Abstract

We systematically reviewed the clinical trials which recruited antioxidants in the therapy of pancreatitis and evaluated whether antioxidants improve the outcome of patients with pancreatitis. Electronic bibliographic databases were searched for any studies which investigated the use of antioxidants in the management of acute pancreatitis (AP) or chronic pancreatitis (CP) and in the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (post-ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) up to February 2009. Twenty-two randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trials met our criteria and were included in the review. Except for a cocktail of antioxidants which showed improvement in outcomes in three different clinical trials, the results of the administration of other antioxidants in both AP and CP clinical trials were incongruent and heterogeneous. Furthermore, antioxidant therapy including allopurinol and N-acetylcysteine failed to prevent the onset of PEP in almost all trials. In conclusion, the present data do not support a benefit of antioxidant therapy alone or in combination with conventional therapy in the management of AP, CP or PEP. Further double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with large sample size need to be conducted.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography pancreatitis, Oxidative stress, Therapy, Acute pancreatitis, Chronic pancreatitis

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatitis, both chronic and acute, contributes to thousands of annual hospital admissions and consecutive complications[1]. Acute pancreatitis (AP), an acute inflammatory condition, is thought to be due to activation of enzymes in the pancreatic acinar cells, with inflammation spreading into the surrounding tissues[2]. Patients with AP were either treated with strict bowel rest or given parenteral nutrition to allow the pancreas to rest until the serum enzyme levels returned to normal[3]. Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive inflammatory disorder that is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe abdominal pain. Affected patients typically suffer years of disabling pain, and conventional therapeutic interventions are often unable to offer satisfactory analgesia[4].

Oxidative stress caused by short lived intracellular reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, can oxidize lipids in the cell membrane, proteins, depolarize the mitochondrial membrane, and induce DNA fragmentation. Active free radicals in the body can be produced during diseases or exposure to xenobiotics[5,6].

Basic and clinical evidence suggests that the pathogenesis of both AP and CP can be associated with oxidative stress seeming independent of the etiology of pancreatitis, because oxidative stress is observed in different experimental pancreatitis models[7,8]. Findings show that free radical activity and oxidative stress indices such as lipid peroxide levels are higher in the blood and duodenal juice of patients with AP or CP[9,10].

Based on the mentioned findings, the idea of using antioxidant regimens in the management of both AP and CP as a supplement and complementary in combination with its traditional therapy is rational and reasonable. As a result of this hypothesis, antioxidant therapy should improve the inflammatory process that is involved in pancreatitis and therefore ameliorate the recovery rate.

In addition, pancreatitis is the most common serious complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), occurring in 1%-7% of cases[11]. Although, the exact mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) are not clear, the role of oxidative stress cannot be neglected. Therefore, the use of antioxidants before, during or after this intervention has already been studied in a few clinical trials[12,13]. Although some clinical trials have proved the benefits of using various antioxidants in AP or CP, there are still controversies[14].

To our knowledge, there is no definite consensus on the benefits of antioxidant therapy in the management of AP or CP. Our objective was to systematically review and summarize the literature on antioxidant therapies for AP and CP as well as PEP, to provide recommendations for future research.

METHODS

PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Cochrane library database, and Evidence based medicine reviews were searched for any relevant studies that investigated the use of antioxidants in the management of AP or CP and in the prevention of PEP up to February 2009. We also hand-searched references in key articles. The search terms were: AP or CP, pancreatic inflammation, antioxidant, vitamin, superoxide dismutase, manganese, glutamine, butylated hydroxyanisole, taurine, glutathione, curcumin, catalase, peroxidase, lutein, xanthophylls, zeaxanthin, selenium, riboflavin, zinc, carotenoid, cobalamin, retinol, alpha-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, beta-carotene, carotene and all MeSH terms for pharmacologically active antioxidants. Studies were limited to clinical trials and those written in the English language.

To assess the quality of clinical trials, we employed the Jadad score, a previously validated instrument that assesses trials based on appropriate randomization, blinding, and description of study withdrawals or dropouts[15]. The description of this score is as follows: (1) whether randomized (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (2) whether randomization was described appropriately (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (3) double-blind (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (4) was the double-blinding described appropriately (yes = 1 point, no = 0); (5) whether withdrawals and dropouts were described (yes = 1 point, no = 0). The quality score ranges from 0 to 5 points; a low-quality report score is ≤ 2 and a high-quality report score is at least 3.

Data synthesis was conducted by three reviewers who read the title and abstract of the search results separately to eliminate duplicates, reviews, case studies, and uncontrolled trials. The inclusion criteria were that the studies should be clinical trials which used an antioxidant for the treatment or prevention of pancreatitis. Outcomes of the studies were not the point of selection and all studies that analyzed the effects of an antioxidant on pancreatitis, from pain reduction[16] to changes in plasma cytokines, were included.

Data from selected studies were extracted in the form of 2 × 2 tables. All included studies were weighted and pooled. The data were analyzed using Statsdirect (2.7.3). Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel and DerSimonian-Laird methods. The Cochran Q test was used to test heterogeneity. The event rate in the experimental (intervention) group against the event rate in the control group was calculated using L’Abbe plot as an aid to explore the heterogeneity of effect estimates. Funnel plot analysis was used as a publication bias indicator.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A total of 211 potentially relevant papers were identified, of which 22 papers were eligible[4,16-36]. Amongst the 22 papers, 19 (86%) scored 3 and only three studies[17,25,31] scored 2 or lower according to the Jadad score. Table 1 presents controlled clinical trials of antioxidants in patients with AP or CP. Trials that used antioxidants to prevent PEP are summarized in Table 2. To perform a meta-analysis we included only four studies in which allopurinol was used in PEP.

Table 1.

Controlled clinical trials of antioxidants in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis

| Study/Ref. | Drug/supplements | Study design | Jadadscore |

Participants |

Treatment (intervention) |

Outcome (results) |

Adverse effects/events | ||

| Case | Control | Clinical | Laboratory | ||||||

| Bhardwaj et al[16] 2009 | Combined antioxidant (organic selenium, vitamin C, β-carotene, α-tocopherol and methionine) | Randomized; double blind; placebo-controlled | 5 | 147 patients with CP | 71 patients; combined antioxidants: 600 μg organic selenium, 0.54 g ascorbic acid, 9000 IU β-carotene, 270 IU α-tocopherol and 2 g methionine; per day; for 6 mo | 76 patients; placebo | Number of painful days per month2 Numbers of oral analgesic tablets and parenteral analgesic injections per month2 Hospitalization2 Percentage of patients become pain-free2 Number of man-days lost per month2 | Lipid peroxidation (TBARS)2 Serum SOD2 Total antioxidant capacity (FRAP)1 Serum vitamin A1 Serum vitamin C1 Serum vitamin E1 Erythrocyte superoxide dismutase2 | Headache & constipation (all during the first month of treatment) |

| Xue et al[17] 2008 | Glutamine | Randomized | 1 | 80 patients with severe AP | 38 patients; 100 mL/d of 20% AGD intravenous infusion; for 10 d; starting on the day 1 (Early treatment) | 38 patients; 100 mL/d of 20% AGD intravenous infusion/for 10 d starting on the day 5 (Late treatment) | Infection rate2 Operation rate2 Mortality2 Hospitalization2 Duration of ARDS2 Renal failure2 Acute hepatitis2 Encephalopathy2 Enteroparalysis2 Duration of shock2 15-d APACHE II core2 | - | |

| Fuentes-Orozco et al[18] 2008 | Glutamine | Randomized; double blind; controlled | 4 | 44 patients with AP | 22 patients; 0.4 g/kg per day of L-alanyl-L-Glutamine in standard TPN; 10 d | 22 patients; standard TPN; 10 d | Infectious morbidity2 Hospital stay day3 Mortality3 | Serum IL-101 Serum IL-62 CRP2 Ig A1 Protein1 Albumin1 Leucocyte2 Total lymphocyte1 Nitrogen balance was (+) in treated group vs (-) in control group | - |

| Siriwardena et al[19] 2007 | Combined antioxidant (N-acetylcysteine, selenium, vitamin C) | Randomized; double blind; placebo- controlled | 5 | 43 patients with severe AP | 22 patients; N-acetylcysteine, selenium and vitamin C; for 7 d | 21 patients; placebo | Organ dysfunction3 APACHE-II3 Hospitalization3 All case mortality3 | Serum vitamin C3 Serum selenium3 GSH/GSSG ratio3 CRP3 | - |

| Kirk et al[4] 2006 | Combined antioxidant (selenium, β-carotene, L-methionine, vitamins C and E) | Randomized; double-blind; placebo-controlled; crossover | 4 | 36 patients with CP | 36 patients; Antox tablet: 75 mg of selenium, 3 mg β-carotene, 47 mg vitamin E, 150 mg vitamin C, and 400 mg methionon; four times per day; for 10 wk | 36 patients; placebo; four times per day; for 10 wk | Quality of life1 Pain2 Physical and social functioning1 Health perception1 Emotional functioning, energy, mental health3 | Plasma selenium1 Plasma vitamin C1 Plasma vitamin E1 Plasma β-carotene1 | Two patients complained of nausea and one of an unpleasant taste during treatment with Antox |

| Durgaprasad et al[20] 2005 | Curcumin | Randomized; single blind; placebo- controlled | 3 | 20 patients of tropical pancreatitis (CP) | Eight patients; capsule: 500 mg curcumin (95%) with 5 mg of piperine; three times per day; for 6 wk | Seven patients; placebo (lactose) | Pain3 | Erythrocyte MDA2 GSH level3 | - |

| Du et al[21] 2003 | Vitamin C | Randomized; controlled | 3 | 84 patients with AP | 40 patients; IV vitamin C; 10 g/d; for 5 d | 44 patients; IV vitamin C; 1 g/d; for 5 d | Hospitalization2 Deterioration of disease2 Improvement of disease1 Cure rate1 | Tnf-α2 IL-12 IL-82 CRP2 Serum interleukin-2 receptor2 Plasma vitamin C1 Plasma lipideroxide1 Plasma vitamin E1 Plasma β-carotene1 Whole blood glutathione1 Activity of erythrocyte superoxide dismutase1 Erythrocyte catalase1 | - |

| Ockenga et al[22] 2002 | Glutamine | Randomized, double blind; controlled | 4 | 28 patients with AP | Standard TPN which contains 0.3 g/kg per day L-alanine-L-glutamine; at least 1 wk | Standard TPN | Hospitalization2 Duration of TPN2 Cost of TPN3 | Cholinesterase1 Albumin1 lymphocyte count1 CRP2 | - |

| de Beaux et al[23] 1998 | Glutamine | Randomized; double-blind; controlled | 5 | 14 patients with AP | Six patients; 0.22 g/kg per day of glycyl-glutamine in standard TPN; for 7 d | Seven patients; standard TPN | - | Lymphocytic proliferation (by DNA synthesis)1 TNF3 IL-63 IL-82 | - |

| Banks et al[24] 1997 | Allopurinol | Randomized, double-blind, two-period crossover clinical trial | 4 | 13 patients with CP | 13 patients; 300 mg/d allopurinol; 4 wk | 13 patients; placebo | Pain3 | Uric acid level2 | - |

| Sharer et al[25] 1995 | Glutathione precursors (S-adenosyl methionine and N-acetylcysteine) | Randomized | - | 79 patients with AP | SAMe 43 mg/kg and N-acetylcysteine 300 mg/kg | - | APACHE II score reduction3 Complication rate3 Days in hospital3 Mortality3 | - | - |

| Bilton et al[26] 1994 | S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) | Randomized; double-blind; crossover; placebo- controlled | 5 | 20 patients with AP or CP | 20 patients; SAMe 2.4g/d; 10 wk | Placebo | Attack rate and background pain3 | Free radical activity2 Serum selenium2 Serum β-carotene2 Serum vitamin E23 Serum vitamin C2 Serum SAMe1 | - |

| Selenium and β-carotene + SAMe | 20 patients; SAMe 2.4 g/d, Selenium 600 μg and β-carotene 9000 IU; 10 wk | Free radical activity2 Serum selenium2 Serum β-carotene1 Serum vitamin E13 Serum vitamin C2 Serum SAMe1 | |||||||

| Salim[27] 1991 | Allopurinol; dimethyl sulfoxide | Randomized; double-blind; placebo- controlled | 4 | 78 patients with CP | 25 patients; allopurinol; 50 mg four times per day, with analgesic regimen (IM pethidine hydrochloride; 50 mg every 4 h, and IM metoclopramide hydrochloride; 10 mg every 8 h) | 27 patients; placebo with analgesic regimen | Pain2 Hospitalization2 Epigastric tenderness2 | WBC count2 Serum amylase2 Serum LDH2 | Allergies General malaise Headache Nausea Vomiting Dyspepsia Abdominal pain |

| 26 patients; dimethyl sulfoxide; 500 mg four times per day; with analgesic regimen | |||||||||

| Uden et al[28,29] 1992, 1990 | Combined antioxidant (selenium, β-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, methionine) | Randomized; double-blind; crossover; placebo- controlled | 5 | 28 patients with CP | 23 patients; daily doses of 600 mg organic selenium, 9000 IU β-carotene, 0.54 g vitamin C, 270 IU vitamin E and 2 g methionine; 10 wk | 23 patients; placebo | Pain2 | Free radical activity2 Serum selenium1 Serum β-carotene1 Serum vitamin E1 Serum SAMe2 | - |

Significant increase as compared with control;

Significant decrease as compared with control;

No significant difference between groups. TBARS: Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; FRAP: Ferric reducing antioxidant power; SOD: Superoxide dismutase; AGD: Alanyl-glutamine dipeptide; CRP: C-reaction protein; MDA: Malondialdehyde; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; GSH: Glutathione; TPN: Total parenteral nutrition; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; IL: Interleukin.

Table 2.

Controlled clinical trials of antioxidant therapy to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis

| Ref. | Drug/supplements | Study design | Jadadscore | n |

Treatment (intervention) |

Outcome (results) |

Adverse effects/events | Other comments | ||

| Case | Control | Primary | Other | |||||||

| Romagnuolo et al[30] 2008 | Allopurinol | Randomized; double blind; placebo-controlled | 4 | 586 | 293 patients; 300 mg oral allopurinol 60 min before ERCP | 293 patients; placebo | Rate of PEP3 (5.5% vs 4.1%) | Disease-related adverse events3 Procedure-related complications3 Hospitalization3 | - | In the non-high-risk group (n = 520), the crude PEP rates were 5.4% for allopurinol and 1.5% for placebo (P = 0.017), favoring placebo, indicating harm associated with allopurinol, whereas in the high-risk group (n = 66), the PEP rates were 6.3% for allopurinol and 23.5% for placebo (P = 0.050), favoring allopurinol |

| Milewski et al[31] 2006 | N-acetylcysteine | Randomized; placebo-controlled | 2 | 106 | 55 patients; 600 mg oral N-acetylcysteine 24 and 12 h before ERCP and 1200 mg IV for 2 d after the ERCP | 51 patients; isotonic IV saline twice for 2 d after the ERCP | Rate of PEP3 (7.3% vs 11.8%) | Urine amylase activity3 Serum amylase activity3 | - | - |

| Katsinelos et al[32] 2005 | Allopurinol | Randomized; double blind; placebo-controlled | 4 | 250 | 125 patients; 600 mg oral allopurinol 15 and 3 h before ERCP | 118 patients; placebo | Rate of PEP2 (3.2% vs 17.8%) | Hospitalization2 Severity of pancreatitis2 | - | - |

| Katsinelos et al[33] 2005 | N-acetylcysteine | Randomized; double-blind; placebo-controlled | 3 | 256 | 124 patients; 70 mg/kg 2 h before and 35 mg/kg at 4 h intervals for a total of 24 h after the procedure | 125 patients; placebo (normal saline solution) | Rate of PEP3 Hospitalization3 | - | Nausea; skin rash; diarrhea; vomiting | - |

| Mosler et al[34] 2005 | Allopurinol | Randomized; double blind; placebo- controlled | 4 | 701 | 355 patients; 600 mg 4 h and 300 mg 1 h oral allopurinol before ERCP | 346 patients; placebo | Rate of PEP3 (13.0% vs 12.1%) | Severity of pancreatitis3 | - | - |

| Lavy et al[35] 2004 | Natural β-carotene | Randomized; double-blind; placebo-controlled | 5 | 321 | 141 patients; 2 g oral β-carotene 12 h before ERCP | 180 patients; placebo | Rate of PEP3 (10% vs 9.4%) | Severe pancreatitis2 | - | - |

| Budzyńska et al[36] 2001 | Allopurinol | Randomized; placebo-controlled | 3 | 300 | 99 patients; 200 mg oral allopurinol 15 and 3 h before ERCP | 101 patients; placebo | Rate of PEP3 (12.1% vs 7.9%) | Severity of pancreatitis3 | - | - |

1Significant increase as compared with control;

Significant decrease as compared with control;

No significant difference between groups. PEP: Post endoscopic pancreatitis.

Antioxidants in AP and CP

Glutamine: Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid both in plasma and in the intracellular free amino acid pool. It is essential for a wide variety of physiologic processes, in particular, the growth and function of immune cells including lymphocytes and macrophages[17]. Glutamine is normally synthesized de novo by a number of cells and therefore is not an essential amino acid. Although glutamine is an antioxidant, in conditions of excess glutamine utilization such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery or severe AP, endogenous glutamine production may not be adequate and glutamine depletion occurs[23].

In four studies[17,18,22,23] glutamine was supplemented to standard total parenteral nutrition (TPN) in AP patients. In one randomized controlled study (n = 28), glutamine was used in AP in combination with standard TPN and demonstrated a decrease in the duration of TPN therapy and hospitalization without a change in the total cost of parenteral feeding[22]. Another similar study (n = 44) showed that even though TPN therapy containing glutamine reduces infectious morbidity, it has no significant effect on hospitalization and total mortality[18]. However, both studies showed laboratory improvement in AP after administration of glutamine such as an increase in serum albumin or decrease in C-reaction protein (CRP).

Proinflammatory cytokine release was assessed in another study with a small patient number (n = 14). Glutamine supplementation did not significantly influence tumor necrosis factor-α or interleukin (IL)-6 release, but, in contrast, median IL-8 release was reduced by day 7 in the glutamine group while it was increased in the conventional group[23]. Another non-blinded study examined the administration of glutamine in AP for 10 d starting either on the day of admission or 5 d after admission. Investigators reported an improvement in all clinical findings including hospitalization, infection, and mortality rate[17]. No adverse effects were reported in these trials.

Allopurinol: Allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that historically has been effective in preventing attacks of acute gouty arthritis, is an effective anti-oxidant with anti-apoptotic effects. It has been shown that allopurinol is a hydroxyl radical scavenger[37,38]. Two studies used allopurinol to reduce chronic pain in CP[24,27]. In one clinical trial (n = 78), CP patients with chronic pain were admitted to hospital and received an analgesic regimen of pethidine with or without allopurinol. Their results showed that allopurinol could reduce pain and gastric tenderness. Hospitalization was also decreased in allopurinol-treated patients[27]. Another clinical study (n = 13) showed that 4 wk of allopurinol administration did not reduce pain in CP when compared with placebo[24]. Allergy, general malaise, and gastrointestinal disturbances were adverse events of allopurinol.

Vitamin C: Ascorbic acid or vitamin C is a monosaccharide antioxidant. This water-soluble vitamin is a reducing agent and can neutralize oxygen species. Vitamin C is an important antioxidant which protects the body from damage caused by inflammation, and high-dose vitamin C can improve immune function[21]. Vitamin C alone was only investigated in one study and other studies used vitamin C in combination with other antioxidants which will be discussed later. In one randomized study (n = 83), 10 g/d of vitamin C was used intravenously compared to 1 g/d of vitamin C in the control group for 5 d in patients with AP. Their results indicated that 10 g vitamin C decreases hospitalization and duration of disease, and increases the cure rate. Proinflammatory cytokines and CRP were also diminished by vitamin C administration[21].

Combined antioxidants (selenium, β-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E and methionine): A combination of various antioxidants including selenium, β-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and methionine was studied in three controlled clinical trials[4,16,28]. In the first clinical trial, the efficacy of antioxidant therapy in the management of pancreatitis was determined using the above combination in CP patients (n = 28). Their results showed that this cocktail can reduce the pain which is experienced by patients[28]. Another study with a slightly larger sample size (n = 36) used the above combination at the same doses but with greater bioavailability in CP patients. In this trial, congruent with the previous trial, pain was reduced after 10 wk of the combined antioxidants. Indeed, quality of life, physical and social functioning, and health perception were also enhanced as a result of antioxidant therapy[4]. The latest published controlled clinical trial in the field of antioxidants and pancreatitis has also used this combination at the same doses as the previous studies. In this larger clinical trial (n = 147), the antioxidants were administered for 6 mo, and showed that, similar to the two preceding trials, pain and hospitalization were reduced[16]. All three studies showed that serum concentrations of the above-mentioned antioxidants were higher after a period of intake and laboratory indices of oxidative stress markers such as lipid peroxidation, free radical activity, and total antioxidant capacity improved after therapy. Another cohort study which is not presented in Table 1 examined this combination of antioxidants in 12 CP patients and showed that this combination reduces pain and hospitalization[39]. Headache, nausea, vomiting, and constipation were some of the adverse effects of this combination. A clinical trial studied the effect of selenium, vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) combination for 7 d in 43 AP patients. All primary endpoints including hospitalization, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, and organ dysfunction were statistically similar between the placebo and antioxidant-treated groups[19].

Curcumin: Curcumin is a polyphenolic compound commonly found in the dietary spice turmeric[40]. Curcumin is an inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB and has various biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiseptic, and anticancer activity[41]. In the one available pilot study (n = 20), patients with CP received 500 mg of curcumin with 5 mg of piperine or placebo for 6 wk. There was a significant reduction in erythrocyte malondialdehyde levels following curcumin therapy when compared with placebo. A significant increase in glutathione (GSH) levels was also observed. There was no corresponding improvement in pain and no adverse effects were reported[20].

Glutathione precursors [S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe)]: SAMe, a highly bioactive metabolite of methionine is a precursor of glutathione, which is the key defense against reactive species. Of the two clinical trials that examined SAMe in pancreatitis, in one, SAMe was administered to AP patients[25] and in the other, SAMe was administered to CP patients[26]. SAMe did not enhance the clinical outcomes in either AP or CP patients. However, laboratory indices such as free radical activity were better after 10 wk of SAMe administration in CP patients. Methionine in combination with other antioxidants was discussed previously under the topic of combined antioxidants.

Antioxidants in PEP

NAC: NAC is a free radical scavenger capable of stimulating glutathione synthesis. NAC was used in two clinical trials. In one of these trial (n = 106), 600 mg NAC was given orally 24 h and 12 h before ERCP and 600 mg was given intravenously, twice a day for 2 d after ERCP. Their results showed that the rate of PEP was not significantly reduced. In addition, urine amylase activity, total bilirubin, alanine, aspartate aminotransferases and white blood cells showed no change[31].

In the other double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 256), patients received intravenous NAC at a loading dose of 70 mg/kg 2 h before and 35 mg/kg at 4-h intervals for a total of 24 h after the procedure. Similar to the previous study, there were no statistical differences in the incidence or severity of PEP grades between the groups. The mean duration of hospitalization for pancreatitis was not different in the NAC group as compared to the placebo group[33]. The results of those studies showed the absence of any beneficial effect of NAC on the incidence and the severity of ERCP-induced pancreatitis.

Natural β-Carotene: β-carotene is a natural antioxidant which has been used as a supplement in various conditions. In a double-blind trial, 321 patients were given a single dose of natural β-carotene, 12 h prior to the procedure, and monitored for procedure complications, antioxidant levels, and plasma oxidation for 24 h post-procedure. The overall incidence of AP was not significantly different between the β-carotene and the placebo groups. The rate of severe pancreatitis was lower in the β-carotene-treated group. No reduction in the incidence of PEP was reported but there may be some protective effect of treatment with β-carotene regarding the severity of disease. Adverse events were not reported[35].

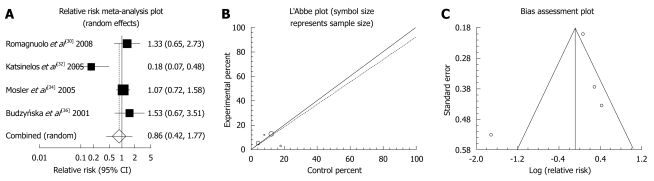

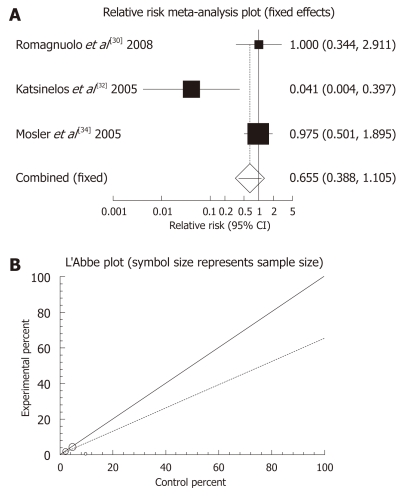

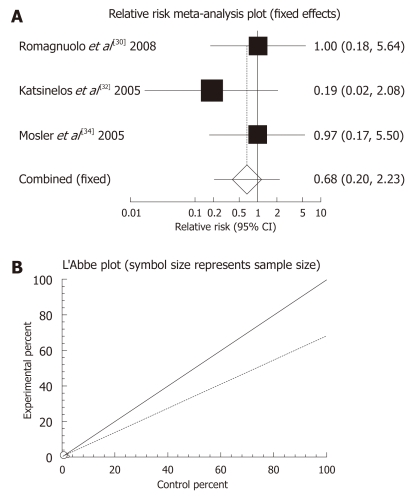

Allopurinol: There were four randomized clinical trials which used allopurinol orally before ERCP to prevent PEP (Table 3). These studies were meta-analyzed for their primary PEP outcome. The summary RR for “prevention of all kinds of pancreatitis” in the four trials[30,32,34,36] was 0.86 with a 95% CI of 0.42-1.77 and a non-significant RR (P = 0.6801, Figure 1A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies were heterogenous (P = 0.0062, Figure 1B) and could not be combined. Thus the random effect for individual and the summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response among allopurinol vs placebo therapy was -1.961983 (95% CI: -14.671469 to 10.747502, P = 0.5749), and Kendall’s test on standardized effect vs variance indicated tau = 0, P = 0.75 (Figure 1C). The summary RR for “prevention of mild pancreatitis” in three trials[30,32,36] was 1.08 with a 95% CI of 0.7-1.67, a non-significant RR (P = 0.7238, Figure 2A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies were homogenous (P = 0.2255, Figure 2B) and could be combined. Thus the fixed effect for individual and the summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response among allopurinol vs placebo therapy could not be calculated because of too few strata. The summary RR for “prevention of moderate pancreatitis” in the three trials[30,32,36] was 0.655 with a 95% CI of 0.388-1.105 and a non-significant RR (P = 0.113, Figure 3A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies were homogenous (P = 0.0614, Figure 3B) and could be combined. Thus the random effect for individual and the summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response among allopurinol vs placebo therapy could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Table 3.

Studies evaluating post-ERCP pancreatitis after allopurinol administration

Figure 1.

Individual and pooled relative risk (A), heterogeneity indicators (B), and publication bias indicators (C) for the outcome “prevention of all kinds of pancreatitis” in the studies considering allopurinol vs placebo therapy.

Figure 2.

Individual and pooled relative risk (A) and heterogeneity indicators (B) for the outcome “prevention of all kinds of pancreatitis” in the studies considering allopurinol vs placebo therapy.

Figure 3.

Individual and pooled relative risk (A) and heterogeneity indicators (B) for the outcome “prevention of moderate pancreatitis” in the studies considering allopurinol vs placebo therapy.

The summary RR for “prevention of severe pancreatitis” of allopurinol vs placebo therapy among the three trials[30,32,36] was 0.68 with a 95% CI of 0.2-2.23, indicating a non-significant RR for allopurinol administration (P = 0.5206, Figure 4A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies were not significantly heterogeneous (P = 0.6154, Figure 4B) and the fixed effects for individual and the summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for any adverse events among allopurinol vs placebo therapy could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Figure 4.

Individual and pooled relative risk (A) and heterogeneity indicators (B) for the outcome “prevention of severe pancreatitis” in the studies considering allopurinol vs placebo therapy.

Oxygen radicals play an essential role in the development of inflammation in various conditions[42-50]. The involvement of free radicals in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis has been shown in both animal and human studies[51]. Oxidative stress expedites mechanisms which lead to cell damage. It can directly destruct the cell membrane, accelerate lipid peroxidation, deplete cell reserves of antioxidants, and change signaling pathways inside the cells[52,53].

Although the pathophysiology of pancreatitis has been studied before, there is no specific therapy for this disastrous disease yet. Enteral or parenteral nutrition, antibiotic therapy, surgical procedures such as removal of abscess and necrosis, and cholecystectomy have been developed to treat AP[14]. In CP, pain management and probably surgical resection of pseudocysts are the goals of treatment. Because these treatments do not target the main problem and are recommended for symptoms and complications, investigators are still looking for new effective approaches in combination with current treatment.

Clinical studies of the evaluation of typical antioxidants on AP and CP were performed firstly at Manchester Royal Infirmary by Braganza and her colleagues. Two placebo controlled clinical trials[28,29] examining combined antioxidant therapy on recurrent CP showed a significant decrease in pain and an elevation in serum antioxidant biomarkers; however, in one study in which SAMe was examined as an antioxidant, alone or in combination with selenium and β-carotene, the results showed that SAMe was ineffective in patients with recurrent pancreatitis. Another two recently published clinical trials[4,16], particularly the latter study with a larger number of subjects (147), which used the same cocktail of antioxidants also showed pain reduction after administration. Therefore, the results of these studies show that such a combination of antioxidants could have a positive effect in the treatment of CP. However, we were unable to meta-analyze these three studies for pain as the primary outcome because pain reduction was assessed in a different way in each study. Except for the mentioned antioxidant cocktail, results of the administration of other antioxidants in both AP and CP clinical trials were incongruent and heterogeneous; and we cannot draw a definite conclusion on the efficacy of such therapy in the management of pancreatitis. We also evaluated the effect of etiology of pancreatitis including alcoholic, gallstone or idiopathic on the results of pain reduction and other outcomes, however, there was no relation between the cause of pancreatitis and clinical outcomes.

Furthermore, antioxidant therapy failed to prevent the onset of PEP in almost all trials (Table 2). Only one clinical trial in which 600 mg of allopurinol was administered twice before ERCP showed a significant decrease in the rate of PEP. However, our meta-analysis revealed that the RR for “prevention of mild, moderate and severe pancreatitis” of allopurinol vs placebo therapy was non-significant for allopurinol administration.

However, the present review indicates that there is insufficient data to support using antioxidants alone or in combination with conventional therapy in the management of AP, CP or PEP. Further double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with a larger sample size need to be conducted.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Peter Draganov, Division Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Florida, Gainesville, 1600 SW Archer Road, PO Box 100214, Florida 32610, United States

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Mofidi R, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ, Parks RW. An audit of the management of patients with acute pancreatitis against national standards of practice. Br J Surg. 2007;94:844–848. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman LS. Liver, biliary tract and pancreas. In: Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds , editors. Current medical diagnosis and treatment. 45th ed. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 693–701. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siow E. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition for acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Nurse. 2008;28:19–25, 27-31; quiz 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirk GR, White JS, McKie L, Stevenson M, Young I, Clements WD, Rowlands BJ. Combined antioxidant therapy reduces pain and improves quality of life in chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A review on the role of antioxidants in the management of diabetes and its complications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdollahi M, Ranjbar A, Shadnia S, Nikfar S, Rezaie A. Pesticides and oxidative stress: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:RA141–RA147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz HU, Niederau C, Klonowski-Stumpe H, Halangk W, Luthen R, Lippert H. Oxidative stress in acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2736–2750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenberg MH, Birk D, Beger HG. Oxidative stress in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:1306S–1314S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1306S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyan PM, Uden S, Braganza JM. Heightened free radical activity in pancreatitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90100-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziurkowska-Marek A, Marek TA, Nowak A, Kacperek-Hartleb T, Sierka E, Nowakowska-Duława E. The dynamics of the oxidant-antioxidant balance in the early phase of human acute biliary pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2004;4:215–222. doi: 10.1159/000078432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A, et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaffes AJ, Bourke MJ, Ding S, Alrubaie A, Kwan V, Williams SJ. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of transdermal glyceryl trinitrate in ERCP: effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moretó M, Zaballa M, Casado I, Merino O, Rueda M, Ramírez K, Urcelay R, Baranda A. Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A randomized double-blind trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:1–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung PS, Chan YC. Role of oxidative stress in pancreatic inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:135–165. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16:62–73. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00031-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhardwaj P, Garg PK, Maulik SK, Saraya A, Tandon RK, Acharya SK. A randomized controlled trial of antioxidant supplementation for pain relief in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:149–159.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue P, Deng LH, Xia Q, Zhang ZD, Hu WM, Yang XN, Song B, Huang ZW. Impact of alanyl-glutamine dipeptide on severe acute pancreatitis in early stage. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:474–478. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuentes-Orozco C, Cervantes-Guevara G, Muciño-Hernández I, López-Ortega A, Ambriz-González G, Gutiérrez-de-la-Rosa JL, Gómez-Herrera E, Hermosillo-Sandoval JM, González-Ojeda A. L-alanyl-L-glutamine-supplemented parenteral nutrition decreases infectious morbidity rate in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32:403–411. doi: 10.1177/0148607108319797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siriwardena AK, Mason JM, Balachandra S, Bagul A, Galloway S, Formela L, Hardman JG, Jamdar S. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of intravenous antioxidant (n-acetylcysteine, selenium, vitamin C) therapy in severe acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2007;56:1439–1444. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.115873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durgaprasad S, Pai CG, Vasanthkumar , Alvres JF, Namitha S. A pilot study of the antioxidant effect of curcumin in tropical pancreatitis. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du WD, Yuan ZR, Sun J, Tang JX, Cheng AQ, Shen DM, Huang CJ, Song XH, Yu XF, Zheng SB. Therapeutic efficacy of high-dose vitamin C on acute pancreatitis and its potential mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2565–2569. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ockenga J, Borchert K, Rifai K, Manns MP, Bischoff SC. Effect of glutamine-enriched total parenteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Nutr. 2002;21:409–416. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Beaux AC, O'Riordain MG, Ross JA, Jodozi L, Carter DC, Fearon KC. Glutamine-supplemented total parenteral nutrition reduces blood mononuclear cell interleukin-8 release in severe acute pancreatitis. Nutrition. 1998;14:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks PA, Hughes M, Ferrante M, Noordhoek EC, Ramagopal V, Slivka A. Does allopurinol reduce pain of chronic pancreatitis? Int J Pancreatol. 1997;22:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02788381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharer NM, Scott PD, Deardon DJ, Lee SH, Taylor PM, Braganza JM. Clinical trial of 24 hours' treatment with glutathione precursors in acute pancreatitis. Clin Drug Investig. 1995;10:147–157. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199510030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilton D, Schofield D, Mei G, Kay PM, Bottiglieri T, Braganza JM. Placebo-controlled trials of antioxidant therapy including S-adenosulmethionine in patients with recurrent non-gallstone pancreatitis. Drug Invest. 1994;8:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salim AS. Role of oxygen-derived free radical scavengers in the treatment of recurrent pain produced by chronic pancreatitis. A new approach. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1109–1114. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410330067010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uden S, Schofield D, Miller PF, Day JP, Bottiglier T, Braganza JM. Antioxidant therapy for recurrent pancreatitis: biochemical profiles in a placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992;6:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1992.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uden S, Bilton D, Nathan L, Hunt LP, Main C, Braganza JM. Antioxidant therapy for recurrent pancreatitis: placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:357–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romagnuolo J, Hilsden R, Sandha GS, Cole M, Bass S, May G, Love J, Bain VG, McKaigney J, Fedorak RN. Allopurinol to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:465–471; quiz 371. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milewski J, Rydzewska G, Degowska M, Kierzkiewicz M, Rydzewski A. N-acetylcysteine does not prevent post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography hyperamylasemia and acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3751–3755. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzis J, Christodoulou K, Paroutoglou G, Mimidis K, Beltsis A, Zavos C. High-dose allopurinol for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, Beltsis A, Mimidis K, Zavos C. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine does not prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosler P, Sherman S, Marks J, Watkins JL, Geenen JE, Jamidar P, Fogel EL, Lazzell-Pannell L, Temkit M, Tarnasky P, et al. Oral allopurinol does not prevent the frequency or the severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavy A, Karban A, Suissa A, Yassin K, Hermesh I, Ben-Amotz A. Natural beta-carotene for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2004;29:e45–e50. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Budzyńska A, Marek T, Nowak A, Kaczor R, Nowakowska-Dulawa E. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of prednisone and allopurinol in the prevention of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2001;33:766–772. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afshari M, Larijani B, Rezaie A, Mojtahedi A, Zamani MJ, Astanehi-Asghari F, Mostafalou S, Hosseinnezhad A, Heshmat R, Abdollahi M. Ineffectiveness of allopurinol in reduction of oxidative stress in diabetic patients; a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58:546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Das DK, Engelman RM, Clement R, Otani H, Prasad MR, Rao PS. Role of xanthine oxidase inhibitor as free radical scavenger: a novel mechanism of action of allopurinol and oxypurinol in myocardial salvage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;148:314–319. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De las Heras Castaño G, García de la Paz A, Fernández MD, Fernández Forcelledo JL. Use of antioxidants to treat pain in chronic pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2000;92:375–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagan VE, Tyurina YY. Recycling and redox cycling of phenolic antioxidants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;854:425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amoli MM, Mousavizadeh R, Sorouri R, Rahmani M, Larijani B. Curcumin inhibits in vitro MCP-1 release from mouse pancreatic islets. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3035–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mashayekhi F, Aghahoseini F, Rezaie A, Zamani MJ, Khorasani R, Abdollahi M. Alteration of cyclic nucleotides levels and oxidative stress in saliva of human subjects with periodontitis. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vakilian K, Ranjbar A, Zarganjfard A, Mortazavi M, Vosough-Ghanbari S, Mashaiee S, Abdollahi M. On the relation of oxidative stress in delivery mode in pregnant women; A toxicological concern. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2009;19:94–99. doi: 10.1080/15376510802232134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malekirad AA, Ranjbar A, Rahzani K, Kadkhodaee M, Rezaie A, Taghavi B, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress in operating room personnel: occupational exposure to anesthetic gases. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:597–601. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht565oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rezaie A, Parker RD, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: an epiphenomenon or the cause? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2015–2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranjbar A, Solhi H, Mashayekhi FJ, Susanabdi A, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress in acute human poisoning with organophosphorus insecticides; a case control study. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yousefzadeh G, Larijani B, Mohammadirad A, Heshmat R, Dehghan G, Rahimi R, Abdollahi M. Determination of oxidative stress status and concentration of TGF-beta 1 in the blood and saliva of osteoporotic subjects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1091:142–150. doi: 10.1196/annals.1378.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohseni Salehi Monfared SS, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. Islet transplantation and antioxidant management: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1153–1161. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jahanshahi G, Motavasel V, Rezaie A, Hashtroudi AA, Daryani NE, Abdollahi M. Alterations in antioxidant power and levels of epidermal growth factor and nitric oxide in saliva of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1752–1757. doi: 10.1007/s10620-004-9564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malekirad AA, Ranjbar A, Rahzani K, Pilehvarian AA, Rezaie A, Zamani MJ, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress in radiology staff. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanfey H, Sarr MG, Bulkley GB, Cameron JL. Oxygen-derived free radicals and acute pancreatitis: a review. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dröge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]