Abstract

Plant basal resistance is activated by virulent pathogens in susceptible host plants. A Colletotrichum orbiculare fungal mutant defective in the SSD1 gene, which regulates cell wall composition, is restricted by host basal resistance responses. Here, we identified the Nicotiana benthamiana signaling pathway involved in basal resistance by silencing the defense-related genes required for restricting the growth of the C. orbiculare mutant. Only silencing of MAP Kinase Kinase2 or of both Salicylic Acid Induced Protein Kinase (SIPK) and Wound Induced Protein Kinase (WIPK), two mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, allowed the mutant to infect and produce necrotic lesions similar to those of the wild type on inoculated leaves. The fungal mutant penetrated host cells to produce infection hyphae at a higher frequency in SIPK WIPK-silenced plants than in nonsilenced plants, without inducing host cellular defense responses. Immunocomplex kinase assays revealed that SIPK and WIPK were more active in leaves inoculated with mutant fungus than with the wild type, suggesting that induced resistance correlates with MAP kinase activity. Infiltration of heat-inactivated mutant conidia induced both SIPK and WIPK more strongly than did those of the wild type, while conidial exudates of the wild type did not suppress MAP kinase induction by mutant conidia. Therefore, activation of a specific MAP kinase pathway by fungal cell surface components determines the effective level of basal plant resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Plants have evolved multiple strategies to defend themselves against infection by microbial pathogens. Plant disease resistance has been studied most thoroughly in cases that depend on the presence of specific resistance genes (R genes) that confer immunity to particular races of pathogens carrying a cognate avirulence gene (Laugé and De Wit, 1998; Dangl and Jones, 2001; Chisholm et al., 2006). In addition to R gene–mediated resistance, which conditions race cultivar specificity, plants also possess basal or general resistance that confers durable protection against many potential microbial pathogens (Jones and Takemoto, 2004). This type of resistance requires that plants are able to recognize a broad spectrum of microbes, and the currently accepted view is that plants have evolved pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity to recognize features that are common to many microbes via cell surface receptors (Thordal-Christensen, 2003; Nürnberger et al., 2004). Several PAMPs have been identified from plant pathogens, including flagellin and elongation factor Tu from Gram-negative bacteria (Felix et al., 1999; Kunze et al., 2004) as well as chitin and β-glucan from fungi and oomycetes (Umemoto et al., 1997; Kaku et al., 2006). Although PAMPs may trigger immune responses in susceptible plants, it is considered that adapted pathogens have evolved to overcome or evade basal resistance so that these responses are no longer sufficient to completely restrict pathogen infection (Jones and Dangl, 2006; de Wit, 2007). However, host basal resistance to fungal pathogens is still poorly understood, and so far PAMP-related fungal mutants have not been exploited for studying the molecular basis of PAMP-triggered immunity in vivo.

Colletotrichum orbiculare (syn. Colletotrichum lagenarium) is an ascomycete fungus causing anthracnose disease in cucumber (Cucumis sativus). This fungus develops a specialized infection structure called an appressorium that effects direct penetration into host epidermal cells by breaching the plant cuticle and cell wall layers through a combination of mechanical force and localized enzymatic dissolution (Perfect et al., 1999; Tucker and Talbot, 2001). Therefore, successful appressorial penetration is an essential first step in the infection process of C. orbiculare. In a previous forward genetic screen for pathogenicity mutants, we identified the SSD1 gene of C. orbiculare (Tanaka et al., 2007). This gene is a functional ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SSD1, a putative regulator of fungal cell wall composition (Wheeler et al., 2003). Appressorial penetration by ssd1 disruption mutants is restricted by the deposition of callose papillae by host cells at sites of attempted penetration, resulting in strongly attenuated pathogenicity on host plants, although the mutants retained wild-type penetration ability on artificial substrata. The induction of host papilla formation by ssd1 mutants was faster and more frequent than by the wild type and was associated with the complete inhibition of infection. Manipulation of host physiology confirmed that the impaired penetration ability of the ssd1 mutants resulted from their induction of host basal resistance responses (Tanaka et al., 2007). Based on these findings, we concluded that host basal resistance can completely block infection by an adapted pathogen when induced to a sufficiently high level.

In this study, we attempted to dissect the molecular basis of plant basal resistance using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in Nicotiana benthamiana to compromise resistance to the C. orbiculare ssd1 mutant. Together with evidence from immunocomplex kinase assays, we show that the success or failure of infection by C. orbiculare may be determined by the level of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activity induced in host plants.

RESULTS

SSD1 Is Required for Fungal Pathogenicity on N. benthamiana

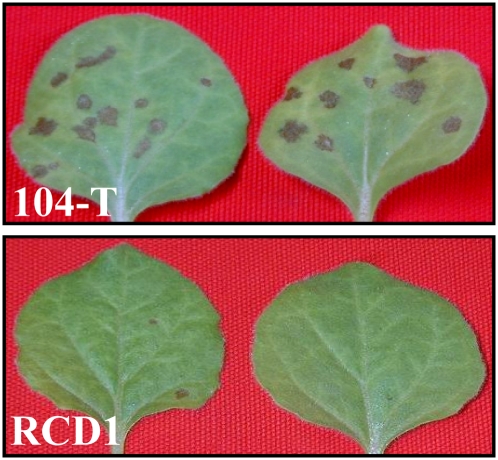

The SSD1 gene of C. orbiculare is essential for successful penetration by appressoria into epidermal cells of susceptible cucumber plants, and the failed penetration attempts by ssd1 mutants were associated with deposition of callose papillae by host cells (Tanaka et al., 2007). N. benthamiana is also a susceptible host plant for C. orbiculare (Shen et al., 2001). First, we examined whether the SSD1 gene is essential for infection of N. benthamiana. When conidial suspensions of the wild-type strain 104-T were inoculated onto leaves, typical necrotic lesions could be observed 5 d after inoculation (DAI). By contrast, leaves inoculated with the ssd1 mutant RCD1 did not show visible disease symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathogenicity of the C. orbiculare ssd1 Mutant on N. benthamiana.

Pathogenicity test of C. orbiculare wild-type strain 104-T and ssd1 mutant RCD1. Conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) was sprayed onto the upper leaves of 3-week-old plants. Leaves inoculated with 104-T showed obvious necrotic lesions at 5 DAI, but those inoculated with RCD1 did not.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

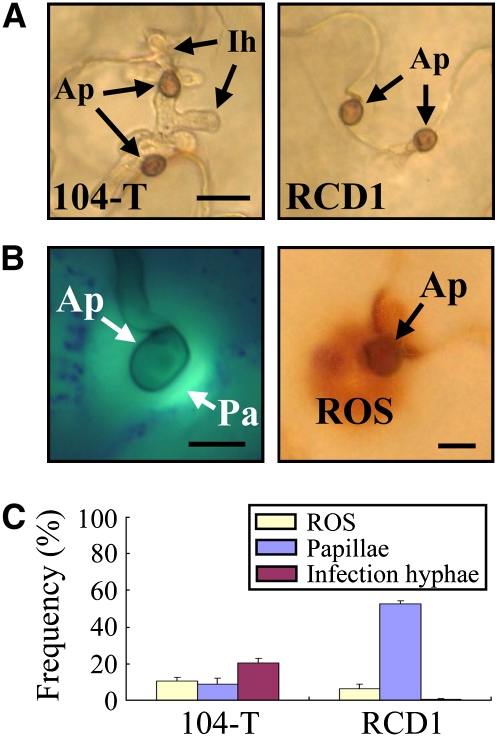

Microscopy analysis showed that the ssd1 mutant formed appressoria that were indistinguishable from those of the wild-type strain 104-T on the N. benthamiana (Figure 2A). However, the formation of intracellular infection hyphae in plant epidermal cells by RCD1 was not observed, in contrast with 104-T (Figure 2A). To observe the responses of N. benthamiana cells to attempted penetration by appressoria of the mutant, inoculated leaves were stained with aniline blue to detect callose papillae by epifluorescence microscopy (Figure 2B). At attempted penetration sites of the ssd1 mutant, ∼50% of appressoria were accompanied by callose papillae, and intracellular infection hyphae were rarely observed inside host cells (Figure 2C). By contrast, the frequency of papilla formation under appressoria of 104-T was only 10%, and infection hyphae were seen in <20% of appressoria. When inoculated leaves were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) to detect accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), positive staining was rarely detected under appressoria (Figure 2B), and the frequency of staining was ∼10% in both 104-T and RCD1 (Figure 2C). These responses of N. benthamiana to challenge by the ssd1 mutant were similar to those of C. sativus (Tanaka et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Infection Phenotypes of C. orbiculare ssd1 Mutant and Defense Responses on N. benthamiana.

(A) Cytology of appressorial penetration by the wild-type 104-T and ssd1 mutant RCD1. The upper leaves were droplet-inoculated with conidial suspension (5 × 105 conidia/mL) and observed at 72 HAI. Ap, appressorium; Ih, intracellular infection hyphae. Bar = 10 μm.

(B) Left panel: Callose papilla (Pa) formed under appressoria (Ap). The leaf was inoculated with 104-T, stained with aniline blue, and observed with epifluorescence microscopy at 72 HAI. Callose was detectable by its green fluorescence. Bar = 5 μm. Right panel: ROS accumulation under appressoria. The leaf inoculated with 104-T was stained with DAB and observed with light microscopy at 72 HAI. ROS was detectable as dark-brown staining. Bar = 5 μm.

(C) Quantification of papilla formation and ROS accumulation at sites of attempted penetration by C. orbiculare appressoria. At 72 HAI, leaves inoculated with the wild-type 104-T and ssd1 mutant RCD1 were stained with aniline blue to detect callose or with DAB to detect ROS accumulation. At least 200 appressoria were counted for each fungal strain, and standard errors were calculated from three replicate experiments.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

The Impaired Pathogenicity of the ssd1 Mutant Depends on MEK2-SIPK/WIPK–Mediated Basal Resistance

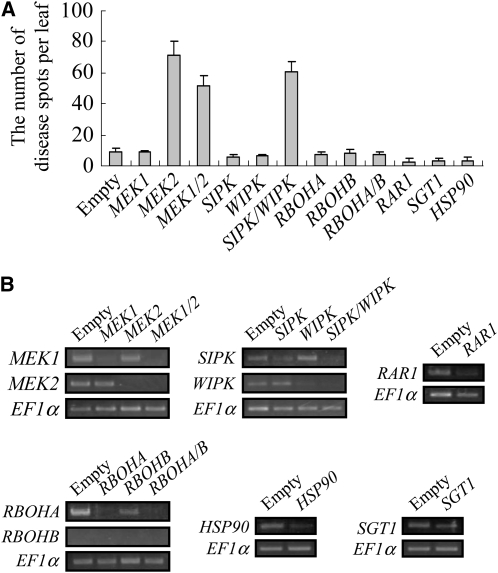

To identify the plant defense signaling pathway involved in restricting infection by the ssd1 mutant, we applied VIGS in N. benthamiana. We generated knockdown plants of known defense-related genes, such as MAP kinase kinases (MEK1 and MEK2), MAP kinases (Salicylic Acid Induced Protein Kinase [SIPK] and Wound Induced Protein Kinase [WIPK]), genes involved in ROS production (Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog [RBOHA and RBOHB]), and R gene–mediated resistance (Required for MLa12 Resistance [RAR1], Suppressor of G2 Allele of SKP1 [SGT1], and Heat Shock Protein 90 [HSP90]), and inoculated these silenced plants with the ssd1 mutant, RCD1. At 5 DAI, the number of disease lesions on inoculated leaves was counted (Figure 3A). MEK2-silenced, MEK1 MEK2–silenced, and SIPK WIPK–silenced plants showed 60 to 70 lesions per leaf, whereas control plants (empty vector) showed 10 or less lesions. By contrast, the number of lesions formed on plants in which MEK1, RBOHA, RBOHB, RAR, SGT1, or HSP90 had been silenced was similar to that of control plants. Interestingly, plants silenced at either SIPK or WIPK also did not show significant disease symptoms. When the effect of VIGS was evaluated by RT-PCR, the expression of all target genes appeared to be downregulated, although some variation in the level of silencing between different genes was detected (Figure 3B). We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that plants in which gene silencing produced no enhanced disease phenotype still retained sufficient transcript levels to mount effective defense responses.

Figure 3.

Effect of Silencing Plant Defense-Related Genes on Pathogenicity of the ssd1 Mutant.

(A) Lesion formation on gene-silenced plants inoculated with the ssd1 mutant, RCD1. Conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) was sprayed onto the upper leaves of plants in which the following genes were silenced: MEK1, MEK2, MEK1 and MEK2 (MEK1/2), SIPK, WIPK, SIPK and WIPK (SIPK/WIPK), RBOHA, RBOHB, RBOHA and RBOHB (RBOHA/B), RAR1, SGT1, and HSP90. Lesions were counted at 5 DAI, and results are based on three replicate experiments.

(B) RT-PCR evaluation of gene silencing. Total RNAs were extracted from the leaves used for the pathogenicity tests shown in (A), and the effect of VIGS was evaluated by RT-PCR. PCR was performed with 35 cycles of amplification and evaluated by three biological replicates

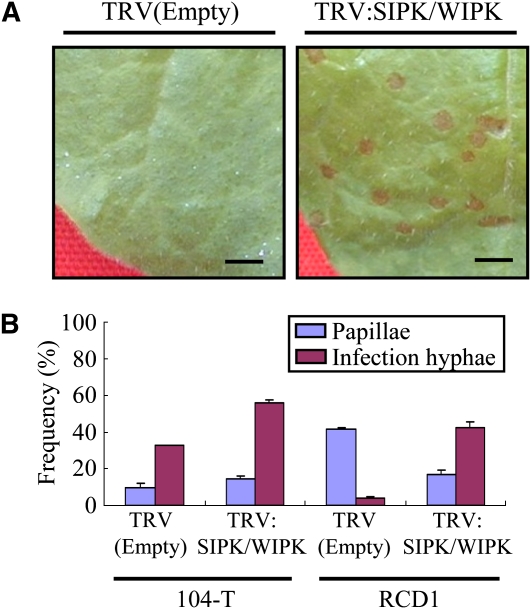

The necrotic lesions formed by the ssd1 mutant in SIPK WIPK–silenced plants were similar in appearance to those formed by the wild-type 104-T (Figures 1 and 4A). Light microscopy showed that the infection process of the ssd1 mutant on SIPK WIPK–silenced plants was also similar to that of 104-T, with typical appressoria and infection hyphae present at 72 h after inoculation (HAI). The frequency with which intracellular infection hyphae were produced by appressoria of the mutant was ∼40% in SIPK WIPK-silenced plants, whereas the frequency of papilla formation was reduced from ∼40 to 20% in SIPK WIPK–silenced plants (Figure 4B). In the case of the wild-type 104-T, appressorial penetration frequency was significantly increased, from 30% in nonsilenced control plants to ∼50% in SIPK WIPK-silenced plants (Figure 4B). Accordingly, the number of necrotic lesions produced by 104-T on SIPK WIPK–silenced plants was ∼1.5-fold higher than on control plants. Taken together, these findings indicate that a specific MAP kinase pathway is required for the plant resistance responses that restrict appressorial penetration by the ssd1 mutant.

Figure 4.

Infection Phenotype of the ssd1 Mutant in SIPK WIPK–Silenced Plants.

(A) Conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the ssd1 mutant RCD1 was sprayed onto leaves of control (empty vector) or SIPK- and WIPK-silenced plants. Typical anthracnose lesions were produced on leaves of SIPK- and WIPK-silenced plants, while lesions were absent from leaves of control plants at 5 DAI. Bar = 1 cm.

(B) Quantification of papilla and infection hypha formation at sites of attempted penetration by C. orbiculare appressoria. At 72 HAI, leaves inoculated with the wild-type 104-T and ssd1 mutant RCD1 were stained with aniline blue to detect callose and infection hyphae. At least 200 appressoria were counted for each fungal strain, and standard errors were calculated from three replicate experiments.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

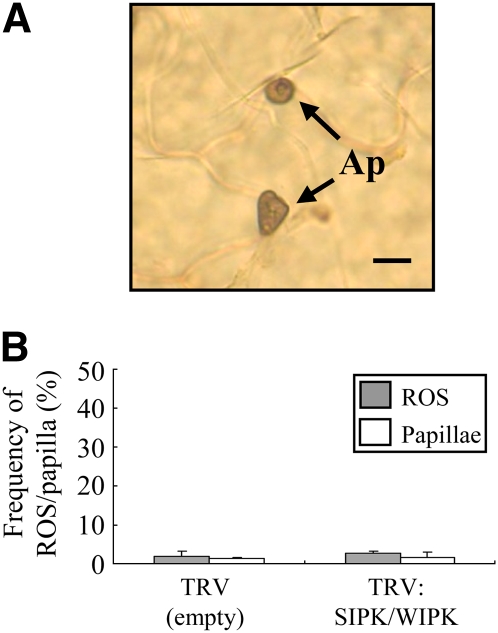

Next, we investigated whether defense responses mediated by the MEK2-SIPK/WIPK signaling cascade could also be involved in nonhost resistance to Colletotrichum (i.e., in the immunity shown by an entire plant species against a nonadapted pathogen species) (Nürnberger and Lipka, 2005). We therefore inoculated SIPK WIPK–silenced plants with conidia of the nonadapted maize (Zea mays) anthracnose pathogen, Colletotrichum graminicola, which is normally unable to cause disease on N. benthamiana plants. Although C. graminicola formed appressoria on both control plants and SIPK WIPK-silenced plants, the formation of intracellular infection hyphae was not observed (Figure 5A), and no disease symptoms were produced. To evaluate the involvement of plant defense responses in restricting appressorial penetration by C. graminicola, leaves were stained with aniline blue and DAB to detect callose and ROS accumulation, respectively, at 72 HAI. As shown in Figure 5B, callose deposition and ROS accumulation were rarely detected beneath the appressoria of C. graminicola in either control plants or SIPK WIPK–silenced plants. This result suggests that the nonhost resistance of N. benthamiana to C. graminicola depends on prepenetration defense responses and that the MEK2-SIPK/WIPK cascade does not play an important role in resistance to this nonadapted pathogen.

Figure 5.

Pathogenicity of a Nonadapted Pathogen, C. graminicola, on SIPK WIPK–Silenced Plants.

(A) Microscopy observation of C. graminicola on a SIPK WIPK–silenced leaf of N. benthamiana. Conidia of C. graminicola germinate and form appressoria (Ap) on the leaf surface, but infection hyphae do not develop from appressoria inside host epidermal cells. Bar = 10 μm.

(B) Quantitative analysis of ROS accumulation and papilla formation under appressoria at 72 HAI. Frequency of appressoria with ROS/papilla was counted. Defense responses were rarely observed under appressoria at 72 HAI.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

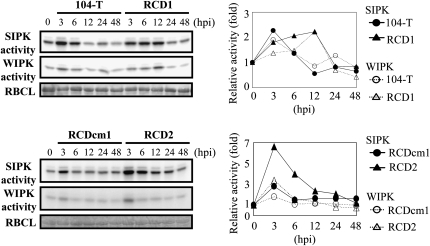

The ssd1 Mutant Induces Higher SIPK and WIPK Activity Than the Wild-Type Strain during Host Infection

In a previous study, we found that the ssd1 mutant induced papilla formation more rapidly than the wild type on onion epidermal cells (Tanaka et al., 2007). To examine whether the mutant induces higher MAP kinase activity in host tissue, we performed an immunocomplex kinase assay using SIPK- and WIPK-specific antibodies. Leaves were sprayed with conidial suspensions, and proteins extracted at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 HAI were used for immunocomplex kinase assays. In leaves inoculated with the wild-type strain (104-T) and an ssd1 mutant complemented with a wild-type copy of SSD1 (RCDcm1), both SIPK and WIPK activities increased up to 3 HAI but declined at 6 HAI and remained at a basal level from 12 to 48 HAI (Figure 6). By contrast, in leaves inoculated with two independent ssd1 knockout mutants (RCD1 and RCD2) (Tanaka et al., 2007), SIPK and WIPK activity increased at 3 HAI, but the activity of both kinases remained at higher levels than in leaves inoculated with the wild-type fungus from 6 to 12 HAI (Figure 6). This result indicates that the ssd1 mutant induces activation of SIPK and WIPK more strongly than does the wild type during host infection.

Figure 6.

Kinase Activity of SIPK and WIPK during Infection.

Conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the wild-type strain 104-T, complemented strain RCDcm1, or ssd1 mutants RCD1 and RCD2 was sprayed onto N. benthamiana leaves. At time points of 0 h (no inoculation) and 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 HAI, proteins were extracted from the leaves of inoculated plants and subjected to an immunocomplex kinase assay. The graph at the right side of each panel indicates the relative kinase activity calculated by comparison with activity at 0 h. Loading controls represent Coomassie blue staining of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (RBCL). Kinase activity of 104-T and RCD1 was determined in three replicated experiments. One set of representative data is shown in this figure. Kinase activity of RCDcm1 and RCD2 was determined in a single experiment.

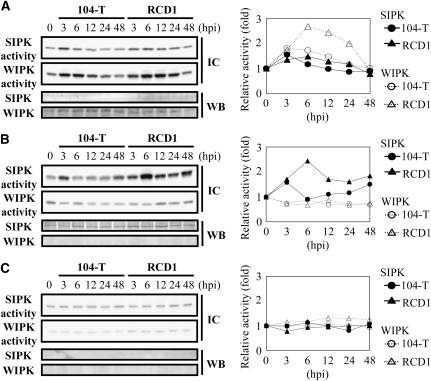

We also evaluated SIPK/WIPK activity in silenced plants inoculated with the wild type and ssd1 mutant RCD1. Interestingly, in SIPK-silenced plants inoculated with the ssd1 mutant, WIPK activity showed a large increase (Figure 7A) compared with nonsilenced plants (Figure 6), and the activity was higher when plants were inoculated with the mutant than with the wild-type fungus. By contrast, SIPK activity showed a less marked increase in WIPK-silenced plants (Figure 7B) than in nonsilenced plants (Figure 6). In plants in which both SIPK and WIPK were silenced, the activation of SIPK and WIPK was not detected at any time points (Figure 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that SIPK and WIPK have complementary roles in plant basal resistance to C. orbiculare.

Figure 7.

Kinase Activity of SIPK and WIPK during Infection of Silenced Plants.

A conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the wild-type 104-T or ssd1 mutant RCD1 was sprayed onto leaves of SIPK-silenced (A), WIPK-silenced (B), and SIPK- and WIPK-silenced (C) plants. At time points of 0 h (no inoculation) and 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 HAI, proteins were extracted from the leaves of inoculated plants and subjected to an immunocomplex kinase assay (IC; top panels). Gene silencing was evaluated by immunoblot analysis (WB; bottom panels). The graph to the right of each panel indicates the relative kinase activity calculated by comparison with activity at 0 h. Kinase activity was determined in silenced plants in two biological replicates. One set of representative data is shown in this figure.

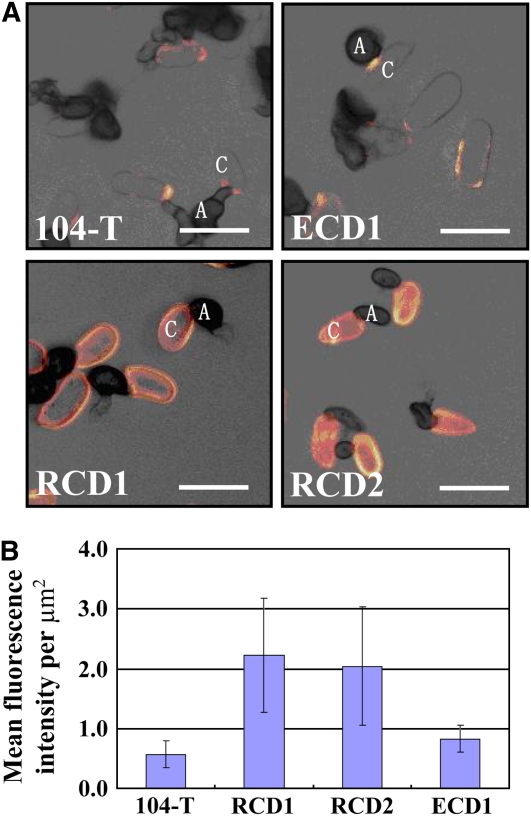

Cell Surface Components of the ssd1 Mutant Induce SIPK and WIPK Activity

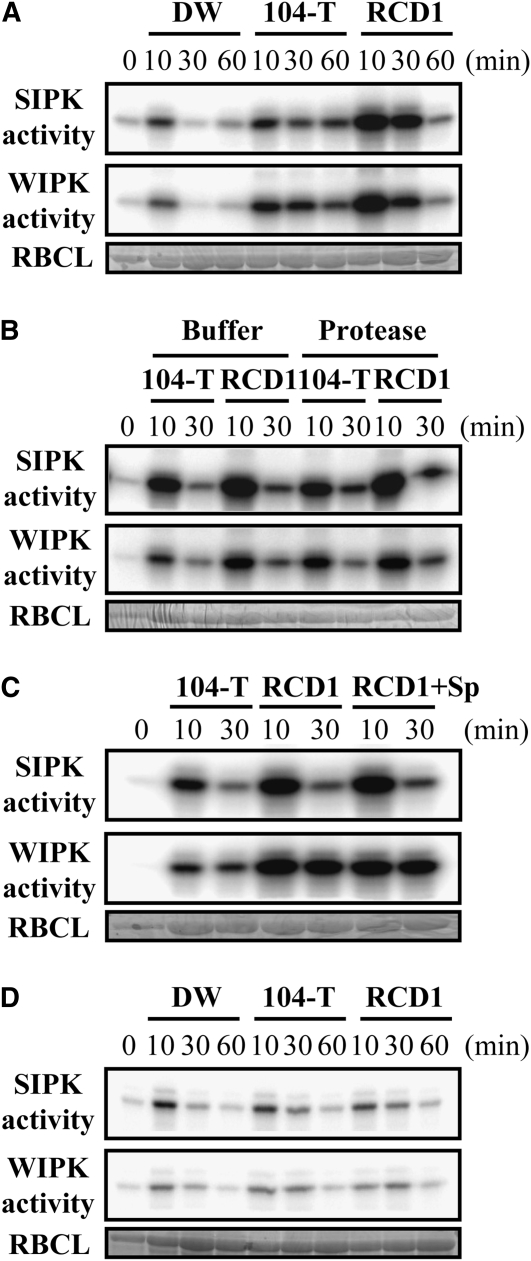

In yeast, SSD1 regulates cell wall composition (Wheeler et al., 2003). Using immunocytochemistry, we also found that mutation of SSD1 affects cell wall composition in C. orbiculare. Thus, extracellular matrix glycoproteins recognized by monoclonal antibody UB20 (Pain et al., 1992; Hughes et al., 1999) were significantly more abundant on the surface of conidia of ssd1 mutants RCD1 and RCD2 than on that of the wild type (Figure 8). To test the hypothesis that fungal cell surface components induce SIPK and WIPK, we examined kinase activity in leaves infiltrated with conidia of the wild type and ssd1 mutant. When heat-inactivated conidia were infiltrated into leaves, higher SIPK and WIPK activity was detected in leaves infiltrated with the ssd1 mutant RCD1 than with 104-T (Figure 9A; see Supplemental Figure 1A online). This result suggests that inert surface component(s) of the mutant conidia induce SIPK/WIPK activity. To examine whether the factor activating SIPK and WIPK is proteinaceous, we infiltrated protease-treated conidia into leaves. The level of SIPK and WIPK activity induced by ssd1 mutant conidia treated with protease was similar to that induced by conidia treated with control protease buffer, and in the case of the wild type, the level was slightly increased (Figure 9B; see Supplemental Figure 1B online), suggesting that the fungal component activating SIPK and WIPK is not proteinaceous.

Figure 8.

Detection of Extracellular Glycoproteins on the Surface of C. orbiculare Conidia by Immunofluorescence Labeling with Antibody UB20.

Conidia of two ssd1 knockout mutants (RCD1 and RCD2), an ectopic mutant (ECD1), and the wild-type strain (104-T) were germinated on glass slides and labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody UB20 followed by goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate.

(A) Confocal microscope images showing overlays of bright-field and fluorescence channels, presented as projections of four optical sections (1 μm thick) with the fluorescence false-colored in orange to improve contrast. Note that conidia (C) of the two ssd1 mutants label strongly and uniformly with UB20, whereas those of the wild type and ectopic mutant are unlabeled or show patchy labeling. A, appressoria. Bars = 10 μm.

(B) Histogram showing the intensity of UB20 immunofluorescence labeling of RCD1 RCD2, ECD1, and 104-T. Data represent mean fluorescence intensities based on analyses of the maximum projections of image stacks from 30 conidia of each fungal strain. Imaging parameters (gain, offset, confocal pinhole, and magnification) were identical for all samples. Error bars indicate sd.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Figure 9.

Activity of SIPK and WIPK in Leaves Infiltrated with Conidia.

(A) SIPK and WIPK activity in leaves infiltrated with conidia. Proteins were extracted at time points of 10, 30, and 60 min after infiltration with distilled water (DW) or a conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the wild-type 104-T or ssd1 mutant RCD1.

(B) SIPK and WIPK activity in leaves infiltrated with conidia treated with protease. Proteins were extracted at 10 and 30 min after infiltration of conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the wild-type 104-T and ssd1 mutant RCD1 treated with 3 mg/mL actinase E in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, buffer at 37°C for 60 min.

(C) SIPK and WIPK activity in leaves infiltrated with conidia suspended in exudate from wild-type conidia. Proteins were extracted at 10 and 30 min after infiltration of conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) of the wild type (104-T), ssd1 mutant (RCD1), and ssd1 mutant suspended in conidial exudate of the wild type (RCD1+Sp).

(D) SIPK and WIPK activity in leaves infiltrated with incubated conidial supernatant. Proteins were extracted at time points of 10, 30, and 60 min after infiltration of distilled water (DW) or incubated conidial supernatant of the wild type (104-T) and ssd1 mutant (RCD1). Kinase activity was determined in two replicate experiments. One set of representative data is shown in this figure. Loading controls are presented as Coomassie blue staining of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (RBCL).

An alternative explanation for the observed difference in kinase induction between the wild type and ssd1 mutant is that wild-type conidia produce diffusible suppressors of SIPK and WIPK. To evaluate this possibility, we tested whether conidial exudates have suppressor activity against SIPK and WIPK. The level of SIPK and WIPK activity in leaves infiltrated with ssd1 mutant conidia suspended in conidial exudate of the wild type was similar to that of mutant conidia alone (Figure 9C; see Supplemental Figure 1C online). This result suggests that the wild type does not produce diffusible suppressors of SIPK and WIPK on the plant surface during germination. We also tested whether cell-free conidial exudates have inducer activity for SIPK and WIPK. When exudates from either mutant or wild-type conidia were infiltrated alone, the detected kinase activities were low, similar to the kinase activity of the distilled water control (Figure 9D; see Supplemental Figure 1D online). These results suggest that the induction of SIPK and WIPK activities by the ssd1 mutant is not due to an inability to suppress these host responses but rather to a specific induction of kinase activity by surface components of the mutant.

DISCUSSION

The existence of basal resistance in plants has been inferred by the identification of mutants that are more susceptible to adapted pathogens than are wild-type plants (Dangl and Jones, 2001). However, analysis of basal resistance is problematic because the level of resistance is usually insufficient to completely restrict pathogen infection, unlike the resistance conferred by R genes. In this study, we sought to identify the plant signaling pathways involved in basal resistance.

Several previous studies have evaluated the involvement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in disease resistance. In tobacco, the MEK2-SIPK/WIPK cascade regulates multiple defense responses, including the hypersensitive cell death response (Yang et al., 2001). SIPK and WIPK are activated by the endogenous signal WAF-1 in tobacco mosaic virus–infected tobacco leaves, and this activation results in enhanced disease resistance (Seo et al., 2003). MEK2-SIPK/NTF6 plays a pivotal role in nitric oxide and ROS generation (Asai et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis thaliana, MPK6 and MPK3, orthologs of SIPK and WIPK, respectively, regulate the synthesis of camalexin, the major Arabidopsis phytoalexin (Ren et al., 2008). However, there is no information about the role of this MAPK pathway in basal resistance to adapted pathogens. Here, we have demonstrated that MEK2 and SIPK/WIPK are involved in basal resistance to C. orbiculare by gene silencing experiments in N. benthamiana, where knockdown of these genes allowed full infection by a fungal mutant that is normally restricted by cell wall–associated defense responses in wild-type plants (Figures 3 and 4). By contrast, infection assays using the nonadapted maize anthracnose pathogen, C. graminicola, revealed that the SIPK/WIPK-mediated signaling pathway does not play a central role in nonhost resistance (Figure 5A). Microscopy observations suggested that plant defense responses to this nonadapted pathogen differed from those mounted against the C. orbiculare ssd1 mutant (Figure 5B). It is possible that nonhost resistance is expressed at prepenetration stage, involving defense mechanisms that operate independently of the SIPK/WIPK-mediated signaling pathway.

The ssd1 mutant of C. orbiculare used in this study is deficient in a gene orthologous to S. cerevisiae SSD1 (Tanaka et al., 2007). The bakers' yeast S. cerevisiae is not a human pathogen in healthy individuals but is increasingly being isolated from immunocompromised patients. Deletion of the SSD1 gene causes yeast to be more virulent in the mouse infection model, and the ssd1Δ mutant elicits potent proinflammatory cytokines from macrophages in vitro (Wheeler et al., 2003). These authors presented evidence that quantitative and qualitative changes in cell wall components, such as β-glucan or chitin, in the yeast ssd1 mutant result in misrecognition by the mammalian innate immune system.

In this study, infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves with heat-inactivated conidia of the C. orbulare ssd1 mutant induced greater SIPK and WIPK activity than infiltration with wild-type conidia (Figure 9A). Although certain extracellular glycoproteins were more abundant on the surface of mutant conidia, these are unlikely to function in host recognition since treatment of the conidia with protease did not affect SIPK and WIPK induction (Figure 9B). These results suggest that polysaccharide components, such as glucans or chitin, on the fungal cell surface may induce plant innate immunity via activation of the SIPK/ WIPK signaling pathway and that the altered surface composition of the ssd1 mutant provides a stronger inducing signal than does the surface of the wild type.

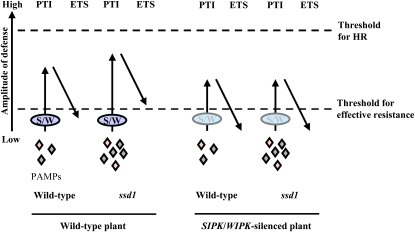

Jones and Dangl (2006) proposed that the level of plant basal resistance is a summation of PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) minus the effect of effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS), as illustrated in their zigzag model. Our findings can be interpreted in relation to this model, as shown in Figure 10. In wild-type plants, the recognition of wild-type fungal PAMPs induces PTI through the MEK2-SIPK/WIPK pathway, but PTI is sufficiently suppressed by ETS to allow successful infection. By contrast, recognition of the modified PAMPs displayed by the ssd1 mutant induces a higher level of PTI that cannot be suppressed by ETS below the threshold for effective resistance, resulting in attenuated pathogenicity. When PTI is compromised by the silencing of SIPK/WIPK, ETS by the ssd1 mutant is again sufficient to reduce the amplitude of plant defense responses below the threshold for effective resistance, resulting in successful infection. Additionally, the wild-type fungus has slightly increased infectivity when PTI is reduced by silencing of SIPK/WIPK. Thus, the activity of SIPK/WIPK correlates with the level of PTI. In Arabidopsis, transcriptional overexpression of MKK7 (MAPKK) conferred enhanced resistance to compatible pathogens Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicora and Hyaloperonospora parasitica (Zhang et al., 2007). Moreover, transgenic potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants that carry a constitutively active form of potato MEK2, orthologous to tobacco MEK2, driven by a pathogen-inducible promoter of potato showed enhanced resistance to the adapted pathogens Phytophthora infestans and Alternaria solani (Yamamizo et al., 2006). Together with our own findings, these data suggest that infection by adapted pathogens can be restricted by basal resistance, provided that activation of the MAPK signaling pathway is sufficiently strong. In particular, it seems that early activation of the MAPK signaling pathway is important for counteracting penetration by the C. orbiculare ssd1 mutant, which may in turn regulate the expression of host genes required for cell wall–associated defense responses, such as deposition of callose papillae.

Figure 10.

Schematic Model for Basal Resistance in Compatible Interactions Based on the Zigzag Model.

This model summarizes the quantitative output of the plant immune system, based on the summation of PTI and ETS in compatible interactions, as proposed in the zigzag model of Jones and Dangl (2006). In the case of a wild-type plant attacked by the wild-type fungus, PTI mediated through SIPK/WIPK (S/W) is suppressed by ETS, resulting in lesion formation. However, PTI by the ssd1 mutant is induced to higher levels than by the wild-type fungus, and ETS is not sufficient to suppress PTI below the threshold required for effective resistance, resulting in attenuated pathogenicity. In the case of SIPK WIPK–silenced plants, the level of PTI induced by the wild-type fungus and ssd1 mutant is reduced compared with that of wild-type plants. ETS by the ssd1 mutant suppresses PTI below the threshold for effective resistance, resulting in lesion formation. Thus, the SIPK/WIPK activity induced by the wild-type fungus and ssd1 mutant correlates with PTI, and the threshold for effective resistance depends on the sum of PTI minus ETS. HR, hypersensitive response.

Bacterial pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells through the Type III secretion system to suppress basal immune responses (Chisholm et al., 2006). Fungal pathogens, particularly those that form long-term biotrophic relationships with their hosts, may also suppress host defense reactions, although experimental evidence to support this assumption has been scarce (Panstruga, 2003). A specific effector delivery apparatus, like the Type III secretion system of Gram-negative bacteria, has not been discovered for fungal pathogens. However, a characteristic feature of most biotrophic fungi is their ability to form specialized infection structures inside host cells called haustoria (O'Connell and Panstruga, 2006). Fungal effectors may be secreted from haustoria into the extrahaustorial matrix or plant apoplast, from where they are presumed to be transferred into host cells (Chisholm et al., 2006). C. orbiculare does not form haustoria; however, during the initial biotrophic phase of infection, it produces intracellular hyphae inside living host cells, which may similarly function in effector delivery (Perfect et al., 1999). It is also possible that C. orbiculare conidia produce diffusible suppressors during germination on the plant surface to overcome host resistance to appressorium-mediated penetration. However, this seems unlikely, since exudates from conidia germinating in vitro could not suppress MAPK activity. Immunocomplex kinase assays revealed that MAPK activation occurs from 3 to 6 HAI in leaves inoculated with wild-type C. orbiculare (Figure 6). At this early stage of infection, C. orbiculare is engaged in conidial germination and appressorium morphogenesis on the plant surface and has not yet penetrated epidermal cells. These morphogenetic events are likely to be tightly coordinated with biosynthesis and remodeling of the fungal cell wall. Thus, different PAMPs may be displayed on the fungal cell surface and recognized by plant PAMP receptors to trigger MAPK-mediated defense responses.

METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions and Fungal Strains

Nicotiana benthamiana was grown in a controlled environment chamber (16 h photoperiod, 24°C). Colletotrichum orbiculare isolate 104-T (MAFF240422) was the wild-type strain used in this study. The ssd1 mutants, RCD1, RCD2, and the complemented strain, RCDcm1, were described previously (Tanaka et al., 2007). Colletotrichum graminicola isolate MAFF236902 was obtained from the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences GenBank, Tsukuba, Japan. All fungal cultures were maintained at 24°C on potato dextrose agar medium (Difco).

Pathogen Inoculation and Cytological Assays

For inoculation with fungal pathogens, the upper leaves of 3-week-old N. benthamiana plants were sprayed with 2 mL of conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL) and incubated in a humid plastic box at 24°C. For pathogenicity tests, inoculated leaves were observed for symptoms at 5 DAI. In the case of gene-silenced plants, the upper leaves were inoculated with conidia 3 to 4 weeks after inoculation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying the VIGS constructs. For evaluation of kinase activity, the inoculated leaves were collected at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 HAI. Cytological observations and the detection of callose depositions (papillae) were performed as previously described (Tanaka et al., 2007). ROS accumulation was detected by staining with DAB (Yoshioka et al., 2003). Extracellular matrix glycoproteins were labeled on conidia germinating on glass microscope slides using monoclonal antibody UB20 for immunofluorescence microscopy (Pain et al., 1992; Hughes et al., 1999). Fluorescence was imaged with a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope and the 488-nm line of an argon laser. Images were analyzed and processed with LCS Lite software (Leica Microsystems) and Adobe Photoshop 8.0.

VIGS

VIGS was performed as previously described (Ratcliff et al., 2001). The following primers were used to amplify cDNA fragments of Nb HSP90, Nb RAR1, and Nb SGT1 from an N. benthamiana cDNA library (Yoshioka et al., 2003). Restriction sites (underlined) were added to the 5′-ends of the following forward and reverse primers for cloning into a tobacco rattle virus vector pTV00 (RNA2): NbHSP90-F-ClaI (5′-CCATCGATACCCTGACTATCATTGATAGTGGTATTGGT-3′) and NbHSP90-R-BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCTAATTTTTGTCCCCCTCCAAAGGTTC-3′) (restriction sites are underlined), which produced a 301-bp fragment; NbRAR1-F-ClaI (5′-CCATCGATAGGAAAGCACACAACAGAAA-3′) and NbRAR1-R-BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCAGCATTTCCATCCTCTCATC-3′), which produced a 395-bp fragment; and NbSGT1-F-ClaI (5′-CCATCGATTCGCCGTTGACCTGTACACTCAAGC-3′) and NbSGT1-R-BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCGCAGGTGTTATCTTGCCAAACAACCTAGG-3′), which produced a 633-bp fragment. The cDNA fragments of Nb MEK1, Nb MEK2, Nb SIPK, Nb WIPK, Nb RBOHA, and Nb RBOHB were prepared from an N. benthamiana cDNA library (Asai et al., 2008). N. benthamiana was infected by viruses via Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of infectious constructs. The vectors pBINTRA6 and pTV00, containing the inserts RNA1 and RNA2, respectively, were transformed separately by electroporation into Agrobacterium strain GV3101, which includes the transformation helper plasmid pSoup (Hellens et al., 2000). A mixture of equal parts of Agrobacterium suspensions containing RNA1 and RNA2 was inoculated into 2- to 3-week-old N. benthamiana seedlings. The effect of VIGS was confirmed by RT-PCR. Total RNA (2 μg) was extracted from leaves inoculated with the ssd1 mutant at 5 DAI using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR was performed using the ReverTra Dash RT-PCR kit (Toyobo) following the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Infiltration of Conidia into Leaves

Conidia of the wild type (104-T) and ssd1 mutant (RCD1) were harvested from 6-d-old cultures and washed twice in 5 mL of sterilized distilled water, and the concentration of the conidia was then adjusted to 1 × 106 conidia/mL. Approximately 200 μL of conidial suspension was gently pressure-infiltrated onto the abaxial surface of leaves using a 1-mL syringe. For heat-inactivation, conidial suspension was boiled at 100°C for 5 min. For protease treatment, a pellet of cells (1 × 106 conidia) was diluted with 3 mg/mL Actinase E (Kaken Pharmaceutical) in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. After incubation, the conidial suspension was boiled at 100°C for 5 min to inactivate Actinase E and washed twice with sterilized distilled water. Cell-free exudates were collected from germinating conidia as follows. One milliliter of conidial suspension (1 × 105 conidia/mL) was incubated at 24°C for 6 h on a Petri dish (3-cm diameter), and the supernatant was collected with a micropipette and centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 2 min).

Immunocomplex Kinase Assay and Immunoblot Analysis

Immunocomplex kinase assays and immunoblot analysis were performed as previously described, with some modifications (Katou et al., 2003; Asai et al., 2008). The kinase reaction was performed at 25°C for 30 min in a volume of 25 μL reaction buffer containing 0.5 mg/mL myelin basic protein (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 μM ATP, and 2.5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. The phosphorylated myelin basic protein was detected using a BAS-1800II imaging system (Fuji LifeScience). The kinase activity was evaluated using MultiGauge software. SIPK protein was detected with 50 μg of total protein. WIPK protein was immunoprecipitated with 200 μg of total protein and anti-WIPK antibody and subjected to immunoblot analysis. The signals were detected with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: AB245428 (Co SSD1), AB360635 (Nb MEK1), AB360636 (Nb MEK2), AB373025 (Nb SIPK), AB098729 (Nb WIPK), AB079498 (Nb RBOHA), AB079499 (Nb RBOHB), AF480487 (Nb RAR1), AF494083 (Nb SGT1), and AY368904 (Nb HSP90).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Quantitative Analysis of Kinase Activity Shown in Figure 9.

Supplemental Table 1. Primers Used for RT-PCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuko Ohashi and Shigemi Seo (National Institute of Agrobiological Resources) for providing SIPK- and WIPK-specific antibodies. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (19380029 and 21380031) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Fellowships from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (19380024).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Yasuyuki Kubo (y_kubo@kpu.ac.jp).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Asai, S., Ohta, K., and Yoshioka, H. (2008). MAPK signaling regulates nitric oxide and NADPH oxidase-dependent oxidative bursts in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell 20: 1390–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, S.T., Coaker, G., Day, B., and Staskawicz, B.J. (2006). Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124: 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L., and Jones, J.D. (2001). Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, P.J. (2007). How plants recognize pathogens and defend themselves. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64: 2726–2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix, G., Duran, J.D., Volko, S., and Boller, T. (1999). Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 18: 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens, R.P., Edwards, E.A., Leyland, N.R., Bean, S., and Mullineaux, P.M. (2000). pGreen: A versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 819–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, H.B., Carzaniga, R., Rawlings, S.L., Green, J.R., and O'Connell, R.J. (1999). Spore surface glycoproteins of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum are recognized by a monoclonal antibody which inhibits adhesion to polystyrene. Microbiology 145: 1927–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A., and Takemoto, D. (2004). Plant innate immunity-direct and indirect recognition of general and specific pathogen-associated molecules. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16: 48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D., and Dangl, J.L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku, H., Nishizawa, Y., Ishii-Minami, N., Akimoto-Tomiyama, C., Dohmae, N., Takio, K., Minami, E., and Shibuya, N. (2006). Plant cells recognize chitin fragments for defense signaling through a plasma membrane receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 11086–11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou, S., Yamamoto, A., Yoshioka, H., Kawakita, K., and Doke, N. (2003). Functional analysis of potato mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, StMEK1. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 69: 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, G., Zipfel, C., Robatzek, S., Niehaus, K., Boller, T., and Felix, G. (2004). The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 16: 3496–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugé, R., and De Wit, P.J. (1998). Fungal avirulence genes: Structure and possible functions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 24: 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger, T., Brunner, F., Kemmerling, B., and Piater, L. (2004). Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarity and obvious differences. Immunol. Rev. 198: 249–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger, T., and Lipka, V. (2005). Non-host resistance in plants: new insights into an old phenomenon. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, R.J., and Panstruga, R. (2006). Tête à tête inside a plant cell: Establishing compatibility between plants and biotrophic fungi and oomycetes. New Phytol. 171: 699–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain, N.A., O'Connell, R.J., Bailey, J.A., and Green, J.R. (1992). Monoclonal antibodies which show restricted binding to four Colletotrichum species: C. lindemuthianum, C. malvarum, C. orbiculare and C. trifolii. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 41: 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Panstruga, R. (2003). Establishing compatibility between plants and obligate biotrophic pathogens. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect, S.E., Hughes, H.B., O'Connell, R.J., and Green, J.R. (1999). Colletotrichum: A model genus for studies on pathology and fungal-plant interactions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27: 186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, F., Martin-Hernandez, A.M., and Baulcombe, D.C. (2001). Tobacco rattle virus as a vector for analysis of gene function by silencing. Plant J. 25: 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D., Liu, Y., Yang, K.Y., Han, L., Mao, G., Glazebrook, J., and Zhang, S. (2008). A fungal-responsive MAPK cascade regulates phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 5638–5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S., Seto, H., Koshino, H., Yoshida, S., and Ohashi, Y. (2003). A diterpene as an endogenous signal for the activation of defense responses to infection with tobacco mosaic virus and wounding in tobacco. Plant Cell 15: 863–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S., Goodwin, P.H., and Hsiang, T. (2001). Infection of Nicotiana species by the anthracnose fungus, Colletotrichum orbiculare. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107: 767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S., Yamada, K., Yabumoto, K., Fujii, S., Huser, A., Tsuji, G., Koga, H., Dohi, K., Mori, M., Shiraishi, T., O'Connell, R., and Kubo, Y. (2007). Saccharomyces cerevisiae SSD1 orthologs are essential for host infection by the ascomycete plant pathogens Colletotrichum lagenarium and Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Microbiol. 64: 1332–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen, H. (2003). Fresh insights into processes of nonhost resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6: 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, S.L., and Talbot, N.J. (2001). Surface attachment and pre-penetration stage development by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39: 386–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto, N., Kakitani, M., Iwamatsu, A., Yoshikawa, M., Yamaoka, N., and Ishida, I. (1997). The structure and function of a soybean β-glucan-elicitor-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 1029–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, R.T., Kupiec, M., Magnelli, P., Abeijon, C., and Fink, G.R. (2003). A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant with increased virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 2766–2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamizo, C., Kuchimura, K., Kobayashi, A., Katou, S., Kawakita, K., Jones, J.D., Doke, N., and Yoshioka, H. (2006). Rewiring mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by positive feedback confers potato blight resistance. Plant Physiol. 140: 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.Y., Liu, Y., and Zhang, S. (2001). Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in disease resistance in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, H., Numata, N., Nakajima, K., Katou, S., Kawakita, K., Rowland, O., Jones, J.D., and Doke, N. (2003). Nicotiana benthamiana gp91phox homologs NbrbohA and NbrbohB participate in H2O2 accumulation and resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell 15: 706–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Dai, Y., Xiong, Y., DeFraia, C., Li, J., Dong, X., and Mou, Z. (2007). Overexpression of Arabidopsis MAP kinase kinase 7 leads to activation of plant basal and systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 52: 1066–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.