Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effect of bifocal soft contact lenses on the accommodative errors (lags) of young adults. Recent studies suggest that bifocal soft contact lenses are an effective myopia control treatment although the underlying mechanism is not understood.

Methods

Accommodation responses were measured for four target distances: 100, 50, 33 and 25 cm in 35 young adult subjects (10 emmetropes and 25 myopes; mean age, 22.8 ± 2.5 years). Measurements were made under both monocular and binocular conditions with three types of lenses: single vision distance soft contact lenses (SVD), single vision near soft contact lenses (SVN; + 1.50 D added to the distance prescription) and bifocal soft contact lenses (BF; + 1.50 D add).

Results

For the SVD lenses, all subjects exhibited lags of accommodation, with myopes accommodating significantly less than emmetropes for the 100 and 50 cm target distances (p < 0.05). With the SVN lenses, there was no significant difference in accommodative responses between emmetropes and myopes. With the BF lenses, both emmetropic and myopic groups exhibited leads in accommodation for all target distances, with emmetropes showing significantly greater leads for all distances (p < 0.005).

Conclusions

Overall, myopes tended to accommodate less than emmetropes, irrespective of the contact lens type, which significantly affected accommodation for both groups. The apparent over-accommodation of myopes when wearing the BF contact lenses may explain the reported efficacy as a myopia control treatment, although further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism underlying this accommodative effect.

Keywords: accommodation, accommodative lag, contact lenses, myopia, spherical aberration

Introduction

The aetiology of myopia has been studied extensively, with the relative importance of heredity vs environmental influences being the subject of on-going debate for the more common juvenile (early)- and young adult (late)-onset forms of myopia. The well-established association between myopia progression and near work has led to speculation that the larger accommodative lags reported in myopes may be an important factor in its pathogenesis (reviewed in Rosenfield and Gilmartin, 1998; Saw, 2003). This conclusion is also consistent with reports of robust responses to hyperopic defocus, imposed experimentally in animal myopia studies, with myopia being the end result for all species tested to date (Wallman and Winawer, 2004).

Based on the premise that the development of myopia is triggered by hyperopic defocus arising from reduced accommodation during near tasks, both bifocal spectacles (Goss and Grosvenor, 1990; Fulk et al., 2000) and progressive addition spectacle lenses (PALs) (Leung and Brown, 1999; Edwards et al., 2002; Gwiazda et al., 2003) have been investigated in clinical trials, as treatments to slow the rate of myopia progression in children. In the largest of these studies, the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET) study (Gwiazda et al., 2003), a small but statistically significant treatment effect (slowed progression) was reported with PALs. Nonetheless, this effect was observed only during the first year of the 3-year study and was too small to be considered clinically significant, although further analyses of the COMET study data showed better effects on individuals with larger accommodative lags in combination with near esophoria (Gwiazda et al., 2004).

The effect of optically undercorrecting myopia on its progression rate has also been assessed in two small-scale studies, with paradoxical results in one case (Chung et al., 2002), and no statistically significant effect in the other (Adler and Millodot, 2006). Subjects were under-corrected by approximately + 0.75 D in the first case and + 0.50 D in the second case. The closest parallel in animal studies involves the use of positive lenses to impose myopia for distance vision, this treatment slowing eye growth. However, as noted above, these studies have also described increased ocular elongation with imposed hyperopia. Thus, a possible explanation for the cited human studies is that the level of undercorrection was insufficient to significantly reduce accommodative lags. The latter explanation is consistent with the apparent benefit, albeit small, of bifocal and progressive spectacle lenses incorporating adds in the range of + 1.50 to + 2.00 D, and the monocular slowing of myopia progression in a monovision spectacle correction trial (Phillips, 2005), in which the dominant (distance) eye was fully corrected and the fellow eye either left uncorrected or corrected to keep the refractive imbalance ≤2.00 D. The fellow eyes showed significantly slower progression in the latter study.

Although the rationale for prescribing a near addition (add) for control of myopia progression is to reduce the accommodative demand, and consequently also the lag of accommodation, in the cited clinical trials no measurements were made of the effects of prescribed near adds on the subjects’ accommodative responses, either prior to, or over the course of such studies. Nonetheless, the acute effects of near adds, measured in three independent studies, are consistent with the rationale for their use. In one such study, the effects of adds, ranging from + 0.75 to + 2.00 D, on the accommodative responses of ‘youngish’ adults (17– 40 years old; seven emmetropes, 17 myopes and four hyperopes), were assessed (Rosenfield and Carrel, 2001). When viewing a target binocularly at 40 cm, all subjects manifested leads of accommodation that increased monotonically with larger adds. Similar results are reported in the other two studies, both of which involved young near-emmetropic adults. In one case, subjects were tested with + 2.00 and + 3.00 D spectacles; all over-accommodated while reading at 33 cm (Howland et al., 2002). In the second case, positive lenses of + 1.00 and + 2.00 D in power were found to reduce the lag of accommodation under monocular viewing conditions and reverse it, creating a lead of accommodation, under binocular conditions (Seidemann and Schaeffel, 2003). In the study by Rosenfield and Carrel (2001), which compared the responses of emmetropes and myopes, no significant difference between these refractive groups was found.

Recent clinical studies investigating the effect of bifocal soft contact lenses on myopia progression in children and young adults (Aller, 2000; Aller and Grisham, 2000; Aller and Wildsoet, 2006, 2007) have reported much greater treatment effects than seen in related spectacle lens studies. That the young subjects in previous bifocal and PAL spectacle trials did not use the reading portion of their spectacles correctly is one of a number of possible explanations for the poorer results in these trials, being consistent with observations that children do not consistently use the near addition portion of their spectacles during reading (Hasebe et al., 2005).

A number of studies have reported larger lags of accommodation in myopes compared with emmetropes (McBrien and Millodot, 1986; Gwiazda et al., 1993, 1995; Abbott et al., 1998; Vera-Diaz et al., 2002; Nakatsuka et al., 2005), and a recent study found accommodative lag to be an independent predictor of myopic progression in both juvenile-onset and late-onset myopes (66% and 77%, respectively, showed significant progression), as well as in non-myopes (44% of whom became myopic) (Allen and O’Leary, 2006). However, not all studies have yielded confirmatory evidence of larger lags of accommodation in myopes compared with emmetropes (Nakatsuka et al., 2003; Seidel et al., 2005; Harb et al., 2006). Inter-study differences in the experimental protocols used to measure accommodative lags are thought to be a confounding factor. There is also on-going debate as to whether such increases in accommodative lags occur prior to the onset of myopia, consistent with a causal effect, or occur after onset, as a consequence of the myopic changes (Rosenfield et al., 2002; Mutti et al., 2006).

The purpose of the current study was to assess the effect of bifocal soft contact lenses on the accommodative responses of young adult emmetropes and myopes. Specifically, we sought to confirm observations by others that myopes have higher accommodative lags than emmetropes and to investigate whether bifocal contact lenses are effective in correcting such lags. Such evidence would help to explain their apparently greater efficacy as a myopia control treatment and support their more extensive testing in a controlled clinical trial.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-five young adult subjects (mean age, 22.8 ± 2.5 years) participated in the study; 10 were emmetropic [mean spherical equivalent refractive error (SE), −0.09 ± 0.42 D] and 25 were myopic (mean SE, −3.06 ± 1.34 D), based on non-cycloplegic autorefractor measurements (Grand Seiko WR-5100K; Grand Seiko Co. Ltd, Hiroshima, Japan). Astigmatism was limited to <−1.00 D, and anisometropia to <2.00 D. All subjects had normal corrected visual acuity (20/20 or better) and no binocular vision anomalies.

The study protocol conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of California, Berkeley institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from the participants after the nature and possible complications of the study were explained in writing.

Accommodation measurement protocol

A Grand Seiko WR-5100K refractometer was used to measure accommodative responses at four different near distances: 100, 50, 33 and 25 cm, and measurements were also taken under distant viewing conditions. Reported accommodative responses represent the average of five consecutive refractometer readings. The accommodation target was a high-contrast Maltese cross positioned on the subject’s midline in all cases. Under binocular conditions, both eyes viewed the target but only the non-dominant eye was measured. Under monocular conditions, only the dominant eye viewed the target and the consensual response of the fellow eye was measured through an infrared transmitting filter (700 nm cut-off wavelength), which also served to occlude that eye. Ocular dominance was determined by a sighting test.

Contact lens conditions

Accommodation measurements were made with subjects wearing each of three different types of soft contact lenses: (1) single vision distance (SVD) contact lenses, (2) simultaneous vision bifocal (BF) contact lenses (+ 1.50 D near addition) and (3) single vision near (SVN) contact lenses (+ 1.50 D added to the distance prescription, to match the BF add). The optical design of the BF contact lens consisted of a 2 mm diameter central distance zone with five alternating near and distance zones, extending over an 8 mm diameter optic zone. Single vision lenses belonged to the same lens series. Although the prescriptions of the emmetropes were negligible, all were fitted with contact lenses for accommodation measurements, to control for any effect of the lenses on the refractometer measurements; those with plano prescriptions wore + 0.25 D lenses as their distance prescription.

Our primary interest was in how bifocal (BF) soft contact lenses affect accommodation, specifically, whether they reduce accommodative lags. However, we were unable to record valid readings through the BF lenses with our refractometer, because of the discontinuities in optical power across them. As a solution to this problem, subjects were tested with a monocular BF lens on one eye, which was used to view the target, and consensual responses were recorded from the occluded, fellow eye, which wore an SVD lens. For comparison, we made both monocular and binocular measurements with the SVD and SVN lenses. For the latter monocular conditions, measurements were limited to consensual responses.

The inclusion of SVN lenses served two purposes. First, by comparing the responses under monocular and binocular conditions with the SVN lenses, it allowed the effect on accommodative responses of disrupting binocular vision, unavoidable in measurements with the BF lens, to be evaluated. Differences in responses recorded under monocular and binocular conditions may occur because of the elimination of convergence influences on accommodation under monocular conditions (Schor, 1999). Second, the optical design of the BF lens may independently affect accommodation. For example, it is likely that the effective add of the BF lenses will vary between subjects, as the improvement in visual performance at near with simultaneous vision BF contact lenses may be due to either actual bifocality or to an increase in the depth of focus, the latter being pupil size-dependent (Martin and Roorda, 2003).

Data analyses

Accommodative errors, defined mathematically as the difference between the accommodative demand, adjusted for any near addition present during measurement, and the accommodative response, were calculated for all data sets. For the SVD and BF lenses, refractometer readings were taken as direct measures of accommodative responses. However, refractometer readings obtained with the SVN lenses included the near addition provided by them; thus for each subject, the reading for the distance target measured through the same lenses was subtracted from each of the corresponding near target distances, to obtain the respective accommodative responses. The BF lens was assumed to provide the same near add as the SVN lens, i.e. + 1.50 D. Thus, for the 25 cm target distance, the demand was −2.5 D for both the SVN and BF lenses compared with −4 D for the SVD lenses, and the comparable values for the 33 and 50 cm distances were −1.5 vs −3 D and −0.5 vs −2 D. For the 100 cm target distance, the accommodative demand was 1 D for the SVD lenses and assumed to be 0 D for both the SVN and BF lenses. Because accommodation renders eyes relatively more myopic (negative refractometer readings), lags, i.e. under-accommodation relative to the target demand, will have negative values while over-accommodation or leads of accommodation will have positive values.

Paired t-tests were used to compare accommodative responses measured under binocular and monocular conditions. Differences in monocular accommodative errors, between emmetropes and myopes, were assessed using Student’s t-tests, for both the SVD and SVN lenses, and the Aspin–Welch unequal variance t-test for the BF lenses (for all viewing distances). Repeated measures anovas were used to compare the effects of the different corrective lenses on the monocular accommodative errors, for both groups, with the Bonferroni adjustment for all paired comparisons (for all viewing distances).

Results

Overall, the myopes generally accommodated less than the emmetropes, irrespective of the lens type worn and for all viewing distances. However, the inclusion of a near addition reduced the lag and in some cases, leads rather than lags of accommodation were seen. The results for monocular testing conditions are summarized graphically in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

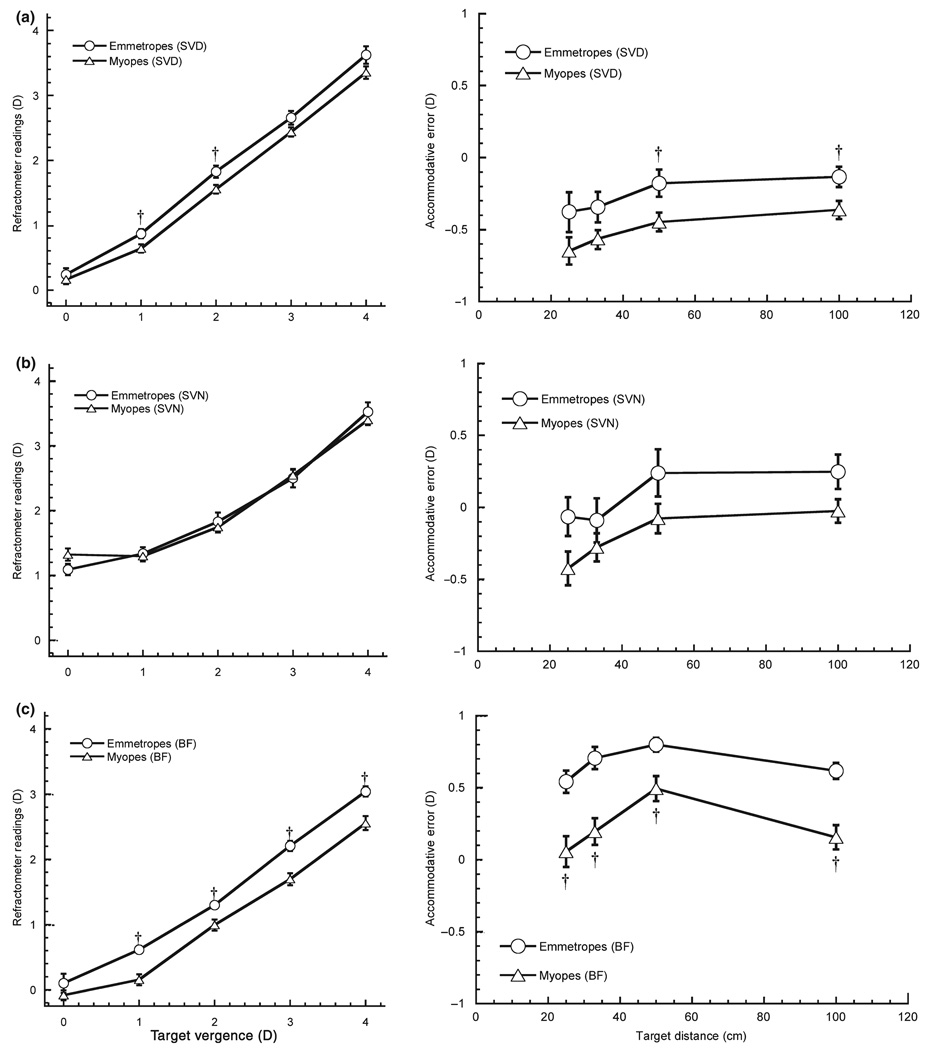

Figure 1.

Refractometer readings (left panel) and accommodative errors (right panel; lags or leads; mean ± S.E.) measured through either (a) single vision distance contact lenses (SVD), (b) single vision near contact lenses (SVN), or (c) bifocal contact lenses (BF). Emmetropes consistently exhibited less accommodative lag (negative values) and/or more lead (positive values) than myopes. † significant intergroup differences (p < 0.05).

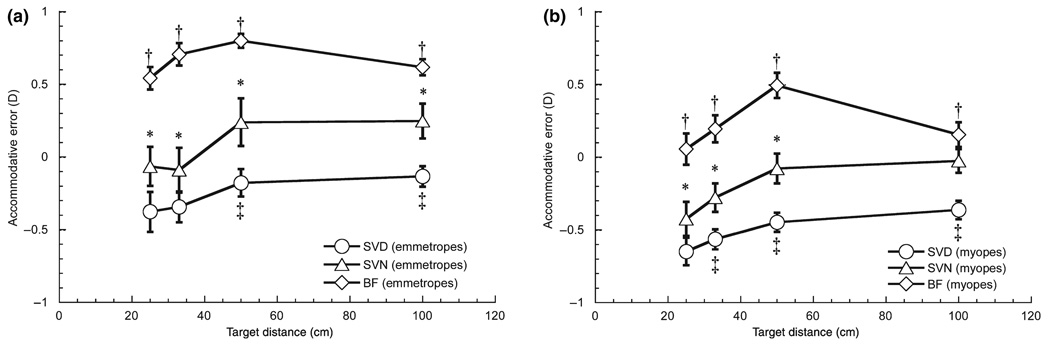

Figure 2.

Data from Figure 1 replotted to contrast the effect of lens type on accommodation for (a) emmetropes and (b) myopes. Single vision near (SVN) and bifocal (BF) lenses reduced accommodative lags and/or resulted in accommodative leads; differences significant for single vision distance (SVD) vs BF († p < 0.017), SVD vs SVN (‡ p < 0.017); SVN vs BF (* p < 0.017).

For all three lens types, accommodative responses increased with increased target vergence overall, although there was minimal response to the 1 D vergence demand with the SVN lens and the range of responses was reduced for both the SVN and BF lenses compared with that of the SVD lenses (compare Figure 1a vs. Figure 1b,c, left panel). The accuracy of these accommodative responses was quantified in terms of accommodative errors. For the SVD lenses (Figure 1a, right panel), all subjects exhibited lags of accommodation for all target distances, with the myopes recording larger lags than the emmetropes. The differences between the two groups are also statistically significant for the 50 and 100 cm target distances (p < 0.05). With the SVN lenses (Figure 1b, right panel), the myopes again showed lags of accommodation for all target distances. On the other hand, the emmetropes exhibited leads for the two farthest distances (50 and 100 cm), although they again exhibited lags for the two closest target distances (25 and 33 cm). However, these differences in accommodative responses between the two groups are not statistically significant. With the BF lenses (Figure 1c, right panel), both the emmetropes and myopes exhibited leads of accommodation at all target distances, with the differences between the two groups being statistically significant for all distances (p < 0.005).

Compared with the accommodative lags recorded with the SVD lenses, both the SVN and BF lenses produced positive shifts in accommodative errors for both the myopic and emmetropic groups. To better illustrate these effects of lens design on accommodation performance, the data shown in Figure 1 are replotted in Figure 2, organized by refractive error group. For the emmetropic group (Figure 2a), the differences in accommodative errors recorded with the SVN lenses compared with those recorded with the SVD lenses are statistically significant only for the two farthest target distances, 50 and 100 cm (p < 0.017), while the equivalent differences for BF compared with both the SVD and SVN lenses are significantly different for all target distances (p < 0.017). For the myopes (Figure 2b), differences between accommodative errors with the SVN lenses compared with the SVD lenses are statistically significant for all but the closest target distance (i.e. 33, 50 and 100 cm; p < 0.017). There are significant differences in accommodative errors for all target distances (p < 0.017) for the SVD compared with the BF lenses; for the SVN compared with the BF lenses there are significant differences in accommodative errors for the three closest target distances, 25, 33 and 50 cm.

For reasons explained in the Methods section, only monocular (consensual) measurements were possible with the BF lenses. However, comparison of measurements made under monocular and binocular conditions with the SVD lens revealed no significant difference between binocular vs monocular measurements, and the equivalent comparison for the SVN lenses revealed only small differences in performance. Specifically, there is no difference between the binocular and monocular responses for the 100 cm target distance, and while the binocular accommodative responses are slightly larger (i.e. less lag), than the monocular responses for the three closest distances, the average differences are < 0.125 D for the 33 and 25 cm target distances, and 0.57 D for the 50 cm target distance. These trends also are in the wrong direction to explain the leads of accommodation observed with the BF lenses.

Discussion

The principal findings of the current study are: (1) that accommodation becomes increasingly inaccurate with increasing demand (reduced target distance), (2) that myopes accommodate less than emmetropes, recording larger accommodative lags as a consequence, and (3) both near addition single vision lenses and bifocal lenses incorporating the same effective add can reduce or eliminate accommodative lags, although there are differences between the effects of these two types of lenses.

Neither the observed interaction between target distance and accommodative lag nor the observed accommodative performance differences between myopes and emmetropes represents a new finding. Nonetheless, that we were able to confirm the findings of others is important in the context of the current study and also in the context of myopia pathogenesis. Specifically, our results indicate that myopes tend to accommodate less than emmetropes for all target distances when wearing distance corrective lenses. Among previous, related studies, different measurement paradigms are encountered, with some studies fixing the target distance and using negative lenses of increasing power to stimulate accommodation and others manipulating the target distance, as in the current study. Nonetheless, most report similar trends, for both children and young adults (Mcbrien and Millodot, 1986; Gwiazda et al., 1993, 1995; Abbott et al., 1998), although the use of negative defocusing lenses appears to exaggerate the difference between myopes and emmetropes (Gwiazda et al., 1995; Abbott et al., 1998).

Because our subjects wearing their distance corrective lenses showed lags of accommodation, we predicted a reduction in their accommodative lags when they wore optical corrections that incorporated near adds, thereby reducing the accommodative demand at all target distances. Our results confirmed our prediction. All subjects showed reductions in their lags of accommodation with SVN contact lenses compared with SVD contact lenses. For the emmetropes and the two farthest target distances, lags of accommodation were replaced by leads of accommodation, and for the same target distances, myopes showed negligible accommodative lags.

There are three earlier studies reporting the effects of near additions on accommodative lags. Findings from one study involving young adults wearing single vision spectacle lenses (Seidemann and Schaeffel, 2003) are consistent with our findings, although this study was confined to ‘near-emmetropic’ subjects. Under monocular viewing conditions, leads of accommodation were observed for their three farthest target distances (1.5, 2 and 3 D accommodative demands) with a + 1.00 D near add, and at all target distances (1.5, 2, 3, 4 and 5 D accommodative demands) with a + 2.00 D add. Another closely related study (Howland et al., 2002) is more difficult to interpret as inter-subject differences in distance refractive errors were not taken into account in the study design. In contrast to the current result, no effect of refractive error was found in a third study, the only previous one to examine refractive error-related differences in the effects of near adds on the accommodative responses (Rosenfield and Carrel, 2001); myopes, emmetropes and hyperopes were tested with + 0.75, + 1.50, + 2.00 and + 2.50 D adds, and one test distance, 40 cm. All adds produced leads of accommodation, with larger adds resulting in larger leads.

Because our choice of near addition for the SVN contact lenses was intended to match the effective add of the BF contact lenses used, then by analogy the accommodative errors measured with the BF and SVN lenses were expected to be similar. However, our analyses indicate that the BF lenses had a much larger effect on the accommodation responses of our subjects than the SVN lenses. Notably, the BF lenses resulted in leads of accommodation at all target distances for both groups, whereas only the emmetropes experienced leads with the SVN lenses, and only for the two farthest targets in this case.

One possible explanation for observed differences in accommodative responses measured with the BF and SVN lenses is that the BF lenses did not provide a + 1.50 D add, as assumed. Our calculations of accommodative errors, which were based on the consensual responses of the fellow SVD lens-wearing eyes, required an assumption to be made about the effective add produced by the BF contact lenses. While we used a value of + 1.50 D, substituting a smaller value (i.e. < + 1.50 D), would bring the calculated errors closer to those calculated for the SVN lenses. Note that our working model also assumes that all subjects experienced true bifocality with the BF contact lenses, with the two optical powers incorporated into the lenses having independent influences on their vision. Other explanations for the differences in accommodative responses seen with the SVN and BF lenses are considered below.

That simultaneous vision contact lenses increase the static ocular depth of focus has been considered as a possible explanation for associated improvements in the reading ability of presbyopes (Chateau and Baude, 1997; Ares et al., 2005), and also may explain the results of the current study. Such increases in the ocular depth of focus provide what is referred to as an extended pseudo-accommodation range, reducing the need for accommodation, just like near addition lenses. For our young adult subjects, BF lens-induced increases in depth of focus are likely to be smaller than for their presbyopic counterparts for which the lenses were designed, because of the typically larger pupils of young adults. Assuming that some accommodation was required at each target distance, albeit reduced in magnitude compared with that required with SVD lenses and greater than that required with SVN lenses, the effective add experienced with the BF lens would have been smaller than that of the SVN lenses, and the effect on the calculated error of accommodation would be an apparent increase in the lead of accommodation with BF lenses compared with SVN lenses, as observed.

While the above explanations can account for differences in the leads of accommodation recorded with the BF and SVN lenses, they do not readily account for apparent differences in the shape of the response curves (Figure 1), and related differences between the emmetropic and myopic groups (Figure 2). For example, with the BF lenses, the largest leads were recorded with an intermediate target distance (50 cm), with the decrease in lead for the larger target distance being particularly prominent for the myopes (Figure 1c). The results for the SVN lenses were more predictable; here, increasing the target distance from 50 to 100 cm resulted in either no change or a further slight increase in lead (Figure 1b). The latter results are also comparable with those of Rosenfield and Carrel (2001), who found increasing leads with increasing near adds, using a fixed testing distance.

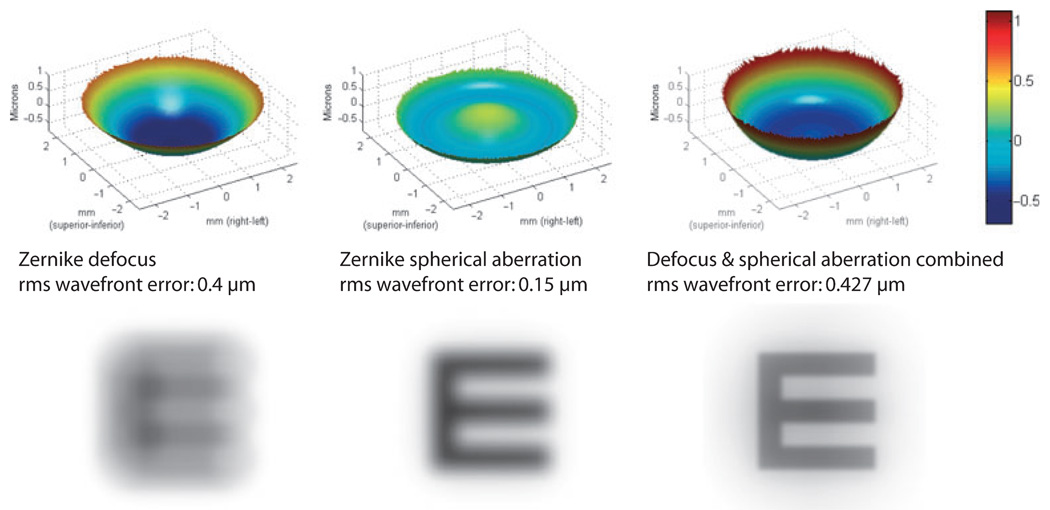

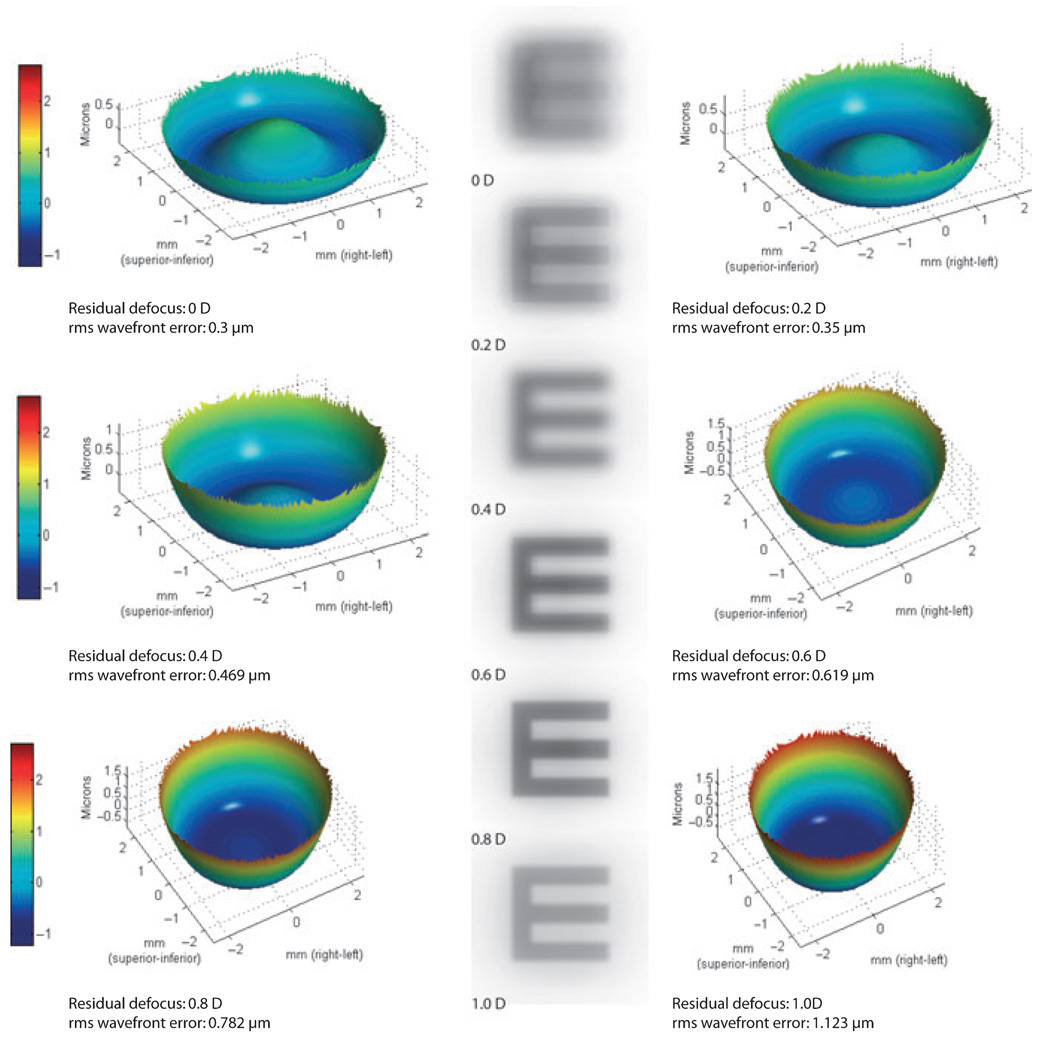

Observed differences between the BF and SVN lens results could reflect differences in the optical designs of the lenses and thus, differences in optical aberrations so introduced. While spherical soft contact lenses are expected to add small amounts of positive spherical aberration (SA), the BF would likely have added much more positive SA as a result of the more positive power in the near ring surrounding the central distance zone. If accommodation optimizes retinal image quality, then these altered ocular aberrations can be expected to alter accommodation responses. This prediction also is consistent with demonstrations from several visual performance studies that specific combinations of positive Zernike SA and positive Zernike defocus (myopic defocus) produce images that appear less subjectively blurred than the same amounts of either defocus or SA alone (Applegate et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2004b; Chen et al., 2005). This interaction between Zernike defocus and SA is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows the wave aberrations over a 5-mm pupil for 0.4 µm root mean square (rms) Zernike defocus and 0.15 µm rms Zernike SA, alone and combined, and simulations of their effects on the retinal image of a 20/50 Snellen E. Note that the individual wave aberration patterns are similar in shape over the central region of the pupil but opposite in sign; thus they interact to produce a flatter wave aberration and consequently, a less blurred retinal image, even though the combined rms (0.427 µm) is larger than either individual term.

Figure 3.

Ocular wave aberrations calculated over a 5-mm pupil for 0.4 µm of Zernike defocus, 0.15 µm of Zernike spherical aberration and the two combined, and simulated retinal images of a 20/50 Snellen E, for each of the three conditions.

Could so-called leads and lags of accommodation simply reflect the amount of defocus required to provide the clearest retinal image in the presence of SA? To test this ‘aberration hypothesis’, we executed two simulations that made use of information about changes in SA with accommodation and estimated BF lens-induced changes in ocular SA.

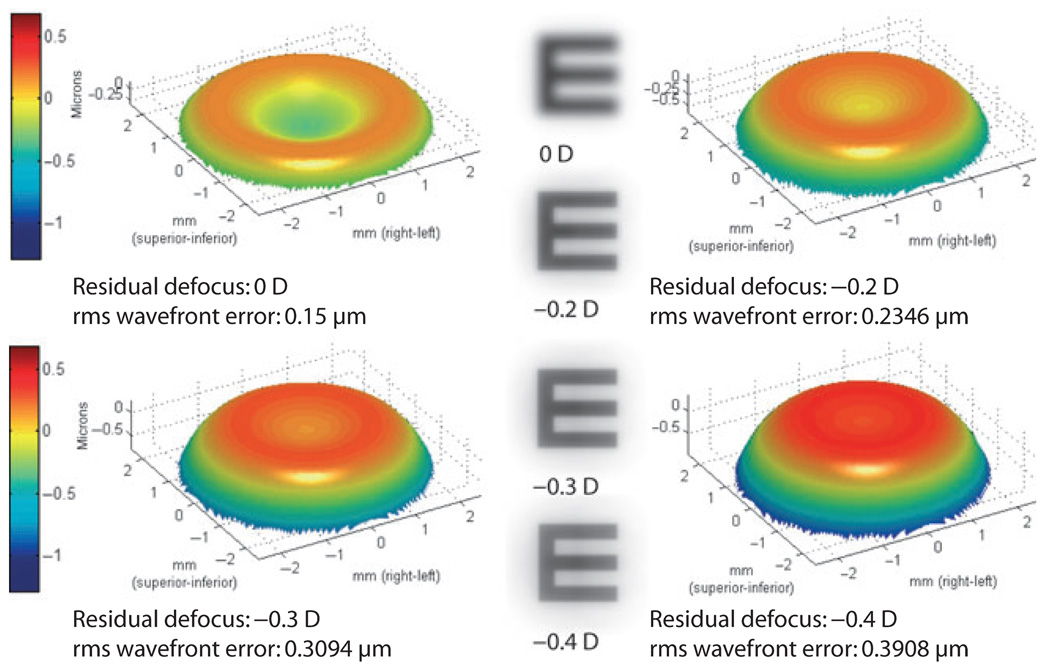

Our first simulation made use of data from an accommodation study of young adults which reported that SA changes from being positive when accommodation is relaxed, and shifts in the negative direction, increasingly so with increasing accommodation (Cheng et al., 2004a). In this study, the average value of Zernike spherical aberration was around −0.15 µm for an accommodative demand of 3–4 D and a 5-mm pupil diameter. For this demand, accommodation typically lags, by approximately 0.5–0.6 D, based on the results from the current study. Thus increasing amounts of negative Zernike defocus, i.e. lags of accommodation, were combined with −0.15 µm of SA in our simulation. Figure 4 shows the calculated ocular wave aberrations over a 5-mm pupil and the resultant retinal images of a 20/50 Snellen E. When considering the interaction between Zernike defocus and SA alone, the clearest image was obtained with a residual defocus (lag) of around −0.3 to −0.4 D. From this, albeit simplistic, simulation it is apparent that a lag of accommodation can serve to reduce retinal image blur in the presence of negative SA, as seen in accommodating eyes. Furthermore, the report of more negative SA in accommodating myopic compared with emmetropic eyes (Collins et al., 1995), should translate into a difference in the optimal lag of accommodation for these two refractive groups, as observed.

Figure 4.

Ocular wave aberrations (µm) calculated over a 5-mm pupil for an accommodating eye with −0.15 µm of Zernike spherical aberration (Cheng et al., 2004a), and a range of negative Zernike defocus. Simulated retinal images of a 20/50 Snellen E shown for the same conditions.

In our second simulation, the SA of the BF contact lens was taken into account. It was not possible to measure the aberrations of the BF contact lens used in the current study because of the discontinuities in optical power inherent in its design. Instead, an estimate of the SA induced by this BF lens was obtained by measuring induced changes in ocular SA for another multifocal contact lens of similar design but without discontinuities. For this simulation, + 0.45 µm of SA was attributed to the BF contact lens and combined with the same amount of ocular SA used in the first simulation, with a net result of + 0.3 µm SA. Figure 5 shows the calculated ocular wave aberrations over a 5-mm pupil for this eye (with + 0.3 µm of SA), and increasing positive Zernike defocus. For each of six defocus conditions tested, the resultant retinal image of a 20/50 Snellen E is also shown. For these conditions, the clearest image was obtained with a residual Zernike defocus of around 0.6–0.8 D, corresponding to a lead of accommodation. Together, these simulations offer further support for accommodative errors (in the latter case, an accommodative lead) being the product of a blur-driven controller; they also predict refractive error-related differences, as observed.

Figure 5.

Ocular wave aberrations (µm) calculated over a 5-mm pupil for an accommodating eye with 0.3 µm of Zernike spherical aberration, to simulate the effect of a bifocal contact lens, and a range of positive Zernike defocus. Simulated retinal images of a 20/50 Snellen E shown for the same conditions.

Which, if any, of the above explanations for the accommodative data collected with the BF lenses, would predict a slowing of myopia progression, as reported in preliminary clinical tests of these lenses (Aller, 2000; Aller and Grisham, 2000; Aller and Wildsoet, 2006, 2007)? The leads of accommodation, such as observed with the BF lenses, could underlie their beneficial effects on myopia progression, given the reports of slowed eye growth with imposed myopic defocus in animal studies (Wildsoet, 1997; Wallman and Winawer, 2004). Animal studies have also established a link between poor retinal image quality and abnormal eye growth. Thus, if the result of interactions between BF lens-induced changes in ocular SA and changes in accommodative errors is a net improvement in retinal image quality, then slowed eye growth would also be predicted. On-going investigations using multifocal lenses in animal studies may provide insight into the mechanism underlying the anti-myopia effect of BF contact lenses.

In conclusion, in the presence of distance corrective lenses, young adult subjects show lags of accommodation, myopes recording larger lags than emmetropes. Near additions can reduce accommodative lags and even convert lags to leads. The BF contact lenses used in the current study appear to induce leads of accommodation for both myopes and emmetropes, smaller for the former group. Further research is needed to understand the exact nature and cause of this effect of the BF lenses, and so guide further refinements of this potential myopia control treatment.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Thomas Aller for sharing his experience with bifocal soft contact lenses as a myopia control treatment that led to this project; also to Austin Roorda for his assistance with the wave aberration and retinal image calculations. This study was supported by NEI grant R01 EY12392-06 and University of California-Berkeley faculty research grant (CFW) and NIH grant T32 EY07043 (JT). Preliminary results for this study were presented at the 2005 ARVO annual meeting.

References

- Abbott ML, Schmid KL, Strang NC. Differences in the accommodation stimulus response curves of adult myopes and emmetropes. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 1998;18:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler D, Millodot M. The possible effect of undercorrection on myopic progression in children. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2006;89:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen PM, O’leary DJ. Accommodation functions: co-dependency and relationship to refractive error. Vision Res. 2006;46:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aller T. Myopia progression with bifocal soft contact lenses – a twin study. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2000;77:S79. [Google Scholar]

- Aller T, Grisham D. Myopia progression control using bifocal contact lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2000;77:S187. [Google Scholar]

- Aller TA, Wildsoet C. Results of a one-year prospective clinical trial (CONTROL) of the use of bifocal soft contact lenses to control myopia progression. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2006;26(S1):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Aller T, Wildsoet CF. Bifocal soft contact lenses as a possible myopia control treatment: a case report involving identical twins. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2007.00230.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate RA, Marsack JD, Ramos R, Sarver EJ. Interaction between aberrations to improve or reduce visual performance. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2003;29:1487–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares J, Flores R, Bara S, Jaroszewicz Z. Presbyopia compensation with a quartic axicon. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2005;82:1071–1078. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000192347.57764.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chateau N, Baude D. Simulated in situ optical performance of bifocal contact lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1997;74:532–539. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199707000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Singer B, Guirao A, Porter J, Williams DR. Image metrics for predicting subjective image quality. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2005;82:358–369. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000162647.80768.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Barnett JK, Vilupuru AS, Marsack JD, Kasthurirangan S, Applegate RA, Roorda A. A population study on changes in wave aberrations with accommodation. J. Vis. 2004a;4:272–280. doi: 10.1167/4.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Bradley A, Thibos LN. Predicting subjective judgment of best focus with objective image quality metrics. J. Vis. 2004b;4:310–321. doi: 10.1167/4.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K, Mohidin N, O’leary DJ. Undercorrection of myopia enhances rather than inhibits myopia progression. Vision Res. 2002;42:2555–2559. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MJ, Wildsoet CF, Atchison DA. Monochromatic aberrations and myopia. Vision Res. 1995;35:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00236-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MH, Li RW, Lam CS, Lew JK, Yu BS. The Hong Kong progressive lens myopia control study: study design and main findings. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:2852–2858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulk GW, Cyert LA, Parker DE. A randomized trial of the effect of single-vision vs. bifocal lenses on myopia progression in children with esophoria. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2000;77:395–401. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss DA, Grosvenor T. Rates of childhood myopia progression with bifocals as a function of nearpoint phoria: consistency of three studies. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1990;67:637–640. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199008000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Bauer J, Held R. Myopic children show insufficient accommodative response to blur. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:690–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda J, Bauer J, Thorn F, Held R. A dynamic relationship between myopia and blur-driven accommodation in school-aged children. Vision Res. 1995;35:1299–1304. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00238-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda J, Hyman L, Hussein M, Everett D, Norton TT, Kurtz D, Leske MC, Manny R, Marsh-Tootle W, Scheim M. A randomized clinical trial of progressive addition lenses versus single vision lenses on the progression of myopia in children. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:1492–1500. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Norton TT, Hussein M, Marsh-Tootle W, Marny R, Wang Y, Everett D. Accommodation and related risk factors associated with myopia progression and their interaction with treatment in COMET children. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:2143–2151. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harb E, Thorn F, Troilo D. Characteristics of accommodative behavior during sustained reading in emmetropes and myopes. Vision Res. 2006;46:2581–2592. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe S, Nakatsuka C, Hamasaki I, Ohtsuki H. Downward deviation of progressive addition lenses in a myopia control trial. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2005;25:310–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland HC, Kelly JE, Shapiro J. Accommodation of young adults using reading spectacles. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43 E-Abstract 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Leung JT, Brown B. Progression of myopia in Hong Kong Chinese schoolchildren is slowed by wearing progressive lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1999;76:346–354. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199906000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Roorda A. Predicting and assessing visual performance with multizone bifocal contact lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2003;80:812–819. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrien NA, Millodot M. The effect of refractive error on the accommodative response gradient. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 1986;6:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Hayes JR, Jones LA, Moeschberger M, Cotter SA, Kleinstein RN, Manny RE, Twelker JD, Zadnik K. Accommodative lag before and after the onset of myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:837–846. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka C, Hasebe S, Nonaka F, Ohtsuki H. Accommodative lag under habitual seeing conditions: comparison between adult myopes and emmetropes. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;47:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(03)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka C, Hasebe S, Nonaka F, Ohtsuki H. Accommodative lag under habitual seeing conditions: comparison between myopic and emmetropic children. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;49:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JR. Monovision slows juvenile myopia progression unilaterally. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1196–1200. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.064212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield M, Carrel MF. Effect of near-vision addition lenses on the accuracy of the accommodative response. Optometry. 2001;72:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield M, Gilmartin B. Myopia and Nearwork. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield M, Desai R, Portello JK. Do progressing myopes show reduced accommodative responses? Optom. Vis. Sci. 2002;79:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200204000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw SM. A synopsis of the prevalence rates and environmental risk factors for myopia. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2003;86:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2003.tb03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor C. The influence of interactions between accommodation and convergence on the lag of accommodation. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 1999;19:134–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.1999.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel D, Gray LS, Heron G. The effect of monocular and binocular viewing on the accommodation response to real targets in emmetropia and myopia. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2005;82:279–285. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000159369.85285.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidemann A, Schaeffel F. An evaluation of the lag of accommodation using photorefraction. Vision Res. 2003;43:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Diaz FA, Strang NC, Winn B. Nearwork induced transient myopia during myopia progression. Curr. Eye Res. 2002;24:289–295. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.24.4.289.8418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman J, Winawer J. Homeostasis of eye growth and the question of myopia. Neuron. 2004;43:447–468. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildsoet CF. Active emmetropization – evidence for its existence and ramifications for clinical practice. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 1997;17:279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]