Abstract

Background

Biliary tract infection is a common cause of bacteraemia and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Few papers describe blood culture isolates, underlying structural abnormalities and clinical outcomes in patients with bacteraemia.

Aims

To determine the proportion of bacteraemias caused by biliary tract infection and to describe patient demographics, underlying structural abnormalities and clinical outcomes in patients with bacteraemia.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Methods

Biliary tract infection that caused bacteraemia was defined as a compatible clinical syndrome and a blood culture isolate consistent with ascending cholangitis. Patients aged 16 years and over were included in the study. From June 2003 to May 2005, demographic and clinical data were collected prospectively on all adult patients with bacteraemia. Radiological and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography findings were collected retrospectively.

Results

In 49 patients, the biliary tract was the site of infection for 39/592 (6.6%) community‐acquired and 19/466 (4.1%) hospital‐acquired episodes of bacteraemia. Three patients had mixed bacteraemias, and four had recurrent bacteraemia. The proportion of patients presenting with a structural abnormality was 34/49 (69%), and, of these structural abnormalities, 18/34 (53%) were pre‐existing or newly diagnosed malignancies. Gram‐negative organisms caused 55/58 (95%) episodes of bacteraemia. The most common Gram‐negative organisms were Escherichia coli (34/55; 62%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (14/55; 26%). Of the E coli isolates, 6/34 (18%) were extended spectrum β‐lactamase producers or multiply drug resistant. Thirty‐day mortality was 7/49 (14%). There was no difference in time taken to administer an effective antibiotic to survivors and non‐survivors (0.86 vs 1.05 days, respectively, p = 0.92). Of the seven who died, four died from septic shock within 48 h of admission caused by “susceptible” Gram‐negative organisms. Two others died from disseminated malignancy.

Conclusions

The proportion of bacteraemias caused by biliary tract infection was 5.5%. The most common infecting organisms were E coli and K pneumoniae. There was a strong association with choledocholithiasis and malignancies, both pre‐existing and newly diagnosed. Death was uncommon but when it occurred was often caused by septic shock within 48 h of presentation.

Keywords: biliary tract infection, cholangitis, bacteraemia, mortality, clinical outcomes

Biliary tract infection is a common cause of bacteraemia and is associated with high morbidity and mortality, particularly in older patients with co‐morbid disease or when there is a delay in diagnosis and treatment.1,2 The most common infecting organisms are Enterobacteriaceae ascending from the gastrointestinal tract.3,4 Although only a third of patients present with Charcot's triad (right upper quadrant pain, fever and jaundice),5 the diagnosis is normally made on the basis of compatible symptoms and signs (eg, abdominal pain and jaundice), raised white cell count and C‐reactive protein, and abnormal liver function tests.6 Imaging of the liver, gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas by ultrasound, CT or MRI usually identifies the presence of an obstruction, the cause of the obstruction, and the level at which the obstruction is occurring.7 Successful management depends on treatment with effective antibiotics and, in most cases, drainage of infected bile.8

Thirty‐day mortality in patients with cholangitis and bacteraemia has been reported to be ∼10%, and independent predictors of death are acute renal failure, septic shock, malignant obstruction, hyperbilirubinaemia and a high Charlson co‐morbidity index >6.9 In patients with bacteraemia, complications such as acute renal failure and septic shock occur more commonly,10 so an improved understanding of causative organisms, susceptibility profiles, and effective treatment and management is likely to result in better clinical outcomes. Despite the seriousness of these infections, no UK paper to date has described blood culture isolates, underlying structural abnormalities, and clinical outcomes in patients with cholangitis that causes bacteraemia. Our primary aims were twofold: (a) to determine the proportion of bacteraemias caused by biliary tract infection; (b) among this group, to determine the proportion presenting with an underlying biliary tract abnormality. We also describe patient demographics, causative organisms, susceptibility profiles, time from positive blood cultures to administration of an effective antibiotic, and 30‐day mortality.

Methods

The study was undertaken at King George Hospital in Essex, part of Barking, Havering and Redbridge Trust, which serves an ethnically diverse population of 300 000. From June 2003 to May 2005, all patients aged 16 years and above with hospital‐acquired and community‐acquired infection were seen by two clinical microbiologists and managed in conjunction with their medical or surgical teams. Patients with biliary tract infection were included in this study if they had symptoms and signs and a positive blood culture compatible with ascending cholangitis. All patients were seen within 72 h of their positive blood culture result. Demographic and clinical data were collected prospectively, and radiological data and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) findings collated retrospectively. Community‐acquired bacteraemia was defined as infection acquired less than 48 h after hospital admission, and bacteraemia occurring after 48 h was defined as hospital‐acquired. Hypotension, at the time of bacteraemia, was defined as a blood pressure less than 90/60 mm Hg. Thirty‐day mortality was defined as time from bacteraemia to death.

Over the study period, hospital doctors were advised to empirically treat suspected community‐acquired biliary tract infection with intravenous cefuroxime (1.5 g three times a day) and intravenous metronidazole (500 mg three times a day). When patients were hypotensive, an additional dose of intravenous gentamicin 400 mg or intravenous amikacin 500 mg twice a day was advised. Patients were referred for imaging (ultrasound, CT or MRI) and drainage of infected bile by ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography if biliary tract obstruction was present. Blood cultures were analysed using an automated system (MBBacT; BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), and Gram‐negative organisms speciated using api20E (BioMerieux). Antibiotic susceptibilities were determined by the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy disc diffusion methods. Extended spectrum β‐lactamase (ESBL) production was screened for by cefpodoxine resistance and confirmed by a “double leaf appearance” between appropriately spaced ceftazidine, co‐amoxiclav and cefotaxime antibiotic discs.11

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted using Stata V9. (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to outline and summarise patients' characteristics. The time from a positive blood culture to administration of an appropriate antibiotic in survivors and non‐survivors was compared by the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results

Bacteraemic episodes

From June 2003 to May 2005, 592 community‐acquired and 466 hospital‐acquired episodes of bacteraemia occurred. The biliary tract was the site of infection for 39/592 (6.6%) community‐acquired and 19/466 (4.1%) hospital‐acquired bacteraemias. Table 1 gives sites of infection that caused bacteraemia. Forty‐nine patients had biliary tract infection resulting in 58 bacteraemic isolates. The median age was 73 years (range 38–94). Similar numbers of men (26/49; 53%) and women (23/49; 47%) were infected. There were three mixed bacteraemias, and four patients had recurrent bacteraemia. Of those with recurrent bacteraemia, two patients had blocked biliary stents previously inserted for carcinoma of the head of the pancreas and cholangiocarcinoma. Two others had recurrent episodes of ascending cholangitis related to choledocholithiasis before planned cholecystectomy. Two developed infection at distant sites, one mitral valve (native) and the other lumbar spine.

Table 1 Sites of infection causing bacteraemia (June 2003–May 2005).

| Community‐acquired (n = 592) | Hospital‐acquired (n = 466) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gram‐negative organisms | 311 (52.5) | 233 (50.0) |

| Urinary tract infection | 178/311 (57.2) | 94/233 (40.3) |

| Biliary tract infection | 39/311 (12.5) | 19/233 (8.2) |

| Intravascular catheters | 3/311 (1.0) | 30/233 (12.9) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 5/311 (1.6) | 4/233 (1.7) |

| Other sites/not defined | 86/311 (27.7) | 86/233 (36.9) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Structural abnormalities

Almost three‐quarters of patients presented with a structural abnormality, revealed by imaging, (34/49; 69%). Of these patients with structural abnormalities, 18/34 (53%) had malignancies that were pancreatic carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma or liver metastases. Eight cases of cancer were newly diagnosed. Of the 10 cancer cases already known, biliary stents were already “in situ” at the time of bacteraemia in four. Table 2 summarises the structural abnormalities and types of cancer.

Table 2 Structural abnormalities predisposing to biliary tract infection and bacteraemia.

| Total | Community‐ acquired | Hospital‐ acquired | Stents in situ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 18/49 (37%) | – | – | – |

| Pancreatic | 9/49 (18%) | – | – | – |

| Known | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Newly diagnosed | 4 | 4 | – | – |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 7/49 (14%) | – | – | – |

| Known | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Newly diagnosed | 4 | 2 | 2 | – |

| Liver metastases (not related to pancreatic or cholangiocarcinoma) | 2/49 (4%) | 2 | – | – |

| Non‐cancer | 16/49 (33%) | – | – | – |

| Choledocholithiasis | 14/49 (29%) | – | – | – |

| Known | 6 | 6 | 1 | – |

| Newly diagnosed | 8 | 7 | – | – |

| Other | 2/49 (4%) | – | – | – |

| Benign stricture | 2 | 2 | – | – |

| Unknown | 15/49 (31%) | 10 | 5 | – |

Microbiological aetiology

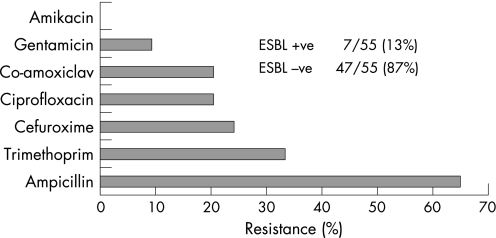

Gram‐negative organisms caused most episodes of bacteraemia (55/58; 95%). Only three bacteraemic episodes were caused by Gram‐positive organisms, one by Streptococcus bovis, one by Enterococcus faecalis, and one by methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The most common Gram‐negative organisms were Escherichia coli (34/55; 62%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (14/55; 26%). Of the E coli isolates, 6/34 (18%) were ESBL producers or were multiply drug resistant. None of the K pneumoniae isolates were ESBL producers. The other Gram‐negative organisms were Klebsiella oxytoca (3/55; 5%), Proteus vulgaris (2/55; 4%), Pseudomonads (not‐speciated) (2/55; 4%), Enterobacter cloacae (1/55; 2%), Serratia marcescens (1/55; 2%) and Citrobacter (not‐speciated) (1/55; 2%). The proportion of Gram‐negative organisms resistant to cefuroxime and gentamicin were 13/55 (24%) and 5/55 (9%) respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the susceptibility profiles of the Gram‐negative organisms.

Figure 1 Susceptibility profiles of 55 Gram‐negative organisms causing biliary tract infection and bacteraemia. ESBL, extended spectrum β‐lactamase.

Clinical presentation

Table 3 summarises symptoms and signs at presentation. The most common were pain, weight loss, fever and jaundice. C‐reactive protein was more often raised than white cell count, and alanine aminotransferase activity was more often raised than alkaline phosphatase activity. Eight patients out of 49 (16%) were hypotensive at presentation, and, in all but two cases, infections were diagnosed clinically before the availability of blood culture results. Drainage of bile was attempted in 23/49 (47%) cases, 20 by ERCP, two by percutaneous transhepatic drainage, and one at surgery. Three attempted ERCPs were unsuccessful, and one caused a further episode of biliary tract infection and bacteraemia.

Table 3 Haematological and biochemical abnormalities associated with biliary tract infection (n = 49).

| Symptom | |

| Abdominal pain | 25 (51) |

| Weight loss | 8 (16) |

| Signs | |

| Fever (>37.5°C) | 31 (63) |

| Jaundice | 27 (55) |

| Laboratory abnormalities | |

| WCC >11.0×109/l | 26 (53) |

| CRP >5 mg/l* | 31 (73) |

| Bilirubin >17 μmol/l | 29 (59) |

| ALT >40 IU/ml | 34 (69) |

| ALP >128 IU/l | 27 (55) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

*CRP not determined in seven patients.

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; WCC, white cell count.

Clinical outcomes

Thirty‐day mortality was 7/49 (14%). The age range of the seven who died was 15–89 years (mean age 67.7). Four were male and three were female. Four died from septic shock within 48 h of bacteraemia. One patient who died had both an ESBL‐producing E coli bacteraemia (resulting in a delay in receiving appropriate antibiotics) and impacted gallstones in the common bile duct that could not be extracted at ERCP. Two patients, whose main disease was disseminated cancer with liver metastases, were treated palliatively around the time of death. In those who survived, the average delay in administering an effective antibiotic was not significantly different from that for non‐survivors (0.86 vs 1.05 days, respectively, p = 0.92).

Discussion

We found that 5.5% of bacteraemic episodes were due to biliary tract infections. The most common infecting organisms were E coli and K pneumoniae, and there was a strong association with choledocholithiasis and malignancies. Almost half the malignancies were newly diagnosed and were carcinoma of the head of the pancreas, cholangiocarcinoma or liver metastases. The main cause of death was septic shock caused by “sensitive” Gram‐negative organisms or disseminated cancer in patients who were treated palliatively.

Our study showed a strong association with underlying abnormalities, in particular choledocholithiasis and malignancies that few other studies of patients with bacteraemia have detailed. Almost half the malignancies where newly diagnosed, and this demonstrates the importance of appropriate imaging in determining the nature of an underlying abnormality. We did not find the co‐existence of choledocholithiasis and malignancy that others have reported.12 The relative importance of host and bacterial virulence factors in ascending cholangitis was not addressed, although others have found that biliary tract obstruction was the most important factor for E coli bacteraemia, not bacterial virulence.13

Learning points

Biliary tract infections that cause bacteraemia often occur in patients with an underlying structural abnormality, normally choledocholithiasis or malignancy.

At the time of bacteraemia, the most common malignancies are carcinoma of the head of the pancreas, cholangiocarcinoma or liver metastases.

After bacteraemia, appropriate imaging by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), CT or MRI of the abdomen can be useful for diagnosis of a new malignancy.

Empirical treatment with a cephalosporin targeting Enterobacteriaceae should be given and, when the patient is hypotensive, an aminoglycoside active against ESBL‐producing coliforms should be used as adjuvant treatment.

Biliary drainage, either by ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, is often required for successful clinical outcome.

The strength of this study was the analysis of over 1000 patient episodes of community‐acquired and hospital‐acquired bacteraemia, reliably allowing us to determine the proportion of bacteraemic episodes caused by biliary tract infection. A previous study of 875 bacteraemias reported 9.5% of episodes secondary to “acute cholangitis”,14 a proportion similar to ours. We are aware of only two other studies with larger numbers of bacteraemic patients with cholangitis. In a study of 78 patients,10 a single organism, most commonly E coli or K pneumoniae, was isolated from blood in 87% of cases, findings similar to ours. The authors, however, did not detail the presence of underlying structural abnormalities. In an Israeli study15 of 70 patients with 76 episodes of bacteraemia, 13/70 (19%) had an underlying malignancy compared with our finding of 18/49 (37%). Patients were classified into three groups: those with cholelithiasis without previous surgery; those with cholangitis after remote or recent cholecystectomy; those with pancreatic or biliary tract tumours. Dual pathology was not identified. It is unclear why fewer malignancies were identified in the Israeli study even though a similar proportion were new diagnoses following an episode of bacteraemia: 6/13 (46%) vs 8/18 (44%).

Our study had some limitations. We did not determine the prevalence of bacteraemia in acute cholecystitis, previously quoted at 7.65%.10 Bile obtained at ERCP was not routinely cultured. Although of interest, we do not believe that this was required for a correct diagnosis of ascending cholangitis. Some information from case notes was collected retrospectively, although most data were collected prospectively. Finally, although our results are applicable to other UK district general hospitals, they may be less generalisable to specialist units where liver transplant recipients are managed or where biliary drainage procedures are more common.

Symptoms, signs and laboratory tests enabled most clinicians to correctly diagnose the site of infection and start appropriate antibiotic treatment without prompting from a clinical microbiologist after blood culture results. This is in contrast with other conditions such as urinary tract infections.16 Therefore, the most important messages conveyed to the clinicians were to emphasise the association of underlying structural abnormalities, particularly choledocholithiasis or malignancy, and the importance of obtaining biliary drainage in patients with obstruction.

Enterobacteriaceae were the most common organisms isolated from the blood, in particular E coli and K pneumoniae, and, as in another study,14 we found a small number of polymicrobial infections. The isolation from blood of both E coli and K pneumoniae was similar to two previous studies,10,16 although detection of ESBL‐producing organisms that had multiple drug resistance was new and has only been recently described.17 In another study, enterococci were more often isolated from blood and bile in patients with acute cholecystitis.18 On the basis of these findings, many doctors favour the use of co‐amoxiclav or piperacillin/tazobactam as empirical treatment for biliary tract infection. E faecalis is, however, a “low‐virulence” organism, and co‐amoxiclav and piperacillin/tazobactam are not reliable treatments for infections caused by ESBL‐producing Enterobacteriaceae.19,20 Our microbiological data suggest that cefuroxime (intravenous) and metronidazole (intravenous) are optimal first‐line treatments, although, in hypotensive patients, an aminoglycoside active against ESBL‐producing coliforms should be used as adjuvant therapy.

In addition to antibiotics, successful management of patients often requires biliary drainage, either transhepatically or by sphincterotomy and biliary stenting at ERCP. Many patients required ERCP for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons. Most of these procedures were successful, comparing favourably with audits performed at other centres.21,22 We did not audit the proportion of patients with choledocholithiasis listed for elective cholecystectomy as is appropriate for patients who have suffered a life‐threatening complication.

Doctors and clinical microbiologists should be aware that bacteraemia caused by biliary tract infection often occurs in patients with an underlying biliary tract abnormality. Appropriate imaging can diagnose a new underlying malignancy, and we reported a significant minority of patients who presented with malignancy‐associated cholangitis in the absence of choledocholithiasis. Death following bacteraemia caused by biliary tract infection is uncommon. Treatment should target Enterobacteriaceae with a cephalosporin, and, when the patient is hypotensive, an aminoglycoside effective against ESBL‐producing E coli or K pneumoniae should also be administered. Biliary drainage, by ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, is often required for a successful clinical outcome.

Abbreviations

ERCP - endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ESBL - extended spectrum β‐lactamase

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Bornman P C, van Beljon J I, Krige J E J. Management of cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surg 200310406–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anon What if it's acute cholangitis? Drugs Therapy Bulletin 2005438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claesson B E, Holmlud D E, Matzsch T W. Microflora of the gallbladder related to duration of acute cholecystitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1986162531–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada K, Noro T, Inamatsu T.et al Bacteriology of acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis of the aged. J Clin Microbiol 198114522–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafif A, Gutman M, Kaplan O.et al The management of acute cholecystitis in elderly patients. Am Surg 199157648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusoff I F, Barkun J S, Barkun A N. Diagnosis and management of cholecystitis and cholangitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003321145–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park M S, YU JS, Kim YH, et al Acute cholecystitis: comparison of MR cholangiography and US. Radiology 1998209781–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson J E, Jr, Tompkin R K, Longmire W P., Jr Factors in management of acute cholangitis. Ann Surg 1982195137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee C C, Chang I J, Lai Y C.et al Epidemiology and prognostic determinants of patients with bacteraemic cholecystitis or cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007102563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo C H, Changchien C S, Chen J J.et al Septic acute cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 199530272–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Agency Laboratory detection and reporting of bacteria with extended spectrum beta‐lactamases. National Standard Method QSOP 51 Issue 2. London: Health Protection Agency 2004

- 12.Ashton C E, Mc Nabb W R, Wilkinson M L.et al Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in elderly patients. Age Ageing 199827683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M C, Tseng C C, Chen C Y.et al The role of bacterial virulence and host factors in patients with E. coli bacteraemia who have acute cholangitis or UTIs. Clin Infect Dis 2002351161–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ispahani P, Pearson N J, Greenwood D. An analysis of community and hospital‐acquired bacteraemia in a large teaching hospital in the UK. Q J Med 198763427–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegman‐Igra Y, Schwartz D, Kanfarti N.et al Septicaemia from biliary tract infection. Arch Surg 1988123366–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eykyn S J. Urinary tract infections in the elderly. Br J Urol 19988279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitout J D, Nordam P, Lampland K B. Emergence of enterobacteriaceae producing extended‐spectrum beta‐lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother 20055652–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rerknimitr R, Fogel E L, Kalayci C.et al Microbiology of bile in patients with cholangitis or cholestasis with and without plastic biliary endoprosthesis. Gastrointest Endosc 200256885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babini G S, Yuan M, Hall L M.et al Variable susceptibility to piperacillin/tazobactam amongst Klebsiella spp. with extended‐spectrum beta‐lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 200351605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagani L, Migliavacca R, Luzzaro F.et al Comparative activity of piperacillin/tazobactam against clinical isolates of extended‐spectrum beta‐lactamase‐producing Enterobacteriaceae. Chemotherapy 199844377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandolfi L, Rossi A, Vaira D.et al Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the elderly. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 198649602–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacMahon N, Walsh T N, Brennan P.et al Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the elderly: a single unit audit. Geronotology 19933928–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]