Oxygen, used to treat hypoxaemia, may be lethal and should therefore be considered a drug and be prescribed.1 It is, however, recognised that oxygen is poorly prescribed by doctors.2 To ensure the safe and effective delivery of oxygen the prescription should include the flow rate, the concentration, the delivery device, the duration, and the method for monitoring treatment.2 We audited the prescription of oxygen to inpatients by doctors before and after the introduction of a specific prescription chart.

Participants, methods, and results

Junior doctors at the North West Lung Centre are given two lectures on practical aspects of oxygen delivery and prescribing at the beginning of their one year's rotation in respiratory medicine. In 1997 and 1998 the doctors were informed that an audit of their prescribing practice would take place some time during the next year. The outcome measures of the audit were whether the oxygen was prescribed and whether the prescription was accurate—that is, that the audit matched patient use in relation to the delivery device and that the flow rate and concentration were appropriate to that device.

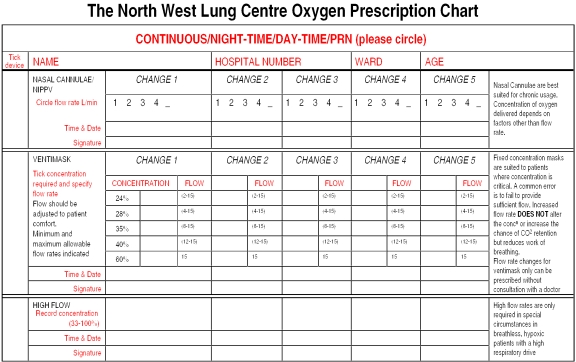

The audit was conducted on three respiratory wards over three months. FK and AD identified all patients receiving oxygen within 24 hours of admission, and they recorded the device, oxygen concentration, and flow rate appropriate to the device for each patient. They consulted a drug Kardex for a prescription of the proposed oxygen treatment. If a prescription was present they recorded the device, concentration, and flow rate. After the first audit, a specific prescription chart for oxygen was developed to encompass all the oxygen delivery systems used on the wards (figure). The methodology for the second audit was identical to that of the first, with the exception that both the chart and the drug Kardex were examined for the prescription. The χ2 test was used to analyse the prescription of oxygen before and after the introduction of the chart.

Overall, 115 patients were identified as receiving oxygen in the first audit and 121 in the second. In the first audit oxygen was prescribed for 63 of the 115 (55%) patients. After the chart was introduced the number of oxygen treatments prescribed increased to 110 of 121 (91%) patients (P<0.001). The prescription was accurate for eight (7%) patients in the first audit and 93 (77%) in the second. The accuracy of prescription was 94% (73 of 78 patients) with the chart and 63% (20 of 32) with the drug Kardex.

Comment

Our first audit showed that oxygen was infrequently well prescribed, as previously described.2,3 Junior doctors poorly understand the effects and dangers of oxygen, and lectures alone were insufficient to ensure safe and effective practice.4 The prescription chart for oxygen listed the delivery devices, guided the doctor to prescribe the appropriate concentration and flow rate, and provided additional notes for the specific indications of each device.

The most common omission from the prescriptions was flow rate. The flow rate of fixed concentration masks should be adjusted for patients with high peak inspiratory flows. Flow rate is the only variable that is prescribed with nasal cannulas, and an accurate prescription of flow rate is essential as hypercapnic respiratory failure may occur.4 Oxygen for delivery by nasal cannula is often prescribed by concentration, with the assumption that an inspired oxygen concentration of 24% equates to 2 l/min; concentrations of 24%-35% with 2 l/min have been described.5

The prescription of oxygen is complex, and a drug Kardex does not accommodate the precise details required for the variety of delivery devices. This was clearly shown in the second audit, where the accuracy of the prescription was greater with the chart than with the drug Kardex. We have shown that a specific prescription chart for oxygen improved clinical practice in our specialist medical respiratory centre, and we recommend the use of such a chart.

Figure.

Prescription chart for oxygen introduced after first audit

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.British National Formulary. 1999;37:153. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateman NT, Leach RM. ABC of oxygen. Acute oxygen therapy. BMJ. 1998;317:798–801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7161.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small D, Duha A, Wieskopf B, Dajczman E, Laporta D, Kreisman H, et al. Uses and misuses of oxygen in hospitalised patients. Am J Med. 1992;92:591–595. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies RJO, Hopkin JM. Nasal oxygen in exacerbations of ventilatory failure: an underappreciated risk. BMJ. 1989;299:43–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6690.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazuaye EA, Stone TN, Corris PA, Gibson GJ. Variabilty of inspired oxygen concentration with nasal cannulas. Thorax. 1992;47:609–611. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.8.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]