Abstract

Etiological models of alcohol use that highlight the role of negative affect and depression have not been applied to research on the association of suicidality and alcohol use. We sought to rectify this oversight by examining whether a motivational model of alcohol use could be applied to understanding the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes in a sample of underage college drinkers who had a history of passive suicidal ideation (n = 91). In this cross-sectional study, regression analyses were conducted to examine whether drinking to cope with negative affect statistically mediated or was an intervening variable in the association between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes. The results revealed that drinking to cope was a significant intervening variable in the relationships between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol problems, even while controlling for depression. These results suggest that the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes may be due to individuals using alcohol to regulate or escape the distress associated with suicidal ideation. Consideration of alcohol-related models can improve the conceptualization of research on suicidality and alcohol use.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, depression, alcohol problems, binge drinking, drinking to cope

College students have high rates of suicidal ideation and behavior, as well as heavy alcohol use and high rates of alcohol problems (Knight et al., 2002; O’Malley & Johnson, 2002). Studies using multi-item measures of suicidality that tap both passive and active suicidal ideation and behavior have found that approximately 44% to 74% of college students report some level of suicidal ideation during the prior month or year (Bonner & Rich, 1988; Rudd, 1989; Schotte & Clum, 1982; Strang & Orlofsky, 1990). Younger students appear to be at particular risk of both suicidal ideation and alcohol misuse. The National College Health Risk Behavior Survey study found that freshman and sophomores had seriously considered suicide in the prior year at more than twice the rate of seniors (14%, 12%, and 6% respectively; Brener, Hassan, & Barrios, 1999). Findings from the national Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol study revealed that underage (18- to 20-year-old) students appear to be somewhat less likely to drink than students between the ages of 21 and 23 (e.g., 77.4% underage and 85.8% legal age students drank in the past year); however, underage students who drank in the past year were more likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking, to drink with a goal of becoming drunk, and to experience greater alcohol problems (Wechsler, Lee, Nelson, & Kuo, 2002).

Alcohol use disorders and acute episodes of alcohol consumption are associated with both completed suicide and nonfatal suicide attempts (Borges, Walters, & Kessler, 2000; Cherpitel, Borges, & Wilcox, 2004; Hufford, 2001; Powell et al. 2001; Wilcox, Conner, & Caine, 2004). The link between alcohol and suicidal behavior appears to be stronger among younger age groups than among older age groups (Brady, 2006). Among college students, individuals with suicidal ideation and attempts are more likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking, use alcohol more frequently, and have greater alcohol problems (Brener et al., 1999; Levy, & Deykin, 1989; Stephenson, Pena-Shaff, & Quirk, 2006).

A criticism of suicidality research is that while many studies have identified “risk factors“ (i.e., correlates) for suicide, little of this research has been guided by theory (Galaif, Sussman, Newcomb, & Locke, 2007; Rogers, 2003). This has limited the development of causal models, which are critical for developing effective prevention efforts for suicidal behavior. This same criticism holds true in the study of alcohol and suicide. To date, the majority of research focusing on the relationship between suicidal behavior and alcohol use has consisted of descriptive or epidemiological studies that link completed suicides with alcohol dependence (Hufford, 2001); relatively little research exists exploring the causal mechanisms influencing this relationship. Most authors that have discussed the link between these phenomena have focused on explanations that involve alcohol increasing the likelihood of suicidal behavior, due to the social problems caused by alcohol abuse or the acute pharmacological effects of alcohol intoxication on cognition and affect (Cherpitel et al., 2004; Hufford, 2001; Kresnow et al., 2001).

What has been notably lacking is the application of other relevant research knowledge and theory regarding alcohol and suicidal behavior to understand what functional relationship may exist between these phenomena. Apparently overlooked have been etiological theories of alcohol use and problems that relate to negative affect and depression, and the clear applications that this research can have in our understanding of suicidal behavior and alcohol.

A model that emphasizes the role of negative affect in alcohol use is Cooper and colleagues’ motivational model of alcohol use (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Two affect regulation motives for drinking are proposed in this model; one in which alcohol use is motivated by an attempt to increase positive emotions (i.e., enhancement motives) and another in which alcohol use is motivated by attempts to escape or regulate negative affect (i.e., drinking to cope). Drinking to cope with negative affect is thought to be a learned behavior by individuals who lack more adaptive means of coping with negative affective states, including depression. The use of alcohol to regulate negative affect is presumed to lead to further deterioration of adaptive coping skills and to dependence on alcohol (Cooper et al., 1995), making individuals who experience greater negative affect at particular risk for developing alcohol problems (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000).

Empirical support for the negative affect regulation aspect of Cooper and colleagues’ motivational model of alcohol use is provided by studies of college student drinking. In college students, drinking to cope is more likely to be associated with alcohol-related problems than are other, perhaps more normative, drinking motives such as enhancement or social motives (Carey & Correia, 1997; Kassel, Jackson, Shannon, & Unrod, 2000). Further evidence is provided by general population and college student studies in which depression is associated with drinking to cope (Park & Levenson, 2002; Peirce, Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1994; Stewart & Devine, 2000) which, in turn, is associated with alcohol problems (Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995; Hutchinson, Patock, Cheong, & Nagoshi, 1998; Kassel et al., 2000).

Current evidence suggests that the relationship between depression and alcohol is due to the mediational role of drinking that is motivated by attempts to cope with negative affect (Cooper et al., 2000; Gaher, Simons, Jacobs, Meyer, & Johnson-Jimenez, 2006). A prospective study found that among individuals with major depressive disorder, a positive relationship between depression and alcohol use was only present among those who drank to cope with negative affect (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003). Schuckit, Smith, and Chacko (2006) found evidence in a longitudinal study that independent depressive episodes (i.e., not substance-induced) significantly contributed to the development of alcohol problems, with drinking to cope partially mediating this relationship. Pierce et al. (1994) also found drinking to cope partially mediated the relationship between depression and alcohol problems, and that it completely mediated the relationship between depression and alcohol use. These authors also found that the association between depression and drinking to cope was stronger among younger participants. Mohr et al. (2005), using a daily process methodology, found that college students endorsing higher levels of drinking to cope based their daily drinking on negative moods, while those with lower levels of drinking to cope motives did not.

The findings of a recent study suggest that suicidal ideation may show the same pattern of relationships to drinking to cope as depression. Among homeless adolescents and emerging adults, drinking or using substances to cope was positively associated with suicidal ideation and with a history of attempted suicide (Kidd & Carroll, 2007). However, this study did not explore the unique relationship of suicidal ideation to drinking to cope while controlling for depression. It may be that the relationship between drinking to cope and suicidal ideation can be attributed to suicidal ideation’s relationship with depression.

In the present study we sought to apply Cooper and colleagues’ motivational model of alcohol use to understanding the association between suicidal ideation and alcohol use and problems in underage college drinkers. Given that drinking to cope has been found to mediate the relationship between depression and alcohol use/abuse (e.g., Peirce et al., 1994), we hypothesized that drinking to cope would statistically mediate the relationships of suicidal ideation to alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol problems. Previous studies in college students and in drug users have found that suicidal ideation is associated with alcohol problems even after controlling for depression (Cottler, Campbell, Krishna, Cunningham-Williams, & Abdallah, 2005; Stephenson et al., 2006), suggesting that an underlying association with depression does not account for their relationship. Therefore, we hypothesized that drinking to cope would statistically mediate the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol use and problems, even after we controlled for level of depression. We also examined the role of depression and suicidal ideation relative to one another in their effect on drinking to cope and alcohol outcomes in order to elucidate how they each relate to alcohol outcomes, both separately and relative to one another.

Method

Participants

Participants were 91 underage (between 18 and 20 years old) female (52.7%, n = 48) and male (47.3% n = 43) drinkers attending a large public university in New York State. All participants had a history of, at a minimum, passive suicidal ideation.

The average age of the study sample was 19.0 (SD =.74) and 100% were single (never married). The sample was 75.8% White/European American, 12.6% Asian American, 4.2% Black/African American, 4.2% Latino, and 3.2% multiethnic. With regards to class standing, the sample was 23.2% freshman, 55.8% sophomore, 20.0% junior, and 1.0% senior. The majority of participants (94.7%) did not live with their parents, with a large proportion of the sample living on-campus (74.7%).

Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university. Participants were recruited via advertising in the university school newspapers and flyers posted on campus. Advertisements directed potential participants to a webpage that described the study and included questions that assessed study eligibility embedded among distracter questions inquiring about health and mood-related behaviors. Eligibility criteria included: (1) having consumed at least four standard alcoholic drinks in the past month, (2), being a full- or part-time student of the university, (3) being between the ages of 18 and 20 years old, and (4) reporting a history of passive suicidal ideation (endorsement of a single item, “In the past, have you thought it would be better if you were not alive?”). The relatively low level of alcohol consumption in the past month (at least 4 drinks) was chosen as an eligibility criterion in order to include students who demonstrate a wide range of drinking behavior and problems. We chose to use as one of the selection criteria a history of passive suicidal ideation, this was done in order to include a significant number of individuals with recent suicidal ideation and a wide range of suicidal intensity and severity. In addition, the selected screening item represents a mild and passive form of suicidal ideation, and therefore it was expected to be minimally distressing to individuals being screened via the World Wide Web.

Eligible individuals were directed to a webpage informing them of their eligibility, what was required of them to participate, and the compensation they would receive for participation in the study. Eligible individuals provided contact information and were then contacted via e-mail and scheduled for a data collection session held on campus. A total of 100 individuals were screened as eligible and completed the protocol described below. However, nine of these individuals did not meet the eligibility criteria based on an examination of their responses to the study questionnaires and therefore were not included in this study.

Study materials consisted of a packet of self-report questionnaires, administered in a single session. These measures were administered in a counterbalanced fashion to control for possible ordering or fatigue effects. Data collection sessions consisted of administration of the study materials to groups of between 2 and 12 participants. Participants were compensated $20 for their time.

All participants were individually debriefed by the first author at the conclusion of the study session and provided referral information for counseling, suicide hotline telephone numbers, and were offered immediate facilitation in seeking counseling services. None of the participants reported an interest in being facilitated with obtaining counseling services and no adverse events (e.g., participant distress or verbal reports of suicidal ideation or intent) were noted.

Measures

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption in the past month was measured using items modified from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA) Alcohol Consumption Question Set (NIAAA, 2003). Participants reported the number of days on which they drank in the past month and the typical number of drinks consumed per drinking day in the past month. Responses to these items were used to calculate a quantity-frequency index of drinks per week consumed in the past month. Participants were asked on how many days during a typical month in the past year they drank 4 or more (females) or 5 or more (males) drinks on one occasion or sitting. Reponses to this item were used to quantify typical frequency of heavy episodic drinking per month.

Drinking to cope

The Drinking Context Scale (DCS; O’Hare, 2001) is a 9-item self-report inventory of three drinking contexts: convivial drinking, personal-intimate drinking, and negative coping. Respondents rate each item based on the chances they would find themselves drinking excessively from extremely high (5) to extremely low (1) in the presented context. This scale evidences concurrent validity, with scores being predictive of alcohol problems among college students (O’Hare, 2001). For this study, the Negative Coping subscale was used to quantify drinking excessively to cope with negative affect. Items from this subscale include likelihood of excessive drinking: after a fight with someone close, when feeling sad/depressed/discouraged, and when angry with oneself or someone else. This subscale demonstrated high internal consistency in our study sample (alpha coefficient =.91).

Alcohol Problems

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006) is a 48-item self-report inventory of problems associated with alcohol use among college students. The YAACQ items are rated dichotomously as present or absent in the past year. The YAACQ includes items from the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC; Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1993), the Young Adult Problem Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992), and includes items that cover the symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence as defined by the DSM-IV. Several items are specific to student-related alcohol problems, such as missing class, neglecting obligations at school, or having received a lower grade because of drinking. The YAACQ has demonstrated good convergent and concurrent validity (Read et al., 2006) and the total scale demonstrated high internal consistency in our study sample (alpha coefficient =.92).

Suicidal Ideation

The Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ; Reynolds, 1991b) is a 25-item self-report measure of suicidal thoughts and behavior experienced during the last month. Items are rated on a 7-point scale (0 = never had the thought, 6 = almost everyday). Items range from general wishes one were dead to thoughts of planning a suicide attempt. The ASIQ demonstrates high two-week test-retest reliability in college students, with a correlation of.86 between administrations (Reynolds, 1991b). The ASIQ evidences good convergent validity in college students via moderate correlations to other self-report measures of suicidality (Reynolds, 1991b; Gutierrez, Osman, Kopper, Barrios, & Bagge, 2000). The ASIQ has also evidenced predictive validity, with total score significantly predicting suicide attempts over a 3-month follow-up period among psychiatric inpatients that had previously attempted suicide (Osman et al., 1999). This scale demonstrated high internal consistency in our study sample (coefficient alpha =.96).

Additionally, items relating to past year suicidal ideation and attempts from the National College Health Risk Behavior Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1995) were included to allow comparisons of the results obtained in this study regarding rates of suicidality to those of a nationally representative study of college students.

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a widely used 21-item self-report scale that measures severity of depressive symptoms. Items are rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II evidences high test-retest reliability, criterion, and convergent validity among university students (Sprinkle et al., 2002). In our sample it demonstrated high internal consistency (coefficient alpha =.91). For the current study, the BDI-II total scores were calculated with the suicidal ideation item omitted in order to avoid a confound with our measurement of suicidal ideation.

Analyses

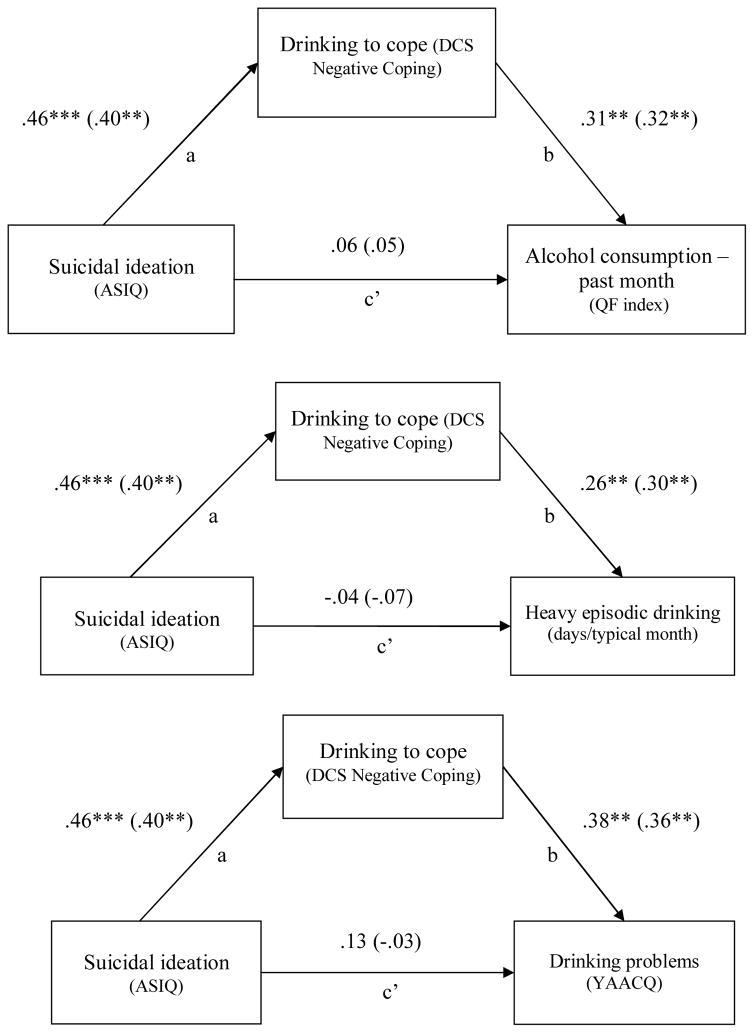

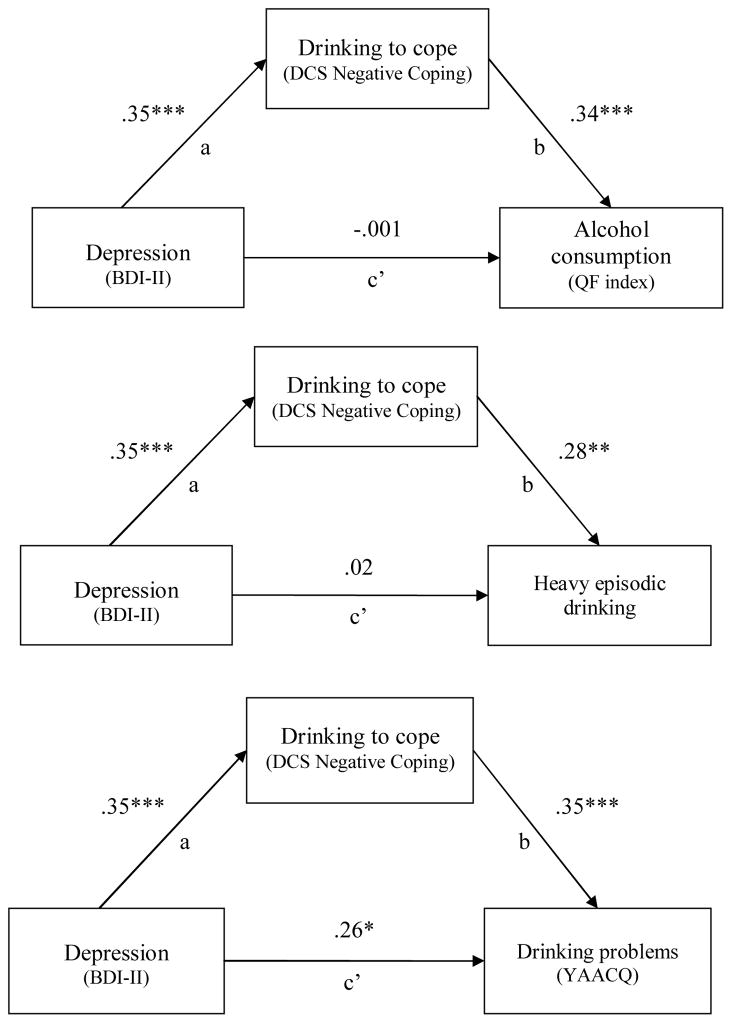

Drinking to cope was hypothesized to be an intervening or mediating variable in the associations between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol problems. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to estimate the associations between the variables for each path of our mediational models (see Figures 1 and 2). We examined the association of (1) suicidal ideation to alcohol use and/or problems (c paths); (2) suicidal ideation to drinking to cope (a path); (3) drinking to cope to alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and/or alcohol problems while controlling for suicidal ideation (b paths); and (4) the independent variable (i.e., suicidal ideation or depression) to the dependant variable in each model (e.g., alcohol problems) when drinking to cope was included in the model (c’ path).

Figure 1.

Mediating or intervening role of drinking to cope with negative affect in the relationships between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes among underage college drinkers with a history of at least passive suicidal ideation. Depicted above are the standardized regression coeffecients for each path of the mediation models. In parentheses are the standardized regression coefficients in identical analyses which controlled for depression. ** p <.001. *** p <.001.

Figure 2.

Mediating or intervening role of drinking to cope with negative affect in the relationships between depression and alcohol outcomes. Depicted above are the standard regression coefficients for each model path. * p <.05. ** p <.001. *** p <.001.

The causal steps approach, such as that of Barron and Kenny (1986), is the most commonly used approach for examining statistical mediation (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheet, 2002). However, causal steps methods have been shown to result in markedly low power and to be likely to miss real effects, particularly when there is complete mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2002; MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). Therefore, following the suggestion of MacKinnon et al. (2002), we examined the significance of our mediational models by testing the joint significance of the independent variable to mediator (path a) and mediator to dependant variable (path b). The Sobel test, which yields a z value, was used to test the significance of the joint effect of the a and b paths in each mediation analysis conducted. The mediational relationship of drinking to cope in the relationship of suicidal ideation to alcohol outcomes was examined first. This was followed by an examination of the mediational relationship of drinking to cope in the relationship of depression to alcohol outcomes. Finally, we examined the relationship of suicidal ideation to drinking to cope and the alcohol outcome variables while controlling for depression, and the relationship of depression to these variables while controlling for suicidal ideation. As previously noted, depression was measured by the BDI-II with the suicidal ideation item omitted from scoring to avoid a potential confound with suicidal ideation. Gender was entered into all analyses to control for its effects on drinking variables (e.g., Harrell, & Karim, 2008).

Prior to these analyses, data were screened for missing data, univariate and multivariate outliers, and non-normal response distributions following the procedures outlined in Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Linear interpolation in SPSS version 14.0 was used to estimate participants’ responses to missing items on the ASIQ (.4% items missing) and the YAACQ (.6% items missing) based on the data provided for the completed items on the questionnaire. One variable was markedly positively skewed (alcohol consumption) and as a result was square-root transformed. One case was found to be a multivariate outlier (Mahalanobis distance at p <.001) and was dropped from further analyses.

Results

Descriptive Information and Intercorrelations

The inclusion criterion of a history of at least passive suicidal ideation was effective in recruiting significant numbers of individuals with a wide range of suicidal ideation and behavior. In our study, 3.3% (n = 3) of the sample reported a suicide attempt in the past year, 13.3% (n = 12) made a plan for suicide, and 15.6% (n = 14) seriously considered suicide in the past year compared to 1.7%, 7.9%, and 11.4% respectively in the National College Health Risk Behavior Survey of 18-to 24-year-old college students (Barrios, Everett, Simon, & Brener, 2000). Nine individuals (9.9%) reported having ever made a suicide attempt. In our study a large proportion of participants also reported having recently experienced suicidal ideation, with 61% (n = 58) reporting suicidal ideation in the past month based on ASIQ responses. Additionally, 22% (n = 20) were above the clinical cutoff (at or above 31) on the ASIQ, which identifies individuals who are actively thinking about suicide (Reynolds, 1991a).

With respect to level of depression in the study sample, as measured by the BDI-II total scale score (including the suicidal ideation item), 41.1% had minimal depression (scores ≤ 13), 17.8% had mild depression (scores between 14 and 19), 25.6% had moderate depression (scores between 20 and 28), and 15.6% had severe depression (scores ≥ 29; Beck et al., 1996). On average, participants drank 9.38 days (SD = 6.18) in the past month and consumed an average of 6.36 standard drinks (SD = 3.24) on a typical drinking day in the past month. On average, participants reported approximately 7 heavy drinking days on a typical month in the past year, with only 2.2% (n = 2) reporting not having any heavy drinking days on a typical month.

Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of suicidal ideation, depression, alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, drinking problems, drinking to cope, and gender. Greater suicidal ideation was strongly associated with greater depression and drinking to cope, and was moderately associated with greater alcohol consumption over the past month and drinking problems over the past year. Suicidal ideation showed a small, non-significant association with heavy episodic drinking. Depression showed small, non-significant associations with alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking, but showed significant moderate associations with alcohol problems and drinking to cope. Men reported significantly greater suicidal ideation, alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and drinking to cope than women. Men and women did not differ significantly on level of depression or number of alcohol problems experienced in the past year.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of study variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Suicidal ideation (ASIQ) | -- | 22.84 | 20.08 | |||||

| 2. Depression (BDI-II)1 | .63*** | -- | 17.68 | 10.14 | ||||

| 3. Alcohol consumption (drinks per week-past month)2 | .26* | .15 | -- | 16.01 | 13.56 | |||

| 4. Heavy episodic drinking (days per month/past year) | .17 | .15 | .73*** | -- | 6.77 | 4.91 | ||

| 5. Drinking problems (YAACQ) | .33*** | .39*** | .46*** | .58*** | -- | 19.94 | 9.71 | |

| 6. Drinking to cope (DCS-Negative coping) | .49*** | .36*** | .39*** | .35*** | .46*** | -- | 7.62 | 3.23 |

| 7. Gender3 | −.19* | −.15 | −.33*** | −.38*** | −.16 | −.20* | -- | -- |

Suicidal ideation item omitted from BDI-II scoring to avoid a confound with suicidal ideation (ASIQ); mean score for total the scale was 18.08 (SD = 10.43).

Correlations were calculated using the square-root transformed variable, while the mean and standard deviation shown represent the untransformed variable.

Gender was dummy coded such that men = 0 and women = 1.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Tests of statistical mediation

Suicidal ideation to alcohol outcomes

In separate regression analyses, we examined the direct associations between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption (R2 =.15, p ≤.001), heavy episodic drinking (R2 =.15, p ≤.001), and alcohol problems (R2 =.12, p <.01). Greater suicidal ideation was significantly associated with greater alcohol consumption in the past month (B =.02 [.01], β =.20, p <.05) and with greater alcohol problems (B =.15 [.05], β =.31, p <.01). Suicidal ideation was not directly associated with heavy episodic drinking (B =.03 [.02], β =.10).

The a path of the models (see Figures 1 and 2) was examined via a regression analysis of the association between suicidal ideation and drinking to cope (R2 =.25, p ≤.001). This analysis revealed that greater suicidal ideation was significantly associated with greater drinking to cope (B =.07 [.02], β =.46; see Figure 1). Separate regression analyses controlling for suicidal ideation were then used to examine the relationships of drinking to cope with alcohol consumption (R2 =.22, p ≤.001), heavy episodic drinking (R2 =.22, p ≤.001), and alcohol problems (R2 =.23, p ≤.001). These analyses revealed that the b paths of the models were all significant, with drinking to cope positively associated with alcohol consumption (B =.15 [.05], β =.31), heavy episodic drinking (B =.45 [.17], β =.26), and alcohol problems (B = 1.15 [.33], β =.38). These analyses also suggested complete statistical mediation for the alcohol consumption and problems models (see c’ paths in Figure 1), as the direct relationships of suicidal ideation to these variables were no longer significant when controlling for drinking to cope. Tests of the indirect or joint effect of the a and b paths revealed that drinking to cope was a significant intervening variable between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption (Sobel test, z = 2.47, p <.05), heavy episodic drinking (z = 2.38, p <.05), and alcohol problems (z = 2.89, p <.01).

In summary, these analyses suggest that the direct relationship of suicidal ideation to alcohol consumption and problems is owing to suicidal ideation’s effect on drinking to cope, which in turn, was associated with increased alcohol use and problems. While greater suicidal ideation was not significantly directly associated with frequency of heavy episodic drinking in a typical month in the past year, the test of the b path revealed that greater drinking to cope was significantly associated with more frequent heavy episodic drinking. The test of indirect effect revealed that greater suicidal ideation was associated with heavy episodic drinking indirectly through its effect on drinking to cope.

Depression to alcohol outcomes

In separate regression analyses, we examined the direct associations between depression and alcohol consumption (R2 =.12, p <.01), heavy episodic drinking (R2 =.15, p ≤.001), and alcohol problems (R2 =.17, p ≤.001). These analyses revealed that depression was not significantly (p >.05) directly related to alcohol consumption (B [SE] =.02 [.02], β =.12) or to heavy episodic drinking (B =.05 [.05], β =.08), while depression was significantly associated with drinking problems (B =.36 [.09], β =.38, p ≤.001).

Next, a regression analysis was used to examine the relationship of depression to drinking to cope (R2 =.16, p ≤.001). This analysis revealed that greater depression was significantly associated with greater drinking to cope (B =.11 [.03], β =.35, see Figure 2). Separate regression analyses controlling for depression were then used to examine the relationships of drinking to cope with alcohol consumption (R2 =.22, p <.01), heavy episodic drinking (R2 =.22, p ≤.001), and alcohol problems (R2 =.27, p <.01). Drinking to cope was significantly associated with greater alcohol consumption (B =.17 [.05], β =.34), more frequent heavy episodic drinking (B =.42 [.16], β =.28), and greater alcohol problems (B = 1.06 [.30], β =.35).

The tests of the indirect effect revealed that drinking to cope was a significant intervening variable between depression and alcohol consumption (Sobel test, z = 2.49, p <.05), heavy episodic drinking (z = 2.54, p <.05), and alcohol problems (z = 2.13, p <.05). Depression remained significantly associated with alcohol problems (B =.25 [.09], β =.26, p <.05) while controlling for drinking to cope, thus drinking to cope only partially mediated the relationship of depression and alcohol problems.

Relationships when controlling for depression or suicidal ideation

In separate regression analyses controlling for depression, we examined the direct relationship of suicidal ideation to alcohol consumption (R2 =.15, p <.01), heavy episodic drinking (R2 =.16, p <.01), and alcohol problems (R2 =.18, p ≤.001). Given that both suicidal ideation and depression were entered simultaneously into the regression models, these analyses may alternatively be viewed as examinations of the relationship of depression to alcohol outcomes while controlling for suicidal ideation. Controlling for depression in these analyses resulted in an attenuation of the relationships found between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption (B =.02 [.01], β =.21), heavy episodic alcohol consumption (B =.01 [.03], β =.05), and alcohol problems (B =.06 [.06], β =.11), such that none remained statistically significant. It should be noted that while an examination of the standardized betas in the analyses of alcohol consumption before (β =.20) and after controlling (β =.21) for depression suggested that the relationship was actually slightly strengthened when controlling for depression, an examination of the semipartial correlations revealed a reduction when depression was included in the model such that the semipartial correlation between these variables was reduced from.20 to.16. This indicates that the relationship of suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption was attenuated when controlling for depression.

Examining the relationship of depression to the alcohol use outcomes in these analyses revealed that as in the analyses that did not include (i.e., control for) suicidal ideation in the models, there were no significant direct relationships between depression and alcohol consumption or heavy episodic drinking. However, depression remained significantly directly associated with alcohol problems when suicidal ideation was included in the model (B =.30 [.12], β =.31, p <.05).

A regression analysis examining the indirect effects of suicidal ideation on drinking to cope while controlling for depression (R2 =.25, p ≤.001) revealed that greater suicidal ideation remained significantly associated with greater drinking to cope (B =.06 [.02], β =.40), but this relationship was attenuated when depression was controlled for (see Figure 1). In contrast, depression was no longer significantly associated with drinking to cope when suicidal ideation was included in the model (B =.03[.04], β =.10). Suicidal ideation and depression together accounted for 21% of the variance in drinking to cope, with suicidal ideation uniquely explaining 9% of the variance and depression uniquely explaining less than 1% of the variance. The test of the b paths revealed that drinking to cope remained positively associated with alcohol consumption (B =.16 [.05], β =.32), with no attenuation in the relationship associated with controlling for depression. The associations between drinking to cope and heavy episodic drinking (B =.45 [.17], β =.30) and alcohol problems (B = 1.08 [.32], β =.36) were also essentially unchanged by including depression in the models.

The tests of the indirect effects revealed that drinking to cope remained a significant intervening variable between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption (Sobel test, z = 2.17, p <.05), heavy episodic drinking (z = 2.17, p <.05), and alcohol problems (z = 2.36, p <.05) even after controlling for depression. However, Sobel tests revealed that depression was not indirectly related to alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, or alcohol problems when suicidal ideation was included in the model as a control variable.

In summary, while suicidal ideation was no longer directly associated with alcohol outcomes when controlling for depression, suicidal ideation remained significantly indirectly related to alcohol outcomes through drinking to cope. This suggests that the indirect relationships found between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes were not attributable to third variable relationships with depression. In contrast, the indirect relationships of depression with alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol problems were no longer significant when suicidal ideation was entered as a control variable. However, depression remained directly related to alcohol problems even when suicidal ideation was included in the model.

Discussion

The findings of the current study lend support to the applicability of a motivational model of alcohol use in understanding the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol use and problems among underage college drinkers. As we hypothesized, greater suicidal ideation was associated with greater alcohol consumption and problems, with drinking to cope completely statistically mediating these relationships. While suicidal ideation failed to show a significant direct relationship with heavy episodic drinking, it was indirectly associated with frequency of heavy episodic drinking through its effect on drinking to cope. Although suicidal ideation and depression were highly associated, even after controlling for depression, drinking to cope remained a significant intervening variable in the relationships between suicidal ideation and alcohol consumption, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol problems. These results indicate that the associations found between suicidal ideation, drinking to cope, and alcohol outcomes are not solely attributable to the already established relationship of depression to these variables.

Consistent with previous research, drinking to cope was an intervening or mediating variable linking depression with alcohol use and problems. Also consistent with previous research (e.g., Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995; Schuckit et al., 2006), depression was not significantly directly related to alcohol consumption or heavy episodic drinking, but it was directly associated with alcohol problems, with drinking to cope only partially mediating this relationship. These findings suggest that the association between depression and alcohol problems is an indirect one in which greater depression results in greater drinking to cope, which results in greater alcohol use and, hence, greater alcohol problems. Another causal link between depression and alcohol problems might be that individuals suffering from depression have a higher likelihood of incurring negative drinking outcomes owing to their depression, despite consuming similar amounts of alcohol as compared with non-depressed individuals. For example, students with greater symptoms of depression may be more likely to have interpersonal problems as a result of drinking, or to miss class after a night of drinking, compared with peers who drank similar amounts but were not experiencing the same level of depression.

In this study, suicidal ideation showed a stronger relationship with drinking to cope than did depression. While the current study cannot explain this result, one possibility is that suicidal ideation is associated with greater coping skills deficits than depression. As reviewed earlier, Cooper and colleague’s motivational model of alcohol use suggests that coping skills deficits are an important factor in the motivation to use alcohol to cope and to the development of alcohol problems (Cooper et al., 1995). Similarly, theories of suicidal ideation also note the important role of coping skills deficits as possible cause or effect in suicidal ideation (e.g., Reinecke, 2006). Although not explored in the current study, it may be that the degree of suicidal ideation affects problem solving abilities and/or reliance on avoidant coping strategies, thereby making drinking to cope more likely to occur. Previous research has shown that suicidal ideation is associated with reduced problem solving abilities and with greater use of avoidant coping strategies, similar to findings linking coping skills deficits with drinking to cope (e.g., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, O’Brien, Kliber, Arata, & Bowers, 2006; Schotte & Clum, 1982). Future studies are needed to explore the possible underlying mechanism in the association between suicidal ideation and drinking to cope.

In addition, it may be that the drinking motivated by suicidal ideation provides greater reward incentive, relative to drinking motivated by other depressive symptoms. As suggested by motivational and other social learning theory-based models of alcohol use, individuals who drink in response to negative affect may find alcohol use rewarding in that it provides temporary relief from distressing negative affective states (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Cooper et al., 2000). Following repeated pairings of negative affect and alcohol use, negative affective states may become an introceptive cue for alcohol consumption among these individuals (Wiers et al., 2002). As a result, alcohol consumption may become an effective coping strategy for relieving painful negative affective states, in particular, those involving suicidal cognition and affect. It may be that the cognitive aspects of suicidal ideation are more responsive to the effects of alcohol intoxication than are other depressive symptoms, such as depressed mood or loss of pleasure. Further study is needed to examine whether specific symptoms of depression are more likely to elicit drinking to cope.

Based on the findings of this study, severity of suicidal ideation appears to increase the use of alcohol in an apparent attempt to regulate or escape negative affect. However, this study used a cross-sectional design and therefore conclusions regarding directionality of the effects are not possible. Prospective studies are needed to begin to establish a causal, directional association between suicidal ideation and drinking to cope. One issue that should be noted for future studies involves the timing of the measurement of suicidal ideation and the onset of drinking to cope, as drinking to cope likely occurs very quickly (e.g., within hours) in response to suicidal ideation. We expect that a methodology such a daily process approach or ecological momentary assessment would be best suited to studying this relationship prospectively (Collins & Muraven, 2007). Another consideration when interpreting the results of this study is that, although not explored in our study, there is likely a reciprocal relationship between suicidality and alcohol use. This may include a heightened risk of suicide or a suicide attempt among individuals who use alcohol to cope with suicidal ideation, given that alcohol may impair judgment, increase impulsivity, and possibly worsen mood (Cherpitel et al., 2004).

Another limitation of the current study is the relatively small sample size for detecting less robust relationships among the variables. When comparing our study results with those involving much larger sample sizes, the issue of effect size or the magnitude of the relationships should be kept in mind. For example, the statistical significance of the results of our study suggests a lack of a direct relationship between depression and heavy episodic alcohol use. In contrast, Cooper et al. (2000) in a study of young adults utilizing a large sample (n = 1,666) reported a significant but smaller zero-order correlation (r =.07, p <.01) between heavy alcohol use and a similar construct (neuroticism) than was found in our study between depression and heavy episodic drinking (r =.15, p >.05).

The college years, because they occur (for the traditional student) at a time of transition from adolescence to early adulthood, is viewed as a critical developmental time period. If an individual does not develop more adaptive coping skills, problematic behaviors that are established during this important period may become habitual and have deep and lasting consequences. The findings of this study suggest that the association between suicidal ideation and alcohol problems may be due to individuals using alcohol to cope with the negative affect and distress that accompanies suicidal ideation. In college students, drinking to cope with negative affect has been implicated in problematic drinking and in failing to mature out of problematic drinking patterns (Park & Levenson, 2002). The strong association found in this study between suicidal ideation and drinking to cope suggests that students with suicidal ideation are vulnerable to developing enduring alcohol problems. If not addressed, using alcohol to cope with negative affect may also leave these individuals vulnerable to enduring problems with affect regulation, and continued and recurrent problems with suicidal ideation and attempts. Further research is needed to examine the possible causal associations between suicidal ideation and alcohol problems and the long term consequences of experiencing these difficulties in early adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds provided through the University at Buffalo Research Institute on Addictions Research Development Program and a National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant (T32-AA007583).

Footnotes

Portions of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Chicago, Illinois, July 2007.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb.

References

- Abrams DB, Niaura RS. Social learning theory. In: Blane HT, Leonard KE, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1987. pp. 131–172. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios LC, Everett SA, Simon TR, Brener ND. Suicide ideation among US college students: Associations with other injury risk behaviors. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:229–233. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner RL, Rich AR. A prospective investigation of suicidal ideation in college students: A test of a model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1988;18:245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1988.tb00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Associations of substance use, abuse and dependence with subsequent suicidal behavior. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:781–789. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. The association between alcohol misuse and suicidal behaviour. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41:473–478. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Hassan SS, Barrios LC. Suicidal ideation among college students in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:1004–1008. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camatta CD, Nagoshi CT. Stress, depression, irrational beliefs, and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: National College Health Risk Behavior Survey. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease and Health Promotion; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpital CJ, Borges GLG, Wilcox HC. Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(Suppl 1):18S–28S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000127411.61634.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Muraven M. Ecological momentary assessment of alcohol consumption. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self reports in health research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Agocha V, Sheldon M. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Campbell W, Krishna VAS, Cunningham-Williams RM, Abdallah AB. Predictors of high rates of suicidal ideation among drug users. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:431–437. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000168245.56563.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaher R, Simons J, Jacobs G, Meyer D, Johnson-Jimenez E. Coping motives and trait negative affect: Testing mediation and moderation models of alcohol problems among American Red Cross disaster workers who responded to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1319–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaif E, Sussman S, Newcomb M, Locke T. Suicidality, depression, and alcohol use among adolescents: A review of empirical findings. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2007;19:27–35. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Bagge CL. Suicide risk assessment in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell Z, Karim N. Is gender relevant only for problem alcohol behaviors? An examination of correlates of alcohol use among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR. Alcohol and suicidal behavior. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson GT, Patock PJA, Cheong J, Nagoshi CT. Irrational beliefs and behavioral misregulation in the role of alcohol abuse among college students. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 1998;16:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Shannon I, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:332–357. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S, Carroll M. Coping and suicidality among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Meichun K, et al. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresnow M, Ikeda RM, Mercy JA, Powell KE, Potter LB, Simon TR, et al. An unmatched case-control study of nearly lethal suicide attempts in Houston, Texas: Research methods and measurements. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;32(Suppl 1):7–20. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.7.24210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, O’Brien N, Klibert J, Arata C, Bowers D. Gender specific associations among suicide proneness and coping strategies in college men and women. In: Landow MV, editor. College students: Mental health and coping strategies. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science; 2006. pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Levy JC, Deykin EY. Suicidality, depression, and substance abuse in adolescence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146:1462–1467. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.11.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, 4, (NIH Publication No. 95–3911) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, et al. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Task Force on Recommended Questions of the National Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Recommended Sets of Alcohol Consumption Questions. 2003 October 15–16; Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/ResearchResources/TaskForce.htm.

- O’Hare T. The Drinking Context Scale: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley HW, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 2002;14:23–29. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Kopper BA, Linehan MM, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Bagge CL. Validation of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire and the Reasons for Living Inventory in an adult psychiatric inpatient sample. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems, and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Relationship of financial strain and psychosocial resources to alcohol use and abuse: The mediating role of negative affect and drinking motives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;35:291–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Kresnow M, Mercy JA, Potter LB, Swann AC, Frankowski RF, et al. Alcohol consumption and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;32(Suppl 1):30–41. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.30.24208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke M. Problem solving: A conceptual approach to suicidality and psychotherapy. In: Ellis T, editor. Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Adult Suicide Ideation Questionnaire: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Psychometric characteristics of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in college students. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991b;56:289–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5602_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai AH, George CJ, Stack JA, Mann JJ, Reynolds CF. Hopelessness in suicide attempters after acute treatment of major depression in late life. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1687–1690. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JR. The anatomy of suicidology: A psychological science perspective on the status of suicide research. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:9–19. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.1.9.22783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD. The prevalence of suicidal ideation among college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1989;19:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1989.tb01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte DE, Clum GA. Suicide ideation in a college population: A test of a model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:690–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M, Smith T, Chacko Y. Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko SL, Atkinson G, Jones GL, Logan AR, et al. Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson Pena-Shaff, Quirk Predictors of college student suicidal ideation: gender differences. College Student Journal. 2006;40:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Devine H. Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality Individual Differences. 2000;29:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Strang SP, Orlofsky JL. Factors underlying suicidal ideation among college students: A test of Teicher and Jacobs’ model. Journal of Adolescence. 1990;13:39–52. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(90)90040-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Nelson T, Kuo M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:223–236. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers R, Stacy A, Ames S, Noll J, Sayette M, Zack M, et al. Implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(Suppl 1):S11–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]