Abstract

Kindler syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by skin atrophy and blistering. It results from loss-of-function mutations in the FERMT1 gene encoding the focal adhesion protein, fermitin family homolog-1. How and why deficiency of fermitin family homolog-1 results in skin atrophy and blistering are unclear. In this study, we investigated the epidermal basement membrane and keratinocyte biology abnormalities in Kindler syndrome. We identified altered distribution of several basement membrane proteins, including types IV, VII, and XVII collagens and laminin-332 in Kindler syndrome skin. In addition, reduced immunolabeling intensity of epidermal cell markers such as β1 and α6 integrins and cytokeratin 15 was noted. At the cellular level, there was loss of β4 integrin immunolocalization and random distribution of laminin-332 in Kindler syndrome keratinocytes. Of note, active β1 integrin was reduced but overexpression of fermitin family homolog-1 restored integrin activation and partially rescued the Kindler syndrome cellular phenotype. This study provides evidence that fermitin family homolog-1 is implicated in integrin activation and demonstrates that lack of this protein leads to pathological changes beyond focal adhesions, with disruption of several hemidesmosomal components and reduced expression of keratinocyte stem cell markers. These findings collectively provide novel data on the role of fermitin family homolog-1 in skin and further insight into the pathophysiology of Kindler syndrome.

Kindler syndrome (KS; OMIM 173650) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by trauma-induced skin blistering, skin atrophy, and poikiloderma.1 KS results from pathogenic mutations in the FERMT1 (formerly KIND1 or C20orf42) gene that encodes fermitin family homolog-1 (FFH1) (formerly kindlin-1 or kindlerin), an actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion-associated molecule.2,3 FFH1 is mainly expressed in basal keratinocytes.3,4,5,6 In KS, however, there is often a complete absence of FFH1 protein expression, although some variability may occur.6 Thus far, 37 different loss-of-function FERMT1 mutations have been identified.7,8,9 The mechanism by which these pathogenic FERMT1 mutations result in skin atrophy and blistering, however, remains unclear. Indeed, insight from studies on KS skin and FFH1 has been limited. Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies on KS skin have revealed a disrupted and reduplicated cutaneous basement membrane,4,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and silencing of FFH1 in HaCaT cells results in reduced cell adhesion, proliferation, and spreading.17 In addition, cultured KS keratinocytes display decreased cell adhesion and proliferation and exhibit multiple cell polarities and undirected migration.5 Moreover, FFH1 is able to bind to the cytoplasmic tails of β1 and β3 integrins,17,18 colocalizes with vinculin and paxillin at focal adhesions in keratinocytes,17 and associates biochemically with FFH2 and filamin binding LIM protein.6 Overall, these studies suggest a critical role for FFH1 in cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions but do not fully explain the clinicopathological abnormalities present in KS.

Cell-ECM interactions are principally mediated by integrins through integrin activation and cytoskeletal organization.19,20 An important step in integrin activation is the binding of the FERM (four point one protein, ezrin, radixin, and moesin) domain of talin to the cytoplasmic tail of integrin.21,22,23,24,25,26,27 It is being increasingly recognized that other proteins may also regulate integrin activation. FFH2 (expressed predominantly in the heart) and FFH3 (expressed mainly in hematopoietic tissue) recently have been identified as essential regulators of integrin activation with deficiencies in these two focal adhesion proteins leading to cardiac malformation and platelet dysfunction, respectively.28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 FFH1, 2, and 3 form part of a protein family that shares a high degree of sequence homology as well as a bipartite FERM domain interrupted by a pleckstrin homology domain.3,37 Nevertheless, it remains to be determined whether FFH1 is involved in integrin activation in keratinocytes. In the current study, we have identified new pathological abnormalities involving epidermal stem cell markers, hemidesmosomal-associated proteins and integrin activation in KS. Our study also highlights a crucial role of FFH1 in integrin biology because induction of its overexpression in KS keratinocytes is able to restore integrin activation and partially rescue the cellular phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies (Abs) were used: anti-type VII collagen Ab (clone LH7.2, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-type IV collagen Ab (clone col-94, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-laminin-332 Ab (AbCam, Cambridge, UK), anti- cytokeratin 15 Ab (gift from Professor Irene Leigh, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland), anti-cytokeratin 5 Ab (Chemicon International, Southampton, UK), anti-cytokeratin 14 Ab (AbCam), anti-loricrin Ab (AbCam), anti-involucrin Ab (Novocastra, Newcastle on Tyne, UK), anti-β1 integrin Ab (clone 4B7R, AbCam), anti-β4 integrin Ab (clone 450–9D, AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), anti-α6 integrin Ab (clone GOH3, AbCam), anti-FFH1 Ab (gift from Dr. Mary Beckerle, Salt Lake City, UT), and anti-Ki-67 antibody (Abcam). The following secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR): Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse Ab, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit Ab, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rat Ab, and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit Ab. Actin fibers were revealed by rhodamine phalloidin (Cytoskeleton/Universal Biologicals Ltd., Cambridge, UK) or by Oregon Green 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen).

Skin Biopsies

Skin biopsy samples were taken for histological assessment, tissue culture, and nucleic acid extraction after written informed consent was obtained from subjects with KS and normal volunteers in accordance with approval of the ethics committee of the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The individuals with KS harbored the following loss-of-function mutations in the FERMT1 gene: p.Glu516X/p.Glu516X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X, p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Glu304X/p.Leu302X, and p.Glu304X/ c.1909delA.

Assessment of Epidermal Thickness

To formally define whether the epidermis in KS skin is thinner than normal, we compared epidermal thickness in skin sections obtained from four patients with KS harboring loss-of-function FERMT1 mutations p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X, c.676insC/c.676insC, and p.Glu404X/c.1161delA, with that in skin sections from age-, site-, and gender-matched control subjects by H&E staining as described previously.5 Epidermal thickness was perpendicularly measured from the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) to the granular layer using NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon Instruments Europe B.V., Amstelveen, The Netherlands). The measurements (n = 8) were performed in five skin sections (containing intact epidermis and dermis) at various locations for each sample, which therefore minimizes the possibility of random selection. Student’s t-test was used to compare epidermal thickness averages for both normal human and KS skin.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed on three KS skin samples harboring FERMT1 mutations p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X, and c.676insC/c.676insC, as described previously.38 Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined in a JEOL 100CX transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy Labeling

To evaluate the structural abnormalities present in KS skin, we performed immunofluorescence microscopy labeling for a range of basement membrane proteins, namely type IV, VII, and XVII collagens, α6, β1, and β4 integrins, and laminin-332, in seven patients with KS harboring loss-of-function FERMT1 mutations p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X, p.Glu516Ter/p.Glu516Ter, c.676insC/c.676insC, p.Glu168X/p.Glu168X (two patients), and p.Glu404X/c.1161delA as described previously.6

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling Assay

A terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay was performed on 5-μm-thick frozen skin sections obtained from four patients with KS harboring the following FERMT1 mutations: p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X, p.Glu516X/p.Glu516X, and c.676insC/c.676insC. A Fluorescein in Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Burgess Hill, UK) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Skin biopsies were stored in RNAlater (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) before processing. RNA was isolated from each biopsy using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA isolation from cells was performed using Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 1 μg of total RNA using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The mRNA expression of genes of interest was validated using cDNA synthesized from skin samples from four patients with KS (harboring the following loss-of-function mutations in FERMT1: p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X [two patients], and p.Glu404X/p.Leu302X) and four age-, site-, and gender-matched control subjects. The following TaqMan gene expression assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Warrington, UK): ITGB1 (assay identification number Hs01127543_m1), ITGB4 (Hs00173995_m1), ITGA6 (Hs01041011_m1), KRT15 (Hs00267035_m1); GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1), and B2M (Hs99999907_m1). The PCR reaction was performed in an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Each PCR reaction consisted of 0.5 μl of cDNA, 10.75 μl of H2O, 12.5 μl of TaqMan MasterMix (Applied Biosystems), and 1.25 μl of TaqMan gene expression assay, making up a total volume of 25 μl. Forty cycles of PCR amplification were used.

Primary Keratinocyte Culture

Skin biopsies from three patients with KS with FERMT1 mutations p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X, p.Trp516X/p.Trp516X, and c.676insC/c.676insC were incubated overnight at 4°C with Dispase I (dilution 34 U in 20 ml of PBS) (Roche Applied Science). Keratinocyte isolation was then performed as described previously.6

Immortalization of Primary Human Keratinocytes

Keratinocytes from a 29-year-old man with KS, harboring the compound heterozygous FERMT1 mutations p.Glu304X/p.Leu302X, and from an age- and gender-matched control subject were immortalized with the human papilloma virus (HPV16 E6 and E7), as described previously.39 All experiments were performed between 15 to 25 passages after immortalization.

Keratinocyte Transfection

Immortalized normal human keratinocytes (NHKs) and KS keratinocytes were transfected with the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-FERMT1 expression plasmid (kindly donated by Professor R. Fässler, Department of Molecular Medicine, Max Planck Institute, Martinsried, Germany) with the GeneJammer Transfection Reagent (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). In brief, 1 × 106 keratinocytes were grown in EpiLife (Invitrogen) and allowed to reach between 50 and 80% confluence before the transfection mixture consisting of 1 μg of plasmid and 3 μl of GeneJammer was added.

Flow Cytometry

A minimum of 105 keratinocytes were washed twice in buffer consisting of PBS, 3% fetal bovine serum, and 0.3% bovine serum albumin. Primary antibody incubation was performed on live cells for 15 minutes. Secondary antibody incubation was also performed for 15 minutes. The cells were then fixed in 1% formaldehyde solution. A parallel experiment using isotype controls was conducted. Flow cytometry acquisition was used to analyze 104 independent events using the BD fluorescence-activated cell sorting Aria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK).

Immunocytochemistry

For immunofluorescence, the fixed cells (fixation was achieved using 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature) were blocked with 10% swine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS followed by incubation with primary antibody. Secondary antibody incubation was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. The fixed coverslips were analyzed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Imaging confocal microscopy system (Carl Zeiss Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Colony-Forming Assay

A total of 600 NHKs and KS keratinocytes were separately plated and kept in culture for 14 days. Culture medium was changed every 3 days. Phase-contrast microscopy photographs were taken at day 14 after seeding.

Adhesion Assay

Adhesion assays were performed in a 96-well plate: 1 × 104 keratinocytes were allowed to adhere for 30 minutes, after which nonadherent cells were gently washed with PBS. The adherent cells were then incubated overnight with a substrate buffer consisting of 7.5 mol/L P nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 M sodium citrate at pH 5, and 0.5% Triton X-100 at 37°C. Stop buffer (50 mmol/L glycine at pH 10.4, and 5 mmol/L EDTA) was then added, and optical density at 405 nmol/L was recorded. The adhesion assays were performed in triplicate.

Kymography and Circularity Index Measurements

Phase-contrast imaging of cells was performed on a Zeiss Axio 100 microscope equipped with a Sensicam charge-coupled device camera (PCO Cooke, Romulus, MI), motorized stage (Ludl, Hawthorne, NY), excitation/emission filters (Chroma Technology Corp, Rockingham, VT), and filter wheels (Ludl). Images were acquired using a ×40 oil objective for single-cell analysis. Kymography and circularity analysis of protrusion was performed using the ImageJ plug-in (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Six kymograph lines were quantified from 12 cells over three independent experiments.

Results

Clinical Features of Kindler Syndrome Subjects

Affected individuals with KS experience acral blistering and poikiloderma (clinical combination of hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, telangiectasia, and atrophy) involving photo-exposed sites. Gingivitis and dental plaque are also prominent features. There is generalized xerosis and marked skin atrophy affecting in particular the dorsa of the hands (Figure 1A) and feet. Some affected subjects also have urethral and esophageal stenoses that can require surgical correction. The patients’ demographics and FERMT1 mutations, previously described elsewhere,3,4,7,40,41 are summarized in Table 1.

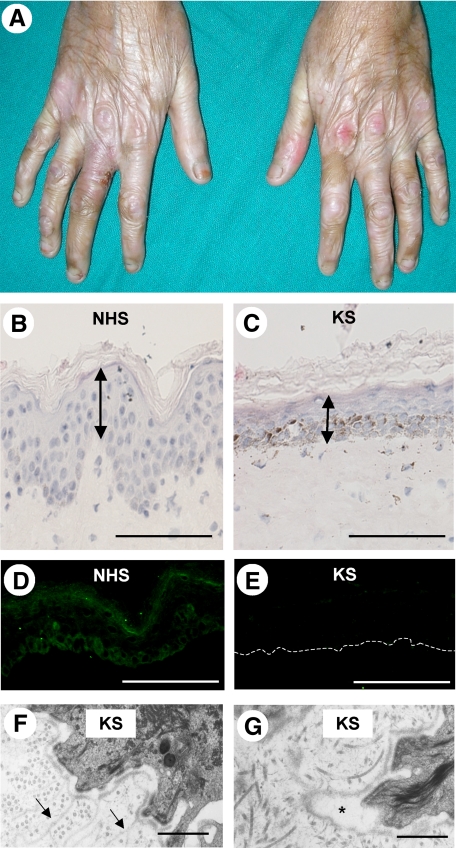

Figure 1.

Clinicopathological features of KS. A: Severe skin atrophy is present on the dorsal aspects of the hands. B: H&E staining reveals normal invagination of the rete ridges into the dermis in normal human skin (NHS). Acanthosis and hyperkeratosis are not observed. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: H&E staining shows loss of the rete ridges in KS skin associated with a significant reduction in mean epidermal thickness. Scale bar = 50 μm. D: In NHS, FFH1 is predominantly expressed in the basal keratinocyte layer close to the DEJ. E: In KS skin harboring the homozygous FERMT1 mutation, p.Glu516X/p.Glu516X, there is a marked reduction in FFH1 immunolabeling. The dashed line represents the DEJ. Scale bar = 50 μm. F: Transmission electron microscopy shows reduplication of the lamina densa in KS skin (arrows); G: Transmission electron microscopy shows focal widening of the lamina lucida in KS skin (asterisk). Scale bar = 2 μm.

Table 1.

Summary of FERMT1 Mutations and Patients’ Demographics

| Cases | FERMT1 mutations | Ethnicity | Age at which skin biopsy was done (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.811C>T/c.811C>T (p.Arg271X/p.Arg271X) | Omani | 8 |

| 2 | c.1847G>A/c.1847G>A (p.Trp616X/p.Trp616X) | Omani | 13 |

| 3 | c.676insC/c.676insC (p.Gln226fsX17/p.Gln226fsX17) | Brazilian | 37 |

| 4 | c.910G>T/c.1161delA (p.Glu304X/p.K387fsX15) | US Caucasian | 63 |

| 5 | c.502G>T/c.502G>T (p.Glu168X/p.Glu168X) | Indian | 15 |

| 6 | c.502G>T/c.502G>T (p.Glu168X/p.Glu168X) | Indian | 12 |

| 7 | c.910G>T/c.905T>A (p.Glu304X/p.Leu302X) | UK Caucasian | 29 |

| 8 | c.1548G>T/c.1548G>T (p.Glu516X/p.Glu516X) | Indian | 3 |

Kindler Syndrome Skin Is Thin, Lacks FFH1, and Shows Disrupted Epidermal Basement Membrane

KS skin showed a marked reduction in epidermal thickness associated with loss of the rete ridges. There was hyperkeratosis but no parakeratosis. Epidermal thickness, measured from the granular layer to the DEJ, was significantly thinner in KS skin compared with that of normal control skin (mean thickness 32.8 ± 4.5 [SD] μm versus 38.6 ± 9.6 μm; P < 0.05) (Figure 1, B and C). Marked pigmentary incontinence was noted in skin biopsies from subjects with KS of Indian ancestry (Fitzpatrick type V skin). Inflammatory cells were not observed. FFH1 immunolabeling showed membranous staining predominantly in the basal keratinocytes close to and at the DEJ in normal control skin (Figure 1D). In contrast, in the KS skin samples studied, a markedly reduced/barely detectable expression of FFH1 within the basal keratinocyte layer was noted (Figure 1E). Ultrastructurally, transmission electron microscopy showed reduplication of the lamina densa (Figure 1F) associated with focal widening of the lamina lucida (Figure 1G). In addition, in areas in which the lamina lucida was widened, the hemidesmosomes seemed to be hypoplastic and reduced in number.

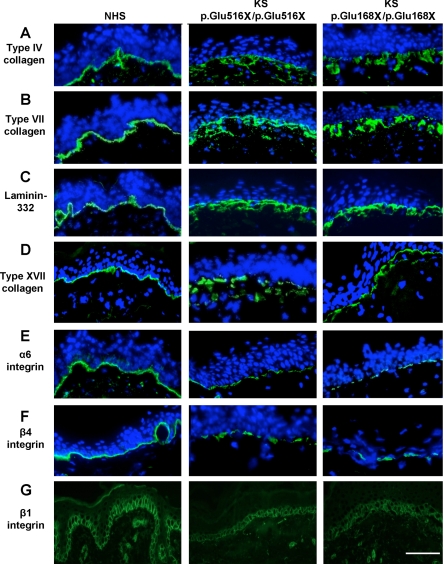

Immunofluorescence Microscopy Assessment of Kindler Syndrome Skin Reveals Abnormal Basement Membrane and Reduced Labeling for α6, β1, and β4 Integrins

In KS skin, there was broad and fragmented staining at the DEJ for type IV collagen (Figure 2A), type VII collagen (Figure 2B), laminin-332 (Figure 2C), and type XVII collagen (Figure 2D) compared with that of normal control skin. Nevertheless, the intensity of immunolabeling for these particular proteins was similar to that for control skin. In contrast, immunostaining for the hemidesmosome-associated α6 and β4 integrins showed fragmented linear and reduced intensity staining at the DEJ in KS skin (Figure 2, E and F). Immunolabeling for β1 integrin revealed reduced intensity membranous staining in the basal keratinocyte layer (Figure 2G). There was no change in either the pattern or intensity of labeling for cytokeratins 5/14, 6/16, and 1/10 or for markers of terminal differentiation (loricrin and involucrin) when normal control and KS skin were compared (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy labeling of normal human skin (NHS) and KS skin. A: In NHS, type IV collagen labeling is present at the DEJ. In contrast, in KS skin, there is broad reticular labeling at the DEJ. B: In NHS, bright and uninterrupted labeling of type VII collagen is present at the DEJ. In KS skin, there is a fragmented and broad staining pattern at the DEJ. C: Bright staining for laminin 332 is present at the DEJ in NHS. In contrast, in KS skin, there is discontinuous and broad reticulated labeling at the DEJ. D: In NHS, bright type XVII collagen staining is present at the DEJ, whereas in KS skin, broad and reticulated labeling is observed. E: Bright α6 integrin staining is present at the DEJ in NHS. In KS skin, there is marked fragmentation as well as a reduction in labeling intensity at the DEJ. F: In NHS, there is bright staining for β4 integrin at the DEJ. In KS skin, however, there is a reduction in labeling intensity associated with fragmentation at the DEJ. G: In NHS, membranous staining in the basal keratinocyte layer is seen for β1 integrin, whereas reduced labeling intensity is observed in KS skin. Nuclei are highlighted by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm.

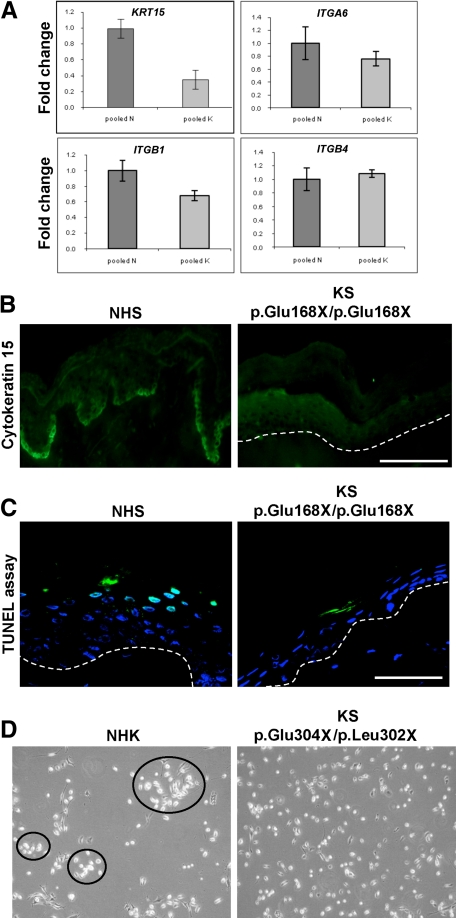

Kindler Syndrome Skin Shows Reduced Cytokeratin 15 Gene and Protein Expression

The reduction in the putative epidermal stem cell markers, α6 and β1 integrins, prompted us to investigate other stem cell markers. Real-time PCR showed a greater than twofold down-regulation of KRT15 mRNA expression in four patients with KS compared with four normal control subjects (Figure 3A). Furthermore, markedly reduced labeling for cytokeratin 15 in KS skin was observed (Figure 3B). Real-time PCR also showed a significant difference in the mRNA expression of β1 integrin but not α6 and β4 integrins (Figure 3A). Immunolabeling for the proliferation marker Ki-67 in KS skin revealed an almost complete absence of fluorescence compared with normal control skin (data not shown). To determine whether apoptosis could be a contributing factor in the development of the atrophic skin phenotype, a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay was performed on KS skin sections, but no difference in apoptotic activity was observed between normal control skin and KS skin (Figure 3C). Finally, to examine the consequences of reduced stem cell markers, a colony-forming assay comparing KS keratinocytes with NHKs was performed. In contrast to NHKs, which formed small colonies even at low density, KS keratinocytes did not segregate with each other (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

A: Real-time PCR shows a >2-fold reduction in KRT15 mRNA expression in KS skin (labeled as K) compared with normal control skin (labeled as N). A significant reduction in ITGB1 mRNA expression was noted (P < 0.05), but there was no difference in either ITGA6 or ITGB4 mRNA expression. B: In normal human skin (NHS), cytokeratin 15 labeling is present predominantly at the tips of the rete ridges. In KS skin, however, there is a marked reduction in basal staining for cytokeratin 15. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling staining in both NHS and KS skin shows no difference in apoptosis at the basal keratinocyte layer. Some apoptotic cells (green) are present in the upper epidermis. The dashed line represents the DEJ. Scale bar = 50 μm. D: NHKs are able to form colonies even at low density whereas KS keratinocytes do not aggregate like NHKs.

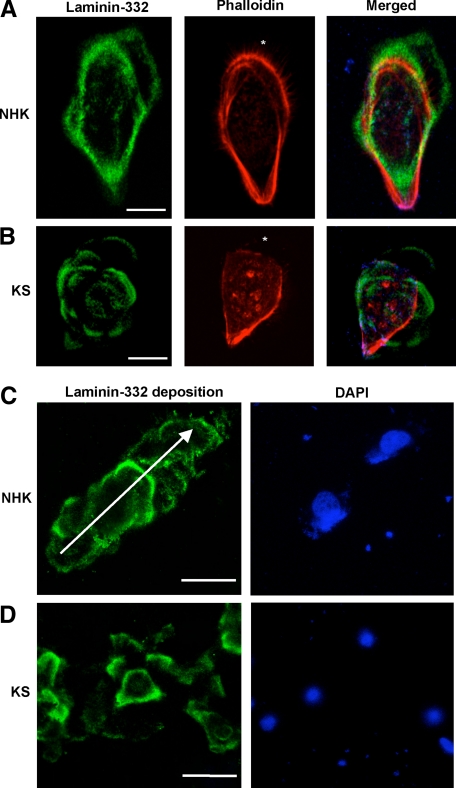

Kindler Syndrome Keratinocytes Secrete a Disorganized Basement Membrane

To examine the structural basement membrane abnormalities in KS skin, we investigated the secretion of the major basement membrane component, laminin-332, from immortalized NHKs and KS keratinocytes (harboring the compound heterozygous FERMT1 mutations, p.Glu304X/p.Leu302X). In NHKs, laminin-332 deposition was noted at the leading edge of the cell (Figure 4A). In contrast, multidirectional extracellular laminin-332 deposition was observed in KS keratinocytes, resembling a “flower and petal” distribution (Figure 4B). To investigate matrix deposition dynamics, we analyzed laminin-332 distribution after separately seeding NHKs and KS keratinocytes in a time-course experiment (2, 4, and 12 hours); data at 12 hours after seeding are illustrated (Figure 4C). At 2 hours after seeding, there was prominent deposition of laminin-332 in NHKs. Beyond 4 hours, there was deposition of laminin-332 in linear tracks adjacent to the NHKs (Figure 4C). For KS keratinocytes there was reduced deposition of laminin-332 at 2 hours after seeding. Beyond 4 hours, the pattern of laminin-332 deposition consisted of incomplete circular arrays (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy studies of laminin-332 deposition from NHKs and KS keratinocytes. A: In NHKs, there is deposition of laminin-332 (green) outside the cell in the direction of the migrating cell. B: In contrast, in KS keratinocytes, the deposition of laminin-332 (green) is haphazard, resembling a “flower and petal” distribution. The actin cytoskeleton is revealed by phalloidin staining (red). The asterisk denotes the leading edge of the cell. C: Laminin-332 deposition 12 hours after seeding. For NHKs, there is laminin-332 (green) deposition in a linear fashion. The arrow shows the direction of migration. D: In contrast, the distribution of laminin-332 (green) is haphazard, reflecting the disorganized migratory property of KS keratinocytes. Nuclei are revealed by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm.

Kindler Syndrome Keratinocytes Display Reduced Adhesion to Several ECM Substrates

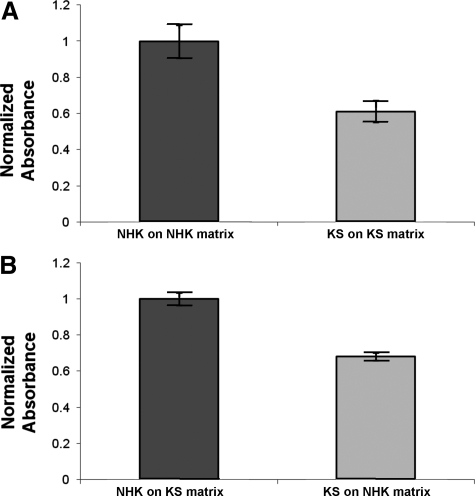

Adhesion of KS keratinocytes was compared with that of NHKs to a variety of ECM substrates including laminin-332, collagen, and fibronectin. KS keratinocytes demonstrated significantly reduced adhesion to plastic (uncoated wells) as well as to their own secreted matrix compared with that of NHKs (Figure 5A). However, KS keratinocyte adhesion was not increased when the cells were plated onto NHK-secreted matrix (Figure 5B). Likewise no increase in KS keratinocyte adhesion was seen when these cells were plated onto laminin-332-, fibronectin-, or collagen-coated wells (data not shown).

Figure 5.

KS keratinocytes show reduced adhesion to underlying secreted ECM. A: Adhesion of NHKs and KS keratinocytes to their own secreted ECM. There is reduced adhesion for KS keratinocytes when plated onto their own secreted ECM (P < 0.05). B: Adhesion of KS keratinocytes did not improve after plating onto ECM secreted by NHKs (P < 0.05).

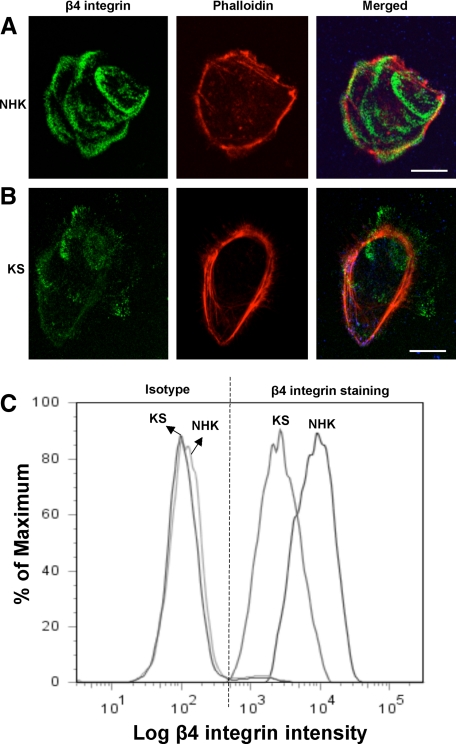

Kindler Syndrome Keratinocytes Display Reduced β4 Integrin Surface Expression

To further assess the skin phenotype in KS, we examined the pattern of expression of the hemidesmosome-associated component, β4 integrin, in cultured KS keratinocytes. In NHKs, there was bright β4 integrin labeling within the cell (Figure 6A). In contrast, there was reduced labeling intensity for β4 integrin in KS keratinocytes (Figure 6B). Quantification of β4 integrin surface expression by flow cytometry showed a marked reduction in the mean surface expression of this integrin in KS keratinocytes (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

β4 Integrin profile. A: Confocal microscopy studies on NHKs show bright labeling for β4 integrin (green). Phalloidin staining is shown in red. B: In contrast, there is a marked reduction in β4 integrin labeling in KS keratinocytes. C: Flow cytometry shows marked reduction in the fluorescent intensity of β4 integrin surface expression of KS keratinocytes compared with that of NHKs. Scale bar = 20 μm.

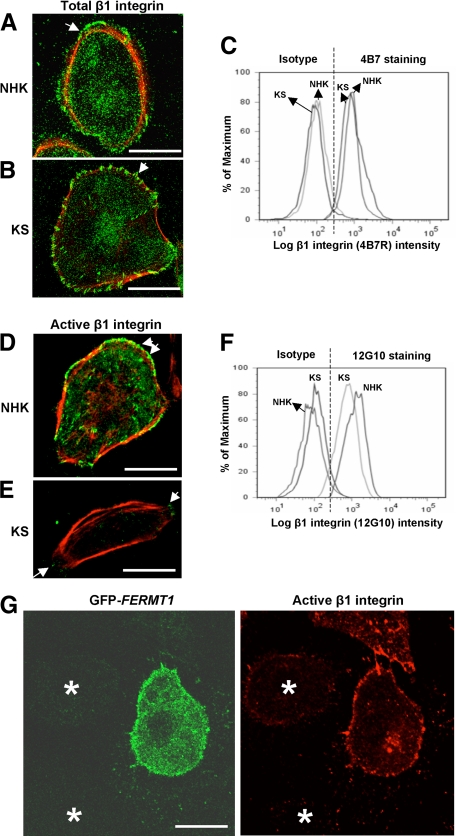

Kindler Syndrome Keratinocytes Express Reduced Active β1 Integrin But Normal Total β1 Integrin Levels

To investigate keratinocyte-extracellular matrix interactions, we assessed the activation status of β1 integrin in KS keratinocytes and NHKs. By confocal microscopy assessment, total surface β1 integrin labeling using the mouse monoclonal anti-β1 integrin antibody (clone 4B7R) was similar in both NHKs and KS keratinocytes (Figures 7, A and B). Flow cytometry analysis also revealed similar levels of total β1 integrin surface expression in both NHKs and KS keratinocytes (Figure 7C). Active β1 integrin detected by the mouse monoclonal anti-β1 integrin antibody (clone 12G10) also localized at focal adhesions in NHKs (Figure 7D). Of note, in KS keratinocytes, there was marked reduction in labeling intensity of active β1 integrin at focal adhesions (Figure 7E). This was confirmed by flow cytometry, which showed a reduction in peak fluorescence intensity in KS keratinocytes compared with NHKs (Figure 7F). Furthermore, there was no difference in talin expression between NHKs and KS keratinocytes by immunoblotting (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Total and active β1 integrin profiles in NHKs and KS keratinocytes. Only merged confocal microscopy images are shown. A: Confocal microscopy investigating total β1 integrin labeling shows bright green colocalization in NHKs (arrow). B: Likewise there is bright green colocalization for total β1 integrin in KS keratinocytes (arrow); C: Flow cytometry shows similar levels of fluorescent intensities for total β1 integrin in both NHKs and KS keratinocytes. D: Confocal microscopy for active β1 integrin shows bright green colocalization at focal adhesions (arrows) in the merged image of NHKs. E: In KS keratinocytes, there is reduced labeling for active β1 integrin at focal adhesions (arrows). F: Flow cytometry analysis shows a reduction in peak fluorescent labeling intensity for active β1 integrin in KS keratinocytes compared with NHKs. G: Overexpression of FFH1 using the expression plasmid GFP-FERMT1 results in an increase in integrin activation (red) in transfected KS keratinocytes (green), whereas the untransfected KS keratinocytes show reduced integrin activation. Asterisks denote the untransfected keratinocytes. Scale bar = 20 μm.

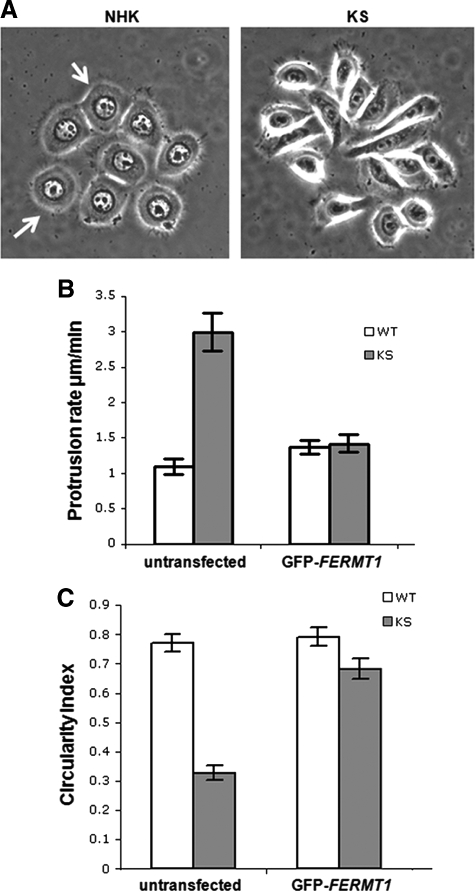

Overexpression of FFH1 in KS Keratinocytes Restores β1 Integrin Activation and Rescues the Cellular Phenotype

To study the functional role of FFH1 in β1 integrin activation, we overexpressed FFH1 in both NHKs and KS keratinocytes by transfecting them with a GFP-FERMT1 expression plasmid. No difference in active β1 integrin immunolabeling intensity was observed in NHKs after FFH1 overexpression (data not shown). In contrast, transfected KS keratinocytes showed a marked increase in active β1 integrin staining by confocal microscopy analysis compared with untransfected KS keratinocytes (Figure 7G). To determine whether FFH1 was able to rescue the KS keratinocyte phenotype, we acquired live phase-contract time-lapse movies of both NHKs and KS cells and measured the membrane protrusion rates as well as the circularity index of each cell type. Untransfected NHKs showed a round morphology (ie, closer to 1), whereas KS keratinocytes displayed a more elongated shape (ie, closer to 0) (Figure 8A). In addition, kymography analysis revealed that untransfected KS keratinocytes showed a significantly higher rate of protrusion compared with the untransfected NHKs. Interestingly, protrusion rates in KS keratinocytes expressing GFP-FERMT1 were reduced back to levels seen in NHKs (Figure 8B). Likewise transfected KS keratinocytes had an increased circularity index compared with that of untransfected KS cells (Figure 8C). However, treatment of cells with manganese ions to activate all integrins did not rescue KS cell adhesion or migration defects (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Keratinocyte rescue after FFH1 overexpression. A: Untransfected NHKs have a round morphology and associated fine filopodia at the cell periphery (arrows). In contrast, KS keratinocytes are more elongated with prominent filopodial and membrane protrusions. B: Kymography analysis of untransfected NHKs and KS keratinocytes shows that KS have significantly higher protrusion rates than NHKs (P < 0.05). Expression of GFP-FERMT1 leads to a rescue of KS protrusion rates. C: Likewise, after overexpression of FFH1, there is a significant increase in the KS circularity index to a level comparable with that of NHKs (1, perfect circle; 0, straight line) (P < 0.05). WT, wild type.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that FFH1 deficiency is associated with cutaneous basement membrane zone abnormalities and reduced integrin activation. Furthermore, overexpression of FFH1 is able to restore integrin activation in KS keratinocytes and partially rescue the KS cell protrusion and migration defects. In KS skin, we observe basement membrane reduplication and interrupted labeling for several hemidesmosomal and ECM components, findings that expand data from previous reports.7,13,40 To further dissect these abnormalities, we examine the secretion of the major basement membrane component laminin-332 as well as hemidesmosomal organization in KS keratinocytes. Our data also demonstrate a reduction in β1 integrin expression in KS skin and decreased β1 integrin activation in KS keratinocytes, thus indicating a potential role of FFH1 in regulating integrin function.

The FFH protein family members have recently been implicated in integrin activation. FFH2 and 3 (kindlin-2 and kindlin-3) have been shown to activate integrins through their binding to the membrane distal NxxY motif of β1 and β3 integrins in combination with talin recruitment to the proximal NPxY motif of the same integrins.30,31,33 Although FFH1 has been implicated in the regulation of integrin function through observations of impaired cell adhesion and delayed cell spreading,5,12,17 little is known about whether FFH1 is able to activate integrin. In our study, we demonstrate that KS keratinocytes have reduced β1 integrin activation. This result is further corroborated by the finding of reduced β1 integrin in FFH1 knockout murine keratinocytes in which the start codon of exon 2 has been replaced with a neomycin-resistant cassette.42 Although the mechanism by which FFH1 activates β1 integrin is unclear, FFH1 has been shown to require talin as a cofactor to activate αIIbβ3 integrin in Chinese hamster ovary cells that stably express this integrin.42 Thus, a consequence of reduced β1 integrin activation is a decrease in the adhesion of KS keratinocytes to the underlying ECM, which, in tandem with the abnormal deposition of ECM components such as laminin-332, may explain the blistering skin phenotype in KS. To confirm that FFH1 is required for efficient integrin activation, we show that overexpression of FFH1 in KS keratinocytes is able to restore integrin activation and partially rescue KS cell protrusion and migration defects. Interestingly, however, addition of exogenous manganese ions to KS keratinocytes did not rescue the migratory and adhesion defects, suggesting an intrinsic role for FFH1 in regulating cell migration and adhesion, possibly due to direct modulation of integrin function. This result is in agreement with previous observations that FFH3-deficient platelets exposed to manganese ions still show impaired platelet spreading.43

Epidermal atrophy is a characteristic finding in KS. To explore this further, we hypothesized that loss of FFH1 may cause an epidermal stem cell defect through a mechanism involving β1 integrin. Several lines of evidence suggest that β1 integrin is implicated in the maintenance of epidermal stemness. First, conditional β1 integrin knockout mice have previously been shown to have severe defects in epidermal proliferation.44 Second, mice in which a keratinocyte-specific deletion of β1 integrin was generated were found to have both hair and skin abnormalities and a reduction in basal keratinocyte proliferation.45 Third, deletion of β1 integrin in mammary epithelial basal cells abrogates the maintenance of the mammary stem cell population.46 Fourth, lack of β1 integrin in Drosophila melanogaster gonad stem cells damages the stem cell niche.47 Our study also showed decreased expression of several other stem cell markers (cytokeratin 15 and α6 integrin) in KS skin. Taken together, the data raise the possibility that defective or absent FFH1 may be linked to an epidermal stem cell defect. Cytokeratin 15 is a marker of hair bulge stem cells, which contribute to the maintenance of the hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and interfollicular epidermis,48,49,50 whereas α6 integrin is also a stem cell marker expressed in basal keratinocytes.51,52 Because an intact basement membrane, containing key extracellular matrix components such as laminin-332, is required for the maintenance of the proliferative capacity of the epidermis,53 the severe disruption of the cutaneous basement membrane zone in KS may affect the proliferative capacity of epidermal keratinocytes, resulting in loss of several epidermal stem cell markers. An alternative explanation is that KS skin has undergone several episodes of epidermal separation and antigen loss due to release of proteolytic enzymes that may have led to degradation of integrin subunits at the DEJ, thereby resulting in a reduction in immunolabeling intensity. It has to be noted, however, that immunofluorescence microscopy labeling was performed on poikilodermatous skin, which, to our knowledge, had previously not undergone blistering. Moreover, the basement membrane disruption has been noted previously in neonatal KS skin, ie, before the occurrence of any skin blisters.54

In conclusion, our study highlights an important role of FFH1 in integrin activation and hemidesmosomal and ECM biology as well as in epidermal stem cell maintenance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to John A. McGrath, M.D. F.R.C.P., St John’s Institute of Dermatology Laboratories, 9th Floor Tower Wing, Guy’s Hospital, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, UK. E-mail: john.mcgrath@kcl.ac.uk.

Supported by the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. J.L-C. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship and by awards from the British Skin Foundation, British Association of Dermatologists, and Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.

References

- Kindler T. Congenital poikiloderma with traumatic bulla formation and progressive cutaneous atrophy. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1954.tb12598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobard F, Bouadjar B, Caux F, Hadj-Rabia S, Has C, Matsuda F, Weissenbach J, Lathrop M, Prud'homme JF, Fischer J. Identification of mutations in a new gene encoding a FERM family protein with a pleckstrin homology domain in Kindler syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:925–935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DH, Ashton GH, Penagos HG, Lee JV, Feiler HS, Wilhelmsen KC, South AP, Smith FJ, Prescott AR, Wessagowit V, Oyama N, Akiyama M, Al Aboud D, Al Aboud K, Al Githami A, Al Hawsawi K, Al Ismaily A, Al-Suwaid R, Atherton DJ, Caputo R, Fine JD, Frieden IJ, Fuchs E, Haber RM, Harada T, Kitajima Y, Mallory SB, Ogawa H, Sahin S, Shimizu H, Suga Y, Tadini G, Tsuchiya K, Wiebe CB, Wojnarowska F, Zaghloul AB, Hamada T, Mallipeddi R, Eady RA, McLean WH, McGrath JA, Epstein EH. Loss of kindlin-1, a human homolog of the Caenorhabditis elegans actin-extracellular-matrix linker protein UNC-112, causes Kindler syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:174–187. doi: 10.1086/376609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton GH, McLean WH, South AP, Oyama N, Smith FJ, Al-Suwaid R, Al-Ismaily A, Atherton DJ, Harwood CA, Leigh IM, Moss C, Didona B, Zambruno G, Patrizi A, Eady RA, McGrath JA. Recurrent mutations in kindlin-1, a novel keratinocyte focal contact protein, in the autosomal recessive skin fragility and photosensitivity disorder, Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:78–83. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz C, Aumailley M, Schulte C, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Has C. Kindlin-1 is a phosphoprotein involved in regulation of polarity, proliferation, and motility of epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36082–36090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Cheong JE, Ussar S, Arita K, Hart IR, McGrath JA. Colocalization of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin at keratinocyte focal adhesion and relevance to the pathophysiology of Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2156–2165. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Cheong JE, Liu L, Sethuraman G, Kumar R, Sharma VK, Reddy SR, Vahlquist A, Pather S, Arita K, Wessagowit V, McGrath JA. Five new homozygous mutations in the KIND1 gene in Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2268–2270. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Cheong JE, Tanaka A, Hawche G, Emanuel P, Maari C, Taskesen M, Akdeniz S, Liu L, McGrath JA. Kindler syndrome: a focal adhesion genodermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:233–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Song S, Zhang J. A novel 3017-bp deletion mutation in the FERMT1 (KIND1) gene in a Chinese family with Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1119–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel PO, Rudikoff D, Phelps RG. Aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in Kindler syndrome. Skinmed. 2006;5:305–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2006.05369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Bruckner-Tuderman L. A novel nonsense mutation in Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:84–86. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Ludwig RJ, Herz C, Kern JS, Ussar S, Ochsendorf FR, Kaufmann R, Schumann H, Kohlhase J, Bruckner-Tuderman L. C-terminally truncated kindlin-1 leads to abnormal adhesion and migration of keratinocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1192–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Wessagowit V, Pascucci M, Baer C, Didona B, Wilhelm C, Pedicelli C, Locatelli A, Kohlhase J, Ashton GH, Tadini G, Zambruno G, Bruckner-Tuderman L, McGrath JA, Castiglia D. Molecular basis of Kindler syndrome in Italy: novel and recurrent Alu/Alu recombination, splice site, nonsense, and frameshift mutations in the KIND1 gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1776–1783. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Yordanova I, Balabanova M, Kazandjieva J, Herz C, Kohlhase J, Bruckner-Tuderman L. A novel large FERMT1 (KIND1) gene deletion in Kindler syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;52:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaçar N, Semerci N, Ergin S, Pascucci M, Zambruno G, Castiglia D. A novel frameshift mutation in the KIND1 gene in Turkish siblings with Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1375–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler E, Klausegger A, Muss W, Deinsberger U, Pohla-Gubo G, Laimer M, Lanschuetzer C, Bauer JW, Hintner H. Novel KIND1 gene mutation in Kindler syndrome with severe gastrointestinal tract involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1619–1624. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.12.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloeker S, Major MB, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH, Jones DA, Beckerle MC. The Kindler syndrome protein is regulated by transforming growth factor-β and involved in integrin-mediated adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6824–6833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harburger DS, Bouaouina M, Calderwood DA. Kindlin-1 and -2 directly bind the C-terminal region of β integrin cytoplasmic tails and exert integrin-specific activation effects. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11485–11497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809233200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larjava H, Plow EF, Wu C. Kindlins: essential regulators of integrin signalling and cell-matrix adhesion, EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1203–1208. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood DA. Talin controls integrin activation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:434–437. doi: 10.1042/BST0320434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood DA, Zent R, Grant R, Rees DJ, Hynes RO, Ginsberg MH. The Talin head domain binds to integrin β subunit cytoplasmic tails and regulates integrin activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28071–28074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieswandt B, Moser M, Pleines I, Varga-Szabo D, Monkley S, Critchley D, Fassler R. Loss of talin1 in platelets abrogates integrin activation, platelet aggregation, and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3113–3118. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrich BG, Fogelstrand P, Partridge AW, Yousefi N, Ablooglu AJ, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. The antithrombotic potential of selective blockade of talin-dependent integrin αIIbβ3 (platelet GPIIb-IIIa) activation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2250–2259. doi: 10.1172/JCI31024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrich BG, Marchese P, Ruggeri ZM, Spiess S, Weichert RA, Ye F, Tiedt R, Skoda RC, Monkley SJ, Critchley DR, Ginsberg MH. Talin is required for integrin-mediated platelet function in hemostasis and thrombosis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3103–3111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova O, Vaynberg J, Kong X, Haas TA, Plow EF, Qin J. Membrane-mediated structural transitions at the cytoplasmic face during integrin activation, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4094–4099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400742101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener KL, Partridge AW, Han J, Pickford AR, Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH, Campbell ID. Structural basis of integrin activation by talin. Cell. 2007;128:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JJ, Gibbs E, Russell M, Goldman D, Minarcik J, Golden JA, Feldman EL. Kindlin-2 is an essential component of intercalated discs and is required for vertebrate cardiac structure and function. Circ Res. 2008;102:423–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M, Moser M, Ussar S, Thievessen I, Luber CA, Forner F, Schmidt S, Zanivan S, Fassler R, Mann M. SILAC mouse for quantitative proteomics uncovers kindlin-3 as an essential factor for red blood cell function. Cell. 2008;134:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YQ, Qin J, Wu C, Plow EF. Kindlin-2 (Mig-2): a co-activator of β3 integrins. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:439–446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanez E, Ussar S, Schifferer M, Bosl M, Zent R, Moser M, Fassler R. Kindlin-2 controls bidirectional signaling of integrins. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1325–1330. doi: 10.1101/gad.469408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mory A, Feigelson SW, Yarali N, Kilic SS, Bayhan GI, Gershoni-Baruch R, Etzioni A, Alon R. Kindlin-3: a new gene involved in the pathogenesis of LAD-III. Blood. 2008;112:2591. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Nieswandt B, Ussar S, Pozgajova M, Fassler R. Kindlin-3 is essential for integrin activation and platelet aggregation. Nat Med. 2008;14:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nm1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Howarth K, McDowall A, Patzak I, Evans R, Ussar S, Moser M, Metin A, Fried M, Tomlinson I, Hogg N. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency-III is caused by mutations in KINDLIN3 affecting integrin activation. Nat Med. 2009;15:306–312. doi: 10.1038/nm.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinin NL, Zhang L, Choi J, Ciocea A, Razorenova O, Ma YQ, Podrez EA, Tosi M, Lennon DP, Caplan AI, Shurin SB, Plow EF, Byzova TV. A point mutation in KINDLIN3 ablates activation of three integrin subfamilies in humans. Nat Med. 2009;15:313–318. doi: 10.1038/nm.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers TW, van de Vijver E, Weterman MA, de Boer M, Tool AT, van den Berg TK, Moser M, Jakobs ME, Seeger K, Sanal O, Unal S, Cetin M, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ, Baas F. LAD-1/variant syndrome is caused by mutations in FERMT3. Blood. 2009;113:4740–4746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussar S, Wang HV, Linder S, Fassler R, Moser M. The kindlins: subcellular localization and expression during murine development. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3142–3151. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong T, Gammon L, Liu L, Mellerio JE, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Pacy J, Elia G, Jeffery R, Leigh IM, Navsaria H, McGrath JA. Potential of fibroblast cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2179–2189. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert CL, Demers GW, Galloway DA. The E7 gene of human papillomavirus type 16 is sufficient for immortalization of human epithelial cells. J Virol. 1991;65:473–478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.473-478.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton GH. Kindler syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martignago BC, Lai-Cheong JE, Liu L, McGrath JA, Cestari TF. Recurrent KIND1 (C20orf42) gene mutation, c.676insC, in a Brazilian pedigree with Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1281–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussar S, Moser M, Widmaier M, Rognoni E, Harrer C, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, Fassler R. Loss of kindlin-1 causes skin atrophy and lethal neonatal intestinal epithelial dysfunction, PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Legate KR, Zent R, Fassler R. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science. 2009;324:895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of β1 integrin in skin: severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination, J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, Grose R, Quondamatteo F, Ramirez A, Jorcano JL, Pirro A, Svensson M, Herken R, Sasaki T, Timpl R, Werner S, Fassler R. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on β1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei I, Deugnier MA, Faraldo MM, Petit V, Bouvard D, Medina D, Fassler R, Thiery JP, Glukhova MA. β1 Integrin deletion from the basal compartment of the mammary epithelium affects stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:716–722. doi: 10.1038/ncb1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanentzapf G, Devenport D, Godt D, Brown NH. Integrin-dependent anchoring of a stem-cell niche. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1413–1418. doi: 10.1038/ncb1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper JE, Tiede S, Brinckmann J, Reinhardt DP, Meyer W, Faessler R, Paus R. Immunophenotyping of the human bulge region: the quest to define useful in situ markers for human epithelial hair follicle stem cells and their niche. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:592–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Liu Y, Marles L, Yang Z, Trempus C, Li S, Lin JS, Sawicki JA, Cotsarelis G. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:411–417. doi: 10.1038/nbt950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama M, Terunuma A, Tock CL, Radonovich MF, Pise-Masison CA, Hopping SB, Brady JN, Udey MC, Vogel JC. Characterization and isolation of stem cell-enriched human hair follicle bulge cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:249–260. doi: 10.1172/JCI26043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K, Rupf T, Salvetter J, Bader A. Enrichment of human β1/α6bri/CD71dim keratinocytes after culture in defined media. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189:382–390. doi: 10.1159/000151291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani H, Morris RJ, Kaur P. Enrichment for murine keratinocyte stem cells based on cell surface phenotype, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10960–10965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. Skin stem cells: rising to the surface. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:273–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassihi H, Wessagowit V, Jones C, Dopping-Hepenstal P, Denyer J, Mellerio JE, Clark S, McGrath JA. Neonatal diagnosis of Kindler syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;39:183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]