Abstract

The serine/threonine kinase Akt is a critical enzyme that regulates cell survival. As high Akt activity has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of various human malignancies, inhibition of Akt activation is a promising therapeutic strategy for cancers. We have previously demonstrated that changes in Akt interdomain arrangements from a closed to open conformation occur upon Akt-membrane interaction, which in turn allows Akt phosphorylation/activation. In the present study, we demonstrate a novel strategy to discern mechanisms for Akt inhibition based on Akt conformational changes using chemical cross-linking and 18O labeling mass spectrometry. By quantitative comparison of two interdomain cross-linked peptides which represent the proximity of the domains involved, we found that the binding of Akt to an inhibitor (PI analog) caused the open interdomain conformation where the PH and regulatory domains moved away from the kinase domain, even before interacting with membranes, subsequently preventing translocation of Akt to the plasma membrane. In contrast, the interdomain conformation remained unchanged after incubating with another type of inhibitor (peptide TLC1). Subsequent interaction with unilamellar vesicles suggested that TCL1 impaired particularly the opening of the PH domain for exposing T308 for phosphorylation at the plasma membrane. This novel approach based on the conformation-based molecular interaction mechanism should be potentially useful for drug discovery efforts for specific Akt inhibitors or anti-tumor agents.

Keywords: Akt(PKB), conformation, mass spectrometry, inhibitor, chemical cross-linking

Introduction

Akt (also named protein kinase B), a serine/threonine kinase, plays a crucial role in diverse cellular processes involved in apoptosis, proliferation, and diabetes [1-3]. The primary function of Akt is to promote cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a number of downstream pro-apoptotic factors such as Bad, caspase-9, and forkhead transcription factors [4-6]. An elevated Akt activity has been found in a wide spectrum of human malignancies, including prostate, breast, lung, ovarian, pancreatic and colorectal cancers [7,8]. On the other hand, inhibition of Akt activation has been shown to induce cancer cell death in preclinical and clinical studies [9-11]. These attributes have made Akt a potential pharmacological target for cancer therapy [12] and triggered extensive studies on the detailed molecular mechanism of Akt activation [16-19] as well as the search for specific Akt kinase inhibitors [13-15].

Three highly homologous Akt isomers (Akt1, Akt2 and Akt 3) have been reported in mammals. Each isomer is composed of three distinctive regions including an N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (residues 1-120), a C-terminal regulatory domain (residues 410-480), and a central kinase domain (KD) [16,20,21]. The activation of Akt is mediated by membrane phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) which is generated from 4,5-phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) by phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) upon growth factor stimulation. The binding of PIP3 to the Akt PH domain anchors cytosolic Akt to the plasma membrane where Akt is activated by phosphorylation of T308 and S473 by phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinases (PDKs) [22-25]. It has been well established that the Akt-membrane interaction is a crucial step for the activation. The interaction not only brings Akt into contact with the membrane-bound PDKs, but also results in conformational changes of Akt that are required for its phosphorylation and activation by the upstream enzymes. It has been recognized that the PH domain blocks access of the upstream kinase to T308 and this structural hindrance appears to be removed by the binding of the PH domain to PIP3. This membrane-dependent conformational change is supported by X-ray crystallography, NMR [26-28], in-cell fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy [29], and, more recently, chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry [18].

In the past years, chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry has emerged as a useful tool for probing protein conformation in physiologically relevant conditions [30]. The spatial distance information provided by the MS-determined cross-linking sites of amino acid residues has been shown to be valuable for the elucidation of protein structural changes associated with protein functions [31-32]. In an attempt to understand the molecular basis of Akt activation, we have recently developed a technique combining tandem mass spectrometry, lysine-specific chemical cross-linking [18], and proteolytic 18O digestion [33-35] to probe conformation of the full-length Akt for which the crystal structure is not yet available. We demonstrated that Akt undergoes dramatic interdomain conformational changes during its activation processes. Specifically, Akt- membrane interaction induced an open interdomain conformation where the PH and RD domains moved away from the kinase domain, allowing access of PDKs to T308 and S473 for Akt phosphorylation and activation.

In the present study, we applied the cross-linking and mass spectrometric approaches to probe the mechanism of Akt interactions with Akt inhibitors. The inhibitors used in this study are designed to interfere with Akt-membrane interaction and are supposedly promising anti-cancer drugs in terms of superior specificity and less toxicity compared to those known to compete with ATP binding [12]. By quantitative comparisons of Akt conformational changes using two interdomain cross-linked peptides, K30(PH)-K389(KD), and K284(KD)-K426(RD), we were able to suggest distinctively different molecular mechanisms by which these inhibitors function.

Experimental

Materials

Inactive Akt1 and ATP/Mg2+ cocktail were purchased from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions (Lake Placid, NY). Disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Wilmington DE). Sequencing grade modified trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Immobilized trypsin was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Akt inhibitors (PI analog, Cat # 124005 and TCL1 peptide, Cat #124013) and active PDK1 were purchased from EMD Chemical, Inc (Gibbstown, NJ). 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (18:0, 22:6-PS), 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (18:0, 22:6-PE), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (16:0, 18:1-PC), and 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (18:0, 20:4-PIP3) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Pure water was obtained from a Gemini high purity water system (West Berlin, NJ). H218O (99%), cyclohexane, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-p-cresol (BHT), and diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Quality Biological, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD).

Preparation of unilamellar vesicles

Unilamellar vesicles (1 mg/mL) composed of PC/PE/PS/PIP3 (19.8%/50%/30%/0.2%, which approximates a lipid composition in the inner leaflet of neuronal plasma membrane) were prepared according to the method reported previously [36]. Briefly, 1 mg/mL solutions of PE (18:0, 22:6), PC (16:0, 18:1), PS (18:0, 22:6), and PIP3 (18:0, 20:4) were mixed at the desired proportion. The mixture was dried under an N2 steam, re-dissolved in 2 mL cyclohexane containing 75 μM BHT (2,6-di-tert-butyl-p-cresol) and lyophilized for 1-2 h under vacuum. The sample was reconstituted in 1 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) in the presence of 50 μM DTPA (diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid). The lipid suspension was extruded 11 times through a 0.1 μm polycarbonate membrane (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY) using an Avanti mini-extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). All of the above procedures were carried out in an argon box except the drying and lyophilizing steps. An aliquot of the sample was analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS) to verify the final concentrations of lipid components [37].

Cross-Linking reaction, tryptic digestion and 18O labeling

Akt sample at 5 μM was dialyzed overnight against 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 50 mM NaCl at 4 °C to remove the primary amine-containing Tris-HCl buffer. Five μL of Akt was incubated with 30 μL liposomes in PBS containing 50 μM DTPA at 30 °C for 40 min in the presence or absence of 20 mM CaCl2. Alternatively, Akt was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with either PI analog inhibitor (25 μM), or TCL1 peptide inhibitor (25 and 50 μM), based on the optimal concentration range reported for the inhibitors [14,15], followed by additional incubation with 30 μL liposomes for 40 min at 30 °C. The mixture was incubated with a 50-molar excess of freshly prepared DSS in DMSO (1% final concentration of DMSO) at room temperature for 10 min. At this cross-linking condition inter-molecular cross-linked dimers or multimers were not observed according to SDS-PAGE analysis. The cross-linking reaction was quenched by adding 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 50 mM. The sample was digested with sequencing grade modified trypsin at 37 °C for 18 h using a trypsin to protein ratio of 1:20. After desalting, the sample was lyophilized to dryness.

16O/18O labeling was carried out similar to the method previously reported [38]. The dried peptides were reconstituted with 20 μL of acetonitrile and 100 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 in either regular H216O water or 99% H218O. One μL of 1 M CaCl2 and 5 μL of immobilized trypsin were added to the digests. The mixtures were continuously rotated in an incubator at 30° C for 30 h. After centrifuging the samples at 15,000 (g) for 5 min, supernatant was collected and acidified using TFA solution to pH 3.5. The samples were concentrated using a SpeedVac (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, NY) and desalted with C18 Ziptip (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) prior to mass spectrometric analysis.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis

One μl of peptide mixtures were mixed with 1 μl of matrix solution (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) and then spotted on a MALDI plate. Samples were allowed to air dry and analyzed by a 4700 MALDI-TOF/TOF Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) operated in reflector positive ion mode. The UV laser (Nd:YAG) was operated at 200 Hz with wavelength of 355 nm. For MS analysis, 1000 - 4000 m/z mass range was used, typically with 2000 shots per spectrum. A 1-keV collision energy was used in MS/MS acquisition for precursor ions of interest. Both MS and MS/MS data were acquired using the instrument default calibration. All acquired spectra were processed using 4000 Series Explore software (Applied Biosystems) in a default mode.

Nano-electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometric analysis

Desalted peptides were analyzed by a high resolution QSTAR pulsar Qq-TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Toronto, CA) equipped with a nano-electrospray ionization source. The ion source voltage was set to 1100 V in the positive ion mode. A full mass spectrum was acquired over an m/z range of 500-2000. Ions of interest were subjected to collision-induced dissociation (CID) using high purity nitrogen to obtain MS/MS data. Resolution greater than 8000 and mass accuracy with less than 30 ppm error were attained in both full MS and MS/MS modes. The reconstructed mass spectral data were generated using Analyst QS 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex).

Analysis of the cross-linked peptides

The cross-linked peptides were identified by comparing the mass spectrum obtained from DSS-modified sample with non-modified control, followed by MS/MS analysis to determine the cross-linked lysine residues. Protein Analysis Work Sheet (PAWS) was used to assign the mass values of tryptic peptides. MS/MS data for the cross-linked peptides were manually interpreted with the assistance of PAWS, Analyst QS 1.1 software and 18O labeling.

Results and discussion

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis of cross-linked peptides and stable isotope 18O labeling using immobilized trypsin

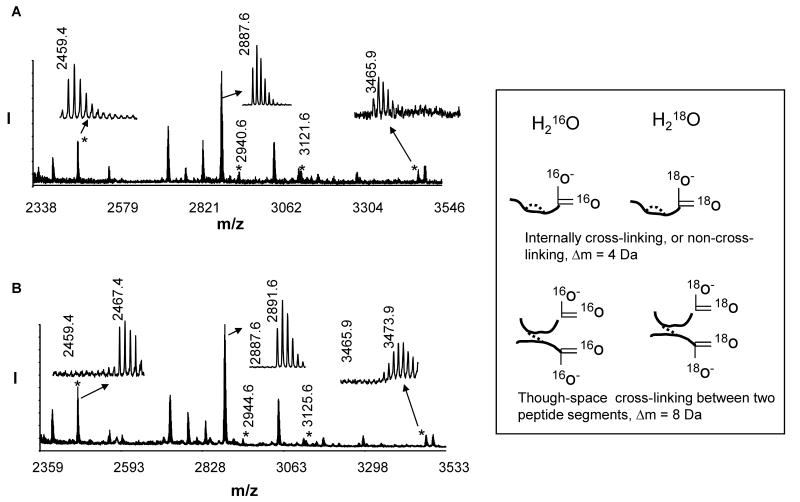

Using ESI MS/MS, we have previously identified seven intramolecular cross-linked lysine pairs in inactive Akt molecule, including K111-K112, K214-K284, K158-163, K30-K39, K377-K385, K30-K389 and K284-K426 [18]. The cross-linking results obtained by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS were in agreement with the previous ESI MS data with the exception of a cross-linked peptide with mass of 3623 Da (K214-K284). This cross-linking was detected by ESI but not MALDI, presumably due to discrepancy in the ionization efficiency. Fig. 1A represents the MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectra of the tryptic digests of inactive Akt samples with a mass range of 2300 – 3500 Da. The mass window was chosen to simplify the spectra because the peaks of interest are within this range. Four cross-linked peptides with m/z value of 2459.4, 2940.6, 3121.6 and 3465.9, representing the intramolecular cross-linking of K30(PH)-K389(KD), K30(PH)-K39(PH), K111(PH)-K112(PH), and K284(KD)-K426(RD), respectively, were observed in the DSS-modified sample whereas they were absent in the non-modified control (data not shown). Based on the distance constraints of 24 Å rendered by the cross-linking agent DSS, the presence of two interdomain cross-linked pairs, K30(PH)-K389(KD) and K284(KD)-K426(RD), represents the proximity of the PH and the regulatory domain to the central kinase domain. Quantitative monitoring of these two cross-linked peptides using 18O labeling can be used to probe the interdomain conformational changes of Akt [18].

Fig.1.

MALDI-TOF-TOF MS spectra of DSS-modified tryptic digests labeled with 16O (A) or 18O (B). Newly emerging cross-linked peptides are marked with asterisks. The MS data indicate a complete incorporation of 18O atoms. Inset, Though-space cross-linked peptides between two peptide segments display a distinct 8 Da shift when labeled with 18O.

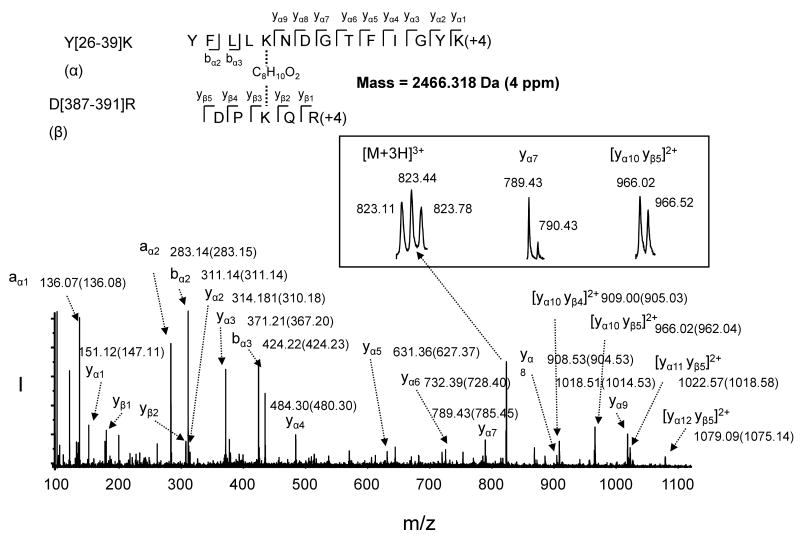

A key challenge in proteolytic 18O labeling for quantitative MS is to overcome the incomplete incorporation of 18O atoms into the C-terminal of lysine or arginine [33]. From our previous experience with the labeling procedure using protein digestion in 99% 18O water [18, 32], we have learned that removing salts and excess chemical reagents via dialysis is critical for full incorporation of 18O atoms, despite reduced protein recovery. The current study employed an alternative approach of labeling tryptic peptides using immobilized trpysin in 99% 18O water as described in the experimental section [37]. This post-digestion labeling procedure resulted in complete 18O incorporation, as shown in Fig. 1B. The non-cross-linked peptide increased by 4 Da (e.g. MH+ 2891.6 for T[87-111]K), as the case with the internal cross-linking within a peptide segment because a total of 2 18O atoms were incorporated into the single C-terminal. However, due to two C-termini from two different tryptic peptide segments (Fig. 1 inset), the m/z value of the interdomain cross-linked peaks shifted by 8 to 2467.4 and 3473.9 (Fig. 1B), respectively. The identity of the peaks was further confirmed by MS/MS analysis using the ESI mode which resulted in a better sequence coverage than MALDI. For example, the ESI MS/MS data obtained from the peptide with mass of 2466 Da (derived from triply charged ion of 823.1 m/z, Fig. 2 inset) confirmed the peptide was due to the cross-linking between K30 of Y[26-39]K] to K389 of D[387-391]R, with the C-terminal of K39 and R391 each labeled with two 18O atoms (Fig. 2). Although quantitative analysis was our purpose of using 18O labeling in the study, an additional benefit of the labeling was also clear in the sequence assignment especially from complicated MS/MS spectra of cross-linked peptides. As shown in Fig. 2, in comparison with MS/MS spectrum of the 16O counterpart (peak values are listed in the parentheses), an m/z shift of 4 in singly charged peaks indicated that they were y ions (e.g. m/z 789.43, inset) originating from one of the cross-linked peptides. Likewise an m/z increase of 4 in doubly charged peaks (e.g. m/z 966.02, inset) indicated they were y ions containing both C-termini from the cross-linked peptide segments. It is apparent that the peaks with an unchanged m/z value resulted from the cleavage from N- terminal such as b or a ions. These characteristics of 18O labeling in conjunction with MS/MS enabled us to unambiguously assign the cross-linking sites in the through-space cross-linked peptides.

Fig. 2.

ESI MS/MS analysis of the 18O labeled cross-linked peptide with mass of 2466 Da reconstituted from the triply charged ion of m/z 823.1. The sequence of the peptide was assigned with single letter abbreviation based on the fragment ions observed for the cross-linked peptide segments. N-terminal b ions and C-terminal y ions resulting from the amide bond cleavage are labeled. The MS/MS spectrum indicates that K30 of the peptide segment Y[26-39]]K (designated as α) linked to K389 of D[387-391]R (designated as β), via C8H10O2, the cross-linking bridge from DSS, with C-terminal of K39 and R391 labeled with 18O. 18O labeling facilitated the assignment of the fragment ions. The m/z values for the fragment ions are labeled (the m/z values obtained from 16O labeling are listed in the parentheses). Inset shows the charged state for the indicated ions.

Probing the inhibition of interdomain conformational changes due to disruption of Akt-membrane interaction by Ca2+

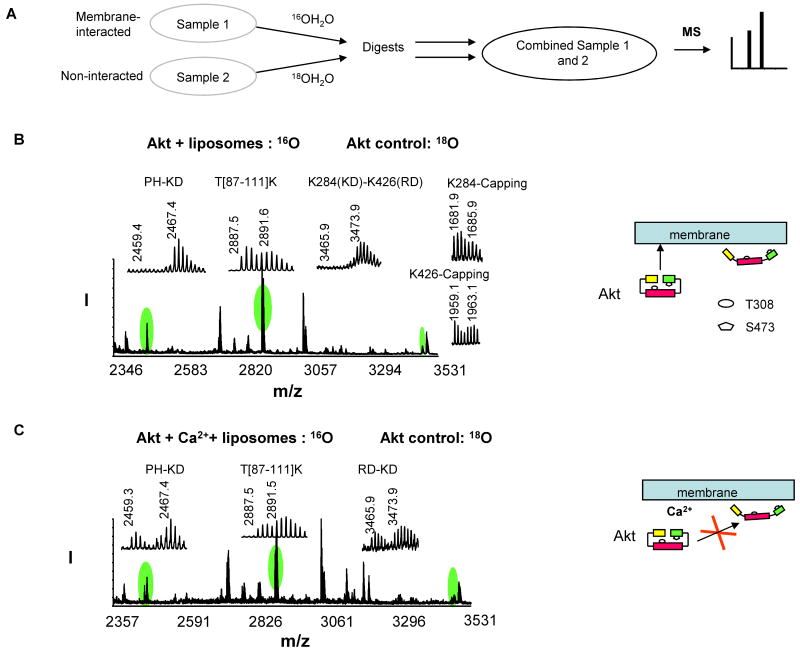

The mass spectrometric analysis of cross-linked peptides provides not only a tool to monitor conformational changes of Akt during activation [18] but also a strategy to investigate Akt-membrane and/or Akt-inhibitor interactions. An example is shown for the effect of calcium on membrane-induced Akt conformational changes and activation. The 18O labeling tryptic peptides from the non-membrane interacted control were mixed with 16O labeled digests from the liposome-interacted samples and subjected to MALDI analysis (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, the relative amount of the control and membrane-interacted samples was calculated by the average 16O/18O ratio of the isotopic pairs of the six non-cross-linked peptides, including C[77-86]R, Y[215-222]R, V[145-154]K, F[407-419]K, L[347-356]K, and T[87-111]K, using a formula (16O/18O ratio = I0/[I4-(M4/M0)I0]) which is a modified form of the previous equation [33] based on the complete exchange of 18O in our experiments. In the equation, I0 and I4 are the observed relative intensities for the monoisotopic peak for the peptide without 18O label and the peak with 4 Da higher mass, respectively; M0 and M4 are the theoretical relative intensities for the monoisotopic peak and the peak with 4 Da higher mass, respectively. The average ratio of 16O/18O from the six non-cross-linked peptides was found to be 1.05 ± 0.10 in this case as shown in Table 1. The peptide cross-linked at K30-K389 or K284-K426 digested in H216O was not detected (m/z 2459 or 3466) whereas their counterparts digested in H218O (2467 or 3474 Da) were detected, confirming the absence of the cross-linking of K30-K389 and K284-K426 in the membrane-interacted sample. The individual capping of the cross-linked lysine residues was observed even in the presence of the cross-linked peptides (e.g. K284- and K426-capping, Fig. 3B), presumably due to the fact that the cross-linking reaction as well as the hydrolysis of the unreacted end of the bifunctional cross-linker occurs rapidly. This could explain relatively minor changes observed for the monolinks despite the reduced crosslinked pairs in many experiments. Nevertheless, in extreme cases where the interdomian cross-linked peptides disappeared we observed a slight increase in the monolinks. Such example is shown in Fig. 3B where K284- and K426-capping increased by approximately 20% (Table 1) when K284-K426 cross-linking was lost upon the membrane interaction, suggesting that solvent accessibility to these lysine residues is similar after membrane interaction. As described previously [18], the absence of the interdomain cross-linking suggested that Akt-membrane interaction causes open interdomain conformations where the PH and RD domains unfold from the kinase domain to expose T308 and S473 for subsequent phosphorylation and Akt activation (Fig. 3B, schematic presentation). However, when Akt was incubated with the vesicles in the presence of 20 mM Ca2+, which is known to disrupt the surface charge of the membrane [39], the two interdomain cross-linked pairs were observed again in the mass spectrum (Fig. 3C) at an extent comparable to the non-interacted control as indicated by the 16O/18O ratio normalized to the average value from six non-modified peptides (Table 2). This result strongly suggested that the Akt-membrane interaction was indeed disrupted by Ca2+, preventing conformational changes of Akt to an open conformer.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of the interdomain cross-linked peptides upon Akt-membrane interaction. A, A quantitative analysis scheme. B-C, MALDI-TOF-TOF MS spectrum obtained from 16O-labeled membrane-interacted sample without (B) or with Ca2+ (C), mixed with 18O-labeled non-interacted control. The schematic presentation illustrates the interdomain conformational changes of Akt caused by membrane interaction in the absence or presence of Ca2+.

Table 1.

Quantitation of cross-linked peptides upon membrane interaction

| 16O labeled sample1 | Ratio | PH-KD | T[87-111]K | RD-KD | K284-cap | K426-cap | Average ratio2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akt + liposomes | 16O/18O (from Fig. 3B) | 0 | 1.12 | 0 | 1.32 | 1.30 | 10.5 ± 0.10 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 0 | 1.10 | 0 | 1.26 | 1.24 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 0 | 0.96 ± 0.10 | 0 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 1.19 ± 0.13 |

The 16O labeled sample was mixed with 18O labeled Akt control for MS analysis.

Average value for six non-modified peptides.

Normalized to the average value for six non-modified peptides.

Average normalized ratios from three measurements. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Table 2.

Quantitation of cross-linked peptides upon inhibitor and/or membrane interaction

| 16O labeled sample1 | Ratio | PH-KD | T[87-111]K | RD-KD | Average ratios2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akt + Ca2+ + liposomes | 16O/18O (from Fig. 3C) | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.67 ± 0.10 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.07 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | ||

| Akt + PI analog | 16O/18O (from Fig. 4A) | 0.49 | 1.04 | 0.48 | 1.04 ± 0.10 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.47 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 1.04 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | ||

| Akt + PI analog + liposomes | 16O/18O (from Fig. 4B) | 0.46 | 1.12 | 0.41 | 1.02 ± 0.09 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 0.45 | 1.10 | 0.40 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | ||

| Akt + TCL1 | 16O/18O (from Fig. 5A) | 1.20 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.08 ± 0.13 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 0.94 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | ||

| Akt + TCL1 + liposomes | 16O/18O (from Fig. 5B) | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.56 ± 0.06 |

| 16O/18O nor.3 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.45 | ||

| 16O/18O ave. (n=3)4 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | ||

The 16O labeled sample was mixed with 18O labeled Akt control for MS analysis.

Average value for six non-modified peptides.

Normalized to the average value for six non-modified peptides.

Average normalized ratios from three measurements. The data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

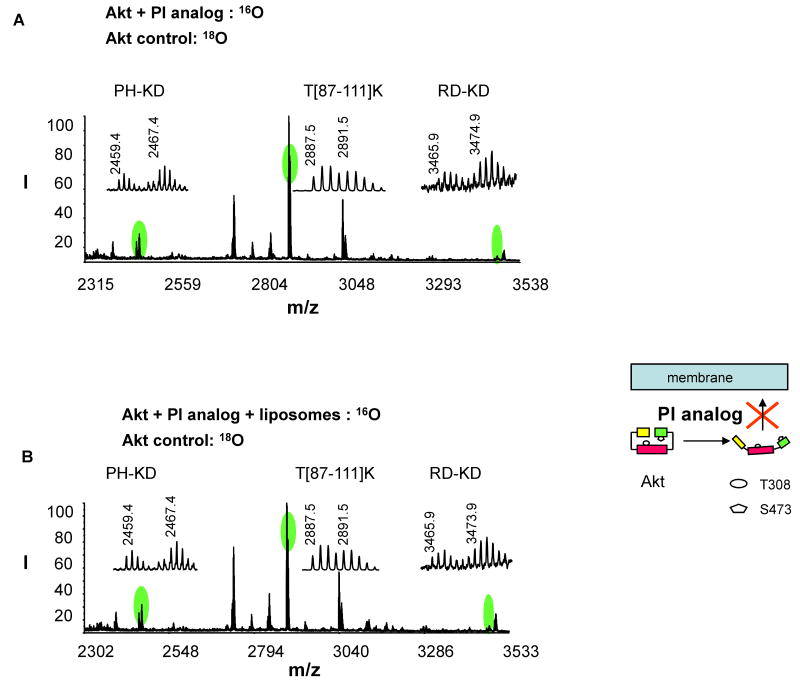

Akt conformational changes caused by interaction with a phosphatidylinositol (PI) analog

Fig. 4A shows the changes of the interdomain cross-linking after Akt interacted with an Akt inhibitor, a phosphatidylinositol (PI) analog. The sample was obtained by mixing 16O tryptic digests of the inhibitor-interacted sample with the 18O labeled digest of the non-interacted control. When Akt was interacted with the PI analog, both PH-KD and RD-KD cross-linking pairs decreased considerably compared to the 18O labeled control (normalized 16O/18O ratios were 0.53 and 0.49, respectively, Table 2), indicating that the PI analog bound to Akt and induced an open inter-domain conformation. The inhibitor is one of six 3-(hydroxymethyl)-bearing PI ether lipid analogues that have been shown to inhibit both PI3-K and Akt kinase activity in various cancer cell lines presumably by preventing PIP3 formation or interfering with Akt-PIP3 interaction [14]. Interestingly, among these analogues that differ in structural combinations of a modified carbonate group and the position of -CH2OH in the inositol head group, the PI analog used in this study is the most effective inhibitor for Akt but is the worst at inhibiting PIK3 kinase activity, although detailed mechanisms are not clear [14]. Our cross-linking results supported that this PI analogue caused Akt conformational changes as in the case with the membrane-interacted Akt (schematic presentation in Fig. 4), even before the membrane interaction, by binding to Akt. It is expected that the Akt-inhibitor interaction competes with the interaction of Akt with membrane PIP3, consequently preventing cytosolic Akt from translocating to the plasma membrane for the interdomain conformational changes for subsequent phosphorylation. This notion was supported by the fact that the extent of interdomain cross-linking observed after Akt-PI interaction remained similar even in the presence of liposomes (Fig. 4B and Table 2). This mechanism provided an explanation for the reported strong potency of the inhibitor for Akt activity in living cells, despite its minimal inhibitory activity against PI3 kinase.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative analysis of the interdomain cross-linked peptides upon Akt-inhibitor (PI analog) interaction. MALDI-TOF-TOF MS spectrum was obtained from 16O-labeled inhibitor-interacted sample without (A) or with liposomes (B), mixed with 18O-labeled non-interacted control. The schematic presentation illustrates the effect of the inhibitor on Akt interdomain conformation and membrane translocation.

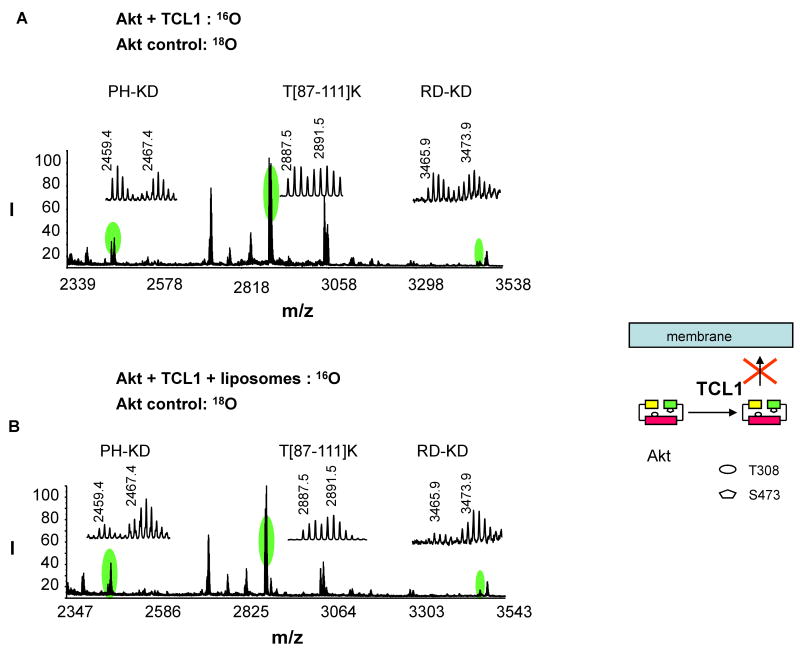

Effect of Akt inhibitor (proto-oncogene TCL1 peptide) on Akt-membrane interaction revealed by conformational changes

The interdomain cross-linking was analyzed after Akt was interacted with an inhibitor named TCL1 peptide, in comparison to non-interacted control (Fig. 5A). The inhibitor consists of 15 amino acids, which is equivalent to A[10-24]F of the βA strand of the proto-oncogene TCL1, an Akt-interacting protein. The 16O tryptic digests obtained from the inhibitor-interacted sample was mixed with the 18O labeled digest from the non-interacted control with a ratio of approximately 1:1. The intensity of the interdomain cross-linked pairs did not change significantly after Akt was incubated with the peptide inhibitor, as indicated in the normalized 16O/18O ratios (Table 2). The peptide is thought to bind to the PH domain of Akt, similar to the case with wild type TCL1. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies have suggested that the peptide induces a local conformational change in the variable loop 1 (VL1, residues 10-20) of the Akt PH domain [15], an important region for PIP3 binding [27]. Although the detailed local 3D structural changes could not be probed by the current cross-linking strategy, our data indicated that the peptide binding did not induce an open interdomain conformation. The peptide inhibitor has been shown to greatly impair the membrane translocation of the Akt PH domain and phosphorylation of T308 and S473 in 293 cells after stimulation with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [15]. This inhibition has been attributed to its ability to interfere with the interaction of Akt with membrane PIP3. Our cross-linking data shown in Fig. 5B was consistent with this view. When inactive Akt was incubated with liposomes in the presence of TCL1 peptide at 25 μM, the interdomain cross-linked peptides did not disappear, in contrast to the case where Akt was incubated with liposomes without inhibitors (Fig. 3B). The normalized 16O/18O ratios were 0.70 and 0.42 for the PH-KD and RD-KD cross-linked peptides, respectively (Table 2). The presence of these cross-linking pairs indicated that considerable proportions of both PH and RD domains remained folded even after membrane interaction, suggesting that conformational change to an open Akt conformer was impaired by the TCL1 inhibitor (Fig. 5). In the presence of TCL1 inhibitor, RD appeared to interact with membrane better than the PH domain, as around 60% of Akt population showed an open RD-KD conformation. A significant reduction of PIP3-PH interaction is expected based on the previous observation of the peptide inhibitor spanning the binding site of the PH domain [15]. As 25 μM of TCL1 partially prevented the conformational changes upon membrane interaction, we evaluated the effect of TCL1 at a higher concentration (50 μM). We observed a modest increase of the PH-KD and RD-KD cross-linking (16O/18O ratios were 0.80 ± 0.02 and 0.52 ± 0.05, respectively), suggesting a better inhibition of Akt open conformation with a higher dose of TCL1 peptide.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis of the interdomain cross-linked peptides upon Akt-inhibitor (TCL1 peptide) interaction with or without the presence of membrane. MALDI-TOF-TOF MS spectrum was obtained from 16O-labeled inhibitor-interacted sample without (A) or with liposmes (B), mixed with 18O-labeled non-interacted control. The schematic presentation illustrates the effect of the peptide inhibitor on Akt interdomain conformation and membrane translocation.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that Akt interdomain conformational changes provide a molecular mechanism for the Akt-membrane interaction which is a prerequisite step for Akt activation. We presented here a novel strategy to study the interaction between Akt and its inhibitors by probing the conformational changes of Akt, using chemical cross-linking and 18O labeling mass spectrometry. Our cross-linking strategy suggested two distinctive molecular interaction mechanisms involved in Akt inhibition. The Akt-PI analog caused conformational changes upon interaction with Akt even before membrane interaction, subsequently disabling Akt translocation to the membrane. In contrast, the TCL1 peptide interfered at the stage of Akt-membrane interaction, particularly impairing the unfolding of the PH domain. This novel approach should be potentially useful in facilitating drug discovery efforts for specific Akt inhibitors or anti-tumor agents based on the underlying molecular interaction mechanisms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brazil DP, Hemmings BA. Ten Years of Protein Kinase B Signalling: A Hard Akt to Follow. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. PKB/Akt: A Key Mediator of Cell Proliferation, Survival and Insulin Responses? J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2903–2910. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantley LC. The Phosphoinositide 3-kinase Pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu Haian, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Akt Phosphorylation of BAD Couples Survival Signals to the Cell-intrinsic Death Machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardone MH, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed JC. Regulation of Cell Death Protease Caspase-9 by Phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt Promotes Cell Survivial by Phosphorylating and Inhibiting a Forkhead Transcription Factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govindarajan B, Sligh JE, Vincent BJ, Li M, Canter JA, Nickoloff BJ, Rodenburg RJ, Smeitink JA, Oberley L, Zhang Y, Slingerland J, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD, Cohen C, Hilenski L, Griendling K, Martínez-Diez M, Cuezva JM, Jack L, Arbiser JL. Overexpression of Akt Converts Radial Growth Melanoma to Vertical Growth Melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:719–729. doi: 10.1172/JCI30102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson KM, Anderson NG. The Protein Kinase B/Akt Signalling Pathway in Human Malignancy. Cell Signal. 2002;14:381–395. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondapaka SB, Singh SS, Dasmahapatra GP, Sausville EA, Roy K, Perifosine K. A Novel Alkylphospholipid, Inhibits Protein Kinase B Activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1093–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crul M, Rosing H, de Klerk GJ, Dubbelman R, Traiser M, Reichert S, Knebel NG, Schellens JHM, Beijnen JH, ten Bokkel Huinink WW. Phase I and Pharmacological Study of Daily Oral Administration of Perifosine (D-21266) in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan ZQ, Sun M, Feldman RI, Wang G, Ma X, Jiang C, Coppola D, Nicosia SV, Cheng JQ. Frequent Activation of AKT2 and Induction of Apoptosis by Inhibition of Phosphoinositide-3-OH Kinase/Akt Pathway in Human Ovarian Cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:2324–2330. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaravadi A, Thompson CB. The Survival Kinases Akt and Pim as Potential Pharmacological Targets. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2618–2624. doi: 10.1172/JCI26273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett SF, Defeo-Jones D, Fu S, Hancock PJ, Haskell KM, Jones RE, Kahana JA, Kral AM, Leander K, Lee LL, Malinowski J, McAVOY EM, Nahas DD, Robinson RG, Hans E, Huber HE. Identification and Characterization of Pleckstrin-homology-domain-dependent and Isoenzyme-specific Akt Inhibitors. Biochem J. 2005;385:399–408. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Qiao L, Wang S, Rong S, Meuillet EJ, Berggren M, Gallegos A, Powis G, Kozikowski AP. 3-(Hydroxymethyl)-Bearing Phosphatidylinositol Ether Lipid Analogues and Carbonate Surrogates Block PI3-K, Akt, and Cancer Cell Growth. J Med Chem. 2003;43:3045–3051. doi: 10.1021/jm000117y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiromura M, Okada F, Obata T, Auguin D, Shibata T, Roumestand C, Noguchi M. Inhibition of Akt Kinase Activity by a Peptide Spanning the βA Strand of the Proto-oncogene TCL1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53407–53418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alessi DR, Cohen P. Mechanism of Activation and Function of Protein Kinase B. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Cron P, Thompson V, Good VM, Hess D, Hemmings BA, Barford D. Molecular Mechanism for the Regulation of Protein Kinase B/Akt by Hydrophobic Motif Phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1227–1240. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang BX, Kim HY. Interdomain Conformational Changes in Akt Activation Revealed by Chemical Cross-linking and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1045–1053. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600026-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calleja V, Alcor D, Laguerre M, Park J, Vojnovic B, Hemmings BA, Downward J, Parker PJ, Larijani B. Intramolecular and Intermolecular Interactions of Protein Kinase B Define Its Activation In Vivo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e95. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellacosa A, Testa JR, Staal SP, Tsichlis PN. A Retroviral Oncogene, Akt, Encoding a Serine-threonine Kinase Containing a SH2-like Region. Science. 1991;254:274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas CC, Deak M, Alessi DR, van Aalten DMF. High-resolution Structure of the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of Protein Kinase B/Akt Bound to Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokoe D, Stephens LR, Copeland T, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Painter GF, Holmes AB, McCormick F, Hawkins PT. Dual Role of Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the Activation of Protein Kinase B. Science. 1997;277:567–570. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andjelkovic M, Alessi DR, Meier R, Fermandez A, Lamb NJC, Frech M, Cron P, Cohen P, Lucocq JM, Hemmings BA. Role of Translocation in the Activation and Function of Protein Kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31515–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Ahmed NN, Datta K, Malstrom S, Stpkoe D, McCormick F, Feng JN, Tsichlis P. Akt Activation by Growth Factors Is A Multiple-Step Process: the Role of the PH domain. Oncogene. 1998;17:313–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watton SJ, Downward J. Akt/PKB Localisation and 3′ Phosphoinositide Generation at Sites of Epithelial Cell–matrix and Cell–cell Interaction. Curr Biol. 1999;9:433–436. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milburn CC, Deak M, Kelly SM, Price SM, Alessi DR, van Aalten DMF. Binding of Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate to the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of Protein Kinase B Induces A Conformational Change. Biochem J. 2003;375:531–538. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Cron P, Good VM, Thompson V, Hemmings BA, Barford D. Crystal Structure of An Activated Akt/protein Kinase B Ternary Complex with GSK3-peptide and AMP-PNP. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;12:940–944. doi: 10.1038/nsb870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auguin D, Barthe P, Auge-Senegas M, Stern M, Noguchi M, Roumestand C. Solution Structure and Backbone Dynamics of the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of the Human Protein Kinase B (PKB/Akt): Interaction with Inositol Phosphates. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:137–155. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000013836.62154.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calleja V, Ameer-beg SM, Vojnovic B, Woscholski R, Downward J, Larijani B. Monitoring Conformational Changes of Proteins in cells by Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy. Biochem J. 2003;372:33–40. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young MM, Tang N, Hempel JC, Oshiro CM, Taylor EW, Kuntz ID, Gibson BW, Dollinger G. High Throughput Protein Fold Identification by Using Experimental Constraints Derived from Intramolecular Cross-links and Mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5802–5806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090099097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinz A. Chemical Cross-linking and Mass Spectrometry for Mapping Three-dimensional Structures of Proteins and Protein Complexes. J Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/jms.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang BX, Dass C, Kim HY. Probing Three-dimensional Structure of Bovine Serum Albumin by Chemical Cross-linking and Mass Spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1237–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao X, Freas A, Ramirez J, Demirev PA, Fenselau C. Proteolytic 18O labeling for Comparative Proteomics: Model Studies with Two Serotypes of Adenovirus. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2836–2842. doi: 10.1021/ac001404c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Back JW, Notenboom V, Koning LJ, Muijsers AO, Sixma TK, Koster CG, Jong L. Identification of Cross-linked Peptides for Protein Interaction Studies Using Mass Spectrometry and 18O labeling. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4417–4422. doi: 10.1021/ac0257492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang BX, Dass C, Kim HY. Probing Conformational Changes of Human Serum Albumin Due to Unsaturated Fatty Acid Binding by Chemical Cross-linking and Mass Spectrometry. Biochem J. 2005;387:695–702. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HY, Bigelow J, Kevala JH. Substrate Preference in Phosphatidylserine Biosynthesis for Docosahexaenoic Acid Containing Species. Biochemistry. 2001;43:1030–1036. doi: 10.1021/bi035197x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen Z, Kim HY. Alterations in Hippocampal Phospholipid Profile by Prenatal Exposure to Ethanol. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1368–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu T, Qian WJ, Strittmatter EF, Camp DG, Anderson GA, Thrall BD, Smith RD. High-Throughput Comparative Proteome Analysis Using a Quantitative Cysteinyl-peptide Enrichment Technology. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5345–5353. doi: 10.1021/ac049485q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez GA, Daniotti JL. Electrical Properties of Plasma Membrane Modulate Subcellular Distribution of K-Ras. FEBS J. 2007;274:2210–2228. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]