Abstract

In many plant species only a small proportion of buds yield branches. Both the timing and extent of bud activation are tightly regulated to produce specific branching architectures. For example, the primary shoot apex can inhibit the activation of lateral buds. This process is termed apical dominance and is dependent on the plant hormone auxin moving down the main stem in the polar auxin transport stream. We use a computational model and mathematical analysis to show that apical dominance can be explained in terms of an auxin transport switch established by the temporal precedence between competing auxin sources. Our model suggests a mechanistic basis for the indirect action of auxin in bud inhibition and captures the effects of diverse genetic and physiological manipulations. In particular, the model explains the surprising observation that highly branched Arabidopsis phenotypes can exhibit either high or low auxin transport.

Keywords: auxin transport canalization, dynamic system, MAX, shoot branching, simulation model

The plant shoot system is generated from the primary shoot apical meristem, which is established during embryogenesis. After germination, the meristem produces a series of metamers consisting of a stem segment, a leaf, and a new meristem in the leaf axil. Each axillary meristem has the same developmental potential as the primary shoot apical meristem in that it can produce a growing shoot axis. However, axillary meristems frequently enter a dormant state after forming only a few leaves. These dormant buds may subsequently be reactivated by various internal and external factors, contributing to the enormous diversity of plant architectures in nature and to plastic responses of plants to their environment.

An important factor regulating bud activity is the inhibition of axillary buds by the primary shoot apex. This phenomenon is called apical dominance and is familiar to gardeners, who prune away the leading shoot of plants to encourage branching. In the 1930s, the phytohormone auxin was identified as a central regulator of apical dominance (1). Auxin is synthesized in young expanding leaves at the shoot apex and is actively transported down the plant in the polar transport stream (2). The basipetal direction of auxin transport is determined by the basal localization of PIN auxin efflux carriers in cell files of the stem vascular parenchyma (3). Removal of the primary apex results in activation of axillary buds below the decapitated stump due to the withdrawal of auxin, and application of auxin to the stump mimics the inhibitory effect of the apex (1). Significantly, this effect of auxin is indirect: if radiolabelled auxin is used in such experiments, buds are inhibited even though radiolabel does not accumulate in the buds (4, 5).

For many years, the indirect effect of auxin was explained by assuming that the auxin signal was relayed into the bud by a second messenger, such as the phytohormone cytokinin (CK) (6). Consistent with this idea, CK can promote bud activation directly, and CK synthesis is down-regulated by auxin in the stem (6, 7). However, according to a more recent hypothesis, bud activation can also be triggered by the efflux of auxin produced in the buds (8, 9), in which case apical dominance would rely on competition between apices for auxin transport through the main stem. A mechanism for this competition was proposed by Bennett et al. (9), based on the assumption that the main stem had a limited capacity for auxin transport. Apically-derived auxin could thus saturate the transport capacity of the main stem, preventing transport from the lateral buds. Here we show that the assumption of saturation, while intuitive, is not required for competition for transport to occur. Instead, competition can emerge from the positive feedback between auxin flux and polarization of active auxin transport, postulated by the canalization hypothesis (10, 11).

Results

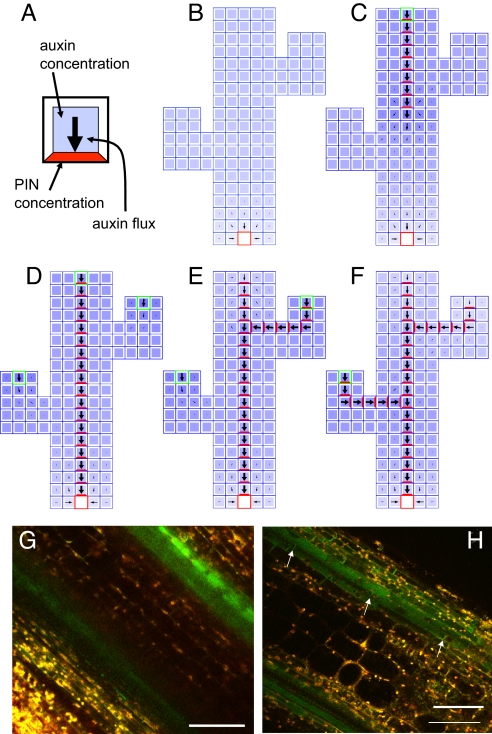

The canalization hypothesis was originally proposed as a mechanism for differentiation of vascular stands connecting auxin sources to sinks and is consistent with subsequent observations of PIN protein accumulation and polarization during vascular strand patterning (12). Following Sachs (11), we assume that the feedback between auxin flux and PIN protein polarization can also be considered at levels larger than individual cells, in particular metamers. To investigate the interaction between auxin sources, we constructed a simulation model of a branching point in which two source metamers compete for auxin transport through a common sink metamer. Specifically, we assume that the flux Φi→j of auxin from metamer i with auxin concentration ci to metamer j with concentration cj is expressed by equations proposed by Mitchison (13, 14) and restated in terms of PIN proteins (15, 16):

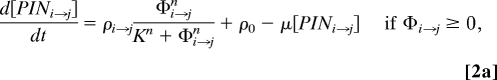

where PINi→j is the surface concentration of PIN proteins directing transport from metamer i to metamer j, T characterizes the efficiency of PIN-dependent polar transport, and D is a coefficient of diffusion. Furthermore, we assume that PINi→j changes according to the equations

|

where ρi→j is the maximum rate of auxin-flux-driven PIN allocation to the face of metamer i abutting metamer j, ρ0 is the residual (flux-independent) rate of PIN allocation, and μ is the decay constant capturing the rate with which PINs spontaneously leave the face. These equations are similar to Mitchison's (14), except that PIN allocation is described by a Hill function with coefficients K and n, rather than a quadratic function.

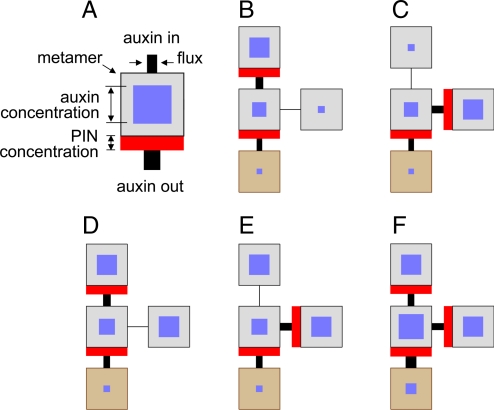

For suitable parameter settings (SI), a branching structure with metamers of this type has the behavior illustrated in Fig. 1. If there is a single source of auxin in either the terminal or lateral positions, a path of auxin flow from this source to the sink is established (Fig. 1 B and C). However, if there are 2 sources of auxin, the structure has 3 stable states, with either one or both sources supplying auxin to the sink (Fig. 1 D–F). Which of the 3 states is adopted depends on whether the sources were activated sequentially or near simultaneously. When one source is activated first, high auxin flow between this source and the sink is established. Subsequent activation of the second source does not result in auxin flow from this source to the sink (Fig. 1 D and E). An existing auxin flow from a source to a sink thus prevents the establishment of flow between a competing source and the sink. However, both sources can supply auxin to the sink concurrently if they are activated near simultaneously (Fig. 1F). The above switching behavior is consistent with the observations of Sachs (10) and emerges from feedback between PIN allocation and auxin flow: when the source and the sink have high concentrations of auxin, stable flux values may either be low or high, depending on the history of the system (see SI for mathematical analysis). Furthermore, the behavior of the model is consistent with recent observations that transport of auxin in the stem is not saturated (17), and thus the interaction between auxin sources is not mediated by limiting transport capacity of the stem.

Fig. 1.

Pathways of auxin transport in a branching structure simulated using a canalization model (Eqs. 1 and 2). (A) Schematic representation of a metamer. Edge length of the blue square is proportional to auxin concentration; width of the red rectangle is proportional to the concentration of PIN proteins in the corresponding metamer face, and width of the lines entering or leaving a metamer is proportional to auxin flux. (B–F) Stable states in a branching structure consisting of 2 potential sources of auxin in the terminal and lateral positions, a branching node, and a sink in the proximal position. (B–C) Stable states of the system with a single auxin source in either terminal (B) or lateral (C) metamer. (D–F) Stable states of the system with 2 auxin sources. The terminal source has been established before (D), after (E), or near simultaneously (F) with the lateral source.

The model captures classical experimental systems consisting of a decapitated stem segment with 2 branches (4, 18, 19). One branch typically dominates the other, and the dominating branch can be basal to the inhibited branch. In addition, sustained growth of both branches is observed in a fraction of cases. Thus, the dominant auxin transport pathway to the sink is determined by the temporal sequence in which the auxin sources were established. Extrapolating to the whole plant, the primary shoot apex is therefore dominant because it was established first, rather than because of its apical position.

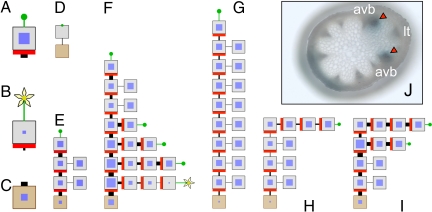

To explore further the implications of this mechanism, we modeled a developing shoot as a growing assembly of metamers (see SI for a description of the growth model). Assuming that auxin decays at some rate as it is transported basipetally, it will fall to levels below those required to inhibit axillary buds distant from the apex, effecting a transition from states D to C (Fig. 1) at the corresponding nodes. This results in acropetal activation of basal buds (Fig. 2 D–F), as often observed in nature. The model also reproduces classical decapitation experiments, in which removal of the shoot apex can activate axillary buds (Fig. 2 G–I). In the simplest case, the axillary bud closest to the decapitation site, being exposed to auxin depletion first, activates and takes over as the dominant apex (Fig. 2H). The supply of auxin from the main apex is then replaced by auxin from the activated axillary bud. This phenotype occurs in the Arabidopsis axr3 mutant: the intact axr3 plant is typically unbranched, whereas the decapitated plant produces a single lateral branch immediately below the decapitation site (20). For other parameter settings and in nature, e.g., WT Arabidopsis, decapitation may result in activation of several uppermost buds [overcompensation (21)]. This occurs when: (i) auxin efflux from a single activated bud is insufficient to dominate buds underneath, and thus a combined efflux from several lateral buds is needed for domination; (ii) bud activation is slow compared to the process of auxin depletion following decapitation (Fig. 2I); and/or (iii) auxin efflux from lateral branches is distributed sectorially and thus likely exercises only a reduced influence on the lateral apices on the other side of the stem. In nature, such sectorial distribution is a consequence of the pattern of vascular connections between lateral branches and the main stem (22). Indeed, analysis of activity from the auxin-inducible DR5 promoter in Arabidopsis main stems, just below an active axillary branch, shows that high expression is limited to the vascular bundles to which the active branch connects (Fig. 2J) (19, 22).

Fig. 2.

Apical dominance. (A–C) Schematic representations of an apex in the vegetative state (A), in the flowering state (B), and of the root (C). Other aspects are represented as in Fig. 1A. (D–F) Selected stages of the simulation of acropetal bud activation. The simulated plant initially consists of a vegetative apex and root (D). As the plant grows, auxin from the apex is transported basipetally and inhibits lateral buds close to the apex (E). Auxin levels decrease with distance from the growing apex; this decrease eventually switches lateral buds to the active state, producing an acropetal activation sequence (F). (G–I) Simulation of decapitation experiments. After decapitation of a growing plant (G), the lateral apex closest to the decapitation site is activated and becomes dominant (H). Several buds close to the decapitation site are activated in the case of overcompensation (I). (J) GUS expression (red arrowheads) detected with the chromogenic substrate X-Gluc, driven by the DR5 auxin-responsive promoter in an Arabidopsis stem section immediately below a growing lateral shoot, prepared as in ref. 9. Lateral shoots vascularize into 2 adjacent vascular bundles in the main stem (avb) (19, 22) lt: leaf trace.

Similar branching processes accompany the floral transition in intact plants, assuming that auxin supply from the apex decreases upon the switch to flowering. We modeled this reduction as a decreased target auxin concentration H (Eq. 10 in SI), representing the concentration at which new auxin synthesis is prevented due to feedback inhibition by existing auxin.

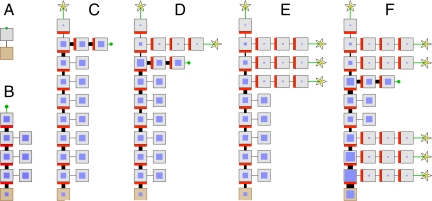

Until they undergo floral transition themselves, successively activated lateral shoots export auxin at a high rate and thus inhibit activation of buds below them. In simulations this process can generate a basipetal cascade of bud activation (Fig. 3 A–E), corresponding to the basipetal sequences of lateral branch outgrowth and flowering frequently observed in nature (23). The timing of activation is affected by the same factors as in decapitation and, in addition, the timing of floral transition in the lateral branches. For example, if buds arrest close to floral transition then the interval from bud activation to floral transition will be short. Residual production of auxin after floral transition delays and eventually stops the activation sequence (Fig. 3E), as in WT Arabidopsis, where the activation sequence is typically restricted to 2 to 4 topmost rosette branches. The basipetal activation sequence in the upper part of the stem can occur concurrently with the acropetal activation sequence at the base, resulting in a convergent activation pattern (Fig. 3F). Such a pattern occurs in Arabidopsis with a prolonged vegetative phase (24).

Fig. 3.

Simulation models of basipetal and convergent patterns of bud activation controlled by auxin transport. Schematic representations are as in Figs. 1 and 2. (A–E) Selected stages of basipetal bud activation. During vegetative growth beginning with the initial structure (A), the main apex creates a sequence of metamers with associated lateral buds (B). The flow of auxin from the apex inhibits the outgrowth of lateral apices. Upon transition to flowering (C), the supply of auxin to the topmost metamer decreases, resulting in the activation of its lateral bud (transition from state D to C in Fig. 1). Auxin produced by these buds is exported into the main stem, inhibiting the bud below. After transition of the topmost bud to the flowering state, the next lateral bud becomes activated (D). The resulting relay process continues until it is stopped by the residual supply of auxin from the floral apices (E). (F) Convergent activation pattern resulting from a combination of this process with acropetal activation (Fig. 2 D–F).

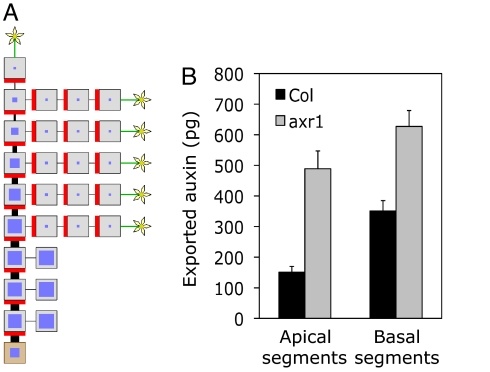

To test our model further, we investigated its ability to capture the behavior of mutant Arabidopsis by using modified parameter values. We first simulated the behavior of axr1 mutants. AXR1 is required for auxin-regulated transcription and affects the negative feedback loop that down-regulates the production of auxin (2). In axr1, this down-regulation is less effective, which we simulated by raising the concentration at which auxin production was stopped (SI, Eq. 10). The resulting axr1 model generates a basipetal pattern of bud activation similar to that observed in the WT model, except that the auxin levels and the total number of activated buds are increased, while PINs are maintained at WT levels (Fig. 4A). This pattern is consistent with experiments which show that axr1 mutants have more branches (25, 26), higher levels of auxin moving in the stems (Fig. 4B), and the same auxin conductivity as WT (9). It is likely that the axr1 mutation further promotes branching by reducing the ability of auxin to down-regulate cytokinin synthesis (27). Nevertheless, our simulations suggest that the impact of axr1 on feedback regulation of auxin synthesis is sufficient to cause an increase in bud activation.

Fig. 4.

The axr1 phenotype. (A) Simulation model. Compared to the WT (Fig. 3E), auxin concentrations and bud activation increase, but PIN levels are unaffected. (B) Auxin mass (pg) exported from the basal end of 2 cm stem segments excised from the apical and basal region of the bolting stems of glasshouse-grown WT (Col) and axr1–3 mutant (axr1) Arabidopsis plants. Error bars: SEM, n ≥ 4.

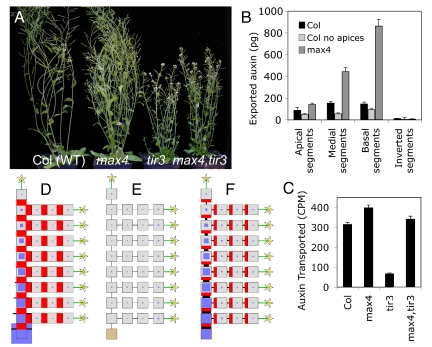

We next investigated the ability of the model to simulate the tir3/big phenotype, which is characterized by increased shoot branching and reduced auxin transport compared to WT (28, Fig. 5 A and C). TIR3/BIG is thought to be required for the accumulation of active PIN proteins on the membrane (28, 29). It encodes a very large protein with similarity to the Drosophila PUSHOVER protein, known to be involved in delivering proteins to the membrane at the neuromuscular junction (30). Based on these data, we simulated tir3 by reducing the flux-driven PIN allocation rate ρi→j (SI). In these simulations, auxin flux after floral transition is insufficient to maintain canalized polar PIN allocation, which eliminates competition between auxin sources and increases branching (Fig. 5E). Raising the PIN turnover rate μ yields similar results.

Fig. 5.

Arabidopsis max4 and tir3 mutants and their interactions. (A) Aerial phenotype of 6-week-old Columbia WT, max4–1, tir3–101, and max4–1,tir3–101 plants. (B) Mean auxin mass (pg) exported from 2 cm stem segments excised from the apical, medial, and basal region of the bolting stems of WT (Col) and max4–1 mutant (max4) plants. For the “Col no apices” samples, all visible shoot apices above the point of stem excision were removed 24 h before the stem segments were excised. The auxin was collected from the basal end of the segments, except in the “inverted” segment samples, where it was collected from the apical end. Error bars: SEM, n ≥ 4. (C) Mean radiolabelled auxin (cpm) transported along excised stem segments of the genotypes shown in (A). Error bars: SEM, n = 10. (D) Simulation of max mutant. PIN concentrations, auxin fluxes and auxin concentrations are increased with respect to the WT (Fig. 3E). (E) Simulation of tir3 mutant. PIN concentrations, auxin fluxes, and auxin concentrations are decreased with respect to the WT (Fig. 3E). (F) Simulation of max, tir3 double mutant. PIN concentrations, auxin fluxes, and auxin concentrations are increased with respect to the WT (Fig. 3E), but decreased compared to max (D).

Increased branching is also characteristic of the max mutant phenotype, which results from defects in strigolactone synthesis or signaling (31, 32). In striking contrast to tir3, the max mutants have increased PIN accumulation and increased auxin flux through the stem (9). We modeled increased PIN levels by changing the same parameters as for modeling tir3 but in the opposite direction, i.e., by increasing the PIN allocation rate ρi→j or decreasing the PIN turnover rate μ (SI). These changes promote simultaneous auxin efflux from multiple buds, creating a gradient of increased auxin flux along the main stem axis and increasing branching, as observed in the max phenotype (Fig. 5D).

The simulations also exhibit a significant increase in auxin concentration along the stem (Fig. 5D). To determine whether such a gradient exists in max stems, we measured the amount of auxin in the polar transport stream of 6-week-old WT (Col) and max4 plants with an advanced stage of branch growth. Auxin exported from the basal end of isolated apical, medial, and basal bolting stem segments was collected over a 24-hour period. The amount of auxin collected from the apical end of each segment was negligible (Fig. 5B), indicating that the auxin collected from the basal end was indeed representative of the polar transport stream. Furthermore, removal of all apices from WT plants 24 h before the experiment resulted in reduced auxin collection from all segments (Fig. 5B), supporting the hypothesis that the auxin in the segments is derived from active shoot apices above. Both WT and max4 apical stem segments exported significantly less auxin than medial and basal segments (Fig. 5B). Moreover, auxin export from max4 segments was significantly higher, and increased more between apical, medial, and basal segments, than in the WT. These results are consistent with our simulations.

Our simulations thus resolve the apparent paradox that increased branching can be achieved either by decreasing accumulation of active PINs on the membrane, as in tir3, or by increasing accumulation, as in the max mutants. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis of opposing roles for TIR3 and MAX in auxin transport canalization and raise the question of the relationship between them. To address this question, we constructed the max4, tir3 double mutant. It shows a highly branched phenotype similar to the parents, with no evidence of additivity in branch number (Fig. 5A). We then compared auxin transport in the stems of WT, the 2 single mutants, and the double mutant (Fig. 5C). Consistent with previously published data, tir3 had approximately 25% of the auxin transport observed in WT (28, 29) and max4 had approximately 125% (9). The low auxin transport phenotype of tir3 is suppressed in the max4 background. This behavior is captured in the model by combining the parameter manipulations described above, e.g., by simultaneously reducing PIN allocation rate ρi→j to simulate tir3, and PIN turnover μ to simulate max4 (Fig. 5F). These results further support the hypothesis that both genes regulate the allocation of active PINs to the plasma membrane.

The above models rely on the assumption that the interplay between auxin transport and PIN polarization at the cellular level can be integrated over whole metamers. To validate this assumption, we constructed a schematic cell-level model, modified from ref. 33 (Fig. 6). This model behaves in a similar manner to the metamer-level model; in particular, it reproduces the basipetal cascade of bud activation. In addition, by operating at the cellular level, it captures the convergence of auxin flow into focused streams, precursors of vascular differentiation, as predicted by the canalization hypothesis (10). The model is thus consistent with the observations of Sachs (34, 35) that vascular connections may be formed concurrently with, and indeed as an integral part of, release of buds from apical dominance.

Fig. 6.

Bud activation at the cellular level: simulations (A–F) and in planta data (G and H). (A) Schematic representation of a cell. Auxin concentration is shown as the intensity of blue, PIN as the intensity of red, and the dominant direction and magnitude of auxin flux is indicated by a black arrow. (B–F) Selected stages of the simulation. A longitudinal section of a stem with 2 buds is represented schematically as a grid of cells, approximating the shape of the section. Source cells are outlined in green; the sink is outlined in red. In the initial state there is small background production of auxin in every cell, and a single sink cell is present at the base (B). Following the placement of an auxin source at the top of the main stem, a vascular strand running through the stem emerges (C). Subsequent placement of auxin sources in the 2 buds does not trigger formation of lateral vasculature (D) until the auxin source at the top of the main stem is removed (E). Removal of the source in the upper bud causes the lower bud to be activated (F). (G and H) PIN1 localization in Arabidopsis axillary bud stems. Hand sections through the stems of inhibited (G) and active (H) axillary buds carrying the PIN1 protein fused to GFP under the control of the native PIN1 promoter. Arrows indicate an example of basally localized GFP in a file of cells. (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

We confirmed these observations experimentally by examining localization of PIN1 protein in the stems of dormant and active axillary buds. The uppermost cauline nodes were excised from bolting stems of transgenic Arabidopsis carrying the PIN1 protein fused to GFP under the control of the PIN1 promoter (36). The stem segments were maintained in Eppendorf tubes containing nutrient solution, and the apex was either kept intact or excised (19). With the apex intact, cauline buds remained dormant (mean bud length after 7 days for n = 80 buds on 40 explants was 2.2 mm with SE = 0.1 mm), whereas with the apex removed, the buds became active (mean bud length after 7 days for n = 80 buds on 40 explants was 10.9 mm with SE = 1.0 mm). To investigate PIN localization early in bud activation, buds from intact and decapitated explants were hand sectioned longitudinally 3 days after explant excision and examined by multiphoton microscopy. GFP was detected in the stems of both dormant and active buds in cells surrounding the central pith tissue (Fig. 6 G and H). In dormant bud sections, cells with basally localized PIN1 were rare (mean = 1.4 per field, SE = 0.5, n = 8), and a file of cells with aligned PINs was detected in only one of the 8 buds examined. In contrast, in the stems of active buds, we observed significantly more cells with basally localized PIN1 (mean = 4.9 per field, SE = 0.4, n = 10). These cells frequently occurred in files, consistent with activation-associated auxin transport canalization. Our results are consistent with the observations of Morris and Johnson (36) who demonstrated that actively growing pea shoots transport auxin basipetally, whereas those inhibited by apical dominance do not, and that this is due primarily to differences of polarity of auxin transport rather than transport activity per se.

Discussion

The canalization hypothesis postulates autoregulation of auxin flux to explain the emergence of narrow auxin transport paths leading to vascular strand formation. It is supported indirectly by experimental data (10, 11) and simulations (13–15, 33), showing that it captures diverse aspects of vascular patterning. It relies on the measurement of auxin flux by cells, for which no mechanism has yet been found. Nevertheless, several hypothetical mechanisms for the measurement of fluxes through the measurement of concentrations have been proposed (37, 38). The feedback between auxin transport and flux thus provides a plausible entry point for the analysis of auxin-driven processes.

We have shown that the same mechanism that canalizes auxin transport can also switch auxin transport paths on or off, resulting in long-distance signaling between auxin sources. The lack of path for auxin efflux from incipient primordia in the apical meristem of dormant buds may be the cause of bud arrest, since auxin efflux appears to be required to initiate and maintain leaf development in phyllotactic progression (16, 39–41).

Our model provides a plausible unifying explanation for apical dominance and the acropetal, basipetal, and convergent patterns of bud activation observed in nature. Model simulations are consistent with the branching habit, auxin distribution, and PIN accumulation patterns in WT and mutant Arabidopsis plants. The model also reconciles the apparently paradoxical observations that mutants with increased branching can have either low (tir3), normal (axr1) or elevated (max4) auxin transport. In each case, a change in the value of a single model parameter produces results consistent with the observed phenotype. The parameters chosen for manipulation correspond well with molecular-level understanding of TIR3 and AXR1 function. The mode of action of the MAX pathway is unknown, but our data and simulations suggest that MAX acts by modulating PIN cycling between the plasma membrane and endomembrane system. The model does not require targeted action of MAX, localized to specific sites such as buds or the main stem, but allows for its systemic operation throughout the auxin transport network. This is consistent with the expression of MAX2, a signal transduction component in the strigolactone pathway, throughout the vasculature (42). Our model of bud activation thus links molecular-level processes that underlie canalization with macroscopic features of plant architecture.

The presented model focuses on the proposed auxin transport switch and characterizes its essence at the minimum level of model complexity. We have demonstrated the utility of this model in generating testable predictions and hypotheses. The model can now be used as a framework for further studies. Experimentally determined parameters can be included as they become available and additional regulatory elements can be incorporated. Of particular interest are the ability of cytokinin to activate buds in the presence of apical auxin (6, 7), and the ability of auxin to regulate transcription of PIN (44), strigolactone, and cytokinin biosynthesis genes (45, 27). A more complete model, incorporating these factors, will open the way to investigate the stability and sensitivity of the switch, and understand plasticity and robustness of the auxin transport network.

Materials and Methods

Plant lines are described in SI. Growth conditions were as described in refs. 9 and 19. Auxin in the polar transport stream was collected and quantified from 2 cm bolting stem segments as described in SI. Auxin transport measurements were carried out in similar segments, as described in ref. 9. PIN:GFP fusion protein was visualized in longitudinal hand sections of the bud stem using multiphoton microscopy as described in SI. Models were implemented as described in SI. The source code for all models is available on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Gun Lövdahl and Roger Granbom for excellent technical assistance. The work in Calgary was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; in York by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Gatsby Foundation; and in Umeå by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906696106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thimann K, Skoog F. Studies on the growth hormone of plants III: The inhibitory action of the growth substance on bud development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1933;19:714–716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.19.7.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ljung K, Bhalerao RP, Sandberg G. Sites and homeostatic control of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis during vegetative growth. Plant J. 2001;28:465–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gälweiler L, et al. Regulation of polar auxin transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis vascular tissue. Science. 1998;282:2226–2230. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris DA. Transport of exogenous auxin in two-branched dwarf pea seedlings (Pisum sativum L.) Planta. 1977;136:91–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00387930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booker JP, Chatfield SP, Leyser HMO. Auxin acts in xylem-associated or medullary cells to mediate apical dominance. Plant Cell. 2003;15:495–507. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cline MG. Apical Dominance. Bot Rev. 1991;57:318–358. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka M, Takei K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Mori H. Auxin controls local cytokinin biosynthesis in the nodal stem in apical dominance. Plant J. 2006;45:1028–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C-J, Bangerth F. Autoinhibition of indoleacetic acid transport in the shoot of two-branched pea (Pisum sativun) plants and its relationship to correlative dominance. Physiol Plant. 1999;106:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett T, et al. The Arabidopsis MAX pathway controls shoot branching by regulating auxin transport. Curr Biol. 2006;16:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs T. The control of patterned differentiation of vascular tissues. Ad Bot Res. 1981;9:151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs T. Pattern Formation in Plant Tissues. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauer M, et al. Canalization of auxin flow by Aux/IAA-ARF-dependent feedback regulation of PIN polarity. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2902–2911. doi: 10.1101/gad.390806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchison GJ. A model for vein formation in higher plants. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1980;207:79–109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchison GJ. The polar transport of auxin and vein patterns in plants. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1981;295:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feugier F, Mochizuki A, Iwasa Y. Self-organization of the vascular system in plant leaves: Inter-dependent dynamics of auxin flux and carrier proteins. J Theor Biol. 2005;236:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jönsson H, Heisler MG, Shapiro BE, Meyerowitz EM, Mjolsness E. An auxin-driven polarized transport model for phyllotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1633–1638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509839103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brewer PB, Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Rameau C, Beveridge C. Strigolactone acts downstream of auxin to regulate bud outgrowth in pea and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:489–493. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.134783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snow R. Experiments on growth inhibition. Part II-New phenomena of inhibition. Proc Roy Soc London Ser B. 1931;108:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ongaro V, Bainbridge K, Williamson L, Leyser O. Interactions between axillary branches of Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2008;1:388–400. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cline MG, Chatfield SP, Leyser O. NAA restores apical dominance in the axr3–1 mutant of Arabisopsis thaliana. Ann Bot (London) 2001;87:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belsky AJ. Does herbivory benefit plants? A review of evidence. Am Nat. 1986;127:870–892. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang J, Tang T, Donnelly P, Dengler N. Primary vascular pattern and expression of ATHB-8 in shoots of Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2003;158:443–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hempel FD, Feldman LJ. Bi-directional inflorescence development in Arabidopsis thaliana: Acropetal initiation of flowers and basipetal initiation of paraclades. Planta. 1994;192:276–286. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grbic V, Bleecker AB. An altered body plan is conferred on Arabidopsis plants carrying dominant alleles of two genes. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:2395–2403. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lincoln C, Britton JH, Estelle M. Growth and development of the axr1 mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1990;2:1071–1080. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stirnberg P, Chatfield SP, Leyser HMO. AXR1 acts after lateral bud formation to inhibit lateral bud growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:839–847. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordström A, et al. Auxin regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana: A factor of potential importance for auxin–cytokinin-regulated development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8039–8044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402504101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruegger M, et al. Reduced naphthylphthalamic acid binding in the tir3 mutant of Arabidopsis is associated with a reduction in polar auxin transport and diverse morphological defects. Plant Cell. 1997;9:745–757. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.5.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gil P, et al. BIG: A calossin-like protein required for polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1985–1997. doi: 10.1101/gad.905201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards S, Hillman T, Stern M. Mutations in the Drosophila pushover gene confer increased neuronal excitability and spontaneous synaptic vesicle fusion. Genetics. 1996;142:1215–1223. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.4.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez-Roldan V, et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature. 2008;455:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature07271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umehara M, et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature. 2008;455:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature07272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rolland-Lagan AG, Prusinkiewicz P. Reviewing models of auxin canalization in the context of leaf vein pattern formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1995;44:854–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sachs T. A control of bud growth by vascular tissue differentiation. Israel J Bot. 1970;19:484–498. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benkova E, et al. Local efflux dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell. 2003;115:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris DA, Johnson CF. The role of auxin efflux carriers in the reversible loss of polar auxin transport in the pea (Pisum sativum L.) stem. Planta. 1990;181:117–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00202333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer EM. Auxin-regulated cell polarity: An inside job? Trends Plants Sci. 2009;14:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coen E, Rolland-Lagan AG, Matthews M, Bangham JA, Prusinkiewicz P. The genetics of geometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4728–4735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306308101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinhardt D, et al. Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature. 2003;426:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature02081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbier de Reuille P, et al. Computer simulations reveal properties of the cell-cell signalling network at the shoot apex in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1627–1632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith RS, et al. A plausible model for phyllotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1301–1306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510457103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stirnberg P, Furner I, Leyser O. MAX2 participates in an SCF complex which acts locally at the node to suppress shoot branching. Plant J. 2007;50:80–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vieten A, et al. Functional redundancy of PIN proteins is accompanied by auxin-dependent cross-regulation of PIN expression. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2005;132:4521–5431. doi: 10.1242/dev.02027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorefan K, et al. MAX4 and RMS1 are orthologous dioxygenase-like genes that regulate shoot branching in Arabidopsis and Pea. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1469–1474. doi: 10.1101/gad.256603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.