Abstract

Objective

Medication nonadherence is presumed to be related to poor clinical outcomes, yet this relationship rarely has been tested using objective adherence measures in patients with heart failure. Which objective indicators of medication adherence predict clinical outcomes are unknown. The study objective was to determine which indicators of medication adherence are predictors of event-free survival.

Methods

Patients (N = 134) with heart failure (69% were male, aged 61 ± 11 years, 61% with New York Heart Association class III/IV heart disease) were enrolled in this 6-month longitudinal study. Adherence was measured using two measures: 1) an objective measure, the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS); and 2) self-reported adherence (Medical Outcomes Studies Specific Adherence Scale). Three indicators of adherence were assessed by MEMS: 1) dose-count, percentage of prescribed doses taken; 2) dose-days, percentage of days correct number of doses taken; and 3) dose-time, percentage of doses taken on schedule. Events (emergency department visits, rehospitalization, and mortality) were obtained by patient/family interview and hospital databases.

Results

In Cox regression, two of the three MEMS indicators, dose-count and dose-day, predicted event-free survival before and after controlling for age, gender, ejection fraction, New York Heart Association class, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, and beta-blocker use (P = .004, P = .008, and P = .224, respectively). Self-report adherence did not predict outcomes (P = .402).

Conclusion

Dose-count and dose-day predicted event-free survival. Neither dose-time nor self-reported adherence predicted outcomes. Health care providers should assess specific behaviors related to medication taking rather than a global patient self-assessment of patient adherence.

Keywords: Heart failure, Medication adherence, Objective measure, Outcomes

Patients with heart failure (HF) require multiple medications to control symptoms, slow the progressive nature of cardiac remodeling, decrease rehospitalization, and improve survival.1,2 To achieve these outcomes, patient adherence to prescribed medications is vital, yet estimates of medication adherence rates in patients with HF are sub-optimal, ranging from a low of 7% in some reports, depending on how adherence is measured.3–16 Available data suggest that up to one half of hospitalizations for HF could be prevented. Poor adherence is presumed to play a major role in these preventable rehospitalizations.17 However, this assumption has rarely been directly tested using objective measures of adherence in HF. In most investigations of medication adherence in patients with HF, self-report measures of adherence have been used. The few studies that included objective measures of adherence provide no clear direction regarding which of the many indicators of medication adherence best predict outcomes.

In this study, we used a self-report measure and a well-established objective measure of adherence, the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS).18–24 The MEMS provides three indicators of adherence that reflect various aspects of medication-taking behavior: 1) dose-count, the percentage of prescribed doses taken; 2) dose-days, the percentage of days the correct number of doses taken; and 3) dose-time, the percentage of doses taken on schedule. It is unknown which of these indicators accurately predict outcomes. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to determine which of the three objective indicators of medication-taking behavior obtained from the MEMS are the best predictors of event-free survival. In addition, we included a self-report measure of adherence to determine how well the most common measure used in clinical practice predicts outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

In this prospective study, patients were interviewed at baseline and started medication adherence monitoring with the MEMS. They were followed monthly for 6 months by phone to determine emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and mortality.

Sample and Setting

Patients enrolled in this study met the following inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosis of chronic HF from either preserved (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥ 40%) or nonpreserved systolic function (LVEF < 40%);25 (2) underwent evaluation of HF by a cardiologist and optimization of medical therapy, defined as receiving stable doses of HF medications for 1 month with no plans to add HF medications or titrate further; and (3) able to read and speak English. Patients were excluded if they had (1) obvious cognitive impairment, including not being able to give informed consent or participate in an interview; (2) a coexisting terminal illness, such as cancer or chronic renal failure requiring dialysis; (3) a myocardial infarction within the past 3 months; or (4) a history of cerebral vascular accident within the past 3 months or with major sequelae. Patients were recruited for this study from outpatient cardiology clinics in Lexington, Kentucky.

Measurement

Medication adherence

Medication adherence was defined as the extent to which the patient’s medication-taking behavior corresponded with the prescribed medication regimen. Medication adherence was measured objectively and by patient self-report. Medication adherence was measured objectively using an unobtrusive microelectronic monitoring device in the caps of medication containers: the MEMS. The MEMS documents each time that the cap is removed from a medication bottle.26–27 Real-time data were collected on the device and later transferred to a computer. Data were collected on one HF medication (e.g., (β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor, diuretic, digoxin) for each patient. The investigator chose the medication to be monitored on the basis of the following criteria. If the patient was taking a medication twice per day, this medication was chosen for monitoring using the MEMS. If all medications were taken only once per day, then the beta-blocking agent was chosen unless the patient was not prescribed one, in that case, the ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. Only one medication was monitored using the MEMS because it is impractical and burdensome to use multiple MEMS and prior research has demonstrated that monitoring one medication with the MEMS provides a valid indicator that patients took all of their medications.26–28 Moreover, medication adherence measured using one medication in the MEMS predicted rehospitalization and mortality, providing further evidence for the validity of monitoring only one medication.29 Three indicators of adherence were assessed by the MEMS: 1) dose-count, defined as the percentage of prescribed number of doses taken; 2) dose-days, defined as the percentage of days the correct number of doses taken; and 3) dose-time, defined as the percentage of doses taken on schedule (within 25% of expected time interval [i.e., 24 ± 6 hours for once-per-day and 12 ± 3 hours for twice-per-day doses]).26–27

The MEMS is a valid instrument that has been used to measure medication adherence with high sensitivity in patients with cardiovascular disease26–28,30 or HF.12,28,31 The MEMS was chosen over the more commonly used pharmacy refill, or pill count, for four major reasons. First, the MEMS is an objective measure and has been used as a reference standard for medication adherence assessment in clinical trials. 18–24 Second, by using the MEMS, real-time data are collected. Third, by using the MEMS, detailed information about how patients adhere to their medication can be collected.26–27 Fourth, the MEMS can assess short-term and long-term adherence.32

Self-report medication adherence was assessed using one item from the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Specific Adherence Scale.33–34 The MOS Specific Adherence Scale was developed for patients with diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. The scale has adequate reliability and validity,33–34 and has been used successfully to measure adherence in patients with HF.35 In this study, only the one question from the MOS Specific Adherence Scale that is related to medication adherence was used. Patients were asked to rate “how often did you take medication as prescribed (on time without skipping doses) in the past 4 weeks?” on a scale from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Higher scores indicated higher reported medication adherence.

Outcome

The primary endpoint for this study was event-free survival. Data were collected on ED visits for symptoms of decompensated HF, rehospitalizations, and mortality.

ED visit

ED visits for decompensated HF were determined by a combination of medical record review, review of hospital administrative records, and patient and family interview. Dates and reasons for all ED visits were noted. Patients and families were interviewed to obtain self-reports of ED visits. These data were used to augment automated data because of the possibility that a patient visited the ED of a hospital other than that in our system. If there was a difference between patient self-report and the hospital administrative records, we carefully reviewed the medical record to confirm the visit date and reason, and called the patient to clarify the data. If the ED visit was outside the system, a patient release was obtained and the medical record of the visit was reviewed. In all cases, conflicting data between patient report and administrative records were resolved with review of the medical record and interview of the patient and family.

Rehospitalization

Rehospitalization was determined by a combination of medical record review, review of hospital administrative records, and patient and family interview. Dates and reasons for all hospitalizations were noted. Patients and families were interviewed to obtain self-reports of admissions that were used to validate and augment automated data because of the possibility that a patient was admitted to a different hospital. Research associates were trained to carefully interview patients to identify all admissions. In addition, patients were asked to keep a diary of all hospital admissions.36 Although interview is subject to recall bias, we have found that with careful questioning and discussion with patients/family/caregivers, patients were able to recall admissions and the approximate dates. When patient recall varied from hospital records, we validated the admission using hospital records. For hospital admissions outside the system, discharge reports released to the patient were reviewed or we obtained the medical records after obtaining a patient release. The use of a variety of methods for tracking rehospitalizations ensured that all hospitalizations were tracked and the reasons for each were appropriately assigned.

Mortality

Mortality was determined by a combination of medical record review, discussion with patients’ health care providers and family, automated hospital records, and review of county death records to obtain date and cause of death. At enrollment, patients were asked for contact information on a relative or close friend to be used if they are unable to be contacted. For patients we are unable to reach by telephone, health care providers were contacted and automated hospital records were checked first to see whether the patient had died. If such evidence was not found, the friend or relative was contacted. If the patient or these contacts could not be located during follow-up or if additional information was needed, the county death records were searched. Although death certificates were usually a valid source of data about the date of death, they were less valid for determining cause of death and supplemental data were always sought to establish whether the death was cardiac or noncardiac. In a previous study,37 we used these methods successfully to accurately categorize deaths.

Covariates

To characterize patients and obtain data on potential confounding variables, information concerning the following additional variables were collected from the medical record or patient interview: age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, financial status, LVEF, cause of HF, and medication regimen (ACE inhibitors [yes/no], 3-blockers [yes/no]).

Procedure

Permission for the conduct of the study was obtained from the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board. Patients were referred by nurse practitioners in the HF clinic. Patient eligibility was confirmed by a trained research associate. The research associate explained study requirements to the eligible patients and obtained informed, written consent.

At enrollment, patients visited to the General Clinical Research Center of the University of Kentucky Medical Center for data collection; patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were collected by interview and medical record review. Patients completed the questionnaires and were provided detailed written and verbal instructions on use of the MEMS bottle. Patients recorded the time and date of unscheduled cap openings (i.e., to refill the bottle, check on supply, or accidentally openings) in a medication diary to increase validity of the data collected using the MEMS. These events were excluded when data were downloaded. Patients who used a pill box kept the MEMS bottle beside their pill box and took the medicine from the MEMS bottle.

Patients used the MEMS for 3 months, starting at enrollment. We chose the 3-month time period to avoid overburdening the patient with a longer data-collection period and to allow time for the patient to acclimate to the MEMS. Three months is the most commonly used time period in adherence research and has been shown to accurately reflect long-term adherence.26,27

After the 3-month time period, patients returned the MEMS to the investigators and the data were downloaded onto a computer using manufacturer-supplied communicator and software. MEMS data were then printed and entered into a data file for analyses. Data regarding ED visits, rehospitalizations, and mortality were collected for 6 months from enrollment.

Data Management and Analysis

Before conducting analyses, all data were verified. There were no problems with multicollinearity or violations of linearity, independence, and homoscedasticity assumptions. Because medication adherence measured by the MEMS was skewed toward low scores, the data were transformed using a log transformation for all Cox regression models. Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), version 14.0 with an alpha of 0.05 set a priori.

For each indicator, the log-rank test for comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves was used to determine whether adherent patients have a longer time of event-free survival compared with nonadherent patients. The median value for adherence for each of the indicators of the MEMS was used as the cutpoint to categorize patients as adherent versus nonadherent. For the self-report measure, patients who self-reported taking medication as prescribed “all of the time” and “most of the time” were categorized as adherent, and those who reported “a good bit of the time,” “some of the time,” “a little of the time,” and “none of the time” were categorized as nonadherent. Although this categorization is arbitrary, there are no data existing that definitively identify the level of adherence that is optimal. Thus, we classified “all of the time” and “most of the time” as adherent based on suggestions from the literature that approximately 80—85% adherence is considered good adherence, and that “most of the time” to “all of the time” on self-report encompass 80—100% adherence.12,38–40 Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to determine whether medication adherence predicted the length of time to the first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, and mortality after controlling for appropriate demographic and clinical variables.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 301 eligible patients with HF who were approached for the study, 152 patients refused to participate because of the long travel distance, time concerns (e.g., have to take care of other family members), no interest in participating in research, or lack of energy. We recruited 149 patients, but two patients died after recruitment and before completing baseline assessment. In this study, we only included the data for the 134 patients for whom we have full data from the MEMS. MEMS data were missing in 13 patients because of malfunction of the MEMS cap (n = 2), the patient lost or never returned the MEMS cap or died during data collection (n = 7), or problems with the software interface (n = 4). The mean age of patients in the sample was 61 ± 11 years. The most common HF cause was ischemic heart disease. The sample consisted largely of patients with advanced HF, reflected by their New York Heart Association functional class. The average LVEF reflected the enrollment of patients with and without systolic dysfunction. Full sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants (N = 134)

| Characteristics | Range (Mean ± SD) or No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 24–87 y (60.9 ± 11.3) |

| Gender (male/female) | 93/41 (69%/31%) |

| Race | |

| White | 121 (90%) |

| African American | 13 (10%) |

| Years of education | 0–22 y (12.6 ± 3.3) |

| Education categories | |

| <12 y | 34 (25.6%) |

| High school | 35 (26.3%) |

| College | 53 (39.8%) |

| Graduate school | 11 (8.3%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/cohabitate | 84 (63%) |

| Single/divorce/widow | 50 (37%) |

| Financial status | |

| Comfortable | 32 (24%) |

| Enough to make ends meet | 70 (53%) |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 30 (23%) |

| Cause | |

| Ischemic | 80 (61%) |

| Idiopathic | 27 (20%) |

| Hypertensive | 8 (6%) |

| Other (e.g., alcoholic) | 17 (13%) |

| LVEF, % | 7–70(34.5 ± 14) |

| NYHA | |

| Class I/II | 51 (39%) |

| Class III/IV | 80 (61%) |

| Comorbidity | 1–10 (3.3 ± 1.7) |

| 1 | 12 (9%) |

| 2 | 37 (28%) |

| 3 | 27 (20%) |

| ≥ 4 | 57 (43%) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

Description of Medication Adherence

Medication adherence (Table 2) measured by the MEMS showed a mean dose-time adherence (percentage of prescribed doses taken) of 89%, a mean dose-day adherence (percentage of days the correct number of doses taken) of 81%, and a mean dose-time adherence (percentage of doses taken on schedule) of 67%. The majority of patients in this study self-reported taking their medication as prescribed on time without skipping doses either all of the time or most of the time (67%, 24%, respectively) in the past 4 weeks. The majority (72%) of patients took at least one medication twice daily, and this medication was monitored using the MEMS. There were no differences in self-reported medication adherence between those who had medication prescribed twice daily and those with medications prescribed once daily (P = 1.0). There were no differences in the prescribed number of doses taken (88.3% ± 16% vs 89.8% ± 14%, P = .63) or the percentage of days the correct number of doses were taken (79.1% ± 24% vs 85.1% ± 19%, P = .17) between the two groups. Patients who had medications prescribed once per day only took a higher percentage (76.4% ± 26%) of their prescribed doses on time compared with those who had a medication prescribed twice per day (63.0% ± 29%, P = .013).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Medication Adherence

| Indicator | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose-count* | 88.7 | 15.6 | 95.4 | 12.2 | 101.6 |

| Dose-day† | 80.8 | 22.8 | 90.3 | 0 | 100 |

| Dose-time‡ | 66.8 | 28.3 | 76.0 | 0 | 100 |

| Self-report medication adherence | 4.48 | .9 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

SD, standard deviation.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

The correlation between medication adherence measured by the MEMS and measured by self-report (Table 3) was significant but weak (0.23–0.39). Patients commonly over-estimated their level of medication adherence, resulting in the weak correlation between the two measures (Table 4). For example, 21 patients had less than 60% adherence on the MEMS measure of percentage of days the correct number of doses were taken. Of these 21 patients, 76.2% self-reported that they were adherent most or all of the time.

Table 3.

Correlation Between Medication Adherence Measured by the Medical Event Monitoring System and Self-reported Measure

P < .05.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

Table 4.

Comparison of Self-report and Objectively Measured Adherence

| Self-Report |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonadherent|| n(%) | Adherent§ n(%) | P | ||

| MEMS | ||||

| Dose-count* | .000 | |||

| 80%–100% | 4 (3.6) | 106 (96.4) | ||

| 60%–79.9% | 4 (26.7) | 11(73.3) | ||

| <60% | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | ||

| Dose-day† | .004 | |||

| 80%–100% | 3 (3.2) | 90 (96.8) | ||

| 60%–79.9% | 3(15) | 17 (85) | ||

| <60% | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | ||

| Dose-time‡ | .032 | |||

| 80%–100% | 1 (1.8) | 56 (98.2) | ||

| 60%–79.9% | 3 (8.8) | 31(91.2) | ||

| <60% | 7 (16.3) | 36 (83.7) | ||

MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

Self-reported adherence data, nonadherent, patient self-reported “took medication as prescribed” none, a little, some, and a good bit of the time.

Self-reported adherence data, adherent, patient self-reported “took medication as prescribed” most and all of the time.

Clinical Outcomes in Adherent/Nonadherent Patients

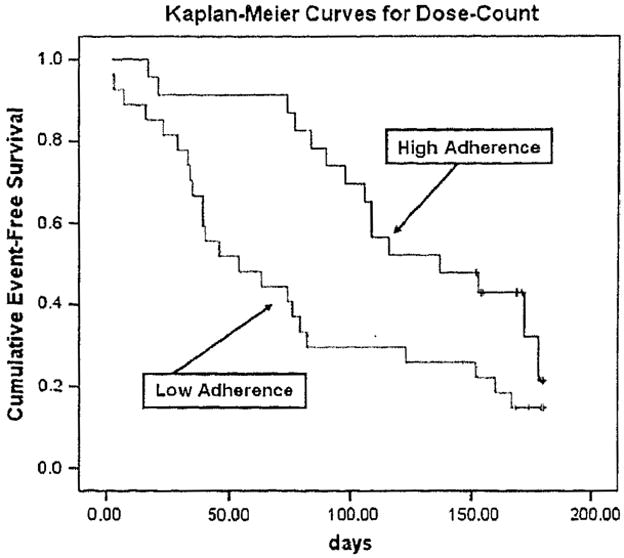

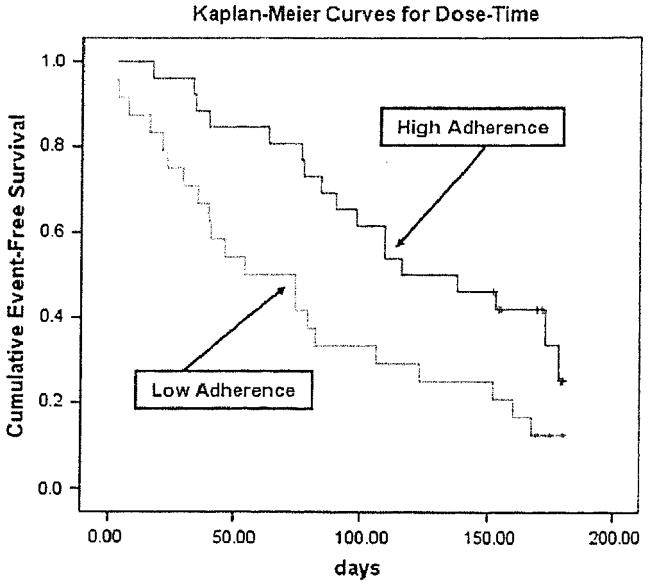

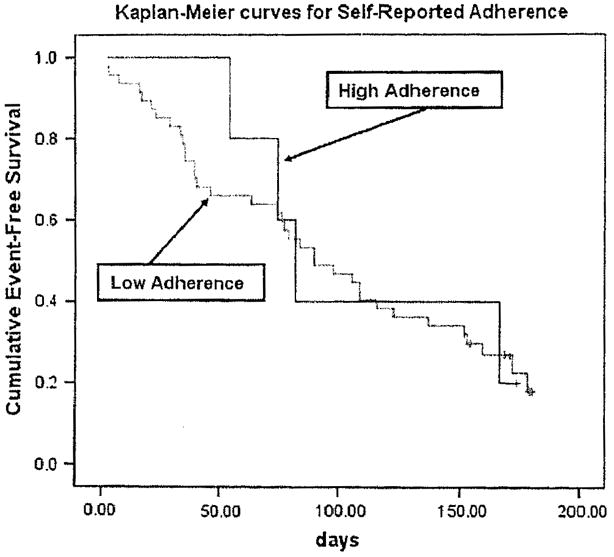

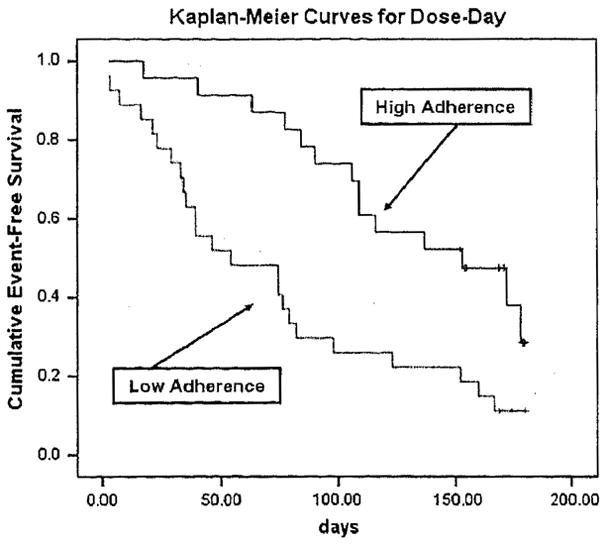

For each indicator of the MEMS, the median was used as the cutoff point (because no standard cut-points exist) to dichotomize patients as adherent or nonadherent. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that adherent patients had a longer time of event-free survival than nonadherent patients. The average time to the first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality was 151 days. Adherent patients had a longer time to the first event than nonadherent patients (290 vs. 133 days, respectively) according to the first indicator of the MEMS, dose-count. For all three objective indicators of medication adherence (dose-count, dose-day, and dose-time), the time to the first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality was significantly longer in adherent patients than in nonadherent patients (log-rank χ2 =5.74, 9.75, 5.78; P = .017, .002, .016, respectively) (Table 5, PFigures 1–3). However, there was no difference in event-free survival for self-report medication adherence ( = .897) (Figure 4).

Table 5.

Log-Rank Tests of Adherence and Nonadherent on Outcomes

| Indicator of the MEMS | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|

| Dose-count* | 5.736 | .017 |

| Dose-day† | 9.749 | .002 |

| Dose-time‡ | 5.782 | .016 |

| Self-report medication adherence | 0.017 | .897 |

MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

Fig. 1.

Medication adherence and time to first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality (dose-count).

Fig. 3.

Medication adherence and time to first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality (dose-time).

Fig. 4.

Medication adherence and time to first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality (self-reported medication adherence).

Predictors of Clinical Outcomes

In Cox regression, two of the three indicators of the MEMS, dose-count and dose-day, predicted the time to the first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality before and after controlling age, gender, LVEF, New York Heart Association, ACE inhibitor use, and β-blocker use (Tables 6 and 7). Patients with HF who had better medication adherence exhibited longer event-free survival before and after controlling for demographic and clinical variables. However, dose-time from the MEMS and self-report medication adherence from the MOS failed to predict time to the first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, and mortality before or after controlling for demographic and clinical variables. Thus, the effective predictors of outcomes were dose-count and dose-day.

Table 6.

Cox Regression of Effect of Medication Adherence on Event-Free Survival

| Variables | B | Wald | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| * Dose-count¶ | 1.376 | 8.273 | .004 |

| Age | 0.031 | 4.023 | .045 |

| Gender | −0.023 | 0.003 | .955 |

| LVEF | 0.001 | 0.006 | .939 |

| NYHA | 4.689 | .196 | |

| Med_ACEI | −0.956 | 6.226 | .013 |

| Med_BB | −1.241 | 6.544 | .011 |

| † Dose-day# | 1.173 | 6.982 | .008 |

| Age | 0.031 | 3.874 | .049 |

| Gender | 0.056 | 0.019 | .890 |

| LVEF | 0.003 | 0.044 | .834 |

| NYHA | 3.613 | .306 | |

| Med_ACEI | −0.918 | 5.585 | .010 |

| Med_BB | −1.173 | 6.568 | .008 |

| ‡ Dose-time** | 0.584 | 1.480 | .224 |

| Age | 0.029 | 3.561 | .059 |

| Gender | 0.113 | 0.077 | .781 |

| LVEF | 0.001 | 0.007 | .935 |

| NYHA | 4.582 | .205 | |

| Med_ACEI | −0.938 | 5.309 | .021 |

| Med_BB | −1.122 | 4.999 | .025 |

| || Self-reported adherence | −0.132 | 0.701 | .402 |

| Age | 0.022 | 2.563 | .109 |

| Gender | 0.198 | 0.290 | .590 |

| LVEF | −0.003 | 0.045 | .832 |

| NYHA | 0.187 | 0.829 | .363 |

| Med_ACEI | −0.642 | 2.950 | .086 |

| Med_BB | −1.088 | 4.809 | .028 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, beta blocker.

χ2 = 34.404, P < .001.

χ2 = 33.641, P < .001.

χ2 = 27.326, P = .001.

χ2 = 19.545, P = .007.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of closes taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

Table 7.

Simple Cox Regression Coefficients Between Medication Adherence and Composite Endpoint

| Indicator of the MEMS | * Beta | χ2 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose-count† | 1.209 | 7.637 | .006 |

| Dose-day‡ | 1.082 | 6.809 | .009 |

| Dose- time§ | 0.605 | 1.895 | .169 |

| Self-report medication adherence | 0.082 | 0.764 | .384 |

MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System.

Standardized beta.

MEMS data, dose-count: % of prescribed number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-day: % of days the correct number of doses taken.

MEMS data, dose-time: % of doses taken on schedule.

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence of the important impact of medication adherence on clinical outcomes and identify specific aspects of medication-taking behavior that are important to outcomes. The percentage of prescribed doses taken and percentage of days the correct number of doses were taken, but not percentage of doses taken on schedule, are predictors of health outcomes. This finding is important because it helps clinicians target education to specific aspects of medication-taking behavior that affect outcomes. It seems most important to emphasize that patients take all prescribed doses of their medications every day to maintain therapeutic drug action, rather than focusing on taking the medication at a specific scheduled time. In our study, patients had more difficulty taking medication on time (67%) than any other types of medication adherence (81%–89%), and taking medications on time was not related to outcomes. In this study, there were few differences in adherence (with the exception that patients prescribed twice-daily medications took fewer of the prescribed doses on time) between those taking medications once compared with twice daily. De-emphasizing taking medications at exact times while simply emphasizing the importance of taking medications daily may improve adherence if patients do not perceive adherence is so restrictive and difficult.

This study demonstrated that objectively measured medication-taking behavior that conforms to the health care provider’s prescription is associated with better clinical outcomes. The most adherent patients had the fewest occurrences of the composite endpoint of hospitalizations, ED visits, or mortality, even after controlling for age, gender, LVEF, New York Heart Association, ACE inhibitor use, and β-blocker use. This relationship held only when adherence was measured using the MEMS, an objective measure. Self-reported adherence did not predict outcomes. These results support the accuracy of the MEMS as a measure of medication-taking behavior and thus adherence.

The results of previous studies testing the predictors of outcomes of adherence in patients with HF have been inconsistent, most likely because of variability in measurement methods. In the current study, self-report medication adherence did not predict outcomes. Reasons for the difference are likely the lack of reliability of self-report measures5,16,41–43 Self-report measures are subject to recall bias and social desirability responses, which commonly lead to overestimation of actual adherence.32 In our study, there was a gap between the results of self-reported adherence and adherence measuring using the MEMS. We previously reported44 that HF patients could estimate their own medication adherence much better than they could estimate their adherence to the low sodium diet. The findings from the current study support these data in that most patients who self-report high adherence to medications were indeed adherent. However, an important percentage of patients who self-report high adherence have quite poor adherence rates; from 14% to 54% were adherent less than 80% of the time as assessed using the MEMS. Thus, although self-report is sensitive for detecting adherence, it is not sensitive for detecting nonadherence. Therefore, even though self-report medication adherence is simple, inexpensive, and feasible, and may provide a gross indicator of adherence,43 it should be interpreted with caution in clinical settings and future studies. The inability of self-reported adherence to predict outcomes is cause for concern because it is the method most commonly used by clinicians.

Of the four prior studies in which self-report measures of adherence were used, three reported a relationship between adherence and outcomes,45–47 whereas one found no relationship.48 In four studies with objective measures of adherence in patients with HF, pharmacy refill,49,50 MEMS,29 and serum digoxin levels,51 adherence predicted outcomes. Adherence was defined differently in each of these studies. Some investigators defined adherence as not missing any medications,45,47,48 whereas others also required patients to take their medications at the same time every day to be considered adherent.46 One group of investigators used the MEMS defined adherence as taking between 80% and 120% of prescribed doses.29 Another group of investigators defined patients as nonadherent if their serum digoxin level was zero (0 ng/mL) in at least 3 consecutive months. These different operational definitions of adherence make comparison difficult and suggest the importance of having a standard definition of adherence. A fruitful area for future investigation is defining what level of adherence is sufficient for achieving optimal patient outcomes.

Limitations

There are a number of potential limitations to the use of the MEMS to assess patient adherence. There is no guarantee that patients will take their medication even though they open the bottle or that they will take the correct dose, and in these situations, adherence level would be falsely elevated. Our data, however, demonstrating a strong relationship between adherence and outcomes, suggest that adherence was accurately reflected by the MEMS in this study. Moreover, data from validation studies of the MEMS in which serum medication blood levels were correlated with MEMS data demonstrate that when patients open the bottle to take medication, they do so.26,52

Conclusions

This study had three important findings: 1) Medication adherence is directly and independently related to important patient outcomes in HF; 2) the most important components of medication adherence are taking medications daily and taking the correct doses; and 3) self-reported adherence, at least when assessed using a simple one-item method, is not a reliable predictor of outcomes. The finding provides clinicians and researchers with valuable information on how to educate patients to improve medication adherence and thereby improve clinical outcomes in patients with HF. For example, clinicians should emphasize to patients the importance of taking the correct dose of medication every day when educating patients about medication adherence rather than emphasizing the timing of medication taking. On the basis of the results of this study and others, we recommend that clinicians do not use simple one-item self-report measures of adherence because they are not predictive of outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Medication adherence and time to first event of ED visits, rehospitalization, or mortality (dose-day).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the Philips Medical-American Association of Critical Care Nurses Outcomes Grant, the National Institute of Health Grant (R01 NR008567), the University of Kentucky General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02602), and the Gill Endowment, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing.

References

- 1.Stanley M, Prasun M. Heart failure in older adults: keys to successful management. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13:94–102. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200202000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleland JG, Clark A. Has the survival of the heart failure population changed? Lessons from trials. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:112D–9D. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)01011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rich MW, Gray DB, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Luther P. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on medication compliance in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 1996;101:270–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Col N, Fanale JE, Kronholm P. The role of medication noncompliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:841–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang LH. Medication-taking behavior of the elderly. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1996;12:423–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cline CM, Bjorck-Linne AK, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Erhardt LR. Non-compliance and knowledge of prescribed medication in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 1999;1:145–9. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez B, Lupon J, Parajon T, Urrutia A, Altimir S, Coll R, et al. Nurse evaluation of patients in a new multidisciplinary Heart Failure Unit in Spain. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blenkiron P. The elderly and their medication: understanding and compliance in a family practice. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:671–6. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.853.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers PT, Ruffin DM. Medication nonadherence: Part II–a pilot study in patients with congestive heart failure. Manag Care Interface. 1998;11:67–9. 75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonner CJ, Carr B. Medication compliance problems in general practice: detection and intervention by pharmacists and doctors. Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10:33–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhagat K, Mazayi-Mupanemunda M. Compliance with medication in patients with heart failure in Zimbabwe. East Afr Med J. 2001;78:45–8. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i1.9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohachick P, Burke LE, Sereika S, Murali S, Dunbar-Jacob J. Adherence to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy for heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graveley EA, Oseasohn CS. Multiple drug regimens: medication compliance among veterans 65 years and older. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14:51–8. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Noncompliance with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:433–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artinian NT, Harden JK, Kronenberg MW, Vander Wal JS, Daher E, Stephens Q, et al. Pilot study of a Web-based compliance monitoring device for patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32:226–33. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(03)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evangelista LS, Berg J, Dracup K. Relationship between psychosocial variables and compliance in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001;30:294–301. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.116011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer JA. Microelectronic systems for monitoring and enhancing patient compliance with medication regimens. Drugs. 1995;49:321–7. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199549030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordciro-Breault M, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37:846–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA. 1989;261:3273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M, Waeber B, Kappenberger L, Burnand B, et al. Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39:402–9. doi: 10.1177/00912709922007976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wetzels GE, Nelemans P, Schouten JS, Prins MH. Facts and fiction of poor compliance as a cause of inadequate blood pressure control: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1849–55. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1074–90. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5. discussion 1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GL, Masoudi FA, Vaccarino V, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: mortality, readmission, and functional decline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1510–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng CW, Woo KS, Chan JC, Tomlinson B, You JH. Association between adherence to statin therapy and lipid control in Hong Kong Chinese patients at high risk of coronary heart disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:528–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobbels F, De Geest S, van Cleemput J, Droogne W, Vanhaecke J. Effect of late medication non-compliance on outcome after heart transplantation: a 5-year follow-up. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:1245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunbar-Jacob J, Bohachick P, Mortimer MK, Sereika SM, Foley SM. Medication adherence in persons with cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18:209–18. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hope CJ, Wu J, Tu W, Young J, Murray MD. Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:2043–9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.19.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Eisen SA, Rich MW, Jaffe AS. Major depression and medication adherence in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Health Psychol. 1995;14:88–90. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW, Leufkens HG. Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study. J Card Fail. 2003;9:404–11. doi: 10.1054/s1071-9164(03)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wutoh AK, Elekwachi O, Clarke-Tasker V, Daftary M, Powell NJ, Campusano G. Assessment and predictors of antiretroviral adherence in older HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S106–14. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, Kravitz RL, McGlynn EA, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RL. Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. J Behav Med. 1992;15:447–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00844941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Mazel RM, Sherbourne CD, DiMatteo MR, Rogers WH, et al. The impact of patient adherence on health outcomes for patients with chronic disease in the Medical Outcomes Study. J Behav Med. 1994;17:347–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01858007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hershberger RE, Ni H, Nauman DJ, Burgess D, Toy W, Wise K, et al. Prospective evaluation of an outpatient heart failure management program. J Card Fail. 2001;7:64–74. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.21677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser DK, Stevenson WG, Woo MA, Stevenson LW. Timing of sudden death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:963–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90856-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chui MA, Deer M, Bennett SJ, Tu W, Oury S, Brater DC, et al. Association between adherence to diuretic therapy and health care utilization in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:326–32. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.3.326.32112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopjar B, Sales AE, Pineros SL, Sun H, Li YF, Hedeen AN. Adherence with statin therapy in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in veterans administration male population. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1106–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosen MI, Rigsby MO, Salahi JT, Ryan CE, Cramer JA. Electronic monitoring and counseling to improve medication adherence. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:409–22. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evangelista L, Doering LV, Dracup K, Westlake C, Hamilton M, Fonarow GC. Compliance behaviors of elderly patients with advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18:197–206. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200307000-00005. quiz 207–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson MJ. The medication-taking questionnaire for measuring patterned behavior adherence. Commun Nurs Res. 2002;35:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung M, De Jong M, Wu J, Lennie T, Riegel B, Moser D. Patients Differ in Their Ability to Self-Monitor Adherence to Low Sodium Diet vs. Medication. J Card Fail. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.010. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chin MH, Goldman L. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:643–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Morrow-Howell N, Proctor EK. Post-acute home care and hospital readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Health Soc Work. 2004;29:275–85. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ryan P, Willson K, Yelland L. Self-reported adherence with medication and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2) Med J Aust. 2006;185:487–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross SE, Moore LA, Earnest MA, Wittevrongel L, Lin CT. Providing a web-based online medical record with electronic communication capabilities to patients with congestive heart failure: randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e12. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.2.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cole JA, Norman H, Weatherby LB, Walker AM. Drug copayment and adherence in chronic heart failure: effect on cost and outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1157–64. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.8.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miura T, Kojima R, Mizutani M, Shiga Y, Takatsu F, Suzuki Y. Effect of digoxin noncompliance on hospitalization and mortality in patients with heart failure in long-term therapy: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:77–83. doi: 10.1007/s002280100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamilton GA. Measuring adherence in a hypertension clinical trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:219–28. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]