Abstract

The Eph family tyrosine kinase receptors and their ligands, ephrins, play key roles in a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes including tissue patterning, angiogenesis, bone development, carcinogenesis, axon guidance, and neural plasticity. However, the signaling mechanisms underlying these diverse functions of Eph receptors have not been well understood. In this study, effects of Eph receptor activation on several important signal transduction pathways are examined. In addition, the roles of these pathways in ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse were assessed with a combination of biochemical analyses, pharmacological inhibition, and overexpression of dominant-negative and constitutively active mutants. These analyses showed that ephrin-A5 inhibits Erk activity while activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase. However, regulation of these two pathways is not required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse in hippocampal neurons. Artificial Erk activation by expression of constitutively active Mek1 and B-Raf failed to block ephrin-A5 effects on growth cones, and inhibitors of the Erk pathway also failed to inhibit collapse by ephrin-A5. Inhibition of JNK had no effects on ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse either. In addition, inhibitors to PKA and PI3-K showed no effects on ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. However, pharmacological blockade of phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity, the Src family kinases, cGMP-dependent protein kinase, and myosin light chain kinase significantly inhibited ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. These observations indicate that only a subset of signal transduction pathways is required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

Keywords: Growth cone collapse, Eph family, Ephrins, Erk, myosin light chain kinase, phosphotyrosine phosphatase, cGMP-dependent protein kinase

Introduction

The Eph family of receptors and ligands are widely expressed during development and in adult tissues, although individual members are only expressed in specific tissues or organ (Zhou, 1998). Consistent with the widespread expression, these molecules have been shown to regulate many important biological processes (Andres and Ziemiecki, 2003; Klein, 2004; Poliakov et al., 2004; Surawska et al., 2004; Wimmer-Kleikamp and Lackmann, 2005; Heroult et al., 2006; Ivanov and Romanovsky, 2006; Zhang and Hughes, 2006; Pasquale, 2008). For example, EphA4 and ephrin-B2 participate in the segmentation of the hindbrain (Wilkinson, 2000), and both Eph-A and Eph-B receptors and ligands are shown to regulate vascularization and angiogenesis (Wang et al., 1998; Adams et al., 1999; Zhang and Hughes, 2006). Another important function is to guide axons to their proper targets during nervous system development. Both EphA and EphB receptors and their ligands have been shown to regulate spatially organized axon projection maps in the brain (Flanagan and Vanderhaeghen, 1998; Zhou, 1998; McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005). Recent studies have revealed additional functions in regulating neural plasticity (Klein, 2004; Pasquale, 2008), tumorigenesis (Wimmer-Kleikamp and Lackmann, 2005; Heroult et al., 2006), bone morphogenesis (Compagni et al., 2003; Davy et al., 2004), and inflammative responses (Ivanov and Romanovsky, 2006). Mutations in ephrin-B1 have been associated with craniofrontonasal syndrome in humans (Wieacker and Wieland, 2005; Shotelersuk et al., 2006; Twigg et al., 2006; Vasudevan et al., 2006). With expression in many tissues and organs, it would not be surprising that novel functions of these receptors are continuously discovered in the future.

In spite of the clear importance of these molecules in physiological and pathological processes, the signaling mechanisms underlying their functions are not well understood. It has been shown that Eph receptors regulate Rho family small GTPases through interaction with Ephexin (Wahl et al., 2000; Shamah et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2003; Ogita et al., 2003; Miao et al., 2005; Sahin et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2007) and Vav (Cowan et al., 2005) family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. In addition, many other signal transduction mediators including the Src family kinase, Nck, PI3-K, and LMW-PTP have been shown to physically associate with Eph receptors (Kullander and Klein, 2002). However, it is still largely unknown which molecules are required for what functional outputs. It is also not clear whether different functions utilize the same signaling pathways. In addition, since the receptors are highly homologous, it is not known whether different Eph receptors activate similar downstream pathways. In this study, we have extensively surveyed roles of different signaling pathways in ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse. Our analyses show that only a select few are involved in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Ephrin-A5-Fc was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); AffiniPure rabbit anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). The following pharmacological reagents were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA): mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors, U0126 and PD98059; c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor, SP600125; Src inhibitor PP2, and control PP3; phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) inhibitors, Wortmannin and LY294002; broad-spectrum protein kinases inhibitor Staurosporine; protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors, Go 6983, Bisindolylmaleimide I, Ro31-8220, and the control Bisindolylmaleimide V; protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor KT5720, activator Sp-cAMPS; myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) inhibitor Peptide 18; Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor KN-93; cGMP-dependent protein (PKG) inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS; The following reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO): protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) inhibitors, Phenylarsine Oxide (PAO) and Sodium Orthovanadate. The inhibitor concentrations used were based on IC50, previously published studies as well as potential inhibitory effects on growth cone morphology.

Construction of adenoviruses and expression vectors

cDNA sequences (Jaaro et al., 1997) encoding the constitutively active MEK1 (CA-MEK1) and dominant negative MEK1 (DN-MEK1) mutant proteins (Jaaro et al., 1997) were inserted into the EGFP expressing shuttle plasmid pAdTrack-CMV of the adenoviral vector system AdEasy (QBiogene, Irvine, CA). Recombinant adenoviral constructs were generated by homologous recombination between the shuttle vectors and the viral backbone plasmid pAdEasy-1 in BJ5183 E. coli cells. Recombinant CA-MEK1 and DN-MEK1 adenoviruses, which also express EGFP, were generated by packaging in 293A cells. BRaf constructs (WT and V599E) were kindly provided by Dr. Deborah K. Morrison (NCI-Frederick, Frederick, MD) and were cloned into the EGFP expressing shuttle vector pAdTrack-CMV. The EGFP-R-Ras constructs (WT and 38VY66F) were generously provided by Dr. Elena Pasquale (The Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA). All viruses and constructs co-expressed EGFP to allow identification of infected or transfected neurons.

Neuron culture and gene expression

Hippocampal explants were prepared from E18 Sprague-Dawley rat embryos and seeded onto glass chamber slides coated with poly-D-lysine (0.5 μg/μl, Sigma) and laminin (20 μg/ml, Sigma). Explants were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and 2 mM L-glutamine (all obtained from Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Dissociated hippocampal neurons were dissected from E18 rat embryo, digested with 0.1% trypsin for 15 min at 37 °C, followed by trituration with Pasteur pipettes in the neurobasal medium and plated onto plastic dishes coated with poly-D-lysine (0.1 μg/ul) at a density of 106 neurons /35 mm dish.

To express constitutively active (CA) and dominant-negative (DN)-MEK1 mutant proteins, hippocampal neurons were infected with adenoviruses carrying these genes at a MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) of 100 on the day of plating. To express B-Raf and R-Ras mutants, hippocampal neurons were transfected using Amaxa Nucleofector (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD). For each construct, 1×106 neurons were suspended in 100 μl of rat neuron nucleofector solution with 3 μg DNA and electroporated using program G-13. Transfected neurons were plated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum on glass chamber slide coated with poly-D-lysine (0.5 μg/μl) and laminin (20 μg/ml). Two hours after plating, the medium was replaced with neurobasal medium containing B-27 supplement and glutamine. All the neurons were maintained for 4 days until neurites and growth cones were positive with GFP fluorescence, identifying the infected or transfected neurons and neurites. Dissociated neuron cultures (106/35 mm dish) were used for western blot analysis to detect protein expression. Explants cultures were used to examine the effect of ephrins on growth cone. GFP-positive neurites were quantified on a Zeiss microscope equipped with epifluorescence (Axiovert 200M).

Growth cone collapse assay

The hippocampal explants were stimulated for 15 minutes with 0.2-2 μg/ml ephrin-A5-Fc (preclustered for 2 hours with rabbit anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment at 37 °C in an ephrin-A5-Fc: anti-IgG molar ratio of about 15:1, unless specified otherwise). Controls were incubated with preclustered IgG alone. Explants were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in a cacodylate buffer (0.1 M sodium cacodylate, 0.1 M sucrose, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37 °C as described previously (Guirland et al., 2003). The explants were stained for F-actin with Texas Red® X-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and examined for growth cone morphology under a Zeiss microscope (Axiovert 200M).

Western blot analysis

Primary cultures of dissociated rat hippocampal neurons were treated as indicated and washed with ice cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris.Cl, 1%NP-40, with phosphatase inhibitors (Cocktail 2, Sigma), and protease inhibitors (Roche cocktail, Palo Alto, CA)]. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts (10 μg) of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated with primary antibodies in 1% BSA at 4 °C overnight before detection with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence was detected with a reaction kit from Roche. After initial blot, membranes were stripped by using a membrane stripping kit Western Re-Probe (Genotech, St. Louis, MO) and then reprobed with different antibodies. Antibodies used are the following: anti-phospho-Erk1/2, anti-Erk1/2, anti-phospho- JNK, anti-JNK, anti-phospho-Akt, and anti-Akt (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-phosphotyrosine, clone 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and anti-EphA3 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA).

PKA activity assay

PKA activity assay was performed with a PKA assay kit from Promega (Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 × 107 treated neurons were suspended in 0.5 ml PKA extraction buffer and homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer on ice. 10 μl lysate were incubated with PKA specific substrate Kemptide for 30 min at 30 °C in a final volume of 25 μl. The reaction was stopped by heating at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Phosphorylated Kemptide was separated from non-phosphorylated on 0.8% agarose at 100 V for 20 min, by moving toward the anode, and the gel was photographed on a UV transilluminator.

RESULTS

Ephrin-A5 induces hippocampal growth cones collapse

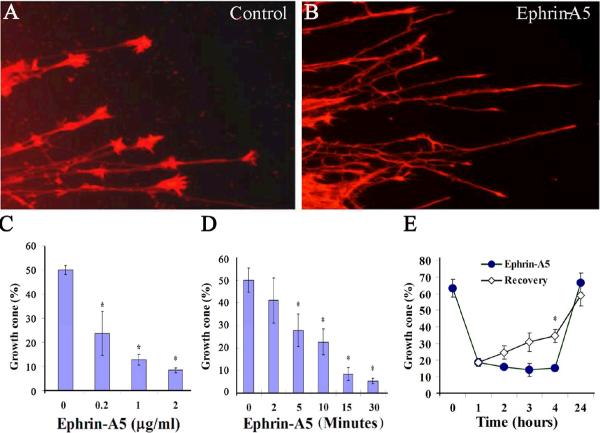

To study signaling mechanisms underlying axon guidance functions of ephrin-A5, we examined effects of ephrin-A5 on hippocampal growth cones. E18 rat hippocampi were dissected and cut into small explants. The explants were then seeded in chamber slides coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin in neural basal medium supplemented with B27. After 24 hours of culture, the explants extend neurites with prominent growth cones. The cultures were then treated with various concentrations of ephrin-A5 for different time periods (Fig. 1). These studies showed that ephrin-A5 induced collapse of about 50% of the growth cones at 0.2 μg/ml (Fig. 1C). By 2 μg/ml ephrin-A5, over 80% of the growth cones were collapsed compared to the control explants. In the presence of 0.2 μg/ml ephrin-A5, growth cones started to collapse at about 5 minutes, and the process was complete by about 15 minutes (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Ephrin-A5 induces hippocampal growth cone collapse.

Hippocampal explants from rat E18 embryos were cultured in neurobasal media for 24 hours. The cultures were treated with preclustered ephrin-A5 for indicated time and concentration. Equal amounts of anti-Fc antibody alone were used as control. (A and B) Hippocampal explants treated with control or 1 μg/ml ephrin-A5, respectively, for 15 minutes. The explants were stained for F-actin with Texas Red® X-phalloidin and examined for growth cone morphology under a Zeiss fluorescence microscope. (C) Higher concentrations of ephrin-A5 increase the percent of collapsed growth cones. Explants were treated with various concentrations of ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. (D) The time course of ephrin-A5 (0.2 μg/ml)-induced growth cone collapse. Error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05 for ephrin-A5 treated versus control by t-test (n ≥3 independent experiments). (E) Growth cone recovery after the ephrin-A5 treatment. In each experiment, ≥ 200 growth cones were quantified. “Growth cones (%)” on the Y-axis in (C-E) (and in the following figures unless indicated otherwise) represents percent of hippocampal neurites with growth cones. Ephrin-A5 causes a significant reduction in the percent of neurites with growth cones.

To address a potential concern that growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5 is a toxic effect, we performed two different recovery experiments. In these experiments, the axons were treated for 1 hour to allow the full effects of any potential toxicity. In the first experiment, the ligand was removed after 1 hour, and replaced with fresh culture medium. At different times, the culture was fixed and the percent of axons with growth cone quantified. This analysis showed that significant number of growth cones had recovered by 4 hours after ephrin-A5 removal (Fig. 1E). By 24 hours, growth cones were fully restored (Fig. 1E). In the second experiment, the ligand was left in the medium and growth cone recovery was monitored over time. In the presence of the ligand, no recovery was observed by 4 hours. However, full recovery was achieved in 24 hours (Fig. 1E). These experiments indicate that ephrin-A5 does not cause non-specific toxicity in neurons, since changes in growth cone morphology are reversible.

Ephrin-A5 inhibits Erk activity in primary hippocampal neurons

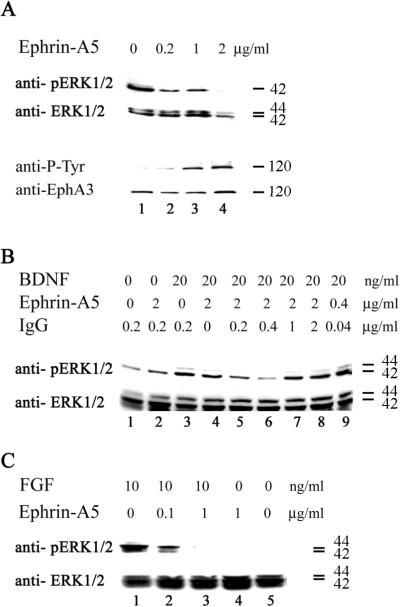

It has been shown previously that ephrins inhibit Erk activity in cultured cells (Elowe et al., 2001; Miao et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2003). To examine whether ephrin-A5 regulated Erk activity in primary neurons, cultured embryonic day (E)18 rat hippocampal neurons were treated with ephrin-A5. Basal Erk activity was significantly inhibited by ephrin-A5 even at the concentration of 0.2 μg/ml, correlating with the appearance of phospho-tyrosine containing proteins that correspond to Eph receptors (Fig. 2A). To examine whether ephrin-A5 also inhibited Erk activation by growth factors, the cultured neurons were treated with BDNF in the presence or absence of ephrin-A5 (Fig. 2B). Since it has been reported that ephrins need to be artificially cross-linked to be active (Davis et al., 1994; Stein et al., 1998; Huynh-Do et al., 1999; Pabbisetty et al., 2007), we also investigated how cross-linking affects regulation of Erk activity. Cultured hippocampal neurons were treated with BDNF with or without ephrin-A5 (with different cross-linking ratio with anti-Fc IgG). This analysis showed that 20 ng/ml of BDNF activated Erk activity in the hippocampal neurons, in the absence of ephrin-A5 (Fig. 2B, lane 3). In the absence of cross-linking IgG, ephrin-A5 only weakly inhibited Erk activity (Fig. 2B, lane 4). The most effective cross-linking ratio for ephrin-A5 is 2 μg ephrin-A5 to 0.4 μg anti-Fc IgG, which corresponded to a molar ration of about 15:1 (Fig. 2B, lane 6). A lower ratio also reduced the effectiveness of ephrin-A5 to inhibit Erk activity, possibly due to overabundance of the cross-linking antibody resulting in smaller ephrin-A5 aggregates. This analysis demonstrated that ephrin-A5 aggregation enhanced its activity and that the ligand also inhibited Erk activation by BDNF. To examine whether ephrin-A5 also inhibited Erk activation by other growth factors, we tested the ability of FGF to activate Erk in the presence of clustered ephrin-A5 (Fig. 2C). FGF completely failed to activate Erk in the presence of 1 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5 (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Ephrin-A5 inhibits Erk1/2 activity.

(A) Dissociated hippocampal neurons were exposed to different concentration of clustered ephrin-A5 or anti-Fc control for 15 minutes. Lysate were analyzed with Western blot using anti-phospho-Erk1/2 and anti-phospho-tyrosine antibodies. The membranes were stripped and reprobed for total Erk and Eph-A3 protein levels. Decreased Erk activity correlated with increased Eph receptor activation. (B) Hippocampal neurons were serum-starved for 2 hours and then incubated with BDNF and clustered ephrin-A5 as indicated. BDNF alone activated Erk (line 3). Ephrin-A5 was preclustered with anti-Fc antibody at different ratio (lane 3-8). Without anti-Fc antibody, ephrin-A5 failed to reduce Erk activity (lane 4). With cross-linking, ephrin-A5 was able to inhibit Erk activity and this effect maximized at 2 μg:0.4 μg ratio (molar ratio about 15:1) (lane 6). (C) Erk activity induced by FGF was also inhibited by ephrin-A5. Numbers at the right of each panel indicate size of the proteins detected (kDa).

Inhibition of Erk activity is not required for ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse

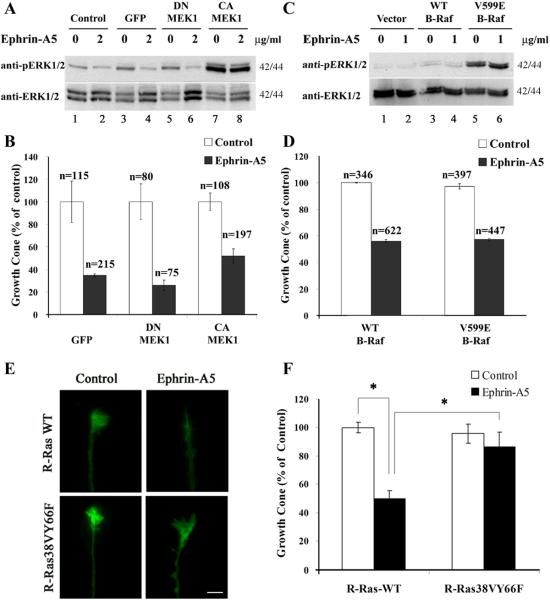

To directly test whether regulation of Erk activity was critical to growth cone collapse induced by ephrin-A5, effects of constitutive Erk activation were examined. Adenoviruses carrying either a constitutively active MEK1 (CA-MEK1) or a dominant-negative MEK1 (DN-MEK1) were used to activate or inhibit Erk in hippocampal neurons. A mock infection with no viruses and an infection with adenoviruses carrying only EGFP were used as controls. These studies showed that the CA-MEK1 virus induced significantly higher Erk activity even in the absence of any growth factors, and that cross-linked eprhin-A5 showed no inhibition of the activity (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 & 8), consistent with previous findings that ephrins inhibit Erk activity upstream of Mek1 (Elowe et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2003). In contrast, no significant effects on basal Erk activity were observed with viruses carrying either EGFP or the DN-MEK1 (Fig. 3A, lane 3-6). When infected neurons were treated with cross-linked ephrin-A5, neither virus significantly prevented growth cone collapse induced by the ligand (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Inhibition of Erk activity is not required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

(A, B) Expression of constitutively active MEK1 (CA-MEK1) does not prevent ephrin-A5-incuced growth cone collapse in hippocampal neurons. Neurons were infected with indicated adenoviruses (control: no infection; GFP: adenoviruses expressing only EGFP; DN-MEK1: adenoviruses expressing dominant negative-MEK1 and EGFP; CA-MEK1: adenoviruses expressing constitutively-active MEK1 and EGFP) for 4 days. Infected neurons were then stimulated with or without 2 μg/ml of cross-linked ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes when 90% of neurons expressed EGFP as an infection marker. (A) CA-MEK1 infected neurons showed high level of Erk activity, which was not inhibited by ephrin-A5 (compare lane 7 and 8). (B) Infected explants were stained for F-actin and quantified for growth cone. Ephrin-A5 treatment caused significant collapse in neurons infected with adenoviruses expressing control EGFP, and DN-MEK1 and CA-MEK1. A slightly higher percent of growth cones were observed in explants infected with CA-MEK1 viruses, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. (C - F) Rat hippocampal neurons were transfected with the indicated B-Raf or R-Ras constructs that also expressed EGFP and stimulated with preclustered 1 μg/ml ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. Neurons were stained for F-actin for quantification. Only GFP-positive growth cones were quantified. (C) Neurons transfected with V599E-B-Raf expressed high Erk activity and the activity was not reduced by ephrin-A5 treatment (compare lane 5 and 6). (D) Ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse in both WT and V599E-B-Raf transfected hippocampal neurons. (E) Expression of R-Ras38VY66F but not the wild type prevents growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5. (F) Quantification of effects of wild type and mutant R-Ras on ephrin-A5 activity. Student t-test, *P<0.05.

To further clarify the roles of Erk activity in ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse, we also examined effects of Erk activity by expression of constitutively active B-Raf gene. Both the wild type B-Raf and the constitutively active mutant V599E-B-Raf were cloned into an expression vector that also carries an EGFP gene (see Materials and Methods for details). Similar to CA-MEK1, V599E-B-Raf induced high levels of Erk activity that could not be inhibited by ephrin-A5 (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 & 6). Collapse assay of transfected neurons showed that V599E-B-Raf did not block growth cone collapse induced by ephrin-A5 (Fig. 3D). To validate the transfection assays used here, a constitutively active R-Ras mutant (R-Ras38VY66F) which has been shown to block ephrin-A1 and B1-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse (Dail et al., 2006) was used as a positive control. Consistent with the previous study, the R-Ras mutant prevented ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse, while wild type R-Ras showed no effect, as expected (Fig. 3E and F). These data strongly suggest that inhibition of Erk activity is not necessary for ephrin-induced growth cone collapse in hippocampal neurons.

Erk activation is also not required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse

It has been shown previously that Erk activation is required for Semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse (Campbell and Holt, 2003). Although ephrin-A5 inhibits Erk activity, it is still possible that transient activation of Erk is required for growth cone collapsed by ephrin-A5. Therefore we also determined effects of inhibition of the Erk pathway on ephrin-induced growth cone collapse. Hippocampal neurons were pre-incubated with MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 or MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 before ephrin-A5 treatment. Both inhibitors inhibited the enzyme by a non-competitive mechanism (Favata et al., 1998). While both inhibitors inhibited Erk activity, neither inhibitor blocked growth cone collapse induced by ephrin-A5, even at 20 μM of U0126 or 40 μM of PD98059 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggest that Erk activation is also not required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

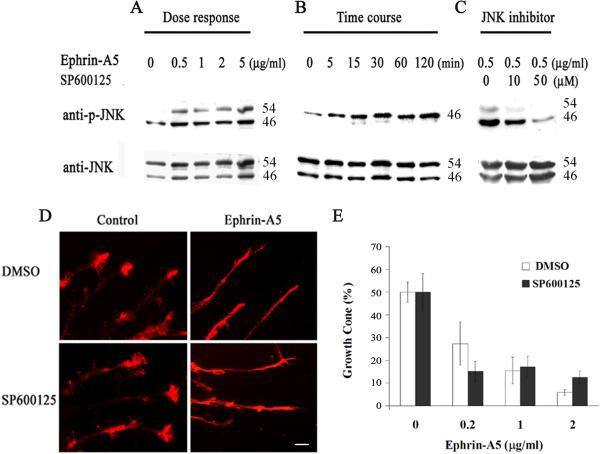

Ephrin-A5 activates JNK but does not require the activity for growth cone collapse

A previous report showed that JNK was activated by ephrin-B1 (Stein et al., 1998), we tested whether ephrin-A5 also activated JNK and whether JNK activity was required for the growth cone collapse function. Ephrin-A5 indeed activated JNK in a dose and time-dependent manner. At 0.5 μg/ml, ephrin-A5 significantly activated JNK (Fig. 4A). The increase in JNK activity was apparent by 5 minutes and continued up to 2 hours, the latest time point analyzed (Fig. 4B). To assess whether JNK activation mediated ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse, effects of a JNK inhibitor SP600125 was examined. SP60015 inhibits JNK by competing with ATP binding (IC50 = 40 nM) (Bennett et al., 2001; Han et al., 2001). At 50 μM, the compound severely inhibited JNK activation (Fig. 4C). However, the inhibitor showed no significant effects on the percent of growth cones that are collapsed by ephrin-A5 (Fig. 4D & E), indicating that JNK activity was not required.

Figure 4. Ephrin-A5 activates JNK but does not require the activity for growth cone collapse.

(A) Hippocampal neurons were treated with various concentrations of clustered ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes and analyzed for levels of phospho-JNK. Total JNK levels were assessed by stripping and re-probing the blot with an anti-total JNK antibody. (B) Hippocampal neurons were treated with 0.5 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5 for different time periods. (C) Ephrin-A5 failed to activate JNK in the presence of a JNK inhibitor SP6000125. Hippocampal neurons were pretreated with SP600125 for 15 minutes at indicated concentrations before the addition of 0.5 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. (D and E) Inhibition of JNK activity does not prevent ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. Hippocampal explants were pretreated with DMSO or 25 μM SP600125 for 15 minutes before addition of ephrin-A5. Error bars represent the standard errors from three experiments. Ephrin-A5 treatment caused significant collapse, with or without SP600125.

Staurosporine-sensitive kinases mediate ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse

To identify pathways that do mediate ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse, we tested the effects of a cell-permeable, broad-spectrum inhibitor of protein kinases, Staurosporine. Staurosporine is an alkaloid isolated from the culture broth of Streptomyces staurosporesa. The compound inhibits kinases by preventing ATP binding (Ruegg and Burgess, 1989). We showed that it effectively inhibited ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse and enhanced the size and complexity of the growth cones (Fig. 5 and Suppl. Fig. 2). In the presence of Staurosporine, the growth cones had very long filopodia (Fig. 5A and Suppl. Fig. 2). With increasing concentrations of Staurosporine, growth cones were gradually protected from the collapsing effects of ephrin-A5 (Fig. 5A and B). By 10 μM, ephrin-A5 failed to collapse hippocampal growth cones completely (Fig. 5B). It is possible that Staurosporine inhibits multiple kinases, which lead to a freezing of growth cones, thereby preventing growth cone collapse. To test for this possibility, we observed growth cone dynamics in the presence of the inhibitor using time-lapse video microscopy. The growth cones maintained dynamic changes in the presence of 10 μM Staurosporine, and continued to grow even when ephrin-A5 was added to the culture (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the inhibitor blocked specific biochemical processes leading to growth cone collapse. In contrast, in the absence of Staurosporine, ephrin-A5 induced both collapse of the growth cone and a retraction of the neurites (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 5. Staurosporine prevents ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

(A) Fluorescence images of hippocampal explants pretreated with control or 1 μM Staurosporine for 20 minutes before ephrin-A5 treatment (0.5 μg/ml). Bars = 10 μm. (B) Staurosporine prevents ephrin-A5-induced collapse in a dose-dependent manner. Error bars represent SEM. * indicates significant difference from samples without Staurosporine treatment (P < 0.05; t-test).

Staurosporine is known to inhibit several protein kinases including protein kinase A (PKA) (IC50 = 7 nM), protein kinase C (PKC) (IC50 = 0.7 nM) (Tamaoki et al., 1986; Matsumoto and Sasaki, 1989), myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (IC50 = 1.3 nM), protein kinase G (PKG) (IC50 = 8.5 nM) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (IC50 = 20 nM) (Yanagihara et al., 1991). First we sought to determine whether inhibition of PKA was responsible for blocking ephrin-A5 activity. The growth cone collapse assay was performed in the presence of a PKA inhibitor KT5720, which prevents cAMP binding to PKA (Kohda and Gemba, 2001). Hippocampal explants were pretreated with KT5720 for 20 minutes at indicated concentrations, and then treated with pre-clustered ephrin-A5 (0.5 μg/ml) or IgG for 15 minutes. DMSO was used as solvent controls. This analysis showed that KT5720 had no effect on ephrin-A5 induced growth cone collapse over a wide range of concentrations, although the inhibitor clearly inhibited PKA activity in the neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting that inhibition of PKA activity was probably not responsible for the Staurosporine effects. Since high concentration of cAMP levels have been shown to favor attractive turning (Lohof et al., 1992; Ming et al., 1997; Nishiyama et al., 2003; Henley and Poo, 2004) and promote neurite outgrowth (Kao et al., 2002), we determined that whether PKA activation would counteract the effects of ephrin-A5. Explants were pretreated with the PKA activator Sp-cAMPS, a cAMP analog (Dostmann et al., 1990; Takuma and Ichida, 1991) before addition of ephrin-A5. No significant effects were observed in the presence of Sp-cAMPS (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that regulation of PKA pathway was not essential for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

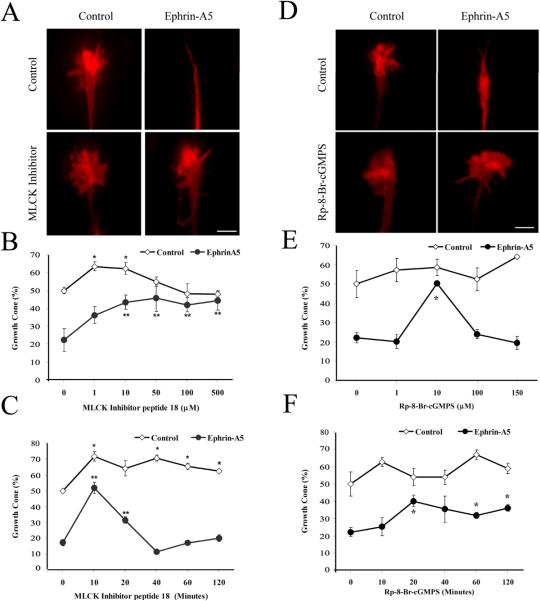

MLCK and PKG mediate ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse

We next tested effects of MLCK, an enzyme that was also inhibited by Staurosporine. A MLCK inhibitor, peptide 18, has been shown to specifically inhibit MLCK by competing with substrate binding (Lukas et al., 1999). In the presence of inhibitor peptide 18, significant inhibition to ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse was observed (Fig. 6A-B). With increasing concentration of the peptide inhibitor, nearly 90% of ephrin-A5 effect could be blocked (Fig. 6B). The inhibitor peptide alone slightly increased the percentage of growth cones (Fig. 6B & C), consistent with a stabilizing effect on growth cones. A pre-incubation of the peptide inhibitor with hippocampal neurons for about 10 minutes had the best effect (Fig. 6C). Prolonged incubation before ephrin-A5 treatment resulted in the loss of inhibitory activity, possibly due to peptide degradation, although the exact mechanism was not known at present. Taken together, these results show that Staurosporine-sensitive kinases such as MLCK may be responsible for the inhibitory effects of Staurosporine.

Figure 6. A MLCK and PKG inhibitors prevent ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

(A) Hippocampal explants were pre-incubated with 50 μM MLCK inhibitor peptide 18 for 10 minutes before treated with 0.5 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. Explants were fixed and visualized with rhodamine-phalloidin. (B) Dose-response effect of MLCK inhibitor peptide 18. (C) Time-dependent effect of MLCK inhibitor peptide 18 (50 μM). Error bars represent SEM. In the absence of ephrin-A5, the inhibitor caused a significant increase in the number of growth cones compared to the DMSO controls (*P<0.05, t-test). The inhibitor also significantly inhibited ephrin-A5 activity in inducing collapse, as compared with no inhibitor controls (**P < 0.05, t-test). (D) Hippocampal explants were pre-incubated with 10 μM PKG inhibitor Rp-8-BrcGMPS for 20 minutes before treatment with 1 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. Ephrin-A5 failed to induce growth cones collapse in the presence of PKG inhibitor. (E) Dose-response effects of Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. Hippocampal explants were pretreated with various concentrations of Rp-8-Br-cGMPS for 20 minutes then stimulated with or without 1 μg/ml ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. Error bars refer to SEM. *significant differences from the samples without pretreatment with Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. (F) Time-dependent effect of Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 μM). *Significantly different from the samples without pretreatment with Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. (P < 0.05; t-test).

Previous studies have implicated the cGMP-regulated kinase PKG, also inhibited by Staurosporine, in mediating retinal growth cone responses to ephrin-B1 (Mann et al., 2003) and Semaphorin 3A (Dontchev and Letourneau, 2002). To examine the role of PKG in ephrin-A5 induced collapse, PKG specific inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS was bath-applied 20 minutes before the addition of the ephrin-A5. Rp-8-Br-cGMPS blocks cGMP binding to PKG (Butt et al., 1990). Pre-incubation of 10 μM Rp-8-Br-cGMPS abolished the collapse response of hippocampal growth cones exposed for 15 minutes to 1 μg/ml of ephrin-A5 (Fig 6D-F). Higher concentrations led to a loss of inhibition, possibly due to non-specific inhibition of other kinases. Pre-incubation longer than 20 minutes in 10 μM inhibitor did not significantly enhance the inhibitory effects, indicating that a 20 min incubation was sufficient to allow enough inhibitor to enter the cells and inhibit most of PKG activity (Dontchev and Letourneau, 2002; Mann et al., 2003). These results suggest that PKG activity is also required for ephrin-A5 collapsing effects. Inhibitors for the other Staurosporine-sensitive kinases (PKC, CaMKII) did not yield any specific effects (data not shown), although further studies are necessary to assess their contribution to ephrin-A5 signaling. Taken all these data together, effects of Staurosporine may be exerted, at least in part by inhibiting MLCK and PKG activity.

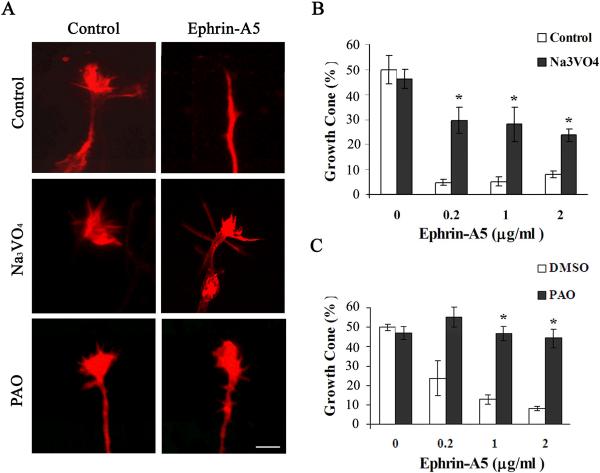

Protein tyrosine phosphatase activity participates in the regulation of growth cone morphology by ephrin-A5

Eph receptors are phosphorylated upon activation by ephrin-A5, and the inactivation of the receptors likely requires dephosphorylation of the receptors. In addition, downstream mediators are likely also regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. We therefore tested whether inhibitors to protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) regulate growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5. Two PTP inhibitors, sodium vanadate and PAO, were used to assess roles of PTP. Sodium vanadate is a competitive inhibitor of phosphatases and PAO inactivates PTPs by chemically reacting with the enzymes (Seargeant and Stinson, 1979). Both compounds inhibited growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5 (Fig. 7). In the presence of sodium vanadate, the growth cones continued to extend, indicating that the phsophatase inhibitors did not cause “freezing” of the cellular machinery required for collapse (Suppl. Fig. 2). These observations strongly suggest that PTP activity is required for ephrin-A5-induced growth collapse.

Figure 7. PTP activity is required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

(A) Hippocampal explants were pretreated with 250 μM Na3VO4 or 50 μM PAO for 30 minutes before treatment with 0.2 μg/ml clustered ephrin-A5. (B and C) Percent of neurites with growth cones remained in explants treated with ephrin-A5 in the presence or absence of inhibitors pretreatment (250 μM Na3VO4 or 50 μM PAO for 30 minutes). *Significantly different from samples without inhibitors (P < 0.05; t-test).

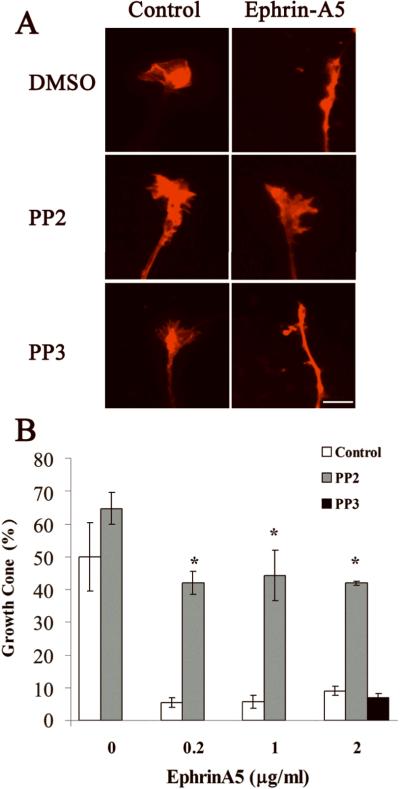

Src kinases are required for ephrin-A5-induced growth collapse

It has been shown that Src kinases associate with Eph receptors, and are required for repulsive guidance of retinal growth cones by ephrin-A5 (Knoll, 2004; Wong et al., 2004). We tested whether Src kinases are also required for hippocampal growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5. The ability of ephrin-A5 to induce growth cone collapse was significantly inhibited by the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (Fig. 8). PP2 is a potent and selective inhibitor of the Src family kinases, acting either as a competitive or non-competitive inhibitor for different members of the family (Karni et al., 2003). In contrast, a negative control compound, PP3, which did not inhibit the Src kinases, showed no effect on ephrin-A5-induced collapse (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Src inhibitor PP2 prevents ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

(A) Fluorescence images of hippocampal growth cones pretreated with DMSO control, 1 μM PP2 or 1 μM negative control PP3 for 30 minutes before treatment with 0.2 μg/ml ephrin-A5 for 15 minutes. PP2, but not PP3, preserved growth cone from ephrin-A5-induced collapse. (B) Percent of neurites with growth cones in the explants treated with ephrin-A5 with pretreatment of DMSO control, PP2, and PP3. *Significantly different from the control treatment (P < 0.05; t-test).

We also examined whether the phosphoinositide-3 (PI-3) kinase was involved in mediating ephrin-A5 activity, since the activity appeared to be required for ephrin-A5 induced retinal growth cone collapse (Wong et al., 2004). Activation of PI3 kinase led to the phosphorylation of AK mouse transforming (Akt) kinase, which could be detected using an anti-phospho-Akt antibody (Dhawan et al., 2002). Treatment of hippocampal neurons with ephrin-A5 did not lead to the activation of Akt (Supplementary Fig. 4A), indicating that ephrin-A5 function did not require activation of the PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway. To further test the roles of PI-3 kinase, effects of two inhibitors, wortmannin (Kd = 5 nM), which irreversibly blocks the catalytic site by covalent bonding (Wipf and Halter, 2005), and LY294002 (KD = 1.4 μM) that competitively blocks the ATP-binding (Vlahos et al., 1994), were examined. At concentrations that were effective in retinal neurons (Wong et al., 2004), neither inhibitor showed any effects on ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse (Supplementary Fig. 4B).

Discussions

In this study, we showed that ephrin-A5 induced efficient collapse of hippocampal growth cones. Under the conditions in our studies, the cultured E18 rat embryonic hippocampal explants grew dense neurites in radial fashion, and about half of these neurites had growth cones. The reason why not every neurite has a growth cone is not known. It may reflect the dynamic nature of growth cones, which expand and contrast continuously (Gallo and Pollack, 1997). It is also possible that a subpopulation of the neurons grow neurites without growth cones. Thus, a combination of different factors may contribute to the lack of growth cones on some neurites. Ephrin-A5 stimulation leads to a loss of most growth cones, leaving only about 5 to 15% of neurites with growth cones, depending on the concentration of the ligand and exposure time. Using this convenient assay, we demonstrate that ephrin-A5 inhibits Erk but activates JNK in primary hippocampal neurons. However, the regulation of these two biochemical activities is not critical for growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5. In addition, we have determined that several enzymes, MLCK, PKG, PTP as well as the Src family kinases, are required for ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse. Furthermore, this study reveals that PKA and PI-3 kinase pathways are not central to this process.

Roles of Erk and JNK-MAP kinases in ephrin-induced growth cone collapse in hippocampal neurons

We show here that ephrin-A5 inhibits the basal Erk activity and activity induced by both BDNF and FGF. Several earlier studies have reported that ephrin-A1 and ephrin-B1 both inhibit Erk activity in established cells lines (Elowe et al., 2001; Miao et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2003; Ojima et al., 2006), consistent with our present studies. However, several other reports showed that ephrin-A1 activated Erk in several cell lines (Pratt and Kinch, 2002; Tang et al., 2007), and ephrin-B2 stimulated Erk activity in EphB1-overexpressing CHO cells (Vindis et al., 2003; Vihanto et al., 2006). While it is not clear what leads to these contradicting findings, it is possible that established cell lines may have accumulated as yet undefined molecular changes that alter responses to ephrins. Differences are also possibly due to cell type-specific expression of different signaling molecules that regulate Erk activity. These observations suggest that ephrins could exert opposite biochemical effects depending on specific cellular environment, and also raise the critical question of what are the physiological consequences of ephrin stimulation. Using primary hippocampal neurons, we showed that ephrin-A5 consistently inhibits Erk activity, indicating that Erk inhibition is likely to be physiologically relevant, since primary cells are less likely to accumulate artifactual molecular changes during cell culture process.

Studies using NG108 cells showed that down-regulation of Erk activity by ephrin-B1 is mediated through interaction of the receptor EphB2 with RasGAP, an enzyme which activates Ras GTPase (Elowe et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2003). It is likely that RasGAP also mediates ephrin-A5 induced Erk inhibition in hippocampal neurons. What biological functions of ephrins are regulated by Erk activity changes is not clear at present. Previous studies in NG108 cells showed that blocking down-regulation of Erk activity with a dominant-negative RasGAP also blocked retraction of cellular processes induced by ephrin-B1 (Elowe et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2003), suggesting that Erk down-regulation was necessary for ephrin-B1-induced process retraction. However, an alternative explanation is that RasGAP also regulates other small GTPases such as R-Ras that are critical for ephrin-induced growth cone collapse. Consistent with this notion, a recent study showed that R-Ras activity was inhibited by ephrin-A5, and this inhibition was required for the collapsing activity, since expression of a constitutively active R-Ras blocked ephrin-A5-induced collapse (Dail et al., 2006). In contrast, a constitutively active H-Ras, which activates Erk but not the R-Ras pathway, failed to prevent ephrin-A5-induced collapse (Dail et al., 2006), consistent with our observations in this study that both constitutively active MEK1 and B-Raf which activate Erk activity failed to block ephrin-A5-induced collapse. These observations together suggest that at least in the hippocampal neurons, down regulation of Erk activity is not critical for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse.

Previous studies showed that Semaphorin 3A and Slit2 required Erk activation to induce retinal growth cones collapse (Campbell and Holt, 2003; Piper et al., 2006). Our studies show that Erk activation is not an integral part of the pathway leading to growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5 in the hippocampal neurons. Thus, it is likely that different guidance molecules or different neurons use distinct pathways to induce growth cone collapse.

Since Erk activity is regulated by ephrins, but this regulation is not required for growth cone collapse in the hippocampal neurons, what is the function of Erk regulation? The answer to this question is currently unknown. However, it is possible that Erk activity participates in subtle modulation of axon guidance not detected in the collapse assay. Another possibility is that the inhibition of Erk activity by ephrins may be responsible for the anti-oncogenic activity of EphA receptors in non-neural (Miao et al., 2001; Bardelli et al., 2003). It is also possible that Erk regulation is important for biological functions yet to be defined. Another interesting issue is whether regulation of Erk activity occurs in the cell soma and the growth cones, and whether different pools are regulated differentially. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

We also showed in this study that ephrin-A5 activates JNK. Several studies reported that ephrin-B1 activates JNK, through interaction with Nck (Stein et al., 1998; Becker et al., 2000). However, JNK activity is not required for ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse, since an inhibitor, SP600125, at a concentration which successfully inhibited JNK activity in these neurons, showed no effects on ephrin-A5-induced collapse, suggesting that JNK activation may be important for functions other than growth cone collapse.

Signaling molecules and pathways that are required for ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse

In contrast to inhibitors of the Erk and JNK pathways, Staurosporine prevented ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. In addition, Staurosporine allowed growth of filopodia even in the presence of ephrin-A5, indicating that the inhibitor blocks kinases required for growth cone collapse. Since Staurosporine is a broad-spectrum inhibitor, we examined effects of inhibiting specific kinases. These analyses identify several kinases that are required for the ephrin-A5-induced collapse. A specific MLCK Inhibitor Peptide 18 (Lukas et al., 1999) inhibits collapse by ephrin-A5. It has been shown that Eph receptor activation modulates the activity of Ephexin leading to Cdc42/Rac1 and PAK1 inhibition (Wahl et al., 2000; Shamah et al., 2001). MLCK is negatively regulated by Cdc42/Rac1 activity via PAK1 (Sanders et al., 1999). Thus, it is likely that Eph receptor activation inhibits Cdc42/Rac1 and PAK1, leading to the activation of MLCK, which in turn regulates growth cone collapse. The function of MLCK is likely to be mediated through the phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) leading to myosin activation (Luo, 2002). This is consistent with several previous studies which have demonstrated that activation of RhoA and its downstream target Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) is also required for growth cone collapse induced by ephrins and semaphorins (Sanders et al., 1999; Wahl et al., 2000; Shamah et al., 2001; Dontchev and Letourneau, 2002; Gallo et al., 2002; Luo, 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002), since ROCK can also phosphorylate MRLC (Amano et al., 1996; Ueda et al., 2002). In addition, ROCK may promote MRLC activation by inhibiting activation of MRLC phosphatase (Kaibuchi et al., 1999). Our observations reported here provide additional evidence that signaling mechanisms leading to myosin activation play key roles in repulsive axon guidance.

Our results also show that cGMP-activated PKG is involved in ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. The PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS has the strongest effect on ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse at 10 μM (Fig. 6E). Higher concentrations had no effects. The mechanisms underlying these differential effects are currently unknown. It is possible that at higher concentrations, the inhibitor may exert non-specific inhibition on targets required to maintain growth cone morphology in the presence of ephrin-A5. The observation that inhibiting PKG activity blocks ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse is consistent with the previous finding that PKG activity is required in ephrin-B1-induced Xenopus retina and Semaphorin 3A-induced DRG growth cone collapse (Dontchev and Letourneau, 2002; Mann et al., 2003). Increases in intracellular concentration of cGMP has been shown to switch axon repulsion to attraction by Semaphorin 3D, the chemokine SDF-1, and a GABA(B) receptor agonist baclofen (Song et al., 1998; Xiang et al., 2002). In addition, cGMP signaling has been shown to be required for growth cone repulsion mediated by netrin-DCC-UNC5 interaction in Xenopus spinal cord neurons (Nishiyama et al., 2003). Thus, activation of PKG could lead to either attraction or repulsion, depending possibly on the interplay of intracellular signaling pathways (Nishiyama et al., 2003). PKG may affect ion channels, Ca2+ release, and myosin contractility to regulate growth cone motility (Silveira et al., 1998; Hofmann et al., 2000). Our findings are consistent with the idea that PKG signaling is important in growth cone guidance (Ming et al., 1997; Song et al., 1998). It also indicates that different repulsive regulators, ephrin-A5, ephrin-B1, netrin-1 and Semaphorin 3A may share common downstream signaling pathways. Since Staurosporine exhibits potent inhibition of ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse and also inhibits MLCK and PKG, we conclude that effects of Staurosporine may be in part due to MLCK and PKG inhibition. However, Staurosporine generates enlarged and complex growth cone morphology (Fig. 5), but neither MLCK nor PKG inhibitor produces this effect. A combination of these two inhibitors also failed to generate this morphology (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that the complex morphology is generated by Staurosporine inhibition of other unidentified targets.

Two inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) activity, showed profound inhibition of growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5, indicating that PTP activity plays key roles in Eph receptor signal transduction. The identity of this activity is currently not clear. Previous studies have identified small molecular weight phosphatases and a phosphotyrosine phosphatase receptor, PTPRO, that associates with Eph receptors and serve to terminate receptor activation (Parri et al., 2005; Shintani et al., 2006). These phosphatases are unlikely to be the activity needed for growth cone collapse, since inhibition of these phosphatases should promote, rather than inhibit the collapse. A different PTP, the SH2-domain containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase Shp2, has been shown to associate with EphA2 in PC3 cells derived from a prostate cancer (Miao et al., 2000), and in hippocampal neurons (G. Shi and R. Zhou, unpublished observations). However, whether Shp2 activity is required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse is currently under investigation.

Previous studies have shown that Src family kinases are associated with Eph receptors and mediate retinal axon repulsion by ephrin-A5 (Knoll, 2004; Wong et al., 2004). We show here that the Src family kinases are also required for ephrin-A5-induced hippocampal growth cone collapse. This observation suggests that certain downstream pathways and molecules are shared in different types of neurons in ephrin-induced growth cone collapse.

Other pathways that are not required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse

Inhibition of two other pathways analyzed does not seem to interfere with ephrin-A5 signal transduction leading to growth cone collapse. PKA and PI3-K have been implicated in regulating axon migration (Igarashi and Komiya, 1991; Lohof et al., 1992; Zheng et al., 1994; Ming et al., 1997; Song et al., 1997; Xiang et al., 2002; Mikule et al., 2003; Nishiyama et al., 2003; Henley and Poo, 2004; Wong et al., 2004; Wen and Zheng, 2006). Our studies show that both inhibitors and activators of PKA lack influence on growth cone collapse by ephrin-A5, and inhibitors to PI3-K also have no effects, suggesting differences in mechanisms underlying guidance in different types of neurons or by different guidance cues. What is interesting is that ephrin-A5 stimulation appears to down-regulate PKA activity (Supplementary Fig. 3C), suggesting that PKA regulation may play a role in other neuronal functions.

Our studies here indicate that ephrin-A5 regulates multiple signal transduction pathways, implicating functions in many different biological and pathological processes. In addition, we have shown that activation of only a subset of these pathways, namely Src, but not Erk, JNK, PKA, or PI-3 kinase, is required for hippocampal growth cone collapse. This study further demonstrates that phosphotyrosine phosphatase, PKG, and MLCK activities are required for ephrin-A5-induced growth cone collapse. Future studies are necessary to determine whether these activities are regulated by ephrin-A5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. James Q. Zheng, Dr. Deborah K. Morrison and Dr. Elena Pasquale for generously providing Lim kinase inhibitor, B-Raf and R-Ras constructs, respectively. Research was supported by grants to Dr. Renping Zhou from the National Science Foundation (0516172), NIH (PO1-HD23315) and New Jersey commission on Spinal Cord Research (05B-013-SCR1).

Abbreviations

- CA

constitutively active

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- DN

dominant-negative

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LMW-PTP

low-molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- Na3VO4

sodium orthovanadate

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

- PAO

phenylarsine oxide

- PI3-K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKG

cGMP-dependent protein kinase

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatases

- PTPRO

protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- SDF-1

The chemokine stromal-derived factor 1

- Tyr

tyrosine

References

- Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, Deutsch U, Risau W, Klein R. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rhokinase) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AC, Ziemiecki A. Eph and ephrin signaling in mammary gland morphogenesis and cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2003;8:475–485. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000017433.83226.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardelli A, Parsons DW, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Saha S, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. Mutational analysis of the tyrosine kinome in colorectal cancers. Science. 2003;300:949. doi: 10.1126/science.1082596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker E, Huynh-Do U, Holland S, Pawson T, Daniel TO, Skolnik EY. Nck-interacting Ste20 kinase couples Eph receptors to c-Jun N-terminal kinase and integrin activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1537–1545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1537-1545.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O'Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt E, van Bemmelen M, Fischer L, Walter U, Jastorff B. Inhibition of cGMP-dependent protein kinase by (Rp)-guanosine 3',5'-monophosphorothioates. FEBS Lett. 1990;263:47–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80702-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DS, Holt CE. Apoptotic pathway and MAPKs differentially regulate chemotropic responses of retinal growth cones. Neuron. 2003;37:939–952. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, Brantley D, Fang WB, Liu H, Fanslow W, Cerretti DP, Bussell KN, Reith A, Jackson D, Chen J. Inhibition of VEGF-dependent multistage carcinogenesis by soluble EphA receptors. Neoplasia. 2003;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagni A, Logan M, Klein R, Adams RH. Control of skeletal patterning by ephrinB1-EphB interactions. Dev Cell. 2003;5:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CW, Shao YR, Sahin M, Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Greer PL, Gao S, Griffith EC, Brugge JS, Greenberg ME. Vav family GEFs link activated Ephs to endocytosis and axon guidance. Neuron. 2005;46:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.019. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dail M, Richter M, Godement P, Pasquale EB. Eph receptors inactivate R-Ras through different mechanisms to achieve cell repulsion. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1244–1254. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Gale NW, Aldrich TH, Maisonpierre PC, Lhotak V, Pawson T, Goldfarb M, Yancopoulos GD. Ligands for EPH-related receptor tyrosine kinases that require membrane attachment or clustering for activity. Science. 1994;266:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.7973638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy A, Aubin J, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 forward and reverse signaling are required during mouse development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:572–583. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan P, Singh AB, Ellis DL, Richmond A. Constitutive activation of Akt/protein kinase B in melanoma leads to up-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7335–7342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dontchev VD, Letourneau PC. Nerve growth factor and semaphorin 3A signaling pathways interact in regulating sensory neuronal growth cone motility. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6659–6669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06659.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostmann WR, Taylor SS, Genieser HG, Jastorff B, Doskeland SO, Ogreid D. Probing the cyclic nucleotide binding sites of cAMP-dependent protein kinases I and II with analogs of adenosine 3',5'-cyclic phosphorothioates. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10484–10491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowe S, Holland SJ, Kulkarni S, Pawson T. Downregulation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for ephrin-induced neurite retraction. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7429–7441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7429-7441.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JG, Vanderhaeghen P. The ephrins and Eph receptors in neural development. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu WY, Chen Y, Sahin M, Zhao XS, Shi L, Bikoff JB, Lai KO, Yung WH, Fu AK, Greenberg ME, Ip NY. Cdk5 regulates EphA4-mediated dendritic spine retraction through an ephexin1-dependent mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nn1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Pollack ED. Temporal regulation of growth cone lamellar protrusion and the influence of target tissue. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:929–944. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199712)33:7<929::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Yee HF, Jr., Letourneau PC. Actin turnover is required to prevent axon retraction driven by endogenous actomyosin contractility. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1219–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirland C, Buck KB, Gibney JA, DiCicco-Bloom E, Zheng JQ. Direct cAMP signaling through G-protein-coupled receptors mediates growth cone attraction induced by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2274–2283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02274.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Boyle DL, Chang L, Bennett B, Karin M, Yang L, Manning AM, Firestein GS. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley J, Poo MM. Guiding neuronal growth cones using Ca2+ signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heroult M, Schaffner F, Augustin HG. Eph receptor and ephrin ligand-mediated interactions during angiogenesis and tumor progression. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Ammendola A, Schlossmann J. Rising behind NO: cGMP-dependent protein kinases. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 10):1671–1676. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh-Do U, Stein E, Lane AA, Liu H, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Surface densities of ephrin-B1 determine EphB1-coupled activation of cell attachment through alphavbeta3 and alpha5beta1 integrins. Embo J. 1999;18:2165–2173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, Komiya Y. Subtypes of protein kinase C in isolated nerve growth cones: only type II is associated with the membrane skeleton from growth cones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:751–757. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Putative dual role of ephrin-Eph receptor interactions in inflammation. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:389–394. doi: 10.1080/15216540600756004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro H, Rubinfeld H, Hanoch T, Seger R. Nuclear translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) in response to mitogenic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3742–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaibuchi K, Kuroda S, Amano M. Regulation of the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion by the Rho family GTPases in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HT, Song HJ, Porton B, Ming GL, Hoh J, Abraham M, Czernik AJ, Pieribone VA, Poo MM, Greengard P. A protein kinase A-dependent molecular switch in synapsins regulates neurite outgrowth. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nn840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni R, Mizrachi S, Reiss-Sklan E, Gazit A, Livnah O, Levitzki A. The pp60c-Src inhibitor PP1 is non-competitive against ATP. FEBS Lett. 2003;537:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. Eph/Ephrin signaling in morphogenesis, neural development and plasticity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:580–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B, Drescher U. Src family kinases are involved in EphA receptor-mediated retinal axon guidance. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6248–6257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0985-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda Y, Gemba M. Modulation by cyclic AMP and phorbol myristate acetate of cephaloridine-induced injury in rat renal cortical slices. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;85:54–59. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohof AM, Quillan M, Dan Y, Poo MM. Asymmetric modulation of cytosolic cAMP activity induces growth cone turning. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1253–1261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas TJ, Mirzoeva S, Slomczynska U, Watterson DM. Identification of novel classes of protein kinase inhibitors using combinatorial peptide chemistry based on functional genomics knowledge. J Med Chem. 1999;42:910–919. doi: 10.1021/jm980573a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L. Actin cytoskeleton regulation in neuronal morphogenesis and structural plasticity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:601–635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.031802.150501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann F, Miranda E, Weinl C, Harmer E, Holt CE. B-type Eph receptors and ephrins induce growth cone collapse through distinct intracellular pathways. J Neurobiol. 2003;57:323–336. doi: 10.1002/neu.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Sasaki Y. Staurosporine, a protein kinase C inhibitor interferes with proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;158:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD. Molecular gradients and development of retinotopic maps. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2005;28:327–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Burnett E, Kinch M, Simon E, Wang B. Activation of EphA2 kinase suppresses integrin function and causes focal-adhesion-kinase dephosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:62–69. doi: 10.1038/35000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Strebhardt K, Pasquale EB, Shen TL, Guan JL, Wang B. Inhibition of integrin-mediated cell adhesion but not directional cell migration requires catalytic activity of EphB3 receptor tyrosine kinase. Role of Rho family small GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:923–932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Wei BR, Peehl DM, Li Q, Alexandrou T, Schelling JR, Rhim JS, Sedor JR, Burnett E, Wang B. Activation of EphA receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits the Ras/MAPK pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:527–530. doi: 10.1038/35074604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikule K, Sunpaweravong S, Gatlin JC, Pfenninger KH. Eicosanoid activation of protein kinase C epsilon: involvement in growth cone repellent signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21168–21177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song HJ, Berninger B, Holt CE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM. cAMP-dependent growth cone guidance by netrin-1. Neuron. 1997;19:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Hoshino A, Tsai L, Henley JR, Goshima Y, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM, Hong K. Cyclic AMP/GMP-dependent modulation of Ca2+ channels sets the polarity of nerve growth-cone turning. Nature. 2003;423:990–995. doi: 10.1038/nature01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogita H, Kunimoto S, Kamioka Y, Sawa H, Masuda M, Mochizuki N. EphA4-mediated Rho activation via Vsm-RhoGEF expressed specifically in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:23–31. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000079310.81429.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima T, Takagi H, Suzuma K, Oh H, Suzuma I, Ohashi H, Watanabe D, Suganami E, Murakami T, Kurimoto M, Honda Y, Yoshimura N. EphrinA1 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced intracellular signaling and suppresses retinal neovascularization and blood-retinal barrier breakdown. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:331–339. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabbisetty KB, Yue X, Li C, Himanen JP, Zhou R, Nikolov DB, Hu L. Kinetic analysis of the binding of monomeric and dimeric ephrins to Eph receptors: correlation to function in a growth cone collapse assay. Protein Sci. 2007;16:355–361. doi: 10.1110/ps.062608807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri M, Buricchi F, Taddei ML, Giannoni E, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. EphrinA1 repulsive response is regulated by an EphA2 tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34008–34018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper M, Anderson R, Dwivedy A, Weinl C, van Horck F, Leung KM, Cogill E, Holt C. Signaling mechanisms underlying Slit2-induced collapse of Xenopus retinal growth cones. Neuron. 2006;49:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliakov A, Cotrina M, Wilkinson DG. Diverse roles of eph receptors and ephrins in the regulation of cell migration and tissue assembly. Developmental Cell. 2004;7:465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt RL, Kinch MS. Activation of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase stimulates the MAP/ERK kinase signaling cascade. Oncogene. 2002;21:7690–7699. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg UT, Burgess GM. Staurosporine, K-252 and UCN-01: potent but nonspecific inhibitors of protein kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:218–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin M, Greer PL, Lin MZ, Poucher H, Eberhart J, Schmidt S, Wright TM, Shamah SM, O'Connell S, Cowan CW, Hu L, Goldberg JL, Debant A, Corfas G, Krull CE, Greenberg ME. Eph-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of ephexin1 modulates growth cone collapse. Neuron. 2005;46:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.030. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LC, Matsumura F, Bokoch GM, de Lanerolle P. Inhibition of myosin light chain kinase by p21-activated kinase. Science. 1999;283:2083–2085. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seargeant LE, Stinson RA. Inhibition of human alkaline phosphatases by vanadate. Biochem J. 1979;181:247–250. doi: 10.1042/bj1810247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Goldberg JL, Estrach S, Sahin M, Hu L, Bazalakova M, Neve RL, Corfas G, Debant A, Greenberg ME. EphA receptors regulate growth cone dynamics through the novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor ephexin. Cell. 2001;105:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T, Ihara M, Sakuta H, Takahashi H, Watakabe I, Noda M. Eph receptors are negatively controlled by protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:761–769. doi: 10.1038/nn1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotelersuk V, Siriwan P, Ausavarat S. A novel mutation in EFNB1, probably with a dominant negative effect, underlying craniofrontonasal syndrome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:152–154. doi: 10.1597/05-014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira LA, Smith JL, Tan JL, Spudich JA. MLCK-A, an unconventional myosin light chain kinase from Dictyostelium, is activated by a cGMP-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13000–13005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Ming G, He Z, Lehmann M, McKerracher L, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M. Conversion of neuronal growth cone responses from repulsion to attraction by cyclic nucleotides. Science. 1998;281:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HJ, Ming GL, Poo MM. cAMP-induced switching in turning direction of nerve growth cones. Nature. 1997;388:275–279. doi: 10.1038/40864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Huynh-Do U, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Nck recruitment to Eph receptor, EphB1/ELK, couples ligand activation to c-Jun kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1303–1308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Schoecklmann HO, Schroff AD, Van Etten RL, Daniel TO. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly responses. Genes Dev. 1998;12:667–678. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawska H, Ma PC, Salgia R. The role of ephrins and Eph receptors in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:419–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiercz JM, Kuner R, Behrens J, Offermanns S. Plexin-B1 directly interacts with PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG to regulate RhoA and growth cone morphology. Neuron. 2002;35:51–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma T, Ichida T. Cyclic AMP antagonist Rp-cAMPS inhibits amylase exocytosis from saponin-permeabilized parotid acini. J Biochem. 1991;110:292–294. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki T, Nomoto H, Takahashi I, Kato Y, Morimoto M, Tomita F. Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca++dependent protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang FY, Chiang EP, Shih CJ. Green tea catechin inhibits ephrin-A1-mediated cell migration and angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Elowe S, Nash P, Pawson T. Manipulation of EphB2 regulatory motifs and SH2 binding sites switches MAPK signaling and biological activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:6111–6119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twigg SR, Matsumoto K, Kidd AM, Goriely A, Taylor IB, Fisher RB, Hoogeboom AJ, Mathijssen IM, Lourenco MT, Morton JE, Sweeney E, Wilson LC, Brunner HG, Mulliken JB, Wall SA, Wilkie AO. The origin of EFNB1 mutations in craniofrontonasal syndrome: frequent somatic mosaicism and explanation of the paucity of carrier males. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:999–1010. doi: 10.1086/504440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Murata-Hori M, Tatsuka M, Hosoya H. Rho-kinase contributes to diphosphorylation of myosin II regulatory light chain in nonmuscle cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:5852–5860. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan PC, Twigg SR, Mulliken JB, Cook JA, Quarrell OW, Wilkie AO. Expanding the phenotype of craniofrontonasal syndrome: two unrelated boys with EFNB1 mutations and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:884–887. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihanto MM, Vindis C, Djonov V, Cerretti DP, Huynh-Do U. Caveolin-1 is required for signaling and membrane targeting of EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2299–2309. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindis C, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO, Huynh-Do U. EphB1 recruits c-Src and p52Shc to activate MAPK/ERK and promote chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:661–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S, Barth H, Ciossek T, Aktories K, Mueller BK. Ephrin-A5 induces collapse of growth cones by activating Rho and Rho kinase. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:263–270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Zheng JQ. Directional guidance of nerve growth cones. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieacker P, Wieland I. Clinical and genetic aspects of craniofrontonasal syndrome: towards resolving a genetic paradox. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG. Eph receptors and ephrins: regulators of guidance and assembly. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;196:177–244. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)96005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer-Kleikamp SH, Lackmann M. Eph-modulated cell morphology, adhesion and motility in carcinogenesis. IUBMB Life. 2005;57:421–431. doi: 10.1080/15216540500138337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipf P, Halter RJ. Chemistry and biology of wortmannin. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:2053–2061. doi: 10.1039/b504418a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EV, Kerner JA, Jay DG. Convergent and divergent signaling mechanisms of growth cone collapse by ephrinA5 and slit2. Journal of Neurobiology. 2004;59:66–81. doi: 10.1002/neu.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Li Y, Zhang Z, Cui K, Wang S, Yuan XB, Wu CP, Poo MM, Duan S. Nerve growth cone guidance mediated by G protein-coupled receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nn899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara N, Tachikawa E, Izumi F, Yasugawa S, Yamamoto H, Miyamoto E. Staurosporine: an effective inhibitor for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurochem. 1991;56:294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hughes S. Role of the ephrin and Eph receptor tyrosine kinase families in angiogenesis and development of the cardiovascular system. J Pathol. 2006;208:453–461. doi: 10.1002/path.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JQ, Felder M, Connor JA, Poo MM. Turning of nerve growth cones induced by neurotransmitters. Nature. 1994;368:140–144. doi: 10.1038/368140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. The Eph family receptors and ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:151–181. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.