Abstract

We have developed a luminol-based assay using intact islets, which allows for quantification of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, an index capable of characterizing metabolic and mitochondrial integrity prior to transplantation was created based on the capacity of islets to respond to high glucose and rotenone (mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I inhibitor) by production of ROS.

To validate this assay, lipid peroxidation and antioxidative defense capacity were evaluated by detection of malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and glutathione peroxidase activity (GPx), respectively. Also, flow cytometric analyses of ROS (dihydroethidine), apoptosis (Annexin V, active caspases), necrosis (Topro3), and mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1) were done in parallel to correlate with changes in luminol-measured ROS. ATP/ADP ratios were quantified by HPLC and the predictive value of ROS measurement on islet functional potency was correlated with capacity to reverse diabetes in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic NOD.scid mouse model as well as in human transplant recipients. Our data demonstrate that levels of ROS in islets correlate with the percentage of apoptotic cells and their functional potency in vivo. The ROS indices following glucose and rotenone exposure are indicative of metabolic potency and mitochondrial integrity and can be used as surrogate markers to evaluate the quality of islets prior to transplantation.

Keywords: Islet, NOD.scid mouse, potency, quality control, ROS

Introduction

One of the most important variables in the success of pancreatic islet transplantation is the health and functional potency of the islets transplanted. However, accurate assessment of islet quality prior to transplantation to improve discrimination of preparations unsuitable for transplantation remains a challenge across the field. Increasing evidence supports the concept that oxidative stress, suffered as a result of ischemia and the islet isolation procedure, plays a pivotal role in islet cell damage and functional impairment, leading to poor function post-transplant (1–3). In fact, a significant loss of islet cell mass after transplantation is due to apoptosis and necrosis partially mediated by oxidative stress (4).

Oxidative stress is defined by excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) and deficient antioxidant systems (5). Oxidatively stressed cells are characterized by redox imbalance with accumulation of reduced pyridine nucleotides, depletion of ATP, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, cytochrome c release, and activation of apoptotic and necrotic pathways (3,6,7). In all aerobic cells, ROS are generated as byproducts of normal metabolic reactions (6). The primary source of ROS production is believed to be mitochondria (6). The physiological activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain leads to the production of ROS at complex I and III, and inhibition of the respiratory chain due to ischemia or by an inhibitor such as rotenone (complex I) increases the free radical level within the normal catalytic mechanism. As a result, ROS accumulate and the antioxidant defense systems may become overwhelmed, leading to cell dysfunction or death (8–12).

The objective of this study was to determine whether quantification of islet ROS would provide predictive information as to cell viability and function as a pretransplant quality control assessment. We evaluated the novel approach of a luminol-based chemiluminescence assay to quantify ROS from intact islets. Islet quality was further assessed by measurement of lipid peroxidation, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), adenine and pyridine nucleotides, and by flow cytometry for viability, apoptosis, and ROS. Islet functional potency was tested in vivo by transplantation into diabetic NOD.scid mice. Rat islets were used to establish the sensitivity and reproducibility of the luminol-based ROS assay under healthy and oxidatively stressed conditions. After validation of the method using rat islets, its predictive value as to the likely survival and function of human islets was evaluated by comparison with data from a diverse panel of in vitro assessments and transplant recipients.

Materials and Methods

Human islet isolation and culture

Human pancreata were obtained through the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Organ Procurement Organization with consent obtained for research from next of kin and authorization by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. Islets were isolated using a modification of the automated Ricordi method (13). Collagenase NB1, neutral protease (Serva Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany), and DNase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were infused into the main pancreatic duct. Islets were separated from exocrine tissue by centrifugation on a continuous Biocoll gradient (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) in a COBE 2991 cell processor (Lakewood, CO). For islet equivalent (IEQ) determination, islet samples were stained with dithizone (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) and sized using an eyepiece reticle and inverted microscope. Islets were cultured in CMRL 1066 (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) containing 2.5% human serum albumin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator prior to experimentation.

Rat islet isolation and culture

Rat islets were isolated from male Lewis rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) according to guidelines established by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were anesthetized by 3% isoflurane and digestion solution (Liberase RI, Roche) was injected in situ via the pancreatic common bile duct. Islets were purified by centrifugation on a discontinuous Ficoll gradient (Mediatech). Purified islets were cultured in CMRL 1066 containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator prior to experimentation. To induce oxidative stress and apoptosis, islets were cultured with cytokines (1000 U/mL TNFα, 1000 U/mL IFNγ, 50 U/mL IL1β; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) for 48 h.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

Total intact islet ROS levels were determined by luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence in a TopCount NXT® (Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT). Measurements were performed in the presence of 200 µM luminol and 250 µM of enhancer in 200 µL SOA-assay medium (LumiMax®, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). A minimum of 200 IEQ per sample was assayed either untreated or pre-treated with 16.7 mM or 28 mM glucose for 30 min to induce ROS. Pharmacologic induction of ROS was achieved by 30 min incubation with 1 µM rotenone (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.), an inhibitor of the mitochondrial complex I electron transfer chain (ETC). To confirm the ROS-specificity of the chemiluminescent signal, radical scavengers (superoxide dismutase [25 U], catalase [200 U]) were added and quenching of the signal was recorded. Data were normalized to islet DNA content (DNeasy, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and expressed as counts per minute (CPM) per µg of DNA. The fold increase of ROS after glucose (glucose index) or rotenone induction (rotenone index) was calculated by dividing the induced signal by the baseline level.

Quantification of lipid peroxidation

Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration in islet homogenates was measured spectrophotometrically according to manufacturers′ instructions (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Analysis of the protein concentration in islet extracts was performed with a modified Lowry method (14) and MDA concentrations were expressed relative to the total islet sample protein concentration.

Assessment of glutathione peroxidase activity

GPx activity in islet extracts was determined spectrophotometrically using Glutathione Peroxidase Cellular Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Results were normalized to protein content and expressed as mU per µg of protein.

Flow cytometry

Rat and human islets were dispersed into single cells and suspended in modified Krebs buffer (3.3 mM glucose and 0.25% bovine serum albumin). Islet cells were stained for detection of phosphatidyl serine translocation with Annexin V PE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and active caspases with VADFMK FITC (Promega, Madison, WI), and separately with JC-1 (Invitrogen) for detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). Dihydroethidine (Invitrogen) was added to separate samples to detect ROS and ToPro3 (marker of necrosis) (Invitrogen) was added to all samples just prior to data acquisition. Stained cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickenson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) LSRII flow cytometer. For data analysis, Flo Jo Software (Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR) was used.

Adenine and pyridine nucleotide quantification by HPLC

Total cellular extracts were prepared from purified islets according to a modified version of the phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol method described by Gellerich et al. (15) followed by a two-step ether extraction of residual phenol as suggested by Noack et al. (16).

A modified reverse phase HPLC method according to Noack et al. (16) with an ion pairing reagent according to Childs et al. was used for nucleotide separations (17). An HP1100 series quad pump HPLC and Discovery C-18 column (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) was used. Analysis of the chromatograms was performed using HP Chemstation computer software. Peaks were identified by co-elution with known chemical standards.

In vivo islet functional assessment

NOD.scid mice, purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA), were used as islet recipients following guidelines established by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Diabetes was induced by single intraperitoneal injection of 150 mg/kg streptozotocin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Glucose was measured daily using an Ascensia Elite glucometer (Bayer, Burr Ridge, IL). Mice were considered diabetic if non-fasting blood glucose (BG) was >350 mg/dL for three consecutive days. Mice were anesthetized by 2% isoflurane and islets were implanted underneath the kidney capsule. BG was measured for a total of 30 days after transplantation. An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed 25 days posttransplant. BG levels were recorded every 15 min up to 2 h postglucose injection (3 g/kg). Blood samples for insulin measurement were taken at times 0, 30, 60 and 120 min after glucose administration. Insulin secretion was assayed by ELISA (Crystal Chem Inc., Downers Grove, IL). The restoration and maintenance of normoglycemia due to islet graft function was proven by removal of the graft-bearing kidney.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Kidneys were formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin for morphological and immunohistochemical assessment. Serial sections (4 µm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and for insulin. The HIER method (Bio-Genex, San Ramon, CA) was used for antigen recovery of organs. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide, Sniper background blocking reagent (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) was used to prevent nonspecific binding. Slides were incubated with guinea pig anti-insulin (diluted 1:200; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) followed by peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-guinea pig IgG (diluted 1:400; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Chromogen diaminobenzidine was applied for visualization. The sections were counterstained with Harris′ hematoxylin. Samples processed without primary antibody served as negative controls.

Data analysis and statistics

All results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses for multiple comparisons were determined by nonparametric Mann-Whitney-U-test. Correlation analysis of data was performed using nonparametric correlation (Spearman) using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Statistical significance was established as a calculated p-value < 0.05.

Results

Detection of ROS from intact rat islets by luminol-based chemiluminescence

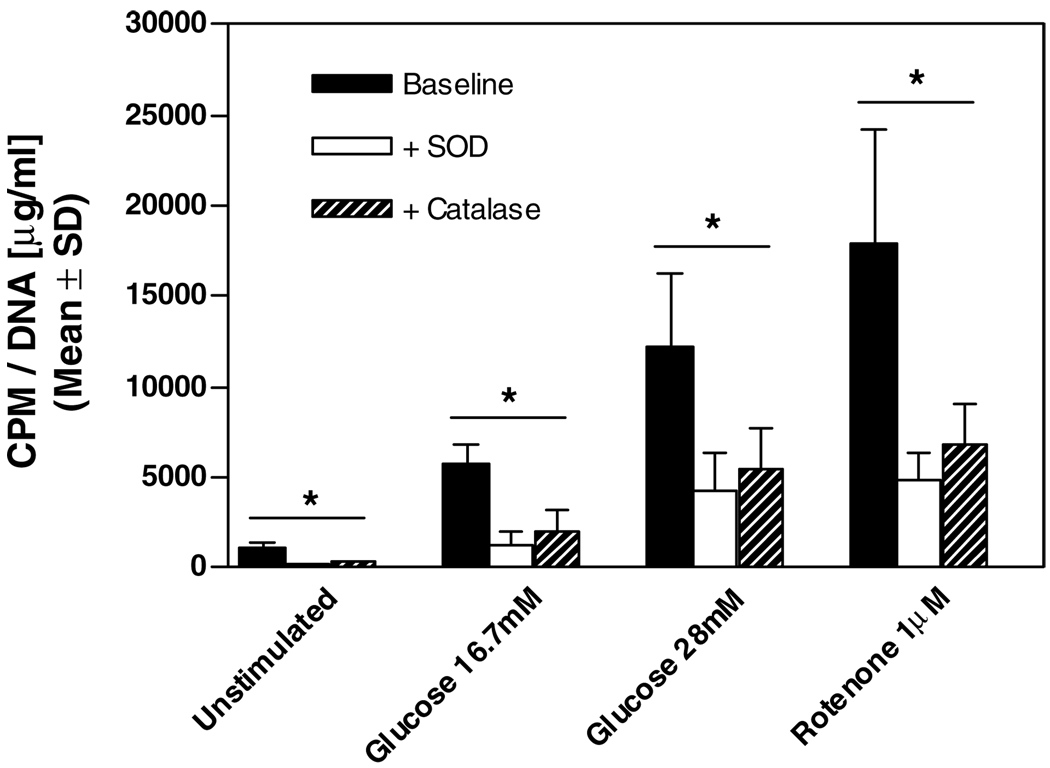

Because of the relatively homogenous organ source and standardized isolation method, rat islets provided a consistent model for the initial validation experiments. Rat islets were isolated by standard collagenase digestion and ficoll gradient centrifugation, cultured for 24 h, and assayed for ROS. To determine the sensitivity of the luminol-based method, rat islets were incubated with 16.7 and 28 mM glucose as a physiological stimulant for ROS production and with 1 µM rotenone (ETC complex 1inhibitor) to pharmacologically induce ROS. To demonstrate that the assay was in fact detecting a ROS-specific signal, we added separately the radical scavengers SOD and catalase and quantified the signal reduction. The mean ROS levels of rat islets cultured for 24 h were 1115 ± 271 CPM normalized to DNA content (n = 3) (Figure 1). Stimulation with glucose increased the ROS levels dose-dependently 5-fold at 16.7 mM and 11-fold at 28 mM, respectively. Inhibition of the mitochondrial ETC by rotenone amplified the signal by 16-fold. Addition of SOD and catalase reduced the detected ROS levels significantly (p < 0.05) in each assay group.

Figure 1. Quantification of ROS in rat islets by luminol-based chemiluminescence.

After 24 h culture rat islets were either untreated or pre-treated with 16.7 mM, 28 mM glucose or 1 µM rotenone. SOD and catalase were addedas controls. Results were expressed as counts per minute (CPM), normalized to DNA and represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05 vs. baseline.

Detection of cytokine-induced oxidative stress in rat islets

To determine whether the luminol-based ROS assay could detect increased ROS after treatment with known inducers of oxidative stress, rat islets were tested after culture with cytokines. The ROS levels measured for cytokine-treated rat islets were significantly increased (p < 0.001) for all of the assay conditions (basal, glucose and rotenone-induced ROS) compared to untreated islets (Table 1). In order to corroborate the findings of the ROS assay, rat islet extracts were simultaneously measured for lipid peroxidation (MDA) and GPx. Cytokine treatment of rat islets resulted in a 10-fold increase in MDA levels compared to untreated rat islets (p < 0.001). Quantification of GPx activity revealed a significant reduction after cytokine treatment (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of oxidative stress markers, viability, apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential in untreated and cytokine treated rat islets

| Untreated (n = 4) |

Cytokines (n = 4) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM/DNA | CPM/DNA | |||||

| (µg/mL) | Index | (µg/mL) | Index | p-value | ||

| Basal ROS | 1120 ± 221 | 6157 ± 1826 | <0.0001 | |||

| Glucose induced | [16.7 mM] | 5439 ± 995 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 9661 ± 2343 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| [28 mM] | 11583 ± 4004 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 15360 ± 5402 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Rotenone induced | [1 µM] | 17505 ± 5165 | 15.6 ± 1.5 | 16669 ± 6860 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | <0.0001 |

| nmol/mg protein | nmol/mg protein | |||||

| MDA | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 2.81 ± 0.6 | 0.0002 | |||

| mU/µg protein | mU/µg protein | |||||

| GPx activity | 8.4 ± 1.76 | 2.93 ± 0.7 | 0.0012 | |||

| % of all Islet cells | % of all Islet cells | |||||

| Viability | Topro3− | 71.7 ± 9.8 | 40.7 ± 15.0 | 0.014 | ||

| Apoptosis | Topro3− Annexin+ and/or | 11.2 ± 5.0 | 29.4 ± 7.3 | 0.006 | ||

| Mitochondrial | VADFMK+ | 77.7 ± 5.9 | 45.2 ± 9.1 | 0.001 | ||

| membrane | JC-1 | |||||

| potential | Red > Green | |||||

Rat islets were cultured for 48 h ± cytokines (TNFα, IFNγ , IL1β). Glucose and rotenone indices were calculated as induced ROS/basal ROS. Data represent the mean ± SD of four separate experiments.

Quantification of glucose- and rotenone-induced ROS levels

We have observed glucose- and rotenone-induced graduated ROS responses in rat islets that were proportional to the basal ROS levels. In order to allow direct comparison of ROS response between different islet preparations, we determined ′glucose and rotenone indices′, obtained using the following formula: induced ROS/basal ROS normalized to DNA content. Oxidatively stressed rat islets cultured with cytokines showed significantly reduced (p < 0.001) glucose and rotenone indices when compared to untreated islets (Table 1).

To determine the relevance of quantifying ROS levels as indicators of overall islet quality, flow cytometric assessments of viability, apoptosis and ΔΨm were conducted in parallel. Necrotic islet cells were identified by staining for membrane permeability (ToPro3) and apoptosis by phosphatidyl serine translocation (Annexin V) and activation of caspase enzymes (VADFMK). Characterization of ΔΨm was accomplished by staining with JC-1. As shown in Table 1, cytokine treatment significantly increased basal ROS levels, decreased glucose and rotenone indices, decreased viability, increased apoptosis and decreased the percentage of islet cells with normal mitochondrial membrane polarity (Table 1).

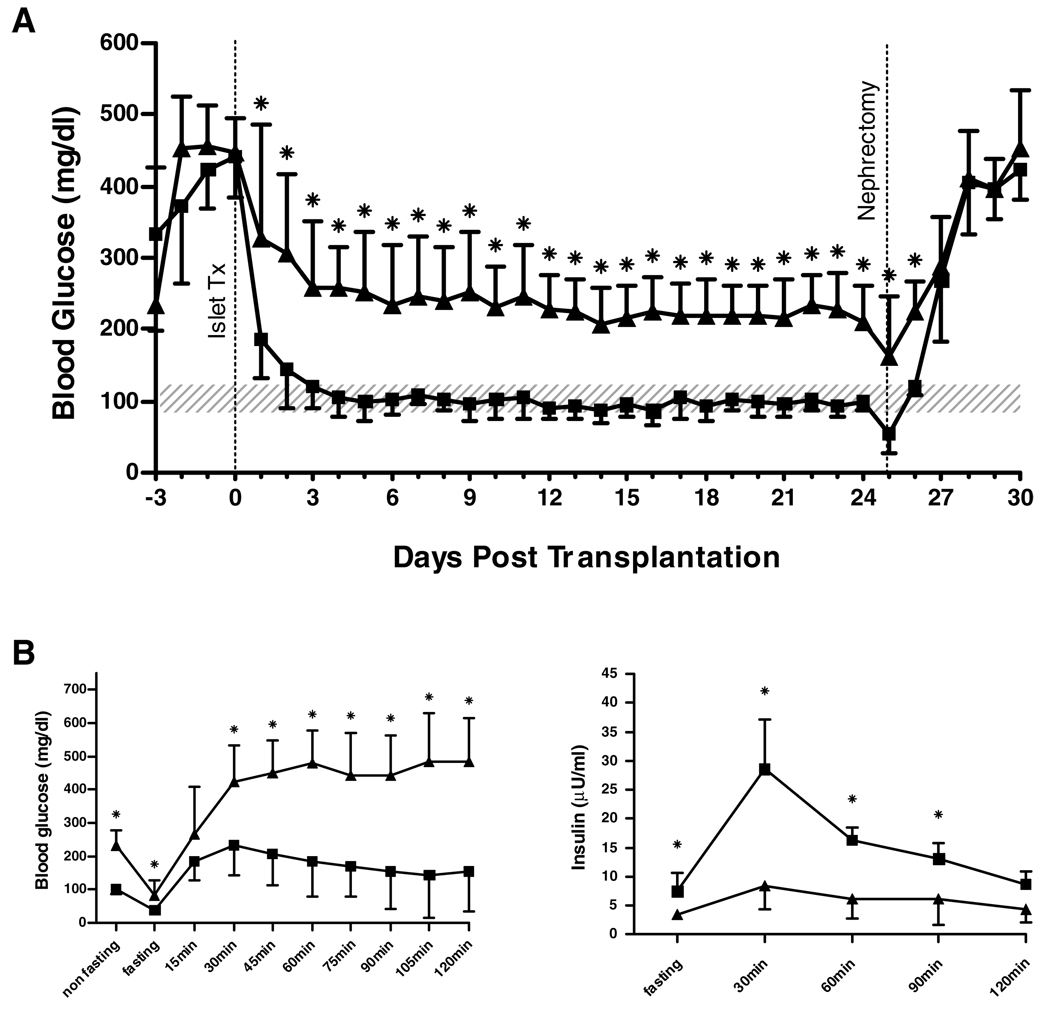

Assessment of islet in vivo functional potency

To evaluate the diagnostic value of the luminol-based ROS assay for predicting in vivo function, diabetic NOD.scid mice were transplanted with rat islets cultured ± cytokines. The minimal mass of transplanted islets allowing for cure was determined in titration studies (data not shown) as 500 IEQ. Transplantation of 500 untreated rat-IEQ resulted in stable reversal of diabetes and a normal IPGTT (Figure 2). An equal dose of cytokine-treated islets was not able to normalize BG levels long term, and the transplant recipients showed a diminished IPGTT (Figure 2). After removing the islet grafts by nephrectomy, all mice showed an immediate recurrence of hyperglycemia.

Figure 2. Function of rat islet grafts.

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic NOD.scid mice were transplanted with untreated (■) (n = 8) and cytokine treated (▲) (n = 8) rat islets (500 IEQ). IPGTT was performed by application of 3 g/kg glucose. After 25 days, islet grafts were removed by nephrectomy. (A) Non-fasting BG levels; *p < 0.05 vs. untreated. (B) IPGTT: BG levels (left); *p < 0.05 vs. untreated. Serum-insulin (right); *p < 0.05 vs. cytokine treated. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Shaded area indicates the physiologic range of BG (80–120 mg/dL).

Assessment of human islets for oxidative stress, metabolic state, viability and apoptosis

Having validated the ROS-assessments in rat islets, we sought to determine whether the luminol-based ROS assay could provide data as to human islet quality. Data from 18 human islet preparations were grouped based on their rotenone-index into ′high responders′ (rotenone index > 3.5; n = 6) and ′low responders′ (rotenone-index < 3.5; n = 12) (Table 2). Based on the data from rat islets, we hypothesized that high rotenone and glucose indices are markers for mitochondrial and metabolic integrity and sought to test this concept by parallel assessment of ROS (DHE), mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1), viability and apoptosis (Topro3, annexin V, VADFMK) using flow cytometry. In addition, MDA concentrations and GPx activities were determined.To discriminate islet cell metabolic state, pyridine and adenine nucleotide ratios were measured by HPLC.

Table 2.

Summary of metabolic assessments in human islets Oxidative stress

| Oxidative stress |

Basal metabolic state |

Viability and apoptosis |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS (CPM/) (DNA) |

DHE (%) |

MDA (nmol/ mg Prot.) |

GPx (mU/ µg Prot.) |

ATP/ ADP |

NADH/ NAD |

Rot. -Index. |

Gluc. -Index 16.7 mM |

28 mM | JC-1 (%) | Viability ToPro3− (%) |

Apoptosis Topro3− Annexin+ and/or VADFMK+ (%) |

|

| High responders (n = 6) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 1791.6 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 14.1 | 3.8 | 6.6 | 92.7 | 96.8 | 7.1 |

| SD | 1137.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 9.6 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| Low responders (n = 12) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 5785.3 | 25.0 | 7.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 51.8 | 91.2 | 17.8 |

| SD | 5805.1 | 16.2 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 21.5 | 10.2 | 18.1 |

| p-value | 0.083 | 0.167 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.048 | 0.797 | 0.679 |

Human islets were cultured for 24 h prior to experimentation. Preparations were grouped based upon their rotenone-index (RI > 3.5: ′high′, RI < 3.5: ′low′).

Compared to data acquired from rat islets, human islets showed on average higher baseline levels of ROS (mean ROS level rat: 1426±932 CMP/DNA; human: 4454±5093 CMP/DNA) and a reduced response to glucose- as well as rotenone-induction. A score of 3.5 with the rotenone index was set arbitrarily as a discriminator between high and low responders. Comparison of baseline ROS levels in high and low responders did not demonstrate different values (p = 0.08); however, the rotenone index levels in the high responders were significantly higher when compared to low responders (14.1 ± 9.6 vs. 2.3 ± 0.6; p = 0.002) (Table 2). Also, glucose index at 16.7 and 28 mM was significantly higher in the high responders when compared with low responders (3.8 ± 0.5 vs. 1.9 ± 0.6; p = 0.002 and 6.6 ± 2.5 vs. 2.2 ± 0.5; p = 0.007, respectively). MDA levels were significantly increased in low responding islets compared to high responders (7.3±5.2 vs. 1.9±1 nmol/mg protein; p = 0.006), while GPx activity was significantly reduced (3.1 ± 2.1 vs. 5.8 ± 1.3 mU/µg protein; p = 0.017).

The basal redox state of human islet preparations indicated by ATP/ADP and NADH/NAD ratios showed a significant increase in the reduced forms of pyridine nucleotides (1 ± 0.9 vs. 0.3 ± 0.3; p = 0.002) in the low responding islet preparations and a reduced ATP/ADP ratio (2.8 ± 1.1 vs. 4 ± 0.8; p = 0.019) compared to high responders (Table 2). In addition, flow cytometric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1) showed a decreased percentage of cells with normal mitochondrial polarity in low responsive islets (51.8 ± 21.5 vs. 92.7 ± 5.9%; p < 0.05). Regression analysis showed that the rotenone-index was significantly correlated with the percentage of islet cells with polarized mitochondria (r2 = 0.92, p = 0.001). Quantification of viability and apoptosis by flow cytometry showed great heterogeneity within the low responding islets but overall reduced viability and increased levels of apoptosis compared to high responding human islet preparations (Table 2).

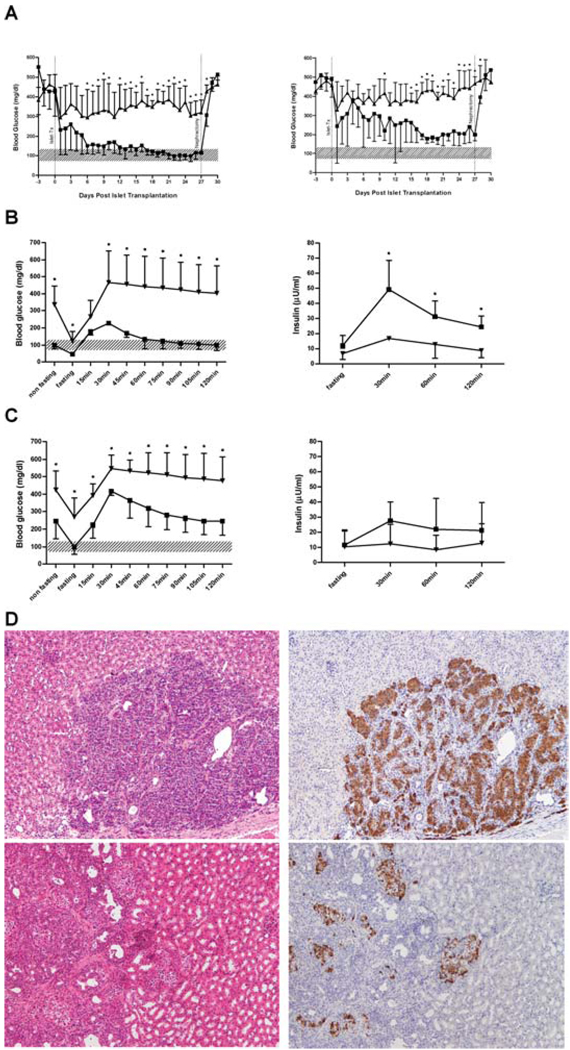

Determination of functional potency of human islets in vivo

In order to assess the relevance of increased oxidative stress measured by the luminol-based ROS assay and its correlation with functional potency in vivo, high and low responsive human islets were transplanted into NOD.scid mice. To establish the minimal mass of human islets necessary to reverse diabetes and allow for discrimination between potency of different islet preparations, decreasing doses from 1000 to 500 IEQ were injected. In contrast to rat islet grafts, a dose of 500 IEQ of human islets per mouse was insufficient to consistently reverse diabetes, and all transplanted animals showed impaired glucose tolerance (Figure 3). In our laboratory, a dose of 1000 IEQ of human islets met the requirements of diabetes reversal and allowed for discrimination between islet quality and was therefore determined as our minimal mass. Recipients of ′low responder′ human islets showed significantly impaired glucose control compared to high responding islets (Figure 3). During the IPGTT, only high responder grafts were able to normalize BG within a 2 h follow-up. Measurement of insulin content in mouse-serum supported the lack of insulin secretion in low responder grafts. As of the first day after nephrectomy, all mice showed an immediate increase in BG levels.

Figure 3. Function of human islet grafts.

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic NOD.scid mice were transplanted with high (■) (n = 5) and low (▲) (n = 5) responding human islets from four different islet preparations. IPGTT was performed by application of 3 g/kg glucose. After 25 days, islet grafts were removed by nephrectomy. (A) Non-fasting BG levels of recipients received 1000 (left) and 500 IEQ (right). *p < 0.05 vs. low responding islet grafts. (B) IPGTT, 1000 IEQ: BG levels (left); *p < 0.05 vs. high responding islet grafts. Seruminsulin (right); * p < 0.05 vs. low responding islet grafts. (C) IPGTT, 500 IEQ: BG levels (left); *p < 0.05 vs. high responding islet grafts. Seruminsulin (right); no significant difference between groups. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Shaded area indicates the physiologic range of BG (80–120 mg/dL). (D) Representative images of islet grafts (magnification 10×). Left: HE; grafts from high (top) and low (bottom) responding islets. Right: Immunohistochemistry for insulin (brown) from high (top) and low (bottom) responding islets.

Comparison of HE stained paraffin sections from removed kidneys containing high or low responding islets did not show major morphologic differences. However, insulin staining diverged distinctly between the groups. The observed functional capacity of high responder islet grafts was reflected in positive insulin staining in almost all of the examined islets. Conversely, low responding grafts showed only sporadic insulin staining (Figure 3D).

Discussion

A major impediment to improve the long-term outcome after islet transplantation is the lack of pretransplant assessments that adequately address islet quality and potency (18,19). The standard method of islet viability assessment prior to transplant is a membrane permeability test utilizing fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide and manual data acquisition by fluorescence microscopy (20,21). Another method that is widely used is in vitro glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. However, the limitations and inherent error of these methodologies indicate a critical need for the development of new technologies that provide for sensitive, accurate and reproducible diagnosis of islet quality before transplantation. The objective of this study was to develop an assay for quantification of oxidative stress in intact islets that can be easily accomplished prior to transplantation and predict islet potency in vivo.

Excessive oxidative stress leads to redox imbalance, activation of apoptotic pathways, and eventually, functional islet graft failure (8,21). The application of a luminol-based method of ROS detection on intact islets, which reflects reliably islet viability and function, is a novel tool. Furthermore, induction of ROS and calculation of the increase in ROS relative to basal provides information about mitochondrial integrity and metabolic state of the islets.

Rat islets were chosen as a primary explant tissue for validation of the ROS assay. We evaluated ROS levels after 24 h in culture to determine a baseline ROS in a ′healthy′ rat islet preparation. Treatment with cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IFNγ) served as a reproducible model of inducing oxidative stress and apoptosis (8,9,22–24) and was used to validate the sensitivity of the assay. We have demonstrated that the detected increase in basal ROS levels following cytokine treatment corresponded to an increased incidence of lipid peroxidation and reduced activity of GPx. Rat islets (±cytokines) were transplanted under the kidney capsule of diabetic NOD.scid mice. In our laboratory, the minimal mass of transplanted rat islets needed to reveal differences between treatment groups was 500 IEQ per recipient. This dose of rat islets with low baseline and high inducible ROS levels was sufficient not only to normalize nonfasting BG, but also to achieve a physiological response to glucose challenge after intraperitoneal administration. Grafts obtained from cytokine-treated islets with high ROS levels lowered nonfasting BG, but never to normal levels, and no glucose-stimulated insulin release was detected.

Compared to rat islets, human islets showed consistently higher baseline ROS levels and lower responses to glucose or rotenone induction. In addition, human islets showed a reduced functional potency as demonstrated by a minimal mass of 1000 IEQ of ′high responder′ islets necessary to reverse diabetes in mice, while the minimal mass for rat islets was determined to be 500 IEQ. We postulate that additional negative factors such as brain death with the characteristic inflammatory cytokine release, heterogeneity of the donor pool, prolonged ischemia time, hypoxia, and non-optimal isolation and culture conditions are responsible for this difference in oxidative stress between the two species.

Intracellular generation of ROS per se is a normal component of cell metabolism (25). In general, cells have numerous ROS defense systems and the source of oxidative stress is not the ROS production itself but persistent imbalance of ROS generation and detoxification. There is strong evidence that mitochondria are the major source of ROS generation, in particular the ETC (26–28). Our results confirm previous findings in which islet cells with an already existing redox imbalance (reflected by an increased NADH/NAD ratio) demonstrate high basal ROS levels, while the induction of ROS caused by the blockage of the mitochondrial ETC by rotenone induces minimal changes over baseline, suggesting significant mitochondrial dysfunction. Conversely, an increase in ROS levels following rotenone administration (′high responders′) requires a balanced mitochondrial redox state for the islets to be capable of mounting a significant response over baseline. Preparations that have high rotenoneindices and a high ROS-increase after exposure to glucose demonstrate higher viability and less apoptosis with high ATP/ADP ratio, supporting the hypothesis that the rotenone-index is a surrogate marker of mitochondria integrity.

β-cells are characterized by a highly sensitive system for initiating the response to physiological changes in extracellular glucose concentration. Increasing glucose concentrations stimulate glycolytic flux, followed by increased production of reducing equivalents (29). Glucose increases intracellular ROS, at least in part, as a result of increased generation of NADH and FADH2, which augments the production of superoxide by the ETC (30). Providing a balanced redox system, production of ROS is a physiological process in pancreatic β-cells, and indeed, ROS have been identified as signaling molecules in the context of insulin secretion (31). Therefore, the glucose index can serve as an indicator of intact β-cell responsiveness to glucose and functional potency of islets in vitro. Our results demonstrate that a high glucose index is indicative of a highly viable and potent islet preparation as confirmed by its capacity to reverse diabetes in diabetic mice.

We noted a significant correlation between mitochondrial membrane potential measured by flow cytometry (JC-1) and rotenone-index. This finding supports the concept that mitochondria are the major source of rotenoneinduced ROS. However, other sources of ROS production include xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450-based enzymes, NADPH oxidases, dysfunctional NO synthases, and infiltrating inflammatory cells, among others which the ROS index will be able to detect. Therefore, the measurement of ROS index in an intact islet represents an advantage over the measurement of the mitochondrial membrane potential on a single cell suspension as a tool to evaluate oxidative stress.

Interestingly, low baseline ROS levels did not always correspond to a pattern of high inducible ROS. Degree of viability and apoptosis significantly impact the capacity to respond to stimulation. An islet preparation with low viability and high percentage of apoptosis could demonstrate a low ROS baseline and a minimal response. Based on this observation, we can conclude not only that less oxidatively stressed islets, but also less viable tissue will have lower ROS. Thus, the developed indices are more indicative for islet health than baseline ROS.

A drawback of this method is the intrinsic ability of luminol plus any oxidizing agent to generate artifactual O2−(5,32). This may overestimate the total count per sample. However, our ROS assay was not designed to quantify the actual activity of oxygen radicals, but to allow for discrimination between islet preparations with low or high ROS levels based on calculated indices. It should also be emphasized that the assay is not capable of identifying the origin of detected ROS. Hydrogen peroxide crosses cell membranes readily (33). Hence, catalase, used to quench the luminol signal, can exert both intracellular and extracellular effects on H2O2 level (34). O2− does not generally cross cell membranes (5). Thus, the observed signal-quenching by SOD may be indicative of extracellular O2−. However, we demonstrated by trypan blue staining of islets prepared for ROS measurement that the detergent present in the assay buffer causes cell membrane permeability which should allow SOD to enter cells (data not shown). A major advantage of our ROS assay over single cell flow cytometry is the use of intact islets, minimizing preparation-related cell damage or metabolic disturbance.

Despite a somewhat limited dataset of 18 human islet preparations, we are compelled to justify the high number of ′low responders′ in our study. Certainly, the inclusion of research grade pancreata with marginal donor characteristics and prolonged ischemia time is a tentative valid explanation.

In summary, using a highly reproducible assessment system, we have found that oxidative stress is a major challenge in human islet preparations. ROS levels were found to correlate with viability and apoptosis. We have demonstrated that quantification of ROS-inducibility both by the physiological substrate glucose and the pharmacologic agent rotenone reveals mitochondrial integrity and metabolic state of intact islets and predicts islet potency in vivo. This method has also been translated to application on clinical grade pancreata intended for islet transplantation. Table 3 demonstrates the results of five isolations. Although the dataset is small, significant differences between average values for the transplanted preparations and the rejected preparation are apparent. Patients (n = 3) transplanted with grafts that scored high in the luminol-based assay (rotenone-index > 3.5, glucose-index > 2.5) showed excellent graft function with basal C-Peptide secretion in the range of 1.7 to 6.2 ng/mL 3 months after transplantation and a significantly improved overall metabolic control indicated by a decrease in HbA1C by 2.1 ± 1.0%. The average daily insulin requirement was reduced by 25.3 ± 13.0 units/day.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes of islet isolations evaluated using quality control assessments

| Quality control assessments1 | Transplanted preps (n = 4) | Rejected preps (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|

| Yield (IEQ) | 984,839 ± 236,063 | 390,000 |

| Purity | 87.5 ± 5.0 | 90.0 |

| Packed cell volume (mL) | 4.1 ± 1.0 | ND |

| Dose (IEQ/ kg patient body weight) | 12,678 ± 2563 | ND |

| Cellular integrity | ||

| Viability (fluorescent microscopy) | 91.5 ± 4.7 | ND |

| Viability (flow cytometry) | 84.6 ± 9.9 | 59.7 |

| Apoptosis (flow cytometry) | 11.9 ± 9.7 | 17.8 |

| Necrosis (flow cytometry) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 22.5 |

| Rotenone-index [1 µM] (luminol-based ROS) | 6.0 ± 3.1 | 2.3 |

| Glucose-index [16.7 mM] (luminol-based ROS) | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 1.1 |

| ATP/ADP (HPLC) | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 3.3 |

| Functional potency | ||

| GSIS (static incubation S.I.) | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 1.6 |

| Patient outcomes (3 months post-Tx) | ||

| Basal C-peptide secretion (ng/mL) | 3.8 ± 2.3 (1.7–6.2) | |

| Decrease in HbA1C (%) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | |

| Average reduction in daily insulin requirements (units/day) | 25.3 ± 13.0 | |

Quality control assessments were performed within 24 h post-isolation.

Data represent mean ± SD. GSIS, glucose stimulated insulin secretion; S.I., stimulation index; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin.

Validation of this new method will come from consistent application as a component of islet quality control assays prior to transplantation as well as a screening tool for potential improvements in islet processing techniques that minimize oxidative stress and facilitate mitochondrial and metabolic integrity.

In conclusion, quantification of stimulated ROS constitutes an important tool to evaluate islet potency prior to transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Debra Hullett, Jamie Sperger and Stefan Ludwig for critical review of this manuscript. Special thanks to Dr. Terry Oberley for important methodological suggestions and thoughtful criticism of our results. Special thanks also go to the Organ Procurement Organization at the University of Wisconsin for providing human pancreata for research. This study was supported in part by grants from the NIH (DK071218-01) and Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation (636383041).

Abbreviations

- BG

blood glucose

- CPM

counts per minute

- ΔΨm

mitochondrial membrane potential

- DHE

Dihydroethidine

- ETC

electron transfer chain

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- GSIS

glucose stimulated insulin secretion

- HbA1C

glycosylated hemoglobin

- HE

hematoxylineosin

- IEQ

islet equivalent

- IFN

interferon

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- IL

interleukin

- IPGTT

intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- NOD

non-obese diabetic

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- S.I.

stimulation index

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- UV

ultraviolet

References

- 1.Lakey JR, Burridge PW, Shapiro AM. Technical aspects of islet preparation and transplantation. Transplant Int. 2003;16:613–632. doi: 10.1007/s00147-003-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto M, Johansson U, Eich TM, et al. Key factors for human islet isolation and clinical transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1315–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paraskevas S, Maysinger D, Wang R, Duguid TP, Rosenberg L. Cell loss in isolated human islets occurs by apoptosis. Pancreas. 2000;20:270–276. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200004000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mysore TB, Shinkel TA, Collins J, et al. Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase with two isoforms of superoxide dismutase protects mouse islets from oxidative injury and improves islet graft function. Diabetes. 2005;54:2109–2116. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliwell B, Whiteman M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: How should you do it and what do the results mean? Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:231–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleury C, Mignotte B, Vayssiere JL. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cell death signaling. Biochimie. 2002;84:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano M, Matsumoto I, Sawada T, et al. Caspase-3 inhibitor prevents apoptosis of human islets immediately after isolation and improves islet graft function. Pancreas. 2004;29:104–109. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandrup-Poulsen T. Apoptotic signal transduction pathways in diabetes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00494-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandrup-Poulsen T. Beta cell death and protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1005:32–42. doi: 10.1196/annals.1288.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avila J, Barbaro B, Gangemi A, et al. Intra-ductal glutamine administration reduces oxidative injury during human pancreatic islet isolation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2830–2837. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Bertera S, Pietropaolo M, Trucco M, Piganelli JD. Preservation of human islet cell functional mass by anti-oxidative action of a novel SOD mimic compound. Diabetes. 2002;51:2561–2567. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Tse H, et al. Response of human islets to isolation stress and the effect of antioxidant treatment. Diabetes. 2004;53:2559–2568. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Finke EH, Olack BJ, Scharp DW. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 1988;37:413–420. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Smith RL. Lowry determination of protein in the presence of Triton X-100. Anal Biochem. 1975;63:414–417. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gellerich FN, Schlame M, Bohnensack R, Kunz W. Dynamic compartmentation of adenine nucleotides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space of rat-heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;890:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noack H, Kunz WS, Augustin W. Evaluation of a procedure for the simultaneous determination of oxidized and reduced pyridine nucleotides and adenylates in organic phenol extracts from mitochondria. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:162–165. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90222-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Childs KF, Ning XH, Bolling SF. Simultaneous detection of nucleotides, nucleosides and oxidative metabolites in myocardial biopsies. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1996;678:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bretzel RG, Alejandro R, Hering BJ, van Suylichem PT, Ricordi C. Clinical islet transplantation: Guidelines for islet quality control. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:388–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricordi C, Gray DW, Hering BJ, et al. Islet isolation assessment in man and large animals. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1990;27:185–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02581331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricordi C. Quantitative and qualitative standards for islet isolation assessment in humans and large mammals. Pancreas. 1991;6:242–244. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199103000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: A unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:599–622. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wachlin G, Augstein P, Schroder D, et al. IL-1beta, IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha increase vulnerability of pancreatic beta cells to autoimmune destruction. J Autoimmun. 2003;20:303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J, et al. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:452–461. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews CE, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Baust JJ, Strynadka K, Leiter EH, Rabinovitch A. Mechanisms underlying resistance of pancreatic islets from ALR/Lt mice to cytokine-induced destruction. J Immunol. 2005;175:1248–1256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skulachev VP. Role of uncoupled and non-coupled oxidations in maintenance of safely low levels of oxygen and its one-electron reductants. Q Rev Biophys. 1996;29:169–202. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552(Pt 2):335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadenbach B. Intrinsic and extrinsic uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1604:77–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy AN, Fiskum G, Beal MF. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration: Bioenergetic function in cell life and death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:231–245. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fridlyand LE, Philipson LH. Does the glucose-dependent insulin secretion mechanism itself cause oxidative stress in pancreatic beta-cells? Diabetes. 2004;53:1942–1948. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakai K, Matsumoto K, Nishikawa T, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species reduce insulin secretion by pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bindokas VP, Kuznetsov A, Sreenan S, Polonsky KS, Roe MW, Philipson LH. Visualizing superoxide production in normal and diabetic rat islets of Langerhans. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9796–9801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faulkner K, Fridovich I. Luminol and lucigenin as detectors for O2. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;15:447–451. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90044-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henzler T, Steudle E. Transport and metabolic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in Chara corallina: Model calculations and measurements with the pressure probe suggest transport of H(2)O(2) across water channels. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:2053–2566. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.353.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress in cell culture: An under-appreciated problem? FEBS Lett. 2003;540:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]