Abstract

Objective

Environmental and cultural factors, as well as a genetic variant of the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (the ALDH2*2 allele) have been identified as correlates of alcohol use among Asian Americans. However, concurrent examination of these variables has been rare. The present study assessed parental alcohol use, acculturation and ALDH2 gene status in relation to lifetime, current and heavy episodic drinking among Chinese and Korean American undergraduates.

Method

Participants (N = 428, 51% women; 52% Chinese American, age 18–19 years) were first-year college students in a longitudinal study of substance use initiation and progression. Data were collected via structured interview and self-report, and participants provided a blood sample for genotyping at the ALDH2 locus.

Results

Gender, parental alcohol use and acculturation significantly predicted drinking behavior. However, none of the hypothesized moderating relationships were significant. In contrast with previous studies, ALDH2 gene status was not associated with alcohol use.

Conclusions

Results indicate that although the variables examined influence alcohol use, moderating effects were not observed in the present sample of Asian American college students. Findings further suggest that the established association ALDH2 status and drinking behavior in Asians may not be evident in late adolescence. It is possible that ALDH2 status is associated with alcohol consumption only following initiation and increased drinking experience.

Asian Americans Comprise the fastest-growing ethnic minority population in the United States (Varma and Siris, 1996); accordingly, understanding the etiology of substance use in this group is increasingly important. It has been noted that substance use prevention initiatives should attend to culture-specific factors influencing use among emergent ethnic minority populations (Castro and Alarcon, 2002; Unger et al., 2002). To accomplish this goal it is necessary to first identify such factors, as well as to determine how culture-specific variables give rise to cross-ethnic differences in substance use. As adolescence is often marked by initiation and escalation of substance use (O’Malley et al., 1998), studies of Asian American youth are important to the identification of etiologic factors specific to alcohol and other drug use in this population.

Limited research exists concerning risk and protective factors for alcohol and other substance use among Asian American adolescents (Harachi et al., 2001). Moreover, information is sparse for rates and correlates of substance use across specific Asian American subpopulations (Harachi et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2004; Zane and Kim, 1994). Although national and state epidemiological surveys often report that Asian Americans exhibit low rates of alcohol use, studies examining adult populations in Asia and the United States {Chi et al., 1989); Kitano and Chi, 1989) and adolescents in the United States (Wong et al., 2004) reveal substantial variation in alcohol use across Asian subgroups. Failure to compare ethnic subgroups in studies of substance use not only precludes examination of intragroup heterogeneity but also may serve to underestimate actual prevalence of substance use among Asian Americans (Wong et al., 2004). Studies of Asian American youth that attend to potential variability in correlates of drinking across ethnic subgroups would therefore broaden existing knowledge of alcohol use etiology in this population.

Research suggests that adolescents of Asian and other ethnic backgrounds share some common correlates of alcohol use (Harachi et al., 2001), including psychosocial factors such as perceived adult and peer alcohol use (Chi et al., 1989; Newcomb and Bentler, 1986). However factors specific to Asian populations—for example, genetic variations in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes (Sun et al., 2002; Wall et al., 2001)—have also been implicated. Observed relationships between acculturation and drinking behavior among Asian Americans (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004; Sue et al., 1979) further suggest the importance of examining cultural variables as they pertain to alcohol use etiology in this group. Finally, although the aforementioned factors may combine or interact to influence drinking in Asian groups (Akutsu et al., 1989; Au and Donaldson, 2000; Sue and Nakamura, 1984), such relationships have seldom been examined.

Parental alcohol use has been associated with adolescent drinking in the general population (Ary et al., 1993; Barnes et al., 1994; White et al., 2000), Consistent with Social Cognitive Theory-based formulations of alcohol use etiology (Abrams and Niaura, 1987), this relationship may be attributable in part to parental modeling of substance use behavior. Low rates of parental alcohol use may therefore Contribute to decreased drinking rates among Asian youth, who report reduced exposure to adult alcohol use relative to other adolescents (Au and Donaldson, 2000; Keefe and Newcomb, 1996; Newcomb and Bentler, 1986), Additionally, evidence suggests that concordance between perceived adult substance use and self-use is higher among Asian adolescents than among adolescents of other ethnicities (de Moor et al., 1989; Newcomb and Bentler, 1986). Thus, relative to other youth, parental drinking might serve as an important influence on alcohol use among Asian adolescents, who may experience reduced exposure to parental alcohol use, may exhibit greater concordance between parent-use and self-use, or both.

Cultural factors also are purported to play an important role in the alcohol use behavior of Asian populations (Zane and Sasao, 1992). Notably, collectivistic values such as interdependence, moderation and interpersonal responsibility are thought to contribute to the low prevalence of alcohol use in this group (Au and Donaldson, 2000; Chi et al., 1989). Studies of acculturation and drinking in Asian Americans lend broad support to this position, demonstrating a relationship between assimilation into the majority culture and increased consumption of alcohol (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004; Sue et al., 1979). Although these data reinforce the notion that the assimilative process generally confers increased substance use risk among Asian Americans, the mechanisms by which acculturation leads to changes in substance use behavior are currently unclear (Beauvais, 1998; Singelis, 1994).

Two recent reports suggest that the influence of acculturation on drinking behavior among Asian American youth may be contingent on psychosocial factors. In a nationally representative sample of Asian American adolescents, Hahm et al., (2003) found that parental attachment moderated the influence of acculturation on past-year alcohol use and that effects of acculturation on past-year heavy drinking were mediated by peer alcohol and tobacco use (Hahm et al., 2004). These studies highlight the influence of psychosocial factors on acculturation-alcohol use relationships. An additional possibility is that these relationships could vary as a function of ethnic and gender subgroup. For example, whereas acculturation has been positively correlated with alcohol consumption among Asian Americans generally (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004; Sue et al., 1979), males in Korea demonstrate higher rates of alcohol abuse and dependence than males in the United States (Helzer et al., 1990). Thus, acculturation might be inversely correlated with alcohol use in this subpopulation. Examination of cultural and psychosocial influences on drinking with attention to potential ethnic and gender subgroup variation in these relationships would help to further elucidate the relationship of acculturation with alcohol use in Asian American populations.

Environmental and cultural correlates of alcohol use in Asian groups must also be considered in light of established genetic influences on drinking behavior. Up to one half of individuals of northeastern Asian descent (Chinese, Japanese and Koreans) carry a variant of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) gene—the ALDH2*2 allele—that leads to impaired metabolism of acetaldehyde (Goedde et al., 1992). Compared with individuals without an ALDH2*2 allele, those possessing one or two copies demonstrate stronger physiological reactions to alcohol ingestion (Peng et al., 1999; Wall et al., 1992, 1994, 1996). Accordingly, presence of an ALDH2*2 allele has been associated with decreased rates of alcohol use (Sun et al., 2002; Wall et al., 2001), heavy episodic (binge) drinking (Luczak et al., 2001; Takeshita and Morimoto, 1999; Wall et al., 2001) and alcohol dependence (Chen et al., 1999; Luczak et al., 2004; Thomasson et al., 1991).

It is possible that biological factors such as ALDH2 genotype act in concert with psychosocial or cultural factors to influence alcohol consumption among Asians (Au and Donaldson, 2000; Johnson and Nagoshi, 1990; McCarthy et al., 2001). A recent report (Luczak et al., 2001) identified an additive effect of ALDH2 gene status and ethnicity (Chinese vs Korean) on heavy episodic (binge) drinking, highlighting the aggregate influence of biological and ethnic factors on alcohol consumption in Asian groups. Familial studies of Asian populations in Hawaii (Johnson et al., 1987, 1990) have indicated that cultural factors are more strongly associated with drinking than self-reported alcohol-induced flushing, suggesting that genetic influences on alcohol use in these groups are negligible relative to sociocultural determinants (Johnson and Nagoshi, 1990). However, these studies assessed neither ALDH2 genotype nor relationships between physiological response to alcohol and heavy drinking behavior, which has been linked to ALDH2 status in several reports (Luczak et al., 2001; Takeshita and Morimoto, 1999; Wall et al., 2001). Studies examining both ALDH2 status and cultural variables (i.e., acculturation) in relation to heavy drinking could help to clarify the relative influence of physiological and sociocultural determinants of alcohol use. Finally, ALDH2 status may manifest indirect effects on adolescent drinking via psychosocial variables. For example, individuals possessing an ALDH2*2 allele may experience reduced exposure to parental alcohol use because at least one biological parent must carry the same allele. Given the variety of potential mechanisms by which ALDH2 status may interact with psychosocial and cultural factors to influence alcohol use, simultaneous examination of these variables would be useful.

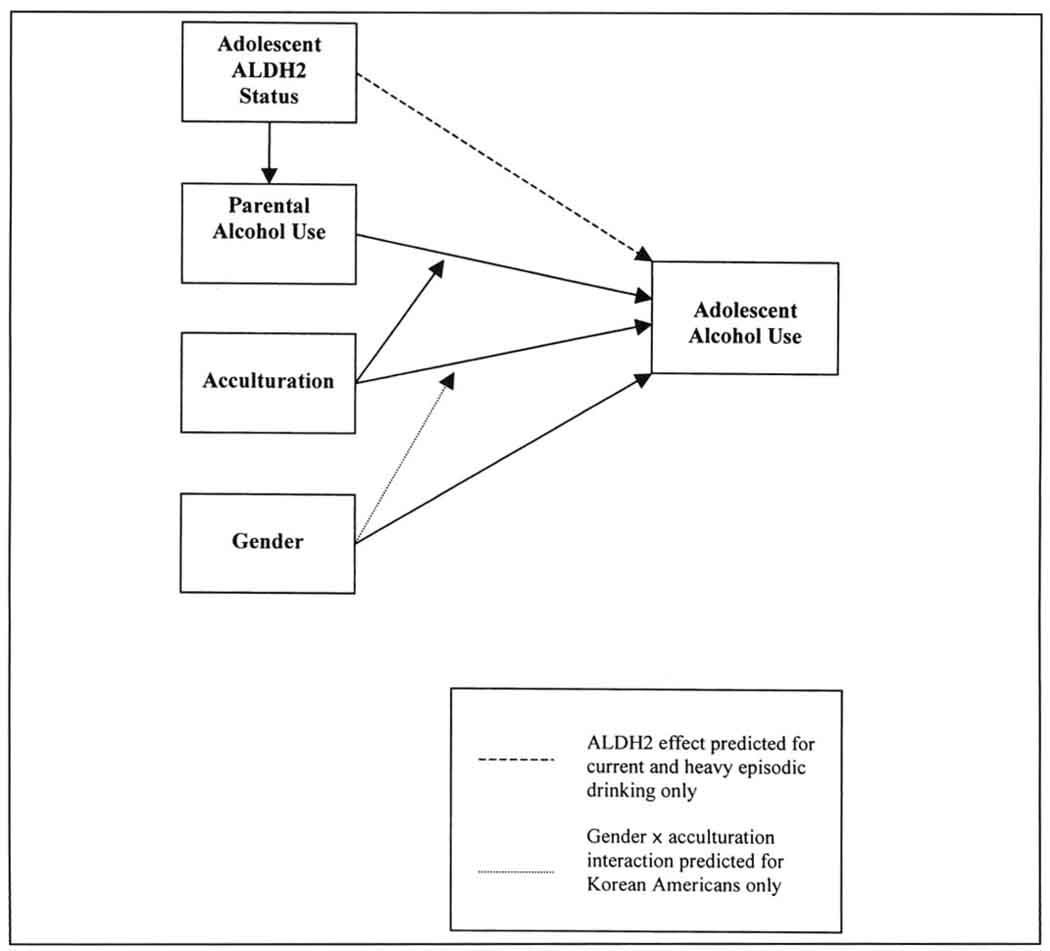

Although several authors have proposed that psychosocial, cultural and genetic factors exert cumulative or interactive effects on drinking behavior among Asian Americans (Akutsu et al., 1989; Au and Donaldson, 2000; Sue and Nakamura, 1984), few studies have examined these variables in concert. Recent support for interactive and mediating relationships among acculturation and psychosocial variables (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004) and the aggregate influence of genetic factors and ethnicity (Luczak et al., 2001) on drinking in Asian Americans underscore the importance of joint examination of these factors. An integrative model (Figure 1) incorporating psychosocial, cultural and genetic factors served as the basis for the current study. Parental alcohol use, acculturation and ALDH2 status were evaluated in relation to lifetime and current alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking among Chinese American and Korean American undergraduates. Gender was also evaluated as a predictor of alcohol use. To examine the possibility of differential influence of these variables on drinking across Chinese American and Korean American subgroups, ethnicity was explored as a moderator in each of the relationships examined.

Figure 1.

Proposed Model of alcohol use among Asian American adolescents

Consistent with previous studies, we expected perceived parental alcohol use and higher levels of acculturation to correspond with higher rates of alcohol use, and expected presence of an ALDH2*2 allele would relate to reduced current and heavy episodic drinking. Because males in Korea demonstrate higher rates of alcohol abuse and dependence than males in the United States (Helzer el al., 1990), we anticipated that gender would moderate the relationship between acculturation and alcohol use among Korean Americans. We further hypothesized an indirect effect of ALDH2 gene status on adolescent alcohol use via parental alcohol use, as participants with an ALDH2*2 allele also have at least one biological parent with the same allele.

Finally, we predicted that acculturation would moderate the influence of parental alcohol use on adolescent drinking. This prediction derives from the suggestion that assimilation to Western culture mitigates protective effects of Asian sociocultural factors on substance use, which may include increased familial attachment and reduced exposure to substance use models (Au and Donaldson, 2000). As increased acculturation in adolescence could serve to mitigate parental attachment (Rumbaut, 1999), which in turn has been found to moderate replication of parental substance use behavior (Foshee and Bauman, 1992 we predicted that increased acculturation would lead to decreased concordance between parental and adolescent alcohol use.

Method

Participants

The present sample includes 428 of 434 Asian American undergraduate participants (51% women; age 18–19 years) in a longitudinal study of risk and protective factors for substance use in this population. Students at a public university in southern California who reported being of entirely Chinese (52%) or Korean (48%) descent were recruited for participation during their freshman year in college. (This sample consists of two cohorts [n’s 205 and 229, respectively] recruited in successive years.) Data were gathered during intake assessments conducted during the fall and winter quarters subsequent to college entry. Six participants (1%) were excluded from the present study owing to missing data on acculturation or on parental alcohol use variables. Self-reports of participants’ generational status showed that the sample was 39.5% first-generation, 57.0% second-generation, 1.3% third-generation, 0.5% fourth-generation and 0.5% fifth-generation American. Five participants (1.2%) were unsure of their generational status. Reported generational status did not differ by ethnicity.

Procedure

Students were recruited via campus flyers and newspapers; advertisements did not disclose that the study concerned substance use behavior. Telephone screening determined eligibility; inclusion criteria consisted of being (1) a first-year college student, (2) entirely of Chinese or Korean descent and (3) 18 or 19 years of age. Following written informed consent, qualifying participants completed a structured interview and self-report questionnaires administered by a trained research assistant. Participants provided a fingertip-puncture blood sample for subsequent ALDH2 genotype analysis.

Measures

Acculturation

Level of acculturation was assessed with the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation (SL-ASIA) scale (Suinn et al., 1987). The SL-ASIA scale is a multidimensional measure developed to evaluate acculturative status among individuals of Asian heritage. The SL-ASIA scale consists of 21 Likert-scale items ranging from 1 to 5. Items are averaged to yield a final acculturation score from 1.00 (low acculturation/high Asian identification) to 5.00 (high acculturation high Western identification). This measure is found to have adequate reliability (Suinn, 1987; Suinn et al., 1992) and good concurrent validity (Suinn et al., 1992). The full SL-ASIA scale demonstrated good internal reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .87). Skewness of the distribution of SL-ASIA scores in the present sample was acceptable (s = .099, SE = .118).

Alcohol use

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) method (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) was used to assess participants’ recent (past 90 days) alcohol-use quantity and frequency. Alcohol-use quantity was recorded for each day on which drinking was reported. Data from the TLFB computations were tabulated to reflect average quantity and frequency of use for the past 30 days as well as number of heavy drinking episodes during the 2 weeks preceding the interview. Heavy drinking episodes were defined as consumption in the past 2 weeks of four or more drinks on an occasion for women and five or more drinks on an occasion for men to allow for comparison with previous studies of this population (e.g., Luczak et al., 2003). The TLFB method has been shown to have good reliability and validity with college students (Sobell et al., 1989). Lifetime alcohol use was assessed using the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR; Brown et al., 1998). The CDDR assesses age at first use and lifetime frequency estimates of use separately for beer, wine and distilled spirits. The CDDR has good reliability for assessing substance use behaviors among adolescents and young adults (Brown et al., 1998). Data from the CDDR were used to determine lifetime drinking status (yes/no).

Parental alcohol use

Parental alcohol use was assessed separately for mother and father using a single item (Does your mother [father] drink alcohol now or did s/he ever drink?). Based on participant responses, each participant was classified as either having drinking parents (one or both parents ever drank alcohol), or nondrinking parents (both parents never drank).

ALDH2 genotyping

Blood samples underwent DNA analysis at the Alcohol Research Center at Indiana University. ALDH2 status was ascertained using polymerase chain reaction of DNA and allele-specific oligonucleotide probes (Crabb et al., 1989). Participants were identified as ALDH2*1/*1 homozygous, ALDH2*1/*2 heterozygous, or ALDH2*2/*2 homozygous. For purposes of the present study, the latter two categories were combined, resulting in two groups: those possessing or not possessing an ALDH2*2 allele.

Analytic strategy

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square analysis were employed for preliminary group comparisons as appropriate. The distributional properties of all noncategorical variables were assessed to determine whether they met the statistical assumptions for the analyses. Distributional properties of the dependent variables did not meet statistical assumptions for ANOVA, being both significantly kurtotic (K = 74.34, z = 309.75; K = 68.20, z = 284.17; K = 17.74, z = 73.92; SE = .24) and significantly positively skewed (s = 7.42, z = 61.83; s = 7.49, z = 62.41; s = 3.73, z = 31.08; SE = .12) for total number of lifetime drinks, past 30-day quantity-frequency, and total number of heavy drinking episodes in the past 2 weeks, respectively. Transformations did not significantly normalize the distributions. Thus, the alcohol use variables were dichotomized into lifetime use (yes/no), used in past 30 days (yes/no) and any heavy drinking episodes in the past 2 weeks (yes/no).

Univariate logistic regressions were conducted within the full sample to examine the relationship between each independent variable and lifetime alcohol use, current (past 30-day) alcohol use and past 2-week heavy episodic alcohol use. Family-wise corrections {Dar et al., 1994) were applied for multiple analyses, in which all univariate analyses with the three dependent variables involving a specific independent variable (e.g., parental alcohol use) or a moderating effect (e.g., parental use by acculturation interaction) were treated as a family, such that a corrected p value of .017 was used to reflect an uncorrected p < .05. Power analyses were calculated according to procedures described by Cohen (1992). With a sample size of N = 429, power = .80 and alpha = .05, an actual proportion of .593 versus a null proportion value .50 could be detected. Therefore the decision was made to examine univariate relationships within the full sample. Relative contributions of independent to dependent variables were examined in multivariate logistic regressions. Each independent variable found to have a significant relationship to a dependent variable in univariate analyses was included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Hypothesized and exploratory moderating relationships were tested based on guidelines proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). Combinations of two independent variables and their interaction were included in each analysis. Based on procedures recommended by Aiken and West (1991), level of acculturation, gender, ethnicity and parental alcohol use were centered prior to creation of the interaction terms.

Results

Primary comparisons of ethnic groups

First, ethnic differences were examined for demographics, all alcohol use variables, ALDH2 status, parental alcohol use and acculturation. Results are reported in Table 1. Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Luczak et al., 2004), significantly more Chinese Americans (49%) than Korean Americans (33%) carried at least one ALDH2*2 allele (χ2 = 11.21, 1 df, p=.001). Chinese Americans were marginally more likely than Korean Americans to report that neither parent had ever used alcohol (23.3% vs 16.1% respectively; χ2 = 3.50, 1 df, p = .061). Additionally, Chinese Americans were significantly more acculturated (mean [SD] = 3.00 [0.45]) than Korean Americans in this sample (mean = 2.89 [0.45]; F = 5.92, 1/426 df, p = .015). There were no gender differences or gender by ethnicity differences in level of acculturation.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Chinese Americans and Korean Americans on demographics, alcohol use, ALDH2 status, parental alcohol use and acculturation

| Characteristics | Chinese Americans (n = 223) | Korean Americans (n = 205) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 18.12 (0.32) | 18.18 (0.39) |

| Gender, % female | 50.7 | 52.7 |

| Alcohol-use variables | ||

| Lifetime alcohol use, % | 80.3 | 79.0 |

| Used alcohol in past 30 days, % | 48.4 | 48.8 |

| Heavy drinking episode in past 2 weeks, % | 17.5 | 20.6 |

| ALDH2 status, %* | ||

| ALDH2*1/*1 | 50.7 | 66.7 |

| ALDH2*1/*2 | 42.6 | 31.9 |

| ALDH2*2/*2 | 6.7 | 1.5 |

| Parental alcohol use, % | ||

| Neither parent ever used alcohol§ | 23.3 | 16.1 |

| At least one parent used alcohol in lifetime | 76.7 | 83.9 |

| Acculturation | ||

| SL-ASIA score, mean (SD)* | 3.00 (.46) | 2.89 (.45) |

| Years lived in united states, mean (SD) | 14.70 (4.74) | 14.58 (4.77) |

Note: SL-ASIA = Suinn-Lew Asian Self-identity Acculturation Scale.

p <.10

p <.05.

Although there were no ethnic differences across alcohol use variables, the gender by ethnicity difference in lifetime alcohol consumption approached uncorrected significance values, with Korean American women exhibiting the lowest (73.1%) and Korean American men the highest (85.6%) rates of lifetime alcohol use (χ2 = 7.42, 3 df, p .06). As shown in Table 2, no gender by ethnicity differences were found for current use or for heavy episodic use.

TABLE 2.

Proportions of lifetime and current alcohol use across four gender/ethnic groups

| Alcohol-use variables | Chinese men (n = 111) | Chinese Women (n = 112) | Korean men (n = 97) | Korean women (n = 108) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever used alcohol in lifetime, %§ | 84.5 | 76.1 | 85.6 | 73.1 |

| Used alcohol in past 30 days, % | 52.7 | 44.2 | 56.7 | 41.7 |

| Heavy drinking episode in past 2 weeks, % | 17.3 | 17.7 | 24.7 | 16.8 |

p <.10

ALDH2 status and heavy episodic drinking

The relationship between ALDH2 status and heavy episodic drinking was examined across ethnicity as well as across ethnicity by gender groups. Similar rates of heavy episodic drinking were found by ALDH2 status for both Korean Americans and Chinese Americans. Within the Korean American group, 20.7% of participants without an ALDH2*2 allele (ALDH2*1/*1) and 19.1% of those with an ALDH2*2 allele (ALDH2*1/*2 or ALDH2*2/*2) engaged in heavy episodic drinking (χ2 = .07, 1 df, p = .79). Among Chinese Americans, 16.8% of participants without an ALDH2*2 allele and 18.2% of those with an ALDH2*2 allele engaged in heavy episodic drinking (χ2 07, 1 df, p = .79). Consistent with the findings for ethnic groups, similar rates of heavy episodic use were identified across ALDH2 status for the four ethnicity by gender groups.

Univariate analyses

Phi coefficients and point biserial correlations among the independent variables were examined for the full sample; correlation coefficients ranged from −.09 to .16, No relationship was found between ALDH2 status and parental alcohol use (Φ = −.08).

Phi coefficients were examined among the three dependent variables to determine if multicollinearity, and hence redundancy of analyses, might be an issue. The degree of association between lifetime and current alcohol use was Φ = .49, between lifetime and heavy episodic alcohol use was Φ = .25 and between current alcohol use and heavy episodic alcohol use was Φ = .43, indicating no significant multicollinearity.

Univariate logistic regressions were conducted to assess the relationship of gender, parental alcohol use and level of acculturation to lifetime alcohol use, current alcohol use and past 2-week heavy episodic drinking. In addition, ALDH2 status was examined in relation to current alcohol use and heavy episodic use. To minimize the number of comparisons conducted, univariate relationships not hypothesized differ across ethnicity were analyzed for the full sample. Ethnicity was not considered as a covariate in the univariate analyses because no ethnic differences were found on any of the alcohol use variables. Results of the univariate logistic regressions are presented in Table 3 to Table 5.

TABLE 3.

Step Chi-squares, odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) for lifetime alcohol use

| Independent variable | Step χ2 | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 7.18 | .007a | 0.52 | 0.32–0.85 |

| Parental alcohol use | 22.48 | .0001a | 3.65 | 2.16–6.16 |

| Acculturation | 0.01 | .91 | 1.03 | 0.61–1.73 |

Significance levels indicated at adjusted p < .017.

TABLE 5.

Step chi-squares, odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) for heavy episodic alcohol use

| Independent variable | Step χ2 | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.86 | .36 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.29 |

| ALDH2 | 0.01 | .91 | 0.97 | 0.59–1.60 |

| Parental alcohol use | 0.12 | .73 | 1.12 | 0.60–2.07 |

| Acculturation | 5.91 | .015a | 1.94 | 1.13–3.32 |

Significance levels indicated at adjusted p < .017.

Gender and parental drinking were significantly related to lifetime alcohol use. Women were about half as likely as men to have ever used alcohol (step χ2 = 7.18, 1 df, p = .007, corrected p = .017, OR = 0.52, CI = 0.32–0.85). Those with at least one parent who had used alcohol were approximately three and one half times more likely to have ever used alcohol than those with nondrinking parents (step χ2 = 22.48, 1 df, p = .0001, corrected p = .017, OR = 3.65, CI = 2.16–6.16).

Gender, parental alcohol use and level of acculturation significantly related to current alcohol use. Similar to life-time alcohol use, women were about half as likely as men to have used alcohol in the past 30 days (step χ2 = 5.77, 1 df, p = .016, corrected p = .017, OR = 0.63 CI = 0.43–0.92). Having at least one parent that had ever used alcohol was related to an approximately two times greater likelihood of current alcohol use (step χ2 = 7.62, 1 df, P = .006, corrected p = .017, OR = 1.98, CI = 1.21–3.24). Level of acculturation was significantly related to past 30-day alcohol use with a one-unit increase in level of acculturation associated with about one and a half times greater likelihood of using alcohol in the past 30 days (step χ2 = 6.12, 1 df, p = .013, corrected p = .017, OR = 1.70, CI = 1.11–2.60).

Of the variables examined, only level of acculturation was associated with past 2-week heavy episodic use. A one-unit increase in level of acculturation was related to an approximately two times greater likelihood of heavy episodic alcohol use (step χ2 = 5.91 1 df, p = .015, corrected p = .017, OR = 1.94, CI = 1.13–3.32).

Post hoc power analyses were conducted for the univariate relationships to determine available power in the present sample to detect the observed effects. Analyses indicated that at alpha = .05 with the present sample size of n = 428, in examining effects as the relevant proportions scored as “yes” to a given 2 × 2 contingency table (e.g., percent “yes” for lifetime alcohol use by gender), power (1-β) ranged from .67 to .99 for most analyses. However, power was substantially lower for analyses related to recent heavy episodic use (range β = .04–.68), likely reflecting the low rate of occurrence (19%) of heavy drinking episodes in this sample.

Multivariate logistic regressions

Multivariate logistic regressions were conducted for each dependent variable for which there was more than one significant independent variable (lifetime and current alcohol use). The relative contribution of independent variables to each model was assessed by entering each variable in a separate block and examining the step chi-squares. Gender and parental alcohol use were examined in relation to life-time alcohol use, whereas these variables and level of acculturation were examined in relation to current alcohol use. Results are reported in Table 6 and Table 7. Gender and parental alcohol use each significantly related to lifetime alcohol use and gender, parental alcohol use and level of acculturation each significantly related to current alcohol use in the multivariate analyses. Reversing the order in which the independent variables were entered into the models did not change these results.

TABLE 6.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regressions for lifetime alcohol use

p < .05.

TABLE 7.

Stepwise multivariate logistic regressions for current alcohol use

| Step | Independent variable | Step χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender* | 5.77 | .02 |

| 2 | Parental alcohol use* | 7.55 | .006 |

| 3 | Acculturation* | 6.76 | .009 |

p < .05.

Analyses of moderation effects

A moderator effect is an interaction effect, a product of the independent variable and moderator, and thus the main effect of both the independent variable and the moderator are included in the model (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Moderating relationships were tested for each dependent variable for the following hypothesized effects: the interaction of level of acculturation and parental alcohol use, and the interaction of level of acculturation and gender (for Korean Americans only). In addition, although not hypothesized, the potential moderating effect of gender on the relation-ship between parental alcohol use and lifetime and current alcohol use was explored to follow up the main effects identified for these independent variables. Ethnicity was explored as a moderator of the relationship between each independent variable (i.e., gender, acculturation, parental alcohol use, and ALDH2 status) and all alcohol use variables. Interactions were analyzed in a series of logistic regressions using a combination of ethnicity and an independent variable and their interaction in each analysis. All significant two-way interactions inclusive of a combination of gender, parental alcohol use, and/or level of acculturation were followed up with examination of three-way interactions including ethnicity as a third independent variable.

Results indicated no interaction between level of acculturation and gender for alcohol use among Korean Americans. Exploratory analyses revealed that the moderating effect of ethnicity on the relationship between level of acculturation and heavy episodic use approached significance (step χ2 = 5.05, 1 df, p = .03, corrected p = .017, OR = 3.55, CI = 1.16–10.89). A one-unit increase in level of acculturation was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of heavy episodic use for Chinese Americans (step χ2 = 11.70, 1 df, p = .001, OR = 3.97, CI = 1 74–9.07) but not Korean Americans (step χ2 = .05, 1 df, p = .82, OR = 1.09, CI = 0.51–2.33). None of the other interactions terms tested reached statistical significance.

Indirect effects

An indirect effect of ALDH2 on adolescent alcohol use via parental alcohol use was predicted. However, when parental alcohol use was regressed on ALDH2 status (Baron and Kenny, 1986), the relationship was nonsignificant. Hence, further examination of indirect effects was not warranted.

Discussion

The present study employed an integrative approach in examining drinking behavior among Asian American youth. We examined the influence of parental alcohol use, acculturation and ALDH2 status on various indices of alcohol consumption among Chinese American and Korean American first-year college students, taking into account potential moderating effects of ethnic subgroup and gender. In addition, hypothesized moderating relationships among independent variables were examined. Results provided mixed support for study hypotheses. Male gender and parental drinking were significantly related to a greater likelihood of lifetime and current alcohol use, and higher levels of acculturation significantly related to a greater likelihood of current and heavy episodic use. A trend was observed whereby ethnicity moderated the relationship between acculturation and heavy episodic drinking. Contrary to previous studies, ALDH2 status did not account for differences in alcohol use in either ethnic group, and additional proposed moderating and indirect relationships among independent variables were not supported.

The observed relationships between parental drinking and alcohol use among Asian American youth in this sample were consistent with our hypotheses and congruent with previous findings (Newcomb and Bentler, 1986). Although parental drinking predicted lifetime and current alcohol use, it was not associated with our index of heavy drinking. This finding is similar to results from twin studies of alcohol use that have found problematic use may be less influenced by shared environment than initiation or regular use of alcohol (Heath et al., 1991). Further, alcohol use and alcohol use disorders may be more heritable in adulthood than adolescence consequent to the greater power of social influences during adolescence (Koopmans and Boomsma, 1996).

As predicted, acculturation was significantly related with drinking behavior (current and heavy episodic use), replicating the results of previous studies (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004; Sue et al., 1979). Despite low statistical power, a moderating effect of ethnicity on the relationship between acculturation and heavy episodic drinking approached statistical significance. This moderating trend indicated that a one-unit increase in acculturation score corresponded with a fourfold greater likelihood of heavy episodic drinking for Chinese American college students but no apparent increased risk of heavy episodic drinking for Korean American college students. Previously reported variations in patterns of alcohol consumption across these groups support the possibility of a differential impact of acculturation. In particular, population estimates in Asia show that whereas overall rates of alcohol abuse and dependence among Koreans are as high as or higher than those in the United States, abuse and dependence rates among Chinese are lower than those in the United States (Helzer et al., 1990). Given that alcohol use patterns in Korea approximate U.S. norms to a greater extent than those in China, the acculturative process would be expected to correspond with greater increases in alcohol use for Chinese Americans than Korean Americans, acting as a more robust correlate of drinking for this subgroup. The present finding provides added, albeit qualified, support for the importance of disaggregating subgroups subsumed within the broad label of Asian American.

Our hypothesis that acculturation would moderate the relationship between parental alcohol use and participant drinking, with decreasing correspondence between parental and adolescent use as a function of increased acculturation, was not supported in the present sample. Nonetheless, in light of recent findings indicating that psychosocial factors may mediate or moderate the relationship between acculturation and drinking behavior among Asian American youth (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004), the joint effects of acculturation and psychosocial factors on drinking should be a continued focus of study. Future studies of Asian Americans should therefore consider indirect as well as direct influences of acculturation on alcohol use, and ethnic subgroup differences in risk and protective factors for drinking in this population should be further explored.

The lack of association between ALDH2 status and current alcohol use or heavy episodic drinking stands in contrast to findings from previous studies linking presence of the ALDH2*2 allele to reduced rates of heavy episodic drinking (Luczak et al., 2001; Takeshita and Morimoto, 1999; Wall et al., 2001), alcohol use (Takeshita and Morimoto, 1999; Wall et al., 2001) and alcohol dependence (Luczak et al., 2004; Thomasson et al., 1991). In particular, in recent studies of Asian American college students, Luczak et al. (2001) and Wall et al. (2001) found that ALDH2 status was associated with prior 2-week and lifetime heavy episodic drinking, respectively. However, the aforementioned studies included participants 21 to 26 years of age, whereas the present sample consisted of 18- to 19- year-old undergraduates, recruited shortly after matriculation. This age difference has relevance in light of findings suggesting that ALDH2 is associated with alcohol consumption only following initiation and increased drinking experience (Wall et al., 2001). Taken in concert, these findings imply that a learned association between alcohol consumption and the physiological response to alcohol may result in decreased drinking rates with greater drinking experience among individuals possessing the ALDH2*2 allele.

Congruent with this interpretation, relationships between ALDH2 status and alcohol expectancies have been reported (McCarthy et al., 2000, 2001), indicating that possession of the ALDH2*2 allele may influence drinking behavior through a mediation pathway involving expectancy formation. Unfortunately, alcohol expectancies were not assessed in the present sample. However, it is conceivable that the present participants were assessed prior to having attained sufficient drinking experience to establish expectancies regarding physiological consequences of alcohol consumption. This position is supported in that participants in the study by Luczak et al. (2001) reported higher rates of 2-week heavy episodic drinking than reported in the present sample (27% vs 19%, respectively), a difference likely accounted for by the age differences between participants in the respective studies. However, the small proportion of our participants who reported recent heavy drinking episodes also limited statistical power, which may have contributed to the failure to detect a significant relationship of ALDH2 status with heavy episodic drinking. Longitudinal studies are required to further explicate the role of ALDH2 in expectancy formation (McCarthy et al., 2001) as well as to determine the degree of drinking experience necessary to reveal ALDH2 effects on drinking behavior.

Failure to detect a significant relationship between ALDH2 status and alcohol use precluded examination of the proposed indirect influence of parental drinking on the relationship between ALDH2 and alcohol use. However, taken with previous reports linking ALDH2 status to alcohol use (e.g., Takeshita and Morimoto, 1999; Wall et al., 2001), the present findings relating parental alcohol use to lifetime and current drinking support further examination of this relationship. We did not observe a relationship between participant ALDH2 status and parental drinking in the present sample, suggesting that possession of an ALDH2*2 allele by at least one parent is not sufficient to infer decreased exposure to parental drinking. The lack of association between participant ALDH2 status and parental drinking is also not surprising considering that 90% of study participants with an ALDH2*2 allele were heterozygous (inheriting the allele from one parent) and our estimate of parental alcohol use was global (any alcohol use by either parent, with no assessment of heavy drinking). This lack of association does provide some support to our interpretation of this parental drinking variable as a proxy for modeling of alcohol use. Future studies could re-assess this model with an older sample or more sensitive indices of parental drinking behavior (e.g., frequency or quantity of each parent’s alcohol use) to discern the relative influence of modeling and genetic mechanisms.

The present findings should be interpreted within the context of study limitations. Participants were Asian American undergraduates at a competitive university; caution should therefore be taken in extrapolating present findings to other populations of Asian youth. The distribution of acculturation scores in this sample was comparable to other samples of Asian American students (Johnson et al., 2002); however acculturation variables could relate differently to alcohol use in a broader sample. Reliance on participant reports for assessment of parental drinking limits the accuracy of these data. However, the global measure of parental drinking employed in the present study likely limited measurement error. An additional shortcoming concerns the dichotomous nature of the alcohol use variables employed. Although categorical evaluation of alcohol use variables was necessary owing to highly skewed distributions, the broad nature of these dichotomies restricts sensitivity for assessing the relationships addressed in this study. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the present data precluded examination of causal relationships. However, as these cohorts are being followed longitudinally, examination of causal mechanisms influencing alcohol use in this group will be possible in the future.

Results of the present study have valuable implications for future research. The present findings suggest that the influence of an established genetic determinant of drinking behavior in Asians (possession of an ALDH2*2 allele) may remain latent through late adolescence. Future research might seek to address developmental aspects of ALDH2 effects on alcohol expectancy formation, and in turn drinking behavior, among Asian American adolescents. Longitudinal studies are needed to identify temporal junctures at which environmental factors interact with or give way to genetic factors in predicting alcohol use in this population. In addition, the possibility that ethnicity moderates the effect of acculturation on alcohol use reinforces the importance of attending to subgroup differences in future studies of substance use etiology in Asian Americans (Chi et al., 1989; Harachi et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2004). Identification of subgroup-specific etiologic factors will inform the design of culturally tailored treatment or prevention programs for Asian American subpopulations.

TABLE 4.

Step chi-squares, odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) for current alcohol use

| Independent variable | Step χ2 | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 5.77 | .016a | 0.63 | 0.43–0.92 |

| ALDH2 | 0.20 | .65 | 0.92 | 0.62–1.35 |

| Parental alcohol use | 7.62 | .006a | 1.98 | 1.21–3.24 |

| Acculturation | 6.12 | .013a | 1.70 | 1.11–2.60 |

Significance levels indicated at adjusted p < .017.

Footnotes

This work was supported by California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program grants 10RT-0142 and 12RT-0004 and National Institutes of Health grants K02 AA00269, T32 AA13525 and P50 AA07611.

References

- Abrams DB, Niaura RS. Social learning theory. In: Blane HT, Leonard KE, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. pp. 181–226. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression; Testing and interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu PD, Sue S, Zane NW, Nakamura CY. Ethnic differences in alcohol consumption among Asians and Caucasians in the United States: An investigation of cultural and physiological factors. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1989;50:261–267. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Tildesley E, Hops H, Andrews J. The influence of parent, sibling, and peer modeling attitudes on adolescent use of alcohol. Int. J. Addict. 1993;28:853–880. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au JG, Donaldson SI. Social influences as explanations for substance use differences among Asian-American and European-American adolescents. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 2000;32:15–23. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Banerjee S. Family influences on alcohol abuse and other problem behaviors among Black and White adolescents in a general population sample. J. Res. Adolesc. 1994;4:183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Social Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. Cultural identification and substance use in North America: An annotated bibliography. Subst. Use Misuse. 1998;33:1315–1336. doi: 10.3109/10826089809062219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Myers MG, Lippke L, Tapert SF, Stewart DG, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR): A measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998;59:427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Alarcon EH. Integrating cultural variables into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. J. Drug Issues. 2002;32:783–810. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-C, Lu R-B, Chen Y-C, Wang M-F, Chang Y-C, Li T-K, Yin S-J. Interaction between the functional polymorphisms of the alcohol-metabolism genes in protection against alcoholism. Amer. J. Human Genet. 1999;65:795–807. doi: 10.1086/302540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi I, Lubben JE, Kitano HH. Differences in drinking behavior among three Asian-American groups. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1989;50:15–23. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb DW, Edenberg HJ, Bosron WF, LI T-K. Genotypes for aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and alcohol sensitivity: The inactive ALDH2(2) allele is dominant. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:314–316. doi: 10.1172/JCI113875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar R, Serlin RC, Omer H. Misuse of statistical tests in three decades of psychotherapy research. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1994;62:75–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moor C, Elder JP, Young RL, Wildey MB, Molgaard CA. Generic tobacco use among four ethnic groups in a school age population. J. Drug Educ. 1989;19:257–270. doi: 10.2190/GMQF-AGWN-7A62-QFR8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V, Bauman KE. Parental and peer characteristics as modifiers of the bond-behavior relationship: An elaboration of control theory. J. Hlth Social Behav. 1992;33:66–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedde HW, Agarwal DP, Fritze G, Meier-Tackmann D, Singh S, Beckmann G, Bhatia K, Chen LZ, Fang B, Lisker R, Paik YK, Rothhammer F, Saha N, Segal B, Srivastava LM, Czeizel A. Distribution of ADH2 and ALDH2 genotypes in different populations. Human Genet. 1992;88:344–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00197271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Acculturation and parental attachment in Asian-American adolescents’ alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Hlth. 2003;33:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Asian American adolescents’ acculturation, binge drinking, and alcohol- and tobacco-using peers. J. Commun. Psychol. 2004;32:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Kim S, Choi Y. Etiology and prevention of substance use among Asian American youth. Prev. Sci. 2001;2:57–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1010039012978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Meyer J, Jardine R, Martin NG. The inheritance of alcohol consumption patterns in a general population twin sample: II. Determinants of consumption frequency and quantity consumed. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1991;52:425–433. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Canino GJ, Yeh E-K, Bland RC, Lee CK, Hwu HG, Newman S. Alcoholism—North America and Asia: A comparison of population surveys with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1990;47:313–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810160013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Wall TL, Guanipa C, Terry-Guyer L, Velasquez RJ. The psychometric properties of the Orthogonal Cultural Identification Scale in Asian Americans. J. Multicult. Counsel. Devel. 2002;30:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Nagoshi CT, Ahern FM, Wilson JR, Yuen SHL. Cultural factors as explanations for ethnic group differences in alcohol use in Hawaii. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 1987;19:67–75. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1987.10472381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Nagoshi CT. Asians, Asian-Americans and alcohol. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 1990;22:45–52. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1990.10472196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Nagoshi CT, Danko GP, Honbo KM, Chau LL. Familial transmission of alcohol use norms and expectancies and reported alcohol use. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1990;14:216–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe K, Newcomb MD. Demographic and psychosocial risk for alcohol use: Ethnic differences. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1996;57:521–530. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano HHL, Chi I. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Use among U.S. Ethnic Minorities. Research Monograph No. 18 DHHS Publication No. (ADM) 89-1435. Washington: Government Printing Office; 1989. Asian Americans and alcohol: The Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and Filipinos in Los Angeles; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans JR, Boomsma DI. Familial resemblances in alcohol use: Genetic or cultural transmission? J. Stud. Alcohol. 1996;57:19–28. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Corbett K, OH C, Carr LG, Wall TL. Religious influences on heavy episodic drinking in Chinese-American and Korean-American college students. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003;64:467–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Wall TL, Shea SH, Byun SM, Carr LG. Binge drinking in Chinese, Korean, and white college students: Genetic and ethnic group differences. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2001;15:306–309. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Wall TL, Cook TAR, Shea SH, Carr LG. ALDH2 status and conduct disorder mediate the relationship between ethnicity and alcohol dependence in Chinese, Korean, and white American college students. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113:271–278. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Brown SA, Carr LG, Wall TL. ALDH2 status, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol response: Preliminary evidence for a mediation model. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2001;25:1558–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Wall TL, Brown SA, Carr LG. Integrating biological and behavioral factors in alcohol use risk: The role of ALDH2 status and alcohol expectancies in a sample of Asian Americans. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:168–175. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Substance use and ethnicity: Differential impact of peer and adult models. J. Psychol. 1986;120:83–95. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1986.9712618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG. Alcohol use among adolescents. Alcohol Hlth Res. World. 1998;22:85–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G-S, Wang M-F, Chen CY, Luu S-U, Chau H-C, Li TK, Yin S-J. Involvement of acetaldehyde for full protection against alcoholism by homozygosity of the variant allele of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in Asians. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:463–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Passages to adulthood: The adaptation of children of immigrants in Southern California. In: Hernandez D, editor. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1999. pp. 478–545. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Social Psychol. Bull. 1994;20:580–591. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Bogardis J, Schuller R, Leo GL, Sobell LC. Is self-monitoring of alcohol consumption reactive? Behav. Assess. 1989;11:477–458. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Nakamura CY. An integrative model of physiological and social/psychological factors in alcohol consumption among Chinese and Japanese Americans. J. Drug Issues. 1984;14:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Ito J. Alcohol drinking patterns among Asian and Caucasian Americans. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1979;10:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Ahuna C, Khoo G. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: Concurrent and factorial validation. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992;52:1041–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: An initial report. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1987;47:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Tsuritani I, Yamada Y. Contribution of genetic polymorphisms in ethanol-metabolizing enzymes to problem drinking behavior in middle-aged Japanese men. Behav. Genet. 2002;32:229–236. doi: 10.1023/a:1019711812074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita T, Morimoto K. Self-reported alcohol-associated symptoms and drinking behavior in three ALDH2 genotypes among Japanese university students. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1999;23:1065–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson HR, Edenberg HJ, Crabb DW, Mai X-L, Jerome RE, Li T-K, Wang S-P, Lin Y-T, Lu R-B, Yin S-J. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes and alcoholism in Chinese men. Amer. J. Human Genet. 1991;48:667–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, Palmer P. Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addict. Res. Theory. 2002;10:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Varma SC, Siris SG. Alcohol abuse in Asian Americans: Epidemiological and treatment issues. Amer. J. Addict. 1996;5:136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Nemeroff CB, Ritchie JC, Ehlers CL. Cortisol responses following placebo and alcohol in Asians with different ALDH2 genotypes. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:207–213. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Shea SH, Chan KK, Carr LG. A genetic association with the development of alcohol and other substance use behavior in Asian Americans. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001;110:173–178. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Thomasson HR, Ehlers CL. Investigator-observed alcohol-induced flushing but not self-report of flushing is a valid predictor of ALDH2 genotype. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1996;57:267–272. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Thomasson HR, Schuckit MA, Ehlers CL. Subjective feelings of alcohol intoxication in Asians with genetic variations of ALDH2 alleles. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1992;16:991–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. J. Subst. Abuse. 2000;12:287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addict. Behav. 2004;29:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane NW, Kim JC. Substance use and abuse. In: Nolan WS, Zane NW, Takeuchi DT, Young KNJ, editors. Confronting Critical Health Issues of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 316–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Sasao T. Research on drug abuse among Asian Pacific Americans. Drugs Soc. 1992;6:181–209. [Google Scholar]