Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Impaired cardiovascular function in diabetes is partially attributed to pathological overexpression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in cardiovascular tissues. We examined whether the hyperglycemia-induced increased expression of iNOS is protein kinase C-β2 (PKCβ2) dependent and whether selective inhibition of PKCβ reduces iNOS expression and corrects abnormal hemodynamic function in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Cardiomyocytes and aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) from nondiabetic rats were cultured in low (5.5 mmol/l) or high (25 mmol/l) glucose or mannitol (19.5 mmol/l mannitol + 5.5 mmol/l glucose) conditions in the presence of a selective PKCβ inhibitor, LY333531 (20 nmol/l). Further, the in vivo effects of PKCβ inhibition on iNOS-mediated cardiovascular abnormalities were tested in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

RESULTS

Exposure of cardiomyocytes to high glucose activated PKCβ2 and increased iNOS expression that was prevented by LY333531. Similarly, treatment of VSMC with LY333531 prevented high glucose–induced activation of nuclear factor κB, extracellular signal–related kinase, and iNOS overexpression. Suppression of PKCβ2 expression by small interference RNA decreased high-glucose–induced nuclear factor κB and extracellular signal–related kinase activation and iNOS expression in VSMC. Administration of LY333531 (1 mg/kg/day) decreased iNOS expression and formation of peroxynitrite in the heart and superior mesenteric arteries and corrected the cardiovascular abnormalities in STZ-induced diabetic rats, an action that was also observed with a selective iNOS inhibitor, L-NIL.

CONCLUSIONS

Collectively, these results suggest that inhibition of PKCβ2 may be a useful approach for correcting abnormal hemodynamics in diabetes by preventing iNOS mediated nitrosative stress.

Cardiovascular complications are recognized to be the major cause of morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes (1). Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, increased glucose flux through the polyol pathway, formation of advanced glycation end products (AGE), and increased levels of oxidative and nitrosative stress are some of the mechanisms believed to be involved in the etiology of these complications (2–4). Increasing evidence now implicates the abnormal activation of PKCβ2, secondary to increased formation of diacylglycerol (DAG) by hyperglycemia, in a number of cardiovascular diabetes complications (3,5). Studies from our lab (6,7) and elsewhere (5) have found preferential increases in expression and/or activation of the PKCβ2 isoform in cardiac and vascular tissues of diabetic animals. Inhibition of the activity of PKCβ has been shown to result in amelioration of diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy in human patients (8,9) and was recently reported to improve cardiac function in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (10). However, the mechanisms by which activation of this PKC isoform exerts adverse effects in cardiovascular tissues remain unclear.

A seminal study suggested that normalizing mitochondrial oxidative stress could prevent hyperglycemia-induced activation of PKC, increased flux through the polyol pathway, and formation of AGE (2), underscoring the importance of oxidative stress in the etiology of diabetes complications. Previous studies from our lab have demonstrated significant improvements in cardiovascular function of STZ-induced diabetic rats treated with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine in parallel with inhibition of PKCβ2 activation (6) and reduction in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-mediated nitrosative stress (11). Specifically, we found that improvements in cardiac performance, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), heart rate, pressor responses to vasoactive agents, and endothelial function were associated with improvements in oxidative and nitrosative stress in the heart and arteries of STZ-induced diabetic rats (11–13). However, it remains unclear whether the increase in iNOS-mediated nitrosative stress is an independent manifestation of hyperglycemic injury or is linked to the activation of PKCβ2.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that diabetes-induced activation of PKCβ2 causes cardiovascular abnormalities via induction of iNOS. First, we investigated whether PKCβ2 induces iNOS expression in cardiac and vascular tissues and the mechanisms involved therein, using the selective PKCβ inhibitor LY333531 or PKCβ2 siRNA. Second, we investigated the functional significance of this in vivo by determining the effects of treatment of STZ-induced diabetic rats with LY333531 on iNOS expression, nitrotyrosine formation, and hemodynamic abnormalities. Our results suggest that induction of iNOS, and consequently increased nitrosative stress, is one of the mechanisms by which PKCβ2 leads to cardiovascular complications in diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study design and induction of diabetes.

This study conforms to the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines on the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and was approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee. Forty-eight male Wistar rats weighing between 280 and 300 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Quebec, and allowed to acclimatize to the local vivarium. They were randomly divided into six equal groups: control, control treated with LY333531 or L-NIL, diabetic, and diabetic treated with LY333531 or L-NIL. Diabetes was induced by a single tail vein injection of 60 mg/kg STZ whereas control animals received equal volume of citrate buffer. The presence of diabetes was confirmed by hyperglycemia (>20 mmol/l) 72 h after STZ administration. Plasma glucose was measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay kit (Roche Diagnostics) and a Beckman Glucose Analyzer. One week after the induction of diabetes, animals received vehicle or the selective PKCβ inhibitor, LY333531 (1 mg/kg/day) (14), or the selective iNOS inhibitor, L-NIL (3 mg/kg/day), by oral gavage. LY333531 is a potent and specific inhibitor of PKC with an IC50 of ∼5 nmol/l for the β-isozymes, which is 100-fold lower than for the α, γ, or δ-isoforms of PKC (15). Similarly, L-NIL is a potent and relatively selective iNOS inhibitor with an IC50 of 5.9 μmol/l for iNOS compared with an IC50 of 138 μmol/l for eNOS and 35 μmol/l for nNOS (16). A dose of 3 mg/kg/day was selected based on our previous study in which we were able to inhibit iNOS-mediated NO production in heart tissues from STZ-induced diabetic rats (17). After 3 weeks of treatment, each animal was surgically prepared for measurement of MABP, heart rate, and pressor responses to methoxamine.

Surgical procedures and hemodynamic measurements.

Animals were surgically prepared as described previously (18). For more information, please refer to the online appendix (available in an online appendix at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/early/2009/07/08/db09-0432/suppl/DC1).

Collection of tissue samples.

After hemodynamic measurements, animals were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). The heart and superior mesenteric arteries (SMA) were immediately removed and placed in ice-cold Krebs solution (120 mmol/l NaCl, 5.9 mmol/l KCl, 25 mmol/l NaHCO3, 11.5 mmol/l glucose, 1.2 mmol/l NaH2PO4, 1.2 mmol/l MgCl2, and 2.5 mmol/l CaCl2) containing 0.1 μmol/l water-soluble dexamethasone to prevent induction of iNOS in vitro. The tissues were cleaned of all adherent tissue, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C for Western blot measurements. Some tissue sections were preserved in neutral buffered formalin for immunohistochemistry experiments.

Preparation of isolated rat ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Ca2+-tolerant cardiomyocytes were isolated as described previously (19) (see online appendix).

Preparation and culture of rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells.

Please see online appendix.

PKCβ2 siRNA studies in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells.

Small interference RNA (siRNA) specific to rat PKCβ2 was used to knock down the expression of PKCβ2 in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). The PKCβ2 siRNA, which was custom made by Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA), consisted of a pool of three target-specific 19–25 nitrotyrosine siRNA duplexes. The transfection reagent, medium, and scrambled siRNA were also purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech. For optimal siRNA transfection, the manufacturer's protocol was followed. Briefly, VSMCs were seeded in a six-well plate and cultured in 2 ml antibiotic-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS until the cells were 60–80% confluent (∼36 h). On the day of transfection, cells were washed with transfection medium and incubated with 1 ml of transfection reagent containing 60 pmols of either MOCK (scrambled) or rat-specific PKCβ2 siRNA oligonucleotides for 16 h. The medium was then supplemented with 1 ml of fresh DMEM (containing 2× FBS and antibiotics) for another 24 h. At this point, the cells were washed with warm PBS and treated with either low or high glucose containing DMEM for another 48 h in the presence or absence of various drugs as mentioned in the Results section.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

Please see online appendix.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification of iNOS and nitrotyrosine immunostain in the heart and superior mesenteric artery sections.

Please see online appendix.

Measurement of oxidative stress in VSM cells.

Please see online appendix.

Statistical analysis.

All values are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) software program was used for statistical analysis. For all results, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of LY333531 on PKCβ2 and iNOS expression in cardiomyocytes and diabetic hearts.

We previously have shown increased expression of iNOS in hearts (18) and cardiomyocytes (17) isolated from diabetic rats. In the present study, we examined whether incubation of normal cardiomyocytes in high glucose increases iNOS expression and, if so, whether this could be prevented by treatment with the PKCβ inhibitor, LY333531. Treatment of cardiomyocytes with high glucose (25 mmol/l) for 18 h had no effect on total levels of PKCβ2 but significantly increased levels of Thr641-phosphorylated PKCβ2 (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylation of Thr641 is crucial for the appropriate subcellular localization and catalytic function of PKCβ2 and is often used as an index of PKCβ2 activation (20). On the other hand, exposure of cardiomyocytes to mannitol (19.5 + 5.5 mmol/l glucose) to determine any effects because of hyperosmolarity did not alter levels of either Thr641- phosphorylated or total PKCβ2 compared with cells treated with low glucose (data not shown). Treatment of cardiomyocytes with LY333531 prevented the high glucose–induced increase in the phosphorylation of PKCβ2 without affecting the expression of total PKCβ2 (Fig. 1A). Further, high glucose also increased the expression of iNOS in isolated cardiomyocytes, and this was prevented by pretreatment with LY333531 (Fig. 1B). Similarly, there was a significant increase in the expression of iNOS and in levels of Thr641 phosphophorylated PKCβ2 without any change in total PKCβ2 in hearts from untreated diabetic rats. Treatment of diabetic rats with LY333531 significantly reduced levels of phosphorylated PKCβ2 as well as iNOS expression without affecting these parameters in age-matched control rat hearts (Fig. 2).

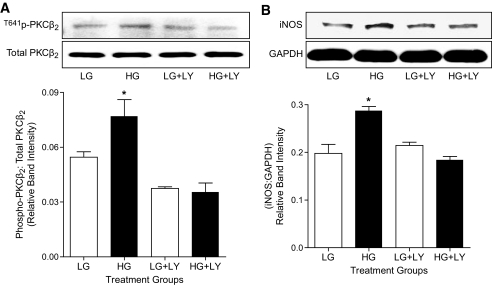

FIG. 1.

LY333531 treatment decreases PKCβ2 phosphorylation and iNOS in cardiomyocytes. A: (top) Representative Western blot showing phospho-PKCβ2 (Thr641) in comparison with total PKCβ2 in cardiomyocytes exposed to low glucose (LG; 5.5 mmol/l) or high glucose (HG; 25 mmol/l) for 18 h in the absence or presence of LY333531 (LY333531; 20 nmol/l). (bottom) The densitometric values of phospho-PKCβ2 were normalized to corresponding total PKCβ2 densitometric values and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with low glucose, low glucose + LY333531, and high glucose + LY333531 groups. B: Representative Western blot showing iNOS expression, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) as a loading control, in cardiomyocytes exposed to low (5.5 mmol/l) or high glucose (25 mmol/l) for 18 h in the presence or absence of LY333531 (20 nmol/l). iNOS densitometric values were normalized to their corresponding GAPDH densitometric values and expressed as relative band intensities. All data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 3 to 5 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with low glucose, low glucose + LY333531, and high glucose + LY333531 groups.

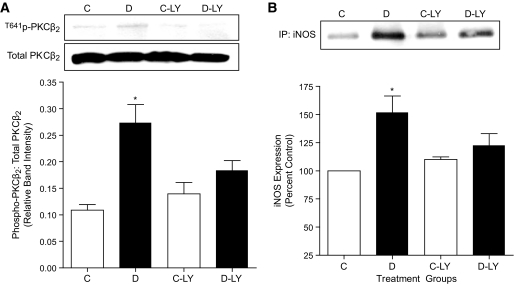

FIG. 2.

Effect of LY333531 (LY)on PKCβ2 phosphorylation and iNOS expression in control and diabetic heart tissues. A: Representative Western blot showing phospho-PKCβ2 (Thr641) in comparison with total PKCβ2 expression levels in ventricular tissues of control (C), diabetic (D), control LY333531-treated (C-LY), and diabetic LY333531-treated (D-LY) rats. The densitometric values of phospho-PKCβ2 were normalized to corresponding total PKCβ2 expression levels and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared with C, C-LY, and D-LY groups. B: Representative Western blot showing iNOS expression in the ventricular tissues of C, D, C-LY, and D-LY groups. iNOS protein was immunoprecipitated from heart ventricular tissue lysates using mouse monoclonal anti-iNOS antibody. Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated complex were loaded on to the gels and were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Densitometric data are expressed as percentage of control. All values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with C, C-LY, and D-LY groups.

Effect of LY333531 on PKCβ2 and iNOS expression in VSMC and superior mesenteric arteries.

We next determined whether iNOS expression was induced in rat aortic VSMC cultured in high glucose as well as in superior mesenteric arteries from diabetic rats. Similar to that observed in diabetic rat hearts, there was a significant increase in the expression of iNOS in mesenteric arteries from untreated diabetic rats. Treatment of diabetic rats with LY333531 significantly reduced the expression of iNOS in mesenteric arteries (Fig. 3A). Further, incubation of VSMC in high glucose (Fig. 3B) but not mannitol (Fig. 1B, available in an online appendix) for 36 h also significantly increased iNOS expression. Activation of PKCβ2, as measured by increased phosphorylation of Thr641 was significantly elevated in high glucose conditions (Fig. 3C). Treatment of VSMC with LY333531 not only reduced the phosphorylation of PKCβ2 (Fig. 3C), consistent with inhibition of its activation, but also prevented the increase in iNOS expression (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Effect of LY333531 (LY) on PKCβ activation and iNOS expression in isolated superior mesenteric arteries and cultured rat aortic VSMC. A: Representative Western blot showing iNOS expression in superior mesenteric arteries of control (C), diabetic (D), control LY333531-treated (C-LY), and diabetic LY333531-treated (D-LY) groups. iNOS was immunoprecipitated from superior mesenteric artery tissue lysates using mouse monoclonal anti-iNOS antibody. Densitometric data are expressed as percentage of control. All values are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (C), control LY333531-treated (C-LY), and diabetic LY333531-treated (D-LY) groups; #P < 0.05 compared with control and control LY333531-treated. B: Representative Western blot showing iNOS expression, with GAPDH shown as a loading control, in aortic VSMC exposed to low glucose (LG; 5.5 mmol/l) and high glucose (HG; 25 mmol/l) for 36 h in the presence or absence of LY333531 (20 nmol/l). iNOS densitometric values were normalized to their corresponding GAPDH densitometric values and expressed as relative band intensities. All data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with low glucose, low glucose + LY333531, and high glucose + LY333531 groups. C: Representative Western blot showing phospho- and total PKCβ2 expression in VSMC exposed to low (5.5 mmol/l) or high glucose (25 mmol/l) for 36 h in the presence or absence of LY333531 (20 nmol/l). The densitometric values of phospho-PKCβ2 were normalized to corresponding total PKCβ2 expressionlevels and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with low glucose, low glucose + LY333531, and high glucose + LY333531 groups.

Induction of iNOS is PKCβ2 dependent in VSM cells.

Our experiments so far indicated that exposure of VSMC and cardiomyocytes to high glucose leads to an increase in iNOS expression that is prevented by the PKCβ inhibitor, LY333531. To determine whether PKCβ2 is specifically required for induction of iNOS, we suppressed its expression in VSMC using rat-specific PKCβ2 siRNA and again exposed the cells to low and high glucose conditions. Although we were not able to suppress the expression of PKCβ2 completely, a reduction in PKCβ2 protein expression of ∼50% (Fig. 4A) not only reduced the phosphorylation of PKCβ2 to levels found in normal glucose but also prevented the increase in expression of iNOS in VSMC exposed to high glucose (Fig. 4B) while having no effect on iNOS expression in VSMC incubated in low glucose. Levels of other PKC isoforms, including PKCα, β1, δ, and ε, were unaffected by PKCβ2 siRNA treatment (Fig. 6, available in an online appendix).

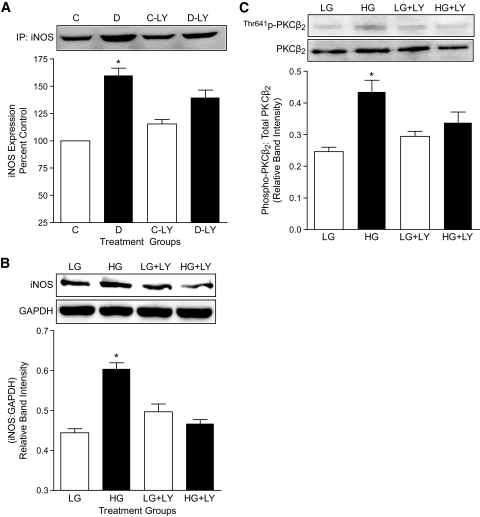

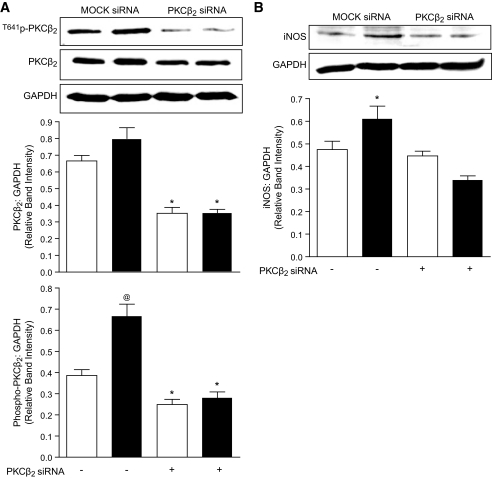

FIG. 4.

Effect of PKCβ2 suppression on PKCβ2 expression and activation and iNOS expression in VSMC. Cells were transfected with either MOCK or PKCβ2-specific siRNA and exposed to low or high glucose for 36 h. A: Representative Western blot showing total and phospho-PKCβ2 expression, with GAPDH as a loading control in VSMC treated with MOCK or PKCβ2 siRNA. The densitometric values of PKCβ2 were normalized to corresponding total GAPDH densitometric values and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4). Open bars represent low glucose–treated and dark bars represent high glucose–treated VSMC. *P < 0.05 compared with MOCK siRNA–treated VSMC exposed to low glucose or high glucose conditions, @P < 0.05 compared with all other groups. B: Representative Western blot showing iNOS expression, with GAPDH as a loading control in VSMC treated with MOCK or PKCβ2 siRNA. The densitometric values of iNOS were normalized to corresponding total GAPDH densitometric values, and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4). Open bars represent low glucose–treated and dark bars represent high glucose–treated VSMC. *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups.

FIG. 6.

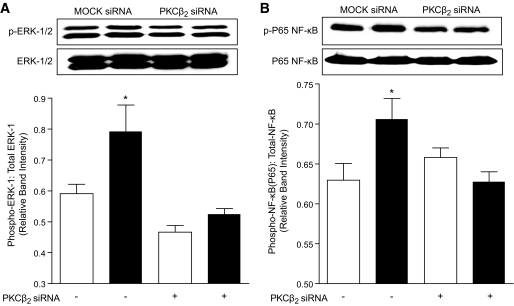

Effect of PKCβ2 silencing on ERK1/2 and NF-κB activation in VSMC. A: Representative Western blot showing phospho-ERK-1 (Thr202) and phospho-ERK-2 (Tyr204) in comparison with total ERK1/2 in VSMC treated with MOCK or PKCβ2 siRNA. The densitometric values of phospho-ERK-1 were normalized to corresponding total ERK-1 densitometric values, and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). Open bars represent low glucose–treated and dark bars represent high glucose–treated VSMC. *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups. B: Representative Western blot showing phospho-NF-κB P65 subunit (Ser536) in comparison with total NF-κB P65 in VSMC treated with MOCK or PKCβ2 siRNA. The densitometric values of phospho-NF-κB P65 were normalized to corresponding total NF-κB P65 densitometric values and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). Open bars represent low glucose–treated and dark bars represent high glucose–treated VSMC. *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups.

Induction of iNOS by PKCβ2 involves extracellular signal–related kinase 1/2 and nuclear factor-κB activation in VSMC.

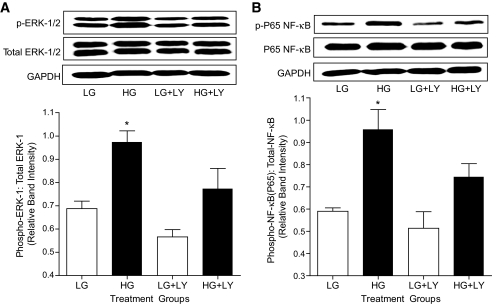

Because extracellular signal–related kinase (ERK)1/2 has been reported to mediate increased expression of iNOS in vascular smooth muscle via the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway (21,22), we next investigated whether ERK was activated in cells exposed to high glucose. Incubation of VSMC in high glucose (Fig. 5A) but not mannitol (Fig. 1C, available in an online appendix) increased ERK activity as measured by increased phosphorylation of both ERK-1 and ERK-2 at Thr202 and Tyr204, respectively. Further, treatment of VSMC exposed to high glucose with LY333531 significantly prevented ERK activation (Fig. 5A). Similarly, in superior mesenteric arteries from untreated diabetic rats, we found a significant increase in ERK activity, which was prevented by treatment with LY333531 (Fig. 4, available in an online appendix).

FIG. 5.

Effect of LY333531 (LY) on ERK1/2 and NF-κB activation in VSMC. A: Representative Western blot showing phospho-ERK-1 (Thr202) and phospho-ERK-2 (Tyr204) in comparison with total ERK1/2 and with GAPDH as a loading control in VSMC exposed to low glucose (LG; 5.5 mmol/l) or high glucose (HG; 25 mmol/l) for 36 h in the presence or absence of LY333531 (20 nmol/l). The densitometric values of phospho ERK-1 were normalized to corresponding total ERK-1densitometric values and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups. B: Representative Western blot showing phospho-NF-κB P65 subunit (Ser536) in comparison with total NF-κB P65 and with GAPDH as a loading control in VSMC exposed to low (5.5 mmol/l) and high (25 mmol/l) glucose for 36 h in the presence or absence of LY333531 (20 nmol/l). The densitometric values of phospho-NF-κB were normalized to corresponding total phospho-NF-κB P65densitometric values and the relative band intensities are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups.

The signaling events that lead to NF-κB activation involve phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteolytic degradation of IκB-α from its inactive trimeric complex of IκB/p65/p50 in the cytosol. This is followed by translocation of the active dimer (p65/p50) to the nucleus, where it binds to specific regions within the promoter to initiate iNOS message transcription (23). To assess NF-κB activation, we measured the phosphorylation of Ser536 on the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Exposure of VSMC to high glucose but not mannitol increased the phosphorylation of the NF-κB p65 subunit, and this was inhibited by pretreatment with LY333531 (Fig. 5B). The expression of total NF-κB p65 subunit was similar in all groups except the mannitol group where it was increased. However, this increase was not reduced by treatment with LY333531, indicating that the hyperosmotic signal leading to increased synthesis of NF-κB P65 protein is not PKCβ2 dependent (Fig. 1D, available in an online appendix).

To confirm the specific involvement of the PKCβ2 isoform in the activation of ERK1/2 and NF-κB, we incubated PKCβ2 siRNA–transfected VSMC in high glucose. VSMC in which PKCβ2 was suppressed failed to show activation of ERK 1/2 and NF-κB on exposure to high glucose levels (Fig. 6). These data clearly suggest that PKCβ2 is the predominant isoform involved in the activation of NF-κB by ERK1/2 in VSMC exposed to high glucose.

LY333531 inhibition of PKCβ reduces oxidative stress in VSMC.

VSMC exposed to high glucose produced a significant increase in the generation of superoxide anion free radicals as measured by dihydroerthidium fluorescence. Treatment of VSMC with LY333531 not only inhibited the high glucose–induced increase in oxidative stress but also reduced superoxide anion production in low glucose, suggesting an inherent antioxidant effect of the inhibitor (Fig. 5, available in an online appendix).

In vivo effects of LY333531 on PKCβ2, iNOS, and nitrotyrosine expression in the heart and mesenteric arteries.

Rats were made diabetic with STZ and were treated with LY333531 (1 mg/kg/day) or L-NIL (3 mg/kg/day) by oral gavage for 3 weeks. Previous studies have shown the effectiveness of these doses of the inhibitors in STZ-induced diabetic rats (17,18,24). At the end of the treatment period, untreated diabetic rats had significantly elevated blood glucose levels and reduced body weights compared with control rats, which were not altered by LY333531 or L-NIL treatment (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

General characteristics of rats after 3 weeks of LY333531 and L-NIL treatment

| Parameters | C | D | C-LY | C-LNIL | D-LY | D-LNIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | ||||||

| Initial | 278 ± 4.2 | 253 ± 5.0 | 282 ± 6.2 | 292 ± 6.3 | 253 ± 4.2 | 270 ± 6.0* |

| Final | 423 ± 5.3 | 360 ± 8.2* | 425 ± 6.2 | 428 ± 11.9 | 372 ± 9.5* | 372 ± 13.2* |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 8.3 ± 0.23 | 31.1 ± 0.8* | 8.5 ± 0.22 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 31.8 ± 0.75* | 27.5 ± 0.8* |

All data expressed are means ± SE.

*Different from C, C-LY, and C-LNIL groups. C, control rats; D, diabetic rats; LY, LY333531.

As explained in previous sections, heart and mesenteric arteries from untreated diabetic rats showed increased phosphorylation of PKCβ2 and iNOS expression, which was significantly inhibited by treatment with LY333531 (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). Further, immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased expression of iNOS in the cardiomyocytes of heart sections and the medial and advential layers of superior mesenteric artery sections (Fig. 2, available in an online appendix) from untreated diabetic rats. In superior mesenteric arteries, as opposed to the dense immunostaining in the medial and advential layers, very little staining was observed in the tunica intima or endothelium, suggesting that the major source of iNOS is the media and adventia. Semiquantitative analysis of iNOS immunostain in the photomicrographs suggests a reduction of iNOS expression by ∼50% in both the heart and superior mesenteric arteries of diabetic rats treated with LY333531. Similarly, immunohistochemical analysis of nitrotyrosine, an indirect marker of peroxynitrite formation, indicated an increase in the nitration of proteins in the hearts and superior mesenteric arteries (Fig. 3, available in an online appendix) of untreated diabetic rats. As shown, there is a substantial increase in the levels of nitrotyrosine in the diabetic heart (>60%) and arteries (>40%) compared with those in control rats. Treatment with LY333531 significantly decreased the formation of nitrotyrosine in diabetic rats compared with untreated diabetic rats both in superior mesenteric arteries and in ventricular muscle.

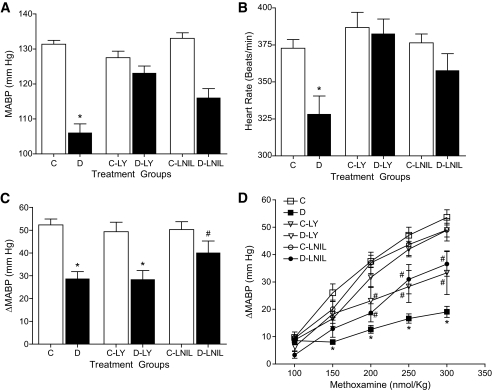

Effect of PKCβ and iNOS inhibition on cardiovascular function in diabetic rats.

We previously have shown that direct inhibition of iNOS by L-NIL in vivo significantly improved cardiac performance, pressor responsiveness, and endothelial function in STZ-induced diabetic rats (17,18). In the present study, we examined the in vivo effects of PKCβ inhibition on iNOS-mediated cardiovascular abnormalities in these animals. Four weeks after the induction of diabetes, untreated diabetic rats showed significantly lower MABP (Fig. 7A) and heart rate (Fig. 7B) compared with age-matched control rats. Treatment with LY333531 or L-NIL significantly prevented the depression in both MABP and heart rate in diabetic rats without affecting these parameters in control animals. Further, administration of bolus doses of methoxamine (100–300 nmoles/kg) increased MABP in both control and diabetic rats in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with the corresponding age-matched control rats, responses to methoxamine were significantly attenuated in untreated diabetic rats (Fig. 7D). However, treatment of diabetic rats with LY333531 or L-NIL significantly augmented pressor responses to methoxamine while having no effect in control rats. Endothelial function was tested using a single bolus dose of l-NAME. As shown (Fig. 7C), untreated diabetic rats exhibited attenuated pressure response (ΔMABP) to l-NAME suggesting an impairment of endothelial function. Treatment with L-NIL but not LY333531 significantly improved endothelial function in diabetic rats.

FIG. 7.

Effect of 3 weeks of LY333531 (LY) (1 mg/kg/day) or L-NIL (3 mg/kg/day) treatment on hemodynamic parameters in freely moving conscious rats. Data represent means ± SE (n = 8). A: Effect of LY333531 or L-NIL on MABP. *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups. B: Effect of LY333531 or L-NIL on heart rate. *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups. C: Effect of LY333531 or L-NIL on endothelial function as measured by the change in blood pressure (ΔMABP) in response to a single intravenous bolus dose of l-NAME (10 mg/kg) in control (C) and diabetic (D) rats. *P < 0.05 compared with their respective control groups. #P < 0.05 compared with diabetic and diabetic + LY333531 groups. D: Effect of LY333531 or L-NIL on pressor responses to bolus doses of methoxamine (100–300 nmoles/kg). *P < 0.05 compared with all other groups; #P < 0.05 compared with diabetic rats.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have led to the identification of multiple hyperglycemia-induced alterations in metabolism and signaling that have been linked to activation of PKC and an eventual increase in oxidative/nitrosative stress in diabetes (2–4). It remains unclear whether the increase in nitrosative stress, which is implicated in the etiology of diabetes secondary complications (4), is an independent manifestation of hyperglycemic injury or is linked to the activation of PKC. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that high glucose–induced activation of PKCβ2 increases iNOS-mediated nitrosative stress leading to cardiovascular abnormalities. The results of our investigation provide clear evidence supporting this hypothesis because treatment with LY333531 or PKCβ2 siRNA inhibited the increased expression of iNOS in cardiovascular tissues and LY333531 administration in vivo protected diabetic animals from the deleterious cardiovascular effects of hyperglycemia. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that PKCβ2 is essential for high glucose–induced activation of ERK1/2 and NF-κB and subsequent induction of iNOS and that the protective effects of PKCβ2 inhibition in diabetes are associated with inhibition of iNOS-mediated peroxynitrite formation.

High glucose is known to increase de novo synthesis of DAG, which is a potent activator of PKC in many cellular types (25,26). Elevated DAG levels have been reported in various tissues including the heart, retina, and kidney of diabetic rats (3,27). Furthermore, it is now established that increased levels and activity of specific isoforms of PKC occurs in the cardiovascular system in diabetes, and evidence suggests that abnormal activation of the PKC system contributes to the development of diabetes cardiovascular complications (3,5,28). However, understanding the PKC signaling system is complicated by the presence of a large number of isoforms each with varying cellular distribution and sometimes opposing functions (29). The isoform that has been most frequently implicated in diabetes cardiovascular complications (6,28,30) is PKCβ2 (5). Studies from our lab and elsewhere have reported increased membrane levels of PKCβ2 in hearts (6) and superior mesenteric arteries (31) from diabetic rats. Consistent with this, in the present study, we found evidence for increased activation of PKCβ2 both in the heart and superior mesenteric artery from diabetic rats as well as in cardiomyocytes and VSMC exposed to high glucose. Additionally, we found increased expression of PKCε but not of the α, β1, or δ isoforms in VSMC exposed to high glucose (Fig. 6, available in an online appendix).

Activation of PKC by pharmacological activators such as phorbol esters or PKC overexpression has been reported to upregulate cytokine-induced increases in iNOS and NO production in various cell types (32–34). These studies, most of which were conducted in noncardiovascular cell types, suggested the involvement of a variety of PKC isoforms in the induction of iNOS in response to proinflammatory cytokines (32–34). On the other hand, high glucose–mediated increases in PKC have been variously reported to both inhibit (35) and to potentiate (36) cytokine-induced increases in iNOS expression in VSMC. Although the reason for the discrepancy between previous studies is not clear, our data show that inhibition of PKCβ attenuates iNOS expression both in isolated cardiomyocytes and VSMC exposed to high glucose in culture and in the heart and arteries of diabetic rats. This was confirmed using both pharmacological inhibition and silencing of PKCβ2 in VSMC. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the specific involvement of PKCβ2 in the induction of iNOS in cardiovascular tissues and, most importantly, its significance in the development of diabetic cardiovascular complications.

The mechanism by which PKCβ2 induces the expression of iNOS in cardiovascular tissues likely involves ERK1/2 and NF-κB, because the suppressive effect of LY333531 on iNOS expression was accompanied by inhibition of ERK and NF-κB activation. Previous studies have shown that inhibition of ERK activation, either by selective chemical inhibitors or by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, attenuates NF-κB activation and iNOS expression in VSMC stimulated with cytokines (21,22). Several cell types are known to increase ERK and NF-κB activity when exposed to high glucose, and persistently higher levels of NF-κB have been reported in target organs such as the retina, the heart, and the kidney of diabetic rats (37,38). In agreement with these observations, we also found increased ERK activity in arteries (Fig. 4, available in an online appendix) of STZ-induced diabetic rats. Taken together, our data and the results of previous studies support the view that high glucose–induced activation of PKCβ2 increases iNOS expression by ERK activation of NF-κB (21,22,37).

Although it is unclear how PKCβ2 activates the ERK–NF-κB pathway, the mechanism may involve the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) secondary to PKC activation (2,39). In the present study, exposure of VSMC to high glucose produced a significant increase in ROS that was prevented by treatment with LY333531. The evidence that LY333531 inhibits ERK and NF-κB at the same time that it decreases ROS production suggests the possibility that ROS are central to activation of this pathway. Indeed, ROS are known to directly activate NF-κB, a pleiotropic oxidant–sensitive transcriptional factor, as well as ERK (40,41).

Studies from our lab and elsewhere have demonstrated increased levels of oxidative and nitrosative stress in STZ-induced diabetic rats, and treatment with either an antioxidant or iNOS inhibitor has reduced nitrotyrosine levels, an indirect marker of peroxynitrite formation (11,18). Peroxynitrite has been shown to cause severe hypotension, profound vasodilatation, cardiac depression, and multiple organ failure in various models of septic shock (42). Increasing evidence suggests that many of the cardiovascular abnormalities in diabetic rats can be prevented by inhibiting nitrosative stress caused by peroxynitrite (43,44). For instance, previous studies from our lab showed that inhibition of peroxynitrite using antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine improves cardiac performance, MABP, and heart rate in STZ-diabetic rats (6,11).

Increasing evidence now suggests that iNOS and nitrosative stress are critical determinants in the development of diabetes complications in humans (4,45,46). Increased generation of NO occurs in patients with type 1 diabetes and is associated with enhanced peroxynitrite production and lipid peroxidation (47). Furthermore, a correlation between increased plasma NOx levels and endothelial dysfunction, lower blood pressure, and sympathetic nerve dysfunction in type 1 diabetes has also been found (47,48).

In the present study, inhibition of nitrosative stress by both LY333531 and L-NIL was associated with improvements in MABP and heart rate as well as pressor responses to vasoactive agents in STZ-diabetic rats. However, the change in MABP in response to acute administration of l-NAME was improved in L-NIL– but not LY333531-treated rats. The reason for this is unclear. However, under normal conditions as seen in control rats, administration of l-NAME has been reported to increase MABP as a result of an increase in total peripheral resistance caused by both decreased NO production (largely from eNOS) and potentiation of the actions of ET-1 (49). In diabetes, the ET-1–mediated increase in ΔMABP may be compromised by increased iNOS activity and in the presence of L-NIL, MABP increases. On the other hand, it is possible that LY333531 treatment did not improve the ΔMABP at least in part because of its inhibitory actions on ET-1 (50). It is also likely that other unknown factors contribute to the depressed ΔMABP in response to l-NAME in diabetic rats both in the absence and presence of the inhibitors.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate that PKCβ2 is an obligatory mediator of nitrosative stress and that LY333531 significantly reduced the formation of iNOS and improved cardiovascular abnormalities in STZ-diabetic rats. Moreover, hyperglycemia-induced activation of PKCβ2 is antecedent to increases in superoxide, ERK1/2, NF-κB, and iNOS expression in cardiovascular tissues, whereas inhibition of this pathway suppresses key signaling events that lead to increased nitrosative stress. Collectively, our data suggest that inhibition of PKCβ2 may be a useful approach for correcting abnormal hemodynamics in diabetes by preventing iNOS-mediated nitrosative stress.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants to K.M.M. and J.H.M. from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of BC & Yukon. P.R.N. is a recipient of Doctoral Research Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and Senior Graduate Studentship from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the Keystone Symposia on Molecular and Cellular Biology: Complications of Diabetes and Obesity, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 24 February–1 March 2009.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M: Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature 2000;404:787–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koya D, King GL: Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes 1998;47:859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacher P, Obrosova IG, Mabley JG, Szabo C: Role of nitrosative stress and peroxynitrite in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Emerging new therapeutical strategies. Curr Med Chem 2005;12:267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoguchi T, Battan R, Handler E, Sportsman JR, Heath W, King GL: Preferential elevation of protein kinase C isoform β-II and diacylglycerol levels in the aorta and heart of diabetic rats: differential reversibility to glycemic control by islet cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992;89:11059–11063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia Z, Kuo KH, Nagareddy PR, Wang F, Guo Z, Guo T, Jiang J, McNeill JH: N-acetylcysteine attenuates PKC-β2 overexpression and myocardial hypertrophy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:770–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin G, Liu Y, MacLeod KM: Regulation of muscle creatine kinase by phosphorylation in normal and diabetic hearts. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009;66:135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Toto RD, McGill JB, Hu K, Anderson PW: The effect of ruboxistaurin on nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2686–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiello LP, Davis MD, Girach A, Kles KA, Milton RC, Sheetz MJ, Vignati L, Zhi XE: Effect of ruboxistaurin on visual loss in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2006;113:2221–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arikawa E, Ma RC, Isshiki K, Luptak I, He Z, Yasuda Y, Maeno Y, Patti ME, Weir GC, Harris RA, Zammit VA, Tian R, King GL: Effects of insulin replacements, inhibitors of angiotensin, and PKC-β's actions to normalize cardiac gene expression and fuel metabolism in diabetic rats. Diabetes 2007;56:1410–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagareddy PR, Xia Z, MacLeod KM, McNeill JH: N-acetylcysteine prevents nitrosative stress-associated depression of blood pressure and heart rate in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47:513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardell AL, MacLeod KM: Evidence for inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression and activity in vascular smooth muscle of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001;296:252–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagareddy PR, Xia Z, McNeill JH, MacLeod KM: Increased expression of iNOS is associated with endothelial dysfunction and impaired pressor responsiveness in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;289:H2144–H2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii H, Jirousek MR, Koya D, Takagi C, Xia P, Clermont A, Bursell SE, Kern TS, Ballas LM, Heath WF, Stramm LE, Feener EP, King GL: Amelioration of vascular dysfunctions in diabetic rats by an oral PKC-β inhibitor. Science 1996;272:728–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkey JL, Campanale KM, O'Bannon DD, Cramer JW, Farid NA: Disposition of LY333531, a selective protein kinase C-β inhibitor, in the Fischer 344 rat and beagle dog. Xenobiotica 2002;32:1045–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallinan EA, Tsymbalov S, Dorn CR, Pitzele BS, Hansen DW, Jr, Moore WM, Jerome GM, Connor JR, Branson LF, Widomski DL, Zhang Y, Currie MG, Manning PT: Synthesis and biological characterization of L-N(6)-(1-iminoethyl)lysine 5-tetrazole-amide, a prodrug of a selective iNOS inhibitor. J Med Chem 2002;45:1686–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soliman H, Craig GP, Nagareddy P, Yuen VG, Lin G, Kumar U, McNeill JH, Macleod KM: Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in induction of ρ-A expression in hearts from diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res 2008;79:322–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagareddy PR, McNeill JH, MacLeod KM: Chronic inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase ameliorates cardiovascular abnormalities in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2009;611:53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin G, Craig GP, Zhang L, Yuen VG, Allard M, McNeill JH, MacLeod KM: Acute inhibition of ρ-kinase improves cardiac contractile function in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Res 2007;75:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H, Sasaki T, Maeda K, Koya D, Kashiwagi A, Yasuda H: Protein kinase C-β selective inhibitor LY333531 attenuates diabetic hyperalgesia through ameliorating cGMP level of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Diabetes 2003;52:2102–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang B, Brecher P, Cohen RA: Persistent activation of nuclear factor-κB by interleukin-1β and subsequent inducible NO synthase expression requires extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:1915–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang B, Xu S, Hou X, Pimentel DR, Brecher P, Cohen RA: Temporal control of NF-κB activation by ERK differentially regulates interleukin-1β-induced gene expression. J Biol Chem 2004;279:1323–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra D, Jackson EB, Ramana KV, Kelley R, Srivastava SK, Bhatnagar A: Nitric oxide prevents aldose reductase activation and sorbitol accumulation during diabetes. Diabetes 2002;51:3095–3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nonaka A, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, Yamashiro K, Miyamoto K, Nishiwaki H, Honda Y, Ogura Y: PKC-β inhibitor (LY333531) attenuates leukocyte entrapment in retinal microcirculation of diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:2702–2706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee TS, Saltsman KA, Ohashi H, King GL: Activation of protein kinase C by elevation of glucose concentration: proposal for a mechanism in the development of diabetic vascular complications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989;86:5141–5145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 26.Wolf BA, Williamson JR, Easom RA, Chang K, Sherman WR, Turk J: Diacylglycerol accumulation and microvascular abnormalities induced by elevated glucose levels. J Clin Invest 1991;87:31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okumura K, Akiyama N, Hashimoto H, Ogawa K, Satake T: Alteration of 1,2-diacylglycerol content in myocardium from diabetic rats. Diabetes 1988;37:1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakasaki H, Koya D, Schoen FJ, Jirousek MR, Ways DK, Hoit BD, Walsh RA, King GL: Targeted overexpression of protein kinase C-β2 isoform in myocardium causes cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:9320–9325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellor H, Parker PJ: The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J 1998;332(Pt 2):281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Way KJ, Isshiki K, Suzuma K, Yokota T, Zvagelsky D, Schoen FJ, Sandusky GE, Pechous PA, Vlahos CJ, Wakasaki H, King GL: Expression of connective tissue growth factor is increased in injured myocardium associated with protein kinase C-β2 activation and diabetes. Diabetes 2002;51:2709–2718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueed I, Zhang L, Macleod KM: Role of the PKC/CPI-17 pathway in enhanced contractile responses of mesenteric arteries from diabetic rats to α-adrenoceptor stimulation. Br J Pharmacol 2005;146:972–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CC, Wang JK, Chen WC, Lin SB: Protein kinase C-ç mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric-oxide synthase expression in primary astrocytes. J Biol Chem 1998;273:19424–19430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CC, Wang JK, Lin SB: Antisense oligonucleotides targeting protein kinase C-α, -βI, or -Δ but not -ç inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages: involvement of a nuclear factor κB-dependent mechanism. J Immunol 1998;161:6206–6214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hortelano S, Genaro AM, Bosca L: Phorbol esters induce nitric oxide synthase and increase arginine influx in cultured peritoneal macrophages. FEBS Lett 1993;320:135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishio E, Watanabe Y: Glucose-induced down-regulation of NO production and inducible NOS expression in cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells: role of protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;229:857–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pacheco ME, Beltran A, Redondo J, Manso AM, Alonso MJ, Salaices M: High glucose enhances inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. Role of protein kinase C-βII. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;538:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramana KV, Friedrich B, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava SK: Activation of nuclear factor-κB by hyperglycemia in vascular smooth muscle cells is regulated by aldose reductase. Diabetes 2004;53:2910–2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yerneni KK, Bai W, Khan BV, Medford RM, Natarajan R: Hyperglycemia-induced activation of nuclear transcription factor κB in vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes 1999;48:855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konishi H, Tanaka M, Takemura Y, Matsuzaki H, Ono Y, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y: Activation of protein kinase C by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to H2O2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:11233–11237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daou GB, Srivastava AK: Reactive oxygen species mediate Endothelin-1-induced activation of ERK1/2, PKB, and Pyk2 signaling, as well as protein synthesis, in vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;37:208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J: NF-κB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol 2006;72:1493–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parrillo JE: Pathogenetic mechanisms of septic shock. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1471–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuzzocrea S, Riley DP, Caputi AP, Salvemini D: Antioxidant therapy: a new pharmacological approach in shock, inflammation, and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Rev 2001;53:135–159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nassar T, Kadery B, Lotan C, Da'as N, Kleinman Y, Haj-Yehia A: Effects of the superoxide dismutase-mimetic compound tempol on endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2002;436:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceriello A, Mercuri F, Quagliaro L, Assaloni R, Motz E, Tonutti L, Taboga C: Detection of nitrotyrosine in the diabetic plasma: evidence of oxidative stress. Diabetologia 2001;44:834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mabley JG, Soriano FG: Role of nitrosative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in diabetic vascular dysfunction. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2005;3:247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoeldtke RD: Nitrosative stress in early type 1 diabetes. David H. P. Streeten Memorial Lecture. Clin Auton Res 2003;13:406–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ceriello A, Piconi L, Esposito K, Giugliano D: Telmisartan shows an equivalent effect of vitamin C in further improving endothelial dysfunction after glycemia normalization in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1694–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu C, Engels K, Baylis C: Endothelin modulates the pressor actions of acute systemic nitric oxide blockade. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6:1476–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yokota T, Ma RC, Park JY, Isshiki K, Sotiropoulos KB, Rauniyar RK, Bornfeldt KE, King GL: Role of protein kinase C on the expression of platelet-derived growth factor and endothelin-1 in the retina of diabetic rats and cultured retinal capillary pericytes. Diabetes 2003;52:838–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]