: Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, Farabee D, editors. Treatment of Drug Offenders: Policies and Issues. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB. Depot naltrexone in lieu of incarceration: A behavioral analysis of coerced treatment for addicted offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(2):131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2005. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2007. NCJ Publication No 218915. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien C, Cornish JW. Naltrexone for probationers and parolees. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell DJ, et al. Working toward recovery: The interplay of past treatment and economic status in long-term outcomes for drug-involved offenders. Substance Use &Misuse. 2007;42(7):1089–1107. doi: 10.1080/10826080701409453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oser CB, Staton Tindall M, Leukefeld CG. HIV testing in correctional agencies and community treatment programs: The impact of internal organizational structure. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(3):301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML. Interventions to promote successful re-entry among drug-abusing parolees. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2009;5(1):4–13. doi: 10.1151/ascp09514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reentry Policy Council. Report of the Reentry Policy Council: Charting the Safe and Successful Return of Prisoners to the Community. New York: Council of State Governments; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MJ, et al. Contrasts between admitters and deniers of drug use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18(4):343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton Tindall M, et al. Establishing partnerships between correctional agencies and university researchers to enhance substance abuse treatment initiatives. Correction Today. 2007a Dec;:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Staton Tindall M, et al. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. The Prison Journal. 2007b;87(1):143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) Highlights—2006 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies; 2008. DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4313. [Google Scholar]