Abstract

Since the discovery of the importance of the hippocampus for normal memory, considerable research has endeavored to characterize the precise role played by the hippocampus. Previously we have offered the relational memory theory, which posits that the hippocampus forms representations of arbitrary or accidentally occurring relations among the constituent elements of experience. In a recent report we emphasized the role of the hippocampus in all manner of relations, supporting this claim with the finding that amnesic patients with hippocampal damage were similarly impaired on probes of memory for spatial, sequential, and associative relations. In this review we place these results in the context of the broader literature, including how different kinds of relational or source information are tested, and consider the importance of specifying hippocampal function in terms of the representations it supports.

Keywords: hippocampus, relational memory, memory representations, amnesia

Characterizing the Functional Role of the Hippocampus

That the hippocampus plays a critical role in memory has been clear since the documenting of severe amnesia following temporal lobe resection in patient H.M. (Scoville and Milner, 1957). Since that time, an extraordinary amount of research has been directed at characterizing the functional role the hippocampus plays in memory, leading various authors to emphasize, among other things, spatial memory or cognitive mapping (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978), declarative memory (Cohen, 1984; Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993; Squire et al., 2004), explicit memory (Graf and Schacter, 1985), recollection (Aggleton and Brown, 2006; Ranganath et al., 2004), and relational memory (Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993; Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001). Our own work has focused on the profound deficits observed on tests of relational memory in amnesia consequent to hippocampal damage (Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993; Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001; Hannula et al., 2006, 2007; Konkel et al., 2008; Ryan and Cohen, 2003; Ryan et al., 2000).

The Hippocampus and all Manner of Relational Memory

In a recent paper (Konkel et al., 2008) we tested the idea that the hippocampus is critical in memory for all manner of relations among the perceptually distinct elements of experience, providing evidence for this claim in the finding that hippocampal amnesia was associated with deficits in memory for spatial, sequence (temporal), and associative (co-occurrence) relations among items. This finding is noteworthy because prior studies of hippocampal-dependent memory have tended either to examine memory for only a single type of relation or conflated multiple kinds of relations. Only by employing a procedure in which each of several kinds of relational memory could be tested separately, using the same materials, were we able to examine fairly whether the hippocampal role extended to all types of relations or whether instead some types are special.

Are some types of relational memory special?

In contrast to a view emphasizing all manner of relations, some “limited-domain accounts” (see Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993) have focused exclusively or primarily on one or another particular type of relations. Perhaps the best example is the spatial memory or cognitive mapping theory of hippocampus (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978), based initially on the discovery in the hippocampus of what were called place cells (cells that fire preferentially when the animal is in one or another particular location) (O'Keefe and Dostrovsky, 1971). Many studies have gone on to report spatial correlates of hippocampal activity or hippocampal dependence of spatial memory performance, based on allocentric spatial relations, not only in animals but also in humans (see Bird and Burgess, 2008; Table 1). But both the animal and human literatures are now filled with numerous findings from other studies documenting hippocampal involvement in relational tasks with no critical spatial component (see Cohen et al., 1999; Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001; Table 1), making it difficult to reconcile a solely spatial account of hippocampal function. This also applies to other limited-domain accounts; any evidence that supports a given limited account (e.g. spatial maps) contradicts a different limited account (e.g. associative memory) while evidence for the latter similarly contradicts the former.

Table 1.

A selection of neuroimaging and MTL lesion studies that tested memory for associations, spatial locations, sequences, or some combination thereof. For neuroimaging studies, the result column lists the active MTL regions for the listed contrast (or reduction in activity as noted).

| Study | Materials | Lesion/Neuroimaging | Analysis | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Task Only | ||||||||

| Bayley and Squire (2005) | Apartment layout | Lesion | No comparison group used | Patients impaired | ||||

| Cansino et al. (2002) | Pictures of common objects in an array | fMRI | SM: SC > SI | No MTL activity | ||||

| Cansino et al. (2002) | Pictures of common objects in an array | fMRI | Ret: SC > SI | H,Ph | ||||

| Crane and Milner (2005) expt. 1 | Physical toys placed in an array | Lesion | Trials to criterion | Patients impaired | ||||

| Crane and Milner (2005) expt. 2 | Physical toys placed in an array | Lesion | Trials to criterion, placement accuracy | Patients impaired | ||||

| Hannula and Ranganath (2008) | 3D pictures rendered in an array | fMRI | C > I for each phase of WM task | H, Pr at sample and probe phase | ||||

| Hannula and Ranganath (2008) | 3D pictures rendered in an array | fMRI | Matching > mismatching > incorrect for each phase of WM task | H at probe phase | ||||

| Hartley et al. (2003) | Virtual environment | fMRI | Searching > route following | H | ||||

| Maguire et al. (2006) | Virtual recreation of London | Lesion | Navigation efficiency | Patient impaired on some routes | ||||

| Pine et al. (2002) | Virtual environment | fMRI | Searching > route following | H | ||||

| Ryan et al. (2000) | Scenes | Lesion | Relational eye-movement effect | Patients impaired | ||||

| Spiers and Maguire (2006) | Virtual recreation of London | fMRI | fMRI activity collected during navigation | H | ||||

| Associative Task Only | ||||||||

| Davachi et al. (2003) | Words | fMRI | SM: SC > SI | H,Ph | ||||

| Davachi and Wagner (2002) | Word triplets | fMRI | Enc: relational > item processing | H | ||||

| Davachi and Wagner (2002) | Word triplets | fMRI | SM: 3 words from triplet > 1 or 2 | H in relational but not item condition | ||||

| Giovanello et al. (2004) | Word pairs | fMRI | Ret: associative > item pair | H | ||||

| Giovanello et al. (2003) | Word pairs | Lesion | Associative, item pair, or single item recognition | Patients impaired on associative test | ||||

| Graf and Schacter (1985) | Word pairs | Lesion | Stem completion and cued recall | Patients impaired on cued recall | ||||

| Hannula et al. (2007) | Face-scene pairs | Lesion | Associative recognition and relational eye movement effect | Patients impaired | ||||

| Haskins et al. (2008) | Word pairs | fMRI | SM: increasing familiarity in unitization or associative condition | Pr | ||||

| Henke et al. (1997) | Face-scene pairs | PET | Enc: associative or item encoding | H,Ph | ||||

| Henke et al. (2003) | Face-profession pairs | fMRI | Enc: faces and profession > face alone | H (reduction) | ||||

| Henke et al. (2003) | Face-profession pairs | fMRI | Ret: face and profession block > face only block (associative test for both) | H,Pr | ||||

| Prince et al. (2005) | Word pairs and word-font pairs | fMRI | Associative hit > miss at encoding and retrieval | H | ||||

| Ranganath et al. (2004) | Words presented in one of two colors | fMRI | SM: SC > SI | H,Ph | ||||

| Associative Task Only | ||||||||

| Ranganath et al. (2004) | Words presented in one of two colors | fMRI | SM: increasing item familiarity | Pr | ||||

| Staresina and Davachi (2006) | Words presented with colored backgrounds | fMRI | SM: recalled words > SC > SI | H | ||||

| Staresina and Davachi (2006) | Words presented with colored backgrounds | fMRI | SM: SC > SI for recall and recognition | Pr | ||||

| Turriziani et al. (2004) | Male and female faces and professions | Lesion | Single face, face-face, and face-profession recognition | Patients equally impaired at associations | ||||

| Sequence Task Only | ||||||||

| Kumaran and Maguire (2006) | Pictures of objects arranged in quartets | fMRI | Half-repeated sequence > repeat or scrambled sequences | H | ||||

| Kumaran and Maguire (2006) | Pictures of objects arranged in quartets | fMRI | Half repeated or scrambled sequences > repeated sequences | Pr | ||||

| Schendan et al. (2003) | Numbers indicating which of four buttons to press | fMRI | Embedded sequence > random sequence block | H | ||||

| Multiple Tasks | ||||||||

| Hannula et al. (2006) expt. 1 | Objects within a scene | Lesion | Continuous recognition for scenes, detecting objects shifted within a scene | Patients impaired at detecting shifts | ||||

| Hannula et al. (2006) expt. 2 | Face-scene pairs | Lesion | Associative recognition | Patients impaired | ||||

| Holdstock et al. (2005) | Various | Lesion | Variety of yes/no, AFC, and recall item, spatial, and sequence tasks | Patient is impaired at all recall tasks, spatial and sequence tasks, and some item recognition tasks | ||||

| Holdstock et al. (2002) | Various | Lesion | Variety of yes/no, AFC, and recall item and spatial tasks | Patient is impaired at all recall tasks, spatial tasks, and yes-no recognition | ||||

| Kohler et al. (2005) expt. 1 | Pairs of line drawings in an array | fMRI | Ret: swapped locations or rearranged pairs > repeated pairs | H | ||||

| Kohler et al. (2005) expt. 2 | Line drawings | Intentional encoding | Ret: new items > old items | Pr | ||||

| Kroll et al. (1996) expt. 1 | Two-syllable words | Lesion | Continuous recognition of new words, words made of repaired syllables, or words with one previously seen syllable | Left-hemisphere lesion patients impaired | ||||

| Kroll et al. (1996) expt. 2 | Various kinds of drawings of faces | Lesion | Recognition of repeated faces or faces with repaired features | Patients impaired | ||||

| Kumaran and Maguire (2005) | Spatially and socially arranged networks of friends | fMRI | Mentally traveling through a social or spatial network or making judgments about friends’ faces or homes | Hippocampal activity was only above baseline in the spatial network condition | ||||

| Mayes et al. (2004) | Various | Lesion | Variety of item recognition, within-domain (e.g. face-face) and between-domain (e.g. face-word) associative recognition, spatial, and sequence tests | Patient is impaired on between-domain associative, spatial, and sequence recognition | ||||

| Multiple Tasks | ||||||||

| Olson et al. (2006) | Line drawings in an array | Lesion | Working memory task for items, occupied locations, or the conjunction of the two | Patients were impaired at the conjunction | ||||

| Pihlajamaki et al. (2004) | Line drawings in an array | fMRI | New object in array > baseline repeated array | H, Ph, Pr | ||||

| Pihlajamaki et al. (2004) | Line drawings in an array | fMRI | Items shifted locations in array > baseline repeated array | H, Ph | ||||

| Ryan et al. (2009) | Pictures in an array | fMRI | Ret: judging which of two pictures was to the right of the other or more realistic; which of two objects is typically above the other or more expensive, or which of two unstudied pictures is typically in front of the other or is softer | Hippocampal activity was above baseline in every condition; it was highest in the spatial conditions | ||||

| Multiple Tasks within Paradigm within Participants | ||||||||

| Konkel et al. (2008) | Triplets of computer-generated patterns | Lesion | Item, associative, spatial, and sequence tests | Patients impaired at sequence, associative, and spatial tasks | ||||

| Staresina and Davachi (2008) | Words presented on one of four colored backgrounds | fMRI | SM: correct color or correct color and task > item only or correct task | Pr | ||||

| Staresina and Davachi (2008) | Words presented on one of four colored backgrounds | fMRI | SM: both color and task correct > color or task correct > item only | H | ||||

| Uncapher et al. (2006) | Words in one of four font colors in an array | Participants made a living/non-living judgment on each word | SM: both color and location correct > color or location correct | H | ||||

| Uncapher et al. (2006) | Words in one of four font colors in an array | Participants made a living/non-living judgment on each word | SM: both color and location correct = color or location correct = item only correct | Pr | ||||

SM, subsequent memory; SC, source correct; SI, source incorrect; Ret, retrieval time; Enc, encoding time; H, hippocampus; Ph, parahippocampus; Pr, perirhinal cortex; C, correct; I, incorrect; WM, working memory.

More modern variants have shifted the debate to whether one particular type of relation is “special” or critical in hippocampal function. For the spatial mapping hypothesis, for example, Bird and Burgess (2008) have suggested that spatial maps represented in the hippocampus allow for the construction/reconstruction of mental images which, the authors believe, mediate episodic recollection. It is extraordinarily difficult to assess whether spatial or some other type of representation is somehow more fundamental, providing the basis for gaining access to the full range of relational information for which the hippocampus is involved. But it is entirely feasible to assess whether there are any functional implications of the “specialness” hypothesis, i.e., any differences manifested in the relationship of hippocampus to performance. That is, moving beyond the question of whether the hippocampus is engaged by and critical for all manner of relations, we can ask whether memory for one or another type of relations is disproportionately dependent on the hippocampus, and whether memory for various relations is statistically dependent on any particular type of relational memory.

Testing multiple relations or multiple sources of information about items

Critical tests and advancement of theories in this area require assessing multiple kinds of relations, or multiple sources of information about the to-be-remembered items (or source memory), in order to determine whether there are meaningful distinctions to be drawn among them. The most powerful way to test this is through comparison of multiple types of relations within a single paradigm for the same participants. But this criterion has rarely been met. A small number of studies (see Table 1) have tested multiple types of relational memory in either the same paradigm or the same subjects. Some fMRI studies have expressly attempted to compare spatial memory to other types of relations. While some (e.g. Kumaran and Maguire, 2005; Ryan et al., 2009) have found more hippocampal activity in the spatial than other putatively relational conditions, others (e.g. Kohler et al., 2005; Uncapher et al., 2006) have not.

But, critically, of all the studies attempting direct comparisons, only those by Staresina and Davachi (2008), Uncapher et al. (2006), and Konkel et al. (2008) compared more than one type of relational memory or association to memory for the items themselves within the same paradigm and subjects. Staresina and Davachi (2008) showed participants nouns on a colored background and asked them to make a mental image of the object in that color and make one of two different judgments about the image while fMRI activity was recorded. At test, participants made an old/new item judgment followed by forced-choice decisions about the color in which the item was presented and the type of judgment they made at the time they generated an image. Findings showed that the hippocampus exhibited little activity when only the item was remembered, more activity when in addition the color or task judgment was remembered, and the most activity when both color and task judgments were remembered for the item. By contrast, the perirhinal cortex, thought to be involved in memory for items and for intra-item binding (binding within items), showed activity both for trials when the item alone was later correctly remembered and when the item and color were later correctly remembered. Also using a subsequent memory analysis with yes/no item recognition and forced-choice source judgments, Uncapher et al. (2006) had participants make a living/non-living judgment on words in one of four colors located in one of four quadrants on the screen. They found that the hippocampus was more active when both sources were later remembered than if only one were remembered, whereas the perirhinal cortex was equally active regardless of whether any source was remembered so long as the item was correctly remembered. Konkel et al. (2008) tested the necessity of the hippocampus for a variety of relations by showing patients with hippocampal amnesia triplets of computer-generated patterns presented sequentially in one of three screen locations. After each study block, participants were tested either on the spatial locations of a triplet, the temporal sequence of a triplet, or the co-occurrence of items in a triplet (associative memory), each tested in a manner independent of the other forms of relational information, and were tested for memory of the items themselves. We found that patients with damage limited primarily to the hippocampus showed disproportionately impaired memory for each kind of relation, compared to that of comparison participants, despite relatively intact item memory. Patients with more extensive damage, extending into MTL cortical regions, performed at floor levels on the item task as well. Moreover, correlational analyses performed on the various relational memory performances of comparison participants showed statistical interdependencies, with no special dependency on any particular type of relation. Thus, in none of these studies was there evidence for any particular type of relation being “special”.

Hippocampus and Representation

Some accounts of the hippocampus have emphasized the nature of the processing it supports in the act of remembering, such as recollection (Aggleton and Brown, 2006; Ranganath et al., 2004; see reviews by Diana et al., 2007; Eichenbaum et al., 2007); this focus is particularly apparent in the neuroimaging literature, where the ability to image active processes in the brain may encourage such an approach. Our own work has instead focused on the representations of experience that the hippocampus supports. Our earliest proposals about declarative memory (Cohen, 1984; Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993) emphasized the storage of the outcomes of processing, representing facts and events in highly linked, flexible networks. Our subsequent proposals, describing relational memory theory, characterized declarative memory as being fundamentally relational, representing all the various arbitrary or accidentally occurring relations among the (perceptually distinct) constituent elements of experience, again in highly flexible networks (Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1993; Cohen et al., 1997; Eichenbaum and Cohen, 2001; Ryan and Cohen, 2003). The long-lived appeal of the spatial memory/cognitive mapping theory of hippocampus (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978) may be the clarity of its proposal about hippocampal representation – it is an allocentric map of the environment, representing the relations among the various stimuli in the environment, with flexible navigable links among the elements in the map (see Bird and Burgess, 2008 for an up-to-date version).

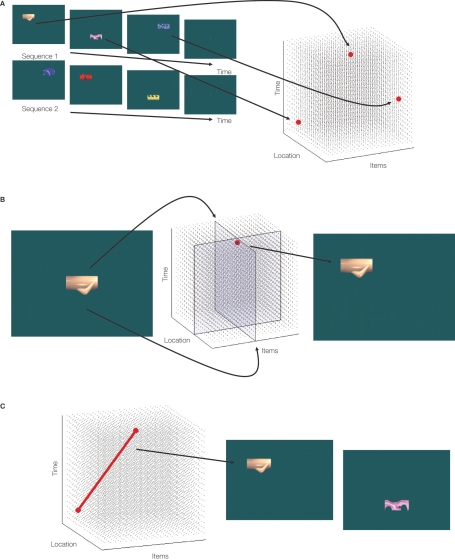

In our view the hippocampus represents experience as nodes within a multi-dimensional representation space (also see Eichenbaum, 2004), with each axis or dimension representing a different domain of information (not just x,y space, or just space and time). Various relations among items (spatial, sequential/temporal, etc.) are captured within the n-dimensional space. Information from the various processing streams arrives via inputs from earlier cortical areas (such as perirhinal and parahippocampal cortex), activating relevant nodes within the representational space (shown as several distinct representation planes in Figure 1). Inputs to the hippocampus also cause reactivation of related information via relational links with associated nodes. To the extent that the model is reflective of physiology, “place cell” activity can be understood as reflecting a subset of the more general, relational memory space where the critical dimensions are the axes of space. Not only are the “places” to which hippocampal neurons preferentially fire represented relationally, but when tested under circumstances that emphasize things other than spatial navigation these neurons represent other types of relations. Thus the nodes that were thought to reflect spatial memory under one testing condition can reflect various types and combinations of relational information, including expressly non-spatial relations, reflecting the different aspects of the n-dimensional space. This view was captured by Eichenbaum and Cohen (1988) in their suggestion that these hippocampal neurons should be called “relational cells” rather than the narrower construal of place cells. This framework offers an account of why patients with hippocampal amnesia still have access to the products of sensory processing, and exhibit memory for and priming of individual items, but are unable to place these products in the multi-dimensional space that allows the items to be relationally bound to one another and flexibly connected to previously existing memories. And, critically, it explains why their relational memory is impaired for all manner of relations without any “special” deficit for any particular kind of relation.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the putative hippocampal representation. (A) At encoding (illustrated with stimuli from Konkel et al., 2008), items are encoded into a multi-dimensional representational space according to aspects such as time and location, thereby capturing all the various types of relations among items. (B) When relational or source memory is tested via recognition (e.g., where was this item studied?), the item together with the source probe constrains or limits the space to be searched, aiding retrieval of the relevant information (i.e., activation of the relevant node). (C) Activation of a given node in the space may also lead to reactivation of related nodes (here, retrieving the next item and location in the sequence).

Future Directions

Many other important issues about memory and the MTL, not covered by this review, warrant further research. One important issue is the potential division of labor in memory within the MTL (see Aggleton and Brown, 2006; Davachi, 2006; Diana et al., 2007; Eichenbaum et al., 2007; Mayes et al., 2007; Squire et al., 2004). There is considerable empirical support for differential functions of the hippocampus versus surrounding MTL cortices, for relational memory versus item memory respectively, but their exact roles and their interactions remain underspecified. Another important issue that complicates work in this area concerns the definition of “items” as opposed to “relations” or “sources”. For example, the same stimulus information could be seen as the item or as the context depending on instructions and allocation of attention (see Diana et al., 2007). Moreover, two portions of the sensory array might be considered part of the same one object or as part of multiple separate objects. We (Cohen et al., 1997; Eichenbaum et al., 1994) and others (Diana et al., 2007; Mayes et al., 2007; Moses and Ryan, 2006) have noted that multiple sensory features can be fused, blended, configured, or unitized into a single item representation by structures outside of the hippocampus, such as the MTL cortices, obviating the need for hippocampal-dependent relational memory. However, it is difficult to know a priori when fused or unitized representations might be in play, although such representations are thought to be less flexible than relational representations (Cohen et al., 1997; Eichenbaum et al., 1994; Haskins et al., 2008). It will be critical to develop methods for acquiring independent evidence of such representations in action. Finally, hippocampal representations themselves require further exploration: Are the various dimensions in the hippocampal representation independent, or do they covary? What determines the strengths of various links in the multi-dimensional space? These and other questions will keep memory research focused on the hippocampus for years to come.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the work was carried out in the absence of any financial relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Amnesia Research Laboratory and the Gonsalves Group for helpful discussions, and the reviewers of a previous version of this paper for their helpful suggestions. This work was supported by NIMH grant MH062500 to NJC. We also thank Brian Levinthal for assistance with creation of the figure.

Key Concept

- Declarative memory

Memory for facts and events, to be contrasted with procedural memory, which supports the ability to acquire and express skills (or the difference between “knowing that” and “knowing how”). The nature of declarative representations, thought to be fundamentally relational and flexible, makes it possible for such memory to be consciously accessed and “declared”.

- Explicit memory

A kind of memory based on explicit remembering or conscious recollection of some prior learning episode, or the kind of memory test that requires explicit remembering; usually defined in contrast to implicit memory, involving the ability of behavior to be influenced by previous experience without requiring the individual to consciously recollect the prior experience.

- Recollection

A process that results in the retrieval of additional information about a particular item from memory beyond its oldness; this information could be some detail of the study experience such as the color of the font of the item or its location on the screen, or some internal state at study time, such as what the item reminded you of.

- Relational memory

Memory for relations among the constituent elements of experience, providing the ability to remember names with faces, the locations of various objects or people, or the order in which various events occurred. Can be contrasted to item memory, i.e., of the individual elements themselves. The hippocampus is required for memory for arbitrary or accidentally occurring relations.

- Place cells

When an animal is exploring its environment, principal neurons of the hippocampus fire preferentially in particular regions of the environment corresponding to the neurons’ “place fields”; in this way, a set of such neurons can represent the entire environment. The “places” are represented relationally, in terms of the relations among elements in the environment.

- Source memory

Memory for information about an item beyond the item itself; i.e., its various relations to other elements of the event. In laboratory experiments, this usually refers to the particular location of an item on the computer screen, the color of the font or format in which the item is displayed, or the voice or identity associated with some piece of presented information.

- Unitization

The fusing, blending, or configuring of multiple aspects of a sensory array into a single-item representation; thought to be accomplished by cortical regions outside of the hippocampus [such as in the fusiform face area (FFA) for faces, and the perirhinal cortex for some complex objects], and less flexible and less relational than hippocampal representations of multiple objects.

Biography

Alex Konkel received a B.Sc. in Physics from Washington University in St. Louis where he also worked with Larry Jacoby and Randy Buckner. He received a M.A. in psychology and is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with Neal J. Cohen. His interests include the neural correlates of memory, distinctions in types of memory, such as source memory or recollection and familiarity, and metamemory.

Alex Konkel received a B.Sc. in Physics from Washington University in St. Louis where he also worked with Larry Jacoby and Randy Buckner. He received a M.A. in psychology and is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with Neal J. Cohen. His interests include the neural correlates of memory, distinctions in types of memory, such as source memory or recollection and familiarity, and metamemory.

References

- Aggleton J. P., Brown M. W. (2006). Interleaving brain systems for episodic and recognition memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 455–463 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley P. J., Squire L. R. (2005). Failure to acquire new semantic knowledge in patients with large medial temporal lobe lesions. Hippocampus 15, 273–280 10.1002/hipo.20057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird C. M., Burgess N. (2008). The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 182–194 10.1038/nrn2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino S., Maquet P., Dolan R. J., Rugg M. D. (2002). Brain activity underlying encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cereb. Cortex 12, 1048–1056 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N. J. (1984). Preserved learning capacity in amnesia: evidence for multiple memory systems. In Neuropsychology of Memory, Squire L. R., Butters N., eds (New York, Guilford Press; ), pp. 83–103 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N. J., Eichenbaum H. (1993). Memory, Amnesia, and The Hippocampal System. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N. J., Poldrack R. A., Eichenbaum H. (1997). Memory for items and memory for relations in the procedural/declarative memory framework. Memory 5, 131–178 10.1080/741941149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N. J., Ryan J., Hunt C., Romine L., Wszalek T., Nash C. (1999). Hippocampal system and declarative (relational) memory: summarizing the data from functional neuroimaging studies. Hippocampus 9, 83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J., Milner B. (2005). What went where? Impaired object-location learning in patients with right hippocampal lesions. Hippocampus 15, 216–231 10.1002/hipo.20043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. (2006). Item, context, and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 693–700 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L., Mitchell J. P., Wagner A. D. (2003). Multiple routes to memory: distinct medial temporal lobe processes build item and source memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2157–2162 10.1073/pnas.0337195100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L., Wagner A. D. (2002). Hippocampal contributions to episodic encoding: insights from relational and item-based learning. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 982–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana R. A., Yonelinas A. P., Ranganath C. (2007). Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: a three component model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 379–386 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. (2004). Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron 44, 109–120 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H., Cohen N. J. (1988). Representation in the hippocampus: what do the neurons code? Trends Neurosci. 11, 244–248 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90100-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H., Cohen N. J. (2001). From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. New York, Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H., Otto T., Cohen N. J. (1994). Two functional components of the hippocampal memory system. Behav. Brain Sci. 17, 449–517 [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H., Yonelinas A. P., Ranganath C. (2007). The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 123–152 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanello K. S., Schnyer D. M., Verfaellie M. (2004). A critical role for the anterior hippocampus in relational memory: evidence from an fMRI study comparing associative and item recognition. Hippocampus 14, 5–8 10.1002/hipo.10182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanello K. S., Verfaellie M., Keane M. M. (2003). Disproportionate deficit in associative recognition relative to item recognition in global amnesia. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 3, 186–194 10.3758/CABN.3.3.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf P., Schacter D. J. (1985). Implicit and explicit memory for new associations in normal and amnesic patients. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 11, 501–518 10.1037/0278-7393.11.3.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula D. E., Ranganath C. (2008). Medial temporal lobe activity predicts successful relational memory binding. J. Neurosci. 28, 116–124 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3086-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula D. E., Ryan J. D., Tranel D., Cohen N. J. (2007). Rapid onset relational memory effects are evident in eye movement behavior, but not in hippocampal amnesia. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 19, 1690–1705 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula D. E., Tranel D., Cohen N. J. (2006). The long and the short of it: relational memory impairments in amnesia, even at short lags. J. Neurosci. 26, 8352–8359 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5222-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T., Maguire E. A., Spiers H. J., Burgess N. (2003). The well-worn route and the path less traveled: distinct neural bases of route following and wayfinding in humans. Neuron 37, 877–888 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00095-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins A. L., Yonelinas A. P., Quamme J. R., Ranganath C. (2008). Perirhinal cortex supports encoding and familiarity-based recognition of novel associations. Neuron 59, 554–560 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke K., Buck A., Weber B., Wieser H. G. (1997). Human hippocampus establishes associations in memory. Hippocampus 7, 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke K., Mondadori C. R. A., Treyer V., Nitsch R. M., Buck A., Hock C. (2003). Nonconscious formation and reactivation of semantic associations by way of the medial temporal lobe. Neuropsychologia 41, 863–876 10.1016/S0028-3932(03)00035-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock J. S., Mayes A. R., Gong Q. Y., Roberts N., Kapur N. (2005). Item recognition is less impaired than recall and associative recognition in a patient with selective hippocampal damage. Hippocampus 15, 203–215 10.1002/hipo.20046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock J. S., Mayes A. R., Roberts N., Cezayirli E., Isaac C. L., O'Reilly R. C., Norman K. A. (2002). Under what conditions is recognition spared relative to recall after selective hippocampal damage in humans? Hippocampus 12, 341–351 10.1002/hipo.10011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler S., Danckert S., Gati J. S., Menon R. S. (2005). Novelty responses to relational and non-relational information in the hippocampus and parahippocampal region: a comparison based on event-related fMRI. Hippocampus 15, 763–774 10.1002/hipo.20098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel A., Warren D. E., Duff M. C., Tranel D., Cohen N. J. (2008). Hippocampal amnesia impairs all manner of relational memory. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2, 15. 10.3389/neuro.09.015.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll N. E. A., Knight R. T., Metcalfe J., Wolf E. S., Tulving E. (1996). Cohesion failure as a source of memory illusions. J. Mem. Lang. 35, 176–196 10.1006/jmla.1996.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D., Maguire E. A. (2005). The human hippocampus: cognitive maps or relational memory? J. Neurosci. 25, 7254–7259 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1103-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D., Maguire E. A. (2006). An unexpected sequence of events: mismatch detection in the human hippocampus. PLoS Biol. 4, 2372–2382 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire E. A., Nannery R., Spiers H. J. (2006). Navigation around London by a taxi driver with bilateral hippocampal lesions. Brain 129, 2894–2907 10.1093/brain/awl286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes A. R., Holdstock J. S., Isaac C. L., Montaldi D., Grigor J., Gummer A., Cariga P., Downes J. J., Tsivilis D., Gaffan D., Gong Q., Norman K. A. (2004). Associative recognition in a patient with selective hippocampal lesions and relatively normal item recognition. Hippocampus 14, 763–784 10.1002/hipo.10211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes A. R., Montaldi D., Migo E. (2007). Associative memory and the medial temporal lobes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 126–135 10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses S. N., Ryan J. D. (2006). A comparison and evaluation of the predictions of relational and conjunctive accounts of hippocampal function. Hippocampus 16, 43–65 10.1002/hipo.20131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J., Dostrovsky J. (1971). The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 34, 171–175 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J. A., Nadel L. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. London, Oxford, Clarendon Press [Google Scholar]

- Olson I. R., Page K., Moore K. S., Chatterjee A., Verfaellie M. (2006). Working memory for conjunctions relies on the medial temporal lobe. J. Neurosci. 26, 4596–4601 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1923-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamaki M., Tanila H., Kononen M., Hanninen T., Hamalainen A., Soininen H., Aronen H. J. (2004). Visual presentation of novel objects and new spatial arrangements of objects differentially activates the medial temporal lobe subareas in humans. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1939–1949 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine D. S., Grun J., Maguire E. A., Burgess N., Zarahn E., Koda V., Fyer A., Szeszko P. R., Bilder R. M. (2002). Neurodevelopmental aspects of spatial navigation: a virtual reality fMRI study. NeuroImage 15, 396–406 10.1006/nimg.2001.0988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince S. E., Daselaar S. M., Cabeza R. (2005). Neural correlates of relational memory: successful encoding and retrieval of semantic and perceptual associations. J. Neurosci. 25, 1203–1210 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2540-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C., Yonelinas A. P., Cohen M. X., Dy C. J., Tom S. M., D'Esposito M. (2004). Dissociable correlates of recollection and familiarity within the medial temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia 42, 2–13 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J. D., Althoff R. R., Whitlow S., Cohen N. J. (2000). Amnesia is a deficit in relational memory. Psychol. Sci. 11, 454–461 10.1111/1467-9280.00288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J. D., Cohen N. J. (2003). Evaluating the neuropsychological dissociation evidence for multiple memory systems. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 3, 168–185 10.3758/CABN.3.3.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L., Lin C., Ketcham K., Nadel L. (2009). The role of medial temporal lobe in retrieving spatial and nonspatial relations from episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus, in press. 10.1002/hipo.20607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendan H. E., Searl M. M., Melrose R. J., Stern C. E. (2003). An fMRI study of the role of medial temporal lobe in implicit and explicit sequence learning. Neuron 37, 1013–1025 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00123-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville W. B., Milner B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 20, 11–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers H. J., Maguire E. A. (2006). Thoughts, behaviour, and brain dynamics during navigation in the real world. NeuroImage 31, 1826–1840 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire L. R., Stark C. E. L., Clark R. E. (2004). The medial temporal lobe. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 279–306 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina B. P., Davachi L. (2006). Differential encoding mechanisms for subsequent associative recognition and free recall. J. Neurosci. 26, 9162–9172 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina B. P., Davachi L. (2008). Selective and shared contributions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex to episodic item and associative encoding. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 1478–1489 10.1162/jocn.2008.20104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turriziani P., Fadda L., Caltigirone C., Carlesimo G. A. (2004). Recognition memory for single items and associations in amnesic patients. Neuropsychologia 42, 426–434 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uncapher M. R., Otten L. J., Rugg M. D. (2006). Episodic encoding is more than the sum of its parts: an fMRI investigation of multifeatural contextual encoding. Neuron 52, 547–556 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]