Abstract

The synthesis, biochemical, and biological evaluation of a systematic series of 2-triazole derivatives of 5’-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine (Sal-AMS) are described as inhibitors of aryl acid adenylating enzymes (AAAE) involved in siderophore biosynthesis by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Structure activity relationships revealed a remarkable ability to tolerate a wide range of substituents at the 4-position of the triazole moiety and a majority of the compounds possessed subnanomolar apparent inhibition constants. However, the in vitro potency did not always translate into whole cell biological activity against M. tuberculosis, suggesting intrinsic resistance, due to limited permeability, plays an important role in the observed activities. Additionally, the well-known valence tautomerism between 2-azidopurines and their fused tetrazole counterparts led to an unexpected facile acylation of the purine N-6 amino group.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, tuberculosis, adenylation inhibitor, siderophore biosynthesis, mycobactin, nonribosomal peptide synthetase

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by the slow growing bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), is the leading cause of death due to a bacterial pathogen.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least one third of the world’s population is infected with a latent form of this organism and that about five to ten percent of these individuals will progress to the active form of the disease during their lifetime.2 Further, co-infection with HIV is especially deadly and serves as a trigger to convert latent TB into an active transmissible infection. The current drug therapy known as DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short-course), requires 6–9 months of drug treatment and results in overall cure rate of approximately 85% (global average).2 However, the emergence of multidrug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB), coupled with the lack of any new antitubercular agents in over four decades, provides a clear motivation for the development of new chemotherapeutic agents to treat drug-resistant strains, target latent, non-replicating bacilli, and shorten the duration of treatment.3

In almost all living organisms, iron is an essential cofactor that is required for numerous essential biochemical processes. Invasive pathogens are dependent on iron obtained from the human host; however, the concentration of free iron in human serum and body fluids is 10−24 M, a concentration that is too low to support bacterial colonization and growth.4 In order to fulfill their iron needs many bacteria synthesize, secrete, and reimport small molecule iron chelators known as siderophores that abstract iron from host proteins.5, 6 M. tuberculosis as well as many other Gram negative and some Gram positive bacteria synthesize structurally related aryl-capped siderophores, as shown in Figure 1A.7, 8 Installation of the aryl moiety during the biosynthesis of these aryl-capped siderophores is performed by stand-alone aryl acid adenylation enzymes (AAAE, see Figure 1B). Given the documented importance of many siderophores for virulence, lack of human AAAE homologues, available structural information on AAAE’s, and knowledge of the AAAE enzyme mechanism, several groups including ours have reported on the synthesis of potent AAAE bisubstrate inhibitors.9–12 The initial lead compound 5′-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine (Sal-AMS, 4, Figure 1C) has emerged as a promising inhibitor of diverse bacterial AAAE’s and was shown to possess promising whole-cell activity toward both M. tuberculosis and Yersinia sp..9, 13 Extensive structure activity relationships of Sal-AMS have systematically explored the aryl,14 linker,10, 15–17 glycosyl,13 and nucleobase18 domains (Figure 1C). These results have provided a comprehensive understanding of the minimal structural requirements to maintain activity and also have served to define positions amenable to modification of this promising series of antibacterial agents. In general, the aryl, linker, and glycosyl domains only tolerated conservative modifications, while the nucleobase domain exhibited substantial flexibility and provides the greatest opportunity to modulate physiochemical and drug disposition properties. Molecular dynamics simulations of the AAAE from Mtb revealed substantial plasticity in the nucleoside binding pocket allowing binding of Sal-AMS derivatives with large substituents at C-2 of the purine.18 The ability to tolerate these bulky C-2 substituents was not evident based on the co-crystal structure of an AAAE with a bound acyladenylate.19 Significantly, 2-Ph-Sal-AMS 5 (Figure 1C) was the most potent inhibitor yet identified with Kiapp of 0.27 nM and exceptionally potent antitubercular activity under iron deficient conditions (MIC99 = 0.049 µM).18

Figure 1.

(A) Structure of representative aryl-capped siderophores. (B) Enzyme mechanism catalyzed by AAAE’s. AAAE binds aryl acid 1 and ATP and catalyzes their condensation to form an intermediate acyladenylate 2 that remains tightly bound to the active site. In a second half reaction, the AAAE catalyzes the transfer of the acyl group (blue) onto a nucleophilic sulfur atom of an aryl carrier domain to provide 3 with the release of AMP. (C) 5’-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine (Sal-AMS, 4) is a bisubstrate inhibitor that mimics the acyladenylate 2, but replaces the labile acylphosphate moiety with a stabile acylsulfamate group (pink). The modular scaffold of Sal-AMS can be disconnected into four subunits: aryl (blue), linker (pink), glycosyl (black), and nucleobase (black).

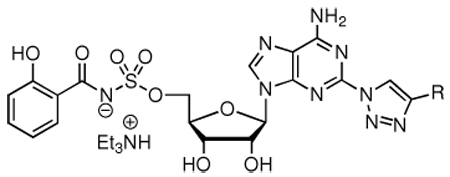

Herein we report our continued efforts to further explore modification of the C-2 position of the purine moiety of Sal-AMS 4 with a systematic series of 4-substituted 1,2,3-triazoles, inspired from the work of Van Calenbergh, as isosteres of the C-2 phenyl ring of 5.20 These triazole analogues ideally position the 4-substituent of the 1,2,3-triazole moiety into a flexible channel in the AAAE, which is directed toward the solvent exposed surface. Additionally, we show that the well-known azide-tetrazole valence tautomerism of 2-azidoadenosine derivatives influences adenosine acylation at N-6 and we have provided a clear mechanistic rationale for this fascinating reactivity.

Results

Chemistry

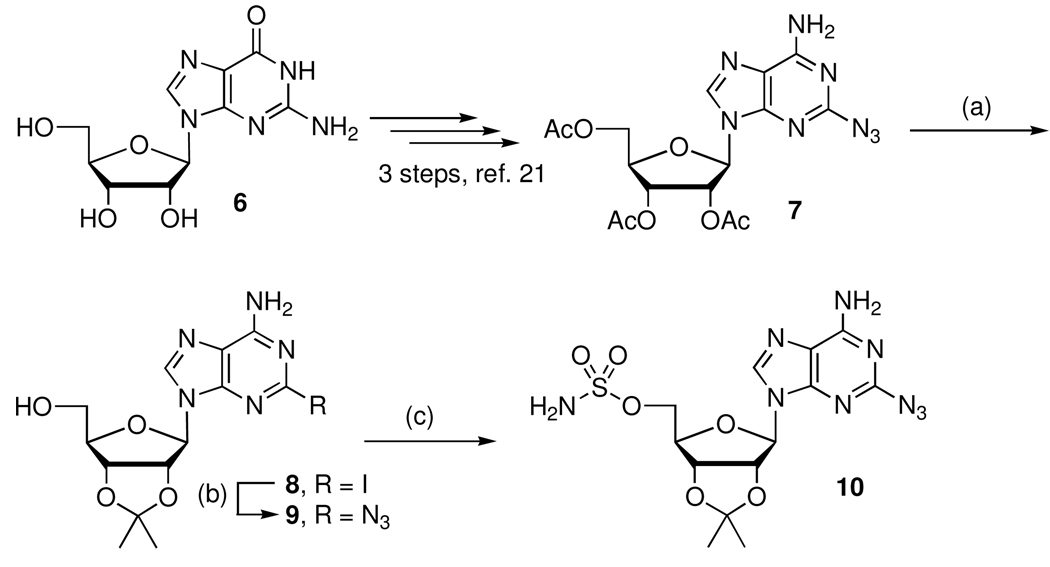

The synthesis of the intermediate 2-azido-5’-O-sulfamoyladenosine 10 began from guanosine, which was elaborated to 2-azidoadenosine 7 as described by Hata and co-workers (Scheme 1).21 Methanolysis of 7 followed by acetonide protection furnished 9, which was sulfamoylated to provide 10.22 Copper catalyzed coupling of 2-iodoadenosine derivative 823 with sodium azide provided an alternate route to compound 9.24

Scheme 1a.

aReaction Conditions: (a) (i) 7 N NH3 in MeOH, (ii) p-TSA, dimethoxypropane, acetone, 48%; (b) NaN3 (1.2 equiv), CuSO4·5H2O (0.2 equiv), sodium ascorbate (0.2 equiv), l-proline (0.2 equiv), H2O/t-BuOH (1:1), 65 °C, 16 h, 52%; (c) sulfamoyl chloride, DMA, 67%.

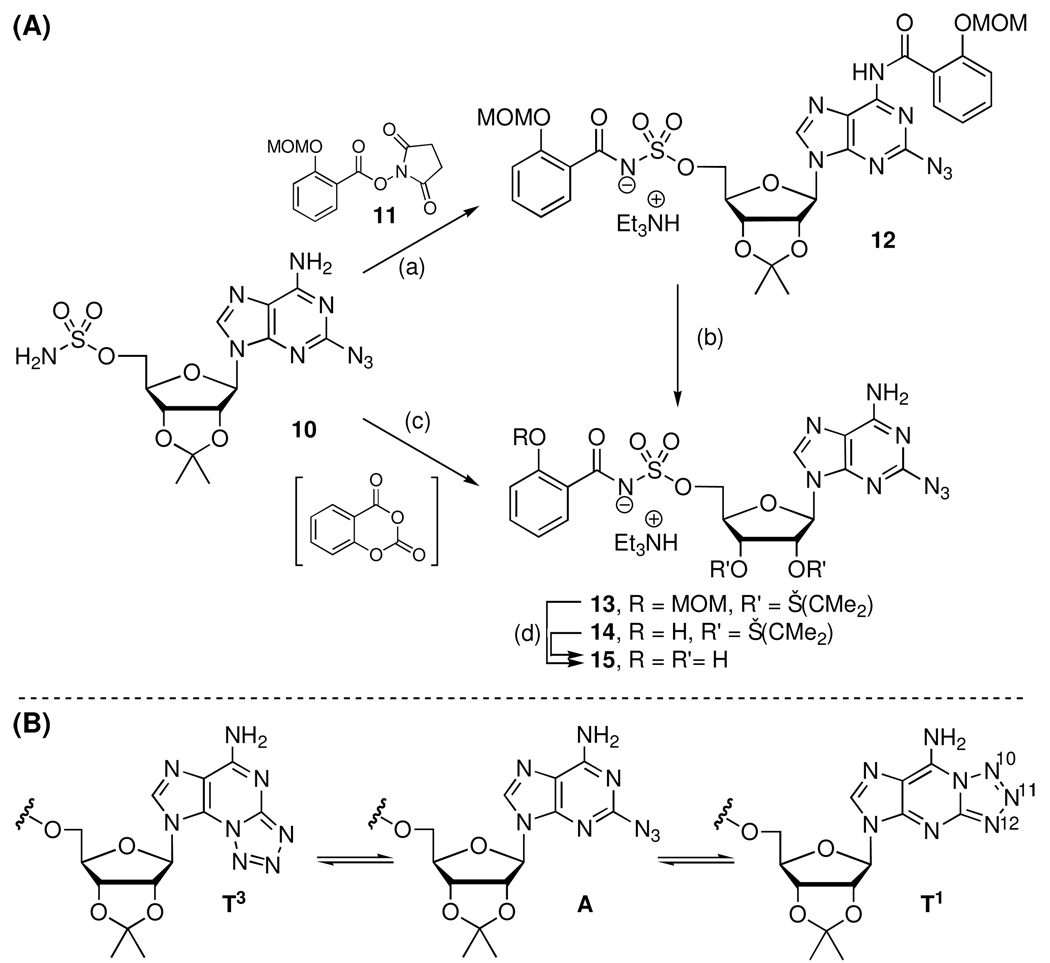

Coupling of 10 with the N-hydroxysuccinimidyl (NHS) ester of salicylic acid 1113 using modified Castro-Pichel coupling conditions employing Cs2CO3 afforded the biascylated compound 12 in 53% yield due to competitive acylation at N-6.25 Regioselective ammonolysis of the N-6 salicyl group was successively achieved with methanolic ammonia to provide 13 in a modest 61% yield. The stability of the acylsulfamate linkage of 12 under these conditions was noteworthy. Deprotection of the MOM acetal and isopropylidene protecting groups was accomplished with 80% aqueous TFA to provide the key intermediates 2-azido-Sal-AMS 15.

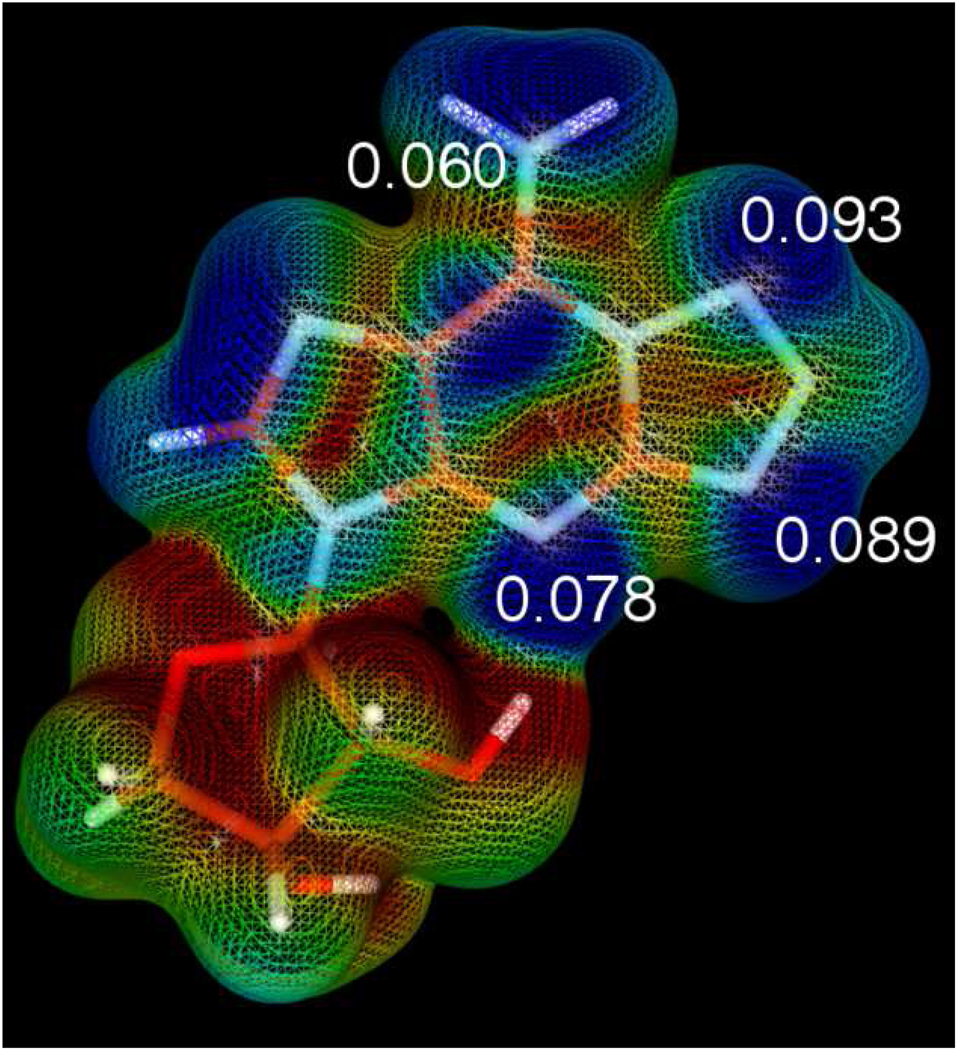

The observation that 10 undergoes acylation at N-6 was intriguing as we had not observed this side-reaction in any of our previously described nucleobase-modified analogues.18 The well-known valence tautomerism between 2-azidopurines (A) and the corresponding fused tetrazoles (T1 and T3) (Scheme 2B) accounts for this apparent unique reactivity.26 Tetrazole (CH2N4) has been described as a nucleophilic catalyst for the regio- and chemoselective N-6 acylation of adenosine, thus we propose that the tetrazole tautomer (T1) is responsible for the undesired acylation.27 These valence tautomers are easily distinguished by the diagnostic chemical shift of H-8.28 Proton NMR of 10 showed an 83:17:0 mixture of A:T1:T3 in CD3OD. Czarnecki demonstrated that the equilibrium is dependent on pH, solvent polarity and temperature; however, the most dominant effect is pH with the tetrazole valence tautomer favored almost exclusively at high pH (>11) such as under the basic reaction conditions employed (Cs2CO3, DMF).26 Indeed, the condensed Fukui function (f-) based on Mulliken population analysis revealed that the most nucleophilic atom in fused tetrazole T1 is N-10 (see Figure 2 and Experimental Section). Acylation at N-10 of fused tetrazole T1, followed by an intramolecular N-N acyl shift to the N-6 amino group, provides a potential mechanism for the experimentally observed product 12.

Scheme 2a.

aReaction Conditions: (a) 11 (2.2 equiv), Cs2CO3 (3.0 equiv), DMF, 12 h, 53%; (b) 7 N NH3 in MeOH, 60 °C, 3h, 61%; (c) Salicylic acid, CDI, DBU, MeCN, 60 °C, 2h, 93%; (d) 80% aq TFA, 62% (from 14) or 54% (over 2 steps from 12).

Figure 2.

Relative nucleophilicity of a fused T1-tetrazole. Qualitatively, the most nucleophilic regions are shown in blue, while the least nucleophilic are red. Additionally calculation of the local Fukui function (f-) using atomic charges determined by Mulliken population was completed. The values of the function for the four most nucleophilic atoms are shown in the figure. N-10 possesses the highest nucleophilicity with a f- value of 0.093. The figure is a surface representation generated from the Fukui function (F-), plotted on the 0.01 isodensity surface of a truncated derivative of T1 tetrazole, whereby the C5’ hydroxymethyl group was replaced with a hydrogen atom.

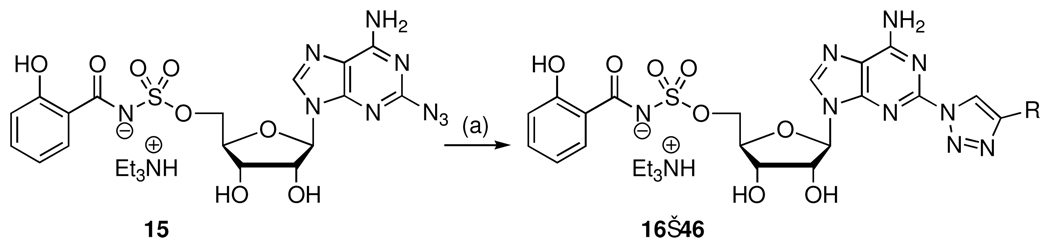

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we hypothesized that less basic conditions, which disfavor the tetrazole valence tautomer would circumvent the undesired N-6 acylation. Consequently, we used the complimentary conditions developed by Tan and co-workers employing DBU and salicylic acid to provide 14 in 93% yield without any observed acylation at N-6.9 Subsequent, TFA mediated deprotection afforded 15. Following the successful optimized synthesis of the key 2-azido-Sal-AMS intermediate 15, Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition in methanol at room temperature with a panel of 30 alkynes selected to systematically explore van der Waal and electrostatic interactions provided exclusively the 1,4-substituted triazole analogues 16–45 in moderate to high yields (Scheme 3).29,30

Scheme 3a.

aReaction Conditions: (a) terminal alkyne (3.0 equiv), Cu(OAc)2 (0.1 equiv) sodium ascorbate (0.1 equiv), MeOH, 25 °C, 16 h, 44–92%.

Enzyme Inhibition

Enzyme assays were performed at 37 °C with recombinant MbtA expressed in E. coli in a buffer of 75 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 250 µM salicylic acid, 10 mM ATP, and 1 mM PPi. The initial rates of pyrophosphate exchange (≤ 10% reaction) were monitored using an enzyme concentration (typically 5–10 nM) by measuring the amount of [32P]ATP formed after addition of [32P]PPi. The enzyme concentration was determined by active-site titration with inhibitor 4. The apparent inhibition constants (Kiapp) were determined by fitting the concentration-response plots to the Morrison equation (eq 1, see Experimental Section) since the inhibitor exhibited tight-binding behavior (Kiapp ≤ 100 × [E]). This class of inhibitors has been shown to exhibit reversible and competitive inhibition toward MbtA with respect to both salicylic acid and ATP. All of the Kiapp values reported are uncorrected for the supersaturating substrate concentrations (salicylic acid held at 250 µM or 120 × KM; ATP held at 10 mM, or 55 × KM) and represent an upper limit of the true dissociation constants.

Initially, a small series of 4-substituted triazoles derivatives with small substituents was investigated including hydroxymethyl 16, methoxycarbonyl 17, ethoxycarbonyl 18 and n-propyl 19. These compounds were 2–7 times more potent than the parent Sal-AMS 4. Encouraged by these results, a systematic series of linear and branched alkyl derivatives 20–28 was prepared and evaluated for enzyme inhibition with substituents ranging from C4–C12. The activity followed a parabolic relationship with potency increasing with chain length from C3 to C6 and then decreasing from C6 to C12. Notably, n-hexyl 22 was the most potent triazole derivative evaluated and 23-fold more potent than 4. Cycloalkyl derivatives 29–31 were approximately 12–21 more potent than 4. Interestingly, incorporation of unsaturation in cyclohexenyl 32 and phenyl 33 led to a 5- and 10-fold loss of potency respectively, relative to cyclohexyl 31.

A methyl scan of phenyl derivative 33 was performed with 34–36 to define the steric requirements in the C-2 binding pocket. The SAR from this showed that substitution at all positions was well tolerated and the additional methyl group led to a 3–7 fold improvement in potency relative to phenyl 33. Next, three series of aryl derivatives were evaluated incorporating a combination of hydrogen bond donor and/or acceptor capabilities including aminophenyl derivatives 37–39, pyridyl analogues 40–42, and hydroxyphenyl compounds 43–45. The SAR from these three series was relatively flat, demonstrating that electrostatic interactions do not play a significant role and that the SAR is primarily driven by steric considerations.

Molecular Modeling

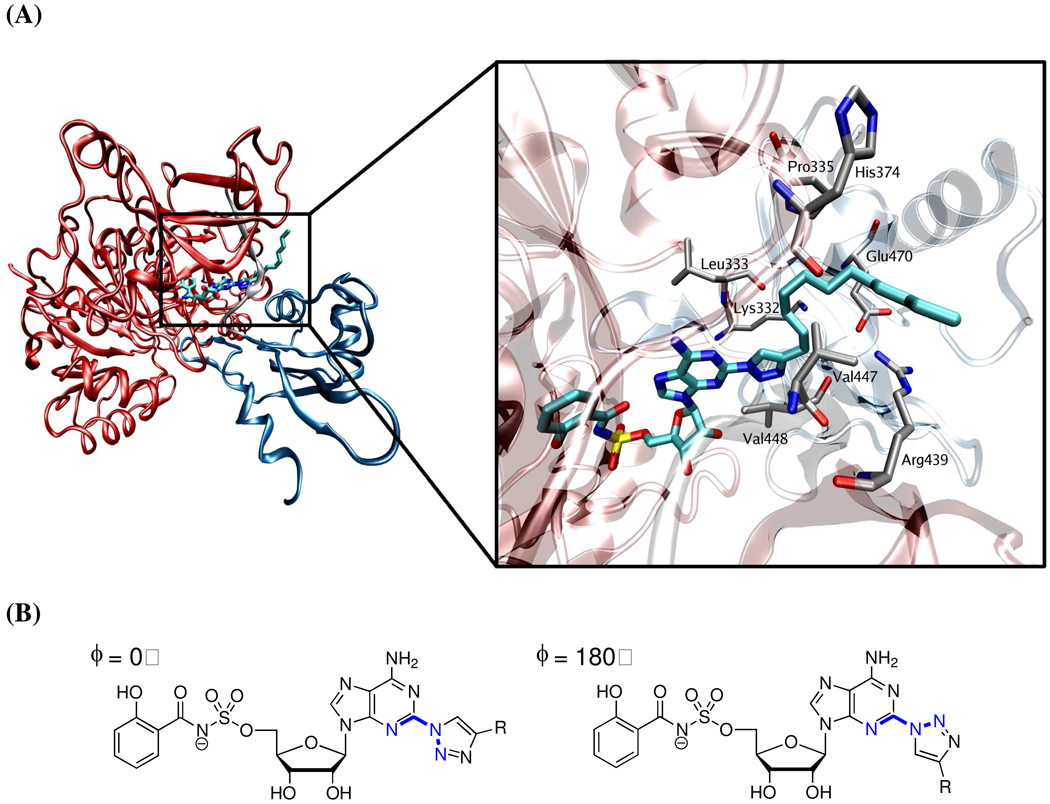

In order to gain insight into the observed SAR, docking studies of all ligands were performed using a previously described MbtA homology model (see Experimental Section). The docked poses of most compounds allowed favorable positioning of the Sal-AMS core in the active site, retaining most of the significant interactions with the active site while positioning the triazole group in the interdomain region (Figure 3A).10,18 The docked conformations showed the triazole was essentially coplanar with the purine ring with a dihedral angle defined by N3-C2-N1’-N2’ very close to 0° (see Figure 3B). Compounds 16–18 that contain relatively small 4-substituents on the triazole as well as n-alkyl derivatives 19–26 allowed excellent positioning of the Sal-AMS core, maintaining all key hydrogen bonds observed for Sal-AMS. Notably, the C8–C12 chains in 24–26 were able to reach the solvent exposed surface. However, cyclohexyl 31, cyclohexenyl 32 and all phenyl derivatives 33–45, exhibited docked poses with some degree of distortion in the Sal-AMS core. Based on previous molecular dynamics studies, which show modest plasticity in this interdomain region of the protein, we expect a small conformation change in the protein to alleviate ligand strain.18 The relatively flat SAR observed for aryl derivatives 33–45 is consistent with the relatively nonpolar binding pocket and docking failed to show any H-bond interactions between the protein and nitrogen or oxygen atoms in pyridyl, hydroxyphenyl, or aminophenyl groups in 33–45. Derivative 16 was the only one whose docked conformation exhibited hydrogen bonds with the active site residue, through its hydroxyl group to Lys332 and Glu470.

Figure 3.

(A) Docked pose of compound 26 in the active site of MbtA in the predicted binding mode (Glide). The protein is reduced to a ribbon diagram with the N-terminal in red (residues 1–443), C-terminal in blue (residues 455–558), and linker in gray (residues 444–454) to demonstrate the location of the triazole substituents with respect to the tertiary structure of the protein. The active site region is expanded showing the residues that surround the triazole and respective substituent. (B) Syn- and anti-coplanar conformations of the triazole moiety. Only the syn conformation (φ = 0°) was observed during docking studies with MbtA.

Biological Activity

Compounds 15–45 were evaluated for whole-cell activity against M. tuberculosis H37Rv under iron-limiting and iron-rich conditions. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC99) that inhibited >99% of cell growth are shown in table 1. Despite a fairly flat SAR profile in the enzyme assay, substantially greater differences in biological activity were observed for this series of 2-triazole derivatives. Methoxycarbonyl 17 and ethoxycarbonyl 18 displayed equal MIC values consistent with their equipotent enzyme activity; however hydroxymethyl 16 was 2-fold less active than these ester derivatives despite being 3-fold more potent in the enzyme assay. Linear and branched alkyl derivatives 19–28 showed a clear trend with decreasing activity as chain length increased from C3 to C12 with an optimal activity achieved with a C3 substituent and no observed activity at C12. On the other hand, cycloalkyl derivatives 29–32 containing rings from C3 to C6 did not display any apparent trend in activity, although the relative activities of these compounds only varied 8-fold overall. Significantly, the cycloalkyl compounds 29–32 were all more active than their linear chain homologues 19–22. Phenyl derivative 33 (MIC99 = 3.13 µM), was found to be equipotent to ester derivatives 17–18 consistent with their nearly identical Kiapp values. The methylphenyl-, aminophenyl-, hydroxyphenyl-, and pyridyl-series of derivatives 34–45 displayed activities ranging from 0.78–3.13 µM, representing a mere 4-fold difference in relative activities.

Table 1.

Biological and Physiochemical Properties.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | Kiapp (nM)a | MIC99 (µM)b (Fe-rich) | MIC99 (µM)c (Fe-deficient) | Permeability (x 10−6 cm/s)d | ClogPe |

| 4 | n.a. f | 6.6 ± 1.5h | 1.56i | 0.39i | −g | −0.89 |

| 5 | n.a. | 0.27 ± 0.07j | 0.049j | 0.39j | − | − |

| 15 | n.a. | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 1.56 | 0.39 | − | −2.16 |

| 16 | hydroxymethyl | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 12.5 | 6.25 | < 0.01 | −2.06 |

| 17 | methoxycarbonyl | 3.13 ± 0.25 | 25 | 3.13 | − | −1.78 |

| 18 | ethoxycarbonyl | 3.16 ± 0.16 | 12.5–25 | 3.13 | − | −1.42 |

| 19 | n-propyl | 1.58 ± 0.20 | 25 | 1.56 | − | −1.56 |

| 20 | n-butyl | 1.90 ± 0.15 | 50 | 6.25 | − | −0.20 |

| 21 | n-pentyl | 0.61 ± 0.18 | 50 | 12.5 | < 0.01 | 0.09 |

| 22 | n-hexyl | 0.29 ± 0.09 | 50 | 25 | 2.07±1.29 | 0.48 |

| 23 | n-heptyl | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 50 | > 25 | 2.65 ± 0.52 | 0.74 |

| 24 | n-octyl | 1.28 ± 0.21 | 50 | >25 | 1.61 ± 0.53 | 1.07 |

| 25 | n-decyl | 5.10 ± 0.49 | > 50 | 50 | 0.03 ± 0.17 | 1.74 |

| 26 | n-dodecyl | 2.65 ± 0.43 | >50 | >25 | 0.05 ± 0.15 | 2.44 |

| 27 | iso-butyl | 1.40 ± 0.23 | 12.5 | 6.25 | <0.01 | −0.21 |

| 28 | tert-butyl | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 12.5 | 6.25 | <0.01 | −0.23 |

| 29 | cyclopropyl | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 12.5 | 3.13 | <0.01 | −0.67 |

| 30 | cyclopentyl | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 12.5 | 1.56 | <0.01 | −0.18 |

| 31 | cyclohexyl | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 50 | 12.5 | 0.39 ± 0.33 | 0.15 |

| 32 | cyclohex-1-enyl | 1.50 ± 0.13 | >50 | 6.25 | − | 0.06 |

| 33 | phenyl | 3.23 ± 0.28 | >50 | 3.13 | − | 0.07 |

| 34 | 2-methylphenyl | 0.59 ± 0.17 | 12.5 | 3.13 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.24 |

| 35 | 3-methylphenyl | 0.95 ± 0.20 | 25 | 3.13 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.33 |

| 36 | 4-methylphenyl | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 25 | n.d. | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 0.33 |

| 37 | 2-aminophenyl | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 3.13 | 0.78 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | −0.69 |

| 38 | 3-aminophenyl | 0.63 ± 0.06 | − | − | <0.01 | −0.78 |

| 39 | 4-aminophenyl | 0.88 ± 0.18 | 6.25 | 0.78 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | −0.78 |

| 40 | pyrid-2-yl | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 3.13 | 0.78 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | −0.46 |

| 41 | pyrid-3-yl | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 3.13 | 0.78 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | −0.78 |

| 42 | pyrid-4-yl | 1.47 ± 0.12 | 3.13 | 0.78 | <0.01 | −0.78 |

| 43 | 2-hydroxyphenyl | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 25 | 1.56 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | −0.51 |

| 44 | 3-hydroxyphenyl | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 25 | 1.56 | 0.09 ± 0.21 | −0.62 |

| 45 | 4-hydroxyphenyl | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 6.25 | 1.56 | <0.01 | −0.62 |

Assay performed with 7 nMMbtA, 10 mM ATP, 250 µM salicylic acid, 1 mM PPi

Grown in normal pH 6.6 glycerol — alanine-salts (GAS) medium without ferric ammonium citrate

Grown in normal pH 6.6 glycerol — alanine-salts (GAS) medium supplemented with 200 µM ferric ammonium citrate

Permeability assayed using a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

ClogP values were calculated using the QikProp software (SchrÖdinger)

not applicable

not determined.

see ref. 13.

see ref. 10.

see ref. 18

As initially pointed-out by Quadri and co-workers, antimycobacterial activity observed under iron-rich conditions is indicative of off-target effects, since siderophore production is only required under iron-deficient conditions.9 As a benchmark, the parent compound Sal-AMS is 4-fold less active under iron deficient conditions, representing a selectivity of 4. Several of the triazole derivatives examined including n-propyl 19, phenyl 33, and 2-hydroxyphenyl 43, and 3-hydroxyphenyl 44 exhibited selectivities equal to or greater than 16.

Cytotoxicity

All compounds described herein were evaluated for inhibition of cell viability against Vero cells using the MTT assay (see Experimental Section), however, no inhibition of cell growth was observed at 100 µM, the maximum concentration evaluated. Phenyltriazole 33 was selected for more extensive evaluation against MEL, OCL-3, and REH human cancer cell lines. Cell proliferation of OCL-3 and REH lines were not affected with 100 µM 33 while the MEL line exhibited an approximately 25% inhibition of growth at 100 µM.

Physiochemical Properties

The ClogP values of 4 and 15–45 were calculated using the QikProp software (Schrödinger) while the permeability of select compounds were measured using an artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) (Table 1). The ClogP of Sal-AMS 4 is −0.89 while the ClogP values of 15–45 ranged from −2.06 for hydroxymethyl 16 to +2.44 for n-dodecyl 26. Overall, the majority of analogues possessed negative ClogP values except for phenyl 33, methylphenyl 34–36 and analogues incorporating at least 6 carbons in an aliphatic chain. To put these values in perspective, the recent report by O’Shea and Moser shows us that most antibacterial drugs are substantially more polar than drugs from other therapeutic classes.31 From their study of 147 antibacterial agents, the average ClogP values of antibacterial agents effective against Gram-negative organisms were −0.1, while the corresponding ClogP values for antibacterial agents active against Gram -positive organisms was +2.1.31

The PAMPA assay was used to measure passive transport and the measurable permeabilities varied from 0.02–2.65 × 10−6 cm/s. Notably, many compounds failed to show any permeability in artificial membranes and no consistent overall trend in permeabilities was evident. For instance, the homologues C5–C12 n-alkyl series of 21–26 showed no permeability at C5, excellent permeability at C6–C8 (1.61–2.65 × 10−6 cm/s), and greatly diminished permeability from C10–C12 (0.03–0.05 × 10−6 cm/s). Similarly, the regioisomeric methylphenyl series 34–36 the permeabilities followed the trend 4-methyl > 3-methyl > 2-methyl, but this trend was inconsistently followed for the other aryl series of compounds 37–45.

Discussion

A primary goal of this study was to explore the SAR of the C-2 position of Sal-AMS. For this we turned to the Hüisgen-Meldal-Sharpless copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), which enabled rapid preparation of a systematic series of 1,2,3-triazole analogues of Sal-AMS from a common intermediate, 2-azido-Sal-AMS 15.32 The moderate yields obtained in the key CuAAC reaction did not reflect upon the coupling efficiency, but rather losses obtained on purification of the very polar nucleoside products. Notably, the mild conditions (25 °C, MeOH) of the CuAAC reaction were compatible with the highly functionalized, polar, and fully deprotected nucleoside analogues. By contrast, our previously reported syntheses of C-2 modified analogues of Sal-AMS relied on an early stage Suzuki coupling, which necessitated harsh reaction conditions (100 °C, 16 h, toluene), a multi-step synthesis, and requirement for protecting groups.18

The 2-azidoadenine hetereocycle exists as a mixture of azide (A) and fused tetrazole (T1 and T3) valence tautomers due to cyclization at N-1 or N-3 of the purine moiety.26 Consistent with earlier studies, only the azide tautomer A and tetrazole T1 tautomer were observed as an approximately 5:1 mixture under neutral conditions in MeOH. The findings that 2-azido-5’-O-(sulfamoyl)adenosine derivative 10 underwent mild acylation at N-6 was reconciled by invoking the T1 tetrazole tautomer to promote acylation at N-10 of the tetrazole followed by a rapid intramolecular N-N acyl shift onto N-6. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of the unique reactivity of 2-azidoadenosine derivatives and we expect this facile N-6 acylation can be exploited to rapidly prepare libraries of N-6-acyl C-2 triazole derivatives of adenine as well as other heterocycles that potentially exist as tetrazole valence tautomers. Notwithstanding this interesting reactivity profile, less basic conditions were successfully employed to prevent N-6 acylation, enabling an efficient 4-step synthesis of the key intermediate 2-azido-Sal-AMS 15 from 2-azidoadenosine 7. Although not reported in this study, 15 can serve as a photoaffinity probe to identify potential off-target receptors. The finding that 15 possesses an identical iron-dependent phenotype as Sal-AMS 4 suggests 15 is an excellent candidate probe to elucidate the putative secondary mechanism(s) of action of this promising new class of antibacterial agents.

The overall SAR from these studies was remarkably flat with a mere 18-fold difference in potency across the entire series (n-hexyl 22 has a Kiapp of 0.29 nM while n-dodecyl 26 possesses a Kiapp of 5.10 nM). Despite the fairly level SAR of triazole analogues 16–45 from in vitro studies, the calculated ClogP values and experimentally determined permeabilities varied tremendously providing opportunities to modulate physiochemical and drug disposition properties of these nucleoside derivatives. For instance, although both 2-methylphenyl 34 and 3-methylphenyl 35 have equal antitubercular activity, the later compound possesses an approximately 5-fold enhancement in membrane permeability.

The whole-cell antitubercular activity showed a 64-fold variance between the most and least active compounds (aminophenyl 37 and 39 as well as pyridyl 40–42 analogues each have a MIC99 of 0.78 µM while n-decyl 25 possesses a MIC99 of 50 µM). Significantly, the long chain n-alkyl derivatives 22–26 from C6–C12 showed weak activity (MIC99 ≥ 25 µM) despite having potent enzyme inhibition. The lack of close correlation between the in vitro enzyme inhibition and whole-cell activity is likely a result of other factors such as intrinsic resistance of the organism due to limited permeability across the mycobacterial cell envelope. These results were opposite to our initial expectations since we hypothesized that the long lipid tails of 22–26 would actually promote membrane transport. Indeed Mollmann, Miller and co-workers have shown that long lipid tails enhanced mycobacterial uptake of a synthetic siderophore derivative.33 Furthermore, the mycobactin siderophores possess extremely long lipid tails of 17–20 carbons and recent evidence suggests that these lipid tails facilitate distribution of the mycobactins within macrophages.34, 35

Conclusion

A systematic series of 4-substituted triazole derivatives of 2-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-Sal-AMS was prepared and evaluated for inhibition of the aryl acid adenylating enzyme (AAAE) known as MbtA and activity against whole-cell M. tuberculosis under iron-deficient and iron-replete conditions. Remarkably, this entire series of compounds displayed potent AAAE inhibition with a majority of compounds displaying exceptional subnanomolar potency. The triazole moiety was found to exist in a coplanar syn-conformation with respect to the purine ring projecting the triazole 4-substituent into a binding pocket leading to the solvent exposed surface, formed at the interface of the N- and C-terminal domains. Docking studies recapitulated the observed SAR and provided support that binding is primarily driven by van der Waal interactions while electrostatic interactions are insignificant in the largely nonpolar C-2 binding pocket. For the majority of compounds, the trend of antitubercular activities paralleled enzyme inhibition; however, n-alkyl triazoles derivatives 20–26 deviated significantly from this behavior with activity progressively decreasing with n-alkyl chain length. Several compounds including phenyltriazole 33 displayed enhanced selectivity with a 16-fold greater activity under iron-deficient conditions relative to iron-replete conditions. The triazole derivatives of Sal-AMS described herein were found to be nontoxic providing a therapeutic index of greater than 100 for the most active analogues 37, 39–42. Based on the observed potency, selectivity, lack of cytotoxicity, and enhanced lipophilicity, phenyltriazole 33 is the best candidate of the triazole series and merits further pre-clinical evaluation. In closing, our results highlight the utility of the copper-catalyzed azide alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) to assemble a diverse series of triazole analogues to rapidly establish detailed structure activity relationships. Moreover, our finding on the ease of N-6 acylation of 2-azidopurines, via a fused tetrazole tautomer, provides insight into the unique reactivity of these heterocyclic azides.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

All commercial reagents (Sigma-Aldrich, Acros, Fluka), 3,3-dimethyl-1-butyne (Alfa Aesar) were used as provided unless otherwise indicated. 2-Ethynylphenol and 4-ethynylphenol were synthesized as reported.36 An anhydrous solvent dispensing system (J. C. Meyer) using two packed columns of neutral alumina was used for drying THF and CH2Cl2 while two packed columns of molecular sieves were used to dry DMF and the solvents were dispensed under argon. Anhydrous grade DMA, DME, MeOH, and MeCN were purchased from Aldrich. Flash chromatography was performed using Combiflash® Companion® equipped with Luknova flash column silica cartridges (www.luknova.com) with the indicated solvent system. All reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of dry Ar or N2 in oven-dried (150 °C) glassware. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer. Proton chemical shifts are reported in ppm from an internal standard of residual methanol (3.31 ppm), and carbon chemical shifts are reported using an internal standard of residual methanol (49.1 ppm). Proton chemical data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, m = multiplet, hep = heptet), coupling constant, integration. High resolution mass spectra were obtained on Agilent TOF II TOF/MS instrument equipped with either an ESI or APCI interface. Analytical HPLC were obtained on an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system with a PDA detector.

2-Azido-2′,3′-O-isopropylideneadenosine (9). Procedure A

A solution of 721 (2.4 g, 5.32 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 7 N NH3 in MeOH (120 mL, 840 mmol NH3, 158 equiv) was stirred at 50 °C for 15 h. The reaction was concentated in vacuo, then placed under hi-vacuum for several hours to remove traces of ammonia. The resulting residue was suspended in acetone (150 mL) and p-TSA (1.6 g, 8.47 mmol, 1.6 equiv) and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (4.8 mL, 39.0 mmol, 7.3 equiv) were added and the reaction stirred 16 h at rt. The reaction was quenched by adding solid NaHCO3 (5.0 g) and the resulting heterogeneous slurry was stirred for 30 min, then filtered and concentrated. Purification by flash chromatography (95:5 EtOAc/hexane) afforded the title compound (1.57 g, 48%) as a light yellow solid: Rf 0.55 (EtOAc); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 3.70 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 11.4, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.20–4.35 (m, 1H), 5.20 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.08 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 25.5, 27.8, 63.4, 81.7, 83.2, 86.6, 93.6, 114.4, 118.4, 140.1, 150.2, 156.5, 156.9; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C13H15N8O4 [M - H]+347.1211, found 347.1230 (error 5.5 ppm).

Procedure B

Sodium ascorbate (18.3 mg, 0.09 mmol, 0.2 equiv) and CuSO4·5H2O (23.0 mg, 0.09 mmol, 0.2 equiv) were added to a mixture of 2-iodo-2’,3’-O-isopropylideneadenosine23 (200 mg, 0.46 mmol, 1.0 equiv), sodium azide (36.0 mg, 0.55 mmol, 1.2 equiv), l-proline (10.6 mg, 0.09 mmol, 0.2 equiv), and sodium carbonate (9.7 mg, 0.09 mmol, 0.2 equiv) in H2O/tert-BuOH (1:1, 10 mL). The mixture was stirred 16 h at 65 °C. After cooling to rt, the reaction was partioned between 0.02 M NH4OH (50 mL) and EtOAc (50 mL). The aqueous layer was further extracted with EtOAc (2 × 50 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (50 mL), dried (MgSO4), and concentrated. Purification by flash chromatography (95:5 EtOAc/MeOH) afforded the title compound (85 mg, 52%) as a light yellow solid.

2-Azido-2′,3′-O-isopropylidene-5′-O-(sulfamoyl)adenosine (10)

To a solution of compound 9 (1.57 g, 4.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DME (150 mL) was added NaH (540 mg, 13.5 mmol, 3.0 equiv) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at rt. Next, sulfamoyl chloride37(780 mg, 6.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) dissolved in DME (20 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight at rt. The reaction mixture was filtered and concentrated. Purification by flash chromatography (5:95 Hexanes/EtOAc) afforded the title compound (1.28 g, 67%) as a white solid: Rf 0.6 (95:5 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 4.25 (dd, J = 10.2, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (dd, J = 10.2, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 4.45–4.55 (m, 1H), 5.12 (dd, J = 6.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 5.43 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 25.5, 27.5, 70.0, 83.0, 85.6, 85.9, 91.7, 115.6, 118.0, 141.2, 151.6, 158.2, 158.5; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C13H18N9O6S [M + H]+ 428.1095, found 428.1098 (error 0.7 ppm).

2-Azido-2′,3′-O-isopropylidene-5′-O-{N-[2-(methoxymethoxy)benzoyl]sulfamoyl}-N6-[2-(methoxymethoxy)benzoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (12)

To a solution of N-hydroxysuccinimdyl ester of MOM protected salicylic acid 1113 (1.3 g, 4.7 mmol, 2.0 equiv) in DMF (50 mL) at 0 °C was added 10 (1.0 g, 2.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and Cs2CO3 (1.9 g, 6.9 mmol, 3.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was warmed to rt and stirred for an additional 16 h. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue taken up in EtOAc and filtered. The solids were washed with additional EtOAc (100 mL) and the combined filtrate was concentrated. Purification by flash chromatography(10:90:0.5 EtOAc/MeOH/Et3N)afforded the title compound. (721 mg, 53%) as a thick oil:Rf 0.6 (19:1 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.61 (s, 3H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 3.53 (s, 3H), 4.31 (dd, J = 10.8, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (dd, J = 11.4, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.59–4.69 (m, 1H), 5.13 (s, 2H), 5.22 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.43 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (s, 2H), 6.27 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.70 (s, 1H) 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 25.6, 27.6, 49.9, 56.7, 57.7. 70.2, 83.4, 85.9, 86.2, 90.0, 96.6, 96.8, 115.3, 116.4, 117.2, 121.3, 122.6, 123.8, 130.1, 131.4, 132.1, 132.6, 133.2, 135.7, 144.5, 151.2, 154.8, 155.8, 157.1, 157.9, 165.1, 176.6; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C31H32N9O12S [M - H]− 754.1897, found 754.1893 (error 0.5 ppm).

2-Azido-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2′,3′-O-isopropylideneadenosine Triethylammonium Salt (14)

A solution of salicylic acid (389 mg, 2.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and CDI (456 mg, 2.8 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in MeCN (35 mL) was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h. The solution was cooled to rt and a mixture of 10 (1.0 g, 2.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and DBU (0.5 mL, 3.5 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was then added and the reaction stirred 16 h at rt. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and purified by flash chromatography (70:30:0.5 EtOAc/MeOH/Et3N) to afford the title compound (1.4 g, 93%) as a white solid: Rf 0.3 (9.5:0.5 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H), 3.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.28–4.31 (m, 1H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.51–4.53 (m, 1H), 5.08–5.10 (m, 1H), 5.35–5.36 (m, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 25.5, 27.5, 47.9, 70.2, 83.2, 85.6, 85.9, 91.6, 115.4, 117.7, 118.0, 119.4, 120.5, 131.3, 134.5, 141.1, 151.6, 158.0, 158.2, 162.0, 174.9; MS (APCI–) calcd for C20H20N9O8S [M - H]− 546.1, found 546.2.

2-Azido-2′,3′-O-isopropylidene-5′-O-{N-[2-(methoxymethoxy)benzoyl]sulfamoyl}adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (13)

To a 50 mL glass cylindrical pressure vessel at 0 °C was added a methanolic ammonia solution (20 mL, 7.0 M) and compound 12 (40 mg, 0.05 mmol). The reaction vessel was sealed with a Teflon bushing and heated at 60 °C for 8 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and carried forward to the next step without further purification.

2-Azido-5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (15)

To a solution of 14 (1.3 g, 2.0 mmol) or 13 (crude oil from above) was added 80% aq TFA (20 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting solution was stirred for 3 h at rt then concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification by flash chromatography (70:30:0.5 EtOAc/MeOH/Et3N) afforded the title compound (771.8 mg, 62% from 14) or (16.2 mg, 54% over 2 steps from 12 via 13) as a white solid: Rf 0.5 (85:15 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.20 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.27–4.32 (m, 1H), 4.36–4.44 (m, 3H), 4.66 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.00 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.75–6.82 (m, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.8, 72.5, 76.1, 84.7, 89.2, 117.7, 117.9, 119.4, 120.7, 131.5, 134.4, 140.7, 152.5, 158.1, 158.3, 162.2, 175.5; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C17H16N9O8S [M - H]− 506.0848, found 506.0847 (error 0.1 ppm).

General procedure for Triazole synthesis

To a solution of azide 15 (0.033 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in MeOH (2 mL) at rt was added Cu(OAc)2 (0.0033 mmol, 0.1 equiv dissolved in 100 µL H2O), sodium ascorbate (0.0033 mmol, 0.1 equiv dissolved in 100 µL H2O) and the appropriate alkyne (0.099 mmol, 3.0 equiv). The resulting mixture was stirred 16 h at rt. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure onto silica gel. Purification was carried out using a Combiflash® Companion® flash chromatography system fitted with 4 g Luknova silica cartridges and a solvent system containing 70:30:0.5 EtOAc/MeOH/Et3N, pumped at a flow rate of 18 mL/min. The separation of the title compounds was detected at a UV wavelength of 254 nm.

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-hydroxymethyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (16)

Propargyl alcohol was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.9 mg, 73%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.4 (8:2 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.73 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.76 (s, 2H), 6.13 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.72 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 56.6, 69.5, 72.2, 76.1, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.4, 119.9, 120.7, 123.1, 131.4, 134.4, 142.1, 149.5, 150.8, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C20H20N9O9S [M - H]–562.1110, found 562.1138 (error 5.0 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-methoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Sodium Salt (17)

Methyl propiolate was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis and converted to the sodium salt by ion exchange using Dowex 50WX2-Na+ to afford the title compound (13.8 mg, 61%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 3.97 (s, 3H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.40–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.46 (m, 2H), 4.70 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H), 9.28 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 52.8, 69.6, 72.2, 76.5, 84.7, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 120.1, 120.7, 128.4, 131.4, 134.4, 140.7, 142.2, 150.4, 151.4, 158.2, 162.1, 162.4, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C21H20N9O10S [M - H]− 590.1059, found 590.1053 (error 1.0 ppm).

2-(4-Ethoxycarbonyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Sodium Salt (18)

Ethyl propiolate was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis and converted to the sodium salt by ion exchange using Dowex 50WX2-Na+ to afford the title compound (12.8 mg, 55%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.42 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.40–4.46 (m, 5H), 4.70 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.59 (s, 1H), 9.24 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 18.5, 58.4, 69.6, 72.2, 76.5, 84.7, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 120.1, 120.7, 128.4, 131.5, 134.4, 140.7, 142.2, 150.4, 151.4, 158.2, 162.1, 162.4, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C22H22N9O10S [M - H]− 604.1216, found 604.1250 (error 5.6 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-n-propyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (19)

1-Pentyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (11.2 mg, 50%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.00 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.76 (h, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 14.1, 23.8, 28.4, 48.0, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.1, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.6, 150.9, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C22H24N9O8S [M - H]− 574.1474, found 574.1464 (error 1.7 ppm).

2-(4-n-Butyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Sodium Salt (20)

1-Hexyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis and converted to the sodium salt by ion exchange using Dowex 50WX2-Na+ to afford the title compound (9.5 mg, 47%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.97 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.43 (h, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.79 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.76 (s, 2H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.58 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 14.1, 23.8, 24.2, 28.4, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 118.0, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.2, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.7, 150.9, 151.6, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C23H26N9O8S [M - H]− 588.1631, found 588.1634 (error 0.5 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-n-pentyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (21)

1-Heptyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (16.4 mg, 71%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.91 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.35–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.73 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 14.4, 23.5, 26.3, 30.3, 32.6, 48.1, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.1, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.8, 150.9, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C24H28N9O8S [M - H]− 602.1787, found 602.1781 (error 1.0 ppm).

2-(4-n-Hexyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (22)

1-Octyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (17.8 mg, 75%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.32–1.34 (m, 4H), 1.38–1.42 (m, 2H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 14.4, 23.6, 26.3, 30.0, 30.4, 32.7, 48.0, 69.4, 72.1, 76.0, 84.5, 89.8, 117.8, 119.2, 119.8, 120.6, 122.0, 131.4, 134.3, 141.9, 149.7, 150.7, 151.4, 158.0, 162.0, 175.0; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H30N9O8S [M - H]−616.1944, found 616.1943 (error 0.1 ppm).

2-(4-n-Heptyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (23)

1-Nonyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (22.3 mg, 92%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.28–1.32 (m, 4H), 1.32–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.2 Hz , 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 14.4, 23.7, 26.3, 30.1, 30.2, 30.5, 32.9, 48.0, 69.4, 72.1, 76.0, 84.5, 89.8, 117.8, 119.2, 119.7, 120.6, 122.0, 131.4, 134.3, 141.9, 149.7, 150.8, 151.4, 158.0, 162.0, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C26H32N9O8S [M - H]− 630.2100, found 630.2114 (error 2.2 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-n-octyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (24)

1-Decyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (16.1 mg, 65%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.31–1.39 (m, 10H), 1.73 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 14.4, 23.7, 26.3, 30.3, 30.3, 30.4, 30.5, 33.0, 48.0, 69.4, 72.1, 76.0, 84.5, 89.8, 117.8, 119.2, 119.7, 120.6, 122.0, 131.4, 134.3, 141.9, 149.7, 150.7, 151.4, 158.0, 162.0, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C27H34N9O8S [M - H]−644.2257, found 644.2250 (error 1.1 ppm)

2-(4-n-Decyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (25)

1-Dodecyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.4 mg, 60%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.31–1.41 (m, 14H), 1.72 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.73 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 14.5, 23.8, 26.4, 30.4, 30.54, 30.55, 30.56, 30.78, 30.81, 33.2, 48.1, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.1, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.8, 150.9, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C29H38N9O8S [M - H]− 672.2570, found 672.2558 (error 1.8 ppm).

2-(4-n-Dodecyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (26)

1-Tetradecyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (13.5 mg, 51%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.88 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.28–1.42 (m, 18H), 1.72 (p, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.33–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14(d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 14.5, 23.8, 26.4, 30.4, 30.54, 30.56 (2C), 30.76, 30.83, 30.86, 30.87, 33.2, 48.1, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.1, 131.5, 134.4, 142.1, 149.8, 150.9, 151.5, 158.1, 162.2, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C31H42N9O8S [M - H]− 700.2883, found 700.2862 (error 3.0 ppm).

2-(4-iso-Butyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (27)

4-Methyl-1-pentyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (14.6 mg, 64%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.96 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 2.00–2.04 (m, 1H), 2.65 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.32–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.47 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 22.7 (2C), 29.8, 35.4, 48.0, 69.5, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.8, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 122.7, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 148.6, 150.9, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C23H26N9O8S [M - H]− 588.1631, found 588.1634 (error 0.5 ppm).

2-(4-tert-Butyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (28)

3,3-Dimethyl-1-butyne was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.2 mg, 67%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.40–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.46 (m, 2H), 4.68 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.75–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 30.5, 31.8, 48.0, 69.5, 72.2, 76.4, 84.6, 89.5, 117.8, 119.2, 119.6, 119.8, 120.6, 131.4, 134.3, 141.7, 150.9, 151.6, 158.0, 158.8, 162.0, 175.0; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C23H26N9O8S [M - H]− 588.1631, found 588.1625 (error 1.0 ppm).

2-(4-Cyclopropyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (29)

Cyclopropylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.8 mg, 71%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 0.87–0.90 (m, 2H), 1.00–1.03 (m, 2H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 2.02–2.08 (m, 1H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.3, 8.27, 8.31, 9.2, 47.9, 69.4, 72.1, 76.1, 84.5, 89.7, 117.8, 119.2, 119.7, 120.6, 120.7, 131.4, 134.3, 141.9, 150.7, 151.4, 151.8, 158.0, 162.0, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C22H22N9O8S [M - H]− 572.1318, found 572.1335 (error 3.0 ppm).

2-(4-Cyclopentyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (30)

Cyclopentylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.6 mg, 67%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.70–1.76 (m, 4H), 1.80–1.82 (m, 2H), 2.12–2.17 (m, 2H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz,6H), 3.23 (p, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.33–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.47 (m, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 26.2, 34.20, 34.23, 37.9, 48.1, 69.6, 72.2, 76.3, 84.6, 89.8, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.7, 121.0, 131.5, 134.4, 141.9, 150.9, 151.6, 153.9, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C24H26N9O8S [M - H]− 600.1631, found 600.1646 (error 2.5 ppm).

2-(4-Cyclohexyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (31)

Cyclohexylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.1 mg, 64%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 1.30–1.34 (m, 1H), 1.45 (q, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 1.52 (q, J = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 1.74–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.83–1.85 (m, 2H), 2.07–2.09 (m, 2H), 2.77–2.84 (m, 1H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 27.1, 27.2 (2C), 33.91, 33.95, 36.5, 48.0, 69.5, 72.1, 76.2, 84.5, 89.7, 117.8, 119.2, 119.7, 120.6, 120.7, 131.4, 134.3, 141.8, 150.8, 151.5, 154.8, 158.0, 162.0, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H28N9O8S [M - H]− 614.1787, found 614.1799 (error 2.0 ppm).

2-(4-Cyclohex-1-enyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Sodium Salt (32)

1-Ethynylcyclohexene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis and converted to the sodium salt by ion exchange using Dowex 50WX2-Na+ to afford the title compound (15.4 mg, 66%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.70–1.73 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.83 (m, 2H), 2.23–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.44–2.47 (m, 2H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.42 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (br s, 1H), 7.27 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 23.3, 23.6, 26.3, 27.3, 69.5, 72.2, 76.3, 84.6, 89.7, 117.8, 119.20, 119.22, 119.7, 120.6, 127.1, 128.1, 131.4, 134.3, 141.8, 150.5, 150.8, 151.5, 158.0, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H26N9O8S [M - H]− 612.1631, found 612.1630 (error 0.1 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-(4-phenyl-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)adenosine Sodium Salt (33)

Phenylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis and converted to the sodium salt by ion exchange using Dowex 50WX2-Na+ to afford the title compound (9.1 mg, 46%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 4.36–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.75 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 69.5, 72.1, 76.2, 84.6, 89.8, 117.8, 119.2, 119.8, 120.6, 120.7, 127.0, 129.6, 130.0, 131.3, 131.4, 134.3, 142.0, 149.0, 150.7, 151.5, 158.1, 162.0, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H22N9O8S [M - H]− 608.1318, found 608.1310 (error 1.3 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(2-methylphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (34)

2-Ethynyltoluene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (12.3 mg, 51%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.51–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.71 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.2, 21.4, 47.9, 69.5, 72.1, 76.4, 84.5, 89.7, 117.8, 119.2, 119.8, 120.6, 122.7, 127.2, 129.7, 130.1, 130.5, 131.4, 131.9, 134.3, 137.2, 141.8, 148.3, 150.8, 151.5, 158.0, 162.0, 175.0; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C26H24N9O8S [M - H]− 622.1474, found 622.1471 (error 0.5 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(3-methylphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (35)

3-Ethynyltoluene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (10.5 mg, 44%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (8:2 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.40–4.43 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.75 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 21.6, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.3, 84.6, 89.8, 117.4, 117.9, 119.4 , 119.9, 120.7, 124.2, 127.6, 130.0, 130.4, 131.2, 131.5, 134.4, 140.0, 142.1, 149.2, 150.8, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C26H24N9O8S [M - H]− 622.1474, found 622.1469 (error 0.8 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(4-methylphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (36)

4-Ethynyltoluene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (10.5 mg, 44%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.43 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 21.4, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.3, 84.6, 89.8, 117.9, 119.3, 119.8, 120.3, 120.7, 127.0, 128.5, 130.7, 131.5, 134.4, 139.8, 142.0, 149.1, 150.8, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C26H24N9O8S [M - H]− 622.1474, found 622.1464 (error 1.6 ppm).

2-[4-(2-Aminophenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (37)

2-Ethynylaniline was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (10.6 mg, 45%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.42–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.44–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.78 (m, 3H), 6.85 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 9.01 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.5, 84.6, 89.8, 115.2, 117.9, 118.2, 118.9, 119.4, 119.8, 120.7, 120.9, 129.4, 130.5, 131.5, 134.4, 141.9, 146.8, 149.3, 150.9, 151.6, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H23N10O8S [M - H]− 623.1427, found 623.1405 (error 3.5 ppm).

2-[4-(3-Aminophenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]-5′-O-[N-(2-ydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (38)

3-Ethynylaniline was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (15.2 mg, 63%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.24 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.70–6.77 (m, 3H), 7.15 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.93 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.2, 84.6, 89.9, 113.8, 116.8, 116.9, 117.9, 119.4, 119.9, 120.5, 120.7, 130.8, 131.5, 131.9, 134.4, 142.0, 149.4, 149.5, 150.8, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H23N10O8S [M - H]− 623.1427, found 623.1437 (error 1.6 ppm).

2-[4-(4-Aminophenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]-5′-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (39)

4-Ethynylaniline was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (12.5 mg, 52%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 4H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.4, 84.6, 89.8, 116.5, 118.0, 119.0, 119.4, 119.8, 120.6, 120.7, 128.1, 131.5, 134.4, 141.9, 149.8, 149.9, 150.9, 151.6, 158.1, 162.1, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H23N10O8S [M - H]− 623.1427, found 623.1417 (error 1.6 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(pyrid-2-yl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (40)

2-Ethynylpyridine was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (11.6 mg, 50%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.3 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.17 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.76 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (m, 1H), 7.90–7.92 (m, 2H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.59 (br s, 1H), 9.19 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.5, 84.6, 89.9, 117.9, 119.3, 119.9, 120.7, 122.1, 122.7, 124.7, 130.0, 131.5, 132.5, 134.4, 139.0, 142.0, 148.7, 150.7, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C24H21N10O8S [M - H]− 609.1270, found 609.1261 (error 1.5 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(pyrid-3-yl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (41)

3-Ethynylpyridine was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (14.2 mg, 61%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.3 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.19 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.50–4.52 (m, 2H), 6.16 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 6.72–6.76 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51–8.53 (m, 2H), 9.15 (s, 1H), 9.27 (s, 1H), H-2’ obscured by HOD; 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.3, 75.9, 84.7, 90.0, 117.9, 119.3, 120.1, 120.7, 121.9, 125.7, 128.4, 131.4, 134.4, 135.5, 142.4, 145.7, 147.6, 149.8, 150.7, 151.5, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C24H21N10O8S [M - H]− 609.1270, found 609.1257 (error 2.1 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(pyrid-4-yl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (42)

4-Ethynylpyridine was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (12.4 mg, 64%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.3 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.33–4.35 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.51–4.52 (m, 2H), 4.87 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.71–6.75 (m, 2H), 7.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 9.31 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.3, 75.8, 84.7, 90.1, 117.9, 119.3, 120.2, 120.7, 121.9, 123.1, 131.4, 134.4, 140.1, 142.6, 148.1, 150.6, 150.8, 151.4, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C24H21N10O8S [M - H]− 609.1270, found 609.1308 (error 6.2 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (43)

2-Hydroxyphenylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (12.2 mg, 51%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.36–4.38 (m, 1H), 4.42–4.44 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.70 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.75–6.78 (m, 2H), 6.93–6.96 (m, 2H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.7, 72.3, 76.5, 84.7, 89.7, 117.2, 117.4, 118.0, 119.4, 119.8, 120.7, 120.8, 122.6, 128.2, 130.6, 131.5, 134.4, 141.8, 145.9, 151.0, 151.6, 156.1, 158.1, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H22N9O9S [M - H]− 624.1267, found 624.1305 (error 6.1 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (44)

3-Hydroxyphenylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (12.2 mg, 51%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.15 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.34–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.43 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.47 (m, 2H), 4.72 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 2H), 6.78–6.80 (m, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.38–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.91 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.4, 84.6, 89.8, 113.7, 116.8, 117.2, 118.0, 118.4, 119.4, 119.8, 120.7, 131.2, 131.5, 132.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.1, 150.8, 151.6, 158.1, 159.2, 162.1, 175.1; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H22N9O9S [M - H]− 624.1267, found 624.1288 (error 3.4 ppm).

5′-O-[N-(2-Hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-[4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]adenosine Triethylammonium Salt (45)

4-Hydroxyphenylacetylene was reacted with 15 using the general procedure for triazole synthesis to afford the title compound (10.4 mg, 44%) as a white amorphous solid: Rf 0.6 (80:20 EtOAc/MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 1.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 9H), 3.19 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 4.35–4.36 (m, 1H), 4.41–4.43 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 2H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.75–6.78 (m, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.8, 1H), 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.98 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) 9.3, 48.0, 69.6, 72.2, 76.4, 84.7, 89.7, 116.8, 117.9, 119.3, 119.6, 119.8, 120.7, 122.7, 128.5, 131.5, 134.4, 142.0, 149.3, 150.9, 151.6, 158.1, 159.4, 162.2, 175.2; HRMS (ESI–) calcd for C25H22N9O9S [M - H]− 624.1267, found 624.1197 (error 11.2 ppm).

Docking Studies

The MbtA structure obtained following QM/MM studies of the complex formed between MbtA (homology model) and 5’-O-[N-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2- phenyladenosine was used for docking studies with Glide.18,38 Docking was performed on a cubic box of 10 Å side, centered on the active site, using the default XP (extra precision) settings. The core pattern comparison option was used to match the heavy atoms of the SalAMS core of the ligands with those of the SalAMS core of minimized 5’-O-[N-(2- hydroxybenzoyl)sulfamoyl]-2-phenyladenosine in complex with MbtA, allowing a 2 Å tolerance in RMSd.18

Fukui Analysis

A geometry optimization was completed on the neutral truncated tetrazole T1 (Scheme 2B) whereby the C5’ hydroxymethyl group was replaced with a hydrogen atom at the B3LYP/6–31G* level of theory using the GAMESS electronic structure package.39 Using this geometry a single point energy calculation was completed on the cation (vertical ionization), and the electron distribution and surface of each plotted with Molden.40 Subtracting the cation density from that of the neutral species yields the Fukui function (a volumetric function indicating the most nucleophilic regions of the molecule).41 Similiarly, the atomic charges derived though Mulliken population analysis are differenced for each atom to yield the local Fukui function.

Enzyme kinetic studies. ATP/PPi Exchange Assay

MbtA was expressed in E. coli and purified as described.13 The inhibition assays were performed as described in duplicate.13 In brief the reaction was initiated by adding 10 µL [32]PPi with 7 nM MbtA in 90 µL reaction buffer (250 µM salicylic acid, 10 mM ATP, 1 mM PPi, 75 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT) at 37°C in the presence of five different concentrations of the inhibitor. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 200 µL of quenching buffer (350 mM HClO4, 100 mM PPi, 1.8 %w/v activated charcoal). The charcoal was pelleted by centrifugation and washed once with 500 µL H2O and analyzed by liquid scintillation counting. The KIapp values were calculated using the Morrison equation (eq 1).

| (1) |

PAMPA Assay

PAMPA assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions in triplicate (BD Gentest #353015). Compound stock solutions (10 mM in DMSO) were diluted to 100 µM in PBS (Dulbecco’s) to a final volume of 1.5 mL. The diluted stocks were added to the bottom donor plate (300 µL) and 200 µL of PBS was added to the top acceptor plate and the plates were incubated for 5 h at rt. The equilibrium plate was made by aliquoting 3 × 100 µL into a 96 well UV clear half-area plate (Greiner) and integrating the absorbances at 280, 300, 320, 340 and 360 nm with the background subtracted using PBS as a buffer blank on an M5e plate reader (Molecular Devices). Wells were also read at 800 nm to check for light scattering. After the incubation the acceptor plate was removed from the donor plate and 100 µL was transfered from each well of the two plates to two 96-well UV clear half-area 96 well plates. The plates were read as described above and the data was processed using the Xcel analysis file available from BD Biosciences. Caffeine and ketoprofin were included on the plate as positive controls while hydrochlorothiazide was used as a negative control.

Vero Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

African green monkey Cercopithecus aethiops kidney cells (Vero, ATCC) cells were plated in 96-well plates at 2.5–5.0 × 104 cells per well (200 µL). Vero cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Compounds were prepared as 20 mM stock solutions in DMSO and 1 µL of the compound stock solution was added to each well in 200 µL MEM, yielding a final compound concentration of 100 µM. Control wells contained either 1% DMSO (negative control) or 100 µM 5‘-O-(sulfamoyl)adenosine (positive control) and all reactions were done in triplicate. The plate was incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/95% air humidified atmosphere. Measurement of cell viability was carried out using a modified method of Mosmann based on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT).42 MTT was prepared fresh at 1 mg/mL in serum-free, phenol red-free RPMI 1640 media. MTT solution (200 µL) was added to each well and the plate was incubated as described above for 3 h. The MTT solution was removed and the formazan crystals were solubilized with 200 µL isopropanol. The plate was read on a M5e spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) at 570 nm for formazan and 650 nm for background subtraction. Cell viability was estimated as the percentage absorbance of sample relative to the DMSO control.

MEL, OCL, and REH Cytotoxicity Assay

The three human cancer cells (SK-MEL-2 cells: human melanoma; OCL-3 cells: OCI-AML3, human acute myeloid leukemia; REH cells: human B cells precursor leukemia) were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The in vitro cytotoxicity of the small molecules was assayed by determining the GI50’s (the concentration of the small molecules to reduce the cell growth by 50%). In brief, the cells were plated in a 96-well plate (104 cells/well for OCI-AML3 and HEL and 2,500 cells/well for SK-MEL-2). The cells were treated with the small molecules with a series of 3-fold dilution with 1% DMSO in the final cell media (cells treated with media of 1% DMSO served as a control). After a 48-h treatment, the relative cell viability in each well was determined by using CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega, CA).

M. tuberculosis H37Rv MIC Assay

All compounds MICs were experimentally determined as previously described.10 Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined in quadruplicate in iron-deficient GAST and GAST supplemented with 200 µM FeCl3 according to the broth microdilution method using compounds from DMSO stock solutions or with control wells treated with an equivalent amount of DMSO. Isoniazid was used as positive controls while DMSO was employed as a negative control. All measurements reported herein used an initial cell density of 104–105 cells/assay and growth monitored at 10–14 days, with the untreated and DMSO-treated control cultures reaching an OD620 ∼0.2–0.3. Plates were incubated at 37 °C (100 µL/well) and growth was recorded by measurement of optical density at 620 nm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01AI070219) and funding from the Center for Drug Design, Academic Health Center, University of Minnesota to C.C.A. This research supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. We thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for computing time.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAAE

aryl acid adenylating enzyme

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CuAAC

copper-catalyzed azide alkyne cycloaddition

- DOTS

directly observed therapy short-course

- DMA

dimethylacetamide

- DME

dimethoxyethane

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- HIV/AIDS

human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- Kiapp

apparent inhibition constant

- MDR-TB

multidrug resistant tuberculosis

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MIC99

minimum inhibitor concentration at which 99% of organisms are inhibited in growth

- MOM

methoxymethyl

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- p-TSA

para-toluenesulfonic acid

- SAR

structure activity relationships

- Sal-AMS

5’-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl] adenosine

- TB

tuberculosis

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- XDR-TB

extensively drug resistant tuberculosis

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Table of HPLC purities of 15–45. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Duncan K, Barry CE., 3rd Prospects for new antitubercular drugs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; Global tuberculosis control surveillance, planning, and financing: WHO report 2008. 2008

- 3.Guiterrez-Lugo M-T, Bewley CA. Natural products, small molecules, and genetics in tuberculosis drug development. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2606–2612. doi: 10.1021/jm070719i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond KN, Dertz EA, Kim SS. Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratledge C, Dover LG. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000;54:881–941. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quadri LE. Assembly of aryl-capped siderophores by modular peptide synthetases and polyketide synthases. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosa JH, Walsh CT. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:223–249. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.223-249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LE. Small-molecule inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Yersinia pestis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:29–32. doi: 10.1038/nchembio706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somu RV, Boshoff H, Qiao C, Bennett EM, Barry CE, 3rd, Aldrich CC. Rationally designed nucleoside antibiotics that inhibit siderophore biosynthesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:31–34. doi: 10.1021/jm051060o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miethke M, Bisseret P, Beckering CL, Vignard D, Eustache J, Marahiel MA. Inhibition of aryl acid adenylation domains involved in bacterial siderophore synthesis. FEBS J. 2006;273:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan BP, Lomino JV, Wolfenden R. Nanomolar inhibition of the enterobactin biosynthesis enzyme, EntE: synthesis, substituent effects, and additivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3802–3805. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somu RV, Wilson DJ, Bennett EM, Boshoff HI, Celia L, Beck BJ, Barry CE, 3rd, Aldrich CC. Antitubercular nucleosides that inhibit siderophore biosynthesis: SAR of the glycosyl domain. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7623–7635. doi: 10.1021/jm061068d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiao CH, Gupte A, Boshoff HI, Wilson DJ, Bennett EM, Somu RV, Barry CE, 3rd, Aldrich CC. 5'-O-[(N-Acyl)sulfamoyl]adenosines as antitubercular agents that inhibit MbtA: An adenylation enzyme required for siderophore biosynthesis of the mycobactins. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6080–6094. doi: 10.1021/jm070905o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]