Abstract

Introduction

Liver dysfunction is a common feature of severe sepsis and is associated with a poor outcome. Both liver perfusion and hepatic inflammatory response in sepsis might be affected by sympathetic nerve activity. However, the effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA), which is associated with regional sympathetic block, on septic liver injury are unknown. Therefore, we investigated hepatic microcirculation and inflammatory response during TEA in septic rats.

Methods

Forty-five male Sprague-Dawley-rats were instrumented with thoracic epidural catheters and randomized to receive a sham procedure (Sham), cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) without epidural anesthesia (Sepsis) and CLP with epidural infusion of 15 ul/h bupivacaine 0.5% (Sepsis + TEA). All animals received 2 ml/100 g/h NaCl 0.9%. In 24 (n = 8 in each group) rats, sinusoidal diameter, loss of sinusoidal perfusion and sinusoidal blood flow as well as temporary and permanent leukocyte adhesion to sinusoidal and venolar endothelium were recorded by intravital microscopy after 24 hours. In 21 (n = 7 in each group) separate rats, cardiac output was measured by thermodilution. Blood pressure, heart rate, serum transaminase activity, serum TNF-alpha concentration and histologic signs of tissue injury were recorded.

Results

Whereas cardiac output remained constant in all groups, sinusoidal blood flow increased in the Sepsis group and was normalized in rats subjected to sepsis and TEA. Sepsis-induced sinusoidal vasoconstriction was not ameliorated by TEA. In the Sepsis + TEA group, the increase in temporary venolar leukocyte adherence was blunted. In contrast to this, sinusoidal leukocyte adherence was not ameliorated in the Sepsis + TEA group. Sepsis-related release of TNF-alpha and liver tissue injury were not affected by Sepsis + TEA.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that TEA reverses sepsis-induced alterations in hepatic perfusion and ameliorates hepatic leukocyte recruitment in sepsis.

Introduction

The liver is critically involved in a multitude of vital physiological processes and contributes to the host's immune reaction in systemic inflammatory response and sepsis [1-3]. Impaired microcirculation and intrahepatic inflammatory reaction are hallmarks in primary and secondary hepatic injuries [4-6]. In severe sepsis and trauma, liver injury is associated with increased mortality and length of hospital stay [7-10]. The hepatic immune response determines pathogen clearance and the systemic immune reaction [1,5,11]. After prolonged inflammation, hepatic immune dysfunction contributes to mortality [12]. Protection of liver function is therefore crucial to the maintenance of homeostasis in perioperative and critical care medicine.

Sympathetic nerve activity plays a crucial role in hepatic injury and immune response. Increased sympathetic tone alone induces intrahepatic inflammation and liver injury in healthy mice, whereas sympathetic denervation reduced perioperative hepatic injury [13-15]. In sepsis, both α- and β-adrenoreceptors impair hepatic function and immune response [16-18].

Thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) promotes postoperative intestinal recovery and reduces cardiovascular mortality, most probably mediated by regional sympathetic block [19-28]. Recently, TEA has also been shown to ameliorate organ injury and improve outcome in sepsis and necrotizing pancreatitis [28-32]. The hepatic effects of TEA in sepsis, however, have never been subject to investigation.

Therefore, we conducted a randomized, blinded experimental study to test the hypothesis that TEA: improves hepatic microvascular perfusion and attenuates leukocyte activation in sepsis; and influences systemic inflammatory response and liver tissue injury induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in rats.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the animal care committee of the District Government of Muenster. Animals received standard chow and were kept in a 12 hour light-dark-cycle. Food was withheld 12 hours prior to surgery. The animals had free access to water.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 275 to 300 g; Harlan-Winkelmann, Borchen, Germany) were anesthetized by isofluran in 50% oxygen. Central venous and arterial lines (0.96 mm once daily; Liquidscan, Ueberlingen, Germany) were introduced. Epidural catheters (0.61 mm once daily) were inserted at L3/L4 and advanced to Th6 [26]. All catheters were exteriorized at the neck of the animal and protected by a swivel device. The cecum was ligated below the ileocecal valve to maintain intestinal continuity and then punctured at two locations with an 18-gauge needle. Subsequently anesthesia was terminated and volume resuscitation was performed using 2 mL/100 g/hour isotonic sodium chloride (NaCl) solution intravenously. The animals were housed individually for the following 24 hours. The correct position of the epidural catheter was confirmed by autopsy after completion of the experiment.

After instrumentation, animals were randomly allocated to one of the three groups by closed envelopes: Sham = sham operation, 15 μl/hour NaCl 0.9% epidural; Sepsis = CLP 24 hours, 15 μl/hour NaCl 0.9% epidural; Sepsis + TEA = CLP 24 hours, 15 μl/h bupivacaine 0.5% epidural. The investigators were not aware of the group assignment.

Twenty-four hours after CLP and sham-laparotomy, mean arterial blood pressure was recorded using a standard transducer (PMSET 1 DT, Becton Dickinson, Germany) and a monitor (Siemens Sirecust 404, Siemens, Germany). Heart rate was derived from the arterial pressure curve. For blood gas analyses, 80 μl blood was withdrawn. Motoric block was quantified using an established motor score derived from the Bromage score and adapted to rats [33].

Intravital microscopy

Twenty-four hours after sepsis induction, 24 animals (n = 8 per group) were then re-anesthetized and tracheotomized [29]. Intravital microscopy of the left liver lobe was performed as follows: median laparotomy was extended by a left subcostal incision and the hepatic ligaments of the left liver lobe were carefully dissected. The animal was placed in a 110° position on its left side onto the microscope (Eclipse 300, Nikon, Düsseldorf, Germany). The left liver lobe was exteriorized and the lower surface was placed on a microscope slide in a tension free position. Intravenously, 2 μmol/kg sodium fluorescein and 0.2 μmol/kg rhodamine 6 G (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) were used for contrast enhancement.

In each experiment, 10 randomly chosen acini and 10 postsinusoidal venoles were recorded for 30 seconds both with sodium-fluorescein and rhodamine contrast enhancement. Offline image analysis was performed by a blinded investigator (CG) using a computer-assisted image analysis system (AnalySIS, OSIS, Muenster, Germany). Hepatic microcirculation was assessed by the periportal sinusoidal diameter of 10 sinusoids per acinus and the loss of sinusoidal perfusion, defined as the number of non-perfused sinusoids divided by all visible sinusoids of the acinus.

The leukocyte adhesion was evaluated separately in sinusoids and postsinusoidal venoles. Temporary adherent, that is, slowly moving or adhering at the sinusoidal wall for less than 20 seconds, and permanently adherent, that is, adherent for more than 20 seconds, leukocytes were counted in each acinus and expressed as cells/μm2. Accordingly, temporarily and permanently adherent leukocytes in the venoles were counted as cells/μm2 venolar endothelium.

Cardiac output and liver injury

In another set of 21 animals, cardiac output was determined applying the thermodilution technique 24 hours after sepsis. In these animals, a thermocouple catheter (IT21, Physitemp, Clifton, NJ, USA) was introduced into the aortic arch via the left carotid artery during instrumentation. For measurement of cardiac output, the area under temperature curve after injection of 0.3 ml cold saline solution (8°C) was recorded (Cardiac Output pod and Powerlab 4/20, ADInstruments, Spechbach, Germany). The results of three measurements were averaged in each animal. To reduce bias of emotional stress the procedure was mimicked every hour for four hours before measurement.

Liver cell injury was assessed 24 hours after induction of sepsis by measuring serum activities of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. Blood was withdrawn via aortic puncture and plasma enzyme activity was determined by means of standard enzymatic techniques (Ektachem, Kodak, Stuttgart, Germany).

Specimens of the left liver lobe were collected immediately after death and fixed by immersion in 4% formaldehyde solution. Subsequently, they were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax to cut sections at a thickness of 5 μm. Slides were stained with H&E and assessed by an experienced pathologist.

Serum TNF-α

Twenty-four hours after CLP and sham-procedure respectively, serum concentration of TNF-α was measured by a commercially available anti-rat TNF-α ELISA (BD OptEIA, Cat No. 550734, Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and read-out by a fluorometric plate reader (EL808, BioTek, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany).

Statistics

Sigmastat 3.0 (Systat Software, Richmond, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Normal distribution and equal variance tests were performed. Sepsis-induced and TEA-related effects were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Student Newman Keuls test or ANOVA on Ranks with post-hoc Dunn's test as appropriate. A P < 0.05 was defined as the level of significance. Data are presented as mean ± 95% confidence interval or as median (25%/75% percentiles) as appropriate.

Results

All animals allocated to the sepsis groups showed signs of lethargy, piloerection, and exudation around the eyes and nose 24 hours after induction of sepsis. Peritoneal inflammation and purulent ascites was present when the abdomen was reopened for intravital microscopy.

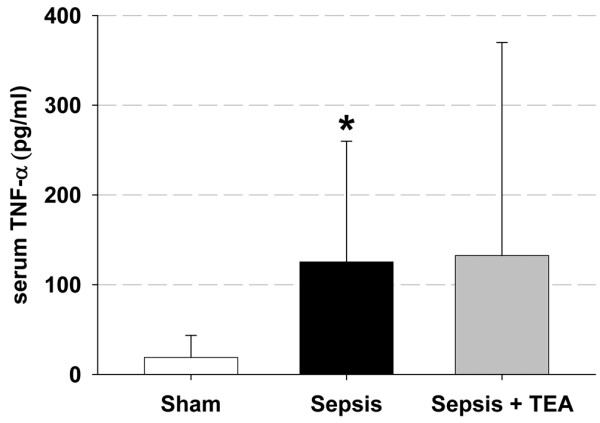

Compared with the Sham-group, mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate were not affected in the untreated Sepsis or Sepsis + TEA groups. Cardiac output also remained constant both in the Sepsis and Sepsis + TEA groups. Arterial oxygen tension and pH were not altered by sepsis or treatment with TEA (Table 1). Serum-lactate concentrations were increased to 1.25 (1.00/1.50) mmol/l in the Sepsis group compared with 0.8 (0.7/0.9) mmol/l in the Sham group (P < 0.05). Leukocyte count dropped from 6430 ± 3099 cells/μL in Sham animals to 2228 ± 1129 cells/μl in the CLP group (P < 0.05). In addition, the Sepsis group was characterized by a drop in platelet count compared with the Sham-group (197,000 ± 102,000 cells/μl vs. 338,000 ± 64,000/μl; P < 0.05). These parameters were not altered in animals subjected to Sepsis + TEA as compared with the untreated Sepsis group. Serum TNF-α concentration was elevated after 24 hours in the Sepsis-group (P < 0.05 vs. Sham). This increase was not ameliorated in the Sepsis+TEA group (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Cardiorespiratory parameters

| MAP (mmHg) |

HR (bpm) |

CO (ml/min) |

pH | PaO2 (mmHg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 136 ± 10 | 432 (404/444) |

420 ± 74 | 7.42 ± 0.02 | 87 ± 10 |

| Sepsis | 121 ± 11 | 468 (447/477) |

402 ± 68 | 7.40 ± 0.09 | 91 ± 20 |

| Sepsis + TEA | 129 ± 16 | 420 (297/480) |

391 ± 152 | 7.39 ± 0.09 | 90 ± 11 |

Twenty-four hours after induction of sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture and sham procedure, respectively. None of these parameters were significantly altered by sepsis or sepsis + thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA). Data (n = 7) each group are displayed as mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI) or median (25%/75% percentile).

CO = cardiac output; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PaO2 = partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

Figure 1.

Serum TNF-α. Serum TNF-α 24 hours after induction of sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture and sham procedure respectively. In Sepsis, serum TNF-α was increased compared with Sham (* P < 0.05 vs. Sham). Thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) did not ameliorate this sign of systemic inflammation. Data (n = 7 in each group) are displayed as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Hepatic microcirculation and leukocyte adherence

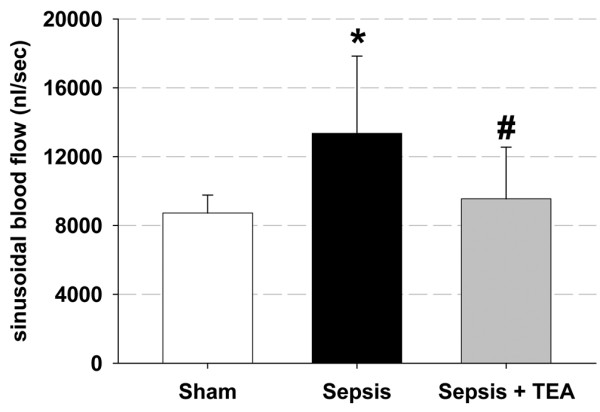

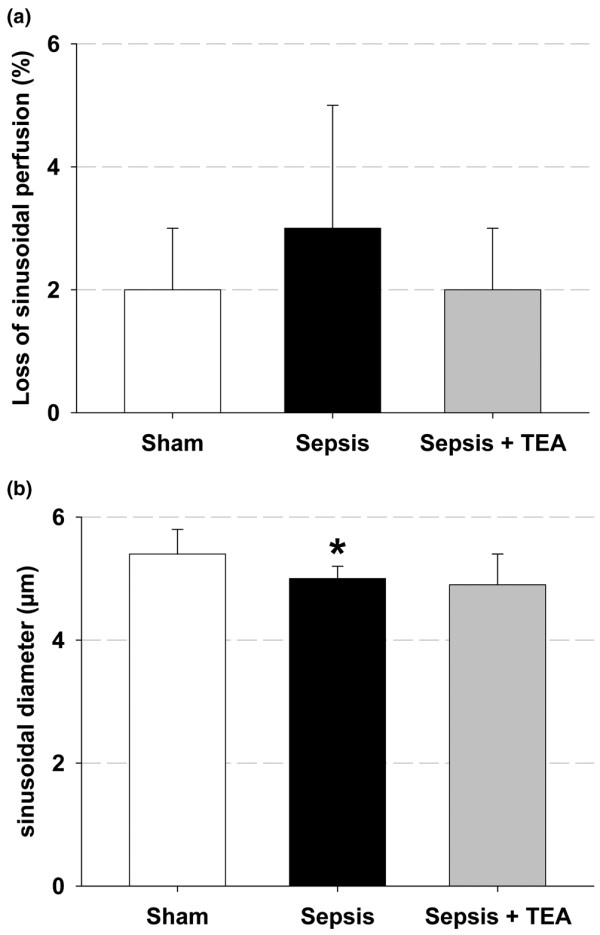

Sinusoidal blood flow increased in the Sepsis group, whereas in the Sepsis + TEA group flow returned to Sham levels (Figure 2). The numbers of perfused sinusoids did not differ between groups. However, in the Sepsis group sinusoidal constriction was induced, which was not influenced in the Sepsis + TEA group (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Hepatic microvascular blood flow. Sinusoidal blood flow 24 hour after induction of sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture and sham procedure, respectively. In Sepsis, blood flow was increased compared with Sham (* P < 0.05 vs. Sham). Thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) reduced blood flow (# P < 0.05 vs. Sepsis). Data (n = 8 in each group) are displayed as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Hepatic microcirculation. (a) Percentage of non-perfused sinusoids and (b) sinusoidal width 24 hours after induction of sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture and sham procedure, respectively. In Sepsis sinusoidal vasoconstriction occurred (* P < 0.05 vs. Sham), which was not influenced in Sepsis + thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA). Sinusoidal perfusion was neither influenced in Sepsis nor in Sepsis + TEA. Data (n = 8 in each group) are displayed as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

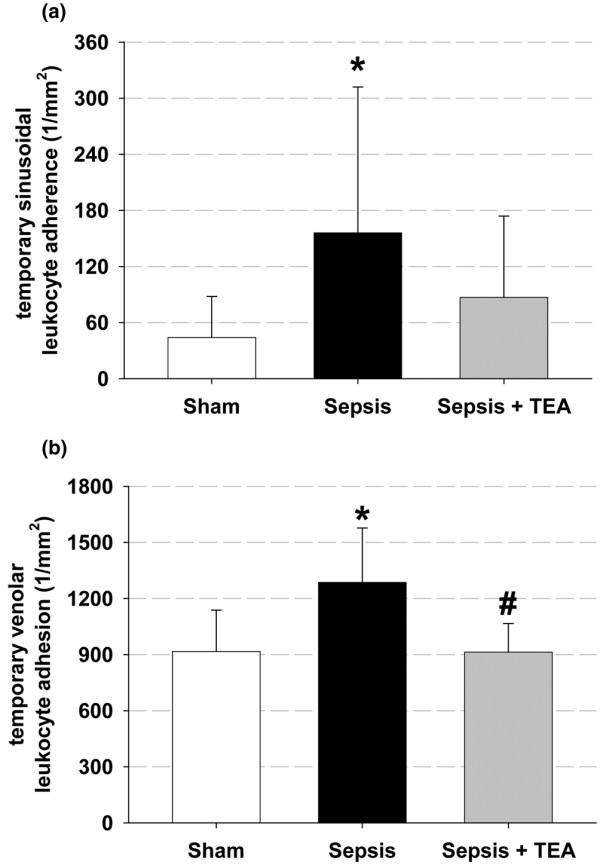

Temporary leukocyte adhesion increased in sepsis both in the sinusoids and in the postsinusoidal venules. TEA reduced the temporary venolar leukocyte adhesion significantly, whereas it did not affect the increased sinusoidal adherence (Figure 4). The permanent sinusoidal and venolar leukocyte adherence was neither affected in the Sepsis group, nor in animals subjected to Sepsis + TEA.

Figure 4.

Temporary leukocyte adhesion. Numbers of leukocytes adhering temporarily to the (a) sinusoidal and (b) postsinusoidal venolar endothelium 24 hours after induction of sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture and sham procedure respectively. In Sepsis, temporary adherence increased both to the sinusoidal and to the venolar endothelium (* P < 0.05 vs. Sham). The venolar leukocyte adherence was prevented in Sepsis + TEA (# P < 0.05 vs. Sepsis). Data (n = 8 in each group) are displayed as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Liver Injury

In the untreated Sepsis group, serum activity of aspartate aminotransferase rose from 275 ± 101 U/l to 454 ± 108 U/l and alanine aminotransferase activity increased from 97 ± 81 U/l to 185 ± 58 U/l (P < 0.05 vs. Sham). These increases were not significantly affected by TEA. Similarly, histopathologic examination revealed only mild edema formation and patchy pericentral necrosis in sepsis.

Discussion

The knowledge about the hepatic effects of TEA is just the beginning. Recent investigation in the pre- and intraoperative period in human and animals revealed conflicting results with respect to hepatic perfusion [34-38]. All these studies were performed in healthy subjects after a single bolus of epidural local anesthetics. The impact of continuous TEA on liver injury in severe sepsis were not investigated.

Hepatic dysfunction in critical illness is still not completely understood. In the current concept of septic liver injury, two phases of dysfunction are distinguished [1]. The early phase is related to hypoperfusion in the presence of hypovolemia and inadequate cardiac output and resolves fast under supportive therapy. The late and persistent dysfunction is characterized by (supra-) normal tissue perfusion.

In this study, the microvascular liver blood flow was significantly increased in the untreated Sepsis group. In the Sepsis + TEA group, sinusoidal blood flow was normalized compared with the untreated Sepsis group. These changes in hepatic perfusion were not correlated to changes in cardiac output, which remained stable both in the Sepsis group and in the Sepsis + TEA group. Furthermore, the effects of TEA on hepatic tissue blood flow were also not associated with altered sinusoidal vasoregulation or increased sinusoidal recruitment.

Effects of sepsis and TEA on hepatic perfusion

Hepatic macrovascular inflow, although not directly measured in this study, most likely remained constant because cardiac output was not altered. This assumption is supported by numerous studies showing a consistent correlation of cardiac output and macrovascular hepatosplanchnic inflow in sepsis. In human sepsis, macrovascular hepatic inflow rose with cardiac output after therapeutic interventions [39-41]. Both in early and late CLP-sepsis macrovascular hepatic inflow was reduced in parallel with cardiac output [42,43]. Furthermore, in the presence of unchanged or increased cardiac output, hepatic macrovascular inflow also paralleled these changes in cardiac output [42,44,45]. Consequently, the sepsis-induced increase in sinusoidal blood flow and its reversal by TEA are most probably not caused by changes of macrovascular hepatic inflow.

Microvascular tissue perfusion in sepsis, however, is often uncoupled from the systemic circulation. In the clinical therapy of critical illness this dissociation might contribute to the persistent organ failure after hemodynamic stabilization [46]. Earlier studies demonstrated unchanged or even decreased microvascular blood flow in the presence of two to three-fold increased regional blood flow [42,45]. In our study sinusoidal blood flow was increased in the Sepsis group whereas cardiac output was not altered. Intravital microscopy and cardiac output, however, needed to be performed in different sets of animals to minimize interaction between both techniques.

The increase in hepatic microvascular blood flow occurred despite sinusoidal vasoconstriction and consequently was related to increased sinusoidal blood flow velocity. These findings are consistent with an increased arteriolar inflow and are thus the first hint to an impaired hepatic arterial buffer response (HABR) in late polymicrobial sepsis. In HABR, liver arterial blood flow is adapted in response to changes in portal blood flow. Intrahepatic vasodilatation occurs at the level of the preterminal branches of the hepatic artery and is regulated by hydrogen sulfide and adenosine washout by portal blood flow [47,48]. Our results are supported by earlier findings demonstrating impaired HABR and a selective increase in hepatic arterial blood flow in endotoxemia [49,50]. In the Sepsis + TEA group, the sepsis-related increase in liver microvascular blood flow was blunted. It is therefore most likely that the continuous TEA restored HABR. However, this line of interpretation of the presented data is limited by the fact that we did not measure hepatic and portal flow, pressure and resistance separately in this study. Further investigations on the influence of TEA on hepatic blood flow regulation in sepsis and other clinically relevant conditions such as major liver resections are warranted.

In this study, loss of sinusoidal perfusion was not present in the Sepsis group whereas in earlier studies intravital microscopy revealed sinusoidal vasoconstriction and up to 30% reduction in sinusoidal perfusion both in early and late rodent CLP-sepsis [51-53]. Differences in volume resuscitation might partly explain the differing results. In the previous studies an initial bolus of 20 to 60 ml/kg saline solution was administered during 20 to 24 hour CLP-sepsis [53,54]. In our study, volume was infused continuously to a total dose of 144 ml/kg/24 hours. Detection of hypovolemia is often difficult in critical care. In experimental rat sepsis, volume depletion is even harder to exclude. In the present study, mean arterial pressure and heart rate were not significantly affected. Cardiac output remained stable both in untreated rats and in the sepsis + TEA group. The stable systemic hemodynamic parameters combined with stable acid-base-balance and a well-maintained microvascular perfusion in the liver suggests a sufficient resuscitation in this model. This clinically relevant infusion regimen might have prevented loss of perfused sinusoids and contributed to increased tissue blood flow in our study.

Effects of sepsis and TEA on leukocyte adhesion

In the Sepsis + TEA group, sepsis-induced temporary leukocyte adhesion to the venolar endothelium decreased, whereas temporary sinusoidal leukocyte adhesion was not prevented. In contrast, the permanent leukocyte adhesion after 24 hour of sepsis was neither affected in the Sepsis group nor in the Sepsis + TEA group. This observation is in line with prior findings of time-dependent pattern of leukocyte recruitment in rat CLP-sepsis with increased leukocyte adhesion after seven hours and normalized values after 20 hours [55]. In a recent study hepatic neutrophil recruitment declined after eight hours [56]. In contrast to sinusoidal temporary adhesion, hepatic venolar temporary leukocyte adhesion is initiated by selectins [4,57-59].

Reduced venolar rolling in the Sepsis + TEA group might have been related to immune regulatory consequences of splanchnic sympathetic block. The technique of continuous TEA used in this study induced a sympathetic block including hepatic and intestinal sympathetic nerve roots as demonstrated by thermography [26]. This block can be induced as long as 72 hours after catheter placement. There is some evidence of hepatic sympathetic immune regulation supporting this interpretation. Increased sympathetic activity in acute urinary retention results in hepatic inter-cellular adhesion molecule-1 expression [60]. Increased portal norepinephrine in sepsis trigger hepatic release of TNF-α [17,18], which is in turn a prerequisite for venolar temporary leukocyte adhesion [61,62]. Furthermore, TEA has already been shown to reduce temporary adhesion in mesenteric venoles in hemorrhagic shock [63]. Therefore, the abdominal sympathetic block associated with TEA also might have reduced the venolar temporary leukocyte adhesion in sepsis.

Finally, intestinal injury and portal inflow of inflammatory mediators induce secondary hepatic inflammation [1,64,65]. Consequently, the decreased hepatic leukocyte adhesion may be related to the intestinal protection provided by TEA [29,30,66]. The systemic inflammatory response as measured by systemic release of TNF-alpha was not influenced in the Sepsis + TEA group.

Thoracic epidural infusion of local anesthetics is related to a segmental sensoric block, analgesia, and sympathetic block. Each of these aspects, as well as systemically resorbed bupivacaine might contribute to the observed effects of TEA on hepatic microvascular perfusion and leukocyte adhesion. However, the present study does not allow to distinguish or weight these potential mechanisms or to separate primarily hepatic effects from those secondary to intestinal effects of TEA.

Conclusions

In this study, TEA ameliorated the sepsis-induced increase in microvascular liver blood flow and attenuated leukocyte recruitment. These results suggest an altered regulation of liver blood flow and a modified intrahepatic immune response during continuous TEA in sepsis. The consequences of TEA with respect to liver injury, remote organ dysfunction and outcome needs to be further explored.

Key messages

• TEA does not affect cardiac output in late sepsis.

• TEA reverses hepatic hyperperfusion in late sepsis, probably by restoring hepatic arterial buffer response.

• TEA ameliorates intrahepatic temporary leukocyte adhesion in late sepsis.

Abbreviations

ANOVA: analysis of variance; CLP: cecal ligation and puncture; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; H&E: hematoxylin and eosin; HABR: hepatic arterial buffer respsonse; NaCl: sodium chloride; TEA: thoracic epidural anesthesia; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HF contributed to design, funding, data acquisition, statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. FD contributed to the design of the study. CG participated in data acquisition and analysis. SL participated in study planning, data acquisition and statistical analysis. JH contributed to data analysis and to the manuscript. HVA participated in design, funding analysis and manuscript drafting. AWS contributed to funding of the study and participated to planning and statistical analysis. MW contributed to data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. LGF took part in data acquisition and drafting of the manuscript.

See related commentary by Mutz and Vagts, http://ccforum.com/content/13/5/182

Contributor Information

Hendrik Freise, Email: freiseh@uni-muenster.de.

Fritz Daudel, Email: fritz.daudel@insel.ch.

Christina Grosserichter, Email: cgrosserichter@web.de.

Stefan Lauer, Email: lauer@anit.uni-muenster.de.

Juergen Hinkelmann, Email: hinkelmann1971@arcor.de.

Hugo K Van Aken, Email: hva@anit.uni-muenster.de.

Andreas W Sielenkaemper, Email: a.sielenkaemper@caritasklinik.de.

Martin Westphal, Email: martin.westphal@gmx.net.

Lars G Fischer, Email: fischer-l@anit.uni-muenster.de.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Research Society (DFG, Grant Si 629/2-1, Le 625/8-1).

References

- Dhainaut JF, Marin N, Mignon A, Vinsonneau C. Hepatic response to sepsis: interaction between coagulation and inflammatory processes. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S42–47. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch-Puy E. Importance of the liver in systemic complications associated with acute pancreatitis: the role of Kupffer cells. J Pathol. 2007;211:383–388. doi: 10.1002/path.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong YM, Marano MA, Moldawer LL, Wei H, Calvano SE, Kenney JS, Allison AC, Cerami A, Shires GT, Lowry SF. The acute splanchnic and peripheral tissue metabolic response to endotoxin in humans. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1896–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI114651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, McAvoy EF, Lam F, Gill V, de la Motte C, Savani RC, Kubes P. Interaction of CD44 and hyaluronan is the dominant mechanism for neutrophil sequestration in inflamed liver sinusoids. J Exp Med. 2008;205:915–927. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SH, Wing EJ. Neutrophil-Kupffer cell interaction: a critical component of host defenses to systemic bacterial infections. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:239–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannen BH. New insights into the regulation of hepatic blood flow after ischemia and reperfusion. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1448–1457. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derikx JP, Poeze M, van Bijnen AA, Buurman WA, Heineman E. Evidence for intestinal and liver epithelial cell injury in the early phase of sepsis. Shock. 2007;28:544–548. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180644e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbrecht BG, Doyle HR, Clancy KD, Townsend RN, Billiar TR, Peitzman AB. The impact of liver dysfunction on outcome in patients with multiple injuries. Am Surg. 2001;67:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbrecht BG, Zenati MS, Doyle HR, McMichael J, Townsend RN, Clancy KD, Peitzman AB. Hepatic dysfunction increases length of stay and risk of death after injury. J Trauma. 2002;53:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Boekhorst T, Urlus M, Doesburg W, Yap SH, Goris RJ. Etiologic factors of jaundice in severely ill patients. A retrospective study in patients admitted to an intensive care unit with severe trauma or with septic intra-abdominal complications following surgery and without evidence of bile duct obstruction. J Hepatol. 1988;7:111–117. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(88)80514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand F, Hubbard WJ, Choudhry MA, Frink M, Pape HC, Kunkel SL, Chaudry IH. Kupffer cells and their mediators: the culprits in producing distant organ damage after trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:784–794. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Siddiqui J, Remick DG. Mechanisms of mortality in early and late sepsis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5227–5235. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01220-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez O, Viladrich M, Ramirez I, Soley M. Liver injury after an aggressive encounter in male mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1908–1916. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemmer P, Schoonhoven R, Swenberg JA, Bunzendahl H, Thurman RG. Gentle in situ liver manipulation during organ harvest decreases survival after rat liver transplantation: role of Kupffer cells. Transplantation. 1998;65:1015–1020. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804270-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemmer P, Bunzendahl H, Raleigh JA, Thurman RG. Graft survival is improved by hepatic denervation before organ harvesting. Transplantation. 1999;67:1301–1307. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199905270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Yang S, Koo DJ, Ornan DA, Chaudry IH, Wang P. The role of Kupffer cell alpha(2)-adrenoceptors in norepinephrine-induced TNF-alpha production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1537:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Das P, Simms HH, Wang P. Gut-derived norepinephrine plays an important role in up-regulating IL-1beta and IL-10. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Zhou M, Chaudry IH, Wang P. Norepinephrine-induced hepatocellular dysfunction in early sepsis is mediated by activation of alpha2-adrenoceptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1014–1021. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.4.G1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Manipulation of the metabolic response in clinical practice. World J Surg. 2000;24:690–695. doi: 10.1007/s002689910111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, McKee A, Kehlet H, van Zundert A, Sage D, Futter M, Saville G, Clark T, MacMahon S. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anaesthesia: results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziavrangos E, Schug SA. Regional anaesthesia and perioperative outcome. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006;19:521–525. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000245278.22658.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CL, Hurley RW, Anderson GF, Herbert R, Rowlingson AJ, Fleisher LA. Effect of postoperative epidural analgesia on morbidity and mortality following surgery in medicare patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.07.002. discussion 515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodner G, Van Aken H, Hertle L, Fobker M, Von Eckardstein A, Goeters C, Buerkle H, Harks A, Kehlet H. Multimodal perioperative management – combining thoracic epidural analgesia, forced mobilization, and oral nutrition – reduces hormonal and metabolic stress and improves convalescence after major urologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1594–1600. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200106000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendes E, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Hartlage MG, Wirtz S, Reinecke H, Rothenburger M, Scheld HH, Schluter B, Brodner G, Walter M. Reversible cardiac sympathectomy by high thoracic epidural anesthesia improves regional left ventricular function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1283–1290. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1283. discussion 1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiary F, Therapidis P, Dzemali O, Ak K, Ackermann H, Meininger D, Kessler P, Kleine P, Moritz A, Aybek T, Dogan S. Impact of high thoracic epidural anesthesia on incidence of perioperative atrial fibrillation in off-pump coronary bypass grafting: a prospective randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freise H, Anthonsen S, Fischer LG, Van Aken HK, Sielenkamper AW. Continuous thoracic epidural anesthesia induces segmental sympathetic block in the awake rat. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:255–262. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000140253.65577.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan QH, Stekiel TA, Stadnicka A, Bosnjak ZJ, Kampine JP. Region of epidural blockade determines sympathetic and mesenteric capacitance effects in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:604–610. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199509000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AM, Starling JR, Ruscher AE, DeLessio ST, Harms BA. Thoracic versus lumbar epidural anesthesia's effect on pain control and ileus resolution after restorative proctocolectomy. Surgery. 1996;120:688–695. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(96)80018-3. discussion 695-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freise H, Lauer S, Anthonsen S, Hlouschek V, Minin E, Fischer LG, Lerch MM, Van Aken HK, Sielenkamper AW. Thoracic epidural analgesia augments ileal mucosal capillary perfusion and improves survival in severe acute pancreatitis in rats. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:354–359. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudel F, Freise H, Westphal M, Stubbe HD, Lauer S, Bone HG, Van Aken H, Sielenkamper AW. Continuous thoracic epidural anesthesia improves gut mucosal microcirculation in rats with sepsis. Shock. 2007;28:610–614. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31804f584a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S, Freise H, Fischer LG, Singbartl K, Aken HV, Lerch MM, Sielenkamper AW. The role of thoracic epidural analgesia in receptor-dependent and receptor-independent pulmonary vasoconstriction in experimental pancreatitis. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:453–459. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268492.02554.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirag A, Pastor CM, Morel P, Jean-Christophe C, Sielenkamper AW, Guvener N, Mai G, Berney T, Frossard JL, Buhler LH. Epidural anaesthesia restores pancreatic microcirculation and decreases the severity of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:915–920. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sielenkamper AW, Eicker K, Van Aken H. Thoracic epidural anesthesia increases mucosal perfusion in ileum of rats. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:844–851. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitz T, Andreen M, Irestedt L. Haemodynamics and oxygen consumption in the dog during high epidural block with special reference to the splanchnic region. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27:211–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1983.tb01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy WF Jr, Everett GB, Cobb LA, Allen GD. Simultaneous systemic and hepatic hemodynamic measurements during high peridural anesthesia in normal man. Anesth Analg. 1971;50:1069–1077. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197150060-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierhenrich R, Wagner F, Schutz W, Rockemann M, Steffen P, Senftleben U, Gauss A. The effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia on hepatic blood flow in patients under general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1331–1337. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181966e6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagts DA, Iber T, Puccini M, Szabo B, Haberstroh J, Villinger F, Geiger K, Noldge-Schomburg GF. The effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia on hepatic perfusion and oxygenation in healthy pigs during general anesthesia and surgical stress. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1824–1832. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000087062.94268.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivarajan M, Amory DW, Lindbloom LE. Systemic and regional blood flow during epidural anesthesia without epinephrine in the rhesus monkey. Anesthesiology. 1976;45:300–310. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Rosenberg PH, Takala J. Effect of dopamine-induced changes in splanchnic blood flow on MEGX production from lidocaine in septic and cardiac surgery patients. Shock. 2002;18:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Takala J. Effects of dopamine on systemic and regional blood flow and metabolism in septic and cardiac surgery patients. Shock. 2002;18:8–13. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank N, Michel C, Haertel C, Lenhart A, Welte M, Meier-Hellmann A, Spies C. N-acetylcysteine increases liver blood flow and improves liver function in septic shock patients: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3799–3807. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebrand LB, Krejci V, Banic A, Erni D, Wheatley AM, Sigurdsson GH. Dynamic study of the distribution of microcirculatory blood flow in multiple splanchnic organs in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3233–3241. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CS, Yang S, Song GY, Lomas J, Wang P, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas signaling prevents hepatic injury and improves organ blood flow during sepsis. Surgery. 2001;130:339–345. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Tait SM, Chaudry IH. Sustained elevation of norepinephrine depresses hepatocellular function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1535:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuszies G, Radermacher P, Vogt J, Wachter U, Weber S, Schoaff M, Georgieff M, Barth E. Effect of increased cardiac output on hepatic and intestinal microcirculatory blood flow, oxygenation, and metabolism in hyperdynamic murine septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2332–2338. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000182817.20977.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince C. The microcirculation is the motor of sepsis. Crit Care. 2005;9(Suppl 4):S13–19. doi: 10.1186/cc3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert N, Cantre D, Eipel C, Vollmar B. H2S contributes to the hepatic arterial buffer response and mediates vasorelaxation of the hepatic artery via activation of K(ATP) channels. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G1266–1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90484.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautt WW. The 1995 Ciba-Geigy Award Lecture. Intrinsic regulation of hepatic blood flow. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:223–233. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-3-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuse T, Brienza N, Revelly JP, O'Donnell CP, Boitnott JK, Robotham JL. Alternations in liver hemodynamics in an intact porcine model of endotoxin shock. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1106–1114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer ER, Mentha G, Schwieger IM, Morel DR. Sequential changes in the splanchnic circulation during continuous endotoxin infusion in sedated sheep: evidence for a selective increase of hepatic artery blood flow and loss of the hepatic arterial buffer response. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993;147:251–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CC, Martignoni A, Leonis MA, Ondiveeran HK, Fox-Robichaud AE, Waltz SE. Ron receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent hepatic neutrophil recruitment and survival benefit in a murine model of bacterial peritonitis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1585–1593. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318170a8c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer G, Urakami H, Specian RD, Stokes KY, Granger DN. Platelet recruitment in the murine hepatic microvasculature during experimental sepsis: role of neutrophils. Microcirculation. 2006;13:89–97. doi: 10.1080/10739680500466343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SA, Paxian M, Ashburn JH, Clemens MG, Huynh T. Kupffer cell ablation improves hepatic microcirculation after trauma and sepsis. J Trauma. 2005;58:740–749. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000158246.74816.18. discussion 749–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Ba ZF, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Hepatocellular dysfunction persists during early sepsis despite increased volume of crystalloid resuscitation. J Trauma. 1992;32:389–396. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199203000-00018. discussion 396-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Xie M, Spitzer JA. Hepatic neutrophil sequestration in early sepsis: enhanced expression of adhesion molecules and phagocytic activity. Shock. 1994;2:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhi L, Moochhala SM, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulates leukocyte trafficking in cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:894–905. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmar B, Glasz J, Menger MD, Messmer K. Leukocytes contribute to hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury via intercellular adhesion molecule-1-mediated venular adherence. Surgery. 1995;117:195–200. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(05)80085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintman D, Li X, Thorlacius H. Important role of P-selectin for leukocyte recruitment, hepatocellular injury, and apoptosis in endotoxemic mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:56–62. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.1.56-62.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, Fisher MA, Simmons CA, Hoover JL, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Increased P-selectin gene expression in the liver vasculature and its role in the pathophysiology of neutrophil-induced liver injury in murine endotoxin shock. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:288–296. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HJ, Lin BR, Lee HS, Shun CT, Yang CC, Lai TY, Chien CT, Hsu SM. Sympathetic vesicovascular reflex induced by acute urinary retention evokes proinflammatory and proapoptotic injury in rat liver. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1005–1014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00223.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Jochum W, Georgiev P, Moritz W, Graf R, Clavien PA. Kupffer cell-dependent TNF-alpha signaling mediates injury in the arterialized small-for-size liver transplantation in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4598–4603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600499103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick AL, Rullo J, Beaudin S, Liaw P, Fox-Robichaud AE. Hepatic leukocyte recruitment in response to time-limited expression of TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G663–672. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00070.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs J, Schmidt DK, Korsukewitz I, Kamin B, Habazettl H, Schafer M, Welte M. Effects of thoracic epidural anaesthesia on intestinal microvascular perfusion in a rodent model of normotensive endotoxaemia. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2094–2101. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2426-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie Y, Wolf R, Anderson DC, Granger DN. Nitric oxide modulates gut ischemia-reperfusion-induced P-selectin expression in murine liver. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H520–526. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Shigemori H, Oho K, Sakai T, Tayama C, Masumoto H, Sato M, Tanikawa K. Hepatic artery hemodynamic responsiveness to altered portal blood flow in normal and cirrhotic livers. Radiology. 1996;200:793–798. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.3.8756933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai K, Kotake Y, Satoh T, Serita R, Takeda J, Morisaki H. Epidural anesthesia retards intestinal acidosis and reduces portal vein endotoxin concentrations during progressive hypoxia in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:263–269. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200102000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]