Abstract

Although depression is highly comorbid with substance use disorders, little is known about the clinical course and outcomes of methamphetamine (MA) users with depressive symptoms and syndromes. In this study of MA-dependent individuals entering psychosocial treatment, we predicted that (1) depressive symptoms would decline during treatment, an effect that would vary as a function of MA use and (2) depression diagnoses post-treatment would be associated with poorer outcomes. Participants (N = 526) were assessed for depression, substance use, and psychosocial outcomes at baseline, treatment discharge, and 3-year follow-up. Depressive symptoms declined significantly during treatment, an effect that was greatest among those who abstained from MA. Major depression at follow-up was associated with poorer MA use outcomes and impairment across multiple domains of functioning. The findings highlight the relationship of depressive symptoms and diagnoses to treatment outcomes, and suggest a need for further studies of depression in populations using MA.

Keywords: Methamphetamine dependence, depression, comorbidity

Studies of drug abuse trends indicate that methamphetamine (MA) use has increased to epidemic proportions and is currently a significant public health problem. MA is the second leading substance of abuse following marijuana worldwide, with 35 million adults reporting nonmedical use of MA and amphetamine-like stimulants (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2005). Despite differences in the basic mechanisms of action of MA and cocaine, their psychiatric complications share commonalities. Both cocaine and MA can cause mood disturbances and psychosis during active use and withdrawal, and symptoms can persist in early abstinence (Newton et al., 2004). Although MA users are more likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis than cocaine users (Copeland and Sorenson, 2001), greater attention has been afforded to characterizing psychiatric problems and their association with treatment outcomes in cocaine users (Brown et al., 1998; Herbeck et al., 2006; Husband et al., 1996). Depression is the most common comorbid axis I disorder for individuals with drug use disorders (Grant et al., 2004), and prevalence rates of depression among stimulant users are particularly high. Recent national epidemiologic data indicate that 41.6% of adults with amphetamine use disorders and 35.7% of those with cocaine use disorders have a lifetime history of depression (Conway et al., 2006). Nevertheless, no large epidemiologic studies to date have examined depressive disorders in MA, using populations specifically. Thus, although MA use is associated with depressive symptoms (Rawson et al., 2002; Zweben et al., 2004), the prevalence of depression diagnoses in MA-dependent populations is unknown.

Prior reports of the effects of depression on treatment adherence in stimulant users are inconsistent. For example, one study found that cocaine dependent adults with lifetime depression demonstrated better adherence and abstinence rates during treatment for cocaine dependence than nondepressed individuals; however, current major depressive disorder (MDD) was not significantly related to adherence (McKay et al., 2002). Nevertheless, another study of cocaine users found that pretreatment depressive symptoms (but not diagnoses) were inversely related to days spent in treatment (Brown et al., 1998).

Substance outcomes in depressed stimulant users are similarly discrepant and are further complicated by the effects of alcohol use. For example, cocaine dependent adults with comorbid depression were found to have poorer alcohol and cocaine use outcomes 2 years post-treatment, relative to nondepressed participants (McKay et al., 2002). Likewise, at least one other study of cocaine users demonstrated that post-treatment alcohol, but not cocaine use is associated with severity of depressive symptoms after treatment (Brown et al., 1998). In contrast, in a 5-year follow-up study, those with more depressive symptoms at baseline were less likely to use cocaine or heroin post-treatment (Carroll et al., 1995; Rao et al., 2004). The discrepancies in these findings may be attributed, in part, to the measurement of depression at inconsistent timepoints across studies; the effects of depression on treatment adherence and outcomes may vary depending on whether symptoms are assessed pre- or post-treatment. Thus, an aim of the present study is to provide distinct evaluations of the utility of (a) pretreatment depression symptom severity and (b) end-of-treatment symptom severity in predicting substance outcomes.

Numerous studies have found that comorbid depression in substance-dependent individuals is associated with more severe symptomatology and impairment (Preuss et al., 2002). These findings have been partially replicated in MA users and have been found to vary as a function of the route of MA administration, with injection users reporting more severe depression and suicidality, relative to those who used other routes of administration (Zweben et al., 2004). Generally, however, depression is the most common psychiatric symptom reported regardless of route of administration. Taken together, these findings raise questions about the etiology and clinical course of these symptoms, as they relate to MA use during and after treatment.

The current investigation addresses several questions related to the role of depression in treatment outcomes for MA-dependent individuals. First, to evaluate the predictive utility of baseline depressive symptoms, we examined the relationship of pretreatment depression severity to (a) MA use at treatment discharge; (b) treatment adherence; and (c) post-treatment MA use and rates of alcohol dependence (AD). Second, we expected depressive symptoms to decrease significantly during the course of treatment and that this decrease would be greatest for those who remained abstinent during treatment. Third, to examine the association between post-treatment depressive symptoms and outcomes, we examined the relationship between depression 3 years after treatment and MA and alcohol use during follow-up. Fourth, consistent with prior work (Zweben et al., 2004), we expected that depressive disorders would be associated with injecting MA and with greater psychiatric severity and impairment across time.

METHOD

Subjects

Participants were 526 MA-dependent adults who took part in the MA Treatment Project (MTP), a randomized, controlled trial of psychosocial treatments for MA dependence described elsewhere (Rawson et al., 2004, Zweben et al., 2004). MTP participants were recruited upon entry to outpatient treatment programs in California, Montana, and Hawaii. Inclusion criteria were MA dependence, age 18 or over, ability to understand English, and ability to attend treatment. Individuals were excluded if they: exhibited medical impairment that compromised their safety as a participant; required medical detoxification from alcohol or other substances; or psychiatric impairment that warranted hospitalization or primary treatment. Although the inclusion and exclusion criteria may have restricted the range of functional disability in the sample, participant characteristics were consistent with stimulant using cohorts previously studied in psychosocial clinical trials (Rawson et al., 2000; Rawson et al., 2004). After complete description of the study to the subjects, informed consent was obtained.

The sample was assessed at baseline, treatment discharge, and at a mean of 3.1 years after treatment completion (SD = 0.48). The follow-up assessment consisted of a medical examination, a psychiatric diagnostic interview, a psychosocial interview, and administration of self-report questionnaires. Of the 587 participants who were interviewed for the follow-up study, 61 did not complete the psychiatric diagnostic component of the interview for various reasons, including: having moved out of the area, constraints due to incarceration, inability to schedule a convenient appointment, and/or declining this portion of the assessment. Thus, the final sample included 526 participants.

Procedures and Instruments

Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face assessments with participants at baseline, discharge and follow-up. Alcohol and MA use frequency in the 30 days prior to each study visit was assessed using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1980). The ASI also provides composite scores in 7 functional domains (alcohol, drug, psychiatric, medical, legal, family, employment). Urine specimens were collected at each assessment and were analyzed for MA at a central off-site laboratory. The Life Experience Timeline interview (LET) (Hillhouse et al., 2005), a measure adapted from the Natural History Interview (Hser et al., 2001) was used to quantify MA use in the follow-up period. Using the LET, substance use history is gathered using a month-by-month timeline approach that links substance use to important life events.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a 21-item self-report questionnaire (Beck et al., 1961; 1988) was given at all assessments. The BDI total score ranges from 0 to 63, with scores of 0 to 13, 14 to 19, 20 to 28, and 29 to 63 indicating minimal, mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. The brief symptom inventory (BSI), a 53-item self-report measure with demonstrated reliability and validity (Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983) was given at all assessments. The BSI provides a global assessment of psychological symptom severity and 9 primary symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Each symptom is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all present) to 4 (extremely present); subscale scores are derived by summing the item ratings and dividing by the number of items.

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a brief structured diagnostic interview for assessing DSM-IV disorders was administered to provide AD and depression diagnoses. The MINI has good reliability and demonstrated concordance with other well-validated structured diagnostic interviews (Sheehan et al., 1998, Lecrubier et al., 1997). All interviewers were trained to criterion on the MINI using standardized procedures including didactic instruction, practice interviews, and direct observation.

In the original MTP study, it was the judgment of the protocol development team that administration of a structured DSM-IV based diagnostic interview would generate excessive cost and burden on the participants. Thus, this measure was added to the study assessment battery at 3-year follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Primary outcome measures included treatment adherence, MA use, and depression severity at treatment discharge and at 3-year follow-up. Mixed model repeated measures analyses with main effects of time and depression diagnosis and the interaction among these variables were used to compare ASI and BSI scores for those with and without MDD across baseline, treatment-end, and 3-year follow-up.

Treatment adherence was a continuous variable indicating the number of weeks of scheduled treatment during which the participant attended. Substance use outcomes included: (1) use status in the 30 days prior to treatment discharge and follow-up, measured using the ASI (0 = no use; 1 = use on ≥1 day[s]) and (2) MA use frequency (i.e., number of months during which use occurred) in the follow-up period, measured by the LET. Depression severity was measured using the BDI total score. Urine samples were collected at discharge and follow-up, and served as outcomes in confirmatory analyses of the relationship between depression and self-reported substance use.

RESULTS

The original MTP sample (N = 1016) was compared with the subset of participants who were included in the current investigation (n = 526) by using t tests and χ2 tests for age, education, gender, marital status, route of MA administration, employment, and baseline ASI composite scores. In all analyses, there were no significant differences between the patients in the current study and the original MTP sample.

At 3-year follow-up, the majority of the sample was white (69%; n = 362), female (60%; n = 316), employed (60%; n = 316) and had a high school education (33% had college education or higher); average age was 33.4 (SD = 8.0). At baseline, participants reported using MA an average of 11.9 days out of the past 30 (SD = 9.6). The preferred route of administration was smoking (63%; n = 331), followed by injection drug use (27%; n = 143) and intranasal use (9%; n = 49). There were no differences in demographic or substance use characteristics among those who completed the psychiatric assessment (N = 526) relative to those who did not (n = 61).

Pretreatment Depressive Symptoms as a Predictor of Outcomes During and After Treatment

We first examined the relationship of baseline BDI scores to treatment adherence and MA use status in the 30 days prior to discharge and follow-up. A multivariate regression model controlling for demographics, pretreatment frequency of MA and alcohol use and route of MA administration revealed that depression severity and treatment adherence were inversely related (β = −0.18, SE = 0.07; p = 0.01). Depression severity was significantly associated with self-reported MA use status in the 30 days before discharge (t = 2.80, p < 0.01); those who used MA in the month preceding discharge had higher BDI scores (M = 13.7. SD = 9.5) relative to those who abstained (M = 7.7, SD = 8.1). However, logistic regression analyses revealed that baseline BDI scores did not predict self-reported MA abstinence status in the 30 days prior to follow-up (z = 1.71, p = 0.09). All findings with regards to the relationship between baseline BDI and MA use outcomes were replicated using urine test data as outcomes.

We next examined the relationship of baseline BDI scores to AD diagnoses at follow-up. Baseline BDI scores were significantly higher among those with AD (n = 80; 15.2%) relative to those without AD (t = −2.8, df = 524, p < 0.01).

Changes in Depression During Treatment

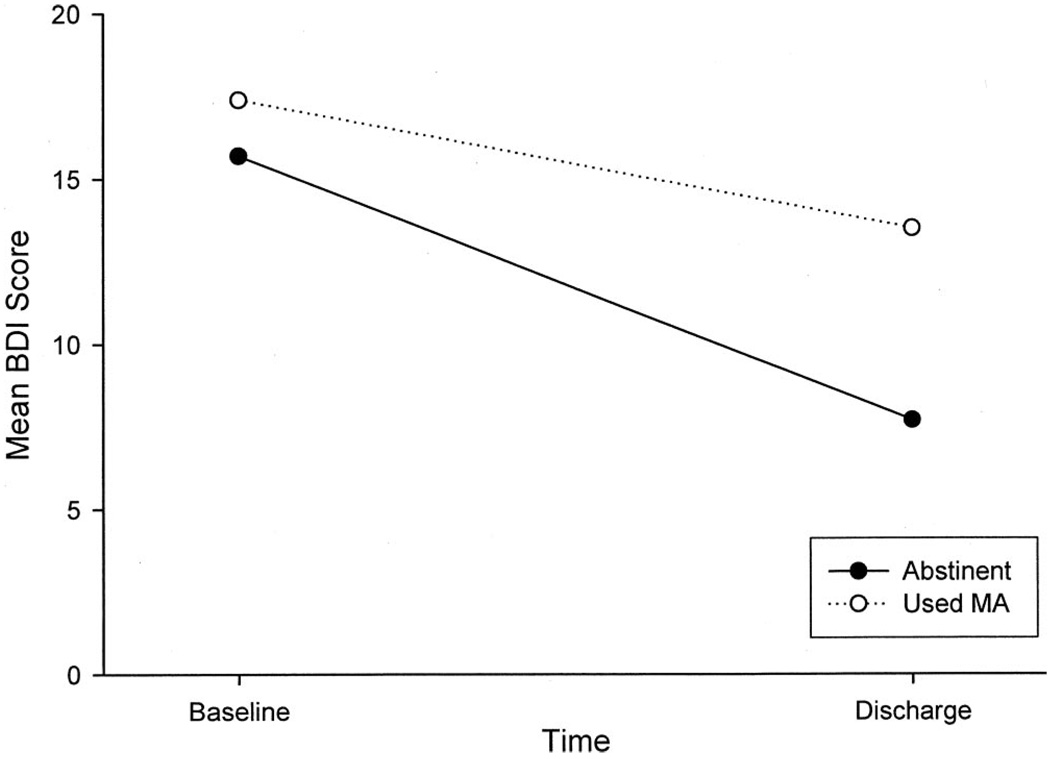

Overall, BDI scores changed significantly during treatment (t = −13.9, df = 524, p < 0.0001) with baseline scores (M = 16.5, SD = 10.2) higher than end-of-treatment scores (M = 10.2, SD = 9.2). To investigate the clinical course of these symptoms in relation to that of MA dependence, we next examined whether the magnitude of change in depressive symptoms varied as a function of MA use status in the 30 days before discharge. A multivariate regression model controlling for demographics and frequency and route of MA administration revealed that the reduction in depressive symptoms among those who reported abstinence from MA in the month before discharge was significantly greater (β = 5.1, SE = 0.69) than that observed in those who used MA (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). Results were replicated when comparing those who tested positive for MA on urine test at discharge to those whose tests indicated abstinence.

FIGURE 1.

Mean total BDI score as a function of time, separated by self-reported MA use status during the 30 days before treatment discharge (Abstinent = no MA use; Used MA = 1 or more days of MA use during the 30 days before discharge).

Depression Diagnoses and Severity at Follow-Up

Overall, 15.2% of the sample at 3-year follow-up met current MDD criteria. A significantly greater proportion of those who reported using MA during the month preceding follow-up were diagnosed with MDD (25.9%; n = 41) relative to those who were abstinent (10.6%; n = 39), χ2 = 20.20, df = 1, p < 0.0001; OR = 2.95; CI = 1.8 to 4.8. Moreover, those with MDD used MA more frequently during the follow-up period (β = 6.0, SE = 1.69; p < 0.0001) than those without MDD. Lifetime MDD and dysthymic disorder were not significantly associated with MA use in any analyses; thus, the remaining analyses focused on current MDD.

Follow-up BDI scores were significantly related to route of MA administration; injectors reported more depressive symptoms than those who used any other route of administration, t = −2.4, df = 524, p < 0.05. Moreover, the odds of being an injection user were significantly greater among those with current MDD (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.2–3.2) relative to those without this diagnosis.

We examined the association between MDD at follow-up and several pretreatment substance use variables using t tests. MDD diagnosis was not significantly related to pretreatment MA use frequency, age of first MA use, number of years of lifetime MA use, or the ASI drug composite.

The relation of MDD at follow-up to demographic variables was evaluated using t tests and chi square analyses. MDD was not significantly associated with age, ethnicity, marital status, or employment, but a marginally significant relationship emerged between MDD diagnosis and gender (χ2 = 3.87, df = 1, p = 0.05) indicating that a greater proportion of women in the overall sample (n = 56; 17.7%) than men (n = 24; 11.4%) met MDD criteria.

Participants with AD were compared with those without AD for current MDD and post-treatment depression severity. Those with AD were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with current MDD (χ2 = 5.34, df = 1, p = 0.02). Likewise, among those with MDD, individuals with a concurrent AD diagnosis evidenced higher BDI scores relative to those without this diagnosis both at discharge (M = 12.7 vs. M = 9.8; t = 2.33, df = 524, p = 0.02) and follow-up (M = 13.3 vs. M = 8.4; t = −4.34, df = 524, p < 0.0001).

Association of Depression With Other Psychosocial, Psychiatric, and Substance use Variables

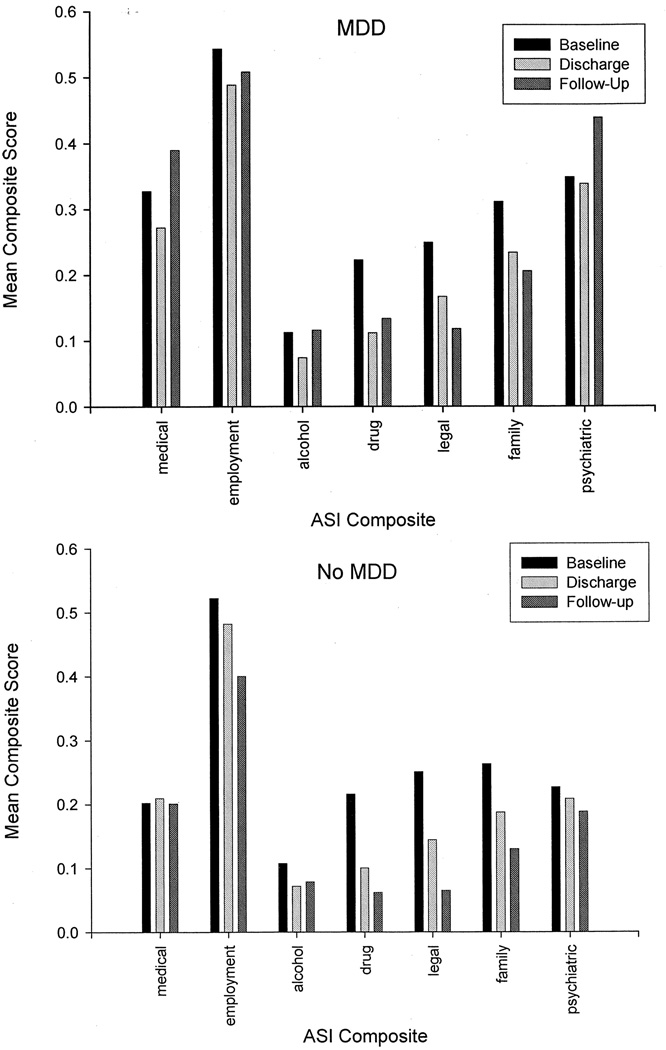

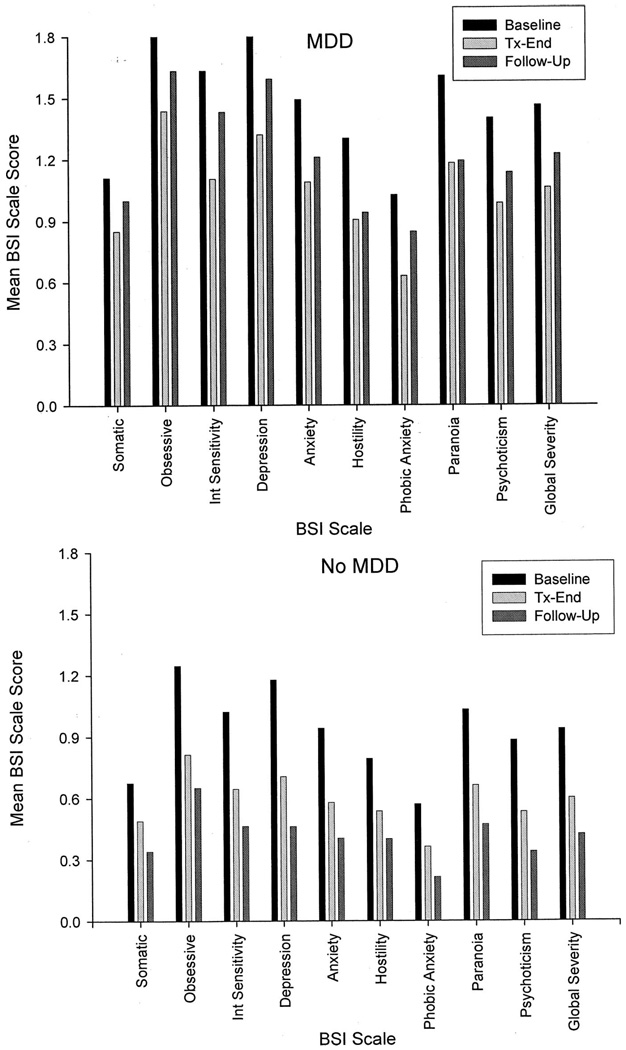

ASI composite scores and BSI scale scores at baseline, discharge and follow-up for those with and without MDD are plotted in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively, and the results of mixed-model repeated measures analyses testing the effects of time, depression diagnosis, and their interaction are provided in Table 1. Controlling for demographics, pretreatment MA use frequency, and route of administration, analyses revealed a significant time × depression diagnosis interaction on 4 of the 7 ASI composites (alcohol, drug, employment, and psychiatric) and 7 of the 10 BSI scales (somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, phobic anxiety, psychoticism, and global severity). All interactions indicated that those with MDD reported problems of significantly greater and increasing severity over time in all areas.

FIGURE 2.

Mean ASI composite scores as a function of time among MA dependent adults with (N = 80; upper panel) and without (N = 446; lower panel) MDD at 3-year follow-up.

FIGURE 3.

Mean BSI scale scores as a function of time among MA dependent adults with (N = 80; upper panel) and without (N = 446; lower panel) MDD at 3-year follow-up.

TABLE 1.

Changes in Psychosocial, Psychiatric, and Substance-Related Impairment Among MA Dependent Adults at 3-year Follow-Up: Linear Mixed-Effects Models

| Depression Diagnosis | Time | Depression × Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Brief symptom inventory (global) | 0.38 | <0.001 | −0.11 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.004 |

| Depression | 0.42 | <0.001 | −0.16 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.43 | <0.001 | −0.12 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Hostility | 0.44 | <0.001 | −0.09 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.40 | <0.001 | −0.12 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.002 |

| Obsessive | 0.42 | <0.001 | −0.13 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.004 |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.50 | <0.001 | −0.12 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.29 | <0.001 | −0.08 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Psychoticism | 0.38 | <0.001 | −0.12 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Somatization | 0.30 | <0.001 | −0.07 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Addiction severity index | ||||||

| Psychiatric composite | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.01 | <0.001 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Medical composite | 0.04 | 0.26 | −0.00 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Employment composite | −0.04 | 0.22 | −0.02 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Alcohol composite | −0.00 | 0.78 | −0.00 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Drug composite | −0.01 | 0.20 | −0.03 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Legal composite | −0.01 | 0.63 | −0.04 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Family composite | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.03 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, the prevalence of depressive disorders in MA users was moderate relative to that observed in cocaine users (Brown et al., 1998) but notably higher than prevalence estimates of MDD in the general population (Hasin et al., 2005). As predicted, depressive symptoms declined during the course of treatment in the overall sample, with greater reductions among those who abstained from MA during treatment relative to those who used; abstainers shifted from clinically relevant symptom levels at baseline to the normal or minimal symptom range at discharge.

Pretreatment depression severity predicted poorer treatment adherence and MA use outcomes at treatment-end, but did not predict longer term MA use 3 years post-treatment. On the other hand, depression severity at treatment-end was positively related to MA use in the prior month. Likewise, the presence of MDD at follow-up was associated with MA use during the follow-up period and the month prior to the assessment. Finally, consistent with extant literature (Zweben et al., 2004), depression severity at follow-up varied as a function of route of MA administration, with injectors reporting significantly more symptoms than smokers and intranasal users.

Unlike prior studies of cocaine (Carroll et al., 1995) and heroin (Rao et al., 2004) users in which pretreatment depression predicted better 5-year substance outcomes, the current findings suggest that pretreatment depressive symptoms in MA users are not predictive of longer term use outcomes. Nevertheless, consistent with prior work in cocaine users (Brown et al., 1998), depression severity predicted poorer treatment adherence. Thus, attention to depressive symptoms in stimulant users is warranted at treatment entry to optimize compliance.

Although not consistently associated with long-term substance outcomes, baseline depressive symptoms predicted psychiatric clinical course. Likewise, those with MDD at follow-up reported worsening depressivesymptoms, psychiatric severity, and psychosocial impairment from treatment discharge to follow-up relative to those without MDD. This overall pattern replicates and extends prior work in cocaine users (Leventhal et al., 2006; Schmitz et al., 2000). Identifying MA users with clinically relevant depressive symptoms is therefore important as a means of preventing this declining clinical course.

The finding that abstainers evidenced greater improvement in depression than those who used MA during treatment highlights the relationship between MA use and depression and replicates the finding in alcohol and cocaine users that length of abstinence is an important factor in the remission of depressive symptoms (Herbeck et al., 2006). Like alcohol and cocaine, MA can cause depressive symptoms in active users, which may remit spontaneously early in abstinence or have a prolonged course (Meredith et al., 2005). Thus, identifying risk factors for chronic depression in MA users is an important area for future investigation.

Baseline depression severity was higher among MA users with AD diagnoses at follow-up. Of note, the prevalence of AD in this sample was much lower (15%) than rates reported in studies of cocaine users, which range from 27% to 80% (Brown et al., 1998; Carroll et al., 1995; McKay et al., 2002). The higher prevalence of AD in cocaine users may result from the uniquely enhanced euphoria experienced when alcohol and cocaine are combined (Gossop et al., 2006), an effect mediated by the production of cocaethylene. This interaction does not occur with MA and alcohol, suggesting that alcohol use may not be as enjoyable or as effective in counteracting depressed feelings in MA users as it is in cocaine users.

Study Limitations

This study had several potential limitations. First, although prevalence estimates of depressive disorders in this study were moderate relative to other studies of stimulant users, observed rates likely underestimate the true prevalence of depressive illness in MA users given that individuals with severe psychopathology warranting primary treatment or hospitalization were excluded. Second, the MINI diagnostic interview is a brief assessment instrument that does not enable distinction of substance-induced mood disorders versus independent psychiatric disorders; thus, further investigation is needed to understand the causal relationships between MA use and depressive symptoms and syndromes. Nevertheless, recent studies have shown that the clinical course of depression is comparable in adults with substance-induced and substance-independent MDD (Nunes et al., 2006); thus the clinical implications of the findings may be similar regardless of depression etiology. Finally, since psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the MINI at follow-up but not at baseline, the potential effects of pretreatment MDD on the course of depression and MA dependence are unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the present study serves to highlight the importance of addressing depression in MA users during substance abuse treatment. Our findings suggest that (1) pretreatment depressive symptoms have clinical utility in predicting treatment adherence and chronicity of depression; (2) depressive symptoms and syndromes at treatment discharge and follow-up are consistently associated with MA use within a proximal (i.e., 30-day) timeframe; (3) abstinence from MA is associated with a decline in depressive symptomatology; and (4) MDD is associated with greater overall impairment and psychiatric symptomatology in MA users. Future investigation is warranted to further elucidate the depression-MA use relationship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank for the treatment and research staff at the participating community-based center sites, as well as acknowledge the support of the study investigators in each region. Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors: M. Douglas Anglin, PhD; Joseph Balabis, BA; Richard Bradway; Alison Hamilton Brown, PhD; Cynthia Burke, PhD; Darrell Christian, PhD; Judith Cohen, PhD, MPH; Florentina Cosmineanu, MS; Alice Dickow, BA; Melissa Donaldson; Yvonne Frazier; Thomas E. Freese, PhD; Cheryl Gallagher, MA; Gantt P. Galloway, PharmD; Vikas Gulati, BS; James Herrell, PhD, MPH; Kathryn Horner, BA; Alice Huber, PhD; Martin Y. Iguchi, PhD; Russell H. Lord, EdD; Michael J. McCann, MA; Sam Minsky, MFT; Pat Morrisey, MA, MFT; Jeanne Obert, MFT, MSM; Susan Pennell, MA; Chris Reiber, PhD, MPH; Norman Rodrigues, Jr; Janice Stalcup, MSN, PH; S. Alex Stalcup, MD; Ewa S. Stamper, PhD; Janice Stimson, PsyD; Sarah Turcotte Manser, MA; Denna Vandersloot, Med; Ahndrea Weiner, MS, MFT; Kathryn Woodward, BA; and Joan Zweben, PhD.

Supported by grant numbers TI 11440-01, TI 11427-01, TI 11425-01. TI 11443-01, TI 11484-01, TI 11441-01, TI 11410-01, and TI 11411-01, by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department of Heath and Human Services.

REFERENCES

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Monti PM, Myers MG, Martin RA, Rivinus T, Dubreuil ME, Rohsenow DJ. Depression among cocaine abusers in treatment: Relation to cocaine and alcohol use and treatment outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:220–225. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DS, Rubin A, Keefe CK, Black JL, Leeka JK, Phillips LA. Affective correlates of alcohol and cocaine use. Addict Behav. 1992;17:517–524. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90061-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ. Differential symptom reduction in depressed cocaine abusers treated with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:251–259. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199504000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Power ME, Bryant K, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow-up status of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Psychopathology and dependence severity as predictors of outcome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Sorensen JL. Differences between methamphetamine users and cocaine users in treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Manning V, Ridge G. Concurrent use of alcohol and cocaine: Differences in patterns of use and problems among users of crack cocaine and cocaine powder. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:121–125. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcoholism and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Hser YI, Lu AT, Stark ME, Paredes A. A 12-year follow-up study of psychiatric symptomatology among cocaine-dependent men. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1974–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse M, Marinelli-Casey P, Rawson R. The LET (life experience timeline): A new instrument for collecting time-anchored natural history data. Presented at the 67th annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; Orlando, FL. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husband SD, Marlowe DB, Lamb RJ, Iguchi MY, Bux DA, Kirby KC, Platt JJ. Decline in self-reported dysphoria after treatment entry in inner-city cocaine addicts. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:221–224. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Dunbar G. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): A short diagnostic structured interview reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Mooney ME, DeLaune KA, Schmitz JM. Using addiction severity profiles to differentiate cocaine-dependent patients with and without comorbid major depression. Am J Addict. 2006;15:362–369. doi: 10.1080/10550490600860148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Pettinati HM, Morrison R, Feeley M, Mulvaney FD, Gallop R. Relation of depression diagnoses to 2-year outcomes in cocaine-dependent patients in a randomized continuing care study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith CW, Jaffe C, Ang-Lee K, Saxon AJ. Implications of chronic methamphetamine use: A literature review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13:141–154. doi: 10.1080/10673220591003605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Kalechstein AD, Duran S, Vansluis N, Ling W. Methamphetamine abstinence syndrome: Preliminary findings. Am J Addict. 2004;13:248–255. doi: 10.1080/10550490490459915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Liu X, Samet S, Matseoane K, Hasin D. Independent versus substance-induced major depressive disorder in substance-dependent patients: Observational study of course during follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1561–1567. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GR, Dasher AC, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI., Jr A comparison of alcohol-induced and independent depression in alcoholics with histories of suicide attempts. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:498–502. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SR, Broome KM, Simpson DD. Depression and hostility as predictors of long-term outcomes among opiate users. Addiction. 2004;99:579–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson R, Huber A, Brethen P, Obert J, Gulati V, Shoptaw S, Ling W. Methamphetamine and cocaine users: Differences in characteristics and treatment retention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:233–238. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Gonzales R, Brethen P. Treatment of methamphetamine use disorders: An update. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, Dickow A, Frazier Y, Gallagher C, Galloway GP, Herrell J, Huber A, McCann MJ, Obert J, Pennell S, Reiber C, Vandersloot D, Zweben J. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2004;99:708–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Stotts AL, Averill PM, Rothfleisch JM, Bailley SE, Sayre SL, Grabowski J. Cocaine dependence with and without comorbid depression: A comparison of patient characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 suppl 20:22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Accessed May 2006];World Drug Report. 2005 Available at: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/world_drug_report.html.

- Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, Galloway GP, Salinardi M, Parent D, Iguchi M. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. Am J Addict. 2004;13:181–190. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]