Abstract

The influence of chronic administration of eplerenone on the intracrine as well as on the extracellular action of angiotensin II (Ang II) on L-type inward calcium current was investigated in the failing heart of cardiomyopathic hamsters (TO-2).For this, eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) was administered orally to 2 month-old cardiomyopathic hamsters for a period of 3 months. Measurements of the peak inward calcium current (ICa) was performed in single cells under voltage clamp using the whole cell configuration.

The results indicated that eplerenone suppressed the intracrine action of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density. Moreover, the intracellular dialysis of the peptide did not change the time course of ICa inactivation in animals treated chronically with eplerenone. The extracellular administration of Ang II (10−8 M) incremented the peak ICa density by only 20±8% (n=30) compared with 38±4% (n=35) (P<0.05) obtained in age-matched cardiomyopathic hamsters not exposed to eplerenone. Interestingly, the inhibitory of eplerenone (10− 7 M) on the intracrine action of Ang II was also found, in vitro, but required an incubation period of, at least, 24 h. The inhibitory action of eplerenone on the intracellular action of Ang II was partially reversed by exposing the eplerenone-treated cells to aldosterone (10 nM) for a period of 24 h what supports the view that: a) the mineralocorticoid receptor(MR) was involved in the modulation of the intracrine action of the peptide; b) the effect of eplerenone on the intracrine as well as on the extracellular action of Ang II was related ,in part, to a decreased expression of membrane-bound and intracellular AT1 receptors.

In conclusion: a) eplerenone inhibits the intracrine action of Ang II on inward calcium current and reduces drastically the effect of extracellular Ang II on ICa; b) aldosterone is able to revert the effect of eplerenone; c) the mineralocorticoid receptor is an essential component of the intracrine renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

Keywords: Eplerenone, Intracrine, Angiotensin II, Inward calcium currents, Aldosterone, Failing heart

1. Introduction

It is known that aldosterone binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor which is a transcription factor belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor family. Evidence is available that there is a mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) in the heart [1,2] and that (MR) mediates aldosterone dependent gene expression which is blocked by spironolactone [3]. On the other hand, angiotensin II (Ang II) activates the MR-mediated gene transcription is smooth muscle cells from the coronary artery—an effect blocked by losartan and spironolactone [3]. Indeed, aldosterone enhances the expression of Ang II AT1 receptors in ventricular muscle by 2-fold [4] while eplerenone reduces it significantly [5].

Myocardial infarction increases the production of aldosterone [6] and activates the cardiac renin angiotensin system in the heart [7] with consequent increment of cardiac level of angiotensin II [6]. Both aldosterone and the local renin angiotensin system seem involved in the increased collagen deposition during myocardial infarction (see [8]). Moreover, during heart failure aldosterone production is also increased [9].

Previous studies from our laboratory indicated that intracellular Ang II modulates the gap junction conductance and the inward calcium current in the failing heart of cardiomyopathic hamsters [10,11]. The intracrine action of Ang II is related to the activation of an intracellular receptor similar to AT1 receptor because intracellular losartan blocked the effect of the peptide [10]. Since there is a correlation between the aldosterone levels and the expression of AT1 receptors in the heart it is important to investigate if the intracrine as well as the extracellular action of Ang II on peak ICa density is impaired or abolished by eplerenone.

In the present work this problem was investigated in myocytes isolated from the ventricle of cardiomyopathic hamsters (TO2).

2. Methods

Cardiomyopathic hamsters (TO-2) (Biobreeders; Fitchburg, Massachusetts) were used. The animals were kept in air-conditioned facilities and constant veterinary care was provided. The animals were located at the Animal House and the recommendations of NIH were followed. The animals were anaesthetised with 45 mg/kg of ketamine plus 5 mg/kg of xylazine, (ip) and the heart was removed under deep anaesthesia. The hamsters were divided into two groups: group 1 consisted of 2-month-old cardiomyopathic hamsters (n=25) which present no signs of heart failure and cardiac remodelling. These abnormalities appear beyond 3 months of age [11]. This group will be used to study the influence of normal diet on the peak ICa density. The normal diet will be administered for 3 months; group 2 consisted of 2-month-old cardiomyopathic hamsters (n=25) treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) administered into the chow (Research Diets, NJ) for a period of 3 months. This group was used to measure the influence of eplerenone on the effect of extracellular and intracellular Ang II on peak ICa density and the results were compared with those obtained from group 1.

2.1. Cell isolation

The heart was removed and immediately perfused with normal Krebs solution containing (mM): NaCl 136.5; KCl 5.4; CaCl2-1.8; MgCl2 0.53; NaH2PO4 0.3; NaHCO3 11.9; glucose 5.5; and HEPES 5 with pH adjusted to 7.3. After 20 min, a calcium free solution containing 0.4% collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp) was recirculated through the heart for 1 h. The collagenase solution was washed out with 100 ml of recovery solution containing (mM): taurine 10; oxalic acid 10; glutamic acid 70; KCl 25; KH2PO4 10; glucose 11; EGTA 0.5 with pH adjusted to 7.4. All solutions were oxygenated with 100% O2 [12,13].

Ventricles and auricles were minced (1 to 2 mm thick slices) and the resulting solution was agitated gently with a Pasteur pipette. The suspension was filtered through a nylon gauze and the filtrate centrifuged 4 min at 22 g. The cell pellets were then resuspended in normal Krebs solution. All the experiments were conducted at room temperature.

Suction pipettes were pulled from microhematocrit tubing (Clark Electromedical Instruments) by means of a controlled puller (Narashige). The pipettes which were prepared immediately before the experiment, were filled with the following solution (mM): cesium aspartate 120; NaCl 10; MgCl2 3; EGTA 10; tetraethylammonium chloride 20; Na2ATP 5; HEPES 5 and pH adjusted to 7.3.The resistance of the pipettes varied from 1.5 to 2 MΩ.

2.2. Experimental procedures

All experiments were performed in a small chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Diaphot, Nikon). Ventricular cells were placed in a modified cultured dish (volume 0.75 ml) in an open-perfusion microincubator (Model PDMI-2, Medical Systems). Cells were allowed to adhere to the bottom of the chamber for 15 min and were superfused with normal Krebs solution (3 ml/min) that permits a complete change of the bath in less than 500 ms. A video system (Diaphot) made possible to inspect the cells and the pipettes throughout the experiments.

The electrical measurements were carried out using the patch-clamp technique in a whole cell configuration with an Axon (model 200B) patch-clamp amplifier. The leak currents were digitally subtracted by the P/N method (n=5–6). Experiments performed without leak subtraction indicated low and stable leak currents. Series resistance originated from the tips of the micropipettes was compensated for electronically at the beginning of the experiment. Current—voltage curves were obtained by applying voltage step in 10 mV increments (−40 to +60 mV) starting from a holding potential of −40 mV. All current recording were obtained after 0Ca had been stabilized, which was usually achieved about 8 min after the rupture of cell membrane.

2.3. Quantification of membrane-bound and intracellular AT-1 receptor expression

2.3.1. Membrane-bound receptor staining

Isolated untreated and eplerenone-treated cardiomyocytes were incubated with Anti-Angiotensin Type I receptor primary antibody (1:1000) solution (Abcam, Inc, MA) for 1 h in a humid atmosphere at room temperature. The cells were then washed two times with PBS (1X)/FBS(3%) and then incubated with FITC-secondary antibody (1:200) solution (Abcam, MA) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then washed two times with PBS(1X)/FBS(3%) and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde. Samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.3.2. Intracellular AT1 receptor staining

Untreated and eplerenone-treated cells were permeabilized using the BD Cytofix\Cytoperm Kit (BD biosciences, CA) for 20 min at 4 °C and then incubated with Anti-Angiotensin Type I receptor primary antibody (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution can be used for the simultaneous fixation and permeabilization of cells prior to intracellular staining [14]. The cells were then washed two times with BD Perm/Wash solution (BD biosciences, CA) and then incubated with FITC-secondary antibody (1:200) solution for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were finally washed two times with BD Perm/Wash solution and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.3.3. Flow cytometry

Levels of AT-1 receptor were analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer (BD biosciences, CA) and quantified using specific FITC-calibration standards (Bangs laboratories, IN). The Cell Quest software (BD biosciences, CA) was used for data acquisition and multivariate analysis. FITC emission was measured in the FL1 channel (band pass filter 530/30 nm). Data on scatter parameters and histograms were acquired in log mode. Ten thousand events were evaluated for each sample and standards and the median peak channel obtained from the histograms was used to quantify the membrane-bound and intracellular AT-1 receptor expression. Cardiomyocytes autofluorescence was subtracted from the fluorescence intensity values of the stained samples. The MESF values of each cell sample were determined by entering the corresponding median peak channel number of the cells into the QuickCal® program against the calibration plot generated by the FITC standards.

2.4. Drugs

Angiotensin II and aldosterone were from Sigma Chemical Company and eplerenone was from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. Aldosterone was initially dissolved in 100% ethanol and then a stock solution (0.1 mM ) was prepared in water. The final concentration of ethanol was 0.1% and it had no effect on calcium current. The same procedure was used for eplerenone used in vitro.

2.5. Data analysis

The output of the preamplifier was filtered at 1 kHz and data acquisition and command potentials were controlled with PCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, CA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SE. Comparison between groups were done by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of eplerenone on the extracellular action of Ang II on ICa

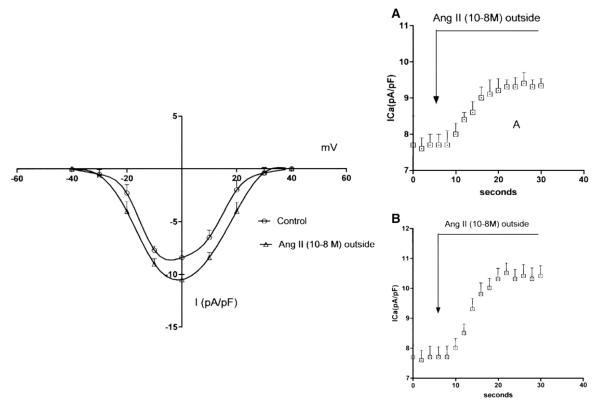

Measurements of the L-type inward calcium current were performed on myocytes isolated from the ventricle of cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for a period of 3 months. The ICa was generated by a test pulse of 400 ms duration from −40 mV to 0 mV. Fig. 1 (top) shows typical examples of voltage and time dependent inward calcium currents recorded from myocytes isolated from eplerenone-treated hamsters before and after the administration of Ang II to the bath. Considering that variations in cell size might influence the value of ICa, the amplitude of ICa was normalized to the membrane capacitance (Cm). Values of Cm in the cardiomyopathic hamsters ranged from 97 to 130 pF. Fig. 1 shows I—V relationships for the whole cell ICa measured before and after the administration of Ang II (10−8 M) to the bath. Both control and Ang II current—density relationships shows a bell shape and voltage dependence. As it can be seen Ang II (10−8 M) incremented the peak ICa density by 20±8%—an effect smaller than that seen in cardiomyopathic hamsters of similar age (38.5±4%) not exposed to eplerenone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Left—voltage dependence of peak ICa density from cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for a period of 3 months before and after the extracellular administration of Ang II (10−8 M).Each point is 30 cells (5 animals) Data are expressed as mean±SEM (P<0.05). Right A—Effect of extracellular Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density on myocytes isolated from cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for 3 months. Each point is the average from 24 cells (4 animals).Vertical line at each point SEM. P<0.05. B—effect of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density recorded from age-matching control animals. Each point is the average from 28 cells (5 animals) P<0.05.

3.2. Effect of eplerenone on the intracellular action of Ang II on ICa

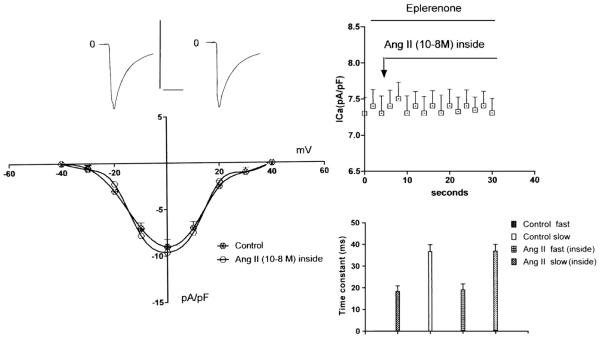

To study the effect of intracellular Ang II on the inward calcium current (ICa) the peptide (10−8 M) was added to the pipette solution and then dialyzed into the cell using an electrode similar to that described by Irisawa and Kokubun [15]. Measurements of peak ICa density were performed before and after intracellular dialysis of the peptide. Fig. 2 shows that Ang II (10−8 M) had no effect on peak ICa density in ventricular myocytes (n=24) (P>0.05) treated with eplerenone. The significance was estimated by comparing the values of ICa before and after the administration of Ang II.

Fig. 2.

Left-Top—L-type Ca2+ current recorded from ventricular cells of cardiomyopathic hamster (5 months-old) treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for a period of 3 months before (left) and after intracellular administration of Ang II ( 10−8 M) (right). The currents were elicited by a test pulse from −40 mV to 0 mV. Vertical calibration 600 pA; horizontal calibration 150 ms. Bottom—voltage dependence of peak ICa density from cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for a period of 3 months before and after the intracellular administration of Ang II (10−8 M).Each point is 30 cells (5 animals) Data are expressed as mean±SEM (P<0.05). Right Top—Inhibitory effect of eplerenone (3 months) on the effect of intracellular action of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density. Each point is the average from 25 cells (5 animals). Vertical line at each point SEM (P>0.05). Bottom—Lack of intracellular Ang II (10−8 M) on the time constant of ICa inactivation (fast and slow components) from animals treated with eplerenone for 3 months. Each bar is the average from 15 cells. Vertical line at each bar SEM(P>0.05).

To investigate further the effect of Ang II, the time course of inactivation of ICa was determined by the decay phase of the current traces elicited by voltage steps in absence and in presence of intracellular Ang II (10−8 M) .The results showed no change on the rate of decay of the current trace at 0 mV in ventricular myocytes of cardiomyopathic hamsters dialyzed with Ang II (see Fig. 2—right). This was true for the whole voltage range. In myocytes from age-matching controls not exposed to eplerenone the inactivation process was enhanced by intracellular Ang II as shown before [11]. Moreover, in animals treated with eplerenone the time to peak of ICa at +10 mV was not significantly altered by intracellular Ang II (6.1±0.3 ms (n=10) in the control and 6.3±0.35 ms (n=10)) (P<0.05) after the administration of intracellular dialysis of Ang II (10−8 M).

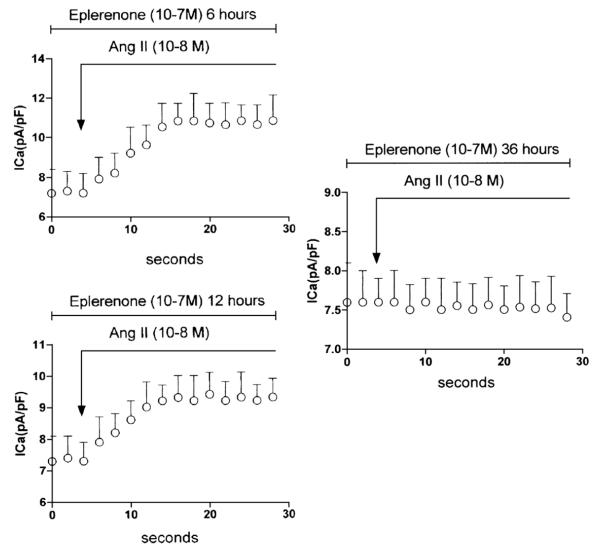

Interestingly, experiments performed on cardiomyocytes isolated from control 5 month-old cardiomyopathic hamsters showed that eplerenone (10−7 M) inhibited the intracrine action of Ang II (10−8 M) in vitro [see Fig. 3] but needs, at least 24 h of incubation to be effective. Fig. 3 shows the results from three different incubation times with eplerenone (10−7 M) (6 h, 12 h and 36 h). As it can be seen in Fig. 3 with 6 h of incubation no inhibition on the intracrine action of Ang II was found but with 36 h incubation with eplerenone the effect of Ang II on ICa was totally abolished.

Fig. 3.

Top—Influence of eplerenone (10−7 M)(6 h) in vitro on the effect of Ang II(10−8 M) on peak ICa density. Each point is the average from 23 cells (4 animals).Vertical line at each point SEM (P<0.05). Bottom—influence of eplerenone (10−7 M) in vitro( 12 h) on the effect of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density. Each point is the average from 26 cells (4 animals). Vertical line at each point SEM (P<0.05). Right—Effect of eplerenone (10−7 M) (36 h) in vitro on the effect of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density. Each point is the average from 25 cells (5 animals).Vertical line at each point SEM (P<0.05).

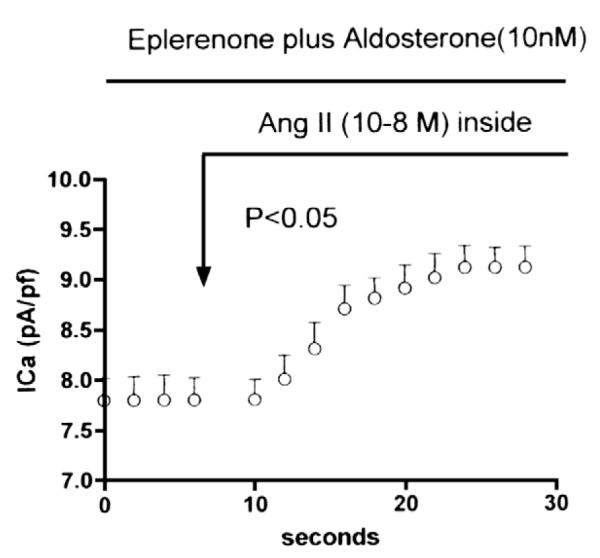

3.3. Can the effect of eplerenone on intracrine action of Ang II be reversed by aldosterone?

To investigate this possibility, cardiomyocytes isolated from the ventricle of cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone for 3 months were incubated with aldosterone (10 nM) for a period of 24 h and then the effect of intracellular administration of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density was investigated. Fig. 4 shows that aldosterone caused a partial reversion of the inhibitory effect of eplerenone on the intracrine action of Ang II on peak ICa density but required an incubation period of, at least, 24 h.

Fig. 4.

Partial reversion of the inhibitory effect of eplerenone (administered for 3 months) on the intracellular action of Ang II (10−8 M) on peak ICa density elicited by incubation with aldosterone (10 nM) for a period of 24 h. Each point is the average from 25 cells (6 animals).Vertical line at each point SEM (P<0.05).

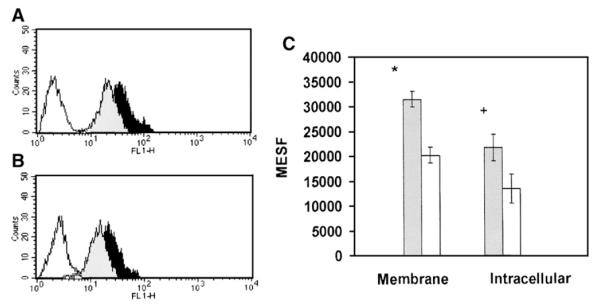

3.4. Eplerenone reduces the expression of AT1 receptors

To investigate the influence of eplerenone on membrane-bound and intracellular AT1 receptors cardiomyocytes exposed to eplerenone (10−8 M) for 24 h were stained for membrane-bound and intracellular detection of AT1 expression using an anti-AT1 monoclonal primary antibody and a FITC-secondary antibody. The expression of AT1 receptors on cardiomyocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry and quantified using specific FITC-calibration standards. As shown in Fig. 5 left eplerenone reduced significantly the expression of AT1 receptors in the membrane as well as in the intracellular medium. Indeed, the quantification by flow cytometry using FITC-calibration standards, revealed a significant decline in MESF units of the expression of the membrane-bound receptors after exposure to eplerenone for 24 h (Fig. 5 right).The fluorescence intensity of untreated control cells averaged 31,435±1620 MESF whereas in the cells exposed to eplerenone (10−8 M) averaged 20,187±1561 MESF (P<0.05) (Fig. 5 right).Similar results were found for intracellular levels of AT1 receptors because for untreated cells the average was 21,652±2656 MESF whereas for cells exposed to eplerenone (10−8 M) was 13,380±2926 MESF (P<0.05)(see Fig. 5 right). In Fig. 5 right autofluorescence (1133±126 MESF) of control cells was subtracted from data.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of membrane-bound and intracellular AT1 receptor expression on cardiomyocytes isolated from cardiomyopathic hamsters and exposed to eplerenone (10−8 M) for 24 h. Left A—shows the effect of eplerenone on AT1 expression on cell membrane. Unlabelled control cells (open figure), the untreated control cells (solid dark figure) and the eplerenone-treated cells( solid gray figure). Left B—shows the influence of eplerenone on intracellular AT1 receptor expression. Unlabelled cells (open figure); untreated control cells (solid dark figure) and eplerenone (10−8 M)-treated cells (solid gray figure). Right C—Histograms showing the quantitative decline of the intracellular and membrane-bound expression of AT1 receptors in cells exposed to eplerenone(10−8 M) for 24 h. Eplerenone-treated cells (open bars) and control cells (gray bars).Quantification in MESF units using the FITC-calibration standards showed a significant decrease of membrane-bound (*P<0.05) and intracellular (+P<0.05).

4. Discussion

The present results indicate that intracellular Ang II was unable to increase the peak ICa density in the failing heart of cardiomyopathic hamsters treated with eplerenone (200 mg/kg/day) for a period of 3 months. This is a relevant finding because it demonstrates that the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) is an essential component and a modulator of the intracrine renin angiotensin system. The mechanism by which eplerenone suppresses the intracellular action of Ang II is probably multifactorial. Indeed, the MR is an intracellular nuclear receptor that belongs to a large family including estrogen, glucocorticoid, progesterone and thyroxine receptors. It is also known that the MR mediates aldosterone-dependent gene expression [5]. Therefore, it is conceivable that in animals treated with eplerenone abnormalities of intracellular signaling pathways including PKC and tyrosine kinase, which are involved in the intracrine action of Ang II [16,17], be implicated in the lack of action of the peptide described above. Previous studies using the same dose of eplerenone , the same experimental conditions described here, the same hamster strain and same dose of eplerenone, indicated that the drug administered for a period of 3 months, reduces interstitial fibrosis, the heart weight/body weight ratio as well as ventricular hypertrophy (see [22]). Moreover, the arterial blood pressure (118±13/85±10 mmHg) was reduced to 90±11/72±12 mmHg (n=10) (P<0.05) after treatment with eplerenone but the heart rate was not significantly altered (430±15/437±13 beats/min) (n=10) (P>0.05).These findings support the view that eplerenone reduces cardiac remodeling, at least in part, through a blockade of the effect of systemic levels of aldosterone (see [23]). However, the question remains whether the decrease of cardiac remodeling elicited by the drug involves a blockade of the effect of Ang II or is the blockade of the extracellular and intracellular action of the peptide that promotes the improvement of heart function. Since aldosterone reversed (in part) the inhibitory effect of eplerenone on the intracrine action of Ang II in vitro, it is conceivable that aldosterone modulates the intracellular action of Ang II on inward calcium current through the MR. The effect of aldosterone required an incubation period of, at least, 24 h raising the possibility that aldosterone activates the intracrine renin angiotensin aldosterone system through a genomic effect. Recent studies indicated that in salt-sensitive hypertensive rats eplerenone reduces cardiac remodeling in part by decreasing the cardiac ACE and angiotensinogen expression [24] suggesting an alteration of the cardiac renin angiotensin system.

Although there is evidence that aldosterone is synthesized in the failing heart [9],this is still a controversial issue because in the normal heart cardiac aldosterone comes from the circulation [25–27], what raises the possibility that the beneficial effects of the drug described above be related, in part, to the blockade of the effect of blood-derivative aldosterone [23]. Moreover, evidence exists that eplerenone has beneficial effects in the failing heart by stimulating endothelial NO synthase with consequent decrease of oxidative stress [28] and that the same protective effect occurs in low-aldosterone animals [29]. Therefore, it is conceivable that at least part of the effect of eplerenone be related to the decline of oxidative stress. Further studies will be necessary to substantiate this view.

Among the different possible mechanisms involved in the action of eplerenone, one is particularly appealing—the decrease in expression of the intracellular AT1-like receptors. Indeed, there is evidence that the intracellular action of Ang II on junctional conductance and ICa are inhibited by intracellular but not by extracellular losartan [10,11]. Moreover, not only nuclear and chromatin Ang II receptors have been identified [18] but immunochemical studies indicate the presence of an intracellular Ang II receptor in cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts [19]. It is known that aldosterone enhances the expression of AT1 receptors while eplerenone reduces it [4,5]. The significant decline on peak ICa caused by extracellular action of Ang II in cells of animals treated chronically with eplerenone, might be due to a reduction in the expression of Ang II AT1 receptors at the surface cell membrane [5].

Experiments performed on isolated myocytes exposed to eplerenone (10−8 M) for a period of 24 h, showed a decline in expression of AT1 receptors both at cell membrane and intracellularly (see above) indicating that the significant decline in the effect of Ang II on ICa seen in cells exposed to eplerenone is in part related to the decrease in expression of AT1 receptors.

The present results lead to the possible conclusion that eplerenone is an inhibitor of the intracrine effect of Ang II. In the cardiomyopathic hamster, at very early stage of heart failure, the intracrine renin angiotensin system is not activated [20] in part due to the low ACE activity [21]. With the development of the disease, however, the intracellular administration of Ang II reduces cell communication [20].

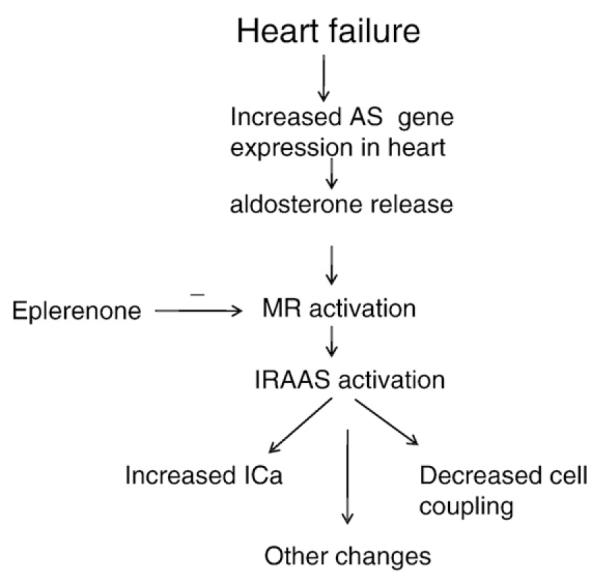

Previous studies showed that eplerenone reduces interstitial fibrosis and enhances the conduction velocity in the failing heart [22]. Although it is known that aldosterone is involved in the generation of fibrosis [30] it is also known that the fibrotic action of aldosterone is related to the activation of the renin angiotensin system [8] (Fig. 6). Therefore, the beneficial effects of eplerenone in the failing heart seems to be, at least in part, related to the inhibition of the intracrine and extracellular actions of Ang II as shown above.

Fig. 6.

Diagram illustrating the possible role of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and aldosterone on the activation of the intracrine renin angiotensin aldosterone system (IRAAS). AS-aldosterone synthase (see Refs. [6,8]).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals.

References

- [1].Pierce P, Funder JW. High affinity aldosterone binding sites (type 1 receptors) in rat heart. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1987;14:859–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1987.tb02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lombes M, Oblin ME, Gase JM, Baulieu EE, Framan N, Bouvalet JP. Immunohisto-chemical and biochemical evidence for a cardiovascular mineralocorticoid receptor. Circ Res. 1992;71:503–10. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jaffe IZ, Mendelsohn ME. Angiotensin II and aldosterone regulate gene transcription via functional mineralocorticoid receptors in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2005;96:643–50. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159937.05502.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Robert V, Heymes C, Silvestre JS, Sabri A, Swynghedauw B, Delcayre C. Angiotensin AT1 receptor subtype as a cardiac target of aldosterone: role in aldosterone-salt induced fibrosis. Hypertension. 1999;33:981–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.4.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fraccarollo D, Galupo P, Schmidt I, Ertl G, Baursachs J. Additive amelioration of left ventricular remodeling and molecular alterations by combined aldosterone and angiotensin receptor blockade after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Silvestre JR, Robert V, Heymes C, Aupetit-Faisant B, Monas C, Moalic JM, Swynghedauw B, Delcayre C. Myocardial production of aldosterone and corticosterone in the rat. Physiological regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4883–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:215–62. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Delcayre C, Heymes C, Milliez P, Swynghedauw B. Throphic effects of aldosterone. In: De Mello WC, editor. In renin angiotensin system and the heart. John Wiley and Sons; West Sussex: 2004. pp. 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mizuno Y, Yoshimura M, Yasue H, et al. Aldosterone production is activated in failing ventricles of humans. Circulation. 2001;103:72–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].De Mello WC. Renin angiotensin system and cell communication in the failing heart. Hypertension. 1996;27:1267–72. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].De Mello WC, Monterrubio J. The influence of intracellular and extracellular angiotensin II on the L-type calcium current in the failing heart. Hypertension. 2004;44:360. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000139914.52686.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Powell T, Twist T. A rapid technique for the isolation and purification of adult cardiac muscle cells having respiratory control and a tolerance to calcium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;72:327–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tanigushi Y, Kokubun S, Noma A, Irisawa H. Spontaneously active cells isolated from the sinoatrial and atrioventricular node of the rabbit heart. Jpn J Physiol. 1981;31:547–58. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.31.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Prussin C, Metcalfe DD. Detection of intracellular cytokine using flow cytometry and directly conjugated anti-cytokine antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1995;188:117–28. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Irisawa H, Kokubun S. Modulation of intracellular ATP and cyclic AMP of the slow inward current in isolated single ventricular cells of the guinea pig. J Physiol. 1983;338:321–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].De Mello WC. Intracellular angiotensin II regulates the inward calcium current in cardiomyocytes. Hypertension. 1998;32:976–82. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].De Mello WC. Heart failure. How important is cellular sequestration?. The role of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Re RN, LaBiche RA, Bryan SE. Nuclear-hormone mediated changes in chromatin solubility. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;110:61–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fu ML, Schulze W, Wallukat G, et al. Immunochemical localization of angiotensin II receptor (AT1) in the heart with anti-peptide antibody showing a positive chronotropic effect. Receptor Channels. 1998;6:99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].De Mello WC. Further studies on the effect of intracellular angiotensins on heart cell communication: on the role of endogenous angiotensin II. Reg Pept. 2003;115:31–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].De Mello WC, Crespo MJ. Correlation between changes in morphology, electrical properties and angiotensin converting enzyme activity in the failing heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;378:187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].De Mello WC. Beneficial effects of eplerenone on cardiac remodeling and electrical properties of the failing heart. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System. 2006;7:40–6. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chai W, Danser AHJ. Why are mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists cardioprotective? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;374:153–62. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0107-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Takeda Y, Zhu A, Yoneda T, Usukura M, et al. Effects of aldosterone and angiotensin II receptor blockade on cardiac angiotensinogen and ACE2 expression in Dahl-salt-sensitive rats. Am J Hypertns. 2007;20:1119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gomez-Sanchez E, Ahmad N, Romero DG, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Origin of aldosterone in the rat heart. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4796–802. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fiebeler A, Nussberger J, Schgdarsuren E, Rong S, Hilfenhaus G, Al-Saadi N, et al. Aldosterone synthase inhibitor ameliorates angiotensin II-induced organ damage. Circulation. 2005;111:3087–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.521625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chai W, Garrelds IM, de Vries R, Danser AH. Cardioprotective effects of eplerenone in the rat heart: interaction with locally synthesized or blood-derivative aldosterone ? Hypertension. 2006;47:665–70. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205831.39339.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kobayashi N, Yoshida K, Nakano S, Ohno T, Honda T, et al. Cardioprotective mechanisms of eplerenone on cardiac performance and remodeling in failing rat hearts. Hypertension. 2006;47:671–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000203148.42892.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nagata K, Obata K, Xu J, Ichihara S, Noda A, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and failure in low-aldosterone hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2006;47:656–64. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000203772.78696.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Delcayre C, Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. The role of aldosterone. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1577–84. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]