Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To examine factors influencing sexual activity and functioning in racially- and ethnically-diverse, middle-aged and older women.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional cohort study

SETTING

Integrated health care delivery system

PARTICIPANTS

1,977 women aged 45 to 80 years

MEASUREMENTS

Self-administered questionnaires assessed sexual desire, activity, satisfaction, and problems.

RESULTS

Of the 1,977 participants (including 876 White, 388 African American, 347 Latina, and 351 Asian women), 43% reported at least moderate sexual desire, and 60% were sexually active in the previous 3 months. Half of sexually active participants (n=969) described their overall sexual satisfaction as moderate to high. Among sexually inactive women, the most common reason for inactivity was lack of interest in sex (39%), followed by lack of a partner (36%), physical problem of partner (23%), and lack of interest by partner (11%); only 9% were inactive from personal physical problems. In multivariable analysis, African-American women were more likely than white women to report at least moderate desire (OR=1.65, 95%CI=1.25-2.17) but less likely to report weekly sexual activity (OR=0.68, 95%CI=0.48-0.96); sexually active Latina women were more likely than white women to report at least moderate sexual satisfaction (OR=1.75, 95%CI=1.20-2.55).

CONCLUSION

A substantial proportion of community-dwelling women remain interested and engaged in sexual activity into older age. Lack of a partner capable of or interested in sex may contribute more to sexual inactivity than personal health problems in this population. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported sexual desire, activity, and satisfaction may influence discussions about sexual difficulties in middle-aged and older women.

Keywords: female sexual function, aging, race/ethnicity, sexual activity

INTRODUCTION

Little is known about sexual activity and functioning as women age, despite the aging of the population. Although female sexual function is widely believed to decline with age, many women report preserved sexual activity and satisfaction in older age (1-3). At this time, we do not understand why sexual function declines in some women but not others, and there is lack of consensus about what constitutes “normal” female sexual function across the lifespan (1, 4).

A variety of factors have the potential to influence sexual function as women age, including hormonal and physiologic changes associated with menopause and chronologic aging (5-7), changes in physical or mental health (3, 8, 9), adverse effects of medications or other health interventions (10-12), and change in availability of a partner interested in and capable of sexual activity (13). Additionally, women's interest in and expectations about sexual activity may be critically influenced by their ethnic background as well as other socio-cultural factors (14, 15). To date, however, most clinical research on female sexual function has focused narrowly on biophysiologic contributors to women's sexual response, and very little research has explored sexual function in racially- and ethnically-diverse women.

To address these issues, we assessed multiple dimensions of sexual functioning in a large, population-based sample of racially- and ethnically-diverse, middle-aged and older women. Within this population, we evaluated the relationship of age, race/ethnicity, and other factors to women's interest in sex, frequency of sexual activity, and sexual satisfaction. We also examined specific sexual problems among women who were sexually active, and reasons for being inactive among women with no recent sexual activity. Our goal was to investigate the complex factors that influence sexual activity and function as women age, at a time when the population of older U.S. persons is both growing and becoming increasingly diverse.

METHODS

Study setting

This was an ancillary study to the Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study at Kaiser 2 (RRISK2), a cohort study of risk factors for urinary tract dysfunction in middle-aged and older women. Between January, 2003, and January, 2008, women were recruited from the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California, an integrated health care delivery system serving approximately 25% to 30% of the northern California population. To be eligible for this cohort, women had to be between the ages of 40 and 69 years on January 1, 1999, to have been enrolled in Kaiser since age 24, and to have had at least half their childbirths at a Kaiser facility. Women of non-white race/ethnicity were oversampled to achieve a target race/ethnicity composition of 20% African-American, 20% Latina, 20% Asian, and 40% white. Because one of the goals of the main RRISK2 study was to evaluate the impact of diabetes on urinary tract function, women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Diabetes Registry, an automated database of over 300,000 health plan members with diabetes, were also oversampled to achieve participation by at least 20% diabetic women. Furthermore, to be eligible for our ancillary study of sexual function and aging, women were required to be between 45 and 80 years of age at the time of their study visit.

Of the 6,907 potential enrollees whom we initially identified from administrative databases and attempted to contact by mail or telephone, eligibility was successfully determined for 5641 (82%). Of these women, 3270 (58%) met eligibility requirements for RRISK2. Of these eligible women, 2,270 (69%) enrolled in RRISK2; 1,977 (87%) of these enrollees were additionally eligible for and participated in our ancillary study of sexual function and aging.

Data collection

Demographic characteristics, medical and surgical history, gynecologic history, medication use, and health-related habits were assessed by self-administered questionnaires as well as in-person interviews. Race/ethnicity was assessed by asking women to self-identify as non-Latina white, Latina/Hispanic, African-American/Black, Asian, or other. Women were considered postmenopausal if they had not had a natural menstrual period in at least 12 months. Overall health status was assessed through a standard single-item self-report measure in which participants rated their overall health as “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor” (16, 17). Physical and mental functioning were assessed using the physical and mental component summary scores of the validated SF-12 Medical Outcomes Study instrument, a validated instrument that has been widely used to compare the relative burden of disease in populations and the health benefits associated with treatment (18). Scores on the SF-12 were scaled from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating better overall functioning. Women's height and weight were also measured at their study visit for calculation of body mass index in kilograms divided by meters squared (kg/m2).

Sexual activity and function were assessed using measures previously administered in other large women's health studies such as the Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (19). To ensure confidentiality, participants completed questions in private and submitted them to study personnel in sealed envelopes at their study visit. Women were first asked, “Some people have sexual relationships with men, some with women, and some with both. With whom have you had sexual relationships?” with response options including “Men only,” “Women only,” “Men and women,” and “Never had sex with a man or woman.” Availability of a sexual partner was then assessed by asking, “Do you have a spouse or sexual partner at this time?” Women were then asked whether they had had any sexual activity in the past 3 months, and, if so, about the frequency of that activity. Recognizing that women's sexual activity might not be confined to vaginal intercourse, we defined sexual activity inclusively as “any activity that is arousing to you, including masturbation.”

Participants’ sexual desire or interest, overall sexual satisfaction, and sexual problems were assessed through structured items that were drawn from the Female Sexual Function Index (20) and adapted to assess sexual function in the 3 months before each visit. Women's level of sexual desire and overall sexual satisfaction were assessed in all women regardless of sexual activity, whereas sexual problems (i.e., difficulty with arousal, difficulty with lubrication, difficulty achieving orgasm, and pain during vaginal intercourse) were assessed only among women who reported some sexual activity in the past 3 months. Women who reported no sexual activity in the past 3 months were asked to indicate their reasons for being sexually inactive, including lack of interest in sex, physical problems interfering with sex, lack of a sexual partner, physical problems of their partner, or lack of interest of their partner in sex. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in writing at the time of data collection. All study procedures were approved the institutional review boards of both the University of California San Francisco and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute.

Statistical analyses

To facilitate comparison of sexual function outcomes by age, we first compared the prevalence of 1) at least moderate sexual desire/interest, 2) at least weekly sexual activity, and 3) at least moderate sexual satisfaction across each of three age groups (45 to 54 years, 55 to 64 years, and 65 to 80 years) using tests for linear trend. We also examined univariate differences in sexual desire and activity by race/ethnicity (White, Black, Latina, and Asian), using chi-square tests. We then developed multivariable logistic regression models to identify participant characteristics associated with each of these outcomes, including age, race/ethnicity, marital status, household income, physical and mental functioning, menopausal status, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, systemic estrogen use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use, diabetes status, body mass index, and total number of medications. Potential multicollinearity in these models was examined using correlation matrices, in which all correlation coefficients were confirmed to be less than 0.60. In models assessing sexual satisfaction, we stratified women by sexual activity status, recognizing that “sexual satisfaction” may have different meanings to sexually active versus inactive women.

Among women reporting some sexual activity in the past 3 months, we examined differences in the prevalence of specific sexual problems (i.e., difficulty with arousal, orgasm, lubrication, or pain) by age category, again using tests for linear trend. Among women reporting no sexual activity, we similarly compared women's self-reported reasons for being inactive across age groups. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, NC).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 1,977 participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean (± SD) age was 57 (± 9) years, with a range of 45 to 80 years. Over half (n=1,100) were of non-white race/ethnicity, including 20% Black, 18% Latina, and 19% Asian women. Of the 365 Asian women, 70% (n=256) self-identified as East Asian, 21% (n=75) as Filipina, 5% (n=20) as Indian Subcontinent, 2% (n=6) as Southeast Asian, and 2% (n=8) as other or combination. Over two thirds of participants (n=1,331) were married or living as married.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | Participants (N=1,977) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 45 to 54 | 926 (47%) |

| 55 to 64 | 589 (30%) |

| 65 or older |

462 (23%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 876 (44%) |

| Black/African-American | 388 (20%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 347 (18%) |

| Asian/Asian-American |

365 (19%) |

| Relationship history | |

| Currently married or living as married | 1331 (67%) |

| History of sexual activity with men only | 1877 (95%) |

| History of sexual activity with women only | 25 (1%) |

| History of sexual activity with men and women |

44 (2%) |

| Income and employment | |

| Total household income < $30,000/year | 222 (12%) |

| Total household income $30,000 to 119,999/year | 1327 (72%) |

| Total household income ≥ $120,000/year | 307 (17%) |

| Working full- or part-time for pay |

1037 (53%) |

| General medical history | |

| Fair or poor self-reported overall health | 197 (10%) |

| SF-12 physical component score* | 46 (± 6) |

| SF-12 mental component score* | 45 (± 5) |

| Physician-diagnosed diabetes mellitus |

419 (21%) |

| Gynecologic history | |

| Postmenopausal† | 1623 (82%) |

| Prior hysterectomy | 187 (10%) |

| Bilateral oophorectomy |

108 (6%) |

| Current medication history | |

| 0 or 1 total medications | 704 (36%) |

| 2 total medications | 268 (14%) |

| 3 total medications | 268 (14%) |

| 4 or more total medications | 737 (37%) |

| Oral or transdermal estrogen use | 236 (12%) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use |

179 (9%) |

| Health-related habits | |

| Current smoking | 140 (7%) |

| 5 or more alcoholic drinks/week |

214 (11%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| Less than 25 | 609 (31%) |

| 25 to 29 | 588 (30%) |

| 30 to 34 | 374 (19%) |

| 35 or more | 391 (20%) |

Data are presented as number (percent) or mean (± SD). Data were missing for 1 participant for race/ethnicity, 12 for relationship status, 121 for income, 10 for functional status, and 15 for body mass index.

Scaled from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicated better overall functioning

Defined as no natural menses in at least 1 year

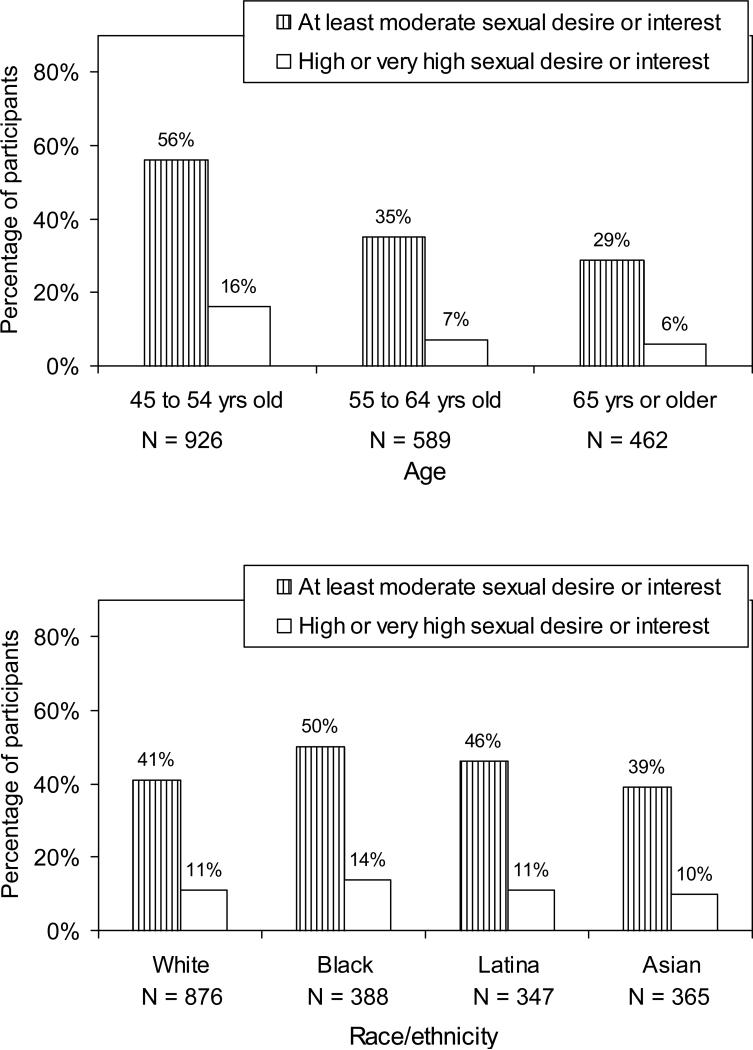

Overall, 43% (n=850) of participants indicated that their level of sexual desire or interest in the past 3 months was “moderate” to “very high.” The proportion of women with at least moderate desire or interest decreased significantly with increasing age (P for trend by age category < .001) (Figure 1A). Nevertheless, 29% (n=131) of women aged 65 or older described their level of desire or interest as at least moderate, and 6% (n=28) of these women described their desire or interest as high or very high. Self-reported desire also varied by race/ethnicity, with Black and Latina women tending to report higher levels of desire compared to White and Asian women (P for overall difference by race/ethnicity = .01; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Self-reported sexual desire and interest by A) age group and B) race/ethnicity. P for linear trend in the prevalence of at least moderate sexual desire by age < .001. P for difference in the prevalence of at least moderate sexual desire by race/ethnicity = .01.

In multivariable analysis, women were more likely to report at least moderate sexual desire or interest if they were African American versus White (OR=1.65, 95%CI=1.25-2.17), were married or living as married (OR=1.38, 95%CI=1.10-1.73), had higher scores on the physical (OR=1.17, 95%CI=1.10-1.29, per 5-point increase) or mental (OR=1.25, 95%CI=1.14-1.37, per 5-point increase) components of the SF-12, or were using systemic estrogen (OR=1.78, 95%CI=1.30-2.44); women were less likely to report at least moderate desire if they were older (OR=0.78, 95%CI=0.73-0.84) or postmenopausal (OR=0.61, 95%CI=0.45-0.82). Household income, diabetes status, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, SSRI use, total number of medications, and body mass index were not significantly associated with sexual desire or interest, although these variables were included in our model (P > .10 for all).

Sexual desire or interest was significantly associated with overall level of sexual satisfaction in the cohort. Seventy-eight percent (n=644) of women reporting at least moderate desire or interest indicated that they were at least moderately sexually satisfied, compared to only thirty-seven percent (n=321) of women reporting low, very low, or no desire or interest (P < .01).

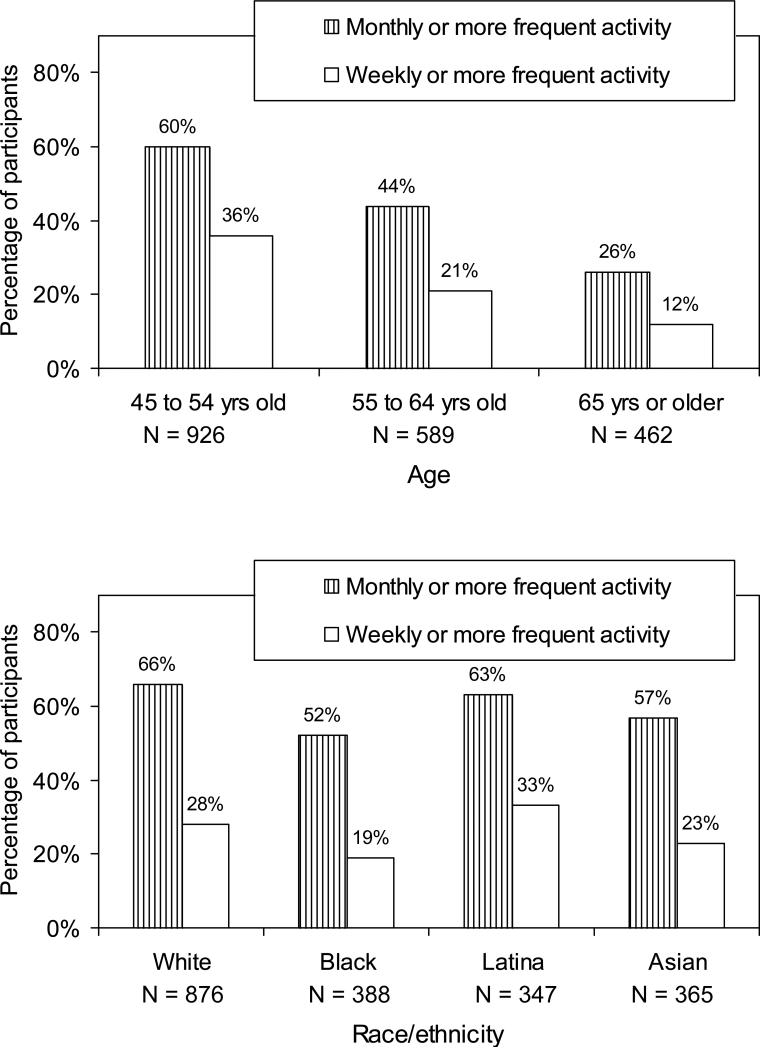

Overall, 60% (n=1180) of women reported some sexual activity in the previous 3 months. The proportion of women who were sexually active decreased significantly with increasing age (P for trend in weekly sexual activity by age category < .01; Figure 2A). Nevertheless, 37% (n=170) of women aged 65 years or older reported some sexual activity, and 12% (n=53) of these women reported at least weekly activity. Frequency of sexual activity also varied by race/ethnicity, with Black and Asian women tending to report less frequent activity, and Latina women tending to report more frequent activity, compared to White women (P for overall difference in weekly sexual activity by race/ethnicity < .01; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Self-reported frequency of sexual activity by A) age group and B) race/ethnicity. P for linear trend in at least weekly activity by age group < .001. P for difference in at least weekly activity by race/ethnicity < .001.

Among women who reported no sexual activity in the previous 3 months (n=751), the most commonly cited reason for being inactive was lack of interest in sex (39%, n=273), followed by lack of a sexual partner (36%, n=249), physical problem of the partner (23%, n=160), and then lack of interest in sex by the partner (11%, n=76). The least commonly cited reason was a physical problem of the participant herself that interfered with sexual activity (9%, n=60). Most reasons for being sexually inactive did not differ significantly by age group; however, the proportion of women reporting that a physical problem of their partner interfered with sex increased with age (33% [n=86] of women aged 65 years or older, versus 12% [n=25] of women aged 45 to 54 years; P for trend by age category < .0001).

In multivariable analysis, women were more likely to report at least weekly sexual activity if they were married or living as married (OR=3.24, 95%CI=2.40-4.37), had higher scores on the physical (OR=1.16, 95%CI=1.03-1.30, per 5-point increase) or mental (OR=1.22, 95%CI=1.10-1.37, per 5-point increase) components of the SF-12, had previously undergone hysterectomy (OR=1.92, 95%CI=1.08-3.43), or were currently using oral or transdermal estrogen (OR=1.65, 95%CI=1.17-2.33). They were less likely to report weekly activity if they were older (0.72, 95%CI=0.66-0.78), if they were African-American (OR=0.78, 95%CI=0.48-0.96) or Asian (OR=0.65, 95%CI=0.46-0.90) as opposed to white, or if they had undergone bilateral oophorectomy (OR=0.40, 95%CI=0.19-0.86). Weekly sexual activity was not significantly associated with income, diabetes status, menopausal status, SSRI use, total number of medications, or body mass index, although these variables were retained in our model (P > .10 for all).

Overall, over half of participants (n=969) indicated that they were “moderately” or “very” sexually satisfied (Table 2). The proportion of women who reported at least moderate satisfaction decreased with age, in that 55% (n=533) of those aged 45 to 54 years were moderately or very satisfied, compared with 18% (n=178) of those aged 65 years or older (P for trend with increasing age = 0.04).

Table 2.

Overall Level of Sexual Satisfaction by Sexual Activity Status, No. (%)*

| Total participants (n = 1,700)† | Sexually satisfied | P for trend by age |

| 45 to 54 years | 533 (55%) | |

| 55 to 64 years | 258 (27%) | < .001 |

| 65 years or older |

178 (18%) |

|

| Sexually active women (n = 1,165) | Sexually satisfied | P for trend by age |

| 45 to 54 years | 467 (60%) | |

| 55 to 64 years | 202 (26%) | .04 |

| 65 years or older |

103 (13%) |

|

| Sexually inactive women (n = 519) | Sexually satisfied | P for trend by age |

| 45 to 54 years | 63 (34%) | |

| 55 to 64 years | 52 (28%) | .03 |

| 65 years or older | 72 (39%) |

Participants were considered to be sexually satisfied if they reported being “moderately” or “very” satisfied overall in the past 3 months.

Data on sexual satisfaction were missing for 277 participants, including 20 sexually active participants, and 232 sexually inactive participants.

Among sexually active participants, multivariate analysis yielded several independent correlates of sexual satisfaction, including being married (OR=1.44, 95%CI=1.06-1.97), being Latina (OR=1.75, 95%CI=1.20-2.55), and having higher mental functioning scores (OR=1.16, 95%CI=1.03-1.32 per 5-point increase). Postmenopausal women were less likely to be at least moderately satisfied (OR=0.63, 95%CI=0.44-0.91), but no independent associations were observed with age, income, physical functioning, hysterectomy or oophorectomy, medication use, or body mass index (P < .10 for all).

Among sexually inactive participants, older age was associated with greater sexual satisfaction after adjusting for other characteristics (OR=1.18, 95%CI=1.03-1.36 per 5-year increase in age). Sexually inactive women also were more likely to be at least moderately satisfied if they were African-American (OR=2.24, 95%CI=1.32-3.81), had higher mental functioning scores (OR=1.25, 95%CI=1.11-1.42 per 5-point increase), or had undergone bilateral oophorectomy (OR=4.16, 95%CI=1.13-15.3). Diabetes was associated with decreased sexual satisfaction in this subset of women (OR=0.49, 95%CI=0.27-0.89), but no significant associations were observed for income, marital status, physical functioning, menopausal status, hysterectomy, medication use, or body mass index (P > .10 for all).

Over forty percent (N=496) of sexually active women reported problems with sexual activity, including low level of sexual arousal, difficulty with lubrication, difficulty with orgasm, or discomfort with vaginal penetration (Table 3). Difficulty with lubrication was more common in older versus younger sexually active women (28% of women aged 65 or older versus 17% for women under age 65 (P for trend <.0001), but the prevalence of other problems did not differ significantly by age.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Different Types of Sexual Problems Among Sexually Active Women, by Age Group

| Type of sexual problem* | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 to 54 years (N = 685) | 55 to 64 years (N = 326) | 65 years or older (N = 174) | |

| Low or very low level of sexual arousal during sexual activity | 101 (15%) | 67 (21%) | 31 (18%) |

| Lubrication difficult, very difficult, or impossible during sexual activity† | 115 (17%) | 90 (28%) | 46 (28%) |

| Achieving orgasm difficult, very difficult, or impossible | 111 (16%) | 78 (24%) | 35 (21%) |

| Moderate, high, or very high level of discomfort with vaginal penetration | 73 (11%) | 59 (18%) | 28 (16%) |

Data were missing for 13 participants on sexual arousal, 20 for lubrication, 17 for orgasm, and 15 for vaginal penetration.

P for trend in prevalence of difficulty with lubrication with increasing age <.0001

DISCUSSION

In this large, population-based sample of racially- and ethnically-diverse women, both sexual desire and frequency of sexual activity were lower in older compared to younger women. Nevertheless, over a quarter of women aged 65 years and older indicated they were moderately or highly interested in sex, and over a third of women in this age stratum reported being sexually active in the previous 3 months. These findings indicate that a substantial proportion of community-dwelling women remain both interested and engaged in sexual activity as they age.

We found that physical and mental health functioning were more strongly associated with sexual desire and activity in middle-aged and older women than age alone, which is consistent with a recent nationally representative survey of older U.S. persons (3). These results suggest that clinicians should consider women's sexual functioning in the context of their overall physical and mental functioning, rather than considering women strictly according to age. Our study also suggests, however, that lack of a partner interested in or capable of having sex may be an even stronger contributor to sexual inactivity in this population than personal health. Consequently, clinicians need to consider the way that women's sexual problems interact with the problems of their partners as they age, and should recognize that interventions directed at improving women's sexual functioning may not substantially affect their sexual activity if partner or relationship factors do not also change.

Our results indicate that self-reported sexual desire, activity, and satisfaction in middle-aged and older women vary by race/ethnicity, independent of other demographic and clinical factors. Despite the growing diversity of the population, very little research has examined differences in sexual functioning among racially or ethnically diverse women. In one large study of women aged 40 to 55 years, African-American women reported greater frequency of sexual activity compared to white women, although they also reported lower levels of sexual desire (14). Another study of women seeking gynecologic care at a military medical center, of whom half were aged 40 years or older, found that concerns about decreased lubrication were less common among African-American compared to white women (15). Additionally, in the first data collection wave of RRISK, involving mostly middle-aged women, sexually-active African-American women reported greater satisfaction with sex compared to white women (21).

A variety of factors may contribute to racial/ethnic differences in women's self-reported sexual function, including biological differences in women's sexual response, differences in environmental factors influencing sexual activity, and cultural differences in expectations about sexual activity. Additionally, there may be important differences in women's willingness to acknowledge or report sexual activity and problems across racial/ethnic groups. Further research is needed to explore possible mediators of differences in self-reported sexual functioning by race/ethnicity, as well as the way these differences change across the age spectrum, to help guide clinicians in discussing sexual problems with women of diverse backgrounds.

Our study also points to complex interactions between aging, sexual activity, and subjective sexual satisfaction among women in the community. Among sexually active women in this cohort, self-perceived sexual satisfaction initially appeared to decrease with increasing age; however, age was no longer associated with satisfaction after adjustment for other factors. In contrast, among women reporting no recent sexual activity, older women appeared more likely than younger women to be satisfied with the state of their sex lives after adjusting for other characteristics, a trend which may reflect a change in expectations about sex in older age.

Interestingly, we did not find that the prevalence of sexual problems such as low sexual arousal or difficulty reaching orgasm increased substantially with age among sexually active women. Other researchers noting a lack of relationship between aging and self-reported sexual problems have hypothesized that women may experience less personal distress about sexual dysfunction as they age (22). Nevertheless, studies have also found that a third or more of women aged 65 and older are interested in discussing sexual concerns with their health care providers, and most older women who discuss sexual problems with a provider find these discussion to be helpful (23, 24).

Our study benefits from a large, population-based sample of middle-aged and older women, oversampling of women from racially- and ethnically-diverse backgrounds, assessment of multiple dimensions of sexual functioning, and evaluation of a broad range of demographic and clinical variables with the potential to influence sexuality as women age. Nevertheless, several important limitations of this research should be noted. First, this was a cross-sectional study, and we were unable to examine longitudinal change in sexual activity and function over time. To date, there have been very few longitudinal studies of female sexual function, most of which have focused exclusively on the menopausal transition (7, 22). Second, although our measures have been used successfully in other women's health outcome studies and were adapted from the previously validated Female Sexual Function Index, we do not currently have data on the sensitivity and reliability of the entire instrument. Additional research using other sensitive instruments may help confirm these findings.

Additionally, the RRISK 2 cohort purposefully oversampled diabetic women, and thus our findings may not be generalizable to the population of women at large. Nevertheless, we did not find that diabetes was significantly associated with most aspects of women's sexual function, reducing the likelihood that our results were biased by this sampling frame. Our cohort also included long-time enrollees in an integrated health care system, and previous research has suggested that the very wealthy and the very poor may be underrepresented in this population (25). Given that household income did not emerge as a significant independent predictor of sexual desire, activity, or satisfaction, however, it is also unlikely that underrepresentation of those at either income extreme could have substantially biased our findings. Finally, while this study included over 450 women who were aged 65 years and older, elderly women did not comprise the majority of our study population, and future research on the relationship of aging to female sexuality may benefit from oversampling of women in their eighth, ninth, and tenth decades of life.

In summary, although sexual desire and activity appear to decline with age, a substantial proportion of community-dwelling women remain interested and engaged in sex into older age. Lack of a partner interested in or capable of sexual activity may contribute more to sexual inactivity than personal health problems in this population. Self-reported sexual functioning in middle-aged and older women varies by race/ethnicity, and further research is needed to assess how these differences they may influence medical discussions about sexual functioning in women of diverse backgrounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study at Kaiser was funded by the National Institutes Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant # DK53335 & the NIDDK/Office of Research on Women's Health Specialized Center of Research Grant # P50 DK064538. Dr. Huang is supported by KL2 Grant RR024130 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH and NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award for Medical Research.

The Reproductive Risks of Incontinence Study at Kaiser was funded by the National Institutes Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant # DK53335 & the NIDDK/Office of Research on Women's Health Specialized Center of Research Grant # P50 DK064538. Dr. Huang is supported by KL2 Grant RR024130 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award for Medical Research. This paper was presented at the national scientific meeting of the Society for General Internal Medicine in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2008.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Dr. Huang has received support for research related to vaginal atrophy via contracts with the University of California, San Francisco from Bionovo, Inc. and Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Subak has received support for research related to urinary incontinence via contracts with the University of California, San Francisco from Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Kuppermann is a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., where she is providing input into the development of a measure of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Dr. Brown has received support for research related to urinary incontinence via contracts with the University of California, San Francisco from Pfizer, Inc.

Sponsor's Role: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NIH or any other organization. No funders had any role in the design or conduct of this study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. As primary author, Dr. Huang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tannenbaum C, Corcos J, Assalian P. The relationship between sexual activity and urinary incontinence in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1220–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addis IB, Ireland CC, Vittinghoff E, et al. Sexual activity and function in postmenopausal women with heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:121–127. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000165276.85777.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gierhart BS. When does a “less than perfect” sex life become female sexual dysfunction? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:750–751. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000204866.43734.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR. The impact of hormones on menopausal sexuality: A literature review. Menopause. 2004;11:120–130. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000075502.60230.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarrel PM. Psychosexual effects of menopause: Role of androgens. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:S319–24. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70727-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Burger H. Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertil Steril. 2001;76:456–460. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handa VL, Harvey L, Cundiff GW, et al. Sexual function among women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leiblum SR, Koochaki PE, Rodenberg CA, et al. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the Women's International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS). Menopause. 2006;13:46–56. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000172596.76272.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuppermann M, Summitt RL, Jr., Varner RE, et al. Sexual functioning after total compared with supracervical hysterectomy: A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1309–1318. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000160428.81371.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers RG, Kammerer-Doak D, Darrow A, et al. Does sexual function change after surgery for stress urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse? A multicenter prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen RC, Lane RM, Menza M. Effects of SSRIs on sexual function: A critical review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:67–85. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avis NE, Zhao X, Johannes CB, et al. Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: Results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause. 2005;12:385–398. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000151656.92317.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nusbaum MM, Braxton L, Strayhorn G. The sexual concerns of african american, asian american, and white women seeking routine gynecological care. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:173–179. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med. 1996;24:218–224. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farivar SS, Cunningham WE, Hays RD. Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 Health Survey, V.I. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subak L, Wing R, Smith West D, et al. Weight loss for urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:481–490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addis IB, Van Den Eeden SK, Wassel-Fyr CL, et al. Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:755–764. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000202398.27428.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes R, Dennerstein L. The impact of aging on sexual function and sexual dysfunction in women: A review of population-based studies. J Sex Med. 2005;2:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nusbaum MR, Singh AR, Pyles AA. Sexual healthcare needs of women aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith LJ, Mulhall JP, Deveci S, et al. Sex after seventy: A pilot study of sexual function in older persons. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1247–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: Validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]