Abstract

Drawing on ecological and gender socialization perspectives, this study examined mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with young adolescents, exploring differences between mothers and fathers, for sons versus daughters, and as a function of parents’ division of paid labor. Mexican immigrant families (N = 162) participated in home interviews and seven nightly phone calls. Findings revealed that mothers reported higher levels of acceptance toward adolescents and greater knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities than did fathers, and mothers spent more time with daughters than with sons. Linkages between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment were moderated by adolescent gender and parents’ division of paid labor. Findings revealed, for example, stronger associations between parent–adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment for girls than for boys.

Keywords: Adolescence, Adjustment, Mexican American, Parent–adolescent relationships

Introduction

Gender is an organizing feature of family responsibilities in Mexican culture and may have implications for the potentially different roles of mothers and fathers and the different experiences of girls versus boys. Although characterizations of Mexican American families as rigidly traditional are inaccurate, there is some evidence that mothers assume greater care giving responsibilities than do fathers and some suggestion that parents are more protective of daughters as compared to sons (Azmitia and Brown 2002; Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez 2000; Valenzuela 1999). The lack of descriptive information about gender dynamics and family socialization processes in ethnic minority and immigrant families limits our understanding of both maternal and paternal parenting roles, however. In this study, we investigate the role of gender in Mexican immigrant families living in the USA by examining how parent and adolescent gender and the gendered nature of the family context (i.e., the division of paid labor) are associated with qualities of the parent-adolescent relationship and linkages between parenting and youth adjustment.

Youth born to Mexican immigrants represent the largest proportion of immigrant children living in the USA today. Of all children born to immigrants in the USA, 39% are from Mexico with no other single country representing more than 4% of immigrant children (Hernandez et al. 2007). Mexican Americans comprise the majority of Latinos (i.e., 67%), the largest ethnic minority group in the USA and one that has grown rapidly over the past two decades (Ramirez and Patricia de la Cruz 2002). Despite these demographic trends, 5% to 10% of published articles in family and developmental journals focus on youth and parents of Latino origin (Hagen et al. 2004; McLoyd 1998). Scholars who study minority families further note the need for ethnic-homogeneous designs to promote understanding of experiences within cultural groups (e.g., McLoyd 1998). This study answers the call for descriptive information about ethnic minority family processes in its examination of the nature and correlates of parent-adolescent relationship qualities in Mexican immigrant families.

The present study draws on ecologically-oriented and gender socialization perspectives to address two goals: (a) to describe mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with young adolescents along four dimensions (i.e., warmth/acceptance, conflict, involvement, and knowledge of daily activities), testing differences between mothers and fathers and in the parenting of sons versus daughters and examining the role of parents’ division of paid labor (i.e., father-earner versus dual-earner families); and (b) to investigate the links between mother– and father–adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment, examining the moderating role of parents’ division of paid labor and adolescent gender. Information was gathered from mothers, fathers, and young adolescents during home interviews and a series of seven nightly phone calls. Findings from this study will provide insights about family and developmental processes for scholars working with youth from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Describing Mother– and Father–Adolescent Relationships

Investigating the nature of mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with young adolescents is important given the limited attention to the roles of fathers in Mexican American families (Gamble et al. 2007; Parke and Buriel 1998). Comparisons of the extent to which mothers and fathers participate in children’s and adolescents’ daily lives in European American families reveal a consistent pattern of greater involvement of mothers as compared to fathers (Parke and Buriel 1998). Evidence of women’s greater responsibilities in care giving and childrearing roles in Mexican culture (e.g., Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez 2000) led us to expect that similar patterns may emerge in Mexican immigrant families. Specifically, our first hypothesis was that mothers, on average, would evidence greater involvement in parenting (i.e., more knowledge, higher levels of involvement and warmth) than would fathers.

The gender intensification perspective (Galambos et al. 1990; Hill and Lynch 1983) further directs our attention to the potentially important role of the same-gender parent in family socialization processes in early adolescence. According to this perspective, the increased pressure for young adolescents to conform to gender-typed role expectations may mean that the same-gender parent plays a more salient role than the opposite-gender parent does in socialization during this developmental period. Evidence of gender intensification in family socialization processes has been documented in European American families with young adolescents (Crouter et al. 1995; Updegraff et al. 1996). In families with opposite-gender sibling pairs, for example, adolescents increased the amount of time they spent with same-gender parents over the transition to adolescence (Crouter et al. 1995). More generally, gender socialization perspectives suggest that parents may perceive socializing same-gender youth as their primary role, and same-gender pairs may share more common interests and activities (Huston 1983). Drawing on these ideas, our second hypothesis was that mothers and fathers may have closer (i.e., higher levels of warmth/acceptance) and more involved relationships (i.e., more time spent) with their same-gender (as compared to opposite-gender) offspring in Mexican immigrant families during early adolescence.

Links between Parent–Adolescent Relationship Qualities and Youth Adjustment

Our second goal was to examine the links between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment as indexed by adolescents’ reports of risky behaviors (including adolescents’ own problem behavior and their affiliations with deviant peers), depressive symptoms, and school performance. These adjustment indices were selected to represent internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as youth’s school achievement. We were particularly interested in understanding the extent to which gender played a role in parenting-adjustment linkages by considering adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and their fathers, testing whether different patterns emerged for girls versus boys, and exploring the moderating role of parents’ division of paid labor. Given gender differences in patterns of adolescent adjustment for youth from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004), understanding the role of family gender dynamics is important.

The degree of warmth and closeness in the parent-offspring relationship has been identified as a protective factor for youth experiencing a variety of stressors (Masten et al. 1990). Warmth and support between parents and adolescents is a core feature of most theoretical perspectives on family socialization and is highlighted as a critical aspect of the parent–offspring relationship for positive youth social and emotional development (Steinberg 2001). Studies focused specifically on Latino and Mexican American youth show that warm and supportive parenting is associated with adaptive youth functioning (e.g., Bámaca et al. 2005; Bronstein 1984).

Conflict with parents is a key process in adolescence, and may be particularly salient in immigrant families as parents and young adolescents are simultaneously negotiating changes in their relationships that may result from the developmental transition through adolescence and changes that may result from adapting to another culture and to differential acculturation within the family (i.e., when parents and youth adapt to US culture at different rates). Higher rates of conflict in immigrant as compared to native born families has been noted in some studies, and a number of scholars have attributed this conflict to intergenerational discrepancies in acculturation that is common in immigrant families, although the evidence is inconsistent (see Birman 2006, for a review). More generally, conflict between parents and youth in Mexican American families has been associated with higher levels of conduct problems and more frequent symptoms of anxiety and depression (e.g., Gil-Rivas et al. 2003; Lau et al. 2005; Pasch et al. 2006), suggesting that conflict may be a particularly important predictor of adjustment in Mexican immigrant families.

We also studied mothers’ and fathers’ involvement, or time spent in shared activities, with adolescents. Spending time in activities with parents may reflect strong orientations toward family, a characteristic that has often been attributed to Mexican American culture (Sabogal et al. 1987). Time spent with parents may serve as a protective factor in that it reduces the opportunities youth have to spend time in unsupervised settings with peers, an important predictor of problem behavior (Osgood et al. 1996). Consistent with these ideas, one study showed that Mexican American youth’s self-reports of time spent in activities with parents were associated with lower levels of delinquency (Smith and Krohn 1995). Drawing on theory and research, our third hypothesis was that higher levels of warmth/acceptance and involvement and lower levels of conflict would be linked to more positive adjustment (i.e., higher school achievement, less depressive symptoms, fewer risky behaviors).

Parents’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities was the final dimension of parenting we investigated. Higher levels of parental supervision, monitoring, and knowledge have been associated with lower levels of youth externalizing behaviors and higher levels of school competence and performance in European American families (Crouter et al. 1990; Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber 1984) and with higher levels of academic adjustment and self esteem and lower levels of delinquency in Latino families (Bámaca et al. 2005; Cota-Robles and Gamble 2006; Plunkett and Bámaca-Gómez 2003). There is evidence of different patterns for boys and girls in the associations between monitoring and adjustment (Jacobsen and Crockett 2000) that also depend on the larger family (Crouter et al. 1990) and social context (Bámaca et al. 2005). Crouter et al. (1990) found, for example, that the associations between parental knowledge of youth’s daily activities and conduct problems differed for boys and girls in single- versus dual-earner families, with parental monitoring being particularly important for boys’ adjustment in dual-earner families. In this study, we extend this research to Mexican immigrant families.

The Moderating Role of Parents’ Division of Paid Labor and Adolescent Gender

Our study is grounded in ecological and contextual perspectives (Bronfenbrenner and Crouter 1982), which highlight the role of the social context in shaping proximal processes within the family and, in turn, youth well-being. Parents’ division of paid labor is one element of the family context that has implications for the way roles and responsibilities are defined within families (Perry-Jenkins et al. 2000) and may shape Mexican immigrant parents’ relationships with their sons and daughters. Considerable attention has been directed at how parents’ division of paid labor, particularly whether only fathers or both mothers and fathers work in two-parent families, is related to parent–child interactions and youth development in European American families (Perry-Jenkins et al. 2000). However, almost no empirical work has considered the role of parents’ division of paid labor in parent-child relationships and youth well-being in Mexican American families (Updegraff et al. 2007). The scant research on Mexican American families has linked maternal employment to more egalitarian role structures in the marriage and parents’ egalitarian beliefs about housework and childcare (Ybarra 1982). In this study, we examined whether the nature of the parent-adolescent relationship and the connections between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment varied across families that differed in parents’ division of paid labor, i.e., families where fathers were the primary earners versus families where both fathers and mothers were involved in paid work. Differences in father-earner and dual-earner contexts in mothers’ and fathers’ work experiences and management of work-family responsibilities were also explored in an effort to understanding the parent-adolescent relationship in these different family contexts.

We also examined the role of adolescent gender in exploring the connections between parenting and youth adjustment. Little is known about the role of gender in the parent–offspring relationship or in the links between parent–adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment in Mexican American families. Work by McHale and colleagues (2005), using data from the present sample, suggests the importance of gender dynamics in parent-offspring relationships in families of Mexican origin. Focused on parents’ differential treatment, McHale et al.’s work revealed that in families with strong ties to Mexican culture (primarily immigrant families), parents displayed more differential treatment of sons versus daughters in some domains of parenting (e.g., allocation of chores and privileges) than did parents with stronger ties to Anglo (US) culture. In the present study, we focus in particular on Mexican immigrant families and the role of gender in four broad dimensions of parenting (i.e., warmth, conflict, involvement, and knowledge of daily activities). We anticipated that one of two patterns may emerge. First, one possibility is that parents play a more central role for same-gender offspring. Parent socialization perspectives highlight the idea that mothers and fathers may feel a particular responsibility to socialize their same-gender offspring (Huston 1983), and a “child effects” model and gender intensification perspective suggests that girls and boys may be more receptive to the involvement and socialization efforts of their same-gender parent. A second possibility is that the greater orientation of girls toward dyadic relationships (Maccoby 1998) and the greater emphasis in Mexican American families on daughters’ family responsibilities and the more protective role that is noted for daughters (Azmitia and Brown 2002; Valenzuela 1999), may mean that parent-adolescent relationship qualities are stronger predictors of girls’ than of boys’ adjustment.

Summary

In sum, there were three hypotheses in the proposed study. Related to our first goal of describing mother– and father–adolescent relationships, our first hypothesis was that mothers would report greater involvement in parenting (i.e., warmth, involvement, knowledge) than would fathers, and our second hypothesis was that parents would report higher levels of warmth/acceptance and more time spent with same- than with opposite-gender youth. In regards to our second goal of examining parenting-adjustment linkages, our third hypothesis was that higher levels of parental warmth, lower levels of conflict, and higher levels of involvement would be linked to less involvement in risky behaviors, fewer depressive symptoms, and higher school performance. We further investigated whether connections between parenting and adjustment were moderated by adolescent gender and parents’ division of paid labor. Given the limited focus on Latino and Mexican American families in prior work, we viewed the analyses testing the moderating role of adolescent gender and parents’ division of paid labor as exploratory.

Method

Participants

The data came from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican origin families (Updegraff et al. 2005). The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around a southwestern metropolitan area. Given the goal of the larger study, to examine family socialization processes in Mexican American families with adolescents, criteria for participation were as follows: (1) seventh graders and at least one older adolescent sibling lived at home; (2) biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers lived at home (all non-biological fathers had been in the home for a minimum of 10 years); (3) mothers were of Mexican descent; and (4) fathers worked at least 20 h/week. Importantly, our sampling criteria and our focus on a local population mean that our sample was not designed to be representative of Mexican American families in general. Instead, the overall study goals directed our attention to two-parent families so that we could examine the roles of mothers and fathers.

The names of families with a Latino seventh grader who was not learning disabled were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools (n = 1,856 Latino families). To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in both English and Spanish) were sent, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Eligible families (i.e., those who met the four criteria defined above) included 421 families (23% of the initial rosters and 32% of those we were able to contact and screen for eligibility). Of the 421 eligible families who met study criteria, 284 (67%) agreed to participate and 246 (58%) completed interviews. Those who agreed but did not participate in the final sample (n = 38) were families that we were unable to locate to schedule the home interview, that were unwilling to participate when the interview team arrived at their home, or that were not home for repeated interview attempts. Because we had surpassed our target sample size (N = 240) we did not continue to recruit the latter group of participants.

The present study focuses on parents’ relationships with seventh graders (the target youth) in the immigrant portion of this sample, defined by families where both mothers and fathers were born in Mexico (n = 162; 66% of the larger sample of 246 families). Immigrant families represented a range of education and income levels from poverty to upper class. Annual median family income was $33,750, ranging from $4,600 to over $300,000, and 26.5% of families met federal poverty guidelines. Parents had completed an average of about 9 years of education (M = 9.19; SD = 3.71 for mothers, and M = 8.65; SD = 4.27 for fathers). Parents had lived in the USA an average of 11.3 (SD=7.6) and 14.7 (SD = 8.6) years for mothers and fathers, respectively. Almost all parent interviews (i.e., 97% of fathers and 96% of mothers) were conducted in Spanish. With respect to seventh graders, the sample included 81 girls and 81 boys who were an average of 12.8 (SD = .57) years of age. Most seventh graders were interviewed in English (i.e., 77%) and slightly more than half (i.e., 53%) were born in Mexico.

Procedures

Data were collected using two procedures. First, a team of four interviewers visited each family’s home and conducted separate interviews with the participating family members (mothers, fathers, target adolescents, and older siblings). Interviews with individual family members were conducted simultaneously in separate locations in the home using laptop computers. Interviews averaged three hours with parents and two hours with adolescents. Questions were read aloud due to variability in family members’ reading levels. Information from individual family members was treated as confidential and was not shared with other family members.

During the 3 to 4 weeks following the home interviews, families were telephoned on seven evenings (five weekday evenings and two weekend evenings) and family members reported on their activities during the prior 24-h period (5 p.m.. to 5 P.M.), excluding school time; adolescents participated in all seven calls and parents participated in four calls each. Using a cued-recall strategy (McHale et al. 1992), adolescents reported on their involvement in 86 daily activities, including how long each event lasted and who else participated. From these data, we calculated the time mothers and fathers spent in activities with adolescents.

Informed consent was obtained prior to the interview. Families were paid a $100 honorarium for their participation in the home interview and an additional $100 for participating in the phone interviews.

Measures

All measures were translated to Spanish (for Mexican dialect in the local area) and back translated to English by separate individuals (Foster and Martinez 1995). All final translations were reviewed by a third native Mexican translator and discrepancies were resolved.

Background Information

Parents reported on their education in years, their annual household income, whether or not they were employed and the number of hours worked per week, and their years living in the USA An SES variable was created by standardizing mothers’ and fathers’ education levels and family income and calculating a mean score.

Family Earner Status

Parents’ division of paid labor was indexed by creating two groups of families: father-earner and dual-earner. All fathers were employed a minimum of 20 h/week based on sampling criteria, with fathers working an average of 46.28 h/week (SD = 11.77). Mothers’ work situations were more variable, with 62 mothers not working for pay, and the remaining mothers working an average of 34.56 h/week (SD = 12.82). Because mothers’ work hours were not normally distributed, we categorized families as father-earner families when mothers worked less than 10 h/week (n = 64) and dual-earner families when mothers worked 10 h/week or more (n = 94).

Work-Related Experiences and Parent Well-Being

We examined potential differences between father-only and dual-earner families in fathers’ work-related experiences (i.e., underemployment, work pressure) and parents’ perceptions of role overload to gain a better understanding of the differences in parents’ experiences in these two types of families. Fathers rated their underemployment using seven items created for this study to tap parents’ perceptions about whether their jobs tap their full earning and skill potential (e.g., “Given my skills, education, and experience, I should be in a better job than my current job”) on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for fathers’ ratings was .93.

Fathers also rated their work pressure with the Work Pressure Scale from the Work Environment Scale (WES), Form R (Moos 1986). This nine-item scale (e.g., “There is a constant pressure to keep working”) assesses the degree to which work pressures and time demands characterize the participant’s job on a scale from Very True (1) to Very Untrue (5). Alpha for fathers’ work pressure was .73.

Mothers’ and fathers’ role overload was assessed with an adapted version of The Role Overload Scale (Reilly 1982; House and Rizzo 1972). The 13-item scale measures parents’ sense that there is too much to do and not enough time to do it on a 5-point scale ranging from Strongly disagree to Strongly Agree (e.g., “I need more hours in the day to do all the things which are expected of me”). Cronbach’s alphas were above .90 for both parents.

Parent–Adolescent Relationship Qualities

Mothers and fathers described their relationships with adolescents in terms of warmth/acceptance and frequency of conflict during home interviews. Measures of parental knowledge of adolescents’ every day activities and of time spent in shared activities were collected via the daily phone data.

Mothers and fathers completed the 8-item parent version of the warmth/acceptance subscale of the Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (Schwarz et al. 1985). Each of eight items (e.g., “I am able to make ‘child’s name’ feel better when he/she is upset”) was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from “Almost never” to “Almost always.” Higher scores on this summed scale reflected greater warmth and acceptance. Cronbach’s alphas were above .80 for mothers’ and fathers’ reports.

Mothers and fathers reported on the frequency of conflict with adolescents during the past year (ranging from 1 = Not at all to 6 = Several times a day) regarding 12 topics (e.g., chores, bedtime/curfew, family obligations) using an adapted version of measures by Smetana (1988) and Harris (1992). A sample item is “How often in the past year have you had disagreements or differences of opinion with ‘child’s name’ about respect for parents such as talking back or being disrespectful?” Cronbach’s alphas were .84 for mothers and .87 for fathers.

Parents’ knowledge about adolescents’ everyday whereabouts, companions, and activities was indexed by a 24-item scale (Crouter et al. 1999). Parents and adolescents were asked a series of questions (e.g., “Did ‘child’s name’ talk to any friends on the phone today?”) and follow-up probes (e.g., “Which friends?”) regarding adolescents’ daily activities during the series of nightly phone calls. The questions were asked in different sequences over three phone calls so parents could not prepare for the questions ahead of time. Parents received a score of 2 if their entire answer matched the adolescent’s, a score of 1 if their initial answer matched but the probe did not, and a score of 0 if there was no match. The scores were averaged and converted to percentages to indicate the percent agreement between parents and adolescents; high scores indicated that parents were highly knowledgeable about their adolescents’ daily experiences.

Parents’ time spent with adolescents was assessed by daily activity data collected during the phone interviews. Specifically, during each phone call, adolescents reported on the durations (in minutes) and companions (e.g., mother, father, peers, and siblings) in 86 daily activities. The number of minutes that adolescents reported participating in activities with their mothers was aggregated across the seven phone calls to measure mother-adolescent involvement. A parallel measure of father–adolescent involvement was created. We measure adolescents’ total time with each parent, regardless of who else was present. We used adolescents’ reports because youth participated in all seven phone calls, whereas parents only participated in four phone calls. Correlations between parents’ and adolescents’ reports of parents’ time with adolescents for the four phone calls in which they both participated in the larger sample (n = 239) were r = .80, p<.001, and r = .81, p<.001, for mothers’ and fathers’ time spent with adolescents, respectively.

Youth Adjustment

Youth’s depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). The 20-item measure provides an index of cognitive, affective and behavioral depressive features (e.g., “I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor”); respondents rate the frequency with which these symptoms have occurred (ranging from 1 = Rarely or none of the time to 4 = Most of the time) with high scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptoms (α=.83).

Adolescents’ risky behaviors were assessed by their reports of how frequently they engaged in 21 problem behaviors (Eccles and Barber, unpublished scale). Items were rated on a four-point scale ranging from Never to More than ten times (e.g., smoked cigarettes, got suspended from school). Higher scores indicated more risky behavior. Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

To assess deviant peer affiliations, adolescents reported on their close friends’ involvement in deviant activities using a five-item scale adapted for multi-ethnic samples (Barrera et al. 2001; Mason et al. 1996) from the Denver Youth Survey (Huizinga et al. 1991) and National Youth Survey (Elliot and Ageton 1980). Adolescents rated items such as “How many of your friends have used force (e.g., threats or fighting) to get things from people?” on a 5-point scale (“none” to “almost all”); higher scores represented higher ratings of deviant peer affiliations (α=.75).

Adolescents reported on their current grades in four academic subjects (English, Social Studies, Math, and Science) and their grade point averages (GPAs) were computed. The correlation between school report grades and self-reported grades for adolescents in our larger sample who had both (n = 228) was r=.89, p<.01.

Results

The results focus on our two goals: (1) to describe Mexican immigrant mothers’ and fathers’ relationship qualities with their adolescent sons versus daughters and to explore the role of family earner status (i.e., father-only versus dual-earner); and (2) to examine the links between mother– and father– adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment, testing adolescent gender and family earner status as moderators.

Preliminary Analyses

The goal of these preliminary analyses was to explore the ways in which father-only versus dual-earner families may differ to provide a background for interpreting the moderating role of family earner status. To test for differences between father-earner and dual-earner families in background characteristics (i.e., income, education, years living in the USA), fathers’ work characteristics (i.e., work hours, underemployment, work pressure), and parent well-being (i.e., role overload), we conducted a series of 2 (Family Earner Status: Dual-earner versus Father-earner) × 2 (Adolescent Gender) × 2 (Parent: Mother versus Father) mixed model ANOVAs. Family earner status and adolescent gender were the between subjects factors and parent was the within-subjects effect. For some background variables there were only family-level measures (e.g., family income), and therefore, no within-subjects factor was included. We focus on main effects and interactions involving family earner status.

There were no significant family earner status differences in family income, parents’ education levels, fathers’ work hours, or fathers’ work pressure. A Parent × Family Earner Status interaction was significant for parents’ years living in the USA, F (1,154) = 5.07, p<.05, d = .24, with mothers (but not fathers) in dual-earner families (M = 12.07; SD = 7.77) living in the USA longer than mothers in father-only earner families (M = 10.25; SD = 7.39). In addition, there was a Family Earner Status × Adolescent Gender interaction for fathers’ underemployment, F (1,153) = 8.17, p<.001, d = .55, with differences emerging for dual- versus father-earner families with girls but not boys. Fathers reported higher levels of underemployment in dual-earner families with daughters (M = 3.71, SD = .89) as compared to father-only earner families with daughters (M = 3.15, SD = 1.15). Finally, a Family Earner Status × Parent interaction, F (1,152) = 5.57, p<.001, d = .25, and follow up analyses revealed that in dual-earner families mothers reported higher levels of role overload than did fathers (M = 3.28; SD = .85 for mothers, M = 3.02, SD = .98 for fathers) with the reverse pattern found in father-only earner families (M = 2.93; SD = .97 for mothers, M = 3.13, SD = .95 for fathers).

Goal 1: Describing Mother– and Father–Adolescent Relationship Qualities

To address our first goal of describing mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with adolescents, we conducted a series of 2 Family Earner Status (father-earner versus dual-earner) × 2 (Adolescent Gender) × 2 Parent (mother versus father) mixed model ANOVAs with adolescent gender and family earner status as between subjects factors and parent as a within-subjects factor. Dependent variables were parents’ ratings of warmth/acceptance and conflict with adolescents, parents’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities, and parent-adolescent involvement. We calculated Cohen’s d (Cohen 1988) as a measure of effect size for all analyses; adjusted effect size measures were computed for within-group analyses (Cortina and Nouri 2000). Means and standard deviations are shown in Table 1 for descriptive purposes.

Table 1.

Means and SDs for mother– and father–adolescent relationship qualities as a function of adolescent gender and family earner status.

| Girls | Boys | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father-earner | Dual-Earner | Father-Earner | Dual-Earner | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Acceptancea | ||||||||

| Mothers | 4.50 | .46 | 4.11 | .61 | 4.34 | .53 | 4.40 | .53 |

| Fathers | 4.24 | .66 | 3.94 | .64 | 4.20 | .51 | 4.15 | .62 |

| Conflictb | ||||||||

| Mothers | 1.85 | .55 | 2.57 | .98 | 2.30 | .90 | 2.23 | .66 |

| Fathers | 1.90 | .62 | 2.34 | .94 | 2.20 | .90 | 2.17 | .77 |

| Involvementc | ||||||||

| Mothers | 1201.19 | (448.35) | 1048.87 | (500.79) | 837.83 | (459.41) | 827.55 | (547.64) |

| Fathers | 867.74 | (360.68) | 788.89 | (489.83) | 768.88 | (463.05) | 835.85 | (586.18) |

| Knowledged | ||||||||

| Mothers | 52.69 | 8.50 | 52.02 | 9.35 | 53.44 | 7.80 | 52.36 | 8.03 |

| Fathers | 45.79 | 9.47 | 44.86 | 11.62 | 43.41 | 11.19 | 46.16 | 11.66 |

Acceptance is rated on a 5-point Likert scale

Conflict is rated on a 6-point Likert scale

Involvement is measured in minutes per 7 days, ranging from 30 to 2,680 min

Knowledge is measured as the percentage agreement between parents’ and adolescents’ responses and ranges from 0% to 100%

Preliminary Analyses

We conducted correlations between mother- and father-adolescent relationship qualities. Inter-parent correlations (i.e., between mothers’ and fathers’ reports) were r = .24, p<.01, for acceptance, r = .41, p<.01, for conflict, r = .22, p<.01, for knowledge, andr = .78, p<.01, for involvement. For mothers, acceptance and conflict were negatively related, r = −.49, p<.01, and the same pattern was found for fathers, r = −.26, p<.01. No other intra-parent associations emerged for mothers or for fathers.

Warmth/Acceptance

There was a significant parent effect, F (1,154) = 12.07, p<.001, d = .38, with mothers reporting higher levels of warmth/acceptance (M = 4.32; SD = .56) than fathers (M = 4.11; SD = .62). In addition, there was a Family Earner Status effect, F (1,154) = 5.51, p<.05, that was qualified by an Adolescent Gender × Family Earner Status interaction, F (1,154) = 5.59, p<.05, d = .69. Tukey follow up tests revealed that parents reported greater acceptance of daughters in father-earner (M = 4.37; SD = .43) as compared to dual-earner families (M = 4.03; SD = .55). No differences emerged for boys across these two family types.

Conflict

Two significant effects were found for parents’ ratings of conflict. The family earner status effect was significant, F (1,153) = 5.87, p<.05, d = .43, but qualified by an Adolescent Gender × Family Earner Status interaction, F (1,153) = 8.34, p<.01, d = .87. Follow up tests for the interaction revealed that parents reported more conflict with daughters in dual-earner (M = 2.45; SD = .85) than in father-earner families (M = 1.85; SD = .52) but conflict with boys did not differ as a function of family earner status.

Involvement

On average, mothers spent more time with adolescents than did fathers, F (1,150) = 42.05, p<.001, d = .31, and girls reported spending more time with parents than did boys, F (1,150) = 4.19, p<.05, d = .31. Both these main effects were qualified, however, by an Adolescent Gender × Parent interaction, F (1,150) = 27.90, p<.001, d = .56, such that mothers of daughters spent more time with their adolescents (M = 1109.41; SD = 483.50) than mothers of sons (M = 831.61; SD = 511.45), but differences in fathers’ time did not vary by adolescent gender (M = 820.23; SD = 442.19 for fathers of girls; M = 809.41; SD = 538.66 for fathers of boys).

Knowledge

The only significant effect was a Parent effect, F (1,148) = 54.44, p<.001, d = .75, with mothers reporting more knowledge about adolescents’ daily activities (M = 52.52; SD = 8.38) than fathers (M = 45.19; SD = 11.06).

Summary

Consistent with our first hypothesis, we found that mothers, on average, reported higher levels of warmth/acceptance, involvement, and knowledge than did fathers. We found partial support for our second hypothesis with mothers (but not fathers) spending more time with their same-gender as compared to opposite-gender offspring.

Goal 2: Linkages between Parent–Adolescent Relationship Qualities and Youth Adjustment

To address our second goal, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression models separately for mother– and father–adolescent relationship qualities, with parent–adolescent relationship qualities as the independent variables and youth adjustment (i.e., risky behavior, deviant peer affiliations, depressive symptoms, and GPA) as the dependent variables. The first step included SES as a control variable; in the second step, we added adolescent gender, family earner status, and mother-adolescent relationship qualities (i.e., warmth/acceptance, conflict, involvement, and knowledge). We tested interactions between adolescent gender and mother–adolescent relationship qualities and between family earner status and mother–adolescent relationship qualities in separate steps. The final models included control variables, main effects, and significant interactions because retaining interactions that are not significant contributes to an increase in standard errors (Aiken and West 1991). Parallel models were conducted to test the role of father-adolescent relationship qualities. Adolescent gender (0 = girls; 1 = boys) and family earner status (0 = dual earner; 1 = father only earner) were dummy coded and all variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken and West 1991). Follow up analyses for significant interactions were conducted as outlined by Aiken and West (1991). All interactions that were retained in final models accounted for a significant increase in the variance.

Risky Behavior

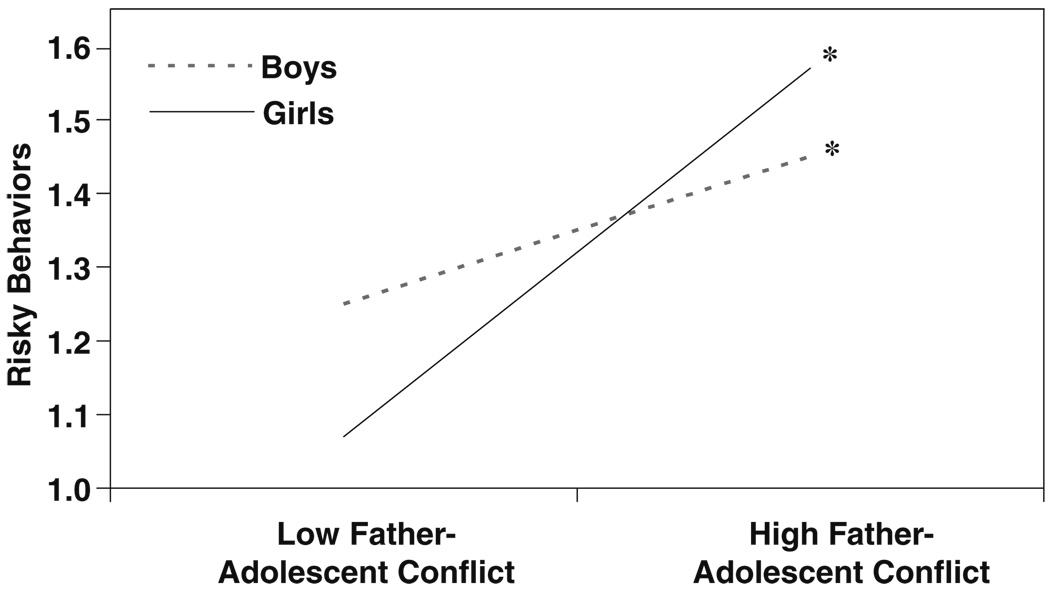

Beginning with the model predicting risky behavior from mother-adolescent relationship qualities, the first step including SES was not significant. In the second step, mother-adolescent conflict was positively associated with adolescents’ risky behavior, F (7,144) = 4.13, p<.001, R2 = .13 (see Table 2). There were no significant interactions with adolescent gender or family earner status. In the model including father-adolescent relationship qualities, the first step was not significant but the second step was, F (7,145) = 2.63, p<.05, R2 = .07. Father-adolescent conflict was positively associated with risky behavior. The final model included one significant interaction between adolescent gender and father-adolescent conflict, F (8,144) = 3.12, p<.01, R2 = .10 (see Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1, the relation between father–adolescent conflict and risky behavior was stronger for girls than for boys.

Table 2.

Summary of hierarchical regression models predicting adolescent risky behaviors.

| Variable | Mothers (N = 158) | Fathers (N = 153) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE B | β | b | SE B | β | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| SES | −.03 | .04 | −.05 | −.03 | .04 | −.05 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| SES | −.05 | .04 | −.10 | −.07 | .04 | −.14* |

| Adolescent gender | .03 | .06 | .03 | .02 | .06 | .03 |

| Family earner status | .02 | .07 | .02 | .04 | .07 | .05 |

| Parental warmth | .04 | .06 | .05 | −.10 | .05 | −.15* |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .21 | .04 | .42*** | .12 | .04 | .26** |

| Parent–adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .04 | .00 | .00 | .02 |

| Parent knowledge | −.00 | .00 | −.08 | −.00 | .00 | −.02 |

| Model 3 | ||||||

| SES | −.07 | .04 | −.12 | |||

| Adolescent gender | .03 | .06 | .03 | |||

| Family earner status | .02 | .07 | .03 | |||

| Parental warmth | −.09 | .05 | −.14* | |||

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .22 | .05 | .44** | |||

| Parent–adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .03 | |||

| Parent Knowledge | −.00 | .00 | −.02 | |||

| Family earner status × parent–adolescent conflict | ||||||

| Adolescent gender × parent–adolescent conflict | −.19 | .08 | −.26** | |||

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Fig. 1.

Interaction between father–adolescent conflict and adolescent gender to predict risky behaviors. An asterisk indicates that the line is significant (p<.05).

Deviant Peer Affiliations

SES was negatively associated with adolescents’ reports of their deviant peer affiliations, F (1,156) = 4.19, p<.05, R2 = .02. In the second step, conflict with mothers was a positive predictor of deviant peer affiliations, F (7,144) = 4.10, p<.001, R2 = .13. The interactions between adolescent gender and mother-adolescent conflict and family earner status and mother-adolescent conflict were each significant and retained in the final model, F (9,142) = 4.45, p<.001, R2 = .17. In the model together, these two interactions were reduced to trends; however, because they were significant when entered separately and because they accounted for a significant increase in the variance explained, we conducted follow up analyses for each interaction. The positive association between mother–adolescent conflict and deviant peer affiliations was significant for girls, β = .42, p<.01, but not for boys, β = .05, ns. In addition, the relation between mother–adolescent conflict and deviant peer affiliations was significant and positive for adolescents from dual-earner families, β = .39, p<.01, but not for adolescents from father-earner families, β = .03, ns.

The second step in the model including father-adolescent relationship qualities revealed SES and father–adolescent conflict as significant predictors, F (7,145) = 3.05, p<.01, R2 = .09. In the final model, a significant interaction between adolescent gender and father-adolescent conflict was retained, F (8,144) = 3.74, p<.01, R2 = .13 (see Table 3). Similar to the pattern in the model including mother– adolescent conflict, father-adolescent conflict was positively associated with deviant peer affiliations for girls, β = .35, p<.01, but not for boys, β = −.09, ns.

Table 3.

Summary of hierarchical regression models predicting adolescent deviant peer affiliations.

| Variable | Mothers (N = 152) | Fathers (N = 153) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE B | β | b | SE B | β | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| SES | −.15 | .07 | −.16** | −.15 | .07 | −.16** |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| SES | −.22 | .07 | −.24*** | −.24 | .07 | −.26** |

| Adolescent gender | −.08 | .11 | −.06 | −.09 | .11 | −.07 |

| Family earner status | .18 | .11 | .12 | .20 | .11 | .14 |

| Parental warmth | .11 | .11 | .09 | −.15 | .09 | −.13 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .30 | .08 | .35*** | .15 | .07 | .18** |

| Parent-adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .07 | .00 | .00 | .01 |

| Parent knowledge | −.00 | .00 | −.00 | −.00 | .00 | −.06 |

| Model 3 | ||||||

| SES | −.24 | .07 | −.26*** | −.23 | .07 | −.24*** |

| Adolescent gender | −.09 | .11 | −.07 | −.09 | .11 | −.06 |

| Family earner status | −20 | .11 | .14* | .16 | .11 | .11 |

| Parental warmth | −.15 | .09 | −.13 | −.14 | .09 | −.12 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .15 | .07 | .18** | .33 | .09 | .39*** |

| Parent–adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .02 |

| Parent knowledge | −.00 | .01 | −.06 | −.00 | .01 | −.06 |

| Adolescent gender × parent–adolescent conflict | −.36 | .13 | −.29*** | |||

| Family earner × parent–adolescent conflict | ||||||

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Depressive Symptoms

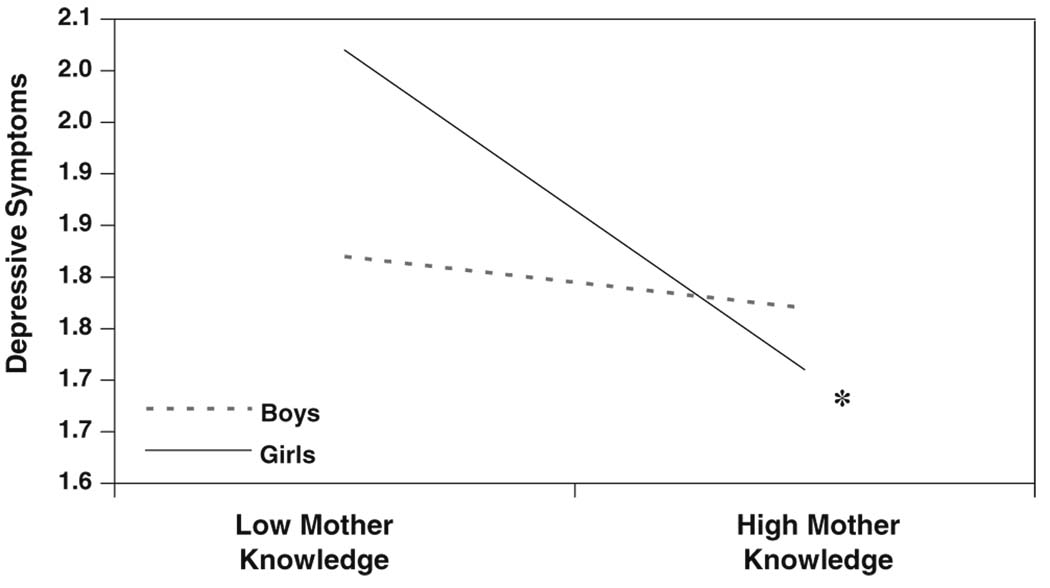

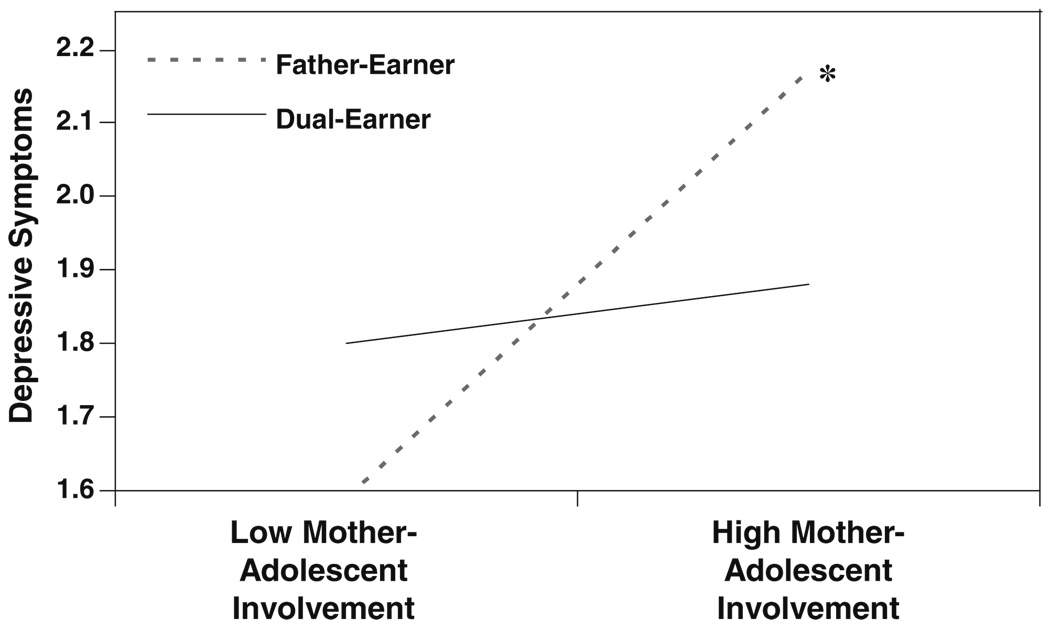

SES accounted for 9% of the variance in depressive symptoms, with higher SES being associated with less depressive symptoms, F (1,156) = 15.91, p<.001. In the second step, mother–adolescent conflict was positively associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms, F (7,144) = 7.02, p<.001, R2 = .22. The final model included SES, mother-adolescent conflict, maternal involvement, mothers’ knowledge, and interactions between (a) adolescent gender and mother–adolescent conflict, (b) adolescent gender and mothers’ knowledge, and (c) family earner status and mother involvement as significant predictors, F (10,141) = 9.72, p<.001, R2 = .37 (see Table 4). The interaction between adolescent gender and mother–adolescent conflict was similar to those described above, with stronger relations for girls, β = .52, p<.01, than for boys, β = .19, p<.01. Mothers’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily experiences was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms for girls but not for boys (see Fig. 2). In addition, mother-adolescent involvement was positively associated with depressive symptoms in father-earner but not dual-earner families (see Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Summary of hierarchical regression models predicting adolescent depressive symptoms.

| Variable | Mothers (N = 158) | Fathers (N = 153) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE B | β | b | SE B | β | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| SES | −.19 | .05 | −.30*** | −.19 | .05 | −.30** |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| SES | −.21 | .05 | −.33*** | −.23 | .05 | −.37*** |

| Adolescent gender | −.10 | .07 | −.11 | −.14 | .07 | −.15** |

| Family earner status | .04 | .07 | .04 | .06 | .07 | .06 |

| Parental warmth | −.03 | .07 | −.03 | −.10 | .06 | −.13 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .20 | .05 | .35*** | .13 | .04 | .23*** |

| Parent–adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .12 | .00 | .00 | .03 |

| Parent knowledge | −.00 | .00 | −.09 | .00 | .00 | .03 |

| Step model 3 | ||||||

| SES | −.21 | .04 | −.33*** | −.23 | .05 | −.36*** |

| Adolescent gender | −.07 | .07 | −.07 | −.13 | .07 | −.13* |

| Family earner status | .00 | .07 | −.00 | .04 | .07 | .04 |

| Parental warmth | −.02 | .06 | −.02 | −.10 | .06 | −.12 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | .36 | .05 | .62*** | .24 | .06 | .41*** |

| Parent–adolescent involvement | .00 | .00 | .46*** | .00 | .00 | .33** |

| Parent knowledge | −.01 | .00 | −.20** | .00 | .00 | .03 |

| Adolescent gender × parent–adolescent conflict | −.33 | .08 | −.36*** | −.22 | .08 | −.27*** |

| Adolescent gender × parent knowledge | .02 | .01 | .18** | |||

| Family earner status × parent–adolescent involvement | −.00 | .00 | −.38*** | −.00 | .00 | −.35** |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Fig. 2.

Interaction between mother knowledge and adolescent gender to predict depressive symptoms. An asterisk indicates that the line is significant (p<.05).

Fig. 3.

Interaction between mother–adolescent involvement and family earner status to predict depressive symptoms. An asterisk indicates that the line is significant (p<.05).

For father-adolescent qualities, the first step including SES was significant as described above. In the second step, adolescent gender, and father-adolescent conflict were significant predictors, with girls reporting more depressive symptoms than boys and father-adolescent conflict positively associated with depressive symptoms, F (7,145) = 5.50, p<.001, R2 = .17. The final model included a significant interaction between adolescent gender and father-adolescent conflict and between family earner status and father involvement (see Table 4), accounting for 24% of the variance, F (9,143) = 6.34, p<.001. Again, the interaction between adolescent gender and father–adolescent conflict revealed a significant association for girls, β = .37, p<.01, but not for boys, β = −.04, ns. Similar to the findings for maternal involvement, father involvement was positively associated with depressive symptoms in father-earner, β = .32, p<.05, but not dual earner families, β = −.09, ns.

GPA

SES was not a significant predictor of GPA in the first step of the models, but parent–adolescent relationship qualities were significant in the second step. Mother– adolescent conflict and involvement were negatively related to GPA, and mothers’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities was positively related to GPA, accounting for 21% of the variance, F (7,134) = 6.29, p<.001. In the father model, father-adolescent conflict was the only significant predictor, accounting for 7% of the variance, F (7,135) = 2.48, p<.05. Adolescent gender and family earner status did not moderate any of the associations between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescents’ GPAs (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of hierarchical regression models predicting adolescent GPA.

| Variable | Mothers (N = 142) | Fathers (N = 143) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | B | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| SES | .11 | .10 | .09 | .11 | .10 | .09 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| SES | .17 | .09 | .14* | .19 | .10 | .16* |

| Adolescent gender | −.32 | .15 | −.17** | −.21 | .15 | −.11 |

| Family earner status | −.16 | .15 | −.08 | .23 | .16 | −.12 |

| Parental warmth | −.04 | .14 | −.02 | .12 | .12 | .08 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | −.46 | .09 | −.42*** | −.26 | .09 | −.24*** |

| Parent–adolescent involvement | −.00 | .00 | −.18** | −.00 | .00 | −.06 |

| Parent knowledge | .02 | .01 | .19** | .00 | .01 | .05 |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

Summary

We found partial support for our third hypothesis with conflict being linked to all indices of adjustment,with stronger patterns for girls than for boys. Inconsistent with our expectations, parental warmth was not linked to adjustment. There was a complex pattern of associations between parental involvement and adjustment, revealing some evidence that involvement was related to more positive adjustment (e.g., school performance) but also that involvement was related to higher levels of depressive symptoms (only in father earner families).

Discussion

This study drew on contextual and ecological frameworks and gender socialization perspectives to explore the nature of mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with their young adolescents and to examine the connections between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment in Mexican immigrant families living in the USA. In doing so, we attended to the potentially different roles of mothers and fathers with sons versus daughters and to the gendered nature of the family context as defined by parents’ division of paid labor. Our multi-method, multi-informant approach alleviates potential concerns about shared method variance and reporter biases, thereby increasing our confidence in the findings. Further, our findings contribute to emerging literature aimed at describing developmental and family processes for youth from ethnic minority backgrounds (McLoyd 1998).

Describing Mothers’ and Fathers’ Relationships with Young Adolescents

Our findings revealed some consistent differences between the roles of mothers and fathers in these two-parent families that are congruent with the idea that mothers assume care giving roles to a greater extent than do fathers in European American and Mexican American families (Cauce and Domenech-Rodriguez 2000; Parke and Buriel 1998). In support of our first hypothesis, mothers, on average, described themselves as more warm and accepting of their young adolescents than did fathers, mothers had more accurate knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities than did fathers, and mothers spent more time in shared activities with adolescents than did fathers. It is important to note that, despite these mother–father differences, fathers were relatively involved, supportive, and knowledgeable about adolescents’ daily activities. All parents described themselves as supportive (i.e., an average of 4 or higher on a 5-point scale of warmth/acceptance), parents’ average agreement with adolescents’ responses (i.e., parental knowledge) regarding their daily activities ranged from 42% to 50%, and parents spent substantial amounts of time in shared activities with young adolescents (i.e., 12 to 20 h over 7 days). Thus, mothers’ greater involvement relative to fathers’ should be interpreted in the context of both parents displaying high levels of engagement in this sample.

The findings that mothers, but not fathers, displayed different patterns of involvement (i.e., time spent in shared activities) with daughters as compared to sons partially supported our second hypothesis. Mothers of daughters reported spending an average of five more hours per seven days with adolescents than did mothers of sons. The greater involvement of mothers with daughters may have emerged for a number of reasons, all of which will be important to explore in future research. One possibility is that this dyadic involvement with daughters represents mothers’ efforts to serve in a protective role, encouraging their daughters to spend more time with family (Azmitia and Brown 2002; Valenzuela 1999), and thus, potentially less time with peers or involved in community activities. A second possibility, consistent with ideas of gender intensification in early adolescence (Hill and Lynch 1983), is that mothers place a primary emphasis on socializing their same-gender offspring and this greater involvement is part of mothers’ socialization efforts. Finally, a “child effects” explanation (Bell and Harper 1977) would suggest that daughters might place a strong emphasis on family as part of their future roles as caregivers and seek out more time with mothers than sons do.

Although the gender intensification perspective and work with European American families lead us to expect fathers would be more involved with sons than with daughters, our findings revealed similar levels of involvement of fathers with sons versus daughters. It is important to note that these are between-family comparisons (i.e., fathers with sons versus fathers with daughters) and an important next step is to conduct within-family comparisons (i.e., mothers’ and fathers’ involvement with sons and daughters in the same families). If similar patterns emerge within Mexican American families with mothers favoring involvement with daughters and fathers displaying equal levels of involvement with sons and daughters, this may suggest that mothers are more likely than fathers to display gender differentiated involvement with their offspring. Such a pattern would highlight the potentially important role of the cultural context in family gender dynamics (McHale et al. 2005). Future research is needed to provide insights on the distinct roles of mothers and fathers in gender socialization processes in Mexican American families.

The larger family context, in this study defined by parents’ division of paid labor, can shape the nature of parent–offspring relationships (Bronfenbrenner and Crouter 1982; Perry-Jenkins et al. 2000). We found mean level differences in girls’ (but not boys’) experiences as a function of parents’ division of paid labor, with parents describing higher levels of conflict and lower levels of warmth/acceptance with daughters in dual-earner as compared to father-only earner families. Our analyses also revealed that mothers felt more stressed and overwhelmed, and fathers with daughters reported high levels of underemployment in dual-earner families as compared to father-earner families. The greater stresses surrounding work-family roles in dual-earner families, in turn, may be linked to parent–adolescent relationship dynamics with daughters but not sons for several reasons. First, the potentially greater responsibilities and involvement (e.g., household tasks, care giving of younger siblings) that may be expected of daughters in dual-earner families may underlie the higher levels of conflict and less positive feelings in parent-daughter dyads. Second, there may be a greater likelihood of spillover from work–family stress to parent–daughter dynamics to the extent that girls have stronger connections to the family and assume more responsibilities in dual-earner families than do sons. It will be important to replicate these findings and to explore the processes that may underlie the connections between work-family stress and parent–daughter relationship qualities in dual-earner family contexts.

Linkages Between Parent–Adolescent Relationship Qualities and Youth Adjustment

We drew on gender socialization and contextual perspectives to address our second goal of examining the associations between parent–adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment and the potentially different patterns for girls versus boys and for adolescents in father-earner versus dual-earner families. At the most general level, we expected that lower levels of conflict and higher levels of warmth/acceptance and involvement would be related to positive adjustment (our third hypothesis). The most consistent pattern of findings involved parent–adolescent conflict, with more frequent conflicts between parents and adolescents (as described by parents) being related to all four indicators of youth well-being and the only dimension of the parent–adolescent relationship associated with youth’s risky behaviors (i.e., both their own misconduct and their deviant peer affiliations). Although there was evidence that adolescent gender and family context moderated some of the findings, mother-adolescent conflict frequency was linked to greater involvement in risky behaviors and lower grade point averages for all youth. These findings highlight the significance of parent–adolescent conflict for the well-being of immigrant youth in this sample and suggest the importance of further exploring conflict dynamics in immigrant families. Given this study is limited by the cross-sectional design, it will be important in future work to use longitudinal data to learn about the direction of effects. It may be that frequent conflicts with parents lead to adolescents’ greater involvement in problem behaviors or that adolescents’ problem behavior leads to increases in conflicts between parents and young adolescents.

It is notable that the connections between conflict and well-being differed for girls versus boys, with stronger associations for girls than for boys or associations emerging only for girls. Adolescents’ involvement in problem behaviors (e.g., skipping school, smoking) and with deviant peers may elicit greater conflict in parent-daughter, particularly father–daughter, dyads than between parents and sons. This pattern may reflect parenting roles that are more protective of daughters and parents’ concerns about the potentially unique risks for young adolescent girls (e.g., unwanted sexual involvement or pregnancy). The other possibility is that for girls, who value interpersonal relationships (Maccoby 1998) and family roles, conflict with parents may be more salient and have stronger implications for their engagement in problem behavior or feelings of depression than it does for boys. That is, girls may be more sensitive to and affected by conflict with parents and act out to a greater degree or report more depressive symptoms than do boys in response to parent– adolescent conflict. The greater emphasis in Mexican American families on the protection of daughters and on daughters’ responsibilities to the family (Azmitia and Brown 2002; Valenzuela 1999) may underlie stronger associations between parent–daughter than parent–son relationship qualities and youth adjustment.

In contrast to our expectation that higher levels of parental warmth/acceptance would be related to more positive adjustment (e.g., Bámaca et al. 2005; Bronstein 1984), we found no significant associations between parental acceptance and youth adjustment in this sample. The relatively high ratings on our parental warmth/acceptance scale (i.e., greater than 4.0 on a 5.0 scale) may have resulted in ceiling effects and reduced variability, limiting our ability to detect significant associations. It will be important to explore further these associations in Mexican immigrant families using different indices of parent-adolescent support given research highlighting the importance of closeness in parent–youth relationships in European American and Mexican American families (e.g., Bámaca et al. 2005; Bronstein 1984; Masten et al. 1990).

The pattern of findings regarding parents’ involvement and youth well-being suggests the importance of viewing parental involvement from a “child effects” perspective (Bell and Harper 1977). Although we anticipated that parental involvement would reflect strong orientations toward family (Sabogal et al. 1987) and serve as a protective factor (Osgood et al. 1996), our findings suggest that parent involvement also may emerge in response to youth’s needs. When mothers spent more time with youth they reported lower GPAs, and in dual-earner families, parents were spending more time with youth who reported more depressive symptoms. One possibility is that parents are more involved with youth who are facing difficulties (e.g., struggling academically in school) than those who report more positive adjustment. Additional research should focus on identifying the conditions under which parent involvement is linked to more versus less positive adjustment in early adolescence.

Mothers’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities was linked to higher levels of school performance, and for girls, fewer depressive symptoms. When youth are doing well in school and when girls report fewer depressive symptoms, they may be more open to sharing information about their daily activities, resulting in more knowledgeable mothers. In contrast, mothers’ lack of interest in their daughters’ daily activities may also lead to higher levels of depressive symptoms and less motivation to do well in school. More generally, that the links between knowledge and depressive symptoms were found for girls but not boys may reflect mothers’ greater socialization efforts with their daughters or daughters’ receptiveness to their mothers’ efforts to learn about their daily activities. These findings stand in contrast to work with European American families that highlights the role of parental knowledge for boys, particularly in dual-earner families (Crouter et al. 1999), and suggest the importance of understanding the role of parental knowledge in different cultural contexts.

Moderating Role of Parents’ Division of Paid Labor

Understanding the ways in which parenting processes are associated with adolescent adjustment in different family contexts is consistent with the basic tenets of ecological-oriented perspectives. We found evidence that some of the associations between parent–adolescent relationship qualities and youth adjustment differed in dual-earner versus father-only earner families. The positive association between mother-adolescent conflict and adolescents’ risky behaviors was significant in dual-earner but not father-earner families. Mothers in dual-earner families also reported experiencing more role overload (i.e., feeling overwhelmed by managing daily responsibilities) than did mothers in father-only earner families, and differences between mothers and fathers revealed that mothers were more overloaded than were fathers in dual-earner families, but the reverse pattern was found in father-only earner families. One possibility is that mother-adolescent conflict in families where mothers are the more overwhelmed and stressed parent may have significant implications for youth adjustment. It may be that when mothers are overwhelmed and stressed they are less effective in managing and resolving conflicts with young adolescents. Gathering information about the intensity and resolution of conflicts may provide further insights.

Unique to father-earner families was the positive association between mothers’ and fathers’ involvement with adolescents and adolescents’ reports of depressive symptoms. Because time spent with each parent could include the other parent and because mother-adolescent and father– adolescent involvement was highly correlated, this may explain why patterns of parental involvement–depression links were similar for maternal and paternal involvement. This pattern may mean that parents are spending more time with youth who report more depressive symptoms in father-only earner families or that time spent with parents is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. In our sample, father-earner families were characterized by fathers who reported higher levels of role overload than mothers (i.e., they described themselves as experiencing more stress surrounding work-family roles and being overwhelmed), and fathers also tended to experience more pressure at work in father-earner families than dual-earner families. Thus, spending time with parents in a family context that has greater work-related pressures and stress for fathers (and potentially spills over to mothers) may have implications for the emotional climate of parents’ and adolescents’ shared activities. That is, spending time with parents who are experiencing high levels of pressure and stress may result in less positive interactions during shared time, and in turn, a positive association between parent-youth involvement and youth depressive symptoms. Gathering data on the emotional context of parents’ and adolescents’ shared time (e.g., learning about the affective tone of daily activities) will provide more information about the underlying processes. It is also will be important to learn about youth’s perceptions of parents’ work situations and daily work-family stressors to understand how these experiences may be linked to youth well-being.

Limitations and Conclusion

Our findings must be interpreted with their limitations in mind. First, our results are derived from a specific sample of Mexican immigrant families (two-parent families in the Southwest with adolescent offspring). A direction for future work is to study Mexican immigrant families from different geographic locations and from a wider range of family structures. In addition, the cross-sectional design limits our understanding of the directions of effects. It will be important in future work to explore the reciprocal nature of parenting-adjustment linkages over time. Finally, our results are specific to one developmental period and understanding the connections between parenting and adjustment in immigrant families in other developmental periods is important.

In conclusion, this study responds to the call of scholars interested in minority youth and families for investigations of normative socialization processes in ethnic minority families (García Coll et al. 1996; McLoyd 1998). Our findings highlight the important role of both mothers and fathers in young adolescents’ lives, with parenting processes being particularly salient for girls’ well-being in these Mexican immigrant families. We can further enhance our understanding of parenting by exploring how relationships with mothers, in combination with those with fathers, are linked to youth adjustment. Moving beyond individual Sex Roles dyads in the family to understand their interactive influences as well as triadic relationship processes will be an important next step. Finally, understanding how differences across families (e.g., in the division of housework or childcare, parents’ gender role attitudes) shape processes within families adds to our understanding of the complexities of the gendered nature of family life.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Jennifer Kennedy, Devon Hageman, Lilly Shanahan, Shawna Thayer, Emily Cansler, and Sarah Killoren for their assistance in conducting this investigation. Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 (Kimberly Updegraff, Principal Investigator, and Susan M. McHale and Ann C. Crouter, co-principal investigators, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, and Roger Millsap, co-investigators) and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at ASU.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A. Updegraff, Email: kimberly.updegraff@asu.edu.

Melissa Y. Delgado, Email: Melissa.y.delgado@gmail.com.

Lorey A. Wheeler, Email: Lorey@asu.edu.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia A, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Shin N, Alfaro E. Latino adolescents’ perception of parenting behavior and self-esteem: Examining the role of neighborhood risk. Family Relations. 2005;54:621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, et al. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ, Harper LV. Child effects on adult socialization. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D. Measurement of the “acculturation gap” in immigrant families and implications for parent–child relationships. In: Bornstein M, Cotes L, editors. Acculturation and parent–child relationships: Measurement and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Crouter AC. Work and family through time and space. In: Kamerman S, Hayes C, editors. Families that work: Children in a changing world. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1982. pp. 39–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein P. Differences in mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors toward children: A cross-cultural comparison. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:995–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2000. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance summaries. MMWR. 2004 May 21;53(No SS2) [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina JM, Nouri H. Effect size for ANOVA designs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Robles S, Gamble W. Parent–adolescent processes and reduced risk for delinquency. Youth & Society. 2006;37:375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, MacDermid SM, McHale SM, Perry-Jenkins M. Parental monitoring and perceptions of children’s school performance and conduct in dual- and single-earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Manke BA, McHale SM. The family context of gender intensification. Child Development. 1995;66:317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Helms-Erikson H, Updegraff KA, McHale SM. Conditions underlying parents’ knowledge about children’s daily lives in middle childhood: Between-and within-family comparisons. Child Development. 1999;70:246–259. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Ageton SS. Reconciling race and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review. 1980;45:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Martinez CR. Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Almeida DM, Petersen AC. Masculinity, femininity, and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development. 1990;61:1905–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble WC, Ramakumar S, Diaz A. Maternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: An examination of Mexican-American parents of young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:72–88. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Rivas V, Greenberger E, Chen C, Montery y López-Lena M. Understanding depressed mood in the context of a family-oriented culture. Adolescence. 2003;38:93–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen JW, Nelson M, Velissaris N. Comparison of research in two major journals on adolescence; Poster session presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Baltimore, MD. 2004. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Harris VS. But dad said I could: within-family differences in parental control in early adolescence. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1992;52:4104. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández DJ, Denton NA, Macartney SE. Family circumstances of children in immigrant families: Looking to the future of America. In: Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bornstein MH, editors. Immigrant families in contemporary society.Duke series in child development and public policy. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations in early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- House RJ, Rizzo JR. Role conflict and ambiguity as critical variables in a model of organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1972;7:467–505. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Esbensen F, Weiher AW. Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1991;82:83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huston AC, editor. Sex-typing. 4th ed. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen KC, Crockett LJ. Parental monitoring and adolescent adjustment: an ecological perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis Sex Roles among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Cauce AM, Gonzales NA, Hiraga Y. Neither too sweet nor too sour: Problem peers, maternal control, and problem behavior in African-American adolescents. Child Development. 1996;67:2115–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Bartko WT. Traditional and egalitarian patterns of parental involvement: Antecedents, consequences, and temporal rhythms. In: Featherman D, Lerner R, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-span development and behavior. vol. II. New York: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Shanahan LK, Crouter AC, Killoren SE. Siblings’ differential treatment in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67:1259–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Changing demographics in the American population: Implications for research on minority children and adolescents. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Work environment scale manual. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood D, Wilson JK, O’Malley PM, Bachean JG, Johnston LD. Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel RB. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 463–552. [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Penilla C, Pantoja P. Acculturation, parent–adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican American families. Family Process. 2006;45:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC. Work and family in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:981–998. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett SW, Bamaca-Gomez MY. The relationship between parenting, acculturation, and adolescent academics in Mexican-origin immigrant families in Los Angeles. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez RR, Patricia de la Cruz GP. Current Population Reports. Series P-28, Special Censuses. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2002. The Hispanic population in the United States: March 2002; pp. 20–545. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly MD. Working wives and convenience consumption. The Journal of Consumer Research. 1982;8:407–418. [Google Scholar]