Abstract

Many pharmaceutical drugs are isolated from plants used in traditional medicines. Through screening plant extracts, both traditional medicines and compound libraries, new pharmaceutical drugs continue to be identified. Currently, two plant-derived agonists for γδ T cells are described. These plant-derived agonists impart innate effector functions upon distinct γδ T cell subsets. Plant tannins represent one class of γδ T cell agonist and preferentially activate the mucosal population. Mucosal γδ T cells function to modulate tissue immune responses and induce epithelium repair. Select tannins, isolated from apple peel, rapidly induce immune gene transcription in γδ T cells, leading to cytokine production and increased responsiveness to secondary signals. Activity of these tannin preparations tracks to the procyanidin fraction, with the procyanidin trimer (C1) having the most robust activity defined to date. The response to the procyanidins is evolutionarily conserved in that responses are seen with human, bovine, and murine γδ T cells. Procyanidin-induced responses described in this review likely account for the expansion of mucosal γδ T cells seen in mice and rats fed soluble extracts of tannins. Procyanidins may represent a novel approach for treatment of tissue damage, chronic infection, and autoimmune therpies.

Keywords: procyanidin, mucosa, apple, grape seed, polyphenol, priming

INTRODUCTION

Humankind has studied and used plants as medicinal compounds for millennia. There is no known date for when this practice began since use of plant medicines predates recorded history1;2. Although understanding of the immune system and drug interactions has clearly progressed over time, medicinal plants are still a dominant source of drugs and drug candidates in many fields of medicine, supporting a high incidence of pharmaceutically relevant structures in plants. One constituent of plant extracts, which shows effectiveness in medicine, are polyphenols. Tannins are a subclass of polyphenols and have a high binding affinity for proteins3–5. Defined immunologic effects of tannins are often confusing and even contradictory since tannin structures are diverse and have highly varied effects on different immune cells. This variable response to tannins has stunted research into the properties of these plant metabolites. Increasing evidence demonstrates select binding affinities of individual tannin species6;7that explains, in part, the discrepancies in immunological function. Herein, we describe the immune responses of a select group of tannins called procyanidins (also called condensed tannins). These compounds are derived from a limited number of plant extracts, which activate γδ T cells with a preference for the mucosal population.

The intestinal mucosa contains unique populations of lymphocytes rarely observed in circulation. These cells are critical for maintaining the integrity of the epithelium8;9 by recognizing pathogenic flora and initiating immune responses.10;11 Likewise, these lymphocytes prevent excessive inflammatory responses that would destroy the epithelial layer and decrease the effectiveness of this pathogen barrier.12–14 Furthermore, mucosal γδ T cells recognize damaged epithelia and secrete growth factors to aid in the repair of the mucosal barrier.15 γδ T cell maintenance of the epithelium is important in preventing both bacterial and protozoan infection.16 Although found predominantly in the mucosal surfaces, tissue-associated γδ T cells are present in small quantities in circulation. These γδ T cells demonstrate a mucosal phenotype17;18 and are an accessible population for evaluation in vitro.

This review will focus on our current knowledge of the cellular response to procyanidins and steps taken to isolate the active compounds from original plant sources. The cellular response of γδ T cells to plant tannins that will be described in this review focuses on the most procyanidin-responsive γδ T cell subset, those found in the mucosal surfaces. The γδ T cell response to procyanidins is defined as a subtle, antigen-independent “priming” effect.19 This effect is characterized by a rapid change in gene expression patterns that allow the γδ T cell to more quickly respond to pathogens or other secondary signals, but does not directly lead to cell expansion or production of cytokines such as IFNγ, which are responses indicative of overt activation.20

Chemical separation techniques used to isolate components of biologically active tannin fractions have led to the identification of the procyanidin trimer C1 (PC1) as a potent agonist for mucosal γδ T cells. This compound contains activity similar to the total crude tannin preparations described previously21 and maintains activity on murine (Freedman, et al. in preparation), bovine (unpublished observations), and human mucosal γδ T cell populations. Isolation and characterization of the procyanidins may substantiate the use of some plant-based, procyanidin-containing traditional medicines for the treatment of many immunological disorders. Furthermore, enrichment of the most robust components may enable improvement upon these traditional therapies and promote their increased and safer use for wound healing and many inflammatory diseases.

I. MEDICINAL PLANTS AS DRUG SOURCES

A. History of medicinal plants

The plant and animal kingdoms diverged between 720 million and 1.3 billion years ago.22 Since this divergence, the two kingdoms have evolved into hundreds of thousands of species with numerous different biochemical pathways. Interestingly, plants and animals retain many of the same basic pathways from their common ancestor. These include systems such as the receptor tyrosine kinases, Krebs cycle, amino acid synthesis, and many components of gene translation and regulation.23–25 Plants have also evolved to produce additional and alternative biochemical pathways that impact shared common pathways, which are of importance to medicine. Therefore, plant products present an exceptional source for potential drug structures because of this rich source of unique, biologically active compounds. The diverse applications of these plant compounds in human pharmaceuticals are demonstrated by the historic and effective use of plants as medicines, yet only a small fraction have been characterized and applied as drugs.

Herbal medicine is the oldest form of medicine used by humankind, and many of today’s drugs are directly derived from traditionally used plants. There is extensive archeological evidence for humanity’s use of plants as medicines dating to prehistoric times. The earliest evidence of selective use of therapeutic herbs is found in a Neanderthal grave from 60,000 B.C. These remains were discovered with eight species of medicinal plants including Achillea (yarrow, anti-coagulant/pain reliever).1 and Ephedra altissima (Ephedra, Table 1)26 Additionally, dried woody fruit from Piptoporus betulinus was discovered on the remains of a man in present day Switzerland from 3300 B.C. and is thought to have been used to treat the parasites discovered in his intestines. Piptoporus betulinus contains agaric acid, which is a powerful purgative and induces short bouts of diarrhea, which would have reduced the parasite burden.27

Table 1.

Common Pharmaceutical Drugs Derived from Botanical Sources

| Botanical name | Common name | Indigenous use | Origin | Medical use | Active compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhatoda vasica | N/A | Antispasmodic, antiseptic, | India, Sri Lanka | Cough suppressant | Bromhexine (Bisolvon®)* |

| Catharanthus roseus | Periwinkle | Diabetes, fever | Madagascar | Chemotherapy | Vincristine (Oncovin®)* |

| Condrodendron tomentosum | N/A | Arrow poison | Brazil, Peru | Muscular relaxant250 | D-Tubocurarine |

| Pausinystalia yohimbe | Yohimbe | Aphrodisiac | Africa | Erectile dysfunction251 | Yohimbine |

| Convolvulus scammonia | Scammony | Purgative | Mediterranean | Purgative | scammonin |

| Podophyllum peltatum | May apple | Laxative, skin infections | North America | Chemotherapy | Podophyllotoxin*(Eposin®) |

| Cinchona | Cinchona tree | Malaria | South America | Anti-malarial antipyretic | quinine† |

| Camptotheca acuminata | Chinese Camptotheca | N/A | China, Tibet | Chemotherapy | Camptothecin*(Hycamtin®) |

| Colchicum autumnale | Autumn crocus | Rheumatism, arthritis,gout | Europe | Gout Chemotherapy | Colchicines†(ColBenemid®) |

| Taxus brevifolia | Pacific Yew | N/A | North America | Chemotherapy | Paclitaxel*(Taxol®) |

| Cannabis sativa | Marijuana | Pain, fever, nausea | Eastern Europe, India | Antiemetic Appetite stimulant | Tetrahydrocannabinol*(Marinol®) |

| Papaver | Poppy | Pain, euphoric | Eurasia, Africa, | Analgesic | Morphine† |

| somniferum | North America | Codeine† | |||

| Salix alba | White willow | Pain, fever | Europe | Analgesic antipyretic | Acetylsalicylic acid Aspirin®† |

| Rauvolfia serpentina | Serpent root | Insanity | India, Southeast Asia | Antipsychotic hypertension | Reserpine*(Serpasil®) |

| Digitalis purpurea | Foxglove | Pulse regulation | Europe | Antiarrhythmic | digitoxin† |

| Ephedra sinica | Ma Huang, Ephedra | Stimulant, asthma | Eurasia, Africa, North America | Stimulant, Bronchodilator, Decongestant | ephedrine† |

| Atremisia annua | Chinese wormwood | Skin diseases, malaria | China | Antimalarial | artemisinin |

| Mandragora | Mandrake | Anesthesia | Europe | Nausea | scopalamine |

| officinarum | Sleep aid | anasthesia |

FDA approved.

Marketed prior to the revision of the Food and Drugs Act (1938). These chemical entities were at that time marketed and therefore grandfathered. Therefore, they are not technically FDA approved.

The extensive use of medicinal herbs in early human history is further demonstrated by the appearance of herbalism texts in many early civilizations. The earliest written texts describing the medicinal uses of plants originate from Mesopotamia (2700 B.C.) and Egypt (1550–1600 B.C.). These texts describe various medicinal effects of herbs including the following: senna, juniper, frankincense, pomegranate root, henbane, flax, oakgall, aloe, caraway, elderberry, garlic, peppermint, cedar, poppy, and lotus.1;28;29 Many remedies described in early texts are still in use as herbal remedies or as sources for pharmaceutical drugs. For example, morphine is an integral element of modern medicine derived from poppy bud. The untapped potential for effective therapies in historical and present day herbal medicines warrants further scientific investigation.

B. Pharmaceutical Drugs Developed from Traditional Herbal Medicines

The use of many traditional, plant-derived medicines continues today, not only in the form of herbal remedies, but also as pharmaceutical drugs. In fact, 25% of pharmaceutical drugs are plant-derived.30 Most of these plant-derived drugs were identifies as a result of studies to isolate the active components of traditional medicines.31 Present-day advances in chemistry and biochemistry allow for the isolation of the active components from the original herbal medicines. The biological activities of plants encompass a large number of therapeutic uses, ranging from cough suppressants to anti-psychotics (Table 1). The most noteworthy role of plant-derived drugs in current medicine includes anti-cancer drugs32–34 and analgesics,29;35 wherein these plant-derived drugs are the primary sources for the majority of available therapies. Furthermore, many of the compounds isolated from traditional medicines are used as lead candidates that can be modified or chemically synthesized to produce new generations of pharmaceutical drugs. Therefore, plant-derived drugs often serve as a drug in their own right, and also provide a template structure for the production of new generations of drugs. With the advent of high-throughput screening tools and the availability of numerous organic compound libraries, the scientific community is now able to test very specific therapeutic targets for plant-derived medicines. We have investigated one specific cell population, the γδ T cell, for responses to plant-derived agonists.

II. γδ T CELL RESPONSES TO MEDICINAL PLANTS

A. γδ T cells

After twenty five years of studying the γδ T cell36, our understanding of the functions of this immune cell population remain relatively limited. It is known that γδ T cells recognize, in an innate manner, many different immunological insults via a large array of surface receptors, including receptors for recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs),37–40 lipid antigen presented by CD1,41 damaged tissue,42;43 and targets of NK-associated receptors.44 The ability to sense numerous changes in the extracellular environment allows γδ T cells to participate in varied functions ranging from tumor-surveillance to maintaining mucosal integrity.

There are several different γδ T cell subsets with distinct effector functions. However, all mammalian species studied share two principal subsets with vastly different immune functions. One subset of γδ T cells is generally found in circulation (Vδ2 T cells in humans), and the other with specificity to mucosal surfaces and other tissue sites (Vδ1 T cells in humans). The circulating population of γδ T cells has innate effector functions against pathogens and cancerous cells, and will migrate to sites of infection.45–47 This document is not intended to provide an exhaustive review of circulatory γδ T cell function [reviewed in48].

The second population of γδ T cells is commonly found in the tissues, though a limited number can be found in circulation. These mucosal γδ T cells act to maintain the epithelial barrier by modulating inflammatory immune responses49;50 and healing damaged epithelium,51 thereby maintaining homeostasis.52

B. Regulatory functions of γδ T cells

γδ T cells play a critical role in maintaining the inflammatory response. This role is well documented in γδ T cell knockout mice. These mice are more susceptible to sepsis-induced mortality during cecal ligation 53. Additionally, γδ knockout mice, while able to clear parasite infection as readily as wildtype demonstrate a more damaged epitheilium54. This indicates, at least in this model of infection, the primary role of γδ T cells is not pathogen control, but rather maintenance of epithelial integrity.

γδ T cells utilize a variety of different mechanisms to regulate the inflammatory response. In addition to recruiting necessary cells55;56 and producing Th cytokines dependant upon the type and progression of infection 57–63 γδ T cells additionally mediate inflammatory balance by inducing apoptosis in opposing cell populations. Huber et al., have noted a subset-specific regulation of the T-helper cytokine balance. Specifically, Vγ4 T cells a murine circulating γδ T cell subset, kill Th2 cells, thereby promoting a pro-inflammatory, CD8 pathology64. Alternatively, Kirby et al. describe γδ T cell-directed apoptosis of macrophages and dendritic cells during streptococcus pneumoniae-mediated lung infection. This controls the proinflammatory state as observed by the reduced inflammation in wildtype mice as opposed to γδ T cell knockout mice.65

C. γδ T cell responses to plant metabolites

To date, two classes of plant metabolites with distinct effects on subsets of γδ T cells have been characterized, and many others are being investigated. These plant metabolites include the non-protein prenyl pyrophosphates, which activate the human, circulating γδ T cell subset, and procyanidins, which preferentially activate mucosal γδ T cell subsets. These activities may be developed as therapeutic treatments depending upon the desired γδ T cell effector function.

1. Prenyl pyrophosphates

The most-characterized class of plant derived γδ T cell agonists, prenyl pryophosphates (also called phosphoantigens), are restricted to activating Vδ2 T cells. These γδ T cell populations are found exclusively in humans and non-human primates and constitute the majority of circulating γδ T cells in these species. The most active of these compounds are intermediates of the non-mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis that is unique to plants and some bacteria.66 Alternatively, the animal system relies upon the mevalonate pathway for production of the final product of both the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways, isopentylpyrophosphate (IPP). IPP is a prenyl pyrophosphate used for downstream synthesis of cholesterol, prenylated proteins, and ubiquinone. Although IPP demonstrates some activity regardless of the source, prenyl pyrophosphate intermediates produced using the non-mevalonate pathway are 30,000-fold more active γδ T cell agonists than animal-derived prenyl pyrophosphates.67

A common source of prenyl phosphate metabolites is mistletoe, which is a commonly used herbal remedy.68 However, many other plants produce prenyl phosphates. Additionally, plants often produce functional mimics of prenyl phosphates. These mimics act by increasing the endogenous production of prenyl phosphates and include the alkylamines and bisphosphonates, which function by inhibiting conversion of IPP to other downstream products, thereby preventing the catabolism of IPP and increasing endogenous concentrations of IPP. The alkylamines are another example of a biologically-active, plant-derived compound. The alkylamine, ethylamine, and its precursor form L-theanine, are found in brewed tea. As these compounds stimulate the γδ T cell subset that has pro-inflammatory attributes, these agonists are in development for their potential use in treatment of cancer69 and persistent infections.70 Extensive work concerning the prenyl pyrophosphates is reviewed elsewhere.71

2. Procyanidins and other plant-derived γδ T cell agonists

We have recently described another γδ T cell agonist, from the polyphenol fraction of non-ripe apple peel (APP).72;73 As with the most active intermediates of the non-mevalonate pathway, polyphenols are not produced by animals and the plant kingdom is their unique source.74 The polyphenol class of metabolites is highly varied and contains numerous compounds with biological activity on mammalian cells. γδ T cell regulatory activity is found in the procyanidin fraction of polyphenols.

Many plant extracts with biological activities remain to be tested for γδ T cell activity. Although our recent efforts were focused on the procyanidins, other plant preparations, including compounds from Funtumia elastica bark, Angelica sinensis root,75 cocoa,76 safflower oil, green tea, and a fruit and vegetable mixture,77 also display γδ T cell agonist activity. Whether these products contain additional unique plant-based γδ T cell agonists remains to be seen, but their potential as γδ T cell agonists appears promising.

III. POLYPHENOL BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY

A. Plant polyphenols

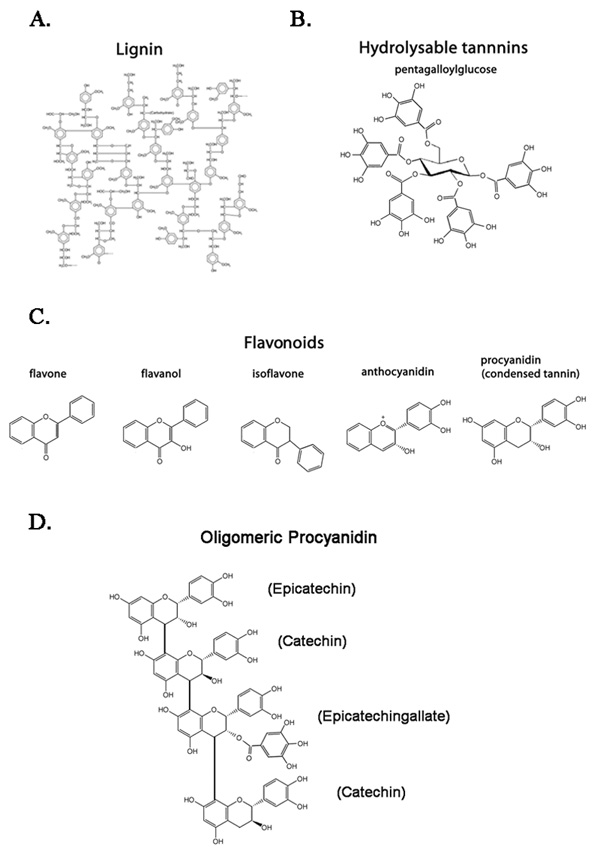

The polyphenol class of plant metabolites is characterized by the presence of multiple phenol rings. Polyphenols are subdivided into three categories: lignin, hydrolysable tannins, and flavonoids (Fig. 1). Flavonoids are the most diverse category of polyphenols and include flavones, flavonols, anthocyanidins, isoflavones, and procyanidins (condensed tannins). Tannins, both procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins, are so named for their use in the tanning of leather or hides based on their ability to bind and precipitate proteins. There are a vast number of processes for which plants employ tannins, ranging from herbivore protection to hormone regulation. Procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins differ in their core polyphenol structure and have differing functions both in the plant and on mammalian cells. Recent evidence shows that individual tannins contain preferential binding affinities for unique protein sequences, which may explain some of the contradictory results observed when mammalian systems are treated with these plant metabolites78;79).

Figure 1. Structures of common polyphenol subunits.

A) Proposed structure for lignin, a complex, heterogeneous scaffold for carbohydrates.265 B) Pentagalloylglocose, the simplest hydrolysable tannin. The sugar core is oriented in the perpendicular plane. The five galloyl residues can be replaced, removed, or modified to increase diversity. C) Flavonoid families. D) Example of a tetrameric procyanidin, galloylated at the second procyanidin residue. Names of the monomeric form of each subunit are presented in parenthesis.

Early reports describing effects of both procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins in rats suggested the compounds were carcinogenic.80 When injected subcutaneously, these tannin preparations induced hepatomas, cholangiomas, liver tumors and sarcomas.81 Unfortunately, these studies were performed with heterogeneous and undefined mixtures of tannins. This broad categorization of all tannins undoubtedly obfuscated studies on these plant metabolites. Recent studies refuted the reports of tannin carcinogenicity,82 further, cancer preventative properties of some tannins have been reported.83 Additional studies describe the incredibly diverse biochemical functions of individual tannins in both the plant and on mammalian systems. Thus, current efforts are aimed at describing the biological activities of individual tannins in an effort to identify novel health benefits.

B. Polyphenol Classification

Polyphenols are catabolized from phenylalanine using the phenylpropanoid pathway.84 This pathway provides many options to plants for generating chemical diversity. Polyphenol production varies greatly in different plants, some polyphenols such as lignin are produced universally, however other polyphenols may be restricted to specific families or species.85;86 Each class of polyphenol is associated with specific functions in the plant ranging from scaffolding to host defense.

1. Lignin

Lignin is an important component of the plant cell wall and is the most abundant organic polymer after cellulose.87 Lignin forms a heterogeneous structure (Fig. 1A) and acts in both the maintenance of the structural integrity of the cell wall, as well as a scaffold for polysaccharides. The polysaccharides increase the hydrophobicity of the lignin structure, which facilitates water transport throughout tissues by preventing water absorption. This hydrophobic structure is crucial for capillary action, which allows water to pass through the lignin-lined capillaries without absorbing into plant cells.88;89

2. Hydrolysable tannins

Hydrolysable tannins contain a sugar core surrounded by phenolic groups such as gallic acid residues. These residues can be subsequently modified by further addition of phenolic groups, oxidation reactions, or other polyphenols,90;91 thereby generating increasingly complex polyphenols. Hydrolysable tannins are so named because treatment with weak acids readily hydrolyses the gallic acid residues and produces phenolic acids with a carbohydrate core.92 It is currently debated what role hydrolysable tannins play in plant biology. However, the production of diverse hydrolysable tannin structures suggests they are employed in specialized functions.93 One indicated use of hydrolysable tannins in plant defense is as toxins to prevent herbivore predation, although characterization of these responses requires further study.94 Most studies regarding the function of hydrolysable tannins are focused on their effects in mammalian biology. Hydrolysable tannins show potential for therapies such as anti-cancer or anti-hypertensive agents.95

3. Procyanidins and other flavonoids

Flavonoids are a type of tannin that comprise over 7,000 described chemical entities with diverse activities.74;96 Species from all orders of the plant kingdom, from the most simple to the most advanced, invest heavily in the production of flavonoids,74 suggesting the importance of these molecules to plant biology. Flavonoids are generally divided into chemical families including flavones, flavonols, anthocyanidins, procyanidins, and isoflavonoids. The basic flavonoids all contain very similar three-ring structures (Fig. 1C), which can be modified by the plant to produce a wide variety of phenol-rich rings with a diverse repertoire of functions. Numerous flavonoids structures can be formed by the addition or modification of flavonoid subunits, affording the plant with the potential to produce unique metabolites of various size and function.

The flavonoids can be classified into two functional groups, the colored and the colorless. The colored flavonoids, which are predominantly anthocyanidins, are typically present at the surfaces of flowers and leaves. These flavonoids add appropriate colors to aid in attracting pollinators97 and also prevent insect predation since red is outside the visible spectrum for most insects.98 Additionally, colored flavonoids prevent UV-induced cell damage.99 The colorless family of flavonoids are so named because their function is not dependent upon their light emission and are not necessarily colorless; in fact, they often appear yellow when purified.74 The colorless flavonoids also play a role in UV protection in the plant,100 but have a number of additional functions including mitigation of temperature stress,101;102 heavy metal tolerance,103 reduction of oxidative stress,104 root nodule formation (nitrogen fixation),105 mycorrhizal development (nutrient uptake),106 fungal and bacterial pathogen resistance,107 seed integrity,108 regulation of seed dormancy,109 phytohormone transport,110 regulation of gene expression,111 and toxic prevention of predation.112 Thus, these assorted flavonoid structures clearly demonstrate diverse biological activities.

Of the colorless flavonoids, procyanidins represent a major fraction in both function74 and content113;114 of many plant tissues. The procyanidins are produced by assemblage into oligomers; up to 28-mers of procyanidins have been recorded.115 These oligomers are formed via combinations of the monomer subunits epicatechin or catechin, and are often modified by the addition of gallic acid residues. In grapes, for example, about 20% of the residues are galloylated.115 By utilizing different procyanidin subunits and galloylation (Fig. 1D), oligomeric procyanidins are capable of generating a potential structural diversity reaching into the millions. This capacity for structural diversity suggests the potential for functional diversity as well. Procyanidins, as well as hydrolysable tannins, are able to bind proteins with high affinity via charge-charge interactions with their polyphenolic nuclei. These polyphenolic nuclei interact most strongly with hydrophobic residues, such as proline.116 As such, tannins aid in the defense of plants by precipitating salivary proteins resulting in a dry taste and preventing consumption by both insects and animals. Tannins also have a bitter astringent taste that is associated with high-tannin foods such as non-ripe fruit, grape skins, and strong teas. In addition to binding and precipitating salivary proteins, tannins often demonstrate a high affinity for other proteins in the mammalian system.117–119 These interactions are currently being investigated. Evidence suggests that tannin species may account for some of the historic use of many plant extracts for medicinal benefit by their ability to bind specific proteins and induce immune responses.

C. Health Benefits Attributed to Procyanidins and Hydrolysable Tannins

In addition to studying tannin functions in the plant, a large amount of work is concentrated on the effects of both procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins on mammalian systems (Table 2). In fact, a current literature search yields more studies citing the effects of tannins on non-plant species than on description of function in the plants themselves. Similar to the diverse activities in the plant, tannins also demonstrate a wide range of health benefits to mammals including anti-oxidant, anti-pathogen and anti-cancer activities, as well as immunostimulatory effects.120 Due to advances in tannin chemistry and a greater understanding of polyphenol complexes, we are becoming increasingly aware of how tannins impact the mammalian system.

Table 2.

Procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins with characterized health benefits

| Botanical name |

Common name | Use in traditional medicine |

Mode of action | Active component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinium oxycoccus | Cranberry juice | Urinary tract infection | Prevent bacterial colonization252 | Procyanidins253 |

| Magnolia lilflora | Magnolia tree | Antihypertensive, Allergies** | Angiotensin converting enzyme | Procyanidins and hydrolysable tannins254 |

| Kola acuminata | Kola nut | Treatment of parasitic disease | Toxic to Trypanosoma brucei brucei | Oligomeric procyanidin255 |

| Terminalia arjuna | Terminalia | Wound healing Blood pressure*, ** | Epithelial regrowth | Tannin extract 256 |

| Woodfordia fruticosa | Fire Flame Bush | Numerous* | Topoisomerase II inhibitor | Woodforin C257 |

| Vitis vinifera | Red wine | Solvent for many herbs*, ** | Vasodilatation | Procyanidin258 |

| Phyllanthus urinaria | Chamberbitter | Numerous* | Inhibit Herpes simplex 1 and 2 infection | geraniin259 |

| Arbutus unedo | Strawberry tree | Hypertension | Decreases thrombin-induced platelet aggregation | Tannin extract260 |

| Vitis vinifera | Grape seed | Not directly observed | Assists in tumor killing | Procyanidin261 |

| Paeonia lactiflora | Peony | Numerous** | Inhibit nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase activity | 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloylbeta- D-glucose262 |

The large collection of three-dimensional structures formed by tannins results in highly active and unique molecular species that interact with plant, commensal organisms, and predator molecules to generate these diverse functions. Furthermore, many of the tannins that are biologically active in the plant are often biologically active in mammalian systems since there are many shared biochemical pathways and structures.121–123 Some positive effects tannins have in mammals include resolution of urinary tract infections, anti-cancer effects (chemotherapeutics), and reduction of blood pressure (Table 2). Interestingly, the majority of these discoveries have occurred within the last decade,124–133 indicating that research into the direct effects of tannins, in particular individual, select tannin species, has only recently begun.

Many tannin preparations with immune health benefits have been described for the treatment of both disproportionate inflammatory diseases and in the clearance of infections. This indicates these plant compounds have both pro- and anti-inflammatory functions. For example, pine tree tannin alleviates inflammation in chemically induced inflammatory models,134 yet promotes inflammation in response to infection.135;136 Studies on tannins from non-ripe apple peel polyphenols (APP), grape seed, and cocoa demonstrate a similar ability to augment both pro-inflammatory137–139 and anti-inflammatory140–142 responses. We propose that this contradiction may be a result of tannin-induced improvement of γδ T cell-directed regulation of inflammation.

D. Regulation of the Mucosal Inflammatory Response by Select Tannin Preparations: Implications of a γδ T cell agonist component in traditional medicines

The inflammatory response functions to recruit necessary cells to sites of infection for removal of infectious agents. This response must be tightly regulated to eliminate the infectious agent, but not damage host tissue. Maintaining the inflammatory response is particularly crucial in the intestinal mucosa as excessive inflammatory responses result in damaged mucosal surfaces143 and may lead to the development of the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohne’s disease and ulcerative colitis.143–145 γδ T cells are important mediators of the intestinal immune balance and comprise up to half of the lymphocytes in the gut.146 Increasing the function of these mucosal γδ T cells may represent a mechanism of novel therapeutics for enhancing host innate and downstream adaptive immune responses.147

IBDs are complex autoimmune diseases characterized by chronic relapsing intestinal inflammation. Current therapies for IBD are not always effective for modulating the inflammatory responses. Furthermore, these therapies have numerous side effects including increased risk of pancreaitis, opportunistic infections, endocrine imnpairment, lymphoma, and liver or lung fibrosis. If the colitis is severe enough, surgery is required to remove the affected area148. Therefore increasing the γδ T cell regulatory effects in the gut are a favorable treatment option. Recent evidence indicates intraepithelial (IEL) γδ T cells are vital in maintaining gut integrity149–151 and increasing the regulatory function of the γδ T cell population resident in the gut may alleviate IBD symptoms.152

γδ T cells of the gut mucosa act, in part, by repairing damaged epithelia153–155 and regulating inflammation156. Murine γδ T cells of the gut and skin secrete growth hormones in response to damaged or stressed epithelial cells, namely keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)157 and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1).158 γδ T cells have also been shown to directly regulate the inflammatory state in tissues by secreting opposing cytokines or inducing apoptosis in pro-inflammatory cells. A similar role for γδ T cells in the epithelium repair of humans may be implied by the significant increases in KGF production159 in patients with IBD. Interestingly, a recent analysis of genome scans in individuals with IBD has identified a number of susceptibility genes of which the IL-17 pathway is commonly disrupted in IBD patients. As γδ T cells are often the predominant source of IL-17,160 these results indicate IBD patients may suffer from a γδ T cell dysfuntion. The intricacies of IL-17 function and it’s production in the gut by γδ T cells remain unknown, however, the parallels between γδ T cell regulatory function, IL-17 production, and IBD disease states are worthy of detailed investigation.

In addition to IBD,161 numerous diseases associated with a dysregulated inflammatory response implicate impaired γδ T cell function in the disease. These diseases include allergies162, asthma163, and autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis164 or lupus.165 It has been proposed that increasing γδ T cell function and thereby regulation of inflammation and repair of damaged epithelia, may alleviate some of these disease symptoms.166

As tissue-associated γδ T cells are prominent mediators of inflammatory homeostasis the recent evidence describing the γδ T cell response to procyanidins167;168 supports much of the anecdotal evidence for plant preparations maintaining this equilibrium. Additionally, flavonoids are characterized with IBD-relieving activities169, and this may be, in part, through modulating γδ T cell activities. These recent results suggest that procyanidins may impart relief from numerous inflammatory dysfunctions, without the side-effects of cytokine therapy, by increasing the regulatory function of the mucosal γδ T cell.170;171

E. Immune responses to γδ T cell-active procyanidins

Unlike the prenyl pyrophosphate agonists, which, directly and exclusively, stimulate Vδ2 γδ T cells, the immune response to procyanidins is more ubiquitous. Our work with oligomeric procyanidins from APP demonstrated activity in both peripheral and mucosal γδ T cell populations.172 In addition, a large subset of NK cells and a small subset of αβ T cells respond to these agonists.173 B cells do not proliferate in response to APP and IL-2 culture, but they do up-regulate CD69 expression in response to APP alone (data not shown). Similarly, procyanidins from cocoa activate B cells.174 The shared response among subsets of NK cells, γδ T cells, and αβ T cells indicates active procyanidins do not signal through the TCR, but rather through a mechanism common to subsets of these cell types.

IV. PLANT TANNINS INDUCE RAPID TRANSCRIPTION OF SELECT CYTOKINES AND SURFACE RECEPTORS IN γδ T CELLS: CHARACTERIZATION OF TANNIN-INDUCED PRIMING OF γδ T CELLS

Recently, we have characterized a semi-activated state, termed priming, of γδ T cells. This priming state allows for a more rapid response to secondary stimuli that includes antigen, cytokines, or other types of agonists. This priming state is identified by an increase in activation-related surface markers, notably IL-2Rα, and a select number of cytokines including GM-CSF, IL-8, and IL-2, among others, without an of overt inflammatory immune response characterized by cell expansion and IFNγ production. In this state, the γδ T cell is better able to respond quickly to secondary stimuli such as IL-2 or TCR engagement. This phenomenon is observed in all species tested (bovine, human, and mouse).175;176

A. Plant tannins induce γδ T cell priming

We have identified plant tannins as priming agents for γδ T cells. Our initial studies on these tannins utilized procyanidins from APP and Cat’s Claw bark; however, other procyanidin sources with published responses similar to these tannins, such as grape seed, were tested and their activity confirmed (unpublished observations), indicating the existence of additional sources of γδ T cell-priming procyanidins. As with other priming agents, plant tannins increase the surface expression of IL-2Rα on γδ T cells, but induce relatively little proliferation by themselves.177 The functional significance of increased IL-2Rα expression is observed in vitro after addition of IL-2 or IL-15, as secondary stimuli, which induce a two-to four-fold increase in γδ T cell proliferation versus non-procyanidin-treated cultures.178

Comparison of human immune cell subsets in experiments designed to measure in vitro proliferation in response to APP with IL-15 indicated that NK cells are the most responsive, as 55% of the total NK cell population proliferated.179 Additionally, proliferation is observed in other cell populations including Vδ1 T cells (28%), Vδ2 T cells (18%) and αβ T cells (18%).180 The preferential response of tissue-associated γδ T cells is also observed in bovine cultures.181 A distinct increase in IL-2Rα on the majority of Vδ1 T cells indicated most of these cell become primed, but are not induced to proliferate in response to IL-15.182 Thus, although only 28% of the Vδ1 T cells proliferate in response to IL-15 as a secondary stimulus, the majority of Vδ1 T cells become primed in response to APP. In contrast, the expression of IL-2Rα on Vδ2 T cells is consistent with proliferation of only a subset of cells, as only 26% of the population increases IL-2Rα expression following APP culture.183 APP-primed γδ T cells from human peripheral PBMC cultures respond to IL-2 or IL-15,184 but also demonstrates an increased proliferative response to TCR agonists indicating that primed γδ T cells are also more responsive to other forms of secondary stimuli.185

B. Gene and protein expression profiles of tannin-primed γδ T cells

In addition to increased expression of IL-2Rα, we have identified other changes in primed γδ T cells. We performed a microarray study in which we examined the gene expression profile of bovine γδ T cells treated with APP or with PBS as a control (Daughenbaugh, K. et al., manuscript in preparation). We identified many transcripts whose expression was significantly increased in response to APP, including the myeloid growth factor GM-CSF and the chemoattractant IL-8, in addition to other cytokines with defined roles in innate immunity, and the activation marker CD69.186;187 The γδ T cell response is also characterized by increased expression of the adhesion molecule CD11b.188 Of the three species observed to respond to procyanidin agonists, the priming response is most significant in murine γδ T cell populations (Freedman et al., manuscript in preparation).

To assess the in vivo relevance of the gene expression changes observed in vitro, APP was injected intraperitoneally in mice, which induced rapid neutrophilia and migration of neutrophils into the peritoneum of BALB/c mice. In contrast, migration of neutrophils into the peritoneum of CXCR2-deficient mice on the same genetic background did not occur following APP injection. These results suggested a critical role for expressed chemokines (GM-CSF, and CXCL1/KC, the IL-8 equivalent in mice) in this model. Stimulation of γδ T cells by procyanidins could be responsible, at least in part, for the observed neutrophil migration and potentially for immunoregulatory responses at the tissue level (Daughenbaugh et al., manuscript in preparation).189 This is emphasized by the absence of prominent pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα or IFNγ190 in populations treated with procyanidins, also a component of the priming model. TNFα and IFNγ production is strongly associated with prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation,191 consistent with the dissimilar γδ T cell responses to these agonists. Thus, the conserved priming response of γδ T cells to tannins may represent a possible mechanism for the observed immunological benefit of dietary supplements and herbal remedies containing them.

C. Procyanidins increase the stability of select mRNA species

Investigation into the mechanism leading to the rapid priming of γδ T cells is warranted in the context of medicinal therapeutics, as it could aid in the identification of other plant tannins or compounds that result in similar effects. Messenger RNA encoding both GM-CSF and IL-8 contain structures in their 3’UTRs that dictate their stability, therefore we chose to investigate whether the stability of these mRNAs was altered in response to treatment with procyanidins. The γδ TCR-expressing human cell line, MOLT-14, produces GM-CSF and IL-8 following APP treatment, consistent with the response of primary cells. Using this cell line, we found that the half-lives of both mRNAs were significantly increased in cells treated with procyanidins as compared to those treated with TNFα. This suggests a possible mechanism through which GM-CSF and IL-8 protein expression is immediately triggered upon secondary stimulation. This increased half-life is, in part, a result of signaling through the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway, though the possibility exists that other pathways could be important in this process (Daughenbaugh et al., manuscript in preparation). It remains to be seen how other tannins or plant-derived molecules influence the stability of mRNA species related to the priming process, and if this stabilization can be exploited to further augment the priming abilities of γδ T cells or other cell types.

V. γδ T CELL RESPONSES TO PROCYANIDINS IN THE INTESTINAL MUCOSA

Due to the responsiveness of the mucosal γδ T cell population to procyanidins, and the reported immuno-modulatory effects in the numerous procyanidin-containing herbal remedies, we have focused on the mucosal γδ T cell response to these agonists. In vitro analyses of circulating γδ T cell subsets responses to procyanidins indicate an increased responsiveness in the mucosal γδ T cell population. Coupled with reports on the safety of oral administration in mice, rats, and the long term use of APP as a nutritional supplement, these initial studies indicate procyanidins may be a favorable agonist for this mucosal lymphocyte population.

A. Mucosal γδ T cell responses to plant procyanidins

Tissue-associated γδ T cells in mouse (IEL γδ T cells192), human (peripheral Vδ1 T cells), 193 and bovine (peripheral CD8+ γδ T cells)194 respond more robustly to procyanidins than peripheral-associated γδ T cells. Importantly, there are limited agonists for the intestinal mucosa and the only other class of plant γδ T cell agonists, prenyl pyrophosphates, do not affect this population. The functional relevance of priming of the major portion of human mucosal γδ T cells has not been directly observed in the tissues, but work in rodent models indicates the potential effects of a primed mucosal γδ T cell population. Studies using both mice and rats further support the in vitro data demonstrating the response of the mucosal γδ T cell. Specifically, the mucosal γδ T cell population expands in both the intestinal IEL and Peyer’s patch populations after oral administration of procyanidins.195;196 The first group to report this observation noted an increase in concentration of γδ T cells of the intestinal mucosa in mice fed APP.197 In the second study an increase in intestinal γδ T cells and decreased production of secretory IgA was observed in rats fed cocoa.198 γδ T cells have been implicated in regulation of IgA production in the intestinal mucosa,199–201 and may be responsible for this observation.202 Although we have not yet directly tested cocoa, it contains at least one γδ T cell-active procyanidin found in APP.203 Finally, other reports on procyanidins may be attributed to increases in tissue-specific γδ T cell function. For example, when applied topically, APP demonstrates an improved rate of hair regrowth.204 As γδ T cells are found near the hair follicle during growth cycling stages, they may impart a regulatory function which is improved by procyanidin application.205 Confirmation of this, however, will require additional studies. Together with the mounting evidence for the importance of γδ T cells in maintaining the intestinal epithelia, we believe the effect of tannins on mucosal γδ T cells suggests a potential mechanism of immune stimulation for supplements which contain procyanidins and could possibly be applied to the development of therapeutic drugs.

B. Toxicology studies on oral administration of procyanidins

The effective dose range of APP required to induce IL-2Rα expression on γδ T cells in vitro under serum-free conditions is quite limited (1 to 40 µg/mL for bovine cells206 and 1 to 20 µg/mL for human cells207); this restricted dose range is likely due to the induction of apoptosis at higher concentrations, and is consistent with other tannin preparations.208 These in vitro data suggest a relatively narrow therapeutic and non-toxic range for procyanidins. However, in vivo studies in rats and mice demonstrate that this toxicity is attenuated by the gut; in that high-dose oral administration of procyanidins does not induce the toxic effects observed in vitro. For example, APP administered to mice ad libitium in their drinking water at 1% w/v, which leads to expansion of γδ T cells in the intestinal mucosa, does not induce obvious toxicity.209 Furthermore, when APP is given orally to rats at concentrations up to 2,000 mg/kg, all animals survive, gain body weight, and overt inflammation of the intestinal mucosa or any other organ is not observed over a 14-day period.210 This dose is equivalent in adult humans, as calculated by body surface area211, to ingesting 324mg/kg of APP, 1.4L/kg of black tea,212 or eating 292g/kg of unprocessed apple peel.213 Current dosing recommendations for APP as a nutritional supplement are 1g/day, indicating human consumption is safe at more than ten times higher concentrations than the recommended dose.

The lack of toxicity seen following ingestion of high doses of tannins are not toxic, which is likely due to regulation of tannin uptake by the intestinal mucosa, thereby preventing toxic levels from entering the bloodstream. Specifically, plasma uptake of tannins in rats plateaus at 10.2 µg/mL (1,000 mg/kg oral dose) and does not increase when rats are fed 2,000 mg/kg of a tannin preparation.214 This limited transfer of procyanidins into the serum indicates oral administration may naturally restrict procyanidins to the intestinal mucosa, and thus may have only minor effects on the peripheral immune system (however, 10ug/mL in the blood would likely be sufficient to drive γδ T cell responses.215) Furthermore, it appears that smaller procyanidins, which appear to be not as effective as agonists,216 are more effectively resorbed in the intestine.217 Finally, procyanidins bind to serum proteins,218 thus decreasing their activity. This is also observed during in vitro culture with serum-containing medium, wherein cultures containing serum require far more tannin to achieve activation levels comparable to serum-free culture. In fact, some responses can be blocked by the addition of serum to the culture (unpublished observations). For these reasons, γδ T cell responses to procyanidins are likely most relevant for intestinal cells and may be used as a potential therapy for inflammatory imbalances such as Crohn’s disease or persistent infections of the intestinal tract.

VI. ISOLATION OF γδ T CELL ACTIVE TANNINS

The crude APP preparation is comprised of approximately 95% polyphenols, of which tannins constitute 90%.219 Through isolation strategies, we confirmed the procyanidin fraction as the active component.220 Furthermore, we tested this fraction to assure there was not a known γδ T cell agonist contaminating the tannin fraction. As γδ T cells express PAMP receptors and recognize the prenyl pyrophosphates, we performed experiments to remove these potential contaminants. These procedures did not alter the cellular response to the extract and confirmed the lack of TLR agonists in the tannin preparation.221

Although this initial characterization of the γδ T cell response confirmed the active components as procyanidins, the range of procyanidin sizes in these preparations continued to complicate our studies. Therefore, we have begun steps to purify procyanidin oligomers by chain length. Many partially purified and isolated procyanidin preparations demonstrate agonist activity similar to the original, crude APP extract, further confirming the biological activity in APP is a select population of procyanidins.

A. HPLC Fractionation of γδ T cell-active procyanidin preparations

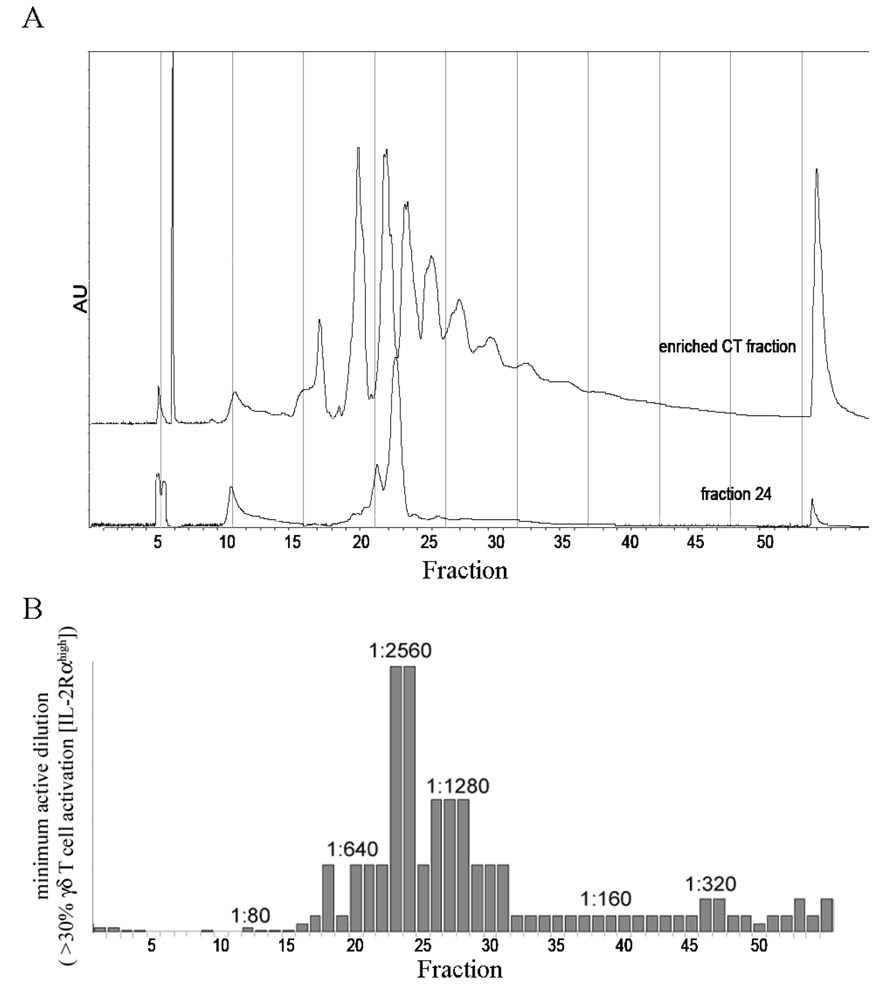

We began fractionation procedures to isolate the γδ T cell active component from APP. We selected APP for these experiments as it contained the most procyanidins and a very low amount of endotoxin contamination.222 For our initial fractionation studies, we enriched for oligomeric procyanidins.223 This was performed using an LH-20 column with selective MeOH/acetone elutions as previously described.224 Next, this enriched fraction was separated by normal phase HPLC (Fig. 2A). The peaks, from left to right, represent increasing procyanidin oligomers.225 These fractions were assayed for their ability to induce γδ T cell priming within bovine PBMC cultures (Fig. 2B). The most active fractions, 23 and 24, approximately corresponded to trimeric or tetrameric procyanidins. The γδ T cell specific activity of fractions 23 and 24 was additionally confirmed using human PBMCs from two donors (data not shown). Due to the wide range of procyanidins in APP that retained a γδ T cell specific activity, we hypothesized that there was a common structure represented in all active procyanidins. Therefore, we tested purified, commercially available procyanidins for γδ T cell activity.

Figure 2. HPLC Fractionation of Procyanidins.

HPLC fractionation of procyanidins from APP confirms the oligomeric nature of the active procyanidin fraction. The enriched oligomeric procyanidin preparation was fractionated by normal phase HPLC. A, Absorbance profile @ 280nm for the initial, procyanidin fractionation and the biologically active fraction, #24. B, Expression of bovine IL2Rα was measured in the presence of fractions obtained from the HPLC separation. Data represent the lowest dilution of each fraction in medium required to achieve 30% activation. These results are representative of activity from two HPLC fractionations.

B. γδ T cell responses to individual procyanidin species

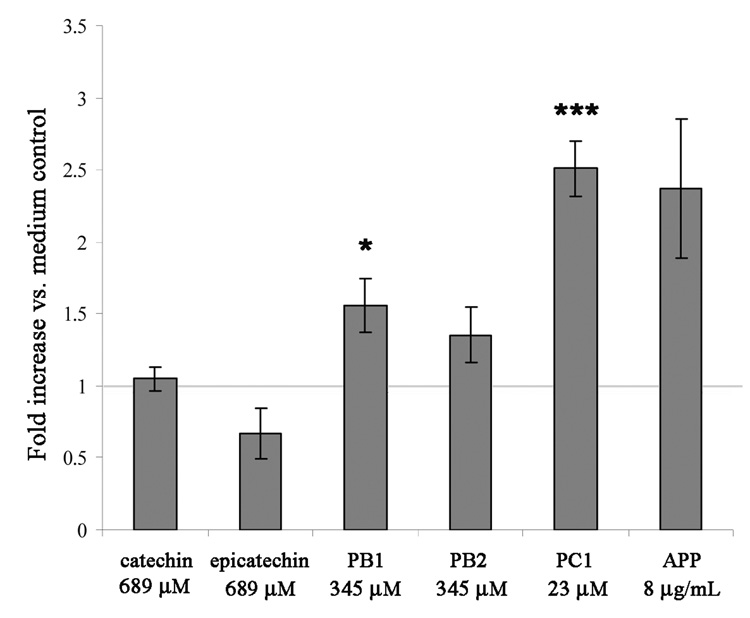

Commercially available procyanidin components common to APP226;227 were tested for biological activity by measuring proliferation in cultures with human PBMCs. Although slight activity was observed in cultures treated with dimeric procyanidins, the most active procyanidin was the trimeric procyanidin C1 (PC1). PC1 was active at lower concentrations than the monomeric or dimeric compounds. (Fig. 3). Tetrameric and higher order procyanidins were not commercially available, but likely retain activity (Fig. 2B). Larger oligomer fractions, separated by HPLC, on a weight basis are equivalent or more active than the total APP preparation (unpublished observations). Unfortunately, large oligomers are notoriously difficult to isolate.228 In addition to the known procyanidin constituents of APP,229;230 we tested other monomeric flavonoids including epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), gallocatechin gallate (GCG), catechin gallate (CG), epicatechin gallate (ECG), epigallocatechin (EGC), theaflavin-3,3’–digallate, silychristin, rosmarinic acid, hamamelitannin, granatin B, and cicoric acid. None of these compounds induced significant human or bovine γδ T cell activation (unpublished results). To confirm that the activity of purified PC1 was similar to the APP preparation, we performed FACS analysis comparing responses in αβ T cell, γδ T cell, NK cell and B cell populations from a human PBMC culture. CD69 expression was used as a marker for activation, and was similar for both APP and PC1 in all subsets (data not shown), thereby confirming retention of activity in the commercial procyanidin, PC1. Thus, PC1, and likely higher order oligomers, but not smaller structures, retained the most robust activity on human cells. In contrast, mouse γδ T cells were less restricted in their recognition of these structures and responded to dimeric procyanidins, and under some culture conditions, to monomeric procyanidins; albeit, PC1 remained the most effective procyanidin tested. (Freedman et al., manuscript in preparation).

Figure 3. Purified Procyanidin Dimers and Trimer Induce Human γδ T Cell Proliferation in response to IL-15.

Human PBMCs from 3 donors were CFSE-labeled and cultured with IL-15 (1 ng/ml) and either APP, catechin (Axxora, San Diego, CA), epicatechin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), procyanidin B1 (PB1; Extrasynthese, Genay France), procyanidin B2 (PB2; Extrasynthese, Genay France), PC1 (Phytolab, Vestenbergsgreuth, Germany), or medium only. Dilutions of procyanidins or APP inducing peak responses were selected and compared for their γδ T cell proliferative ability. Data represent the average fold increase of γδ T cell proliferation in the procyanidin-treated samples versus the medium control (1 ng/ml IL-15) wells. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. P-values for differences in means are *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

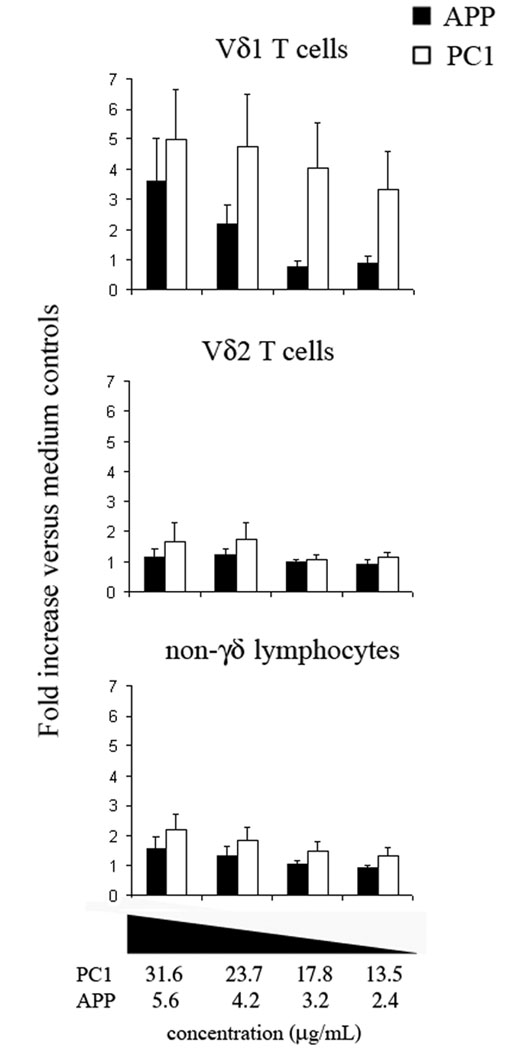

A detailed analysis of human γδ T cell subsets in response to PC1 or APP was also performed. For these assays, human PBMCs were cultured with differing concentrations of the procyanidin extracts. The cultures were analyzed for both activation and cell survival. Perhaps more so than seen with the APP-treated cultures, PC1 preferentially activated the Vδ1 population (Fig. 4). These preliminary results indicated that PC1 was less toxic than APP at the effective agonist concentration. This effect was presumably due to the removal of tannins lacking γδ T cell-specific activities that induced cell death in the crude APP tannin preparation.

Figure 4. At non-toxic concentrations, PC1 is a better Vδ1 agonist than APP.

Human PBMC cultures were maintained for 48h with various concentrations of PC1 or APP under the conditions previously described.266 After the culture period, cells were stained with mAbs to Vδ1 TCR, Vδ2 TCR, and CD69 then analyzed by flow cytometry. Cultures not inducing toxicity were analyzed. Toxic cultures were determined by flow cytometry light scatter (FSC/SSC). Cultures with a ratio of healthy lymphocytes to cellular debris less than medium controls were eliminated. Maximum concentrations for baseline cell survival were 31.6 µg/mL and 5.6 µg/mL for PC1 and APP, respectively. Values represent the average fold increase in CD69+ cells compared to the medium controls for four donors. Error bars represent SEM.

HPLC separation of the APP oligomeric procyanidins and subsequent analysis in culture indicated there are larger species of procyanidins with biological activity on γδ T cells. This was indicated by increases in IL-2Rα expression in fractions representing larger oligomers (Fig. 2B). These experiments have been repeated and the fractions analyzed by mass spectrometry to confirm additional species with γδ T cell agonist activity in the, presumably, trimeric through octomeric fractions (data not shown). This indicates procyanidin activity is not limited to only one chemical species, but suggests a common structure in multiple procyanidins. Using PC1 as a model structure, we have begun testing synthetic compounds for human γδ T cell agonist activity.

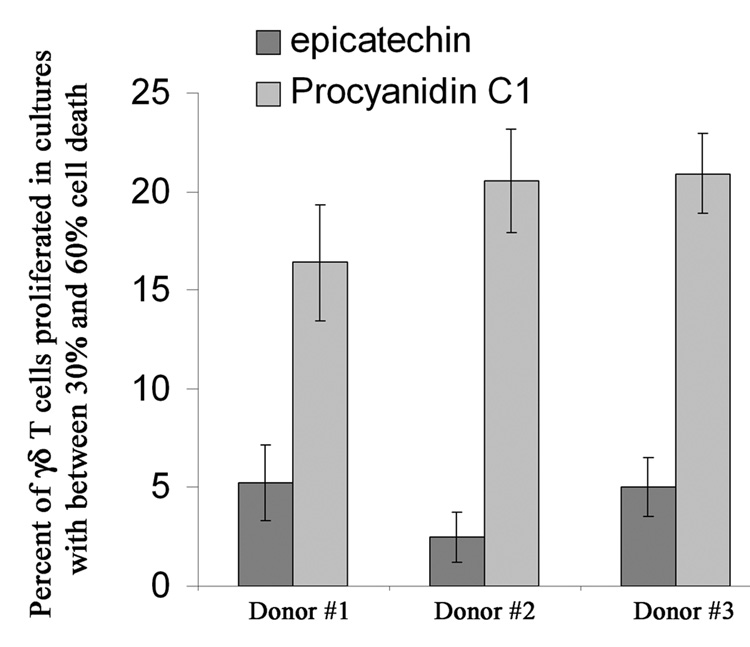

C. Cellular stress induced as a common response to monomeric epicatechin or PC1 does not account for the γδ T cell response

Tannin preparations induce apoptosis in cell cultures and NK and γδ T cells share surface receptors that recognize cellular stress.231 Ligation of these stress receptors induces similar activation profiles to those seen with procyanidins,232 therefore, we examined the potential for tannin-based responses to be due to γδ T cell and NK-recognized cell stress. Initially, we tested for a correlation between expression of the stress-inducible ligand, NKG2D, and tannin recognition. No significant correlation between γδ T cell or NK cell activation and NKG2D expression was identified (unpublished results), however many other surface markers for recognition of cellular stress exist and are likely shared by γδ T cells and NK cells. Therefore to conclude that the response was not due to general tannin-induced cell stress and recognition from alternative stress receptors, we compared cell activation in cultures treated with semi-toxic concentrations of PC1 or the monomeric procyanidin epicatechin. Specifically, we cultured human PBMCs at tannin concentrations that induced equivalent toxicity in the total cultured cell population (between 30 and 60% toxicity as determined by FACS). Under semi-toxic conditions, PC1-treated cultures induced human γδ T cell activation whereas epicatechin-treated cultures did not. Thus confirming the activation of γδ T cells and NK cells by procyanidins was not due to its induction of cellular stress in in vitro cultures.

Concluding remarks

γδ T cells mediate many immune functions, which could potentially be manipulated for medicinal purposes. Their roles in preventing and clearing cancerous cells have led to the use of prenyl pyrophosphate agonists in clinical trials. However, the use of prenyl pyrophosphates as agonists has limitations since they show limited effectiveness in repeat treatment233;234 and are less effective in individuals with persistent infections.235–237 Furthermore, they selectively stimulate the circulating and not the tissue γδ T cell population. For these reasons, it is of interest to identify other, distinct γδ T cell agonists that could potentially be used as therapeutics. Plants are a common source of γδ T cell agonists. This is observed by the numerous different vegetable, fruit, and other plant extracts demonstrating γδ T cell agonist activity.238 Although many other plant agonists are currently being studied, procyanidins are particularly interesting as they stimulate the mucosal γδ T cell population. Importantly, oral administration of oligomeric procyanidins is likely to be very selective for the mucosal γδ T cell population - a population currently not specifically targeted by therapeutic treatments.

Plant-derived γδ T cell procyanidin agonists are found in a limited number of plants. Of the many plants screened, only two sources were confirmed to impart γδ T cell agonist activity from their tannin fractions. However, subsequent literature searches on biologically active procyanidins have identified other procyanidin-rich extracts with similar biological activity. These include pine tree, cocoa, and grape seed extracts, all of which have been used in traditional medicine.239–241 Interestingly, grape seed,242 cocoa,243 and probably pine244 also contain PC1. We predict that these and other procyanidin-rich extracts will impart the same γδ T cell responses as defined for apple-derived procyanidins. In support of this premise, we recently found that grape seed extract has potent γδ T cell agonist activity. Though we have not yet tested it, cocoa extracts expand rat γδ T cells in vivo,245 similar to the expansion observed in response to apple-derived procyanidins.246 These increases in γδ T cells of the intestinal mucosa are a functional demonstration of the in vitro priming responses in the mouse (Freedman et al., in preparation) and indicate human and bovine mucosal γδ T cells, which likewise become primed by procyanidins in vitro, may also expand in vivo.

Identification of γδ T cells as a significant responding cell to many procyanidin-containing preparations may explain the contradictory findings of many traditional medicines that are able to be both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory. The procyanidin-induced priming state induces a subtle phenotype upon these cells, categorized by an increased responsiveness to secondary stimuli and the absence of overt inflammatory mediators. Due to the dual nature of the mucosal γδ T cell population, this primed state may enhance either the pro- or anti-inflammatory activity depending upon the secondary stimulation.

Although many molecular mechanisms of γδ T cells have yet to be described, their regulatory role within the mucosal immune system is well defined.247–249 This ability to regulate the immune response at mucosal surfaces imparts a critical role for γδ T cells in preventing infection by acting as recruiting agents for inflammatory cells and by maintaining the epithelial integrity via suppression of unchecked inflammation. The induction of a priming state in these cells may allow a more potent and rapid response to infectious agents or other secondary stimuli. By utilizing priming agents such as procyanidins, the activation of γδ T cells has potential applications for increasing general mucosal immune responses during disease outbreak. Additionally, procyanidins may possibly be used in conjunction with mucosal vaccines to improve vaccine efficacy or in combination with antibiotics to treat persistent infections.

Figure 5. γδ T cell Activation Cannot be Explained by Procyanidin-induced Cell Death.

Semi-toxic concentrations of PC1, but not its monomeric subunit, induce γδ T cell proliferation. CFSE-labeled human PBMCs were cultured with IL-15 (1 ng/ml) and medium alone or various concentrations of purified epicatechin or purified PC1 for 5 days. Cultures were analyzed for lymphocyte survival by light scatter (FACS) where the maximum survival was medium only. Cell cultures between 30–60% lymphocyte death were analyzed for γδ T cell proliferation. Bars represent the AVG γδ T cell proliferation and SD from each of the 3 cultures found to induce this range of cell death in culture.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN266200400009/N01-AI40009, NIH/NCCAM P01-AI004986-01, NIH COBRE supported FACS facility, and the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Critical Reviews in Immunology (CRI). Begell House Inc., publisher of CRI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. The manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by CRI; hence it may differ from the final version published in CRI (online and print). Begell House Inc. (CRI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the United States National Institutes of Health or any third party. The final, citable version of this record can be found at: http://www.begellhouse.com/journals/2ff21abf44b19838.html.

Disclosures

M. A. Jutila holds shares in LigoCyte Pharmaceuticals Inc., which together with Montana State University, holds a National Institutes of Health contract that partially funded the work presented in this article.

Reference List

- 1.Summer J. The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press; 2000. pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lietava J. Medicinal plants in a Middle Paleolithic grave Shanidar IV. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;35(3):263–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90023-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Beutler JA, McCloud TG, Loehfelm A, Yang L, Dong HF, Chertov OY, Salcedo R, Oppenheim JJ, Howard OM. Tannic acid is an inhibitor of CXCL12 (SDF-1alpha)/CXCR4 with antiangiogenic activity. Clin.Cancer Res. 2003;9(8):3115–3123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tokura T, Nakano N, Ito T, Matsuda H, Nagasako-Akazome Y, Kanda T, Ikeda M, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Nishiyama C. Inhibitory effect of polyphenol-enriched apple extracts on mast cell degranulation in vitro targeting the binding between IgE and FcepsilonRI. Biosci.Biotechnol.Biochem. 2005;69(10):1974–1977. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graff JC, Jutila MA. Differential regulation of CD11b on gammadelta T cells and monocytes in response to unripe apple polyphenols. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(3):603–607. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagerman AE, Butler LG. The specificity of proanthocyanidin-protein interactions. J Biol.Chem. 1981;256(9):4494–4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frazier RA, Papadopoulou A, Mueller-Harvey I, Kissoon D, Green RJ. Probing protein-tannin interactions by isothermal titration microcalorimetry. J Agric.Food Chem. 2003;51(18):5189–5195. doi: 10.1021/jf021179v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton JE, Cruickshank SM, Egan CE, Mears R, Newton DJ, Andrew EM, Lawrence B, Howell G, Else KJ, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Smith JE, White SJ, Carding SR. Intraepithelial gammadelta+ lymphocytes maintain the integrity of intestinal epithelial tight junctions in response to infection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):818–829. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komori HK, Meehan TF, Havran WL. Epithelial and mucosal gammadelta T cells. Curr.Opin.Immunol. 2006;18(5):534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178(7):4466–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(1):25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girardi M, Lewis J, Glusac E, Filler RB, Geng L, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Resident skin-specific gammadelta T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp.Med. 2002;195(7):855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(1):73–79. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Sharp LL, Witherden DA, Havran WL. Gammadelta T cell-induced hyaluronan production by epithelial cells regulates inflammation. J Exp.Med. 2005;201(8):1269–1279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameson J, Havran WL. Skin gammadelta T-cell functions in homeostasis and wound healing. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalton JE, Cruickshank SM, Egan CE, Mears R, Newton DJ, Andrew EM, Lawrence B, Howell G, Else KJ, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Smith JE, White SJ, Carding SR. Intraepithelial gammadelta+ lymphocytes maintain the integrity of intestinal epithelial tight junctions in response to infection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):818–829. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kress E, Hedges JF, Jutila MA. Distinct gene expression in human Vdelta1 and Vdelta2 gammadelta T cells following non-TCR agonist stimulation. Mol.Immunol. 2006;43(12):2002–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedges JF, Cockrell D, Jackiw L, Meissner N, Jutila MA. Differential mRNA expression in circulating gammadelta T lymphocyte subsets defines unique tissue-specific functions. J Leukoc.Biol. 2003;73(2):306–314. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jutila MA, Holderness J, Graff JC, Hedges JF. Antigen-independent priming: a transitional response of bovine gammadelta T-cells to infection. Anim Health Res.Rev. 2008;9(1):47–57. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jutila MA, Holderness J, Graff JC, Hedges JF. Antigen-independent priming: a transitional response of bovine gammadelta T-cells to infection. Anim Health Res.Rev. 2008;9(1):47–57. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holderness J, Jackiw L, Kimmel E, Kerns H, Radke M, Hedges JF, Petrie C, McCurley P, Glee PM, Palecanda A, Jutila MA. Select plant tannins induce IL-2Ralpha upregulation and augment cell division in gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2007 Nov 15;179(10):6468–6478. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoll AH, Javaux EJ, Hewitt D, Cohen P. Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans. Philos.Trans.R.Soc.Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):1023–1038. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patthy L. Modular assembly of genes and the evolution of new functions. Genetica. 2003;118(2–3):217–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore D, Meskauskas A. A comprehensive comparative analysis of the occurrence of developmental sequences in fungal, plant and animal genomes. Mycol.Res. 2006;110(Pt 3):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogozin IB, Sverdlov AV, Babenko VN, Koonin EV. Analysis of evolution of exon-intron structure of eukaryotic genes. Brief.Bioinform. 2005;6(2):118–134. doi: 10.1093/bib/6.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lietava J. Medicinal plants in a Middle Paleolithic grave Shanidar IV. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;35(3):263–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90023-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capasso L. 5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics. Lancet. 1998;352(9143):1864. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79939-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nickel JC. Management of urinary tract infections: historical perspective and current strategies: Part 1--Before antibiotics. J Urol. 2005;173(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141496.59533.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frey EF. The earliest medical texts. Clio Med. 1985;20(1–4):79–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Wang MW. Botanical drugs: challenges and opportunities: contribution to Linnaeus Memorial Symposium 2007. Life Sci. 2008;82(9–10):445–449. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farnsworth NR, Akerele O, Bingel AS, Soejarto DD, Guo Z. Medicinal plants in therapy. Bull.World Health Organ. 1985;63(6):965–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eigsti OJ, Dustin P, Jr, Gay-Winn N. On the discovery of the action of colchicine on mitosis in 1889. Science. 1949;110(2869):692. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2869.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohamed Muhsin, Marcus Hoyle, Marguerite Dresser. Taxanes. Pharmacor. 2007 Apr 1;:1–143. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutcher JP, Novik Y, O'Boyle K, Marcoullis G, Secco C, Wiernik PH. 20th-century advances in drug therapy in oncology--Part. II. J Clin.Pharmacol. 2000;40(10):1079–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann CC, Plummer ML. The aspirin wars: money, medicine, and 100 years of rampant competition. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1991. pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito H, Kranz DM, Takagaki Y, Hayday AC, Eisen HN, Tonegawa S. A third rearranged and expressed gene in a clone of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1984;312(5989):36–40. doi: 10.1038/312036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimura H, Nitahara A, Ito A, Tomiyama K, Ito M, Kawai K. Up-regulation of cell surface Toll-like receptor 4-MD2 expression on dendritic epidermal T cells after the emigration from epidermis during cutaneous inflammation. J Dermatol.Sci. 2005;37(2):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedges JF, Lubick KJ, Jutila MA. Gamma delta T cells respond directly to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J Immunol. 2005;174(10):6045–6053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deetz CO, Hebbeler AM, Propp NA, Cairo C, Tikhonov I, Pauza CD. Gamma interferon secretion by human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells after stimulation with antibody against the T-cell receptor plus the Toll-Like receptor 2 agonist Pam3Cys. Infect.Immun. 2006;74(8):4505–4511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00088-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lubick K, Jutila MA. LTA recognition by bovine gammadelta T cells involves CD36. J Leukoc.Biol. 2006;79(6):1268–1270. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russano AM, Bassotti G, Agea E, Bistoni O, Mazzocchi A, Morelli A, Porcelli SA, Spinozzi F. CD1-restricted recognition of exogenous and self-lipid antigens by duodenal gammadelta+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3620–3626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2002;99(22):14338–14343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212290499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(1):73–79. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rincon-Orozco B, Kunzmann V, Wrobel P, Kabelitz D, Steinle A, Herrmann T. Activation of V gamma 9V delta 2 T cells by NKG2D. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2144–2151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson E, Aydintug MK, Jutila MA. A circulating bovine gamma delta T cell subset, which is found in large numbers in the spleen, accumulates inefficiently in an artificial site of inflammation: correlation with lack of expression of E-selectin ligands and L-selectin. J Immunol. 1999;162(8):4914–4919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glatzel A, Wesch D, Schiemann F, Brandt E, Janssen O, Kabelitz D. Patterns of chemokine receptor expression on peripheral blood gamma delta T lymphocytes: strong expression of CCR5 is a selective feature of V delta 2/V gamma 9 gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(10):4920–4929. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebert LM, Meuter S, Moser B. Homing and function of human skin gammadelta T cells and NK cells: relevance for tumor surveillance. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4331–4336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu.Rev.Immunol. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178(7):4466–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inagaki-Ohara K, Chinen T, Matsuzaki G, Sasaki A, Sakamoto Y, Hiromatsu K, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Nawa Y, Yoshimura A. Mucosal T cells bearing TCRgammadelta play a protective role in intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2004;173(2):1390–1398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jameson J, Havran WL. Skin gammadelta T-cell functions in homeostasis and wound healing. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Komori HK, Meehan TF, Havran WL. Epithelial and mucosal gammadelta T cells. Curr.Opin.Immunol. 2006;18(5):534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung CS, Watkins L, Funches A, Lomas-Neira J, Cioffi WG, Ayala A. Deficiency of gammadelta T lymphocytes contributes to mortality and immunosuppression in sepsis. Am.J Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2006;291(5):R1338–R1343. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00283.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts SJ, Smith AL, West AB, Wen L, Findly RC, Owen MJ, Hayday AC. T-cell alpha beta + and gamma delta + deficient mice display abnormal but distinct phenotypes toward a natural, widespread infection of the intestinal epithelium. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1996;93(21):11774–11779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hedges JF, Lubick KJ, Jutila MA. Gamma delta T cells respond directly to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J Immunol. 2005;174(10):6045–6053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedges JF, Cockrell D, Jackiw L, Meissner N, Jutila MA. Differential mRNA expression in circulating gammadelta T lymphocyte subsets defines unique tissue-specific functions. J Leukoc.Biol. 2003;73(2):306–314. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dieli F, Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, Ivanyi J, Sireci G, Bonanno CT, Ferlazzo V, La Mendola C, Salerno A. Reciprocal stimulation of gammadelta T cells and dendritic cells during the anti-mycobacterial immune response. Eur.J Immunol. 2004;34(11):3227–3235. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kress E, Hedges JF, Jutila MA. Distinct gene expression in human Vdelta1 and Vdelta2 gammadelta T cells following non-TCR agonist stimulation. Mol.Immunol. 2006;43(12):2002–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roark CL, Simonian PL, Fontenot AP, Born WK, O'brien RL. gammadelta T cells: an important source of IL-17. Curr.Opin.Immunol. 2008;20(3):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]