Abstract

Examining the behavioral consequences of selective CNS neuronal activation is a powerful tool for elucidating mammalian brain function in health and disease. Newly developed genetic, pharmacological, and optical tools allow activation of neurons with exquisite spatiotemporal resolution; however, the inaccessibility to light of widely-distributed neuronal populations and the invasiveness required for activation by light or infused ligands limit the utility of these methods. To overcome these barriers, we created transgenic mice expressing an evolved G protein-coupled receptor (hM3Dq) selectively activated by the pharmacologically inert, orally bioavailable drug clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). Here, we expressed hM3Dq in forebrain principal neurons. Local field potential and single neuron recordings revealed that peripheral administration of CNO activated hippocampal neurons selectively in hM3Dq-expressing mice. Behavioral correlates of neuronal activation included increased locomotion, stereotypy, and limbic seizures. These results demonstrate a novel and powerful chemical-genetic tool for remotely controlling the activity of discrete populations of neurons in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Methods to examine the behavioral consequences of activation of neuronal ensembles are powerful tools for understanding brain function, as exemplified by Wilder Penfield’s pioneering studies of focal electrical stimulation of human cortex (Penfield and Jasper, 1954). The development of genetic and optical tools to visualize and activate neuronal activity with exquisite temporal resolution using microbial opsins (e.g. channelrhodopsin-2, halorhodopsin, Volvox carteri channelrhodopsin, optoXRs) has provided an expanding toolbox for decoding the neuronal correlates of brain function (Berndt et al., 2009; Boyden et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2007; Airan et al., 2009). However, the equipment, technological expertise, and invasiveness required for light-mediated activation, together with the relative inaccessibility to light of scattered neuronal populations, limits the potential applicability of these methods. Ideally, noninvasive remote control of neuronal activity in the mammalian brain would provide a valuable tool for elucidating how the activity of discrete populations of neurons and local circuits underlies behavior in health and disease.

Accordingly, we sought to develop a chemical-genetic approach to control neuronal activity noninvasively in the mammalian brain by regulating signaling through a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). Others have worked toward similar goals (see Luo et al., 2008 for review), and our work represents an effort to advance this field. In addition to the opsin-receptor chimeras (optoXRs) mentioned above, existing approaches to manipulating GPCR signaling pathways in neurons both in vitro and in vivo include ectopic expression of either GPCRs with engineered binding sites (e.g., Receptors Activated Solely by Synthetic Ligands, or RASSLs [Redfern et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2003]) or non-native GPCRs [e.g., the Drosophila allatostatin receptor (AlstR; Lechner et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2006)]. These approaches represent important advances for the pharmacological manipulation of neuronal activity and are valuable for many applications. However, continued improvements are needed to facilitate regulation of activity of discrete populations of CNS neurons selectively and non-invasively in vivo. RASSLs, for example, are activated by non-selective, pharmacologically active small molecules and in some tissues exhibit high levels of signaling in the absence of exogenous small molecule agonists. Indeed, ectopic expression of RASSLs can result in pathologic phenotypes (Hsiao et al., 2008; Peng et al., 2008; Redfern et al., 2000; Sweger et al., 2007). The AlstR, while displaying no evidence of basal signaling, does not allow for remote manipulations of neuronal activity as its ligand is unlikely to cross the blood-brain barrier and must be directly infused into brain tissue (Tan et al., 2006). Moreover, the AlstR is not used for neuronal activation as its activity couples only to neuronal silencing.

To advance these methods, we sought to develop a system for neuronal regulation in which: 1) the exogenous ligand would be pharmacologically inert; 2) the exogenous ligand could be administered in the periphery and cross the blood-brain barrier to access receptor in deep brain structures and/or widely-distributed neuronal populations; 3) receptor expression alone would not induce pathology; 4) neuronal activity could be both increased and decreased; and 5) both spatial and temporal resolution would be sufficient to facilitate study of brain function in health and disease.

With this ideal in mind, we used directed molecular evolution to develop a new generation of RASSLs, which we refer to as DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drug), derived from the human muscarinic receptors (Armbruster et al., 2007; Conklin et al., 2008; Pei et al., 2008). This molecular evolution resulted in reduced potency and efficacy of the native ligand (acetylcholine) and high potency and efficacy of the orally bioavailable (Bender et al., 1994), pharmacologically inert ligand, clozapine-n-oxide (CNO) (Armbruster et al., 2007; Nawaratne et al., 2008). Importantly, these DREADDs lack detectable constitutive activity in vitro (Armbruster et al., 2007) and, thus, provide an attractive receptor-effector complex for modifying neuronal activity remotely. Furthermore, this system allows for manipulation of Gi, Gq, and Gs -coupled pathways (Pei et al., 2008).

Here, as a proof-of-concept, we describe a method by which the activity of identified populations of CNS neurons is regulated noninvasively in vivo. For these studies, we produced mice that express the Gq-coupled human M3 muscarinic DREADD (hM3Dq) specifically in principal neurons within the forebrain, particularly in the hippocampus and cortex, by driving expression in double-transgenic mice in a reversible fashion with the CAMKIIα tet transactivator (tTA; Mayford et al., 1996). We then recorded local field potential (LFP) and single unit activity within hippocampus and showed a correlation between changes in neuronal activity and behaviors induced by the peripheral administration of CNO in mutant mice. We demonstrate CNO-mediated neuronal activation within hippocampus, as measured by dose-dependent changes in the LFP and increases in the firing rate of interneurons (likely driven by principal neuron firing). Moreover, excessive activation of this pathway by high-dose CNO resulted in limbic seizures and status epilepticus. The selective activation of GPCRs in defined neuronal populations afforded by this chemical-genetic approach provides an improved tool for the study of mammalian brain function in health and disease.

RESULTS

Generation of hM3Dq-expressing Mice

Previously, we showed in vitro that hM3Dq signals exclusively via the canonical Gq pathway in non-neuronal cell types (Armbruster et al., 2007; Conklin et al, 2008). To assess whether hM3Dq couples to Gq in mixed neuronal-glial cultures, we visualized calcium flux with a calcium-sensitive dye in primary cultures of mouse postnatal day 1 (P1) hippocampal cells infected with hM3Dq-transducing lentivirus. CNO stimulated calcium transients only in those neurons expressing hM3Dq (identified by an IRES-driven mCherry reporter) and was without effect in uninfected neurons (Figure S1 and see Supplemental Videos SV1 and SV2).

Having thus demonstrated that hM3Dq conferred the ability to stimulate neuronal Gq-signaing in vitro, we sought to determine whether expression of hM3Dq could alter neuronal function in vivo. We first generated transgenic mice expressing tetracycline-sensitive HA-tagged hM3Dq using the Tet-off system (i.e. transgene expression is repressed upon administration of tetracycline or its analog, doxycycline). This system allows for inducible, spatiotemporally-regulated transgene expression. Pronuclear injection of B6SJL hybrid mouse oocytes with Tet Response Element (TRE)-hM3Dq DNA (Figure 1A) resulted in the birth of 35 mouse pups, of which ten carried the transgene. To determine whether we could achieve brain region-specific expression of hM3Dq protein, we crossed TRE-hM3Dq founders with CaMKIIα-tTA mice in which tTA expression is targeted to principal neurons mainly in cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (Mayford et al., 1996) (Figure 1A). We removed the brains from F1 adults and immunoprecipitated HA-hM3Dq protein from membrane fractions of whole brain (minus cerebellum) homogenates. Initial immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitates revealed expression of HA-hM3Dq in double-transgenic (both TRE-hM3Dq and tTA transgenes) F1 progeny from two of the founder mice (data not shown). Subsequent studies of mutant F1 progeny from both sets of founder mice did not reveal any differences in receptor expression or activity; therefore, we chose only one of the founder lines (Line 1) for subsequent studies. Hereafter, we refer to the mice from this line, which express HA-hM3Dq driven by the CaMKIIα promoter, as hM3Dq mice.

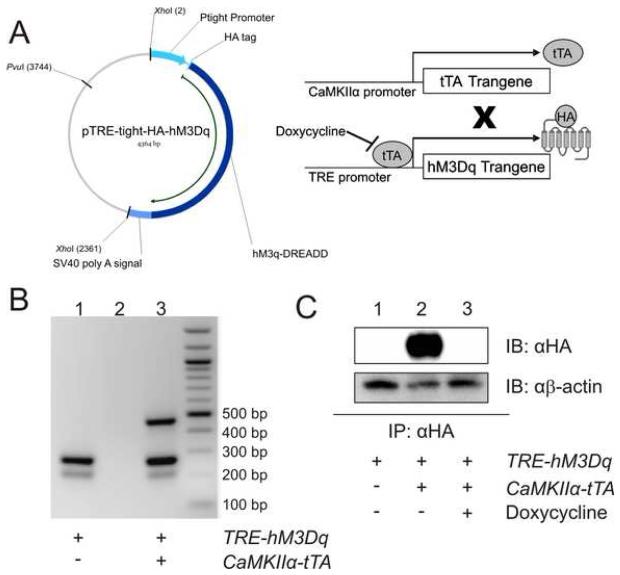

Figure 1. Generation of transgenic mice with inducible expression of HA-hM3Dq.

A) Pronuclear injection of murine oocytes with the 2.36 kb XhoI restriction digest fragment containing HA-hM3Dq downstream of the Ptight TRE promoter produced a tet-responsive mouse line. When crossed with a CaMKIIα-tTA tet-driver line, tTA protein, produced TRE promoter to activate transcription of HA-hM3Dq; tTA binding to TRE is inhibited by doxycycline. B) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of DNA amplified from tail clips of a single-transgenic (TRE-hM3Dq) mouse (Lane 1), water (Lane 2), and a double-transgenic mouse (Lane 3) reveals presence of CaMKIIα-tTA transgene (450 bp), TRE-hM3Dq transgene (250 bp), and murine genomic DNA control band (200 bp). C) Immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblot does not detect any transgene in single-transgenic mice (TRE-hM3Dq transgene only, Lane 1) or double transgenic (hM3Dq) mice maintained on 200 mg/kg doxycycline (Lane 3), in contrast to hM3Dq mice maintained on normal chow in which HA protein is detectable (Lane 2). β-actin was detected as a loading control. Mouse brains (with cerebellum removed) were homogenized and the membrane-containing fraction was isolated through differential centrifugation. HA-affinity matrix immunoprecipitated HA-tagged proteins which were then separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blot with anti-HA antibody.

Having determined that the CaMKIIα-tTA transgene effectively drives hM3Dq expression in the brain, we next sought to repress hM3Dq expression by doxycycline administration. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses similar to those described above revealed undetectable hM3Dq expression in both hM3Dq F1 progeny fed doxycycline-containing chow (200 mg/kg) for one month and single-transgenic (TRE-hM3Dq transgene only) mice fed normal chow (Figure 1C). These findings demonstrated, first, that doxycycline successfully repressed tTA-driven hM3Dq expression in vivo and, second, that hM3Dq expression could be temporally regulated.

Characterization of hM3Dq Expression

To examine the spatial distribution of transgene expression, we prepared coronal brain sections for immunofluorescence and probed them with an anti-HA antibody. We found that immunofluorescence was most intense in the cortex and hippocampus (Figure 2A-C), as expected for CaMKIIα-tTA-driven transgene expression (Mayford et al., 1996). Within the hippocampus, immunofluorescence was most intense in CA1 strata radiatum and oriens (Figure 2A), a pattern consistent with expression in the apical and basal dendrites of CA1 pyramids. Confocal immunofluorescent microscopic analysis of single CA1 pyramidal cells confirmed immunoreactivity in the soma and apical and basal dendrites (Figure 2B). Apical dendrite immunoreactivity was also detected in cortex (Figure 2C). Importantly, inclusion of doxycycline in the diet resulted in no detectable immunoreactivity in either cerebral cortex or CA1 (compare Figure 2D and E). Additionally, a Nissl stain revealed no overt structural differences between WT and hM3Dq mice (Figure S2).

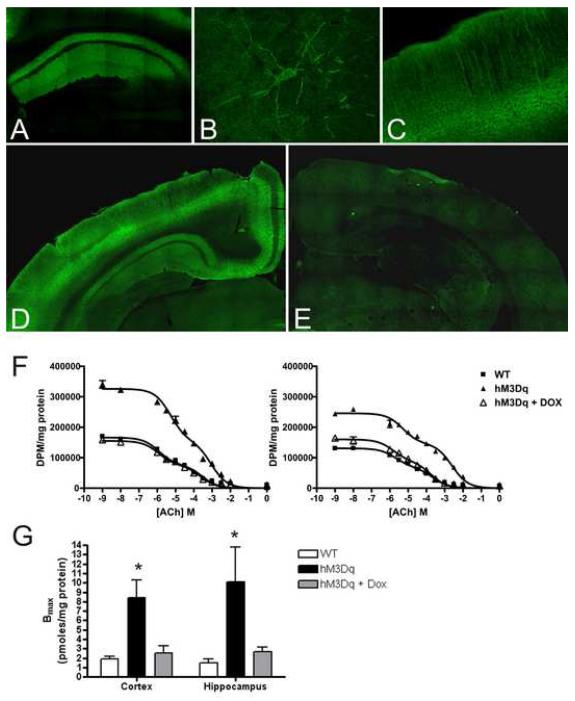

Figure 2. Receptor expression and localization in transgenic mouse brains.

A-E) Immunohistochemistry for HA-tagged protein in coronal sections from hM3Dq mouse brain; HA immunoreactivity localizes to the CA1 region of the hippocampus (A) where staining is specifically observed in the apical and basal processes of pyramidal neurons (B). In the cortex (C), immunoreactivity is detected in apical dendrites. HA immunoreactivity is present in mutant mice fed normal chow (D) but not in mice maintained on 200 mg/kg doxycycline (E). F) [3H]QNB binding to cortical (left panel) and hippocampal (right panel) mouse brain membranes was determined by radioligand competition-binding assays. Competition curves depict data from one representative animal of each group. Data were fit simultaneously by non-linear regression. G) Mice expressing hM3Dq protein have a higher Bmax of [3H]QNB binding than wild-type mice or hM3Dq mice on doxycycline. *p < 0.05 by F test.

To obtain independent evidence of hM3Dq expression in the hM3Dq mice, we measured the Bmax of [3H] quinuclidinyl benzilate (QNB) binding in cortical and hippocampal membranes from wild-type and hM3Dq mice. Radioligand competition binding isotherms were first modeled based on prior affinity estimates obtained with cloned wild-type and hM3Dq receptors expressed in vitro (KD=0.05 nM at hM3; KD=1.6 nM at HA-hM3Dq; Armbruster et al., 2007). We conducted computerized simulations with Prism 4.0 using different concentrations of [3H]QNB and various ratios of native to transgenic receptor expression in order to determine the optimal concentration of [3H]QNB, a non-selective muscarinic antagonist, for detection of both endogenous muscarinic receptors and hM3Dq receptors. Having determined the optimal assay conditions, competition curves were then obtained using unlabeled acetylcholine (which binds hM3Dq albeit with lower affinity compared to wild type mAChRs; Armbruster et al., 2007) and [3H]QNB. Data were fit simultaneously by LIGAND (Munson and Rodbard, 1980) using weighted non-linear regression analysis and a two-site model, which best described all data sets (by F-test). In hM3Dq tissue, a distinct site emerged for which ACh had low affinity (1.0 mM in cortex, 1.7 mM in hippocampus) (Figure 2F, Table S1). The affinity of ACh for this site was similar to that of ACh for cloned hM3Dq, but not wild-type muscarinic, receptors (Armbruster et al., 2007). The inclusion of doxycycline in the diet of hM3Dq mice eliminated this low-affinity site (Table S1). We concluded that (1) this low-affinity ACh site accounted for the difference in Bmax between hM3Dq and wild-type or doxycycline-treated tissue, and (2) the difference in Bmax was due to hM3Dq transgene expression. Indeed, computerized non-linear least-squares regression analysis taking into account the difference in affinity of [3H]QNB for the hM3Dq and native mAChRs revealed an increase of four- and seven-fold in the Bmax of [3H]QNB binding to membranes isolated from cortex and hippocampus, respectively, of hM3Dq compared to WT mice (Figure 2G, Table S1). These data indicate that hM3Dq was expressed in both cortex and hippocampus at levels greater than endogenous muscarinic receptors.

Behavioral Analyses of hM3Dq Mice in the Absence of CNO

A major goal of the evolution of the second generation of RASSLs was to minimize constitutive activity of hM3Dq and also to eliminate the activation of hM3Dq by endogenous ACh, thus limiting hM3Dq signaling in vivo in the absence of CNO. When expressed in yeast, cultured mammalian cells, and mouse pancreatic β-cells, no detectable constitutive activity of hM3Dq in the absence of CNO was found (Armbruster et al., 2007; Guettier et al., submitted). To test whether hM3Dq expression in vivo modified behavior in the absence of its exogenous activating ligand (CNO), we examined mouse appearance and behavior through a battery of neurobehavioral tests on single-transgenic (TRE-hM3Dq transgene only) and hM3Dq mice (see Supplementary Methods and Figures S3-7; n=11 littermate pairs). No qualitative differences were evident between control and hM3Dq mice. Specifically, the two groups were similar in observations regarding size, overall morphology, coat condition, body posture and gait, reflex response to gentle touch with a cotton swab on the whiskers or eyes, balance in an empty, shifting plastic cage, ability to climb a pole or walk across an elevated dowel, grip-strength in a wire-hang test, and responses during 20 seconds of tail-suspension.

A variety of quantitative assessments of behavior were also performed. We quantified motor coordination using an accelerating rotarod, the results of which revealed no significant differences between hM3Dq and control mice (Figure S3). Likewise, no significant differences were detected in the elevated plus maze, acoustic startle response, pre-pulse inhibition of startle responses (PPI), latency to locate a food reward buried in bedding, the Morris water maze visual cue test, or acquisition and reversal learning in the Morris water maze (Figures S4-6).

In contrast to these measures that revealed no differences between the two genotypes, we did find subtle but unremarkable differences with respect to activity in an open field (Figure S7). hM3Dq mice demonstrated a tendency toward reduced locomotor activity as measured by total distance traveled in a locomotor chamber [F(1,20)=6.15, p<0.05] (Figure S7A). They further demonstrated fewer fine, stereotypic movements [F(1,20)=6.63, p=0.0181] (Figure S7B). However, no differences in rearing movements or in time spent in the center of the open field were detected (data not shown). Apart from the mild reduction of spontaneous locomotor activity, the hM3Dq mice were similar to controls on an extensive battery of tests of diverse behaviors, implying that overexpression of a Gq-coupled receptor has minimal untoward effects.

In Vitro CA1 Pyramidal Cell Response to CNO

After characterizing the behavior of hM3Dq mice in the absence of exogenous ligand, we sought to determine the effects of hM3Dq receptor activation by CNO. We first asked whether neurons from hM3Dq animals would respond to CNO. To address this question, we isolated acute hippocampal slices from hM3Dq and littermate control animals and performed whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons in the absence and presence of bath applied CNO. To isolate membrane potential responses from synaptic responses, we performed these recordings in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX). We found that bath application of CNO (500 nM) to hippocampal slices isolated from hM3Dq mice depolarized CA1 pyramidal cells by 8.0 ± 1.8 mV compared with baseline membrane potentials (p<0.01; n=7 neurons from 5 animals; Figure. 3Ai, iii). In contrast to these findings in hM3Dq mice, we found no significant change in membrane potential of CA1 pyramidal neurons of hippocampal slices isolated from control (either single transgenic or wild-type) mice (p>0.05, n=7 neurons from 5 animals; Figure 3Aii-iii). We additionally asked whether bath application of CNO to hippocampal slices isolated from hM3Dq mice would increase the firing rate of CA1 pyramidal neurons. To that end, we performed whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal cells in the absence of TTX. We found that bath application of CNO (500 nM) in the absence of TTX increased the firing rate of CA1 pyramidal cells (n=8 neurons from 4 animals; Figure 3C).

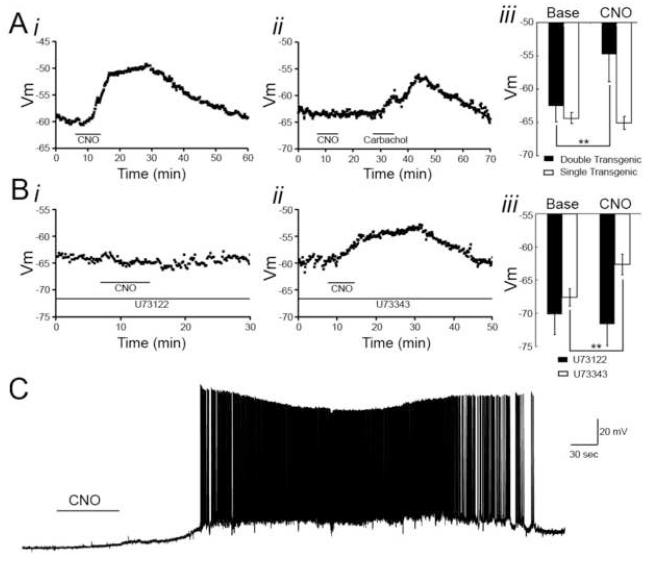

Figure 3. CNO effects on CA1 pyramidal neurons recorded in vitro.

Acute hippocampal slices were isolated from hM3Dq and control animals, and CA1 pyramidal cells were recorded from in the whole-cell configuration. Cells were held at resting membrane potential in the presence (A-B) or absence (C) of TTX, and CNO was bath applied. A, Bath application of CNO (500 nM) depolarized CA1 pyramidal cells from hM3Dq animals (i), but CNO did not affect resting membrane potential of CA1 pyramidal cells from control animals. However, bath application of carbachol (5 μM) did depolarize CA1 pyramidal cells from control animals (ii). Aiii, Population data from hM3Dq and control animals showing the mean resting membrane potential of CA1 pyramidal cells before and in the presence of CNO [500 nM for hM3Dq (n=7 cells from 5 animals) and 1 μM for control animals (n=7 cells from 5 animals)]. B, In the presence of an active PLC inhibitor (U73122, 10μM) the CNO-induced depolarization of hM3Dq CA1 pyramidal neurons was blocked (i), but in the presence of an inactive analog (U73343, 10μM) CNO was capable of depolarizing hM3Dq CA1 pyramidal neurons (ii). Biii, Population data showing change in resting membrane potential of hM3Dq CA1 pyramidal neurons induced by CNO (500nM) in the presence of U73122 (n=6 cells from 4 animals) or U73343 (n=4 cells from 4 animals). C, Bath application of CNO (500 nM) to hippocampal slices isolated from hM3Dq animals in the absence of TTX resulted in increased firing frequency and recurrent bursting.

Because Gq signaling can affect membrane conductances through phospholipase C (PLC)-dependent mechanisms, we tested the dependence of the CNO-evoked depolarization on PLC. We performed whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal cells in acute slices isolated from hM3Dq animals in the presence of TTX and the PLC inhibitor, U73122 (10 μM), and then bath applied CNO (500nM). We found that in the presence of U73122, CNO had no significant effect on the membrane potential of CA1 pyramidal cells (p>0.05, n=6 neurons from 4 animals; Figure 3Bi, iii). By contrast, in the presence of U73343 (10 μM), the inactive analog of U73122, CNO produced a significant depolarization of CA1 pyramidal neurons by 5.0 ± 0.72 mV (p<0.01, n=4 neurons from 4 animals; Figure 3Bii-iii). These findings indicate that CNO-induced activation of hM3Dq depolarizes and increases the firing rate of CA1 pyramidal neurons through a PLC-dependent mechanism.

Behavioral Response of hM3Dq mice to CNO

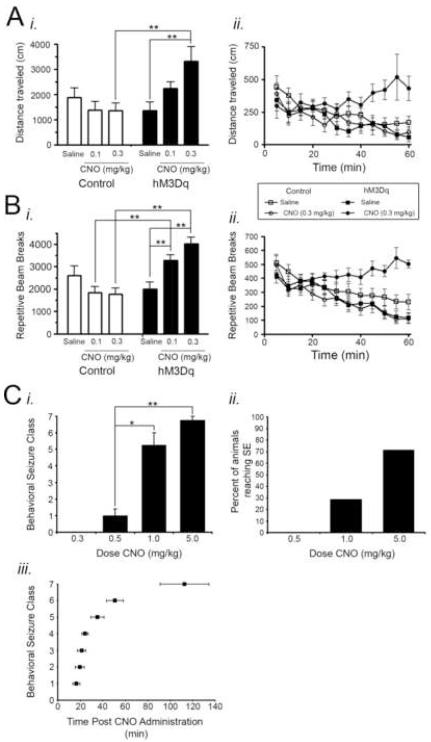

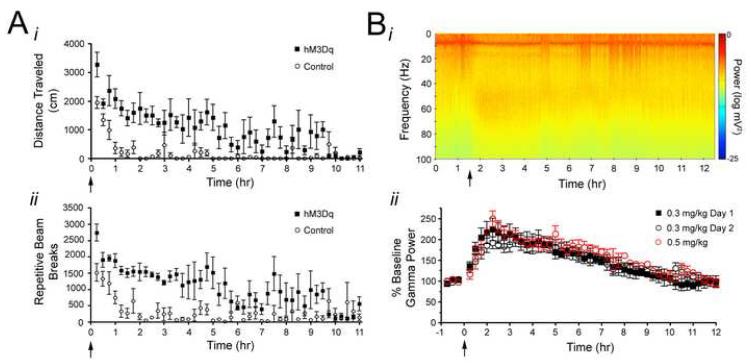

Treatment of hM3Dq but not WT mice with CNO induced striking behavioral effects. Using a cohort of adult mice distinct from that in which baseline behavioral characterization was performed, we measured ambulation and episodes of repetitive beam breaks (generally representing fine movements or stereotypic behaviors) following peripheral administration of vehicle (saline) and low dose (0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) CNO (n=10 hM3Dq; n=14 controls). Among hM3Dq mice, significant behavioral effects were noted. When CNO was administered, activity (both total ambulation and repetitive beam breaks) increased in a dose-dependent fashion among hM3Dq mice and exceeded control levels. The administration of 0.1 mg/kg CNO resulted in a significant increase in repetitive beam breaks (p<0.01) and a trend toward a significant increase in total locomotion in hM3Dq mice relative to controls. Administration of 0.3 mg/kg CNO produced a statistically significant increase in both total locomotion and repeated beam breaks in hM3Dq mice relative to controls (p<0.01; Figure 4Ai, Bi). Furthermore, the increases in locomotion and repetitive beam breaks following CNO administration occurred in a time-dependent manner such that locomotor activity gradually increased with time relative to controls (Figure 4Aii, Bii), and the increase in locomotor activity persisted >9 hours (Figure 7A; n=4 hM3Dq; n=4 controls). These data provide behavioral evidence of neuronal activation by CNO in hM3Dq mice and demonstrate the long duration of CNO activity in hM3Dq animals.

Figure 4. Behavioral consequences of CNO administration.

A-B, Effect of CNO administration on locomotor behavior in control and hM3Dq mice (n=10 hM3Dq and 14 control mice). CNO increased total locomotor activity (A) and repetitive beam breaks (B) in a dose-dependent (Ai, Bi) and time-dependent (Aii, Bii) manner in hM3Dq mice relative to control animals. For Aii and Bii, CNO was administered at time 0 following a 20 minute habituation period in the locomotor chamber. C, Behavioral seizure classes evoked by CNO administration (n=7 hM3Dq animals). All data presented here were measured during the 3 hours following CNO administration when SE did not occur and during the 3 hours following SE onset when SE did occur. Ci, Maximum behavioral seizure class elicited by various doses of CNO. No seizures were elicited by doses less than 0.5 mg/kg CNO. Cii, Percent of animals in which SE occurred at various doses of CNO. SE did not result from doses less than 1 mg/kg. Ciii, Latency from CNO administration to first occurrence of each behavioral seizure class for animals administered 5 mg/kg CNO. * represents p<0.05; ** represents p<0.01.

Figure 7. Behavioral and in vivo electrophysiological timecourse of CNO effects in hM3Dq animals.

A, Timecourse of CNO effects on locomotor activity, as measured by total distance traveled (i) and repeated beam breaks (ii), showing the latency to recovery of elevated locomotor activity following administration of 0.3 mg/kg CNO, which was administered at time 0 (n=4 littermate pairs). B, Timecourse of CNO effects on gamma power measured from the hippocampal LFP showing the latency to recovery of gamma power to baseline levels. Bi, Representative spectrogram of LFP from hM3Dq animal administered 0.3 mg/kg CNO at time 1.5 hr. ii, Population data demonstrating timecourse of acutely administered CNO on gamma power and gamma power response to two injections of CNO administered 24 hours apart from one another. The timecourse of onset and offset of CNO effects, as measured by changes in gamma power, was measured during an acute administration of either 0.3 mg/kg (closed black squares; n=3 hM3Dq animals) or 0.5 mg/kg (open red circle; n=2 hM3Dq animals) CNO to determine dose-dependence of onset and offset kinetics. Twenty four hours following the acute administration of 0.3 mg/kg CNO (Day 1; closed black squares), a second injection of 0.3 mg/kg CNO was administered to the same animals and gamma power response was monitored (Day 2; open black circles) for the purpose of assessing desensitization of the hM3Dq receptor.

To assess the behavioral responses of hM3Dq mice to higher doses of CNO, we observed control and hM3Dq mice treated in parallel with saline or increasing doses of CNO. We found that treatment of hM3Dq mice with 0.5 mg/kg CNO reliably evoked limbic seizures of behavioral Class 1 (Figure 4Ci); no behavioral evidence of seizure activity was detected after administration of lower doses (0.03, 0.1, or 0.3 mg/kg CNO). Treatment with doses of CNO higher than 0.5 mg/kg evoked continuous seizure activity of classes three through seven, namely status epilepticus (SE) and death. CNO at doses of 1 or 5 mg/kg evoked SE in 2 of 4 animals and 5 of 7 animals (Figure 4Cii). Among the 5 animals in which SE was elicited by 5 mg/kg CNO, an orderly progression of behavioral seizure intensity was observed over time following CNO treatment (Figure 4Ciii). The latency to onset of the first Class 1 seizure was 15.4 ± 3.7 minutes. SE was lethal in 4 of the 7 animals during the 3 hr following SE onset. Whereas CNO reliably evoked seizures in hM3Dq animals, CNO evoked no behavioral seizures in control animals at any dose tested (0.03 – 5 mg/kg; n=4 carrying the tTA transgene alone; n=2 carrying the TRE-hM3Dq transgene alone; n=5 wild-type animals).

In Vivo Recordings from Hippocampus

We next sought to examine the electrophysiological correlates of the behavioral effects of CNO in the hM3Dq mice. Because the behavioral features of the seizures were typical for seizures arising from hippocampus and because hM3Dq is expressed in hippocampal neurons, we focused on the hippocampus. Towards this end, we implanted control and hM3Dq mice with multi-electrode arrays to monitor both local field potentials (LFPs) and spike activity of multiple individual neurons in the hippocampus. These in vivo recordings were performed during the same sessions as the behavioral seizure observations described above.

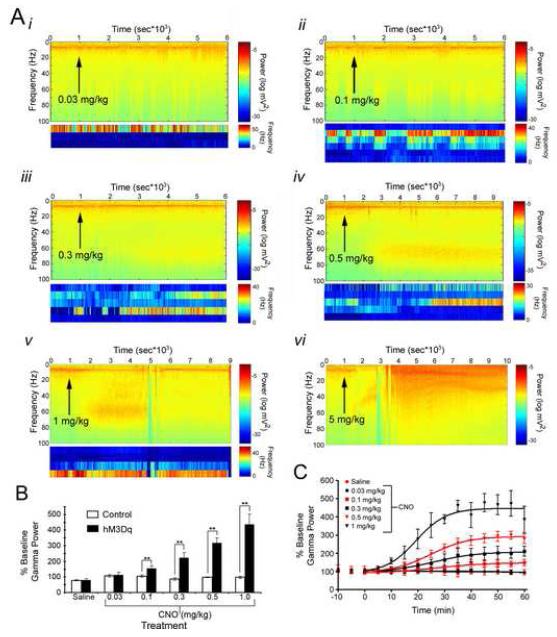

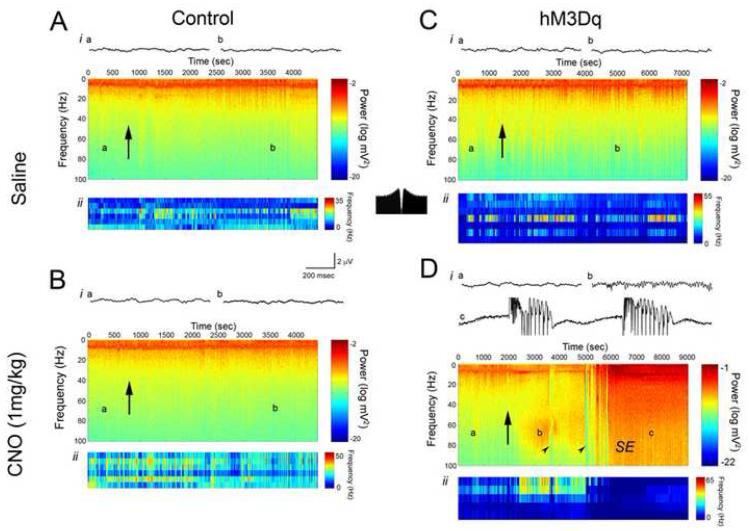

CNO increased neuronal activity in a dose- and time-dependent fashion as measured by both LFP and single unit firing rate (Figures 5-6). With respect to the dose-dependent change in neuronal activity, we found that treatment of hM3Dq mice with saline (Figure 6C) or 0.03 mg/kg (Figure 5Ai) CNO produced no significant change in the LFP or in single unit firing, consistent with the lack of behavioral affects of these doses. However, doses of 0.1 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg elicited successively greater increases in power of the gamma frequency band of the LFP (Figure 5B). At the sub-convulsive doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 0.3 mg/kg, increased power in the gamma frequency band was seen in the LFP, with 0.3 mg/kg eliciting a greater magnitude of gamma power increase (Figure 5Aii-iii,B). In addition, during the period of increased gamma power we found an increase in the firing rate of hippocampal interneurons (Figures 5-6). Treatment of hM3Dq mice with convulsant doses of CNO (0.5, 1 and 5 mg/kg) induced striking alterations in neuronal activity evident in both LFP and single unit activity (Figure 5Aiv-vi). Notably, spectral analyses of LFP activity revealed an increase in gamma power preceding the onset of seizures (Figure 5Avi, 6D). Analyses of single neuron firing frequency revealed an increase in interneuron firing frequency that coincided with the increased gamma power in the LFP. This pattern of single neuron firing persisted until the onset of seizures, at which point interneuron firing dramatically decreased (Figures 5-6). By contrast, treatment of hM3Dq mice with saline induced no significant change in LFPs or the firing frequency of interneurons (Figure 6C). Likewise, treatment of control mice with either CNO or saline induced no significant change in LFP spectral parameters or firing rate of interneurons (Figure 6A,B).

Figure 5. CNO dose-dependently increase neuronal activity and gamma power in hM3Dq mice.

A, CNO administration to hM3Dq mice evoked dose-dependent increases in hippocampal neuronal activity (i-vi), as seen by increased power in the gamma frequency band of the LFP and associated increased firing rate of presumed interneurons. Spectrograms show the power of all frequencies up to 100 Hz over the course of the recording session, with warmer colors representing greater power. Plots below spectrograms represent single unit firing rate of presumed interneurons, and each row corresponds to a single neuron. Here, warmer colors represent greater firing frequency. Classification of neurons as interneurons was based on firing frequency and pattern of firing. Arrows indicate the time at which CNO was administered s.c. at the dose indicated above each spectrogram. In A vi-vi, arrowheads indicate occurrence of isolated electrographic seizures, and SE represents onset of uninterrupted electrographic seizure activity. B, Peak power in the gamma frequency range measured from the LFP before and after administration of various doses of CNO displayed as percent of baseline gamma power (n=4 hM3Dq and 11 control animals). C, Timecourse of peak LFP gamma power change from baseline following administration of various doses of CNO. CNO was given at 0 minutes. ** represents p<0.01.

Figure 6. Local field potential and single unit recordings from hippocampus of control and hM3Dq animals administered either saline or 1 mg/kg CNO subcutaneously.

For each of A-D, i represent local field potential recordings. Spectrograms show the power of all frequencies up to 100 Hz over the course of the recording session, with warmer colors representing greater power. Letters on each spectrogram correspond to the example LFP epochs shown above each spectrogram. Arrows represent the time at which either saline or CNO was administered. ii in each of A-D show the firing frequency of individual putative interneurons recorded in hippocampus. Here, warmer colors represent greater firing frequency. Classification of neurons as interneurons was based on firing frequency and pattern of firing. As shown in the inset autocorrelogram between A and D, interneurons tended to fire tonically, as previously described (Henze et al., 2002). In Di, CNO (5 m/kg) elicited increased power in the gamma frequency range (b) before the onset of seizures (c). Arrowheads in D indicate occurrence of isolated electrographic seizures, and SE represents onset of uninterrupted electrographic seizure activity.

We also assessed the time-dependent changes in neuronal activity following CNO administration. The effect of CNO on the LFP, as measured by changes in gamma power, was first seen between 5 and 10 minutes after CNO administration and peaked between 45 and 50 minutes for all doses tested (Figure 5C). To determine the duration of CNO effects on neuronal activity, we administered CNO (0.3 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg) and recorded LFP for 24 hours (n=3 mice for 0.3 mg/kg; n=2 mice for 0.5 mg/kg). At both doses tested, the CNO-induced increase in gamma power persisted for approximately 9 hr (Figure 7B), paralleling the pattern we observed in locomotor activity (Figure 7A). These data suggest that the offset kinetics are not dependent on CNO dose. Moreover, 24 hours after the first 0.3 mg/kg dose, we readministered CNO (0.3 mg/kg) to the same mice and found no significant difference in peak gamma power response or duration of this response between day 1 and day 2, indicating that sensitivity to CNO, at least with 24 hours between administrations, was unaltered by such long-lasting effects (Figure 7Bii).

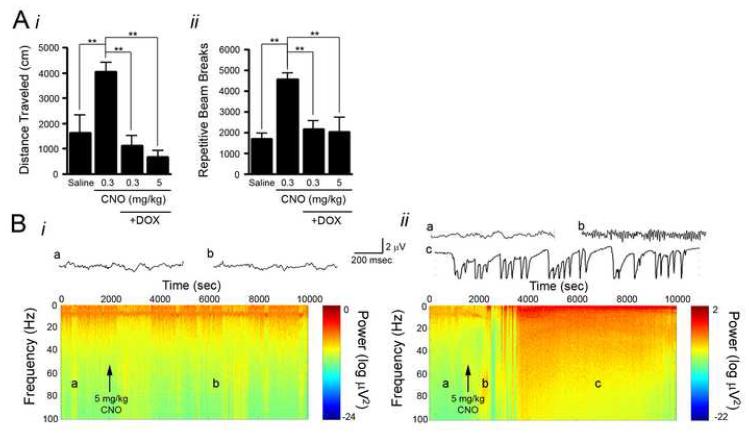

Efficiency of Tet-Off System in hM3Dq Mice

As described above, doxycycline virtually eliminated hM3Dq protein expression as assessed by radioligand binding assays, Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence microscopy. To assess whether doxycycline also eliminates the behavioral and electrophysiological responses to CNO, hM3Dq mice were treated with doxycycline for 4 weeks and behavioral and electrophysiological responses to CNO were assessed (n=5 hM3Dq; n=5 control). CNO (0.3 and 5 mg/kg) induced no locomotor response with respect to either total distance traveled (Figure 8Ai) or repetitive beam breaks (Figure 8Aii) in hM3Dq mice treated with doxycycline (n=5 mice). Moreover, behavioral seizures and alterations in LFP, as measured by spectral analysis, were notably absent from hM3Dq mice administered CNO (5 mg/kg) during doxycycline treatment (Figure 8Bi; n=3 mice). To assess the reversibility of doxycycline suppression of transgene expression on the electrophysiological response, administration of doxycycline was terminated and four weeks later the same mice were treated again with CNO (5 mg/kg) (Figure 8Bii). In this case, CNO induced increased power in the gamma frequency band as detected by LFP recordings as well as behavioral seizures culminating in SE and death, thereby demonstrating both the reversibility of doxycycline suppression of transgene expression and the specificity of CNO’s effects for the hM3Dq receptor.

Figure 8. Doxycycline treatment of hM3Dq animals prevents CNO induced behavioral and electrophysiological changes.

A, CNO administration to hM3Dq animals not exposed to doxycycline produced increased locomotor activity as measured by total distance traveled (i) and repetitive beam breaks (ii). However, four weeks of doxycycline exposure inhibited CNO-induced changes in locomotor activity (n=5 hM3Dq mice). Bi, Four weeks of doxycycline exposure inhibited CNO (5 mg/kg) induced changes in the LFP. No increase in gamma power was elicited and no seizures resulted from CNO administration. Bii, Following 4 weeks of doxycycline exposure, animals were taken off doxycycline for 4 weeks and challenged with CNO (5 mg/kg) again. At this time, CNO elicited increased power in the gamma frequency range (b) and subsequent SE (c).

DISCUSSION

Here, we report a novel chemical-genetic approach for the experimental manipulation of CNS neuronal activity. We paired a tetracycline-repressible tissue-specific genetic system, which provided transgenic mice with inducible, reversible, and spatially controlled transgene expression, with a specific and selective pharmacologic system (e.g. second-generation DREADD-type RASSLs) to achieve remote spatial control over neuronal activity in vivo. In coupling these two systems, we demonstrated controlled activation of Gq-coupled pathways, resulting in striking behavioral and electrophysiological changes. Many systems are now available for controlling neuronal activity, each with its particular advantages and disadvantages. The technique we describe here provides an additional tool with some important advantages over existing approaches.

Utility of the DREADD system for in vivo applications

Several features of second-generation RASSLs tailor them for in vivo use, as exemplified by the hM3Dq mouse in this study. First, neuronal activation in hM3Dq animals is highly selective; CNO has no detectable off-target actions. Using multiple readouts including animal activity, in vitro slice recordings, and in vivo multi-electrode array recordings, we detected no effect of CNO in wild-type, single-transgenic, or doxycycline-treated double-transgenic animals. In this respect, our approach is an improvement upon its RASSL predecessors, as the small molecule agonists of first-generation RASSLs are pharmacologically active and necessitate a knockout background (Scearce-Levie et al., 2001). Together with a tissue- or even cell-specific genetic or viral system, these second-generation RASSLs thus allow one to target specific cell types or networks without interference from undesired ligand actions.

Second, our approach enables non-invasive modulation of neuronal activity. CNO, like other RASSL ligands, can be injected peripherally (or provided through drinking water; unpublished observations) and crosses the blood-brain barrier to activate receptors in discrete and even widely distributed cell populations. In contrast, other systems for neuronal manipulation (e.g. microbial opsins and optoXRs, AlstR, the ligand-gated ion channel TRPV1 [Arenkiel et al., 2008]) require direct application of light/ligand to brain tissue in order to alter neuronal activity and thus have spatial limitations with regard to cells that can be activated at a given time. Although the invasive procedures mandated by those systems are not a hindrance for all applications, remote control of neuronal activity could be beneficial in some instances, in particular for readouts such as animal behavioral tasks, which are exquisitely sensitive to handling stress, or for the activation of diffusely distributed populations of cells. Moreover, because neurons can be activated non-invasively in hM3Dq animals, this technology is more readily accessible than optical approaches or the AlstR and TRPV1 systems. Once mice with the desired pattern of receptor expression have been generated, the receptor can easily be activated by peripheral injection; stereotaxic apparatus, light sources, fiberoptics, and the technological expertise they require are thus unneccesary.

Third, hM3Dq activation is dose-dependent, allowing one to titrate the level of receptor activity by varying the dose of CNO. In the absence of CNO, we were able to detect only a single difference in hM3Dq mice compared to controls, despite extensive observations and behavioral testing. Whether the mutant receptor lacks constitutive activity, whether the concentration of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft is insufficient to activate hM3Dq given its reduced potency at the mutant receptor, or whether the lack of phenotype represents homeostatic neuronal equilibration is unclear. However in vitro evidence (Armbruster et al., 2007) together with the fact that mice expressing hM3Dq in pancreatic β-cells exhibit no detectable phenotype in the absence of CNO (Guettier et al., submitted) suggests that neuronally expressed hM3Dq exhibits little constitutive activity and is insensitive to endogenous acetycholine.

In response to CNO administration, we describe both behavioral changes following low doses of CNO (0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) and mild to severe seizures and status epilepticus resulting from higher doses of CNO (0.5, 1.0, 5.0 mg/kg). Moreover, dose-dependent LFP alterations are present at all doses from 0.1 to 5.0 mg/kg. In this case, the high levels of hM3Dq overexpression may increase the dynamic range of the system. In the absence of CNO, the system is apparently silent. At low doses of CNO, occupancy of a small proportion of hM3Dq results in subtle phenotypes; by contrast, occupancy of higher proportions of hM3Dq with higher doses of CNO yields more profound effects. This characteristic of the second-generation RASSLs increases their applicability to experimental manipulations as it provides the user considerable control over the extent of receptor activation. By contrast, when expressed in certain tissues, the first generation of RASSLs occasionally signals at high levels in the unstimulated state and results in significant pathologies (Redfern et al., 2000; Sweger et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2008; Hsiao et al., 2008), thereby preventing one from precisely titrating the level of receptor activity by exogenous ligand application.

Together, these aspects of the approach described here — its selectivity, non-invasiveness, and dynamic range, as well as the spatiotemporal control over receptor expression that mouse genetics affords — render this technique attractive for in vivo manipulations of neuronal signaling. Additionally, although we report here only the ability of the Gq-coupled DREADD to activate neuronal firing via PLC-dependent pathways, Gi- and Gs-coupled DREADDs permit the manipulation of other GPCR signaling cascades to effect alternative endpoints (Ferguson and Neumaier, unpublished observations; Guettier et al., submitted). Thus, the DREADD system is well-suited for investigating diverse experimental questions. While drawbacks persist, this system is nonetheless an improved and valuable tool for analysis of how the activity of discrete populations of neurons and local circuits underlies behavior.

Molecular and cellular etiology of the hM3Dq mouse phenotype

For this proof-of-concept study of hM3Dq function in vivo, we employed the CaMKIIα-tTA Tet-Off system to drive expression of a Gq-coupled GPCR in forebrain principal neurons. In addition to validating our technique for selective neuronal activation, this system allowed us to investigate Gq signaling cascades — both the molecular mediators of signal transduction and the pathology stemming from its over-activation — in this neuronal subpopulation.

Using the in vitro slice preparation, we demonstrated that CNO directly depolarizes pyramidal cells from hM3Dq mice and does so in an apparently PLC-dependent manner; the active PLC inhibitor U73122, but not its inactive analog U73343, blocked the depolarizing effect of CNO. The observed PLC dependence of CNO’s effects on hM3Dq neurons is expected based on previous characterization of the specificity with which hM3Dq couples to Gq (Armbruster et al., 2007). The magnitude and kinetics of the CNO-induced depolarization and its PLC dependence suggests that one mechanism by which CNO may depolarize neurons is through inhibition of M-current, a slowly inactivating, outwardly rectifying potassium current important for depression of neuronal excitability (Brown and Yu, 2000). M-current is carried by PIP2-gated KCNQ channels (Wang et al., 1998; Zhang et al, 2003; Biervert et al, 1998). Importantly, humans with benign familial neonatal convulsions, an autosomal dominant form of neonatal epilepsy, carry an insertion in their KCNQ2 gene which yields a non-functional protein (Biervert et al, 1998). Activation of PLCβ by numerous Gq-coupled GPCRs causes PIP2 hydrolysis, which reduces PIP2 content, closes KCNQ channels, and inhibits M-current, resulting in neuronal depolarization and a propensity for neurons to fire bursts rather than tonic spikes (Zhang et al, 2003). While the closing of KCNQ channels is an appealing hypothesis for the molecular mechanism of hM3Dq action, further in vitro studies employing specific KCNQ channel blockers will be necessary to demonstrate its validity.

Given our hypothesis that neuronal depolarization occurs at least in part through inhibition of M-current in hM3Dq-expressing neurons, it is unknown to what extent hM3Dq signaling might differ in other cell types or brain regions that do not express KCNQ channels (e.g. cerebellum; Wang et al., 1998). Examining the diverse consequences of activating the same molecular signaling pathway in different cell types is an attractive application of the DREADD system and provides just one example of the many uses for this technology.

Our in vivo electrophysiology studies provide insights into the mechanism of CNO’s actions at the cellular and systems level in hM3Dq mice. We found that CNO evoked dose-dependent increases in gamma power as detected by spectral analyses of LFP recordings from hippocampus, selectively in hM3Dq mice. This increased gamma power was associated with an increase in hippocampal interneuron firing rate. We propose that hM3Dq activation modifies local hippocampal circuit activity by activating principal cells, which synaptically activate interneuron firing, thereby producing gamma oscillations. This hypothesis is based on three lines of evidence. First, the pattern of hM3Dq expression, coupled with the in vitro data described above, suggests that CNO’s direct effects are restricted to principal excitatory neurons. hM3Dq expression is driven by the principal neuron-specific CaMKIIα promoter (Hanson and Schulman, 1992), and HA immunoreactivity, representing hM3Dq expression, is absent from the parvalbumin-positive interneuron cell bodies (Figure S8) shown to contribute to the gamma rhythm (Bartos et al., 2007; Cardin et al., 2009). Second, our findings of persistently increased gamma power are consistent with previously described pharmacological models of gamma induction. For example, bath application of the muscarinic agonist carbachol to hippocampal slices in vitro is sufficient to induce gamma frequency field potentials that persist long after the drug has washed from the bath (Fisahn et al., 1998). Third, the proposed mechanism by which the gamma rhythm is induced in the carbachol model of gamma oscillations includes excitation of pyramidal cells, leading to persistent synchronous firing of a circuit of interneurons connected by gap junctions. As described above, our in vitro whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal cells revealed that CNO directly depolarizes pyramidal cells, and our in vivo hippocampal recordings revealed that CNO produces increased interneuron firing rate. Thus we conclude that the increased gamma rhythm and behavioral consequences of CNO administration to hM3Dq mice are the result of hM3Dq directly activating excitatory pyramidal neurons that subsequently induce synchronous interneuron firing. We further conclude that the CNO-evoked seizures are triggered by activation of excitatory pyramidal neurons, but the precise cellular events mediating the transition from increased gamma rhythm into seizure activity remain to be elucidated.

Potential limitations of DREADD technology

While the second generation RASSLs (DREADDs) described here overcome some of the previous problems plaguing experimental manipulation of neuronal signaling, we acknowledge potential limitations of this system.

The primary disadvantage of the DREADD system in general, and these hM3Dq mice in particular, is the relatively coarse temporal resolution of neuronal manipulation. We have thoroughly characterized the kinetics of activation of hM3Dq and the ensuing electrophysiological response and shown activation to begin between 5 and 10 minutes after injection, with peak electrophysiological responses occurring 45 to 50 minutes after injection. We determined that both the behavioral and electrophysiological effects of CNO in hM3Dq mice are persistent, with responses not returning to baseline for many hours. Both the onset and offset kinetics were unrelated to the dose of CNO. While the kinetics of onset of the CNO response are likely similar to that of other systemically administered drugs, including other RASSL ligands, they are certainly slower than that of locally infused ligands such as allatostatin (for AlstR) or capsaicin (for TRPV1) which occur on the order of minutes, or the microbial opsins, whose activation occurs on the order of milliseconds. The latency to onset of CNO’s effects is likely due to the pharmacokinetic properties of CNO. In contrast, the duration of CNO’s effects could be specific to the neuronal population in which hMDq is expressed and the signaling events the receptor mediates; hM3Dq expression in other tissues might not elicit such persistent effects. Thus, while CNO allows for noninvasive control of activity in select populations of CNS neurons in a freely moving adult mouse, the temporal resolution of that control is coarse, particularly in comparison to microbial opsins.

The kinetics of inactivation of hM3Dq signaling in vivo might prove to be a greater limitation of this technology than those of activation. As shown by both locomotor and electrophysiological activity, the response to sub-seizure doses of CNO is long-lasting, with responses returning to baseline approximately 9 hours of injection. Clearly, for applications requiring defined termination points, these hM3Dq mice are not well suited. While the enduring responses may represent continual hM3Dq activation by CNO, three facts lead us to favor the idea that they are due to regenerative downstream events within hM3Dq expressing neurons and/or to activation of other neuronal populations. First, carbachol-induced gamma rhythm in hippocampal slices persists following removal of carbachol from the bath (Fisahn et al., 1998), demonstrating that fleeting activation of muscarinic receptors can induce persistent responses. Second, CNO is removed from plasma within 2 hours of injection, without back-metabolism to clozapine (Guettier et al., submitted), arguing against persistent CNO-mediated activation of hM3Dq. Third, the time course of CNO-evoked physiological effects in transgenic mice expressing hM3Dq in pancreatic β-cells correlates with the plasma concentration of CNO, with effects diminishing within 2 hours (Guettier et al., submitted). It will be important for future users of DREADD technology to fully characterize the timing of offset of effects in each cell population. Additionally, such long-lasting augmentation of neuronal activity could have effects on receptor sensitivity and trafficking or on synaptic plasticity. Indeed, this hM3Dq mouse provides an attractive system for the study of synaptic changes stemming from long-term activation of hippocampal neuronal networks.

A final note of consideration regarding first- and second-generation RASSL, optoXR, and AlstR approaches is that the mechanisms of neuronal modulation are indirect and dependent on intracellular effectors. Here, in hM3Dq mice, neuronal activation is secondary to coupling to PLCβ, and the molecular mechanism by which PLCβ increases neuronal activity is incompletely understood at this time. In contrast to systems that couple directly to an ion channel with no intermediaries (e.g. channelrhodopsin and TRPV1), it remains possible that if a given population of neurons lacks the required molecular mediators downstream of PLCβ, these neurons may not respond to CNO, or may do so by a different mechanism than that which we have hypothesized is occurring here.

To conclude, in this study we describe the validation and utility of the chemical-genetic DREADD approach, wherein a peripherally administered, pharmacologically inert drug-like small molecule (CNO) selectively modulates neuronal activity through an evolved Gq-coupled GPCR. We have previously described the in vitro use of a silencing Gi-coupled DREADD (hM4Di; Armbruster et al., 2007; Nawaratne et al., 2008), and a Gs-coupled DREADD has also recently been developed (Conklin et al, 2008; Guettier et al., submitted). Collectively, these reagents provide useful tools for activating and silencing neurons and for modulating distinct GPCR-coupled signaling pathways in vivo.

Methods

Behavioral and biochemical experiments were performed at the University of North Carolina and Case Western Reserve University, and all electrophysiology experiments were performed at Duke University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for the care and use of animals and with approved animal protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the aforementioned institutions. Detailed protocols for all methods are described in Supplemental Methods.

Generation of TRE-hM3Dq Mice

In brief, an HA epitope tag and the hM3Dq sequence were cloned into the plasmid pTre-Tight. The plasmid was then digested to generate TRE-HA-hM3Dq DNA, and pronuclear injection of B6SJL hybrid mouse oocytes using the 2.36 kb digestion product was performed by the Case Transgenic and Targeting Facility (Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH). Genotyping was performed by PCR of genomic DNA extracted from tail clips. Upon identification, founder TRE-HA-hM3Dq mice were crossed with CaMKIIα-tTA mice (The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, Maine; Mayford et al, 1996). Gene expression in double transgenic (hM3Dq) mice was maintained by raising mice on a doxycycline-free diet. Protein expression in mouse whole-brain homogenate was detected by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA-affinity matrix followed by Western detection. All immunohistochemistry and radioligand binding procedures used to characterize receptor expression are provided in Supplemental Methods.

In Vitro Electrophysiology

Acute hippocampal slices were isolated from hM3Dq mice and littermate controls (P18-P32), and whole-cell recordings were made CA1 pyramidal cells. CNO (500 nM — 1 μM) was bath applied and changes in membrane potential and spike activity were monitored.

Stereotypy and locomotion

Activity was assessed by sessions in an open field chamber crossed by a grid of photobeams (VersaMax system, AccuScan Instruments). An acclimation interval preceded each trial, following which mice were injected with either vehicle (saline) or CNO (Biomol International) in vehicle, i.p. and the trial initiated. Counts were taken of the number of photobeams broken during the trial in five-minute intervals, with separate measures for ambulation (total distance traveled) and fine movements (repetitive beam breaks). Data from the first 15 minutes following CNO administration were excluded from analyses in which data from multiple 5-minute intervals were pooled.

Seizure activity

Behavioral seizure classification was based on a modified description of Racine (Borges et al., 2003; Racine, 1972) with increasing seizure class representing increasing seizure severtiy.

In Vivo Electrophysiology

Multi-electrode arrays were implanted bilaterally into the hippocampi of hM3Dq and littermate control mice. Following a one-week recovery period, animals were administered either saline or varying doses of CNO (0.03 – 5 mg/kg) while monitoring hippocampal LFP and single unit firing of presumed hippocampal interneurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following awards from the National Institutes of Health: NS060326 from the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (GMA), GM07040-34 and GM008719 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (SCR), GM007250 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AIA), GM074554 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (BNA), HD040127 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (JAA), HD03110 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RJN, SSM), NS049534 from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (MAN), NS056217 from the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (JOM), MH082441-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health (BLR) The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health. This work is also supported by a NARSAD Distinguished Investigator Award (BLR).

Non-standard abbreviations

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AlstR

Drosophilia allatostatin receptor

- CNO

clozapine-n-oxide

- DG

Dentate gyrus

- DREADD

designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HA

hemagglutinin

- hM3Dq

Gq-coupled human M3 muscarinic DREADD

- hPASMC

human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

- LFP

local field potential

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

- PLC

Phospholipase C

- RASSLs

receptors activated solely by synthetic ligands

- rRMDs

Gs-coupled rat RASSL muscarinic DREADD

- SE

status epilepticus

- TRE

tet response element

- tTA

tet transactivator

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Airan RD, Thompson KR, Fenno LE, Bernstein H, Deisseroth K. Temporally precise in vivo control of intracellular signalling. Nature. 2009;458:1025–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature07926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenkiel BR, Klein ME, Davison IG, Katz LC, Ehlers MD. Genetic control of neuronal activity in mice conditionally expressing TRPV1. Nat Methods. 2008;5:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender D, Holschbach M, Stocklin G. Synthesis of n.c.a. carbon-11 labelled clozapine and its major metabolite clozapine-N-oxide and comparison of their biodistribution in mice. Nucl Med Biol. 1994;21:921–925. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A, Yizhar O, Gunaydin LA, Hegemann P, Deisseroth K. Bi-stable neural state switches. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:229–234. doi: 10.1038/nn.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biervert C, Schroeder BC, Kubisch C, Berkovic SF, Propping P, Jentsch TJ, Steinlein OK. A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science. 1998;279:403–406. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges K, Gearing M, McDermott DL, Smith AB, Almonte AG, Wainer BH, Dingledine R. Neuronal and glial pathological changes during epileptogenesis in the mouse pilocarpine model. Exp Neurol. 2003;182:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, Yu SP. Modulation and genetic identification of the M channel. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;73:135–166. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Carlen M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tsai LH, Moore CI. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin BR, Hsiao EC, Claeysen S, Dumuis A, Srinivasan S, Forsayeth JR, Guettier JM, Chang WC, Pei Y, McCarthy KD, et al. Engineering GPCR signaling pathways with RASSLs. Nat Methods. 2008;5:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisahn A, Pike FG, Buhl EH, Paulsen O. Cholinergic induction of network oscillations at 40 Hz in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature. 1998;394:186–189. doi: 10.1038/28179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:559–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze DA, Wittner L, Buzsaki G. Single granule cells reliably discharge targets in the hippocampal CA3 network in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:790–795. doi: 10.1038/nn887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao EC, Boudignon BM, Chang WC, Bencsik M, Peng J, Nguyen TD, Manalac C, Halloran BP, Conklin BR, Nissenson RA. Osteoblast expression of an engineered Gs-coupled receptor dramatically increases bone mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1209–1214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707457105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner HA, Lein ES, Callaway EM. A genetic method for selective and quickly reversible silencing of Mammalian neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5287–5290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05287.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Gutierrez DV, Hanson MG, Han J, Mark MD, Chiel H, Hegemann P, Landmesser LT, Herlitze S. Fast noninvasive activation and inhibition of neural and network activity by vertebrate rhodopsin and green algae channelrhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17816–17821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K. Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron. 2008;57:634–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayford M, Bach ME, Huang YY, Wang L, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Control of memory formation through regulated expression of a CaMKII transgene. Science. 1996;274:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Ligand: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaratne V, Leach K, Suratman N, Loiacono RE, Felder CC, Armbruster BN, Roth BL, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. New insights into the function of M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors gained using a novel allosteric modulator and a DREADD (designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug) Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1119–1131. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y, Rogan SC, Yan F, Roth BL. Engineered GPCRs as tools to modulate signal transduction. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:313–321. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Jasper HH. Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain. 1st Ed Little Brown; Boston: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Bencsik M, Louie A, Lu W, Millard S, Nguyen P, Burghardt A, Majumdar S, Wronski TJ, Halloran B, et al. Conditional expression of a Gi-coupled receptor in osteoblasts results in trabecular osteopenia. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1329–1337. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern CH, Coward P, Degtyarev MY, Lee EK, Kwa AT, Hennighausen L, Bujard H, Fishman GI, Conklin BR. Conditional expression and signaling of a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:165–169. doi: 10.1038/6165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern CH, Degtyarev MY, Kwa AT, Salomonis N, Cotte N, Nanevicz T, Fidelman N, Desai K, Vranizan K, Lee EK, et al. Conditional expression of a Gi-coupled receptor causes ventricular conduction delay and a lethal cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4826–4831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scearce-Levie K, Coward P, Redfern CH, Conklin BR. Engineering receptors activated solely by synthetic ligands (RASSLs) Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:414–420. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweger EJ, Casper KB, Scearce-Levie K, Conklin BR, McCarthy KD. Development of hydrocephalus in mice expressing the G(i)-coupled GPCR Ro1 RASSL receptor in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2309–2317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4565-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EM, Yamaguchi Y, Horwitz GD, Gosgnach S, Lein ES, Goulding M, Albright TD, Callaway EM. Selective and quickly reversible inactivation of mammalian neurons in vivo using the Drosophila allatostatin receptor. Neuron. 2006;51:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Prigge M, Beyriere F, Tsunoda SP, Mattis J, Yizhar O, Hegemann P, Deisseroth K. Red-shifted optogenetic excitation: a tool for fast neural control derived from Volvox carteri. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:631–633. doi: 10.1038/nn.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wang LP, Brauner M, Liewald JF, Kay K, Watzke N, Wood PG, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Gottschalk A, Deisseroth K. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothetis DE. PIP(2) activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell. 2003;115:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.