Abstract

This study considered implications of intergenerational ambivalence for each party's psychological well-being and physical health. Participants included 158 families (N = 474) with a son or daughter aged 22 to 49, their mother and father. Actor-Partner-Interaction Models (APIM) revealed that parents and offspring who self-reported greater ambivalence showed poorer psychological well-being. Partner reports of ambivalence were associated with poorer physical health. When fathers reported greater ambivalence, offspring reported poorer physical health. When grown children reported greater ambivalence, mothers reported poorer physical health. Fathers and offspring who scored lower in neuroticism showed stronger associations between ambivalence and well-being. Findings suggest that partners experience greater ambivalence when the other party's health declines and that personality moderates associations between relationship qualities and well-being.

Scholars recognize the importance of the intergenerational ambivalence model for understanding complex emotional qualities of ties between adults and their parents (Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). This model encompasses both sociological and psychological perspectives. Sociological ambivalence considers incompatible normative expectations in a status or role (e.g., Connidis & McMullin, 2002). Psychological ambivalence occurs at the subjective individual level and involves contradictory cognitions, emotions, and motivations toward the same object (Weigert, 1991). The two perspectives share a focus, however, by considering simultaneous positive and negative experiences in the parent/offspring relationship (Willson, Shuey, Elder, & Wickrama, 2006).

Co-existing positive and negative feelings in a relationship may have detrimental effects on well-being. Uchino and colleagues (2004) argued that ambivalent feelings lead to poor outcomes because these relationships are unpredictable and cause stress. There has been little research examining the implications of ambivalent feelings between parents and their adult offspring, however. This study investigated how parents' and offspring's ambivalent feelings (defined as simultaneous positive and negative sentiments) are associated with each party's well-being.

Ambivalence and Well-being

The premise that ambivalent feelings may be linked to deleterious outcomes is derived from research regarding social networks more broadly. Beginning in the 1970s, epidemiological studies established that positive qualities of social ties enhance physical and mental health; theorists argued that social support and increased motivation to care for oneself may underlie these associations (For a review see: Berkman, & Glass, Brissette, & Seema, 2000). In addition, theorists note that close relationships generate positive emotional states that enhance psychological well-being directly and enhance physiological well-being indirectly (Charles & Mavandadi, 2004).

Similarly, distressful relationships appear to have deleterious effects. Evidence from a longitudinal study of gifted children suggested negative relationships served as a risk factor for mortality (Friedman et al., 2005). Problematic qualities of relationships also were associated with poorer mental health in a large national sample (Newsom, Rook, Nishishiba, Sorkin, & Mahan, 2005). Scholars suggest such effects may be due to negative emotional experiences in important ties (Rook, 2001).

This study focused on intergenerational ambivalence and considered whether the simultaneous experience of positive and negative sentiments detracts from individuals' well-being. Measurement of intergenerational ambivalence warrants comment. Researchers measure relationship ambivalence either indirectly, as a mixture of positive and negative sentiments towards the same person, or directly, as the subjective feeling of being torn (Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). Psychologists have typically assessed ambivalence indirectly, by asking participants to rate contradictory feelings or attitudes towards an object, and then combined the ratings to create an ambivalence score. Many researchers have favored such indirect approaches because individuals may not be aware of their conflicted feelings (Priester & Petty, 1996).

Researchers also have found indirect assessments of ambivalence are associated with direct assessments and with well-being. In a study of social networks among college students, Uchino and colleagues (2004) measured ambivalence in both manners, and found a moderate correlation. Further, they found ambivalent ties measured as a mixture of sentiments were more highly associated with depressive symptoms than were solely negative ties. In addition, people who report having more ambivalent network members demonstrated heightened physiological responses (e.g., elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular reactivity) to laboratory stressors (Holt-Lunstad, Uchino, Smith, Olsen-Cerny, & Nealey-Moore, 2003; Uchino, Holt-Lunstad, Uno, & Flinders, 2001).

Several possible mechanisms may underlie a link between ambivalence and poor well-being. First, the negative feelings in a relationship may detract from the positive effects of support. Second, experiencing a mixture of emotions may be more detrimental than negative emotions alone because individuals may adjust to a generally negative tone and no longer react strongly or they may avoid negative social partners. Finally, although ambivalent ties include desirable positive elements, such ties may be unpredictable and thus, generate stress.

Extending studies linking ambivalence and well-being in the general social network, we focused on ambivalence between adults and their parents. Prior research has documented associations between parent/offspring relationship quality and well-being. Umberson (1992) found offspring who indicated greater support and less strain with parents reported lower psychological distress. Shaw and colleagues (2004) linked adults' memories of emotional support from parents to psychological well-being and physical conditions. Likewise, Silverstein and Bengtson (1991) examined parents' ratings of positive qualities of ties with a randomly selected child; parents who felt closer to this child had a greater likelihood of survival after widowhood.

To the best of our knowledge, only one study has examined intergenerational ambivalence as a predictor of well-being. Lowenstein's (2007) cross-national research found parental ambivalence towards grown children was associated with parental quality of life, albeit only weakly when controlling for personal resources. Lowenstein measured ambivalence as the subjective feeling of being torn, however, rather than as a combination of positive and negative feelings. Yet, research finds combined positive and negative feelings towards network members diminishes physical and emotional well-being. Further, Lowenstein focused only on parents. The first purpose of this study is to examine whether self-reported ambivalence, measured as a mixture of positive and negative feelings, is associated with well-being among parents and adult offspring.

Parent/Offspring Relationships and Well-being

This study also provided a within-family approach to intergenerational ambivalence that goes beyond single respondent data. Several theoretical perspectives emphasize the importance of individuals' beliefs about relationships for their well-being. Dykstra and Mandemakers (2007) referred to the “social construction perspective” of relationships, arguing an individual's subjective view of the tie is what matters for their well-being. Likewise, attachment theory suggests individuals develop internalized working models of their relationships as they move from childhood to adulthood (Bowlby, 1982). But studies that link self reports of relationship quality with well-being do not tell us whether the relationship itself contributes to well-being. This study also examined associations between well-being and the social partner's beliefs.

Interdependence theory suggests that a partner's feelings about the relationship may play a role in the other party's well-being (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Parties who are interdependent react to one another; their well-being is mutually influenced. Interdependence theory has been applied primarily to romantic ties, but it may apply to other relationships as well. In childhood, parents socialize progeny, and children's well-being is vulnerable to parents' feelings about them (Grusec, Goodnow, & Kuczynski, 2000). In adulthood, the role of each party's views of the relationship on the other party's well-being is unclear; parents' and offspring's day-to-day lives are distinct and interdependence in the relationship may be low.

Nonetheless, when a parent or offspring feels mixed emotions, the other party also may experience positive and negative feelings. Two studies of ambivalence that included both generations found parents' and offspring's ambivalent sentiments were associated (Fingerman, Chen, Hay, Cichy, & Lefkowitz, 2006; Willson et al., 2006). Thus, it is important to consider both parents' and offspring's feelings about the relationship because those feelings may be interdependent. Moreover, it is important to consider each party's feelings about the relationship, even when interest lies in self reports of relationship qualities. Kenny and Cook (1999) argued, “Even if one wished to adopt an individualist perspective, it still would be valuable to estimate partner effects to show that they are zero” (p. 435).

Here, we examined how each party's ambivalent feelings are associated with their own and the other party's well-being using the Actor-Partner-Interaction-Method (APIM). APIM is a statistical technique developed to test interdependency in relationships (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). APIM treats the dyad as the unit of analysis, but considers both self-beliefs and partner ratings of the tie. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the parent/adult offspring relationship using APIM.

Social Structures, Predispositions, Ambivalence and Well-being

Relationship ambivalence is unlikely to affect well-being uniformly across individuals. We considered three factors that might explain associations between intergenerational ambivalence and well-being: generation, gender, and neuroticism. The first two variables are features of family and social structure that may shape individuals' experiences in the parent/offspring tie (Rossi & Rossi, 1990). The latter variable pertains to individual predispositions.

Theories of sociological ambivalence suggest that positions within social hierarchies can engender ambivalence (Connidis & McMullin, 2002). The premise of this view of ambivalence is that social positions may be characterized by unclear or contradictory norms, attitudes, and beliefs. In turn, incompatible expectations generate contradictory feelings or ambivalence (Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). Scholars have given particular attention to gender and generational position (i.e., parent vs. offspring) in intergenerational ties (Rossi & Rossi, 1990), and these positions may also be associated with differences in the experience of ambivalence.

With regard to gender, Connidis and McMullin argued that gendered aspects of intergenerational relationships evoke greater ambivalence for women than men because women face competing demands between investment in family, unpaid care, work obligations, and other societal demands. These gender differences may extend into differences in patterns of association between ambivalence and well-being. Structured social relations involving gender lead mothers to be more involved with their offspring and to feel greater responsibility for how children turn out than do fathers (Ryff, et al., 1994). Thus, mothers may be particularly susceptible to qualities of ties to offspring. Offspring also tend to report feeling closer to mothers than fathers (Fingerman, 2001; Rossi & Rossi, 1990). Umberson (1992) found qualities of offspring's relationships with their mothers were more strongly associated with well-being than qualities of relationships with fathers. The role of offspring gender is less clear. Although a study of ambivalence in a rural population revealed differences between sons and daughters (Willson, Shuey, & Elder, 2003), other studies report no difference in ambivalence for sons and daughters (Fingerman, et al., 2006; Pillemer & Suitor, 2002). Therefore, we examined offspring gender without predictions.

With regard to generational position, Peeters, Hooker, and Zvonkovic (2006) applied life course theory to understand how differing historical circumstances and changes in societal values and roles can contribute to intergenerational ambivalence, particularly for parents. Moreover, the relative investments of parents and children in their tie (with parents being more invested) may account for differences in the impact of ambivalence on well-being (Shapiro, 2004). Greater parental investment in the tie may lead to unclear norms for parental roles with grown offspring. Parents may view their offspring's achievements as a validation of their success as parents (Ryff, Lee, Essex, & Schmutte, 1994), but they no longer exert control over grown offspring. Further, individuals tend to experience stronger emotions in situations where they harbor a personal investment (Lazarus, 1991) and the effects of interdependence are most evident in highly valued relationships (Berscheid & Reis, 1998). Thus, both sociological aspects of a changing society and psychological aspects of parental investment in the tie suggest that associations between ambivalence and well-being will be particularly evident for parents.

Psychological ambivalence focuses on the simultaneity of positive and negative emotional experiences. Such consideration of emotional experience suggests that individuals' traits and predispositions may contribute to differences in intergenerational ambivalence. Yet, family science has paid scant attention to how individual's personalities contribute to family ties. Even so, a prior study found parents reported greater ambivalence when they or their child scored higher on neuroticism (Fingerman et al., 2006). Further, theorists argue that individuals who have tendencies towards negativity and emotionality may be particularly sensitive to relationship experiences (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). This sensitivity may extend to intergenerational ambivalence. Indeed, the personality trait neuroticism may moderate associations between ambivalence and well-being.

In sum, this study of intergenerational ambivalence and well-being encompassed a sociological ambivalence framework by considering structured social and family relations that shape the relationship (i.e., generation, gender), and a psychological ambivalence framework by considering the personality trait neuroticism and by assessing ambivalence as a combination of positive and negative feelings. Research questions were: (a) Is intergenerational ambivalence associated with poorer psychological and physical well-being for both parties? (b) Does each party's ambivalence show an interdependent association with their own and the partner's well-being? (c) Do these patterns vary based on structural positions within the relationship (i.e., generation, gender)? and (d) Do individuals' predispositions (i.e., neuroticism) moderate these associations?

Methods

Sample

Data were from the Adult Family Study, involving adults (aged 22 to 49) and their mothers and fathers (aged 40 to 84) residing in the greater Philadelphia area. The initial study involved 213 families including a son or daughter and both their mother and father. These individuals completed telephone interviews about their relationships. This study is limited to a subset of 158 families (N = 474) who also completed face-to-face videotaped interviews and self-report questionnaires. This subset included 82 daughters and 76 sons with both parents, and did not differ from the larger sample on demographic or relationship variables (for details, see: Fingerman et al., 2006).

The study was limited to adult children and parents who resided within 50 miles of each other. Nearly half of adults in the U.S. live within 50 miles of their parents (Booth, Johnson, White, & Edwards, 1991), and 80% of parents reside within 50 miles of one offspring (Lin & Rogerson, 1995). These parents and offspring tend to have more frequent contact than distant offspring (Lawton, Silverstein, & Bengtson, 1994) and thus, may have greater opportunity to affect one another's well-being.

The sample was 68% European American and 32% African American. Although marital status was not a criterion of the study, most parents (89%) and offspring (64%) were married. A majority of parents (54%) and offspring (83%) worked for pay.

Procedure

Most of the sample (85%) was recruited using purchased lists of telephone numbers in the Philadelphia area, including all listed residential phone numbers in the sampled counties and randomly generated numbers with the appropriate area codes. We enhanced recruitment using convenience methods (e.g., advertisements, church bulletins, snowball; 15%) because mixed recruitment approaches may increase minority participation and may generate a sample with more variable relationship quality (Karney, et al, 1995). We stratified by age, gender, and race across recruitment techniques.

Initial phone screening focused on adults aged 22 to 49 who had two living parents. If we reached a household where all adults were over age 50, we screened the household to determine if they had adult children. If they had more than one eligible child, we asked the adult child who had the most recent birthday to participate.

Each participant completed a telephone interview lasting approximately one hour. Offspring then participated in face-to-face interviews separately with their mother and their father. During these sessions, parties completed self-report questionnaires in locations where the other party could not observe them. Offspring responded to questions concerning their mothers and fathers, and each parent responded to questions about the target offspring. Questions pertaining to mother and to father were presented in random order across offspring.

Measures

Individual and relationship characteristics

Participants provided background information (e.g., marital status, work status, family relationships). Ninety percent of parents had more than one son or daughter (M = 2.60 children, SD = 1.81). Participants indicated frequency of contact with the relationship partner on a scale of 1 (never) to 8 (everyday). Parents' and offspring's reports of contact were correlated; on average participants reported speaking by phone at least once a week (M = 6.85, SD = 1.19 mother; M = 6.66, SD = 1.16 father). Most (68%) participants also reported frequent face-to-face contact (once a week).

Participants rated importance of the parent or offspring, using 6 categories: 1 (most important person in your life), 2 (among the 3 most important), 3 (among the 6 most important), 4 (among the 10 most important), 5 (among the 20 most important), and 6 (less important than that; Fingerman, 2001; Fingerman et al., 2006). We reverse coded this item, so higher numbers equal greater importance of the tie. On average participants rated the other party as among the 3 to 6 most important people in their lives (M = 4.34, SD = .93 for mothers, M = 4.48, SD = .79 for fathers, M = 4.50, SD = .93 offspring rating of mother, M = 4.28, SD = .86 offspring rating of father). An ANOVA comparing mothers', fathers', and offspring's reports revealed no significant differences in ratings of importance of the tie.

Neuroticism

We used the 12-item Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck, Eysenck, & Barrett, 1985) to assess neuroticism α = .73. Example yes/no items included, “Are you often fed up?” and “Are your feelings easily hurt?”

Ambivalence

We assessed ambivalence using 4 items from the American Changing Lives Study (Umberson, 1992): “How much does he/she make you feel loved and cared for?”, “How much does he/she understand you?” for positive qualities, α = .69, and “How much does he/she criticize you?”, “How much does he/she make demands on you?”, for negative qualities, α = .69, rated 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). These items present advantages for assessing ambivalence. The items are balanced across the positive and negative dimensions. They refer to behaviors rather than global impressions of the relationship. These items also have been used consistently in studies of intergenerational ambivalence (Fingerman et al., 2006; Willson et al., 2003).

Social psychologists use a variety of formulas to combine two polarized scales and estimate ambivalence (see: Thompson, Zanna, & Griffin, 1995 for a review). It is important to use a formula that distinguishes between intense positive and negative feelings (ambivalence), and indifference or absence of feelings towards an object. As in other studies of intergenerational ambivalence (Fingerman et al., 2006; Willson, et al., 2003, 2006), we applied Griffin's formula to calculate ambivalence scores:

This formula takes into account both similarity and extremity of co-existing positive and negative sentiments. Thompson et al. demonstrated that this formula correlates with other formulas to estimate ambivalence. This formula has been used in research examining intergenerational ambivalence.

Well-being

Because our predictions pertained to global physical and psychological well-being, we created composite measures of these constructs. Consistent with other studies, to create a physical health composite, we averaged standardized (z- scores) self-assessments of health rated 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) and chronic medical conditions (see: Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Janevic, 2003). We recoded this index such that a higher score indicates better health. Due to low frequency of disease among offspring, offspring's physical health score included only self-rated health.

For psychological well-being, we standardized and averaged a one-item assessment of life satisfaction (Sweet, Bumpass, & Call, 1988), rated on a scale of 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied) and the 11 Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scales (CES-D reverse coded; Radloff, 1977), α = .83. Higher scores on this composite represent better psychological well-being. This approach is consistent with the World Health Organization recommendation that positive and negative feelings are key components of psychological functioning (WHO Quality of Life Group, 1998).

Results

Analytic Strategy and Preliminary Analyses

The analytic strategy relied on the actor-partner-interaction model (APIM; Campbell & Kashy, 2002; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). APIM allowed us to consider self-report (i.e., actor data) and partner reported data in the same equation predicting each party's well-being. We estimated APIM using Multilevel Models in SAS PROC Mixed. The composite scales for psychological well-being and physical health served as dependent variables. Independent variables included parents' and offspring's ambivalence scores as self (actor; their own ratings) and other (partner; the other party's) ratings. In other words, for each person's well-being, we considered associations with their own ambivalence scores as well as with their partner's (the parent's or offspring's) ambivalence scores. APIM accounts for correlations or interdependency in these reports.

We also examined whether patterns of association between ambivalence and well-being differed by (a), generation, (b) gender, and (c) neuroticism as follows. With regard to generation, parents and offspring fit criteria for distinguishable dyads in APIM (Kenney et al, 2006). That is, the parent is always the parent and the offspring is always the offspring. An indistinguishable dyad might include two friends or two roommates. Following the advice of Kenny et al. (2006), we included interaction terms between generation and ambivalence to handle distinguishable partners in APIM. Thus, we estimated the models with generation (1 = parent, 0 = offspring), each person's self-reported ambivalence, each partner's reported ambivalence, and the two interaction terms between those reports and generation. We centered ambivalence scores on the grand mean prior to estimating interactions.

With regard to gender, we considered whether associations between ambivalence scores and well-being varied by each party's gender in preliminary analyses by including 3-way interactions for Parent gender X Generation X Ambivalence (with constituent 2 way interactions and main effects). The three way interactions were significant for physical health, but not for psychological well-being. For ease of presentation, we present final models separately for dyads involving mothers and fathers.

We also considered offspring gender in 3 way interactions, but patterns did not differ for sons and daughters. Thus, we simply controlled for offspring gender in final models.

For neuroticism, we estimated models including neuroticism in a 3 way interaction with Neuroticism X Generation X Ambivalence and constituent interaction terms and main effects. We centered ambivalence and neuroticism on their grand means prior to calculating interaction terms.

Finally, in preliminary analyses, we considered family contextual variables. We did not find significant associations between well-being and number of siblings or marital status nor did we find moderating effects of these variables on associations between ambivalence and well-being. We also expected differences in importance of the tie to explain generational differences in associations between ambivalence and well-being. As mentioned previously, we did not find generational differences in ratings of importance of the tie. Therefore, for parsimony in presentation, we did not include family context variables or importance in the final models.

Demographic characteristics, such as ethnicity and education may be associated with salience of the parent/offspring tie, and with well-being (Hill & Sprague, 1999; Hayward, Miles, Crimmins, & Yang, 2000). Thus, we included the following control variables in the models: age, ethnicity, education, frequency of contact, and offspring gender. Table 1 includes descriptive information regarding variables in the models.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Variables Included in Models

| Variables | Offspring | Mother | Father | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report on Mother | Report on Father | |||

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Composite mental healtha | −.22 | -- | .22 | .23 |

| (.90) | -- | (.80) | (.77) | |

| Composite physical healthb | .24 | -- | −.18 | −.06 |

| (.90) | -- | (.96) | (.79) | |

| Independent Variable | ||||

| Ambivalence scorec | 2.39 | 2.19 | 2.23 | 2.39 |

| Control and Moderating Variables | (1.19) | (1.07) | (1.16) | (.98) |

| Age | 34.97 | -- | 61.26 | 63.00 |

| (7.28) | -- | (8.79) | (9.27) | |

| Years of education | 15.05 | -- | 14.03 | 14.13 |

| (1.97) | -- | (2.66) | (2.80) | |

| Frequency of contactd | 6.76 | 6.23 | 6.76 | 6.23 |

| (1.21) | (1.44) | (1.21) | (1.44) | |

| Proportion female | .52 | -- | 1.00 | .00 |

| Proportion African Americane | .32 | -- | .32 | .32 |

| Neuroticismf | 3.75 | -- | 2.70 | 2.23 |

| (2.66) | (2.66) | (2.34) | (2.28) | |

Composite mental health score range −4.32 to 1.23. This score is the mean of 2 standardized items.

Composite physical health score range −3.74 to 1.56. This score is the mean of 2 standardized items.

Ambivalence score possible range .5 to 6.0.

Contact rated 1 (Never) to 8 (Everyday).

Remaining participants are European American

Neuroticism possible range from 0 to 12.00.

Ambivalence and Well-being

Models involving mothers and offspring are found in Table 2. In the model for psychological well-being, a significant main effect for self-report indicates that offspring and mothers who self-reported greater ambivalence reported poorer psychological well-being.

Table 2.

Mixed Model Predicting Mother and Offspring's Well-Being from Mother and Offspring Ambivalence Scores

| Mental Health | Physical Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | B | SEB |

| Intercept | −1.48** | 0.52 | −0.45 | 0.58 |

| Self-reported ambivalence | −0.21** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Partner ambivalence | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Generation | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.39 | 0.22 |

| Self-reported ambivalence X Generation | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Partner ambivalence X Generation | −0.18 | 0.09 | −0.22* | 0.10 |

| Controls | ||||

| Gender | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Ethnicity | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.12 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Contact | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

Note. Parameter estimates are fixed effects.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

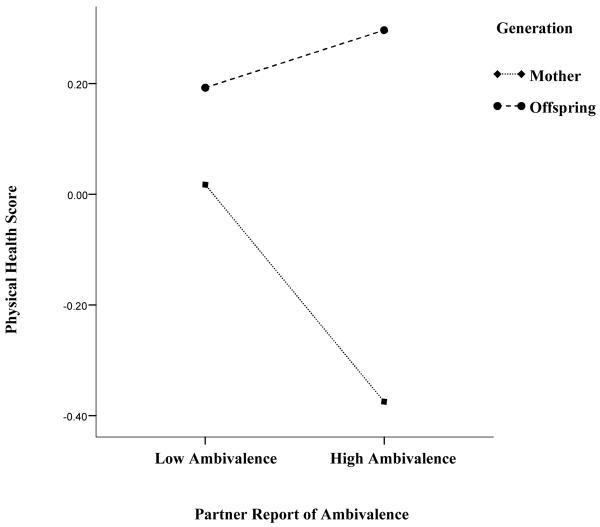

With regard to physical health, however, we found a significant interaction of Generation X Ambivalence in the partners' ratings of the tie. To examine interactions, methodologists advise plotting the figure (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). As can be seen in Figure 1, mothers were in poorer physical health than offspring overall, but when offspring experienced greater ambivalence towards their mothers, their mothers were in poorer health. Mother's ambivalence towards their offspring was not strongly associated with offspring health.

Figure 1.

Mother's and offspring's physical health and interaction between generation (mother and offspring) and partner's reported ambivalence.

Table 3 presents models for fathers and offspring. As was the case for mothers and offspring, self-reported ambivalence was associated with poorer psychological well-being in the father/offspring tie. In other words, when father reported greater ambivalence for the child, he also reported poorer psychological well-being. Likewise, when the child reported greater ambivalence towards the father, he or she reported poorer psychological well-being.

Table 3.

Mixed Model Predicting Father and Offspring's Well-Being from Ambivalence Scores

| Mental Health | Physical Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | B | SEB |

| Intercept | −1.24** | 0.42 | −0.55 | 0.45 |

| Self-reported ambivalence | −0.30*** | 0.06 | −0.13 | 0.07 |

| Partner ambivalence | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| Generation | 0.21 | 0.19 | −0.10 | 0.20 |

| Self-reported ambivalence X Generation | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Partner ambivalence X Generation | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.20* | 0.10 |

| Controls | ||||

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| Ethnicity | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Contact | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Note. Parameter estimates are fixed effects.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

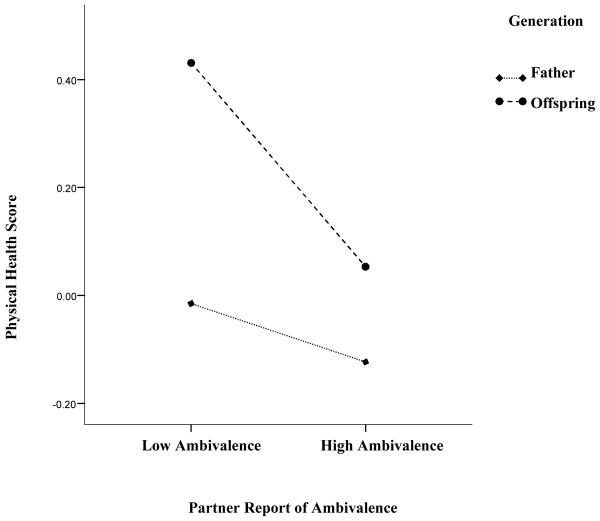

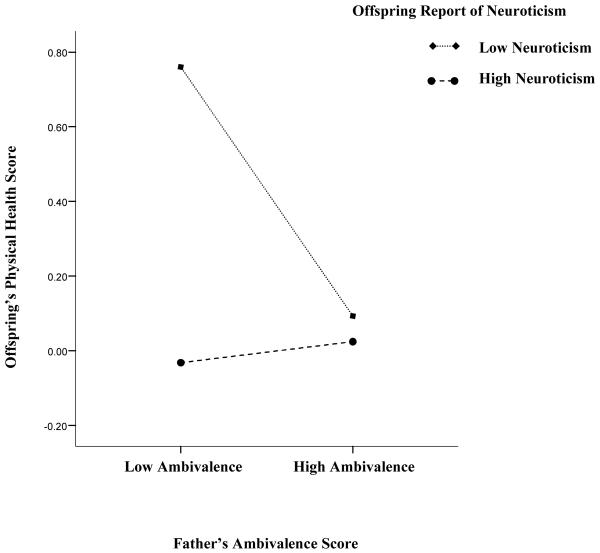

For physical health in the father/offspring tie, there also was a significant interaction for Generation X Partner's ambivalence. Again, offspring were in better physical health than fathers. In this dyad, however, father's ambivalence showed a steeper slope for offspring poorer health than the reverse (Figure 2). When fathers experienced greater ambivalence, offspring experienced poorer health.

Figure 2.

Father's and offspring's physical health and interaction between generation (father and offspring) and partner's reported ambivalence.

In other words, in both dyads, physical health was associated with the partner's ambivalence rather than self-rated ambivalence. In the mother/offspring tie, mother's poorer health was associated with offspring's ratings of the tie. In the father/offspring tie, offspring's poorer physical health was associated with father's rating of the tie.

Ambivalence, Neuroticism, and Well-being

We also estimated a model including neuroticism in a 3 way interaction, Neuroticism X Generation X Ambivalence, the constituent interactions and main effects. These models addressed self-reports, and also addressed how a partner's reported ambivalence (e.g., the father) is associated with the other party's well-being (e.g., the offspring), considering that other party's (e.g., the offspring's) level of neuroticism.

Interactions involving neuroticism were not significant for mother/offspring dyads. Therefore, we do not present these findings.

Table 4 presents findings for father/offspring dyads. For psychological well-being, the three way interaction for Neuroticism X Generation X Self-reported ambivalence was significant. For physical health, partner-reported ambivalence mattered; the three way interaction for Neuroticism X Generation X Partner-reported ambivalence was significant. In both models, significant main effects for neuroticism indicated individuals who scored higher on neuroticism reported poorer psychological and physical well-being.

Table 4.

Mixed Model Predicting Father and Offspring's Well-Being from Ambivalence and Neuroticism

| Mental Health | Physical Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | B | SEB |

| Intercept | −0.64 | 0.46 | −0.35 | 0.53 |

| Self-reported ambivalence | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| Partner ambivalence | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Generation | −0.11 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Neuroticism | −0.18*** | 0.03 | −0.12*** | 0.03 |

| Self-reported ambivalence X Neuroticism X Generation | −0.10** | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Partner ambivalence X Neuroticism X Generation | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.08* | 0.04 |

| Self-reported ambivalence X Neuroticism | 0.09** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Partner ambivalence X Neuroticism | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Self-reported ambivalence X Generation | −0.21* | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| Partner ambivalence X Generation | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.16 | 0.10 |

| Neuroticism X Generation | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Controls | ||||

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Ethnicity | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Contact | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Note. Parameter estimates are fixed effects.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

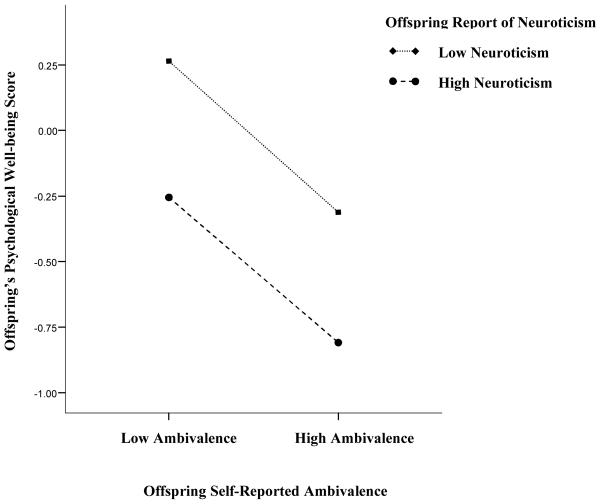

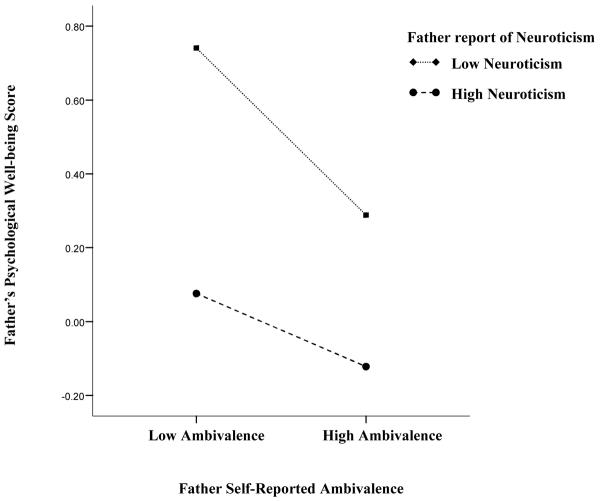

For psychological well-being, we present the three way interaction at the level of the moderator (neuroticism) in figure 3 for offspring and figure 4 for fathers. In figure 3, offspring's psychological well-being was associated with their self-reported ambivalence in a similar way at both high and low levels of neuroticism; self-reported ambivalence was associated with lower psychological well-being, regardless of offspring's neuroticism. For fathers, however, the association between self-reported ambivalence and psychological well-being was stronger when fathers reported lower levels of neuroticism (See figure 4). Fathers who scored low on neuroticism reported particularly high mental health when they experienced little ambivalence towards their offspring, but lessened mental health when they experienced greater ambivalence towards offspring. By contrast, fathers who scored high on neuroticism reported poor mental health in general, and only slightly worse mental health when they also experienced high ambivalence towards their offspring.

Figure 3.

Offspring's psychological well-being and interaction between offspring level of neuroticism and offspring self-reported ambivalence.

Figure 4.

Father's physical health and interaction between father level of neuroticism and father self-reported of ambivalence.

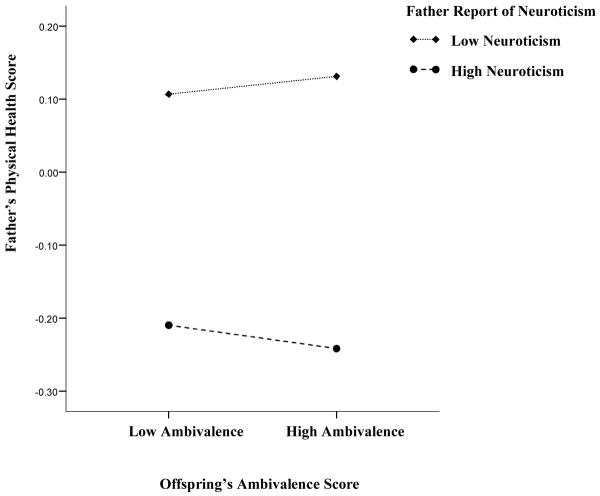

With regard to physical health for offspring and fathers, the significant interaction terms included partner ratings of ambivalence. As can be seen in Figure 5, for offspring's physical health, the association between father's ambivalence and offspring's health was stronger when offspring reported lower neuroticism. When offspring scored low on neuroticism and fathers experienced little ambivalence, offspring reported particularly good physical health. When offspring scored low on neuroticism and fathers experienced high ambivalence, offspring reported poorer physical health. When offspring scored high on neuroticism, paternal ambivalence seemed to have little effect; these offspring generally reported poorer physical health. For father's health, the association between offspring's ratings of ambivalence and father's health did not differ by father's level of neuroticism (see Figure 6). Fathers who scored low on neuroticism reported better physical health than fathers who scored high on neuroticism, regardless of offspring's ambivalence.

Figure 5.

Offspring's physical health and interaction between offspring level of neuroticism and partner's (father's) report of ambivalence.

Figure 6.

Father's physical health and interaction between father level of neuroticism and partner's (offspring's) report of ambivalence.

Discussion

This study extends prior research on intergenerational ties in several respects. First, we considered associations between the simultaneous experience of positive and negative feelings in this tie and well-being, building on prior research that had established associations between relationship quality and well-being (e.g., Shaw, et al., 2004; Umberson, 1992). Second, we examined mothers, fathers, and offspring within the same family, allowing us to consider self reports and partner reports of ambivalence. Third, we contributed to the sociological ambivalence literature by examining how associations between ambivalence and well-being varied as a function of structural position in the family and in society (i.e., generation and parental gender). Finally, we contributed to psychological ambivalence literature by showing individual personality traits (i.e., neuroticism) moderate associations between ambivalence and well-being in some instances.

Ambivalence and Well-being

As expected, for all three parties--mothers, fathers, and offspring-- greater self-reported intergenerational ambivalence was associated with poorer psychological adjustment. Thus, like negative qualities of relationships (Umberson, 1992) mixed emotions between adults and their parents are also associated with more depressive symptoms. Yet, the findings extend knowledge about relationships between adults and their parents by suggesting that mixed emotions also are associated with poorer mental well-being. Research on social networks provides similar findings. Uchino et al (2004) classified relationships as primarily positive, primarily aversive, or emotionally mixed; the emotionally mixed relationships showed stronger associations with poor psychological well-being than aversive ties did. The current study suggests that intergenerational ambivalence also is associated with psychological distress. When adults feel both positive and negative feelings towards a parent or offspring, they may experience lower psychological well-being because they care about the other party's feelings and desire a positive connection. Not knowing what to expect during each encounter (e.g., conflict or a positive interaction) also may engender stress. In addition, ambivalence may involve love for a person who does not reciprocate that affection or who is disappointing in some other respect. Of course, due to the cross sectional nature of this study, it is possible that people with poorer psychological well-being experience greater ambivalence. People who are more depressed tend to elicit negativity in relationships and also may interpret interactions more negatively (Gotlib & Beatty, 1985). A key feature of the present study also involved inclusion of partner reports of ambivalence; self-reports of ambivalence were associated with well-being, controlling for the partner's views of the tie. Future research should attempt to disentangle how such mixed feelings are associated with poorer emotional well-being.

This within-family study also revealed complex associations between partner's intergenerational ambivalence and physical health. Associations between partner ambivalence and well-being were not consistent across mother and father relationships. Mother's physical health was associated with offspring's feelings of ambivalence, whereas offspring's health was associated with father's feelings of ambivalence. The sociological ambivalence framework suggests gender plays a key role in intergenerational ambivalence (Connidis & McMullin, 2002), but that framework primarily pertains to the competing demands regarding women's roles in relationships and other societal expectations. In this study, we did not find a consistent pattern of stronger associations for women than men. Instead, parental gender appeared to play a different role in different relationships.

Interpreting parental gender differences is difficult due to use of snapshot measurement. Scholars have consistently linked qualities of parents' and offspring's relationships to well-being using cross-sectional data, and presumed the relationship qualities predict well-being (e.g., Lowenstein, 2007; Shaw et al, 2004; Umberson, 1992). Nonetheless, researchers interested in intergenerational ambivalence speculate that ambivalence arises when parents' health declines (Fingerman, Hay, Cichy, Kamp-Dush, & Hosterman, 2007; Spitze & Gallant, 2004). Findings in the mother/offspring dyad seem to support this premise regarding ambivalence. When maternal health declines, their illness may evoke ambivalent feelings in their children. Mothers are more involved in caring for children and children expect mothers to serve nurturing roles, even after they are grown. Offspring may help their mothers more when the mothers are in poor health, but they may experience conflicted feelings in doing so (Fingerman, et al, 2007). Their mothers also may appear to be more critical and demanding as a consequence of poor health. Indeed, our prior research revealed that offspring experience ambivalence even when they simply worry about maternal health declines (Hay, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2007). Thus, the partner effect may be in reverse, offspring may experience greater ambivalence as mother's health declines rather than offspring ambivalence generating those declines.

The pattern with regard to fathers is more perplexing. Although offspring were generally in good health, their health showed a negative association with paternal ambivalence. Elsewhere, Umberson (1992) reported that offspring were more sensitive to relationships with their mothers than relationships with their fathers. In this study, offspring's health was worse when fathers were more ambivalent. Unfortunately, we suffer a dearth of research on relationships between adults and fathers. Nonetheless, we might speculate that offspring's poor health generates ambivalence for fathers (rather than the reverse). Fathers in this generation were not highly involved in caring for their children. An adult child's illness may lead to ambivalent feelings for fathers who expect these offspring to be independent and are not accustomed to caring for them.

The findings regarding partner effects also introduce questions about communication of ambivalence in this tie. Observational data reveal adults communicate in distinct ways with mothers and fathers (Cichy, Lefkowitz, & Fingerman, 2008). Yet, partner effects do not necessarily indicate that partners use direct and open communication; people can communicate feelings unconsciously or in subtle ways that are difficult to measure (Kenny & Cook, 1999). Moreover, as mentioned previously, the partner effects regarding fathers may reflect cross-sectional associations between health and ambivalence.

In addition, we note the lack of findings regarding offspring's gender. The paucity of gender differences here may reflect a bias in the sample. Men who agree to participate in studies with their parents may be more similar to women than men in the general population. Nonetheless, other studies in urban areas in recent cohorts have reported no differences in sons' and daughters' relationship with parents (e.g., Fingerman, et al., 2007; Logan & Spitze, 1996) and a national study examining an array of issues (not limited to parents and offspring) also failed to report gender of offspring differences (Shaw et al., 2004). Thus, recent cohorts of sons and daughters may experience fewer differences in relationships with their parents than prior cohorts did.

Finally, the findings present a surprising perspective on how personality traits may moderate family ties. The basic associations between neuroticism and well-being were consistent with expectations; offspring and fathers who scored higher on neuroticism showed poorer well-being. Yet, associations between ambivalence and well-being were more evident among offspring or fathers with lower neuroticism. The direct effect of neuroticism on well-being may be so strong that it is only in the absence of high neuroticism that associations between intergenerational ambivalence and well-being are evident. The effects of a particular emotion-laden family relationship may be greater for individuals who do not typically experience relationships as emotion-laden. Future research on intergenerational ambivalence should further consider within-family associations between personality and ambivalence, with particular attention as to why these associations may appear only in some (e.g., father/offspring) relationships and not in other relationships (e.g., mother/offspring).

In sum, this study extended prior research on relationships between adults and their parents by considering associations between both party's experience of ambivalence and their well-being. Self-reports of ambivalence were associated with emotional well-being, whereas partner's reports were associated with physical health. Further, these patterns differed for mothers and fathers, suggesting offspring have distinct relationships with each parent that warrant further investigation. Likewise, neuroticism played a role in the pattern of associations, but primarily when neuroticism was low. Thus, it is important for scholars to consider individual's structural positions within intergenerational relationships and their personality traits to understand when and why qualities of intergenerational ambivalence may be associated with well-being.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01AG17916 “Problems Between Parents and Offspring in Adulthood” and R01 AG027769, “The Psychology of Intergenerational Transfers” from the National Institute of Aging. We thank Elizabeth Hay, Kelly Cichy, and Laura Miller for assistance with all aspects of the study.

References

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Janevic MR. The effect of social relations with children on the education-health link in men and women aged 40 and over. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:949–960. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seema TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Reis HT. Attraction and close relationships. In: Gilbert D, editor. Handbook of social psychology. 4th edition McGraw Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 193–281. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson D, White L, Edwards J. Marital instability over the life course: Methodology report for the three wave panel study. University of Nebraska Bureau of Sociological Research; Lincoln, NE: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy D. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cichy KE, Lefkowitz ES, Fingerman KL. Demand, withdraw, and dominant behaviors between adults and their parents. 2008 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mavandadi S. Social support and physical health across the life span: Socioemotional influences. In: Lang F, Fingerman KL, editors. Growing together: Personal relationships across the life span. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, McMullin JA. Ambivalence, family ties, and doing sociology. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Mandemakers JJ. Parent-child consensus and parental well-being in mid and late life; the Gerontological Society of America annual meeting; San Francisco, CA. 2007, November. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. A revised version of the Psychoticism Scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL. Aging mothers and their adult daughters: A study in mixed emotions. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Chen PC, Hay EL, Cichy KE, Lefkowitz ES. Ambivalent reactions in the parent and offspring relationship. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2006;61B:152–160. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.p152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Hay EL, Kamp Dush CM, Cichy KE, Hosterman S. Parents' and offspring's perceptions of change and continuity when parents experience the transition to old age. In: Owens TJ, Suitor JJ, editors. Advances in life course research. Elsevier; San Diego, CA: 2007. pp. 275–306. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Schwartz JE, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Martin LR, Wingard DL, Criqui MH. Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of longevity: The aging and death of the “Termites.”. American Psychologist. 1995;50:69–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib I, Beatty ME. Negative responses to depression: The role of attributional style. Cognitive Therapy Research. 1985;9:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ, Kuczynski L. New directions in analyses of parenting contributions to children's acquisition of values. Child Development. 2000;71:205–211. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Miles TP, Crimmins EM, Yang Y. The significance of socioeconomic status in explaining the racial gap in chronic health conditions. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:910–930. [Google Scholar]

- Hay EL, Fingerman KL, Lefkowitz ES. The experience of worry in parent-adult child relationships. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:605–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hill SA, Sprague J. Parenting in black and white families: The interaction of gender with race and class. Gender and Society. 1999;13:480–502. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Olson-Cerny C, Nealey-Moore JB. Social relationships and ambulatory blood pressure: Structural and qualitative predictors of cardiovascular function during everyday social interactions. Health Psychology. 2003;22:388–397. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BK, Davila J, Cohan CL, Sullivan KT, Johnson MD, Bradbury TN. An empirical investigation of sampling strategies in marital research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:909–920. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut J. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Cook W. Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton L, Silverstein M, Bengtson V. Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Goal incongruent (negative) emotions. In: Lazarus RS, editor. Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. pp. 217–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Rogerson PA. Elderly parents and the geographic availability of their adult children. Research on Aging. 1995;17:303–331. [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Spitze GD. Family ties: Enduring relations between parents and their grown children. Temple University Press; Philadelphia, PA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A. Solidarity-conflict and ambivalence: Testing two conceptual frameworks and their impact on quality of life for older family members. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2007;62B:S100–S107. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luescher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: A new approach to the study of parent-child relations in later life. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, Sorkin DH, Mahan RL. Understanding the relative important of positive and negative social exchanges: Examining specific domains and appraisals. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60:P304–P312. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.p304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters CL, Hooker K, Zvonkoyic AM. Older parents' perceptions of ambivalence in relationships with their children. Family Relations. 2006;55:539–551. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Explaining mothers' ambivalence toward their adult children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:602–613. [Google Scholar]

- Priester JR, Petty RE. The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: Relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:431–449. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Emotional health and positive versus negative social exchanges: A daily diary analysis. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Lee YH, Essex MJ, Schmutte PS. My children and me: Midlife evaluations of grown children and of self. Psychology and Aging. 1994;9:195–205. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro A. Revisiting the generation gap: Exploring the relationships of parent/adult- child dyads. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2004;58:127–146. doi: 10.2190/EVFK-7F2X-KQNV-DH58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA, Krause N, Chatters LM, Connell CM, Ingersoll-Dayton B. Emotional support from parents early in life, aging, and health. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:4–12. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Bengtson VL. Do close parent-child relations reduce the mortality risk of older parents? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:382–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitze G, Gallant MP. The bitter with the sweet: Older adults' strategies for handling ambivalence with their adult children. Research on Aging. 2004;26:387–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet J, Bumpass L, Call V. The design and content of the National Survey of Families and Households. University of Wisconsin; Madison: 1988. Working Paper NSFH-1. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MM, Zanna MP, Griffin DW. Let's not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In: Petty RE, Krosnick JA, editors. Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TW, Bloor L. Heterogeneity in social networks: A comparison of different models linking relationships to psychological outcomes. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychological. 2004;23:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Holt-Lunstad UD, Flinders JB. Heterogeneity in the social networks of young and older adults: Prediction of mental health and cardiovascular reactivity during acute stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:361–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1010634902498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:664–674. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert AJ. Mixed emotions: Certain steps toward understanding ambivalence. State University of New York Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH. Ambivalence in the relationship of adult children to aging parents and in-laws. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2003;65:1055–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH, Wickrama K. Ambivalence in mother-adult child relations: A dyadic analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2006;69:235–252. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Quality of Life Group Quality of life assessment development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;46:1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]