Abstract

Previous laboratory research suggests that stress and anxiety increase smoking motivation and are attenuated by smoking. There is little experimental data, however, on the relationship between depressed or sad mood and smoking. This study investigated if induced sadness would have a differential effect on smoking behavior compared to a neutral mood state. Baseline depression scores were examined as a potential moderator of this relationship. Mood changes were also tested as a potential mediator. Smokers (N = 121) were randomly assigned to receive either a sad mood induction or a neutral mood induction via standardized film clips. There were interactive effects of depression scores and condition on smoking behavior in that smoking duration and the number of cigarette puffs were greater in response to the sad condition among participants with higher depression scores. There was also a marginal interactive effect on the change in expired air carbon monoxide among this subsample, however, no differences in latency to smoke, or craving were observed. The changes in positive mood appeared to partially mediate the effect of condition on smoking behavior among participants with high depression scores. There was no significant modifying effect of gender or mediating effect of negative mood changes. The results provide preliminary support that decreases in positive mood may have a greater influence on smoking behavior among depression prone smokers than less psychiatrically vulnerable smokers.

Keywords: Smoking, depression, negative mood, positive mood, mood induction

Introduction

Negative mood has been proposed as an important psychological factor in the initiation, maintenance, and relapse of smoking behavior (Brandon, 1994). Smokers often report greater motivation to smoke in response to increases in negative mood (McKennell, 1970; Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003) and maintain strong expectancies that smoking alleviates unpleasant feelings (Copeland, Brandon, & Quinn, 1995; Spielberger, 1986). Moreover, postcessation relapse is often precipitated by increases in negative mood (Brandon, Tiffany, Obremski, & Baker, 1990; Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Hickcox, 1996; Shiffman & Waters, 2004).

Experimental evidence that negative mood actually increases smoking behavior, however, is mixed. There is some evidence that direct or anticipatory exposure to stressors (e.g., performing stressful tasks, hearing aversive noises) increases urge to smoke and the amount and intensity of smoking (Cherek, 1985; Dobbs, Strickler & Maxwell, 1981; Payne, Schare, Levis, & Colletti, 1991; Pomerleau & Pomeraleau, 1987; Rose, Ananda & Jarvik, 1983; Schachter, Silverstein, & Perlick, 1977). In contrast, naturalistic diary-based studies have found either little association between negative mood and smoking motivation (Shiffman et al., 2002) or only an effect for male smokers (Delfino, Jamner, & Whalen, 2001).

There is limited research on the effect of negative mood states on smoking behavior via non-stressful induction methods such as exposure to images and/or sounds intended to elicit a more general unpleasant state (Kassel et al., 2003). Conklin and Perkins (2005) found that negative induced mood (i.e., using picture slides and music clips) resulted in shorter latency to smoke and a greater number of cigarette puffs relative to neutral and positive induced moods. A similar study demonstrated that negative induced mood (i.e., using music clips) increased smoking urge and progressive ratio responding for cigarette puffs compared to positive induced mood (Willner & Jones, 1996).

Taken altogether, these conflicting findings are primarily based on the effects of stress or anxiety on smoking behavior. Few studies have examined the relationship between depressive mood states and smoking. Although some overlap exists, low positive mood and arousal have been shown to be characteristic of depression not anxiety (APA, 2000; Clark & Watson, 1991). Willner and Jones (1996) purportedly examined the effects of “depressed” versus positive induced mood on smoking. However, the mood manipulation altered positive mood ratings but had no differential effect on negative mood ratings. Moreover, it is unclear whether the negative classical music clip specifically induced depressed mood rather than a more general distressing mood state.

Psychiatric vulnerability may contribute to the association between negative mood and smoking. Individuals who are vulnerable to depression may be more motivated to smoke in response to mood fluctuations than less vulnerable individuals. A depression history is associated with an increased likelihood of becoming a smoker, greater nicotine dependence, and greater difficulty quitting smoking (Anda et al., 1990; Borrelli et al., 1998; Breslau, Kilbey, & Andreski, 1991; Degenhardt & Hall, 2001; Hitsman, Borrelli, McChargue, Spring, & Niaura, 2003; Kendler et al., 1993; Lasser et al., 2000). Correlational studies have shown that depressed smokers are more likely to report smoking in response to negative emotional situations compared to non-depressed smokers (Carton, Jouvent, & Widlöcher, 1994) and that depressive symptoms are associated with smoking expectancies (Friedman-Wheeler, Ahrens, Haaga, McIntosh, & Thorndike, 2007). Likewise, laboratory data suggest that the subjective effects of smoking (e.g., psychomotor enhancement, craving and negative mood reduction) may differ between depressed and non-depressed smokers (Malpass & Higgs, 2007; Spring et al., 2008). No experimental research, however, has examined the effect of negative induced mood on smoking motivation in depressed or depression prone smokers relative to non-depressed smokers. Previous studies in this area have either not measured depressive symptoms, excluded participants who scored within a clinical range at baseline (Conklin & Perkins, 2005), or only evaluated the effects of smoking on mood (Malpass & Higgs, 2007; Spring et al., 2008). Thus, it remains to be determined whether psychiatric vulnerability increases smoking motivation in response to acutely negative mood states.

The present study investigated the effect of sad induced mood on smoking behavior. It was hypothesized that exposure to a sad mood induction would result in greater smoking motivation exposure to a neutral mood induction. In addition, it was anticipated that participants with higher baseline depression scores would demonstrate greater smoking behavior in response to the sad condition than the neutral condition. Changes in negative and positive mood ratings were also examined as potential mediators of the relationship between condition and smoking.

METHOD

Participants

One hundred twenty-one smokers (61 men, 60 women) participated in 1 laboratory session. Eligibility requirements included smoking at least ten cigarettes per day for at least 1 year. Volunteers were excluded for current serious psychiatric or medical illness1. Participants [M age = 33.78 ± 14.84 years] smoked a mean of 15.10 ± 5.98 cigarettes per day for a mean of 14.51 ± 13.54 years. The majority of participants identified themselves as either Caucasian (45%) or African American (44%). Participants had a mean score of 12.93 ± 9.28 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II; 38% percent of participants met clinical criteria for depressive symptoms (i.e., score ≥ 14).

Measures

Breath carbon monoxide (CO) samples were collected to encourage compliance and to measure smoke inhalation during the experiment using a Bedfont Micro III Smokerlyzer. All measures and tasks were administered via computer software (DirectRT and Medialab). Measures included a 22-item questionnaire that assessed demographics, smoking history, and desire to quit smoking; the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker & Fagerström, 1991), the Urge Rating Scale (Kozlowski, Pillitteri, Sweeney, Whitfield & Graham, 1996); the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale – Revised (Hughes, 1992; 2007); the Beck Depression Inventory – II (Current) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); the Film Questionnaire (Rottenberg et al., 2007), a 25-item measure of emotions participants may have experienced while watching the film clip on a 9-point Likert scale and other questions about the film; and the Mood Scale (Diener & Emmons, 1984), a 9-item measure of positive mood and negative mood on a 7-point Likert scale that yielded 2 subscales. The negative mood subscale was not reliable in this study (alpha coefficients ranged from .31 to .59) and only 1 item correlated with BDI-II scores. Since the main focus of the study was to examine characteristics of sad mood and the reliability and validity of the other 4 items appeared questionable, only the “unhappy” item was used for analyses of negative mood ratings.

Mood Induction

Participants were randomly assigned to view either a 3-minute scene of a boy crying over his father’s death from the movie The Champ (Lovell & Zeffirelli, 1979) to elicit sad mood or a 3-minute scene of the Alaskan wilderness from Alaska’s Wild Denali (Hardesty, 1997) to elicit neutral mood. The selected clips were determined by previous research on the effectiveness of eliciting sadness and neutral mood states through films (Gross & Levenson, 1995; Haggeman et al., 1999; Hewig et al., 2005; Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross, 2007).

Procedure

Participants smoked their last cigarette 1 hour prior to their appointment. Participants first provided a breath CO sample and completed baseline measures. Next, they watched a film clip and completed post-film measures of mood and urge2. Participants were then instructed by the computer to smoke 1 of their own cigarettes ad libitum. Experimenters observed participants through a one-way mirror and recorded latency to smoke and total time smoked and the number of cigarette puffs. This naturalistic procedure was employed so as not to influence smoking reinforcement (Conklin & Perkins, 2005). Only 1 experimenter recorded smoking behavior. Experimenters were not completely blind to participant condition since film sounds were audible through the one-way mirror. Participants pressed a computer key after smoking and then completed post-smoking measures of mood, urge, withdrawal, and reactions to the film. A positive Velten mood induction was then administered to participants in the sad condition to offset temporarily induced sad mood (Westerman et al., 1996). Participants provided a final breath CO sample before being paid and debriefed.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 15. Analyses of variance were used to test for group equivalence, to evaluate the effectiveness of the mood induction, and to examine the effect of condition on smoking behavior. Linear regression was used to evaluate the moderating effect of depression scores on smoking outcomes in response to condition (Frazier, Tix, & Barron 2004). Simple slope analyses were conducted for post-hoc probing of significant moderator effects (Holmbeck, 2002). Changes in negative and positive mood were examined as potential mediators of the relationship between condition and smoking outcomes (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz 2007a).3

RESULTS

Manipulation Check

A series of ANOVAs demonstrated that conditions were equivalent on all variables.

Participants exposed to the sad condition reported a greater increase in unhappiness ratings on the Mood Scale [1.31 ± 1.85 vs. −.02 ± 1.51; F(1, 119) = 18.67, p <.001] as well as a greater decrease in positive mood ratings compared to participants exposed to the neutral condition [−1.54 ± 1.63 vs. −.06 ± 1.20; F(1, 119) = 32.05, p <.001]. On the Film Questionnaire, participants in the sad condition reported feeling more unhappiness [F(1, 119) = 67.53, p <.001] and sadness [F(1, 119) = 81.85, p <.001] as well as less happiness [F(1, 119) = 82.49, p <.001] and joy [F(1, 119) = 69.71, p <.001] in response to the film than participants in the neutral condition.

Smoking Behavior

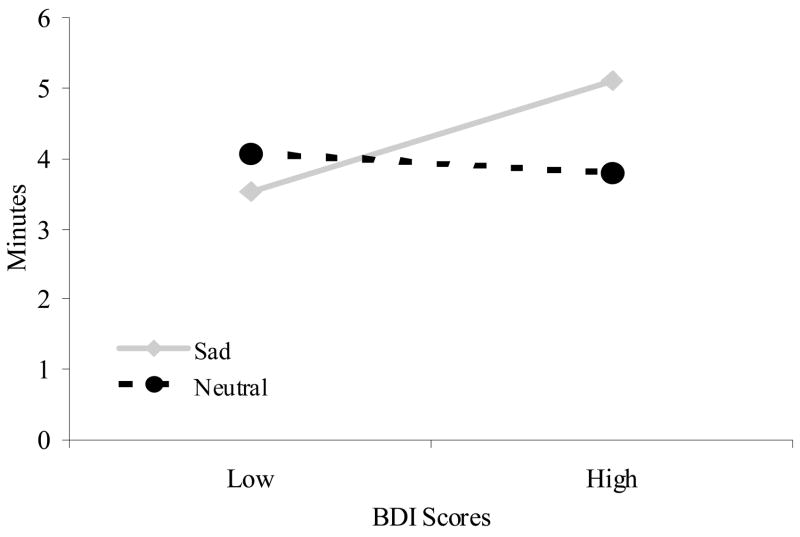

Contrary to predictions, there was no effect of condition on smoking outcomes [p’s > .10]. Regression analyses, however, revealed an interaction of depression scores and condition on smoking duration [R2 change = .04; F(1, 117) = 5.03, p = .03], the number of cigarette puffs [R2 change = .04; F(1, 117) = 4.74, p = .03], and the change in expired air carbon monoxide from baseline to post-smoking [R2 change = .03; F(1, 117) = 3.93, p <.05]. Post hoc probing for smoking duration demonstrated that the simple slope of BDI scores was significant for the sad condition [β = 2.96; t = 2.43, p = .02] but not the neutral condition [p >.10]. The direction indicated that smoking duration was longer at higher BDI scores among smokers exposed to the sad condition than at lower scores (see Figure 1). Further post hoc testing revealed that the simple slope of condition was significant for high (1 standard deviation above the mean) centered BDI scores [β = 54.63; t = 2.60, p = .01] but not low (1 standard deviation below the mean) centered BDI scores [p >.10]. The direction demonstrated that the difference in smoking duration by condition was greater among smokers with higher BDI scores compared to smokers with lower scores (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Smoking Duration as a Function of Condition and Depression Scores1

1Low and high BDI scores represent the 25th and 75th percentiles on BDI–II

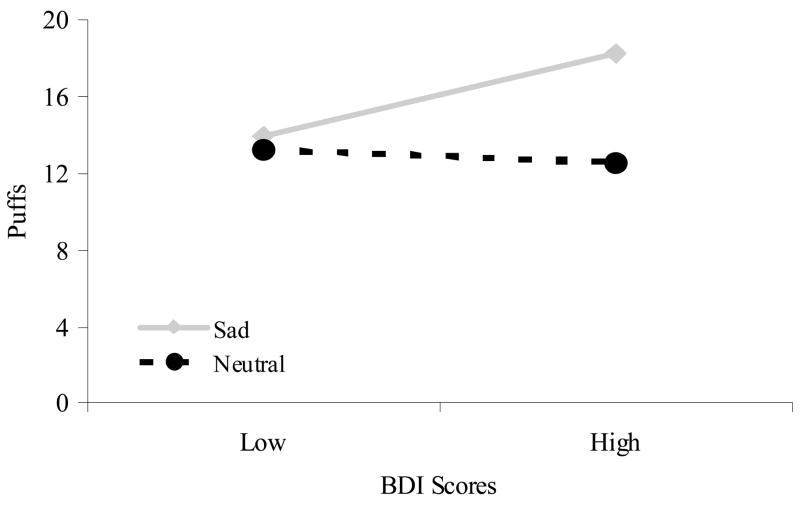

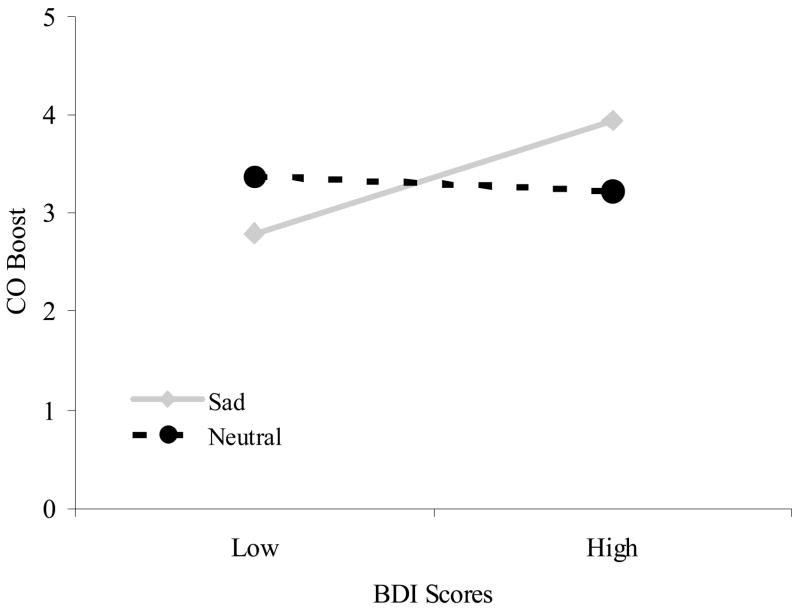

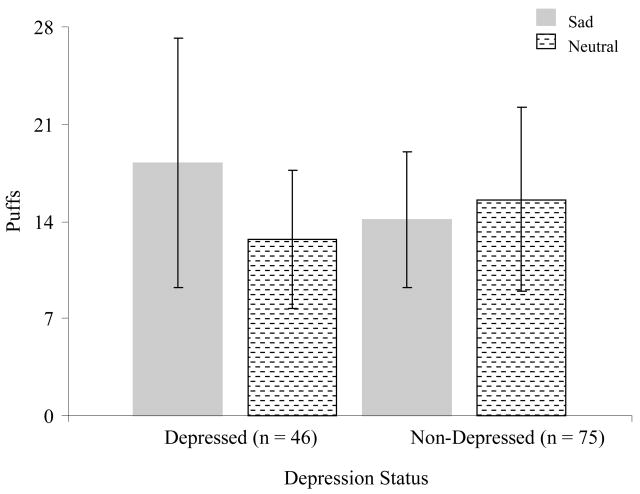

Similar results were observed for number of cigarette puffs. There was a trend towards the simple slope of BDI scores to be significant for the sad condition [β = .18; t = 1.86, p = .065] but not the neutral condition [p >.10]. The direction indicated that there was a tendency for the number of cigarette puffs to be greater at higher BDI scores among smokers exposed to the sad condition than at lower scores (see Figure 2). Additional post hoc testing showed that the simple slope of condition was significant for high BDI scores [β = 3.81; t = 2.27, p = .03] but not low BDI scores [p >.10]. Therefore, the difference in cigarette puffs by condition was greater among smokers with higher BDI scores compared to smokers with lower scores (see Figure 2). There was also a trend towards the simple slope of BDI scores to be significant for the sad condition [β = .07; t = 1.91, p = .059] but not the neutral condition [p >.10] for the change in expired air carbon monoxide. The direction indicated that there was a tendency for the change in carbon monoxide from baseline to post-smoking to be greater at higher BDI scores among smokers exposed to the sad condition than at lower scores (see Figure 3). Further post hoc probing revealed that the simple slope of condition was not significant for either high BDI scores or low BDI scores [p’s >.10] (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cigarette Puffs as a Function of Condition and Depression Scores1

1Low and high BDI scores represent the 25th and 75th percentiles on BDI–II

Figure 3.

Change in Expired Air Carbon Monoxide from Baseline to Post-Smoking as a Function of Condition and Depression Scores1

1Low and high BDI scores represent the 25th and 75th percentiles on BDI–II

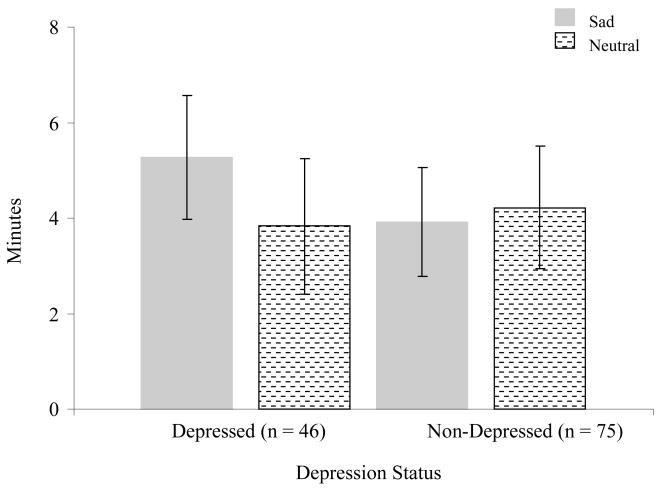

The moderating effect of depression scores on smoking outcomes was further evaluated by comparing participants with scores below 14 on the BDI–II (“non-depressed” n = 75) and scores 14 or more (“depressed” n = 46)4. These analyses revealed interactive effects of condition and depression status on smoking duration [F(1, 117) = 13.05, p <.001] and cigarette puffs [F(1, 117) = 8.59, p <.01]. Simple effects analyses demonstrated that depressed participants exposed to the sad condition smoked longer [5:16 ± 1:18 minutes; F(1, 44) = 12.37, p <.01] than depressed participants exposed to the neutral condition [3:50 ± 1:25 minutes], but there was no differential effect of condition on smoking duration among non-depressed participants [p >.10] (see Figure 4). Likewise, depressed participants took more cigarette puffs in response to the sad condition [18.19 ± 8.99; F(1, 44) = 6.81, p = .01] than the neutral condition [12.72 ± 4.97)] (see Figure 5). However, the number of cigarette puffs did not vary by condition among non-depressed participants [p >.10]. There was interaction of condition and depression status on the change in expired air carbon monoxide [p >.10].

Figure 4.

Smoking Duration as a Function of Condition and Depression Status1

1Depressed status and non-depressed status represent scores ≥ to 14 and < 14 on BDI–II, respectively

Figure 5.

Cigarette Puffs as a Function of Condition and Depression Status1

1Depressed status and non-depressed status represent scores ≥ to 14 and < 14 on BDI–II, respectively

Mechanisms of Change

Three regression analyses were performed to test the effect of the change in positive mood ratings from baseline to post-film on the relationship between condition and number of cigarette puffs among the subsample of smokers with high BDI scores (MacKinnon et al., 2007a): (1) the number of cigarette puffs was regressed on condition; (2) the change in positive mood ratings from baseline to post-film was regressed on condition; and (3) the number of cigarette puffs was regressed on the change in positive mood ratings controlling for condition. The results of all three steps were significant, [R2 = .13; F(1, 44) = 6.81, p = .01; R2 = .25; F(1, 44) = 14.93, p <.001; R2 change = .09; F(1, 43) = 4.76, p = .04] and verified that the change in positive mood ratings had a significant effect on the number of cigarette puffs among depressed participants after controlling for condition. Moreover, the results showed that the effect of condition remained significant [β = .54, p = .01] after adding the change in positive mood ratings to the model suggesting a partial mediational relationship. The asymmetric confidence limit for the partially mediated effect was between − 5.53 and − .28 (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007b), indicating a significant indirect effect of the changes in positive mood ratings on smoking behavior.5

DISCUSSION

As hypothesized, depression scores affected smoking behavior in response to the mood induction. Participants with high depression scores exposed to the sad condition took more cigarette puffs, smoked longer, and experienced a greater increase in expired air carbon monoxide from baseline to post-smoking compared to participants with low depression scores. When the sample was divided using a cutoff score on the BDI–II indicative of clinical depression, these effects were significantly greater for the depressed subsample relative to the non-depressed subsample. These results provide preliminary evidence that smoking behavior in response to acute mood states may be associated with depressive symptomatology and correspond to prior research that has shown the subjective effects of smoking and nicotine may vary by depression status (Malpass & Higgs, 2007; Spring et al., 2008).

In addition, the decrease in positive mood ratings from baseline to post-film appeared to partially mediate the relationship between condition and smoking behavior among the depressed subsample. This finding is consistent with previous research that has established a link between positive mood and smoking behavior among individuals vulnerable to depression. Smoking a nicotine cigarette (versus a denicotinized cigarette) has been shown to enhance positive mood in depression prone smokers relative to other smokers (Cook et al., 2007; Spring et al., 2008). There is also evidence that decreases in positive mood results in greater post-cessation craving among anhedonic smokers compared to hedonic smokers (Cook et al., 2004).

The mood induction did not have overall differential effects on smoking behavior. These results are inconsistent with previous research that have shown exposure to stressors or unpleasant images/music increases the amount and intensity of smoking (Cherek, 1985; Conklin & Perkins, 2005; Dobbs, Strickler & Maxwell, 1981; Juliano & Brandon, 2002; Payne, Schare, Levis, & Colletti, 1991; Pomerleau & Pomeraleau, 1987; Rose, Ananda & Jarvik, 1983; Schachter, Silverstein, & Perlick, 1977; Willner & Jones, 1996). Methodological differences may account for the discrepant findings. Other studies utilized longer abstinence periods than the current investigation (Juliano & Brandon, 2002; Willner & Jones, 1996) and stress may have a greater impact on smoking motivation as time from last cigarette increases (Baker et al., 2004). Similarly, smoking topography equipment utilized in previous research (Conklin & Perkins, 2005) may have allowed for greater detection of differences in smoking latency than the naturalistic observation employed in this study.

Some study limitations should be noted. The negative mood subscale of the Mood Scale was unreliable thereby limiting findings for negative mood and smoking. The reliability of smoking outcomes is also somewhat limited. Smoking behavior was assessed using naturalistic observation not standardized topography equipment, only 1 experimenter observed smoking behavior, and experimenters were not sufficiently blind to participants’ condition assignment. These limitations may account for why the results for cigarette puffs, smoking duration, and changes in expired air carbon monoxide appear somewhat inconsistent. Greater cigarette puffs and change in carbon monoxide among the depressed subsample suggest greater cigarette consumption. However, longer smoking duration may reflect decreased motivation. Future smoking studies should utilize more reliable measures of naturalistic observation to address these issues. Smoking outcomes may have also been affected by the variability introduced by having participants smoke their own brand of cigarettes. A final limitation is the assessment of depression using the BDI–II (Current), which does not provide a diagnosis of depression or measure depression history and may be subject to false positives (Shean & Baldwin, 2008).

The results of this preliminary research suggest that smoking behavior in response to acute sadness may differ between depression prone smokers and less psychiatrically vulnerable smokers. In addition, the findings suggest that decreases in positive mood may play a role in this relationship among depression prone smokers. Future research is needed to better understand the potential causal link between depressive states and smoking. These results may also have relevance for the development of psychological interventions for smoking cessation in depressed smokers.

Acknowledgments

Lisa M. Fucito, Ph.D. is now in the Department of Psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine. This research was supported by NIH grants F31-DA022787 and T32-AA015496. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Dr. Clara M. Cheng, Dr. David A. F. Haaga, and Dr. Andrew J. Waters for their assistance in data analyses and helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Volunteers were also excluded for being color blind due to having to complete a color naming task (i.e., Emotional Stroop Task)

Participants also completed the Affective Go/No Go Task and Emotional Stroop Task after these measures.

Gender was also explored as a potential moderator of smoking outcomes. None of these analyses, however, were significant.

Twenty-seven female participants and 19 male participants had high BDI-II scores; these differences were not statistically significant [p >.10].

Changes in negative mood and attentional bias on the Affective Go/No Go and Emotional Stroop tasks were also examined as potential mediators. None of these analyses were significant.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb.

References

- American Psychiatric Association [APA] Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL. Depression and the dynamics of smoking: a national perspective. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Niaura R, Keuthen NJ, Goldstein M, DePue J, Murphy C, et al. Development of major depressive disorder during smoking cessation treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;57:534–538. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v57n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH. Negative affect as motivation to smoke. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1994;3:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: The process of relapse. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;44:1069–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carton S, Jouvent R, Widlöcher D. Nicotine dependence and motives for smoking in depression. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherek DR. Effects of acute exposure to increased levels of background industrial noise on cigarette smoking behavior. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1985;56:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00380697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Perkins KA. Subjective and reinforcing effects of smoking during negative mood induction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:153–164. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Spring B, McChargue D, Hedeker D. Hedonic capacity, cigarette craving, and diminished positive mood. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:39–47. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Spring B, McChargue D. Influence of nicotine on positive affect in anhedonic smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland AL, Brandon TH, Quinn EP. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W. The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: Results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2001;3:225–234. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Jamner LD, Whalen CK. Temporal analysis of the relationship of smoking behavior and urges to mood states in men versus women. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2001;3:235–248. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA. The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:1105–1117. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.47.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs SD, Strickler DP, Maxwell WA. The effects of stress and relaxation in the presence of stress on urinary pH and smoking behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 1981;6:345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Wheeler DG, Ahrens AH, Haaga DAF, McIntosh E, Thorndike FP. Depressive symptoms, depression proneness, and outcome expectancies for cigarette smoking. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31:547–557. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D, Naumann E, Maier S, Becker G, Lurken A, Bartussek D. The assessment of affective reactivity using films: Validity, reliability and sex differences. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26:627–639. [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty T., Producer . Motion Picture. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Video Postcards, Inc; 1997. Alaska’s Wild Denali: Summer in Denali National Park. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewig J, Hagemann D, Seifert J, Gollwitzer M, Naumann E, Bartussek D. A revised film set for the induction of basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 2005;19:1095–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Hitsman B, Borrelli B, McChargue DE, Spring B, Niaura R. History of depression and smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:657–663. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GR. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Tobacco withdrawal in self-quitters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:689–697. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from withdrawal: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9:315–327. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano LM, Brandon TH. Effects of nicotine dose, instructional set, and outcome expectancies on the subjective effects of smoking in the presence of a stressor. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:88–97. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Neale M, Sullivan P, Corey L, Gardner C, Prescott C. Smoking and major depression: A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Pillitteri JL, Sweeney CT, Whitfield KE, Graham JW. Asking questions about urges or cravings for cigarettes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell D, Producer, Zeffirelli F., Director . The Champ [Film], MGM/Pathe Home Video. Culver City, CA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test the significance of the mediated effect. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007a;58:593 –614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007b;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKennell AC. Smoking motivation factors. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1970;9:8–22. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1970.tb00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpass D, Higgs S. Acute psychomotor, subjective, and physiological responses to smoking in depressed outpatient smokers and matched controls. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0612-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TJ, Schare ML, Levis DJ, Colletti G. Exposure to smoking-relevant cues: Effects on desire to smoke and topographical components of smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:467–479. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90054-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Pomerleau OF. The effects of a psychological stressor on cigarette smoking and subsequent behavioral and psychological responses. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Ananda S, Jarvik ME. Cigarette smoking during anxiety-provoking and monotonous tasks. Addictive Behaviors. 1983;8:353–359. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Ray RD, Gross JJ. Emotion elicitation using films. In: Coan J, Allen JJB, editors. The handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. London: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schachter S, Silverstein B, Perlick D. Psychological and pharmacological explanations of smoking under stress. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1977;106:31–40. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.106.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shean G, Baldwin G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2008;169:281–288. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.169.3.281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: Within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ. Negative affect and smoking lapses: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:192–201. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociology solutions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982. pp. 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Psychological determinants of smoking behavior. In: Tollison RD, editor. Smoking and society: toward a more balanced assessment. Lexington, MA: Heath; 1986. pp. 89–134. [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Cook JW, Applehans B, Maloney A, Richmond M, Vaughn J, et al. Nicotine effects on affective response in depression-prone smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0977-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerman R, Spies K, Stahl G, Hesse FW. Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;26:557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Jones C. Effects of mood manipulation on subjective and behavioural measures of cigarette craving. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1996;7:355–363. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]