Abstract

Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) has been available in some form for greater than three decades. Early management for airway obstruction during sleep relied on tracheotomy which although life saving was not well accepted by patients. In the early eighties two new forms of treatment for OSAS were developed. Surgically a technique described as a uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) was used to treat the retropalatal region for snoring and sleep apnea. Concurrently sleep medicine developed a nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device to manage nocturnal airway obstruction. Both of these measures were used to expand and stabilize the pharyngeal airway space during sleep. The goal for each technique was to limit or alleviate OSAS. Almost 30 yr later these two treatment modalities continue to be the mainstay of contemporary treatment. As expected, CPAP device technology improved over time along with durable goods. Surgery followed suit and additional techniques were developed to treat soft and bony structures of the entire upper airway (nose, palate and tongue base). This review will only focus on the contemporary surgical methods that have demonstrated relatively consistent positive clinical outcomes. Not all surgical and medical treatment modalities are successful or even partially successful for every patient. Advances in the treatment of OSAS are hindered by the fact that the primary etiology is still unknown. However, both medicine and surgery continue to improve diagnostic and treatment methods. Methods of diagnosis as well as treatment regimens should always include both medical and surgical collaborations so the health and quality of life of our patients can best be served.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, Airway reconstruction, Powell-Riley protocol, Contemporary surgery

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is seen in all age groups. The prevalence is greater in men (24%) than women (9%) (1). The most common complaints that bring patients to a physician are snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). The syndrome is associated with arousals and fragmented sleep due to an anatomic partial collapse or total obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. Generally, as severity increases over time in OSAS, so do the pathophysiologic derangements which cause morbidities and mortality including hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, stroke and sudden death. However, the behavioral derangements tend to show up far sooner than the pathophysiologic problems, as EDS creates severe decrements in quality of life. These findings substantiate the necessity for diagnosis and treatment of OSAS.

Besides weight reduction, surgical management was the first treatment modality available for OSAS. Some of the first subjects to undergo surgery for an anatomic narrowing or blockage of the upper airway during sleep were those afflicted with the Pickwickian syndrome (obesity-hypoventilation syndrome). Tracheotomy was the sole surgical procedure available during this period (2) and since it was life saving in these circumstances it was often used for patients with nocturnal upper airway obstruction. The tracheotomy was not well tolerated or accepted by most patients even as a method to improve the quality of life, or even to extend life itself. In the early 70's the term used to describe nocturnal airway obstruction was hypersomnia with periodic apnea (HPA), later revised to be called OSAS.

Over the years our knowledge of sleep disorders has evolved to such an extent that the field is now a recognized specialty in medicine and will be, in the future, a specialty in Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery as well as other interested surgical fields.

The coupling of medicine and surgery for the definitive management of OSAS results in optimal treatment. This combination provides the patient with options, as not all patients will accept one approach or the other as their initial treatment modality.

Over time both medicine and surgery have recognized that the obstructive process in sleep disorders breathing is predominately a diffuse upper airway problem. Hence, nocturnal narrowing or complete obstruction may be localized to one or two areas but there is usually diffuse involvement which encompasses the entire pharyngeal upper airway passages. The three major regions are the nasal cavity, retropalatal (RP) and retrolingual (RL) regions. Difficulty of treatment and rates of success become more problematic as the level of these three regions descends. This is due to the fact that tissue volume increases significantly from the nose to the base of tongue.

Conservative medical therapy is usually recommended first as it is non invasive. Medical sleep centers provide several treatment methods for OSAS such as sleep hygiene, weight loss, dental splints and continuous positive airway pressure devices (CPAP/BiPAP). There are also surgical procedures presently available to provide for a logical reconstruction of the upper airway. Contemporary surgical procedures offer reconstruction of the airway from the nose and palatal level to the tongue base (3, 4).

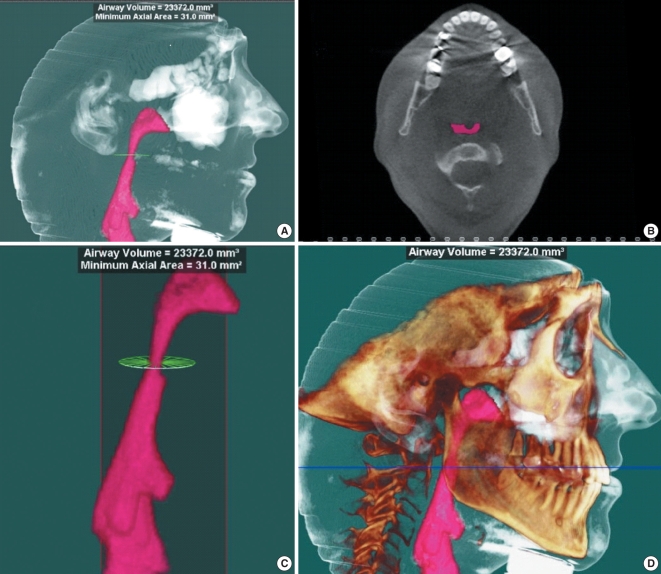

PRE-SURGICAL EVALUATION

A standard evaluation should include attended overnight polysomnography, a comprehensive history, and a head and neck physical examination. Diagnostic evaluation methods should be considered on all patients who are candidates for surgical intervention. Fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy and lateral cephalometric analysis have been the primary diagnostic tools for many years. Sleep endoscopy may have a role in diagnosis but at this time it is considered investigational, mainly due to the fact that sleep induced by medication may not be the same as non-medicated sleep (5, 6). Newer technology using 3-D imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computed tomography [CT]) coupled with software programs such as Dolphin Imaging® (Chatsworth, CA, USA) may help to assess constricted regions (minimal cross sectional areas, MCSA) as well as provide volumetric measurements of the airway (nose to larynx) (Fig. 1). Non-intrusive viscous flow modeling using steady-state numerical formulation Reynolds averaged navier-stokes (RANS), and a high fidelity unsteady large eddy simulation (LES) is being studied for future use in OSAS. Combined these two computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods can be extremely helpful in assessing sites of obstruction pre-operatively and outcomes results post-operatively. These metrics can also examine the actual airflow characteristics of the upper airway in subjects with OSAS pre and post treatment (CPAP and/or surgery) (7). Computational fluid dynamics applying RANS and LES are generally used as an investigational tool but in the future may become a routine method of airway and airflow evaluation. It is cautioned that no one test or procedure should be relied on to make diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Fig. 1.

(A) is a 3-D CT taken awake and supine with software reconstruction specifically to assess characteristics of the airway. (B) is an axial section showing the minimum cross sectional area (MCSA) of the pharyngeal airway which measures 31.0 mm3. This is a significant narrowing at that level. (C) has a total airway volume of 23,372.2 mm3 from the inlet to the outlet outlined in pink. (D) is a reconstruction of the facial skeleton along with an outline of soft tissues. This allows an exposure of the airway that is not seen in traditional radiographs.

METHODS AND TREATMENTS

The indications for treatment of OSAS are basically the same regardless of whether the patient is to be treated medically or surgically. However, the sleep study component of the surgical work up is slightly different; if surgery is proposed a full night attended polysomnogram (PSG) should be used. This is important since data from the PSG will reflect all parameters of sleep and breathing to establish a true surgical pre-treatment baseline. Snoring and EDS combined with an abnormal PSG are the main indications for treatment.

Medical

Although primary management is usually done by sleep medicine physicians, a surgeon should have a good grasp of the medical sleep protocols. Medical treatment concentrates on the most conservative methods and moves forward appropriately: sleep hygiene, weight loss, dental splints and nasal pressure devices (CPAP/BiPAP). The two most important are weight loss and pressure devices and of those two nasal pressure devices are the most successful.

Surgical

Surgical techniques for OSAS are used in centers around the world. There are many new surgical techniques that are being evaluated. Unfortunately, at present there is inadequate evidence based literature to support these techniques. In the future some of these new technologies may show sufficient safety and efficacy to be included in standard surgical management of OSAS.

Contemporary procedures

Tracheotomy

Nasal obstruction/reconstructions

-

Retropalatal obstruction/reconstructions

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP)

-

Retrolingual obstruction/reconstructions

Tongue reductions

Genioglossus advancement (GA)

Hyoid myotomy suspension (HMS)

Bi-maxillary advancement (BMA)

The contemporary surgical methods focus on procedures to treat the three major regions of obstruction in OSAS (nasal, retropalatal and retrolingual). Over the years many surgeons have developed new techniques or modified existing methods to treat these areas. The oldest procedure is tracheotomy which can be temporary or permanent and is considered as a by-pass procedure of the upper-airway. It is not well tolerated by most patients and yet can be life saving, especially in patients who have significant co-morbidities. CPAP was recognized early as a successful alternative to tracheotomy in maintaining a patent airway postoperatively in OSAS surgery, and has all but eliminated the need for that procedure in most cases (8).

Nasal obstruction/reconstruction

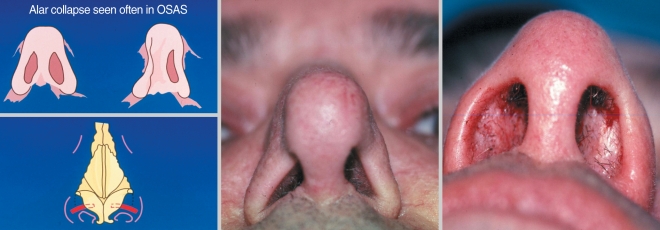

Nasal obstruction, if present, is treated with techniques that will improve the airway at the turbinates, septum and alar valve, and eliminate alar collapse and bony deformities. The procedures are used to improve CPAP usage or for relief of severe nasal obstruction. Nasal surgery for OSAS can help to decrease negative pressure breathing during sleep (9-13). It should be remembered that seldom does isolated nasal surgery resolve OSAS. An example of bilateral alar collapse is seen in Fig. 2 (14).

Fig. 2.

Alar collapse during inspiration is very common in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Alar grafts can improve patency when placed bilaterally along the alar rim.

Retropalatal obstruction/reconstruction

This is an important portion of the airway as OSAS patients often demonstrate floppy and/or bulky tissues along with excessive tissues at the lateral pharyngeal walls. The palatal tissues in OSAS are the most compliant of the upper airway inlet and hence easily collapsible during sleep. Dr. Shiro Fujita was the first to bring UPPP to the United States. This technique conservatively removed portions of the palatal edge and uvula. Over the years the technique has been modified by many surgeons (4, 15-19). Overall UPPP, when done conservatively, is an excellent surgical procedure for the retropalatal level. If applied when little or no obstruction is noted at the retrolingual area (base of tongue) its success is reasonably good. If there is undetected tongue base obstruction the control rate at the retropalatal level will be compromised. It is prudent to remove tonsils if they are in any way part of the obstruction. In patients who have been carefully selected for upper airway reconstruction and whose site of primary obstruction is at the retropalatal level (Fujita Type l) (20) the cure rate may be 80 to 90% (21). In unselected patients (Fujita Type II or III) (Table 1) this rate will fall to a low of 5 to 30% (4). It should be remembered that if the palate is part of nocturnal obstruction and not treated, but the tongue base is treated, the likelihood of overall control will be greatly lessened.

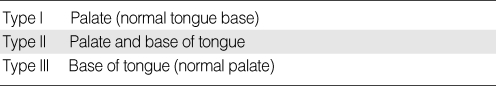

Table 1.

Classification of obstructive region by Dr. Shiro Fujita (20)

Retrolingual obstruction/reconstruction

Tongue base obstruction has been documented in OSAS by EMG studies, fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy, radiographic cephalograms, and CT or MRI imaging. A systematic evaluation of the entire airway is always necessary, especially for the tongue base, lingual tonsils, epiglottis and larynx. The obstruction of the retrolingual (base of tongue) region is a very complex problem since the elasticity of the tongue tissue while awake is different than during sleep. This region may be bypassed by tracheotomy or be treated by either making more room for the tongue or by reducing the tongue size. There are soft tissue techniques to remove the mid portion of the tongue base using laser midline glossectomy (22), partial glossectomy (23) or volumetric shrinkage by radiofrequency energy (24). Due to problems with bleeding, postop edema and speech deficits, the first two techniques have long since been abandoned by most surgeons. Radiofrequency has been shown to shrink tongue tissues (24). The technique requires multiple treatments over time with a period between treatments of 4-6 weeks. This will give sufficient time to allow healing and shrinkage. In tongue base radiofrequency (RF) treatment there may be partial relapse which can require retreatment (25). We consider RF to the tongue base to be a valuable adjunctive procedure. It is even more successful is the treatment of turbinate hypertrophy for CPAP users (26).

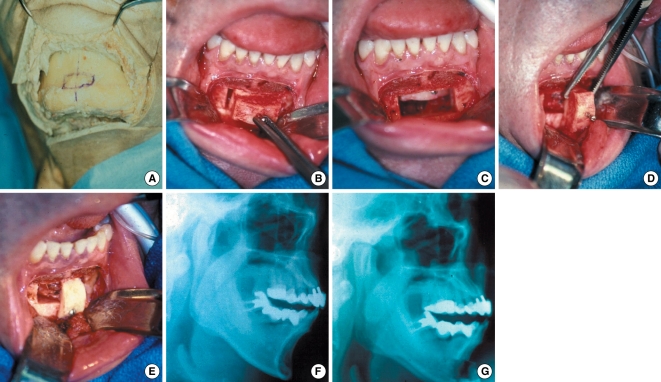

Skeletal advancements can be used to place tension on the tongue so that during sleep it does not fall as far back into the posterior airway space (PAS). This procedure is referred to as GA (Fig. 3) (27-33). This is a simple technique that does not move the teeth or jaw and therefore does not interfere with the dental bite. The genioglossus tubercle is located at the lingual portion of the chin in the floor of the mouth. The tendons of the genioglossus muscle are embedded into the tubercle. When the jaw moves forward (as in an emergency jaw thrust used in an obstructed airway) the tongue base also moves forward, increasing the PAS. The procedure has limits for two reasons. First, an osteotomy of the anterior mandible is necessary to slide the geniotubercle forward and advance the tongue. The segment can only be moved forward the thickness of the individual's chin which is usually 12-15 mm. Secondly, the outcomes of this advancement will be less favorable if the tongue muscle does not have good tension following advancement. It should be pointed out that this procedure was not developed to gain significant anterior movement of the tongue base, but instead to place sufficient tension on the tongue so it would not collapse into the PAS. In addition, this procedure does not gain any room for the tongue as the jaw itself is not moved. At this time we have no way to pre-operatively predict the amount of tension that will be achieved when the tongue is advanced. Fortunately, most advancements create adequate tension on the genioglossus muscle.

Fig. 3.

Genioglossus advancement. (A) Cadaver model with marking of rectangular cut on bone. (B) Rectangular cut (2×1 cm) with a thin sagittal saw from labial to lingual cortex to include the geniotubercle where the tendons of the genioglossus are attached. (C) Segment pushed gently into the floor of the mouth for hemostasis if needed. (D) Advance segment so the lingual cortex is pulled forward and turned enough so the lingual cortex is lying on the labial cortex. (E) The outer cortex is removed and a small titanium screw is placed at the inferior border. (F) Pre op. (G) Post op note the improvement of the airway space.

A hyoid myotomy and suspension may be used at the same time as the genioglossus advancement. However, we have abandoned most cases of combined usage since it is often unclear whether the additional technique is necessary. It is, however, still used as an adjunctive technique at our center.

A more aggressive procedure for the tongue base, usually saved for incomplete treatment or failure of the more conservative surgery above, is the forward movement of the lower jaw and midface (BMA). It gives the tongue more room and also places additional tension on the tongue base (Fig. 4). Speech has not been affected in any of these procedures. The techniques using skeletal procedures for the retrolingual level have been used by our group for the past 25 yr and have proven to be an effective and safe method for controlling upper airway collapse in OSAS. Our published clinical outcomes and cure rate for Phase I is 42% to 75% depending on the severity of the disorder (28) and similar results have been confirmed by others (34-43). Phase II (bi-maxillary surgery) has documented cure rates of 90% or greater (44-63). It is important to be aggressive in Phase II surgery as the best results are usually directly related to the distance of your bi-maxillary advancements (Fig. 5). Our definition of responder or cure for clinical outcomes can be seen in Table 2. Long term clinical outcomes published by our center in 2000 showed stable results (64). Risk management and complications should always be on the top of the list for our patients and our field (65).

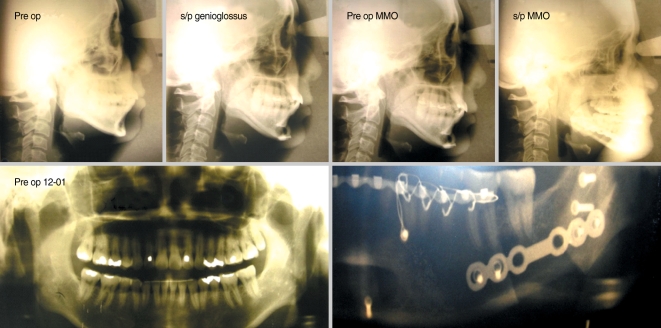

Fig. 4.

Pre and post-op bi-max: 64 yr old male with severe Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Note improvement of the posterior airway space from bi-maxillary advancement.

Fig. 5.

Forty one year old Asian woman, AHI 28.3, low sat 84%, severe EDS, BMI 22 kg/m2; surgical procedure for OSAS: BMA/GA with BMA advancement of 26 mm and GA advancement of 12 mm for a total advancement of 38 mm. Post op: AHI 2.5, low sat 91%, resolved EDS, BMI 21 kg/m2. AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; EDS: excessive daytime sleepiness; BMI: body mass index; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; BMA/GA: bi-maxillary advancement/genioglossus advancement.

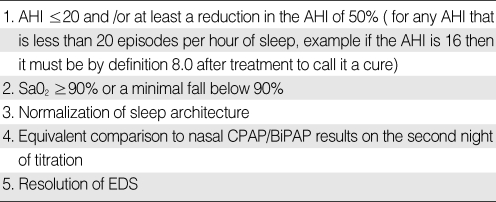

Table 2.

Definition of responder or cure: (Powell-Riley) Criteria must include 1-3 below or 4

AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; EDS: excessive daytime sleepiness.

Twenty years ago we developed a Phase I and Phase II treatment protocol predicated on evidence-based medicine principles. It is described as the Stanford University Powell-Riley Protocol. The rationale for this protocol was: decreased risk of over operating, treated conservatively because outcomes are difficult to predict, decreased hospital stay, limited postoperative risk, caused less trauma and pain and was better accepted by most patients.

Powell-Riley phase I protocol

Three regions of the upper airway are treated as directed by the clinical work up using the most conservative surgery for each, but only including treatment at that level if it was considered sufficiently obstructed.

Nasal: Correct nasal obstruction depending on anatomical deformity (septum, turbinates, nasal valve deformities, alar collapse and bony deformities).

Retropalatal: UPPP or equivalent and tonsillectomy if tonsils present.

Retrolingual: Genioglossus advancement, with or without hyoid myotomy and suspension.

After phase one is completed a period of 4-6 months is allowed for sufficient healing, weight stabilization and neurologic equilibration. Then a repeat polysomnogram accompanied with a sleep assessment and clinical examination is done to assess the clinical outcomes. Those patients who are unchanged or incompletely treated are offered either further surgery (Phase II) or medical management (CPAP).

Powell-Riley phase II protocol

If the protocol has been followed to this point the only region that should be left incompletely treated is retrolingual (base of tongue). A choice now is made among the remaining methods: Bi-maxillary advancement surgery, tracheotomy or nasal CPAP. Other techniques that could be considered to make additional room for the tongue are the laser midline glossectomy and lingualplasty, or partial glossectomy, although these procedures are seldom used by our center for Phase II. Base of tongue reduction using radiofrequency may become an adjunctive alternative to Bi-maxillary advancement surgery in some very select patients.

Powell's pearl "the algorithm"

The question I am most often asked by my patients, or while teaching residents, visitors or travelling is, what is your algorithm for the treatment of OSAS? From the surgical standpoint the answer is that there is no such algorithm that can be applied to all patients. It is almost impossible to state, even in an individual patient, because of the multifactorial etiologies in this syndrome. This is one of the reasons a systematic diagnostic and phased protocol is applied at our sleep center, but this does not suggest an algorithm that would serve all patients. The question will continue to be asked until our field gains sufficient knowledge and understanding of sleep to permit a reliable and consistent answer.

Footnotes

I have no financial disclosure or conflict of interest with any person or company.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993 Apr;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhlo W, Doll E, Franck MC. Successful management of Pickwickian syndrome using long-term tracheostomy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1969 Jun 13;94(24):1286–1290. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1111209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell N, Riley R. A surgical protocol for sleep disordered berathing. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1995 Aug;7(3):345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996 Feb;19(2):156–177. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachar G, Feinmesser R, Shpitzer T, Yaniv E, Nageris B, Eidelman L. Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal obstruction in sleep disordered breathing patients, evaluated by sleep endoscopy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Nov;265(11):1397–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Bruno K, Goldberg AN, McCulloch CE, Kezirian EJ. Test-retest reliability of drug-induced sleep endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 May;140(5):646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mylavarapu G, Murugappan S, Mihaescu M, Kalra M, Khosla S, Gutmark E. Validation of computational fluid dynamics methodology used for human upper airway flow simulations. J Biomech. 2009 Jul 22;42(10):1553–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C, Murcia GN. Obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure, and surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988 Oct;99(4):362–369. doi: 10.1177/019459988809900402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayal VS, Phillipson EA. Nasal surgery in the management of sleep apnea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985 Nov–Dec;94(6 Pt 1):550–554. doi: 10.1177/000348948509400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millman RP. Sleep apnea and nasal patency. Am J Rhinol. 1988;2(4):177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen KD, Kern EB, Westbrook PR. Sleep and breathing disturbance secondary to nasal obstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981 Sep–Oct;89(5):804–810. doi: 10.1177/019459988108900522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Series F, St Pierre S, Carrier G. Effects of surgical correction of nasal obstruction in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Nov;146(5 Pt 1):1261–1265. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suratt PM, Turner BL, Wilhoit SC. Effect of intranasal obstruction on breathing during sleep. Chest. 1986 Sep;90(3):324–329. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troell RJ, Powell NB, Riley RW, Li KK. Evaluation of a new procedure for nasal alar rim and valve collapse: nasal alar rim reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Feb;122(2):204–211. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairbanks DN. Operative techniques of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999 Nov;78(11):846–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodson BT, Toohill RJ. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1993 Mar;103(3):269–276. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell N, Riley R, Guilleminault C, Troell R. A reversible uvulopalatal flap for snoring and sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996 Sep;19(7):593–599. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.7.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker RP, Grigg-Damberger MM, Gopalsami C, Totten MC. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: results in 170 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995 Sep;105(9 Pt 1):938–943. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199509000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, Li K, Blumen MB, Guilleminault C. Radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate in subjects with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 1998 May;113(5):1163–1174. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic azbnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981 Nov–Dec;89(6):923–934. doi: 10.1177/019459988108900609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sher AE, Thorpy MJ, Shprintzen RJ, Spielman AJ, Burack B, McGregor PA. Predictive value of Muüller maneuver in selection of patients for uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1985 Dec;95(12):1483–1487. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita S, Woodson BT, Clark JL, Wittig R. Laser midline glossectomy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1991 Aug;101(8):805–809. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mickelson SA, Rosenthal L. Midline glossectomy and epiglottidectomy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1997 May;107(5):614–619. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, Blumen MB, Guilleminault C. Radiofrequency volumetric reduction of the tongue. A porcine pilot study for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1997 May;111(5):1348–1355. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li KK, Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Temperature-controlled radiofrequency tongue base reduction for sleep-disordered breathing: long-term outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Sep;127(3):230–234. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.126900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell NB, Zonato AI, Weaver EM, Li K, Troell R, Riley RW, et al. Radiofrequency treatment of turbinate hypertrophy in subjects using continuous positive airway pressure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical pilot trial. Laryngoscope. 2001 Oct;111(10):1783–1790. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200110000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Inferior mandibular osteotomy and hyoid myotomy suspension for obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 55 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989 Feb;47(2):159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(89)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993 Feb;108(2):117–125. doi: 10.1177/019459989310800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994 Dec;111(6):717–721. doi: 10.1177/019459989411100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramirez SG, Loube DI. Inferior sagittal osteotomy with hyoid bone suspension for obese patients with sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996 Sep;122(9):953–957. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890210031008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson NT, Chinn J. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy with genioglossus advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1994 Jan;105(1):278–283. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.1.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee NR, Givens CD, Jr, Wilson J, Robins RB. Staged surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 35 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999 Apr;57(4):382–385. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. The hypopharynx: upper airway reconstruction in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. In: Fairbanks DN, Fujita S, editors. Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Raven Press, Ltd.; 1994. pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilaseca I, Morello A, Montserrat JM, Santamaría J, Iranzo A. Usefulness of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with genioglossus and hyoid advancement in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002 Apr;128(4):435–440. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fibbi A, Ameli F, Brocchetti F, Peirano M, Garaventa G, Presta A, et al. Combined genioglossus advancement (ACMG): inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy with genioglossus advancement and stabilization with suture in patients with OSAS. Preliminary clinical results. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2002 Jun;22(3):153–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neruntarat C. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy under local anesthesia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Jul;129(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980300094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dattilo DJ, Drooger SA. Outcome assessment of patients undergoing maxillofacial procedures for the treatment of sleep apnea: comparison of subjective and objective results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 Feb;62(2):164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin S, Yi H, Lu W, Wu H, Guan J, Cao Z, et al. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid suspension plus uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for severe OSAHS. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2005 Aug;19(15):673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi HL, Yin SK, Lu WY, Wu HM, Guan J, Cao ZY, et al. Effectiveness of combined surgery for treating severe obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006 Feb;41(2):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobowitz O. Palatal and tongue base surgery for surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Aug;135(2):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richard W, Kox D, den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. One stage multilevel surgery (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, hyoid suspension, radiofrequent ablation of the tongue base with/without genioglossus advancement), in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Apr;264(4):439–444. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foltan R, Hoffmannova J, Pretl M, Donev F, Vlk M. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy in treating obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: a follow-up study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2007 Jun–Jul;35(4-5):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos JF, Junior, Abrahao M, Gregorio LC, Zonato AI, Gumieiro EH. Genioplasty for genioglossus muscle advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome and mandibular retrognathia. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Jul–Aug;73(4):480–486. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30099-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waite PD, Wooten V, Lachner J, Guyette RF. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery in 23 patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989 Dec;47(12):1256–1261. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90719-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waite P, Shettar S. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery: a cure for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1995;7(2):327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochban W, Brandenburg U, Peter JH. Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea by maxillomandibular advancement. Sleep. 1994 Oct;17(7):624–629. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.7.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hochban W, Conradt R, Brandenburg U, Heitmann J, Peter JH. Surgical maxillofacial treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Mar;99(3):619–626. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner I, Coiffier T, Sequert C, Lachiver X, Fleury B, Chabolle F. Surgical treatment of severe sleep apnea syndrome by maxillomandibular advancing or mental tranposition. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2000 Jun;117(3):137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bettega G, Pepin JL, Veale D, Deschaux C, Raphael B, Levy P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: fifty-one consecutive patients treated by maxillofacial surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Aug;162(2 Pt 1):641–649. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9904058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powell N, Guilleminault C, Riley R, Smith L. Mandibular advancement and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1983 Nov–Dec;19(6):607–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guilleminault C, Riley R, Powell N. Sleep apnea in normal subjects following mandibular osteotomy with retrusion. Chest. 1985 Nov;88(5):776–778. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial surgery and obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 80 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989 Sep;101(3):353–361. doi: 10.1177/019459988910100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial surgery and nasal CPAP: a comparison of treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1990 Dec;98(6):1421–1425. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.6.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conradt R, Hochban W, Brandenburg U, Heitmann J, Peter JH. Long-term follow-up after surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea by maxillomandibular advancement. Eur Respir J. 1997 Jan;10(1):123–128. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10010123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prinsell JR. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery in a site-specific treatment approach for obstructive sleep apnea in 50 consecutive patients. Chest. 1999 Dec;116(6):1519–1529. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li KK, Powell NB, Riley RW, Zonato A, Gervacio L, Guilleminault C. Morbidly obese patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea: is airway reconstructive surgery a viable treatment option? Laryngoscope. 2000 Jun;110(6):982–987. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li KK, Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillomandibular advancement for persistent obstructive sleep apnea after phase I surgery in patients without maxillomandibular deficiency. Laryngoscope. 2000 Oct;110(10 Pt 1):1684–1688. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hendler BH, Costello BJ, Silverstein K, Yen D, Goldberg A. A protocol for uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, mortised genioplasty, and maxillomandibular advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an analysis of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001 Aug;59(8):892–897. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.25275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goh YH, Lim KA. Modified maxillomandibular advancement for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2003 Sep;113(9):1577–1582. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200309000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smatt Y, Ferri J. Retrospective study of 18 patients treated by maxillomandibular advancement with adjunctive procedures for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Craniofac Surg. 2005 Sep;16(5):770–777. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000179746.98789.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu XF, Zhu M, He JD, Zhang R, Li ZY, Sun HX. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and maxillomandibular advancement for obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome: a preliminary report. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007 Apr;42(4):199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessler P, Ruberg F, Obbarius H, Iro H, Neukam FW. Surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2007 Apr;11(2):81–88. doi: 10.1007/s10006-007-0051-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lye KW, Waite PD, Meara D, Wang D. Quality of life evaluation of maxillomandibular advancement surgery for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 May;66(5):968–972. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riley RW, Powell NB, Li KK, Troell RJ, Guilleminault C. Surgery and obstructive sleep apnea: long-term clinical outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Mar;122(3):415–421. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C, Pelayo R, Troell RJ, Li KK. Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: risk management and complications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997 Dec;117(6):648–652. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]