Abstract

In this paper, we report findings from a recent survey of international migration from China's Fujian province to the United States. We take advantage of the ethnosurvey approach as used in the Mexican Migration Project. Surveys were done in migrant-sending communities in China as well as in destination communities of New York City. We derive hypotheses from two strands of recent studies-the international migration literature and the market transition debate. Our results are in general consistent with hypotheses derived from cumulative causation of migration. However, because of the geographical location of China as compared to Mexico, there are some differences between the two countries in terms of particular migration patterns to the United States. As expected, at the community level, migration prevalence ratio (measuring migration networks) increases the propensity of migration for other members in the community. In contrast, having a household member migrated previously does not increase the propensity of migration of other household members until debt for previous migration is paid off. Our research clearly demonstrates the value of bringing the case of China into the comparative study of international migration. With respect to market transition theory, we find that political power continues to be an important factor in the order of social stratification in the coastal Fujian province.

Introduction

China has a long history of emigration. This legacy has left marks in major parts of the world, from Southeast Asia, Latin America, to North America (Poston et al., 1994). This long history of emigration came to a nearly standstill during the first three decades (from 1949 to roughly late 1970s) of the People's Republic. 1 However, since China's transition to a market-oriented economy in the late 1970s, the historical legacy of emigration began to revive. One important stream of emigrants from China is characterized by emigration through clandestine channels. The recent surge in emigration from China's Fujian province (see Map 1), located in the southeastern corner of the coastal regions, typifies this kind of emigration. Demographically speaking, this flow of migration is important because by the mid-1990s, Fujian province had become the top immigrant-sending province in China, overtaking China's well-known province of emigration Guangdong province by a large margin (Liang, 2001).

Map 1.

Location of Fujian Province in China

This paper endeavors to examine emigration from China's Fujian province. Much of the recent theoretical and empirical studies on international migration are based on the case of Mexico to U.S. migration (Fussell and Massey, 2004; Massey, 1987; and Massey et al., 1994a). The recent rise of international migration from China provides a rare opportunity to see whether some of the findings and arguments hold true for the case of China. There are reasons that the Chinese case may not duplicate exactly what we observed for Mexican migration to the United States. First, of course, is the matter of geography. Mexico is unique in terms of geographic location, sharing a long border with the United States. China, on the other hand, is far away from the United States, as the quickest flight from China to the United States (the east coast) takes more than 13 hours. This geographic distance is likely to have implications for patterns of migration, mechanisms of migration networks, and remittance behavior. The second difference lies in the political institutions of the two countries. While Mexico is a full-fledged market economy, China was for many years a socialist society. It was only in the late 1970s that China began to move toward a market-oriented economy. As a transitional society, China may present some patterns of migration that are not obvious in the case of Mexico.

In this paper, we use newly collected data from China's Fujian province and the United States to study international migration from that province to the United States. Our paper is informed and motivated by theoretical and empirical insights from recent literature on international migration (in particular the idea of cumulative causation) and the market transition debate. We begin by elaborating on ideas from these two strands of thoughts, and then derive and refine relevant hypotheses. Discussion of the research design and methods will follow. We argue that our research contributes to both lines of research. Although results from this paper are largely consistent with the migration network literature, our paper calls attention to the importance of geographic differences across migrant-sending countries in generating different levels of migration network effects. Further, we argue that for migration theories to be more effective, forms and implications of political economy (i.e. market economy vs. transitional economy) in the migrant-sending communities should be taken into account. Along this line of reasoning, our paper engages the recent debate on market transition by examining how cadres behave and fare in the process of international migration.

Background

This paper draws on insights from two theoretical perspectives: one is on international migration and the other on the market transition debate. Below we summarize the main ideas from each of them. In doing so, we do not intend to mechanically apply theoretical ideas to the Chinese case. Rather we use these perspectives as guidelines as we generate testable hypotheses to explain patterns of international migration.

Migration Networks and Cumulative Causation of Migration

The thesis of cumulative causation has recently been used to explain the perpetuation of Mexican migration to the United States. As Massey (1999) stated, “causation is cumulative in the sense that each act of migration alters the social context within which subsequent migration decisions are made, typically in ways that make additional movement more likely (p. 45).” Among the mechanisms that are identified are expansion of migration networks, distribution of income, distribution of land, organization of agriculture, culture, and regional distribution of human capital. A significant amount of research efforts have been devoted to demonstrating the role of expansion of migration networks on the probability and perpetuation of migration. The idea of cumulative causation has been tested extensively by Massey and his colleagues over the past two decades or so (Fussell and Massey, 2004; Massey et al., 1994b, Massey and Espinosa, 1997; Palloni et al., 2001).

A central idea underlying many of the studies by Massey and his colleagues is the powerful role played by migration networks that link migrants in destinations and potential migrants in migrant-sending communities. The role of migration networks in the process of migration is often manifested in the form of having a family member who is a migrant and/or having a friend from the same community who is a migrant. These networks reduce the costs of migration by providing aspiring migrants with information about the migration process and about job availability and housing in the destinations. According to Fussell and Massey (2004), “other things being equal, people who come from communities from which migration is prevalent are more likely to migrate than people who come from places from which migration is rare (P. 152).” What is powerful about this process is the tendency for migration to alter community structures in such ways that promote additional migration, thus leading to the logic of cumulative causation of migration.

We argue that the idea of cumulative causation of migration is very useful in explaining patterns of emigration from China's Fujian province. Two aspects of the cumulative causation argument are particularly relevant in the case of emigration from Fujian province. First is the importance of networks. The idea of networks is not a new concept in the Chinese context. Bian (1997), for example, used the networks (guanxi) approach to study job search and emphasized the importance of strong ties (instead of weak ties) in job searches in China. Likewise, in a study of rural industrialization, Peng (2004) argues that kinship networks affect economic growth via enforcing informal institutions.

In these studies by Bian and Peng, the network connection is conceived to be among acquaintances, friends, and family/kin members; in migration studies, we pay more attention to networks formed through the web of family members, friends, and people with shared community of origin (tongxiang). As a kind of social capital, this migration network has the feature of enforceable trust (Portes and Sensenbrenner, 1993). This is important because international migration from Fujian to the United States is often orchestrated by a broker (smuggler) that involves some degree of danger and uncertainty. Aside from the benefits of reducing the cost and increasing the benefits of migration, this migration network reinforces trust among all players in this process. 2

The second aspect of the cumulative causation theory that is closely related to the case of Fujian is the impact of migration on the migrant-sending communities. As Massey (1999) argues, “as migration grows in prevalence within a community or nation, it changes values and cultural perceptions in ways that increase the probability of future migration (p.46).” At the community level, over time, as information about jobs and lifestyles in destination countries becomes more diffused, migration becomes a common household strategy for economic advancement. Like the case of Mexico, for young people, migration becomes a “rite of passage“ (Massey, 1999). Take the case of Mr. Wang, for example, whom we interviewed in New York City. Wang said “as a young man in the village, if you do not want to migrate to the United States, you do not deserve to be a man and will not have any respect (hui rang ren qiao bu qi).” In Fujian, such changes at the community level are operated through three main mechanisms. One is the fancy houses built by migrant households. Visitors to these migrant-sending communities are often stunned by the luxury houses that were built with remittances. Sometimes the houses are built for consumption, but more importantly these houses have a broader symbolic meaning that these migrants “have made it” abroad. The second mechanism is the contribution to the welfare of the migrant-sending communities. The most popular way to contribute to the community is to donate money to establish a school, a cultural center, a senior citizen center, or to build local roads. Often the names of theses donors are inscribed on a board along with the amount of money contributed. This significantly elevates the status of these migrant households in these communities. The third mechanism is the reconstruction of ancestral halls (citang). Households or clans who have reconstructed ancestral halls with elaborate Chinese calligraphy and paintings often earn high respect and prestige in the migrant-sending communities.

In sum, the literature on international migration would lead us to the following two straightforward hypotheses. One is that individuals with family members already abroad are more likely to migrate than others. Second, individuals who are from communities with high levels of migration prevalence are more likely to migrate than individuals who are from communities where migration is relatively rare. However, in light of the special circumstances involving emigration from Fujian, we need to make some modifications to these “standard” hypotheses. As we noted earlier, one major difference between China and Mexico in the context of migration to the United States is the geography, namely the distance from China to the U.S. is much longer than the case of Mexico. The implication is that the cost will be much higher in the case of China than Mexico. Results from our survey suggest the highest amount paid by migrants is about $67,000 in the early 2000s. What this means is that once a household sends a migrant to the U.S., it would be very difficult to send another one immediately thereafter, simply because the cost is going to be too high for most households. Until the household pays off the smuggling fee, the household will not be likely to send another family member to the U.S. This suggests that having a U.S. migrant from the household does not necessarily increase the chances of U.S. migration for another member immediately. But over time, the family migration network effect will manifest itself.

Market Transition Debate and Emigration from China

The recent rise in international migration from China's Fujian province is clearly linked to China's transition to a market oriented economy since the late 1970s. Here we discuss some recent studies that examine how market transition changes the order of social stratification in China and elucidate its relevance for the study of international migration. In fact, Fujian province is especially relevant to the market transition debate because Victor Nee (1989) initiated the debate on the consequences of China's market transition based on a survey that he conducted in Fujian province in the mid 1980s. In a series of papers, Nee outlined a theory that deals with formerly central planned economies that are now in the process of moving to a market-oriented economy (Nee, 1989, 1991, 1996). Nee's theory has two central elements: 1) with the emergence of a market, central distributors will lose power and direct producers will have more discretion over the terms of exchanges of goods and services; (2) there are greater incentives for individual effort in market transactions than in socialist economies and a market will reward productivity and credentials instead of political loyalty. Nee has tested his ideas using data from rural Fujian by examining self-employment and entrepreneurship for individuals.

There have been many studies testing Nee's theory in the context of urban China, but the results are inconclusive (Bian and Logan, 1996; Xie and Hannum, 1996; Zhou, 2000). Several recent studies focus on rural China (Guang and Zheng, 2005; Parish et al., 1995; Walder, 2002a; Walder 2002b). These studies in rural China examined whether positional power (as measured by rural cadre status) lost favor in the 1990s, as Nee's theory would imply. Walder's studies (2002a and 2002b) suggest that rural cadre households continue to be advantaged in household income. In the context of internal migration in China, Guang and Zheng's research (2005) echoes the spirit from Walder's studies that marketization does not take away the advantage of traditional power. In contrast, using the case of rural China in the early 1990s, Parish et al. (1995) found that the role of political power worked differently in different regions. Namely while in less developed regions, political connections improve one's chance of obtaining non-farm employment, they do not matter in well-developed regions. They argue this is possible because of the abundant supply of non-farm employment opportunities in well-developed regions.

In sum, studies in rural China point out the continuing importance of rural cadre advantage but less so in well developed regions. To the extent that international migration often leads to socio-economic advancement for these immigrants, we will how cadre status is linked to this process. We explore this issue in two ways. One is to investigate the extent to which people with positional power (such as villager cadres) are likely to migrate internationally. Second, we are interested in examining whether aspiring migrants from households with rural cadres will enjoy any advantage in the process of migration. Although international migration to the United States can be financially rewarding in the long run, it is not risk free. This is especially the case for undocumented migrants from Fujian. Some of the most notorious ill-fated trips have been widely reported by the mass media such as the 1993 Golden Venture trip and the tragic death of 58 migrants in a tomato truck in Dover of England in 2000 (Rosenthal, 2000). Any calculation of risks and benefits must be placed in the context of the individual's position in the migrant-sending community. Officially, the main role of village leaders is to implement the policies from the central government. In these migrant-sending villages, village cadres are responsible for many important decisions. For example, when donations from abroad come to the village, village leaders are responsible for making sure the money is appropriately spent as the donors intended. Village cadres (such as the village head (cunzhang or cun zhuren) and the party secretary (shuji) often enjoy some fixed amount of stipend in these Fujian migrant villages (Lu, 2002, p.173). There are other benefits as well. Our fieldwork in migration-sending villages informs us that village leaders are often paid handsome amounts of money from people who plan to get married or from people whose family just lost loved ones, to make sure the wedding ceremony or funeral proceedings run smoothly. Moreover, in these migrant villages, migrants abroad often require some documents (such as a birth certificate (chusheng zheng) or a non-marital status certificate (weihun zheng)). Village leaders are often given some money or gift to facilitate the process of getting the required documents in a timely manner.

Our fieldwork in migrant-sending villages has also uncovered other financial gains, which are likely to be related to corruption, that village leaders may derive from their positional power. We share some examples here. In the winter of 2004, during one of the post-survey visits to migrant-sending villages, we encountered a villager Mr. Lin who had major grievances against village cadres. Several years ago, the village was planning to build a cultural center for performances or big local gatherings, and immigrants in the U.S. donated 4.7 million Yuan (RMB) for this purpose. Lin said that the Culture Center only cost 4 million Yuan (RMB) and alleged that the remaining 700,000 Yuan (RMB) all went to village cadres’ pockets.3 Another woman whose husband went to the United States some years ago also complained about village cadres’ corruption. She said when she got married, the village cadre who was responsible for family planning requested that the couple leave 20,000 Yuan (RMB) in the village office so that if they violated the rule of one child policy, the money would be used as penalty/fines for the violation. After her husband went to the U.S., she went to talk to the village cadres, saying that now her husband is in the U.S., there is no way she can violate the one-child policy and asked them to return the deposit of 20,000 Yuan (RMB). The reply was that it was the previous village cadre who took the money, which is no where to be found now. Another villager told us a story about internal migrants from Sichuan who were affected by the Three Gorges Project. Some of the residents near Three Gorges Project in Sichuan province were re-settled in migrant-sending villages in Fujian province and the central government compensated local villages for their work (building houses for re-settled migrants etc). He said it happened often that fellow villagers received little money and as a matter of fact most of the resettlement money from the central government was taken by cadres at different levels (town or village).

In light of these advantages bestowed to village leaders and potential gains from corruption, we do not expect that village cadres themselves are more eager to migrate internationally than others. However, individuals from households with village cadres are more likely to enjoy the advantages of international migration. Village cadres are often the first ones to know the information about any opportunities of going abroad. As the process of migration goes, it often involves many players: the boss of smuggling organization (who rarely shows up in local villages), the recruiters who go to villages to recruit potential migrants, and the potential migrants. In order to recruit migrants for a particular planned trip abroad, recruiters often need to get formal or informal permission from village leaders. This gives the village cadres a special advantage if it is perceived as a good opportunity for one of their household members. Moreover, because of the village cadres’ role in providing crucial documents for going abroad (such as documents required for obtaining passports), recruiters have a lot of favors to ask of village cadres. Thus, village cadres are well positioned to bargain with recruiters regarding the fees for sending migrants abroad.4 The above discussion leads to two additional hypotheses: (1) individuals from households with village cadres are more likely to migrate than others; (2) individuals from households with village cadres are likely to pay a lower fee than those from households without village cadres.

The case of Emigration from Fujian, China

Before we present research design and methods, some discussion of the social context of Fujian province is in order. Fujian province is located in the southeastern coast of China, across the Taiwan Strait (see Map 1). The 2000 Chinese population census shows that Fujian had a population of 34 million (NBS, 2002). Fujian has a long legacy of emigration, especially to Southeast Asian countries historically. However, the recent big wave of emigration did not start until the mid-1980s. We focus on Fujian province for our empirical studies for several reasons. First, emigration from China's Fujian province has increased significantly, and in fact it has become the top international migrant-sending province in China (Liang, 2001). Much of this emigration is clandestine in nature and is difficult to study through national surveys or censuses. The journeys of Fujian migrants also caught the attention of the mass media across the globe. Some of the migration journeys ended in tragedy (such as the ill-fated Golden Venture trip in 1993 and the death of 58 migrants in Dover, England in 2000). As recent as 2005, Fujianese migrants were caught in the fight in Iraq and were taken as hostages by mistake and later released (Wong, 2005; World Journal, 2005). Media sensation is of course no equivalent of systematic analysis; clearly more systematic social science analysis of causes and consequences of emigration from Fujian is needed.

The increase of emigration from Fujian province can easily be detected from the destination communities especially in New York City. The injection of new blood has had a major political and economic impact on the traditional Chinatown in New York. In New York City alone, there are over 40 Fujianese-led immigrant organizations based in Chinatown. In some sense, to study Chinese immigrants in the United States these days, one cannot ignore the new immigrants from Fujian.

According to the research literature on international migration, much of the recent efforts were on Mexican migration to the United States. As Massey et al. (1994a) stated more than a decade ago, “far too much research is centered on Mexico, which because of its unique relationship with the United States may be unrepresentative of broader patterns and trends...More attention needs to be devoted to other prominent sending countries, such as the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, El Salvador, Korea, and China (p.739).” Since then, there have been at least four scholarly books published on the study of emigration from Fujian. Based on in-depth interviews with 300 immigrants who were residing in New York City, Ko-lin Chin's study (1999) provided insights into the migration process and main channels of clandestine immigration to the United States. Also focusing on New York City, Kwong's work (1997) pointed to the demand side of the story and carefully documented the working conditions of Fujianese immigrants in New York City. Pieke et al.'s study (2004) gives us an important comparative perspective by looking at the case of Fujianese immigrants in Europe through the lens of globalization. Finally, the work by Guest (2003) shows the importance of religion in the lives of many Fujianese immigrants. One of the common characteristics of these books is that they focus much more on the destination countries than the migrant-sending communities. Another feature of these studies is that their data are often not based on representative samples of migrant-sending communities, thus making it difficult to make generalizations concerning the patterns of international migration. Our study draws a representative sample from migrant-sending communities and the sample in China is matched by another sample of migrants in New York who are from theses migrant-sending communities. This design matches closely the design by Massey and Durand for their Mexican Migration Project (MMP). Thus, our data are more appropriate for theory-testing in comparative analysis of international migration.

Data and Methods

This project is modeled on the successful experiences of MMP and the Latin American Migration Project (LAMP) directed by Douglas Massey and Jorge Durand. We adopted the ethnosurvey approach used in the MMP and LAMP (Massey, 1987). From February to June 2002, we were engaged in designing three questionnaires to be used in the ethnosurvey: a household questionnaire used in China, a household questionnaire used in the United States, and a community-level questionnaire for migrant-sending communities in China. We used the questionnaires for MMP and LAMP as a model and naturally modified the questionnaires to take into account the Chinese context. The household-level questionnaire contains basic information on the socio-demographic characteristics of each member of the household (including those who are abroad), and basic information on the internal and international migration history for all household members. Because of the importance of religion, as illustrated from the work of Guest (2003), we include information on religion for each person. For household heads and spouses, we gathered marriage history, fertility history, labor history, and consumption patterns. At the household level, we have information on remittances in the year of the survey and cumulative amount of remittances, business formation, land ownership and other property ownership, and housing conditions and tenure status.

We made some modifications to the questionnaire used in the MMP. For example, unlike the case of Mexico, we included questionnaire items on cadre status (ever been a cadre and year of acquiring that position) in order to test our hypotheses derived from the market transition theory.5 We also made another modification in gathering information on migration trip characteristics. Because undocumented migration is still a relatively sensitive topic in migrant-sending communities in China, we decided to ask more detailed questions on the actual migration trip for the U.S. sample, but not for the Fujian sample. Thus, for the U.S. sample, we asked about the date of travel/migration, duration of the trip, number and names of each country stayed in on the way to the U.S., smuggling fees paid, knowledge of snakehead, and number of people on the trip. There is another reason for asking these detailed questions on trip characteristics for the U.S. sample. Because of the low rate of return migration, more often than not, we interviewed household members who remain in China (not the immigrants themselves) in the survey. Household members usually know the basic information about their migrant members, but not detailed information about the migration trip itself. Thus, we believe our strategy is likely to increase the quality of data on trip characteristics. Finally, our sampling strategy is somewhat different from the case of MMP. Because of the low rate of return migration, we have increased the sample size of immigrants in the United States (more discussion on this later).

Our community (at the village level) questionnaire covers a wide spectrum of information: demographic background (such as population figures for major census years, immigration history), agriculture sown, industrial infrastructure, educational infrastructure, public services, financial infrastructure, transportation infrastructure, and medical infrastructure.

After some modifications, we finalized the questionnaires in late summer 2002 . Within northeastern Fujian province, we selected 8 towns that are known to send large numbers of migrants to the United States, the New York City region in particular. In choosing these particular towns for our survey, we first interviewed people with some major Fujianese immigrant organizations in New York City.6 The idea was to find out these towns that Fujianese migrants in New York City came from. This would ensure that the surveys in China would identify reasonable number of international migrants. Similar to the design of MMP, for each town, we have a target sample of 200 households. A stratified random sample is drawn from each town. In rural China, a town is composed of villages. For each chosen town, four villages were selected using systematic sampling scheme. Within each village, systematic sampling method was used to select 50 households. The non-response rate was around 5−15% depending on the communities surveyed. This ultimately yielded a sample of about 1312 households in the eastern part of Fujian. The survey team conducted the survey during October 2002-March 2003. For each household sampled, we interviewed one member of the household (either household head or spouse or migrant father). One issue with survey in Fujian is that in most cases, due to low rate of return migration, we interviewed family members who remain in the community but not migrants themselves. We believe the quality of data on migration is satisfactory. One reason is that international migration is a big event in the household, so that household members can remember and accurately report basic information on migration: timing, cost, and amount of remittances.7 In some cases, migration of adult children is arranged by parents who of course will remember information on migration of their children. In addition, we have performed systematic comparison between our data with other previous studies (such as studies that used China national survey data and other surveys (i.e. Chin (1999) and Liang (2001), the basic patterns of migration are very similar.

This sample in Fujian province is supplemented by a non-random sample of immigrants in New York City who are from these eight towns. For each of the eight towns, we interviewed about 25−40 immigrants in New York City who are from that town. Our sample size of immigrants in the destination communities is larger than what Massey and Durand have in their MMP. The main reason is that in the Chinese case, return migration is much more difficult than in the case of Mexico, thus yielding a much smaller proportion of the Fujian sample being immigrants themselves than the Mexican counterpart. 8 The fieldwork in New York City was conducted in the months of June-August 2003. Following Massey (1987), the sample in New York City was drawn using a snow-ball sampling strategy.

The survey implementation in China was carried out by a survey team from Xiamen University which was supervised by one of our collaborators in China. The team members consisted of graduate students and junior faculty members at School of Southeastern Asian Studies at Xiamen University. The School has a long tradition of research and fieldwork experience in migrant-sending communities in Fujian province. Prior to the survey, we conducted systematic training for the survey team in terms of objectives of the project, explanations of questionnaire items, quality control procedures, and human subject issues. Data entry was performed by graduate students at Xiamen University. This paper mainly uses data from the survey conducted in Fujian province. Survey implementation in New York City was carried out by graduate students from Queens College of the City University of New York under the supervision of the senior author of this paper. The fieldwork was greatly facilitated by staff from the Fukien American Association located on East Broadway in Manhattan. They helped us with recruiting immigrants for interviews as well as providing logistical support.

To test our hypotheses specified in the earlier sections, we created event history-type data. There are several advantages with the event history analysis method. One is that we can make clear causal inferences because timing order of events can be clearly specified. Second, time-varying covariates can be incorporated so that more precise information at different time points can be used to make predictions about individual behavior. Third, the event history method can handle censoring issues so that no information on individuals who have not experienced the event (migration) will be wasted (Allison, 1984; 1995; Yamaguchi, 1991).

The first set of models is to estimate the probability of making the first international migration trip using the event history analysis technique. To conduct the event history analysis of international migration, for each household we randomly select one person who is 18 years old or above. For these selected individuals from all households, for each year since age 15, we record migration events along with individual and household characteristics in that year. To test the cumulative causation theory, following Massey et al. (1994b), we create a migration prevalence ratio variable measured at the village level. These ratios are calculated using every respondent's year of birth and the date of his or her first U.S. trip. The denominator of the ratio is the number of people 15 years old or older alive in a given year, and the numerator is the number of such people who have ever been to the United States up to that year.

The second set of models is to estimate the trip cost (smuggling fees) among individuals who have made the first migration trip to the United States. This information on trip cost was asked differently in the New York City region and in China. For respondents in New York City, since trip cost is not as sensitive as in China, we asked about the exact amount of cost for coming to the United States. In migrant-sending communities in China, undocumented migration and smuggling fees are still somewhat sensitive issues for people to talk about openly. To reduce the level of potential threat, we decided to use a set of categories rather than the actual amount of money paid in Chinese currency Yuan (RMB). This classification scheme certainly loses some accuracy for the sake of high response rate in the immigrant-sending communities, but it still allows us to identify individuals who made undocumented trips, which is our major research interest. We converted emigration costs for different years into constant US dollars of 2004.

Descriptive Results

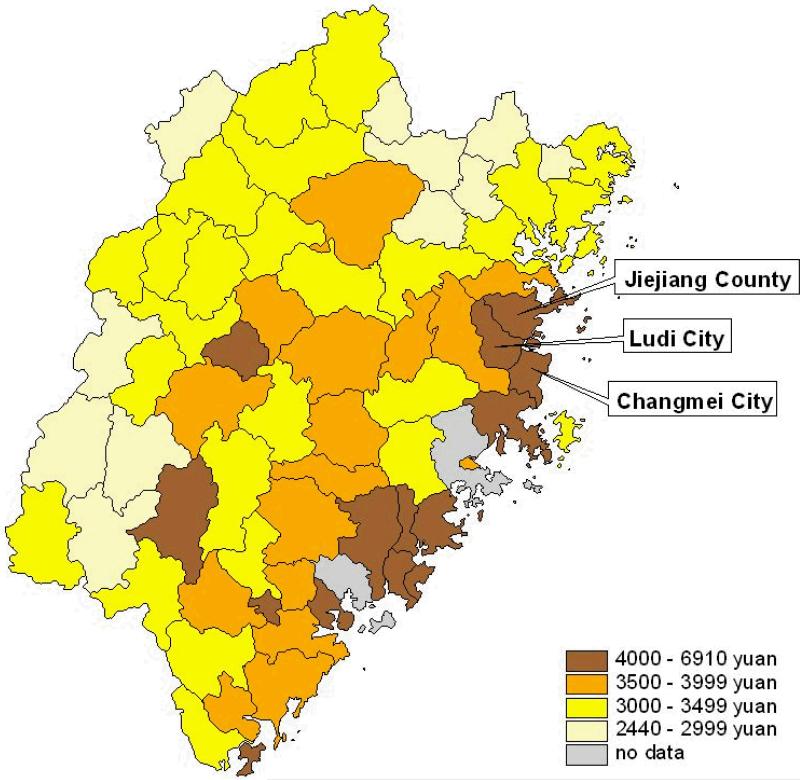

We now turn to discussion of the results. Map 2 shows the location of U.S. bound immigrant-sending communities, located in the northeastern part of Fujian province. The map identifies three places: Ludi city, Changmei city, and Jiejiang county.9 In fact, Changmei is a county-level city and both Changmei and Jiejiang are under the jurisdiction of Ludi city. International migrants typically do not come from Ludi city itself, but rather from rural towns/counties that are under the jurisdiction of Ludi city. However, once in the United States, immigrants from these rural towns/counties usually identify themselves as from Ludi. One important ethnic marker is that all of them speak Fuzhou dialect.

Map 2.

Major Immigrant-sending Regions in Fujian Province, China

Map 3 shows the per capita income by county in Fujian province in 2002. We should note that international migrant-sending counties in our sample are primarily located in the northeastern part of Fujian province. Compared to other parts of Fujian, these migrant-sending counties are clearly above average. For example, the average net per capita income for the three major immigrant-sending counties/cities is around 4000−6900 Yuan, some of the highest in Fujian province. To put these numbers in perspective, in 2002, the per capita net income in Fujian province overall was 3538 Yuan. For China as a whole, the corresponding statistic was 2475 Yuan (NBS, 2003). Clearly, the message here is that immigrants from this part of Fujian province are not fleeing poverty.

Map 3.

Rural Per Capita Net Income Fujian Province, 2002

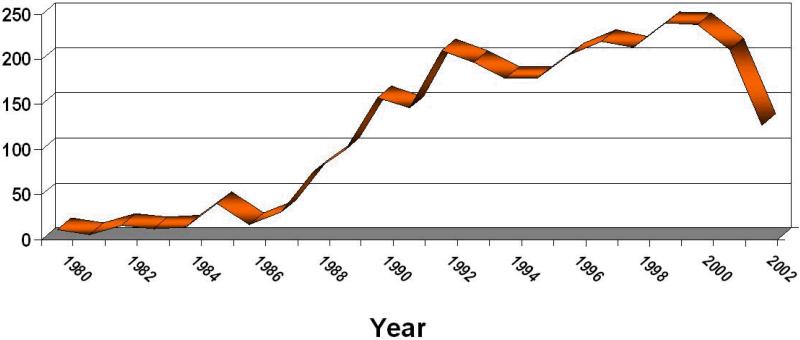

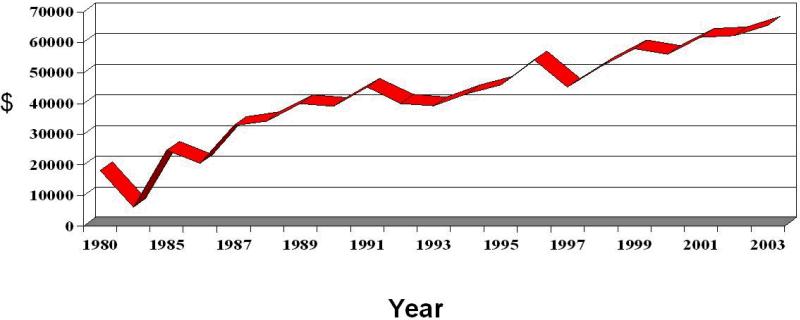

Figure 1 depicts the trend of emigration over time as captured by our data. The new arrival of immigrants from Fujian can clearly be identified from the places of destinations such as New York City, but rigorous analysis of this trend over time is lacking. In Figure 1, we plotted the number of people who left Fujian in each year from 1980 to 2002. It clearly shows that emigration from Fujian started in the early 1980s right after the economic reforms began. It accelerated in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It experienced a slight decline after the 1993 Golden Venture fiasco and increased again in late 1990s. It appears there was a drop in 2001 and 200210. Similar to the trend of increasing emigration from Fujian, the cost of a migration trip has increased steadily as well, as revealed in Figure 2. In the early 1980s the cost of smuggling someone from Fujian to the United States was about $18,000. This is consistent with stories about “wan ba ger” (the $18,000 brother, if translated literately) (Cao, 2005; Chin, 1999). Migration cost follows the path to increase over the years as the smuggling process gets more sophisticated and the demand for going abroad increases. The going price in the early 2000s was in the mid-$60,000.11

Figure 1.

Trend of Emigration by Year

Figure 2.

Emigration Fees by Year

For interviews we conducted with Fujianese immigrants in New York City, we also asked about their detailed travel paths (first destination and other transit countries). Among individuals with valid answers, 86% of them first arrived in Hong Kong before next stop. Among people whose first destination was Hong Kong, nearly half of them flew directly to the United States from Hong Kong and other half went through various transit countries before arriving in the United States. In East Asia and Southeast Asia, the most frequently mentioned transition countries are: Thailand, South Korea, Cambodia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Japan, and Vietnam. In Latin America and South America, the most frequently mentioned transit countries are: Mexico, Guatemala, Columbia, Grenada, Cuba, Argentina, and Brazil. In Europe, the most frequently mentioned transit countries are: France, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands, England, Spain, Belgium, and Switzerland. Clearly, the network of operations encompasses several continents often with the Southeast Asian region as the starting point.

In Table 1, we compare immigrants with non-immigrants on major socio-demographic characteristics. The immigrant sample shows a classic demographic profile: nearly three quarters of them are in the age group of 20−40 years old, and men are much more likely to be immigrants than women. There is some evidence that immigrants are better educated than non-immigrants. Among immigrants, nearly half of them finished junior high school, compared to 34% for non-immigrants. The high price paid for migration journey often receive media's attention. Based on our survey, the mode for smuggling fees is $56,200 and the mean is $19,674 with standard deviation of $23,824 (not shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics about the Fujian Survey Sample

| Variables | Emigrant (%) | Non-Emigrant (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 15−19 | 1.76 | 4.24 | |

| 20−24 | 14.09 | 10.36 | |

| 25−29 | 21.72 | 10.61 | |

| 30−34 | 20.55 | 10.86 | |

| 35−39 | 17.42 | 11.86 | |

| 40−44 | 7.24 | 8.49 | |

| 45−49 | 8.41 | 12.23 | |

| 50−54 | 3.52 | 11.11 | |

| 55−59 | 2.15 | 6.37 | |

| 60 + | 3.13 | 13.86 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 66.34 | 38.58 | |

| Female | 33.66 | 61.42 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Ever married | 74.61 | 83.88 | |

| Never married | 25.39 | 16.13 | |

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 3.16 | 12.78 | |

| Elementary school | 24.51 | 35.59 | |

| Junior high school | 48.42 | 34.71 | |

| Senior high school | 19.17 | 10.90 | |

| Vocational high school | 2.17 | 2.63 | |

| College or above | 2.57 | 3.38 | |

| Religious | |||

| Yes | 54.08 | 53.70 | |

| No | 45.92 | 46.30 | |

| Cadre | |||

| Yes | 1.58 | 8.54 | |

| No | 98.42 | 91.46 | |

| Any other household member is a cadre | |||

| Yes | 22.70 | 19.60 | |

| No | 77.30 | 80.40 | |

| Any other household member is a prior emigrant | |||

| Yes | 50.88 | 84.27 | |

| No | 49.12 | 15.73 | |

| Place of Origin | |||

| Rural | 92.95 | 94.76 | |

| |

Urban |

7.05 |

5.24 |

| Total | 1312 | 511 | 801 |

Initiation of Migration

Our analysis of initiation of international migration is by following the respondents year by year since age 15 to the date of the first U.S. trip or survey date, whichever comes first. Once an individual makes an international migration, the subsequent person-years are eliminated. This procedure yields a total of 28,876 person-years lived by 1312 individuals.

Table 2 presents results from discrete time event-history analysis predicting the first overseas trip. We estimated two models: one with only individual-level and selected household characteristics, and the other model (Model B) with the emigration prevalence ratio added. We focus on model B for interpretation. Statistical test of improvement of Model B over Model A has been conducted and the result is statistically significant because χ2 = (−2 Log-Likelihood for the reduced model) – (−2 Log-Likelihood for the full model) = 4045.601 − 4002.004 = 43.597 (χ2 (critical)=10.827 with 1 d.f. and p=.001). The result shows the importance of adding village migration prevalence ratio in the model. Consistent with other studies on international migration, men and younger people (especially people in the age group of 20−34 years old) are more likely to migrate internationally than others. The relationship between education and international migration is not linear, only individuals with junior and senior high school education are more likely to migrate than people with no formal education.

Table 2.

Coefficients of Discreet-Time Event-History Analysis Predicting First Overseas Trip

| Model A |

Model B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables |

B |

SE |

B |

SE |

|

| Age | |||||

| 15−19 | 1.803 ** | 0.451 | 1.764 ** | 0.449 | |

| 20−24 | 2.284 ** | 0.431 | 2.269 ** | 0.429 | |

| 25−29 | 2.014 ** | 0.415 | 1.979 ** | 0.413 | |

| 30−34 | 1.816 ** | 0.417 | 1.771 ** | 0.415 | |

| 35−39 | 1.490 ** | 0.425 | 1.465 ** | 0.423 | |

| 40−44 | 1.210 ** | 0.437 | 1.228 ** | 0.436 | |

| 45−49 | −0.949 | 0.698 | −0.955 | 0.697 | |

| 50−54 | 0.340 | 0.527 | 0.322 | 0.526 | |

| 55−59 | −0.328 | 0.695 | −0.303 | 0.695 | |

| 60+ (reference) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| Male | 1.106 ** | 0.101 | 1.125 ** | 0.102 | |

| Ever married | 0.073 | 0.168 | 0.049 | 0.168 | |

| Education | |||||

| No formal education (reference) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| Elementary school | 0.305 | 0.277 | 0.328 | 0.276 | |

| Junior high school | 0.600 * | 0.279 | 0.647 * | 0.278 | |

| Senior high school | 0.792 ** | 0.292 | 0.931 ** | 0.291 | |

| Vocational high school | 0.081 | 0.429 | 0.309 | 0.428 | |

| College or above | −0.009 | 0.399 | 0.085 | 0.401 | |

| Religious | 0.082 | 0.095 | 0.107 | 0.096 | |

| Cadre | −1.062 ** | 0.393 | −1.167 ** | 0.393 | |

| Cadre in the family | 0.293 * | 0.117 | 0.327 ** | 0.117 | |

| Prior emigrant in the family | −0.103 | 0.125 | −0.260 * | 0.129 | |

| Number of years elapsed since the earliest emigrant family member left | 0.045 ** | 0.012 | 0.029 * | 0.012 | |

| Village emigration-prevalence ratio | 3.989 ** | 0.614 | |||

| Rural area | −0.150 | 0.187 | −0.152 | 0.188 | |

| Year | |||||

| Before 1985 (reference) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| 1985 | 1.723 ** | 0.482 | 1.647 ** | 0.482 | |

| 1986 | 0.995 | 0.632 | 0.911 | 0.632 | |

| 1987 | 1.269 * | 0.562 | 1.164 * | 0.562 | |

| 1988 | 1.908 ** | 0.437 | 1.746 ** | 0.438 | |

| 1989 | 2.673 ** | 0.354 | 2.448 ** | 0.355 | |

| 1990 | 2.778 ** | 0.345 | 2.464 ** | 0.349 | |

| 1991 | 2.525 ** | 0.365 | 2.137 ** | 0.371 | |

| 1992 | 3.127 ** | 0.323 | 2.634 ** | 0.333 | |

| 1993 | 3.461 ** | 0.309 | 2.876 ** | 0.323 | |

| 1994 | 3.305 ** | 0.318 | 2.637 ** | 0.336 | |

| 1995 | 3.283 ** | 0.320 | 2.539 ** | 0.343 | |

| 1996 | 3.649 ** | 0.305 | 2.810 ** | 0.335 | |

| 1997 | 3.667 ** | 0.306 | 2.736 ** | 0.342 | |

| 1998 | 3.555 ** | 0.314 | 2.541 ** | 0.355 | |

| 1999 | 3.871 ** | 0.305 | 2.759 ** | 0.355 | |

| 2000 | 3.863 ** | 0.310 | 2.646 ** | 0.368 | |

| 2001 | 3.991 ** | 0.313 | 2.700 ** | 0.376 | |

| 2002 | 3.395 ** | 0.345 | 2.065 ** | 0.406 | |

| 2003 | 0.898 | 0.761 | −0.413 | 0.790 | |

| Intercept | −9.515 ** | 0.564 | −9.588 ** | 0.566 | |

| −2 Log Likelihood | 4045.601 | 4002.004 | |||

| Chi-Square | 993.769 ** | 1037.367 ** | |||

| df | 41 | 42 | |||

| Number of Person-Years | 28876 | 28876 | |||

Note:

P < 0.01

P < 0.05.

As discussed earlier, we measure the impact of networks on migration in three ways. At the individual level, one variable is to indicate if there was a family member who migrated before. Unlike many other studies, we also created a new variable to measure the number of years elapsed since the earliest emigrant family member migrated. At the village level, we follow Massey et al. (1994b) to measure the village emigration prevalence ratio, a measure of the extent of emigration in a community in a given year during an individual's life.

Our results show that having a family member who migrated previously has a negative impact on the individual's propensity to migrate, a finding that contradicts most of the studies on international migration from Mexico to the United States. However, this finding must be placed in the Chinese context. The escalating smuggling fees makes it impossible for a family to send more than one person abroad in a short period of time. We also note the variable “number of years elapsed since the earliest family member migrated” has a positive sign and is statistically significant. This suggests that it is not that migration networks are not important; it just takes time for this effect to be felt. This probably means that once a migrant pays off the debt, he/she will be in a position to bring another member from the family into the migration process.

Consistent with Massey et al. (1994b), the community/village emigration prevalence ratio has a very strong and positive impact on migration. In fact, for all the variables in the model, this is by far the most important variable in predicting the probability of migration. As suggested by Massey et al. (1994b), the migration network ties between earlier migrants who came from the same village and potential migrants in these communities provide an important channel of information on potential migrant destinations and support for settlement at the destination. We also suggest that in the case of emigrants from Fujian, it is often the case that earlier immigrants from the same village (tongxiang or laoxiang) loan the money to the newly arrived individuals. Then the newly arrived immigrants will pay their loan back to the tongxiang over time. Borrowing money from hometown people often comes with low interest or in some cases bears no interest, which is a much better alternative than shark loans. This interpretation is also corroborated by our in-depth interviews with immigrants in New York City. Take the case of Mr. Chen for example, who is very active in immigrant community affairs and came to the United States from Changmei in the early 1980s. Chen told us that he personally helped about 15−20 immigrants from Changle. Mr. Chen never worries about the possibility that these newly arrived immigrants will not pay back the loan because these migrants often work for bosses who are from the same village or the same town/county. Another migrant, Mr. Zheng, who came to the United States in 2000, told us, “in my hometown, if you want to borrow money to start a business, it is as hard as climbing up to the sky (nanyu shang qingtian). But if you tell fellow villagers that your son is on the way to the United States, they will line up at your door trying to loan you the money because they can get much better interest rate for their money than from the bank. Of course there are also some relatives who are willing to loan you money without charging interest.” Overall, migration networks have a major impact on future patterns of emigration from Fujian, but it is mainly through spreading information to the community and promoting the migration of fellow villagers.

Regarding the impact of cadre status, we see that cadres are less likely to emigrate compared to non-cadres. Relating back to the market transition literature, this could mean that cadres in rural areas still hold a lot of power, even in this coastal province. Our fieldwork experience suggests that cadres are important players in village life. They make decisions that have impacts on the life and well being of other villagers, and some also reap financial gains through corruption. Under these circumstances, they have fewer incentives to migrate. However, individuals from households with cadres are more likely to migrate than others. This is because village cadres are often the first to know about good opportunities for going aboard and are likely to pass along this information to their household members first. In addition, as we will show later, individuals from households with cadres tend to have better prices on the cost of migration, which provides further incentives for migration.

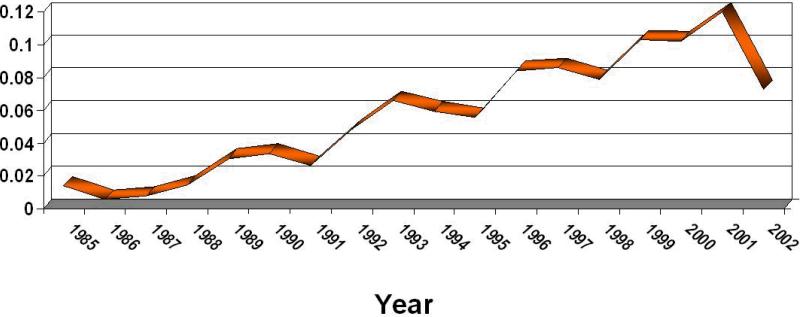

To have a good appreciation of the trends of emigration over time, we generated the predicted probability of emigration for individuals who are 20−24 years old. In doing so, we assume that the individuals are of rural origin, male and married, have a junior high school education, are religious, have no cadre in the household, and have a household member being a prior emigrant. As Figure 3 shows, the predicted probability was low (.01) in the 1980s, then increased to about .06 in the 1990s, and peaked at about .10 in the 2000s. This again illustrates the idea that for many young men in these villages, international migration is the thing to do in the early 2000s.

Figure 3.

Predicted Probabilities of First Overseas Trip by Year (For Age Group 20−24 Only)

Analysis of Trip Costs

Migration has benefits and costs. Undocumented migration costs a lot more than documented migration. Neo-classical economics suggests a necessary condition for migration to occur is that its benefits are larger than the costs. One of the major differences between China and other countries such as Mexico is that the cost of migration is much higher for potential immigrants from China than from Mexico. This in large part reflects the distance between China and the United States and consequently, the difficulty of making international trips without legal documents. Thus, we are interested in the determinants of trip cost. To do this, we focus on individuals who have made at least one trip to the United States, and the results are summarized in Table 3. We estimated two sets of models: Model A with only basic socio-demographic characteristics and Model B with additional important variables included. We focus our discussion on results from Model B.12 Here again, there is some support for the hypothesis that village cadres continue to be important actors in the village. Individuals from households with village cadres pay significantly lower fees for the migration trip. Specifically, migrants from households with cadre(s) paid about 73% of migration fees typically paid for migrants who are from households with no cadres. 13

Table 3.

Coefficients of OLS Regression Predicting Logged Smuggling Cost

| Model A |

Model B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables (Dummy Variables) |

B |

SE |

B |

SE |

|

| Age | |||||

| 15−19 | 1.649 ** | 0.621 | 1.608 * | 0.641 | |

| 20−24 | 1.883 ** | 0.601 | 1.838 ** | 0.621 | |

| 25−29 | 1.968 ** | 0.578 | 1.968 ** | 0.589 | |

| 30−34 | 2.122 ** | 0.582 | 1.834 ** | 0.599 | |

| 35−39 | 2.380 ** | 0.591 | 2.100 ** | 0.603 | |

| 40−44 | 1.518 * | 0.629 | 1.491 * | 0.630 | |

| 45−49 | 0.237 | 0.997 | −0.268 | 0.940 | |

| 50−54 | 0.921 | 0.769 | 0.943 | 0.744 | |

| 55−59 | −0.079 | 0.990 | −0.799 | 0.958 | |

| 60+ (reference) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| Male | 0.410 ** | 0.146 | 0.287 | 0.149 | |

| Ever married | −0.775 ** | 0.237 | −0.533 * | 0.226 | |

| Education | |||||

| No formal education (reference) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| Elementary school | 0.044 | 0.405 | 0.116 | 0.382 | |

| Junior high school | 0.320 | 0.404 | 0.299 | 0.381 | |

| Senior high school | −0.202 | 0.418 | −0.145 | 0.396 | |

| Vocational high school | 0.868 | 0.602 | 0.436 | 0.568 | |

| College or above | −0.717 | 0.593 | −0.688 | 0.558 | |

| Cadre | −0.461 | 0.585 | |||

| Cadre in the family | −0.317 * | 0.152 | |||

| Prior emigrant in the family | −0.061 | 0.178 | |||

| Number of years elapsed since the earliest emigrant family member left | −0.055 ** | 0.020 | |||

| Village emigration-prevalence ratio | −0.488 | 0.856 | |||

| Intercept | 7.085 ** | 0.668 | 7.542 ** | 1.049 | |

| Root MSE | 1.431 | 1.308 | |||

| R-Square | 0.160 | 0.343 | |||

| Adj R-Square | 0.131 | 0.275 | |||

| Number of Observations | 471 | 470 | |||

Note:

P < 0.01

P < 0.05.

Other variables controlled: rural/urban status and year of emigration.

As in the case for the persistence of power for cadres in urban China, as reported by Bian and Logan (1996) and Walder (2002b), we too find the persistence of power for rural cadres in the process of international migration. In addition, the more years passed since the first migrant in the household, the lower the fees for the migration trip. This suggests that migration merchants (smugglers) may be willing to give some discounts if a household has already sent one migrant, underscoring the business nature of their operation.

Summary and Conclusion

Although emigration from China's Fujian province has drawn worldwide attention in recent years (Rosenthal, 2000; Wong, 2005), systematic studies of this emigration are still lacking. This paper provides, to our knowledge, the first survey-based study of international migration from China's Fujian province. Several major findings are worth highlighting here. We begin with a discussion of the broad patterns of migration. Clearly, poverty is not the explanation for the rise of emigration from Fujian. As we show in this paper, Fujian province has particularly benefited from China's market transition, as reflected in per capita income growth. Likewise, within Fujian province, these communities/regions that have sent thousands of migrants abroad are also communities that enjoy relatively high levels of income. Our survey data also confirm the general perception about the trend of emigration from Fujian province. This trend of increases in emigration is also consistent with reports and observations from migrant destination communities such as New York City's Chinatown.

Theoretically, this paper is motivated by two strands of research literature: one on the cumulative causation from international migration and the other on the market transition debate. Our research has provided fresh evidence and contributes to both of them. The international migration literature in the past two decades has provided strong evidence on the utility of cumulative causation to understand the perpetuation of international migration, especially in the case of Mexican migration to the United States. Like in the case of Mexico, our study suggests the importance of migration networks and the feedback effect on migrant-sending communities. We argue that in the Chinese case, the power of migration networks is not only reflected in feeding information about potential migrant destinations and providing assistance in housing and employment, but perhaps more importantly in “financing” the trip by loaning money to new migrants from the same villages or towns. This step is crucial because of the expensive nature of this migration experience. This financial guarantee from “tongxiang” immigrants in the migrant destination locations makes migration much more accessible to a broad spectrum of individuals, and ultimately increases the probability of future migration from these villages. Within migrant households, the migration networks operate somewhat differently in the Chinese context than in the Mexico case. Because of the large sum of money demanded for international migration with a far away destination, it is usually not possible to send another household member within a short period of time. However, once the debt for the first migrant in the household is paid off, it is likely that another member of the household will migrate. This is a new household strategy not commonly found in the case of Mexican migration to the United States (Massey, 1990). Our findings point to a new theoretical and empirical research direction, i.e. identifying conditions under which cumulative causation of migration may work differently. In our case, we show that connections to power figures (village cadres) strengthen the impact of cumulative causation on migration by lowering the costs/fees of migration. Further research may identify other factors that warrant some refinement of cumulative causation theory of migration.

We would like to further underscore the scholarly value of bringing the case of China in the comparative study of international migration. Indeed, cross-national comparison has recently been identified by several scholars as one of the strategic research areas in the 21st century. For example, Portes (1999) highlights the value of studying “the role of social networks and social capital in initiating and sustaining migration flows (p.33).” Our first attempt to do so in the Chinese case has certainly born fruits. Of course other aspects of comparative exercise should also be pursued. One direction could be to examine how undocumented migrants from China and Mexico use migration networks for employment and entrepreneurial activities in the destination communities. Equally important is the research design to study how Fujianese in the United States fare compared to the Fujianese who went to European countries such as Italy and the Great Britain.

Our paper also addresses issues concerning China's market transition experience. It is well-known that China has been experiencing a major transformation from a planned economy to market economy. This transformation has captivated the attention of many sociological studies in recent years. The core of this line of research has been to identify the winners and losers in this transition to a market economy (Nee, 1989). We join this debate by providing new empirical evidence from the early 2000s on the role of village cadres in the international migration in Fujian province. Our work also moves the current literature on market transition debate into a new direction by focusing on non-income variables (i.e. migration) (Zhou, 2000). In a fast-changing society such as China, benefits and rewards go far beyond income alone.

Consistent with earlier studies by Bian and Logan (1996) and Walder (2002a and 2002b), our results show that households with village cadres seem to enjoy advantages in this process of international migration. This advantage works in two ways. One is that individuals from households with village cadres are more likely to make international migration. Further, migrants from households with cadres pay a reduced fee compared to migrants from households without village cadres. This reflects the continued advantage for village cadres in getting access to crucial information about migration opportunities and bargaining for the price of the migration trips using their privileged position in exchange for other favors that smugglers/recruiters may seek. If we interpret the human smuggling process as a business enterprise, the behavior of village cadres in this case is not that much different from other kinds of legitimate entrepreneurs, i.e. the use of their position and market opportunities for economic gains. This also leads to the possibility of participation of players (coast guards, border patrol agents etc.) at different levels of government agencies. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the flow of international migration from Fujian has sustained for such a long time without any involvement of officials/cadres at critical connection points. In the age of market transition and ubiquity of corruption, it seems everything has a price and can be negotiated or even bought. 14

The enduring advantage for village cadres in Fujian province, a province that has experienced remarkable marketization since the late 1970s, deserves some further thought. As we mentioned earlier, Nee's survey in 1985 (which his 1989 seminal paper was based on) was also carried out in Fujian province. Fujian province is among provinces that are in the forefront of China's economic reform program. If Nee's hypotheses accurately capture the empirical reality, we should be most likely to observe declined significance of cadre status in Fujian province. The fact that cadre advantage persists in one of the most marketized provinces in China after more than 17 years after Nee's original survey in Fujian, suggests at least that rural Fujian has not changed in such a way as Nee predicted. Another feature of the province, which is different from more other provinces of China, is high level of emigration. As documented in this paper, migration often selects individuals with better education and relatively young age. In communities with high rate of emigration is often characterized by presence of large numbers of women, elderly, and children. This demographic reality may also help cadres to retain and reinforce their positional power. 15

Finally, as we noted earlier emigration from China's Fujian province has been on the rise since the late 1980s and continued to be so in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is ironic that this was also a time when the governments of the United States and China implemented policies to stop this flow of mostly undocumented migration. In the United States, billions of dollars have been spent on high-tech equipment to monitor human movement and border control. On the Chinese side, the government has imposed huge fines for individuals who are caught in undocumented border crossings or for migrants who were deported from the United States. The Chinese government has especially increased the penalty for smugglers. Despite the tough measures from both governments, not only did emigration continue to increase, it has also expanded to other countries, specifically to countries such as Italy, England, and France (Li, 2005; Pieke et al., 2004). This is especially surprising in light of China's legacy of a strong state. Perhaps students of migration are not that surprised and in some sense this is another case to illustrate the idea that migration, once started, will become a self-feeding process and keep its own momentum. This self-feeding process is certainly further facilitated by China's integration into the world economy. As Massey and Espinosa (1997) argued, these processes “create new links of transportation, telecommunication, and interpersonal acquaintance, connections that are necessary for the efficient movement of goods, information, and capital but also encourage and promote the movement of people-students, business executives, tourists, and ultimately, undocumented workers (p. 992).” In the long run, with rising income and economic prosperity, motivation to emigrate from China will ultimately subside. Before that happens, given China's current disparity between rural and urban areas and among different regions along with well-established migration networks, we expect emigration from China will continue.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1 R01 HD39720-01), the National Science Foundation (SES-0138016), and the Ford Foundation (1025-1056). The Center for Social and Demographic Analysis of the University at Albany provided technical and administrative support through a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 HD044943-01A1). Douglas Massey and Victor Nee provided extremely helpful advice at the initial stage of the project. We thank Cameron Campbell, James Lee, Myron Gutmann, Yu Xie and other participants at seminar at University of Michigan where earlier version of this paper was presented. Comments from four anonymous AJS reviewers helped improve the paper Thanks also go to Professor Guo Yucong, Violet Guo, Simon Chen, and Xueji Liang for assistance during data collection and file preparation in China and New York City.

Footnotes

Our fieldwork and other sources (Kwong, 1997) suggest that in earlier years there were emigrants from Fujian to the United States mostly via Hong Kong, but the magnitude of this flow is much smaller compared to that of post-1980 emigration from Fujian.

Some versions of these ideas have been used in previous studies of emigration from China as well as from Hong Kong (Li, 2005; Salaff et al., 1999)

1 US dollar roughly equals 8.2 Yuan (RMB) in 2004.

We are very grateful to Yu Xie for making the suggestion of examining smuggling fees for households with cadres.

We define village cadres in the following: village head (cun zhang or cun zhuren), deputy village head (fu cunzhang), village party secretary (shuji), deputy party secretary (fu shuji), accountant ( kuai ji), cashier (chu na), village security director (zhibao zhuren) , director for women's affairs (fu lian zhuren).

It is usually the case that towns that send a lot of immigrants to the United States often establish their town-based hometown association once the number of immigrants reaches a certain threshold level.

It is true, however, that family members may not know details of the actual migration journal and job history of migrants, for information on this, we can draw on our sample of immigrants interviewed in New York City.

For samples at destinations, Massey and his colleagues select about 10% of the corresponding community samples (Massey et al., 1994b).

Following standard research procedures, all names for survey locations and individuals in this paper are fictional.

The drop in emigration may also be caused by the fact that some of our interviews in China were conducted in November 2002, so people who left in December 2002 were not reflected in our data.

Using data from Mexican Migration Project, we estimate the going price for Mexican migrants was about $2000 during similar time period.

We have also performed statistical test of improvement of Model B over Model A and the result is significant (details are available from the authors on request).

Following a suggestion from an anonymous reviewer, we also estimated models with interaction term between cadre status and calendar year to see if cadre advantage in this regard declines over time. The results are not statistically significant.

Our in-depth interviews with immigrants in New York City give us some clues about this. One migrant recalled his experience of coming to the United States. in 1994. The night he left Fujian on a fishing boat, he saw a coast guard patrol boat in distance. He was told by others who traveled with him that the patrol boat was there to protect them before migrants were picked up by a another bigger boat at the international waters. Another immigrant who came to the United States in 1991 told us another story. In the early 1990s, it was not common to have private telephone for most villagers. With permission of village cadres, family members of those immigrants who just reached the United States gathered at the village office (where telephone service was available) to hear the good news of safe arrival of other family members. Despite these anecdotal stories, we admit that we do not have systematic evidence on this.

We thank one anonymous reviewer for suggesting this link.

References

- Allison Paul. Event History Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul. Survival Analysis Using SAS. SAS Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bian Yanjie, Logan John R. Market Transition and the Persistence of Power. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:739–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bian Yanjie. Indirect Ties, Network Bridges, and Job Searches in China. American Sociological Review. 1997;62:366–385. [Google Scholar]

- Cao Jian. Rise in Exchange Rate Affects Market for Human Smuggling. The World Journal. 2005:E1. [Google Scholar]

- Chin Ko-lin. Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine Immigration to the United States. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth, Massey Douglas S. The Limits to Cumulative Causation: International Migration from Mexican Urban Areas. Demography. 2004;41:151–172. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guang Lei, Zheng Lu. Migration as the Second-best Option: Local Power and Off-farm Employment. China Quarterly. 2005;181:22–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guest Philip. God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York's Evolving Immigrant Community. New York University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong Peter. Forbidden Workers: Illegal Chinese Immigrants and Chinese Labor. New Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Li Minghuan., editor. Fujian Overseas Chinese Community Surveys: Identify, Networks, and Culture. Xiamen University Press; Xiamen: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Zai. Demography of Illicit Emigration from China: A Sending Country's Perspective. Sociological Forum. 2001;16:677–701. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Xueyi. Report on Social Stratification in Contemporary China. Social Science Publishing House; Beijing: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. The Ethnosurvey in Theory and Practice. International Migration Review. 1987;21(4):1498–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas. S. Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration. Population Index. 1990;56(1):3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Arango Jaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela, Taylor E. Edward. An Evaluation of International Migration Theory: The North American Case. Population and Development Review. 1994a;20:699–751. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Goldring Luin, Durand Jorge. Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of 19 Mexican Communities. American Journal of Sociology. 1994b;99:1492–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S., Espinosa Kristin E. What's Driving Mexico-U.S. Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical, and Policy Analysis. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;102:939–999. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Why Does Immigration Occur? In: Hirschman Charles, Kasinitz Philip, DeWind Josh., editors. The Handbook of International Migraiton: The American Experience. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1999. pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China . China Statistical Yearbook. China Statistical Publishing House; Beijing: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China . Tabulation on the 2000 Population Census of the People's Republic of China. China Statistics Publishing House; Beijing: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nee Victor. A Theory of Market Transition: From Redistribution to Markets in China. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:663–81. [Google Scholar]

- Nee Victor. Social Inequalities in Reforming State Socialism: Between Redistribution and Markets in China. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:267–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nee Victor. The Emergence of a Market Society: Changing Mechanisms of Stratification in China. American Journal of Sociology. 1996;101:908–49. [Google Scholar]

- Parish William L., Zhe Xiaoye, Li Fang. Non-farm Work and Marketzation of the Chinese Countryside. China Quarterly. 1995;143:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Yusheng. Kinship Networks and Entrepreneurs in China. American Journal of Sociology. 2004;109:1045–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Pieke Frank N., Nyiri Pal, Thuno Mette, Ceccagno Antonella. Transnational Chinese: Fujianese Migrants in Europe. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni Alberto, Massey Douglas S., Ceballos Miguel, Espinosa Kristin, Spittel Michael. Social Capital and International Migration: A Test Using Information on Family Networks. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:1262–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Sensenbrenner Julia. Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98:1320–50. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro. Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities. In: Hirshman Charles, Kasinitz Philip, DeWind Josh., editors. The Handbook of Migration: The American Experience . Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1999. pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Poston Dudley L., Jr., Mao Michael Xinxiang, Yu Mei-Yu. The Global Distribution of the Overseas Chinese around 1990. Population and Development Review. 1994;20:631–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal Elizabeth. Chinese Town's Main Export: Its Young Men. The New York Times. 2000 June 26;:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Salaff Janet W., Fong Eric, Wong Siu-lun. Using Social Networks to Exit Hong Kong. In: Wellman Barry., editor. Networks in the Global Village. Westview Press; Boulder: 1999. pp. 299–329. [Google Scholar]

- Walder Andrew. Income Determination and Market Opportunities in Rural China, 1978−1996. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2002a;30:354–375. [Google Scholar]

- Walder Andrew. Markets, Economic Growth, and Inequality in Rural China in the 1990s. American Sociological Review. 2002b;65:231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wong Edward. Militants Release Chinese Hostages. [January 22, 2005];The New York Times. 2005 January 22; http://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/22/international/middleeast/22cnd-iraq.html?oref=login...

- World Journal Eight Chinese were Safely Released in Iraq. 2005 January 23;:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Yu, Hannum Emily. Regional Variation in Earnings Inequality in Reform-Era Urban China. American Journal of Sociology. 1996;101:950–992. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Kazuo. Event History Analysis. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Xueguang. Economic Transformation and Income Inequality in Urban China: Evidence from Panel Data. American Journal of Sociology. 2000;105:11135–1174. [Google Scholar]