Abstract

This paper describes the targeted intervention component of GREAT Schools and Families. The intervention—GREAT Families—is composed of 15 weekly multiple family group meetings (e.g., 4–6 families per group) and addresses parenting practices (discipline, monitoring), family relationship characteristics (communication, support, cohesion), parental involvement and investment in their child's schooling, parent and school relationship building, and planning for the future. High-risk youth and their families—students identified by teachers as aggressive and socially influential among their peers—were targeted for inclusion in the intervention. The paper describes the theoretical model and development of the intervention. Approaches to recruitment, engagement, staff training, and sociocultural sensitivity in work with families in predominantly poor and challenging settings are described. The data being collected throughout the program will aid in examining the theoretical and program processes that can potentially mediate and moderate effects on families. This work can inform us about necessary approaches and procedures to engage and support families in efforts to reduce individual and school grade-level violence and aggression.

Introduction

As outlined in the overview paper in this supplement,1 the Multisite Violence Prevention Project was conceptualized and funded to increase knowledge on what reduces school violence among young adolescents. We relied on research on epidemiologic and developmental risk of aggression and violence, as well as prior findings from violence prevention studies, to guide decisions regarding design, program development, and implementation. Two sets of findings helped organize the final intervention and its design. The first related to the development of aggressive and violent behavior during early adolescence findings that (1) group norms that tolerate and even support aggression and violence in response to interpersonal conflict can increase the risk of violence among the overall population, and (2) there are a small number of youth—those commonly referred to as high-risk—who are responsible for a large proportion of adolescent violence.2 In response to these findings, two groups of intervention strategies have dominated the field: those strategies that focus on the whole school or population in changing norms related to aggression and violence and those that focus on high-risk youth, typically including multiple components and focused at multiple levels of risk. Although both types of interventions have been implemented across the country and each has demonstrably reduced aggression and violence, it is still unclear which approach is more effective in reducing school violence. Until this project, no study had compared the relative effect of each approach. Thus, the multisite project is designed to determine whether school violence is reduced more by implementing a general violence prevention program for all students in a given grade that changes norms that support aggression, or whether an intervention targeted to at-risk youth is more effective in lowering violence.

Previous papers have outlined the design and universal intervention implemented in this study. This paper describes the development and implementation of the intervention targeting high-risk youth—the GREAT (Guiding Responsibility and Expectations for Adolescents for Today and Tomorrow) Families Program. First, we define “high-risk” youth and the specific population targeted for this study. We then describe the theoretical model guiding the intervention and the development of the program. Finally, we outline the intervention and implementation procedures, including hiring and training of staff members and participant recruitment and retention.

Targeting High-Risk Youth

The focus on high-risk youth is based on the finding that a small minority of youth perpetrate the overwhelming majority of violence, both in and around school. Longitudinal surveys indicate that 20% of serious offenders account for between 75% and 90% of violent crimes.3,4 Reducing violence among this group, therefore, should significantly decrease the amount of violence in the school. The intent, however, was also to extend the reductions in aggression and violence beyond the specific high-risk students to other students, indirectly, by changing the beliefs and behavior of the high-risk students. For this reason, we chose to focus on students both who were considered at risk because of a pattern of aggressive and disruptive behavior in the school and classroom and who also wielded a relatively high level of influence on other students. Lowering aggressive behavior among influential students would, we believed, lessen support for violence and aggression among their peer groups.5

A Family-Focused Intervention

Numerous reviews have shown that family is the most immediate and influential social system for children's risk for aggression and violence.2,6–10 Because of the importance of family, many intervention studies have focused on improving parenting skills and family relationships to mitigate risk of violence and related behaviors.7,11 Results of such interventions suggest that they can have significant effects on aggression.12–19 There is also considerable evidence of the effectiveness of programs that focus on both parents and youth over those programs that focus solely on youth.20 Thus, it was clear that a family-focused intervention would likely be more effective in lowering aggression and violence than one that did not include the family.

Our intervention—GREAT Families—is composed of 15 weekly multiple family group meetings (e.g., 4–6 families per group) and addresses parenting practices (discipline, monitoring), family relationship characteristics (communication, support, cohesion), parental involvement and investment in their child's schooling, parent and school relationship building, and planning for the future. We chose multiple family groups because previous research suggested that they are efficient forms for service delivery, building social support among participants, and improving parent–child interactions directly.21,22 The families varied both across sites and within sites, although they shared some common characteristics (Table 1). Overall, the families were disproportionately poor. They represented a diversity of racial/ethnic backgrounds (although predominantly African American), family structures, and geographic locales. Some families reside in urban Midwest areas, whereas others reside in more rural southeastern settings. Even within a site, some families reside in more suburban neighborhoods, whereas others reside in urban neighborhoods. Implementing the multifamily program across these sites is a step toward examining the implementation and generalizability of this approach in widely varying settings and demands. Additional details of the program are described in a later section of this paper.

Table 1.

Description of participating families

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent/caregiver | ||

| Mother | 450 | 82 |

| Father | 29 | 5 |

| Stepparent | 6 | 1 |

| Foster parent | 5 | 1 |

| Grandparent | 41 | 8 |

| Aunt/uncle | 11 | 2 |

| Other | 6 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 198 | 36 |

| Married | 175 | 32 |

| Divorced | 61 | 11 |

| Separated | 51 | 11 |

| Cohabitating | 31 | 5 |

| Widowed | 24 | 4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American/Black | 387 | 83 |

| American Indian/Native American | 3 | 0.65 |

| European American/White | 60 | 13 |

| Hispanic/Latino (regardless of race) | 82 | 15 |

| Highest educational level completed | ||

| Some high school | 181 | 32 |

| High school graduate | 208 | 38 |

| Some post–high school | 93 | 17 |

| College graduate | 45 | 8 |

| Postgraduate education | 11 | 2 |

| Income ($) | ||

| Less than 10,000 | 131 | 25 |

| 10,000–19,999 | 141 | 26 |

| 20,000–29,999 | 93 | 17 |

| 30,000–39,999 | 69 | 13 |

| 40,000–49,999 | 34 | 6 |

| 50,000–59,999 | 19 | 4 |

| 60,000–69,999 | 14 | 3 |

| >70,000 | 34 | 6 |

Our approach builds on several prior prevention and intervention studies conducted by the investigators collaborating in the program. The same principles and multiple family group format, for example, were tested in the SAFE Children Program run by the University of Illinois, Chicago (UIC) team.23 Also, these approaches were used in the earlier 10-year Metropolitan Area Child Study (MACS).21 Quinn and colleagues24–27 of The University of Georgia team had developed a family intervention for youth involved with drug abuse and the juvenile court. They also developed a family–school intervention designed to work in schools with students who were experiencing personal or school problems.25 Investigators at Virginia Commonwealth University had implemented Project IMPACT, a substance abuse prevention program for families.28,29 Likewise, investigators at Duke had implemented parent training and family intervention with the Fast Track project.30–32 The collaborative team also included an investigator from the Early Alliance prevention trial that provided family support in addition to the peer, classroom, and reading-mentoring components.33 Each of these interventions builds on established principles that seek to improve monitoring and discipline practices. Each has also been extended to address ecologic and parental characteristics critical to successful parenting interventions. The GREAT Families combined aspects of each of these prior interventions.

Theoretical and Empirical Basis of the Intervention

The intervention uses concepts of psychoeducational, functional, sequential, and structural-strategic approaches to family intervention.34–38 It is grounded in “developmental-ecologic” theory39,40 and focuses on helping families manage child-rearing within the constraints and opportunities of their social contexts and on developing parenting practices that can reduce antisocial behavior.41,42 The developmental–ecologic model of child and family functioning assumes that (1) the family serves as the primary support and socializing force for children; (2) the challenges families face and often the ways they attempt to address them depend on the age of the children; (3) children and families live in communities and are also influenced by larger social, cultural, and policy realities; and (4) strengthening families and family-focused interventions are among the more powerful ways to effect positive child outcomes and prevent violent and antisocial behavior.

A major tenet of developmental–ecologic theory is that individual development is influenced by the qualities of the social systems in which the family lives or participates.10,41,43,44 Individual development is nested within a series of social structures,43,45 beginning with family and peer systems, and, in turn, families and peers are nested within larger social contexts, such as schools and neighborhoods. Potential risk factors include not only individual child behavioral problems but also potential problems in family functioning and increased risk owing to social settings. However, there are also strengths of the individual child, family, and social setting that could bolster youth and families. Thus, this intervention focuses not only on risk but also on current and potential assets and strengths in the family, peer, school, and neighborhood settings and the interactions among these social contexts.

Developmental–ecologic theory also considers the effect of these systems across youth development. On the basis of prior work on developmental trajectories in violence and aggression,3,4,46,47 the goal of the GREAT Families intervention is to interrupt a progression from early, socially unacceptable behavior to serious delinquency and violence by eliminating the function of problem behaviors in families and the reinforcers of such behavior. The idea of developmental ecology also attends to multiple risk and protective factors in the lives of young people and potential changes in the relative influence of family, peers, and neighborhoods as young people grow and mature. Whereas parents are among the earliest influences on children, as children grow and develop, school, peers, and community become increasingly important influences.3

Overlaying developmental–ecologic theory is the importance of context, which includes the interaction of race, ethnicity, and social status of the individual with the prevailing group cultural norms and those of the larger social–cultural systems.48,49 Research has found that some parenting practices are more uniquely effective among particular racial/ethnic groups. For example, for Asian-American and African-American parents, stricter and more parent-directed approaches, approaches referred to as more “authoritarian,” are linked to positive child and adolescent adjustment, whereas these practices are linked to more negative outcomes among European American children and youth.21,50–53 Understanding parenting approaches across and within particular racial/ethnic contexts has very important implications for future prevention efforts.

We integrate six core elements into the program based on empirical data regarding their relation to risk of antisocial behavior and violence, as well as their theoretical and clinical significance to family functioning. These elements include (1) promoting home–school partnerships26,54,55; (2) enhancing parental monitoring and supervision7; (3) promoting care and respect through discipline and rules21; (4) increasing parent and child coping, self-control, and management skills28; (5) developing healthy, respectful, and effective family communication and problem-solving skills56; and (6) planning for the future.31

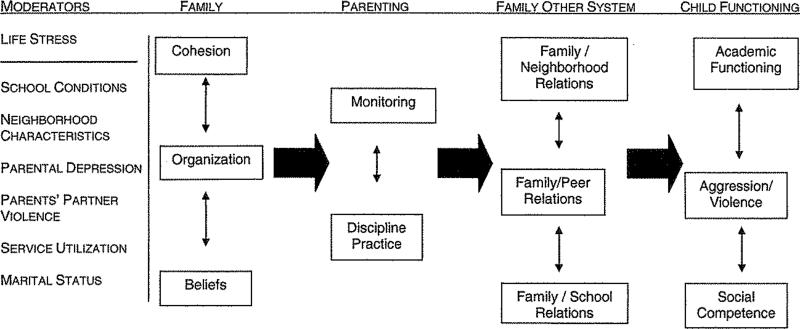

We use the six elements to express the intent and to guide the activities in the intervention. Sometimes a given step is addressed specifically and separately. However, because all are seen as aspects of family life, more than one element may be the focus of an activity or session. To have an effect on family functioning and child behavior, the intervention should encompass all of these aspects of the family (Figure 1). The goals of the intervention according to the six elements include helping families to:

develop and maintain an organizational structure conducive to their children's social, academic, and vocational success;

improve or maintain positive aspects of parenting and family relationship characteristics that have been empirically linked to decreased risk of antisocial behavior (such as consistent rules and discipline, adequate monitoring, emotional cohesion, clear communication, as well as applying problem-solving skills to achieve goals);

marshal interpersonal resources that are likely to protect families from stressful environmental influences and meet developmental and social–ecologic challenges;

use strengths to manage family members’ needs and challenges; and

develop networks of support to aid in understanding and managing their children and any developmental and environmental challenges.

Figure 1.

Aspects of family life.

The GREAT Families Program

The GREAT Families Program is composed of 15 weekly 2-hour sessions with groups of approximately four to six families. The program covers each of the six elements in two to three sessions. Topics of the family sessions include establishing family rules and roles, home and school partnerships, communication within and outside the family, handling emotions and anger, choosing friends, finding support, and connecting to the community. All family members are invited to attend these meetings—all caregivers (including grandparents, aunts, and uncles) and all children. The focus is on caregivers living in the home, but caregivers living outside the home but heavily involved in caretaking (e.g., grandmothers) are also invited. Child care is provided for children younger than age 5. Families are offered transportation to sessions as needed. The Duke site, for example, offered a van service to transport families to and from each session. At UIC, families were often able to walk to sessions, which were held in their neighborhood. In rare cases, we provided a cab or other car service to a family. Families are paid for each session attended, with slightly increasing amounts paid over the course of the intervention ($10 for sessions 1–5, $15 for sessions 6–10, $25 for sessions 11–15). We also provide food, often dinner, during each session.

Each session had the same basic format, including a review of the previous week's homework assignment, discussion around a focused topic, in-session role-plays and activities, and assignment of homework. This format serves three primary functions.

Behavioral practice and skill use. Each session offers opportunities for families to practice, or observe others practicing, family skills and effective modes of interaction. This activity is seen as the primary vehicle for promoting needed family skills and builds from the other two functions.

Education. By helping families understand “risk factors” for antisocial and problem behavior, the group leader encourages the recognition of family strengths and the need to change problematic patterns of family interaction.

Social support. By facilitating family group coherence and an atmosphere of mutual interest and concern, the group leader helps to provide families with a source of social support and the opportunity to make normative social comparisons.

In addition to the work completed in sessions, families are given specific tasks to work on and practice at home. Each task is intended to do the following:

Help families practice what they have learned and to work toward independent responsibility for addressing family issues.

Provide a sense of continuity between what happens in the group meetings and what happens at home. This continuity is important if families are to believe that what they learn in each session has relevance to their everyday lives.

Maintain an awareness of session activities and related family needs throughout the week.

Home and School Partnership Plan

In addition to the focus on family functioning, the family intervention focuses on building and supporting family–school relationships. Thus, we incorporated the Home–School Communication Plan (HSCP), which is similar to the Daily Report Card Programs,57 into the program. This part of the intervention promotes regular communication between the child's teacher(s) and parents, focused particularly on the child's progress and success in achieving important academic and behavioral goals at school. The program provides a uniform set of academic and behavioral goals for each student to work on during the school year. These goals are (1) talking to teachers with respect, (2) behaving respectfully with peers, and (3) completing assigned work. Families are asked to identify teachers to help them monitor their child's progress and success in achieving these goals. The teacher is asked to complete a daily goal sheet, indicating whether the child has succeeded in meeting the goals. The goal sheet with the daily teacher report is sent home at the end of the week for parents to review. Families are asked to bring their child's goal sheet to the group meetings for a brief review and discussion. The primary purpose of this part of the intervention is to increase and support regular communication between the family and school regarding the child's behavior.

Staff Recruitment, Training, and Supervision

Groups are led by a single family group leader. The role of the family group leader is critical to the success of the program. We use the term family group leader, not therapist, to highlight the prevention orientation of the intervention. In addition, a child care worker is assigned to each group to provide care for children younger than age 5. Although families are welcome to bring young children to the session, the format of the sessions and activities are not necessarily designed for young children. Childcare affords families with young children the opportunity to attend sessions and focus on activities with their school-aged children.

Characteristics of group leaders

Family group leaders have had prior experience in family intervention and experience working with the populations at each site. Most have a master's degree in psychology, social work, public health, or a related field and have had formal training in family systems theory. A priority is to match families and group leaders by race or ethnic background, although this match was not always possible. In Chicago, approximately half of the participating families spoke only Spanish, so it was necessary to hire Spanish-speaking leaders.

Tasks of the family group leader

An initial task for the family group leader is to help families feel understood and respected so that they can employ strengths and use information effectively to reduce their children's risk. Without such respect, families are unlikely to continue to participate in the program. Thus, in addition to providing information that is useful to families, the group leader must also provide the family with emotional support, empathy, and concern. Further, the group leader works to bolster and recognize each family member's competence and sense of self-worth. By highlighting a family member's strengths, behaving in a respectful manner, and helping that person define his or her goals, the group leader is able to motivate the family's investment in the tasks. Beyond establishing a warm bond with the family, the group leader must possess the necessary technical skills to help family members develop new problem-solving skills and to enhance existing skills. The family group leader takes an active, direct approach in helping the family to work on solvable problems. Specific ways that the group leader provides practical help to families are:

by helping families work on the critical aspects of family functioning;

by establishing a relational focus to help families see the broad, systemic nature of their difficulties and thus lessen blaming;

by demonstrating how the positive relabeling of problems can help families approach problems from a fresh perspective;

by encouraging and showing families how to practice new behavioral patterns both in the session and at home;

by helping families to develop skills that enable them to deal more effectively with the community, especially the school system; and

by facilitating group cohesion (among families participating in the intervention program) and an atmosphere of mutual interest and concern to provide each family with a source of social support that will continue after the formal meetings are finished.

Training and supervision of group leaders

The investigators and program coordinators at each site participate in a “train the trainer's meeting” and then provide training to the group leaders at their site. Group leaders receive approximately 20 hours of training. Training includes lectures and readings in risk and prevention of aggression and violence, family systems and developmental-ecologic models, prevention (as distinct from treatment), issues of treatment fidelity, and group process. It also includes an exploration of their own racial-ethnic-social backgrounds and the implications for their work with diverse children and families.58 Training emphasizes conceptual understanding, skill practice, and clinical preparation. Leaders also receive 1 hour of individual supervision per week and attend a weekly staff meeting. The goal is to ensure quality service delivery and standardization across leaders. In each weekly group supervision session, members review the goals of each program session to ensure that program leaders are working on the same tasks and approaching common issues in a similar manner. Coordinators also observe family sessions for training and to ensure fidelity to the program. Weekly conference calls among the coordinators and investigators facilitate cross-site consistency in program implementation.

Although manualized, the intervention is not scripted nor are family members merely taught skills. Therefore, supervision focuses on helping to maintain consistency in activities, goals, and intervention strategies rather than specific presentations. The program uses self-ratings and supervisor ratings of group leaders’ session management to assess fidelity and to guide supervision. Increased supervision accompanies any indication of inadequate adherence.

Selecting, Recruiting, and Engaging Families

Selecting Families

We selected specific youth for the targeted intervention on the basis of teacher nominations. Teachers are asked to nominate students on the basis of two criteria: a history of aggressive and disruptive behavior in the classroom, and the student's relative level of influence on other students. In the fall of each year (5 or 6 weeks into the school year), teachers are asked to complete nomination forms. Specifically, they are asked to read a list of behaviors (encourages other students to fight, frequently intimidates other students, has a short fuse/gets angry very easily, gets into frequent physical fightsa) and to list students in their classroom who exhibit the behaviors most often, On the basis of that list, teachers are asked to rate each student on their level of influence using a five-point scale with 1 being “not influential at all” and 5 being “very influential.” We choose students with the highest influence rating for participation (with a score of 3 or higher as the cutoff).

Recruitment

In addition to securing agreement to participate in the intervention, the recruitment and consent process was important because it was the initial phase of the engagement process. This phase of the program set the stage for families to make a commitment to participate and begin to frame the program as being supportive of them and their child's performance in school, in peer relations, and in other aspects of their life.

There were several steps in the recruitment process. First, we sent families a letter outlining the program. Soon after letters were sent (within 3–4 days), the group leaders followed up by telephone or with a home visit. Multiple phone calls or home visits were very likely for many families. Group leaders received extensive training on recruitment and followed a basic “script” as approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and individual sites. Although it was essential that the basic information outlined in the script be followed and presented in the order approved, group leaders were encouraged to use their individual style, with a focus on developing a comfortable and supportive relationship with families.

During attempts to engage the family either by telephone or during a home visit, group leaders were trained to keep the following key issues in mind.

Begin contact with the parents by helping them to identify the program as one that will be helpful to their child's school performance and functioning with other children.

Realize that, although a primary goal is to establish rapport with the caregiver, all family members should be encouraged to participate. (If one parent describes the other as unwilling to participate, group leaders should problem solve around how to address this issue by, for example, offering to talk with the other parent directly, having the willing parent discuss the program with his or her partner, or sending written information directly to the other parent.)

Recognize immediately that the 15-week time commitment might prove difficult to secure. Group leaders should emphasize their willingness to help families attend the sessions regularly and work with the family to address any barriers to participation along the way.

Engaging Families in the Intervention Program

Engaging and keeping families in the intervention program is one of the most challenging aspects in prevention interventions.29,59,60 To confidently evaluate program effects requires that a large proportion of those families solicited participate. in addition, families may differ in perceived need or in their perception of the value of the intervention activities. Because they may not believe their child has problems with the behaviors targeted and because they have not sought intervention themselves, they may not see the immediate value of spending time in such activities. In addition, many families with at-risk youth, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, may justifiably mistrust social service or educational institutions and professionals. They may be suspicious about the reason for interest in the family and whether the requests to participate are trustworthy; in other words, that it is not just another misleading, condescending, or insensitive request. Even among families interested in participating, other demands may compete for their time and energy.

Nonetheless, it is critical to engage families and help them stay engaged. In some cases, numerous phone calls or home visits with a family before and even after attending the initial meeting are necessary to keep families engaged. Cancellations and missed initial appointments and early group meetings, although common, should not be considered indications that families are uninterested or will not eventually participate more fully. A study to identify patterns of involvement in a similar family-focused preventive intervention identified two different patterns among participating families.59 One group of families was immediately responsive, enthusiastic, and participated fully in the intervention. Recruitment was relatively straightforward and families attended regularly. A second group of families attended the intervention fully, but only after extensive effort to recruit and retain them in the intervention. As in that study, in our program, approximately half of all participating families responded enthusiastically to the initial invitation. They immediately understood the nature of the program and attended regularly. The other half required much more time and effort to recruit, with approximately 30 of these families requiring extra support to stay in the program after starting. However, once engaged in GREAT Families, the initially reluctant families attended fully and participated with enthusiasm. The importance of persistence and working with families to problem solve around barriers to participation cannot be underestimated.

The experience and skill of the group leader are critical to family participation in the program. Families are more likely to stay engaged when group leaders (1) are assertive, positive, and empathic when contacting families and easily accessible after contact, (2) directly address barriers to participation, (3) can frame difficulties as understandable but also expect families to participate fully in the program, (4) stay focused on the practical in resolving participation dilemmas, and (5) foster a collaborative, mutually respectful atmosphere.

All families have the option to decline to participate. However, it is the job of the family group leader to ensure that issues and barriers are addressed and removed if possible. In the GREAT Families Program, this task often required careful review of the family's needs and appropriate strategies to address family concerns. For example, some families were offered initial sessions in the home or individually to help them see the value of the program. In addition, make-up sessions were offered for some families. When a family missed a session, immediate follow-up was put in place to help minimize dropout. Throughout the process, a primary task of the group leader is to help families feel understood and respected so that they can employ strengths and use information to reduce their children's risk. Without these elements, families are unlikely to continue to participate in the program.

Sensitivity to Family Diversity in Prevention Programming

The GREAT Families Program includes families from diverse racial, ethnic, social, geographic, and cultural backgrounds. The project screens staff members for their experience and sensitivity in dealing with families similar to participants. It is critical for potential staff members to demonstrate their ability to recognize and discuss ways that cultural backgrounds relate to their own and the participants’ values and beliefs about families and to perceptions about the program.

Once hired, staff members participate in training conducted by the project to help them further explore their own ability to interact effectively with families. They also discuss background readings about family functioning and prevention approaches with African-American and Latino families.10,53,61–64 These discussions are an important part of training, supervision, and the intervention. To supplement the reading materials, we conduct exercises during training in which group leaders are asked to reflect on how they might be perceived by families (i.e., aspects of their presentation and style that may help or hinder program participation) and to role-play a variety of scenarios to help staff members practice and feel comfortable in handling the many ways that families may raise issues of race and culture (i.e., accusations that the school personnel are racist, not engaging in practices because they conflict with their religious teachings or cultural values about families). The exploration of cultural issues presents a potentially valuable activity for group leaders. In addition, the program integrates a Cultural Considerations Section into the sessions to help the group leaders think about the ways that race, culture, and social status might interact with the material in the manuals during the family sessions. This section might include thinking about gender and family roles in Latino families or views of institutions and racism among African-American families. Group leaders who are conscious of these influences will be better equipped to help families find effective, realistic, and culturally consonant ways of handling challenges. It will also help facilitate for families the distinction of cultural practices that represent strength and health promotion from those that are problematic. In turn, group leaders will be better equipped to foster problem resolution and to recognize potential areas of strength and protective factors that they can help promote among families.

Summary

The GREAT Families Program is designed to bolster the family to interact more positively in various environments in an effort to improve youth behavioral and academic outcomes. The program stresses the sociocultural contexts in which families, youth, peers, and schools develop. The family program has already been pilot tested and is being implemented with two successive year cohorts of youth and families in the four collaborating sites. Future work will examine data from this portion of the GREAT Families Program in an effort to share what we have learned about approaches and efforts to promote positive outcomes for children and families.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully appreciate the valuable, diligent, and persistent efforts of the site-based coordinators Claire Hyman (Duke University), Alice Virgil (University of Illinois at Chicago), Lori Durham-Reaves (University of Georgia, Athens), and Cheryl Groce-Wright (Virginia Commonwealth University) and their contributions in developing and implementing this program. We would also like to acknowledge the innumerable parents, youth, teachers, principals, and school personnel and other staff members without whom this work would not have been possible.

This study was fund by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Cooperative Agreements U81/CCU417759 (Duke University), U81/CCU517816 (University of Chicago, Illinois), U81/CCU417778 (The University of Georgia), and U81/CCU317633 (Virginia Commonwealth University).

Footnotes

In Year 2, “relationally aggressive behaviors, i.e. deliberately excludes other students from peer activities, and is verbally abusive,” were added the list.

References

- 1.Multisite Violence Prevention Project The Multisite Violence Prevenrtion Project: background and overview. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(suppl):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeber R, Farrington DP. Strategies and yields of longitudinal studies on antisocial behavior. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser DJD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. John Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 125–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard S. Multiple-problem youth: delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeber R, Wei E, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Huizanga D, Thomnberry TP. Behavioral antecedents to serious and violent offending: joint analyses from the Denver Youth Survey, Pittsburgh Youthi Study and the Rochester Youth Development Study. Stud Grim Crim Prev. 1999;8:245–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller-Johnson S, Costanzo PR, Coie JD, Rose MR, Browne DC, Johnson C. Peer social structure and risk-taking behaviors among African American Early Adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2003;32:375–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCord J. Family relationships, juvenile delinquency, and adult criminality. Criminology. 1991;29:297–417. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. A social interactional approach: antisocial boys. Vol. 4. Castalia; Eugene OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Dev. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parke RD, Kellam SG, editors. Exploring family relationships with other social contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Families and the development of urban children. In: Reyes O, Wlabergk HJ, Weissberg RP, editors. Interdisciplinary perspectives on children and youth. Sage; Newbury Park CA: 1997. pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolan P, Guerra N. What works in reducing adolescent violence: an empirical review of the field. Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence; Boulder CO: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander JF, Robbins MS, Sexton TL. Family-based interventions with older, at-risk youth: from promise to proof to practice. J Prim Prev. 2000;21:185–205. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson WS, II, Redner R, Andur RL, Mitchell CM. The case of diversion from the justice system. Plenum Press; New York: 1994. Alternative treatments for troubled youth. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunninghbam P. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Guilford; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sexton TL, Alexander JF. Family-based empirically supported interventions. Couns Psychol. 2002;30:238–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:627–42. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ialongo N, Poduska J, Werthamer L, Kellam S. The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. J Emotional Behav Disord. 2001;9:146–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoolmiller M, Eddy JM, Reid JB. Detecting and describing preventive intervention effects in universal school-based randomized trials targeting delinquent and violent behaviors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:296–306. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolan P, Hanish L, McKay M, Dickey M. Evaluating process in child and family interventions: aggression prevention as an example. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16:220–36. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrington DP, Welsh BC. Value for money? A review of the costs and benefits of situational crime prevention. Br J Crim. 1999;39:345–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolan PH, McKay M. Preventing aggression in urban children: an empirically based family prevention program. Fam Relations J Appl Fam Child Stud. 1996;45:148–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster-Stratton C. Randomized trial of two parent education programs for families with conduct-disordered children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:666–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry D, Quintana E, Lutovsky K. The SAFE Children Prevention Program. In: Tolan P, Szapocnik J, Sombrano S, editors. Developmental approaches to prevention of substance abuse and related problems. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: In press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joanning H, Quinn WH, Thomas FN, Mullen R. Treating adolescent drug abuse: a comparison of family systems therapy group therapy, and family drug education. J Marital Fam Ther. 1992;18:345–56. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn WH, Michaels M, Sutphen R, Gale J. Juvenile first offenders: characteristics of at-risk families and strategies for intervention. J Addict Offender Couns. 1994;5:2–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn WH. Expanding the focus of intervention: the importance of family community relations. In: Adams P, Nelson K, editors. Reinventing human services: community and family centered practice. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1995. pp. 245–59. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn WI, Bell K, Ward J. The Family Solutions Program for juvenile first offenders. Prev Res. 1997;4:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCreary M, Belgrave FZ, Allison KW. Project IMPACT: a substance abuse prevention and intervention program for African American families. CSAP; Silver Springs MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCreary M, Belgrave FZ, Allison KW, Groce-Wright C. Project IMPACT: a substance abuse prevention and intervention program for African American families (final report) CSAP; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:648–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon R J, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. J Sch Psychol. 2000;38:501–23. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon RJ, Slough N, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group . Family-based intervention in the Fast Track Program. In: Peters RDeV, McMahon RJ., editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance use, and delinquency. Sage; Thousand Oaks CA: 1996. pp. 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumas JE, Prinz RJ, Smith EP, Laughlin J. The EARLY ALLIANCE prevention trial: an integrated set of interventions to promote competence and reduce risk for conduct disorder, substance abuse, and school failure. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1999;2:37–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1021815408272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haley J. Problem solving therapy. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris SB, Alexander JF, Waldron H. Functional family therapy. In: Falloon IRH, editor. Handbook of behavioral family therapy. Guilford Press; New York: 1988. pp. 107–27. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breunlin DC, Schwartz RC, MacKune-Karrer B. Metaframeworks: transcending the models of family therapy. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madanes C. Strategic family therapy. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press; Cambridge MA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Maughan A. An ecological-transactional model of child maltreatment. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 2nd ed. Kiuwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 2000. pp. 689–722. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry D, et al. Predictors of participation in family-focused preventive intervention for substance use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:S55–S64. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Cin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettit GS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2001;72:583–98. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986;22:723–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB. A developmental-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. J Quant Grim. 2000;16:169–98. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An Ecodevelopmental Framework for organizing risk and protection for drug abuse: a developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: origins and interventions. American Psychology Association; Washington DC: 1999. pp. 331–66. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tremblay RE, Loeber R, Gagnon C, Charlebois P, Larivee S, LeBlanc M. Disruptive boys with stable and unstable high fighting behavior patterns during junior elementary-school. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19:285–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00911232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tremblay RE, Pagani-Kurtz L, Masse LC, Vitaro F, Pihi RO. A bimodal preventive intervention for disruptive kindergarten boys: its impact through mid-adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:560–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLoyd V, Ceballo R. Conceptualizing and assessing economic context: issues in the study of race and child development. In: McLoyd V, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah NJ: 1998. pp. 251–78. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogbu JU. A cultural ecology of competence among inner-city blacks. In: Spencer M, Brookins GK, Allen WR, editors. Beginnings: the social and affective development of black children. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale NJ: 1985. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychol Inquiry. 1997;8:161–75. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates J, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: links to children's externalizing behaviors. Dev Psychol. 1996;32:1065–72. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamborn SD, Dornbusch S, Steinberg L. Ethnicity and community context as moderators of the relations between family decision making and adolescent adjustment. Child Dev. 1996;67:283–301. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray VM, Smith EP, Hill NE. Race, ethnicity, and culture in studies of families in context. J Marriage Far. 2001;63:911–4. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuller ML, Olsen G, editors. Home-school relations: working successfully with parents and families. Allyn & Bacon; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swap SM. Developing home-school partnerships: from concepts to practice. Teachers College Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parsons BV, Alexander JF. Short-term family intervention: a therapy outcome study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;41:195–201. doi: 10.1037/h0035181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DuPaul GJ, Guevremont DC, Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. In: Morris RJ, Kratochwill TR, editors. The practice of child therapy. 2nd ed. Pergamon Press; New York: 1991. pp. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tolan PH. Family-focused prevention research: tough but tender with family intervention research. In: Liddle H, Bray J, Santesban D, Levant R, editors. Family psychology intervention science. APA; Washington DC: 2002. pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry D, et al. Predictors of participation in a family focused preventive-intervention for substance use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:S55–S64. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quinn WH. The Family Solutions Program Manual forjuvenile offenders, truant students, and at-risk youth. The University of Georgia; Athens GA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith EP, Prinz RJ, Dumas JE, Laughlin J. Latent models of family processes in African American families: relationships to child competence, achievement, problem behavior. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63:967–80. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevenson HC, Davis GY, Abdul-Kabir S. Stickin’ to, watchin’ over, & gettin’ with: an African American parent's gide to discipline. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szapocznik J, Santisteban D, Rio A, et al. Family effectiveness training: an intervention to prevent drug abuse and problem behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1989;2:4–27. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wright G, Smith EP. Home, school, and community partnerships: integrating issues of race, culture, and class. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998;1:145–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1022600830757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]